HAL Id: hal-03191988

https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03191988

Submitted on 8 Apr 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0

International License

Mario Tagliari, Carolina Levis, Bernardo Flores, Graziela Blanco, Carolina

Freitas, Juliano Bogoni, Ghislain Vieilledent, Nivaldo Peroni

To cite this version:

Mario Tagliari, Carolina Levis, Bernardo Flores, Graziela Blanco, Carolina Freitas, et al..

Collab-orative management as a way to enhance Araucaria Forest resilience. Perspectives in Ecology and

Conservation, 2021, 19 (2), pp.131-142. �10.1016/j.pecon.2021.03.002�. �hal-03191988�

SupportedbyBotic´arioGroupFoundationforNatureProtection

www.perspectecolconserv.com

Essays

and

Perspectives

Collaborative

management

as

a

way

to

enhance

Araucaria

Forest

resilience

Mario

M.

Tagliari

a,b,∗,

Carolina

Levis

a,

Bernardo

M.

Flores

a,

Graziela

D.

Blanco

a,

Carolina

T.

Freitas

c,

Juliano

A.

Bogoni

a,d,e,

Ghislain

Vieilledent

b,

Nivaldo

Peroni

aaProgramadePós-graduac¸ãoemEcologia,DepartamentodeZoologiaeEcologia,UniversidadeFederaldeSantaCatarina,Florianópolis,Brazil bCIRAD,UMRAMAP,AMAP,UnivMontpellier,CIRAD,CNRS,INRAE,IRD,F-34398Montpellier,France

cDivisãodeSensoriamentoRemoto,Coordenac¸ãodeObservac¸ãodaTerra,InstitutoNacionaldePesquisasEspaciais,SãoJosédosCampos,SP,Brazil dSchoolofEnvironmentalSciences,UniversityofEastAnglia,NorwichNR47TJ,UK

eUniversidadedeSãoPaulo,EscolaSuperiordeAgricultura“LuizdeQueiroz”,LaboratóriodeEcologia,ManejoeConservac¸ãodeFaunaSilvestre(LEMaC),Piracicaba,SãoPaulo,Brazil

h

i

g

h

l

i

g

h

t

s

•Top-down restrictive measures are thebasisofAraucariaForestSystem conservation

•Bottom-up collaborative manage-ment could favor keystone plant Araucariaangustifolia

•Top-downmodelhadnegative feed-backthatdampensthesystem limit-ingitsresilience

•Bottom-upmodelhadpositive feed-backexpandingthesystemand its generalresilience

•Collaborative management could maintain the Araucaria Forests Systeminthelongterm

g

r

a

p

h

i

c

a

l

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received7September2020 Accepted1March2021 Availableonlinexxx Keywords:AraucariaForestSystem Culturalkeystonespecies EcologicalKeystoneSpecies Ethnoecology

MixedOmbrophilousForest Participatoryconservation Resilience-thinking.

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Peopleandnatureinteractsincemillenniainforestsworldwide,butcurrentmanagementstrategies addressingtheseecosystemsoftenexcludelocalpeoplefromthedecision-makingprocess.Thistop-down approachisthecornerstoneofconservationinitiatives,particularlyinhighlythreatenedandfragmented forestedecosystems.Incontrast,collaborativemanagementinvolvingtheparticipationoflocal com-munitieshasincreasinglycontributedtoconservationeffortsglobally.Hereweaskhowcollaborative managementwouldcontributetotheconservationofathreatened,culturallyimportant,andkeystone treespecies.WeaddressthisquestionintheAraucariaForestSystem1(AFS)insouthernBrazil,wherethe mainconservationstrategyhasbeentop-downbasedonrestrictiveuse.Throughouttheentire distribu-tionofAFS,weinterviewed97smallholdersabouthowtheyuseandmanageAraucariaangustifoliatrees (araucaria).WeintegratedtheirTraditionalEcologicalKnowledge2(TEK)withaliteraturereviewabout theconservationstatusofAraucariaForeststoanalyzepotentialoutcomesoftwoalternativeconservation models:top-downwithrestrictiveuse,andbottom-upwithcollaborativemanagement.Weidentified thefeedbackmechanismsineachmodel,andhowtheydampenorself-reinforcedcriticalprocessesfor AFSresilience.Ourmodelsshowedthatatop-downstrategymaintainsforestcoverresilienttoillegal loggingbutatthecostoflosingTEK(underminingsocio-ecologicalresilience)andforestresilienceto

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:mario.tagliari@posgrad.ufsc.br(M.M.Tagliari).

1AraucariaForestSystem–AFS 2TraditionalEcologicalKnowledge–TEK

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2021.03.002

2530-0644/©2021Associac¸˜aoBrasileiradeCiˆenciaEcol ´ogicaeConservac¸˜ao.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Pleasecitethisarticleas:M.M.Tagliari,C.Levis,B.M.Floresetal.CollaborativemanagementasawaytoenhanceAraucariaForest resilience,PerspectivesinEcologyandConservation,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2021.03.002

otherexternaldisturbances,suchasclimatechange.Alternatively,abottom-upapproachbasedon suc-cessfulcollaborativemanagementschemesmayincreasethegeneralresilienceofAFS,whilepreserving TEK,thuscontributingtomaintainingtheentiresocial-ecologicalsystem.Ourfindingsindicatehowit isparamounttomaintainTEKtoconserveAFSinthelongtermthroughcollaborativemanagement.By includinglocalactorsinthegovernanceofAFS,itsresilienceisreinforced,promotingforestexpansion, maintenanceofTEK,andparticipatoryconservation.

INTRODUCTION

In the human-in-nature perspective, Social-Ecological Sys-tems(hereafterSES)aretheintegrationofhumansocietieswith ecosystemspromotingreciprocalfeedbacks,interdependence,and resilience(Folkeetal.,2010).TheresilienceofSESdependsontheir abilitytoadaptandremainwithinastabilitydomaininthefaceof disturbancesandexternalstressors,i.e.itdoesnotmovebeyond thresholdstoanalternativestateofequilibrium.Theadaptability ofSESenhancesitsresiliencebecauseitallowsthesystemtoadjust itselfinthefaceofadversities(Berkesetal.,2000).Forests world-wideareperfectexamplesofSESgiventhelong-terminteraction betweenforests,plants,andpeoples.Inthelargestconservedblock oftropicalforestintheworld–theAmazonforest,forinstance, multiplehumanmanagementpracticesovermillenniaincreased edibleplantdiversityandabundancewithinforestpatches, partic-ularlyneartoarchaeologicalsites,contributingtoenhancingfood securityandproduction(Levisetal.,2018).

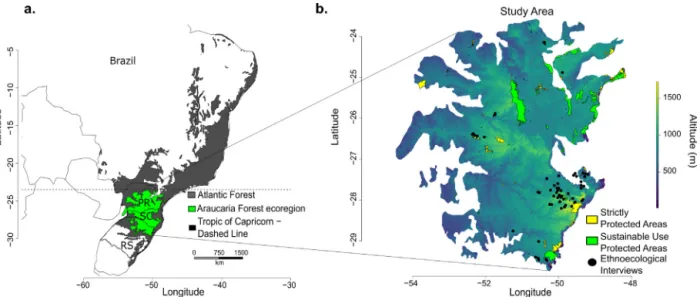

One of themost emblematicSES of thesubtropical Atlantic ForestistheAraucariaForestSystem(hereafterAFS),alsoknown asAraucariaMixedForest(Fig.1).First,becauseofitsdominant species,thecandelabra-aspecttreeAraucariaangustifolia(Bertol.) Kuntze, popularly known as araucaria, has a keystone role in ecosystemfunctioning,especiallyduetoitsnut-likeseed,known as‘pinhão’,whichstructurestheassociatevertebrateassemblage spatio-temporally(Bogonietal.,2020;Oliveira-Filhoetal.,2015).

Fig.1.SchemeoftheAraucariaForestSystem(adaptedfromBogonietal.,2020).1. TheAraucariaecologicalsystem.Thearaucaria(candelabratree)andthetypical ecologicalsystemunderitscanopy,suchasOcoteasp.–“Canela”;Ilexparaguariensis –“erva-mate”;Dicksoniasellowiana–“xaxim”;andAccasellowiana– “goiabeira-serrana”;andrepresentativefauna,suchastheMazamagouazoubira –“veado campeiro”;Pumaconcolor–“cougar”;Dasyproctaazarae–“cutia”;andCyanocorax caeruleus–“azureJaybird”.2.TheAraucariasocio-ecologicalsystem.We repre-sentedthecurrentscenarioofaraucariaremnants,especiallyinsouthernBrazil, wherelocalgroups(smallholders;indigenouspeoples)continuetomanagethe systemsincepre-Columbiantimes.

Second,becauseofitsancientconnectionwithIndigenouspeoples andlocalcommunities(IPLCs;Reisetal.,2014;Robinson etal., 2018). The araucaria wasand still is widelyused by local and indigenousgroupsdue totheconsumption ofpinhão(Robinson etal.,2018),withhighcaloriccontentthathelpscopingwiththe winterseasons(MelloandPeroni,2015).Araucariaseedsarepart ofintensetraditionaluse,management,andcommerceby small-holdersas wellas pinhão extractorsacrossdifferent regions of Southernand SoutheasternBrazil(Adanetal.,2016; Melloand Peroni,2015;Reisetal.,2014;Quinteiroetal.,2019;Tagliariand Peroni,2018;Zechinietal.,2018).Thecomprehensionthat cer-tainspeciesarecrucialtomaintainingdifferentcultures,suchas smallholdersorindigenousgroups,wasthebasistocreatetheterm “CulturalKeystoneSpecies”(GaribaldiandTurner,2004).Herewe useasimilarterm“culturallyimportantspecies”,followingFreitas etal.(2020),whichconsidersthespeciesoverridingroleinpeople’s culture,althoughnotnecessarilyindispensableforthesurvivalof a specificculture. However,if a culturally important species is extinctlocallyorhassufferedapopulationdecline,itwillstrictly influencelocalpeoples’subsistenceandspirituality(Freitasetal., 2020),aswellasthetransmissionofTraditionalEcological Knowl-edge(Berkes,2009).Yet,giventheintensecommercialexploitation ofA.angustifoliaduringthe20th centuryduetoitshigh-quality

wood(WendlingandZanette,2017),thespeciesiscurrently classi-fiedas“CriticallyEndangered”accordingtotheInternationalUnion forConservationofNature(IUCN,Thomas,2013).Sincethen,the Brazilian legislation forbids anyforms of araucaria logging and stimulatesthecreationandmaintenanceoftop-downprotective strategies.Asaresult,StrictlyProtectedareasarethecornerstoneof conservationstrategiesrelatedtoAraucariaForestSystems,which oftenexcludelocalandindigenouspeoplesfromparticipatingin biodiversityconservation(Zechinietal.,2018).

