ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Resuscitation

j o ur na l h o me p a g e:ww w . e l s e v i er . c o m / l o c a t e / r e s u s c i t a t i o n

European

Resuscitation

Council

Guidelines

for

Resuscitation

2015

Section

4.

Cardiac

arrest

in

special

circumstances

Anatolij

Truhláˇr

a,b,∗,

Charles

D.

Deakin

c,

Jasmeet

Soar

d,

Gamal

Eldin

Abbas

Khalifa

e,

Annette

Alfonzo

f,

Joost

J.L.M.

Bierens

g,

Guttorm

Brattebø

h,

Hermann

Brugger

i,

Joel

Dunning

j,

Silvija

Hunyadi-Antiˇcevi ´c

k,

Rudolph

W.

Koster

l,

David

J.

Lockey

m,w,

Carsten

Lott

n,

Peter

Paal

o,p,

Gavin

D.

Perkins

q,r,

Claudio

Sandroni

s,

Karl-Christian

Thies

t,

David

A.

Zideman

u,

Jerry

P.

Nolan

v,w,

on

behalf

of

the

Cardiac

arrest

in

special

circumstances

section

Collaborators

1aEmergencyMedicalServicesoftheHradecKrálovéRegion,HradecKrálové,CzechRepublic

bDepartmentofAnaesthesiologyandIntensiveCareMedicine,UniversityHospitalHradecKrálové,HradecKrálové,CzechRepublic

cCardiacAnaesthesiaandCardiacIntensiveCare,NIHRSouthamptonRespiratoryBiomedicalResearchUnit,SouthamptonUniversityHospitalNHSTrust,

Southampton,UK

dAnaesthesiaandIntensiveCareMedicine,SouthmeadHospital,NorthBristolNHSTrust,Bristol,UK eEmergencyandDisasterMedicine,SixOctoberUniversityHospital,Cairo,Egypt

fDepartmentsofRenalandInternalMedicine,VictoriaHospital,Kirkcaldy,Fife,UK gSocietytoRescuePeoplefromDrowning,Amsterdam,TheNetherlands

hBergenEmergencyMedicalServices,DepartmentofAnaesthesiaandIntensiveCare,HaukelandUniversityHospital,Bergen,Norway iEURACInstituteofMountainEmergencyMedicine,Bozen,Italy

jDepartmentofCardiothoracicSurgery,JamesCookUniversityHospital,Middlesbrough,UK kCenterforEmergencyMedicine,ClinicalHospitalCenterZagreb,Zagreb,Croatia lDepartmentofCardiology,AcademicMedicalCenter,Amsterdam,TheNetherlands

mIntensiveCareMedicineandAnaesthesia,SouthmeadHospital,NorthBristolNHSTrust,Bristol,UK nDepartmentofAnesthesiology,UniversityMedicalCenter,JohannesGutenberg-Universitaet,Mainz,Germany oBartsHeartCentre,StBartholomew’sHospital,BartsHealthNHSTrust,QueenMaryUniversityofLondon,London,UK pDepartmentofAnaesthesiologyandCriticalCareMedicine,UniversityHospitalInnsbruck,Austria

qWarwickMedicalSchool,UniversityofWarwick,Coventry,UK

rCriticalCareUnit,HeartofEnglandNHSFoundationTrust,Birmingham,UK

sDepartmentofAnaesthesiologyandIntensiveCare,CatholicUniversitySchoolofMedicine,Rome,Italy tBirminghamChildren’sHospital,Birmingham,UK

uDepartmentofAnaesthetics,ImperialCollegeHealthcareNHSTrust,London,UK vAnaesthesiaandIntensiveCareMedicine,RoyalUnitedHospital,Bath,UK wSchoolofClinicalSciences,UniversityofBristol,UK

Introduction

Irrespectiveofthecauseofcardiacarrest,earlyrecognitionand callingforhelp,includingappropriatemanagementofthe deteri-oratingpatient,earlydefibrillation,high-qualitycardiopulmonary resuscitation(CPR)withminimalinterruptionofchest compres-sionsandtreatmentofreversiblecauses,arethemostimportant interventions.

In certain conditions, however, advanced life support (ALS) guidelinesrequiremodification.Thefollowingguidelinesfor resus-citation in special circumstances are divided into three parts:

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:anatolij.truhlar@gmail.com(A.Truhláˇr).

1 ThemembersoftheCardiacarrestinspecialcircumstancessectionCollaborators

arelistedintheCollaboratorssection.

special causes, special environments and special patients. The firstpartcoverstreatmentofpotentiallyreversiblecausesof car-diacarrest,forwhich specifictreatmentexists,andwhichmust beidentified orexcluded duringanyresuscitation. For improv-ingrecallduringALS,thesearedividedintotwogroupsoffour, based upon theirinitialletter –either H or T– and arecalled the‘4Hsand4Ts’:Hypoxia;Hypo-/hyperkalaemiaandother elec-trolyte disorders; Hypo-/hyperthermia; Hypovolaemia; Tension pneumothorax;Tamponade(cardiac);Thrombosis(coronaryand pulmonary);Toxins(poisoning). Thesecondpartcoverscardiac arrestinspecial environments,whereuniversalguidelineshave tobemodifiedduetospecificlocationsorlocation-specificcauses ofcardiacarrest.Thethirdpartisfocusedonpatientswith spe-cificconditions,and thosewithcertainlong-termcomorbidities whereamodifiedapproachanddifferenttreatmentdecisionsmay benecessary.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.017

Summaryofchangessince2010Guidelines

ThemainchangesintheERCGuidelines2015incomparison withtheGuidelines20101aresummarisedbelow:

Specialcauses

• Survivalafteranasphyxia-inducedcardiacarrestisrareand sur-vivorsoftenhavesevereneurologicalimpairment.DuringCPR, earlyeffectiveventilationofthelungswithsupplementary oxy-genisessential.

• Ahighdegreeofclinicalsuspicionandaggressivetreatmentcan preventcardiacarrestfromelectrolyteabnormalities.Thenew algorithmprovidesclinicalguidancetoemergencytreatmentof life-threateninghyperkalaemia.

• Hypothermic patients without signs of cardiac instability (systolic blood pressure ≥90mmHg, absence of ventricular arrhythmiasorcoretemperature≥28◦C)canberewarmed exter-nallyusingminimallyinvasivetechniques(e.g.withwarmforced airandwarmintravenousfluid).Patientswithsignsofcardiac instabilityshouldbetransferreddirectlytoacentrecapableof extracorporeallifesupport(ECLS).

• Earlyrecognitionandimmediatetreatmentwithintramuscular adrenalineremains the mainstayof emergency treatmentfor anaphylaxis.

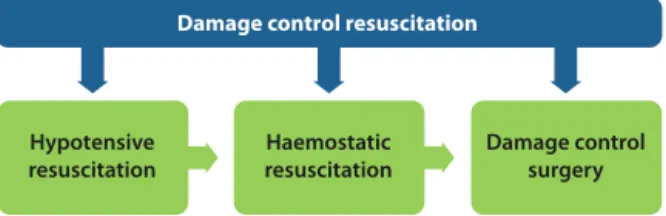

• Themortalityfromtraumaticcardiacarrest(TCA)isveryhigh. Themostcommoncauseofdeathishaemorrhage.Itisrecognised thatmostsurvivorsdonothavehypovolaemia,butinsteadhave otherreversiblecauses(hypoxia,tensionpneumothorax,cardiac tamponade)thatmustbeimmediatelytreated.Thenew treat-mentalgorithmforTCAwasdevelopedtoprioritisethesequence oflife-savingmeasures.Chestcompressionsshouldnotdelaythe treatmentofreversiblecauses.Cardiacarrestsofnon-traumatic originleadingtoasecondarytraumaticeventshouldbe recog-nisedandtreatedwithstandardalgorithms.

• Thereislimitedevidenceforrecommendingtheroutine trans-portofpatientswithcontinuingCPRafterout-of-hospitalcardiac arrest(OHCA)ofsuspectedcardiacorigin.Transportmaybe ben-eficialin selectedpatientswhere there is immediatehospital accessto thecatheterisation laboratoryand an infrastructure providing prehospital and in-hospital teams experienced in mechanicalorhaemodynamicsupportandpercutaneous coro-naryintervention(PCI)withongoingCPR.

• Recommendationsforadministrationoffibrinolyticswhen pul-monaryembolismisthesuspectedcauseofcardiacarrestremain unchanged.Routineuseofsurgicalembolectomyor mechani-calthrombectomywhenpulmonaryembolismisthesuspected cause of cardiac arrest is not recommended. Consider these methodsonlywhenthere isaknowndiagnosisofpulmonary embolism.

• Routineuseofgastriclavageforgastrointestinal decontamina-tioninpoisoningisnolongerrecommended.Reducedemphasis isplacedonhyperbaricoxygentherapyincarbonmonoxide poi-soning.

Specialenvironments

• Thespecialenvironmentssectionincludesrecommendationsfor treatmentofcardiacarrestoccurringinspecificlocations.These locationsarespecialisedhealthcarefacilities(e.g.operating the-atre,cardiac surgery, catheterisation laboratory, dialysis unit, dentalsurgery),commercialairplanesorairambulances,fieldof play,outsideenvironment(e.g.drowning,difficultterrain,high altitude,avalancheburial,lightningstrikeandelectricalinjuries) orthesceneofamasscasualtyincident.

