DOYENS HONORAIRES :

1962 - 1969 : Professeur_Abdelmalek FARAJ 1969 - 1974 : Professeur Abdellatif BERBICH 1974 - 1981 : Professeur Bachir LAZRAK 1981 - 1989 : Professeur Taieb CHKILI

1989 - 1997 : Professeur Mohamed Tahar ALAOUI 1997 - 2003 : Professeur Abdelmajid BELMAHI 2003 - 2013 : Professeur Najia HAJJAJ - HASSOUNI ADMINISTRATION :

Doyen

Professeur Mohamed ADNAOUI

Vice Doyen chargé des Affaires Académiques et estudiantines Professeur Brahim LEKEHAL Vice Doyen charge de la Recherche et de la Coopé ration

Professeur Toufiq DAKKA Vice-Doyen chargé des Affaires Spécifiques à la Pharmacie

Professeur Younes RAHALI Secrétaire Général : Mr. Mohamed KARRA

UNIVERSITE MOHAMMED V FACULTE DE MEDECINE ET DE

PHARMACIE RABAT

1 - ENSEIGNANTS-CHERCHEURS MEDECINS ET PHARMACIENS PROFESSEURS DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR :

Décembre 1984

Pr. MAAOUNI Abdelaziz Médecine Interne - Clinique Royale

Pr. MAAZOUZI Ahmed Wajdi Anesthésie –Réanimation Pr. SETTAF Abdellatif Pathologie Chirurgicale

Janvier, Février et Décembre 1987

Pr. LACHKAR Hassan Médecine Interne

Décembre 1988

Pr. DAFIRI Rachida Radiologie

Décembre 1989

Pr. ADNAOUI Mohamed Médecine Interne -Doyen de la FMPR

Pr. OUAZZANI Taibi Mohamed Réda Neurologie

Janvier et Novembre 1990

Pr. KHARBACH Aicha Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. TAZI Saoud Anas Anesthésie Réanimation

Février Avril Juillet et Décembre 1991

Pr. AZZOUZI Abderrahim Anesthésie Réanimation- Doyen de FMPO

Pr. BAYAHIA Rabéa Néphrologie Pr. BELKOUCHI Abdelkader Chirurgie Générale Pr. BENCHEKROUN Belabbes Abdellatif Chirurgie Générale Pr. BENSOUDA Yahia Pharmacie galénique Pr. BERRAHO Amina Ophtalmologie

Pr. BEZAD Rachid Gynécologie Obstétrique Méd. Chef Maternité des Orangers

Pr. CHERRAH Yahia Pharmacologie

Pr. CHOKAIRI Omar Histologie Embryologie Pr. KHATTAB Mohamed Pédiatrie

Pr. SOULAYMANI Rachida Pharmacologie- Dir. du Centre National PV Rabat

Pr. TAOUFIK Jamal Chimie thérapeutique

Décembre 1992

Pr. AHALLAT Mohamed Chirurgie Générale Doyen de FMPT

Pr. BENSOUDA Adil Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. CHAHED OUAZZANI Laaziza Gastro-Entérologie Pr. CHRAIBI Chafiq Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. EL OUAHABI Abdessamad Neurochirurgie

Pr. FELLAT Rokaya Cardiologie Pr. JIDDANE Mohamed Anatomie

Pr. TAGHY Ahmed Chirurgie Générale Pr. ZOUHDI Mimoun Microbiologie

Pr. BENJAAFAR Noureddine Radiothérapie Pr. BEN RAIS Nozha Biophysique Pr. CAOUI Malika Biophysique

Pr. CHRAIBI Abdelmjid Endocrinologie et Maladies Métaboliques Doyen de la FMPA

Pr. EL AMRANI Sabah Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. EL BARDOUNI Ahmed Traumato-Orthopédie Pr. EL HASSANI My Rachid Radiologie

Pr. ERROUGANI Abdelkader Chirurgie Générale - Directeur du CHIS

Pr. ESSAKALI Malika Immunologie

Pr. ETTAYEBI Fouad Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. IFRINE Lahssan Chirurgie Générale

Pr. MAHFOUD Mustapha Traumatologie - Orthopédie Pr. RHRAB Brahim Gynécologie -Obstétrique Pr. ŞENOUCI Karima Dermatologie

Mars 1994

Pr. ABBAR Mohamed* Urologie Inspecteur du SSM

Pr. BENTAHILA Abdelali Pédiatrie

Pr. BERRADA Mohamed Saleh Traumatologie - Orthopédie Pr. CHERKAOUI Lalla Ouafae Ophtalmologie

Pr. LAKHDAR Amina Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. MOUANE Nezha Pédiatrie

Mars 1995

Pr. ABOUQUAL Redouane Réanimation Médicale Pr. AMRAOUI Mohamed Chirurgie Générale Pr. BAIDADA Abdelaziz Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. BARGACH Samir Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. EL MESNAOUI Abbes Chirurgie Générale Pr. ESSAKALI HOUSSYNI Leila Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie Pr. IBEN ATTYA ANDALOUSSI Ahmed Urologie

Pr. OUAZZANI CHAHDI Bahia Ophtalmologie Pr. SEFIANI Abdelaziz Génétique Pr. ZEGGWAGH Amine Ali Réanimation Médicale

Décembre 1996

Pr. BELKACEM Rachid Chirurgie Pédiatrie Pr. BOULANOUAR Abdelkrim Ophtalmologie Pr. EL ALAMI EL FARICHA EL Hassan Chirurgie Générale Pr. GAOUZI Ahmed Pédiatrie

Pr. OUZEDDOUN Naima Néphrologie

Pr. ZBIR EL Mehdi* Cardiologie Directeur HMI Mohammed V Novembre 1997

Pr. ALAMI Mohamed Hassan Gynécologie-Obstétrique Pr. BEN SLIMANE Lounis Urologie

Pr. BIROUK Nazha Neurologie Pr. ERREIMI Naima Pédiatrie Pr. FELLAT Nadia Cardiologie

Pr. KADDOURI Noureddine Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. KOUTANI Abdellatif Urologie

Pr. MAHRAOUI CHAFIQ Pédiatrie

Pr. TOUFIQ Jallal Psychiatrie Directeur Hôp.Arrazi Salé Pr. YOUSFI MALKI Mounia Gynécologie Obstétrique

Novembre 1998

Pr. BENOMAR ALI Neurologie Doyen de la FMP Abulcassis

Pr. BOUGTAB Abdesslam Chirurgie Générale Pr. ER RIHANI Hassan Oncologie Médicale Pr. BENKIRANE Majid* Hématologie

Janvier 2000

Pr. ABID Ahmed* Pneumo-phtisiologie Pr. AIT OUAMAR Hassan Pédiatrie

Pr. BENJELLOUN Dakhama Badr.Sououd Pédiatrie

Pr. BOURKADI Jamal-Eddine Pneumo-phtisiologie Directeur Hộp. My Youssef

Pr. CHARIF CHEFCHAOUNI Al Montacer Chirurgie Générale Pr. ECHARRAB El Mahjoub Chirurgie Générale Pr. EL FTOUH Mustapha Pneumophtisiologie Pr. EL MOSTARCHID Brahim* Neurochirurgie

Pr. TACHINANTE Rajae Anesthésie-Réanimation Pr. TAZI MEZALEK Zoubida Médecine Interne

Novembre 2000

Pr. AIDI Saadia Neurologie

Pr, AJANA Fatima Zohra Gastro-Entérologie Pr. BENAMR Said Chirurgie Générale Pr. CHERTI Mohammed Cardiologie

Pr. ECH-CHERIF EL KETTANI Selma Anesthésie Réanimation

Pr. EL HASSANI Amine Pédiatrie - Directeur Hôp.Cheikh Zaid

Pr. EL KHADER Khalid Urologie

Pr. GHARBI Mohamed El Hassan Endocrinologie et Maladies Métaboliques Pr. MDAGHRI ALAOUI Asmae Pédiatrie

Décembre 2001

Pr. BALKHI Hicham* Anesthésie-Réanimation Pr. BENABDELJLIL Maria Neurologie

Pr. BENAMAR Loubna Néphrologie

Pr. BENAMOR Jouda Pneumo-phtisiologie Pr. BENELBARHDADI Imane Gastro-Entérologie Pr. BENNANI Rajae Cardiologie Pr. BENOUACHANE Thami Pédiatrie Pr. BEZZA Ahmed* Rhumatologie Pr. BOUCHIKHI IDRISSI Med Larbi Anatomie Pr. BOUMDIN El Hassane* Radiologie Pr. CHAT Latifa Radiologie Pr. DAALI Mustapha* Chirurgie Générale Pr. EL HIJRI Ahmed Anesthésie-Réanimation Pr. EL MAAQILI Moulay Rachid Neuro-Chirurgie

Pr. EL MADHI Tarik Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. EL OUNANI Mohamed Chirurgie Générale

Pr. GAZZAZ Miloudi* Neuro-Chirurgie

Pr. HRORA Abdelmalek Chirurgie Générale Directeur Hôpital Ibn Sina Pr. KABIRI EL Hassane* Chirurgie Thoracique

Pr. LAMRANI Moulay Omar Traumatologie Orthopédie

Pr. LEKEHAL Brahim Chirurgie Vasculaire Périphérique V-D chargé Aff Acad. Est.

