Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la

première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site

LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

Internal Report (National Research Council of Canada. Division of Building

Research), 1970-04-01

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

NRC Publications Archive Record / Notice des Archives des publications du CNRC :

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=bda9d509-52db-473a-acd9-dce660fb96fc https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=bda9d509-52db-473a-acd9-dce660fb96fc

Archives des publications du CNRC

For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous.

https://doi.org/10.4224/20338142

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Housing in Hokkaido

NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF CANADA DIVISION OF BUILDING RESEARCH

HOUSING IN HOKKAIDO by

H. Nakamura

ANALVZED

Internal Report No. 375 of the

Division of Building Research

Ottawa April 1970

Hokkaido, the north island of Japan, has a climate very similar to southern Ontario and uses basically the same materials for house construction as are used in Canada. It is of interest, therefore, to examine all aspects of housing in this part of Japan and to make comparisons with Canadian conditions. The policies and regulations affecting the Japanese housing industry are discussed as well as the factors influencing production. Finally a description of housing production techniques completes the report.

This paper was prepared by Dr. H. Nakamura, a member of the staff of the Hokkaido Building Research Institute in Sapporo. Dr. Nakamura, as a visiting scientist with the Division of Building Res ear ch , National Res earch Council of Canada, carr ied out a study of house production procedures during his visit in 1968-69.

Ottawa April 1970.

N. B. Hutcheon, Director.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I NATURAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND 1

II REGULATIONS, POLICIES AND NATURE OF INDUSTRY 3

1. Legislation and Policy 2. Construction Industry

III CURRENT STATUS OF HOUSING PRODUCTION 6

1. Construction of Housing 2. Land Projects

3. Housing Shortage and Demand

IV TECHNIQUES OF HOUSING PRODUCTION 10

1. Construction Techniques 2. Prefabrication 3. Winter Construction V CONCLUDING NOTES 18 REFERENCES TABLES I - XI FIGURES

by H. Nakamura

1. NATURAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

Geography (Figure 1, Table I): - Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan's four main islands, lies between about 410 and 450 north latitude. Its

land area is one fifth the total area of Japan. About three-quarters of it is for ested.

History: - Until 1868, Hokkaido was a seasonal fishing base in the

northern sea. In that year, a formal development bureau of the central government was set up in Hokkaido, and a systematic immigration was started in order to develop untapped resources, especially agricu.lcural resources.

Climate (Figure 2): - Due to its northern location and the influence of the cold ocean current, Hokkaido is marked by a cool climate with a

long cold winter and much snow. Its climatic conditions are very similar to those in the southern part of Canada (Figure 1).

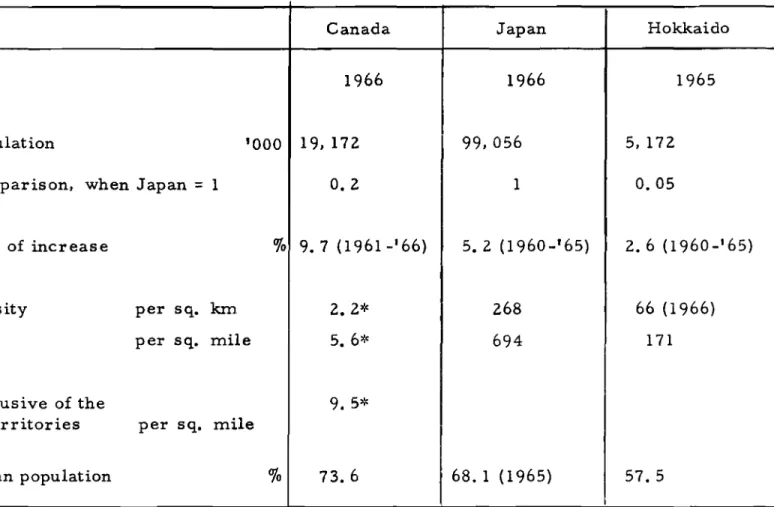

Population (Table II): - Japan is one of the most densely populated of the developed countries. Hokkaido is the least densely populated area of Japan with about 5 million- one twentieth of the total of Japan.

Although her population has increased year by year, the rate of inc r e a s e has declined in the past 10 years due to the outflow of young people to join the industrial labour force on the main island. As in other areas in Japan, the concentration of population in urban areas is rernarkable.

Labour force (Table III): - Industries in Hokkaido have suffered from the shortage of labour force. Young people leave and go to the main island where there are better working conditions and a greater variety of jobs. When the distribution of the labour force among the various industrial groups is examined, the proportion in the manufacturing industries is seen to be rem.arkably small.

Industry (Tables IV and V): - A characteristic of Hokkaido's industry is that, proportionately, the product of the primary industries is large while that of the secondary industries is small compared with the whole country. In the secondary industries, the proportion of manufacturing industries is very small; leading industries are light ones such as foods, woods and furniture, and pulp and paper. In Japan, Hokkaido is famous for coal: she produces more than 40 per cent of the total production of Japan.

Transportation: - As Hokkaido is an island separate from the main island, sea transport has been inevitable between the two. On Hokkaido railways have played a major role since development of the island started. In recent years there has been a surprising increase in road transport and it is gradually taking the place of the railways. The road conditions,

however, are not as good as those of the rest of the country and, consequently, there is an urgent need for their improvem.ent.

Trade: - Import and export trade to and from Hokkaido is very high (33 per cent for imports and 26 per cent for exports in 1965) c ornp ar e.I with that of the whole country (10 per cent for imports and 11 per cent for

exports). Imports are primarily products of heavy industries and exports ar e products of light industries.