• Patientsundergoingsurgicalproceduresinvolvinggeneral anaes-thesia,particularlyinemergencies,areatriskfromperioperative

cardiacarrest.Anewsectioncoversthecommoncausesand rel-evantmodificationtoresuscitativeproceduresinthisgroupof patients.

• Cardiacarrestfollowingmajorcardiacsurgeryisrelatively com-monintheimmediatepost-operativephase.Keytosuccessful resuscitationisrecognitionoftheneedtoperformemergency resternotomy,especially inthecontext oftamponadeor hae-morrhage,whereexternalchestcompressionsmaybeineffective. Resternotomyshouldbeperformedwithin5minifother inter-ventionshavefailed.

• Cardiacarrestfromshockablerhythms(VentricularFibrillation (VF) or pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia (pVT)) during car-diaccatheterisationshouldimmediatelybetreatedwithupto three stacked shocks beforestarting chest compressions. Use ofmechanicalchestcompressiondevicesduringangiographyis recommendedtoensure high-qualitychestcompressionsand reducetheradiation burdentopersonnel duringangiography withongoingCPR.

• Indentalsurgery,donotmovethepatientfromthedentalchair inordertostartCPR.Quicklyreclinethedentalchairintoa hor-izontalpositionandplaceastoolundertheheadofthechairto increaseitsstabilityduringCPR.

• Thein-flightuseofAEDsaboardcommercialairplanescanresult inupto50%survivaltohospitaldischarge.AEDsandappropriate CPRequipmentshouldbemandatoryonboardofall commer-cialaircraftinEurope,includingregionalandlow-costcarriers. Consideranover-the-headtechniqueofCPRifrestrictedaccess precludesaconventionalmethod,e.g.intheaisle.

• Theincidenceofcardiacarrestonboardhelicopteremergency medicalservices(HEMS)andairambulancesislow.Importance ofpre-flightpreparationanduseofmechanicalchest compres-siondevicesareemphasised.

• Suddenandunexpectedcollapseofanathleteonthefieldofplay islikelytobecardiacinoriginandrequiresrapidrecognitionand earlydefibrillation.

• Theduration of submersionis a key determinantofoutcome fromdrowning.Submersionexceeding10minisassociatedwith pooroutcome.Bystandersplayacriticalroleinearlyrescueand resuscitation.Resuscitationstrategiesforthoseinrespiratoryor cardiacarrestcontinuetoprioritiseoxygenationandventilation. • The chances of good outcome from cardiac arrest in diffi-cultterrainormountains maybereduced becauseof delayed access andprolonged transport. Thereis a recognisedrole of airrescueandavailabilityofAEDsinremotebutoften-visited locations.

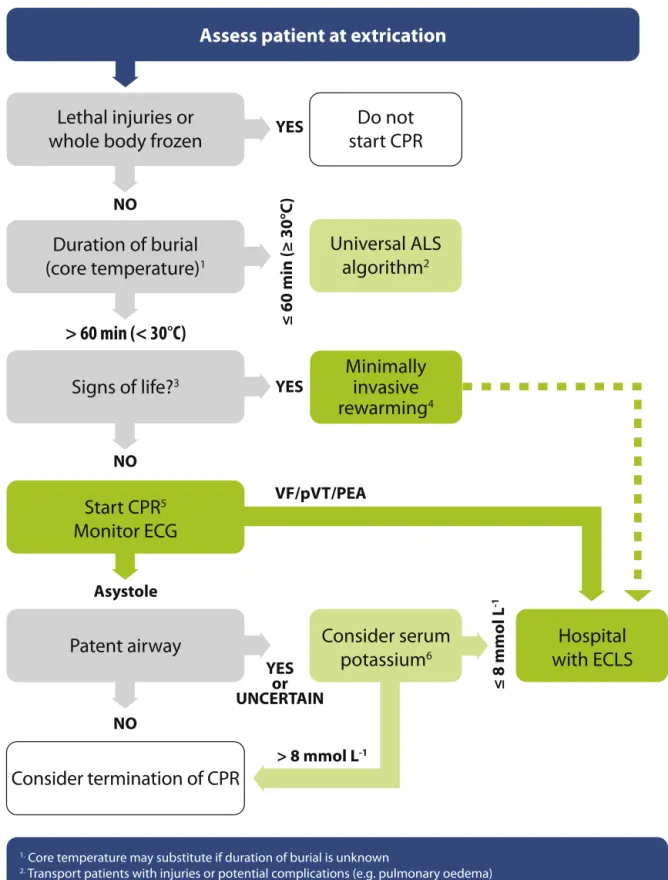

• The cut-off criteria for prolonged CPR and extracorporeal rewarming of avalanche victims in cardiac arrest are more stringenttoreducethenumberoffutilecasestreatedwith extra-corpoereallifesupport(ECLS).ECLSisindicatediftheduration ofburialis >60min(instead of>35min),coretemperatureat extricationis <30◦C (insteadof <32◦C),and serumpotassium athospitaladmissionis≤8mmolL−1(insteadof≤12mmolL−1); otherwisestandardguidelinesapply.

• SafetymeasuresareemphasisedwhenprovidingCPRtothe vic-timofanelectricalinjury.

• Recommendationsformanagementofmultiplevictimsshould preventdelayoftreatmentavailableforsalvageablevictims dur-ingmasscasualtyincidents(MCIs).Safetyatsceneisparamount. Atriagesystemshouldbeusedtoprioritisetreatmentand,ifthe numberofcasualtiesoverwhelmshealthcareresources,withhold CPRforthosewithoutsignsoflife.

Specialpatients

• The section on special patients gives guidance for CPR in patientswithseverecomorbidities(asthma,heartfailurewith

ventricular assist devices, neurological disease, obesity) and thosewithspecificphysiologicalconditions(pregnancy,elderly people).

• Thefirstlinetreatmentforacuteasthmaisinhaledbeta-2 ago-nistswhileintravenousbeta-2agonistsaresuggestedonlyfor thosepatientsinwhominhaledtherapycannotbeusedreliably. Inhaledmagnesiumisnolongerrecommended.

• Inpatientswithventricularassistdevices(VADs),confirmation ofcardiacarrestmaybedifficult.Ifduringthefirst10daysafter surgery,cardiacarrestdoesnotrespondtodefibrillation,perform resternotomyimmediately.

• PatientswithsubarachnoidhaemorrhagemayhaveECGchanges thatsuggestanacutecoronarysyndrome(ACS).Whethera com-putedtomography(CT)brainscanisdonebeforeoraftercoronary angiographywilldependonclinical judgementregarding the likelihoodofasubarachnoidhaemorrhageversusacutecoronary syndrome.

• Nochangestothesequenceofactionsarerecommendedin resus-citationofobesepatients,althoughdeliveryofeffectiveCPRmay bechallenging.Considerchangingrescuersmorefrequentlythan thestandard2-mininterval.Earlytrachealintubationbyan expe-riencedproviderisrecommended.

• Forthepregnantwomanincardiacarrest,high-qualityCPRwith manualuterinedisplacement,earlyALSanddeliveryofthefetus ifearlyreturnofspontaneouscirculation(ROSC)isnotachieved remainkeyinterventions.

A–SPECIALCAUSES Hypoxia

Introduction

Cardiacarrestcausedbypurehypoxaemiaisuncommon.Itis seenmorecommonlyasaconsequenceofasphyxia,whichaccounts formostofthenon-cardiaccausesofcardiacarrest.Therearemany causesof asphyxialcardiacarrest(Table4.1); althoughthere is usuallya combinationof hypoxaemiaand hypercarbia,it isthe hypoxaemiathatultimatelycausescardiacarrest.2

Pathophysiologicalmechanisms

Ifbreathingiscompletelypreventedbyairwayobstructionor apnoea, consciousness will be lost when oxygen saturation in thearterial blood reachesabout 60%. The time taken toreach thisconcentrationisdifficulttopredict,butislikelytobeofthe order 1–2min.3 Based onanimal experiments of cardiac arrest

causedbyasphyxia,pulselesselectricalactivity(PEA)willoccur in3–11min.Asystolewillensueseveralminuteslater.4In

compar-isonwithsimpleapnoea,theexaggeratedrespiratorymovements thatfrequentlyaccompanyairwayobstructionwillincrease oxy-genconsumption resultingin morerapid arterialbloodoxygen desaturationand a shorter time tocardiac arrest. Accordingto Table4.1

Causesofasphyxialcardiacarrest

Airwayobstruction:softtissues(coma),laryngospasm,aspiration Anaemia

Asthma Avalancheburial

Centralhypoventilation–brainorspinalcordinjury Chronicobstructivepulmonarydisease

Drowning Hanging Highaltitude

Impairedalveolarventilationfromneuromusculardisease Pneumonia

Tensionpneumothorax Trauma

Traumaticasphyxiaorcompressionasphyxia(e.g.crowdcrush)