Pr. MEDARHRI Jalil Chirurgie Générale Pr. MIKDAME Mohammed* Hématologie Clinique Pr. MOHSINE Raouf Chirurgie Générale Pr. NOUINI Yassine Urologie

Pr. SABBAH Farid Chirurgie Générale

Pr. SEFIANI Yasser Chirurgie Vasculaire Périphérique Pr. TAOUFIQ BENCHEKROUN Soumia Pédiatrie

Décembre 2002

Pr. AL BOUZIDI Abderrahmane* Anatomie Pathologique Pr. AMEUR Ahmed * Urologie

Pr. AMRI Rachida Cardiologie Pr. AOURARH Aziz* Gastro-Entérologie Pr. BAMOU Youssef * Biochimie-Chimie

Pr. BELMEJDOUB Ghizlene* Endocrinologie et Maladies Métaboliques Pr. BENZEKRI Laila Dermatologie

Pr. BENZZOUBEIR Nadia Gastro-Entérologie Pr. BERNOUSSI Zakiya Anatomie Pathologique Pr. CHOHO Abdelkrim * Chirurgie Générale Pr. CHKIRATE Bouchra Pédiatrie

Pr. EL ALAMI EL Fellous Sidi Zouhair Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. EL HAQURI Mohamed * Dermatologie

Pr. FILALI ADIB Abdelhai Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. HAJJI Zakia Ophtalmologie

Pr. JAAFAR Abdeloihab* Traumatologie Orthopédie Pr. KRIOUILE Yamina Pédiatrie

Pr. MOUSSAOUI RAHALI Driss* Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. OUJILAL Abdelilah Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie Pr. RAISS Mohamed Chirurgie Générale Pr. SIAH Samir * Anesthésie Réanimation

Pr. THIMOU Amal Pédiatrie

Pr. ZENTAR Aziz* Chirurgie Générale

Janvier 2004

Pr. ABDELLAH El Hassan Ophtalmologie

Pr. AMRANI Mariam Anatomie Pathologique Pr. BENBOUZID Mohammed Anas Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie Pr. BENKIRANE Ahmed* Gastro-Entérologie

Pr. BOULAADAS Malik Stomatologie et Chirurgie Maxillo-faciale Pr. BOURAZZA Ahmed* Neurologie

Pr. CHAGAR Belkacem* Traumatologie Orthopédie Pr. CHERRADI Nadia Anatomie Pathologique Pr. EL FENNI Jamal* Radiologie

Pr. EL HANCHI ZAKI Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. EL KHORASSANI Mohamed Pédiatrie

Pr. JABOUIRIK Fatima Pédiatrie

Pr. KHARMAZ Mohamed Traumatologie Orthopédie Pr. MOUGHIL Said Chirurgie Cardio-Vasculaire Pr. OUBAAZ Abdelbarre * Ophtalmologie

Pr. TARIB Abdelilah* Pharmacie Clinique Pr. TIJAMI Fouad Chirurgie Générale Pr. ZARZUR Jamila Cardiologie

Janvier 2005

Pr. ABBASSI Abdellah Chirurgie Réparatrice et Plastique Pr. AL KANDRY Sif Eddine* Chirurgie Générale

Pr. ALLALI Fadoua Rhumatologie Pr. AMAZOUZI Abdellah Ophtalmologie

Pr. BAHIRI Rachid Rhumatologie Directeur Hôp. Al Ayachi Salé

Pr. BARKAT Amina Pédiatrie

Pr. BENYASS Aatif Cardiologie Pr. DOUDOUH Abderrahim* Biophysique

Pr. HAJJI Leila Cardiologie (mise en disponibilité)

Pr. HESSISSEN Leila Pédiatrie Pr. JIDAL Mohamed* Radiologie

Pr. LAAROUSSI Mohamed Chirurgie Cardio-vasculaire Pr. LYAGOUBI Mohammed Parasitologie

Pr. SBIHI Souad Histo-Embryologie Cytogénétique Pr. ZERAIDI Najia Gynécologie Obstétrique

AVRIL 2006

Pr. ACHEMLAL Lahsen* Rhumatologie Pr. BELMEKKI Abdelkader* Hématologie Pr. BENCHEIKH Razika O.R.L Pr. BIYI Abdelhamid* Biophysique

Pr. BOUHAFS Mohamed El Amine Chirurgie - Pédiatrique

Pr. BOULAHYA Abdellatif* Chirurgie Cardio - Vasculaire. Directeur Hôpital Ibn Sina Mé

Pr. CHENGUETI ANSARI Anas Gynécologie Obstétrique Pr. DOGHMI Nawal Cardiologie

Pr. FELLAT Ibtissam Cardiologie

Pr. FAROUDY Mamoun Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. HARMOUCHE Hicham Médecine Interne Pr. IDRISS LAHLOU Amine* Microbiologie Pr. JROUNDI Laila Radiologie Pr. KARMOUNI Tariq Urologie

Pr. KILI Amina Pédiatrie

Pr. KISRA Hassan Psychiatrie

Pr, KISRA Mounir Chirurgie - Pédiatrique Pr. LAATIRIS Abdelkader* Pharmacie Galénique Pr. LMIMOUNI Badreddine* Parasitologie

Pr. MANSOURI Hamid* Radiothérapie Pr. OUANASS Abderrazzak Psychiatrie Pr. SAFI Soumaya* Endocrinologie Pr. SEKKAT Fatima Zahra Psychiatrie

Pr. TELLAL Saida* Biochimie

Pr. ZAHRAOUI Rachida Pneumo - Phtisiologie

Octobre 2007

Pr. ABIDI Khalid Réanimation médicale Pr. ACHACHI Leila Pneumo phtisiologie Pr, ACHOUR Abdessamad* Chirurgie générale

Pr. AIT HOUSSA Mahdi * Chirurgie cardio vasculaire Pr. AMHAJJI Larbi * Traumatologie orthopédie Pr. AOUFI Sarra Parasitologie

Pr. BAITE Abdelouahed * Anesthésie réanimation Pr. BALOUCH Lhousaine * Biochimie-chimie Pr. BENZIANE Hamid * Pharmacie clinique Pr. BOUTIMZINE Nourdine Ophtalmologie Pr. CHERKAOUI Naoual * Pharmacie galénique Pr. EHIRCHIOU Abdelkader * Chirurgie générale

Pr. EL BEKKALI Youssef * Chirurgie cardio-vasculaire Pr. EL ABSI Mohamed Chirurgie générale

Pr. EL MOUSSAOUI Rachid Anesthésie réanimation Pr. EL OMARI Fatima Psychiatrie

Pr. GHARIB Noureddine Chirurgie plastique et réparatrice Pr. HADADI Khalid * Radiothérapie

Pr. ICHOU Mohamed * Oncologie médicale Pr. ISMAILI Nadia Dermatologie Pr. KEBDANI Tayeb Radiothérapie Pr. LOUZI Lhoussain * Microbiologie

Pr. MADANI Naoufel Réanimation médicale Pr. MAHI Mohamed * Radiologie

Pr. MARC Karima Pneumo phtisiologie Pr. MASRAR Azlarab Hématologie biologique

Pr. MRANI Saad * Virologie

Pr. OUZZIF Ez zohra Biochimie chimie Pr. RABHI Monsef* Médecine interne Pr. RADOUANE Bouchaib* Radiologie Pr. SEFFAR Myriame Microbiologie Pr. SEKHSOKH Yessine * Microbiologie Pr. SIFAT Hassan * Radiothérapie

