Building national identity through printed

landscape representations: Argentina

1910-1930

Catalina Fara

Abstract: This article focuses on visual imaginaries of printed Argentinean landscape representations

between 1910 and 1930. During this timeframe, landscapes circulated and operated culturally by juxtaposition and accumulation in different means (illustrated magazines, periodical press, calendars, postcards, albums, etc.), generating repertoires and discourses that crystallised in paradigmatic representations of the country’s diverse regions, many of which continue to be in force until the present. Images are analysed within a web of migrations in which objects, practises and discourses in transit are re-appropriated. This will allow us to interpret the elements of a visual vocabulary in landscape images that became fundamental for the building of a national identity imagery.

Keywords: Landscape, printed images, Argentina, imaginary of country, re-appropriation, circulation

Résumé : Cet article se concentre sur les imaginaires visuels de l’Argentine dans les représentations

imprimées des paysages entre 1910 et 1930. À cette époque, les paysages ont circulé par juxtapositions et accumulations sur différents supports (magazines illustrés, presse périodique, calendriers, cartes postales, albums, etc.). Ce fonctionnement culturel a généré des répertoires et des discours qui ont cristallisé sous forme de représentations paradigmatiques des diverses régions du pays, dont un grand nombre sont encore en vigueur aujourd’hui. Les images sont ici analysées dans un réseau de migrations où objets, pratiques et discours en transit sont réappropriés de façon à interpréter les éléments du vocabulaire visuel de paysages qui ont été fondamentaux dans la construction de l’imagerie d’une identité nationale.

During the 19th century, the construction of national identities was simultaneous to the development of a “public space”, which was a great force for ideological and social homogenization at national levels (Habermas 1978 [1962]). In Latin America, public debate was a fundamental instrument in the strengthening of the young republics after the independence revolutions that arose by the first decade of the century. The nation-building projects followed diverse notions of modernity and progress, but the need of unity was a common concern. This meant the rejection of the colonial social structures and led to the search of new identity principles found, among others, in civic republican values. The search of a landscape that could work as a symbol of the new national values was also a shared goal among these young nations.

Printed images played a central role in this process, by enhancing the circulation of new ideas and images. With the development of new technologies for image-making and printing, images multiplied and circulated in ways and proportions never experienced before, in what Roger Chartier (1989) described as “printed culture”. Exhibitions, photographs, publicity and other visual devices later broadened the visual culture. This massification and diversification of the means for production of visuals led to the emergence of “visual commonplaces” that became stereotypes or multiple variations of the same motifs that filled the pages of the illustrated magazines, but also appeared in postcards, calendars, posters, labels, etc. (Szir 2017, Vaillant 2009). National identities were then enacted in the circulation of stories, images and commemorations of a common past, often associated with a distinctive landscape. As Raymond Willliams (1973) defined them, these “visual commonplaces” are the field of material and symbolic action of hegemony, where the historic and material trace of hegemonic operation is erased, leading to perceive the landscape as something that has always been and will always be there. Thus, landscape images are useful to think about the tensions between material progress and cultural identity. John Agnew (2011: 39) has called the attention to the images that people might carry around and defined them as “landscape ideals”, which are not necessarily the same as those built by those in power. We can then understand these representations as social constructions determined by multiple factors that are distinguishable in the printed images.

How to decipher landscape images that represent Argentina? Which elements or characteristics can help us map them? This article focuses on visual imaginaries of the Argentinean landscape representations between 1910 and 1930. The role that natural environment occupies in definitions of national identity (especially in the 19thcentury) has long been studied by scholars from different fields, from geography to art history. It has also been long discussed how landscapes are valued in different historical and political contexts (see Giordano 2009, Ahumada 2012, Malosetti Costa 2012). However, very few studies have focused on the printed landscape images from Argentina, especially those at the onset of the 20th century. In this article I will highlight and contextualize some key problems in the analysis of the Argentinean case, to be further examined in future investigations:

1. Landscape as symbol of national identity: between rural and urban, between the mountains and the pampa, from north to south.

1a. Conventions and paradigmatic views of certain places: the building of a “commonplace” 2. Conditions of production, circulation and appropriation of printed images

2a. Dialogues between art and printed images: relationships and mutual influences. The role of institutions such as museums and national art contests in the conformation of an “official image” or a “state landscape iconography”.

1. The nation as a landscape

Landscape is a “way of seeing” through which humans represent themselves and the world around them. It is a perception of the environment that relates to history and other cultural practices, using techniques and expressive mechanisms from a specific place and period (Cosgrove 1998). Hence, more than a simple pictorial genre, landscape can be considered as a vast web of symbols that express the social relationships of a culture. The experience of landscape is inscribed within the wider experience of space, by which the subject shapes its place in the world. This frame is therefore determined by philosophical, aesthetic and political ideas. With these premises, Alain Roger (1997) introduced the concept of artialisation, defining landscape as the union between visual perception and culture. This union comes from a double movement: the awareness of the environment and the interpretation of its characteristics through art.

