CREATING COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM AND AN

AsSET-BASED APPROACH

TOCOMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

by

Randal D. Pinkett

B.S. Electrical Engineering, Rutgers University,

1994

M.S. Computer Science, University of Oxford, 1996

M.S. Electrical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

1998

M.B.A, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

1998

Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences

School of Architecture and Planning MASSACHUSETTS INUTUTE in partial fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of OF TECHNOLOGY

Doctor of Philosophy at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

MAR 0 4 2002

February 2002

IBRARIES

@2002

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All Rights Reserved.

Author

Randal D. Pinkett

Program

edia Arts and Sciences

January

1

I, 2002

Certified by

Mitchel Resnick

Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences

Program in Media Arts and Sciences

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by

(1)

Andrew B.

Lippman

Chairperson

Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies

Program in Media Arts and Sciences

CREATING COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM AND AN

ASSET-BASED APPROACH TO COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

by

Randal D. Pinkett

Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences School of Architecture and Planning

on January I I, 2002 in partial fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

ABSTRACT

The intersection between community technology programs seeking to close the "digital divide," and community building efforts aimed at alleviating poverty, holds tremendous possibilities, as both domains seek to empower individuals and families, and improve their overall community. Ironically, approaches that combine these areas have received very little attention in theory and practice. As community technology and community building initiatives move toward greater synergy, there is a great deal to be learned regarding how they can be mutually supportive, rather than mutually exclusive. This thesis sheds light on the possibilities inhered at this nexus.

The project that constitutes the basis for this thesis is the Camfield Estates-MIT Creating Community Connections Project, an ongoing effort at Camfield Estates, a predominantly African-American, low- to moderate-income housing development. As part of this project, we worked with residents to establish a technological infrastructure by offering every family a new computer, software, and high-speed Internet connection, along with comprehensive courses and a web-based, community building system, the Creating Community Connections (C3) System, that I have co-designed. The project combined these elements in an effort to achieve a social and cultural resonance that integrated both community technology and community building by leveraging indigenous assets instead of perceived needs.

In relation to this work, I have developed the theoretical framework of sociocultural constructionism and an asset-based approach to community technology and community building. Through this lens, I examine the early results of the project in the areas of community social capital and community cultural capital, based on quantitative and qualitative data resulting from direct observation, surveys, interviews, server logs, and case studies. These findings included expanded local ties, a heightened awareness of community resources, improved communication and information flow at the development, and a positive shift in participants' attitudes and perceptions of themselves as learners.

Finally, based on these and other findings, I discuss the challenges and opportunities of a sociocultural constructionist and asset-based approach, presents lessons learned, and offers recommendations for future community technology and community building initiatives.

Thesis Advisor: Mitchel Resnick

Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Program in Media Arts and Sciences

-This research was supported by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Hewlett-Packard Company, RCN Telecom Services, Microsoft Corporation, Lucent Technologies Cooperative Research Fellowship Program (CRFP), MIT Rosenblith Fellowship, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Doctoral Dissertation Grant, U.S. Department of Commerce ArsPortalis Project, Institute for African-American eCulture (iAAEC) through the National Science Foundation (NSF) Information Technology Research (ITR) Award, and the Digital Nations consortium at the MIT Media Laboratory.

-5-DOCTORAL DISSERTATION COMMITTEE

Thesis Advisor

.

-Dr. Mitchel Resnick

Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences

MIT Media Laboratory

Thesis Reader ,

Dr. Brian K. Smith

Assistant Professor of Media Arts and Sciences

MIT Media Laboratory

Thesis Reader

Dr. Ceasar L. McDowell

Associate Professor of the Practice of Community Development

MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Thesis Reader

Thesis Reader

I

/ ~,.4f(

Dr. Holly M. Carter, President

Community Technology Development, Inc.

ff .6

Dr. Alan C. Shaw, Executive Director

Linking Up Villages

With strength from God...

I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.

- Philippians 4:13

And

in remembrance of my ancestors...

The ancestors teach-not with textbooks but with truth-and I respect them truth-and love them

and praise them and remember them as moral,

spiritual, intellectual, creative giants... and I pray that I can grow

to be that tall someday. - TaraJaye Centeio

This is dedicated to all of my family and friends

who have supported me

during the dissertation process, including...

My Mother - Elizabeth E. Pinkett,

My late Father - Leslie S. Pinkett, in spirit,

My Brothers - Daniel K. Pinkett and Jeffrey A. Robinson, and

My Girlfriend - Zahara N. Wadud.

-9-ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, I must pay honor to God with whom all things are possible. Were it not for my faith and belief in God, I would have never imagined, much less achieved this milestone in my life. I am eternally grateful to countless individuals and organizations for their support, and I would especially like to thank the following people...

My Mother, Elizabeth Pinkett, whose love is a constant and enduring force in my life. Thank you for your strength and perseverance in raising me to become the man I am today. My Brother, Daniel Pinkett, who is always there for me whenever and wherever possible. I may never be able to repay you for all you have done for me. My late Father, Leslie Pinkett, who is always with me in spirit. I know you are looking down with pride while I am looking up in appreciation of how you have influenced my life. My Brother, Jeffrey Robinson, who has been my closest friend for more than a decade now. Words cannot express my gratitude for the important role you have played in my life. God has truly blessed me with your brotherhood. My Girlfriend, Zahara Wadud, who has stood by me throughout the final phase of my dissertation. Your love, compassion, and caring are appreciated more than you may ever know. I look forward to our future together.

On my mother's side of my family - my Grandmother and Grandfather, Merlene and William Elliott, Aunt Valerie and Uncle Herb Prattis, and Cousin Kristina Prattis, Uncle Billy Sanders, and Cousins Adam Sanders and Johnny Sanders, Aunt Edna and Uncle John Bell, Uncle Wilson and Aunt Gloria Elliott, and close friends of the family, Joyce and Liston Abbott, and Wayne and Pascale Abbott. On my father's side of my family - my Grandmother Avious Pinkett, Uncle Medford and Aunt Aretta Pinkett, Uncle Larry Pinkett, Aunt Barbara Pinkett and Cousins Barry Farrare, Cheretta Stansbury, and Angela Spencer, and aunt Helen Pinkett. Thank you all for your love and support throughout the years.

Mitchel Resnick, my thesis advisor, in whom I could not have found a more capable and supportive advisor. Thank you Mitchel for your friendship, for allowing me the latitude to pursue my research agenda, and for your genuine and sincere interest in my work. My experience at the MIT Media Laboratory has been an incredibly positive experience, and I owe much of that to you.