ProtectedAreas(PA)arewell-known refugesforbiodiversity andecosystems,particularlyintheAtlanticForest,wheremostof thesystempersistsinfragmentssurroundedbydenselyinhabited urbanandruralareas(ScaranoandCeotto,2015;Pachecoetal., 2018;Metzgeretal.,2019).AlthoughProtectedAreasencompass only4%to6%ofthecurrentAraucariaForestextent(Castroetal., 2019;Ribeiroetal.,2009), studiesevaluatingtheireffectiveness foraraucariaconservation(Castroetal.,2019)didnottakeinto accountanothermajorcategory:LegalReserves– aspecial pri-vatePA.ThesecompulsoryprivatePAshostalmostone-thirdofall remainingnativevegetationintheAtlanticForest(Metzgeretal., 2019).MostofthenativeAraucariaForestfragmentsoccurwithin smallfarms(BittencourtandSebbenn,2009).Consequently,itis undeniablethatlocalsmallholdersalsocontributetopreserving, willinglyorunwillingly,theAraucariaForests.However,previous ethnoecologicalsurveyshavesuggestedthattop-downstrategies (i.e.maintenance andcreationofStrictlyPublicProtectedAreas andPrivateProtectedAreas)maynegativelyimpactthe interac-tionsbetweensmallholdersandaraucariatrees(Adanetal.,2016;

TagliariandPeroni,2018).Forinstance,becauseremoving arau-cariatreesisillegal,somelandownersdonotdependonaraucaria’s resources,andthusarepronetoactivelypreventaraucaria’s nat-uralregenerationbyremovingitsseedlingsfromtheirproperties beforetheyreachmaturity(Adanetal.,2016;MelloandPeroni, 2015;Quinteiroetal.,2019;TagliariandPeroni,2018).Inthiscase,

livestockfarming(e.g.cattle),pastureorcropproductionfor sub-sistence,suchascornormanioc,usuallycompetewitharaucaria’s naturalregeneration,creatingahuman-plantbarrier(Adanetal., 2016;TagliariandPeroni,2018),wheresomelandownersstatethat theylosetherightstousetheirlandsbecauseofprotectedspecies (Quinteiroetal.,2019).

The araucaria case is therefore a conservation dilemma: people and natural resources interact since millennia, but cur-rent management strategies often exclude local people from thedecision-making process.Top-down strategiespreventlocal engagement in AraucariaForest conservation. Furthermore,the contributionoftop-downconservationstrategiestothelong-term conservationofnature,individuallyorglobally,stilllacks effective-ness(RodriguesandCazalis,2020),especiallyregardingpotential limitations totheprotectedareaperse,suchassocio-ecological resilienceorclimatechangeimpacts(Ferroetal.,2014).In con-trast,bottom-upstrategies,developedtogetherwithlocalhuman groupsthroughsharingdecisionsbetweengovernments, institu-tionsandlocalresourceusersaremorelikelytoproducebenefits forthesocial-ecologicalsystemasawhole,besidesstrengthening ecosystemresilience(Folkeetal.,2010;Bennettetal.,2016).

From the human-influenced expansion of Araucaria Forests during the past two millennia (Robinson et al., 2018) to the currenthighlyproductivesystems–suchasthe“faxinais”– under-neatharaucariacanopies,combinedwithIlexparaguariensis,locally knownas“yerba-mate”,atraditionaltea-likebeverage(Reisetal., 2018),humansarepartoftheAraucariaForestSystem(Reisetal., 2014).Themaintenanceoftraditionalpracticesconstitutesa gen-erational body of knowledge, beliefs, and practices, known as TraditionalEcologicalKnowledge(TEK;sensuBerkes,2009),which is fundamental for the persistence of social-ecological systems (Folkeetal.,2005).Inpractice,localsocietiesthatmanage ecosys-temsbasedonTEKcontributetomaintainingculturallyimportant species aswell ashuman cultures resilient by a positive feed-backmechanism(Cámara-Leretetal.,2019),andbydoingso,this processalsomaintainstheecosystemresilient,particularlyif man-agementaddressesakeystonespeciessuchasaraucaria(Bogoni etal.,2020).Consequently,acrucialsteptomaintainingthe Arau-cariaForestSystemresilientisbymanagingthefeedbackswithin itssystem(Biggsetal.,2012;Musavengane,2019;andseeFig.1

comparingtheAraucariaecologicalandsocio-ecologicalsystem). Feedbacksareinteractionsinwhichtheresultingeffecteither reinforces (positive) or dampens (negative) change (DeAngelis etal.,1986),influencingecosystemdynamics.Forinstance,when treesestablishinafire-pronesavannalandscape,theyreducefire spread, favoring forest expansion(vanNes et al. 2018). Partic-ularly, thepositive feedbacks,which self-reinforcechanges, are capable of triggeringcascadingeffects that push entire ecosys-temstoalternativestates(Estesetal.,2011;Schefferetal.,2001). Feedbacksdepicttheecologicalprocessesthatpromoteordegrade ecosystemresilienceandfunctioning;andhencearethekey mech-anismstobeincorporatedinecosystemmanagement(Briskeetal., 2006).Bothpositiveandnegativefeedbacksplaymajorrolesinthe self-organizationofsocial-ecologicalsystems.Therefore,to man-ageresilienceit isnecessarytounderstandthemostimportant feedbacksinthesystem,especiallyinvulnerableandthreatened ecosystems,suchasAraucariaForests(Briskeetal.,2006)where localpeopleswithdeepecologicalknowledgearelikelytobe crit-icalpartners.

Collaborativemanagement(co-management)impliesa partic-ipatory decision-making process in which the management of a natural resource is shared between users and other actors, suchasnational,andsubnationalgovernments,Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and/or local cooperatives (Berkes and Davidson-Hunt, 2006). Garibaldi and Turner (2004) argue that if local peopleidentifythemselves witha certainspecies, they

willhavea strongdesiretopreserveorrestoreit. Preservinga culturallyimportant species, therefore,may guarantee the par-ticipationof differentactors in species’ conservationprograms, andconsequentlybenefitboth thespecies,localpeople,andits surroundingecosystem (Cristancho and Vining, 2004;Garibaldi andTurner,2004;Nobleetal.,2016).Althoughstudiesaddressing co-managementschemesofculturallyimportantspeciesremain scarce in the literature due to the lack of ecological, social, andeconomicquantitativedata,thisbottom-upapproachseems promising to effectively engage local people into conservation actions(Freitasetal.,2020).Furthermore,co-managementmaybe partofresilience-thinkingbecauseitincorporatessomeofitsmain principles,accordingtoStockholmResilienceCentre(Stockholm ResilienceCentre,2013),suchasthemanagementoffeedbacksand theparticipationoflocalsinthegovernanceofthesocial-ecological system.

Applyingresilience-thinkingtolocalorregionalconservation issuesisstillagreatchallengebecausedecision-makersare usu-allyattached to traditional conservation strategies. In thecase ofAraucariaForestSystems,wherethemainconservation strat-egyisfocusedonatop-downconservationmodelwithrestrictive use,uncertaintiesstillexistwhetheracollaborativemanagement scheme could contribute to improving conservation outcomes. Herewe addressthis dilemmaina broadscalestudy toobtain detailedinformationonthestateoftheAraucariaForestSystem andunderstandhowbothtop-downandbottom-upconservation strategiesmayaffecttheresilienceofthissystem,includingits cul-turalandecologicaldimensions.First,basedonacomprehensive literaturereview,weanalyzefeedbacksandtheresulting dynam-icsoftwoalternativeconservationmodels:(1)top-downunder restrictiveuseand(2)bottom-upwithco-managementschemes. Second,based onevidence from97 semi-structured interviews withsmallholdersacrosstheAraucariaForest, weexploredthe risksandbenefitsofimplementingbothmodels.Bypresentingthe keyinteractionsandfeedbacksthatcouldstrengthenlocal engage-mentforaraucariaconservation,weexpecttoprovidea critical perspectiveformanagingandenhancingAraucariaForestSystem resilience.

METHODS

Studyarea

ThestudywasconductedinsouthernBrazil,acrosstheentire extentoftheAraucariaForestecoregion(Fig.2)andcoveringfour environments:Alluvial-onoldterracesassociatedwiththeriver system;Sub-montane-constitutingdisjunctionsataltitudesbelow 400m;Montane-locatedapproximatelybetween400and1000 mof altitude; and High Montane - comprising altitudes above 1000m(IBGE,2012).Thehighlandclimate,wheretheescarpment rises ∼1000m fromtheAtlantic Forest coastalplain,is humid mesothermic;temperature range between15-20◦C;and mean annualrainfallof 1500-2000mm (Robinson etal.,2018).Atits northeasternlimit,theecoregionexperiencesa tropicalclimate, andpersistsonlyatspecificcoldtemperaturesspotsathigher alti-tudes,suchasMantiqueirahills,attheHighRioPretoMicrobasin (Castroetal.,2019;Quinteiroetal.,2019).

