Fluvial Migrations: The Ethics of

Comparison in Péter Forgács’s The Danube

Exodus

László Munteán

Abstract

The Danube Exodus is a 1998 film created by Hungarian film and video artist Péter Forgács. The film consists almost entirely of amateur footage made by Hungarian Captain Nándor Andrásovits on two of his consecutive voyages on the Danube. On the first voyage, in the summer of 1939, his ship carried a group of Slovakian Jewish refugees from Bratislava to the Black Sea, from where they would continue their journey to Palestine. The next year, sailing upstream, he was tasked with taking a group of Bessarabian Germans uprooted from their homeland in the Danube Delta and relocated to Nazi-occupied Poland. Forgács’s film sets the Jewish and the German exoduses in a comparative relation to each other, challenging lingering taboos on discussing German suffering in relation to the Holocaust. This article examines the editing techniques that Forgács employs to renegotiate the distinction between victims and perpetrators through the lens of memory’s relation to identity. The article demonstrates that the ethical stance Forgács embodies in The Danube Exodus resonates with the ethics of multidirectional memory in Michael Rothberg’s sense (2009).

Keywords: Holocaust, Bessarabian Germans, Danube, Péter Forgács, found footage, multidirectional memory

Résumé

The Danube Exodus est un film réalisé par le cinéaste et vidéaste Péter Forgács en 1998. Il est fait presque entièrement d’images filmées par l’amateur hongrois le Capitaine Nándor Andrásovits pendant ses deux voyages consécutifs sur le Danube. Lors du premier voyage, à l’été 1939, son bateau transportait un groupe de réfugiés juifs slovènes de Bratislava à la Mer Noire, d’où ils devaient se rendre en Palestine. L’année d’après, son navire remontait le fleuve avec à son bord un groupe d’Allemands de Bessarabie déplacés de leur terre natale dans le Delta du Danube vers la Pologne occupée par les Nazis. Le film de Forgács place les deux exodes, le juif et l’allemand, dans une relation de comparaison, en s’emparant de la question longtemps taboue de la souffrance allemande au regard de l’Holocasuste. Cet article analyse les techniques de montage employées par Forgács pour repenser la distinction entre les victimes et les coupables sous l’angle de la relation de la mémoire à l’identité. Il montre que la position morale que Forgács incarne dans The Danube Exodus fait écho à l’éthique de la mémoire multidirectionnelle de Michael Rothberg (2009).

Mots clés: Holocauste, Allemands de Bessarabie, Danube, Péter Forgács, images d’archives, mémoire multidirectionnelle

Péter Forgács is a Hungarian film and video artist known for his interest in home movies from the 1920s to the 1960s, which provide the raw material for his films. Founder of the Budapest-based Private Photo and Film Archives Foundation (PPFA), a vast collection of photographs and amateur films from the twentieth century, he is interested in the ways in which mundane details of everyday life recorded by amateurs provide alternative perspectives on history. In the footage that he works with there are no battles, famous politicians, or horrendous atrocities. Quite the contrary, one finds in them recurring scenes and poses recorded during holidays, excursions, family get-togethers, and celebrations. The temporality of these events, as Ernst van Alphen notes, feels as though severed from the progression of historical time (2011, 97-103). Their unsettling poignancy stems from our retrospective awareness of the horrors of history that often enveloped these happy moments, and from our knowledge of the past that, for those in the films, is still an unknown future.

Figure 1: The Queen Elizabeth at Budapest in 1939 (Fortepan/Gali)

Like the rest of the films in Forgács’s oeuvre, The Danube Exodus (1998) takes viewers into the micro-level of history but, in contrast to the predominantly familial settings of his other films, it takes us aboard a Hungarian Danube cruise ship, the Erzsébet Királyné (Queen Elizabeth) (Figure 1). The one-hour film is a meticulously compiled montage of footage recorded by the ship’s captain and amateur filmmaker Nándor Andrásovits on two of his voyages. Forgács’s film almost entirely consists of this footage. The first voyage took place in the summer of 1939 with a group of Orthodox Jews on board, who were fleeing from Bratislava to the Black Sea, hoping to escape to Palestine. Aron Grünhut, head of the Bratislava Orthodox Jewish Community, hired two ships, the Queen Elizabeth and the Yugoslav Tsar Dusan, to carry out the illegal migration of 1365 Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, and Austrian Jews to safety. A year later, in 1940, the Queen

Elizabeth was part of a fleet of twenty-seven ships hired by the Third Reich to ferry Bessarabian Germans1

upstream to Germany. Having lived in the Danube Delta region since the mid-1800s, these Germans were forced to yield their lands to the Soviet Union under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 and resettled on German-occupied Polish territories.

