Revue canadienne de counseling et de psychothérapie ISSN 0826-3893 Vol. 46 No. 3 © 2012 Pages 239–258

Resolving Partnership Ambivalence: A Randomized

Controlled Trial of Very Brief Cognitive and Experiential

Interventions with Follow-Up

Résolution de l’ambivalence du partenariat :

Essai clinique randomisé d’interventions cognitives et

expérientielles très brèves avec suivi

Manuel Trachsel

University of Zurich, Switzerland

Lara Ferrari

University of Bern, Switzerland

Martin Grosse Holtforth

University of Zurich, Switzerland abstractBoth the experiential two-chair approach (TCA) and the cognitive decision-cube technique (DCT) have been used for the treatment of ambivalence in counselling. The aims of this study were (a) to show that partnership ambivalence is reduced after a brief stand-alone intervention using either TCA or DCT, and (b) to test the hypothesized mechanisms of change processual activation and clarification. Fifty ambivalent partici-pants were randomly assigned to either TCA or DCT interventions of two sessions each. Results indicated that partnership ambivalence was reduced after both interventions. The TCA was associated with a significantly higher processual activation than was the DCT.

résumé

On a eu recours à l’approche expérientielle de la chaise vide (TCA) et à la technique cognitive du cube décisionnel (DCT) pour le traitement de l’ambivalence en counseling. Ce sondage visait à (a) démontrer que l’ambivalence du partenariat est réduite après une brève intervention autonome ayant recours à la TCA ou à la DCT et (b) tester l’hypothèse des mécanismes de changement par activation et clarification processuelles. Cinquante participants ambivalents ont été soumis de façon aléatoire soit à une intervention de TCA, soit à une intervention de DCT, d’une durée de deux séances chacune. Les résultats indi-quent que l’ambivalence de partenariat fut réduite au terme des deux types d’intervention. L’approche TCA fut associée à une activation processuelle considérablement plus élevée que dans le cas de la DCT.

A good partnership is among the most important conditions for a fulfilling life. Love, partnership, and family have been identified as central factors for well-being in various surveys (see Bodenmann, 2002, for a review). A central motive of individuals in committed relationships (partnerships) is intimacy, which is subjectively experienced as a feeling of connectedness (e.g., Laurenceau, Rivera,

240 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

Schaffer, & Pietromonaco, 2004). Consequently, it can be assumed that the in-timacy motive is activated in persons within close relationships most of the time (Fitzsimons & Bargh, 2003).

Besides striving for relationship satisfaction, individuals also try to avoid threats to their intimate relationship or its quality, such as couple conflicts (e.g., Simpson, Oriña, & Ickes, 2003). Accordingly, couple conflicts are considered central char-acteristics of dysfunctional partnerships (Fincham & Beach, 1999), and a phase of increased interpersonal conflicts typically precedes separation (Duck, 1982). Furthermore, interpersonal conflicts are assumed to go along with inner conflicts, such as feelings of ambivalence (Duck, 1982). Ambivalent partners are usually not sure if a separation would be the right thing to do or whether they should give the continuation of the partnership another chance (e.g., Riehl-Emde, Frei, & Willi, 1994). If in this situation an ambivalent person is incapable of making a decision, the ambivalence regarding continuation or separation (subsequently named partnership ambivalence) will most likely constitute a heavy burden (e.g., Braverman, 1987; van Harreveld, Rutjens, Rotteveel, Nordgren, & van der Pligt, 2009).

Generally, ambivalence is understood as a specific kind of intrapersonal moti-vational conflict that is to be distinguished from interpersonal conflicts (Grosse Holtforth & Michalak, 2008). Sincoff (1990) defined ambivalences as “overlap-ping approach-avoidance tendencies, manifested behaviorally, cognitively, or af-fectively, and directed toward a given person, experience, or other object, as well as toward a set of objects” (p. 44).

Because ambivalence is subjectively experienced as a burden, a longer period of ambivalence may be associated with psychological symptoms such as depres-siveness, helplessness, or fear about the future (e.g., Kelly, Mansell, & Wood, 2011). Accordingly, Boller (2009) found a cross-sectional, positive relationship between partnership ambivalence and depressive symptoms. The diathesis-stress model of depression (e.g., Brown & Moran, 1998) assumes that an individual may develop clinical depression if he or she has some biological, psychological, and sociocultural predispositions and is exposed to high levels of stress. Empirical research confirms that an accumulation of stressors increases the risk of develop-ing a depressive disorder (Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1999), and that the experience of intrapersonal conflicts is related to depression (e.g., Stangier, Ukrow, Schermelleh-Engel, Grabe, & Lauterbach, 2007).

interventions for resolving partnership ambivalence

Very stressful ambivalence may be an independent reason why individuals seek out counselling or psychotherapy. Assuming that intense and enduring am-bivalence may result in psychological problems and disorders, the development of effective interventions for resolving ambivalence seems strongly indicated. Consequently, several interventions were used in this study to treat partnership ambivalence.

The aim of psychological interventions for the treatment of goal and decision conflicts (e.g., Engle & Arkowitz, 2006; Grosse Holtforth & Michalak, 2008; Trachsel & Grosse Holtforth, 2012) is to weaken or resolve the intrapersonal con-flict. These interventions may also be located in the phase models of psychological change. In terms of the stages of change model (e.g., Prochaska & Norcross, 2004), ambivalence-focused interventions attempt to help the person shift from the stages of precontemplation and contemplation (ambivalence is located at the stage of contemplation) to the stages of preparation and action. In the decisional Rubicon model (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2005), the Rubicon demarcates the border between motivation and volition. In this model, the Rubicon is transgressed by developing a clear intention, whereby cognitive-emotional-motivational processing (clarification) no longer stands in the foreground, but becomes the realization of the intention (i.e., mastering the problem instead of understanding it).

In the present study, we investigated two interventions for changing ambiva-lence: the two-chair approach (TCA) and the decision-cube technique (DCT; Bents, 2006). The origins of the TCA lie in gestalt therapy (Perls, Hefferline, & Goodman, 1951). It was later refined by Greenberg, Rice, and Elliott (2003) and by Engle and Arkowitz (2006, 2008). The goal of the TCA is to create an awareness of both sides of the ambivalent experience in order to prepare later integration. According to Engle and Arkowitz (2008), the counsellor supports the client in the evocation and expression of cognitions, feelings, and action tendencies regarding the two sides of the ambivalence. The counsellor thereby assumes an active and directive role. In the TCA, the counsellor attempts to transfer the intrapersonal conflict into an interpersonal conflict by assigning each side of the ambivalence to one of the two chairs and letting the patient enact these two sides by switching between the chairs when taking one or the other position.

