Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

HB31

.M415

DEWEY

2^h

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

Do

Temporary

Help

Jobs

Improve

Labor

Market

Outcomes

for

Low

Skilled

Workers?

Evidence

from

Random

Assignments

David Autor

Susan

N.

Houseman

Working

Paper

05-26

October

27,

2005

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection atMASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTEOF

TECHNOLOGY

I

Do

Temporary Help

Jobs

Improve Labor Market

Outcomes

forLow-Skilled

Workers?

Evidence

from

Random

Assignments

October

2005

Revised

from

January

2005

Abstract

A

disproportionate share oflow-skilled U.S.workersisemployed

by temporary helpfirms.These firms offer rapid entry intopaidemployment,

buttemporaryhelpjobs aretypically briefanditisunknown

whethertheyfosterlonger-term

employment.

We

draw

upon

an unusual,large-scalepolicyexperimentinthestate of

Michigan

toevaluatewhetherholdingtemporaryhelpjobsfacilitateslabormarketadvancement

for low-skilled workers.To

identifytheseeffects,we

exploittherandom

assignment ofwelfare-to-

work

clients acrossnumerous

welfare service providers inamajormetropolitanarea.These

providersfeaturesubstantiallydifferentplacementratesattemporaiyhelpjobs but offerotherwise similar services.

We

find thatmoving

welfareparticipants intotemporary helpjobsboosts theirshort-term earnings.Butthesegainsare offsetby lowerearnings, lessfrequentemployment,

andpotentially higher welfare recidivismoverthenextonetotwo

years. In contrast,placementsin direct-hirejobsraise participants' earningssubstantially and reducerecidivismbothoneandtwo

years following placement.We

concludethatencouraginglow-skilled workerstotaketemporaryhelpagency jobs isnomore

effective

-

andpossibly less effective-

than providingno job placementsatall.David

H.

Autor

MIT

Department

of

Economics

and

NBER

50

Memorial

Drive,E52-371

Cambridge,

MA

02142-1347

dautor(g)mit.edu

617.258.7698

Susan N.

Houseman

W.E. Upjohn

Institute forEmployment

Research

300

S.Westnedge Ave.

Kalamazoo,

MI

49007-4686

houseman(g),upiohninstitute.org

269.385.0434

'

Thisresearchwassupported bythe RussellSage Foundation andtheRockefellerFoundation.

We

are particularly gratefiiltoJoshuaAngrist,OrleyAshenfelter,TimBartik,MaryCorcoran,JohnEarle,RandyEberts,JonGruber, Brian Jacob,Lawrence Katz,AlanKrueger,AndreaIchino,PedroMartins,JustinMcCrar)',Albert Saizand seminarparticipantsatMIT,the

NBER

SummerInstitute,theUpjohnInstitute,theUniversityofMichigan,theCenterforEconomicPolicy Research,theBankof

PortugalandtheSchumpeterInstituteofHumboldtUniversityforvaluable suggestions.

We

are indebtedtoLillian Vesic-Petrovicforsuperb research assistanceandtoLaurenFahey, EricaPavao,andAnneSchwartzforexpert assistancewithdata.Autor acknowledges generoussupportfromtheSloanFoundationandtheNationalScience Foundation

(CAREER

award SES-0239538).A

disproportionate shareofminorityand iovv-si<i!!edU.S.wori<;ers isemployed

by temporaryhelpfirms.In 1999,African

American

workers were overrepresented intemporaryhelp agencyjobs by 86percent, Hispanics by31 percent,and highschooldropouts by 59percent; by contrast,college graduates

were

underrepresented by 47percent(DiNatale 2002). Recent analysesofstateadministrativewelfaredata reveal that 15 to40 percentof formerwelfare recipients

who

obtainedemployment

intheyearsfollowingthe 1996 U.S. welfarereform tookjobs inthetemporaryhelpsector.' These

numbers

areespeciallystriking in light ofthe fact that thetemporary help industry accounts forlessthan 3 percentof

averageU.S.daily

employment.