Araucariapoliciesandlegislation

Severalcategoriesof protectedareas exist inBrazil: Conser-vationUnits,whicharedividedintoStrictlyProtectedAreasand SustainableUseAreas,andaremanagedbyfederal,state,or munici-paladministration,orthroughpartnershipswiththeprivatesector (DeMouraetal.,2009);PermanentPreservationAreasandLegal

Fig.2. (a)TheAtlanticForest(darkgray)withtheAraucariaForestecoregion(green)showingthethreeBrazilianstateswhichmainlyencompasstheecoregion:Paraná (PR),SantaCatarina(SC),andRioGrandedoSul(RS);(b)TheAraucariaForestaltitudemapandthedistributionofConservationUnits:Strictly(yellow)andSustainableUse ProtectedAreas(green);blackdotsrepresenttheoccurrenceof97ethnoecologicalinterviewsinthisstudy.WehighlightthatthreeinterviewsoccurredatSãoPaulostate (beyondtheAraucariaForestecoregion)atCunhamunicipality.

Reserves(privateprotectedareaswithinprivateproperties);and IndigenousLands(Pachecoetal.,2018).AccordingtotheBrazilian NationalSystemofConservationUnits(BRASIL,2000),the Sustain-ableUsecategoryisdividedintosevensub-categories,ofwhich two couldbespeciallytargetedtoTEKholdersintheAraucaria Forest System: Sustainable Development Reserves and Extrac-tiveReserves.Bothtypesofprotectedareasaimtosafeguardthe livelihoodsandculturesoftraditionalsocialgroups,aswellasto conservenatureanditsbiodiversity(DeMouraetal.,2009).Also, ExtractiveReservesrequiresomelevelofcommunityorganization andcooperation.

However,only10.6%oftheAtlanticForest(thusincludingthe AFS)isencompassedbyConservationUnits,mostlyofSustainable Use(75%).Furthermore,fromthe75%ofSustainableUse Conser-vationUnitscreatedwithintheAtlanticForest,only0.45%and0.62 %areclassifiedasSustainableDevelopmentReservesand Extrac-tiveReserves,respectively(Pachecoetal.,2018).Asaresult,few protectedareasintheAFSrecognizetheimportanceoftraditional peoples.Also,SustainableUseConservationUnitsaremanagedby thestategovernments,contrarytoStrictlyProtectedAreas– man-agedbyFederalgovernment–;andIndigenousLands,whichcover only0.72%oftheAFSarea(Pachecoetal.,2018),areadministered bytheFederalIndianAgency–FUNAI.Finally,almostone-thirdof AtlanticForest’sremainingnativevegetationoccurswithinLegal ReservesandPermanentPreservationAreas,inprivateproperties (Metzgeretal.,2019).Consequently,mostofthenativeAraucaria Forestoccurswithinsmallfarms(BittencourtandSebbenn,2009) anditisinspectedbymunicipal,state,andfederalagencies.Farmers whouseandmanagearaucaria’sresourcesareusuallylow-income smallholderswhodonotreceiveanyfinancialreturnfor conserv-ingforestedareas(OrellanaandVanclay,2018).Thelackofpolitical incentivesforAraucariaForest’sactivemanagementhasledto ille-galland-usepracticeswithinLegalReserves(OrellanaandVanclay, 2018).

TheBrazilianlegislationprohibitsanytypeofmanagementof araucaria timber(Lei daMata Atlântica or Atlantic Forest Law n◦11.428/2006;CONAMAResolutionn◦278/2001).However,the ParanáStaterecentlyapprovedanewLawn◦20.223/2020(Paraná OfficialDiary,2020),whichregulatestheplantingandexploitation ofAraucariaangustifolia,aimingtostimulatetimbermanagement programs.Thisnewlawdefinesandauthorizestimberexploitation inprivatepropertiesbeyondrestrictedareas(e.g.LegalReserves)

andareaswhereillegaldeforestationpreviouslyoccurredwithin theAtlanticForest.Yet,bypromotingonlytimberexploitation,a newmarketiscreatedforaraucaria,possiblystimulatinglocal pop-ulationsunderTEKsystemstoabandontheirancientpractices.This alternativeeconomicactivitybenefitslandownersbutmay under-minetheresilienceofthesocial-ecologicalsysteminthelong-term. Wehighlightthatlegislationshouldalsopromote,inthissense,the maintenanceofAraucariaForeststands(“FlorestaemPé”)beyond LegalReservesaspotentialareas forco-managementinitiatives viaPaymentforEnvironmentalServices(Tagliarietal.,2019). Sus-tainablepinhãoproductionandAraucariaForestreforestationare someoftheexistingprojectsunderthepossibilitiesofPaymentfor EnvironmentalServices(seeTagliarietal.,2019).

TheTraditionalEcologicalKnowledgeholdersinthecontextofthe study

Within the AFS different actors use, manage, and explore araucariaresources as opposingtoother social groups who do notusethem.DespitehumanmanagementsincePre-Columbian times,whereethnicgroupscultivatedpinhãoforsubsistenceand religiousness(Reisetal.,2014),duringthe20thcentury,a

combi-nationofagricultureexpansion,urbanization,andloggingchanged abruptlytheAFS(Rezendeetal.,2018;Ribeiroetal.,2009). Log-gingwasespeciallyrelevanttodecimate97%ofaraucariaremnant populationssincethebeginningofthe20thcentury(Enrightand

Hill,1995).Thisexploratoryscenarioculminatedinseveral restric-tivemeasures,suchasloggingprohibition,toprotectthe‘Critically Endangered’speciesfortheIUCNRedList(Thomasetal.,2013).

InAFS,manysocialgroupsuseandmanagearaucariaresources, butother social groupsdo not useormanage them. Thelatter reliesmainlyonlivestock, agriculture,and farmingsystems for commerce and subsistence, while smallholders who use Arau-cariaForestSystems dependeconomicallyonpinhãoextraction andotherassociatedcrops(e.g.,tobaccoandyerba-mate)fortheir livelihoods(Adanetal.,2016;Quinteiroetal.,2019;Tagliariand Peroni,2018).Thisinteractionbetweentraditionalsmallholders andAFSusuallysurpassesmorethanonegeneration,becausethey werebornandraisedinthesamefamily’sproperties(Adanetal., 2016),wheretheymightlearntheprocessesofcommunity orga-nizationandcooperation(Reisetal.,2018).Wethusdefinedthe specificgroupof smallholdersand pinhãoextractorsdistributed

acrossSouthernandSoutheasternBrazilasTraditionalEcological Knowledgeholdersinthecontextofthestudy.Thisattribute indi-catesknowledge,use,anddependencyonaraucariamanagement. Weproceededwiththeapplicationofthesemi-structured ques-tionnairewithTEKholders.Potentialparticipantswereindicated byinformalconversations withsmallholdersandpinhão extrac-torsineachmunicipalityandwithenvironmentalspecialists(such asmunicipalitiesorStateenvironmentsbureaus,professors,and universities).Weappliedthesnowballtechnique(Bernard,2006) to followthe semi-structuredinterviews, where participantsat theendoftheinterviewrecommendedpeopledirectlyinvolved inaraucariamanagement.Werecognizethatindigenouspeoples, such as Southern-Jê and Guarani, have shaped remnant forest composition in SouthernBrazil(Cruz etal.,2020), and arealso importantTEKholders.However,duetoethicalaspectsandlegal authorizationwedidnotincludeindigenouspeoplesinourstudy.

Datacollectionfromethnoecologicalinterviewsandtheliterature

Weconductedtwostrategiesfordatacollectionfromthestudy area:fieldworkandacomprehensiveliteraturereview.To quan-titatively assess the aspects of araucaria co-management with local smallholders and araucaria nut-like seeds extractors, we first identified key-regionsinSouthern and SoutheasternBrazil where pinhão use, commerce, and management are commonly described (e.g.regionalpinhãoparties,suchas“FestadoPinhão” at Lages and Cunha municipalities; informal pinhão commerce along estate highways; andpublishedliterature). We thus con-ducted97semi-structuredinterviewswithkey-informantsinfour Brazilian States:Paraná,SantaCatarina,Rio GrandedoSul,and São Paulo (surroundings of Mantiqueira hills at Cunha munic-ipality), covering 14 municipalities between March 2018 and January2019(Fig.2).Priortotheapplicationofthequestionnaire totheparticipants,weobtainedinterviewees’consentfollowing the codeof ethics ofthe InternationalSociety of Ethnobiology. Our study was approved by the ethics committee of the Fed-eralUniversityofSantaCatarina(CAEE:86394518.0.0000.0121). Thesemi-structuredinterviewprotocoladdressedthreemain top-ics:(i)historicalmanagementandsocioeconomicfactors;(ii)the araucariaecologyandethnoecologyaspects;(iii)interviewees’ per-spectivesaboutclimatechangethreatsforaraucaria(seeTable1

andTableS1).Toassessthelocalknowledgeandstate-of-the-artof araucariaco-managementforthisstudy,weselectedspecific open-endedquestionsthroughthequestionnairesuchas(i)“Whatisthe importanceofpinhãotoyourproperty?”;(ii)“Whatarethecauses behindtheexpansion/retractioninaraucaria’spopulation?”;(iii) “How muchpinhão (kg)hasbeengatheredinyour propertyon average?”; (iv)“How many ethnovarieties ofaraucaria canyou identifyinthelandscape?”;(v)Whatarethedifferencesinsize, color, taste,ripeningperiod oftheethnovarieties? (vi)“Doyou practiceanymanagementduringpinhãogathering?”.Finally,we compiledthisdatatoproduceatheoreticalframeworkthatcould supportpotentialcollaborativemanagementarrangements.Pilot interviewsprecededdatacollectiontorefinethesemi-structured questionnaireinJanuaryandFebruary2018.