It is possible to distinguish between “landscape-image” (artistic or technical representation) and “landscape conscience” (the real landscape seen and experienced “here and now”). But representation often precedes the perception of an environment, and is in this sense that which Ernst Gombrich (2008 [1960]) distinguished between the “real” landscape and the one “permeated” by art. Landscape therefore “is not merely the world we see, it is a way of construction, a composition of that world. Landscape is a way of seeing the world” (Cosgrove 1998: 13). Furthermore, landscapes, as any image, are not neutral and can be subjected to multiple manipulations, either ideological or concerning power and control. In this regard, they are areas of interchange that are constantly being re-formulated. They show the ways in which power, place, and cultural traditions intersect and come into conflict in visual culture.

As a universal concept, modernity is then a key term in the analysis of intercultural processes within the visual culture, bearing in mind the historical and social contexts in which it developed. Accordingly, landscape representations will be conceived as complex webs to understand their relationship with the modernization process of a country, defining the means, resources, strategies and practices in the conformation of cultural memories. These images become an intersection between the political and the aesthetical practices of modernity (Andermann 2008: 5); so, it is necessary to understand them working as “cultural practices”, that is, as ways of power that have an intentionality behind them (Mitchell 1994). The hypothesis that guides this article lies in understanding modernity as the tension between space, time and frontiers (both material and conceptual). Therefore, Argentinian landscape images are to be interpreted within a web of “migrations” in which objects, practices and discourses in transit are appropriated and re-signified (Wechsler 2014). This will allow us to unfold the elements of a visual vocabulary that became fundamental to the construction of national identity.

Images of nature have the capacity of becoming portraits of progress as they can be powerful symbols in showcasing the economic success and potential of a country. Therefore, they turned into useful tools in the construction of national identities, especially during the 19th century (Debarbieux 2011: 144). To this matter, some authors acknowledge that the symbolic analogies between landscape and nation can take two forms (Kauffmann and Zimmer 1998). The first form is understood as the “nationalization of nature” that projects historical myths, memories and national virtues onto a specific landscape, which then reflects the nation’s singularity. The other form can be described as “naturalization of the nation”, that rests upon geographical determinism. Natural environment and specific landscapes are then perceived as moral and spiritual sources, capable of shaping the nation and giving it a unified form (Kauffmann and Zimmer 1998: 486). Consequently, by this conception a nation’s characteristics are not shaped by social aspects but by physical or geographical ones.

A nation can be defined as “a cultural order composed of certain values, symbols and ethno-historical myths. It is this cultural order, the nation, that lends meaning and legitimation to the political order that is commonly referred to as the ‘state’, which is rooted in a set of legal, political and economic institutions” (Kauffmann and Zimmer 1998: 485). In addition, the nation as a concept is not only a matter of political theory but a matter of aesthetics as are habits, traditions, and artistic forms that have historically expressed a nation, and which have shaped it into the collective imaginary. It is there where the processes of national invention take place, and these narratives then establish a link between land and nation (Perez Vejo 1999: 18). Landscape has always been associated with the image of a country, mostly related to an “identifiable archetype” that synthesizes aspects of the geography and its associated traditions, working almost as a trademark. Its characteristics though, are not univocal and have much to do with the presence of certain categories that operate as models, and that can come from different fields of production such as art or literature. In this sense, art shapes the image of a country in its aesthetic apprehension of the territory, transforming it in motifs that are then replicated and reproduced by different means.

As previously mentioned, printed images enjoyed dynamic worldwide circulation in the 19th century and had a definite impact in the building of modern nations’ imaginaries. Each image represented a kind of “domestication” of the territory, so they became new ways for interpreting and thinking the country itself. In Latin America, the necessity of a national landscape as a source of social orientation and collective identification appeared after the independence revolutions, when it was essential to outline new national identities (Perez Vejo 1999, Colom Gonzalez 2003). Landscape representations then circulated and operated culturally, not only individually but by juxtaposition and accumulation through different means (illustrated magazines, periodical press, almanacs, posters, picture postcards, albums, etc.), generating repertoires and discourses that crystallized in paradigmatic images, many of which prevail nowadays. As Benedict Anderson (1983) stated, it was the printed images and texts that allowed for the constitution of the “imagined community”. Nations are shaped by ideas shared by the members of social groups, so the importance of landscape images in the building of national identities reinforces Anderson’s claim about print as fundamental in spreading the idea of the nation.

2. Defining an Argentinian landscape image in the land of all climates

The building of a unified Argentinian national identity became a necessity in the last decades of the 19th century, because of immigration influence and the impact of the economic policies imposed by the elite in power (Devoto 2002). The problem was to unify the socio-cultural heterogeneity of a country where ethnic and geographical diversity led to a polarization in the ways of thinking the nation.

Argentina is a large country, with a total area of 2,780,400 square meters (1,073,500 square miles) that holds a wide variety of ecosystems and climates, from subtropical in the north to polar in the south; from the Andes in the west to the 4,989 kilometers (3,100 miles) of Atlantic coast in the east. This generates a difficulty in “choosing” only one national landscape as an image capable of portraying the diversity of its regions. So, the national landscape imaginary became a collection of representations that symbolized the relationship between people and their land in differentiated areas, all considered as equal repositories of identity values, summing up the idea of the country having “all climates”. But, as different researchers have demonstrated, rural areas have often been idealized as symbols of national identities (Agnew 2011: 37). In

the Argentinian case, literature, arts and politics have exerted considerable influence in delineating the rural area of the pampa plains as the quintessential national landscape. Particular characteristics were erased or highlighted to favor a symbiotic image of the countryside and its inhabitants. Rural life was consequently valued as the refuge of local identity and good habits, also considered as the “essence of the nation”. Hence, these images worked as more than plain topographical references, but as sources of a sort of “sociological” information (fig.1).

