Resuscitation

j o ur na l h o me pa g e:ww w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / r e s u s c i t a t i o n

European

Resuscitation

Council

Guidelines

for

Resuscitation

2015

Section

2.

Adult

basic

life

support

and

automated

external

defibrillation

Gavin

D.

Perkins

a,b,∗,

Anthony

J.

Handley

c,

Rudolph

W.

Koster

d,

Maaret

Castrén

e,

Michael

A.

Smyth

a,f,

Theresa

Olasveengen

g,

Koenraad

G.

Monsieurs

h,i,

Violetta

Raffay

j,

Jan-Thorsten

Gräsner

k,

Volker

Wenzel

l,

Giuseppe

Ristagno

m,

Jasmeet

Soar

n,

on

behalf

of

the

Adult

basic

life

support

and

automated

external

defibrillation

section

Collaborators

1 aWarwickMedicalSchool,UniversityofWarwick,Coventry,UKbCriticalCareUnit,HeartofEnglandNHSFoundationTrust,Birmingham,UK cHadstock,Cambridge,UK

dDepartmentofCardiology,AcademicMedicalCenter,Amsterdam,TheNetherlands

eDepartmentofEmergencyMedicineandServices,HelsinkiUniversityHospitalandHelsinkiUniversity,Finland fWestMidlandsAmbulanceServiceNHSFoundationTrust,Dudley,UK

gNorwegianNationalAdvisoryUnitonPrehospitalEmergencyMedicineandDepartmentofAnesthesiology,OsloUniversityHospital,Oslo,Norway hFacultyofMedicineandHealthSciences,UniversityofAntwerp,Antwerp,Belgium

iFacultyofMedicineandHealthSciences,UniversityofGhent,Ghent,Belgium jMunicipalInstituteforEmergencyMedicineNoviSad,NoviSad,Serbia

kDepartmentofAnaesthesiaandIntensiveCareMedicine,UniversityMedicalCenterSchleswig-Holstein,Kiel,Germany lDepartmentofAnesthesiologyandCriticalCareMedicine,MedicalUniversityofInnsbruck,Innsbruck,Austria mDepartmentofCardiovascularResearch,IRCCS-IstitutodiRicercheFarmacologiche“MarioNegri”,Milan,Italy nAnaesthesiaandIntensiveCareMedicine,SouthmeadHospital,Bristol,UK

Introduction

Thischaptercontains guidanceonthetechniques used dur-ingtheinitialresuscitationofanadultcardiacarrestvictim.This includes basiclife support(BLS: airway, breathing and circula-tionsupportwithouttheuseofequipmentotherthanaprotective device)andtheuseofanautomatedexternaldefibrillator(AED). Simpletechniquesusedin themanagement ofchoking (foreign bodyairwayobstruction)arealsoincluded.Guidelinesfortheuse ofmanualdefibrillatorsandstartingin-hospitalresuscitationare foundinthesectionAdvancedLifeSupportChapter.1Asummary

oftherecoverypositionisincluded,withfurtherinformation pro-videdintheFirstAidChapter.2

TheguidelinesarebasedontheILCOR2015Consensuson Sci-enceandTreatmentRecommendations(CoSTR)forBLS/AED.3The

ILCORreviewfocusedon23keytopicsleadingto32treatment rec-ommendationsinthedomainsofearlyaccessandcardiacarrest prevention,early,high-qualityCPR, and earlydefibrillation. For theseERCguidelinestheILCOR recommendationswere supple-mentedbyfocusedliteraturereviewsundertakenbyWritingGroup membersinareasnotreviewedbyILCOR.Thewritinggroupwere

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:g.d.perkins@warwick.ac.uk(G.D.Perkins).

1 The members of the Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillationsectionCollaboratorsarelistedintheCollaboratorssection.

cognisantofthecostsandpotentialconfusioncreatedbychanging guidancefrom2010,andthereforesoughttolimitchangestothose judgedtobeessentialandsupportedbynewevidence.Guidelines weredraftedbyWritingGroupmembers,thenreviewedbythe fullwritinggroupandnationalresuscitationcouncilsbeforefinal approvalbytheERCBoard.

SummaryofchangessincetheERC2010guidelines

Guidelines2015highlightsthecriticalimportanceofthe inter-actionsbetweentheemergencymedicaldispatcher,thebystander who provides CPR and the timely deployment of an auto-matedexternaldefibrillator.Aneffective,co-ordinatedcommunity responsethatdrawstheseelementstogetheriskeytoimproving survivalfromout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest(Fig.2.1).

Theemergencymedicaldispatcherplaysanimportantrolein theearlydiagnosisofcardiacarrest,theprovisionof dispatcher-assistedCPR(alsoknownastelephoneCPR),andthelocationand dispatchof anautomated external defibrillator. Thesooner the emergencyservicesarecalled,theearlierappropriatetreatment canbeinitiatedandsupported.

Theknowledge,skillsandconfidenceofbystanderswillvary accordingtothecircumstances,ofthearrest,leveloftrainingand priorexperience.

TheERCrecommendsthatthebystanderwhoistrainedandable shouldassessthecollapsedvictimrapidlytodetermineifthevictim

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.015

COMMUNITY RESPONSE

SAVES LIVES 112

Fig.2.1.Theinteractionsbetweentheemergencymedicaldispatcher,thebystander whoprovidesCPRandthetimelyuseofanautomatedexternaldefibrillatorarethe keyingredientsforimprovingsurvivalfromoutofhospitalcardiacarrest.

isunresponsiveandnotbreathingnormallyandthenimmediately alerttheemergencyservices.

Wheneverpossible,alerttheemergencyserviceswithout leav-ingthevictim.

Thevictimwhoisunresponsiveandnotbreathingnormallyis incardiacarrestandrequiresCPR.Immediatelyfollowingcardiac arrestbloodflowtothebrainisreducedtovirtuallyzero,whichmay causeseizure-likeepisodesthatmaybeconfusedwithepilepsy. Bystandersandemergencymedicaldispatchersshouldbe suspi-ciousofcardiacarrestinanypatientpresentingwithseizuresand carefullyassesswhetherthevictimisbreathingnormally.

Thewritinggroupendorses theILCORrecommendationthat allCPRprovidersshouldperformchestcompressionsforall vic-timsincardiacarrest.CPRproviderstrainedandabletoperform rescue breaths shouldcombine chest compressionsand rescue breaths.Theadditionofrescuebreathsmayprovideadditional ben-efitforchildren,forthosewhosustainanasphyxialcardiacarrest, orwhere theemergency medicalservice (EMS) response inter-valisprolonged.Ourconfidenceintheequivalencebetweenchest compression-onlyandstandardCPRisnotsufficienttochange cur-rentpractice.

Highqualitycardiopulmonaryresuscitationremainsessential toimprovingoutcomes.TheERC2015guidelineforchest compres-siondepthisthesameasthe2010guideline.CPRprovidersshould ensurechestcompressionsofadequatedepth(atleast5cmbutnot morethan6cm)witharateof100–120compressionsperminute. Allowthechesttorecoilcompletelyaftereachcompressionand minimiseinterruptionsincompressions.Whenprovidingrescue breaths/ventilationsspend approximately1sinflating thechest withsufficientvolumetoensurethechestrisesvisibly.Theratioof chestcompressionstoventilationsremains30:2.Donotinterrupt chestcompressionsformorethan10stoprovideventilations.

Defibrillationwithin3–5minofcollapsecanproducesurvival ratesashighas50–70%.Earlydefibrillationcanbeachievedthrough CPRprovidersusingpublicaccessandon-siteAEDs.Publicaccess AEDprogrammesshouldbeactivelyimplementedinpublicplaces thathaveahighdensityofcitizens,suchasairports,railway sta-tions,bus terminals,sportfacilities,shoppingmalls,offices and casinos.It is herethat cardiacarrests are oftenwitnessed, and trainedCPR providerscan beon-scenequickly.Placing AEDsin areaswhere one cardiacarrest per5 years canbe expected is consideredcost-effective,andthecostperaddedlife-yearis com-parable to other medical interventions. Past experience of the numberofcardiacarrestsinacertainarea,aswellasthe neighbour-hoodcharacteristics,mayhelpguideAEDplacement.Registration

ofpublicaccessAEDsallowsdispatcherstodirectCPRprovidersto anearbyAEDandmayhelptooptimiseresponse.

TheadultCPRsequencecanbeusedsafelyinchildrenwhoare unresponsiveandnotbreathingnormally.ForCPRproviderswith additionaltrainingamodifiedsequencewhichincludesproviding5 initialrescuebreathsbeforestartingchestcompressionsand delay-inggoingforhelpintheunlikelysituationthattherescuerisalone isevenmoresuitableforthechildanddrowningvictim.Chest com-pressiondepthsinchildrenshouldbeatleastonethirdofthedepth ofthechest(forinfantsthatis4cm,forchildren5cm).

Aforeignbody causingsevereairway obstructionisa medi-calemergency.Italmostalwaysoccurswhilstthevictimiseating ordrinkingandrequiresprompttreatment.Startbyencouraging thevictimtocough.Ifthevictimhassevereairwayobstructionor beginstotire,givebackblowsand,ifthatfailstorelievethe obstruc-tion,abdominalthrusts.Ifthevictimbecomesunresponsive,start CPRimmediatelywhilsthelpissummoned.