Pr. TABERKANET Mustafa * Chirurgie vasculaire périphérique Pr. TACHFOUTI Samira Ophtalmologie

Pr. TAJDINE Mohammed Tariq* Chirurgie générale Pr. TANANE Mansour * Traumatologie-orthopédie Pr. TLIGUI Houssain Parasitologie

Pr. TOUATI Zakia Cardiologie

Mars 2009

Pr. ABOUZAHIR Ali * Médecine interne Pr. AGADR Aomar * Pédiatrie

Pr. AIT ALI Abdelmounaim * Chirurgie Générale Pr. AIT BENHADDOU El Hachmia Neurologie

Pr. ALLALI Nazik Radiologie Pr. AMINE Bouchra Rhumatologie

Pr. ARKHA Yassir Neuro-chirurgie Directeur Hôp.des Spécialités

Pr. BELYAMANI Lahcen Anesthésie Réanimation

Pr. BJIJOU Younes Anatomie

Pr. BOUHSAIN Sanae * Biochimie-chimie Pr. BOUI Mohammed * Dermatologie Pr. BOUNAIM Ahmed * Chirurgie Générale Pr. BOUSSOUGA Mostapha * Traumatologie-orthopédie

Pr. CHTATA Hassan Toufik * Chirurgie Vasculaire Périphérique Pr. DOGHMI Kamal * Hématologie clinique

Pr. EL MALKI Hadj Omar Chirurgie Générale Pr. EL OUENNASS Mostapha* Microbiologie Pr. ENNIBI Khalid * Médecine interne Pr. FATHI Khalid Gynécologie obstétrique Pr. HASSIKOU Hasna * Rhumatologie

Pr. KABBAJ Nawal Gastro-entérologie Pr. KABIRI Meryem Pédiatrie

Pr. KARBOUBI Lamya Pédiatrie

Pr. LAMSAOURI Jamal * Chimie Thérapeutique Pr. MARMADE Lahcen Chirurgie Cardio-vasculaire Pr. MESKINI Toufik Pédiatrie

Pr. MESSAOUDI Nezha * Hématologie biologique Pr. MSSROURI Rahal Chirurgie Générale Pr. NASSAR Ittimade Radiologie

Pr. OUKERRAJ Latifa Cardiologie

Pr. RHORFI Ismail Abderrahmani * Pneumo-Phtisiologie

Octobre 2010

Pr. ALILOU Mustapha Anesthésie réanimation

Pr. AMEZIANE Taoufiq* Médecine Interne Directeur ERSSM Pr. BELAGUID Abdelaziz Physiologie

Pr. CHADLI Mariama* Microbiologie

Pr. CHEMSI Mohamed* Médecine Aéronautique Pr. DAMI Abdellah* Biochimie-Chimie Pr. DARBI Abdellatif* Radiologie

Pr. DENDANE Mohammed Anouar Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. EL HAFIDI Naima Pédiatrie

Pr. EL KHARRAS Abdennasser* Radiologie

Pr. EL MAZOUZ Samir Chirurgie Plastique et Réparatrice Pr. EL SAYEGH Hachem Urologie

Pr. ERRABIH Ikram Gastro-Entérologie Pr. LAMALMI Najat Anatomie Pathologique Pr. MOSADIK Ahlam Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. MOUJAHID Mountasșir* Chirurgie Générale Pr. NAZIH Mouna* Hématologie

Décembre 2010

Pr.ZNATI Kaoutar

Mai 2012

Pr. AMRANI Abdelouahed Chirurgie pédiatrique Pr. ABOUELALAA Khalil * Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. BENCHEBBA Driss * Traumatologie-orthopédie Pr. DRIŞSI Mohamed * Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. EL ALAOUI MHAMDI Mouna Chirurgie Générale Pr. EL KHATTABI Abdessadek * Médecine Interne Pr. EL OUAZZANI Hanane * Pneumophtisiologie Pr. ER-RAJI Mounir Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. JAHID Ahmed Anatomie Pathologique Pr. RAISSOUNI Maha* Cardiologie

* Enseignants Militaires

Février 2013

Pr. AHID Samir Pharmacologie

Pr. AIT EL CADI Mina Toxicologie

Pr. AMRANI HANCHI Laila Gastro-Entérologie Pr. AMOR Mourad Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. AWAB Almahdi Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. BELAYACHI Jihane Réanimation Médicale Pr. BELKHADIR Zakaria Houssain Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. BENCHEKROUN Laila Biochimie-Chimie Pr. BENKIRANE Souad Hématologie

Pr. BENNANA Ahmed* Informatique Pharmaceutique Pr. BENSGHIR Mustapha * Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. BENYAHIA Mohammed * Néphrologie

Pr. BOUATIA Mustapha Chimie Analytique et Bromatologie Pr. BOUABID Ahmed Salim* Traumatologie orthopédie

Pr BOUTARBOUCH Mahjouba Anatomie Pr. CHAIB Ali * Cardiologie

Pr. DENDANE Tarek Réanimation Médicale Pr. DINI Nouzha * Pédiatrie

Pr. ECH-CHERIF EL KETTANI Mohamed Ali Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. ECH-CHERIF EL KETTANI Najwa Radiologie

Pr. ELFATEMI NIZARE Neuro-chirurgie Pr. EL GUERROUJ Hasnae Médecine Nucléaire Pr. EL HARTI Jaouad Chimie Thérapeutique Pr. EL JAOUDI Rachid * Toxicologie

Pr. EL KABABRI Maria Pédiatrie

Pr. EL KHANNOUSSI Basma Anatomie Pathologique Pr. EL KHLOUFI Samir Anatomie

Pr. EL KORAICHI Alae Anesthésie Réanimation Pr. EN-NOUALI Hassane * Radiologie

Pr. ERRGUIG Laila Physiologie Pr. FIKRI Meryem Radiologie

Pr. GHFIR Imade Médecine Nucléaire

Pr. IRAQI Hind Endocrinologie et maladies métaboliques Pr. KABBAJ Hakima Microbiologie

Pr. KADIRI Mohamed * Psychiatrie Pr. LATIB Rachida Radiologie Pr. MAAMAR Mouna Fatima Zahra Médecine Interne Pr. MEDDAH Bouchra Pharmacologie Pr. MELHAOUI Adyl Neuro-chirurgie Pr. MRABTI Hind Oncologie Médicale Pr. NEJJARI Rachid Pharmacognosie Pr. OUBEJJA Houda Chirugie Pédiatrique Pr. OUKABLI Mohamed Anatomie Pathologique

Pr. RAHALI Younes Pharmacie Galénique Vice-Doyen à la Pharmacie

Pr. RATBI Ilham Génétique

Pr. RAHMANI Mounia Neurologie Pr. REDA Karim * Ophtalmologie Pr. REGRAGUI Wafa Neurologie Pr. RKAIN Hanan Physiologie Pr. ROSTOM Samira Rhumatologie

Pr. ROUAS Lamiaa Anatomie Pathologique Pr. ROUIBAA Fedoua * Gastro-Entérologie Pr SALIHOUN Mouna Gastro-Entérologie

Pr. SAYAH Rochde Chirurgie Cardio-Vasculaire Pr. SEDDIK Hassan * Gastro-Entérologie

Pr. ZERHOUNI Hicham Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. ZINE Ali * Traumatologie Orthopédie

* Enseignants Militaires

AVRIL 2013

Pr. EL KHATIB MOHAMED KARIM* Stomatologie et Chirurgie Maxillo-faciale

MARS 2014

Pr. ACHIR Abdellah Chirurgie Thoracique Pr. BENCHAKROUN Mohammed Traumatologie-Orthopédie Pr. BOUCHIKH Mohammed Chirurgie Thoracique Pr. EL KABBAJ Driss * Néphrologie

Pr. EL MACHTANI IDRISSI Samira * Biochimie-Chimie

Pr. HARDIZI Houyam Histologie- Embryologie-Cytogénétique Pr. HASSANI Amale * Pédiatrie

