HD28 .M414 no. '^^2'^

9o

DfeVVtiYWORKING

PAPER

ALFRED

P.SLOAN

SCHOOL

OF

MANAGEMENT

deterjMinants of electronic integration in the insurance industry: an empirical exaimination

Akbar Zaheer and N. Venkatraman Working Paper #3220-BPS Supercedes ^ 3165-BPS November 1990

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE

OF

TECHNOLOGY

50MEMORIAL

DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE,

MASSACHUSETTS

02139

deterjMinants of electromic integration in the insurance industry: an empirical examination

Akbar Zaheer and

N. Venkatraman

Working Paper #3220-BPS November 1990

<

Determinants

of Electronic

Integration

inthe

Insurance

Industry:

An

Empirical

Examination

Akbar

Zaheer

E52-509

MIT

Sloan School ofManagement

Cambridge,

MA

02139.(617) 253-3857

and

N.

Venkatraman

E52-537

MIT

Sloan School ofManagement

Cambridge,

MA

02139.(617) 253-5044 Bitnet:

NVenkatr@Sloan

Draft:

June

7, 1990Revised:

November

19, 1990Acknowledgements:

We

thank theManagement in theJ990s Research Program and the CenterforInformation Systems Research Sloan School ofManagement, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for financial supportand the principalsin the independentinsurance agencies

who

provided data.Special appreciation isextended toProfessorBenn KonsynskiofHarvard BusinessSchoolformakingthedatasetof his projectconducted with

Ramon

O'Callahanavailabletousfortesting therobustnessofourresults in a complementaryresearchsetting.JohnCarroll,MichaelCusumano,Rebecca Henderson,

Lawrence Lohand Srilata Zaheer, in addition to the Editor and the reviewers read earlierversions and

made

valuable suggestions. The authorsalone areres{X)nsible forthefinal version.Determinants

of Electronic Integration

inthe

Insurance

Industry:

An

Empirical

Examination

Abstract

Electronic integration

—

aform

of vertical integration achievedthrough

thedeployment

of dedicatedcomputers

and communication

systems

between

relevantactors in the adjacent stages of the value-chain

~

isan

important concept toorganizational researchers since it provides a

new

mechanism

formanaging

vertical relationships.Drawing

upon

on

transaction costs, a set ofhypotheses

on

thedeterminants of the degree of electronic integration of insurance agencies is tested in a design

comprising

two

independent

samples: (a)one

with 143 propertyand

casualty

(P&C)

insurance agencies involved in the commercial lines business— who

are interfacedwith

a single focal carrier via a dedicatedcomputer-based

system;and

(b) a

second

with arandom

sample

of 64independent

agencies interfaced with insurance carriers for personal lines business.The

results across both settings did notsupport

the hypotheses, thus raisingsome

theoretical issueson

the applicabilityof the transaction cost

model

in situations affectedby

information technology applications. Implicationsand

extensions are offered.Key

Words:

Information technology; vertical integration; electronic integration; organizational governance; insurance industry—

commercial

lines; personal lines.Introduction

This

paper

isconcerned

with the role of information technology ininfluencing the pattern of interfirm

arrangements

in a marketplace. It buildsfrom

the extensive

body

of researchon

the design of interfirm relationships that lie along acontinuum from

markets to hierarchies (Williamson, 1985) to a specific contextwhere

such

relationships arefundamentally impacted

by

information technology applications (see for instance,Cash

and

Konsynski, 1985; Keen, 1986; Johnstonand

Lawrence,

1988; Rockartand

ScottMorton,

1984). Specifically,we

areconcerned

with the relevanceand

applicability of the transaction costs perspective tounderstand

the pattern of vertical controlbetween

insurance carriersand

independent

agents.^

To

achieve this objective,we

develop

amodel

of electronic integration~

defined as a specificform

of quasi-integration within the class ofmechanisms

for vertical controls—

and

derive a set of its determinantsfrom

the transaction costtheory that has

been

recentlyargued

tobe

relevant for settingsimpacted

by

information technology (Bakosand

Treacy, 1986;Malone,

Yates,and

Benjamin, 1987;demons

and

Row,

1989);more

specifically, interorganizational information systems (lOS). Thismodel

is tested using a research designcomprising

two

independent

samples: (a) 143 propertyand

casualty(P&C)

agents dealing with commercial lines—

who

are interfaced with a single focal carrier via a dedicatedcomputer-based

system;and

(b) asecond

with arandom

sample

of 64independent

agents interfaced

with

insurance carriers for personal lines.Theoretical

Considerations

We

develop our

theory as follows. First,we

provide

an

overview

of the researchstream

on

the differentmechanisms

for organizationalgovernance

-

suchas vertical integration, partial equity

ownership,

joint ventures,and

technology^Theagent(oragency)refers to the independent organization that formsthedownstream link

licensing

-

to argue for conceptualizing 'electronic integration' as a specificform

ofquasi-integration that exploits

emerging

information technology capabilities.Subsequently,

we

discuss the role of transaction costs in the research streamon

vertical integration.The

impact

of information technology in influencing transaction costs is explored next todevelop

a researchmodel

of critical determinants of electronic integration.Mechanisms

for OrganizationalGovernance

In simple terms, the

two

traditionalmechanisms

for organizationalgovernance

are the firm (or the hierarchy)and

the market (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1975)—

where

a firm is defined in terms of those assets that itowns

or overwhich

ithas control

(Grossman and

Hart, 1986; see also Pfefferand

Salancik, 1978)and

isengaged

in transactions with other firms in the market.The

firm coordinates the flow of materialsthrough

adjacent stages of a business processby

means

of rulesand

procedures

established within the hierarchy.The

market,on

the otherhand,

coordinates the flow of materials

between

independent

economic

entitiesthrough

the use of the price

mechanism

reflecting underlying forces ofsupply

and

demand.