Cardiacarrest

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is one of theleading causesof deathinEurope.DependinghowSCAisdefined,about55–113per 100,000inhabitantsayearor350,000–700,000individualsayear areaffectedinEurope.4–6Oninitialheart-rhythmanalysis,about

25–50%ofSCAvictimshaveventricularfibrillation(VF),a percent-agethathasdeclinedoverthelast20years.7–13Itislikelythatmany

morevictimshaveVForrapidventriculartachycardia(VT)atthe timeofcollapse,butbythetimethefirstelectrocardiogram(ECG) isrecordedbyemergencymedicalservicepersonneltheirrhythm hasdeterioratedtoasystole.14,15Whentherhythmisrecordedsoon

aftercollapse,inparticularbyanon-siteAED,theproportionof

vic-timsinVFcanbeashighas76%.16,17MorevictimsofSCAsurvive

ifbystandersactimmediatelywhileVFisstillpresent. Success-fulresuscitationislesslikelyoncetherhythmhasdeterioratedto asystole.

TherecommendedtreatmentforVFcardiacarrestis immedi-atebystanderCPRandearlyelectricaldefibrillation.Mostcardiac arrests of non-cardiac origin have respiratory causes, such as drowning (among them many children) and asphyxia. Rescue breathsaswellaschestcompressionsarecriticalforsuccessful resuscitationofthesevictims.

Thechainofsurvival

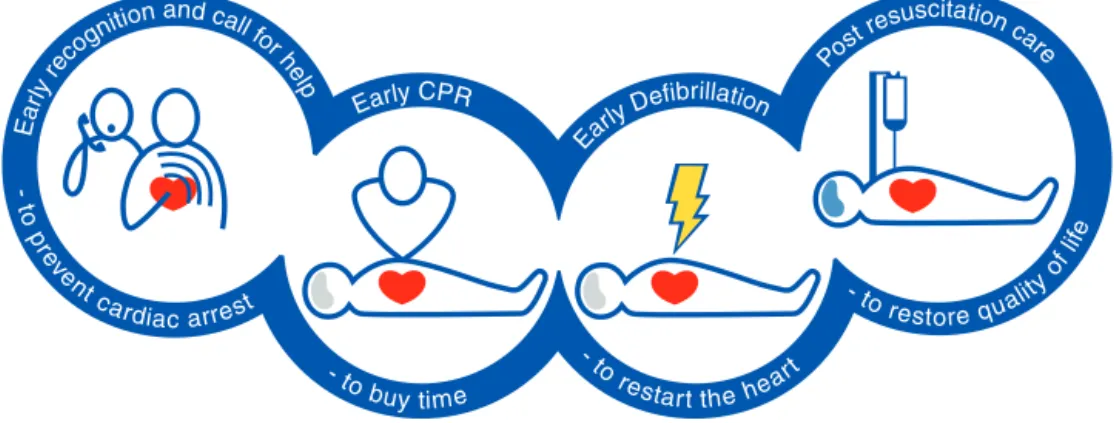

TheChainofSurvivalsummarisesthevitallinksneededfor suc-cessfulresuscitation(Fig.2.2).Mostoftheselinksapplytovictims ofbothprimarycardiacandasphyxialarrest.18

Earlyrecognitionandcallforhelp

Chestpainshouldberecognisedasasymptomofmyocardial ischaemia.Cardiacarrestoccursinaquartertoathirdofpatients withmyocardialischaemiawithinthefirsthourafteronsetofchest pain.19Recognisingthecardiacoriginofchestpain,andcallingthe

emergencyservicesbeforeavictimcollapses,enablesthe emer-gencymedical servicetoarrivesooner,hopefully beforecardiac arresthasoccurred,thusleadingtobettersurvival.20–23

Once cardiac arrest has occurred, early recognition is criti-caltoenablerapid activationoftheEMSand promptinitiation of bystander CPR. The key observations are unresponsiveness

andnotbreathingnormally.Emergencymedicaldispatcherscan improverecognitionbyfocusingonthesekeywords.

Fig.2.2.Thechainofsurvival.

EarlybystanderCPR

TheimmediateinitiationofCPRcandoubleorquadruple sur-vival from cardiac arrest.20,24–28 If able, bystanders with CPR

trainingshouldgivechestcompressionstogetherwithventilations. Whenabystander hasnotbeentrained in CPR,theemergency medical dispatcher should instruct him or her to give chest-compression-onlyCPRwhileawaitingthearrivalofprofessional help.29–31

Earlydefibrillation

Defibrillationwithin3–5minofcollapsecanproducesurvival ratesashighas50–70%.Thiscanbeachievedbypublicaccessand onsiteAEDs.13,17,32,33Eachminuteofdelaytodefibrillationreduces

theprobabilityofsurvivaltodischargeby10–12%.Thelinksinthe chainworkbettertogether:whenbystanderCPRisprovided,the declineinsurvivalismoregradualandaverages3–4%perminute delaytodefibrillation.20,24,34

Earlyadvancedlifesupportandstandardisedpost-resuscitation care

Advanced life support with airway management, drugs and correctingcausalfactorsmaybeneededifinitialattemptsat resus-citation are un-successful. The quality of treatmentduring the post-resuscitationphaseaffectsoutcomeandareaddressedinthe adultadvancedlifesupportandpostresuscitationcarechapters.1,35

Thecriticalneedforbystanderstoact

In most communities, the median time from emergency callto emergency medical service arrival (responseinterval) is

5–8min,16,36–38or8–11mintoafirstshock.13,27Duringthistime

thevictim’ssurvivaldependsonbystanderswhoinitiateCPRand useanautomatedexternaldefibrillator(AED).

Victimsof cardiacarrest needimmediateCPR. Thisprovides a small but critical blood flow to the heart and brain. It also increasesthelikelihood that theheartwill resumeaneffective rhythmand pumpingpower.Chestcompressionsare especially importantifashockcannotbedeliveredwithinthefirstfew min-utesaftercollapse.39Afterdefibrillation,iftheheartisstillviable,

itspacemakeractivityresumesandproducesanorganisedrhythm followedbymechanicalcontraction.Inthefirstminutesafter ter-minationofVF,theheartrhythmmaybeslow,andtheforceof contractionsweak;chestcompressionsmust becontinueduntil adequatecardiacfunctionreturns.

UseofanAEDbylayCPRprovidersincreasessurvivalfrom car-diacarrestinpublicplaces.16AEDuseinresidentialareasisalso

increasing.40AnAEDusesvoicepromptstoguidetheCPRprovider,

analysethecardiacrhythmandinstructtheCPRprovidertodeliver ashockifVForrapidventriculartachycardia(VT)isdetected.They areaccurateandwilldeliverashockonlywhenVF(orrapidVT)is present.41,42

Recognitionofcardiacarrest

Recognisingcardiacarrestcanbechallenging.Bothbystanders and emergency call handlers (emergency medical dispatchers) havetodiagnosecardiacarrestpromptlyinordertoactivatethe chainofsurvival.Checkingthecarotidpulse(oranyotherpulse) hasprovedtobeaninaccuratemethodforconfirmingthepresence orabsenceofcirculation.43–47

Agonalbreathsareslowanddeepbreaths,frequentlywitha characteristicsnoringsound.Theyoriginatefromthebrainstem, thepartofthebrainthatremainsfunctioningforsomeminutes evenwhendeprivedofoxygen.Thepresenceofagonalbreathing canbeerroneouslyinterpretedasevidencethatthereisa circu-lationand CPRisnotneeded.Agonalbreathingmaybepresent inupto40%ofvictimsinthefirstminutesaftercardiacarrest, andifrespondedtoasasignofcardiacarrest,isassociatedwith highersurvivalrates.48Thesignificanceofagonalbreathingshould

beemphasisedduringbasiclifesupporttraining.49,50Bystanders

shouldsuspectcardiacarrestandstartCPRifthevictimis unre-sponsiveandnotbreathingnormally.

Immediatelyfollowingcardiacarrest,bloodflowtothebrainis reducedtovirtuallyzero,whichmaycauseseizure-likeepisodes thatcanbeconfusedwithepilepsy.Bystandersshouldbe suspi-ciousofcardiacarrestinanypatientpresentingwithseizures.51,52

Although bystanderswho have witnessedcardiac arrest events reportchangesinthevictims’skincolour,notablypallorandbluish changesassociatedwithcyanosis,thesechangesarenotdiagnostic ofcardiacarrest.51

Roleoftheemergencymedicaldispatcher

Theemergencymedicaldispatcherplaysacriticalroleinthe diagnosisofcardiacarrest,theprovisionofdispatcherassistedCPR (alsoknownastelephoneCPR),thelocationanddispatchofan auto-matedexternal defibrillatoranddispatchofa highpriorityEMS response.Thesoonertheemergencyservicesarecalled,theearlier appropriatetreatmentcanbeinitiatedandsupported.