Thecomprehensiveliteraturereviewwasperformedbyusing “WebofScience”searchengine,followingBogonietal.(2020)and

Monta ˜no-Centellasetal.(2020).Wesearchedforspecifictermsin theabstractsofarticlespublishedbetween2010and-2020: “arau-caria*”and“angustifolia*”and“conservation*”or“cultural*”.Both terms“conservation”and“cultural”weredefinedbecausetheyare commonlyemployedinscientificpublicationstargetingaraucaria conservationandethnoecologicalstudies.Wefound70scientific peer-reviewedarticles(TableS2)andincludedafewnon-indexed references,suchasPh.D.theses.First,wecross-checkedthe litera-turereviewinformationwithourfieldworkdata.Second,weused

theselectedpeer-reviewedarticlestoproposeaschematic frame-work(TableS3)basedontwoalternativeconservationmodels. Top-downversusbottom-upconservationschemesforthe AraucariaForestSystem

Tocreatethealternativeconservationmodels,wefollowedthe frameworkofcomplexadaptivesystems,whichunderstandsthat social-ecologicalsystemsaredrivenbyexternal factors,suchas policiesandclimatechange,aswellasbyinternalfeedbacks(Berkes etal.,2000;Folkeetal.,2010).Wefirstidentified‘ForestCover’as themainstatevariabledefiningtheecosystemfromthe conserva-tionandamoreholisticperspective.Statevariablesaremeantto representtheoverallstateofasystemandmayindicatethe exis-tenceofalternativestablestates(Folkeetal.2010).Wethendefined twovariablesrepresentingdriversunderatop-downconceptual framework:‘Deforestationandresourceoverexploitation’and‘Forest Protection’.Forthebottom-upconceptualframework,weuseda secondstatevariable‘TraditionalEcologicalKnowledge-TEK’,and ‘Collaborativemanagement’asadriver.Thesevariableswere pre-viouslyidentifiedasthemostimportantforAFSdynamicsinour literaturereviewandrepresentcriticalelementsineach conser-vationmodel (TableS3). For instance,oneof themaingoalsof protectedareasishaltingbiodiversityloss,suchasdeforestation (Rodrigues and Cazalis, 2020).In Brazil, both federal and state governmentsareresponsiblefortop-downconservationmodels, especiallyintheformofProtectedAreas,suchasStrictlyProtected andSustainableUseConservationUnits,orLegalReserves(Metzger etal.,2019; Pachecoet al.,2018).Incontrast,we defined‘TEK’ asanotherstatevariableunderabottom-upconservationmodel becausearaucariacanbeclassifiedasaCulturallyImportantSpecies thatdependon‘TEK’topersist(Adanetal.,2016;Quinteiroetal., 2019;Reisetal.,2014;TagliariandPeroni,2018).Bothconceptual modelssuggestthatalternativefeedbackloopsproducealternative dynamicsofAraucariaForestSystems.Followingthesetwo mod-els,weproposethemainthreats,strategies,andactorsinvolved,as wellasthebenefitsandrisksofbottom-upandtop-down conser-vationstrategies(inspiredbyFreitasetal.,2020).Finally,alsobased onthepublishedliteratureandfielddatafromthisstudythat indi-catesthebottom-upschemeasthemostpromisingformaintaining AFSinthefuture,weevaluatethepossibilitiesforimplementing collaborativemanagementsthatcontributetostrengthening envi-ronmentalgovernanceintheregion.

RESULTS

Socio-economicbenefitsandco-managementpossibilitiesfor araucariaresources

According to our interviews, local smallholders and pinhão extractorsareinvolvedintheextractionofaraucariaseeds (pin-hão),foratleast3.5generations(mean=3.8generations,where eachgenerationrepresents25yearsonaverage).Thereare fam-ilygroupswhohavebeenlivinginthesameregionfor130-150 years(35familygroupsor36%).Thislonginteractionbetweenthe participantswitharaucaria’sresourcesbringslargesocio-economic benefitstolocalfamilies.Amongthe97participants,63(65%)told thatsomehowpinhãotradeinfluencestheirmonthlyincomes,from R$1000toR$2500permonth,i.e.US$490toUS$1235atthetime, in2018(WBI,2020)or∼1to2.3Brazilianminimumwagesin2018. Furthermore,17participantsamongthose63whobenefitedfrom tradeaffirmedthatatleast50%oftheirannualgrossincomecomes frompinhãotrade.Pinhãotradeisamongthethreemainsourcesof incomefor30%ofallparticipants.Livestockandothercropswere commonlycited bysmallholdersas alternativeincome sources, togetherwithpinhãotrade,suchasbeans,corn,yerbamate,and tobacco.Theamountofpinhãogatheredperseasonbythe

partici-Table1

CollaborativemanagementofAraucariaangustifoliaanditsmainchallengesforimplementation,considering:(i)Implications;(ii)potentialbenefits:cultural, ecological,social-economic,andinstitutionalarrangements,aswellaspotentialrisks;and(iii)theliteraturereviewandinterviews’datatosustainourmodel assumptions(inspiredbyFreitasetal.,2020).Co-managementforaraucariaconsidersmostlytheuse,management,andconsumptionofitsnut-likeseed,although othermanagementsystemsexist,suchaslegaltimberproduction,reforestation,maintenanceofprivatenativeremnants,andpaymentforenvironmentalservices.We usedinformationavailableintheliteraturetocharacterizethearaucariaco-managementframework.Here,wedescribeindetailtherisksandbenefitsofthearaucaria co-management.

Araucariaangustifoliaco-management

Implications Potentialbenefits Reference

Cultural

Participants’engagement(localpeople) Increase Thisstudy(questionsA3;A3a;A7a;B2;B4;seeTableS1)

Communityinvolvement Increase Thisstudy(questionsA3a;A7a;seeTableS1);Adanetal.,

2016

Societalrecognitionandoutreach Increase Freitasetal.,2020

Strengtheningofculturalvaluesand TraditionalEcologicalKnowledge

Increase Reisetal.,2014;MelloandPeroni,2015;Adanetal.,2016; TagliariandPeroni2018

Maintenanceofaraucariaethnovarieties Increase Thisstudy(questionsB4;B5;B6;B13;B14b;B14c;B15; seeTableS1);Adanetal.,2016;TagliariandPeroni2018; Quinteiroetal.,2019

Ecological

Speciesabundance Increase Thisstudy(questionsA7;A7a;B1;B13;B13b;seeTable

S1);Sühsetal.,2018 AraucariaForestecosystemconservationand

recovery

Increasegeneralresiliencetohuman andnaturaldisturbances

Folkeetal.,2010

Ecologicalinteractions Increase Bogonietal.,2020

Nut-likeseedproduction Increase Thisstudy(questionsA3;A3a;B2;seeTableS1);Robinson

etal.,2018 Connectivitybetweenaraucaria’sremnant

populations

Maintenanceofaraucariaremnants throughdifferentProtectedAreas

Tagliarietal.,inreview

Species’geneticdiversity Increase Adanetal.,2016

Contributiontofoodsecurity Increase Thisstudy(questionsA3a;B2.B3;seeTableS1);Reisetal., 2018

Social-economic

Societalrecognitionandoutreach Increase Reisetal.,2014

Stakeholders’participation Possible Tagliarietal.,2019

Possibilityoffinancialself-sustainability Possible Tagliarietal.,2019

Incomedistributionwithinthecommunity Increase Thisstudy(questionsA3;A3a;A7a;seeTableS1)

‘Conservation-by-use’possibility Possible Reisetal.,2018

Historicalcommercialoverpressure Possible Ribeiroetal.,2009;MelloandPeroni,2015;Schneider etal.,2018

Valueforsustainablearaucariaresourcesuse Possible Tagliarietal.,2019 Opportunitiesforinstitutionalarrangements

Surveillance/enforcement Possiblyincrease Freitasetal.,2020

PaymentforEnvironmentalServicesasa compensationstrategy

Possible Tagliarietal.,2019

Mainstimulitolocalengagement Cultural/moral/ethicaspects;financial compensation

Thisstudy(questionsA3a;A7a;seeTableS1);Tagliari etal.,2019

Rulesfocusingonhabitatprotection Increase2 Seefootnote

Legalpermissiontotradethetargetspecies Thereisnolegalpermission3 Seefootnote

Co-managementwiththeconsentof environmentalagencies(suchastimber productionquotasforsmallholdersuseand management)

Possible OrellanaandVanclay,2018

Financialcompensationforsupporting araucaria’sremnantsbesidesLegalReserves andPermanentPreservationAreas

Increase Tagliarietal.,2019

Potentialrisks

Reducedinspectionofenvironmentalagencies Possible Freitasetal.,2020

Historicalcommercialoverpressure High Ribeiroetal.,2009;MelloandPeroni,2015;Schneider

etal.,2018 Currentillegalharvestpressure(i.e.

deforestationandlogging)

High Adanetal.,2016;Schneideretal.,2018;Tagliariand

Peroni2018;Quinteiroetal.,2019

1SouthernBrazilianStatescreatedtheirspecificlawsforthebeginningsofpinhãocommerce(i.e.RioGrandedoSulstartsfromApril15th;SantaCatarinaandParanáfrom

April1st).Thisdecisionperiodisduetothemaintenanceoflocalfauna,especiallytheparrots“Papagaio-charão”and“Papagaio-do-peito-roxo”(AmazonapetreiandAmazona

vinacea,respectively),besidessmallrodentsas“cutia”(Dasyproctaazarae),andmammalsas“veado”(Mazamagouazoubira;LobandVieira,2008).Oncetheextractionseason beginsnolawsregulatetheamountofpinhão(kgortonne)collectedduringtheseasonperiod.

2MataAtlânticaLawn◦11.428/2006–prohibitsnativespeciesmanagementinnaturalforests.CONAMAResolutionN◦278/2001(BRASIL,2006;CONAMA-ConselhoNacional

doMeioAmbiente,2001).