Safar,completeairwayobstructionafterbreathingairwillresult

inPEAcardiacarrestin5–10min.2VFisrarelythefirstmonitored

rhythmafterasphyxialcardiacarrest–inoneofthelargestseriesof hanging-associatedout-of-hospitalcardiacarrests(OHCAs),from Melbourne,Australia,just7(0.5%)of1321patientswereinVF.5

Treatment

Treatingthecauseoftheasphyxia/hypoxaemiaisthehighest prioritybecausethisisapotentiallyreversiblecauseofthe car-diacarrest.Effectiveventilationwithsupplementaryoxygenisa particularpriorityinthesepatients.ThebetteroutcomesforOHCA victimsreceivingcompression-onlyCPR6isnotthecasefor

asphyx-ialcardiac arrests,which have much better survival rates with conventionalCPR.7FollowthestandardALSalgorithmwhen

resus-citatingthesepatients. Outcome

Survivalaftercardiacarrestfromasphyxiaisrareandmost sur-vivorssustainsevereneurologicalinjury.Offivepublishedseries thatincludedatotal of286patientswithcardiacarrest follow-ing hanging where CPR wasattempted (this wasattempted in onlyabout16%ofcases),therewerejustsix(2%)survivorswith afullrecovery;11othersurvivorsallhadseverepermanentbrain injury.5,8–11Inonethird(89;31%)ofthese286patients,rescuers

wereabletoachieveROSC–thuswhenCPRisattempted,ROSC is notuncommonbut subsequentneurologicallyintact survival israre.Thosewhoareunconsciousbuthavenotprogressedtoa cardiacarrestaremuchmorelikelytomakeagoodneurological recovery.11,12

Hypo-/hyperkalaemiaandotherelectrolytedisorders Introduction

Electrolyte abnormalities can cause cardiac arrhythmias or cardiacarrest.Life-threateningarrhythmias areassociatedmost commonlywithpotassiumdisorders,particularlyhyperkalaemia, and less commonly with disorders of serum calcium and magnesium.Consider electrolytedisturbancesin patientgroups atrisk–renalfailure,severeburns,cardiacfailureanddiabetes mellitus.

Theelectrolyte values for definitions havebeen chosenas a guidetoclinicaldecision-making.Theprecisevaluesthattrigger treatmentdecisionswilldependonthepatient’sclinicalcondition andrateofchangeofelectrolytevalues.Thereislittleorno evi-denceforthetreatmentofelectrolyteabnormalitiesduringcardiac arrest.Guidanceduringcardiacarrest isbasedonthestrategies usedinthenon-arrestpatient.

Preventionofelectrolytedisorders

Whenpossible,identifyandtreat life-threateningelectrolyte abnormalitiesbeforecardiacarrestoccurs.Monitorrenalfunction inpatientsatriskandavoidcombinationofdrugsthatmay exac-erbatehyperkalaemia.Preventrecurrenceofelectrolytedisorders byremovinganyprecipitatingfactors(e.g.drugs,diet).

Potassiumdisorders

Potassium homeostasis. Extracellularpotassium concentration is regulated tightly between 3.5 and 5.0mmolL−1. A large con-centration gradient normally exists between intracellular and extracellularfluidcompartments.Thispotassiumgradientacross cellmembranescontributestotheexcitabilityofnerveandmuscle cells,includingthemyocardium.Evaluationofserumpotassium musttakeintoconsiderationtheeffectsofchangesinserumpH. WhenserumpHdecreases(acidaemia),serumpotassiumincreases becausepotassiumshiftsfromthecellulartothevascularspace;a processthatisreversedwhenserumpHincreases(alkalaemia).

Hyperkalaemia. Thisisthemostcommonelectrolytedisorder asso-ciatedwithcardiacarrest.Itisusuallycausedbyimpairedexcretion bythekidneys,drugsorincreasedpotassiumrelease fromcells and metabolic acidosis. Hyperkalaemia occurs in up to 10% of hospitalisedpatients.13–15 Chronickidneydisease(CKD)is

com-moninthegeneralpopulationandtheincidenceofhyperkalaemia increasesfrom2to42%asglomerularfiltrationrate(GFR)drops from60to20mLmin−1.16 Patientswithend-stagerenaldisease

areparticularlysusceptible,particularlyfollowinganOHCA.17

Pro-longedhyperkalaemiaisanindependentriskfactorforin-hospital mortality.18 Acute hyperkalaemia is more likely than chronic

hyperkalaemia tocause life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias or cardiacarrest.

Definition. Thereisnouniversaldefinition.Wehavedefined hyperkalaemiaasa serumpotassiumconcentrationhigherthan 5.5mmolL−1; inpractice,hyperkalaemiais acontinuum.Asthe potassium concentration increases above this value the risk of adverse events increases and the need for urgent treatment increases.Severehyperkalaemiahasbeendefinedasaserum potas-siumconcentrationhigherthan6.5mmolL−1.

Causes. Themaincausesofhyperkalaemiaare:

• renalfailure(i.e.acutekidneyinjuryorchronickidneydisease); • drugs (e.g. angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARB), potassium-sparing diuretics,non-steroidalanti-inflammatorydrugs,beta-blockers, trimethoprim);

• tissuebreakdown(e.g.rhabdomyolysis,tumourlysis, haemoly-sis);

• metabolicacidosis(e.g.renalfailure,diabeticketoacidosis); • endocrinedisorders(e.g.Addison’sdisease);

• diet(maybesolecauseinpatientswithadvancedchronickidney disease)and

• spurious–pseudo-hyperkalaemia(suspectincaseswithnormal renalfunction,normalECGand/orhistoryofhaematological dis-order).Pseudo-hyperkalaemiadescribesthefindingofaraised serum (clotted blood) K+ value concurrently with a normal plasma(non-clottedblood)potassiumvalue.Theclottingprocess releasesK+fromcellsandplatelets,whichincreasestheserum K+concentrationbyanaverageof0.4mmol/L.Themostcommon causeofpseudo-hyperkalaemiaisaprolongedtransittimetothe laboratoryorpoorstorageconditions.19,20

The risk of hyperkalaemia is even greater when there is a combinationoffactorssuchastheconcomitantuseof angiotensin-convertingenzymeinhibitorsorangiotensinIIreceptorblockers andpotassium-sparingdiuretics.

Recognition of hyperkalaemia. Exclude hyperkalaemia in all patientswithanarrhythmiaorcardiacarrest.Patientsmaypresent withweaknessprogressing toflaccid paralysis,paraesthesia,or depresseddeeptendonreflexes.Alternatively,theclinicalpicture can be overshadowed by the primary illness causing hyper-kalaemia.The firstindicator ofhyperkalaemia may alsobethe presenceofECGabnormalities,arrhythmias,orcardiacarrest.The useofabloodgasanalysertomeasurepotassiumcanreducedelays inrecognition.21,22

TheeffectofhyperkalaemiaontheECGdependsonthe abso-luteserumpotassiumaswellastherateofincrease.23Thereported

frequencyofECGchangesinseverehyperkalaemiaisvariable,but mostpatientsappeartoshowECGabnormalitiesataserum potas-siumconcentrationhigherthan6.7mmolL−1.23,24Thepresenceof

ECGchangesstronglycorrelateswithmortality.25Insomecases,

theECG maybenormal orshowatypical changes includingST elevation.

TheECG changes associated withhyperkalaemiaare usually progressiveandinclude:

• firstdegreeheartblock(prolongedPRinterval>0.2s); • flattenedorabsentPwaves;

• tall,peaked(tented)Twaves(i.e.TwavelargerthanRwavein morethan1lead);

• ST-segmentdepression;

• S&Twavemerging(sinewavepattern); • widenedQRS(>0.12s);

• ventriculartachycardia; • bradycardia;

• cardiacarrest(PEA,VF/pVT,asystole).

Treatment of hyperkalaemia. There are five key treatment strategiesforhyperkalaemia22:

• cardiacprotection;

• shiftingpotassiumintocells; • removingpotassiumfromthebody;

• monitoringserumpotassiumandbloodglucose; • preventionofrecurrence.

Whenhyperkalaemiaisstronglysuspected,e.g.inthepresence ofECGchanges,startlife-savingtreatmentevenbeforelaboratory resultsare available. The treatmentstrategy for hyperkalaemia hasbeenreviewedextensively.13,22,26Followthehyperkalaemia

emergency treatment algorithm (Fig. 4.1).22 Avoid salbutamol

monotherapy,whichmaybeineffective.Thereisinsufficient evi-dencetosupporttheuseofsodiumbicarbonatetodecreaseserum potassium.Consider theneedforearlyspecialistorcriticalcare referral.

Themainrisksassociatedwithtreatmentofhyperkalaemiaare: • Hypoglycaemia followinginsulin-glucose administration (usu-allyoccurswithin1–3hoftreatment,butmayoccurupto6h afterinfusion).27Monitorbloodglucoseandtreathypoglycaemia

promptly.

• Tissuenecrosissecondarytoextravasationofintravenous cal-ciumsalts.Ensuresecurevascularaccesspriortoadministration. • Intestinal necrosis or obstruction following use of potassium exchangeresins.Avoidprolongeduseofresinsandgivelaxative. • Reboundhyperkalaemiaaftertheeffectofdrugtreatmenthas wornoff(i.e.within4–6h).Continuetomonitorserumpotassium foraminimumof24hafteranepisode.