The

concentrationoflow-skilledworkers inthetemporaryhelp sector has catalyzed a researchandpolicy debate aboutwhether temporary helpjobsfosterlabormarket advancement.

One

hypothesis isthatbecausetemporaiyhelp firms face lowerscreening andtermination costs thandoconventional,direct-hire

employers,they

may

choosetohire individualswho

otherwisewould have

difficultyfindinganyemployment

(KatzandKrueger

1999; Autor andHouseman

2002b;Autor2003; Houseman,

Kalleberg,and Erickcek2003). If so,temporaryhelpjobs

may

reducethetimeworkers spend in unproductive,potentially discouragingjobsearchandfacilitate rapid entryinto

employment.

Moreover, temporaryassignments

may

permitworkerstodevelophuman

capitaland labormarketcontactsthatlead, directlyorindirectly, tolonger-term jobs. Indeed,alarge and growing

number

ofemployersusetemporary helpassignments as a

means

toscreenworkers fordirect-hirejobs(Abraham

1988;Autor 2001;Houseman

2001; Kalleberg,Reynolds, and

Marsden

2003).Incontrastto thisview,

numerous

scholarsandpractitionershave arguedthattemporary helpagencies provide little opportunity orincentiveforworkers to investin

human

capital ordevelopproductivejobsearchnetworks andinstead offerworkers a seriesofunstableand primarily low-skilled

jobs (Parker 1994;Pawasarat 1997;Jorgensonand

Riemer

2000). Insupportofthis hypothesis,Segal andSullivan (1997)

fmd

thatwhilemobility outofthetemporary help sectorishigh, adisproportionateshare' SeeAutor andHouseman(2002b)

on Georgia andWashingtonstate;Cancianetal.(1999) on Wisconsin;Heinrich,Mueser, and Troske (2005) on NorthCarolinaandMissouri;and Pawasarat(1997)on Wisconsin.

ofleaversenters

unemployment

or exits the laborforce. Iftemporaryhelpjobs exclusivelysubstitute forspellsof

unemployment,

these factswould

beoflittleconcern.But

tothedegreethatspells intemporaryhelp

employment crowd

outproductive direct-hirejobsearch,theymay

inhibit longer-term laboradvancement.

Hence,

the shorttermgainsaccruing fromnearer-termemployment

intemporaryhelpjobsmay

be offsetby

employment

instabilityand poorearningsgrowth.Distinguishing

among

thesecompeting

hypotheses isanempirical challenge.The

fundamentalproblem

is thatthereareeconomically large, buttypicallyunmeasured, differencesin skillsandmotivationof workerstaking temporary helpanddirect-hirejobs,as

we show

below. Cognizant ofthesesample-selectionproblems,several recentstudies,

summarized

below,attemptto identify the effectsof

temporaryhelp

employment

on

subsequentlabormarketoutcomes

among

low-skillandlow-income

populations intheUnited States. Inaddition, aparallel

European

literatureevaluateswhether temporaryhelp

employment,

aswellasfixed-termcontracts,providea"steppingstone" intostableemployment.

Notably, theserecentU.S. and

European

studies,withoutexception,find thattemporaryhelpjobsprovidea viableportofentry intothe labormarket andleadtolonger-termlabormarket advancement.'

Inadditionto theirfindings, somethingthese studieshave in

common

isthattheydraw

exclusivelyon

observational datatoascertain causal relationships. Thatis,the research designsdepend

upon

regressioncontrol, matching,selection-adjustment, andstructuralestimationtechniquestoaccountforthe likely

non-random

selectionofworkers withdifferentearnings capacitiesintodifferentjobtypes.The

veracityofthe findingstherefore

depends

criticallyontheefficacy ofthesemethods fordrawingcausal inferencesfrom non-experimentaldata.