Pr. HERRAK Laila Pneumologie Pr. JANANE Abdellah Urologie

Pr. JEAIDI Anass * Hématologie Biologique Pr. KOUACH Jaouad* Génycologie-Obstétrique Pr. LEMNOUER Abdelhay* Microbiologie

Pr. MAKRAM Sanaa * Pharmacologie Pr. OULAHYANE Rachid* Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. RHISSASSI Mohamed Jaafar CCV

Pr. TAZI MOUKHA Zakia Génécologie-Obstétrique

DECEMBRE 2014

Pr. ABILKACEM Rachid* Pédiatrie

Pr. AIT BOUGHIMA Fadila Médecine Légale Pr. BEKKALI Hicham * Anesthésie-Réanimation Pr. BENAZZOU Salma Chirurgie Maxillo-Faciale Pr. BOUABDELLAH Mounya Biochimie-Chimie Pr. BOUCHRIK Mourad* Parasitologie Pr. DERRAJI Soufiane* Pharmacie Clinique Pr. DOBLALI Taoufik Microbiologie Pr. EL AYOUBI EL IDRISSI Ali Anatomie

Pr. EL GHADBANE Abdedaim Hatim* Anesthésie-Réanimation Pr. EL MARJANY Mohammed* Radiothérapie

Pr. FEJJAL Nawfal Chirurgie Réparatrice et Plastique Pr. JAHIDI Mohamed* O.R.L

Pr. LAKHAL Zouhair* Cardiologie

Pr. OUDGHIRI NEZHA Anesthésie-Réanimation Pr. RAMI Mohamed Chirurgie Pédiatrique Pr. SABIR Maria Psychiatrie

Pr. SBAI IDRISSI Karim* Médecine préventive, santé publique et Hyg.

AOUT 2015

Pr. MEZIANE Meryem Dermatologie Pr. TAHIRI Latifa Rhumatologie

PROFESSEURS AGREGES:

JANVIER 2016

Pr. BENKABBOU Amine Chirurgie Générale Pr. EL ASRI Fouad* Ophtalmologie Pr. ERRAMI Noureddine* O.R.L

Pr. NITASSI Sophia O.R.L

JUIN 2017

Pr. ABI Rachid* Microbiologie Pr. ASFALOU Ilyasse* Cardiologie

Pr. BOUAYTI El Arbi* Médecine préventive, santé publique et Hyg. Pr. BOUTAYEB Saber Oncologie Médicale

Pr. EL GHISSASSI Ibrahim Oncologie Médicale

Pr. HAFIDI Jawad Anatomie

Pr. OURAINI Saloua* O.R.L

Pr. RAZINE Rachid Médecine préventive, santé publique et Hyg. Pr. ZRARA Abdelhamid* Immunologie

NOVEMBRE 2018

Pr. AMELLAL Mina Anatomie Pr. SOULY Karim Microbiologie

*Enseignants Militaires

2 - ENSEIGNANTS-CHERCHEURS SCIENTIFIQUES

PROFESSEURS/Prs. HABILITES

Pr. ABOUDRAR Saadia Physiologie Pr. ALAMI OUHABI Naima Biochimie chimie Pr. ALAOUI KATIM Pharmacologie

Pr. ALAOUI SLIMANI Lalla Naima Histologie-Embryologie

Pr. ANSAR M'hammed Chimie Organique et Pharmacie Chimique Pr .BARKIYOU Malika Histologie-Embryologie

Pr. BOUHOUCHE Ahmed Génétique Humaine Pr. BOUKLOUZE Abdelaziz Applications Pharmaceutiques Pr. CHAHED OUAZZANI Lalla Chadia Biochimie chimie Pr. DAKKA Taoufiq Physiologie Pr. FAOUZI Moulay El Abbes Pharmacologie

Pr. IBRAHIMI Azeddine Biologie moléculaire/Biotechnologie Pr. KHANFRI Jamal Eddine Biologie

Pr. OULAD BOUYAHYA IDRISSI Med Chimie Organique

Pr. REDHA Ahlam Chimie

Pr. TOUATI Driss Pharmacognosie Pr. ZAHIDI Ahmed Pharmacologie

Mise à jour le 04/02/2020 Khaled Abdellah

Chef du Service des Ressources Humaines FMPR

To Pr. RAOUF Mohsine,

Thank you for presiding over my thesis defense. It was an honor doing my thesis project with your team

of the greatest doctors at SCOD.

To Pr. BENKABBOU Amine,

Thank you for taking me under your wing and sharing all the concepts that I would have never thought existed in medicine. You broadened my knowledge and revived my belief in the existence of honest Moroccan doctors. You are a true inspiration and saying that it was an honor having you as my supervisor would be an understatement. I have never encountered someone as meticulous and driven and dynamic as you. I don't wish for this experience to have been any different, and for that, I am forever grateful.

To Pr. GHANNAM Abdelilah,

Thank you for the crucial contribution to this project.

To Pr. HIJRI Ahmed,

Your reputation precedes you. Thank you for doing us the honor of being part of this journey.

To Pr. MAJBAR Mohammed Anass,

Your resources are unlimited, and it was a pleasure to learn from you. Thank you for sharing your technical skills and expert input with us. You contributed greatly to this research project with your adventurous ideas. I appreciate your help steering us in the right direction in every step of the way.

To Pr. SOUADKA Amine,

Your kindness is beyond measure, from the way I saw you treat patients during my very first internship in 2014, to the way you're committed to being a good mentor to your mentees.

Thank you for contributing so selflessly to our work. It has been a pleasure working with you.

TO MY MOROCCAN FAMILY:

To my father Abderrezak HOUSSAINI,

I am here today thanks to you, so I dedicate my accomplishments to you. You taught me to seize opportunities and to learn avidly through formal education and life experiences. I am not biased when I say this: You are the most pure-hearted man and the most thoughtful husband, and your unconditional love and support for your kids makes you the best dad by far. Thank you for all the sacrifices you made when you instinctively put us first, and I hope we are honoring you that we got to where we are today, where you have always wanted to see us.

Thank you papa for pushing me to travel the world before you had even crossed borders. Thank you for supporting me to accomplish my dreams, and for always making life easy when life felt hard. You have always been so present in our lives, even when we don't ask for help, and your presence amongst us is so fulfilling and comforting that we don't imagine a life without you in it.

I can't thank you enough for being the perfect dad you are. I love you papa hbibi.

To my mother Nadia SIBARI,

You are the woman to turn to for adventures. You are fearless when protecting your family and you never hesitate to make sacrifices if it means making us happy. I hope I am ridding you of part of the stress now that at least the first of your kids has graduated (until it's time to embark on my next adventure). It has always been a dream of yours that I become a doctor and I am happy to make you this proud. I love you mama .

To my sister Nouhaila HOUSSAINI,

Thank you for always having my back. Know that I will always have yours. You can do whatever you set your heart to; don't give up. I love you.

To my brother Saâd HOUSSAINI,

You will forever be my baby brother. I can't wait to attend your graduation in a few years and call you doctor, for mom's biggest pleasure. I love you.

To my grandparents:

Khadija EL ATIFI Mohammed HOUSSAINI

Malika EL OUAZZANI

To the memory of Sidi Ahmed SIBARI

To my aunts:

Fatima SIBARI Assia SIBARI

TO MY AMERICAN FAMILY:

To Denise KALL & Michael BRENNAN,

I cannot thank you enough for opening your home and hearts to sixteen year old me. I am blessed to call you my parents. I dedicate my accomplishments to you for all the love and support you granted me. The fact that we are family by choice makes our family bond even stronger, and it is one that I know will last forever, which gives me comfort. I am glad my nickname got upgraded to Dr.Kid now. Oohiboukouma.

TO MY SWEDISH FAMILY:

Tack för att ni finns.To Oskar HAGMAN,

Thank you for being my rock; you have always been so supportive. You first helped me with Swedish, then you helped me feel Swedish, and on top of it all, you introduced me to the HAGMAN/NILSSON SuperFamily.

Your immense ambitions are inspiring, and I am happy to stand by you when you make your way to Khartoum, Sudan, or wherever your brains end up taking you. It is wonderful to know someone as cultivated and smart and caring as you. Your sense of humor is only the cherry on top.

To Lina HAGMAN,

You are literally SuperWoman, and I am curious how you can manage that while also being SuperMom. I want to be you.