Dispatcherrecognitionofcardiacarrest

Confirmation of cardiac arrest, at the earliest opportunity is critical. If the dispatcher recognises cardiac arrest, survival is more likely becauseappropriate measures canbe taken.53,54

Enhancingdispatcherabilitytoidentifycardiacarrest,and optimis-ingemergencymedicaldispatcherprocesses,maybecost-effective solutionstoimproveoutcomesfromcardiacarrest.

Useofscripteddispatchprotocolswithinemergencymedical communicationcentres,includingspecificquestionstoimprove cardiac arrest recognition may be helpful. Patients who are

unresponsiveandnotbreathingnormallyshouldbepresumedto beincardiacarrest.Adherencetosuchprotocolsmayhelpimprove cardiacarrestrecognition,9,55–57whereasfailuretoadhereto

pro-tocolsreducesratesofcardiacarrestrecognitionbydispatchersas wellastheprovisionoftelephone-CPR.58–60

Obtaining an accurate description of the victim’s breathing patternischallengingfor dispatchers.Agonalbreathing isoften present, and callers may mistakenly believe the victim is still breathingnormally.9,60–68Offeringdispatchersadditional

educa-tion,specificallyaddressingtheidentificationandsignificanceof agonalbreathing,canimprovecardiacarrestrecognition,increase theprovision of telephone-CPR,67,68 and reducethe number of

missedcardiacarrestcases.64

Askingquestionsregardingtheregularityorpatternof breath-ingmayhelpimproverecognitionofabnormalbreathingandthus identificationofcardiacarrest.Iftheinitialemergencycallisfora personsufferingseizures,thecalltakershouldbehighlysuspicious ofcardiacarrest,evenifthecallerreportsthatthevictimhasaprior historyofepilepsy.61,69

DispatcherassistedCPR

BystanderCPRratesarelowinmanycommunities. Dispatcher-assistedCPR(telephone-CPR)instructionshavebeendemonstrated to improve bystander CPR rates,9,56,70–72 reduce the time to

firstCPR,56,57,68,72,73increasethenumberofchestcompressions

delivered70 and improve patient outcomes following

out-of-hospitalcardiacarrest(OHCA)inallpatientgroups.9,29–31,57,71,74

Dispatchersshouldprovidetelephone-CPRinstructions inall casesofsuspectedcardiacarrestunlessatrainedproviderisalready deliveringCPR.Whereinstructionsarerequiredforanadultvictim, dispatchersshouldprovidechest-compression-onlyCPR instruc-tions.

Ifthevictimisa child,dispatchersshouldinstructcallersto provide both ventilations and chest compressions. Dispatchers shouldthereforebetrainedtoprovideinstructionsforboth tech-niques.

AdultBLSsequence

Thesequenceofstepsfortheinitialassessmentandtreatmentof theunresponsivevictimaresummarisedinFig.2.3.Thesequence ofstepstakesthereaderthroughrecognitionofcardiacarrest, call-ingEMS,startingCPRandusinganAED.Thenumberofstepshas beenreducedtofocusonthekeyactions.Theintentoftherevised algorithmistopresentthestepsinalogicalandconcisemanner thatiseasyforalltypesofrescuerstolearn,rememberandperform.

Fig.2.4 presents the detailed step-by-step sequence for the trainedprovider.Itcontinuestohighlighttheimportanceof ensur-ingrescuer,victimandbystandersafety.Callingforadditionalhelp (ifrequired)isincorporatedinthealertingemergencyservicesstep below.Forclaritythealgorithmispresentedasalinearsequence ofsteps.Itisrecognisedthattheearlystepsofcheckingresponse, openingtheairway,checkingforbreathingandcallingthe emer-gencymedicaldispatchermaybeaccomplishedsimultaneouslyor inrapidsuccession.

Those who are not trained to recognise cardiac arrest and startCPRwouldnotbeawareoftheseguidelinesandtherefore requiredispatcherassistancewhenever theymakethedecision

Unresponsive and

not breathing normally

Call Emergency Services

Give 30 chest compressions

Give 2 rescue breaths

Continue CPR 30:2

As soon as AED arrives - switch

it on and follow instructions

Fig.2.3.TheBLS/AEDAlgorithm.

to call 112. These guidelines do not therefore include specific recommendationsforthosewhoarenottrainedtorecognise car-diacarrestandstartCPR.

Theremainderofthissectionprovidessupplemental informa-tiononsomeofthekeystepswithintheoverallsequence. Openingtheairwayandcheckingforbreathing

Thetrainedprovidershouldassessthecollapsedvictimrapidly todetermineiftheyareresponsiveandbreathingnormally.

Opentheairwayusingtheheadtiltandchinlifttechniquewhilst assessingwhetherthepersonisbreathingnormally.Donotdelay assessmentbycheckingfor obstructionsintheairway.Thejaw thrustandfingersweeparenolongerrecommendedforthelay provider.Checkfor breathingusingthetechniquesdescribedin

Fig.2.4notingthecriticalimportanceofrecognisingagonal breath-ingdescribedabove.

Alertingemergencyservices

112istheEuropeanemergencyphonenumber,available every-where in theEU,free of charge. It ispossible tocall112from fixedand mobilephonestocontact anyemergency service:an ambulance,thefirebrigadeorthepolice.SomeEuropeancountries provideanalternativedirectaccessnumbertoemergencymedical services,whichmaysavetime.Bystandersshouldthereforefollow nationalguidelinesontheoptimalphonenumbertouse.

Earlycontactwiththeemergencyserviceswillfacilitate dis-patcherassistanceintherecognitionofcardiacarrest,telephone instructiononhowtoperformCPR,emergencymedicalservice/first responderdispatch,andonlocatinganddispatchingofanAED.75–78

Ifpossible,stay withthevictimwhilecallingtheemergency services.Ifthephonehasaspeakerfacilityswitchittospeakeras thiswillfacilitatecontinuousdialoguewiththedispatcher includ-ing(ifrequired)CPRinstructions.79ItseemsreasonablethatCPR

Fig.2.4.(Continued).

trainingshouldincludehowtoactivatethespeakerphone.80

Addi-tionalbystandersmaybeusedtohelpcalltheemergencyservices. Startingchestcompressions

InadultsneedingCPR,thereisahighprobabilityofaprimary cardiaccause.Whenbloodflowstopsaftercardiacarrest,theblood in thelungs and arterial systemremains oxygenatedfor some minutes.Toemphasisethepriorityofchestcompressions,itis rec-ommendedthatCPRshouldstartwithchestcompressionsrather thaninitialventilations.Manikinstudiesindicatethatthisis asso-ciatedwithashortertimetocommencementofCPR.81–84

Whenprovidingmanualchestcompressions: 1.Delivercompressions‘inthecentreofthechest’.

2.Compresstoadepthofatleast5cmbutnotmorethan6cm. 3.Compressthechestatarateof100–120min−1withasfew

inter-ruptionsaspossible.

4.Allowthechesttorecoilcompletelyaftereachcompression;do notleanonthechest.

Handposition

Experimental studies show better haemodynamic responses whenchestcompressionsareperformedonthelowerhalfofthe sternum.85–87Itisrecommendedthatthislocationbetaughtina

simplifiedway,suchas,“placetheheelofyourhandinthecentre ofthechestwiththeotherhandontop”.Thisinstructionshouldbe accompaniedbyademonstrationofplacingthehandsonthelower halfofthesternum.88,89

ChestcompressionsaremosteasilydeliveredbyasingleCPR provider kneeling by the side of the victim, as this facilitates movementbetweencompressionsandventilationswithminimal interruptions. Over-the-head CPR for single CPR providers and

straddle-CPRfortwoCPRprovidersmaybeconsideredwhenitis notpossibletoperformcompressionsfromtheside,forexample whenthevictimisinaconfinedspace.90,91

Compressiondepth

Fearof doingharm, fatigueand limitedmusclestrength fre-quentlyresultinCPRproviderscompressingthechestlessdeeply than recommended.Four observational studies,publishedafter the2010Guidelines,suggestthatacompressiondepthrangeof 4.5–5.5cminadultsleadstobetteroutcomesthanallother com-pressiondepthsduringmanualCPR.92–95Basedonananalysisof

9136patients,compressiondepthsbetween40and55mmwith apeak at46mm,wereassociatedwithhighestsurvivalrates.94

Thereisalsoevidencefrom oneobservationalstudysuggesting thatacompressiondepthofmorethan6cmisassociatedwithan increasedrateofinjuryinadultswhencomparedwithcompression depthsof5–6cmduringmanualCPR.96TheERCendorsestheILCOR

recommendationthatitisreasonabletoaimforachest compres-sionofapproximately5cmbutnotmorethan6cmintheaverage sizedadult.Inmakingthis recommendationtheERCrecognises thatitcanbedifficulttoestimatechestcompressiondepthandthat compressionsthataretooshallowaremoreharmfulthan compres-sionsthataretoodeep.TheERCthereforedecidedtoretainthe2010 guidancethatchestcompressionsshouldbeatleast5cmbutnot morethan6cm.Trainingshouldcontinuetoprioritiseachieving adequatecompressiondepth.