3AccordingtoBrazilianlegislation,araucarianativepopulationsareprohibitedfortimberharvestingoncethespeciesis‘CriticallyEndangered’(Thomas,2013).However,

plantedaraucariaharvestingfollowingamanagementplanregisteredandapprovedbyenvironmentalagenciesisallowed,butbureaucracyandlackofflexibilityprevent thismanagementplan(WendlingandZanette,2017).

pantswasclassifiedinthreecategories:(i)upto1000kg(40%or39 participants);(ii)from1000to10,000kg(47.5%or46participants); and(iii)above10,000kg(11.5%or11participants).Formost partic-ipants,however,theextractivismofaraucariaseedsdidnotstand inpracticeaspartofaco-managementscheme,despiteinvolving localmanagementandtrade.Onlyonesmallholderdeclaredthat thepinhãotradeinhisproprietywascertifiedbyanNGOunder a co-managementscheme.Thesameparticipantis alsogranted withone projectinvolvingPaymentfor EnvironmentalServices (PES)toconservearaucariaremnantsinareasbeyondtheLegal Reservewithinhisproperty.Fourparticipantsusetheirproperties fortourismpurposesinvolvingaraucaria(i.e.ecotourism).Among thesefourinterviewees,twoofthemhaveco-management part-nerships withinternationalstakeholders and NGOs topromote sustainabletourismintheAraucariaForestregion.

TraditionalEcologicalKnowledgeaboutaraucariamanagement andethnovarieties

Sixty-oneparticipants(63%) saidthat AraucariaForestcover aroundtheproperty(ifapplicable)expandedinthelastdecades dueto:(i)thecreationofProtectedAreas(N=33);(ii)restrictive legislation(N=18),consequentlysawmills’interdictionforusing nativeandthreatenedspecies(N=5);(iii)community participa-tioninreforestation(N=9);and(iv)increaseddispersalbylocal fauna(N=6).Theremaining35participantsinformedthat Arau-cariaForestcoverhasbeendecreasing,mainlydueto:(i)seedling suppression,knownas“roc¸adas”(N=22);or(ii)illegallogging(N= 18).Wealsofoundintervieweesdescribingnegativeimpactsfrom (iii)pesticides(N=1);(iv)severelegislation(N=1);and(v) eco-logicalcompetitionwithPinussp.(N=1).Weidentified23local namesfortypes(ethnovarieties)basedon320citationsfromall participants.Theseethnovarietiesweredescribedbylocalpeople (i.e.smallholdersand/orpinhãoextractors)accordingtothe ripen-ingperiodsofpinhãoseedsproducedbyfemalearaucarias.Thefive most-cited localvarietieswere: (i)“Macaco”(N=81 citations); (ii)“Cajuvá”(N=80citations);(iii)“Comum”(N=48 citations); (iv)“DoCedo”(N=31 citations);and(v)“25deMarc¸o”(N=16 citations).Mostparticipantscitedthreeethnovarieties(52.5%)and ∼25%ofthemmentionedfourdifferentethnovarieties. Ethnovari-etiesdescribedbytheparticipantsweresaidtodevelopindifferent momentsduringtheyearindicatingpinhãoproductionthroughout theentireyear.

Socio-ecologicalbenefitsandrisksofbothalternativemodelsfor AraucariaForestSystems

Thebenefitsandrisksofadoptinga top-downorbottom-up strategy for Araucaria Forest System involve different ecologi-cal, social, economic, and culturaldimensions according tothe interviewsandtheliteraturereview(Fig.3; Table1).Top-down conservationmodelspromotebenefitstowardsthetargetspecies (inthiscasearaucaria)anditssurroundingfaunaandflora;the bio-diversitymaintenance;andprovidesecosystemservices,suchas provisioning(foodwithpinhãoproduction);support(pollination; nutrient cycling); regulation (carbon sequestration; alternative foodresourceforAraucariaForestfauna);andcultural(heritage value,regionalsymbols,ecotourism).Biodiversityandecosystem servicesmaybeindirectlyenhancedbythismodel,thusfavoring humanwell-being.However,restrictivetop-downmodels(such asStrictlyProtectedareasorexcessiverestrictivelegislation)may create:(i)barriersbetweenhumangroupsandthetarget preser-vationpriority;(ii)thelossofTEKandsocio-ecologicalresilience; (iii)fragilitytoexternalstressors,suchasclimatechange.

Themostpromisingbenefitsofbottom-upco-managementare: (i)sustainablepinhãotrade;(ii)sustainabletourism;(iii)Payment

forEnvironmentalServicesprograms;(iv)potentialconservationof AraucariaForestremnantswithinruralproperties;and(v) possi-blerecoveryandexpansionofAraucariaForests.Byincorporating theseinitiativeswithlocalpeople,theymayalsostimulatelocal engagementinsurveillance,conservation,andmaintenanceof bio-diversity.Thesebenefitsareinterconnectedbetweenlocalgroups andAraucariaForest,enhancingthelong-termresilienceand con-servationof theAraucaria ForestSystem.The risksof adopting bottom-upco-managementschemesforAraucariaForestSystems mayberelatedto:(i)psychologicalbarriersbetweenlocalpeople andenvironmentalagenciesduetothememoryofhistorical exces-siveenforcement–anexampleisapracticeknownas‘roc¸adas’, whichconsistsintheremovalofaraucariajuvenilestoavoidfuture legalrestrictionsonlanduse(Adanetal.,2016)–;(ii)thepotential overexploitationofaraucariaresourceswithinprivateareas,such asillegalcutting,timberexploitation,anddeforestation(Orellana andVanclay,2018);and(iii)possiblepoorcommunicationbetween localpeople, stakeholders, and environmentalagencies (Freitas etal.,2020).However,negativeco-managementexperiencesare morelikelytobecorrectedbypositiveinnovationsfromlocal peo-ples,sincetheirTEKandtheintrinsicbodyofknowledgethrough generations might allow them tomaintain feedbacks stronger, respondingfastertoexternalchanges,enhancingadaptability,and transformabilityofthesystem(asshownbyBerkesetal.,2000).

TwoalternativemodelsofAraucariaForestconservation: top-downwithrestrictiveuse,andbottom-upwith co-managementschemes

TwoalternativeconservationmodelsofAraucariaSESshowed different feedbacks and dynamics (Fig. 4; Table S3). The top-downrestrictiveschemecontributedtoincreasingforestresilience tohumandisturbances.Thishappensbecause‘deforestation’and ‘resource overexploitation’ lead to more enforcement and ‘forest protection’(restrictive measures) by managerstomaintain ‘for-est cover’. With more forest cover, resource overexploitation is expected to decrease, relative to the overall forest abundance, reducing theperceptions of overexploitationby managers, and leadingtolessrestrictivemeasures.Inthissense,weidentifiedthat restrictivemeasuresarecreatedasaresponsetohuman distur-bances(i.e.deforestationorresourceoverexploitation),resultingin anegativefeedbackloopthatdampensforestloss(seeFig.4)and partlymaintainstheconservationpurpose.Thetop-downscheme, however,mightnotguaranteeresiliencefortheentiresystemto othertypesofdisturbances,suchasextremeweathereventsdue toclimatechange,mainlybecausethelossoftraditional manage-mentmayreducethefunctionaldiversityofaraucariapopulations (Table1;Adanetal.,2016),andconsequentlytheforests’ adap-tivecapacity in the face of unexpectedevents (Elmqvist et al., 2003).Hence,thetop-downschemecompletelydisruptsthe his-toricalhuman-plantinteractionoftheAFSthatmadethissystem resilient for millennia. In contrast, thebottom-up conservation schemeshoweda distinctfeedback loop(Fig.4).Inthis case, a self-reinforcing(positive)feedbackloopemerged inthesystem, because‘TraditionalEcologicalKnowledge (TEK)’provides oppor-tunitiesfor‘collaborativemanagement’,whichallows‘forestcover’ topersistand potentially expand.With more forestcover, TEK is expectedtoexpand as well,promoting co-managementthat enhancesthegeneralecologicalresilienceoftheforest(toallsorts ofunexpecteddisturbances),becauselocalmanagementenhances thefunctionaldiversityof araucariapopulations(Table1;Adan etal.,2016).Thepositivefeedbackloopweidentifiedhastherefore thepotentialtostrengthentheecologicalresilienceofthewhole AraucariaSESandtopromotethesystem’sexpansionbeyondits currentlimits.

Fig.3.Flowchartofbenefitsandrisks(inspiredbyFreitasetal.,2020)ofdistinctconservationstrategies.Arrowsrepresenttheexpectedoutcomesofeverystepinthe flowcharts.1.Top-downstrategiesforAraucariaangustifolia(araucaria)preservation.Asthemainconservationstrategy,top-downpolicies,suchasthemaintenance orcreationofStrictlyProtected,neglectthehistoricalhuman-plantinteractionintheAraucariaForestSystem.Thesepolicies(1)maintaintheecologicalresilienceofthe forestecosystemandprovideecosystemservices(indirectbenefitsforhumangroups),but(2)mayfailduetobarriersupontraditionalpeoplewhouse,manage,and promotethesocio-ecologicalresilienceofthesystem,leadingtothelossofTEK;increasesinoverexploitationanddeforestationpressures;andreducedresiliencetoexternal stressors,suchasclimatechange,pathogens,andinvasivespecies.2.Bottom-upconservationinitiativesforaraucariaasaCulturalImportantSpecies(CIS)under co-management.Becausearaucariaisaculturallyimportantspeciesforlocalpeople,(1)theywilllikelyfeelstimulatedtoengageinco-managementinitiativesfocusingonthis species;(2)weshouldconsequentlyexpecthighcomplianceandlocalsurveillancelocalpeople;(3)thishuman-plantinteractionwhichwilllikelyfavortheconservation ofaraucariapopulationsand(4)benefitotherspeciesco-existingintheAraucariaForest,andtheecosystemasawhole.Therearebothbenefitsandrisksthatcouldbe expectedfromthisco-managementapproach.Therisks(5)ofthisinitiativemayberelatedtothepotentialfragilearrangementbetweenlocalpeopleandinstitutions (e.g.environmentalagencies,Non-GovernmentalOrganizations,privatesectorand/orstakeholders);inadequatesurveillanceoftheco-managementinitiative;and/orthe excessiveinstitutionalenforcement.Anotherriskistheincreaseofillegalcutting(i.e.resources’overexploitation,juveniles’suppression,and/ornon-sustainabletimber production).Suchnegativeconsequences(6)willpossiblyaffectecological(i.e.ecosystemdegradation),economic(i.e.lesspinhãotrade,lossofpaymentsorcompensations forenvironmentalservices;lessecotourism),andcultural(detachmentfromlocalpeople,lossoftraditionalknowledge)aspects.Apotentialwaytocircumventthoseproblems (e.g.increaseddeforestation)couldbe(7)alternativeco-managementinitiativestargetingforestrecoveryorrecuperationofdegradedareas(dashedarrow).Thepositive scenario(8),however,couldbringecological(maintenanceoftheecosystem);economic(viaPaymentforEnvironmentalServices,sustainablepinhãotrade,ecotourism);social andculturalbenefits(i.e.localengagement;maintenanceoftheTraditionalEcologicalKnowledgeofaraucariaanditsethnovarieties,andaraucariaresources’management). Allofthesepositiveconsequencesareinterconnected(9)andcouldfinallyallowamoreresilientandcyclicalstablestate(10)oftheentireeco-socio-economicsystemof AraucariaForests,besidesactingasanalternativetothemainstreamconservationstrategy(i.e.themaintenanceofexclusionaryProtectedAreasviatop-downpolicies).