To Sara NILSSON,

No wonder Lina is both SuperWoman and SuperMom; she gets that from you. Thank you for always keeping me in your thoughts

and for showering me with more love than I could ask for.

To Peter HAGMAN,

You are one of a kind.

To Eva NILSSON,

Det här är på svenska för att göra dig stolt. Tack för allt Eva, jag älskar dig.

To Joni HAGMAN To Ava HAGMAN To Sam HAGMAN

I can unfortunately not steal you from your very loving parents, but I have a pretty clear picture of how I want my future 3 babies to be.

Audit of a New Liver Resection Program: Aggregate

Root Cause Analysis of Severe Complications after

100 Consecutive Cases

PROLOGUE

The implementation of a surgery program in a new environment is a complex process that involves the deployment and the rather quick adaptation of various multidisciplinary activities, both technical (e.g: perioperative care, surgical and anesthetic techniques) and non-technical (e.g: communication, coordination of the patient pathway). This process does not follow a specific methodology and remains poorly documented in the medical literature. Our study falls within the audit of the initial phase of the implementation of a new liver surgery program in the context of a university hospital dedicated to cancer treatments, with high volume of digestive (non hepatobiliary) surgical activity. The aim of this study is to develop operational measures to control severe postoperative complications (prevention, detection and management) through a systemic analysis of the contributory factors and recovery factors using a mixed quantitative and qualitative methodology (Root Cause Analysis).

LIST OF FIGURES

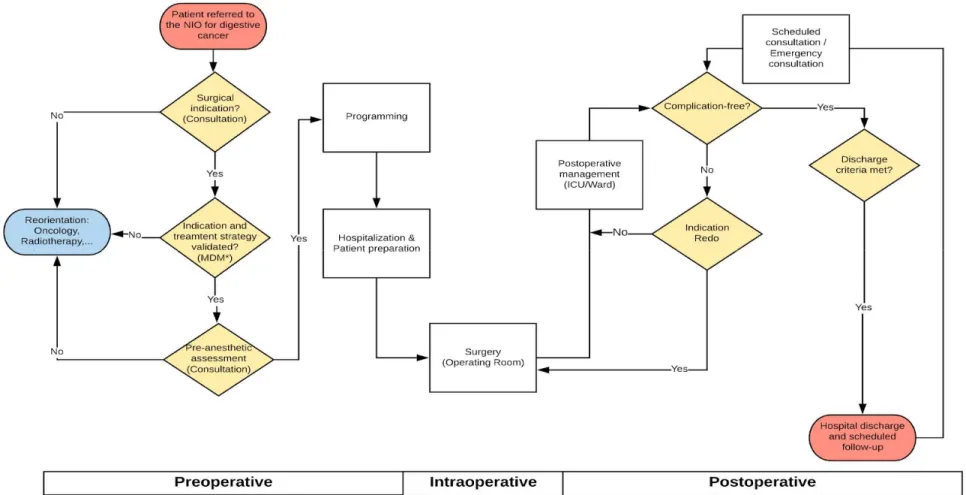

Figure 1 (a-b): Schematic anterior view of the glissonian pedicles (a) and the corresponding liver segments (Sg1 located posteriorly) (b) ... 5 Figure 2 (a-b): Schematic anterior view of liver segment venous drainage through the right hepatic vein (RHV), middle hepatic vein (MHV) and left hepatic vein (LHV) into the inferior vena cava (Veins of sg 1 not shown) ... 6 Figure 3: Swiss cheese model by James Reason published in 2000 ... 15 Figure 4: Process of Root Cause Analysis, from ... 16 Figure 5: Digestive cancer surgical pathway for patients at the NIO. ... 22 Figure 6: Chronology of the main quality improvement program measures at the NIO since the beginning of the study period ... 23 Figure 7: Distribution of in-hospital and POD90 complication severity in 100 patients, according to the Clavien-Dindo classification ... 35 Figure 8: CUSUM graph showing a single turning point starting from case 49, corresponding to a decrease of the observed occurrence of severe complications after liver resection. (Turning point indicated by red arrow). ... 40 Figure 9: Three contrasting approaches to safety, from Safer healthcare (Elsevier)... 56

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Classification of surgical complications, according to Clavien-Dindo ... 8 Table 2: Post hepatectomy liver failure grading, according to the ISGLS ... 9 Table 3: Risk factors for post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) ... 9 Table 4: Grading of bile leak after hepatobiliary surgery, according to the ISGLS... 10 Table 5: Risk factors of bile leak following liver resection. ... 11 Table 6: Grading of post hepatectomy hemorrhage, according to the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS)]. ... 12 Table 7: The ALARM framework of contributory factors ... 17 Table 8: Characteristics of the research team and participants. ... 29 Table 9: Customized ALARM framework questionnaire ... 31 Table 10: Summary of cases of severe complications (Clavien-Dindo >IIIa) ... 36 Table 11: Comparison of the characteristics of groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not.. ... 38 Table 12: Comparison of complication types in groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not ... 39 Table 13: Comparison of characteristics and number of severe complications (CD>IIIa) in the first cases operated before the turning point (49th case) vs. cases operated after the turning point. ... 42 Table 14: Contributory factors to the occurrence of liver resection complications in the 15 cases. ... 44 Table 15: Recovery factors and corrective measures ... 45

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ... 1 A. What is a liver resection? ... 2 B. What are the main specific complications after liver resection? ... 8 1. Post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) ... 8 2. Bile leak... 10 3. Post hepatectomy hemorrhage (PHH)... 11 4. Parenchymal necrosis ... 12 C. What is a Root Cause Analysis (RCA) of adverse events? ... 13 II. MATERIAL AND METHODS ... 18 A. Type of study ... 19 B. Research team ... 19 C. Endpoints ... 19 D. Inclusion and exclusion criteria ... 20 E. Context... 20 F. Quantitative analysis ... 24 1. Data collection ... 24 2. Statistical analysis ... 25 a. Trends in the occurrence of severe complications ... 25 b. Demographic and clinical variables ... 26 c. Comparison of groups of patients ... 27 G. Qualitative analysis ... 27 1. Tool selection and customization ... 27 2. Participant selection ... 28 3. Event storyline ... 30 4. Individual analysis ... 30

5. Consensus ... 32 a. Workshop preparation: ... 32 b. Consensus workshop: ... 32 6. Aggregate RCA ... 33 III. RESULTS ... 34 A. Quantitative analysis ... 37 1. Comparison of the characteristics of groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not ... 37 2. Comparison of complication types in groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not ... 39 3. Turning points... 40 4. Comparison of characteristics in cases after turning point vs. before turning point ... 41 B. Qualitative analysis ... 43 1. Study process ... 43 a. Individual analysis... 43 b. Consensus ... 43 c. Contributory factors ... 43 2. Recovery factors & corrective measures ... 45 IV. DISCUSSION ... 46 A. Contextualization of trends ... 47 B. Aggregate RCA of contributory factors ... 49 1. Patient factors ... 49 2. Task factors ... 49 3. Individual staff factors ... 50 4. Team factors ... 51 5. Work environmental factors ... 53 6. Organizational and management factors ... 53 7. Institutional context factors ... 54 C. Recovery factors and corrective measures ... 55 D. Study limitations ... 57

V. CONCLUSION ... 58 ABSTRACT ... 60 APPENDIX ... 64 REFERENCES ... 72

1

2

A. What is a liver resection?

Liver resection, also called hepatectomy, is a surgical procedure that consists in removing part of the hepatic parenchyma where a mass of abnormal tissue is located, regardless of its nature.

In the oncological context, liver resections are part of a customized liver disease treatment program that is validated in a multidisciplinary meeting.

The most frequent liver resection indications are:

Primary hepatobiliary cancers, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),

perihilar and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, and gallbladder cancer.

Liver metastases from colorectal cancer and neuroendocrine tumors.

Benign liver tumors or intrahepatic biliary abnormalities that are

symptomatic and/or susceptible to malignant transformation, such as hepatocellular adenomas and localized forms of Caroli disease.