In thisstudy,

we

take analternativeapproachtoevaluating whether temporaryhelpjobs improvelabormarket

outcomes

for low-skilledworkers.We

exploitaunique, multi-year policy experimentin alarge

Michigan

metropolitan areainwhich

welfare recipientsparticipatingina return-to-workprogram

As

we

demonstrate below.Work

Firstparticipantsrandomly

assignedtodifferentcontractors hadsignificantly differentplacementrates intodirect-hireortemporary help jobs butotherwise received

similarservices.

We

analyzethisrandomizationusing an"intentionto treat"framework

whereby

randomizationalters theprobabilities thatindividualsareplacedindifferenttypes ofjobs(direct-hire,

temporary-help,

non-employment)

duringtheirWork

Firstspells.To

assessthelabormarket consequences oftheseplacements,we

use administrative datafrom

theWork

Firstprogram

linked withUnemployment

Insurance (UI)wage

recordsfortheentireStateofMichigan

forapproximately 39,000Work

Firstspells initiatedfrom

1999 to2003.The

Work

Firstdatainclude

demographic

informationonWork

First participantsand detailedinformationon

jobsfoundduring the program.

The

UI

wage

recordsenable ustotrackearnings ofall participantsovertime,aswellasprovide labormarkethistories on participants before

program

entry.Among

Work

First participantswho

foundemployment,

about20percentheldtemporary helpjobs.Our

primary findingisthat"marginal"direct-hireWork

Firstplacements-

thoseinducedby

therandom

assignmentofparticipantstoWork

Firstcontractors-

increase payroll earningsby severalthousanddollars,increase time

employed

byonetotwo

quarters,and lowerthe probabilityofrecidivismintothe

Work

Firstprogram

by 20 percentage points overthesubsequenttwo

years.These

relationshipsare significant,consistentacross randomization districts,and economically large.

By

contrast,we

findthattemporary-helpplacements improve

employment

andearningsoutcomes

only intheveryshort-term.Over

timehorizonsofonetotwo

years,temporaryhelpplacementsdo

not improve-

andquitepossiblyworsen

-

these labormarket outcomes. Ratherthanpromotingtransitionsto direct-hirejobs, temporaryhelpplacementsprimarily displace

employment

andearnings fromother(direct-hire)jobs.We

alsoconsiderand present strongevidence againsttwo

potential threats to validity.One

isthattheadverse findings

we

document

fortemporary helpjob placements could bedriven byageneral associationbetween "bad contractor" practicesanduseoftemporary helpplacements.

To

addressthisconcern,we

'GiventhediversityoflabormarketinstitutionsinEuropean economies,

thereisno presumptionthatthecross-country findings

firstestablish thattheestimated negativeconsequences of temporaryhelpplacements areevidentin

almostall oftherandomizationdistricts inour sample, and hencethat our findingsarenot driven bythe

poorpractices of oneor

more

aberrant contractors. Second,toexplorethe concernthattheremay

beotherimportant

unmeasured

contractor practices(e.g.,additional supportsandservices) thatexplain thelinkbetween

contractorrandom

assignments andparticipants' outcomes,we

testandconfirmthat thereis noremaining, significant variation inthe effectsof

Work

Firstcontractorson participantoutcomes

thatisnotcapturedby contractorplacementrates. Third,

we

find thatdirect-hireand temporaiy agency jobplacementrates arepositivelyandsignificantly correlatedacross contractors, a fact thatreducesthe

plausibilityofa scenario in

which "bad"

contractorsprimarily placeparticipants intemp

agencyjobs and"good"

contractorsprimarily place participantsindirect-hirejobs. These findingssuggestthatitisjobplacementrates themselves

-

nototherconfoundingfactors-

thataccountforourmain

findings.A

second concernwe

tackleisthepossibilityof parameterinstability. Becausecontractorshaveinternal discretionabout

which

clients toencourage towardwhich

jobtypes, our estimatesmightnotnecessarilyidentify astable"intentionto treat"relationship, as

would

occurifrandom

assignmentsuniformly raised orloweredthe probabilitythateachparticipantobtained agivenjobplacement

(temporary help, direct-hire,non-employment).