Professor Ceasar McDowell, Professor Brian Smith, Dr. Holly Carter, and Dr. Alan Shaw, the members of my dissertation committee, I am sincerely thankful to all of you for your encouragement, your wisdom, and your able supervision of my research. The final dissertation is a much stronger document as a direct result of your efforts. I would also like to thank Dr. Paula Hooper, who has served as an informal advisor to my work and has given me intellectual and personal inspiration. You are all my role models and I will endeavor to follow in your footsteps.

Richard O'Bryant, my colleague at MIT and close friend who I have worked with side-by-side on the Camfield Estates-MIT project, I am blessed that our collaboration on this project has allowed us to work together, and far more importantly, to become such close friends. You have been like a brother to me.

Rick Borovoy, my officemate at the MIT Media Laboratory and close friend, thank you for your friendship, advice, and support for the past three years. I will miss our daily conversations in 120B. Aldwyn Porter, Cranston Chester, Derrick Richardson and Erike Mayo - the brothers of "102" - thank you for your brotherhood and friendship since our days at Rutgers and beyond. You are all my brothers and I know that I can always count on each and every one of you.

Page I I

Lawrence Hibbert, Dallas Grundy, Munro Richardson, and Andrea Johnson - my close friends and business partners at MBS Educational Services & Training, LLC, and Building Community Technology (BCT) Partners, Inc. - I would not have been able to make it this far without your personal and professional support. I look forward to our future success together.

Trina Williams, Andre Namphy, Nima Warfield, Ryan Iwasaka, Nigel Clarke, Ian Sue-Wing, and Julia Stephenson - my Oxford University, "Black Rhodes" and "Black House" family members - each of you has inspired me as we have all made positive strides since leaving Oxford.

Dean Don Brown, Dr. Ilene Rosen, Sonya Whited, Stacey Harley, Vernette Daniel, Shawn Wallace, Shantell Newman, Raqiba Bourne, Lisa Campagne, Vanna Parker, Anthony Emmanuel, Baron Hilliard, Lydia Ritson, Sekou Bermiss, Desira Holman, Kevin Cadette, Carine Toussaint, Mekita Davis, S. Gordon Moore, Stephanie Adams, Elise Anderson, Regina Harding, Patrick Austin, James Robinson, Troy Miles, Sean Okem Stallings, and Kevin Ewell - my Rutgers University, National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE) and New Jersey family members - thank you all for your positive encouragement.

The Black Graduate Student Association (BGSA) family at MIT, and in particular, Chris Jones, who has been like a brother to me. I will miss our lunchtime meetings.

Peter Kroon, my mentor and friend at Lucent Technologies, thank you for your ongoing advice and guidance throughout my graduate studies.

Nakia Keizer, thank you for your leadership of the Camfield Estates-MIT project. It has been a pleasure getting to know you and working with you. I respect you as a colleague and admire you as a friend. Karie Rosa, Alex Rosa, and Arthur Jones, thank you for your involvement with the Camfield Estates-MIT project team. Your participation is greatly appreciated. Donna Fisher, thank you for your close friendship and valuable contributions to Camfield. I have enjoyed our time together both personally and professionally. Paulette Ford, thank you for your longstanding commitment to Camfield. I am grateful for having the opportunity to work with you and the CTA Board of Directors. Thaddeus Miles, thank you for your generous advice and unselfish contributions to Camfield. I greatly admire and respect your commitment to the community. Wayne Williams, thank you for your efforts at the Camfield Estates Neighborhood Technology Center (NTC). Throughout the Camfield Estates-MIT project we have both shared a concern for the best interests of the residents, and for that I am grateful. Nakia, Donna, Paulette, Diane Atkins, Constance Terrell, and Gail Smith, thank you for welcoming me into your homes and your lives.

Professor David Gifford from the MIT Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS), Dr. Gail McClure from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, David Chandler, from the Boston Globe, and Dr. Phillip Greenspun, formerly of ArsDigita Corporation, I sincerely thank all of you for your assistance. Without each of you the Camfield Estates-MIT project would not have been possible. Thank you David for having the vision to embark on such an ambitious project. Thank you Gail for your leadership and commitment to the project and others like it. Thank you David for taking the time to help us bring the project to fruition. Thank you Phillip for your technical support of the Creating Community Connections (C3) System via the ArsDigita Community System (ACS), as well as for your advice, generosity, and time.

I would also like to thank the following people for supporting the Camfield Estates-MIT project and supporting me during my time at MIT...

Various individuals representing academic, corporate, and non-profit organizations, including Caroline Carpenter - W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Robert Bouzon and Camilla Nelson - Hewlett Packard Company, John McGeough and Ken Rahaman - RCN Telecom Services, David Martin - ArsDigita Corporation, Bryant York and Roscoe Giles - Institute for African-American eCulture (iAAEC), Ken

Smith - YouthBuild, Gail Breslow and Marlon Orozco - The Computer Clubhouse, and Peter Miller and Richard Civille - ArsPortalis Project.

Members of the Epistemology and Learning Group, past and present, including Robbin Chapman, Vanessa Colella, Marina Umaschi Bers, Claudia Urrea, Kwindla Kramer, Fred Martin, David Cavallo,

Bakhtiar Mikhak, Leo Burd, Eleonora Badilla-Saxe, Chris Hancock, Diane Willow, Savalai Vaikakul, Rahul Bhargava, Michelle Hublinka, Daniel Kornhauser, Brian Silverman, Casey Smith, Andrew Begel, Robbie Berg, Michelle Shook, Camilla Holten, Teresa Castro and Missy Corley, and especially Carolyn Stoeber for keeping our group and various aspects of the Camfield Estates-MIT project organized and running

smoothly at all times.

Students, faculty and staff at the MIT Media Laboratory, including LaShaun Middlebrooks-Collier, Linda Peterson, Walter Bender and Kevin Brooks, as well as numerous undergraduate and graduate researchers who worked diligently to assist me with my research including Solomon Steplight, Wei-An Yu, Megan Henry, Shireen Brathwaite, Shelly O'Gilvie, Johanne Blain, Aisha Stroman, Simon Lawrence, F. Anthony St. Louis, and Francisco Santiago.

Students, faculty and staff in the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) and the MIT Center for Reflective Community Practice (CRCP), including Professor Joseph Ferreira, and Professor

Keith Hampton, and especially Gail Cheney for her assistance throughout my time on campus.

Students, faculty and staff at MIT, including Dean Ike Colbert, Dean Blanche Staton, Dean Roy Charles, Brima Wurie, and Ed Ballo in the Graduate Education Office (GEO), Dean Osgood in the Office of Minority Education (OME), Daniel Sheehan in the MIT Information Services (IS) Department, and Professor Starling Hunter in the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Fellow researchers and friends, including Versonya DuPont, Brendesha Tynes, Kate Williams, Blanca Gordo, and Professor Joseph Bowman. I would especially like to thank Dr. Nicol Turner-Lee, with whom I am honored to have collaborated on related research projects.