Patientnotincardiacarrest Assesspatient:

• UsesystematicABCDEapproachandcorrectanyabnormalities, obtainIVaccess.

• Checkserumpotassium. • RecordanECG.

Monitorcardiacrhythminpatientswithseverehyperkalaemia. Treatmentisdeterminedaccordingtoseverityofhyperkalaemia. Approximate values are provided to guide treatment. Follow hyperkalaemiaemergencytreatmentalgorithm(Fig.4.1).

Mildelevation(5.5–5.9mmolL−1).

• Addresscauseofhyperkalaemiatocorrectandavoidfurtherrise inserumpotassium(e.g.drugs,diet).

• If treatment is indicated, remove potassium from the body: potassiumexchangeresins-calciumresonium15–30g,orsodium polystyrenesulfonate(Kayexalate)15–30g,giveneitherorallyor byretentionenema/PR(perrectum)(onsetin>4h).

Moderateelevation(6.0–6.4mmolL−1)withoutECGchanges. • Shift potassium intracellularly with glucose/insulin: 10 units

short-actinginsulinand25gglucoseIVover15–30min(onset in15–30min;maximaleffectat30–60min;durationofaction 4–6h;monitorbloodglucose).

• Removepotassiumfromthebody(seeabove;considerdialysis guidedbyclinicalsetting).

Fig.4.1.Emergencytreatmentofhyperkalaemia.PRperrectum;ECGelectrocardiogram;VTventriculartachycardia. ReproducedwithpermissionfromRenalAssociationandResuscitationCouncil(UK).

Severeelevation(≥6.5mmolL−1)withoutECGchanges. • Seekexperthelp.

• Giveglucose/insulin(seeabove).

• Givesalbutamol10–20mgnebulised(onsetin15–30min; dura-tionofaction4–6h).

• Removepotassiumfromthebody(considerdialysis). Severeelevation(≥6.5mmolL−1)withtoxicECGchanges. • Seekexperthelp.

• Protect the heart with calcium chloride: 10mL 10% cal-cium chloride IV over 2–5min to antagonise the toxic effects of hyperkalaemia at the myocardial cell mem-brane. This protects the heart by reducing the risk of VF/pVT but does not lower serum potassium (onset in 1–3min).

• Useshiftingagents(glucose/insulinandsalbutamol).

• Removepotassiumfromthebody(considerdialysisatoutsetor ifrefractorytomedicaltreatment).

Modificationstocardiopulmonaryresuscitation. Thefollowing modificationstostandardALSguidelinesarerecommendedinthe presenceofseverehyperkalaemia:

• Confirmhyperkalaemiausingabloodgasanalyserifavailable. • Protecttheheart:give10mLcalciumchloride10%IVbyrapid

bolusinjection.

• Shiftpotassiumintocells:Giveglucose/insulin:10units short-actinginsulin and 25gglucoseIV byrapid injection.Monitor bloodglucose.

• Givesodiumbicarbonate:50mmolIVbyrapidinjection(ifsevere acidosisorrenalfailure).

• Remove potassium from body: Consider dialysis for hyper-kalaemiccardiacarrestresistanttomedicaltreatment.Several dialysismodalitieshavebeenusedsafelyandeffectivelyin car-diacarrest,butthismayonlybeavailableinspecialistcentres.28

Consideruseofamechanicalchestcompressiondeviceif pro-longedCPRisneeded.

Indications for dialysis. The main indications for dialysis in patientswithhyperkalaemiaare:

• severe life-threatening hyperkalaemia with or without ECG changesorarrhythmia;

• hyperkalaemiaresistanttomedicaltreatment; • end-stagerenaldisease;

• oliguricacutekidneyinjury(<400mLday−1urineoutput); • markedtissuebreakdown(e.g.rhabdomyolysis).

Specialconsiderationsformanagement ofcardiacarrestin a dialysisunitareaddressedinthesectionSpecialenvironments(see cardiacarrestinadialysisunit).

Hypokalaemia. Hypokalaemiaisthemostcommonelectrolyte dis-orderinclinicalpractice.29Itisseeninupto20%ofhospitalised

patients.30Hypokalaemiaincreasestheincidenceofarrhythmias

andsuddencardiacdeath(SCD).31Theriskisincreasedinpatients

withpre-existingheartdiseaseandinthosetreatedwithdigoxin. Definition. Hypokalaemiaisdefinedasaserumpotassiumlevel <3.5mmolL−1.Severehypokalaemiaisdefinedasaserum potas-siumlevel<2.5mmolL−1andmaybeassociatedwithsymptoms.

Causes. Themaincausesofhypokalaemiainclude: • gastrointestinalloss(e.g.diarrhoea);

• drugs(e.g.diuretics,laxatives,steroids);

• renallosses(e.g.renaltubulardisorders,diabetesinsipidus, dial-ysis);

• endocrinedisorders (e.g.Cushing’s syndrome, hyperaldostero-nism);

• metabolicalkalosis; • magnesiumdepletion; • poordietaryintake.

Treatmentstrategiesusedforhyperkalaemiamayalsoinduce hypokalaemia.

Recognitionofhypokalaemia. Excludehypokalaemiainevery patientwithanarrhythmiaorcardiacarrest.Indialysispatients, hypokalaemiamayoccurattheendofahaemodialysissessionor duringtreatmentwithperitonealdialysis.

Asserumpotassium concentrationdecreases,thenervesand muscles are predominantly affected,causing fatigue, weakness, leg cramps, constipation. In severe cases (serum potassium <2.5mmolL−1),rhabdomyolysis,ascendingparalysisand respira-torydifficultiesmayoccur.

ECGfeaturesofhypokalaemiaare: • Uwaves;

• Twaveflattening; • STsegmentchanges;

• arrhythmias,especiallyifpatientistakingdigoxin; • cardiacarrest(PEA,VF/pVT,asystole).

Treatment. This depends on the severity of hypokalaemia and thepresenceof symptomsand ECG abnormalities.Gradual replacementofpotassiumispreferable,butinanemergency, intra-venous potassium is required. The maximumrecommended IV doseofpotassiumis 20mmolh−1,but morerapidinfusion(e.g. 2mmolmin−1for10min,followedby10mmolover5–10min)is indicatedforunstablearrhythmiaswhencardiacarrestis immi-nent.ContinuousECGmonitoringisessentialduringIVinfusion andthedoseshouldbetitratedafterrepeatedsamplingofserum potassiumlevels.

Manypatientswhoarepotassiumdeficientarealsodeficient inmagnesium.Magnesiumisimportantforpotassiumuptakeand forthemaintenanceofintracellularpotassiumvalues,particularly inthemyocardium.Repletionofmagnesiumstoreswillfacilitate morerapid correctionofhypokalaemiaandis recommendedin severecasesofhypokalaemia.32

Calciumandmagnesiumdisorders

Therecognitionandmanagementofcalciumandmagnesium disordersissummarisedinTable4.2.

Hypo-/hyperthermia Accidentalhypothermia

Definition. Every year approximately 1500 people die of pri-maryaccidental hypothermia intheUnitedStates.33 Accidental

hypothermiaisdefinedasaninvoluntarydropofthebodycore temperature<35◦C.TheSwissstagingsystemisusedtoestimate coretemperatureatthescene.Itsstagesarebasedonclinicalsigns, whichroughlycorrelatewiththecoretemperature:

• hypothermia I; mild hypothermia (conscious, shivering, core temperature35–32◦C);

• hypothermiaII;moderatehypothermia(impairedconsciousness withoutshivering,coretemperature32–28◦C);

• hypothermiaIII;severehypothermia(unconscious,vitalssigns present,coretemperature28–24◦C);

• hypothermiaIV;cardiacarrestorlowflowstate(noorminimal vitalsigns,coretemperature<24◦C);

• hypothermiaV;deathduetoirreversiblehypothermia(core tem-perature<13.7◦C).34

Diagnosis. Hypothermiaisdiagnosed inanypatientwitha core temperature<35◦C,orwheremeasurementunavailable,ahistory of exposuretocold, orwhen thetrunkfeels cold.33 Accidental

hypothermiamaybeunder-diagnosedincountrieswitha temper-ateclimate.Whenthermoregulationisimpaired,forexample,in theelderlyandveryyoung,hypothermiamayfollowamildinsult. Theriskofhypothermiaisincreasedbyalcoholordrugingestion, exhaustion, illness,injury or neglectespecially whenthere is a decreaseinthelevelofconsciousness.