Taking

the firmand

themarket

as 'pure' forms, several intermediategovernance

mechanisms

have been proposed

over the years.These

include: long-termrelational contracts (MacNeil, 1980; Stinchcombe, 1990), joint ventures (Harrigan,

1988)

and

quasi-firms (Eccles, 1981)which

canbe

more

formally classified as either bilateral or trilateralgovernance

(Williamson, 1985) orsimply

viewed

as 'quasi-integration' (Blois, 1972). Collectively, thesemechanisms

areused

by

organizations to maintain control over critical resources necessary for their success (Pfefferand

Within

thesegovernance

mechanisms,

vertical integration^ hasbeen an

area of considerable research along multiple theoretical perspectives (see Perry, 1989 for acomprehensive

review), but the transaction costmodel

(Williamson, 1975, 1985) isthe

dominant

one

(Walker, 1988).Hence,

we

discuss the role of transaction costs in vertical integration research next.The

Role

ofTransaction Costs in Vertical IntegrationResearch

The

generalargument

of transaction cost analysis is that vertical integrationis preferred over

market exchange

when

thesum

of transactionand

productioncosts of

market exchange

exceed those of hierarchy. Critical determining conditionsfor high transaction costs are

environmental

or transactional complexityand

the existence of transaction-specific assets (Williamson, 1975, 1985, 1989; Klein,Crawford,

and

Alchian, 1978).Other environmental

and

behavioral considerations theorized to exacerbate transaction costs are informationasymmetry due

tobounded

rationality,

and opportunism combined

with smallnumbers

exchange.The

general proposition relating transaction costsand

governance

mechanisms

hasbeen

refined over the yearswith

greater distinctionsamong

the various types of asset specificity (transaction-specificknow-how;

site specificity; physical asset specificity;and

dedicated assets), as well as a greater recognition of the existence

and

viability ofintermediate

mechanisms

ofgovernance

(Williamson, 1985).This theoretical proposition has

been

increasingly subjected to empirical research. For instance, constructs derivedfrom

thismodel have

been adopted

as the determinants of:backward

integration(Monteverde

and

Teece, 1982; Masten, 1984;Masten,

Meehan, and

Snyder, 1989),forward

integration into distribution (Johnand

^Following(Perry, 1989), vertical integration isdefined as a condition in whicha firm

"encompasses two singleoutput productionprocessesinwhicheither(1)theentireoutputof the

'upstream' processis employed aspart orallof thequantity ofone intermediate inputintothe

'downstream' process, or(2)theentirequantityofoneintermediate input intothe 'downstream'

process isobtained frompart orallof theoutput ofthe 'upstream' process. "(p.l85,italics in the original).

Weitz, 1988), preference for internal versus external suppliers

(Walker

and

Poppo,

1990), sales force integration (Anderson, 1985;

Anderson

and

Schmittlein, 1984),make

versusbuy

incomponents

(Walker

and

Weber,

1984), contract duration (Joskow, 1987)and

joint ventures (Pisano, 1989).The

empiricalapproach

totransaction cost research has generally

been

one

of assessingwhether

interfirm relationshipsconform

to predictionsfrom

transaction cost reasoning. For themost

part, there hasbeen

consistent empirical support for theoretical propositionsdrawn

from

the transaction costframework.

Transaction Costs

and

Information

Technology

Recent

developments

in information technology~

especiallylOS

(Barrettand

Konsynski, 1982)—

have

the potential to redefine the structuraland

competitivecharacteristics of the marketplace (Cash

and

Konsynski, 1985).More

specifically,following

Malone

et al. (1987), information technology could be expected to give riseto three sets ofeffects:

(a) electronic communication effect

—

through

reduced

cost ofcommunication

whileexpanding

the reach (timeand

distance);(b) electronic brokerage effect -- increasing the

number

and

quality ofconsiderations of alternatives,

and

decreasing the cost of transactions; inother

words,

there is reduction in search costs in themarketplace through

lower

transmission cost while reaching a highernumber

and

quality of alternative suppliers.These

effects lead tolowered

costs of coordinationbetween

organizations in a market, thus reducing the transaction costs of exchange;and

(c) electronic (process) integration effects -- increasing the

degree

ofinterdependence

between

the set of participants involved in the business processes; this ismore

than the administrative costs of streamlining data entry across organizational boundaries, but includes the ability tointerconnect adjacent stages of business processes (such as design, tooling

and

manufacturing) tobe

on

an

integrated platform.However,

theimpact

of these effects varies according to the specificform

oflOS deployed

--which

canbe

either acommon

infrastructurethrough

a third-partysystem

(i.e.,ANSI

X.12 standards) or a unique, proprietary system installed todevelop

and implement

a firm-level strategy (e.g., Baxter'sASAP

network

orAmerican

Airlines'SABRE

network). In theformer

case, the benefits cannotbe

differentially appropriated

by

a firm since its competitorshave

access to thesame

technological capabilities, while in the latter case the specific firm chooses to

commit

its strategic investments

with

the expectation of deriving firm-level advantages. Let us explore the implications ofsuch

trendson

the transaction costperspective,

where

costs arisefrom

searchand

information-gathering,and

from

writing,

monitoring

and

enforcing contracts inan exchange

relationship; these costsdetermine

theform

of agovernance

relationshipbetween

two

organizations.Efficiency is

compromised by

informationasymmetry and

coordination costs,which

are

among

the elements of transaction cost that are likely tobe

decisively influencedby

the capabilities ofcomputers

and advanced communication

technologies (Bakosand

Treacy, 1986). Consequently, there is a compelling logic to consider therelevance of transaction costs as a theoretical

anchor

inunderstanding

electronic integration.In this vein,

demons

and

Kimbrough

(1986)argue

that competitiveadvantage

could resultwhen

the transaction costs in dealingwith

some

competitorswere

reduced

inan

asymmetricmanner.

Thus, it is entirely possible for thedeployment

of a unique, proprietary (asopposed

to acommon)

IT application toreduce

the transaction cost for the particulardyad

relative to othermodes

of exchange.Extending

this logic,demons

and

Row

(1989)enumerate

a set of restructuring types that includes vertical integration. Indeed, their discussion ofvirtual

forward

integration in the case ofMcKesson,

adrug

distributor'snetwork

integration.

They go

on

to offer a set of reasons for theemergence and

benefits of this type of integration in the marketplace.Thus,

we

argue

that the concept of electronic integrationand

its determinants isfundamentally

rooted in transaction costs that areimpacted

by lOS

capabilities.Hence,

we

derive a set of hypotheseson

the determinants of electronic integrationdrawn

from

the transaction costmodel and

empirically testthem

usingtwo

different

samples

ofindependent

insurance agents electronically-interfacedthrough

dedicated

lOS

in thecommercial

and

personal lines respectively in the propertyand

casualty segment.Research

Model

In this section,

we

translate theabove

theoretical considerations to the specificresearch setting.

We

describe the particular nature of electronic integrationand

identify its determinants, todevelop

a researchmodel

with a set of testablehypotheses.