Staff at the Camfield Estates Neighborhood Technology Center (NTC), including Wayne Williams, Jackie Williams, Garfield Williams, Luis Herrera, and Manuel Roman.

Staff at Cornu Management Company, including Tom Cornu, Charlie Maneikis, Miguel "Mikey" Santiago, Virginia Davis, and Tresza Trusty.

Members of the Camfield Tenants Association (CTA) Board of Directors, including Paulette Ford, President, Constance Terrell, Luon Williams, Edward Harding, Susan Terrell, Marzella Hunt, Cora Scott, Alberta Willis, Minnie Clark and Daniel Violi.

If there is anyone I have forgotten, please blame my head and not my heart.

Creating Community Connections Page 13

CREATING COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM AND AN

AsSET-BASED APPROACH TO

COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ...

3

A CKNOW LEDGEM ENTS ... I I

C

HAPTER : INTRODUCTION ... 24THE DIGITAL DIVIDE AND COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY... 24

POVERTY ALLEVIATION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING... 26

RESEARCH PROBLEM ... 28

RESEARCH PROJECT ... 29

THEORETICAL FRAMEW ORK ... 30

Sociocultural Constructionism...30

Asset-Based Community Development ... 32

A Vision for Community Technology and Community Building...33

RESEARCH Q UESTION AND HYPOTHESIS ... 35

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY ... 38

O RGANIZATION OF THESIS...38

C

HAPTER2:

BACKG ROUND ...4

I

COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY ...41

Community Networks... ... ... 42

Community Technology Centers...43

C om m unity C ontent...45

COMMUNITY REVITALIZATION ... 48

C om m unity O rganizing...48

C om m unity D evelopm ent...50

C om m unity Buildin ... 52

CHAPTER

3:

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

...

56

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RESONANCE ...

56

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM ... 60

C onstructionism ... 60

Social Constructionism ... ... 61

C ultural C onstructionism ... 6 2 Sociocultural Constructionism ... 64

ASSET-BASED AND NEEDS-BASED APPROACHES ... 69

ASSET-BASED COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ... 71

THE DIMENSIONS OF COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING ...

75

Bottom -U p vs. Top-D ow n...75

Inside-O utside... 76

Product and Process...78

RELATED THEORY AND PRACTICE ... 79

THE PRAXIS OF SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM AND AN ASSET-BASED APPROACH TO COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING...85

Com m unity Social C apital...85

Com m unity Cultural Capital ... 86

Community Technology and Community Building Outcomes ... 87

CHAPTER 4: RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY ... 89

RESEARCH PROBLEM ... 89

RESEARCH SITE - CAM FIELD ESTATES ...

90

H istory...91

D em ographics ... 92

RESEARCH PROJECT - CAMFIELD ESTATES-M IT PROJECT ...

95

RESEARCH Q UESTION AND HYPOTHESIS ...

98

RESEARCH METHODS ...

98

Q uantitative M ethods... 99

Q ualitative M ethods ... /0

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS ... 103

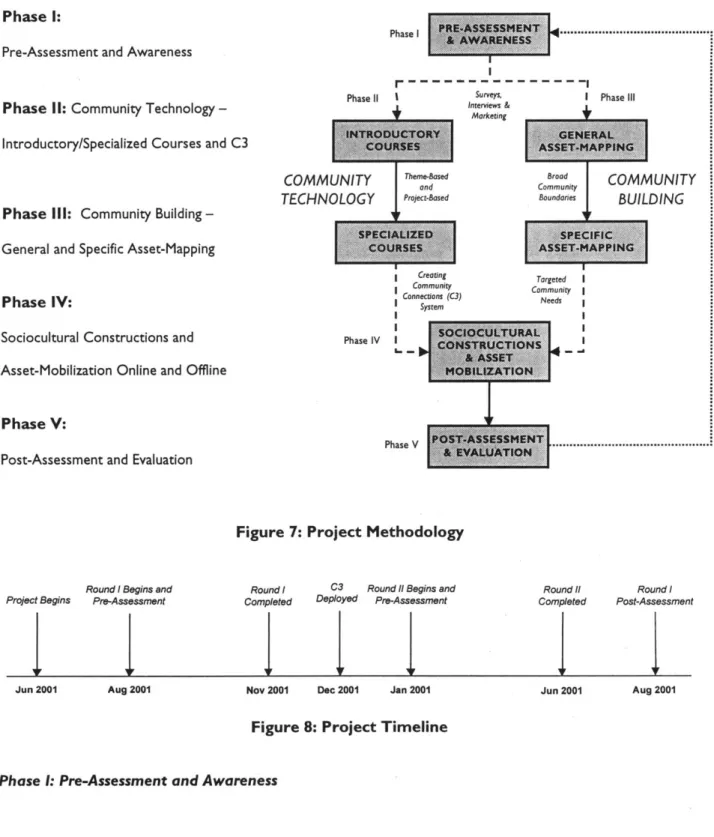

PROJECT METHODOLOGY AND TIMELINE...104

Phase I: Pre-Assessment and Awareness ... .... 107

Phase It: Community Technology - IntroductorylSpecialized Courses and the C3 System ... 108

Phase I: Community Building - General and Specific Asset-Mapping ... 113

Phase IV: Sociocultural Constructions and Asset-Mobilization Online and Offline ... II 7 Phase V: Post-Assessment and Evaluation... 117

CHAPTERS:

TECHNOLOGY AND THEC3SYSTEMM

...I

19

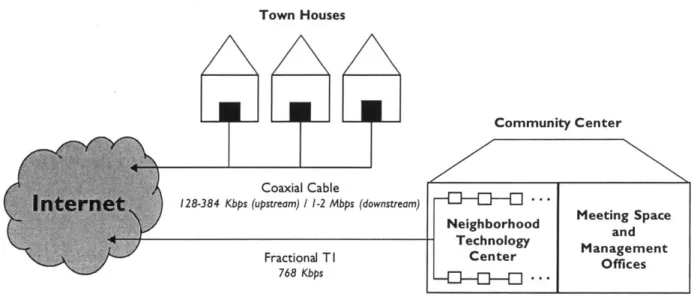

TECHNOLOGICAL INFRASTRUCTURE ...119

Cam field Estates Community Network... 119

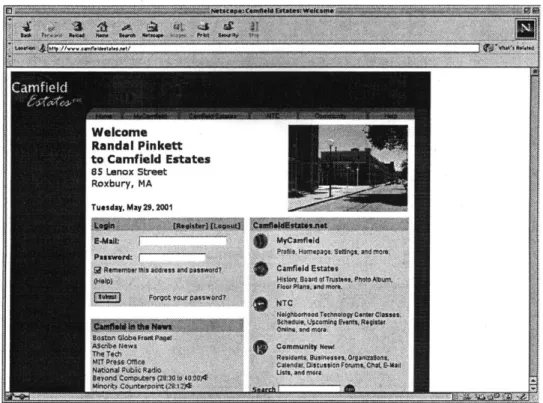

Cam field Estates Neighborhood Technology Center (NTC) ... 123

Cam field Estates Community Content... 125

THE CREATING COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS (C3) SYSTEM ... 128

B ackground ... 12 8 System M odules... 12 9 T echnical Specifications ... 1 4 0 T a INITIAL A SSESSMENT... 143

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ...