The general oncological liver resection goal is to perform a resection of all the hepatic lesions with a margin of healthy tissue R0 (margin: ≥1mm) while preserving the vascularization and drainage of an adequate future liver remnant volume [1]. This objective can be achieved by a single liver resection or multiple liver resections, in single or multiple stage operations. In liver metastases and HCCs, “by necessity” R1 resection (submillimeter or zero surgical margin) in direct contact with vessels could be indicated to spare liver parenchyma [1]. In cases of neuroendocrine liver metastases, an indication for R2 resection (resection with macroscopically positive for residual cancer) removing >90% of the tumor volume can be accepted to control the symptoms linked to tumor secretion [2,3].

3

Overall, liver resection is indicated for curative purposes and can justify the use of:

Neoadjuvant therapy, including chemotherapy and/or chemoembolization. Preoperative hypertrophy of future liver remnant, most often through portal

vein embolization.

Associated procedures, the most frequent of which are: Hepatic pedicle lymphadenectomy.

Resection of the biliary convergence and/or the common bile duct followed

by a biliodigestive anastomosis.

Resection and reconstruction of the portal vein and the vena cava.

Digestive resection, whether or not followed by a digestive anastomosis. Peritoneal and/or diaphragmatic resection.

Technically, liver resection can be approached by open, mininvasive (laparoscopic, robotic), or combined techniques. The parenchymal section is usually performed using the clamp-crush technique, ultrasonic dissection and/or vessel sealing systems. Intermittent clamping of the hepatic pedicle (Pringle Maneuver) is selectively used during parenchymal section with the purpose of minimizing blood loss and/or optimizing the identification of intrahepatic vessels.

4

The liver area distribution is based on the description by Couinaud of a functional organization of the liver in 8 autonomous segments (Couinaud segments are indicated in short form as Sg1-Sg8 [4]) having portal and arterial hepatic vascularization as well as biliary drainage organized in independent pedicles (glissonian pedicles) [fig1]. The constant presence of several pedicles destined for segments 4 and 8 defines sub-segments (Sg4a-b and Sg8a-c). Venous drainage runs along the limit of the contiguous segments and is organized as 3 hepatic veins (right, left and middle) that drain into the inferior vena cava. The veins of segment 1 flow directly into the inferior vena cava. [fig2]

5

Figure 1 (a-b): Schematic anterior view of the glissonian pedicles (a) and the corresponding liver segments (Sg1 located posteriorly) (b)

(Illustrations modified from the Surgical anatomy of the liver application by Emory University)

6

Figure 2 (a-b): Schematic anterior view of liver segment venous drainage through the right hepatic vein (RHV), middle hepatic vein (MHV) and left hepatic vein (LHV) into the inferior vena cava (Veins of sg 1 not shown)

(Illustrations modified from the Surgical anatomy of the liver application by Emory University)

7

A liver resection is said to be anatomical (as opposed to a non-anatomical or atypical liver resection) when the limits of the resected area overlap with those of one or more segments or sub-segments. For instance, a bisegmentectomy 6-7 corresponds to the anatomical resection of the 2 contiguous segments 6 and 7; an atypical resection at the junction of segments 2-3 corresponds to the resection of a piece of the parenchyma that is astride the segments 2 and 3 without removing the segments entirely.

A liver resection is said to be major (as opposed to minor liver resection) when the resected area contains at least 3 contiguous anatomical segments. For example: A quadrisegmentectomy 1-2-3-4 is a major liver resection (left hemihepatectomy with resection of segment 1). A trisegmentectomy 4-5-8 is a major (central) liver resection.

The complexity of liver resection is multifactorial, without a unanimously accepted definition. It is determined by the characteristics of the tumor (size, location, proximity to bile ducts and/or to the confluence of hepatic veins into the inferior vena cava), the non-tumor liver tissue (cirrhosis and portal hypertension, chemotherapy toxicity), the technique (laparoscopy, resections and associated procedures) and the experience of the teams.

8

B. What are the main specific complications after liver resection?

The specific liver resection complications are the direct anatomical and/or physiological consequences of the removal of part of the hepatic parenchyma and the hepatic function associated with it. This definition does not include intraoperative incidents. The evaluation of the general severity of liver resection complications is evaluated both by the common classification of Clavien-Dindo [table 1] [5] and by specific classifications.

Table 1: Classification of surgical complications, according to Clavien-Dindo [5]

The main specific complications are:

1. Post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF)

In recent literature, post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) incidence is less than 10%, owing to improved perioperative management [6,7]. However, PHLF is perhaps the most devastating complication, accounting for up to 60% to 100% of deaths in some series [8,9].

In 2011, the ISGLS (International Study Group of Liver Surgery) defined PHLF as the “impaired ability of the liver to maintain its synthetic, excretory and detoxifying functions, which are characterized by an increased international

9

normalized ratio INR and concomitant hyperbilirubinemia (according to the normal limits of the local laboratory) on or after postoperative day 5 (POD5).” This group further differentiated severity by grades A, B, or C [table 2] [6]. The INR variable may be replaced by prothrombin time (PT), thus defining the “50-50 criteria” for PHLF: PT <“50-50% and hyperbilirubinemia >“50-50 μmol/mL on POD5 [10].

It is essential to define PHLF risk factors to identify the patients who could possibly develop such a complication before submitting them to a potentially deadly surgery. One way to look at risk factors is to delineate those related to patients and the disease from those related to intraoperative and postoperative management of patients [table 3] [11].

Table 2: Post hepatectomy liver failure grading, according to the ISGLS [11]

10

2. Bile leak

The incidence of bile leak is a substantial cause of associated morbidity, ranging from 2.6% to 33% [11]. Although known as the presence of bile in an intra-abdominal collection and/or in the drainage fluid, a definition was standardized by the ISGLS as a bilirubin level in a drain 3 times the serum concentration on or after POD 3, or the need for radiologic or operative intervention from a biliary collection or bile peritonitis [6]. Bile leak can originate directly from the surface of the hepatic section, from an area of ischemic necrosis, or from the extrahepatic biliary reconstruction site. The symptoms can be atypical (isolated fever, isolated chills, abdominal pain, ileus, etc), which can cause a delay in diagnosis. The specific severity of the bile leak can be classified into 3 grades [table 4]. Risk factors are summarized from [11] in table 5.

11

Table 5: Risk factors of bile leak following liver resection, modified from [11].

3. Post hepatectomy hemorrhage (PHH)

The reported incidence of post hepatectomy hemorrhage (PHH) varies considerably among published studies from 1–8% [6][12]. In 2011, the ISGLS set forth guidelines for the definition of PHH. The consensus definition was a drop in hemoglobin greater than 3 g/dL postoperatively compared with postoperative baseline (immediately after surgery) and/or any postoperative transfusion of PRBCs for a falling hemoglobin and/or the need for invasive reintervention (embolization or relaparotomy) to stop the bleeding. They further categorize the definition by grade based on the amount of blood units required [table 6]. [11][6]. PHH can occur early by direct hemorrhage from an arterial or venous ligation of the surface of the hepatic section or from a lymph node dissection, or secondarily by rupture of a false arterial aneurysm, most often in contact with an infected collection or a persistent bile leak.

12

Table 6: Grading of post hepatectomy hemorrhage, according to the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) [11].

4. Parenchymal necrosis

Parenchymal necrosis results from a complete devascularization (arterial and portal) of a hepatic area. It can be immediate if linked to an intraoperative devascularization, or delayed in case of an arterial and/or portal vascular thrombosis that appeared postoperatively. Necrosis can lead to intra-abdominal suppuration and/or bile leak. In case of widespread necrosis, this could induce liver failure.

13

C. What is a Root Cause Analysis (RCA) of adverse events?

James Reason proposed the "Swiss cheese" model to schematize the occurrence of adverse events [13–16]. According to this metaphor, in a complex system such as the patient management system, hazards are prevented from leading to severe complications, human losses included, by a series of barriers. Each barrier has unintended weaknesses, depicted by holes – hence the similarity with Swiss cheese. These weaknesses are inconsistent; the holes open and close at random. When all holes happen to align, the hazard reaches the patient and causes harm [fig3] [17]. Root cause analysis (RCA) studies the balance between barriers and holes to discover the causes of near misses and adverse events beyond human error. It is a systematic qualitative approach based on the honest and open reporting of incidents [18–21], starting with having a group of individuals that bring different insights and experiences, including those with intimate knowledge of how daily practice works [22].