Fig. 1. Prilidiano Pueyrredón. El rodeo (The rodeo), oil on canvas, 1861. MNBA, Buenos Aires.

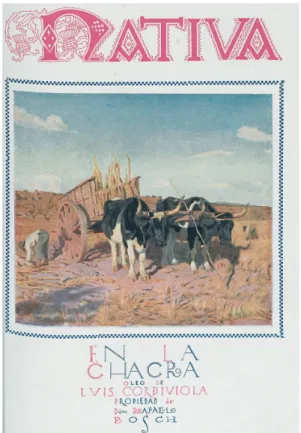

Fig. 2. Nativa, front cover, n°151, 1925. Reproduction of La chacra (The ranch) by Luis Cordiviola.

From literature to painting the same motifs and perspectives of certain places were repeated to strengthen this idea of nationality rooted in rural tradition. This shaped an ideological and aesthetic tendency called nativismo, closely related to folklore, showing characters and places as timeless expressions of Argentinian nationality (Fasce 2013) (fig.2). Related to the 19th century pictorial practices of costumbrismo, this movement defined itself as an objective form of visual description that introduced recognizable images of

subjects and landscapes. This tradition followed international formats and conventions that affected the visual arts in Latin America and were imposed on local matters (Majluf 2006).

The 19th century conceived the civilized landscape in aesthetic terms, which meant that its representations should provide conscious intellectual pleasure. But also, they had to be a suitable symbol for a young and modern nation. In this sense, literary canon gave the pampa a key role in the shaping of national landscape. When the territory was unified after 1850, the countryside was interpreted as a “desert” as it was mostly occupied by natives; and as a result, these lands had to be conquered in the name of “civilization and progress”. With this objective, the Campaña del Desierto (Campaign of Desert) that ended in 1885 determined the eradication of the native communities and the transformation of extensive areas of the pampa and Patagonia into large estates owned by the elite. The pampa then became a powerful image in terms of economical exploitation, as it was the source of the agricultural richness of the country (Malosetti Costa and Penhos 1991, Tell 2017: 21-64). Therefore, by 1910 this land was transformed into a landscape of power, although the flat geography was a problem for visual arts, which often continued to consider it as a “vacant” landscape.

By the 1920’s the pampa was described as a sublime desert, as a fertile plain in a Virgilian sense, appreciated as the place in which the past of the country was built, and where its future laid. The countryside was considered the center of the nation, as Argentinian writer Ricardo Rojas pointed out in 1924: “Whether it is the territory which shapes culture, or is it culture a spiritual entity that finds its symbols in the territory, I think that the geographical component in Argentine literature is, for us, the de la Plata river as the vital circulatory system; and the pampa that gives its aspect to the national land, which is surrounded by the rainforests and mountains” (Rojas 1980 [1924]: 57)1.

At the beginning of the 20th century, certain areas acquired a more important role in the national landscape repertoire. The intersections and the overlap of textual and visual narratives spread the multiple discourses that incorporated new geographies to the imaginary. In this context, the mechanisms through which the consensus on which areas better represented the “essence” of the country have a lot to do with the development of tourism. The gaze of travellers, writers and artists granted aesthetic value to the landscapes and contributed to give them a cultural meaning. Both the use of photography and landscape painting responded to the need of portraying and displaying the beauty of the places and helped building a shared idea of the national territory. But fundamentally it was the opposition between nationalism and cosmopolitism that was held as the ground for a differentiated local culture. Cosmopolitism was understood as the result of influences coming from abroad, rather than arising from an innate necessity or a deeper elemental force found only locally as the sources of a true “national art”. Given this debate, contrasted images of the same area coexisted, whose success or failure depended on the sociopolitical context. Either way, countryside images participated in delineating the national identity symbolized and condensed into a single landscape.

Nevertheless, landscape was a very useful tool to symbolize the ideas and values held by both sides of the discussion. While cosmopolitans idealized the urban scene of Buenos Aires, nationalists advocated rural landscape as Argentina’s key image. For the latter, the chaotic perceptions of the modern city coalesced with the “internationalist” ideas associated with immigrants, and were consequently understood as dangerous. There were groups among nationalists who perceived foreign cultures as a threat to local traditions, and

those who understood Argentinian identity as a fusion between the locals (gauchos, natives and criollos) and the immigrants (Sarlo 2007 [1988]). This last perspective was proclaimed by Ricardo Rojas in his book Eurindia in 1924, where he reflected on the idea of a “correlation of symbols” that meant the elevation of all cultures through art. It was art’s mission to symbolize the national identity by being the reflection of its traditions and unity (García and Penhos 2015, Bovisio 2015). The aesthetic associated with these ideas searched for the “uncovering of the land’s secrets”, to recover a “spiritual life” in Rojas terms.