______________________________________

1 Bessarabia is a former Russian governorate at the Black Sea, which lies in modern-day Moldova and Ukraine. Upon the invitation

After the war, the Communist regime in Hungary demoted all captains and, while remaining in the vicinity of the Danube, Andrásovits worked menial jobs until his death in 1958. Forgács received the original 8-milimeter footage of the German exodus from the captain’s widow, who kept it hidden during the decades of Communism. The footage of the Jewish exodus was given to him by the historian János Varga, who had received it from one of Andrásovits’s fellow captains. The original films were screened only on a few occasions, presumably for a small circle of friends (Forgács 2006, 12).

Forgács was fully aware that, by combining the two exoduses into one film, he would run the risk of offending those to whom the comparison of Jewish and German suffering was unacceptable. The film was nonetheless received with enthusiasm, earning the award of the Budapest Hungarian Film Week in 1999 as well as the award for best documentary at the Kraków Film Festival in the same year. One reason for the film’s success lies in Forgács’s editing techniques that he employs to renegotiate the distinction between victims and perpetrators through the lens of memory’s relation to identity. Through a close reading of key scenes, and with the help of Jacques Rancière’s theory of the sentence-image, this article lays bare this potential of editing and demonstrates how The Danube Exodus resonates with the ethics of “multidirectional memory,” as elaborated by Michael Rothberg (2009).

Whirlpools of association

Research constitutes the backbone of Forgács’s artistic work. He goes to great lengths to learn as much as possible about the lives of the characters in the amateur films he works with. Preparing for The Danube Exodus, he traveled as far as Israel and the United States to interview those from Andrásovits’s footage who were still alive or to track down and talk to their descendants.2 Several diary entries and letters written by the passengers that Forgács collected throughout his research found their way into the captions and the voiceover. In order to contextualize these private accounts within larger historical events, Forgács supplemented the captain’s amateur footage with contemporary archival materials and hand-drawn maps, informing viewers of such landmark events as the Anschluss, the German occupation of Prague, and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

In Forgács’s hands, these auxiliary materials serve a dual purpose. At one level, they provide a chronological sequence, which is further enhanced by recurring images of water metaphorizing the passage of time. The nondiegetic hum of the ship’s machines, the sound of sloshing water, the monotonous pitch of the voiceover, and the melancholic tone of Tibor Szemző’s minimalist musical score all work toward the same effect. This sense of linear progression, however, is often unsettled by the same auxiliary materials that one would expect to sustain it. Captions and voiceovers, for instance, are often out of sync with the footage and, as Zsófia Bán contends, “[i]nstead of enhancing understanding, images of different texts used in the film often serve to destabilize or complicate it. … These texts become free-floating signifiers enhancing the affect of history” (Bán 2012).

One also senses a dissonance between the intimate and often happy moments of life on board, especially during the Jewish exodus, and the escalation of a global conflict signaled by the captions. Similarly

2 For the interviews, photographs, and additional information Forgács acquired throughout his research, visit the film’s website at http://www.danube-exodus.hu.

disorientating is the contrast between the joyful hope on the faces of the Jewish refugees sailing towards safety and the grim sadness on the faces of Bessarabian German farmers uprooted from their lands. These contrasts are further enhanced by the juxtaposition of filmic and photographic temporality through freeze-frames that disrupt the progression of the film and invite viewers to ponder the faces of the ones who return the gaze of Andrásovits’s camera. Such disruptions of the linear flow of the narrative occur throughout the film. But rather than simply dramatizing the fragmentary nature of the visual material at hand and our limited access to the past, these ruptures pry open a space for viewers to engage with the film beyond narrative.