143

D em og rap hics ... 14 4 Community Interests and Satisfaction... 146

Awareness of Community Resources...148

Impressions of the Community ... 149

C om m unity Involvem ent... 15 0 Community Attachment... 153

Computer Experience and Training Interests... 154

Hobbies, Interests and Information Needs... .. . . . .56

SUM

MA RYand Information.. . ... 159RECOMMENDATIONS ... 161

CHAPTER

7:

STRATEGIES UNDERTAKEN ...163

APPLICATION OF FINDINGS ... 163

Cam field Estates Website and the C3 System... 165

Youth ... 1 67 Seniors t... 1 70 C o m u iy ... ... .... ... 4... ... I 72 Safety Security ... ... 76

Em ploym ent ... 1 79

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONS AND ASSET-M OBILIZATION ... 182

C HAPTER 8: EARLY RESULTS ... I 86 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ...

1

86 D em ographics... 18 7 COMMUNITY SOCIAL CAPITAL... 188Social N etw orks ... 1 8 9 Obligations and Expectations of Trustworthiness ... 191

N orm s and Effective Sanctions... 191

A ccess to Inform ati on Channels ... 92

COMMUNITY CULTURAL CAPITAL...1 94 K now ledge and Resources ... 1 95 Shared Interests ... 2 04 Technological Fluency... 208

A ttitude and Perception ... 215

SUMMARY...218

C HAPTER 9: CASE STUDIES... 22

CASE STUDY

#1

- PAULETTE FORD: THE FUTURE AT CAMFIELD ESTATES...222Community Building at Cam field Gardens ... 223

N ew Property, N ew Possibilities...225

Building Community at Cam feld Estates ... 227

Looking Fo w ard ... 2 2 9 CASE STUDY #2- DIANE ATKINS: GREATEST PROPONENT...231

Reluctance, Recruitment and Resonance...232

Computer as Information Technology ... 234

Computer as Communications Technology...235

Consumer and Producer... ...---... 237

A Social and Cultural Shift ... 238

Community Technology and Communi ty Building ... 241

CASE STUDY #3 - CONSTANCE TERRELL: TOWARD TECHNOLOGICAL FLUENCY...242

M ore Than a Salon ... 243

Preparing for the 2 I' Centu y ... 244

Sewing the Seeds of Entreprenershi p Again ... 246

Tow ard G reater Technological Fluency...249

CASE STUDY #4 - DONNA FISHER: PERSPECTIVES ON CAMFIELD ESTATES...250

Community Relations and Community Technology... .25I Community Relations and Community Building...255

CASE STUDY #5 - NAKIA KEIZER: COMING OF AGE IN THE DIGITAL AGE ... 257

The Cam field Estates-MIT Creating Community Connections Project ... 259

A Social and C ultural Shift ... 2 63 H aving C om e of A ge...2 6 7

CHAPTER

I

0: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES ...269

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF THE CAMFIELD ESTATES-MIT PROJECT ... 270

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF A SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONIST AND ASSET-BASED APPROACH ... 277

Balancing Tim e and Resources...2 78 Coordinating Multiple, Interrelated Activities...282

Developing a "Curriculum" that Supports Sociocultural Constructionist and Asset-Based Outcomes...284

Conducting Assessment and Evaluation...288

Sustaining the Initiative .. . . . .292

C

HAPTER .1: CONCLUSION...297INCREASING COMMUNITY SOCIAL CAPITAL ... 297

ACTIVATING COMMUNITY CULTURAL CAPITAL ...

300

LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS...304

Seek to Understand the Social and Cultural Environment3...304

Seek to Understand Individuals, Families and the Community...305

Leverage Assets Through Coordinated Effort...306

D em onstrate Relevance Clearly ... 30 7 Spread Technology Costs... 308

Strategically Build Community Offline: Emphasize Outcomes Instead of Access...309

Strategically Build Community Online: Orchestrate System Development and Deployment...310

Integrate O nline w ith O fffline... 311

Encourage Bottom-Up, Inside-Out Revitalization...312

Acknowledge and Support Both Process and Product ... 312

Engage Residents as Active Partici pants in the Process ... 313

Integrate Community Technology and Community Building Holistically...314

Connect the Community Technology Movement and the Community Building Movement ... 315

CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 318

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 32

I

Creating Community Connections Page 19

CREATING COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM AND AN

ASSET-BASED APPROACH TO COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

FIGURES

Figure I: Picture of C am field Estates... 91

Figure 2: C am field Estates Race... 93

Figure 3: C am field Estates Ethnicity ... 93

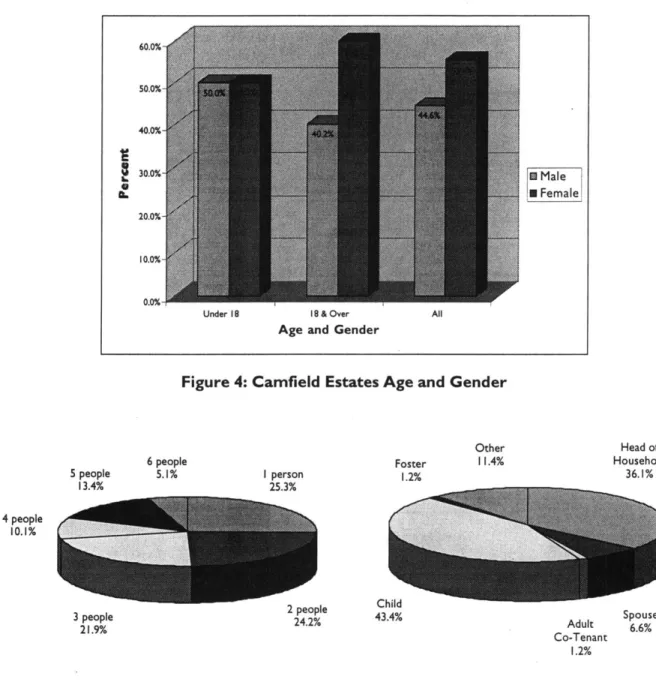

Figure 4: Camfield Estates Age and Gender ... 94

Figure 5: Camfield Estates Family Size ... 94

Figure 6: Camfield Estates Relationship ... 94

Figure 7: Project M ethodology ... 107

Figure 8: Project T im eline... 107

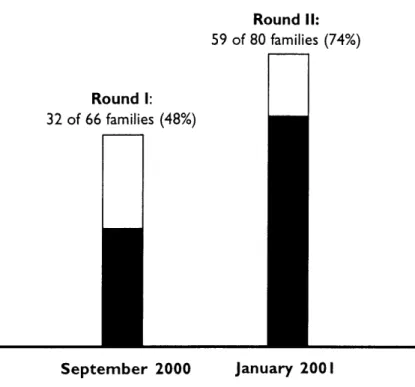

Figure 9: Resident Participation and Non-Participation ... I I Figure 10: Resident Participation and Non-Participation Breakdown ... 112

Figure 11: Camfield Estates Catchment Area... 115

Figure 12: Computer, TV and Cable Modem Topology... 122

Figure 13: Camfield Community Network Topology... 123

Figure 14: Picture of Camfield Estates Neighborhood Technology Center (NTC)... 125

Figure I5: Northwest Tower Website ... 131

Figure 16: The Creating Community Connections (C3) System v 1.0... 131

Figure 17: C am field Estates W ebsite... 132

Figure 18: The Creating Community Connections (C3) System v2.0... 132

Figure 19: C 3 Resident Profiles M odule ... 136

Figure 20: C 3 G IS M aps M odules ... 1 36 Figure 2 1: C 3 Business D atabase M odule ... 137

Figure 22: C3 Organization Database Module... 137

Figure 23: C3 Discussion Forums Module ... 138

Figure 24: C3 E-Mail Lists (Listservs) Module... 138

Figure 25: C3 Calendar of Events Module ... 139

Figure 26: C 3 C hat Room s M odule ... 139

Figure 27: C3 Site-Wide Search Module ... 140

Figure 28: C 3 C ore A rchitecture... 142

Figure 29: C 3 D ual-Server A rchitecture... 142

Figure 30: Race of Participants... 144

Figure 3 1: G ender of Participants... 144

Figure 32: Age of Participants... 145

Figure 33: M arital Status of Participants... 145

Figure 34: Education of Participants ... 145

Figure 35: Fam ily Size of Participants ... 145

Figure 36: A nnual Incom e of Participants... 145

Figure 37: C om m unity Involvem ent Continuum ... 153

Figure 38: C om m unity Attachm ent C ontinuum ... 154

Figure 39: Cam field Estates... 184

Figure 40: Race of Participants... 187

Figure 4 1: G ender of Participants... 187

Figure 42: Age of Participants... 187

Figure 43: M arital Status of Participants... 187

Figure 44: Education of Participants ... 188

Figure 45: Fam ily Size of Participants ... 188

Figure 46: A nnual Incom e of Participants... 188

Figure 47: C am field Estates W eb Server Percent H its By M odule ... 197

Figure 48: Cam field Estates H elp D iscussion Forum ... 198

Figure 49: Cam field Estates C alendar of Events ... 199

Figure 50: Cam field Estates Resident Profiles... 200

Figure 5 1: W eb Server Sessions and ... 201

Figure 52: W eb Server M onthly H its ... 201

Figure 53: Recom m ended Project M ethodology... 315

CREATING COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM AND AN

ASSET-BASED APPROACH TO COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

TABLES

T able I: C am field A ge ... 93

Table 2: Camfield Estates Annual Incom e... 95 Table 3: Preliminary Assessment and Post-Assessment Survey Areas... 100 Table 4: Creating Community Connections (C3) System Intranet Modules... 133 Table 5: Creating Community Connections (C3) System Extranet Modules... 134 Table 6: Creating Community Connections (C3) System Selected Module Notes ... I 35 Table 7: Best Thing about Living in Camfield Estates ... 146 Table 8: Problems Facing the Camfield Estates Community... 147 Table 9: Ideas for Making Camfield Estates a Better Place to Live... 147 T able 10: Ranked Issues ... 148 Table I I: Desired Improvements as a Result of Camfield Estates-MIT Project ... 148 Table 12: Awareness of Com m unity Resources... 149 Table 13: Feelings about Awareness of Community Resources... 149 Table 14: Im pressions of Cam field Estates... 50

Table I5: M embership in Com m unity O rganizations... 151 Table 16: Political Involvem ent... 151 Table 17: D esired Training Topics ... 1 55 Table 18: Anticipated Life Changes as a Result of New Computer and Internet... 155 Table 19: Anticipated Use of New Computer and Internet... 156 Table 20: Sources of Com m unity Information ... 156 Table 2 1: Com m unity Inform ation ... 157 Table 22: C om m unity O rganizations... 157 Table 23: Inform ation D esired to Share ... 158 Table 24: Inform ation D esired to O btain ... 158 Table 25: Items Desired on the Camfield Estates W ebsite ... 158 Table 26: C am field Estates... 184 Table 27: Residents' Social Networks at Camfield Estates... 189 Table 28: Residents' Connectedness Since Receiving Their Computer and Internet Access... 190

Table 29: Residents' Awareness and Utilization of Community Resources...I 92 Table 30: Residents Rating of the Usefulness of the Camfield Estates Website...I 93 Table 3

I:

Camfield Estates Proxy Server - Top 20 Domains (January 200 ) ... 206 Table 32: Residents' Patterns of Use for National and Local Information... 207 Table 33: Residents' Most Popular Uses of Their Computer and Internet Access... 208Creating Community Connections Page 23

CHAPTER

I

INTRODUCTION

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE AND COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY

The "digital divide" is the phrase commonly used to describe the gap between those who benefit from new technologies and those who do not - or the digital "haves" and "have nots." Since 1994, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) in the U.S. Department of Commerce has released five reports examining this problem, all under the heading "Falling Through the Net" (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1995, 1998, 1999 & 2000). Each study has reached the same glaring conclusion: the digitally divided are becoming more divided. In their most recent report, Falling Through the Net: Toward Digital Inclusion, the U.S. Department of Commerce writes:

A digital divide remains or has expanded slightly in some cases, even while Internet access and computer ownership are rising rapidly for almost all groups. For example, the August 2000 data show that noticeable divides still exist between those with different levels of income and education, different racial and ethnic groups, old and young, single and dual-parent families, and those with and without disabilities... Until everyone has access to new technology tools, we must continue to take steps to expand access to these information resources. (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2000, p. xv)