In 1910 the Centennial International Exhibition was held in Buenos Aires to commemorate the centennial of the May Revolution (the proclamation of the first local government, leading to the independence from Spain in 1816). The selection of vernacular artists for the Exhibition’s art section reflected the concern about the existence of a “national art”. Some intellectuals and artists like Eduardo Schiaffino2 believed that the

“Argentinian school” was a reality; on the contrary, others like Martín Malharro3 argued about the impossibility of such thing in a context where only a few “real local” artists actually existed (Muñoz 1995). This last idea was also held by those who considered that cosmopolitism was a negative influence for the development of a national artistic language, especially in the context of a city like Buenos Aires. The city’s constant change and modernization was not the ideal environment to find an enduring national identity. Therefore, the contrast between the country and the city – a position traceable to Antiquity (Williams 2011 [1973]) – sustained the interpretation of the pampa as the essence for the national landscape. This aspect was reinforced in 1911, when the Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Salon) opened for the first time. Its statute encouraged artists to depict landscapes and portraits in works “of national character, made by Argentines” (Comisión Nacional de Bellas Artes 1913: 4)4. By these rules, the Salón Nacional

established the standard for the legitimated canon of national art.

The paintings presented at the salon can be divided in three groups, according to their theme: figure (portraits, groups, nudes, etc.), still life and landscape, each with its own diversity. A significant 40% of the works presented correspond to landscapes5. The analysis of the works presented in a contest like the Salón Nacional lets us evaluate the extent of the artists’ participation in the building of an “official” national landscape image. By “official” we mean those motifs accepted at the Salón, exhibited in public museum collections, reproduced in institutional publications and accepted in other national or provincial contests. Following the material approach of Raymond Williams (1980), we can understand culture as a mediation through which a meaning is modified in its production and consumption. Experience and contact with the image then become fundamental, as well as the web of relations of the producer and its specific intentions and conditionings. The Salón presented a selection of the aesthetic and iconographic repertoire that shaped the discourse on national art, whose models were formed by a standard that then turned them into agreeable images for the bourgeois taste (fig.3). The standard was to turn the landscape into timeless images in which the viewer would be able to recognize himself and his country (Penhos and Wechsler 1999). This explains the permanence of certain motifs, especially from the countryside and the Cordoba province’s mountains. Artists like Cesareo Bernaldo de Quirós, Jorge Bermúdez or Carlos Ripamonte were the most renowned and

2 Eduardo Schiaffino (1858-1935). Argentine painter, art critic and art historian. Founder of the National Museum of Fine Arts in

Buenos Aires in 1895, and Director until 1910. In 1891 he was among the founders of the Athenaeum, a group of intellectuals dedicated to renovating the Latin American culture. He acted as a diplomat in Europe. In 1933 he published his most important book Painting and Sculpture in Argentina.

3 Martín Malharro (1865-1911) Argentine painter and lithographer, studied with Francisco Romero, Ángel Della Valle and

Reinaldo Giudici. He then studied in Paris and returned to the country in 1901. He dedicated most of his work to the pampa landscape influenced by the Symbolism. He was Dean of the School of Art of La Plata National University and he was dedicated to developing an art education theory for primary schools.

4 The translation is mine. The requirements for the Salón Nacional, were first published in the cited 1913 exhibition catalogue. 5 This percentage was calculated from a total of 5,334 paintings exhibited at the Salón between 1911 and 1936.

appreciated by critics who demanded a national art that focused on local landscapes and characters6. It was Fernando Fader7 who best suited this paradigm, as most of his works portrayed the landscape of the Cordoba province with an eclectic use of impressionistic language (fig.4). His art appeared as the most suitable version of what was expected from a “national artist” and earned the favor of public and private collectors (Wechsler 1991: 348, Baldasarre 2016). Fader won the Grand Prize at the Salón Nacional in 1914, placing his painting as the model for younger generations. At this point, Cordoba’s mountains were added to the pampa as the landscapes that symbolized Argentinian identity.

In this context, the artist and art critic José María Lozano Mouján (1922) acknowledged that, as cosmopolitism obstructed the possibility of a national art, the solution was to develop and value the regional identities. As these ideas generalized, they lead to the “rescue” of other national landscapes, particularly those representing the north of the country (fig.5).

Fig. 3. Catálogo del XI Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes (XI National Fine Arts Salon Catalogue), Buenos Aires, 1921. Double page 20-21, works by Ceferino Carnacini (left) and Walter de Navazio (right).

6 Images of these artists’ work available at https://www.bellasartes.gob.ar/coleccion/arte-argentino

7 Fernando Fader (1882 –1935). Argentinian painter, studied in the Munich Academy of Arts mentored by Heinrich von Zügel. He

exhibited his paintings for the first time in Buenos Aires 1906, with a great success that followed him all his career. He settled in Cordoba province where he dedicated his painting to its landscapes, engaging in the plein air technique.

Fig. 4. Plus Ultra, front cover, n°155, 1929. Reproduction of Paisaje de Córdoba (Córdoba´s

landscape) by Fernando Fader.