To

addressthis issue,we

exploit thepanelstructureofthedatatoanalyzethe labormarket

outcomes

ofparticipantswho

experiencemultipleWork

Firstspellsduring the

sample

window

andwho

are assignedtomultiple contractors(becauseof therepeatedrandomization). Fixed-effects instrumental variables

models

estimatedon

thissubsample affirm themain

findings:using only within-person,over-time variationin

outcomes

forparticipantsrandomly

assignedtocontractorswithdiffering placementpractices,

we

estimatethatdirect-hirejobs induced byrandom

assignmentsraise post-assignmentearningsand

employment,

whiletemporary helpplacements retardthem. CoiToboratingthis-evidence,

we

demonstratethat"marginal"workers placed intemporary helppositionshave

comparable

pre-placementearningshistories to marginal workersplaced indirect-hirepositions, again indicatingtliatthecontrastbetweentiiepositive labormarket

outcomes

ofdirect-hireplacements andthegenerally negative

outcomes

oftemporary helpplacements resultfromdifferences inthe quality ofjobs,notfrom differences inthe quality of workers placedinthesejobs.

Inadditiontopresenting findings

from models

based onthequasi-experiment,we

use our detailedadministrative datatoestimate conventional

OLS

andfixed-effectsmodels

forthe relationshipbetween

temporally help job-taking and subsequentlabormarket outcomes.Consistent withthe U.S. and

European

literatureabove

-

butoppositetoourmain, quasi-experimental estimates-

OLS

andfixed-effectsestimates indicate thatworkers

who

taketemporaryhelpjobsfare almostas wellasthose takingdirect-hire positions.

The

contrastwithour core findings suggestseither thatnon-experimentalestimates arebiasedby the

endemic

self-selectionof workers intojobtypes accordingtounmeasured

skills andmotivation, orthatthere aresubstantialdifferences betweenthe"marginal"treatmenteffectsrecovered by

ourquasi-experimentanalysis and "average"treatmenteffects oftemporary helpplacements observedin

non-experimentaldata.

We

suggestthatthe emerging consensus ofthe U.S.andEuropean

literaturesthattemporaryhelpjobsfosterlabormarket

advancement

-

based wholly on non-experimentalevaluation-should becarefully consideredin lightoftheevidence from

random

assignments."1.

Prior

evidence

and

the

Michigan

Work

First

quasi-experiment

a.

Prior

non-experimental

estimates

The

characteristics of workerswho

takedirect-hire andtemporaryhelpjobsdiffersignificantly.Even

in ourrelatively

homogenous

sample,we

findthatWork

Firstparticipantswho

taketemporaryhelpjobsare older,

more

likelytobeblack, and havehigher priorearningsinthetemporary helpsectorthandoparticipants

who

takedirect-hirejobs(see Table 1).Not

surprisingly,the contrastwith thosewho

takenoemployment

duringtheirWork

Firstspell ismuch

more

pronounced.These

contrastsunderscoretheOurmicroeconoiTiicevidenceanswersthequestionof whethertemporar)' helpjobsbenefit theindividualswhotakethem, butit

doesnotinformthequestionofwhetherthe activitiesoftemporaryhelp finnsandotlierflexiblelabormarketinstitutions(suchas

fixed-term contracts)improveor retard aggregate labormarket performance by reducingsearchfrictionsorimprovingtliequality

of worker-firmmatches.SeeKatzand Krueger(1999).Blanchardand Landier(2002),Garcia-PerezandMunoz-Builon(2002),