In response to the digital divide, a number of community technology (Beamish, 1999; Morino, 1994) initiatives have emerged in rural and low-income communities across the country (Bowman et al., 1999; Bishop et al., 1999; Fowells & Lazarus, 2001; Sch6n et al., 1999). Community technology is defined as

"using the technology to support and meet the goals of a community" (Beamish, 1999, p. 366). The primary form for these efforts has been community technology centers (CTCs), or publicly accessible facilities that provide computer and Internet access, as well as technical instruction and support. However, in light of the U.S. Department of Commerce's and other organization's findings, it is clear that such strategies are a necessary, but not sufficient measure for bridging the digital divide (Benton Foundation, 1998). This is further contextualized by the propensity of most community technology initiatives to be narrowly focused on providing economical access and training, without a more pertinent emphasis on meaningful use and outcomes, such as how technology can serve the individual and collective interests of a community. In From Access to Outcomes: Raising the Aspirations for Technology Investments in Low-Income Communities, the Morino Institute writes:

To date, most initiatives aimed at closing the digital divide have focused on providing low-income communities with greater access to computers, Internet connections, and other technologies. Yet technology is not an end in itself The real opportunity is to lift our sights beyond the goal of expanding access to technology and focus on applying technology to achieve the outcomes we seek - that is, tangible and meaningful improvements in the standards of living of families that are now struggling to rise from the bottom rungs of our economy. (Morino

Institute, 2001, p. 4) (Emphasis Mine)

In other words, access to technology alone, without appropriate content and support, as well as a vision of its transformative power, can not only lead to limited uses, but shortsighted ones as well. Or, as Resnick and Rusk (1996) plainly, but eloquently sum up, "access is not enough." Now, with a myriad of efforts underway to bring information and communications technology into underserved communities on a widespread basis, the key question to be answered is: what can be done to leverage a community technological infrastructure in a way that improves the lives of individuals and families within these communities? I believe "community building" is directly relevant and central to this discussion.

POVERTY ALLEVIATION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

There have been a variety of efforts to revitalize America's distressed communities and alleviate poverty, many dating back to the late nineteenth century. Presently, these initiatives take a variety of forms including Comprehensive Community Initiatives (CCIs) (Aspen Institute, 1997; Hess, 1999; Smock, 1997) and Empowerment Zones/Enterprises Communities (EZ/ECs) (HUD, 1999). Despite these efforts, our modern reality is that the gap between America's rich and poor - the historical "haves" and "have nots" - still exists to this day, along various social, ethnic, and racial lines. In Common Purpose: Strengthening Families and Neighborhoods to Rebuild America, Schorr writes:

The polarizing effects of growing income inequality are intensified by racial, ethnic and class differences, and solidified by a dramatic upsurge in geographic separation. At one end of town are the fortunate fifth, "quietly seceding from the rest of the nation," in walled-off privacy. Across town, the losers live in ever greater isolation, in neighborhoods steeped in violence and despair, with a majority of adults not working, not married, and not succeeding in any activity society values, and with a life expectancy lower than that of their counterparts in Third World countries. (Schorr, 1997, p. xvii)

As strategies to alleviate poverty have emerged and evolved over time, a general convergence has gradually occurred among community theorists, researchers, and practitioners, concerning the success factors of comprehensive community building (Aspen Institute, 1997; Kingsley, McNeely & Gibson, 1999; Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993; Naparstek, Dooley & Smith, 1997; Schorr, 1997). Community building is an approach to community revitalization that is focused on "strengthening the capacity of residents, associations, and organizations to work, individually and collectively, to foster and sustain positive neighborhood change" (Aspen Institute, 1997, p. 2).

Creating Community Connections Page 26

Led primarily by community-based organizations (CBOs), or private, non-profit organizations that are representative of segments of communities, a number of success stories have emerged of community building efforts in previously impoverished inner city neighborhoods and low-income communities around the country. Unfortunately, for many Americans low-income communities and the inner city conjure images of poverty, crime, violence, vacant and abandoned buildings, joblessness, gangs, drugs, homelessness, and welfare dependency. What stands out from these new approaches to community revitalization is the acknowledgement that underserved communities possess their own indigenous resources or assets that can, and must be leveraged in order to achieve success. In Community Building Coming of Age, Kingsley, McNeely and Gibson of the Urban Institute write:

Probably the feature that most starkly contrasts community building with approaches to poverty alleviation that have been typical in America over the past half-century is that its primary aim is not simply giving more money, services, or other material benefits to the poor. While most of its advocates recognize a continuing need for considerable outside assistance (public and private), community building's central theme is to obliterate feelings of dependency and to replace them with attitudes of self-reliance, self-confidence, and responsibility. (Kingsley, McNeely & Gibson, 1999, p. 4)

As community building initiatives are undertaken in inner city and urban centers across the country, the key question to be answered is: what can be done to further advance these efforts in a new and innovative way? I believe "community technology" lies at the heart of the answer to this question.

RESEARCH PROBLEM - THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN COMMUNITY

TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

The digital divide is a modern day reflection of historical social and economic divides that have plagued our society for years. Over the past decade, the community technology movement has gathered momentum toward closing the gap with programs targeted at access, training, content, technological fluency, and more. Over the past century, the community building movement has wrestled with complementary issues in its' efforts to alleviate poverty by instituting programs aimed at education, health care, employment, economic development, and the like.

The intersection between these domains holds tremendous possibilities, as both efforts seek to empower individuals and families, and improve their overall community. Ironically, approaches that combine these areas have received very little attention in theory and practice. In fact, community technology efforts are often completely decoupled from community building initiatives for a variety of reasons including their disparate funding sources (significant private-sector support in the form of high-tech corporations for community high-technology, and significant public-sector support in the form of government programs for community building), disparate foci (access for community technology, outcomes for community building), and disparate constituencies (primarily CTCs for community technology and CBOs for community building). Fortunately, a few advocates have begun to highlight this disconnect and recommend strategies to address it (Kirschenbaum & Kunamneni, 2001; Turner & Pinkett, 2001). This dissertation is intended to contribute to this dialogue.

From among the three models of community engagement with technology - community technology centers (CTCs), community networks, and community content (Beamish, 1999) - there is a limited number of projects that have engaged community residents as active participants in using technology to define processes for neighborhood revitalization. Conversely, from among the multitude of models for

community engagement with revitalization - such as community organizing, community development, community building, and comprehensive community initiatives (CCIs) (Hess, 1999) - we are only beginning to witness the benefits that are afforded by incorporating new technologies into these approaches in a way that truly leverages their potential.

