MITLIBRARIES

3

9080 02618 1377

"^-iiiuiLmuiijIiuliL H!i^mi!n'-ip;-^;.iin.T i(;n!!iw:;!;ifn:!'';jii'' HiiiiiRllHi'.tiSi'li;:-i'.i5ii!'.niH'"n;n'.V'!inawtftrHMi»!i!HB31

:.M415

no.06-29

2006

PpH

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

DEWEy

HB31

.M415

Y] .o(f~

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Econonnics

Working

Paper

Series

THE

ECONOMIC

LIVES

OF

THE

POOR

Abhijit

V.

Banerjee

Esther

Duflo

Working

Paper

06-29

October

31,

2006

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This paper can be

downloaded

without charge from theSocial Science Research

Network

Paper Collection atMASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTEOF

TECHNOLOGY

NOV

9 20Q6The Economic

Livesof

thePoor

AbhijitV. Banerjee

and

EstherDufloOctober

2006

Abstract

This paper uses survey data

from

13 countries todocument

theeconomic

lives ofthe poor (those livingon

less than $2 dollarperday

per capita atpurchasingpower

parity ) or the extremelypoor

(those livingon

less than $1 dollar per day).

We

describe theirpatterns of

consumption

and

income

generation as well as their access to marketsand

publicly providedinfrastructure.

The

paper concludes with a discussionof

some

apparentanomalous

choices. JEL:010,015,016.

Keyword:

Poverty,Development,

Consumption

ChoicesAbhijitV. Banerjee

and

EstherDuflo

areboth Professorsof

Economics and

Directors oftheAbdul

LatifJameel Poverty Action Lab, Massachusetts InstituteofTechnology,

Cambridge,

In

what

turned outto be arhetoricalmaster-move,the1990

World

Development Report

from

theWorld

Bank

definedthe "extremely poor" peopleoftheworld

as thosewho

arecurrentlyliving

on no

more

than $1 perday

per person,measured

atthe 1985 purchasingpower

parity (PPP)exchange

rate.'Even

thoughtherehave

alwaysbeen

poverty lines— indeedone

dollarperday

was

chosen

inpartbecause ofits proximitytothepovertylines usedby

many

poor

countries'—this particularone

hascome

todominate

theconversations aboutpovertyin aparticularly stark

way.

But

how

actuallydoes one liveon

less thanone

dollarperday?

Thisessay isabout theeconomic

lives ofthe extremelypoor: thechoices they face, the constraintsthey grapple with,and

thechallenges they meet.The

availableevidenceon

theeconomic

livesoftheextremelypoor

is incomplete inmany

important ways.However,

anumber

ofrecent datasetsand

abody

ofnew

researchhave

added

a lottowhat

we know

about theirlives,and

takentogether thereis probablyenough

tostartbuilding an

image of

theway

they live theirlives.Our

discussion oftheeconomic

livesof

theextremelypoor

buildson

householdsurveys

conducted

in 13 countries listed inTable 1:Cote

d'lvoire,Guatemala,

India, Indonesia,Mexico,

Nicaragua, Pakistan,Panama, Papua

New

Guinea, Peru, SouthAfrica, Tanzania,and

Timor

Leste.We

mainly

usethe Living StandardMeasurement

Surveys

(LSMS)

conducted

by

the

World

Bank

and

the"Family

Life Surveys"conductedby

theRand

Corporation, all ofwhich

are publiclyavailable. Inaddition,we

also usetwo

surveys thatwe

conductedinIndiawith ourcollaborators.

The

firstwas

carried out in2002

and2003 in 100hamlets ofUdaipurDistrict,Rajasthan (Baneijee, Deaton, Duflo, 2004). Udaipuris one ofthepoorerdistrictsofIndia,

with a largetribal populationandanunusually high level offemaleilliteracy (atthe timeofthe

1991 census, only5 percent of

women

were

literate inrural Udaipur).The

second(Banerjee, Duflo, Glermerster, 2006) surveyed2,000households in"slums" (orinformalneighborhoods) ofHyderabad, the capital ofthestate of

Andhra

Pradesh and oneoftheboom-towns

ofpost-liberalization India.

We

chosethesecountriesand

surveysbecause theyprovidedetailedinformation

on

extremely poor householdsaround

theworld,from

AsiatoAfricato LatinAmerica,

including informationon what

theyconsume,

where

theywork,and

how

theysaveand

borrow.To

flesh out ourmain

themes

fiarther,we

alsodraw

freelyon

the existingresearchliterature.

From

each ofthese surveyswe

identifiedthe extremelypoor

asthose living inhouseholds

where

theconsumption

percapita isless than $1.08 perpersonper day, aswell asthemerely "poor" definedas those

who

live under $2.16 aday

usingthePPP

inyear 1993 asbenchmark.^

The

useof consumption,ratherthanincome, ismotivatedby

thebetterqualityof

the

consumption

data inthese surveys (Deaton,2004). Table 1 providessome

background

infomiation

on

these surveys. It liststhecountries,and

the sourceofthe surveydata. It alsoliststhe

sample

sizes: thenumbers and

theproportions ofthe extremelypoor

and

thepoor in' In

1993, thepovertylinewasupdatedto$1.08perpersonperdayatthe 1993PPPexchangerate (thisistheline

we

usein thispaper).^Forexample,the"All IndiaRural" povertylineusedbytheIndianPlanning Commission was Rs328perperson

permonth,or$32in PPPdollarsin 1999/2000.

each survey.

The

fraction ofindividuals living under$1 dollarperday

in the survey varyfrom

2percent in

Panama

to47

percentinUdaipur,and

the fraction living under $2 perday

variesfrom

6 percentinPanama

to 86 percentinUdaipur. All thenumbers

discussedin this paperare availablein theappendix.There are

many

importantissues with ouridentification ofthe poor. First,purchasingpower

parityexchange

rates,which

are essential tocompute

a "uniform" povertyline,have

been

criticized as inadequate, infrequentlyupdated,and

inapplicableto theconsumption

oftheextremely

poor

(Deaton, 2004, 2006). Prices are typically higherinurbanthan inrural areas,and even

inrural areas, thepoor

may

pay

differentprices than everyoneelse. Also, reporting periods varysignificantlyfrom

survey to surveyand

this, ithasbeen shown,

systematicallyaffects

what

people report.These problems

may

affectuslessbecausewe

arenotfocusedon

countingthe exactnumber

ofpoor. In describingwhat

their lives looklike,misclassifying anumber

of

households should not

change

anythingvery important abouttheaverageswe

observeinthedata,unless the

number

affected areverylarge,and

thoseartificiallymoved

intooroutofpovertyareverydifferentthan theother poor. Itturns out that

most

of our conclusionsdo

notchange

ifwe

lookatthepoor

ratherthanthe extremelypoor,which

isof course reassuring.Nevertheless

one

cannot obviously entirely ruleout thepossibility that ourresultsmay

have

been

verydifferenthad

we

used

a differentpoverty line.We

will alsoassume

thatthepeoplewe

are describing as thepoor

are thelong-termpoor

in the sensethattheirpermanent

income

isactually closeto theirobserved consumption.If, instead, they

were

just transitingthrough poverty,some

ofthe behaviorsthatwe

willobserve (suchas lackofsavings)

would

be lesspuzzling,and

others (likethe lackofassets)would

bemuch

more

so.We

feel thatthisis a reasonableassumption

inmost

ofthe countries, since the fraction ofthe populationbelow

$2.16 aday

isactually sizeable (40percent ofthepopulation or

more

in themedian

countryand

more

than70

percentinquite afew)and

it isunlikelythatthere are quite so

many

transients.'*However,

for this reason, thepoor

inPanama

(where

only6percentofthepopulation ispoor) or South Africa (where 19percent are)may

notbe easily

compared

to thepoor

insome

oftheother countries,where

theyaremuch

more

numerous.

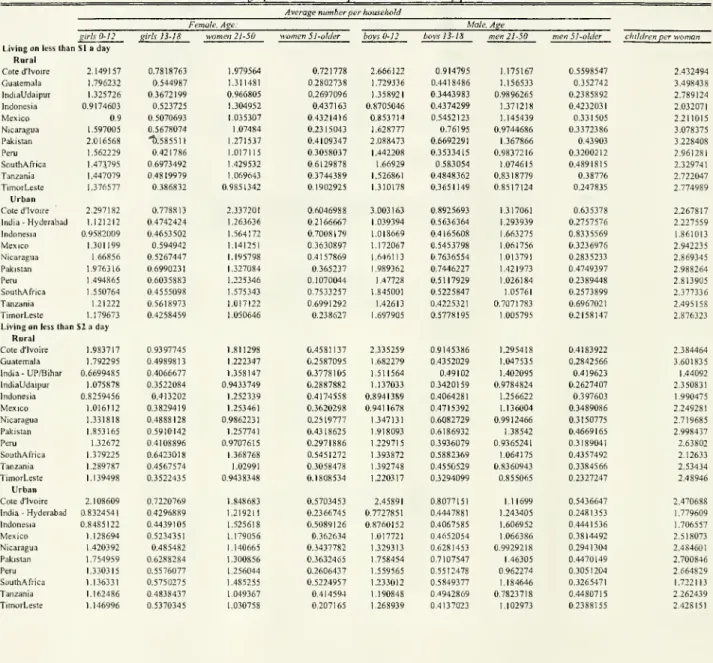

The

Living

Arrangements

of the

Poor

The

typical extremelypoor

family tendstobe

ratherlarge, atleastby

the standardsof

today'srich countries.