Fig. 5. Fray Mocho, front cover, n°21, 1924. Reproduction of Una calle de Jujuy (Jujuy street)

by Leonie Matthis.

3. Printed landscapes for a modern nation

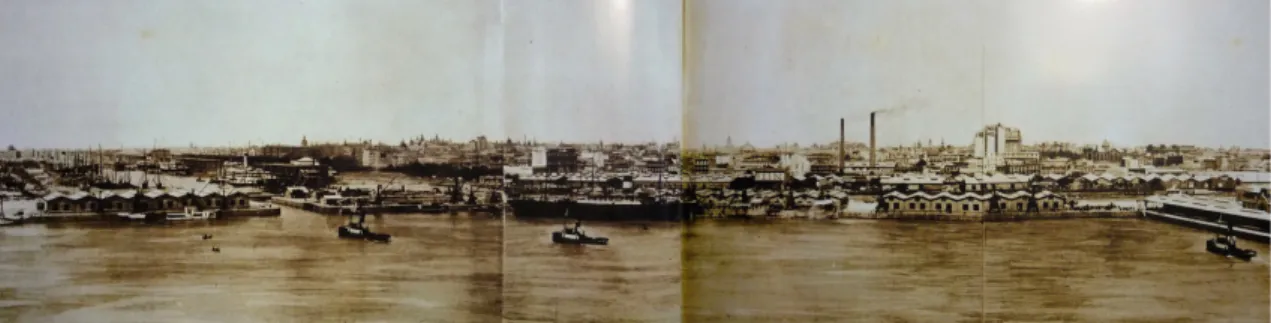

For the Centennial of the May Revolution in 1910 (the Centenario), the country sought to build its image as a civilized young nation with Buenos Aires as a South American cosmopolitan metropolis. The visual and discursive images in circulation helped the people to know and to recognize themselves in order to define an identity that was to be projected on the national and international scene. The representations of the Buenos Aires’ urban scene in particular, played an outstanding role in building the image of a modern nation, by highlighting the new architectures and material changes in the layout of the city, celebrating the grandeur of the nation’s capital (fig.6). Landscapes therefore became a symbol of the nation’s progress both by showing the richness of its natural resources and the modernity of its cities.

Fig. 6. Gastón Bourquín, “Vista parcial – Buenos Aires” (“Partial view- Buenos Aires”), Album Buenos Aires, Gastón Bourquín y cia. Editor, c.1930.

Photo albums were the most common way of portraying these achievements and the most effective to display state programs, and were also a very popular publicity stunt for private companies. The Centenario was the perfect occasion for the multiplication of these albums in which, landscape images played a central role. They summarized the propaganda effort in configuring and reinforcing a national imaginary that highlighted the natural beauty as fundamental to demonstrate the wealth of the country.

Publications like the Álbum La República Argentina en su primer Centenario aimed to promote a modern image of the nation by presenting its political organization, its economical productivity and the traditions of its people connected to the landscapist-geographical unity of the territory. This particular album contributed to spread the government’s image of progress by showing its ability to control nature’s elements in order to build a civilized country and a civilized landscape (fig.7). This aspect is clear in images that include railways, bridges, roads, dams, ports, crops, etc., as a way of opposing “civilized” and “barbaric”, and reinforcing the bourgeois order of the domesticated nature.

Fig. 7. “Buenos Aires. Partial northern view of the port”, La República Argentina en su Primer Centenario, 1810-1910. Buenos Aires: BNA/Fototeca “Benito Panuzzi”: 2010 [1910] (facsimile edition).

This discourse permeated to other images of mass consumption such as postcards or illustrated magazines. This multiplication of landscape images from certain areas of the country settled visual commonplaces of composition schemes and motifs (fig.8). Landscape then became the favorite genre for artists to transmit values and ideas, as it was very straightforward in terms of effectiveness8.

8 Although avant-garde artists did not oppose to landscapes as a motif in their paintings, the discussion about a national landscape

Fig. 8. Left: Revista del Ferrocarril del Sud, (magazine from the Argentina South Railway Company), front cover, n°106, 1934. Reproduction of Nahuel Huapi by Aurelio Cincioni. Right: “The beauty of Nahuel Huapi”, Argentina South Railway Company

brochure, 1930.

Printed press collaborated in the development of consumerism and in the construction and circulation of the new ways of living and socializing. In the 1920’s new products and new needs led to mass production and consumption, represented by the many brands advertised in the media. It was precisely advertising which enabled the mass printing and distribution of weekly magazines like Caras y Caretas (published between 1898 and 1939) at an affordable price for general public consumption. Landscape images were also part of this phenomenon, as photographs proliferated in publications like El Hogar, Fray Mocho, Aconcagua and Plus Ultra and in national newspapers like La Nación or La Prensa; that incorporated new geographies – local and international – into the national imaginary. Between 1910 and 1930 a remarkable amount of these images appeared gradually, vindicating the power of mass media in favoring the development and expansion of visual culture, but most importantly, shaping an image of the national landscape. To this matter, it is necessary to mention that many artists used photographs published in illustrated press or postcards as inspiration for their work (Fara 2020). This practice was not new, as it has been long demonstrated how, for example, the Impressionists used photography to construct their paintings. Illustrated magazines hosted collections and displayed images produced in the country and those re-appropriated from across the world. The intersections and the overlap of textual and visual narratives in printed means in their heterogeneity, showed the multiple discourses taking part in the construction of the national landscape.