Alow-readingthermometerisneededtomeasurethecore tem-peratureandconfirmthediagnosis.Thecoretemperatureinthe lower third of the oesophagus correlates wellwithheart tem-perature. Tympanic measurement usinga thermistor technique isareliablealternativebutmaybeconsiderablylowerthancore temperature if the environment is very cold, the probe is not wellinsulated,ortheexternalauditorycanalisfilledwithsnow orwater35,36Widelyavailabletympanicthermometersbasedon

infraredtechniquedonotsealtheearcanalandarenotdesignedfor lowcoretemperaturereadings.37Thein-hospitalcoretemperature

measurement site shouldbethesamethroughoutresuscitation andrewarming.Bladderandrectaltemperatureslagbehindcore temperature;38,39 for this reason, measurement of bladder and

Table4.2

Calciumandmagnesiumdisorderswithassociatedclinicalpresentation,ECGmanifestationsandrecommendedtreatment

Disorder Causes Presentation ECG Treatment

Hypercalcaemia

Calcium>2.6mmolL−1 Primaryortertiary

hyperparathyroidism Malignancy Sarcoidosis Drugs Confusion Weakness Abdominalpain Hypotension Arrhythmias Cardiacarrest ShortQTinterval ProlongedQRSinterval FlatTwaves AVblock Cardiacarrest FluidreplacementIV Furosemide1mgkg−1IV Hydrocortisone200–300mgIV Pamidronate30–90mgIV Treatunderlyingcause

Hypocalcaemia

Calcium<2.1mmolL−1 Chronicrenalfailure Acutepancreatitis Calciumchannelblocker overdose

Toxicshocksyndrome Rhabdomyolysis Tumourlysissyndrome

Paraesthesia Tetany Seizures AV-block Cardiacarrest ProlongedQTinterval Twaveinversion Heartblock Cardiacarrest Calciumchloride10%10–40mL Magnesiumsulphate50% 4–8mmol(ifnecessary)

Hypermagnesaemia

Magnesium>1.1mmolL−1 Renalfailure

Iatrogenic Confusion Weakness Respiratorydepression AV-block Cardiacarrest ProlongedPRandQT intervals Twavepeaking AVblock Cardiacarrest

Considertreatmentwhen magnesium>1.75mmolL−1

Calciumchloride10%5–10mL repeatedifnecessary Ventilatorysupportifnecessary Salinediuresis–0.9%salinewith furosemide1mgkg−1IV

Haemodialysis Hypomagnesaemia

Magnesium<0.6mmolL−1 GIloss

Polyuria Starvation Alcoholism Malabsorption Tremor Ataxia Nystagmus Seizures Arrhythmias–torsade depointes Cardiacarrest ProlongedPRandQT intervals ST-segmentdepression T-waveinversion FlattenedPwaves IncreasedQRSduration Torsadedepointes Severeorsymptomatic:2g50% magnesiumsulphate(4mL; 8mmol)IVover15min Torsadedepointes:2g50% magnesiumsulphate(4mL; 8mmol)IVover1–2min Seizure:2g50%magnesium sulphate(4mL;8mmol)IVover 10min

rectaltemperaturehasbeende-emphasisedinpatientswithsevere

hypothermia.

Decisiontoresuscitate. Coolingofthehumanbodydecreases

cel-lular oxygen consumption by about 6% per 1◦C decrease in

coretemperature.40At28◦C,oxygenconsumptionisreducedby

approximately50%andat22◦Cbyapproximately75%.At18◦Cthe braincantoleratecardiacarrestforupto10timeslongerthanat 37◦C.Thisresultsinhypothermiaexertingaprotectiveeffectonthe brainandheart,41andintactneurologicalrecoverymaybepossible

evenafterprolongedcardiacarrestifdeephypothermiadevelops beforeasphyxia.

Bewareofdiagnosingdeathinahypothermicpatientbecause hypothermia itself may produce a very slow, small-volume, irregular pulse and unrecordable blood pressure. In a deeply hypothermicpatient(hypothermiaIV)signsoflifemaybeso mini-malthatitiseasytooverlookthem.Therefore,lookforsignsoflife foratleast1minanduseanECGmonitortodetectanyelectrical cardiacactivity.Neurologicallyintactsurvivalhasbeenreported afterhypothermiccardiacarrestwithacoretemperatureaslowas 13.7◦C42andCPRforaslongassixandahalfhours.43

IntermittentCPR,asrescueallows,mayalsobeofbenefit.44If

continuousCPRcannotbedelivered,apatientwithhypothermic cardiacarrestandacoretemperature<28◦C(orunknown),should receive5minofCPR,alternatingwithperiods≤5minwithoutCPR. Patientswithacoretemperature<20◦C,shouldreceive5minof CPR,alternatingwithperiods≤10minwithoutCPR.45

Intheprehospitalsetting,resuscitationshouldbewithheldin hypothermicpatientsonlyifthecauseofcardiacarrestisclearly attributabletoalethalinjury,fatalillness,prolongedasphyxia,or ifthechestisincompressible.46Inallotherhypothermicpatients,

thetraditionalguidingprinciplethat‘nooneisdeaduntilwarm anddead’shouldbeconsidered.Inremoteareas,the impracticali-tiesofachievingrewarminghavetobeconsidered.Inthehospital settinginvolveseniordoctorsanduseclinicaljudgementto deter-minewhentostopresuscitatingahypothermicvictimincardiac arrest.

Modificationstocardiopulmonaryresuscitation

• Donotdelaycarefultrachealintubationwhenitisindicated.The advantagesofadequateoxygenationandprotectionfrom aspi-rationoutweightheminimalriskoftriggeringVFbyperforming trachealintubation.47

• Checkforsignsoflifeforupto1min.Palpateacentralarteryand assessthecardiacrhythm(ifECGmonitoravailable). Echocardi-ography,near-infraredspectroscopyorultrasoundwithDoppler maybeusedtoestablishwhetherthereis(anadequate)cardiac outputorperipheralbloodflow.48,49Ifthereisanydoubt,start

CPRimmediately.

• Hypothermiacancausestiffnessofthechestwall,making ven-tilationsand chestcompressionsdifficult.Considertheuseof mechanicalchestcompressiondevices.50

• OnceCPRisunderway,confirmhypothermiawithalow-reading thermometer.

• The hypothermic heart may be unresponsive to cardioac-tivedrugs,attemptedelectricalpacinganddefibrillation.Drug metabolismisslowed,leadingtopotentiallytoxicplasma con-centrationsofanydruggiven.51 Theevidencefor theefficacy

of drugs in severe hypothermia is limited and based mainly onanimalstudies.Forinstance,inseverehypothermiccardiac arrest,theefficacyofamiodaroneisreduced.52Adrenalinemay

survival.53,54Vasopressorsmayalsoincreasethechancesof

suc-cessfuldefibrillation,butwithacoretemperature<30◦C,sinus rhythmoften degradesbackintoVF.Given that defibrillation andadrenalinemayinducemyocardialinjury, itisreasonable towithholdadrenaline,other CPRdrugs andshocksuntilthe patienthasbeenwarmedtoacoretemperature≥30◦C.Once 30◦Chasbeenreached,theintervalsbetweendrugdosesshould bedoubledwhen compared to normothermia(i.e.adrenaline every6–10min).Asnormothermia(≥35◦C)isapproached,use standarddrugprotocols.

Treatmentof arrhythmias. As coretemperature decreases,sinus bradycardia tendstogive way toatrial fibrillationfollowed by VFand finallyasystole.55,56 Arrhythmias otherthan VFtendto

revertspontaneouslyascoretemperatureincreases,andusually donotrequireimmediatetreatment.Bradycardiaisphysiologicalin severehypothermia.Cardiacpacingisnotindicatedunless brady-cardiaassociatedwithhaemodynamiccompromisepersistsafter rewarming.Thetemperatureatwhichdefibrillationshouldfirstly beattempted,andhowoftenitshouldbeattemptedintheseverely hypothermicpatient,hasnotbeenestablished.IfVFisdetected, defibrillateaccordingtostandardprotocols.IfVFpersistsafterthree shocks,delayfurtherattemptsuntilcoretemperatureis≥30◦C.57

CPRandrewarmingmayhavetobecontinuedforseveralhoursto facilitatesuccessfuldefibrillation.

Insulation. Generalmeasuresforallvictimsincluderemovalfrom thecoldenvironment, preventionof furtherheatlossandrapid transfertohospital.58Inthefield,apatientwithmoderateorsevere

hypothermia(hypothermia≥II)shouldbeimmobilisedand han-dledcarefully,oxygenatedadequately,monitored(includingECG andcoretemperature),andthewholebodydriedandinsulated.51

Removewetclotheswhileminimisingexcessivemovementof thevictim. Removalof wetclothing oruseof a vapour barrier seemstobeequallyeffectivetolimitheatloss.59Conscious

vic-tims(hypothermiaI)canmobiliseasexerciserewarmsaperson morerapidlythanshivering.60Patientswillcontinuecoolingafter

removalfromacoldenvironment(i.e.afterdrop),whichmayresult inalife-threateningdecreaseincoretemperaturetriggeringa car-diacarrestduringtransport(i.e.‘rescuedeath’).Prehospitally,avoid prolongedinvestigationsandtreatment,asfurtherheatlossis diffi-culttoprevent.Patientswhostopshivering(e.g.hypothermiaII–IV, andsedatedoranaesthetisedpatients)willcoolfaster.

Prehospitalrewarming. Rewarmingmaybepassive,activeexternal, oractiveinternal.InhypothermiaIpassiverewarmingis appropri-ateaspatientsarestillabletoshiver.Passiverewarmingisbest achievedbyfullbodyinsulationwithwoolblankets,aluminium foil,capandawarmenvironment.InhypothermiaII–IVthe appli-cationofchemicalheatpackstothetrunkhasbeenrecommended. Inconsciouspatientswhoareabletoshiver,thisimprovesthermal comfortbutdoesnotspeedrewarming.61Ifthepatientis

uncon-sciousandtheairwayisnotsecured,arrangetheinsulationaround thepatientlyinginarecovery(lateraldecubitus)position. Rewarm-inginthefieldwithheatedintravenousfluidsandwarmhumidified gasesisnotfeasible.51Intensiveactiverewarmingmustnotdelay

transport toa hospital where advanced rewarming techniques, continuousmonitoringandobservationareavailable.