Standard of Living (Table VI): - The living standard in Japan is low compared with that in Canada, although there are many economic and social differences between the two. Total expenditures of urban families in Hokkaido are lower than for those in the country as a whole, in spite of the fact that families in Hokkaido have additional expenditures for fuel and clothing due to the cold climate; Hokkaido accounts for about 20 per cent of the national average consumption. A break-down of the expenditures of Japanese (Hokkafdovs ) and Canadian families gives very different results; for exarnp Ie , Hokkaido! s rate of food expenditure is very high (37 per cent) compared with Canada (21 per cent), while the rate of housing expenditure is lower (15 to 16 per cent) than that of Canada (24 per cent).

II. REGULATIONS, POLICIES AND NATURE OF INDUSTRY 1. Legislation and Policy

The Building Standard Law: - This law is equivalent to the National

Building Code of Canada; it provides the minimum standards for planning, structures and materials for buildings. On the basis of it, prefectural and municipal bylaws are provided to meet local conditions. All buildings which are newly built, extended or altered, except for very small ones, must abide by the Building Standard Law.

Government assistance for housing: - There are three basic types of housing which receive government assistance.

1) Public Housing is built by local public bodies with central government subsidies and is rented at a minim.al rent to Iow-dn c orn e people suffering from a housing shortage. The rate of the subsidy is a half or two-thirds the standard construction cost.

2) The Japan Housing Corporation builds housing for rent or sale in urban areas where the shortage is severe. Usually the Corporation provides land for housing in residential communities.

3) The Housing Loan Corporation provides financial assistance similar to that given by the National Housing Act of Canada. The Corporation provides long-term Ioan s at low inter est rates to thos e who want houses for ownership, rent or sale. The amount of loan is 60 to 85 per cent of the total construction cost.

The Hokkaido Cold Weather Housing Law: - In 1953 a law was passed to promote housing designed for cold weather, for until this tim e the construction of hous es in Hokkaido had not differ ed from that in the main island- the temperate area. Under the terms of the law,

housing with public financial assistance must be constructed to protect against cold weather and fire. Because wood construction is not

considered to be fire resistant and is not permitted under the law, the

law has had an important effect upon housing in Hokkaido since its enactment. 2. Construction Industry

Construction activity (Table VII): - In recent years, the total value of work performed by the construction industry in Japan has been about 20 per cent of the Gross National Product - the same proportion as in Canada. About 5 per cent of this work is done in Hokkaido, Construction activity there differs from that of the rest of Japan because Hokkaido is still being developed; engineering works exceed buildings, and public works exceed private works, while elsewhere in Japan it is the opposite. In Hokkai do , construction activity alrno st stops during the winter months and this has an irnpo rt ant effect on the construction industry.

Contractors (Table VIII): - A contractor in Japan is supposed to register with the Minister of Construction or the Prefectural Governor concerned, depending on the regional range of his activity. The number of contractors in Hokkaido is about 7 per cent of the total in Japan, while its share of construction activity is about 5 per cent that of Japan. Most contractors (99 per cent) are registered with Prefectural Governors; their operation is small in size and they have little capital. The role of small contractors in Hokkaido is important; those having capital less than ¥50, 000, 000

do 80 per cent of the total construction work, as compared with 50 per cent in Japan in 1965.

Construction labour: - In Japan as a whole, 6 to 7 per cent of the total labour force is engaged in the construction industry; in Hokkaido, 8 to 9 per cent, and in Canada, 6 to 7 per cent. The most important characteristic of Hokkaido' s construction labour force is that a considerable proportion, especially skilled labour such as carpenters, comes from the main island during all construction seasons except winter. A high proportion of casual workers is another charac-teristic of the construction labour; 36 per cent as compared with 8 per cent in the manufacturing industry. There is a serious labour shortage in the industry, especially among skilled and young labour.

Materials (Table IX) - Those used in Japanese housing construction are much like those used in Canada. Basic construction materials are produced in Hokkaido, but m.aterials such as glass, hardware and pottery are im.portant from the main island, making costs in Hokkaido generally higher than those in the rest of the country.

6

-III. CURRENT STATUS OF HOUSING PRODUCTION

1.

Construction of Housing (Table X) - In recent years housing has been constructed at a rate of 1, 000, 000 units per year in Japan and 60,000 units in Hokkaido, and the rate is increasing yearly.Initiation: - In both Japan and Canada the majority of houses are built on private initiation, but in Japan publicly initiated housing plays a greater role: i. e., 7 to 8 per cent as compared with 1 to 2 per cent in Canada in past years (3 to 5 per cent in the past two years). The corresponding figure is greater in Hokkai do : 8 to 10 per cent. The majority of those who initiate housing privately are the home owners or owners of rental houses, while in Canada, the role of speculative builders is very remarkable.

Financing: - In recent years the proportion of housing receiving public assistance is very similar in Canada and Japan- 30 to 40 per cent of the total. A greater proportion of these are financed by public loans (more than 40 per cent) in Japan than in Hokkaido, where a greater proportion is made up of public housing (30 per cent). The main reason for the high proportion of public hous ing and the low demand for public loans in Hokkaido is that housing receiving any public assistance must conform to the Hokkaido Cold Weather Housing Law which, for fire protection, prohibits houses of wood construction and many people want wood for both aesthetic and economic reasons.

Tenure: - In Japan, 45 to 60 per cent of the houses are owner-occupied; in Hokkaido, 45 to 50 per cent; and in Canada this figure is higher, 65 to 80 per cent according to the National Housing Act. The figure has been

declining in recent years in both countries. In Hokkai do, 13 to 19 per cent of housing are units provided by governrn.ent or companies for

Structure: - In Hokkaido the construction of houses with public assistance differs from those without public assistance. The latter, which are usually single-family houses or small apartments, are m.ost frequently constructed with a wood system. as is also the case in

Canada. The structural forms, however, differ between the two countries: Hokkaido (or Japan) uses the post and beam. construction method, while Canada uses the frame method. Of housing built with public assistance, small houses most cornrnonly are constructed with lightweight concr ete blocks, and apartment buildings generally us e reinforced concrete. wood being prohibited under the Hokkaido Cold Weather Housing Law.