Fig.4. Theschematictop-downandbottom-upconservationmodelsofAraucaria Forestsystemsareself-organizedincontrastingways,withdifferentfeedbacks. Solidlinesrepresentpositive/negativeeffects.Cycleschemes(grayshaded) rep-resent thefeedback loop,itsdirection (i.e.counter-clockwise) andits result: negative/buffereffectorpositive/self-reinforcingstate.1.Schematic representa-tionoftheinteractionsinvolvedintop-downpolicies,suchasStrictlyProtected Areas.Thisschemeimprovesonlyaportionofthetargetecosystem,neglecting potentialsocio-ecologicalinteractions(i.e.localpeople).Thisclassical conserva-tionistapproachcreatesabufferfeedback,i.e.itsustainsthecurrentstate.Excessive resourceexploitationordeforestationgeneratesprotectivemeasuresthatbenefit forestcover.However,aforestprotectedbytop-downmeasuresmaynotcompletely avoidthesedisturbances(e.g.deforestationandoverexploitation)andmightnot contributetootherexternalstressors,suchasclimatechange.Theyalsoreducethe benefitsforlocalpeoples,whoarevirtuallyexcludedfromthesystem.2.Schematic representationoftheinteractionsproducedbybottom-uppolicies. Indepen-dentlyfromrestrictivemeasures,thisschematicsocio-ecologicalsystemindicates anincreaseinthesystem’sresilience,duetoaself-reinforcingmechanismthat pro-motesaraucariaforestexpansion.Hence,byincorporatingTEKandco-management initiatives,thisschemeincreasesthegeneralresilienceofthesocial-ecological sys-tem.Note:ourconceptualmodelisnotmutuallyexclusive,bothtop-downand bottom-upstrategiesco-occurwithinAFSandcontributetomaintainingnative forestremnants.

DISCUSSION

OurfindingsrevealthatAraucariaForestSystemsinsouthern SouthAmericamightbelosingresilienceduetoalong-term top-downrestrictivemanagementschemethatmakesthesystemless adapted toall sortsof disturbances. Partly becausethis social-ecologicalsystemdependsonTEK,whichiscurrentlybeinglost as restrictive measuresdisrupt anancient human-nature inter-action.However,ourstudyrevealsanalternativeperspectiveon howtomaintainthegeneralresilienceofAraucariaForestSystems bystimulatingTEKproduction throughacollaborative manage-ment scheme.Wehave shownthat bottom-upco-management mayself-reinforceandbenefittheresilienceofaraucariaforestsand thusprovideapossiblesolutionfortheconservationdilemmathat hasbeenthreateningthisecosystem.Co-managementinitiatives mayeffectivelyincorporatetheprinciplesofresilience-thinking: management of feedbacks;maintenance of ecologicaldiversity; and broad participation of different actors (Folke et al., 2005,

2010).Strengtheninglocalactorsandtheirrolesingovernanceis

particularlyeffectivewhencomparedtorestrictiveand exclusion-aryconservationstrategies,suchasStrictlyProtectedAreaswith excessivetop-downenforcement.Webelieveourfindingsofferan opportunitytogenerateoptimisticbottom-uppathwaystowards anefficient,inclusive,andwell-articulatedconservationstrategy thatcouldself-reinforcestheresilienceoftheAraucariaForest Sys-tem.Byshiftingfromatop-downtoabottom-upco-management schemethatincludeslocalactorstogetherwithexistinginstitutions inthegovernanceprocess,theAFScoulddeveloptransformability andadaptability,furtherenhancingitssocial-ecologicalresilience (seeFolkeetal.,2005,2010;Biggsetal.,2012;Bennetetal.,2016). Becausesimilarecosystemswithculturallyimportantplantspecies arealsoundergoingthesameconservationdilemma,webelieve thatourfindingscouldbeusefulinothercontexts.Such innova-tiveandcollaborativesystemscouldpotentiallydeveloptobecome anotherglobalbrightspotexample,wherethenaturalandcultural capitalsarepreservedbybottom-uparrangements,inspiring soci-etiesworldwide(Bennettetal.,2016).

Althoughthetop-downstrategyhasprovenusefultomaintain araucaria forestsresilient to logging and other human degrad-ingactivitiesviaa negativefeedbackloop(Fig.4), this strategy hasnotbeensufficienttomaintaintheentiresysteminthelong run.Sincethehistoricalloggingoverexploitationinthe19th

cen-tury,andlater,theinclusionofaraucariaas“CriticallyEndangered” byIUCN(Thomasetal.,2013),thecreation/maintenanceof top-downProtectedAreasbecamethecornerstoneofitsconservation (Zechinietal.2018).ProtectedAreasaimtocurbanthropogenic disturbancesinnaturalecosystemsandhaltthelossofbiodiversity (Geldmannetal.,2019;Wiensetal.,2011),butmightfailtoprevent theextinctionofseveralspeciesinthelong-termduetoclimate change(Ferroetal.,2014),aswelltoanthropogenicdisturbances (e.g.,invasivespecies;poaching;landuse;lossofgeneticdiversity;

Laurance,2013);andtopotentiallypromotesocio-economic bene-fits(givenpoorgovernanceorregionalconflicts;Lauranceetal., 2012).Insouthern Brazil,traditionallandmanagement systems protectthegeneticdiversityofaraucariapopulations,thus con-tributingtothespeciesconservationandthesafeguardingofthe SES(Reisetal.,2014;MelloandPeroni,2015;Adanetal.,2016;

Zechinietal.,2018).Asaresult,top-downconservationstrategies areinsufficienttoconserveaculturallandscape(MelloandPeroni, 2015)becauseitreducesthesystems’adaptivecapacity,aswellas theparticipationofdifferentactorsinenvironmentalgovernance; allrequisitesforsocial-ecologicalresilience(Folkeetal.,2010;de Vosetal.,2016;Musavengane,2019).

Thefeedbackdynamicsofabottom-upco-management strat-egyhasthepotentialtoenhancethesystemic resilienceofAFS aswellasother Social-EcologicalSystems,becauseit promotes adaptability through TEK production (Berkes et al., 2000), and becauseitrecognizesthattransformabilityintoparticipatory gov-ernance is necessary, as human-nature has shaped Araucaria Forest landscapes over millennia (Reiset al., 2014).Moreover, itenhancesconnectivity,becausedifferentactorsareconnected in the system (e.g. NGOs; stakeholders; local groups; govern-ments).Also,itretainsfunctionalredundancy,i.e.ifoneactoris removedfromthesystemthesystemitselfremains resilientto thedisturbancebecauseofthe differentplayerswiththesame functions.We alsofoundsupportforthenotionthata bottom-upco-managementstrategycanenhancetheresilienceofAFSnot onlytohumandisturbancesbutalsotodifferentkindsofthreats, suchasextremeweatherevents(Folkeetal.,2010).Onereasonis thatco-managementincreasesthefunctionaldiversityofaraucaria treepopulations,especially due touseand management (Adan etal.,2016;TagliariandPeroni,2018;Quinteiroetal.,2019),and consequentlytheadaptive capacity oftheforest tounexpected disturbances(Elmqvistetal.,2003).Asaresult,co-management generatesapositivefeedbackloopthatstrengthensforestresilience

aswellassocioculturalresilience.TheAraucariaForestisan exam-pleofa self-reinforcingsystem,where inthepasthuman-plant interaction wasresponsiblefor theforestexpansionbeyondits climaticniche(Robinsonetal.,2018).

Sühs etal.(2018)showedthatthemaintenance ofaraucaria maturetreestogetherwithtraditionallandmanagementpromotes Araucaria Forest expansion, saplingspecies richness and abun-dance,togetherwiththepreservation ofgrasslandsinsouthern Brazil.Theauthorsarguethatamaximalregionaldiversityofthe plant communitiescan beachieved bya balancebetween pre-servedforest areasandtraditional managementpractices (Sühs etal.,2018).Reisetal.(2018)alsoshowedthatmanagement sys-temswithintheAraucariaForest,suchasthe“caívas”and“faxinais”, maintainlandscapeswithproductiveforestfragments,thus favor-ingaraucaria conservationandhumanwell-being.Furthermore, thissystemhighlydependsontheculturalandeconomic valua-tionofpinhão(Reisetal.,2018).Theopportunitytoincreaseprofits fromaraucariaremnantscouldassurethelong-term sustainabil-ityofco-managementinitiatives(PomeroyandBerkes,1997).The broaderparticipationofdifferentactorsinenvironmental gover-nanceiswithinthebasisofco-managementinitiatives(seeFreitas etal.,2020).Hence,co-managementinitiativestargetingthe Arau-cariaangustifoliacanrepresentavaluablesolutionfortheongoing conservationdilemma.