Jacques Rancière’s (2009) notion of the sentence-image helps conceptualize the dynamics and the effect of these ruptures. Rancière situates the sentence-image in between two regimes of the image: the representative and the aesthetic. In the former, what is visible is put to the service of what is sayable, that is, of an overarching plot or narrative. The latter paradigm subverts this hierarchy by subjecting the sayable to the visible. He relates this turn to the rise of the nineteenth-century realist novel, in which the abundance of descriptions of non-signifying details allows what is visible to disrupt what is sayable. In what Rancière calls the sentence-image, speech “exhibits its particular opacity, the under-determined character of its power to ‘make visible’. … At the same time, however, speech is invaded by a specific property of the visible: its passivity” (121). Forming a transition between the representative and the aesthetic regimes, the sentence-image is

the combination of two functions that are to be defined aesthetically—that is, by the way in which they undo the representative relationship between text and image. The text’s part in the representative schema was the conceptual linking of actions, while the image’s was the supplement of presence that imparted flesh and substance to it. The sentence-image overturns this logic. The sentence-function is still that of linking. But the sentence now links in as much as it is what gives flesh. And this flesh or substance is, paradoxically, that of the great passivity of things without any rationale. (46)

This “great passivity of things without any rationale” opens up space for the image-function to take the upper hand. This productive space of passivity, which exerts its effect by suspending the logic of the representative schema, manifests itself in The Danube Exodus in the form of a forcefield building up around texts and images unmoored from their sentence-function.

Such forcefields can provide points of entry for Forgács’s viewers to actively engage with his work. The “open piece,” he says in an interview, “gives far more surface for the imagination than does the linear narrative. This accounts for the associative jumps in my work, the shifts from the personal to the public, back and forth, and for the frequent lack of imagery. … These discontinuities offer the viewer an opportunity to reconstruct a narrative from the ruins of a filmic memory” (qtd. in MacDonald 2011, 17, italics in the original). Although the word “reconstruction” suggests that viewers are invited to fill in the blanks left unsaid by the fragments of found footage, the way in which Forgács exhibits these “ruins” opens up associative spaces beyond the realm of the sayable. To use a water metaphor, these spaces open up like the funnel of air in the center of a whirlpool on a river, breaking its unidirectional flow with a vertical spin induced by two oppositional currents. This vertically swirling and widening gyre becomes the crucible of a new image, which belongs to the aesthetic schema.

Certain scenes in The Danube Exodus are particularly illustrative of the mnemonic dimensions that such whirlpools pry open. In one of these scenes, toward the very end of the film, we are taken to the end of the war and offered a glimpse of the icy waters of the Danube from the deck of the Queen Elizabeth as it plows

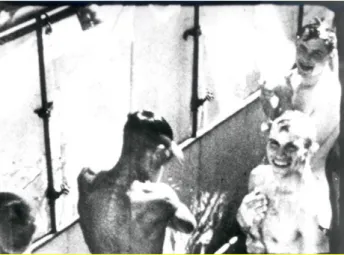

the waves in the winter of 1945. This scene gradually gives way to an unidentified streetscape with passersby, one of whom appears to be an Orthodox Jewish man carrying a goose under his arm. As the shot freezes into a still image, the caption appears: “By 1945 the majority of European Jews had been exterminated… only 76,000 Jews could escape along the Danube.” The interplay of these visual and textual elements creates a whirlpool formed by the icy waters of the river on the one hand and by the information conveyed by the caption on the other. As Forgács reveals in an interview, “the subtitles are all part of the complex palette that grabs your guts, and maybe the second time you discover another, until then invisible layer” (qtd. in Nichols 2011, 54, italics in the original). For viewers familiar with the atrocities committed by the Hungarian Arrow Cross in the winter of 1944-45, the interplay of text and image evokes those Jews who had been shot into the Danube in Budapest in the last months of the war. The “passivity” of the icy water, in Rancière’s sense, disturbs the flow of the narrative, enabling the passivity of the visible to fold back on the sayable and trigger an association to events often left unsaid in Hungarian history. Similar dynamics are at work in two consecutive scenes that feature passengers on both journeys taking a shower on board. The special significance of these scenes lies in their potential to establish links between the two groups of refugees and to provide new terms for their comparison. The first “shower scene” appears during the first journey, as the ship sails on waters that separate Romania from Bulgaria. We learn from a passenger’s diary entry that they were expecting to arrive at the Bulgarian port of Russé, where they would continue their journey by train to the Black Sea port of Varna. Almost simultaneously, the voiceover informs us of British authorities reducing the number of Jewish immigrants allowed entry to the British Mandate of Palestine in fear of an Arab revolt that would jeopardize British presence in the region. With the escalation of Nazi brutalities, the voiceover continues, the international waters of the Danube proved to be the most feasible passage of escape. Once the ship passes the Romanian town of Turnu-Severin, viewers see women taking a shower on the deck, wearing swimsuits and smiling (certainly also out of embarrassment) into Andrásovits’s camera, unaware of the hardships they are about to face in the following days (Figure 2). The shot is taken from a high angle, possibly from the captain’s bridge, offering a clear view of the showerheads and the women underneath. In what Rancière calls the representative regime, this scene would be nothing more than a visual illustration of life on board, textually embedded into a larger historical context. As a sentence-image in the aesthetic regime, however, text and image are released from their representational functions, allowing the distinct images of this scene to exert their signifying functions over a wider conceptual and mnemonic terrain. In this relation, the distant news of Nazi brutalities infiltrates the shower-scene, allowing the showerheads to morph into a synecdoche of gas chambers. This exchange between text and image delineates an associative forcefield, which ruptures narrative continuity by invoking the fate that would await millions of Jews over the years to come.