Type: - A large proportion (an estimated 60 to 70 per cent) of new housing in Japan is made up of single-family dwellings; in Canada, since 1960. about 50 to 60 per cent are Single-family units. Generally speaking. privately owned houses are single-family dwellings, privately rented houses are single-family dwellings or small apartments, public housing is row houses or apartments. Japan Housing Corporation

housing is apartments, and housing built by a government or a company for employees is single-family dwellings or apartments. In single ... family dwellings in Hokkaido, one and a half storey houses are popular for economic reasons.

Standard of housing: - Japanese housing standards are low compared with Canadian. The average gross floor area of new (1966) Japanese houses is 680 sq ft; compared with 1, 240 sq ft for Canadian houses financed under the National Housing Act in 1967. The average numb e r of rooms per dwelling is 3.6 (in 1965) in Japan. compared with 5.3 (in 1961) in Canada. Facilities in Japan such as flush toilets and baths are poor. and there is seldom a hot water supply or central heating

in Ho.kka.i do , Generally speaking, an owned house is far superior to a rented house in terms of floor area and facilities.

Housing costs: - A house, not including the land, costs about three times the annual income of the average working man. Costs have doubled in the past ten years mainly as a result of wage increases for building Iabour , Land, especially in urban areas and suburbs, is extraordinarily expensive. For an average worker, it is difficult to obtain land at a reasonable price and thus to have a house.

Procedure of house building: - Housing production in Japan procedes differently from that in Canada. Custom houses that are designed almost according to the owne r ' s wishes are common in Japan, while most hous es are built by speculative builders in Canada. A typical procedure for hous e building in Japan is as follows:

- A prospective house owner obtains a lot by buying or renting. - He asks an architect or a contractor to design his house to suit his budget, lot, family and taste.

- He must then submit an application to the building official in the city planning district and obtain the authorization to proceed.

- He asks a contractor or a carpenter to build his house according to the plan. The architect who designed the house supervises the

construction in most cases. Some people (in the old days most people used to) ask a carpenter to build their house according to an oral contract

or only a simple floor plan. When this is done, many troubles are apt to arise after the house is completed.

It is very troublesome for people to have a house built, because it involves them in many unfamiliar matters.

2. Land Projects

Development of new housing land: - As in Canada, urbanization has rna de it very difficult to obtain proper land for housing especially in

large urban areas. The cost of land in cities in Japan increased elevenfold in the past twelve years and this has caused a bottle-neck in sound housing production. One of Japan's main housing policies is to develop housing land by st.abil iz in g the cost of land.

Of the 34,800 hectares developed between 1961 and 1965, 16, 000 were developed by public bodies such as prefectural or municipal governments and the Japan Housing Corporation. Urban renewal: - The purpose of the urban renewal program is to improve blighted areas and to maximize the use of land in cities; the central government provides financial assistance to municipalities undertaking such programs. An exarnp le of one measure used in urban renewal is improvement of building structures within the existing

built-up area; many small commercial buildings are replaced by a few large fire-resistant buildings by the joint action of their owners. Usually, the upper floors of the new buildings are used as housing accommodation.

3. Housing Shortage and Demand

The report of the Housing Survey of 1963 showed that the housing shortage (defined in Table XI) had declined since a previous

survey taken in 1958; the rate in 1963 was 14 per cent in Japan and 11 per cent in Hokkaido. Of the total housing, the proportion classified as "crowded" is very high both in Japan and in Hokkaido, This means that houses of lar ger floor ar ea should be constructed in the futur e.

According to the Five Year Program of Housing Construction of the Ministry of Construction, the number of houses to be built in Japan between 1966 and 1970 will be 70 per cent higher than the number built between 1960 and 1965, and in Hokkaido the number will be 30 per cent higher. Of the total to be built in 1966 to 1970, it is estimated that the proportion of rental houses and houses with public assistance will be greater than in the previous 5 year period.

IV. TECHNIQUES OF HOUSING PRODUCTION 1. Construction Techniques

History: - Immigrants who came to Hokkaido a hundred years ago built their houses the same way as they had on the main island where the climate was temperate, and soon they found their houses

unsuitable for Hokkai do ' s cold weather. But they did not winterize or improve them, partly because they did not know how to, and partly because even if they had known, the pressures of living kept them fully occupied: most of them came to Hokkaido with the intent of achieving success, and then retiring to their home town to live their old age. Due to these circumstances, before World War II almost all the hous es in Hokkaido wer e of poor quality for hous es in a cold region.

After the war, various efforts were rna de to improve houses in Hokkaido. Other materials than wood were desired, because forest resources were very limited at the time, and wood construction was not considered to be fire resistant. One m.aterial developed was a concrete block which rna de use of the volcanic gravels abundantly produced in Hokkaido. Since then, concrete blocks have most

commonly been used for houses built with public assistance, although wood is still popular for houses built without public assistance.

The construction of typical small houses in Hokkaido using these two materials is now described.

Excavation and foundations: - The excavation is usually dug manually. Power machines are seldom used for this job because they are expensive, and in any case, most houses have no basements.