Although the TCA is often combined with other techniques within emotion-focused counselling and psychotherapy, it can also be applied as a brief stand-alone intervention (Engle & Arkowitz, 2006). Studies with ambivalent students (Green-berg & Clarke, 1979) and with counselling clients (Green(Green-berg & Dompierre, 1981) found that persons treated by the TCA showed higher levels of cognitive-emotional processing than persons from a comparison group (empathic reflection). However, after two sessions, participants in both conditions were less ambivalent, and no difference between the conditions could be shown.

Subsequently, Clarke and Greenberg (1986) conducted a randomized controlled trial with ambivalent persons in which the TCA was investigated as a stand-alone intervention during two sessions. This was then compared to a treatment group with which a cognitive-behavioural problem-solving technique was implemented and to a control group without any intervention. In both intervention conditions, ambivalence was significantly reduced in comparison to the control group. In ad-dition, persons in the TCA condition improved more with respect to indecisiveness in comparison to participants in the cognitive-behavioural problem-solving group. These results indicate that the TCA is a reasonable stand-alone intervention for the treatment of ambivalence. However, the empirical basis is too limited for

242 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

drawing unambiguous conclusions regarding the efficacy and effectiveness of the TCA (Engle & Arkowitz, 2006).

The DCT has been presented as a method for clarifying ambivalence with respect to beginning psychological treatment (Bents, 2006). During the DCT exercise, clients write down the advantages and disadvantages of both sides of the ambivalence within a graphically depicted decision-cube that contains four blank spaces. The DCT is frequently used in counselling and psychotherapy in various forms (e.g., as a two-column technique or as a four-fields technique). We are not aware of any studies that have tested the DCT as a stand-alone treatment (see Engle & Arkowitz, 2006). In the present study, the DCT and the TCA are applied as stand-alone treatments to ambivalence regarding continuation of or separation from the partnership.

Mechanisms of Change

To examine the differences of the DCT and the TCA at the level of therapy processes, two of the four specific mechanisms of change (i.e., processual activa-tion, resource activaactiva-tion, clarificaactiva-tion, and mastery/coping), according to Grawe’s (1997) change model, were examined (i.e., processual activation and clarification). Processual activation is defined as the actuation of the relevant problems (Gas-smann, 2002), and is considered a prerequisite for making corrective experiences (Alexander & French, 1946; Goldfried, 1980). Corrective experiences can take the form of clarification experiences or mastery experiences.

Clarification-focused interventions foster the awareness of motives, feelings, and behaviours (Grawe, 1997) in order to trigger direct cognitive, emotional, and motivational changes related to the patient’s problems that may, for example, be experienced as insights (Castonguay & Hill, 2007). In problem mastery/coping, the person experiences higher levels of self-efficacy by successfully coping with the current problem. Behavioural interventions, such as assertiveness training, are examples of mastery-oriented interventions (Grawe, 1997). The two change mechanisms were assessed from the patient’s perspective (experiences) as well as from the counsellor’s perspective (interventions). In the context of the current study, processual activation is expected to differentiate between the TCA and the DCT.

In addition, the DCT and the TCA are also assumed to differ with respect to the modes of information processing that are involved. In the dual-process model of Beevers (2005), two modes are proposed: implicit and explicit (e.g., Smith & DeCoster, 2000). The implicit mode refers to automatic, associative, and unconscious processes, whereas the explicit mode refers to conscious, more reflected processes. The DCT is a rationality-based cognitive technique. In the DCT, clarification mainly happens via the explicit processing mode. If addition-ally implicit motives are activated, this occurs top-down virtuaddition-ally as a side effect. However, the TCA is an emotion-focused intervention in which (apart from explicit activation of content readily available consciously) implicit memory content that is not easily accessible by conscious effort is also activated. For this

reason, the effects of the TCA are assumed to be more sustainable than those of the DCT (see Hypotheses below).

Techniques for reducing ambivalence can clearly be classified as clarification techniques. Therefore, the change mechanism of clarification is the focus of this research, and the techniques under investigation were designed to achieve clarifica-tion. Whereas resource activation as well as mastery are generally very important additional change factors in psychotherapy, the additional investigation of resource activation or mastery would extend the research questions and would require further changes to the design and implementation of the study. This would have been beyond the scope of this project.

Hypotheses

In the present study, the following hypotheses regarding the efficacy of the intervention techniques and the mechanisms of change were investigated. efficacy

The level of partnership ambivalence will be reduced after two psychological ses-sions with either the TCA or the DCT. Although, neither of the two interventions is expected to be significantly superior 2 weeks after the intervention, the TCA is expected to show a stronger ambivalence reduction than the DCT after 4 months. In addition, we hypothesized that partnership ambivalence relates positively to depressive symptoms and distress, and relates negatively to satisfaction with life. mechanisms of change

We hypothesized that the TCA is associated with a stronger processual activa-tion than the DCT. In addiactiva-tion, it is expected that stronger processual activaactiva-tion in the TCA is commensurate with higher levels of clarification in this condition compared to the DCT condition.

methods Study Design, Randomization, and Procedures

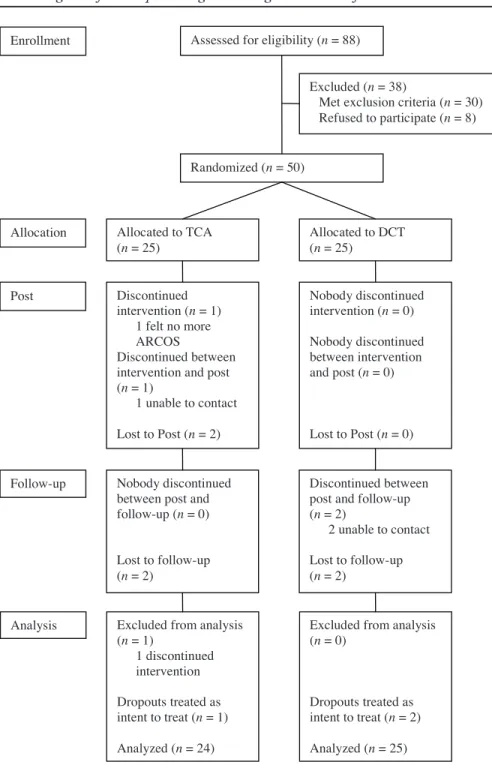

The hypotheses were tested within a randomized controlled trial (see Figure 1). We assessed the eligibility of subjects using self-report measures (see Measures section). When participants met the inclusion criteria (see Sample section), they were randomly assigned to either the TCA or to the DCT condition. The randomi-zation was stratified regarding the sex of the participants resulting in two separate randomization lists: 25 participants were assigned to the TCA condition and 25 participants were assigned to the DCT condition. Participants were unaware of their allocation and the hypotheses.