The feasibility of a RCA remains a problem as it is resource-intensive [23]. A single RCA can take 20 to 90 person-hours and over $8000 to complete, [24,25], although that varies depending on the complexity of cases, the time required to conduct interviews and synthesize information, and the participation or not of a third party [19].

Contributory factors are defined as both proximal and latent causes of error. [26]. In the 9 steps to the realization of the RCA [fig4], as described by Charles et al, step 5 suggests that contributory factors should be in categories that address communication problems, policies, rules, procedures, and human errors leading to the event. The French High Authority for Health (HAS) (www.has-sante.fr) uses a commented version of the ALARM framework [table 7] that is

14

proposed by the Association of Litigation And Risk Management. It also includes it in the morbidity and mortality reviews (MMRs) that are considered a requirement in hospitals [23]. In oncology, the HAS recommends prioritizing cases of harm such as postoperative complications graded IV and V on the Clavien-Dindo classification, ICU readmissions, and unplanned postoperative hospital readmissions. It is unclear which investigation method is best; several tools can be uniquely combined into a coherent system to potentially optimize feasibility and effectiveness of a RCA by studying multiple medical incidents at once [24]. The aggregate RCA is one tool that has received little evaluation, but it has been recommended by some as a method to improve the bird's eye view of incidents across an organization [24], and as a way to identify trends to determine systemic root causes [27].

More generally, mixed methods research, combining or associating both forms of research (qualitative and quantitative), is a well-accepted research design [28]. The advantage of qualitative studies is that they use non-quantitative methods to contribute new in-depth knowledge and to provide new perspectives in healthcare [29]. A checklist - COREQ (Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) - was developed as a method for data collection in qualitative health research. Most publications regarding this type of research use interviews, then focus groups, which are defined as semi-structured discussions to explore a specific set of issues [29].

15

16

17

18

19

A. Type of study

This is a retrospective study that used mixed quantitative and qualitative analysis.

B. Research team

The research team consisted of two members.

1. BA, study facilitator, Professor of surgery at the NIO, supervisor of hepatobiliary surgery program, and co-founder of the local morbidity and mortality review (MMR) meetings.

2. HK, study co-facilitator, MD student. Further characteristics are in table 8.

C. Endpoints

The study's primary endpoint was to identify contributory factors to the occurrence of severe complications after liver resection performed at the National Institute of Oncology (NIO) in Rabat (Morocco). Severe postoperative complications were defined as Clavien Dindo >IIIa during the first 90 post operative days (PODs).

Secondary endpoints were to:

Detect trends in the occurrence of severe complications during the study

period.

Identify recovery factors: defenses that guard against clinical incidents

and aid recovery from potential problems [31]).

Identify potential corrective actions: measures whose application

20

D. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The first 100 consecutive patients who underwent liver resection starting from January 2018 (start of liver resection program) at the National Institute of Oncology (NIO) in Rabat (Morocco) were included in the quantitative analysis. Among these, patients who developed severe postoperative complications (Clavien Dindo >IIIa) during the first 90 post operative days (PODs) were included in the qualitative analysis.

Patients who underwent liver resection as a local extension of another organ resection, and those who were first scheduled then unqualified for surgery were excluded from the study.

E. Context

The National Institute of Oncology (NIO) is an academic anti-cancer center that is part of the Ibn Sina University Hospital in Rabat (Morocco). Since 1984, the NIO has been the only public national facility that offers care involving medical oncology, radiotherapy and surgery, all on the same site. The NIO treats nearly 6,000 new patients each year, with almost 12% of those for digestive cancers. In 2014, a dedicated pathway for digestive cancer surgery [fig5] was created for patients by a multidisciplinary team of digestive surgery specialists, anesthesiologists/intensivists, gastroenterologists/endoscopists and nurses. Specialized surgical oncology programs have been established for specific organs since then. The first programs were colorectal surgery, gastric surgery and peritoneal surface surgery including hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy procedure (HIPEC) since June 2018.

21

expected to include a liver transplantation program from living donors by 2020 with the support of Paul Brousse Hospital (Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, France, (www.centre-hepato-biliaire.org). Before the implementation of this program, the liver surgery activity was low, with records showing only 7 liver resections in the period between 2016-2018 .

A continuous quality improvement program revolving around quality of care and patient safety has been gradually implemented at the NIO over the study period onwards [fig6]. This program has benefited notably from the support of the Lalla Salma Foundation (www.contrelecancer.ma) through the funding of two projects. The first was a training program of the different teams (surgery, anesthesia, OR, nurses) to the quality management methodology, and the second was a visitation of the surgical department from Dr. Jaap Snellen, surgical quality expert and former quality auditor at the Dutch Surgical Association. Currently, there is a quality improvement committee at the NIO that is comprised of medical and paramedical staff members who organize weekly and quarterly MMRs for a root cause analysis of reported incidents.

22

Figure 5: Digestive cancer surgical pathway for patients at the NIO. MDM, multidisciplinary meeting.

23

24

F. Quantitative analysis

1. Data collection

Data related to liver resection cases were gathered prospectively on a dedicated digitized database, and included preoperative variables, intraoperative variables, and postoperative variables. These variables were assumed to impact the occurrence of postoperative complications. For all patients who underwent liver resection, follow-up after hospital discharge was conducted during postoperative consultations or through patient phone calls.

Preoperative data: Patients' demographics, body mass index (BMI),

comorbidities, preoperative blood work and medical imaging, diagnosis, neoadjuvant treatments received (e.g: chemotherapy, radiofrequency therapy, portal venous embolization, and chemoembolization).

Intraoperative data: Type and date of surgical procedure, surgical

approach, use of intraoperative ultrasound, associated surgical procedures (e.g: colorectal resection, biliary reconstruction, vascular reconstruction), estimated blood loss, number of transfusions received, clamping duration, operating time.

Postoperative data: Complications following liver resection (liver failure,

hemorrhagic complications, bile leak, intra-abdominal collections, wound infections, ascitis, pulmonary complications, cardiovascular complications, renal and urinary tract complications and neurological complications), and postoperative in-hospital length of stay and intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay.

25

2. Statistical analysis

a. Trends in the occurrence of severe complications

The Cumulative Sum technique (CUSUM) is a statistical analysis that serves to monitor the success and failure of a technical skill and detect potential trends. The results are presented in a CUSUM graph, which is basically a graphical presentation of the course of consecutive outcomes over time [32]. To perform the CUSUM technique, we proceeded as follows:

For each patient, the difference between the expected outcome (EO) and the observed outcome (OO) was calculated. The observed outcome is 0 if the patient had no major complication and 1 if the patient had a major complication. The expected outcome is the probability of the occurrence of a major complication for each patient. In the study, we chose 15% or 0.15 as expected outcome.

Therefore:

- If the patient had a major complication: 0.15 - 1 = - 0.85 - If the patient had no major complication: 0.15 - 0 = 0.15

- Then, we calculated for each patient the CUSUM score in the following

manner:

- For the first patient: Score(1) = EO(1) - OO(1)

- For the following patients: Score(t) = (EOt - OOt) + Score(t-1) where

OE(1) is the observed outcome for the first patient; OO(1) is the expected outcome for patient 1.

26

Score(t) is the CUSUM score for any patient. EO(t) is the expected outcome for patient t. OO(t) is the observed outcome for patient t.

Score(t-1) is the CUSUM score of the previous patient (t-1).

On the graph, the x-axis represented the cases in a chronological order and the y-axis the CUSUM score for each patient (see example table below)

Patient 1 OO1 - EO1 OO1 - EO1

Patient 2 OO2 - EO2 (OO2 - EO2) + Score(1) Patient 3 OO3 - EO3 (OO3 - EO3) + Score(2)

The CUSUM graph plots cumulative sums of the deviation between the observed outcome and expected outcome [33]. Control limits are located on both sides of thecenter line that is itself located at zero (y=0). The plotted points should fluctuate randomly around zero. If an upward or downward trend develops, the process mean would shift and the process may be affected by special causes. Plotted points that are located beyond the control limits indicate that the process is out of control. Turning points, points at which trends appear, could be revealed on the CUSUM graph and be indicative of statistical significance in the results.

b. Demographic and clinical variables

Demographic and clinical variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were presented with a mean value ± SD or a median with interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed with frequencies and percentages.