A pier foundation of concrete or wood used to be most common in wood construction. At present, a type of concrete wall foundation is popular in both wood and concrete block construction, although piers are still used between the foundation walls. Foundations ma.de with concrete blocks are reinforced. Except on large construction sites, concrete is mixed by hand or by a small power mixer located on the site. Forms for the concrete are made of pieces of board and can be used only once. The depth of the foundation walls is determined by the depth of frost penetration in the ground: 2 to 3 ft usually but more than 5 ft in sever ely cold ar eas ,

Basements: - For several reasons, houses in Hokkaido rarely have basements. The additional excavationnecessarybeyond theusual2 or 3 ft required for the footings, is exp ensive; the water table in housing areas is generally high, making damp-proofing more difficult than in Canada; and finally the living standard in Hokkaido is not high enough to allow for extra space to be us ed the way it is in Canada.

Framing and sheathing: - The sequence for framing and sheathing the type of construction used in Hokkaido is as follows:

- Sill plates and floor beams (4 in. by 4 in. ) are installed to support floor joists. Sill plates are placed on the foundation walls and on piers in the crawl space. Floor beams are then placed on piers, spaced about 3 ft o. c. between the sill plates.

- The post and beam wall framing is assembled on the floor framing. Posts and beams are usually cut and routed on the site. Posts ar e uniform in size, about 4 in. by 4 in. I but beams vary from 4 in. by 4 in. up to 6 in. by 12 in, , depending on the span. The post and beam connections used to be very complicated, but have been simplified by the use of steel plates and bolts.

12

-_ The Hokkaido method of roof framing is different from that of the conventional Canadian frame construction. First. posts (4 in. by 4 in.. ) are installed on the floor beams L) s upport the roof framing. Roof

beams (4 in. by4in.) are then placed on these posts. Purlins (1 3/4 in. by 1 3/4 in. ) are installed across the beams. spaced 18 in. o. c.

to support the roof sheathing (l/Z-in.-thick lumber).

- Purlins (1 3/4 in. by 1 3/4 in. ) are installed ac r os s the floor beams, also spaced about 18 in. o. c.

_ Subfloors are installed on these purlins to provide a base for the finish flooring. The subfloor usually c on sist s of l/Z-in. -th.ick lum bel'

when "tatami" ( a kind of mat) are us ed, and 3/8 -in. -tb.ick lumber with hardwood flooring. When resilient flooring is used the subfloor usually consists of セ ...in. -thick lumber covered with 3/16-in. -thick plywood. Plywood more than liZ-in. thick. as is used in Canada, is seldom used for subfloors in Japan.

- Studs (1 3/4 in. by 1 3/4 in. ) are inst.alled between posts. spaced 18 in. o. c. Wall sheathing consists of Iurnbe r (3/8-in. thick or more) or plywood (3/16-in. thick or more).

The Hokkaido method of framing requires a longer time than that of Canadian frame construction. because the structure especially at the joints. is complicated and sheathing usually consists of narrow pieces of boards.

Wall structure of concrete block construction: - To say that there is no difference in the construction of a wood or a concrete block building, except at the exterior wall structure, is no exaggeration. The exterior wall is built in the following way:

- Concrete blocks (40 ern by 20 em, and 15 to 20 ern thick) are laid with mortar on the reinforced foundation walls. to which vertical steel reinforcements have already been anchored.

- I n the wall, vertical and horizontal reinforcements, 3/8 in. or more

in diameter, are fitted every 32 in. or less o. c. at the Joints of concrete blocks, and the edges of openings and the corners and intersections of walls are reinforced with steel rods l/Z in. or more in diameter. The reinforcements are covered with concrete.

-.- Reinforced concrete beams are installed on the concrete block walls. The method of framing for the £loor, partitions and roof is just the same as that for wood construction, ex cept concrete block con-st r uct irn involves block laying, reinforcement incon-stallation and concreting.

Exterior and interior finishes: - Lapped wood siding used to be the

most common exterior finish on wood constructions. At present, stucco on lath together with_the wood siding is also popular in cities because of the fire protection it affords. Concrete block constructions are commonly finished with painted stucco, although for aesthetic reasons some houses are only painted. Because masonry veneer is expensive; it is used only on decorative parts such as the main entrance.

Tiles are the traditional roofing on Japanese houses. In Hokkaido, wood shingles used to be common, but now, galvanized steel sheets are most popular because of their protection against fire and because snow easily slides down their smooth surface. Sheets are usually about Z ft by 1 1/2 ft in size and are painted after

installation; however, roll-type or paint -coated sheets are becoming increasingly popular. Asphalt shingles are rarely used in Japan as roofing.

The traditional floor finishes are "tatami" in the living and bed rooms, and lumber in the kitchen and hall. "Tatami" is a kind of straw mat, about 3 by 6 ft in size, and Z l/Z-in. thick. People take

meals sitting on "tatami" and sleep on rn att r e s s e s spread on t.hern , Since the War, hardwood and resilient flooring have been taking the place of "t.atarni" and lum.ber flooring, although most people want to have at least one "tatami" room. in their new house to retain the old

Japanese living habits.

Lath and plaster is the traditional interior wall finish, but in recent years, plywood, hard-fibre boards and gypsum boards with a paper or cloth finish, have been popular. Prefinished plywood, and prefinished hard-fibre, and chip boards have also come into general use in past years. Such use of gypsum boards as is made in Canadian housing is not common in Japan. The Japanese are accustomed to the appearance of posts and corner trim on the walls and do not mind joints between wallboards, while Canadians are used to plain plaster walls and do not like revealed joints.