Patterns of ElectronicInterconnections in the Insurance Industry

The

insurance industry in theUSA

iscomprised

oftwo

major

markets:(a) the life

&

health;and

(b) the propertyand

casualty(P&C)

—

eachwith

itsdistinctive set of products

and

channels of distribution. Thisstudy

isconcerned

with theP&C

insurance market,which

offers protection againstsuch

risks as fire, theft, accidentand

general liability.The

P&C

market

further breaks out into personaland

commercial

segments, theformer

covering individuals (automobileand

homeowner

insurance forexample)

and

the latterindemnifying commercial

policy holders against general liabilityand

workers' compensation.The

industry generatedabout

$200 billion inpremiums

in 19883. In the two-part research design (tobe

discussed later),we

focus

on

both segments.While

some

carriers utilize 'direct writing', inwhich

field offices dealdirectly

with

the customers, the distribution ofcommercial

P&C

insurance occurs principallythrough

independent

agents.These

agents typicallyrepresent multiple carriers

and

arecompensated

on

conomission terms.However,

there is a trendwhereby

independent

agents rely exclusivelyon

a single carrier or dealwith

a smallnumber

of carriers, thereby blurring thedistinction

between

direct writingand

theindependent

agency forms

of distribution.4The

upstream market

is highly competitive since there arefew

barriers to entryand

includes over 3600 insurance carriers.These

conditions of fragmentationand low

market

power

have

resulted in intense price-based competitionand

a cyclical pattern,with

marginal players exiting themarket

during

industrydownturns and

entering at upturns.Approximately

300carriers

have

multiple offices (Frostand

Sullivan, 1984)and

asmany

as 20 to30 are

major

carriers accounting forabout

50%

of revenues.Downstream

activities in this industry involving agents are similarly highly competitive.Further,

both

theupstream

and

downstream

activities areon

the threshold of significant transformation along several dimensions: (a) consolidation of agency operations, reflecting a reduction in thenumber

ofindependent

agentsby

asmuch

as

25%

during

1980-86^ toaround

42,000; (b) forward integration by carriers,through

mechanisms

such

as direct-writing,commissioned employee

arrangements,and

exclusive agencies;and

(c) increasing back-office automationand

deployment oflOS

with

carriers,with

asmany

as40%

of allindependent

agents interfaced with at least3Standard

&

Poor'sindustry surveys: InsuranceandInvestment Banking. '^Frominterviewsand backgroundresearchbythe authors.10

one

insurance carrier^.These

trends, taken together, highlight theneed

to set therole of electronic integration against a

backdrop

offundamental

transformations inthe marketplace.

Common

versusUnique

Interfacing.Common

standards for electronic policy information transferbetween

insurance carriersand

the insurance agentshave been

set

by

the industry organization,ACORD,

and

in 1983, the InsuranceValue

Added

Networks (IVANS)

was

established.Following

the earlier discussionon

transactioncosts

and

information technology,we

argue that thedevelopment

and

installationof

common

standardsand

acommon

network

will favor theindependent

agentsby

creating the capability to interface with multiple,

competing

carriers. Specifically, the agents could reduce theirdependencies

on

anarrow

setof carriers, while exploiting the full benefits of electronicbrokerage

effects en route to the creation ofan

electronic market.

In contrast, the

deployment

of aunique

(i.e., proprietary)lOS

allows the focal carrier tomore

tightly couple its business processes with those of the agentand

expand

the scope of operations overwhich

it can exercise control. This is akin towhat

Konsynski

and

McFarlan

(1990)term

an

'information partnership'which

can confer benefits of scalewithout

ownership. In otherwords,

thedeployment

ofunique

lOS

between

a focal carrierand

a set ofindependent

agents is aform

of 'vertical quasi-integration' (Blois, 1972), specificallytermed

here as 'electronic integration' that ismore

'hierarchy-like' than 'market-like' (Williamson, 1985).Further,

we

argue

that within the hierarchy-likegovernance

mechanism

ofelectronic integration there exists a

continuum which

rangesfrom

agents that rely exclusivelyon

a single carrier (approximating thepure

hierarchicalform

of 'direct11

writing') to those agents that deal with multiple carriers

and

depend

to a lesserextent

on any

single electronically interfaced carrier.An

empiricalassessment

of the determinants of electronic integrationshould

delineate (a) the focal unit of observation in the dyadic relationship; (b) the specific

conceptualization of electronic integration;

and

(c) the set of constructs that are expected to explain the pattern of electronic integration. This is discussed next.The

FocalUnit

ofObservation

A

fundamental

issue in this research study is the identification of the focalactor that is

making

the integration decision. Forexample,

when

Monteverde and

Teece (1982)contended

that the specific assets (especially,human

assets) play asignificant role in 'internalizing' production, they focus

on

the integration decision of thetwo

automotive

firms.The

specificargument

is that "relyingon

suppliers forpreproduction

development

service willprovide

the supplierswith

an

exploitable first-moveradvantage"

(1982;p

212)and

vertical integrationby

the automakers

is,therefore,

an

efficient response to countersuch

potential opportunistic behavior.Similarly,

Walker

and

Weber

(1984) focusedon

a set of decisions relating to'make

or buy' of

automotive

components

to predict the extent of vertical integration ofan

automaking

firm.These

studies~

typical ofmuch

of empiricalwork

on

transactioncosts in vertical integration

~

areconcerned

with a set of activities ofone

ormore

focal firm(s) to explain the level of integration within its boundaries.If

we

were

toadopt

thesame

approach

for the insurance industry, thenwe

should

look atone

ormore

insurance carriersand

evaluate their level ofintegration of activities

such

as reinsurance, rating or direct writingthrough

the transaction cost lens.Such an

effortwould

be

a straightforward study ofverticalintegration in the insurance industry.

However,

our

focus ison

the roleplayed

by

aspecific

lOS

platform that allows a focal carrier tobe

interconnectedwith

a set of12

mode

but arenow

electronically-interfaced. Consequently,we

evaluate thedeterminants of electronic integration of the insurance agents

by

focusing only onthose activities that are carried out via this lOS. Conceptualization of Electronic Integration

A

stylized process of the electronicintegrationbetween

a focal carrierand

theindependent

agents is as follows^: Tjrpically, the carrier initiates the process of deploying anlOS

by

offering it to a set ofindependent

agents that distribute the carrier's products. In this industry, the initialhardware

and

software costs associated with these proprietary systems are generallyborne

by

the carrier asan

inducement

to the agent to accept the system.

The

agent~ who

asnoted

above

is operating in a marketplace characterizedby

consolidation—

has tomake

a choice either to reject thesystem

and

continue to operate in a 'market-like'mode

or accept thesystem

and

become

more

'hierarchy-like.'^Subsequent

to the interfacing decision, the agent invests resources (timeand money)

todevelop

specific capabilities toconduct

theirbusiness processes via this system. This is

complemented by

technicaland

procedural advice

and

supportfrom

carriers. This creates procedural (specificknow-how)

as well ashuman

asset specificity (through training forsystem

use) relative tothe carrier

deploying

the lOS. In order to prevent opportunistic appropriation of these specific assets, the agentmay

attempt to safeguard these investments intransaction-specific assets by channelizing a greater share of the agency's business to the carrier. This action

makes

it costlier for the carrier to terminate the relationship.''itis importanttounderscorethatthetransactioncost logicdoesnotdehneate a 'processmodel'. Giventhe complexityofthe various transactioncostdeterminants, somedirectly attributable to the insurancecarrierand othersto theinsuranceagents,

we

providea stylizeddescription ofthe processof thechoiceofthe governancemode,i.e.electronic integration. Theempirical

tests,however, follow thegovernancechoiceunderstaticequilibriumandisconsistentwith

prior work inthis area.