Over the course of 2 weeks, two intervention sessions were conducted. The first session served as exploration and preparation for the specific interventions in the second session. Structured intervention manuals of the TCA and the DCT

244 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse HoltforthAmbivalence reduction 32

Assessed for eligibility (n = 88)

Excluded (n = 38)

Met exclusion criteria (n = 30) Refused to participate (n = 8)

Randomized (n = 50) Enrollment

Allocation Allocated to TCA

(n = 25) Allocated to DCT (n = 25) Discontinued intervention (n = 1) 1 felt no more ARCOS Discontinued between intervention and post (n = 1) 1 unable to contact Lost to Post (n = 2) Nobody discontinued intervention (n = 0) Nobody discontinued between intervention and post (n = 0) Lost to Post (n = 0) Post

Follow-up Nobody discontinued between post and follow-up (n = 0)

Lost to follow-up (n = 2)

Discontinued between post and follow-up (n = 2)

2 unable to contact Lost to follow-up (n = 2)

Analysis Excluded from analysis (n = 1) 1 discontinued intervention Dropouts treated as intent to treat (n = 1) Analyzed (n = 24)

Excluded from analysis (n = 0)

Dropouts treated as intent to treat (n = 2) Analyzed (n = 25)

Figure 1. Flow diagram of participant progress through the phases of randomized trial.

Figure 1

interventions (Trachsel, 2009a, 2009c) were used. One week after the second session, a manualized 10-minute booster session was conducted by telephone in which the psychologists refreshed the most relevant content (Trachsel, 2009b). Two weeks after the second session, participants completed the post assessment, and 4 months after the second session, they completed the follow-up assessment. Sample

The study was conducted in Switzerland in the German language. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) participants were currently in a partnership, (b) they experienced ambivalence regarding the continuation of or separation from the part-nership, and (c) they had given their informed consent for the planned course of study. Exclusion criteria were (a) a self-reported mental disorder that corresponds to a diagnosis on axis I of DSM-IV; (b) substance dependence or psychological counselling/therapy within the last year; (c) current use of antidepressant medica-tion, benzodiazepines, or barbiturates; and (d) having acute suicidal tendency.

The mean age of participants was 38.3 years (SD = 10.5). Twenty-nine par-ticipants (57.1%) were female; 24 parpar-ticipants (49%) were unmarried and in a partnership; 25 participants (51%) were either married, divorced, or widowed but in a partnership; 27 participants (55.1%) had felt ambivalent for one year or less; and 22 participants (44.9%) had felt ambivalent for more than one year. The two conditions did not differ significantly regarding age, sex, relationship status, or duration of partnership ambivalence prior to the interventions as tested by independent-samples t- and c2-tests.

Psychologists

Fourteen master’s-level psychologists (12 female, 85.7%) conducted the inter-vention sessions. To control for therapist effects as far as possible, every psycholo-gist conducted both interventions and was unaware of the specific hypotheses. All psychologists participated in a half-day training workshop that was supervised by two independent experienced psychotherapists with training in an integrative form of psychotherapy.

Measures

ambivalence regarding continuation or separation of the relationship questionnaire (arcos)

The German-language ARCOS (Trachsel & Boller, 2008) was developed based on the English-language Indecisiveness Scale (Germeijs & De Boeck, 2002). The ARCOS measures partnership ambivalence using 9 self-report items and a 7-point Likert scale ranging from not at all to very much. The ARCOS has shown a high internal consistency in a study by Boller (2009) as well as showing good construct validity by highly significant correlations with similar constructs such as partner-ship ambivalence, as measured by the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976); entrapment, as measured by the Entrapment Scale (Gilbert & Allan, 1998); and

246 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

hopelessness, as measured by the Hopelessness Scale (A. T. Beck, Weissmann, Lester, & Trexler, 1974). In the present study, Cronbach’s a was .80.

perceived stress questionnaire (psq)

The PSQ (Levenstein et al., 1993) is an English-language self-report question-naire for the assessment of the subjectively perceived stress level. Fliege and col-leagues (2005) translated the PSQ into German and shortened it from 30 to 20 items. The original PSQ has shown good reliability (Cronbach’s a = .85; split-half reliability r = .80) as well as evidence of validity. In the present study, Cronbach’s a of the German version was .89. Construct validity has been demonstrated by cor-relations with quality-of-life measures, and external validity has been demonstrated by different samples of inpatients (e.g., PSQ values were higher in ulcerative colitis patients with an inflamed rectal mucosa than in those with a normal-appearing rectum; Fliege et al., 2005). By means of a 4-point Likert scale, answer alternatives from almost never to mostly are given.

center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (ces-d)

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) is a self-report questionnaire developed for studies with nonclinical samples to assess depressive symptoms. In this study, we used the short German version (Hautzinger & Bailer, 1993), which consists of 15 items answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from rarely to mostly. Sum scores over 18 are considered indicative of a clinically relevant depressive episode (Lehr, Hillert, Schmitz, & Sosnowsky, 2008). The German version of the CES-D showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s a = .93 for a depressive sample; Cronbach’s a = .90 in a general sample) and construct validity (correlations with other depres-sion scales, e.g., with the BDI r = .90; Hautzinger & Bailer, 1993). In the present study, Cronbach’s a was .93.

satisfaction with life scale (swls)

The SWLS (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) is a self-report ques-tionnaire measuring satisfaction with life through summing scores of five items being rated on a 7-point Likert scale (agree completely to agree not at all). The German version of the SWLS was shown to be reliable (Cronbach’s a = .88; 4 months test-retest reliability r = .74) and valid (correlations with other scales of well-being and life satisfaction; see Pavot & Diener, 1993). In the present study, Cronbach’s a was .87.