Door and window: - Most doors and window frames are wood. Double sash windows are cornrnon now in Hokkaido, although they were rare before the War.. Grooves and stops are most used for air-t ightn e s s , Because of relatively high costs, aluminum sashes, double-glazed

windows and weather strips are not common. The sliding type of window is dominant in Hokkaido,

Thermal insulation and vapour barrier: - Before the War, almost all houses in Hokkaido were built without insulation. At present most new houses are insulated, although the standard of insulation is not as high

as that in Canada. There is an advisory proposal providing maxirnurn thermal transmission (U value) to which most designers refer. Maximum U values are determ.ined according to the climate area and the part of the building involved; i , e., 0.20 to O. 38 Btu/sq ft /hr /" F in most parts in Hokkaido, compar ed with O. IO or lower in Canada. Miner al wo o l is usually 1 to 1 1/2 -in. thick compared with 2 to 4 in. inC an a da ,

Insulating m.aterials used in Hokkaido are much the s arn.e as those in Canada - mineral wool and cellular polystyrene. Sawdust and loose fill mineral wool are, however, still used in horizontal spaces (floors and ceilings) for a cheaper insulation. As in Canada, the insulation is installed between the studs in wood frame walls and between the furring strips in concrete block walls.

Building papers and polyethylene sheets are installed on the warm side of the insulation to act as a vapour barrier.

Fire protection: - It used to be said that Japanese houses were made of wood and paper. Making things worse, heating facilities in Hokkaido's houses have been space heaters with steel pipe chimneys. It was,

therefore, all too easy for a fire to start and spread to adjacent separate buildings with wood sidings and shingles.

Now that houses are being built with chimneys of concrete blocks and flue tiles, with roofs of galvanized steel sheets, and with exterior walls of concrete blocks or stucco on lath, there are fewer fires than previously. It is recognized, however, that the fire resistive quality should still be improved, especially inside the house.

Regulations require fire resistive construction between dwelling units of apartment buildings.

Sound control: - It is probably in the area of sound control that Japanese houses are lagging most. Partitions between rooms in a dwelling commonly used to be paper sliding doors. Multiple dwelling units were not widely used and little interest was shown in controlling sound. Now that they are rno r e popular and a great number of people live in apa r trnent s , there are num.erous complaints about poor sound control in both wood and c on c r et e constructions. Techniques for sound control that are used in Canada,

such as staggered studs and floating floor surfaces, will be applied to Japanese houses in the future.

16

-Heating: - Coal or wood stoves and space heaters are the traditional sources of heat in Hokkaido and they are still the most common. In recent years. oil stoves are being used more and more for their advantages of cleanliness and ease of handling. The proportion of oil stoves is. however. very small. because oil is about three times as expensive as coal. Central heating is rare; each room. is heated by a space heater as occasion demands. In recent years. experiments in heating a whole house by one stove have been made successfully in many houses.

Ventilation: - In winter, the humidity inside a hous e in Hokkaido is high: a kettle is always on the stove to provide hot water and the

laundry is dried in the living room. When houses were not so air-tight,

there was little problem with condensation. but after the War. while living patterns remained the same. houses were built with double sash windows and walls of stucco and concrete blocks. and condensation. on or in walls and in attic spaces, became a problem especially in concrete-block houses. Today. along with an increase in the thickness of insulation, ventilators are often installed in each room and attic. They are also

installed in the foundation walls to reduce humidity in the crawl space during the summ.er and to prevent decay of the floor framing.

Mechanization: - Housing construction is far less mechanized than non-residential construction for several reasons:

- Housing contractor firms are small: they cannot afford expensive machines.

- The housing sites are dispersed rnaking it difficult to use the machinery efficiently.

- The halt in housing construction during winter months discourages contractors from. acquiring machinery.

Some machines such as concrete mixers and power tools for woodwork have, however, come into general use in recent years, due to the shortage and increasing cost of labour.

2. Prefabrication

In Japan, prefabricated housing has been necessitated by the increasingly serious shortage of construction labour. Three types of prefabrication have been developed in the past ten year".

1) Concrete ( site - or factory-cast panels) : the central government took the initiative and developed concr ete panels for publicly initiated housing, but now, they are used for private as well as public multi-family dwelling projects.

2) Steel (steel-framed lightweight panels): developed by steel manufacturers, it is designed primarily for single family housing and is sold to individual house-owners.

3) Wood (wood-framed lightweight panels): this system imitates the traditional wood construction, and is also bought primarily by individual hous e -owner s ,

At present, prefabricated houses comprise about 5 per cent of total dwellings being built in Japan.

Due to its im.portant role in house construction, the

prefectural government in Hokkaido took the initiative and for five years developed prefabrication for public housing. In 1963, interiors (floors, walls and ceilings) were prefabricated using concrete blocks; in 1964, concrete posts and beams and lightweight concrete panels for exter ior walls were developed; and in 1965, concrete panels were tried in public housing. Currently, many municipalities use these prefabricated parts in their public housing.

18

-in Hokkaido than on the ma-in island due to the location and -instability of Hokkaido' s housing m.arket.

3. Winter Construction

Winter construction in Hokkaido used to be rare, but during recent years, the construction of non-residential buildings is

gradually increasing; winter house construction, however, is still

rare. Some problems peculiar to Hokkaido that impede winter construction are:

- - a heavy snow fall which is more troublesome than the cold,

- - a shortage of construction labour during the winter months; most workers,

receiving unemployment benefits, do not want to work, and a consider-able number of skilled workers return to their home town on the main island, and

- - extra expenses necessary for winter construction which are

generally estimated to be 10 to 20 per cent of the total construction cost.

In order to make effective use of the labour force and to improve the construction industry, much effort is being put into promoting all types of construction during the winter. Regarding residential buildings, the prefectural government is trying winter const ruction of its public housing using prefabricated systems.

V CONCLUDING NOTES

The following are three important developments which face Hokkaido's housing in the future:

1) Im.provem.ent of construction techniques

Promotion of mechanization, pr efabrication, and winter construction will be necessary to cope with the increasing shortage

and high costs of construction labour. Some changes in the present organization of housing production may be required to promote these teclmiques.