The best practices of community technology see community members as active producers of community information and content. Similarly, the best practices of community building see community members as active agents of change. As community technology and community building initiatives move toward greater synergy, there is a great deal to be learned regarding how community technology and

community building can be mutually supportive, rather than mutually exclusive. My research problem is to shed light on the possibilities inhered at this nexus.

RESEARCH PROJECT - THE CAMFIELD ESTATES-MIT CREATING COMMUNITY

CONNECTIONS PROJECT

The project that constitutes the basis for this thesis is the Camfield Estates-MIT Creating Community Connections Project, a partnership between the Camfield Tenants Association (CTA) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), started in January 2000. Camfield Estates is a 102-unit, predominantly African-American, low- to moderate-income housing development in the South End/Roxbury section of Boston, Massachusetts. The Camfield Estates-MIT project has as one of its goals to establish Camfield Estates as a model for other housing developments across the country as to how individuals, families, and a community can make use of information and communications technology to support their interests and needs.

To achieve this goal, we have established a community technological infrastructure at Camfield by offering every family a state-of-the-art computer, software, and a high-speed Internet connection, along

with comprehensive courses at the Neighborhood Technology Center (NTC), an approximately fifteen-computer community technology center (CTC) on the premises. We have also created a web-based, community building system, the Creating Community Connections (C3) System, that I have co-designed with Camfield residents, specifically to create connections between residents, local associations and institutions (e.g., libraries, schools, etc.), and neighborhood businesses. The project combined these elements in an effort to achieve a social and cultural resonance that integrated both community technology and community building by leveraging indigenous assets instead of perceived needs.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK:

SOCIOCULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONISM AND AN

ASSET-BASED

APPROACH TO

COMMUNITY TECHNOLOGY AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

In relation to this work, I have developed the theoretical framework of sociocultural constructionism and an asset-based approach to community technology and community building, an integration of the theories of

sociocultural constructionism (Hooper, 1998; Pinkett, 2000; Shaw, 1995) and asset-based community

development (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993).

Sociocultural Constructionism

Sociocultural constructionism argues that individual and community development are reciprocally enhanced by independent and shared constructive activity that is resonant with both the social environment of a community of learners, as well as the culture of the learners themselves (Pinkett, 2000). A sociocultural construction is a physical, virtual, or cognitive artifact that is resonant with the social and cultural milieu. This includes a community newsletter (paper-based and/or electronic) with valuable local content, a personal website that highlights information of interest to other members of the community, a posting to a discussion forum that shares useful knowledge or wisdom, a message to a

neighborhood e-mail list that engages in relevant issues, or even a paradigm shift that reflects a renewed confidence in oneself or greater appreciation of ones community. Sociocultural constructionism regards community members as active producers of community information and content, as opposed to passive consumers or recipients.

In the context of community technology, I present a sociocultural constructionist approach as being consistent with the following three guidelines:

e Empower Individuals, Families, and Communities - Sociocultural constructionism seeks to empower

individuals, families, and communities to identify their interests and how technology can support those interests.

e Engage People as Active Producers, Not Consumers - Sociocultural constructionism encourages

individual expression of one's knowledge, interests, and abilities, as well as communication and information exchange at the community level, as mediated by technological fluency.

" Emphasize Outcomes, Instead of Access - Sociocultural constructionism posits that one pathway to achieving individual and community development is to position technology as a tool for achieving outcomes in areas such as education, health care, and employment, as opposed to a tool for access.

These principles reflect my observations of the lessons learned from the community technology movement thus far.

Asset-Based Community Development

Asset-based community development (ABCD) is a model for community building which assumes that social and economic revitalization begins with what is already present in the community - not only the capacities of residents as individuals, but also the existing associational, institutional, and commercial foundations (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993). This is done by focusing on indigenous community assets (e.g., residents, local organizations and institutions, neighborhood businesses, etc.) instead of perceived needs. Asset-based community development seeks to leverage the resources within a community by "mapping" these assets and then "mobilizing" them to facilitate productive and meaningful connections, toward addressing community-defined issues and solving community-defined problems. Asset-based community development regards community members as active agents of change, rather than passive beneficiaries or clients.

Kretzmann and McKnight (1993) identify three characteristics of asset-based community development:

" Asset-Based - Asset-based community development begins with what is present in the community, as opposed to what is absent or problematic in the community.

* Internally Focused - Asset-based community development calls upon community members to identify

their interests and build upon their capacity to solve problems.

* Relationship Driven - Asset-based community development encourages the ongoing establishment of

productive relationships among community members, as well as the associated trust and norms necessary to maintain and strengthen these relationships.

According to Kretzmann and McKnight (1993), these principles acknowledge and embrace the traditions of successful community revitalization efforts from the past.

A Vision for Community Technology and Community Building

Sociocultural constructionism and an asset-based approach to community technology and community building suggest that the way to build physical, geographic, collocated communities both online and offline is by creating community connections amongst community members and community resources as

mediated by technological fluency, asset-mapping, sociocultural constructions, and asset-mobilization. It is an approach that strives to achieve a social and cultural resonance within a community, by focusing on indigenous assets instead of perceived needs.

There are a number of ways that a sociocultural constructionist and asset-based scenario can play itself out. Having completed a course on web design, a father could build a personal website that shares his observations from raising his daughter, thus providing the opportunity for other parents to learn from his experiences. A resident could send a message to an e-mail list seeking plumbing assistance only to find a neighbor whose skills in this area he was previously unaware of. A youth could create an online photo album that visually depicts a landmark of historical significance, and helps to educate other youth of its importance. A community leader could submit a posting to a discussion forum informing residents of the planned demolition of a longstanding park. After completing an introductory course at a nearby community technology center, a participant could be motivated to consider a more advanced course as a result of a renewed confidence in her abilities. Each of these scenarios is akin to "connecting the dots" and is mediated by the creation of sociocultural constructions and the mobilization of local assets. They represent people connecting to people, people connecting to assets, or people connecting via sociocultural constructions that help facilitate the aforementioned connections. This is the vision of sociocultural constructionism and an asset-based approach to community technology and community building.

In many ways, this theoretical framing of the community technology and community building movements here, and throughout this dissertation, falls short of their current empirical reality. Here, I am presenting a vision for what community technology and community building can be, not what they are.

Access, and to some extent training, has been the primary focus of the community technology movement thus far. This includes a series of policies, funding, and programs that bear no connection to the issues that fundamentally affect individuals, families, and communities, such as education, employment, health care, and economic development. At best, the organizations that support this movement are only beginning to situate their work within the realm of social and economic justice.