The number

of

familymembers

variesbetween

about 6and

about 12,with a

median

value (across the differentcountries) ofbetween

7and

8,compared

to 2.5 in the2000

U.S. census, forexample.Unfortunatelynot all surveys reportfertilityrates,

which

would

have been

the idealway

tocheck

how

much

of

thesehighnumbers

comes

from

the fact that here are a lotofchildren.

The

datadoeshowever

giveussome

broad

measures

oftheagestructure inthese"*The

extremely poorarelessnumerous, butas

we

observed above, our conclusionsare largelyindependentofthefamilies (the

number

ofthosebelow

13,between

13and

18,above

51, etc.).The

number

of

adults (i.e. those over 18) rangesfrom

about 2.5 toabout 5, withamedian

of about 3,which

suggests a family structurewhere

it iscommon

foradultsto live with people theyare not conjugally relatedto (parents, siblings,uncles, cousins, etc.). Thisis acommon

findingin theliterature

on

developingcountries,and

hasoftenbeen

relatedto the fact thatwhen

everypenny

counts, ithelpsto spreadthefixed costs ofliving (likehousing) overa larger

number

ofpeople. Consistent withthis view,

we

do

see a fallinfamily sizewhen we

go

from

theextremely

poor

to the entiregroup

below $2

a day, ofthe orderof one

halfofone

person ormore, though atleast

some

partofthiscomes

from

the fact thatthe extremelypoor

familieshave

more

children living*&with them.The

other fact isthat therearea largenumber

ofchildreninthese families. Thisdoesnot necessarily

imply

high levelsoffertility,as families oftenhave

multiple adultwomen.

When

we

lookatthenumber

ofchildren (ages to 18)perwoman

in thechild-bearing age(ages21-50)

we

getnumbers between

2and

4inboththeruraland

theurban sample,though

the urbanratiostendto be slightlylower.

These

would

notbe especiallyhigh iftheywere

actually fertilityrates,but they are

not—

forexample, a 51 year-old couldhave

a childwho

isnow

36,butwe

onlyinclude thosewho

arebelow

18.A

more

useful exercise withthis data isto

compare

thenumber

ofyoung

people (thosebelow

18) inthese families withthenumber

ofolderpeople (those

above

51).The

ratiovariesbetween

3and

9 in the ruralsample

withamedian of

6,and

between

2and

11 inthe urban sample, with amedian

once again ofaround

6.The

correspondingnumber

intheU.S. is around 1. This is averyyoung

population.One

reasonthe population isyoung

is that thereare alot ofyounger

people,which

reflectshigh fertility ifnot

now,

atleast inthe recentpast.A

second

reason isthat there areactuallyvery

few

olderpeople.The

ratio ofthenumber

olderpeople(overage 51)tothenumber

of people of "prime-age" (21-50) tendsto bebetween

0.2and

0.3 inboth the ruraland

theurban sample.

The

correspondingnumber

in the U.S., forexample, isapproximately 0.6.The

difference probablyowes

a lottothehighermortalityratesamong

thosewho

areolderand

poor

inpoor

countries,though

itis possiblethatolderpeople are underrepresentedin oursample because

they tendto be richer.However

inthe lattercase,we

might

have

expected tofind

more

oftheolderpeopleamong

thepoor

(ascompared

to the extremely poor),whereas

inthedata thereis

no

clear pattern.How

the

Poor

Spend

Their

Money

A

common

image

oftheextremelypoor

isthattheydo

not get tomake

many

realchoices. Indeedthere

must

besome

peoplewho

work

as hard astheycan—

which

may

notbeparticularly hard, becausethey areunderfed

and

weak

—

and

earn barelyenough

to covertheirbasic needs

which

theyalways

try to fulfill inthe leastexpensiveway.

Historically,povertylines in

many

countrieswere

originallysettocapture exactlythis definitionofpoverty—

atthebudget

needed

tobuy

a certainamount

ofcalories, plussome

other indispensable purchases(such as housing).

A

"poor" personwas by

definitionsomeone

withoutenough

toeat.Yet

the averagepersonlivingatunderSl perday

does notseem

toputevery availablepenny

intobuying

more

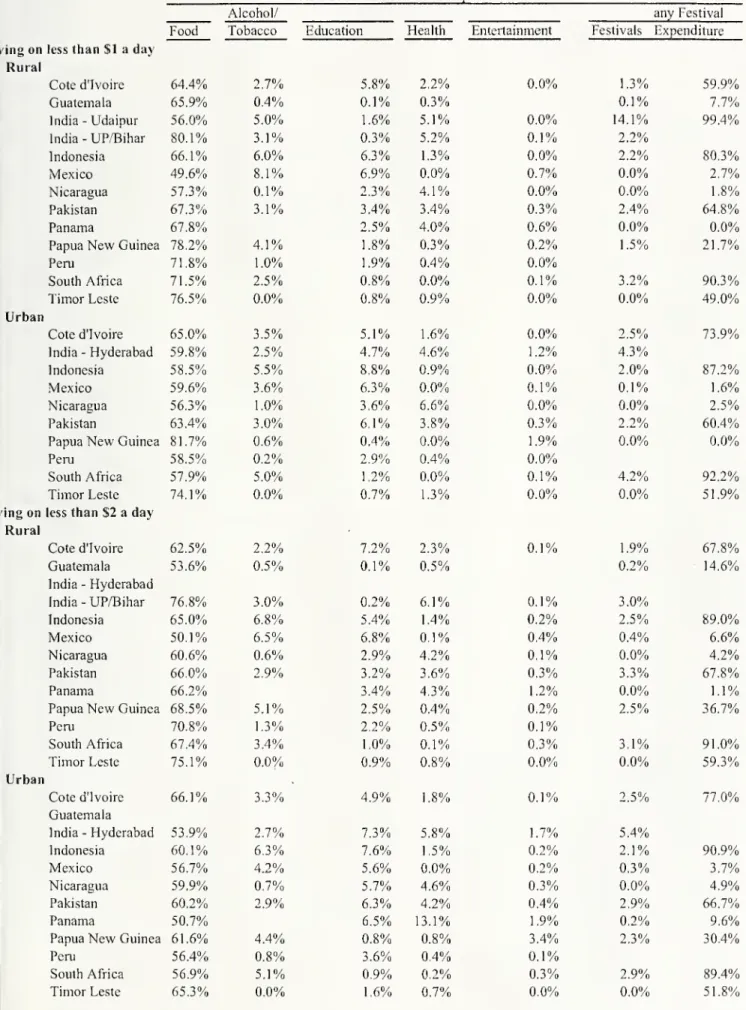

calories.Among

our 13 countries, foodtypically representsfrom 56

to78 percent

among

ruralhouseholds,and

56 to74

percentin urbanareas.For

theruralpoor

inMexico,

slightly lessthanhalfthebudget (49.6 percent) allocatedtopurchase food.^Of

course they couldbe spending therestof

themoney

on

othercommodities

which

they also greatly need.

Yet

among

thenon-food

items thatthepoor

spend

significantamounts

of

money

on, alcoholand

tobaccoshow

up

prominently.The

extremelypoor

in rural areas spent4.1 percentof

theirbudgeton

tobaccoand

alcohol inPapua

New

Guinea, 5.0 percentinUdaipur, India; 6.0percentin Indonesia

and

8.1 percentinMexico; though

inGuatemala,

Nicaragua,

and

Peru,no

more

than 1 percent ofthebudgetgets spenton

thesegoods

(possiblybecausethey prefer other intoxicants).

Perhaps

more

surprisingly, itisapparentthatspendingon

festivals is an importantpartof

thebudget formany

extremelypoor

households. InUdaipur, overthecourse ofthe previousyear,

more

than99

percentofthe extremelypoor

householdsspentmoney

on

awedding,

afuneral, or areligious festival.

The

median household

spent 10 percentofitsarmual budgeton

festivals. In SouthAfrica,

90

percentofthe households livingunder

$1 perday

spentmoney

on

festivals. InPakistan, Indonesia,

and Cote

d'lvoire,more

than 50 percentdid likewise.Only

insome

LatinAmerican

countries inoursample—

Panama,

Guatemala,Nicaragua—

are festivalsnot a notable partoftheyearlyexpenditure for asignificant fraction

of

thehouseholds.However

in theLSMS

surveys,unlike theUdaipur

survey,peopleare notaskedtoaccountseparately forthe foodthatthey

bought

because therewas

afestival. Itis thereforeprobablyno

accident thatthe

Udaipur

number

is thehighest across the surveys,and

there isreason tosuspectthat

LSMS

numbers

would

have

been

higherhad

thedatabeen

directlycollected inthose surveys.

On

the otherhand,theunder

$1 perday

householdsspend

very littleon

theforms ofentertainmentthat are

common

in richcountries, suchasmovies, theater, orvideo shows. Inall13 ofthe countries in our sample,inthe

month

precedingthe survey theaverage extremelypoor household

spentless than 1 percenton any

ofthese forms ofentertainment.The

comparable

number

for theUnited States is 5 percent.We

can only speculate aboutthe roots ofthis difference:

Has

the importance giventofestivalsand

otherindigenous formsof

Thefactthattheshare spenton food,whichisoftenseenasaphysiological necessity, varies somuchacross

countriesisitselfinteresting.Onepossibilityisthat thisrepresents the factthatthepoorhavemorechoiceinsome

countries thaninothers,becauseconsumption goodsarerelativelyarecheaperrelative tofoodinsomecountries.