Figure 2: Péter Forgács, The Danube Exodus, 1998 (with kind permission of the director, thanks to Zsófia Bán)

While the shower does not evoke any single event, location, or image, it calls to mind a collectively shared memory of the Holocaust. In his discussion of “indigestible images” of the Holocaust that have been withheld from circulation, Frank van Vree (2010) writes about “grounding images,” where “grounding” refers to “mutual knowledge, beliefs, and assumptions as well as to the way other films, being dependent on this imagery, get their meaning” (279). What the shower-scene evokes is part of the reservoir of this collectively shared knowledge of the Holocaust but, while van Vree focuses on images that have been deemed too problematic for circulation, the shower cannot be pinned down to a particular set of tabooed images. Rather, it has been sustained as a recurring trope of the precarity of life and death in the camps, as dramatized, for instance, in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993). Its grounding power, therefore, derives more from what Alison Landsberg (2004) calls “prosthetic memory”: a mode of recollection fueled by frequent exposure to cinematic and musealized representations of events that have “no direct connection to a person’s lived past and yet are essential to the production and articulation of subjectivity” (20). Forgács’s editing activates this mnemonic reservoir obliquely, as though holding up a ghostly negative of a photograph. By concluding the scene with a freeze-frame—which shows women reaching for their towels, with some of them returning the gaze of the captain’s camera—Forgács pulls us ever deeper into the whirlpool of the sentence-image generated by this associative counter-current. As we are compelled to bear the gaze of the women looking back at the camera, we cannot help but bear witness also to those who died in the gas chambers.3

Rancière’s (2009) discussion of the sentence-image paves the way to his distinction between two types of montage, the dialectical and the symbolic. The former embodies that aspect of the sentence-image, which “couples heterogenous elements” by way of “the distance and the collision which reveals the secret of a world—that is, of the other world, whose writ runs behind its anodyne or glorious appearances” (57). He refers to John Heartfield’s photomontage of Hitler with his belly full of money and to Krzysztof Wodiczko’s projections of photographs of homeless onto American monuments as examples of the dialectical montage (56). The symbolic montage, which Rancière predominantly traces in the works of Mallarmé and Godard, also juxtaposes incompatible elements but, instead of highlighting differences, it works by analogy, “attesting to a more fundamental relationship of co-belonging, a shared world where heterogeneous elements are caught up in the same essential fabric and are therefore always open to being assembled in accordance with the fraternity of a new metaphor” (57). While the dialectical montage was a key attribute of the work of the Dadaists and the Russian Constructivists, the symbolic montage was more characteristic of Surrealism (Mahony 2016, 4-8). It is this latter form of montage that explains the rupturing effect of the shower scene. Rather than juxtaposing incompatible elements in a dialectical fashion, the showerhead’s defamiliarization in the forcefield generated by the sentence-image plays out in the “essential fabric” of the Holocaust as a common denominator. Indeed, it is not the incompatibility but rather the fundamental affinity between the two currents that is at work here.

3In the summer of 2015, mist sprinklers were installed close to the entrance of the Auschwitz Museum to prevent queuing tourists

from fainting. The indignation of several tourists at what they perceived as a Holocaust gimmick is indicative of the connotative effect of showers in such a context. (See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p031bcm2).