The following questionnaires were given only at the pre-assessment for examin-ing the exclusion criteria.

brief symptom inventory (bsi)

The BSI (Derogatis, 1993) measures the subjective impairment by somatic and mental symptoms. The 53 items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (not at all to very strong) are summarized in nine subscales (somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety,

paranoid ideation, and psychoticism) and three global values. For this study, all subscales and the global symptom index were taken into account. Reliabilities of the scales of the German BSI have been tested by Franke (2000; Cronbach’s a = .63–.85; one week test-retest reliability r = .73–.92). In the present study, Cronbach’s a for the overall scale was .95. Exclusion criteria for this study were a T-value of the global symptom index over 63 or T-values of at least two scales over 63 (cut-off by Lehr et al., 2008).

lübeck alcohol dependence and abuse screening test (last)

The LAST (Rumpf, Hapke, & John, 2001) is a German-language self-report test for screening persons regarding alcohol dependence or abuse. It consists of seven items with a yes-or-no response format. The LAST was shown to be reliable (Cronbach’s a = .69–.81 for different samples), valid (high positive correlations with other established alcohol dependence and abuse screening-tests), and sensitive for detecting alcoholism (Rumpf et al., 2001). In the present study, Cronbach’s a was .55. For this study, participants who answered more than one question with “yes” were excluded (cut-off according to Rumpf et al., 2001).

the drug abuse screening test (dast-10)

The DAST-10 (Cocco & Carey, 1998) is a self-report test for screening persons regarding drug dependence or abuse (without alcohol). It consists of 10 items with a yes-or-no response format. The DAST-10 showed good reliability (Cronbach’s a = .85; test-retest reliability r = .70; Cocco & Carey, 1998) and validity (abil-ity to detect drug dependence or abuse; Yudko, Lozhkina, & Fouts, 2007). The items were translated to German by the first author. A bilingual person translated the items back to English, which led to comparable items. In the present study, Cronbach’s a was .62. For this study, participants who answered more than two questions with “yes” were excluded (cut-off according to Peltzer et al., 2009). the bern post session report 2000 (bpsr-t/p)

The BPSR-T/P (Flückiger, Regli, Zwahlen, Hostettler, & Caspar, 2010) was used to analyze mechanisms of change. Its scales represent four mechanisms of change (processual activation, resource activation, clarification, and mastery/cop-ing; Grawe, 1997). The patient and therapist versions of the BPSR were completed separately by participants (patient version, BPSR-P, 22 items) and psychologists (therapist version, BPSR-T, 27 items) directly after each of the two intervention sessions. The items of the BPSR-P are answered on 7-point Likert scales (not at all to completely). The first 12 items of the BPSR-T are also answered on this 7-point Likert scale, and the remaining items on a 5-point Likert scale (not at all to com-pletely). Reliability (internal consistencies) and construct validity (within-scale correlations and convergent intercorrelations between the rater perspectives) were satisfactory in a study by Flückiger and colleagues (2010; PSTB: Cronbach’s a = .73–.85 depending on scale; TSTB: Cronbach’s a = .63–.88 depending on scale) and also for the relevant constructs investigated in this study (PSTB: Cronbach’s

248 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

a clarification = .63, Cronbach’s a processual activation = .86; TSTB: Cronbach’s a clarification = .70, Cronbach’s a processual activation = .76).

Video-rating

To analyze mechanisms of change from the observer perspective, a modified version of the consistency-theory microprocess analysis CMP (Gassmann, 2002) was used to rate video recordings of the second session of each treatment (Fer-rari & Trachsel, 2010). Suitable video recordings were available for 44 of the 49 participants (TCA: N = 22; DCT: N = 22). Two research assistants (psychology students) were trained over one week by the second author to rate the mechanisms of change, clarification, and processual activation. The interrater reliability was high (processual activation: ICCjust = .89; clarification: ICCjust = .91). Three videos (7.1%) were rated a second time after four weeks by both raters for assessing the intrarater reliability, which was high for both processual activation (Rater A: IC-Cjust = .82; p < .001; Rater B: ICCjust = .82; p < .001) and for clarification (Rater A: ICCjust = .93; p < .001; Rater B: ICCjust = .89; p < .001).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the software PASW Statistics 18.0. The nonsystemati-cally missing values were replaced using the multiple imputation (MI) procedure of the PASW software through the regression method (Rubin, 1987). Missing data of whole questionnaires that may be missing not at random (Howell, 2008) were not replaced.

results

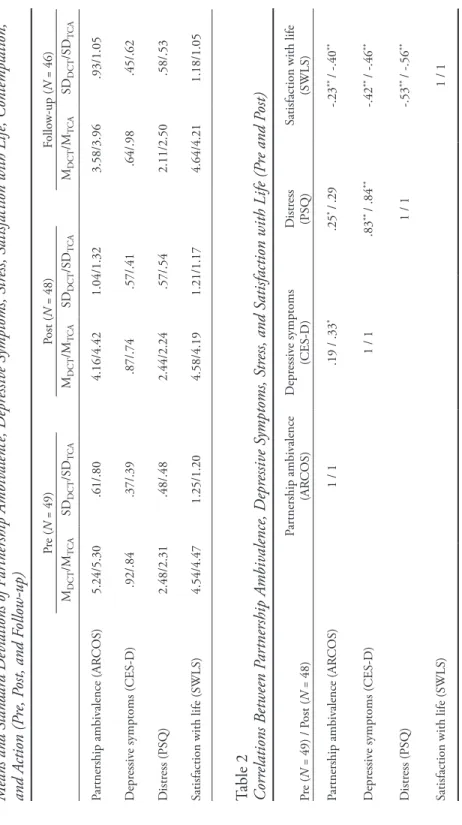

Table 1 gives an overview of the means and standard deviations of the most important constructs, while Table 2 gives the correlations between scales. Partici-pants in the DCT and the TCA did not differ significantly regarding partnership ambivalence, depressive symptoms, distress, or satisfaction with life pre-treatment (t-tests for independent samples; all p > .05). At post assessment, 9 participants were separated from their partners and 36 participants continued their partnership (3 persons did not indicate relationship status). At follow-up, 13 participants were separated from their partners, and 3 participants already had a new partnership; 36 participants continued their former partnership.