For example, India,alarge economywithalonghistoryof beingrelativelyclosed,has evolvedalargemenuof low-costandlower-qualityconsumer goodsthatareproducedalmostexclusivelyforthedomestic market,

examplesinclude tooth-paste,cigarettes,andclothing.Othercountriesmustbuythesegoodsathigherpriceson

theglobalmarket. Ifthemanufacturedconsumer goodsthattheaverage personbuysin Indiatendtobe

inexpensiverelative to theirtraded counterparts, theratiobetweentheconsumption exchangerateatpurchasing

powerparityandtheofficialexchangerateoughttoberelativelylowinIndia. Moregenerally: thelowerthis ratio,thelowertheshareoftheconsumptionthatshould bemadeupoffood. Inourdata,itturnsoutthatthe

correlationbetweentheratioofthepurchasingpowerparityexchangerateforconsumptiontotheofficial

exchangerate in 1993andthe shareof expenditurespentonfoodis0.33amongthese 12 countries,althoughthis sampleisof coursetoosmallto supportdefiniteconclusion.

entertainment

crowded

outmovie-going, orit is lack ofaccess tomovie

theatresand

such, thatgives festivals theplace thatthey

occupy

in theirlives.The

propensity toown

a radio or atelevision, awidespread

form

of entertainment forAmerican

households varies considerablyacross countries. For example,among

ruralhouseholds livingunder$1 per day,

ownership

ofaradio is 11 percentin theUdaipur

survey,almost

60

percent inNicaragua

and

Guatemala,and

above 70

percentin South Africaand

Peru.Similarly,

no one

owns

a televisionin Udaipur, butinGuatemala

nearly a quarterofhouseholds do,

and

inNicaragua, thepercentage is closerto a halfThese two

phenomena

appeartobe related. InUdaipur,where

the share spenton

festivals is the highest, radio

and

televisionownership

isvery low. InPakistan, the fractionspent

on

festivals is 3.3 percentand

only30

percenthave

aradio.By

contrast, inNicaragua

where

57percent ofthe rural poor households,respectively,have

a radioand

21 percentand

19percent

own

atelevision, veryfew

householdsreport spending anythingon

festivals.^One

wrinkle

on

this explanationis thatthe urbanpoor

who

aremuch

more

likely toown

a televisionthanthe rural

poor

(60 versus 33 percent in Indonesia, 61 versus 10 percentinPeru, 38 versus17percent in SouthAfrica),

do

notspend

lesson

festivals than theirruralcounterparts.While

this observationisbased

on

onlyafew

datapoints, ithintsatthe possibility of anunmet

demand

forentertainmentamong

the ruralpoor—

theywould

also like tobuy

atelevision, butperhaps the television signaldoes notreach theirneighborhoods.

Ineither case,it ishardtoescapetheconclusionthatthe

poor do

see themselvesashaving asignificant

amount

ofchoice,and

choose notto exercise itinthedirection ofspendingmore

on

food—

the typicalpoor

household

inUdaipur

couldspendup

to30 percentmore

on

food than itactuallydoes,justbased

on what

itspendson

alcohol, tobacco,and

festivals.Indeed

inmost

ofthe surveysthe share spenton

food isaboutthesame

forthepoor and

theextremely poor, suggestingthatthe extremely

poor

do

notfeel an extracompulsion

topurchasemore

calories.This conclusion echoes anold findinginthe literature

on

nutrition:Even

theextremelypoor

do

notseem

tobe ashungry

foradditional calories as onemight

expect.Deaton and

Subramanian

(1996), using 1983 datafrom

the Indian state of Maharashtra,found

thateven

forthe poorest, a 1 percentincrease

on

overallexpendituretranslates intoabout atwo-thirdsofapercent increase in thetotal food expenditure ofa

poor

family.Remarkably,

the elasticity isnotverydifferent forthepoorest individualsinthe

sample

and

the richest(althoughnobody

is particularlyrich inthis sample).The

Deaton and

Subramanian

estimate isone

ofthe higher estimates. Straussand

Thomas

(1997)found

an elasticityofdemand

for food withrespecttoexpenditure percapitaof about aquarterforthepoorestBrazilians.

Theultimatesourceofvariation heremight be therelativepricesofradiosandtelevisions. Thereisastrong

correlationbetweentheratioofthepurchasingpower exchange rateforconsumptionandtheofficialexchange

rateandtheprobabilitythatahouseholdownsa radio(thecorrelationis0.36). Thelogicisprobablyquitesimilar

to theargumentpresentedearlier inthecontextof foodconsumption(vizfootnote ?footnote 11?!1).Radiosare

tradable (theyareallmadeinChina). Sinceamongmanufactures,non-tradablegoodsare

much

lesscostlyinsomecountriesthanothers,whiletradedgoodstendtobemore similarly priced,peopleatthesame expenditure

Another

way

tomake

thesame

point is to lookatwhat

ediblestheextremelypoor

arebuying.

Deaton and Subramanian

(1996)note thatamong

grains, in terms ofcaloriesperrupee,themillets (jowar

and

bajra) are clearly the bestbuy.Yet

in theirdata,only abouttwo-thirdsofthetotal spending

on

grains ison

these grains,while another20

percentison

rice,which

costsmore

than twice asmuch

percalorie,and

aftirther 10 percent or so is spenton

wheat,which

isa

70

percentmore

expensiveway

to getcalories. In addition, thepoor spend

almost 7 percentoftheirtotalbudget

on

sugar,which

is bothmore

expensive than grains as asourceofcaloriesand

bereftofany

othernutritionalvalue.The same

affinity forsugaralsoshows up

in ourUdaipur

data:The

poor

spend

almost 10 percentoftheirfood budgeton

thecategory "sugar,salt

and

otherprocessed foods" (thisdoes not includecooking

oil,which

makes

up

another 6percentoftheexpenditures

on

food).Even

forthe extremelypoor, for every 1 percent increaseinthefoodexpenditure, abouthalfgoes intopurchasing

more

calories,and

halfgoesintopurchasing

more

expensive (andpresumably

better tasting) calories.Finally, tothe extent that

we

cantell, thetrendseems

tobe

tospend

even

lessmoney

on

food. InIndia, forexample

itwent from 70

percentin 1983 to 62 percent in 1999-2000,and

the share ofmillet inthe food budget

dropped

tovirtuallyzero (Deaton,2005).Not

surprisingly, the

poor

arealsoconsuming

fewercalories over time(Meenakshi and

Vishwanathan,

2003),though

it ispossible that thischange

reflectsthe fact theirwork

involveslessphysical effort(Jha,2004).