As mentioned before, divergent positions surfaced in all areas of politics and culture: on the one hand, a nationalist tendency that pretended to rescue the colonial heritage rooted in the countryside; on the other, a more cosmopolitan vision – materialized in the avant-garde movements of the 1920’s – that celebrated the metropolis as a symbol of modernity (Fara 2020). During this period, the printed press echoed these matters and several magazines reflected the preoccupation of intellectuals and artists. A clear example is Nativa magazine, published between 1924 and 1964 (Hrycyk 2011), that was directly related to nationalist ideas

and the aesthetics of nativismo. In its pages, a collection of images and texts showed the “distinctive corners of the national identity”, as was claimed by its editors (Fasce 2013). The covers always included a photograph or a reproduction of a painting by a local artist (fig.9). The most frequent motifs were rural scenes from the north of the country, the pampa and Cordoba’s mountains, that also were the most reproduced places in its pages and therefore considered as the image of the nation.

Fig. 9. Left: Nativa, front cover, n°25, 1926. Right: Nativa, front cover, n°91, 1924.

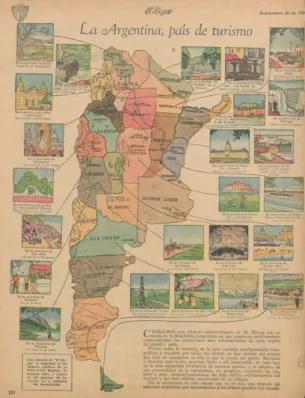

Picture postcards also played an important role in the expansion of visual culture and in the construction of national landscape imaginaries (see Onken 2014). Moreover, as Verena Winiwarter (2008: 206-207) indicates, “postcards are one of the barely noticed signs used for the daily inculcation of nationhood, part and parcel of the visual semantics of nationalism”. The most important editorial houses in the period 1910-1930 were Peuser, Rosauer, Adolfo Kapelusz, Fumagalli and Weiss, among others, that were publishing postcards in great numbers since the end of the 19thcentury (Farkas 2016). The most reproduced were the views from Buenos Aires (particularly the city center streets, the port and La Boca neighborhood), the Iguazú Falls, the Andean areas (particularly Nahuel Huapi lake and Bariloche) and Cordoba’s province rivers and mountains (fig.10). These places were the most visited in terms of local and international tourism and were always portrayed in a straightforward and inviting way. But their images were also very useful in the construction of a national identity based on cultural and natural diversity, as “domestic tourism offers the possibility to reinforce the case for nationalism, enhancing the travelers’ self-image with a pictorial inventory of nationalist tropes” (Winiwarter 2008: 207-211) (fig.11).

Fig. 10. Picture postcards. Up: San Juan province’s crops (c.1920). Down: Mar del Plata (c.1912)

Fig. 11. “La Argentina país de turismo” (“Argentina tourism country”), El hogar, n°1302, 1934.

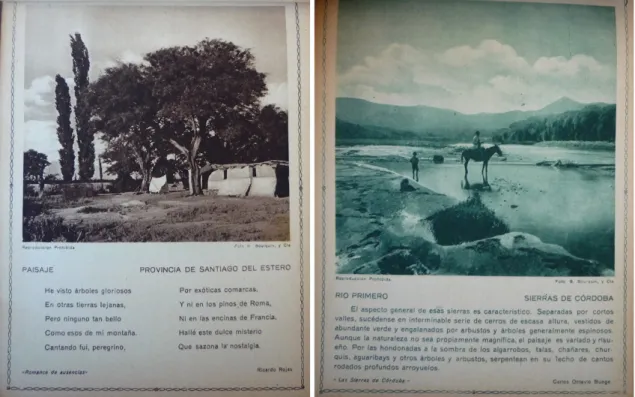

One of the most prolific postcard editors was the Swiss-born photographer Gastón Bourquin (Tell 1999). He also published high circulation almanacs that reproduced landscapes or urban views. For example, La Argentina pintoresca (The Picturesque Argentina) published in 1921, incorporated images from all the corners of the country from north to south, accompanied with literary extracts and poems (fig.12). The development of new printing techniques not only reduced the prices but also contributed to increase consumer numbers. Postcards and almanacs could be purchased in the newspaper stands as well as in bookstores. Postcards were also often published in series and collected in albums. As Graciela Silvestri (2011: 212-217) pointed out, the colors, the formats, the chosen views and composition widened the imaginary, and became actual picture galleries that, in the case of the landscape images, generated a sort of “fictional travel”. At the same time, in their extended circulation and uses, postcards and almanacs canonized patterns and motifs of national landscape.

Fig. 12. Almanac pages. Picturesque Argentina. Gastón Bourquin editor and photographer, c.1925.

4. Final considerations

The anesthetization of nature, characteristic of the civilizing process imposed by modernity, transformed landscapes into the main expression of Latin-American identities as an alternative to the exotism imposed by the European gaze. This was part of a “narrative of progress”, in which landscape was a piece in the conformation of a national identity narrative, rooted in the analogy between nation-territory, territory-landscape in a continuous bond (Szir 2017). This analogy was effective for the administrative and symbolic operations that built the state.