Similarly, the community building movement has yet to embrace technology as an integral component of their work in distressed neighborhoods. Technology-related issues such as access, content, training, and technological fluency, have not entered their discussions of how low-income and underserved communities can be best served. At best, the organizations that support this movement are only beginning to consider the role of technology in managing their internal operations, much less their outreach to the community.

Finally, the community technology and community building movements are not integrated movements at the present time. Granted, examples of successful projects have begun to emerge (Bowman et al., 1999;

Fowells & Lazarus, 2001; Kirschenbaum & Kunamneni, 2001), but due to the differences in their objectives, structure of their funding streams, and lack of communication amongst their advocates, they have largely existed in parallel and separate spheres of existence. This has taken place despite the similarities in their target populations, geographic collocation in several neighborhoods, and apparent synergies that could result from their union. Sociocultural constructionism and an asset-based approach to community technology and community building endeavors to provide a vision for how these movements can converge. This dissertation attempts to provide some insight on how to get there.

RESEARCH QUESTION AND HYPOTHESIS

As theory, the sociocultural constructionist and asset-based perspective has served two purposes in the context of this dissertation. First, the Camfield Estates-MIT Creating Community Connections Project has drawn upon the ideas and principles underlying this theoretical framework. The manner and extent to which this perspective has influenced the project have been primarily determined by my integral involvement as a participatory action researcher (Brown, 1983; Cancian, 1993; Friedenberger, 1991; O'Brien, 1998; Peattie, 1994; Whyte, 1991). In this decidedly active role, along with Richard O'Bryant, Ph.D. candidate in the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning, I have worked very closely with Camfield residents to interject these concepts into certain aspects of the methodology, and to conceptualize and implement the project in ways that reflected our collective ways of thinking. Second, it has provided the frame through which I have analyzed and interpreted the ongoing activities at Camfield Estates. Like a lens, it has provided a basis for me to understand what has happened thus far, theorize as to why, and postulate as to what can happen moving forward. This includes an account of the challenges and opportunities of the Camfield Estates-MIT Creating Community Connections Project, as well as a discussion of the early results, lessons learned, and recommendations for similar initiatives.

As praxis, a sociocultural constructionist and asset-based approach to community technology and community building seeks to achieve positive changes in community social capital and community cultural capital, two constructs I have developed as variations of the concepts of social capital (Coleman, 1988; Mattesich & Monsey, 1997; Putnam, 1993 & 1995) and cultural capital (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977;

Lamont & Lareau, 1988; Zweigenhaft, 1993). I define community social capital as the extent to which members of a community can work and learn together effectively. I define community cultural capital as various forms of knowledge, skills, abilities, and interests, which have particular relevance or value within a community.

The research question for this study is: In what ways can community social capital be increased and community cultural capital activated through an integrated community technology and community building initiative in a low- to moderate-income housing development and its surrounding environs. This question is informed by what has happened at Camfield Estates and why it has happened, looking back. A closely related sub-question of my research is: What are the challenges and opportunities of conceptualizing and implementing an initiative that is guided by the theoretical framework of sociocultural constructionism and an asset-based approach to community technology and community building. This sub-question is informed by what can happen in other contexts (including Camfield Estates) and how it can happen, looking forward.

My hypothesis is that a sociocultural constructionist and asset-based approach to community technology and community building, can positively contribute to increasing community social capital and activating community cultural capital, as a result of residents' involvement as active, rather than passive, participants in the process.

An important distinction to note at the onset of this dissertation is that community social capital and community cultural capital are both "process" oriented outcomes, and refer to a community's capacity, or ability to improve the conditions of their neighborhood. This can also be understood as a focus on building relationships and creating community connections between various constituencies including residents, local associations and institutions, and neighborhood businesses. It is the essence of community building. Oftentimes, these connections can be leveraged to achieve "product" related outcomes, or concrete and tangible changes in the community such as a stronger educational system, better delivery of health care, reduced unemployment, or enhanced economic and business development. This can also be understood as a focus on rehabilitating physical infrastructures, improving neighborhood conditions, and enhancing the overall quality-of-life for individuals, families, and the community. It is the essence of community development.

Unlike process-oriented outcomes, which can be universally applied, generally speaking, product-related outcomes are often community-specific, and therefore, best defined by the members of the community.

What constitutes a desired outcome in one neighborhood may not apply in others and will therefore differ from initiative to initiative. Regardless, increased community social capital and activated community cultural capital are means to these ends. Also note that while community social capital and community cultural capital are community outcomes, they also fully acknowledge individual outcomes because they often fuel and directly contribute to community outcomes. Community social capital and community cultural capital encapsulate the community's capacity or ability to marshal its resources toward achieving individually- and collectively-defined goals.

My investigation of the research question is primarily descriptive in nature. It sets out to better understand the processes that can lead to increased community social capital and activated community cultural capital in the context of a community technology and community building initiative, such that said capital can be translated into so-called products, or community development. However, my investigation does not set out to understand the processes that facilitate this translation. This is done neither to elevate process nor to devalue product, but rather to focus this work on the first of two equally important outcomes. My investigation also seeks to explore the challenges and opportunities that were specific to the context within which it was situated. This is done in an attempt to tease apart those factors that may have influenced the outcomes.

My investigation of the research sub-question is primarily proscriptive in nature. It sets out to identify the challenges and opportunities of a sociocultural constructionist and asset-based approach to community technology and community building. This is done in recognition of the fact that the initiative that constitutes the basis for my inquiry has only drawn upon the ideas and principles underlying this theoretical framework. However, such an investigation does provide me with a basis from which lessons learned and recommendations for similar initiatives can be offered. My theoretical perspective enables me to interpret what has happened (and what has not happened) as a means to discern what can happen in the future.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

The study outlined herein is both timely and relevant for four reasons. First, it offers a theoretical framework, namely sociocultural constructionism and an asset-based approach to community technology and community building, that can inform broader initiatives to bridge the digital divide and alleviate poverty. Second, this study has produced a web-based, community building system, which I have co-designed with community members, the Creating Community Connections (C3) System, that demonstrates how high technology can be used to address the interests and needs of a low- to moderate-income community. Third, it has produced early qualitative and quantitative results to contribute to the growing body of data dealing with these issues. Fourth, and finally, this study offers a set of guidelines for implementing this approach in other underserved communities by presenting a detailed methodology, lessons learned, and recommendations. These elements can advance the work of community technology and community building practitioners, researchers, funders, government agencies, and public policy makers, about how to conduct an integrated community technology and community building initiative.

ORGANIZATION OF THESIS

This thesis is organized into ten chapters:

e Chapter 2: Background - presents background for the areas of community technology, including community networks, community technology centers (CTCs), and community content, and community revitalization, including community organizing, community development, and community building.

Creating Community Connections Page 38

Page 38 Creating Community Connections