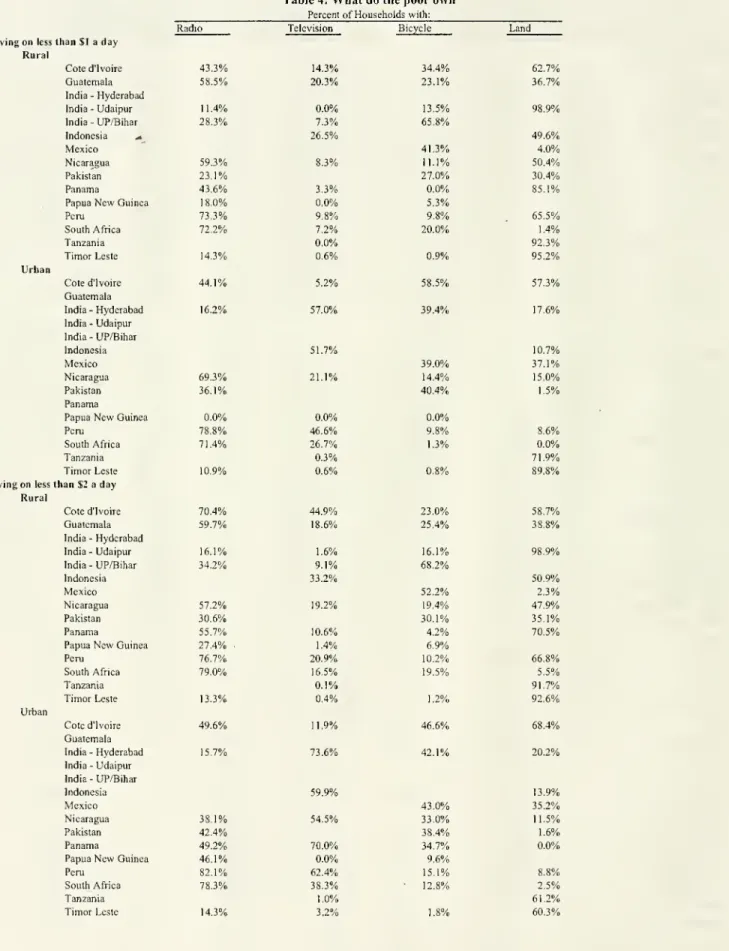

The Ownership of

AssetsWhile

all the surveyshave

some

information aboutassets, thelistofassets varies.To

obtaina relatively coherent listacross countries,

we

focuson

radios, televisions,and

bicycles.The

share of peoplewho own

theseparticular assets varies significantly across countries.As

we

already discussed,ownership

ofradioand

television varies a lotfrom

countrytocountry,butis

low

in severalofthose countries.One

reasonmay

be

thelack ofsignal.The

other

may

be thatitis noteasytobuy

a television ifyou

are extremelypoor: It isan expensiveand

lumpy

transactionthatone

hasto saveup

forifone

isbom

poor.We

do

see a fairly steepincome

gradient intheownership

ofradioand

television: Inall countries,the share ofruralhouseholds

owning

a television is substantially larger forthosewho

liveon

less than $2 aday

thanthoseliving

on

less than $1 a day. For example, the shareowning

a television increasesfrom

14percent forthoselivingon

$1 aday

to45

percent forthose livingon

less than$2 adollara

day

inCote

d'lvoire;from

7 to 17 percent in SouthAfrica;and

from

10 to 21 percentinPeru. Thispatternhas

been

observed inothercontexts(Filmerand

Pritchett,2001),and

hasbeen

the basisforusingthe lack of durablegoods

as amarker

forpoverty.Our

datasuggeststhat this

proxy

canbe appropriatewithina country, but itcouldeasilybe

misleadingtouse thismeasure

ina cross-country comparison.Among

productive assets,landis theone

thatmany

peopleintheruralsurveysseem

toown

though

there areenormous

country-to-countryvariation.Only

4 percent ofthose livingunder

$1 aday

own

land inMexico,

1.4percent in SouthAfrica;30

percent inPakistan,37

percentinGuatemala, 50 percent in

Nicaragua

and

Indonesia, 63 percent inCote

d'lvoire; 65percentinPeru;

and

85 percent inPanama.

In theUdaipur

sample,99

percent ofthehouseholds

below

$1 aday

own

some

landin additionto thelandon

which

theirhouse

isbuilt,when

theextremelypoor

do

own

land, the plots tend tobe quite small.The

median

landholdingamong

the poorwho

own

land isone

hectare orless in Udaipur, Indonesia,Guatemala and

Timor,

between

1and

2 hectares in Peru,Tanzania, Pakistan,and

between

2and

3 hectaresinNicaragua, Coted'lvoire,

and

Panama.

Apart

from

land, extremelypoor

households inrural areas tendtoown

very littleby

way

of

durablegoods, including productiveassets:34

percentown

abicycle inCote

d'lvoire,but less than 14 percent inUdaipur, Nicaragua,

Panama,

Papua

New

Guinea, Peru,and

EastTimor. InUdaipur,

where

we

have

detailedasset data,we

findthatmost

extremelypoor

households

have

abed

ora cotbutonlyabout 10 percenthave

a chair or a stooland

5 percenthave

atable.About

halfhave

aclockor awatch. Less than 1 percent hasan electric fan,asewing

machine,abullockcart, amotorized cycleofany

kind, oratractor.No

one

has aphone.

As

we

willseebelow,this isnotbecausemost

ofthesehouseholdsareemployees and

therefore

have

no

usefor such assets:On

the contrary,many

ofthe extremelypoor

householdsoperate their

own

businesses,butdo

sowith almostno

productiveassets.The

Pursuitof

Healthand

Well-beingShould

we

woiry

aboutthefact that thepoor

arebuying

less food than they could?According

toDeaton and

Subramanian

(1996),the poorestpeople—

the ones in thebottom

decileinterms of percapitaexpenditure

—

consume

on

averageslightly lessthan1400

calories a day. Thisis about halfofwhat

theIndiangovernment

recommends

foraman

withmoderate

activity, ora

woman

withheavy

physical activity.^The

shortfallseems enormous,

thoughone

could question

whether

theinitialrecommendation

was

appropriate.However,

theUdaipur

data,

which

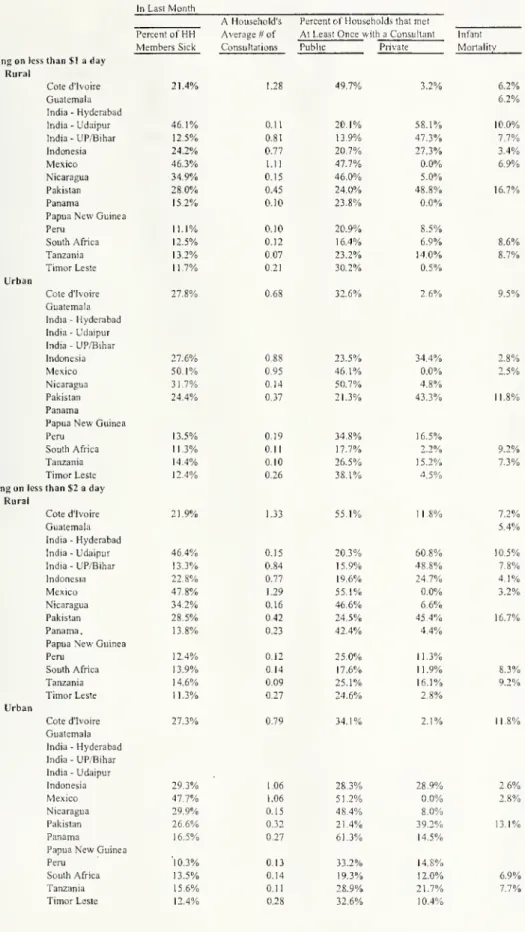

has other healthindicators, suggeststhathealth isdefinitely reason forconcern.Among

the extremelypoor inUdaipur, only 57 percentreport thatthemembers

oftheirhousehold

had

enough

to eat throughouttheyear.Among

thepoor

adults inUdaipur, theaverage

"body mass

index" (thatis, weight inkilograms dividedby

thesquare oftheheight inmeters) is 17.8. Sixty-fivepercentofadult

men

and

40

percentofadultwomen

have

abody

mass

indexbelow

18.5, the standardcutoffforbeingunderweight

(WHO

expert consultation,2004).

Moreover,

55 percent ofthepoor

adults inUdaipur

areanemic,which

means

theyhave

an insufficient

number

ofredblood

cells.The

poorare frequently sick orweak. InUdaipur, 72percentreportat leastone

symptom

ofdiseaseand

46

percent report an illnesswhich

has leftthem

bedriddenornecessitated a visitto the doctoroverthe lastmonth. Forty-threepercentofthe adults

and 34

percent ofthe adultsaged

under 50reporthaving difficultywith carrying outatleast

one

oftheir"activities ofdaily hving", such asworking

inthe field,walking, ordrawing

waterfrom

awell. Diarrhea isextremely frequentamong

children.About

one-seventh ofthepoor have

vision problems,which

may

alsobedue

tonutritional deficits (causedby

either

poor

nutrition, or thediseases thatafflictthem, or acombinationof

the two).Detailed information

on

health is not availablein allthe surveyswe

have, butmost

reporthealth episodes thatleft ahousehold

member

bedridden foraday

ormore, or requiredthem

to see a doctor.While

this datais less thanperfect, giventhatthepoormay

be

lessprone'See htlp:''.'ww'.v.t'ao.org/dociimeni:s/show cdr.asiy^irl rile~''DOCREP/xfl

to recall

and

reportsuch sicknesses than therich, the general pattern is ofaremarkably

highlevel ofmorbidity.

Among

theruralpoor

livingunder

$1 aday

inPeru, SouthAfrica, EastTimor,

Panama, and

Tanzania,between

11and

15 percent of households report havingamember

eitherbeing bedridden for at least aday

orrequiringa doctor.The

number

isbetween

21and 28

percentin Pakistan, Indonesia,and

Coted'lvoire,and

between

35and

46

percent inNicaragua, Udaipur,

and Mexico.

The

poor

generallydo

notcomplain

abouttheirhealth—

butthen theyalsodo

notcomplain

aboutlifein general either.

While

thepoor

certainly/ee/ poor, their levels ofself-reportedhappinessor self-reported healthlevels are notparticularly

low

(Banerjee, Duflo,and

Deaton,2004).

On

theotherhand, thepoor

do

reportthatthey areunder

a greatdeal ofstress, bothfinancial

and

psychological. InUdaipur, about 12 percent saythat therehasbeen

aperiodofone

month

ormore

inthe lastyearinwhich

theywere

so "worried, tense, oranxious"that itinterferedwith

normal

activities like sleeping,working,and

eating.Case

and

Deaton

(2005)compare

datafrom

South Africatothedatafrom

Udaipur

and

datafrom

theUnited States.They

findthatthe answers ofpoor

South Africansand poor

Indians about stress lookverysimilar, whilereported levelsofstress arevery

much

lowerin theUnited States.The

most

frequentlycitedreason forsuch tensions ishealth

problems

(citedby 29

percent ofrespondents), withlackof food

and

deathcoming

next(13 percenteach).Over

thelastyear, in45 percent ofthe extremely

poor

households inUdiapur

(and 35 percent ofthoseliving under$2 a day)adults

had

to cutthesize oftheirmeal

atsome

pointduringtheyearand

in 12percent

of

them, childrenhad

tocut the sizeoftheirmeals. In the extremelypoor

householdsunder

$1 perday,37

percent report that,atsome

pointin thepast year, the adults inthehousehold

went

withoutameal

for an entireday. Cuttingmeals

is also strongly correlatedwith unhappiness.Carrying

enough

savingstomake

sure thattheyneverhave

tocutmeals,shouldnotbetoo hard forthesehouseholds since,as noted above, they

have

substantial slack in theirbudgetsand

cuttingmeals

isnot thatcommon.

Itwould

alsomake

iteasierforthem

todealwithhealthcare emergencies.