A repeated measures MANOVA was conducted for pre, post, and follow-up points with the intervention condition as the independent variable, and for part-nership ambivalence, depressive symptoms, distress, and satisfaction with life as dependent variables. The strategy for dealing with the missing values described in the data analysis section led to a rather small sample size for the MANOVA (n = 31). Despite this small sample size, Pillai’s trace indicated a significant main effect over time (within-subjects: V = .74, F[10, 20] = 5.54, p < .001). However, the MANOVA showed no significant main effect comparing the DCT and the TCA conditions using Pillai’s trace (between-subjects: V = .11, F[5, 25] = .60, p = .70).

Table 1 Means and S tandar d D eviations of P ar tnership A mbiv alence, D epr essiv e S ymptoms, S tress, S atisfaction with L ife, Contemplation, and A ction (P re, P ost, and F ollo w-up) Pr e ( N = 49) Post ( N = 48) Follo w-up ( N = 46) MDCT /M T CA SD DCT /SD T CA MDCT /M T CA SD DCT /SD T CA MDCT /M T CA SD DCT /SD T CA Par tnership ambiv alence (AR COS) 5.24/5.30 .61/.80 4.16/4.42 1.04/1.32 3.58/3.96 .93/1.05 D epr essiv e symptoms (CES-D) .92/.84 .37/.39 .87/.74 .57/.41 .64/.98 .45/.62 D istr ess (PSQ) 2.48/2.31 .48/.48 2.44/2.24 .57/.54 2.11/2.50 .58/.53

Satisfaction with life (SWLS)

4.54/4.47 1.25/1.20 4.58/4.19 1.21/1.17 4.64/4.21 1.18/1.05 Table 2 Corr elations B etw een P ar tnership A mbiv alence, D epr essiv e S ymptoms, S tress, and S atisfaction with L ife (P re and P ost) Pr e ( N = 49) / P ost ( N = 48) Par tnership ambiv alence (AR COS) D epr essiv e symptoms (CES-D) D istr ess (PSQ)

Satisfaction with life

(SWLS) Par tnership ambiv alence (AR COS) 1 / 1 .19 / .33 * .25 * /.29 -.23 ** / -.40 ** D epr essiv e symptoms (CES-D) 1 / 1 .83 ** / .84 ** -.42 ** / -.46 ** D istr ess (PSQ) 1 / 1 -.53 ** / -.56 **

Satisfaction with life (SWLS)

1 / 1

N

ote.

The v

alue befor

e the slash stands for pr

e, and the v

alue after the slash stands for post.

* p

< .05;

** p

250 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

Because we used ANOVAs in the following analyses, there were fewer miss-ing values per analysis, resultmiss-ing in an increased power for each analysis. A two-way mixed repeated measures ANOVA with the independent factors time and intervention condition, and partnership ambivalence as the dependent variable, was conducted. This yielded a significant main effect for time in both conditions (within-subjects: F[1, 43] = 63.04, p < .001; d = 1.54 from pre to follow-up). Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests showed that the pre values differed significantly from the post and the follow-up values (both p < .001). Post values did not differ significantly from follow-up values (p = .07). The ANOVA yielded no significant main effect between the TCA and the DCT condition (between-subjects: F[1, 43] = 1.40, p = .24; d = .08 at follow-up), and there was no significant interaction between time and condition (F[1, 86] = .18, p = .84).

We tested the hypothesis that, parallel to partnership ambivalence, depressive symptoms also decrease. For this purpose, a two-way mixed repeated measures ANOVA with the independent factors time and intervention condition, and de-pressive symptoms as the dependent variable, was conducted. For the overall sam-ple, neither a significant main effect over time (within-subjects: F[2, 86] = 1.04, p = .36; d = .26 from pre to follow-up) nor a significant main effect for the difference between the TCA and the DCT condition was found (between-subjects: F[1, 43] = .01, p = .91; d = .46 at follow-up). However, a significant disordinal interaction effect was found between depressive symptoms and the kind of intervention (F[1, 43] = 4.60, p < .05). For the DCT condition a significant main effect over time was found (within-subjects: F[1, 22] = 6.82, p < .05; d = .68 from pre to follow-up).

Because the duration of ambivalence correlated positively with ambivalence at post and follow-up (post: r =.33, p < .05; follow-up: r =.50, p < .01), a further ex-plorative analysis was conducted after performing a median-split of the sample on the basis of ambivalence duration. When only those participants were investigated who felt ambivalent for more than one year (N = 22), the two-way mixed repeated measures ANOVA with the independent factors time and intervention condition, and ambivalence as the dependent variable, yielded a significant between-subjects difference. Participants of the DCT condition showed significantly lower part-nership ambivalence at post compared to the TCA condition (F[1, 20] = 5.26, p < .05; d = .61 from pre to follow-up). For participants who had felt ambivalent for less than one year (N = 23) there was no such effect (F [1,21] = 1.02, p = .32; d = .02 from pre to follow-up).

It was hypothesized that the TCA is associated with a stronger processual ac-tivation and clarification than the DCT. For testing this hypothesis, self-reports by counsellors and participants, as well as video ratings, were analyzed. Table 3 shows means and standard deviations for clarification and processual activation as assessed by BPSR-P and BPSR-T directly after the second session. Table 3 also shows the medians of the video ratings of the second session. T-tests for independ-ent samples for the BPSR-P and BPSR-T data and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney two-sample rank-sum tests for the video rating data were performed, and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the direct comparison of the mechanisms of change were

3 3.5 4 4.5 5 5.5 6

Pre Post Follow-up

Am bi val en ce DCT: ambivalence over 1 year

TCA: ambivalence over 1 year

DCT: ambivalence less than 1 year

TCA: ambivalence less than 1 year

Figure 2

Comparison Between the Two Groups in Respect to Partnership Ambivalence in Due Consideration of the Duration of Partnership Ambivalence

calculated (see Table 2). Results show a significant higher processual activation for the TCA compared to the DCT condition, whereas for clartification no difference was found (self-reports by counsellors and participants and for the video ratings). Table 3

Clarification and Processual Activation Measured with BPSR-P and BPSR-T and Medians of the Video-Rating of the Second Session

DCT

(N = 25) (N = 24)TCA

BPSR-P (number of items) M (SD) M (SD) F df sig. d

Clarification (3) 1.15 (.86) 1.15 (.82) .00 47 .98 .00 Processual activation (2) .88 (1.25) 1.67 (.92) .45 46 .02* .72