Figure 3: Péter Forgács, The Danube Exodus, 1998 (with kind permission of the director, thanks to Zsófia Bán)

This dynamic is further complicated in the second half of the film, where a similar scene appears but this time with a group of Bessarabian German boys and men taking a shower at the exact same spot where Jewish women had a year before (Figure 3). The shot is taken from a similarly high angle but, instead of concluding in a freeze-frame, the movement of the footage is slowed down at the end, showing one of the boys splashing a handful of water onto his head and others looking back at the captain. Not unlike the uncanny reappearance of the same cities, ports, and natural landmarks encountered during the first voyage, the shower scene partakes in the effect of repetition with a difference, but the iconographic congruence of the two scenes reinforces the conventional identification of Germans as perpetrators and Jews as victims, rendering their comparison ethically problematic. The dynamics of the montage at work here is therefore more akin to the dialectical one in Rancière’s sense. Perceived in terms of the dialectics of perpetrator and victim, the two groups’ journeys are rendered mutually exclusive, with no moral ground for analogy. In other words, the centripetal force of the first whirlpool is replaced by the centrifugal dynamics that push these currents ever more apart.

The same dynamics, however, also has the potential to instantiate new platforms of comparison. In Rancière’s words,

The dialectical way invests chaotic power in the creation of little machineries of the heterogeneous. By fragmenting continuums and distancing terms that call for each other, or, conversely, by assimilating heterogeneous elements and combining incompatible things, it creates clashes. And it makes the clashes thus developed small measuring tools, conducive to revealing a disruptive power of community, which itself establishes another term of measurement. (2009, 56)

In this sense, the clash that cancels out the comparison between the two groups construed as victims and perpetrators instantiates a new term of measurement, which in turn releases the two groups from the bonds of these mutually exclusive categories by positioning them both as refugees in transit, tossed about by forces beyond their control. As László Strausz points out in his analysis of the film, “on the river, the German and the Jewish refugees are in a hauntingly similar position” (2011, 103), and the fact that the caption does not categorize the men as Germans but as “boys from the Bessarabian village, Paris” seems to substantiate this reading.

The Queen Elizabeth plays a key role in forging a physical and metaphorical connection between the two groups of refugees. In his essay “Of Different Spaces,” Michel Foucault describes the ability of heterotopia “to juxtapose in a single real place several emplacements that are incompatible in themselves” (1998, 181). He concludes by designating the ship as the epitome of this spatial concept. The ship, he writes, “is a piece of floating space, a placeless place, that lives by its own devices, that is self-enclosed and, at the same time, delivered over to the boundless expanse of the ocean” (185). Even if the Danube is no ocean and the Queen Elizabeth is no sailing vessel, Andrásovits’s fluvial paddle-wheeler constitutes a heterotopic space, which simultaneously reflects and subverts land-based policies and regulations. Sailing on the Danube positioned between borders, the ship occupies a liminal position between riverbanks, ports, and countries, which is “conducive to the modification and formation of identities,” as Tricia Cusack writes in an oceanic context (2016, 8). Providing nothing but the ship as our fixed point of reference, the film pulls us from land to river, from the stationary to the floating, and from the public into the private. It is in this sense that the ship becomes a platform for a new term of measurement provided by the dialectical montage of the second shower scene.

Comparison without competition

By the time the film was released in 1998, scholarly discourse on the memory of the Holocaust in relation to the events of World War II and other genocides in history had reached a turning point. For decades after the war, the Holocaust was regarded as a unique event, not to be compared to any other genocides in history. This view was challenged during the so-called Historikerstreit, the arduous debate among German historians in the 1980s about how to remember the Nazi past (see: Maier 1993, Rosenbaum 1995, Margalit and Motzkin 1996, Novick 1999). Views that upheld the uniqueness of the Holocaust were widely criticized, primarily for the detrimental effects of removing it from its wider historical context and thereby foreclosing the possibility of learning from it (Stone 2003, 192). At the same time, the formerly tabooed theme of German suffering during the war had also entered public discourse (see, for instance, Grass 2002, Sebald 2003). Yet, while academic discourse over the past three decades has increasingly shifted towards more comparative approaches to the Holocaust, it has left everyday life largely unaffected. In the former Eastern Bloc, for instance, the Soviet Gulag and the Holocaust are still widely viewed as genocides competing for recognition, often galvanized by current party politics (Zombory 2019). Who suffered more? Whose suffering deserves more recognition? Such questions are fueled by an understanding of memory in terms of an either/or relation, which presupposes that more recognition dedicated to one event occurs at the cost of remembering another.