The images of a country are built upon visual schemes that are implicitly projected over the places represented. Aesthetic visions, history, traditions, political ideologies and specific circumstances determine diverse landscape representations. Hence, these images became new ways for understanding and thinking the country itself, working both as metaphor and metonymy of the territory in which that nation is established. The historical singularities of its construction determine its distinctive characteristics and, help understand the changes and continuities through time. In the Argentinian case the construction of hegemonic identities, shaping a “commonplace” for the national landscape was summed up in the idea that the country is the land of all climates.As a result, each region developed a hegemonic image that became part of its symbolic local identity. Some of those images – the pampa, Cordoba’s mountains or the urban landscape of Buenos Aires – enjoyed a more durable sort. Nevertheless, the process of constructing an autochthonous image of each region was defined by specific means, resources, strategies and practices. The conformation of cultural memories was thus determined by means of development, circulation and reception of a corpus of representative images.

Art shapes the image of a country, in its aesthetic apprehension of the territory, transforming it in motifs that are then replicated by photography and reproduced by different means, from printed press to postcards. Landscape can be considered then as merchandise, ready to be consumed, but also as a powerful image in

terms of portraying the economic success and potential of a country. It is important, however, to bear in mind which aesthetic principles are in fashion, or better, which are the ones that the State considers appropriate to transmit its messages. In Argentina, the appreciation of certain aspects of the country and its traditions, led to consider nature as the origin of national identity. Nature and culture were then articulated from a bourgeois perspective that shaped discourses identifying certain areas of the country as emblematic. In Argentina, the imaginary of national landscapes became a collection of images that symbolized the relationship of the inhabitants with their land in differentiated areas, but all considered as equal repositories of national identity and values.

Bibliography

AGNEW, J. (2011) “Landscape and national identity in Europe: England versus Italy in the role of landscape in

identity formation”. In: Landscapes, identities and development. Roca, Z;Claval, P.; Agnew, J. (eds.), New York:

Routledge: 37-50.

AHUMADA, P. (2012) “Paisaje y nación: la majestuosa montaña en el imaginario del siglo XIX”. In Artelogie, 4: 1-22. http://cral.in2p3.fr/artelogie/spip.php?article144 (accessed, April 8, 2013).

ANDERSON, B. (1983) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

ANDERMANN, J. (2008) “Paisaje: imagen, entorno, ensamble”. In Orbis Tertius (13) 14. UNLP: 1-7. http://www.orbistertius.unlp.edu.ar/ (accessed, April 3, 2017).

BALDASARRE, M.I. (2016) “Con la paleta, el pincel y el caballete. Los artistas en las “Caricaturas contemporáneas”

de Caras y Caretas”. In: Huellas. Búsquedas en Artes y Diseño (9): 81-96.

BOVISIO, M.A. (2015) “The pre-Hispanic tradition in Ricardo Rojas’ Americanist proposal: an analysis of El

Silabario de la Decoración americana (The Syllabary of American Decoration). In: 19&20, (X) 1.

http://www.dezenovevinte.net/uah1/mab_en.htm (accessed, March 26, 2016).

CHARTIER,R. (dir.) (1989) The culture of print. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

COLOMGONZALEZ, F. (2003) “La imaginación nacional en América Latina”. In Historia Mexicana, LIII, 2:

313-339.

COMISIÓNNACIONALDEBELLASARTES(1913)Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes: Buenos Aires.

COSGROVE, D. (1998) Social formation and symbolic landscape. Madison: Wisconsin University Press.

DEBARBIEUX,B. (2011) “Imaginarios de la naturaleza”. In Geografías de lo imaginario. Herniaux, D. and Landon,

A. (eds.), Mexico: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana: 136-154.

DEVOTO, F. (2002) Nacionalismo, fascismo y tradicionalismo en la Argentina moderna. Una historia. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

FARA,C.(2020) Un horizonte vertical Paisaje urbano de Buenos Aires 1910-1936. Buenos Aires: Ampersand.

FARKAS, M. (2016) “Mirar con otros ojos. Cultura postal, cultura visual en las tarjetas postales con vistas fotográficas del Correo Argentino (1897)”. In Ilustrar e imprimir. Una historia de la cultura gráfica en Buenos Aires,

1830-1930. Szir, S. (coord.), Buenos Aires: Ampersand: 146-177.

FASCE,P. (2013) “Identidad impresa. La estética del nativismo y las revistas ilustradas en Argentina, 1930-1940”. In:

Actas de las I Jornadas de jóvenes investigadores en ciencias sociales. Buenos Aires: IDAES-UNSAM.

GARCÍA,C. and PENHOS, M. (2015) “‘Mestizo’… ¿Hasta dónde y desde cuándo? Los sentidos del término y su uso

en la historia del arte”. In: VIII Encuentro internacional sobre Barroco. Arequipa: Visión Cultural: 315-324.

GIORDANO, M. (2009) “Nación e identidad en los imaginarios visuales de la Argentina. Siglos XIX y XX”. In

Arbor, 740: 1283-1298. doi: 10.3989/arbor.2009.740n1091 (accessed, June 20, 2016).