Video rating of participant Md Md U df sig. d

Clarification .63 .61 188 20 .21 .25

Processual activation .56 .66 111.5 20 .00** .98

BPSR-T (number of items) M (SD) M (SD) F df sig. d

Clarification (3) 2.89 (.52) 2.70 (.74) 1.34 47 .28 .30 Processual activation (3) 2.35 (.66) 3.00 (.79) .21 47 .00** .89

Video rating of psychologist Md Md U df sig. d

Clarification .81 .86 177 20 .14 .20

Processual activation .27 .34 105 20 .00** .89

252 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

discussion

In the present study, efficacy and mechanisms of change of two very brief stand-alone interventions for resolving ambivalence regarding continuation of or separation from a partnership (partnership ambivalence) were investigated. In a randomized controlled trial, two sessions of either the two-chair approach (TCA) or the decision-cube-technique (DCT) were compared. Furthermore, we tested the hypotheses with respect to the relationship between partnership ambivalence and depressive symptoms, distress, and satisfaction with life.

The results indicated that partnership ambivalence can be reduced both by means of the very brief TCA intervention and by the very brief DCT interven-tion. The TCA is an emotion-focused intervention in which (apart from explicit activation of content that is readily available consciously) implicit memory con-tent that is not easily accessible by conscious effort is activated. For this reason, the effects of the TCA on partnership ambivalence are assumed to be more sustainable than the effects of DCT. However, no significant difference could be found regarding partnership ambivalence between the two conditions either at post or follow-up. It was tested exploratively that participants who had felt ambivalent for a longer time would benefit more from the TCA than from the DCT compared to participants who felt ambivalent for a shorter time because the stronger processual activation in the TCA condition may be necessary to destabilize more encrusted partnership ambivalence. Our results do show dif-ferential effects, but in the opposite direction. When only participants were included in the analysis who had felt ambivalent for more than one year, the partnership ambivalence decreased to a greater extent in the DCT than in the TCA. For participants who felt ambivalent for less than one year, it seemed to be irrelevant which intervention was conducted.

Apparently, for participants who felt ambivalent for more than one year, the more rational and more structured DCT had a greater success in reducing ambivalence than the more emotionally challenging TCA. This result could also indicate that these persons need a stronger therapeutic alliance for the profitable application of the TCA, which might not be possible in the course of only two intervention sessions. Another possibility is that treatment using the TCA requires greater levels of training, experience, and sophistication than the psychologists in this study were capable of providing with the relatively low level of training. Participants who felt ambivalent for less than one year seemed to benefit from only two sessions in both conditions. This result might indicate that “younger” ambivalences are less complex, and therefore easier to change. It might be that more general effects of psychological treatment, such as empathy or the induction of hope, suffice to trigger self-organizing change, rendering the type of specific intervention less relevant.

The observed reduction of partnership ambivalence suggests that the partici-pants of this study could reduce or even resolve their decisional conflicts. This latter interpretation is supported by the facts that one third of participants separated from their partners within four months after the intervention, and that the other

two thirds reported less ambivalence. The ambivalence reduction might have oc-curred because of clarification experiences.

We hypothesized that the two very brief interventions would also reduce depres-sive symptoms. This hypothesis could not be supported. Depresdepres-sive symptoms only decreased in the DCT condition, whereas depressive symptoms were not reduced at all in the TCA condition. The small effect in the DCT condition and the absent effect in the TCA condition might be explained by the exclusion of subjects who suffered from a clinically relevant depression. Most of the participants showed low depression values and therefore could not improve considerably with respect to depressive symptoms (ceiling effect). In a sample of subjects with a larger range of depression scores, clearer effects may be found.

Corresponding to our hypotheses, partnership ambivalence related positively to depressive symptoms and distress, as well as negatively to satisfaction with life. These cross-sectional results are compatible with an interpretation that strong and/ or prolonged ambivalence may result in depressive symptoms or even depressive episodes. However, longitudinal studies would be necessary to further test these theoretically plausible relationships.

In the present investigation, distinct methods (i.e., self-report, therapist re-port, and video-rating) yielded consistent results regarding the mechanisms of change involved in the TCA and the DCT conditions. Participants in the TCA condition showed higher levels of processual activation than participants in the DCT condition. However, despite the assumption that participants would make more clarification experiences in the TCA condition than in the DCT condition, the intervention techniques did not differ in this regard. This result might be interpreted in at least two ways. It might be that the DCT led to clarification experiences via cognitive processes as postulated by classic cognitive therapy (e.g., J. S. Beck, 1995) despite little processual (emotional) activation. Alternatively, it may be that the therapists using the TCA in this study did not make use of their emotional “head start” to generate powerful clarification experiences (Carryer & Greenberg, 2010). As already hypothesized with the findings regarding longer-persisting ambivalence, two TCA sessions may be too short to build a sufficiently strong therapeutic alliance and/or allow for the hypothesized clarification processes to unfold (Pos, Greenberg, Goldman, & Korman, 2003).

Limitations

The statistical power of the present study was small. However, it was large enough to detect medium-sized effects over time and would have been large enough to detect large differences between the two conditions. The assessment of eligibility was conducted through self-report measures. In future studies, standardized (clinical) interviews should also be carried out. In addition, the degree of adherence of the psychologists to the intervention manuals was not directly assessed. However, the analysis of mechanisms of change by means of post-session reports and video-ratings provide a useful approximation (Grosse

254 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

Holtforth, Grawe, Fries, & Znoj, 2008). The experimental design of the present study with its strict standardization of interventions, psychologist training, ex-ternal randomization, and the low dropout rate speak for a high inex-ternal valid-ity of the results. However, the inclusion of a non-treatment comparison group would have been beneficial. Although there were no extreme values prior to in-terventions, regression to the mean could not unambiguously be fully excluded as a statistical explanation for the observed changes in partnership ambivalence. Furthermore, it remains unclear the extent to which the results can be general-ized to other settings and samples. An advantage in this regard was the het-erogeneity of the present sample regarding sex, relationship status, and intensity and duration of ambivalence.