As

such,saving abitmore would seem

likea relatively inexpensiveway

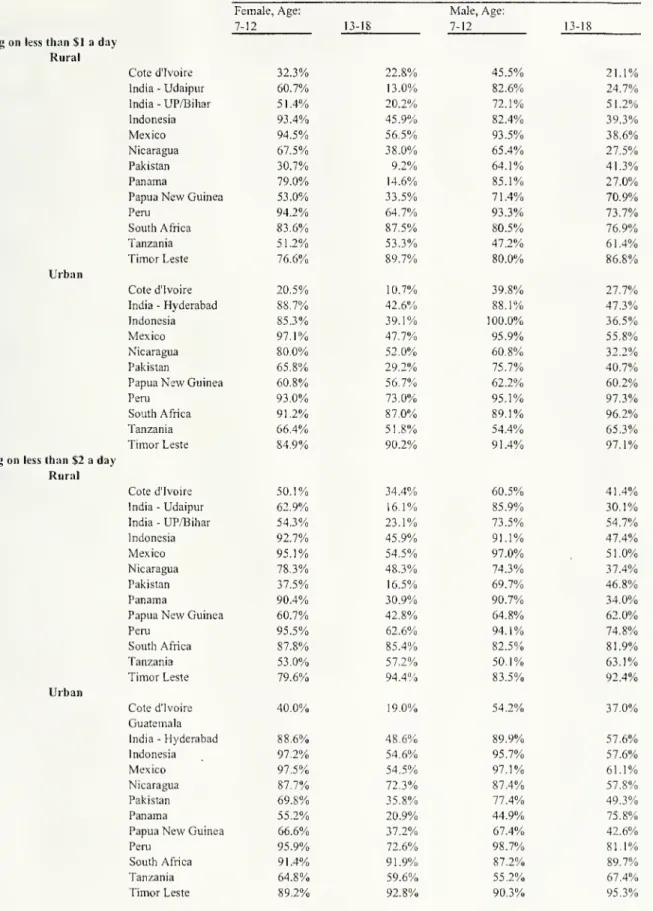

toreducestress.InvestmentinEducation

The

extremelypoor

spend

very littleon

education.The

expenditureon

educationgenerallyhovers

around

2percent ofhousehold

budgets: higherinPakistan(3 percent),Indonesia(6 percent)

and Cote

d'lvoire (6percent), butmuch

lowerinGuatemala

(0.1

percent),

and

SouthAfrica (0.8percent).The

fractiondoes notreallychange

verymuch when

we

go from

thepoor

to theextremelypoor, orfrom

rural areastourbanareas,though

inafew

countrieslike Pakistan,urbanfamilies

spend

substantiallymore

thanrural families. Thislow

level of expenditure

on

educationis notbecause the childrenareoutofschool. In 12 ofthe 13 countriesinour sample, withthe exception ofCote

d'lvoire, atleast50 percentof

bothboys

and

girlsaged

7to 12 in extremelypoor

households are in school. Inabout half the countries,theproportion enrolled is greaterthan 75 percent

among

girls,and

more

than 80 percentamong

boys.

The

reason spending islow

is thatchildreninpoor

households typicallyattend publicmore

on

education, itis typically becausegovernment

schoolshave

fees (as inIndonesiaand

Cote

d'lvoire).What

they aredoingmight

therefore beperfectly sensible, given thatthis is thereason

why

public educationexists.The

one

concerncomes

from

themounting

evidence,reported below,thatpublic schools are often dysfunctional: Thiscould

be

thereasonwhy

even

very poorparents in Pakistanare pullingtheirchildren out ofpublic schools

and

spendingmoney

tosendthem

to private schools.How

the

Poor

Earn

Their

Money

Walking

down

themain

street ofthe biggestslum

in themedium

sized Southern Indiancity of

Guntur

atninein themorning, thefirstthingone

notices are the eateries: In frontof

every sixth

house

that directly faced the road,by

ourcount, therewas

awoman

sittingbehindalittlekerosene stovewith a

round

cast-iron griddleroasting on it.Every few

minutessomeone

would

walk up

toherand

ordera dosa, the riceand beans pancakes thatalmost everyone eats forbreakfast in SouthIndia.She

would

throw

a cupful ofthe batteron

the griddle, swirl itaround

to coveralmosttheentiresurfaceand

drizzlesome

oilaround

theedges.A

minute

ortwo

later, shewould

slide an off-whitepock-marked pancake

off the griddle,douse

it insome

sauce, folditina

newspaper

orabanana

leafand

hand

itto her client, inreturn for arupee(roughly 15 cents, atPPP).

When

we

walked back

down

thatsame

street anhour

later, thewomen

were

gone.We

found

one insideherhouse, fillingher daughter's platewith lunch thatshehad

cooked

whilemaking

the dosas.She

toldus that laterthatday, shewas

goingout tovend

hersaris, the longpiece ofdecorative cloth thatIndian

women

drapearound

themselves.She

getsplainnylonsaris

from

theshop

and

stitchesbeads and small shiny pieceson

them,and once

aweek,

she takesthem from house

tohouse,hoping

thatwomen

would

buy

them

towear on

special occasions.And

theydo

buy

them, she said confidently. All the otherdosa

women

we

met

thatday had

a similarstory:once

they aredone

frying dosas, theydo something

else.Some

collect trash; othersmake

picklesto sell; otherswork

as laborers.Entrepreneurship

and

MultipleOccupations

Among

thePoor

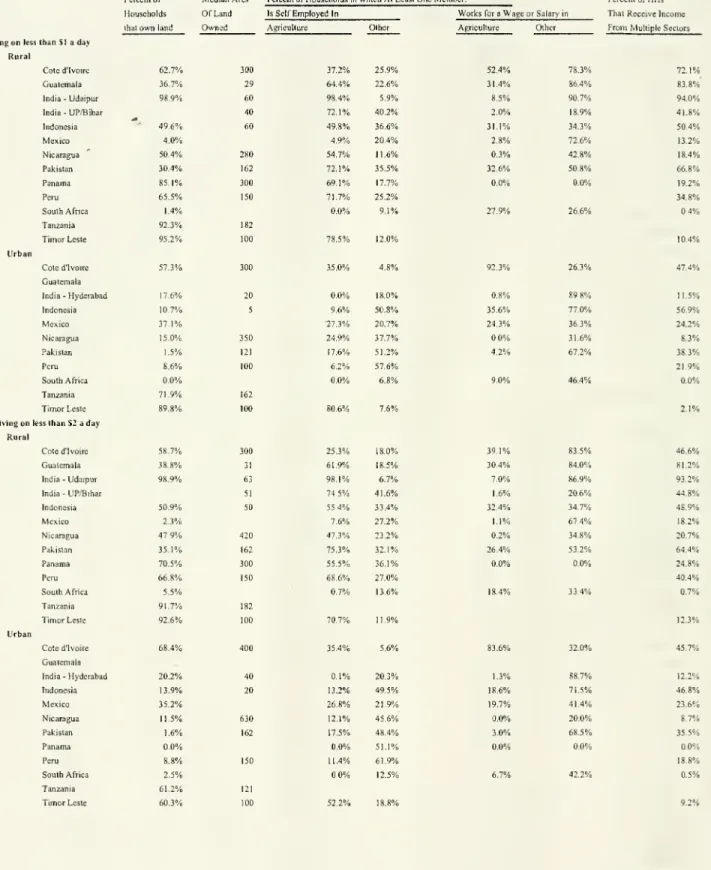

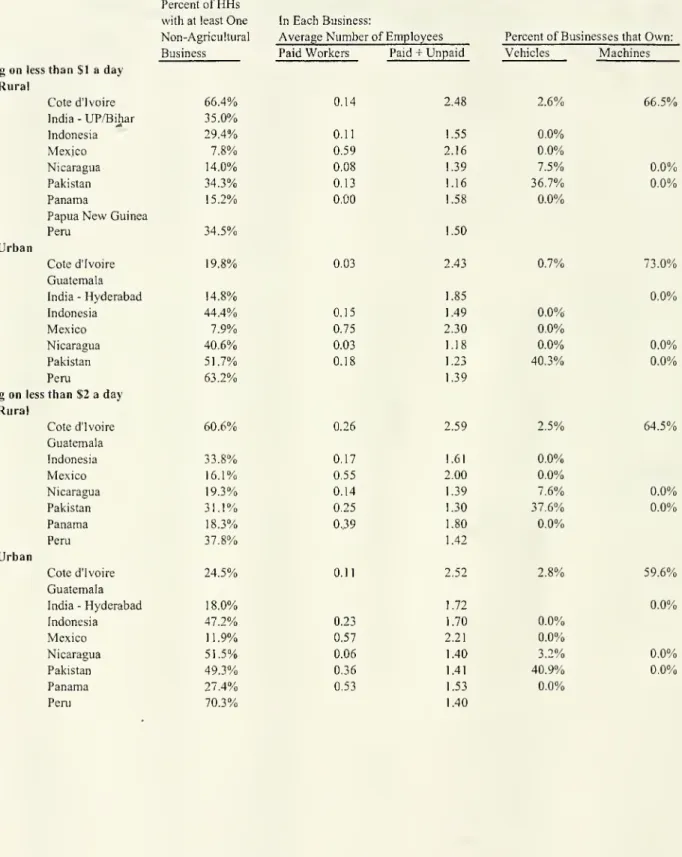

Allovertheworld, a substantialfraction ofthe

poor

actas entrepreneursin thesense ofraisingthe capital, carryingout the investment, and beingthe fiill residualclaimants forthe

earnings. InPeru,

69

percentofthehouseholdswho

liveunder

$2 aday

inurbanareas operatea non-agricultural business. InIndonesia, Pakistan,

and

Nicaragua, thenumbers

arebetween 47

and

52percent.A

large fraction ofthe ruralpoor

operate afarm (exceptinMexico

and

SouthAfrica,

between

25 percent and 98 percentofthe householdswho

earn less than adollaraday

reportbeingself

employed

in agriculture).^Moreover,

many

ofthe ruralpoor

(from 7 percentin

Udaipur up

to 36 percentinPanama)

alsooperate anonagricultural business.The lowlevelofagricultureamongtheextremely poorinSouthAfricaiseasily explained. Theblackpopulation,

whichcontainsalmostalloftheextremelypoorpeople,werehistoricallyunderthe apartheidregimenotallowed

toown landoutside the"homelands,"andmostofthe landinthehomelandswasnotworthcultivating.