Transport. Transport patients with hypothermia stage I to the nearesthospital.InhypothermiastageII–IV,signsofprehospital cardiacinstability(i.e.systolicbloodpressure<90mmHg, ventri-culararrhythmia,coretemperature<28◦C)shoulddeterminethe choiceofadmittinghospital.Ifanysignsofcardiacinstabilityare present,transportthepatienttoanECLScentre,contactingthem wellinadvancetoensurethatthehospitalcanacceptthepatient

forextracorporealrewarming.InhypothermiaV,reasonsfor with-holdingorterminatingCPRshouldbeinvestigated(e.g.obvious signsofirreversibledeath,validDNAR,conditionsunsafefor res-cuer,avalancheburial≥60minandairwaypackedwithsnowand asystole).Intheabsenceofanyofthesesigns,startCPRandtransfer thepatienttoanECLScentre.

In-hospitalrewarming. Unless thepatient goesinto VF, rewarm using active external methods (i.e. with forced warm air) and minimallyinvasivelymethods(i.e.withwarmIVinfusions).With acoretemperature<32◦C andpotassium <8mmolL−1,consider ECLSrewarming.33MostECLSrewarmingshavebeenperformed

usingcardiopulmonarybypass, butmore recently,veno-arterial extracorporealmembraneoxygenation(VA-ECMO)hasbecomethe preferredmethodduetoitsrapidavailability,theneedforless anti-coagulation,andthepotentialtoprolongcardiorespiratorysupport afterrewarming.

IfanECLScentreisnotavailable,rewarmingmaybeattempted inhospitalusingadedicatedteamandacombinationofexternal andinternalrewarming techniques(e.g.forcedwarmair,warm infusions,forcedperitoneallavage).62

Continuous haemodynamic monitoring and warm IV fluids areessential.Patientswillrequirelargevolumesoffluidsduring rewarming,asvasodilationcausesexpansionoftheintravascular space.Avoidhyperthermiaduringandafterrewarming.OnceROSC hasbeenachievedusestandardpost-resuscitationcare.

Hyperthermia

Introduction. Hyperthermiaoccurswhenthebody’sabilityto ther-moregulate fails and core temperature exceeds that normally maintainedby homeostaticmechanisms.Hyperthermiamay be exogenous,causedbyenvironmentalconditions,orsecondaryto endogenousheatproduction.

Environment-relatedhyperthermiaoccurswhereheat,usually intheformofradiantenergy,isabsorbedbythebodyataratefaster thancanbelostbythermoregulatorymechanisms.Hyperthermia isacontinuumofheat-relatedconditions,startingwithheatstress, progressingtoheatexhaustion,thentoheatstrokeandfinallyto multipleorgandysfunctionandcardiacarrest.63

Malignant hyperthermia is a rare disorder of skeletal mus-clecalciumhomeostasischaracterisedbymusclecontractureand life-threateninghypermetaboliccrisisfollowingexposureof genet-ically predisposed individuals to halogenated anaesthetics and depolarisingmusclerelaxants.64,65

Heatexhaustion

Definition. Heatexhaustion isa non-life-threatening clinical syndromeofweakness,malaise,nausea,syncope,andother non-specificsymptomscausedbyheatexposure.Thermoregulationis notimpaired.Heatexhaustioniscausedbywaterandelectrolyte imbalanceduetoheatexposure,withorwithoutexertion.Rarely, severeheatexhaustionafterphysicalexertionmaybecomplicated byrhabdomyolysis,myoglobinuria,acuterenalfailure,and dissem-inatedintravascularcoagulation(DIC).

Symptoms. Symptomsareoftenvague,andpatientsmaynot realisethatheatisthecause.Symptomsmayincludeweakness, dizziness,headache,nausea,andsometimesvomiting.Syncopedue tostandingforlongperiodsintheheat(heatsyncope)iscommon andmaymimiccardiovasculardisorders.Onexamination,patients appeartiredandareusuallysweatyandtachycardic.Mentalstatus istypicallynormal,unlikeinheatstroke.Temperatureisusually normaland,whenelevated,usuallydoesnotexceed40◦C.

Diagnosis. Diagnosisisclinicalandrequiresexclusionofother possible causes (e.g. hypoglycaemia, acute coronary syndrome, infections).Laboratorytestingisrequiredonlyifneededtorule outotherdisorders.

Treatment

Fluidsandelectrolytereplacement. Treatmentinvolves remov-ingpatientstoacoolenvironment,lyingthemflat,andgivingIV fluidsandelectrolytereplacementtherapy;oralrehydrationmay notbeeffectiveinrapidlyreplacingelectrolytes,butmaybeamore practicaltreatment.Rateandvolumeofrehydrationareguidedby age,underlyingdisorders, andclinicalresponse.Replacementof 1–2Lcrystalloidsat500mLh−1 isoftenadequate.External cool-ingmeasuresareusuallynotrequired.Considerexternalcoolingin patientswithacoretemperatureof≥40◦C.

Heatstroke

Definition. Heat stroke (HS) is defined as hyperthermia accompaniedbya systemic inflammatory response witha core temperature>40◦C,accompaniedbymentalstatechangeand vary-inglevelsoforgandysfunction.63

TherearetwoformsofHS:

1.Classic(non-exertional)heatstroke(CHS)occursduringhigh environmentaltemperaturesandofteneffectstheelderlyduring heatwaves.66

2.Exertionalheat stroke (EHS) occurs during strenuous physi-calexercisein highenvironmentaltemperaturesand/orhigh humidityandusuallyeffectshealthyyoungadults.67

Mortalityfromheatstrokerangesbetween10and50%.68

Predisposing factors. The elderly are at increased risk for heat-related illness because of underlying illness, medication use, decliningthermoregulatorymechanisms and limited social support.Thereareseveralriskfactors:lackofacclimatisation, dehy-dration,obesity, alcohol,cardiovascular disease,skinconditions (psoriasis, eczema, scleroderma, burn, cystic fibrosis), hyper-thyroidism, phaeochromocytoma and drugs (anticholinergics, diamorphine, cocaine, amphetamine, phenothiazines, sympath-omimetics,calciumchannelblockers,beta-blockers).

Symptoms. Heat strokecan resembleseptic shockand may becausedby similarmechanisms.69 Asinglecentre case series

reported14ICUdeathsin22heatstrokepatientsadmittedtoICU withmultipleorganfailure.70Featuresincluded:

• coretemperature≥40◦C;

• hot,dryskin(sweatingpresentinabout50%ofcasesofexertional heatstroke);

• earlysignsandsymptoms(e.g.extremefatigue,headache, faint-ing,facialflushing,vomitinganddiarrhoea);

• cardiovascular dysfunction including arrhythmias and hypotension71;

• respiratorydysfunctionincludingacuterespiratorydistress syn-drome(ARDS)72;

• central nervous system dysfunction including seizures and coma73;

• liverandrenalfailure74;

• coagulopathy; • rhabdomyolysis.75

Otherclinicalconditionspresentingwithincreasedcore tem-perature need to be considered, including drug toxicity, drug withdrawalsyndrome,serotoninsyndrome,neurolepticmalignant syndrome,sepsis,centralnervoussysteminfection,endocrine dis-orders(e.g.thyroidstorm,phaeochromocytoma).

Treatment. Themainstayoftreatmentis supportivetherapy andrapidlycoolingthepatient.76–78Startcoolinginthe

prehospi-talsettingifpossible.Aimtorapidlyreducethecoretemperature toapproximately39◦C.Patientswithsevereheatstrokeneedto bemanagedinanICUenvironment.Largevolumesoffluidsand correctionofelectrolyteabnormalitiesmayberequired(see hypo-/hyperkalaemiaandotherelectrolytedisorders).

Cooling techniques. Several cooling methods have been described, but there are few formal trials to determine which isoptimal. Simple coolingtechniquesinclude drinkingcold flu-ids,fanningthecompletelyundressedpatientandsprayingtepid wateronthepatient.Icepacksoverareaswheretherearelarge superficialbloodvessels(axillae,groins,neck)mayalsobeuseful. Surfacecoolingmethodsmaycauseshivering.Incooperative sta-blepatients,immersionincoldwatercanbeeffective79;however,

thismaycauseperipheralvasoconstriction,shuntbloodawayfrom theperipheryandreduceheatdissipation.Immersionisalsonot practicalinthesickestpatients.

Furthertechniquestocoolpatientswithhyperthermiaare sim-ilar to those used for targeted temperature management after cardiacarrest(seepostresuscitationcare).80Coldintravenous

flu-idswilldecreasebodytemperature.Gastric,peritoneal,81pleural

orbladderlavagewithcoldwaterwilllowerthecoretemperature. IntravascularcoolingtechniquesincludetheuseofcoldIVfluids,82

intravascularcoolingcatheters83,84andextracorporealcircuits,85

e.g.continuousveno-venoushaemofiltrationorcardiopulmonary bypass.