Compressionrate

Chestcompressionrateisdefinedastheactualrateof compres-sionsbeinggivenatanyonetime.Itdiffersfromthenumberofchest compressionsinaspecifictimeperiod,whichtakesintoaccount anyinterruptionsinchestcompressions.

rate of 100–120min , compared to >140, 120–139, <80 and 80–99min−1.Veryhighchestcompressionrateswereassociated with declining chest compression depths.97,98 The ERC

recom-mends,therefore,thatchest compressionsshouldbeperformed atarateof100–120min−1.

Minimisingpausesinchestcompressions

Delivery of rescue breaths, shocks, ventilations and rhythm analysisleadtopausesinchestcompressions.Pre-andpost-shock pausesoflessthan10s,andchestcompressionfractions>60%are associatedwithimprovedoutcomes.99–103 Pausesinchest

com-pressionsshouldbeminimised,byensuringCPRproviderswork effectivelytogether.

Firmsurface

CPRshouldbeperformedonafirmsurfacewheneverpossible. Air-filledmattressesshouldberoutinelydeflatedduringCPR.104

Theevidencefortheuseofbackboardsisequivocal.105–109Ifa

back-boardisused,takecaretoavoidinterruptingCPRanddislodging intravenouslinesorothertubesduringboardplacement.

Chestwallrecoil

Leaningonthechestpreventingfullchestwallrecoiliscommon duringCPR.110,111Allowingcompleterecoilofthechestaftereach

compressionresultsinbettervenousreturntothechestandmay improvetheeffectivenessofCPR.110,112–114CPRprovidersshould,

therefore,takecaretoavoidleaningaftereachchestcompression.

Dutycycle

Optimaldutycycle(ratioofthetimethechestiscompressed tothe total time from one compression tothe next) hasbeen studiedinanimalmodelsandsimulationstudieswithinconsistent results.115–123Arecenthumanobservationalstudyhaschallenged

thepreviouslyrecommendeddutycycleof 50:50bysuggesting compressionphases>40%mightnotbefeasible,andmaybe associ-atedwithdecreasedcompressiondepth.124ForCPRproviders,the

dutycycleisdifficulttoadjust,andislargelyinfluencedbyother chestcompressionparameters.119,124Inreviewing theevidence,

theERCacknowledgesthereisverylittleevidencetorecommend anyspecificdutycycleand,therefore,insufficientnewevidenceto promptachangefromthecurrentlyrecommendedratioof50%.

Feedbackoncompressiontechnique

TheuseofCPRfeedbackandpromptdevicesduringCPRin clin-icalpractice is intended toimprove CPRquality as a meansof increasingthechancesofROSCandsurvival.125,126Theformsof

feedbackincludevoiceprompts,metronomes,visualdials, numer-icaldisplays,waveforms,verbalprompts,andvisualalarms.

TheeffectofCPRfeedbackorpromptdeviceshasbeenstudied intworandomisedtrials92,127and11observationalstudies.128–138

Noneofthesestudiesdemonstratedimprovedsurvivaltodischarge withfeedback,andonlyonefoundasignificantlyhigherROSCrate inpatientswherefeedbackwasused.However,inthisstudy feed-backwasactivatedatthediscretionofthephysicianandnodetails ofthedecision-makingprocesstoactivateornotactivatefeedback wereprovided.136TheuseofCPRfeedbackorpromptdevices

dur-ingCPRshouldonlybeconsideredaspartofabroadersystemof carethatshouldincludecomprehensiveCPRqualityimprovement initiatives,138,139ratherthanasanisolatedintervention.

Innon-paralysed,gaspingpigswithunprotected,unobstructed airways,continuous-chest-compressionCPRwithoutartificial ven-tilationresultedinimprovedoutcome.140Gaspingmaybepresent

earlyaftertheonsetofcardiacarrestinaboutonethirdofhumans, thusfacilitatinggasexchange.48DuringCPRinintubatedhumans,

however,themediantidalvolumeperchestcompressionwasonly about40mL,insufficientforadequateventilation.141Inwitnessed

cardiacarrestwithventricularfibrillation,immediatecontinuous chest compressions tripledsurvival.142 Accordingly, continuous

chest compressions maybe most beneficial in the early, ‘elec-tric’and‘circulatory’phasesofCPR,whileadditionalventilation becomesmoreimportantinthelater,‘metabolic’phase.39

DuringCPR,systemic bloodflow,andthusblood flowtothe lungs,issubstantiallyreduced,solowertidalvolumesand respi-ratoryratesthannormalcanmaintaineffectiveoxygenationand ventilation.143–146 Whentheairway is unprotected,a tidal

vol-ume of 1L produces significantly more gastric inflation than a tidal volume of 500mL.147 Inflation durations of 1sare

feasi-blewithoutcausingexcessivegastricinsufflation.148Inadvertent

hyperventilationduringCPRmayoccurfrequently,especiallywhen usingmanualbag-valve-maskventilationin aprotectedairway. While this increasedintrathoracic pressure149 and peak airway

pressure,150acarefullycontrolledanimalexperimentrevealedno

adverseeffects.151

FromtheavailableevidencewesuggestthatduringadultCPR tidal volumes of approximately 500–600mL (6–7mLkg−1) are delivered.Practically,thisisthevolumerequiredtocausethechest torisevisibly.152CPRprovidersshouldaimforaninflation

dura-tionofabout1s,withenoughvolumetomakethevictim’schest rise,butavoidrapidorforcefulbreaths.Themaximum interrup-tioninchestcompressiontogivetwobreathsshouldnotexceed 10s.153Theserecommendationsapplytoallformsofventilation

duringCPRwhentheairwayisunprotected,including mouth-to-mouthandbag-maskventilation,withandwithoutsupplementary oxygen.

Mouth-to-noseventilation

Mouth-to-nose ventilation is an acceptable alternative to mouth-to-mouthventilation.154Itmaybeconsideredifthevictim’s

mouthisseriouslyinjuredorcannotbeopened,theCPRprovideris assistingavictiminthewater,oramouth-to-mouthsealisdifficult toachieve.

Mouth-to-tracheostomyventilation

Mouth-to-tracheostomyventilationmaybeusedforavictim withatracheostomytubeortrachealstomawhorequiresrescue breathing.155

Compression–ventilationratio

Animaldatasupporta ratioofcompressiontoventilationof greaterthan15:2.156–158 Amathematicalmodel suggeststhata

ratioof30:2providesthebestcompromise betweenbloodflow andoxygendelivery.159,160Aratioof30:2wasrecommendedin

Guidelines2005and2010forthesingleCPRproviderattempting resuscitationofanadult.Thisdecreasedthenumberof interrup-tionsincompressionandtheno-flowfraction,161,162andreduced

the likelihood of hyperventilation.149,163 Several observational

studieshavereportedslightlyimprovedoutcomesafter implemen-tationoftheguidelinechanges,whichincludedswitchingfroma compressionventilationratioof15:2–30:2.161,162,164,165 TheERC

continues,therefore,torecommendacompressiontoventilation ratioof30:2.

Compression-onlyCPR

Animalstudieshaveshownthatchest-compression-onlyCPR maybeaseffectiveascombinedventilationandcompressionin thefirstfewminutesafternon-asphyxialarrest.140,166Animaland

mathematicalmodelstudiesofchest-compression-onlyCPRhave alsoshownthatarterialoxygenstoresdepletein2–4min.158,167If

theairwayisopen,occasionalgaspsandpassivechestrecoilmay providesomeairexchange.48,141,168–170

Observationalstudies,classifiedmostlyasverylow-quality evi-dence,havesuggestedequivalenceofchest-compression-onlyCPR andchestcompressionscombinedwithrescuebreathsinadults withasuspectedcardiaccausefortheircardiacarrest.26,171–182

TheERChascarefullyconsideredthebalancebetween poten-tialbenefitand harmfrom compression-only CPRcompared to standardCPRthatincludesventilation.Ourconfidenceinthe equiv-alencebetweenchest-compression-onlyandstandardCPRisnot sufficienttochangecurrentpractice.TheERC,therefore,endorses theILCORrecommendations that allCPR providersshould per-formchest compressionsfor all patientsin cardiac arrest. CPR providerstrainedandabletoperformrescuebreathsshould per-formchestcompressionsandrescuebreathsasthismayprovide additionalbenefitforchildrenandthosewhosustainan asphyx-ialcardiacarrest175,183,184orwheretheEMSresponseintervalis

prolonged.179

Useofanautomatedexternaldefibrillator

AEDs are safe and effective when used by laypeople with minimalornotraining.185 AEDsmake itpossibletodefibrillate

many minutes before professional help arrives. CPR providers shouldcontinueCPRwithminimalinterruptionofchest compres-sionswhile attachinganAED andduringitsuse. CPRproviders shouldconcentrateonfollowingthevoicepromptsimmediately when they are spoken, in particular resuming CPR as soon as instructed, and minimizing interruptions in chest compression. Indeed,pre-shockandpost-shockpausesinchestcompressions shouldbeasshortaspossible.99,100,103,186StandardAEDsare

suit-ableforuseinchildrenolderthan8years.187–189

Forchildrenbetween1and8yearspaediatricpadsshouldbe used,togetherwithanattenuatororapaediatricmodeifavailable; ifthesearenotavailable,theAEDshouldbeusedasitis.Thereare afewcasereportsofsuccessfuluseofAEDSinchildrenagesless than1year.190,191Theincidenceofshockablerhythmsininfants

isverylowexceptwhenthereiscardiacdisease.187–189,192–195In

theserarecases,ifanAEDistheonlydefibrillatoravailable,itsuse shouldbeconsidered(preferablywithadoseattenuator). CPRbeforedefibrillation