Future Research

Future research on ambivalence reduction by psychological interventions could profit from extensions into ambivalence or conflicts other than relation-ship ambivalence as well as from including subjects with clinically relevant levels of depression. In addition, future studies may also vary the “dose” of the used interventions with regard to their duration or by trying to optimize the qual-ity of the interventions by extending the training of the counsellors. Moreover, designated experts of the TCA and the DCT should be included as counsellors and/or specialists who rate adherence and competence regarding the treatments provided. Furthermore, in future studies, sample sizes should be enlarged so that not only decreases of ambivalence over time could be detected, but also middle or even small effects between the different intervention forms. Hence, it would be possible to investigate factors other than duration of ambivalence for differ-ential indication. This could pave the way for a more specific application of the different techniques depending on the characteristics of persons who are seeking counselling or psychotherapy.

References

Alexander, F., & French, T. M. (1946). Psychoanalytic therapy: Principles and applications. New York, NY: Wiley.

Beck, A. T., Weissmann, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 861–865. doi:10.1037/ h0037562

Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. New York, NY: Guilford.

Beevers, C. G. (2005). Cognitive vulnerability to depression: A dual process model. Clinical

Psy-chology Review, 25, 975–1002. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.003

Bents, H. (2006). Entscheidungswürfel. In S. Fliegel & A. Kämmerer (Eds.), Psychotherapeutische

Schätze [Psychotherapeutic treasures] (pp. 51–53). Tübingen, Germany: dgvt-Verlag.

Bodenmann, G. (2002). Beziehungskrisen: Erkennen, verstehen und bewältigen [Relationship crises: To recognize, to understand, and to master]. Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

Boller, M. (2009). Test-theoretic evaluation of the ambivalence regarding continuation or separation

of the relationship questionnaire (ARCOS). Unpublished manuscript, University of Bern, Bern,

Switzerland.

Braverman, S. (1987). Chronic ambivalence: An individual and marital problem. Psychotherapy:

Brown, G. W., & Moran, P. (1998). Emotion and the etiology of depressive disorders. In W. F. Flack & J. D. Laird (Eds.), Emotions in psychopathology (pp. 171–184). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Carryer, J. R., & Greenberg, L. S. (2010). Optimal levels of emotional arousal in experiential therapy of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 190–199. doi:10.1037/a0018401

Castonguay, L. G., & Hill, C. E. (2007). Insight in psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/11532-000

Clarke, K. M., & Greenberg, L. S. (1986). Differential effects of Gestalt two-chair intervention and problem-solving in resolving decisional conflict. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33, 11–15.

doi:10.1037//0022-0167.33.1.11

Cocco, K. M., & Carey, K. B. (1998). Psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in psychiatric outpatients. Psychological Assessment, 10, 408–414. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.10.4.408

Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual (4th ed.). Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale.

Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Duck, S. (1982). A topography of relationship disengagement and dissolution. In S. Duck & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Personal relationships (pp. 1–29). London, UK: Academic Press.

Engle, D. E., & Arkowitz, H. (2006). Ambivalence in psychotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Engle, D. E., & Arkowitz, H. (2008). Viewing resistance as ambivalence: Integrative

strate-gies for working with resistant ambivalence. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48, 389–412.

doi:10.1177/0022167807310917

Ferrari, L., & Trachsel, M. (2010). Rating manual for the analysis of the mechanisms of change

processual activation and clarification of the two-chair approach and the decision-cube technique.

Unpublished manual, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. (1999). Marital conflict: Implications for working with couples.

Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 47–77.

Fitzsimons, G. M., & Bargh, J. A. (2003). Thinking of you: Nonconscious pursuit of interpersonal goals associated with relationship partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 148–164. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.84.1.148

Fliege, H., Rose, M., Arck, P., Walter, O. B., Kocalevent, R., Weber, C., & Klapp, W. F. (2005). The Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) reconsidered: Validation and reference values from different clinical and healthy adult samples. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 78–88. doi:10.1097/01. psy.0000151491.80178.78

Flückiger, C., Regli, D., Zwahlen, D., Hostettler, S., & Caspar, F. (2010). Der Berner Patienten- und Therapeutenstundenbogen 2000. Ein Instrument zur Erfassung von Therapieprozessen [The Bern Post Session Report 2000, patient and therapist versions: Measuring psychotherapeutic processes]. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 39, 71–79. doi:10.1026/1616-3443/a000015

Franke, G. H. (2000). Brief Symptom Inventory von Derogatis. Kurzform der SCL-90-R (BSI) [Brief Symptom Inventory of Derogatis. Short form of the SCL-90-R (BSI)]. Göttingen, Germany: Beltz Test.

Gassmann, D. (2002). Korrektive Erfahrungen im Psychotherapieprozess. Entwicklung und Anwendung

der Konsistenztheoretischen Mikroprozessanalyse [Corrective experiences in the psychotherapy

process. Development and application of the Consistency-Theory Micro-Process Analysis] (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland.

Germeijs, V., & De Boeck, P. (2002). A measurement scale for indecisiveness and its relationship to career indecision and other types of indecision. European Journal of Psychological Assessment,

18(2), 113–122. doi:10.1027//1015-5759.18.2.113

Gilbert, P., & Allan, S. (1998). The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: An exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychological Medicine, 28, 585–598. doi:10.1017/ S0033291798006710

256 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth Goldfried, M. R. (1980). Toward the delineation of therapeutic change principles. American

Psych-ologist, 35, 991–999. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.35.11.991

Grawe, K. (1997). Research informed psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 7, 1–19. doi:10.108 0/10503309712331331843

Greenberg, L. S., & Clarke, K. M. (1979). Differential effects of the two-chair experiment and empathic reflection at a conflict marker. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 26, 1–8.

doi:10.1037//0022-0167.26.1.1

Greenberg, L. S., & Dompierre, L. M. (1981). Specific effects of Gestalt two-chair dialogue on intra-psychic conflict in counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28, 288–296. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.28.4.288

Greenberg, L. S., Rice, L. N., & Elliott, R. (2003). Facilitating emotional change: The moment by

moment process. New York, NY: Guilford.

Grosse Holtforth, M., Grawe, K., Fries, A., & Znoj, H. (2008). Inkonsistenz als differentielles Indikationskriterium in der Psychotherapie - eine randomisierte kontrollierte Studie [Inconsis-tency as a criterion for differential indication in psychotherapy: A randomized controlled trial].

Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 37(2), 103–111. doi:10.1026/1616-3443.37.2.103

Grosse Holtforth, M., & Michalak, J. (2008). Bearbeitung von Ambivalenzen [Treatment of am-bivalence]. In J. Margraf & S. Schneider (Eds.), Lehrbuch der Verhaltenstherapie [Textbook of behavior therapy] (pp. 631–646). Berlin, Germany: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-79543-8

Hautzinger, M., & Bailer, M. (1993). Allgemeine Depressions Skala [The General Depression Scale]. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz.