Discussing the polarization of scholarly opinions about the Holocaust’s uniqueness versus its comparability, Dominick LaCapra proposed that “[d]econstructing the opposition is necessary in the attempt to elaborate a different way of posing the problem and even of defining the ‘central’ issue” (1996, 45). LaCapra’s call for a new approach in the mid-1990s resonated over ten years later in Michael Rothberg’s breakthrough notion of multidirectional memory (2009), which has served as a key alternative to the competitive model of memory ever since. Challenging the entrenched conception of collective memory as one based on competition, the notion of multidirectionality emphasizes memory as “subject to ongoing negotiation, cross-referencing, and borrowing; as productive and not privative” (3). Rothberg considers the danger of the discourse centered on the uniqueness of the Holocaust in that “it potentially creates a hierarchy of suffering (which is morally offensive) and removes that suffering from the field of historical agency (which is both morally and intellectually suspect)” (9). In his alternative approach, Rothberg proposes that the model of multidirectional memory “posits

collective memory as partially disengaged from exclusive versions of cultural identity and acknowledges how remembrance both cuts across and binds together diverse spatial, temporal, and cultural sites” (11). One of the major contributions of Rothberg’s approach is that it nuances what had long been perceived as a causal relationship between collective memory and group identity. “Memories are not owned by groups—nor are groups ‘owned’ by memories,” Rothberg writes (5). Consequently, looking at memory as a multidirectional phenomenon reveals how the memory of the Holocaust has served as a vehicle to articulate memories of other atrocities and genocides, such as those related to colonialism, which Rothberg explores in detail in his book. Comparison without competition, he maintains, is not only expedient but also ethically desirable.

The Danube Exodus occupies a peculiar position in relation to this paradigm change from uniqueness to multidirectionality. Created more than a decade before multidirectional memory gained purchase in academia, the film in many ways foreshadows, as well as complicates, the ethical stance Rothberg advocates. For instance, what Forgács describes as the “associative jumps” made possible by the openness of his work resonates closely with what Rothberg calls “imaginative links” (2009, 18) between seemingly incompatible memory cultures. He argues that “a certain bracketing of empirical history and an openness to the possibility of strange political bedfellows are necessary in order for the imaginative links between different histories and social groups to come into view; these imaginative links are the substance of multidirectional memory” (18). In a similar vein, the two stories brought together in The Danube Exodus “mutually reflect and contextualize each other,” as Forgács mentions in an interview (qtd. in Nichols 2011, 54):

Creating, comparing the incomparable duet of the German-Jewish exodus in Danube Exodus was revelatory for me. I found myself contrasting the Bessarabian German refugees’ saga (indeed, many of them were later recruited to the Wehrmacht) with the happy Jews destined for Palestine dancing on the ship. Altogether, it was a constant inner struggle for me. I was learning the acceptance of civil sufferings, even if it was German suffering. (53)

While echoing a multidirectional sensibility, Forgács’s self-reflexive commentary speaks to the difficulty of overcoming the taboo on comparison.

The fact that the two fluvial journeys embody a geopolitical and mnemonic multidirectionality that is essentially different from the kinds Rothberg explores in his work adds to this difficulty. While Rothberg’s case studies explore the galvanizing role of Holocaust memory in facilitating discourses on both earlier and later genocides, The Danube Exodus does not posit the Holocaust as an analogy for another genocide. Instead, the German exodus is historically, geographically, and politically entangled with the Jewish one. The Holocaust is thus not mobilized as a mnemonic model but as a historical frame within which the migration of both the Jewish and the German refugees take place. The kind of comparison that the film invites is between two fluvially interrelated micro-histories framed within, not outside, the master-narrative of World War II. The comparison at stake here is therefore between the political categories of victims and perpetrators. It is in this sense that Forgács’s uneasy acceptance of designating civilian suffering as a common denominator for comparison comes to the fore as a task that cannot be fully justified by the ethics of multidirectionality.

The challenge at hand in undertaking the comparison was to create a platform, within the discursive model of victims versus perpetrators, for a multidirectional exchange between the two stories to unfold. The spatial arrangement of the The Danube Exodus: The Rippling Currents of the River, the 2002 multiscreen immersive installation based on the film, sheds more light on the creation of such a platform. The exhibition

traveled to multiple cities on both sides of the Atlantic.4 The difficulties that the organizers, including Forgács himself, faced while setting up the exhibition are illustrative of the ethical concerns related to the German-Jewish binary. To counteract this dualism, the installation featured three interlinked paths that visitors could follow: a path dedicated to the Jewish story, another to the German story, and a third one to the captain’s story. The inclusion of the last was intended to anticipate potential charges, as Marsha Kinder, one of the exhibition’s curators, recalls:

Forgács had appropriated the captain’s amateur footage for a new narrative that relied on historical hindsight—one that took new ideological risks in comparing the displacements of the Jewish and German refugees as if they were equivalent, a comparison many members of the Jewish community would find difficult to accept. In the captain’s original home movies, this comparison had been justified by his own personal presence in the narrative field and his participation as witness and documentarian for both groups of refugees, for he helped transport both groups into history. This is why Forgács insisted on the captain and the Danube River being the primary protagonists in the installation’s central poetic space, a decision that may have been intuitive or aesthetic but had ideological implications. (2011, 241)

The figure of the captain, therefore, served as a platform of its own between the Jewish and the German migrations, and was designed to relieve Forgács of the ethical weight of the comparison.