Many

poor

householdshave

multipleoccupations. Like thedosa

women

of Guntur, 21percentofthehouseholds livingunder

$2

aday

inHyderabad

who

have

a business actuallyhave

more

than one, while another 13 percenthave

bothabusinessand

a laborer's job.Thismultiplicity of occupationsinurbanareasis

found

inmany

other countries aswell, though noteverywhere.

Among

thoseearning lessthan $2 aday,47

percent oftheurban householdsinCote

d'lvoireand

Indonesia get theirincome from

more

thanone

source;36

percentinPakistan; 20.5 percentin Peru;

and

24

percentinMexico.

However,

inurban South Africaand

Panama,

almostno one

hasmore

thanone

occupationand

only 9 percentdo

soinNicaragua

and

Timor

Leste.^ 'Thispattern

of

multiple occupations is strongerin rural areas. InUdaipur

district, aswe

discussedearlier, almost

everybody

owns some

landand

almosteverybody

doesatleastsome

agriculture.

Yet

only 19 percentofthehouseholdsdescribe self-employmentin agriculture asthe

main

sourceoftheir income.Working

on

someone

else's landiseven

rarer, with only 1percentreportingthis astheir

main

sourceof income. Inotherwords, thepoor

cultivate thelandthey

own, no

lessand

usually,no

more. Yet, agriculture isnot the mainstay ofmost of

these households.The

most

common

occupation forthepoor

inUdaipur

isworking

as a dailylaborer: 98 percentof households living

under

$1 perday

inruralareas reportdoingthisand 74

percentclaim itis their

main

sourceof

earnings.Thispatternis confirmed

by

datafrom

asmallersurvey of27

villagesrandomly

sampled from

eightdistrictsinWest

Bengal

(Banerjee, 2006). Inthis survey,even

householdsthat claim to

be

the operators for a plot ofland,spend

only40

percent oftheirtime inagricultural activities

on

theirown

land.The

fraction isnot verydifferent formen

and

women

—

women

do

less direct agriculturalwork

butmore

animal rearing,along withgrowing

fruits

and

vegetables. Theirotheractivities include teaching,sewing

and

embroidery,unpaid

household

work,and

gathering fuel. Strikingly, almost 10percentof

thetimeof

the averagehousehold

is spenton

gathering fuel, eitherforuse athome

orfor sale.The

median

familyinthis survey has three

working

members

and

seven occupations.In

most

oftheLiving StandardMeasurement

Surveys,households arenotaskedtheirmain

sourceofearnings,butthe patternofdiversificationamong

ruralhouseholds is apparentnevertheless. In

Guatemala,

65 percent oftherural extremelypoor

say theygetsome

income

from

self-employmentinagriculture, 86 percentwork

as laborers outsideagriculture,and

24

percentare self-employedoutside agriculture. In Indonesia, 34 percent

of

the rural extremelypoor

householdswork

as laborers outsideofagriculture,and

37 percent earnincome from

selfemployment

outsideofagriculture. In Pakistan, 51 percentoftheruralextremelypoor

earnincome from

laboroutside ofagriculture,and

35 percentfrom

abusiness outside ofagriculture.Overall, the fractionofthe ruralextremely

poor

householdswho

reportthatthey conductmore

than

one

type ofactivity toearna living is 50 percent inIndonesia, 72 percent inCote

d'lvoire,84 percent inGuatemala,

and

94

percent in Udaipur. It issmaller,butnot negligible—between

10

and

20

percent—

in Nicaragua,Panama,

Timor

Teste,and Mexico.

Once

again, anexception to thisgeneral pattern is SouthAfrica,

where

less than 1 percent oftherural poororextremely

poor

reportmultiple occupations.This

may

howeverbeadataproblem; AnthropologistsdoclaimthattheyobservemultipleoccupationsinSouth African households(FrancieLund,verbalcommunicationtoAngusDeaton).Temporaiy

Migration toWork

Where

do

ruralhouseholds,which

areoften awalk

ofa half-hour ormore

from

the nearest road, findallthisnon-agriculturalwork?

The

answer

turns outtobe theobvious one:they migrate.

Temporary

migration israrelydocumented

insurveys, butintheUdaipur

survey,which

had

questionsaboutthisactivity,60

percent ofthe pooresthouseholdsreport thatsomeone

from

theirfamilyhad

lived outside forapartoftheyearin orderto obtainwork. For 58 percent ofthe families, thehead

ofthehouseholdhad

migrated.The

migrants typicallycompletemultipletrips in a year.

However,

peopledo

not leaveforverylong:The

median

lengthofacompleted

migration isone

month,and

only 10 percentof migration episodes exceedthreemonths.

Nor

do

most

ofthemigrants travelvery far: 28 percentstay inthe districtof Udaipur,and

only42

percent leave the stateofRajasthan.In contrast,

permanent

migrationforwork

reasons israre, althoughmany

women

move

when

they get married.Even

ifwe

lookathouseholds currently livinginurbanareas,where

theinflow

of immigrants

ispresumably

higherthanin rural areas,the share of extremelypoor

households

who

had one

member

thatwas

bom

elsewhere andhad

migrated forwork

reasonswas

just4

percent in Pakistan, 6 percentinCote

d'lvoire, 6 percent inNicaragua,and

almost10 percent in Peru.

The

1991Census

ofIndia reports that only 14.7percentof

themale

population lives

somewhere

otherthanwhere

theywere

bom.

Indonesiais theonly country inourdata

where

theproportionishigher: 41 percentofthe urban householdscame

from

elsewhere. Indonesia isalsothe only countiyin this

sample where

migrationwas

explicitlysubsidized.

Lack

of

SpecializationA

patternseems

to emerge.Poor

familiesdo

seekouteconomic

opportunities, but theytendnotto get too specialized.

They

do

some

agriculture,but nottothepointwhere

itwould

afford

them

afull living (forexample by

buying/renting/sharecroppingmore

land).They

alsowork

outside, butonly inshortbursts—theydo

notmove

pemianently

to theirplace ofoccupation.

This lack ofspecializationhas its costs.

Many

ofthesepoor

householdsreceivemost

oftheir

eamings from

theseoutside jobs, despiteonlybeingaway

for 18weeks

oftheyearon

average(in the caseof Udaipur).

As

short-term migrants,theyhave

little chance oflearningtheirjobsbetter orending

up

in ajobthat suits their specific talents orbeing promoted.Even

thenon-agriculturalbusinessesthatthepoor

operatetypically requirerelativelylittle specificskills.

For

example, thebusinesses inHyerabad

include 11 percenttailors, 8percentfruit

and

vegetable sellers, 17 percent small general stores, 6.6percent telephonebooths,4.3 percent auto owners,

and

6.3 percentmilk sellers.Except

for tailoring,none

ofthesejobsrequire thehigh levelsofspecialized

competence

that take alongtimeto acquire,and

thereforeareassociatedwith higher eamings. In severalways, thepoor

aretrading off opportunitiestohave

higherincomes.The

Problem

of Small

ScaleThe

businesses ofthepoor

typicallyoperate ataremarkably

small scale.As

we

saw,the average landholding forthose

who own

landisusually quite tiny,and

renting land isinfrequent. Furthermore,

most

ofthis landisnotirrigatedand

cannotbe used

allyear round.The

scaleof

non-agriculturalbusinessesrunby

the pooralsotendsto be pretty small. In the 13 countries inour sample, themedian

business operatedby

peoplelivingunder

$2 dollarsa

day

either in a rural oran urban location hasno

paidstaff,and

the averagenumber

of paidemployees

rangebetween

0.14 inruralNicaragua

to 0.53 in urbanPanama.

Businessesareoperated

on

averageby

1.38 (inPeru) to 2.59 (inCote

d'lvoire) people—

most

ofthem

beingfamily

members.