^Thisstudyisnotconcerned withthe agents' decisiontoeitheracceptthe interfacingsystemor

not. Since not all agents routinely acceptthe interfacingsystem, an interesting research areais

to develop a model that explains and predicts theaccqjtance of the interorganizational system.

13

This situation is

somewhat

analogous

to the franchisingsystem

~

where

franchiseesmay

be

required tocommit

investments in transaction-specific capital,such

as renting landfrom

the franchiser,making

it costly for the franchisees toterminate the

agreement

(Klein, 1980)termed

a 'hostage' situation (Williamson,1985). In this setting, the insurance carrier provides the

lOS

(usually bearingmost

ofthe

hardware,

softwareand

setup costs)which

compels

the agent to invest in specific assets related to the customization of business processes. This ex-post 'hostage'situation subsequently requires that the agent channelize

more

business to the lOS-linked carrier.In a similar vein,

Heide

and

John

(1988)argue

that for a manufacturer'sagency

dealing with a large principal, substantial transaction-specific assetsmay

be

created

by

theagency

(such as specific training,and

knowledge

of the principal'sproducts, policies

and

procedures). In such a case, the theoretically-predicted option of vertical integration to safeguard specific assets is "simply irrelevant...because small agencies cannot consider vertical integration as a feasible alternative" (p.21).The

explicit recognition of the perspective of the smaller firm in thedyad

distinguishes the present researchfrom

studieson

the unilateral integration decisions of largecompanies

in industriessuch

as automobiles(Monteverde

and

Teece, 1982;Masten

et al. 1989) or aerospace (Masten, 1984).Given

our

focuson

theindependent

agentsmaking

thegovernance

decision,we

conceptualize electronic integration as the percentage of business directed to thefocal carrier through the hierarchy-like electronic channel. This is consistent with:

(a)

John

and

Weitz

(1988),who

view

forward

integration as "percentage of direct sales to end-users" (p 345);and

(b)Masten

et al (1989),who

conceptualizebackward

integration as "the percentage ofcompany's

component

needs

produced

under

thegovernance

of the firm" (p 269). This conceptualization is superior to themore

14

bypassed

by

researchers in favor of predicting higher orlower

pointson

acontinuum

between

thesetwo

pure forms

(e.g. Pisano, 1989).Determinants

of Electronic IntegrationIn this section,

we

identify a set of constructs consistentwith

the transactioncosts

model

as critical determinants of electronic integration.Asset

Specificity. This is adominant

source of transaction costs since asset specificity transforms the transaction context into a smallnumbers

bargainingsituation.

Within

the various sources of asset specificity (Williamson,!985),we

argue that

human

asset specificity, exemplifiedby

specialized trainingand

learning,is an important source of asset specificity in service operations,

such

as insurance.Anderson

(1985) considered specializedhuman

knowledge

as reflecting asset specificity in sales operations,which

is similar to the extent of customization ofcarrier-specific

procedures

for electronic interfacing carried outby

the insurance agent. In a similar vein,John

and

Weitz

(1988) in their researchon

distribution channelsnoted

that themost

relevantform

of asset specificity in this context is thelevel of training

and

experience specific to the product-line.Further, it is clear that

unique

lOS

such as thewell-known

ASAP

system

of Baxter Healthcare (previously,American

HospitalSupply

Corporation)embody

"features built into the...system to

customize

thesystem

to a particular hospital'sneeds, in effect creating a procedural asset specificity in the relationships

between

thebuyer

and

seller"(Malone

et al., 1987;emphasis

added). In addition, theseproprietary systems create technological asset specificity akin to dedicated assets since

they cannot

be

easily shifted towork

with other insurance carriers. Thus, theimplementation

of a carrier-specificlOS

creates non-redeployable specific asserts(human,

proceduraland

technological) that are costly to switch to anew

carrier in a market-like exchange; consequently, themarket

safeguard is not effective.To

15

preferentially,

we

expect that the agent to channelizemore

business to the interfaced carrier, ceteris paribus.We

formally hypothesize that:HI:

Asset Specificity willbe

positively related to the degreeof electronicintegration.

Product

Complexity.A

major element

of complexity in the transaction cost context is the level of complexity of theproduct

(Anderson, 1985;Malone

et al. 1987;Masten,

1984)handled

in the transaction.Product

complexity in the propertyand

casualty insurance context is best highlightedby

the differencesbetween

personaland

commercial

lines. In general, personal lines are relatively standardized, partlydue

to regulationand

partlydue

to intrinsic features (such as a relatively limitednumber

of optionson

auto orhomeowners'

insurance).Commercial

lines, in contrast, consist of productsused

by

agents to insure businesses.Such

insurance requires the processing of severalhundreds

ofthousands

of variations of coverage optionsby

tailoring theproduct

offering to the specific requirements of the business, resulting in a highlycomplex

set of productsand

processes.Products of high complexity require

more

informationexchange

between

organizations or units involved incompleting

the transaction.As

Malone

et al(1987) noted, "buyers of products with

complex

descriptions aremore

likely towork

with

a single supplier, in a close, hierarchical relationship..." (p.487). Theoretically,due

to relatively high transaction costs,such

complexityembodied

in thecommercial

lines ismore

efficientlyhandled

within a 'hierarchy-like'mode

under

ceteris paribus conditions. Thus,

our

hypothesis is:H2: Product

complexity willbe

positively related to the degreeof electronic integration.Trust.

One

of themajor underlying

behavioraldimensions

in the transactioncost perspective is

opportunism,

defined as 'self-interest seekingwith

guile' (Williamson, 1975, 1985).Williamson

(1975) contrastsopportunism

with

"stewardship behavior",which

"involves a trust relation" (p.26). Trust canbe

16

viewed

as the obverse ofopportunism

(Jarillo, 1988),and

a relationshipbased

on

ahigher level of trust will

be

less subject to potential opportunistic behavior thanone

with

lower

levels of trust.The

implementation

of thislOS

hasbeen

accompanied by

the granting of underwriting authority to these agents.Agents

differ in their levels ofunderwriting

authority. Indeed,

subsequent

to the installation of the system, the focal carrier has granted or increased underwriting authority tomost

electronically-interfaced agents. This authority implies that agents are able tocomplete

the full circle of quoting, underwritingand

issuing policies without reference toand

approvalfrom

the focalcarrier. In contrast to non-interfaced systems, the

lOS

allows the focal carrier toexploit the functionality of the

system

to maintainan

'audit trail' of the steps carried outby

the agent tounderwrite

a particular insurance policy.While

thisfunctionality provides a

mechanism

for the focal carrier to delegateunderwriting

authority, the

independent

agent hasno

basis to ascertain the degree towhich

itsactions are

monitored

relative to other electronically-integrated agents. Thus, thelevel of

underwriting

serves asan

indication of the trust that exists in thisrelationship

and

further induces the agent to act in a 'hierarchy-like'mode

rather than in a 'market-like' one.We

propose

the following hypothesis:H3: Trust will be positively related to the degree of electronic integration.