“Hiding” behind the gaze of the maker of the original footage is not an unusual method in Forgács’s oeuvre. In relation to another film project, Own Death, Ernst van Alphen refers to this technique as “radical perspectivism,” which entails a “character-bound focalization [that] helps to avoid explanations and comments from a narrator” (2014, 258). In Kinder’s description of the choices made for the exhibition, a similar kind of perspectivism was employed by positioning the captain, rather than Forgács, as the agent of the gaze and maker of the footage. This way the captain’s story provided a buffer zone between the stories of the Jewish and the German refugees, so that any comparison of the two would be transferred onto the agency of the captain as the “bearer of responsibility.”

Similar measures of precaution can be traced in The Danube Exodus. The captain, however, makes only brief appearances (only on a few occasions, when someone else is holding the camera), which did not allow for a separate storyline. We see him first at the beginning, holding binoculars at the helm, then shortly afterwards in the company of guests on board, and finally at the end of the Jewish exodus, when he meets the Yugoslavian captain of the Tsar Dusan and the Russian captain of the Noemijulia, the maritime ship taking the refugees to Palestine. At the beginning of the film, however, several intertitles are used to bring Andrásovits and his filmmaking hobby into the focus of viewers’ attention. The film opens with the captain walking near a smoking volcano, perhaps on one of his earlier trips, with the famous melody from Strauss’s “The Blue Danube Waltz” in the background. The caption reads “Captain Andrásovits,” shortly followed by another one, “a persistent amateur filmmaker.” As we see the captain walking away, another text appears: “two Danube stories filmed by Captain Andrásovits.” As he is shown at the helm lifting his binoculars to his eyes, we read “Nándor Andrásovits, Captain of the Erzsébet Királyné,” followed by “The Danube Exodus.” Insofar as these cinematic gestures introduce the captain, rather than Forgács, as the filmmaker (Forgács’s name does not even appear), they use radical perspectivism as a rhetorical means to deflect attention from Forgács to the captain.

4 Co-organized with the Labyrinth Project, the exhibition premiered at the Getty Center in 2002:

Conclusion

In his typology of documentaries, Bill Nichols (2001) describes Forgács’s work, and The Danube Exodus in particular, as an example of the performative mode. Documentaries that fall into this category highlight the subjective and affective dimensions of our knowledge of the world. Forgács “invites us,” Nichols writes, “as all great documentarians do, to see the world afresh and to rethink our relation to it. Performative documentary restores a sense of magnitude to the local, specific, and embodied. It animates the personal so that it may become our port of entry to the political” (2001, 137). The whirlpools of associations that pull viewers into worlds hidden behind Andrásovits’s footage translate this entry into the political language of solidarity. When asked about his disposition toward the Bessarabian Germans and the Orthodox Jews in his film, Forgács responded:

I am the Danube; I’m the Germans and I’m the Jews. But I’m not the Nazi Germans, just like I’m not the Communist Hungarian butcher who destroys culture at any price or the right-wing Zionist Jews on that ship who were planning to kill Palestinian Arabs because Betar ideology of settlement needed an empty land. And you’re right, I’m also the German farmer who’s travelling the opposite way on the Danube, but I’m also the captain who has this distant and open-minded perception. I’ve internalized it all. (qtd. in Macdonald 2011, 26)

Forgács’s words attest to the effort to reconceptualize identity in transnational, transcultural, and transethnic directions, which his film conveys through the associative jump analyzed in the second part of this article. For us, viewers, the film offers a similar interface to challenge binary categorizations in relation to memory and identity, or victim and perpetrator, and conceive of these notions as entangled and multidirectional instead. Perhaps the most unorthodox dimension of the film is not that it juxtaposes the stories of Jews and Germans, but that it invites what Forgács calls “nonselective forgiveness. For many years revenge justified the idea of hell for all Germans, but it’s clear now: in human-rights questions there aren’t differences of value among nationalities and races of man” (qtd. in Nichols 2011, 54). Via Alain Badiou’s Ethics (2002), Rothberg locates the ethics of multidirectional memory in “creating fidelity” with the multiple details and nuances involved in a particular situation that often contradict one another (22). Looking through this lens, nonselective forgiveness is not about forgiving everything but transcending the idea of collective guilt. It is about creating fidelity with the part, rather than the whole, and attending to the interrelatedness, rather than fetishizing the uniqueness, of events and phenomena. If The Danube Exodus invites us to think along these lines, its lessons are perhaps more timely today than ever.