Most

ofthesebusinesseshave

veryfew

assets aswell. InHyderabad,

only20

percent

of

thebusinesses operate outofaseparateroom. InPakistan, about40

percentofthebusinesses ofthoselivingunder $1 or

$2

dollaraday have

a vehicle, butonly 4 percenthave

amotorizedvehicle

and

none have any

machinery. In other countries,even

non-motorizedvehicles arerare. In

Hyderabad,

where

we

have

an exhaustive listof business assets, themost

common

assets aretables, scales,and

pushcarts.Many

of

thesebusinesses areprobably operating attoo small a scalefor efficiency.The

women

making

dosasspend

alotof time waiting: having fewerdosa-makers

who

do

lesswaiting

would

bemore

efficient. In fact, itmight

make

sense in efficiency terms forthedosa-makers

towork

in pairs:One

tomake

thedosasand one

towrap

them

and

make

change.Markets

and

the

Economic Environment

of the

Poor

The

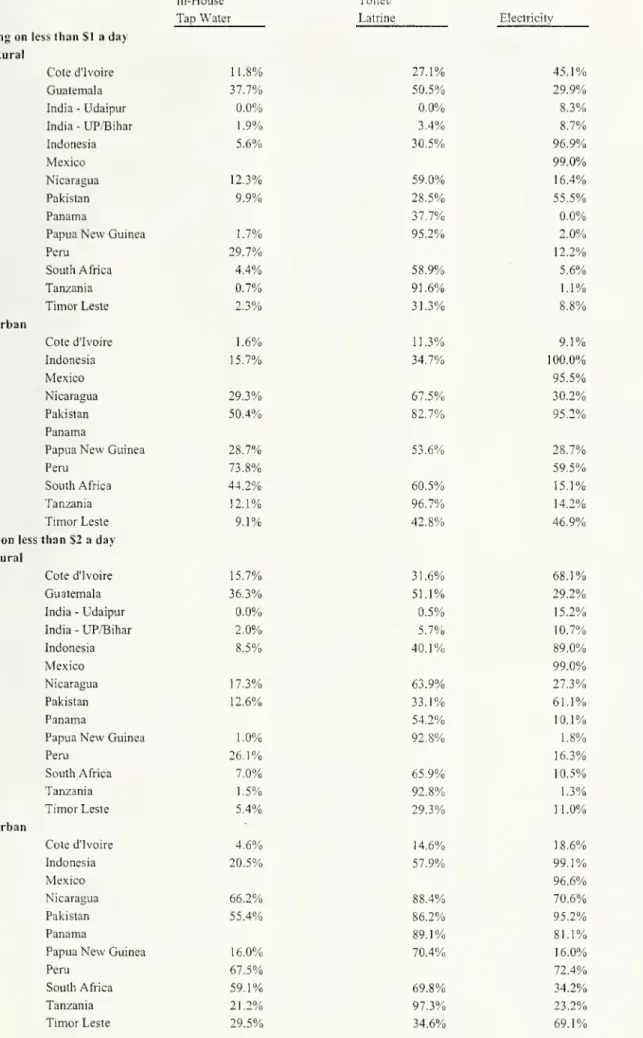

economic

choicesofthepoor

are constrainedby

theirmarket

environment.The

amount

theysave, forexample, should vary withtheiraccesstoa safeplacetoputtheirsavings. Otherconstraints result

from

a lackof shared infrastructure.When

the goverrmientbuilds awaterline to

your

neighborhood, for example,you no

longerneed your

own

well.This section focuses

on

markets.The

next takesup

the issueofinfrastructure.The

Market

for Creditand

thePoor

The

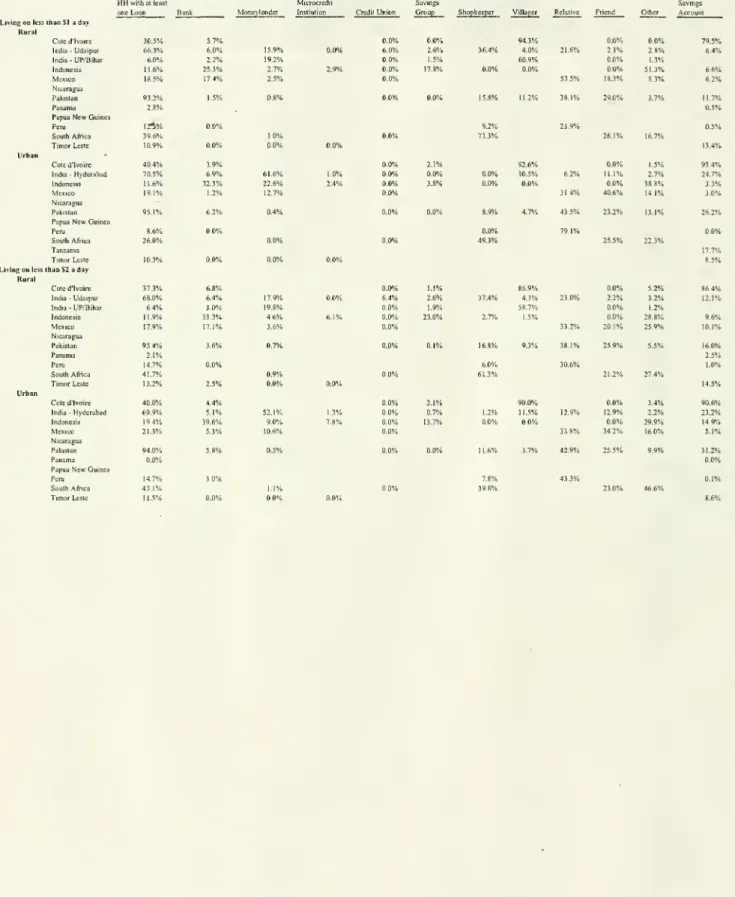

datafi-om our 13 countries suggests thatthefractionofruralextremelypoor

households having an outstanding debtvaries

between

countries,from

1 1 percentin rural EastTimor

to93 percent in Pakistan.But

what

isconsistent across the surveys isthat veryfew of

the

poor

households getloansfrom

a formal lending source.In the

Udaipur

sample, abouttwo-thirdsofthepoor

had

aloan at thetimeofthe interview.Of

these,23 percent arefrom

arelative, 18percentfrom

amoney

lender,37

percentfrom

a shopkeeper,and

only 6.4percentfrom

aformal source like acommercial bank

or acooperative. Lest

one

suspectthatthelow

shareofbank

creditisdue

tothelackofphysical access tobanks, a similar patternoccurs in urbanHyderabad,

where

householdslivingbelow

$2 a

day

primarilyborrow from moneylenders

(52 percent), friends orneighbors (24percent),and

familymembers

(13 percent),and

only 5 percentofthe loans are withcommercial

banks.The

one countiywhere

a substantial shareoftheloans tothepoor

are formal innature is Indonesia,where

thanks to effortsby

theBank

Rakyat

Indonesia, one-thirdofthe ruralpoor

households

borrow from

a bank. Inall theother countries, relatives,shopkeepers, andothervillagers foiTn,

by

far,theoverwhelming

sourceofborrowed

funds.Credit

from

informal sources tends tobe expensive. In theUdaipur

survey,where

we

have

dataon

interestrates not available inothersurveys, those livingon

less than $1 aday pay

on

average 3.84 percent permonth

for the credittheyreceivefrom

informal sources.Those

who

consume

between

$1 and $2 dollar aday

per capitapay

a little less: 3.13percent permonth. Thisis in partbecausetheyrely less

on

informal sourcesofcreditand

more

on

theformal sources than theextremely poor,

and

the formal sources are cheaper;and

inpartitreflectsthe fact thatinformal interest rates arelowerforthosewith

more

land—

the interest ratefrom

informal sources dropsby

0.40 percent permonth

foreach additionalhectare oflandowned.

The

monthly

interest ratewe

see intheHyderabad sample

iseven

higher: 3.94percent permonth

forthoselivingunder

$2 dollars a day. Thisreflects the fact thatfew

oftheseurbanpoor

householdshave any

landthattheycan use as collateral.These

highinterestratesseem

to occurnot directlybecause of highratesofdefault,but asaresultofthehigh costsofcontract enforcement.While

delay inrepayment

of informalloans isfrequent, defauhis actuallyrare (Banerjee

and

Duflo, 2005). For example,a"Summary

Reporton

Informal CreditMarkets

inIndia" reports thatacross four case studiesofmoney-lenders

inrural India,defaultexplainsonly 23 percent ofthe interest ratecharged(Dasgupta, 1989).

A

wellknown

studyofruralmoney-lenders

in Pakistanby

Aleem

(1990),findthatthe

median

rate ofdefault acrossmoney

lenders isjust2 percent.These

low

defaultratesarehowever

anything butautomatic: Contractenforcement indevelopingcountries isoftendifficult,

and

inparticular,it isnoteasytoget courts topunishrecalcitrantborrowers.

As

aresult, lenders oftenspend

importantresourcesmaking

sure that their loans getrepaid,which

iswhat

drivesup

the interestrates.The

factthat lendingdepends

so

much

on

effective screeningand

monitoringalsomeans

that lendingto thepoor

is especiallydifficult:

The

problem, atleast in part, is thatthepoor

have

very littleby

way

ofcollateral tosecure the loan

and

therefore lendershesitate totrustthem

with a lot ofmoney. Given

thatthe loanamount

will inany

case be small, it isnot always clearthat theprofitsfrom

thetransactionwill

be

largeenough

to coverthe costofmonitoring/screening.As

aresult, alotoflenders arereluctant to lend to thepoor.