GOMBRICH, E. (2008 [1960]) Arte e ilusión. Estudio sobre la psicología de la representación pictórica. London, Phaidon.

HABERMAS. J. (1978) L’espace public. Paris: Payot.

HRYCYK,P. (2011) “Nacionalismo telúrico y discurso plástico. La Revista Nativa y su propuesta estético-política en

la Argentina de los albores de los 30”. In: Revista Eletrônica da ANPHLAC, 11: 76-104. http://revista.anphlac.org.br/index.php/revista (accessed: June 12, 2017).

KAUFMAN,E. and ZIMMER, O. (1998) “In search of the authentic nation: landscape and national identity in Canada

and Switzerland”. In Nations and nationalism, 4: 483-510. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1998.00483.x (accessed, June 24, 2017).

LOZANO MOUJÁN, J. (1922) Apuntes para la historia de nuestra pintura y escultura. Buenos Aires: A. García

MALOSETTICOSTA, L. (2012) “Telescoping the past from the endless plains”, 3rd International Research Forum for Graduate Students and Emerging Scholars, The University of Texas at Austin – Austin, October 25-27 (Unpublished conference paper).

MALOSETTI COSTA, L. and PENHOS, M. (1991) “Imágenes para el desierto argentino. Apuntes para una

iconografía de la pampa”. In: Ciudad/Campo en las Artes en Argentina y Latinoamérica. III Jornadas de Teoría e

Historia de las Artes. Buenos Aires: CAIA.

MAJLUF,N. (2006)“Pattern book of Nations: Images of types and costumes in Asia and Latin America,

ca.1800-1860”. In: Reproducing nations: types and costumes in Asia and Latin America, ca. 1800-1860. New York: Americas Society: 15-56.

MITCHELL, W.J.T. (ed.) (1994) Landscape and power. Chicago-London: The University of Chicago Press.

MUÑOZ, M. A. (1995) “El arte nacional: un modelo para armar”. In: El arte entre lo público y lo privado. VI

Jornadas de Teoría e Historia de las Artes. Buenos Aires, CAIA.

ONKEN, H. (2014) “Visiones y visualizaciones: La nación en tarjetas postales sudamericanas a fines del siglo XIX y comienzos del siglo XX.” In: Iberoamericana (14) 56: 47–69.

PENHOS, M and WECHSLER,D. (coords.) (1999) Tras los pasos de la norma. Salones Nacionales de Bellas Artes

(1911-1989). Buenos Aires: CAIA/Ed. del Jilguero.

PEREZVEJO, T. (1999) Nación, identidad nacional y otros mitos nacionalistas. Oviedo: Nobel.

ROGER,A.(1997)Court traité du paysage. Paris: Gallimard.

ROJAS, R. 1980 [1924]) Eurindia. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina.

SARLO, B. (2007 [1988]) Una modernidad periférica: Buenos Aires 1920 y 1930. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión. SILVESTRI, G. (2011) El lugar común. Una historia de las figuras de paisaje en el Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires: Edhasa.

SZIR, S. (2017) “Imágenes y tecnologías entre Europa y la Argentina. Migraciones y apropiaciones de la prensa en el siglo XIX”. In: Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos, 6. http://nuevomundo.revues.org/70851 (accessed: June 12, 2017). TELL, V. (1999) “Gastón Bourquín: paisajista y editor”. In: 6° Congreso de Historia de la Fotografía. Salta: Sociedad Iberoamericana de Historia de la Fotografía.

_______ (2017) El lado visible. Fotografía y progreso en la Argentina a fines del siglo XIX. Buenos Aires: UNSAM Edita.

VAILLANT, A. (2009) “Identités nationales et mondialisation médiatique”. In Impressions du Mexique et de France, Andries, L. and Suárez de la Torre, L (dirs.), México: Instituto Mora: 115-144.

WECHSLER, D. (1991) “Paisaje, crítica e ideología”. In: Ciudad/Campo en las Artes en Argentina y Latinoamérica.

III Jornadas de Teoría e Historia de las Artes. Buenos Aires: CAIA: 342-350.

____________ (2014) “París, Buenos Aires, México, Milán, Madrid… Migraciones, tránsitos y convergencias para un mapa del arte moderno”. In Artelogie, 6. DOI:10.4000/artelogie.1228 (accessed, August 27, 2015).

WILLIAMS,R. (1973) The country and the city. New York: Oxford University Press. Spanish version: (2011) El

campo y la ciudad. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

___________ (1980) Marxismo y literatura. Barcelona: Península.

WINIWARTER,V. (2008) “Nationalized Nature on Picture Postcards: Subtexts of Tourism from an Environmental

Perspective.” In: Global Environment, 1: 192–215. http://www.environmentandsociety.org /node/4226 (accessed, June 26, 2017).

Catalina Fara is Art Historian and Professor by the University of Buenos Aires (UBA). PhD in History and

Theory of Art by the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) in 2016. Getty Foundation grantee, having participated from 2012 to 2015 in the “Connecting Art Histories” initiative, in the Program “Unfolding Art Histories in Latin America”.