Heckhausen, J., & Heckhausen, H. (2005). Motivation und Handeln [Motivation and action]. Berlin, Germany: Springer. doi:10.1007/3-540-29975-0

Howell, D. C. (2008). The treatment of missing data. In W. Outhwaite & S. Turner (Eds.), Handbook

of social science methodology (pp. 208–224). London, UK: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781848607958.n11

Kelly, R. E., Mansell, W., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Goal conflict and ambivalence interact to predict depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 531–534. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.11.018

Kendler, K. S., Karkowski, L. M., & Prescott, C. A. (1999). Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 837–848. Laurenceau, J. P., Rivera, M. L., Schaffer, A. R., & Pietromonaco, P. R. (2004). Intimacy as an

interpersonal process: Current status and future directions. In D. J. Mashek & A. P. Aron (Eds.),

Handbook of closeness and intimacy (pp. 61–80). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lehr, D., Hillert, A., Schmitz, E., & Sosnowsky, N. (2008). Screening depressiver Störungen mittels Allgemeiner Depressions-Skala (ADS-K) und State-Trait Depressions Scales (STDS-T). Eine vergleichende Evaluation von Cut-Off-Werten [Assessing depressive disorders using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) and State-Trait Depression Scales (STDS-T): A comparative analysis of cut-off scores]. Diagnostica, 54, 61–70. doi:10.1026/0012-1924.54.2.61

Levenstein, S., Prantera, C., Varvo, V., Scribano, M. L., Berto, E., Luzi, C., & Andreoli, A. (1993). Development of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire: A new tool for psychosomatic research.

Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 37, 19–32. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(93)90120-5

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychological Assessment,

5, 164–172. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.5.2.164

Peltzer, K., Simbayi, L., Kalichman, S., Jooste, S., Cloete, A., & Mbelle, N. (2009). Drug use and HIV risk behaviour in three urban South African communities. Journal of Social Sciences, 18, 143–149.

Perls, F., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt therapy. New York, NY: Julian Press. Pos, A. E., Greenberg, L. S., Goldman, R. N., & Korman, L. M. (2003). Emotional processing

during experiential treatment of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 1007–1016. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1007

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2004). Stages of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice,

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306

Riehl-Emde, A., Frei, R., & Willi, J. (1994), People in divorce and their ambivalence: Initial use of a newly developed couples inventory. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Medizinische

Psychologie, 44, 37–45.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470316696

Rumpf, H. J., Hapke, U., & John, U. (2001). Lübecker Alkoholabhängigkeits- und -missbrauchs-

Screening-Test (LAST) [Lübeck Alcohol Dependence and Abuse Screening Test (LAST)].

Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Simpson, J. A., Oriña, M., & Ickes, W. (2003). When accuracy hurts, and when it helps: A test of the empathic accuracy model in marital interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

85, 881–893. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.881

Sincoff, J. B. (1990). The psychological characteristics of ambivalent people. Clinical Psychology

Review, 10, 43–68. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(90)90106-K

Smith, E. R., & DeCoster, J. (2000). Dual-process models in social and cognitive psychology: Conceptual integration and links to underlying memory systems. Personality and Social

Psychol-ogy Review, 4, 108–131. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_01

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of mar-riage and similar dyads. Journal of Marmar-riage and the Family, 38, 15–28. doi:10.2307/350547

Stangier, U., Ukrow, U., Schermelleh-Engel, K., Grabe, M., & Lauterbach, W. (2007). Intrapersonal conflict in goals and values of patients with unipolar depression. Psychotherapy and

Psychosomat-ics, 76, 162–170. doi:10.1159/000099843

Trachsel, M. (2009a). Decision-cube technique: Intervention manual for the ambivalence trial. Un-published manuscript, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Trachsel, M. (2009b). Intervention manual for the booster-session by telephone of the ambivalence trial. Unpublished manuscript, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Trachsel, M. (2009c). Two-chair approach. Intervention manual for the ambivalence trial. Unpublished manuscript, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Trachsel, M., & Boller, M. (2008). Ambivalence regarding continuation or separation of the

relation-ship questionnaire (ARCOS). Unpublished manuscript, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Trachsel, M., & Grosse Holtforth, M. (2012). Techniken zur Bearbeitung von Ambivalenzen in der Psychotherapie [Techniques for treating ambivalence in psychotherapy]. In G. Meinlschmidt, S. Schneider, & J. Margraf (Eds.), Lehrbuch der Verhaltenstherapie. Materialien für die

Psycho-therapie (Bd. 4) [Textbook of behavioral therapy: Materials for psychotherapy (Vol. 4)]. Berlin,

Germany: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01713-1

van Harreveld, F., Rutjens, B. T., Rotteveel, M., Nordgren, L. F., & van der Pligt, J. (2009). Am-bivalence and decisional conflict as a cause of psychological discomfort: Feeling tense before jumping off the fence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 167–173. doi:10.1016/j. jesp.2008.08.015

Yudko, E., Lozhkina, O., & Fouts, A. (2007). A comprehensive review of the psychometric prop-erties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32, 189–198. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002

258 Manuel Trachsel, Lara Ferrari, & Martin Grosse Holtforth

About the Authors

Manuel Trachsel is a postdoctoral research associate at the Institute of Biomedical Ethics, Center for Ethics of the University of Zurich, Switzerland. His main interests are in counselling and clini-cal psychology research, end-of-life issues such as decision-making capacity or patient directives, ethics of psychiatry and psychotherapy, and public mental health.

Lara Ferrari is a practicing psychologist at the clinic for rehabilitation ZHD in Davos-Clavadel, Switzerland. For the present study, she worked at the Department of Psychology, University of Bern, Switzerland. Her main research interests are in motivational factors in psychotherapy with focus on differences between cognitive and emotional elements.

Martin Grosse Holtforth is a SNSF research professor in the Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, Switzerland. His main interests are in psychotherapy research, affective disorders, and motivational and interpersonal factors in psychotherapy. His research was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF, No. PP00P1-123377/1).

Address correspondence to Manuel Trachsel, Institute of Biomedical Ethics, Center for Ethics of the University of Zurich, Pestalozzistrasse 24, CH-8032 Zürich, Switzerland; e-mail <manuel.