CONCLUSION

Re-evaluatingthearaucariaconservationdilemma

Ourbottom-upconceptualmodelwasdirectlylinkedtoa spe-cific socialgroup:thesmallholdersalongtheAFS,whopossibly encompassthemajorityofAFSnativeremnantsundertheirLegal Reservesprotectedareas(BittencourtandSebbenn,2009;Metzger etal.,2019).Othersocialgroupsstillinfluenceandmanagethis sys-tem,suchasindigenouspeoples,whowereco-responsibleforthe transformationandexpansionofthesysteminthepast(Robinson et al., 2018), and remain as essential partners for developing a co-management scheme. Although we could not incorporate indigenous peoples inouranalysis,theyalsoapplytoour con-ceptualmodelasmajorTEKholders.Itisimportanttorecognize that theAFSis alsocomposedof amosaic oflandowners, agri-culturalenterprises,timberandcellulosecompanies,wherenative remnantsarestillprotectedbytop-downmanagement,suchasin StrictlyProtectionConservationUnitsandLegalReserves. There-fore,ourconceptualmodelsarenotmutuallyexclusive,andboth top-downandbottom-upstrategiesmayco-occurwithinAFSand contributetomaintainingnativeforestremnantsresilientinthe faceofglobalchanges.

AraucariaForestSystemsareaheritage,leftbypastindigenous societiesthatoncelivedintheregion(Reisetal.,2014;Robinson et al.,2018),and thatnow representsa valuable assetfor local humanpopulations (Melloand Peroni,2015;Adanetal., 2016;

TagliariandPeroni,2018;Quinteiroetal.,2019).Ourfindings indi-catethatthisheritagemightbeatriskinthelong-termforfuture generations.Thecollaborativemanagementstrategybetweenlocal peoples and otherinstitutionsinterestedin theconservation of theseancientandendemicforestsisnecessaryasanalternative strategytomaintainthissocio-ecologicalsystem.However,legal aspectsmayremovelocalpeoplefromdecision-makingand poten-tiallyproduceantagonisticactionsduetorestrictiveconservation measures,suchasseedlingsuppression(Adanetal.,2016;Tagliari andPeroni2018;Quinteiroetal.,2019)ortimberillegal exploita-tion(Schneideretal.,2018).Thisproblematicmayengenderwhat isknownasthe‘EnvironmentalPsychologicBarrier’,wherelocal peopletend toavoid effectiveactiontoimprove/conserve their

surroundingenvironment,eveniftheyperceivethattheseactions bringbiodiversitylossesandnegativeimpactstotheirlives,such aslossoflifequalityandfoodsecurity(TamandChan,2017).Still, otherco-managementinitiativesofculturallyimportantspeciesin Brazilshowedpositiveoutcomesbymaintainingtheplant-human interaction,suchasthoseinvolvingHeveabrasiliensisand Berthol-letiaexcelsa(“rubbertree”and“Brazilnuttree”,respectively)inthe BrazilianAmazon,andRumohraadiantiformis(“samambaia-preta”) in southern Brazil (De Souzaet al., 2006; Gomes et al., 2018). Co-managementprogramswiththesespecieslargelycontributed tomaintainingtheeconomiclivelihoodsandTraditional Ecolog-icalKnowledgeoflocalsmallholdersandpeoplefromindigenous andlocalcommunities(e.g.indigenouspeople,“ribeirinhos”,and/or “caic¸aras”;De Souzaetal.,2006;Gomes etal.,2018).Similarly, theconservationoftheAraucariaForestSystemdependson main-tainingTEKandpromotingcollaborativemanagementinitiatives, becausebottom-upconservationstrategiesaremorelikelyto pro-ducethetransformationsthatthesystemneedstopersistinthe uncertainfuture.Byincorporatingallactorsofthissocio-ecological system,resilienceisreinforcedtowardsexpansion,maintenanceof TEK,andparticipatorysystemicsocio-ecologicalconservation.

CONFLICTOFINTEREST

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

AUTHOR’SCONTRIBUTION

MMTconceivedthemainidea,draftedthemanuscript,analyzed interviews’data,anddidthemainliteraturereview.GDBdrafted themanuscriptanddidtheliteraturereview.CLcontributedtothe literaturereviewanddevelopedthemainstructureofthearticle. BFbroughtvaluableinsightsthattransformedthepurposeofthis study.CFreviewedtheearlyversions,suggestedmainchangesin thestructureofthemanuscript.JBcontributedtothedraft evalua-tion,improvedtheinterviewquestions,andanalyzedthedata.GV contributedwiththeearlyversionsofthemanuscriptandinsights aboutpotentialknowledge-gaps.NPcontributedtodraft develop-ment,literaturereview,insightsaboutknowledge-gaps,improved theinterviewquestions,reviewedtheearlyversions,andproject financing.Allauthorscontributedcriticallytothedraftsandgave finalapprovalforpublication.

DATAAVAILABILITYSTATEMENT

ThismanuscriptispartofanongoingPh.D.thesis.The infor-mationgatheredintheethnoecologicalsurveyswillnotbeableto shareuntilthepublicationofanotherspecificchapter.However, asamanuscriptbasedontheliteraturereview(alreadypublished elsewhere)andcomplementedwiththeethnoecological informa-tionusedinthequestionnaire(seedetailsinSupplementaryFile TablesS1,S2,S3),thereadersmayfindthecoreinformationused inthismanuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MMTthanksalllocalpeopleinterviewed between2018and 2019 who contributed with their knowledge about araucaria, theculturallandscape, and thechallenges smallholders face in Brazil. The authors would like to thank the Coordenac¸ão de Aperfeic¸oamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES/Brazil; Finance Code 001) for the Ph.D. scholarship for MMT and GDB. CL thanks CAPES for the post-doctoral fellowship (no

88887.474568/2020).NPthanksCNPqfortheproductivity scholar-ship(Process310443/2015-6).CTFthankstheFundac¸ãodeAmparo

àPesquisadoEstadodeSãoPaulo(FAPESP)forthepost-doctoral fellowship (Process no 2019/15550-2). JAB is supported by the SãoPauloResearchFoundation(FAPESP)postdoctoralfellowship grants2018-05970-1and2019-11901-5.Thisstudyisdedicatedto EstelamarisandPatrick.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.pecon.2021.03.002.

References

Adan,N.,Atchison,J.,Reis,M.S.,Peroni,N.,2016.LocalKnowledge,Useand ManagementofEthnovarietiesofAraucariaangustifolia(Bert.)Ktze.inthe PlateauofSantaCatarina,Brazil.Econ.Bot.70,353–364,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-016-9361-z.

Bennett,E.M.,Solan,M.,Biggs,R.,McPhearson,T.,Norström,A.V.,Olsson,P., Pereira,L.,Peterson,G.D.,Raudsepp-Hearne,C.,Biermann,F.,Carpenter,S.R., Ellis,E.C.,Hichert,T.,Galaz,V.,Lahsen,M.,Milkoreit,M.,MartinLópez,B., Nicholas,K.A.,Preiser,R.,Vince,G.,Vervoort,J.M.,Xu,J.,2016.Brightspots: seedsofagoodAnthropocene.Front.Ecol.Environ.14,441–448, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/fee.1309.

Berkes,F.,2009.Evolutionofco-management:Roleofknowledgegeneration, bridgingorganizationsandsociallearning.J.Environ.Manage.90,1692–1702, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001.

Berkes,F.,Davidson-Hunt,I.J.,2006.Biodiversity,traditionalmanagementsystems, andculturallandscapes:ExamplesfromtheborealforestofCanada.Int.Soc. Sci.J.58,35–47,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2006.00605.x. Berkes,F.,Colding,J.,Folke,C.,2000.RediscoveryofTraditionalEcological

KnowledgeasAdaptiveManagement.Ecol.Appl.10,1251–1262. Bernard,H.R.,2006.ResearchMethodsinAnthropology:Qualitativeand

QuantitativeApproaches.Library., http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/aa.2000.102.1.183.

Biggs,R.,Schlüter,M.,Biggs,D.,Bohensky,E.L.,Burnsilver,S.,Cundill,G.,Dakos,V., Daw,T.M.,Evans,L.S.,Kotschy,K.,Leitch,A.M.,Meek,C.,Quinlan,A., Raudsepp-Hearne,C.,Robards,M.D.,Schoon,M.L.,Schultz,L.,West,P.C.,2012. Towardprinciplesforenhancingtheresilienceofecosystemservices.Annu. Rev.Environ.Resour.37,421–448,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-051211-123836.

Bittencourt,J.V.M.,Sebbenn,A.M.,2009.Geneticeffectsofforestfragmentationin high-densityAraucariaangustifoliapopulationsinSouthernBrazil.TreeGenet. Genomes5,573–582,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11295-009-0210-4. Bogoni,J.A.,Muniz-Tagliari,M.,Peroni,N.,Peres,C.A.,2020.Testingthekeystone

plantresourceroleofaflagshipsubtropicaltreespecies(Araucariaangustifolia) intheBrazilianAtlanticForest.Ecol.Indic.118,106778,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106778.

BRASIL,2006.Leino11.428,de22dedezembrode2006.Dispõesobreautilizac¸ão eprotec¸ãodavegetac¸ãonativadoBiomaMataAtlântica,edáoutras providências.RepúblicaFederativadoBrasil,Brasília.

BRASIL,2000.Leino9.985,de18dejulhode2000.InstituioSistemaNacionalde UnidadesdeConservac¸ãodanatureza,edáoutrasprovidências.República FederativadoBrasil,Brasília.

Briske,D.D.,Fuhlendorf,S.D.,Smeins,F.E.,2006.Aunifiedframeworkfor assessmentandapplicationofecologicalthresholds.Rangel.Ecol.Manag.59, 225–236,http://dx.doi.org/10.2111/05-115R.1.

Cámara-Leret,R.,Fortuna,M.A.,Bascompte,J.,2019.Indigenousknowledge networksinthefaceofglobalchange.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.116(20), 9913–9918.

Castro,M.B.,Barbosa,A.C.M.C.,Pompeu,P.V.,Eisenlohr,P.V.,deAssisPereira,G., Apgaua,D.M.G.,Pires-Oliveira,J.C.,Barbosa,J.P.R.A.D.,Fontes,M.A.L.,dos Santos,R.M.,Tng,D.Y.P.,2019.WilltheemblematicsouthernconiferAraucaria angustifoliasurvivetoclimatechangeinBrazil?Biodivers.Conserv.29, 591–607,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01900-x.