Theimportanceof immediatedefibrillationhasalwaysbeen emphasisedinguidelinesandduringteaching,andisconsidered tohavea majorimpactonsurvivalfromventricularfibrillation. Thisconceptwaschallengedin2005becauseevidencesuggested thataperiodofupto180sofchestcompressionbefore defibrilla-tionmightimprovesurvivalwhentheEMSresponsetimeexceeded

4–5min.196,197Threemorerecenttrialshavenotconfirmedthis

survivalbenefit.198–200 Ananalysisofonerandomised trial

sug-gestedadeclineinsurvivaltohospitaldischargebyaprolonged periodofCPR(180s)anddelayeddefibrillationinpatientswith ashockableinitialrhythm.200 Yet,forEMSagencieswithhigher

baselinesurvival-to-hospitaldischargerates(definedas>20%for aninitialshockablerhythm),180sofCPRpriortodefibrillationwas morebeneficialcomparedtoashorterperiodofCPR(30–60s).201

The ERC recommends that CPR should be continued while a

defibrillatororAEDisbeingbroughton-siteandapplied,but defi-brillationshouldnotbedelayedanylonger.

Intervalbetweenrhythmchecks

The2015ILCORConsensusonSciencereportedthatthereare currentlynostudies that directlyaddress thequestionof opti-malintervalsbetweenrhythmchecks,andtheireffectonsurvival: ROSC;favourableneurologicalorfunctionaloutcome;survivalto discharge;coronaryperfusionpressureorcardiacoutput.

InaccordancewiththeILCORrecommendation,andfor consis-tencywithpreviousguidelines,theERCrecommendsthatchest compressionsshouldbepausedeverytwominutestoassessthe cardiacrhythm.

Voiceprompts

ItiscriticallyimportantthatCPRproviderspayattentiontoAED voicepromptsandfollowthemwithoutanydelay.Voiceprompts areusuallyprogrammable,anditisrecommendedthattheybeset inaccordancewiththesequenceofshocksandtimings forCPR givenabove.Theseshouldincludeatleast:

1.minimisepausesinchestcompressionsforrhythmanalysisand charging;

2.asingleshockonly,whenashockablerhythmisdetected; 3.avoicepromptforimmediateresumptionofchestcompression

aftertheshockdelivery;

4.aperiod of2minofCPRbeforethenextvoicepromptto re-analysetherhythm.

DevicesmeasuringCPRqualitymayinadditionprovide real-timeCPRfeedbackandsupplementalvoice/visualprompts.

The duration of CPR between shocks, as well as the shock sequenceandenergylevelsarediscussedfurtherintheAdvanced LifeSupportChapter.1

Inpractice,AEDsareusedmostlybytrainedrescuers,where thedefaultsettingofAEDpromptsshouldbeforacompressionto ventilationratioof30:2.

If(inanexception)AEDsare placedina settingwhere such trainedrescuersareunlikelytobeavailableorpresent,theowner ordistributormaychoosetochangethesettingstocompression only.

Fully-automaticAEDs

Havingdetectedashockablerhythm,afullyautomaticAEDwill deliverashockwithoutfurtheractionfromtheCPRprovider.One manikinstudyshowedthatuntrainednursingstudentscommitted fewersafetyerrorsusingafullyautomaticAEDcomparedwitha semi-automaticAED.202Asimulatedcardiacarrestscenarioona

manikinshowedthatsafetywasnotcompromisedwhenuntrained layCPRprovidersusedafullyautomaticAEDratherthana semi-automaticAED.203Therearenohumandatatodeterminewhether

thesefindingscanbeappliedtoclinicaluse. Publicaccessdefibrillation(PAD)programmes

Theconditionsforsuccessfulresuscitationinresidentialareas arelessfavourablethaninpublicareas:fewerwitnessedarrests, lowerbystanderCPR ratesand,asa consequence,fewer shock-ablerhythmsthaninpublicplaces.Thislimitstheeffectiveness ofAED usefor victimsathome.204 Moststudiesdemonstrating

able,victimswere defibrillatedmuch sooner and witha better chanceof survival.16,209 However, anAED delivereda shock in

only 3.7%209 or 1.2%16 of all cardiac arrests.There wasa clear

inverserelationshipintheJapanesestudybetweenthenumber ofAEDsavailable persquare km andthe intervalbetween col-lapseandthefirstshock,leadingtoapositiverelationshipwith survival.

PublicaccessAEDprogrammesshould,therefore,beactively implementedinpublicplaceswithahighdensityandmovement ofcitizenssuchasairports,railwaystations,busterminals,sport facilities,shoppingmalls,officesandcasinoswherecardiacarrests areusuallywitnessedand trainedCPRproviderscanquicklybe onscene. Thedensity and location of AEDsrequired for a suf-ficientlyrapid responseisnotwellestablished,especially when cost-effectivenessisaconsideration.Factorssuchasexpected inci-dence of cardiac arrest, expected number of life-years gained, andreduction inresponsetime ofAED-equippedCPR providers comparedtothatoftraditionalEMSshouldinformthisdecision. PlacementofAEDsinareaswhereonecardiacarrestper5years canbeexpectedis consideredcost-effectiveand comparableto othermedicalinterventions.210–212Forresidentialareas,past

expe-rience may help guide AED placement, as may neighbourhood characteristics.213,214RegistrationofAEDsforpublicaccess,sothat

dispatcherscandirect CPRproviderstoanearbyAED,mayalso helptooptimiseresponse.215Costsavingisalsopossible,asearly

defibrillationand on-siteAEDdefibrillationmayresultinlower in-hospitalcost.216,217

ThefullpotentialofAEDshasnotyetbeenachieved,because theyare mostly used in public settings, yet60–80% of cardiac arrestsoccurathome.TheproportionofpatientsfoundinVFis lowerathomethaninpublicplaces,howevertheabsolute num-berofpotentiallytreatablepatientsishigherathome.204 Public

accessdefibrillation(PAD)rarelyreachesvictimsathome.208

Dif-ferentstrategies,therefore,arerequiredforearlydefibrillationin residentialareas.Dispatchedfirstresponders,suchaspoliceand firefighterswill,ingeneral,havelongerresponsetimes,butthey havethepotentialtoreachthewholepopulation.17,36Thelogistic

problemforfirstresponderprogrammesisthattheCPRprovider needstoarrive,not justearlier thanthetraditionalambulance, butwithin5–6minoftheinitialcall,toenableattempted defi-brillationintheelectricalorcirculatoryphaseofcardiacarrest.39

With longerdelays, the survival benefit decreases: a few min-utes gain intime will haveless impact whena first responder arrivesmorethan10minafterthecall.34,218 DispatchedlayCPR

providers, local to the victim and directed to a nearby AED, mayimprovebystanderCPRrates33andhelpreducethetimeto

defibrillation.40

WhenimplementinganAEDprogramme,communityand pro-gramme leaders should consider factors such as development of a team with responsibility for monitoring, maintaining the devices,trainingandretrainingindividualswhoarelikelytouse theAED,andidentificationofagroupofvolunteerindividualswho arecommittedtousingtheAEDforvictimsofcardiacarrest.219

Fundsmust beallocatedona permanent basisto maintainthe programme.

ProgrammesthatmakeAEDsavailableinresidentialareashave onlybeenevaluatedforresponsetime,notforsurvivalbenefit.40

Theacquisition ofan AEDfor individual useathome,even for those considered at high risk of sudden cardiac arrest is not effective.220

Thespecialcircumstanceschapterprovidestheevidence under-pinningtheERCrecommendationthatAEDsshouldbemandatory onboardallcommercialaircraftinEurope,includingregionaland low-costcarriers.221

simple and clearsignageindicating thelocation ofan AEDand the fastest way to it is important. ILCOR has designed such an AED sign that may be recognised worldwide and this is recommended.222