27

c. Comparison of groups of patients

To compare:

characteristics (demographics, indications, procedures) and complication

types of two groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not, and

characteristics of patients before the potential turning points shown by the

CUSUM chart vs. those of patients after the turning points,

a univariate analysis was performed using the T student test, Mann–Whitney test or the Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. All p values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22).

G. Qualitative analysis

1. Tool selection and customization

The choice of the ALARM framework was due to the healthcare team's familiarity with its application during the morbidity and mortality reviews (MMRs). For the purpose of this study, some revision was applied to the ALARM framework, as recommended by [30]. Fifty triggering questions were therefore adapted as a questionnaire from the detailed french commented ALARM framework of the HAS (see appendix), covering all seven headings: patient factors, task factors, individual staff factors, team factors, work environmental factors, organizational and management factors and the institutional context factors.

28

2. Participant selection

Participant sampling was purposive, which means that it involved participants who shared particular characteristics - the RCA training via MMRs - and had the potential to provide rich, relevant and diverse data pertinent to the research question. [29,34,35]. Six clinicians of two different specialties and different years of experience were therefore selected from the MMR board, including the study facilitator. The head nurse and the nurse in charge of coordination of care in surgical patients were asked to participate in the focus group. Detailed characteristics of the participants are found in table 8.

29 Table 8: Characteristics of the research team and participants.

30

3. Event storyline

A storyline was created for each case in a powerpoint presentation to depict the timeframe of care associated with the severe complications that occurred after liver resection. Data were collected from the digitized database and completed from patients’ respective hard copy files. Interviews were conducted in case of missing information to obtain the most comprehensive case reports.

In regards to the preoperative phase, the information provided on the presentation concerned patient description, case history, physical examination, results and/or copies of documented preoperative medical imaging, pre-anaesthetic consultation reports, and treatment plan decisions, whether they were made in the daily staff meetings, or in the weekly multidisciplinary meetings. To help further understand the cases, a copy of the surgical report was also attached, along with postoperative management measures that were taken to treat complications that have occurred in the surgical ward and/or the ICU. BA (surgery) and GA (ICU) validated technical data present in the event storyline.

4. Individual analysis

After the story was outlined for each case of postoperative complication >IIIa , the study participants were asked to first review all 15 presentations that were sent out individually, then answer all 50 triggering questions from the customized ALARM framework questionnaire [table 9] if applicable. When a piece of information was judged missing, a non applicable (NA) option was selected. They were also asked to propose recovery factors and corrective measures to the best of their ability to help prevent the same event from happening again, or better manage it in the future. A deadline of 10 days was set after receipt of the case reports.

31

32

5. Consensus

a. Workshop preparation:

The research team organized a pre-workshop reunion in order to examine the preliminary outcome of the RCA and reach an agreement regarding the participants’ statements. To that end, these latter were randomized and reviewed anonymously to give them equal value. For each question, we consolidated all answers into one unified response, without taking the NA answers into account. All refuted answers were justified by a comment that was later shared in the consensus workshop (focus group) to get the participants’ validation if they agree. If a comment could not be provided in case of diverging opinions between the research team members, the questions were left to be deliberated in the workshop. The goal was to eventually settle on the incidents' contributory factors. For future reference, we call trigger answer one that incriminates a contributory factor in the questionnaire (It could be “yes” or “no” depending on the context).

b. Consensus workshop:

The research team scheduled a focus group over a month in advance to gather the participants for further deliberation. In fact, the first objective of this workshop was to validate the decisions that were made by the research team during the pre-workshop reunion, and the second was to discuss the remaining disagreements that could not be straightened out and justified. During the workshop, cases were handled one by one. The co-facilitator first gave a brief reminder of the case to refresh the team's memory before the facilitator gave a rundown of the contributory factors that were collected from the participants'

33

suggestions anonymously. The remaining opinion divergences that the research team had previously marked during the pre-workshop were also discussed, and disagreements were cleared out after defending the opinions with a valid justification.

6. Aggregate RCA

Once a global consensus was reached regarding contributory factors for each case, the research team performed an aggregate root cause analysis. This means that for all 15 cases together, patterns of contributory factors that augmented the risks of the occurrence of severe complications were reviewed collectively, on a question by question basis initially, then analyzed by subcategory and category.

34

35

By December 15th, 2019, one hundred consecutive liver resections were performed starting from January 1st, 2018 (<24 months). During this period, severe complications >IIIa occurred in fifteen patients (15%) by POD90. The distribution of in-hospital and POD90 complication severity according to the Clavien-Dindo classification in all hundred patients is represented in figure 7. The summary of each case of severe complications is reported in table 10.

Figure 7: Distribution of in-hospital and POD90 complication severity in 100 patients, according to the Clavien-Dindo classification

36

37

A. Quantitative analysis

1. Comparison of the characteristics of groups of patients who

developed severe complications vs. patients who did not

A comparison of characteristics of groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not is summarized in table 11.

Performance status >1 (6.7% vs. 1.2%; (p=0.032)) and diabetes (33.3% vs. 8.2%; p=0.016) were significantly more present in cases with severe complications.

38

Table 11: Comparison of the characteristics of groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not. Significant factors (p≤ 0.05) are in bold font.

39

2. Comparison of complication types in groups of patients who

developed severe complications vs. patients who did not

A comparison of complication types in groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not is presented in table 12.

Intra-abdominal collections (40% vs. 8.2%; p=0.004), overall pulmonary complications (40% vs. 11.8%; p=0.014), and cardiovascular complications (20% vs. 1.2%; p=0.011) were significantly more frequent in cases with severe complications compared to those without severe complications.

Table 12: Comparison of complication types in groups of patients who developed severe complications vs. patients who did not

40

3. Turning points

The graph of the Cumulative Sum (CUSUM) results [fig] showed a consistent decrease of the occurrence of severe complications starting from the 49th case, consequently determining the turning point.

Figure 8: CUSUM graph showing a single turning point starting from case 49, corresponding to a decrease of the observed occurrence of severe complications after liver resection. (Turning point indicated by red arrow).

41

4. Comparison of characteristics in cases after turning point vs.

before turning point

A comparison of characteristics and complications >IIIa of the groups of cases from the period before the turning point (Period 1) vs. the period after (Period 2) is reported in table 13.

Diabetes was significantly more frequent in period 1 compared to in period 2 (16.3% vs. 7.8%; p=0.016), while cirrhosis was more frequent in period 2 (17.6% vs 4.1%; p=0.03).

In regards to liver resection indications, the only significant difference was in the rate of hepatocellular carcinoma that was more frequent in period 2 (17.6% vs. 4.1%; p=0.03). Chemotherapy cycles >6 were also significantly more frequent in period 2 (29% vs. 6%; p=0.02)

Digestive resection and colorectal resection more specifically were significantly more frequent in period 1 with rates (20.4% vs. 2%; p=0.003) and (14.3% vs. 2%; p=0.003) respectively. Severe complications (complications >IIIa) were also significantly more frequent in period 1 (24.5% vs. 5.9%; p=0.009).

42

Table 13: Comparison of characteristics and number of severe complications (CD>IIIa) in the first cases operated before the turning point (49th case) vs. cases operated after the turning point.

![Table 1: Classification of surgical complications, according to Clavien-Dindo [5]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/15038987.691147/38.892.122.774.393.631/table-classification-surgical-complications-according-clavien-dindo.webp)

![Table 2: Post hepatectomy liver failure grading, according to the ISGLS [11]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/15038987.691147/39.892.104.817.698.953/table-post-hepatectomy-liver-failure-grading-according-isgls.webp)

![Table 4: Grading of bile leak after hepatobiliary surgery, according to the ISGLS [11]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/15038987.691147/40.892.112.785.575.729/table-grading-bile-leak-hepatobiliary-surgery-according-isgls.webp)

![Table 5: Risk factors of bile leak following liver resection, modified from [11].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/15038987.691147/41.892.160.734.99.503/table-risk-factors-bile-following-liver-resection-modified.webp)

![Figure 3: Swiss cheese model by James Reason published in 2000 [17]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/15038987.691147/45.892.101.801.322.690/figure-swiss-cheese-model-james-reason-published.webp)

![Table 7: The ALARM framework of contributory factors, from [30]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/15038987.691147/47.892.112.808.176.876/table-alarm-framework-contributory-factors.webp)