Agent

Size as a Control VariableSize has

been

aprominent

variable in industrial organizationeconomics

(Scherer, 1980)

and

has an effecton

vertical integration. Thus, in this researchwe

couldargue

a positive effectbetween

sizeand

electronic integration.However,

withour

focuson

theindependent

insurance agent, it is difficult toargue

that the largeragents will be electronically integrated with a single insurance carrier (Stern

and

El-Ansary, 1977). This is because suchan

integration couldweaken

their ability to serve a variety ofmarket segments

as 'independent' agents.The

role ofasymmetric

firm17

size has not

been addressed

within the theoretical formulation of the transactioncost

framework

(Osborn

and

Baughn,

1990) although, as discussed, researchers (Heideand

John, 1988)have

pointed out that for a smallagency

dealing with a large principal vertical integrationmay

notbe

a viable option to safeguard specific assets. Thus, inour model,

we

specify size as a control variableand

expect, ceteris paribus, that the relatively larger agents are less likely tobe

electronically integrated.Methods

The

hypotheses

are tested in a two-part design usingtwo

independent

samples: (a) 143 property

and

casualty(P&C)

insurance agents involved in the commercial lines business~

who

are interfacedwith

a single focal carrier via adedicated lOS;

and

(b) with arandom

sample

of 64independent

agents interfacedwith

insurance carriers for personal lines business.The

second

setting is tocross-validate

some

of thekey

results of the first setting in acomplementary

approach

toincrease the robustness of the findings. Since the design parameters of

two

parts are not thesame,

we

discuss themethods

and

results for each part separately.Part

One:

Electronic Integration in theCommercial

LinesSegment

This research setting is characterized

by

the following conditions: (a) thedeployment

ofan

lOS

by

a focal carrier to a set ofindependent

agents; (b)improved

information flows, bettermonitoring

and

control capabilities,and

reduced

cost of policy processing enabledby lOS

deployment;

and

(c) asample

of arandom

set of agents electronically-interfacedwith

this focal carrier.Data.

A

structured questionnaire reflecting themeasures

of thekey

constructswas

mailed

to all 321 agents of a focal insurance carrier thathad

deployed

anlOS

as ofJuly, 1988.Complete

datawere

obtainedfrom

143 agents, representing a responserateof

44.5%

~

considerably higher than the20%

in Etgar's (1976) study of theP&C

18

Informant.

A

major

area of controversy in researchon

organizational-levelphenomena

relates to the identification of appropriate 'informant' formeasuring

organizational properties.

With

the objective ofminimizing

key-informant bias (Bagozziand

Phillips, 1982), v^e sought to identifyknowledgeable

informant(s) aswell as assess the

need

and

benefits of multiple informantsduring

the initialround

of interviews.As

most

agencies areowner-managed,

we

chose the ov^mer asour

only informant since

no

otherperson

has thevantage

point for providing the data relevant for this study. Thisapproach

is consistent with the generalrecommendation

to use themost

knowledgeable

informant(Huber

and

Power,

1985;

Venkatraman and

Grant, 1986); as well as the research practice of relyingon

a single senior-levelinformant

in studies involving small organizational units (see for instance. Daftand

Bradshaw,

1980).The

mean

insuranceagency

had

a total personnel size of 26and

annual

commercial

premium

of $5.8 millionsupporting

our

contention of the validity of relianceon

a single, senior-level informant.Measures.

We

briefly describe ourapproaches

to operationalize the constructsin the first part of the study.

Electronic Integration.

As

mentioned

earlier, thedegree

of electronic integration is operationalized as 'the percentage ofcommercial

line business, indollar

premium

terms,accounted

forby

the focal carrier.'Asset Specificity. Consistent

with

our

theory,we

focus (in this part of the study)on

human

asset specificity.The

complexityand

theunique

featuresembedded

in thelOS

requires either dedicated personnel for dealingwith

the carrieror specialized training of operators. Further, effective exploitation of the IT

capabilities requires higher levels of participation for

planning

and

implementing

the

new, unique

set of procedures. Thus,we

measured

human

asset specificityby

summing

threedichotomous

questionnaire items: (a) the presence of a dedicated19

operators in

system planning

and

implementation. Thus, the value for themeasure

rangesfrom

to 3.Complexity. This construct could

be

measured

inmany

differentways

including a

measure

capturing the perceived complexity of theproduct

by

the agent.Given

our

focuson

an

organizational-level construct ofproduct

complexity,we

decided

tomeasure

this as 'the percentage ofcommercial

line business' within the agent's portfolio as this is agood

surrogate for the level of complexity.Within

the industry,we

found widespread

acknowledgement

thatcommercial

lines aremuch

more

complex

than personal lines.Trust.

The

level of trust is operationalized as the extent ofunderwriting

authority given to the agent. Since this function is

perhaps

themost

critical aspect of the insurance process~

hithertounder

the control of the carrier~

the extent of underwriting authority delegated isan

appropriatemeasure

for the trust placedby

the carrier

with

the agent.Four

levels of underwriting authorityfrom

the questionnaire serve as the measure.^Size. Size

was

operationalized asan

8-level categorizationbased on

totalpremiums.

^0Analysis.

The

basic equation for the test of hypotheses is as follows:EI =

ao

+ a] Trust + aj Asset Specificity+a3 Complexity

-a4 Size+

e (1)where, EI=degree

of electronic integrationand

the other concepts are as discussed above. Since thedependent

variable isbounded

between

and

1, a standard set ofOLS

estimators is biased (Judgeet al., 1980). Consistent withCaves

and

Bradburd

(1988)

and Masten

et al (1989), thedependent

variablewas

transformed into the form: /n[EI/(l-EI)] for estimation purposes.^Theexact measure wasa four-level categorization of thedollar amountoftheunderwriting

authority limit granted to the specific agent by the focal carrier: None, Less Than $500,000, $500,000-$1,500, 000, and Greater Than $1,500,000.