2) Improvement of quality

To make living comfortable, particularly in the winter, improvements in thermal insulation and heating systems. and the introduction of a hot water supply will be necessary. Improvement in fire protection inside houses, and sound control between dwelling units will also be required.

3) Development of housing land

Housing land supplied at a reasonable price and located within a reasonable distance from urban areas will be vitally necessary to encourage prospective house owners and relieve the shortage of housing.

REFERENCES

Japan and Hokkaido (In Japanese)

1 White Paper on Economy of Hokkaido, 1965, 1966, 1967. Hokkaido Prefectural Government. 1966, 1967, 1968. 2 Graphic Industry of Hokkaido 1967. Sapporo Bureau,

Ministry of Trade and Industry of Japan. 1967.

3 The Annual of Building in Hokkaido 1966. Department of Building. Hokkaido Prefectural Government, 1967.

4 The Climate of Hokkaido, Hokkaido Meteorology Association. 1962.

5 White Paper on Construction in Japan, 1967, Ministry of Construction of Japan. 1967.

6 Report on the Housing Survey of 1963, Bureau of Statistics of Japan.

(In English)

7* Hokkaido: Its Living and Housing, Department of Building. Hokkaido Prefectural Government, 1961.

8* Building Standard Law 1950, Ministry of Construction of Japan, 1954.

9* Ministry of Construction: Its Organization and Function, Ministry of Construction of Japan, 1966.

*

These publications are in the library of the Division of Building Research. National Research Council of Canada.10* Japanese Architectural Techniques, The Architectural Institute of Japan, 1957.

11* Building Research Institute 1966, Building Research Institute, Ministry of Construction of Japan.

Canada

A. General Background

(1.1) Canada Year Book 1967, Dominion Bureau of Statistics (DBS), 1967.

(1. 2) (1. 3) (1. 4) (1. 5)

Canada One Hundred 1867 -1967, DBS, 1967. Census of Canada, 1961.

Encyclopedia Canadiana, Centennial Edition, 1967. Meteorological Observation In Canada, Monthly Record, Jan. -Dec , , 1966.

B. Legislation and the Construction Industry (2.1) National Housing Act 1954.

(2. 2) Various issues (booklets. leaflets folders, and kits) explaining the NHA. Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC).

(2.3) National Building Code of Canada 1965. Associate Committee on the National Building Code.

(2.4) Residential Standards 1965. Supplement No.5 to the National Building Code of Canada. Associate Committee on the National Building Code.

(2.5) A Review of Hou s ing in Canada, CMHC. 1958.

* These publications are in the library of the Division of Building Research. National Research Council of Canada.

(2. 6) (2. 7)

22

-Construction in Canada 1965. 1967, DBS, 1967. The Canadian Construction Industry, Royal

Commission of Canada's Economic Prospect, 1957.

C. Status of Housing Production

(3. 1) Canadian Housing Statistics 1965, 1966, 1967, CMHC. (3.2) Housing and Urban Growth in Canada, CMHC, 1956. (3.3) Housing and Social Capital, Royal Commission of

Canada's Economic Prospect, 1957.

(3.4) Housing Demand to 1970, Wolfgang M. Illing, 1964.

D. Techniques of Housing Production

(4.1) Canadian Wood-frame House Construction, CMHC, 1967. (4.2) Small House Design, CMHC.

Geography

Canada Japan Hokkaido

Total area sq. km '000 9.976 370 79

sq. mi. '000 3.852 143 30

Land area

"

"

3.560Freshwater

"

"

292Comparison of Total area when

Japan

=

1

27 1 0.2Land use 1961 1965 1965

Total area % 100* 100 100

Occupied agricultural land 7.6 16. 3 12. 2

Forest land 47.2

}

}

Grass and brush land

} 45.2***

69.6 74.8

Other land** 14. 1 13.0

*Land area only

**Comprises all other land. i , e. urban land. road allowances. and all waste land

***Includes Yukon and Northwest Territories which comprise 33.2% of all land area

TABLE II

Population

Canada Japan Hokkaido

1966 1966 1965

Population '000 19.172 99. 056 5.172

t

Comparison. when Japan = 1 0.2 1 0.05

Rate of increase

%

9. 7 (1961 -'66) 5.2(1960-'65) 2. 6 (1960 -165)Density per sq. krn 2.2* 268 66 (1966)

per sq. mile 5.6* 694 171

Exclusive of the 9. 5*

Territories per sq. mile

Urban population

%

73.6 68.1 (1965) 57.5>:C Land area only

Labour Force

Canada Japan I Hokkaido

I

J

II

Total employed (1965) 1000 6,862 44, 779 I 2,203 Percentage distribution by industrial group Total0/0

100 100 100 Agricultur e 8.7}

25.0}

24. 1 Forestry}

3. 4Other primary industries 2. 1 8.9

Construction 6. 7 6.. 3 8.5

Manufacturing 23.8 25. 1 11.3

Transportation and other

utilities 9.0 6. 7 9.0

Trade QVセ 7

}

19. 4}

20. 1 Finance, insurance and real estate 4. 1Service

}Z7.6

12. 1 13. 6Public administration and

defence 3. 3 4. 5

0

TABLE IV Production

Canada Japan Hokkaido

1964 1966 1966

$

'000, 000 :I'***

***

Total product 41, 389**

**

¥'OOO. 000. 000***:

28.116 L 343 Percentage distribution by industrial group Total%

100 100 100 Agricultur e 5. 2 } i i. 5 7. 4 Forestry 1. 1 3. 1Fishing and trapping 3. 1 2.9

Mines 4. 1 0.9 3.8

I

Construction 5.4 7. 2 9. 9

Manufactur ing 26.2 27.7 16.8

Transportation, communication

and other utilities 12. 1 9. 2 9.3

Trade 13. 6 17.2 17. 9

Finance. insurance, and real estate 10. 5 9. 1 8.3

Service 14. 6 12. 7 15. 1

Public administration and defence 7. 1

I

4.5 6.9

I

Adjustment -1.4

!