Moreover

and

forthesame

reason, informal lenders located closetotheborrowers

may

be the only oneswho

are willingto lendto thepoor

—

sincemonitoring/screening isrelatively

cheap

forthem.The

trouble is thatthese infonnal lendershave

topay

more

for their deposits than themore

formal institutions, sincethey are lesscapitalized

and

less regulatedand do

nothave any government

guarantees. Thishigher cost ofdeposits getspassed

on

to poorer borrowers.The

gap

canbe

considerable—

inthe studyby

Aleem,

the cost ofcapital forthemoney-lenders

was

32.5 percentinayearwhen

banks

were

only

paying

10 percent for their deposits.The

Market

for Savingsand

thePoor

A

main

challengeforthepoor

who

try to saveisto find safetyand

a reasonablereturn.Stashing cash inside

your

pilloworelsewhere athome

is neither safenorparticularlywell-protected

from

inflation. In addition,recentresearchby

Ashraf, Karlan,and

Yin

(2005) inthePhilippines

and

Duflo,Kremer, and Robinson

inKenya

(2006) suggeststhatthe poor,Hke

everyone else,

have

problems

resistingthe temptationof spendingmoney

thattheyhave

athand.

Few

poor

householdshave

savings accounts.Except

inCote

d'lvoire,where 79

percentofthe extremely

poor

households under$1 aday have

a savings account, thefractionisbelow

14 percent inthe other countriesin ourdata. In

Panama

and

Peru, lessthan 1 percentof

suchhouseholds

have

a savings account. Inmost

countries, the share of households withasavingaccount issimilar in rural

and urban

areas,and

similarforthoseunder

$2 aday and

thoseunder

$1 a day.

Here

India appearsto be an exception, since only6percentof

theextremelypoor

households in rural

Udaipur have

asavings account, while25 percent ofthem

do

inthe cityof

Hyderabad.

A

lackofaccess to reliablesavings accountsappearscommon

to thepoor

everywhere,as

documented

in StuartRutherford's (2000) fascinating book,The

Poor

and

theirMonev

.Rutherford describes the

many

strategies thepoor

use to deal withthisproblem:They

form

savings "clubs,"

where

eachpersonmakes

surethattheothersdo

theirsavings. Self-helpGroups (SHGs),

popularinpartsofIndia,and

presentinIndonesiaas well, aresavingclubswhich

alsogive loans to itsmembers

outoftheaccumulated

savings (theyarealsosome

timeslinked to

bank which

offerthem

banks). In Africa, Rotating Savingsand

Credit Associations(ROSCAs)

allowpeopleto lendtheir savingsto each otheron

a rotatingbasis. Otherspay

deposit collectorsto collect theirdeposits

and

putthem

in abank.Yet

othersdeposit theirsavingswith local money-lenders, with creditunions (whichare essentially larger

and

much

more

formally organized Self-HelpGroups)

orinan accountatthe localpost office.And

thereason

why

many

ofthepoor

respondso well to micro-credit, isnot necessarilybecause itoffers

them

credit, butbecauseonce

you

take a loanand

buy

something

withit,you have

a disciplinedway

to save—

namely,by

payingdown

theloan.However

even

participationin semi-formal savings institutions(such as Self-helpGroups,

ROSCAs

and

Microfmance

Institutions), isnot nearly ascommon

among

thepoor

asone might have

expected.Even

inIndia, despite the highvisibility especially ofSHGs,

lessthan 10 percent ofthe

poor

in ourUdaipur and

Hyderabad

surveys are part of anSHG

oraROSCA.

The

majorityofthehouseholdswho

have

any

savings simplyhave

itatthebank.The

Market

for Insuranceand

thePoor

The

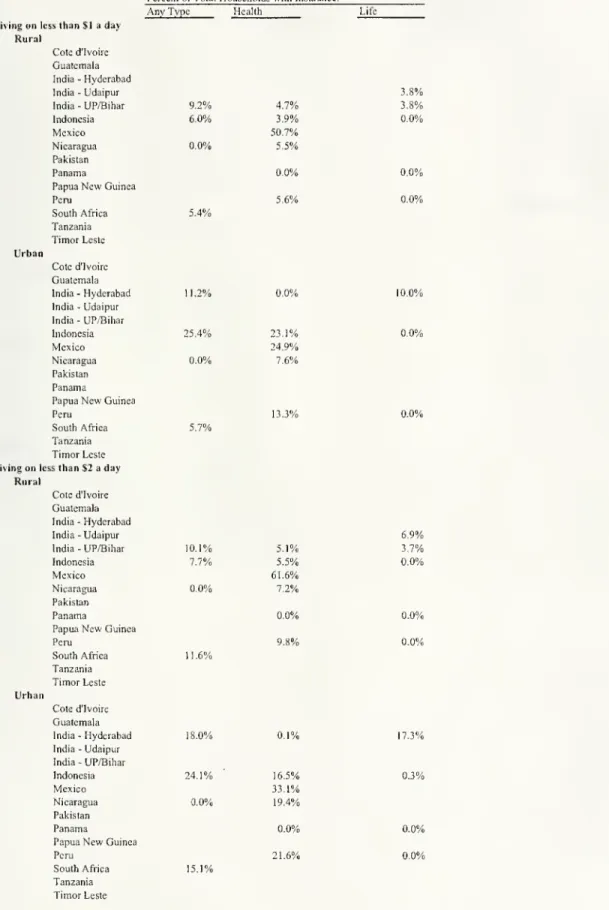

poor

have

verylittleaccessto formal insurance. Inmany

surveys, questions aboutinsuranceare not

even

asked. In the six ofthe sevencountrieswhere

thereis dataon

this, lessthan 6 percentoftheextremely

poor

are coveredby

health insurance ofany

kind.The

exceptionis

Mexico

where

abouthalfofthem have

coverage.The

numbers

arenotmuch

higherinurban areas. Lifeinsurance is abit

more

common

inIndia (andis, essentially, aform

of

savings).Four

percentoftheextremelypoor

inUdaipur and

10 percentinHyderabad have

life insurance.

Surprisingly,weather insuranceisalsoessentiallyabsenteverywheretheworld over(Morduch,2005),

althoughitwould seemstraightforwardtoprovideinsurance against obser%'edweatherpatterns.

Inprinciple, informal insurance canalsobe

had

through socialnetworks. For example,Udry

(1990)shows

thatpoor

villagers inNigeria live a lifethatis shapedby

a densenetwork

of

loan exchange:Over

the course ofone year, 75 percentofthe households hadmade

loans,65

percent hadborrowed money,

and 50percenthad been

both borrowersand

lenders.Almost

all

of

these loanstook placebetween

neighborsand

relatives.Both

therepayment

scheduleand

the

amount

repaidwere

affectedby

boththe lender's andthe borrower's currenteconomic

conditions,underlining the role ofthese informal loans inprovidinginsurance.

Rosenzweig

and

Munshi

(2005), arguethat thesame

processhappens

inIndiathroughthejatior sub-castenetworks.

Yet

these infonnal netv^'orkshave

onlya limitedability toprotectthe householdsagainstrisk.

The

consumption

ofpoor

householdsis strongly affectedby

variations intheirincomes, as has

been

shown

by Deaton

(1997) inCote

d'lvoire,Rosenzweig and

Munshi

(2005) in India,

Fafchamps and

Lund

(2003) inthe Philippines,and

Townsend

(1995) inThailand.

Poor

households also bearmost

health-carerisks (bothexpendituresand

foregoneearnings) directly. For example, Gertler

and

Gruber

(2002) findthat inIndonesiaa declineinthe health index ofthe

head

ofthe householdis associated witha declineinnon-medicalexpenditures. In Udaipur, large expenditures

on

health (S70and

higher, atPPP)

arecoveredby

borrowing

ordissa\ing.Only

2percent ofthese expenseswere

paidforby someone

else,and

none

came

from

the self-help groups.Twenty-four

percentofthehouseholds inHyderabad had

toborrow

topay

forhealth expensesin the lastyear.When

thepoor

come

under

economic

stress, theirform

of "insurance"is often eatingless or taking theirchildren out ofschool. For example, Jacoby

and

Skoufias (1997) find thatpoor

children leave school inbad

years.Rose

(1999) finds thatthegap

inmortality' ofgirlsrelative to

boys

ismuch

largerin droughtyears (but onlyforthe landless households,w^ho arenotable to sellland or

borrow

to weatherthecrisis).They

alsoare lesslikely to getmedicaltreatment for

themsehes

ortheirchildren: IntheUdaipur

sample, thosewho

were

sickinthelast

months and

didnotseektreatment(more

than half) cite lackofmoney

more

oftenthanany

otherreason(34 percent

of

thetimes).The

lackof insurancealsoleads thepoor

to under-investinrisky, butprofitable,technologies, such as

new

seeds(Morduch,

1991).The

weaknesses of

informal insurance should notreallybe a surprise. Ultimately,informal insurancerelies

on

the willingness ofthe fortunateto take care ofthose less favored,which

limits theamount

ofinsurance provided.Moreover,

informal socialnetworks

areoftennotwell-diversified.

They

tendto spreadrisk over householdswho

li\'e nearbyand have

similarincomes and

occupations, asGubert and Fafchamps

(2006)show

forthe Philippines.Unfortunately

govermnents

inthese countries are notveryeffective atprovidinginsurance either. For example, in

most

countries, thegovernment

issupposed

to providefreehealth careto thepoor.Yet, health care israrelyIree.

Govemm.ent

health-careproviders oftenillegally chargefor their

own

servicesand

formedicines inreality. Also, aswe

will see,thequality'ofcare in thepublic systemis so

low

thatthepoor

oftenend

up

visitingprivateproviders.

A

number

ofgovernments

provide aform

ofincome

insurance through safety-net"foodfor