20

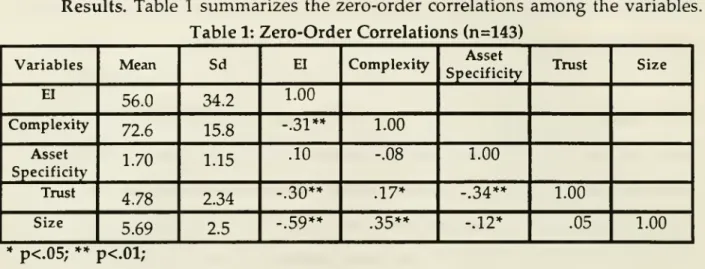

Results. Table 1

summarizes

the zero-order correlationsamong

the variables.Table

1:Zero-Order

Correlations(n=143)21

1989)

which

has generally yielded statistically significant relationships in thehypothesized

direction.The

coefficient for trust was, contrary to the hypothesis, negativeand

significant,implying

an

inverse relationshipbetween

trustand

electronicintegration. This

seemingly

contradictory finding canbe

partly explained ifwe

recognize that underwriting authority is highly coveted

by

agents (due to the controland

authority over the entire business process of writingand

issuing the insurancepolicy),

and

the focal carrier couldbe

employing

the grant of underwriting authorityas another

mechanism

of 'quasi-integration'.Thus

one

couldargue

that agents thatalready

have

a high share of businesswith

the carrier (i.e., high levels of electronicintegration) are less likely to be

provided with

this incentive. Alternatively (aswe

elaborate later) it couldbe

that themonitoring

functionalitiesembedded

within thelOS

enable the focal carrier to entrust underwriting authority toeven

the lesselectronically-integrated agents. In the discussion below,

we

suggest that the latter explanation ismore

compelling.However,

in the absence of intertemporal dataon

changes

in electronic integrationand

trust,we

cannot discriminateamong

such

competing

explanations except in a speculativemanner.

Limitations

and

theNeed

for Cross-Validation.The

generalizability of these empirical results, especially the absence of effects of transaction costs determinants islimited

by

the useof a single datasetand

first-cut operationalizations of theconstructs.

The

robustness of results could be increased if at least parts of themodel

are replicated in acomplementary

setting.To

achieve this objective,we

discussbelow

tests carried out in asecond

setting using arandom

sample

of64independent

agents electronically-interfaced with carriers for personal lines business. Part

Two:

Electronic Integration in thePersonal LinesSegment

This research setting is characterized

by

the following conditions: (a) thedeployment

of electronic interfacing systemsby

several carriers toindependent

22

agents; (b)

improved

information flowsand

reduced

costs of policy processing enabledby

interfacing ;and

(c) asample

composed

of arandom

setof 64electronically-interfaced agents that

provided

the required data for this research.^^For each agent

we

consider the degree of electronic integrationwith

themajor

carrier with

whom

the agent is interfaced via a proprietary lOS.Measures.

We

briefly describeour approaches

to operationalize the constructsfor this part of the study.

Electronic Integration. Consistent

with

the first part of this study, the degree of electronic integration is operationalized as 'the percentage of personal linebusiness, in dollar

premium

terms,accounted

forby

the focal carrier.'Asset Specificity.

The measurement

of asset specificity isan

improvement

inthis part of the

study

sincewe

could differentiateamong

three importantdimensions

of asset specificity: (a) technological asset specificity; (b) procedural assetspecificity;

and

(c)human

asset specificity.Each dimension

ismeasured

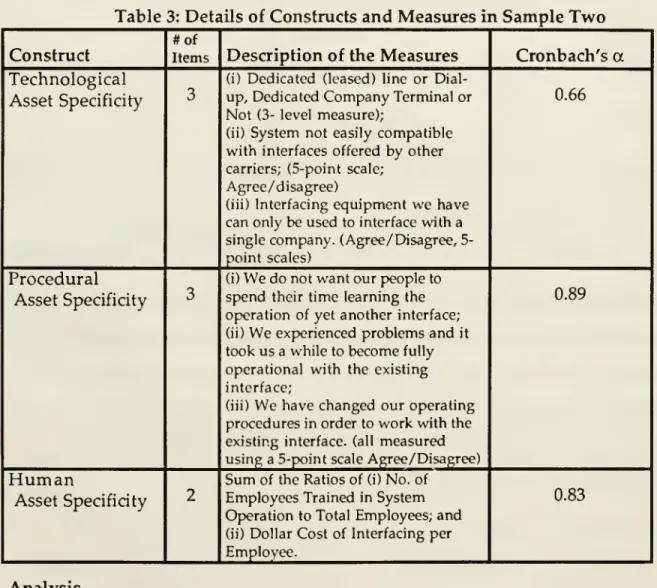

using multi-item interval scales. Table 3summarizes

themeasures

and

indicates theCronbach

a

reliability indices.

The

values ofa

rangefrom

0.66 to 0.89, wellbeyond

the generally-accepted threshold for research. Further as canbe

seen in Table 4, the correlationsamong

them

are low,implying

discriminant validity.The

highest correlation is .69between

proceduraland

technological asset specificity,which

is tobe

expected given the role of the technological platform in customizing theprocedures

to therequirements of the focal carrier.

A

formal test of discriminant validity using thestructural equation

modelling approach

(see for instance,Venkatraman,

1989)^^

We

thank theresearchers concerned for theirgenerousgestureinprovidingdata forthispart (inorder topreserveanonymity,we

havenot provided thereferenceat thisstage). Fromadatasctof747agentsof

whom

312wereelectronically integrated,we

selected arandom sampleof64

who

provided thedata necessarytocarryout the analyses. Based on descriptivedata onthe positions ofthe 'informants'

we

ascertained that 85% ofthis dataisbased on responses providedbytheowner/president. Further,the largerstudywasconductedundertheauspices ofa leading industryassociation,whose memh>ersstand togain directlyfrom theresearchresults,

23

involves establishing that that the three

dimensions

are pairwise correlated at values less than 1.0. Tests usingLISREL

VI

(Joreskog&

Sorbom,

1984) indicated thatthe three dinnensions are

indeed

different (Xd^ (df:3)=

44.42, p<.01).More

specifically, a test that thedimensions

of proceduraland

technological asset specificity are different yielded the following statistics: Xd^ (df:l)=