References

Badiou, Alain. 2002. Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil. New York: Verso.

Bán, Zsófia. 2012. “Forgács’s Film and Installation Dunai Exodus (Danube Exodus).” Comparative Literature

and Culture 14.5. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol14/iss5/11/

Cusack, Tricia, ed. 2016. Framing the Ocean, 1700 to the Present: Envisaging the Sea as Social Space. London: Routledge.

Forgács, Péter and the Labyrinth Project. 2006. A Dunai Exodus: A folyó beszédes áramlatai / The Danube Exodus: The Rippling Currents of the River. Exhibition Catalogue. Budapest: Ludwig Múzeum.

Foucault, Michel. 1998. “Of Different Spaces.” In Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, edited by James Faubion, 175-185, London: Penguin.

Grass, Günter. 2002. Crabwalk. London: Faber and Faber.

Kinder, Marsha. 2011. “Reorchestrating History: Transforming the Danube Exodus into a Database Documentary.” In Cinema’s Alchemist: The Films of Péter Forgács, edited by Bill Nichols and Michael Renov, 235-255, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

LaCapra, Dominck. 1996. Representing the Holocaust: History, Theory, Trauma. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Landsberg, Alison. 2004. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

Macdonald, Scott. 2011. “Péter Forgács: An Interview.” In Cinema’s Alchemist: The Films of Péter Forgács, edited by Bill Nichols and Michael Renov, 3-38, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mahony, Martin. 2016. “Picturing the Future-Conditional: Montage and the Global Geographies of Climate Change.” Geography and Environment 3, no. 2: 1-18.

Maier, Charles. 1993. “A Surfeit of Memory? Reflections on History, Melancholy and Denial.” History and Memory 5.2: 136-52.

Margalit, Avishai and Gabriel Motzkin. 1996. “The Uniqueness of the Holocaust.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 25.1: 65-83.

Nichols, Bill. 2001. Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press.

---. 2011. “The Memory of Loss: Péter Forgács’s Saga of Family Life and Social Hell.” In Cinema’s Alchemist: The Films of Péter Forgács, edited by Bill Nichols and Michael Renov, 39-55, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Novick, Peter. 1999. The Holocaust in American Life. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Company. Rancière, Jacques. 2009. The Future of the Image. London: Verso.

Rosenbaum, Alan S, ed. 1995. Is the Holocaust Unique? Perspectives on Comparative Genocide. Boulder: Westview Press.

Rothberg, Michael. 2009. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Sebald, W.G. 2004. On the Natural History of Destruction. London: Penguin. Stone, Dan. 2003. Constructing the Holocaust. Elstree: Vallentine Mitchell.

Strausz, László. 2011. “On the River: History as a Palimpsestic Narrative in The Danube Exodus.” Film-Philosophy 15.1: 100-117.

Van Alphen, Ernst. 2014. “On the Possibility and Impossibility of Modernist Cinema: Péter Forgács Own Death.” Filosofski Vestnik 35, no. 2: 255-269.

---. 2011. “Towards a New Historiography: The Aesthetics of Temporality.” In Cinema’s Alchemist: The Films of Péter Forgács, edited by Bill Nichols and Michael Renov, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 59-74.

Van Vree, Frank. 2010. “Indigestible Images: On the Ethics and Limits of Representation.” In Performing the Past: Memory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, edited by Karin Tilmans, Frank van Vree and Jay Winter, 257-83, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Zombory, Máté. 2019. Traumatársadalom: az emlékezetpolitika történeti-szociológiai kritikája. Budapest: Kijárat Kiadó.

Film

The Danube Exodus. 1998. Directed by Péter Forgács. Lumen Film.

László Munteán is an assistant professor with a double appointment in Cultural Studies and American Studies at Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands. His scholarly work revolves around the juncture of literature, visual culture, and cultural memory in American and Eastern European contexts.