In-hospitaluseofAEDs

Therearenopublishedrandomisedtrialscomparingin-hospital useofAEDswithmanualdefibrillators.Twoolder,observational studiesof adultswithin-hospital cardiacarrestfrom shockable rhythmsshowedhighersurvival-to-hospitaldischargerateswhen defibrillationwasprovidedthroughanAEDprogrammethanwith manual defibrillation alone.223,224 A more recent observational

studyshowedthatanAEDcouldbeusedsuccessfullybeforethe arrivalofthehospitalresuscitationteam.225 Threeobservational

studiesshowednoimprovementsinsurvivaltohospitaldischarge for in-hospital adult cardiac arrest when using an AED com-paredwithmanualdefibrillation.226–228Inoneofthesestudies,226

patientsintheAEDgroupwithnon-shockablerhythmshadalower survival-to-hospital discharge rate compared withthose in the manualdefibrillatorgroup(15%vs.23%;P=0.04).Anotherlarge observational study of 11,695patients from 204hospitals also showed that in-hospital AED use was associated with a lower survival-to-dischargeratecomparedwithnoAEDuse(16.3%vs. 19.3%;adjustedrateratio[RR],0.85;95%confidenceinterval[CI], 0.78–0.92;P<0.001).229Fornon-shockablerhythms,AEDusewas

associatedwithlowersurvival(10.4%vs.15.4%;adjustedRR,0.74; 95%CI,0.65–0.83;P<0.001),andasimilarsurvivalratefor shock-ablerhythms,(38.4%vs.39.8%;adjustedRR,1.00;95%CI,0.88–1.13; P=0.99).This suggeststhat AEDs maycause harmful delays in starting CPR,orinterruptions inchest compressionsin patients with non-shockable rhythms.230 Only a small proportion (less

than20%)ofin-hospitalcardiacarrestshaveaninitialshockable rhythm.229,231,232

WerecommendtheuseofAEDsinthoseareasofthehospital wherethereisariskofdelayeddefibrillation,233 becauseit will

takeseveralminutesforaresuscitationteamtoarrive,andfirst respondersdonothaveskillsinmanualdefibrillation.Thegoalis toattemptdefibrillationwithin3minofcollapse.Inhospitalareas wherethereisrapidaccesstomanualdefibrillation,eitherfrom trainedstafforaresuscitationteam,manualdefibrillationshould beusedinpreferencetoanAED.Whicheverdefibrillationtechnique ischosen(andsomehospitalsmaychoosetohavedefibrillators thatofferbothanAEDandmanualmode)aneffectivesystemfor trainingandretrainingshouldbeinplace.232,234Sufficient

health-careprovidersshouldbetrainedtoenablethegoalofproviding thefirstshockwithin3minofcollapseanywhereinthehospital. Hospitalsshouldmonitorcollapse-to-firstshockintervalsandaudit resuscitationoutcomes.

RiskstotheCPRproviderandrecipientsofCPR

RiskstothevictimwhoreceivesCPRwhoisnotincardiacarrest ManyCPRprovidersdonotinitiateCPRbecausetheyare con-cernedthatdeliveringchestcompressionstoavictimwhoisnotin cardiacarrestwillcauseseriouscomplications.Threestudieshave investigatedtheriskofCPRinpersonsnotincardiacarrest.235–237

Pooleddatafromthesethreestudies,encompassing345patients, foundanincidenceofbonefracture(ribsandclavicle)of1.7%(95% CI0.4–3.1%),painintheareaofchestcompression8.7%(95%CI 5.7–11.7%),andnoclinicallyrelevantvisceralinjury.BystanderCPR extremelyrarelyleadstoseriousharminvictimswhoare even-tuallyfoundnottobeincardiacarrest.CPRprovidersshouldnot,

therefore,bereluctanttoinitiateCPRbecauseofconcernofcausing harm.

RiskstothevictimwhoreceivesCPRwhoisincardiacarrest Asystematicreviewofskeletalinjuriesaftermanualchest com-pressionreportsanincidenceofribfracturesrangingfrom13%to 97%,andofsternalfracturesfrom1%to43%.238 Visceralinjuries

(lung,heart,abdominalorgans)occurlessfrequentlyandmayor maynotbeassociatedwithskeletalinjury.239Injuriesaremore

commonwhenthedepthofchestcompressionexceeds6cminthe averageadult.96

RiskstotheCPRproviderduringtrainingandduringreal-lifeCPR ObservationalstudiesoftrainingoractualCPRperformanceand casereportshavedescribedrareoccurrencesofmusclestrain,back symptoms,shortnessofbreath,hyperventilation,pneumothorax, chestpain,myocardialinfarctionandnerveinjury.240,241The

inci-denceof theseeventsis verylow, and CPR trainingand actual performanceissafeinmostcircumstances.242Individuals

under-takingCPRtrainingshouldbeadvisedofthenatureandextentofthe physicalactivityrequiredduringthetrainingprogramme.Learners andCPRproviderswhodevelopsignificantsymptoms(e.g.chest painorsevereshortnessofbreath)duringCPRtrainingshouldbe advisedtostop.

CPRproviderfatigue

Severalmanikin studies have foundthat chest compression depthcandecrease assoonastwo minutesafterstarting chest compressions.243Anin-hospitalpatientstudyshowedthat,even

whileusingreal-time feedback,themeandepthofcompression deterioratedbetween1.5and3minafterstartingCPR.244Itis

there-forerecommendedthatCPRproviderschangeoverabouteverytwo minutestopreventadecreaseincompressionqualityduetoCPR providerfatigue.ChangingCPRprovidersshouldnotinterruptchest compressions.

Risksduringdefibrillation

ManystudiesofpublicaccessdefibrillationshowedthatAEDs canbeused safelyby laypeopleand firstresponders.185 A

sys-tematic review identified eight papers that reported a total of 29 adverse events associated with defibrillation.245 The causes

includedaccidentalorintentionaldefibrillatormisuse,device mal-functionandaccidentaldischargeduringtrainingormaintenance procedures. Four single-case reports described shocks to CPR providersfromdischargingimplantablecardioverterdefibrillators (ICDs),inonecaseresultinginaperipheralnerveinjury.No stud-ieswereidentified whichreportedharmtoCPRprovidersfrom attemptingdefibrillationinwetenvironments.

AlthoughinjurytotheCPRproviderfromadefibrillatorshock isextremelyrare,ithasbeenshownthatstandardsurgicalgloves donotprovideadequateprotection.246–249CPRproviders,

there-fore,shouldnotcontinuemanualchestcompressionsduringshock delivery,andvictimsshouldnotbetouchedduringICDdischarge. DirectcontactbetweentheCPRproviderandthevictimshouldbe avoidedwhendefibrillationisperformed.

Psychologicaleffects

One large, prospective trial of public access defibrillation reportedfewadversepsychologicaleffectsassociatedwithCPRor AEDusethat requiredintervention.242 Twolarge, retrospective,

questionnaire-basedstudiesfoundthatbystanderswhoperformed CPR regarded theirintervention as a positive experience.250,251

Family members witnessing a resuscitation attempt may also derivepsychologicalbenefit.252–254Therareoccurrencesofadverse

psychologicaleffectsinCPRprovidersafterperformingCPRshould berecognisedandmanagedappropriately.

Diseasetransmission

TheriskofdiseasetransmissionduringtrainingandactualCPR performanceisextremelylow.255–257WearingglovesduringCPR

isreasonable,butCPRshouldnotbedelayedorwithheldifgloves arenotavailable.

Barrierdevicesforusewithrescuebreaths

Threestudiesshowedthatbarrierdevicesdecrease transmis-sionofbacteriaduringrescuebreathingincontrolledlaboratory settings.258,259 No studies were identified which examinedthe

safety,effectivenessorfeasibilityofusingbarrierdevices(suchas afaceshieldorfacemask)topreventvictimcontactwhen per-formingCPR.Neverthelessifthevictimisknowntohaveaserious infection(e.g.HIV,tuberculosis,hepatitisBorSARS)abarrierdevice isrecommended.

Ifabarrierdeviceisused,careshouldbetakentoavoid unneces-saryinterruptionsinCPR.Manikinstudiesindicatethatthequality ofCPRissuperiorwhenapocketmaskisusedcomparedtoa bag-valvemaskorsimplefaceshield.260–262

Foreignbodyairwayobstruction(choking)

Foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO) is an uncommon but potentially treatable cause of accidental death.263 Asmost

chokingeventsareassociatedwitheating,theyarecommonly wit-nessed. Asvictims initiallyare consciousand responsive,there areoftenopportunitiesforearlyinterventionswhichcanbelife saving.

Recognition

Becauserecognitionofairwayobstructionisthekeyto success-fuloutcome,itisimportantnottoconfusethisemergencywith fainting,myocardialinfarction,seizureorotherconditionsthatmay causesuddenrespiratorydistress,cyanosisorlossofconsciousness. FBAOusuallyoccurswhilethevictimiseatingordrinking. Peo-pleatincreasedriskofFBAOincludethosewithreducedconscious levels,drugand/oralcoholintoxication,neurologicalimpairment withreducedswallowingandcoughreflexes(e.g.stroke, Parkin-son’sdisease),respiratorydisease,mentalimpairment,dementia, poordentitionandolderage.264

Fig.2.5 presentsthetreatmentalgorithm for theadult with FBAO. Foreign bodies may cause either mild or severe airway obstruction.Itisimportanttoasktheconsciousvictim“Areyou choking?”Thevictimthatisabletospeak,coughandbreathehas mildobstruction.Thevictimthatisunabletospeak,hasa weak-eningcough,isstrugglingorunabletobreathe,hassevereairway obstruction.