3.34, p<.07,providing

modest

support

for discriminant validity.Table

3: Details ofConstructsand Measures

inSample

Two

24

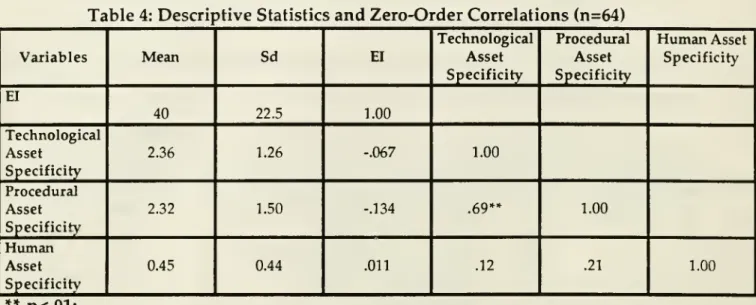

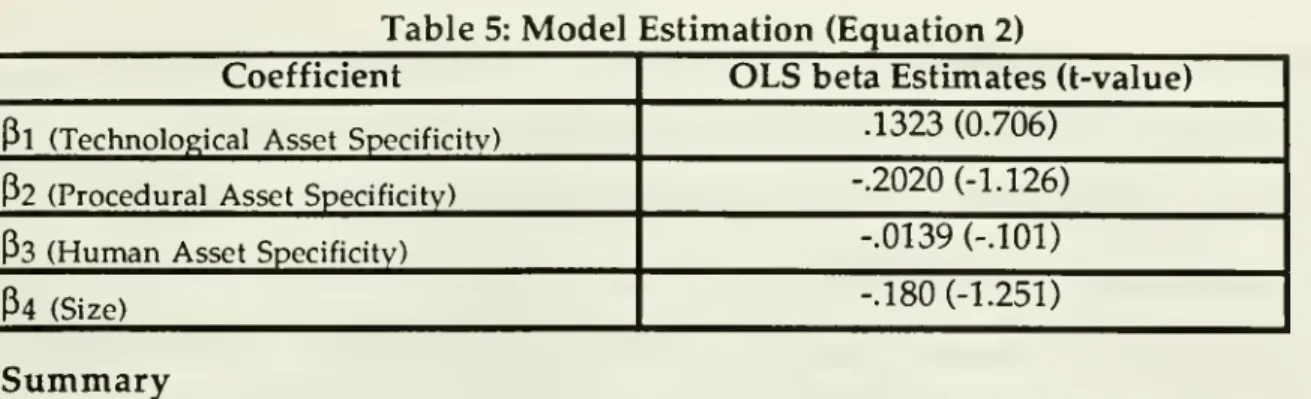

Results

Table 4

summarizes

the zero-order correlationsamong

the variablesused

inpart two:

25

26

the

hypotheses

and

we

offerbelow

some

possible explanations with aview

toguiding

future researchon

the importanttheme

of electronic integration.Possible Explanations

Due

to the Distinctive Features of Electronic IntegrationOne

obvious

explanation for the results could lie in the distinctionbetween

the general concept of vertical integrationand

the particular concept of electronicintegration. Thus, while prior studies

have

consistentlydemonstrated

positive effects of transaction cost determinants (such as complexityand

asset specificity)on

the levels of vertical integration, it is possible that in the context of electronic integration, the I.T. capabilities inherent in thelOS

act to mitigate the traditionaldeterminants of transaction cost. In other

words,

the superior information processingand

monitoring

capabilitiesembedded

in the carrier-specificinter-organizational

system

hasenhanced

quasi-integrated, vertical, hierarchicalrelationships

without

increasing thedegree

of vertical integration.While

we

would

expect

such

a result in a settingwith

acommon

platform for information-exchange,it is particularly surprising in the settings characterized

by

proprietarysystems

inboth samples. Indeed, the results call for a greater attention to the functionalities of

the

lOS

beyond

a simple'common

versus unique' categorization indeveloping

theoretical

hypotheses

pertaining to the roleand

effects of lOS.We

speculate that it is the functionalities of thesystem

in these specificsettings that act to

moderate

the determinants of transaction cost. Information impactedness, a traditional determinant of transaction costs couldbe

mitigatedthrough

better information access,and

quickerand

'seamless'communication

between

insurance carrierand

the electronically-integrated agents. In this line of reasoning, risk evaluation capability-

enhanced

significantlythrough

expertsystem

functionality

~

could mitigate the transaction costs arisingdue

toproduct

27

compared

to products oflower

complexitydue

to theminimization

ofmarket

'frictions.'

However,

it appears counter-intuitive to suggest that asset specificity isreduced

as well, given the high levels of procedural specificityand

human

asset specificity (training) that is impliedwith

the the installationand

operation ofcarrier-specific lOS.

On

the other hand, it is conceivable that the level of carrier-specific training required for usingan

lOS

may

be

both low and relatively standardacross governance

modes

such

that itmay

have

insignificant differential effectson

the level of electronic integration. It is also possible that the functionalities of expertsystems

built into thelOS

could reducehuman

asset specificity at the level of the agency, resulting inminimal impact

on

the level of electronic integration. Itmay

be

a situation of training

an

operator within theagency

~

who

has neverworked

witha

computer-based system

—

tobecome

conversant with the policy-processing system;once

familiar with the system, the operatormay

find it relatively easy tomove

across

such

systems. If such a step function isindeed

the case, it is important forfuture research studies to

develop

richermeasures

of asset specificity as well asdecompose

it intocomponents

that are related to the general technology platformand

are specific to a carrier.Lower

requirements of asset specificitymay

not convert the transacting situation into a smallnumbers

bargaining one,making

it relativelymore

attractive toconduct

transactions in 'market-like'modes

of governance.Opportunism

may

alsobe

attenuatedby

the 'mutual hostage' situation(Williamson, 1985) in

which

the carrier too hasmade

transaction-specificinvestments in the

form

of: (a) training the agent to operate thesystem

as well asproviding considerable technical support in the early stages of interfacing;

and

(b) non-redeployable expenses (i.e.sunk

costs) associated with the installation of thehardware and

thecommunications

architecture at the locations of each agent. Thus, the carrier has reciprocally invested in transaction-specific assetswith

the agent,and

28

this reciprocity

may

serve toreduce

transaction costs. This situation of co-specializedassets, ones that are

most

valuable vs^henused

together (Klein,Crawford

and

Alchian, 1978)may

require a specification of the degree of co-specialization in a particular transaction relationship rather thanan

evaluation of the asset specificityof

any

one

of the parties in isolation.Alternatively, the agent

may

have

employed

othermeans

of safeguarding transaction specific assets than increasing the degree of electronic integration.Such

means

of safeguarding transaction-specific assets for the agent could include'dependence-balancing' actions

such

asimproving

relationshipswith

clients(Heide

and

John, 1988).An

interesting direction for future research is to investigate theforms

of safeguarding transaction-specific assetsand

their effectiveness in the context of electronic integration. Thus, amajor

research challenge is togo

beyond

the current level of speculation ofeconomic

reorganization via information technology toexamine

at a finer level of detail the theoretical relationships ininterorganizational

governance

mediated

by

interorganizational information systems.Normative

Theory

versusCurrent

PracticeIt is also important to recognize that the theoretical

underpinnings

oftransaction cost analysis are normative, while empirical tests (such as this study) are

based

on

current practice.To

the extent that the inefficientmodes

ofgovernance

have

notbeen

eliminatedand

themode

ofgovernance

is not in equilibrium across the entire setting, themodel

estimationmay

notconform

to thenormative

theory. Disequilibrium is a possibility in the insurance industrywhich

has recentlybeen

undergoing major

transformations including: (a)widespread

'downsizing'and

restructuring (including the elimination of regional offices) within insurance carriers;and

(b) significant reductionand

consolidationamong

thecommunity

of insurance agents.Such

dynamic

conditions in the industryand

in itsgovernance

29

Structures suggest a possibility of disequilibrium at the time data

were

collected forthis research. Further,

we

are witnessing a reassessmenton

the part of several insurance carriers of the value of proprietarylOS

versuscommon

industryplatforms.12 This could

be

due

to the ineffectiveness of theselOS

to shift transactionsaway

from

the traditional 'market-like'modes

in the insurance industry. Thus, given the relative recency of leveraginglOS

to reorganizeeconomic

activity,coupled with

the turbulent conditions in the industry, empirical datamay

notsupport

the strongnormative

efficiencyarguments

underlying the transaction costmodel.