*

Gross domestic product*>,'< Product sales

:1'**

$1.

00 was approximately equal to ¥- 360 during these years.Industrial Production

i

CanadaI

1964 Japan 1965 Hokkaido 1965Total value of product

Percentage distribution Total $'000,000 ¥ '000,000,000 30,856 >;t 100 89, 581 ,:,,;t 29,831 100 2, 347*>:< 782 100 Light industries

Food and beverage

Clothing, textile, and knitting mills Wood, furniture and fixtures

Paper, pulp, and allied products Printing, tobacco products,

rubber, and leather Subtotal

Heavy industries

Primary metal, and metal fabricating Machinery, transportation

equipment, and electri cal products Chemical and chemical products Petroleum and coal products, and

non-metallic products Subtotal Miscellaneous manufacturing

*

Value of shipments**

Value of product Sources: (1.1), 2 19.8 8.0 6.0 8.8 6.8 49.4 15. 2 19. 4 5.87.

6

48.0 2.6 12.5 10. 3 5. 0 3.8 11.6 43.2 13. 7 26.8 9..7 6.6 56.8 34. 3 14. 5 13. 3 9.1 71. 2 17.4 4.9 4. 0 2.5 28.8TABLE VI

Expenditures of City Families

Canada

I

Japan Hokkaidoi

1964>:' , 1966 1966

Family size No. 3.8 4. 16 4.04

I

I

Average expenditure

$

/year 7,031 2, 026 1, 928 II¥/month 195, 110 56, 097 53, 499

Percentage distribution

Total

%

100 100 100Food 21.

a

37. 1 37. 1Housing 24.3 14. 7 15. 7

(Fuel, light and water) (3. 3) (4.6)** (6.2}**

Clothing 8.7 11. 1 11, 7

Incidental 46.0 37. 1 35.5

(Transportation and communication) 02. 4)*** (2.8) (2. 4)

*

In eleven Canadian cities (Families of two or more persons) ** Excludes water*** Excludes communication Sources: (1. 1), 1, 2

Construction Activity

Canada Japan Hokkaido

1965 1966 1965 1966 1966 Total value of construction work performed *

$'

000, 000 9,868 11, 199 17,587 19,850¥IOOO,OOO,OOO

5,856 6,610 286 Percentage of Gross National Product0/0

19.0 19. 4 18.7 18. 3 Inrease rate0/0

14. 3 13. 5 7.0 12. 9 20.8 ! Percentage distribution byj

type of structure Total construction0/0

100 100 100 100 100 Building construction 59.9 59. 3 63.7 62.4I

47.0 Residential (27.9) (25. 4) (34. 5) (35. 4) i Nonresidential (32. 0) (33.9) (29. 2) (27. 0)I

,

EngineeringI

Construction 40. 1 40. 7 36. 3 37. 6 53. 0 Percentage distributionI

by initiation** Private work 56. 1 38. 3 II

Public work 43.9 61. 7 * Actual 1965, Preliminary 1966 ** By general contractors only Sources:u.

1), (2.7), 1, 5Contractors and Builders

I

i[ Canada Japan Hokkaido

I

1951 1967 1967

,

\

Total number of contractors 55,450 120,438 9,067

Register ed by Minister of

Construction 4,659 I 77

Registered by Prefectural

Governor 115,779 8, 990

Increase rate 11. 6 13. 5

i

Scale of capital of contractors

Total

0/0

100 100-¥ 50, 000, 000 or over 1.4

O. 5

Less than ¥50,000,000 98.6 99.5 I

I

iI

Share of construction work

I

I

performed by scale of capital 1965 1965

Total

0/0

I 100 100!

I

¥- 50,000,000 or over I 50.8 20.5

Less than ¥50, 000, 000 49.2 79.5

Builders activity by dwelling unit range in Canada (1967)';'

Dwelling unit range

1 - 5 6 - 15 16 - 50 51 - 100 101

+

Total>:< Dwelling units financed by NHA loans to builders only

Materials

Canada Japan Hokkaido

Production of selected 1963

I

1964 (l966) 1964 (1966)!building m.aterials ;

Sawn lum.ber cu. m.eters 1000,000 22.7 30.9 (48) 3. 1 (3. 3) ft. B. M. '000,000 9, 621

Fibre board sq. m.eters 1000,000 43.9 79 (87.5) 13.7 (11.1)

I

sq. ft. 1/2"B. '000,000 472

Gypsum. board sq. meters '000,000 46. 1 97

I

Isq. ft. 1000,000 496 I

I

Cem.ent tons '000,000 7.0 33.0 (39. 5) 1.3 (1.6)

I

i

Concrete blocks units 1000,000 150 416 27

Galvanized sheets tons 1000 392 1,540 25.9 (54. 7)

I

i

Plywood sq. m.eters 1000,000

I

(859) 35.4 (49.1)I

ft. B. M. 1000,000 556

,

Asphalt shingles squares 1000 3,033

!