Cristancho,S.,Vining,J.,2004.CulturallyDefinedKeystoneSpecies.Hum.Ecol.Rev. 11,153–164.

CONAMA–ConselhoNacionaldoMeioAmbiente,2001.Resoluc¸ãono278,de24de maiode2001.Dispõesobreocorteeaexplorac¸ãodeespéciesameac¸adasde extinc¸ãodafloradaMataAtlântica.Brasília:DOUde18/07/2001.

Cruz,A.P.,Giehl,E.L.H.,Levis,C.,Machado,J.S.,Bueno,L.,Peroni,N.,2020. Pre-colonialAmerindianlegaciesinforestcompositionofsouthernBrazil.PLoS One15,1–18,http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235819.

DeAngelis,D.L.,Post,W.M.,Travis,C.C.,1986.PositiveFeedbackinNatural Systems.Springer-Verlag,BerlinHeidelberg.

DeMoura,R.L.,Minte-Vera,C.V.,Curado,I.B.,Francini-Filho,R.B.,Rodrigues, H.D.C.L.,Dutra,G.F.,Alves,D.C.,Souto,F.J.B.,2009.ChallengesandProspectsof FisheriesCo-ManagementunderaMarineExtractiveReserveFrameworkin NortheasternBrazil.Coast.Manag.37,617–632,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08920750903194165.

DeSouza,G.C.,Kubo,R.,Guimarães,L.,Elisabetsky,E.,2006.Anethnobiological assessmentofRumohraadiantiformis(samambaia-preta)extractivismin

SouthernBrazil.Biodivers.Conserv.15,2737–2746, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-005-0309-3.

deVos,A.,Cumming,G.S.,Cumming,D.H.M.,Ament,J.M.,Baum,J.,Clements,H.S., Grewar,J.D.,Maciejewski,K.,Moore,C.,2016.Pathogens,disease,andthe social-ecologicalresilienceofprotectedareas.Ecol.Soc.21,

http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-07984-210120.

Elmqvist,T.,Folke,C.,Nyström,M.,Peterson,G.,Bengtsson,J.,Walker,B.,Norberg, J.,2003.Responsediversity,ecosystemchange,andresilience.Front.Ecol. Environ.1(9),488–494.

Enright,N.J.,Hill,R.S.,1995.Ecologyofthesouthernconifers.UniversityPress, Melbourne.

Estes,J.A.,Terborgh,J.,Brashares,J.S.,Power,M.E.,Berger,J.,Bond,W.J.,Carpenter, S.R.,Essington,T.E.,Holt,R.D.,Jackson,J.B.C.,Marquis,R.J.,Oksanen,L., Oksanen,T.,Paine,R.T.,Pikitch,E.K.,Ripple,W.J.,Sandin,S.,Scheffer,M., Schoener,T.W.,Shurin,J.B.,Sinclair,A.R.E.,Soulé,M.E.,Virtanen,R.,Wardle, D.A.,2011.TrophicdowngradingofplanetEarth.Science333,301–306, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1205106.

Ferro,V.G.,Lemes,P.,Melo,A.S.,Loyola,R.,2014.Thereducedeffectivenessof protectedareasunderclimatechangethreatensAtlanticForesttigermoths. PLoSOne9,http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107792.

Folke,C.,Carpenter,S.R.,Walker,B.,Scheffer,M.,Chapin,T.,Rockstrom,J.,2010. Resiliencethinking:integratingresilience,adaptabilityandtransformability. EcologyandSociety15(4),Nat.Nanotechnol.15,20.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2011.191.

Folke,C.,Hahn,T.,Olsson,P.,Norberg,J.,2005.Adaptivegovernanceof social-ecologicalsystems.Annu.Rev.Environ.Resour.30,441–473, http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511.

Freitas,C.T.de,MacedoLopes,P.F.,Campos-Silva,J.V.,Noble,M.M.,Dyball,R., Peres,C.A.,2020.Co-managementofculturallyimportantspecies:Atoolto promotebiodiversityconservationandhumanwell-being.PeopleNat.2, 61–81,http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10064.

Garibaldi,A.,Turner,N.,2004.Culturalkeystonespecies:Implicationsfor ecologicalconservationandrestoration.Ecol.Soc.9,1,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-061008-103038.

Geldmann,J.,Manica,A.,Burgess,N.D.,Coad,L.,Balmford,A.,2019.Aglobal-level assessmentoftheeffectivenessofprotectedareasatresistinganthropogenic pressures.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.116,23209–23215,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908221116.

Gomes,C.V.A.,Alencar,A.,Vadjunec,J.M.,Pacheco,L.M.,2018.ExtractiveReserves intheBrazilianAmazonthirtyyearsafterChicoMendes:Socialmovement achievements,territorialexpansionandcontinuingstruggles.Desenvolv.e MeioAmbient.48,74–98,http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/dma.v48i0.58830. IBGE,2012.InstitutoBrasileirodeGeografiaeEstatística,Manuaistécnicosem

geociências.Divulgaosprocedimentosmetodológicosutilizadosnosestudose pesquisasdegeociências.RiodeJaneiro.

Laurance,W.F.,2013.Doesresearchhelptosafeguardprotectedareas?Trends Ecol.Evol.28,261–266,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.017. Laurance,W.F.,CarolinaUseche,D.,Rendeiro,J.,Kalka,M.,Bradshaw,C.J.A.,Sloan,

S.P.,Laurance,S.G.,Campbell,M.,Abernethy,K.,Alvarez,P.,Arroyo-Rodriguez, V.,Ashton,P.,Benítez-Malvido,J.,Blom,A.,Bobo,K.S.,Cannon,C.H.,Cao,M., Carroll,R.,Chapman,C.,Coates,R.,Cords,M.,Danielsen,F.,DeDijn,B., Dinerstein,E.,Donnelly,M.A.,Edwards,D.,Edwards,F.,Farwig,N.,Fashing,P., Forget,P.-M.,Foster,M.,Gale,G.,Harris,D.,Harrison,R.,Hart,J.,Karpanty,S., JohnKress,W.,Krishnaswamy,J.,Logsdon,W.,Lovett,J.,Magnusson,W., Maisels,F.,Marshall,A.R.,McClearn,D.,Mudappa,D.,Nielsen,M.R.,Pearson,R., Pitman,N.,vanderPloeg,J.,Plumptre,A.,Poulsen,J.,Quesada,M.,Rainey,H., Robinson,D.,Roetgers,C.,Rovero,F.,Scatena,F.,Schulze,C.,Sheil,D., Struhsaker,T.,Terborgh,J.,Thomas,D.,Timm,R.,NicolasUrbina-Cardona,J., Vasudevan,K.,JosephWright,S.,CarlosArias-G,J.,Arroyo,L.,Ashton,M.,Auzel, P.,Babaasa,D.,Babweteera,F.,Baker,P.,Banki,O.,Bass,M.,Bila-Isia,I.,Blake,S., Brockelman,W.,Brokaw,N.,Brühl,C.A.,Bunyavejchewin,S.,Chao,J.-T.,Chave, J.,Chellam,R.,Clark,C.J.,Clavijo,J.,Congdon,R.,Corlett,R.,Dattaraja,H.S., Dave,C.,Davies,G.,deMelloBeisiegel,B.,deNazaréPaesdaSilva,R,DiFiore, A.,Diesmos,A.,Dirzo,R.,Doran-Sheehy,D.,Eaton,M.,Emmons,L.,Estrada,A., Ewango,C.,Fedigan,L.,Feer,F.,Fruth,B.,GiacaloneWillis,J.,Goodale,U., Goodman,S.,Guix,J.C.,Guthiga,P.,Haber,W.,Hamer,K.,Herbinger,I.,Hill,J., Huang,Z.,FangSun,I.,Ickes,K.,Itoh,A.,Ivanauskas,N.,Jackes,B.,Janovec,J., Janzen,D.,Jiangming,M.,Jin,C.,Jones,T.,Justiniano,H.,Kalko,E.,Kasangaki,A., Killeen,T.,King,H.,Klop,E.,Knott,C.,Koné,I.,Kudavidanage,E.,LahozdaSilva Ribeiro,J.,Lattke,J.,Laval,R.,Lawton,R.,Leal,M.,Leighton,M.,Lentino,M., Leonel,C.,Lindsell,J.,Ling-Ling,L.,EduardLinsenmair,K.,Losos,E.,Lugo,A., Lwanga,J.,Mack,A.L.,Martins,M.,ScottMcGraw,W.,McNab,R.,Montag,L., MyersThompson,J.,Nabe-Nielsen,J.,Nakagawa,M.,Nepal,S.,Norconk,M., Novotny,V.,O’Donnell,S.,Opiang,M.,Ouboter,P.,Parker,K.,Parthasarathy,N., Pisciotta,K.,Prawiradilaga,D.,Pringle,C.,Rajathurai,S.,Reichard,U.,Reinartz, G.,Renton,K.,Reynolds,G.,Reynolds,V.,Riley,E.,Rödel,M.-O.,Rothman,J., Round,P.,Sakai,S.,Sanaiotti,T.,Savini,T.,Schaab,G.,Seidensticker,J.,Siaka,A., Silman,M.R.,Smith,T.B.,deAlmeida,S.S.,Sodhi,N.,Stanford,C.,Stewart,K., Stokes,E.,Stoner,K.E.,Sukumar,R.,Surbeck,M.,Tobler,M.,Tscharntke,T., Turkalo,A.,Umapathy,G.,vanWeerd,M.,VegaRivera,J.,Venkataraman,M., Venn,L.,Verea,C.,VolkmerdeCastilho,C.,Waltert,M.,Wang,B.,Watts,D., Weber,W.,West,P.,Whitacre,D.,Whitney,K.,Wilkie,D.,Williams,S.,Wright, D.D.,Wright,P.,Xiankai,L.,Yonzon,P.,Zamzani,F.,2012.Avertingbiodiversity collapseintropicalforestprotectedareas.Nature489,290–294,