'Theory-Constrained' versus

'Theory-informed'

Models

This

study

developed

amodel

of electronic integration thatwas

largely rootedin

one

dominant

theoretical perspective.While

it is useful to test the applicability of the best available theory to anew

phenomenon

(namely, electronic integrationbetween

firms),an

alternative is todevelop

a researchmodel

that isbased

in a larger theoretical base than a single theory.Other promising approaches

includeorganizational theoretic perspectives, such as resource

dependency

(Pfefferand

Salancik, 1978), industrial organization economics, especially those dealing with entry

and

mobility barriers as well asgame

theory.Such an approach

would

result in aphenomenon

being explainedand

/or predictedby

a set of determinantsfrom

multiplecomplementary

theoretical perspectives.Such

'theoretical pluralism'may

be

particularly apposite since while the transaction costmodel

has received strong empiricalsupport

for the 'pure'governance

forms, it hasbeen

shov^m tobe

limited(Milgrom

and

Roberts, 1988; Klein, Frazier,and

Roth, 1990; Robins, 1987) especiallyin terms of its ability to explain intermediate

modes

of governance. Further, the ideathat the effect of the determinants of transaction costs in non-hierarchical relations

30

can

be

mitigatedunder

certain conditions has recentlybeen

gaining conceptualand

empirical currency.Jarillo (1988) noted that the

network form

ofgovernance

between

firmswas

analogous

to Ouchi's (1980) concept ofdans

in a hierarchy. In bothmodes,

opportunism

istempered,

the time horizon is lengthenedand

transaction costslowered.

While

clans mitigate conditions of high uncertaintythrough

a strong organizational culture, Jarillo suggests that trust relations canbe

purposefully forgedbetween

firmsengaged

in long-term relationships in anetwork

governance

form

(see Sabel,Kern

and

Herrigel, 1989; Powell, 1990).Game

theoretic concepts alsosupport the notion of cooperative behavior in the case of repeated

games

(Krepsand

Wilson, 1984); recurrentexchange

is similar toan

infinite horizongame.

Reputation effects also

moderate

the incentive tobehave

opportunistically. Thus, givenfundamental

shifts in the organization ofeconomic

activity (Pioreand

Sabel,1984; Sabel et al., 1989; Powell, 1990) it is

myopic

to be limited toany

singletheoretical approach.

We

call for a greater attention to thedevelopment

ofmodels

ofphenomena

that are 'informed' but not necessarily 'constrained'by any

singletheoretical perspective.

Research

Design

ExtensionsWhile

theabove

issues focusedon

theoretical considerations, future research should addresssome

of thecomplementary

research design extensions.Two

are particularly important:One: Use of a Control Group.

Our

design falls within the category of 'posttestonly'

(Campbell

and

Stanley, 1963)which

is limited in its ability to rule out severalcompeting

explanations.Follow-on

research isunderway

that explicitly incorporates a 'control group' of agents thatdo

nothave

the functionalities offeredby lOS

31

the functionalities of

lOS

to specifically test the determinants of electronicintegration.

Two: Pre- versus Post- interfacing. Since the

deployment

oflOS

is relativelynew

inmany

markets, apowerful

designwould

be toadopt

a pre- versus post-design to assess thechange

in the level of electronic integration as well as itsdeterminants

and

effects. This could help, for example, tounderstand

the negative relationshipbetween

trustand

electronic integrationobserved

in the first part of this study.Other

key

research questions that canbe

addressed withinsuch

a design include: (a) a clearer delineation of of the forces underlying the shiftfrom

one

governance

mechanism

to another;and

(b) a precise calibration of the changes in asset specificity as well as other determinants ofgovernance

mechanism

as a direct result of thedeployment

of lOS.Conclusions

This

paper

developed

a set ofhypotheses

on

the determinantsand

effects of electronic integration thatwere

rooted in the transaction costframework and were

tested in

two

differentsamples

ofindependent

insurance agents in the propertyand

casualty segment.

The

results provideno

support for the transaction costdeterminants, raising the possibility that the availability of sophisticated

information processing capabilities could mitigate the transaction cost effects.

Some

explanations for the counter-intuitive results arenoted

in thehope

of motivating further research into the important area of identifying determinants of electronic integration.32

References

Alchian, A.A.

and

H.Demsetz.

(1972) "Production, information costs,and

economic

organization".

American

Economic

Review, 62(5):777-795.Anderson,

E. (1985). "The salesperson as outside agent oremployee:

a transaction cost analysis." Marketing Science, 4:234-253.Anderson,

E.and

D.C. Schmitlein. (1984). "Integration of the sales force:An

empirical examination".

Rand

Journal of Economics, 15:3-19.Bagozzi, R.P.

and

L.W.

Phillips (1982). "Representingand

testing organizationaltheories:

A

holistic construal". Administrative Science Quarterly, 27:459-489. Bakos,Y

J. (1987) "Interorganizational information systems: Strategicimplications for competition

and

coordination."Unpublished

Doctoral Dissertation,MIT.

Bakos, J.Y.

and

M.E. Treacy (1986). "InformationTechnology

and

Corporate

Strategy:

A

Research Perspective."MIS

Quarterly,June

pp

107-119.Barrett, S.,

and

B.Konsynski

(1982). "Inter-organization information sharing systems".MIS

Quarterly, Special Issue, 1982.Blois, K.J. (1972) "Vertical quasi-integration" Journal of Industrial Economics,

20,253-272.

Cash, J.I.

and

B. Konsynski, (1985), "ISredraws

competitive boundaries,"Harvard

Business Review, 63 (2), 134-142.Caves, R.E.

and

R.M.

Bradburd

(1988)."The

EmpiricalDeterminants

ofVertical Integration," Journal of

Economic

Behaviorand

Organization, 9:265-279.demons,

E. K.and M.

Row

(1988), "InformationTechnology

and

Economic

Reorganization." Proceedings of the 10th InternationalConference on Information Systems. Boston,

Mass:

December

1989.demons,

E. K.and

S.O.Kimbrough

(1986)."Information Systems,Telecommunications,

and

their Effectson

Industrial Organization," Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on InformationSystems, pp. 99-108.