Pharmacologicaltreatment. Therearenospecificdrugtherapies inheatstrokethatlowercoretemperature.Thereisnogood evi-dencethatantipyretics(e.g.non-steroidalanti-inflammatorydrugs orparacetamol)areeffectiveinheatstroke.Diazepammaybe use-fultotreatseizuresandfacilitatecooling.86Dantrolenehasnotbeen

showntobebeneficial.87–89

Malignanthyperthermia

Malignanthyperthermiaisalife-threateninggeneticsensitivity ofskeletalmusclestohalogenatedvolatileanaestheticsand depo-larisingneuromuscularblockingdrugs,occurringduringorafter anaesthesia.90Stoptriggeringagents immediately;giveoxygen,

correctacidosisandelectrolyteabnormalities.Startactivecooling andgivedantrolene.91

Other drugs such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘ecstasy’) and amphetamines also cause a condition similartomalignanthyperthermiaandtheuseofdantrolenemay bebeneficial.92

Modifications to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. There are no specificstudiesofcardiacarrestinhyperthermia.Ifcardiacarrest occurs,followstandardguidelinesandcontinuecoolingthepatient. Use the same cooling techniques as for targeted temperature managementaftercardiacarrest(seeSection5Post-resuscitation care).80Attemptdefibrillationusingstandardenergylevels.Animal

studiessuggesttheprognosisispoorcomparedwithnormothermic cardiacarrest.93,94Theriskofunfavourableneurologicaloutcome

increasesby2.26(oddsratio)foreachdegreeofbodytemperature >37◦C.95

Hypovolaemia Introduction

Hypovolaemiaisapotentiallytreatablecauseofcardiacarrest thatusuallyresultsfromareducedintravascularvolume(i.e. hae-morrhage),butrelativehypovolaemiamayalsooccurinpatients withseverevasodilation(e.g.anaphylaxis,sepsis).Hypovolaemia frommediator-activatedvasodilationandincreasedcapillary per-meability is a major factor causing cardiac arrest in severe anaphylaxis.96Hypovolaemiafrombloodloss,isa leadingcause

ofdeathintraumaticcardiacarrest.97Externalbloodlossisusually

obvious,e.g.trauma,haematemesis,haemoptysis,butmaybemore challengingtodiagnosewhenoccult,e.g.gastrointestinal bleed-ingorruptureofanaorticaneurysm.Patientsundergoingmajor surgeryareathigh-riskfromhypovolaemiaduetopost-operative haemorrhageandmustbeappropriatelymonitored(see perioper-ativecardiacarrest).

Dependingonthesuspectedcause,initiatevolumetherapywith warmedblood products and/orcrystalloids,in order to rapidly restoreintravascularvolume.Atthesametime,initiate immedi-ateinterventiontocontrolhaemorrhage,e.g.surgery,endoscopy, endovasculartechniques,98ortreattheprimarycause(e.g.

anaphy-lacticshock).Intheinitialstagesofresuscitationuseanycrystalloid solutionthatisimmediatelyavailable.Ifthereisaqualified sono-grapherabletoperformultrasoundwithoutinterruptiontochest compressions,e.g.duringrhythmcheckorventilations,itmaybe consideredasanadditionaldiagnostictoolinhypovolaemiccardiac arrest.

Treatmentrecommendationsforcardiacarrestandperiarrest situationsin anaphylaxisandtraumaare addressedinseparate sectionsbecauseoftheneedforspecifictherapeuticapproaches. Anaphylaxis

Definition. A precise definition of anaphylaxisis not important foritsemergencytreatment.99TheEuropeanAcademyofAllergy

and Clinical Immunology Nomenclature Committee proposed thefollowing broad definition:100 anaphylaxisis a severe,

life-threatening,generalisedorsystemichypersensitivityreaction.This is characterised by rapidly developing life-threatening airway and/orbreathingand/orcirculation problemsusuallyassociated withskinandmucosalchanges.1,96,101,102

Epidemiology. Anaphylaxisiscommonandaffectsabout1in300 oftheEuropeanpopulationatsomestageintheirlives,withan incidencefrom1.5 to7.9 per100,000person-years.103

Anaphy-laxiscanbetriggeredbyanyofaverybroadrangeoftriggerswith food,drugs,stinginginsects,andlatexthemostcommonly iden-tifiedtriggers.103Foodisthecommonesttriggerinchildrenand

drugsthecommonestinadults.104Virtuallyanyfoodordrugcan

beimplicated,butcertainfoods(nuts)anddrugs(muscle relax-ants,antibiotics,nonsteroidalanti-inflammatorydrugsandaspirin) causemostreactions.105Asignificantnumberofcasesof

anaphy-laxisareidiopathic.Between1992and2012intheUK,admission andfatalityratesfordrug-andinsectsting-inducedanaphylaxis werehighestinthegroupaged60years andolder.Incontrast, admissionsduetofood-triggeredanaphylaxisweremostcommon inyoungpeople,withamarkedpeakintheincidenceoffatalfood reactionsduringthesecondandthirddecadesoflife.106

Theoverallprognosisofanaphylaxisisgood,withacase fatal-ityratiooflessthan1%reportedinmostpopulation-basedstudies. TheEuropeanAnaphylaxisRegistryreportedthatonly2%of3333 caseswereassociatedwithcardiacarrest.107Ifintensivecareunit

admissionisrequired,survivaltodischargeisover90%.Overthe period2005–2009,therewere81paediatricand1269adult admis-sionswithanaphylaxisadmittedtoUKcriticalcareunits.Survival todischargewas95%forchildren,and92%foradults.108

Anaphylaxisandriskofdeathisincreasedinthosewith pre-existing asthma,particularlyifthe asthmais poorly controlled, severeorinasthmaticswhodelaytreatment.109,110When

anaphy-laxisisfatal,deathusuallyoccursverysoonaftercontactwiththe trigger.Fromacaseseries,fatalfoodreactionscauserespiratory arresttypicallywithin30–35min;insectstingscausecollapsefrom shockwithin10–15min;anddeathscausedbyintravenous med-icationoccurmostcommonlywithin5min.Deathneveroccurred morethan6haftercontactwiththetrigger.101,111

Recognition of an anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis is the likely diagno-sisif a patient whois exposed to a trigger(allergen)develops asuddenillness(usuallywithinminutes)withrapidly develop-ing life-threatening airway and/or breathing and/or circulation problemsusuallyassociatedwithskinandmucosalchanges.The reactionisusuallyunexpected.

TheEuropeanAcademyofAllergyand ClinicalImmunology’s (EAACI)TaskforceonAnaphylaxisstatethatanaphylaxisishighly likelywhenanyoneofthefollowingthreecriteriaisfulfilled96,112:

1.Acuteonsetofanillness(minutestoseveralhours)with involve-mentoftheskin,mucosaltissue,orboth(e.g.generalisedhives, pruritusorflushing,swollenlips–tongue–uvula)andatleastone ofthefollowing:

a.Respiratory compromise, e.g. dyspnoea, wheeze– bronchospasm,stridor,reducedpeakexpiratoryflow(PEF), hypoxaemia.

b.Reducedbloodpressureorassociatedsymptomsofend-organ dysfunction,e.g.hypotonia(collapse),syncope,incontinence. 2.Twoormoreofthefollowingthatoccurrapidlyafterexposure toalikelyallergenforthatpatient(minutestoseveralhours): a.Involvement of the skin–mucosal tissue, e.g. generalised

hives,itch-flush,swollenlips–tongue–uvula.

b.Respiratory compromise, e.g. dyspnoea, wheeze– bronchospasm,stridor,reducedPEF,hypoxaemia.

c.Reducedbloodpressureorassociatedsymptoms,e.g. hypoto-nia(collapse),syncope,incontinence.

d.Persistentgastrointestinalsymptoms,e.g.crampyabdominal pain,vomiting.

3.Reducedbloodpressureafterexposuretoknownallergenfor thatpatient(minutestoseveralhours):

a.Infantsandchildren:lowsystolicbloodpressure(<70mmHg from1monthto1year;<70mmHg+(2×age)from1yearto 10years;<90mmHgfrom11to17years)or>30%decreasein systolicbloodpressure.

b.Adults:systolicbloodpressureof<90mmHgor>30%decrease fromthatperson’sbaseline.

Treatment. The evidence supporting specific interventions for thetreatmentofanaphylaxisis limited.113 A systematicABCDE

approach to recognise and treat anaphylaxis is recommended withimmediateadministrationofintramuscular(IM)adrenaline (Fig.4.2).Treatlife-threateningproblemsasyoufindthem.The basicprinciplesoftreatmentarethesameforallagegroups. Moni-torallpatientswhohavesuspectedanaphylaxisassoonaspossible (e.g.byambulancecrew,intheemergencydepartment,etc.). Min-imum monitoring includes pulse oximetry, non-invasive blood pressureanda3-leadECG.

Patientpositioning. Patientswithanaphylaxiscandeteriorate andareatriskofcardiacarrestifmadetosituporstandup.114All

patientsshouldbeplacedinacomfortableposition.Patientswith airwayandbreathingproblemsmayprefertositup,asthiswill makebreathingeasier.Lyingflatwithorwithoutlegelevationis helpfulforpatientswithalowbloodpressure.