Building brick units 1000,000 457

I

I

I

Construction of Housing

Canada Japan Hokkaido Housing construction 1963 149 801 53

starts '000 1964 166 888 59

1965 167 998 60

1966 134 1,038 58

1967 164 L 162*

Publicly Init iat edv» 1963 1,6 7.6 8.7

0/0 1964 1,5 7• 2 8.6 1965 1,6 7. 1 9.4 1966 3.9 7.4 10.9 1967 5. 2 7.4* Financing With public 1963 17. 0(36.1) I 33.8 27.8 asウゥウエ。ョ」・GZBZGセG 1964 18.9(34.7) 34.5 28.2 1965 19.6(34. 0) 39.6 31, 2 1966 30.4(39.7) 38.5 32.3 1967 27. 6( 40. 4) 38.8':' Tenure 1961 1966 1960 1965 Stock '000 4, 554 5, 180 18,851 22, 578 Owned 0/0 66.0 63. 1 67.2 60.8 Rental 0/0 34.

a

36.9 25.9 31. 7 Other 0/0 6.9 7.5 Newly built 1955 1966 1955 1966 Owned 0/0 65.5 47.6 48.4 46.7 Rental 0/0 22.6 40.8 33.6 38.3. Other 0/0 11. 9 11, 6 18.0 15.0 Structure 1963 1963 Stock '000 20, 372 1,027 Wooden 0/0 86.2 74.7Wooden with stucco

exterior 0/0 9. 1 15.4

Reinforced coric r ete

0/0 3.0

}

Concr ete block 0/0 1,6

Steel fram.e 0/0 O. 1 9.9

Solid brick or stone

0/0 O. 0

':' Intention 1967

*':' Canada: Aids to low income groups Japan : Public Housing

*':'* Canada: With public funds under Federal Legislation.

Figures in brackets include institutional loans under NHA Japan : All housing with public assistance

Canada

Type

Single-detached

Semi-detached and duplex Row

Apartment

Standard of newly built houses

%

!

1962 ! (Newly I 57.2 8.4 2.9 31.5 1967 1967 built) 44. 1 6. 1 4.5 45.3 Japan 1963 (Stock) 72.0 28.0 1966 Hokkaido 1966 ,Average floor area sq. meters sq. ft Number of bedrooms Three or less Four or rno r e P'lurribin g facilities Piped water supply

Hot and cold water Cold water only Toilet facilities Flush toilet Cherni ca l toilet Other Bath or shower facilities installed

Average nurnb e r of rOOITIS per dwelling Cost Total Construction Land Other

%

%

%%

%

%%

114.9* 1, 236 82.6* 14.4 1967 89.7 5.5 92.5 1.0 6.5 89.8 1961 5.3 1967 $19,611*** 79.9 18.3 1. 8 62.9 676 1963 68.0 59. 1 1965 3.6 66.8 719 1963 59.9 2.7 } 97.3 37.6 1965 ¥-642. 000****

83.6 16.4*

Under NHA only**

Single detached dwelling under NHA only*** Estimated costs of new single detached dwellings under NHA (approved lenders only)

***':'

Standard costs of low rental public housing (one storey. concrete block construction) Sources: (1. 3) (3. 1), I, 3. 5. 6.Housing Shortage and Demand CANADA

Total occupied dwellings Substandard housing

Crowded*

In need of major repair ':":' Housing demand 1966 - 1981

***

Total demand for new housing (annual averages)

Net household formation Net replacement demand Vacancies 1951 '000 3,409 % 18.8 % 13.4 1966-71 '000 195.6 % 88.5 % 6.9 % 4.6 1971-76 225.6 86.9 8.6 4.5 1961 4. 554 16.5 5.6 1976-81 255.5 84.9 10.4 4.7

*

More than one person per room** In a seriously run-down or neglected condition

***

Estimated by CMHC Sources: (1.3), (3.1) JAPANJapan Hokkaido

Excess of households over dwellings Total family households (1963)

Decayed

*

30% 'in need of major repair'

600/0 'crowded'

**

'000 % 21, 111 13.5 (3. 1) (12.2) (65.7) (19.0) 1, 075 10.7 (6.3) (21. 2) (40.6) (31. 9) Housing dernarid 1966 - 1970**t, Total demand '000 6,776 Factor New households % 47.7 Housing shortage % 35.2 Replacement demand % 12. 1 Vacant dwellings % 5.0 Tenure Owned % 49.0 Rental % 40.3 Issued % 10.7 FinancingWith public assistance % 40.9 Without public assistance % I 59. 1 ':' Impossible to be repaired

*t, More than two (or four) persons in less than 68 (or 100) sq ft floor area

LセLセエL Five year program by Ministry of Construction Sources: 1, 3, 5 348 56.0 29.3 20.0 5.7 40.0 50.0 10.0 42.8 57.2

JAPAN

"U.S.A.

CANADA

/ ,45'セセョエイ・ッャ

.r-• Toronto

FIGURE I

°C

of

°C

of

70

,..

70

20

20

IMONTREAL/

60

""

I60

I10

50

10

I50

I I40

lI.

40

IASAHIKAWA

0

30

0

I I30

I I20

l20

-10

-10

JAN

DEC

JAN

DEC

MONTHLY AVERAGE TEMPERATURE

CM

IN.

CM

IN.

100

40

100

40

ASAHIKAWA

\ \,

\I

50

20

50

\\20

TORONTO

セ\ MONTREAL

\ \ \0

0

0

0

JAN

DEC

JAN

DEC

MONTHLY SNOWFALL (1966)

SR."4-37/-.1.

FIGURE 2

MONTHLY SNOWFALL (1966) AND MONTHLY AVERAGE

TEMPERATURE FOR TORONTO AND SAPPORO, MONTREAL

Excavation

Foundation forms

Foundation and reinforcements

Laying concrete blocks

I

J/

--..:.__1·

(J,

Public hous ing Private house (Owned)

Public housing Private houses (Rental)

Inside woodwork

Lumber roof sheathing and g alvan ized steel roofing

Wood construction (post and beam)

Interior panels Concrete panels

Concrete post and beam construction and light weight concr ete wall panels

Winter Construction

Stop of construction in winter T est construction of public housing in winter (I968)