Treatmentformildairwayobstruction

Coughinggenerateshighandsustainedairwaypressuresand mayexpeltheforeignbody.Aggressivetreatmentwithbackblows, abdominalthrustsandchestcompressions,maycauseharmand canworsentheairwayobstruction.Thesetreatmentsshouldbe reservedforvictimswhohavesignsofsevereairwayobstruction. Victimswithmildairwayobstructionshouldremainunder contin-uousobservationuntiltheyimprove,assevereairwayobstruction maysubsequentlydevelop.

Treatmentforsevereairwayobstruction

Theclinicaldataonchokingarelargelyretrospectiveand anec-dotal. For conscious adults and children over one year of age

Fig.2.5.(Continued).

withcompleteFBAO,casereports havedemonstratedthe effec-tiveness of back blows or ‘slaps’, abdominal thrusts and chest thrusts.265 Approximately50%ofepisodesofairwayobstruction

arenotrelievedbyasingletechnique.266 Thelikelihoodof

suc-cessisincreasedwhencombinationsofbackblowsorslaps,and abdominalandchestthrustsareused.265

Treatmentofforeignbodyairwayobstructioninanunresponsive victim

Arandomisedtrialincadavers267 and twoprospective

stud-iesinanaesthetisedvolunteers268,269showedthathigherairway

pressurescan begenerated using chest thrusts compared with abdominalthrusts.Bystanderinitiationofchestcompressionfor unresponsiveorunconsciousvictimsofFBAOwasindependently associatedwithgoodneurologicaloutcome(oddsratio,10.57;95% CI,2.472–65.059,P<0.0001).270Chestcompressionsshould,

there-fore,bestartedpromptlyifthevictimbecomesunresponsiveor unconscious.After30compressionsattempt2rescuebreaths,and continueCPRuntilthevictimrecoversandstartstobreathe nor-mally.

Aftercareandreferralformedicalreview

FollowingsuccessfultreatmentofFBAO,foreignmaterialmay neverthelessremain in the upper or lower airways and cause complications later. Victims with a persistent cough, difficulty swallowingorthesensationofanobjectbeingstillstuckinthe throatshould,therefore,bereferredforamedicalopinion. Abdom-inalthrustsandchestcompressionscanpotentiallycauseserious internalinjuries and all victimssuccessfully treated withthese measuresshouldbeexaminedafterwardsforinjury.

Resuscitationofchildren(seealsoRecognitionofCardiac Arrestsection)andvictimsofdrowning(seealsoTheChain ofSurvivalsection)

Manychildrendonotreceiveresuscitationbecausepotential CPRprovidersfearcausingharmiftheyarenotspecificallytrained inresuscitationforchildren.Thisfearisunfounded:itisfarbetter tousetheadultBLSsequenceforresuscitationofachildthanto donothing.Foreaseofteachingandretention,laypeopleshould betaughtthattheadultsequencemayalsobeusedforchildren whoarenotresponsiveandnotbreathingnormally.Thefollowing minormodificationstotheadultsequencewillmakeitevenmore suitableforuseinchildren:

• Give5initialrescuebreathsbeforestartingchestcompressions. • GiveCPRfor1minbeforegoingforhelpintheunlikelyeventthe

CPRproviderisalone.

• Compressthechestbyatleastonethirdofitsdepth;use2fingers foraninfantunderoneyear;use1or2handsforachildover1 yearasneededtoachieveanadequatedepthofcompression.

Thesamemodificationsof5initialbreathsand1minofCPRby theloneCPRproviderbeforegettinghelp,mayimproveoutcome forvictimsofdrowning.Thismodificationshouldbetaughtonly tothosewhohaveaspecificdutyofcaretopotentialdrowning victims(e.g.lifeguards).

Collaborators

LeoL.Bossaert,UniversityofAntwerp,Antwerp,Belgium,

AntonioCaballero,EmergencyDepartment,HospitalUniversitario VirgendelRocío,Sevilla,Spain,

PascalCassan,GlobalFirstAidReferenceCentre,International Fed-erationofRedCrossandRedCrescent,Paris,France,

CristinaGranja,EmergencyandIntensiveCareDepartment, Hospi-taldeFaro,CentroHospitalardoAlgarve,Porto,Portugal,

Claudio Sandroni, Department of Anaesthesiologyand Intensive Care,CatholicUniversitySchoolofMedicine,Rome,Italy,

DavidA.Zideman,ImperialCollegeHealthcareNHSTrust,London, UK,

Jerry P. Nolan, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine,RoyalUnitedHospital,Bath,UK,

IanMaconochie, PaediatricEmergency Medicine and NIHR BRC, ImperialCollege,London,UK,

RobertGreif,Department ofAnaesthesiologyandPainMedicine, UniversityHospitalBernandUniversityBern,Bern,Switzerland.

Conflictsofinterest

GavinD.Perkins EditorResuscitation JasmeetSoar EditorResuscitation

AnthonyJ.Handley MedicaladvisorBA,Virgin,Placesfor people,LifesavingSocieties,Trading CompanySecretaryRCUK

GiuseppeRistagno ExpertadviceZOLL:ECGinterpretation MaaretCastren MedicaladvisoryBoardFalckFoundation RudolphW.Koster MedicaladvisorPhysioControland

HeartSine,ResearchgrantsPhysioControl, Philips,Zoll,CardiacScience,Defibtech, Jolife

VolkerWenzel Researchgrants,Medicaladvisor,Speakers honorarium“AOPOrphan”Pharma Jan-ThorstenGräsner Noconflictofinterestreported KoenraadG.Monsieurs Noconflictofinterestreported MichaelA.Smyth Noconflictofinterestreported TheresaMarieroOlasveengen Noconflictofinterestreported ViolettaRaffay Noconflictofinterestreported

linesforresuscitation2015section3adultadvancedlifesupport.Resuscitation 2015;95:99–146.

2.ZidemanDA, De Buck EDJ, Singletary EM, etal. EuropeanResuscitation Councilguidelinesforresuscitation2015section9firstaid.Resuscitation 2015;95:277–86.

3.PerkinsGD,TraversAH,ConsidineJ,etal.Part3:Adultbasiclifesupport andautomatedexternaldefibrillation:2015InternationalConsensuson Car-diopulmonaryResuscitationandEmergencyCardiovascularCareScienceWith TreatmentRecommendations.Resuscitation2015;95:e43–70.

4.BerdowskiJ,BergRA,TijssenJG,KosterRW.Globalincidencesof out-of-hospitalcardiacarrestandsurvivalrates:systematicreviewof67prospective studies.Resuscitation2010;81:1479–87.

5.GrasnerJT,HerlitzJ,KosterRW,Rosell-OrtizF,StamatakisL,BossaertL. Qual-itymanagementinresuscitation–towardsaEuropeancardiacarrestregistry (EuReCa).Resuscitation2011;82:989–94.

6.GrasnerJT,BossaertL.Epidemiologyandmanagementofcardiacarrest:what registriesarerevealing.BestPractResClinAnaesthesiol2013;27:293–306. 7.CobbLA,FahrenbruchCE,OlsufkaM,CopassMK.Changingincidenceof

out-of-hospitalventricularfibrillation,1980–2000.JAMA2002;288:3008–13. 8.ReaTD,PearceRM,RaghunathanTE,etal.Incidenceofout-of-hospitalcardiac

arrest.AmJCardiol2004;93:1455–60.

9.VaillancourtC,Verma A,TrickettJ, etal. Evaluatingthe effectivenessof dispatch-assistedcardiopulmonary resuscitationinstructions. Acad Emerg Med2007;14:877–83.

10.Agarwal DA, Hess EP, Atkinson EJ, White RD. Ventricular fibrilla-tion in Rochester, Minnesota: experience over 18 years. Resuscitation 2009;80:1253–8.

11.RinghM,HerlitzJ,HollenbergJ,RosenqvistM,SvenssonL.Outofhospital car-diacarrestoutsidehomeinSweden,changeincharacteristics,outcomeand availabilityforpublicaccessdefibrillation.ScandJTraumaResuscEmergMed 2009;17:18.

12.Hulleman M,Berdowski J, de Groot JR,et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillatorshavereducedtheincidenceofresuscitationforout-of-hospital cardiacarrestcausedbylethalarrhythmias.Circulation2012;126:815–21. 13.BlomMT,BeesemsSG,HommaPC,etal. Improvedsurvivalafter

out-of-hospitalcardiacarrestanduseofautomatedexternaldefibrillators.Circulation 2014;130:1868–75.

14.CumminsR,ThiesW.AutomatedexternaldefibrillatorsandtheAdvanced CardiacLifeSupportProgram:anewinitiativefromtheAmericanHeart Asso-ciation.AmJEmergMed1991;9:91–3.

15.WaalewijnRA,NijpelsMA,TijssenJG,KosterRW.Preventionofdeterioration ofventricularfibrillationbybasiclifesupportduringout-of-hospitalcardiac arrest.Resuscitation2002;54:31–6.

16.WeisfeldtML,SitlaniCM,OrnatoJP,etal.Survivalafterapplicationof auto-maticexternaldefibrillatorsbeforearrivaloftheemergencymedicalsystem: evaluationintheresuscitationoutcomesconsortiumpopulationof21million. JAmCollCardiol2010;55:1713–20.