Remove the trigger(if possible). Stopany drugsuspected of causinganaphylaxis. Removethestingeraftera bee/waspsting. Earlyremovalismoreimportantthanthemethodofremoval.115Do

notdelaydefinitivetreatmentifremovingthetriggerisnotfeasible. Cardiacarrestfollowinganaphylaxis. StartCPRimmediatelyand followcurrentguidelines.ProlongedCPRmaybenecessary. Rescu-ersshouldensurethathelpisonitswayasearlyALSisessential.

Airwayobstruction. Anaphylaxiscancauseairwayswellingand obstruction.Thiswillmakeairwayandventilationinterventions (e.g.bag-maskventilation,trachealintubation,cricothyroidotomy) difficult.Considerearlytrachealintubationbeforeairwayswelling makesthisdifficult.Callforexperthelpearly.

Adrenaline (first line treatment). Adrenaline is the most impor-tantdrugforthetreatmentofanaphylaxis.116,117Althoughthere

are no randomised controlled trials,118 adrenaline is a logical

treatment and there is consistent anecdotal evidence suppor-tingitsusetoeasebronchospasmandcirculatorycollapse.Asan

Fig.4.2.Anaphylaxistreatmentalgorithm.101

alpha-receptor agonist, it reverses peripheral vasodilation and reducesoedema.Itsbeta-receptoractivitydilatesthebronchial air-ways,increasestheforceofmyocardialcontraction,andsuppresses histamineandleukotrienerelease.Activationofbeta-2adrenergic receptorsonmastcellsurfacesinhibittheiractivation,andearly adrenalineattenuatestheseverityofIgE-mediatedallergic reac-tions.Adrenalineismosteffectivewhengivenearlyaftertheonset ofthereaction,119andadverseeffectsareextremelyrarewith

cor-rectIMdoses.

Giveadrenalinetoallpatientswithlife-threateningfeatures. Ifthesefeaturesareabsentbutthereareotherfeaturesofa sys-temicallergicreaction,thepatientneedscarefulobservationand symptomatictreatmentusingtheABCDEapproach.

Intramuscularadrenaline. Theintramuscular(IM)routeisthe bestfor most individuals who have togive adrenalineto treat anaphylaxis.Monitorthepatientassoonaspossible(pulse,blood pressure,ECG,pulseoximetry).Thiswillhelpmonitortheresponse toadrenaline.TheIMroutehasseveralbenefits:

• Thereisagreatermarginofsafety. • Itdoesnotrequireintravenousaccess. • TheIMrouteiseasiertolearn.

• Patientswithknownallergiescanself-administerIMadrenaline. ThebestsiteforIMinjectionistheanterolateralaspectofthe middlethirdofthethigh.Theneedleforinjectionneedstobelong enoughtoensurethattheadrenalineisinjectedintomuscle.120

Thesubcutaneousorinhaledroutesforadrenalinearenot recom-mendedfor thetreatmentof anaphylaxisbecausetheyare less effectivethantheIMroute.121–123

Adrenaline intramuscular dose. Theevidence for the recom-mended doses is limited. The EAACI suggests IM adrenaline (1mgmL−1)shouldbegivenadoseof10mcgkg−1ofbodyweight toamaximumtotaldoseof0.5mg.96

Thefollowingdosesarebasedonwhatisconsideredtobesafe andpracticaltodrawupandinjectinanemergency(equivalent volumeof1:1000adrenalineisshowninbrackets):

>12yearsandadults 500microgramIM(0.5mL)

>6–12years 300microgramIM(0.3mL)

>6months–6years 150microgramIM(0.15mL)

<6months 150microgramIM(0.15mL)

Repeat the IM adrenaline dose if there is no improve-mentinthepatient’s conditionwithin5min.Furtherdosescan be given at about 5-min intervals according to the patient’s response.

Intravenousadrenaline(forspecialistuseonly). Thereisamuch greater risk of causing harmful side effects by inappropriate dosageormisdiagnosisofanaphylaxiswhenusingintravenous(IV) adrenaline.124IVadrenalineshouldonlybeusedbythose

expe-riencedintheuseandtitration ofvasopressorsintheirnormal clinicalpractice(e.g.anaesthetists,emergencyphysicians, inten-sivecaredoctors).Inpatientswithaspontaneouscirculation,IV adrenalinecancauselife-threatening hypertension,tachycardia, arrhythmias,andmyocardialischaemia.IfIVaccessisnotavailable ornotachievedrapidly,usetheIMrouteforadrenaline.Patients whoaregivenIVadrenalinemustbemonitored–continuousECG andpulseoximetryandfrequentnon-invasivebloodpressure mea-surementsasaminimum.PatientswhorequirerepeatedIMdoses ofadrenalinemaybenefitfromIVadrenaline.Itisessentialthat thesepatientsreceiveexperthelpearly.

Adrenalineintravenousdose(forspecialistuseonly).

• Adults:TitrateIVadrenalineusing50microgramboluses accord-ingtoresponse.Ifrepeatedadrenalinedosesareneeded,startan IVadrenalineinfusion.125,126

• Children:IMadrenalineisthepreferredrouteforchildren hav-inganaphylaxis.TheIVrouteisrecommendedonlyinspecialist

paediatricsettingsbythosefamiliarwithitsuse(e.g.paediatric anaesthetists,paediatricemergencyphysicians,paediatric inten-sivists)andifthepatientismonitoredandIVaccessisalready available.Thereisnoevidenceonwhichtobaseadose recom-mendation–thedoseistitratedaccordingtoresponse.Achild mayrespondtoadoseassmallas1mcgkg−1.Thisrequiresvery carefuldilutionandcheckingtopreventdoseerrors.

Adrenalineintravenous/intraosseousdose(incardiacarrestonly). Cardiacarrestwithsuspectedanaphylaxisshouldbetreatedwith standard dosesofIV orintraosseous (IO)adrenalineforcardiac arrest.Ifthisisnotfeasible,considerIMadrenalineifcardiacarrest isimminentorhasjustoccurred.

Oxygen(giveassoonasavailable). Initially,givethehighest concentration of oxygen possible using a mask with an oxy-genreservoir.127 Ensure high-flowoxygen(usuallygreaterthan

10Lmin−1topreventcollapseofthereservoirduringinspiration. Ifthepatient’stracheaisintubated,ventilatethelungswithhigh concentrationoxygenusingaself-inflatingbag.

Fluids(giveassoonasavailable). Largevolumesoffluidmay leakfromthepatient’scirculationduringanaphylaxis.Therewill alsobevasodilation.IfIVaccesshasbeengained,infuseIVfluids immediately.GivearapidIVfluidchallenge(20mLkg−1)inachild or500–1000mLinanadultandmonitortheresponse;givefurther dosesasnecessary.Thereisnoevidencetosupporttheuseof col-loidsovercrystalloidsinthissetting.Considercolloidinfusionas acauseinapatientreceivingacolloidatthetimeofonsetofan anaphylaxisandstoptheinfusion.Alargevolumeoffluidmaybe needed.

IfIVaccessisdelayedorimpossible,theIOroutecanbeusedfor fluidsordrugs.DonotdelaytheadministrationofIMadrenaline whileattemptingIOaccess.

Antihistamines(giveafterinitialresuscitation). Antihistamines are a second line treatment for anaphylaxis. The evidence to support their use is limited, but there are logical reasons for theiruse.128H

1-antihistamineshelpcounterhistamine-mediated vasodilation, bronchoconstriction, and particularly cutaneous symptoms.Thereislittleevidencetosupporttheroutineuseofan H2-antihistamine(e.g.ranitidine,cimetidine)fortheinitial treat-mentofanaphylaxis.

Glucocorticosteroids(giveafterinitialresuscitation). Corticoste-roidsmayhelppreventorshortenprotractedreactions,although theevidenceislimited.129Inasthma,earlycorticosteroidtreatment

isbeneficialinadultsandchildren.Thereislittleevidenceonwhich tobasetheoptimumdoseofhydrocortisoneinanaphylaxis.

Otherdrugs.

Bronchodilators. Thepresentingsymptomsandsignsofsevere anaphylaxisandlife-threateningasthmacanbethesame.Consider furtherbronchodilator therapy withsalbutamol (inhaledor IV), ipratropium(inhaled),aminophylline(IV)ormagnesium(IV)(see asthma).IVmagnesiumisavasodilatorandcanmakehypotension worse.

Cardiac drugs. Adrenalineremains thefirstlinevasopressor for thetreatmentof anaphylaxis. Thereare animal studiesand casereportsdescribingtheuseofothervasopressorsandinotropes (noradrenaline,vasopressin,terlipressinmetaraminol, methoxam-ine,andglucagon)wheninitialresuscitationwithadrenalineand fluidshasnotbeensuccessful.130–142Usethesedrugsonlyin

spe-cialistsettings(e.g.ICU)where thereisexperienceintheiruse. Glucagoncanbeusefultotreat anaphylaxisina patienttaking a beta-blocker.143 Some case reports of cardiac arrest suggest

cardiopulmonarybypass144,145ormechanicalchestcompression