17.BerdowskiJ,BlomMT,BardaiA,TanHL,TijssenJG,KosterRW.Impactofonsite ordispatchedautomatedexternaldefibrillatoruseonsurvivalafter out-of-hospitalcardiacarrest.Circulation2011;124:2225–32.

18.NolanJ,SoarJ,EikelandH.Thechainofsurvival.Resuscitation2006;71:270–1. 19.MullerD,AgrawalR,ArntzHR.Howsuddenissuddencardiacdeath?

Circula-tion2006;114:1146–50.

20.WaalewijnRA,TijssenJG,KosterRW.Bystanderinitiatedactionsin out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: results from the Amsterdam ResuscitationStudy(ARRESUST).Resuscitation2001;50:273–9.

21.SassonC,RogersMA,DahlJ,KellermannAL.Predictorsofsurvivalfrom out-of-hospitalcardiacarrest:asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis.CircCardiovasc QualOutcomes2010;3:63–81.

22.NehmeZ, AndrewE, Bernard S,Smith K.Comparisonof out-of-hospital cardiacarrestoccurringbeforeandafterparamedicarrival:epidemiology, sur-vivaltohospitaldischargeand12-monthfunctionalrecovery.Resuscitation 2015;89:50–7.

23.TakeiY,NishiT,KamikuraT,etal.Doearlyemergencycallsbeforepatient collapseimprovesurvivalafterout-of-hospitalcardiacarrests?Resuscitation 2015;88:20–7.

24.ValenzuelaTD,RoeDJ,CretinS,SpaiteDW,LarsenMP.Estimatingeffectiveness ofcardiacarrestinterventions:alogisticregressionsurvivalmodel.Circulation 1997;96:3308–13.

25.HolmbergM,HolmbergS,HerlitzJ,GardelovB.Survivalaftercardiacarrest outsidehospitalinSweden.SwedishCardiacArrestRegistry.Resuscitation 1998;36:29–36.

26.HolmbergM,HolmbergS,HerlitzJ.Factorsmodifyingtheeffectofbystander cardiopulmonaryresuscitationonsurvivalinout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest patientsinSweden.EurHeartJ2001;22:511–9.

27.WissenbergM,LippertFK,FolkeF,etal.Associationofnationalinitiativesto improvecardiacarrestmanagementwithratesofbystanderinterventionand patientsurvivalafterout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest.JAMA2013;310:1377–84. 28.Hasselqvist-AxI,RivaG,HerlitzJ,etal.Earlycardiopulmonaryresuscitationin

out-of-hospitalcardiacarrest.NEnglJMed2015;372:2307–15.

29.ReaTD,FahrenbruchC,CulleyL,etal.CPRwithchestcompresssionsaloneor withrescuebreathing.NEnglJMed2010;363:423–33.

diopulmonaryresuscitation:ameta-analysis.Lancet2010;376:1552–7. 32.ValenzuelaTD,RoeDJ,NicholG,ClarkLL,SpaiteDW,HardmanRG.Outcomes

ofrapiddefibrillationbysecurityofficersaftercardiacarrestincasinos.NEngl JMed2000;343:1206–9.

33.RinghM,RosenqvistM,HollenbergJ,etal.Mobile-phonedispatchoflaypersons forCPRinout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest.NEnglJMed2015;372:2316–25. 34.LarsenMP,EisenbergMS,CumminsRO,HallstromAP.Predictingsurvival

from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a graphic model. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:1652–8.

35.NolanJP,SoarJ,CariouA,etal.EuropeanResuscitationCouncilandEuropean SocietyofIntensiveCareMedicineGuidelinesforPost-resuscitationCare2015. Section5Post-resuscitationcare.Resuscitation2015;95:201–21.

36.vanAlemAP,VrenkenRH,deVosR,TijssenJG,KosterRW.Useof auto-matedexternaldefibrillatorbyfirstrespondersinoutofhospitalcardiacarrest: prospectivecontrolledtrial.BrMedJ2003;327:1312.

37.FothergillRT,WatsonLR,ChamberlainD,VirdiGK,MooreFP,WhitbreadM. Increasesinsurvivalfromout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest:afiveyearstudy. Resuscitation2013;84:1089–92.

38.PerkinsGD,LallR,QuinnT,etal.Mechanical versusmanualchest com-pressionforout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest(PARAMEDIC):apragmatic,cluster randomisedcontrolledtrial.Lancet2015;385:947–55.

39.WeisfeldtML,BeckerLB.Resuscitationaftercardiacarrest:a3-phase time-sensitivemodel.JAMA2002;288:3035–8.

40.ZijlstraJA,StieglisR,RiedijkF,SmeekesM,vanderWorpWE,KosterRW. LocallayrescuerswithAEDs,alertedbytextmessages,contributetoearly defibrillationinaDutchout-of-hospitalcardiacarrestdispatchsystem. Resus-citation2014;85:1444–9.

41.KerberRE,BeckerLB,BourlandJD,etal.Automaticexternaldefibrillatorsfor publicaccessdefibrillation:recommendationsforspecifyingandreporting arrhythmiaanalysisalgorithmperformance,incorporatingnewwaveforms, andenhancingsafety.AstatementforhealthprofessionalsfromtheAmerican HeartAssociationTaskForceonAutomaticExternalDefibrillation, Subcom-mitteeonAEDSafetyandEfficacy.Circulation1997;95:1677–82.

42.CallePA,MpotosN,CalleSP,MonsieursKG.Inaccuratetreatmentdecisionsof automatedexternaldefibrillatorsusedbyemergencymedicalservices person-nel:incidence,causeandimpactonoutcome.Resuscitation2015;88:68–74. 43.BahrJ,KlinglerH,PanzerW,RodeH,KettlerD.Skillsoflaypeopleinchecking

thecarotidpulse.Resuscitation1997;35:23–6.

44.NymanJ,SihvonenM.Cardiopulmonaryresuscitationskillsinnursesand nurs-ingstudents.Resuscitation2000;47:179–84.

45.TibballsJ,RussellP.Reliabilityofpulsepalpationbyhealthcarepersonnelto diagnosepaediatriccardiacarrest.Resuscitation2009;80:61–4.

46.TibballsJ,WeeranatnaC.Theinfluenceoftimeontheaccuracyofhealthcare personneltodiagnosepaediatriccardiacarrestbypulsepalpation. Resuscita-tion2010;81:671–5.

47.MouleP.Checkingthecarotidpulse:diagnosticaccuracyinstudentsofthe healthcareprofessions.Resuscitation2000;44:195–201.

48.BobrowBJ,Zuercher M,EwyGA, etal. Gaspingduringcardiacarrestin humans is frequent and associated with improved survival. Circulation 2008;118:2550–4.

49.PerkinsGD,StephensonB,HulmeJ,MonsieursKG.Birminghamassessmentof breathingstudy(BABS).Resuscitation2005;64:109–13.

50.PerkinsGD,WalkerG,ChristensenK,HulmeJ,MonsieursKG.Teaching recog-nitionofagonalbreathingimprovesaccuracyofdiagnosingcardiacarrest. Resuscitation2006;70:432–7.

51.BreckwoldtJ,SchloesserS,ArntzHR.Perceptionsofcollapseandassessmentof cardiacarrestbybystandersofout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest(OOHCA). Resus-citation2009;80:1108–13.

52.SteckerEC,ReinierK,Uy-EvanadoA,etal.Relationship betweenseizure episodeandsuddencardiacarrestinpatientswithepilepsy:a community-basedstudy.CircArrhythmElectrophysiol2013;6:912–6.

53.KuismaM,BoydJ,VayrynenT,RepoJ,Nousila-WiikM,HolmstromP. Emer-gencycallprocessingandsurvivalfromout-of-hospitalventricularfibrillation. Resuscitation2005;67:89–93.

54.BerdowskiJ,BeekhuisF,ZwindermanAH,TijssenJG,KosterRW.Importanceof thefirstlink:descriptionandrecognitionofanout-of-hospitalcardiacarrest inanemergencycall.Circulation2009;119:2096–102.

55.HewardA,DamianiM,Hartley-SharpeC.DoestheuseoftheAdvanced Med-icalPriorityDispatchSystemaffectcardiacarrestdetection?EmergMedJ 2004;21:115–8.

56.EisenbergMS,HallstromAP,CarterWB,CumminsRO,BergnerL,PierceJ. Emer-gencyCPRinstructionviatelephone.AmJPublicHealth1985;75:47–50. 57.StipulanteS,TubesR,ElFassiM,etal.ImplementationoftheALERTalgorithm,a

newdispatcher-assistedtelephonecardiopulmonaryresuscitationprotocol,in non-AdvancedMedicalPriorityDispatchSystem(AMPDS)EmergencyMedical Servicescentres.Resuscitation2014;85:177–81.

58.CastrenM, Kuisma M,Serlachius J, Skrifvars M.Do health care profes-sionals report sudden cardiac arrest better than laymen? Resuscitation 2001;51:265–8.

59.HallstromAP, Cobb LA,JohnsonE, CopassMK.Dispatcher assisted CPR: implementation and potential benefit. A 12-year study. Resuscitation 2003;57:123–9.