difficultyofdisentanglingthe effects ofjob-takingon subsequent labormarket

outcomes from

thecausesthatdetermine

what

jobs aretakeninitially.Several recent studiesattemptto

overcome

problemsof

sample selection.Lane

etal. (2003)usematched

propensity scoretechniquestostudytheeffects of temporaryagencyemployment on

the labormarket

outcomes

oflow-income

workersand

thoseat riskof beingon welfare.They

cautiouslyconcludethattemporary

employment

improves labormarketoutcomes

among

thosewho

mightotherwise havebeen unemployed,

andthey suggestthe useof temporaiy helpjobs by welfare agenciesasameans

toimprove

labormarket outcomes.However,

theyacknowledge

thatintheirSurvey

ofIncome

andProgram

Participationdata it

was

infeasible toconstructcomparison groupsthatwerewell-matched

on earningshistories but differed on jobtypes,

which

led toapotential bias intheestimates.Using

aresearchpopulationand

databasecloselycomparable totheone usedinthis study,Heinrich,Mueser. andTroske (2005) study'theeffectsof temporary agency

employment

on subsequentearningsamong

welfare recipientsintwo

states.To

controlforpossible selectionbias inthedecisiontotakeatemporaiy agencyjob, they estimate a selection

model

that is identifiedthroughthe exclusionofvariouscounty-specificmeasures

from

themodels

forearnings but notfrom

thoseforemployment.

Interestingly,thecorrectionfor selection biashas littleeffect

on

theirregression estimates, suggesting either thattheselection

problem

is unimportantorthat theirinstrumentsdo notadequatelycontrol forselectionon4

unobservable variables. Like

Lane

etal. (2003), they findthattheinitial earningsofthose takingtemporaryhelpjobsare lower than ofthose taking direct-hirejobsbutthatthey aresignificantly better

thanofthose

who

arenotemployed

andtendtoconverge overtwo

years towardtheearnings ofthoseinitiallytakingdirect-hirejobs.

An

alternativeapproach, pursued by Ferber and Waldfogel (1998) and Corcoran andChen

(2004),istoestimatefixed-effects regressionstoassess whetherindividuals

who

move

intotemporary-helpandother non-traditionaljobsgenerallyexperience

improvements

in labor-marketoutcomes.A

virtueofthe"*

Theirempirical strategyassumesthatthe county-level variablesusedtoidentifythe selectionmodelinfluence earningsonly

fixed-effect

model

isthatitwill purgetime-invariant unobservedheterogeneity in individualearningslevels thatmightotherwise be a source ofbias.

However,

ifthere isheterogeneityin earningstrajectories(ratherthan inearnings levels) thatiscorrelatedwith job-taking behavior,the fixed-effects

model

will notresolve this bias.''

As

isconsistentwithotherwork, thestudies byFerberand Waldfogel (1998) andCorcoran and

Chen

(2005) find thattemporary helpandothernon-standardwork

aiTangementsareassociated with

improvements

inindividuals' earningsandemployment.

Numerous

recent studies have addressedthe roleof temporaryemployment

in facilitatinglabormarkettransitions inEurope. Usingpropensity scorematching methods,Ichino etal.(2004, 2005)

concludethat,relative to startingoffunemployed, beinginatemporary help jobsignificantlyincreases

the probabilityoffinding permanent

employment

within 18months. Ina similarvein, Gerfinetal.(forthcoming)use matching techniquestoestimatethe effectofsubsidizedtemporaryhelpplacements

on

the labormarketprospectsof

unemployed

workersinSwitzerlandandfind significantbenefits totheseplacements.Booth,Francesconi, and Frank(2002)and Garcia-Perez and

Munoz-Bullon

(2002) studytheeffects

on

subsequentemployment outcomes

of temporary (agencyand fixed-term)employment

inBritainand temporary

agency

employment

inSpain, respectively.Theirempirical strategies aresimilartothoseused in Heinrich, Mueser, and Troske (2005), andtheyfindgenerally positive effects oftemporary

employment,

as well.Using

matching andregression controltechniques, studiesbyAndersson

andWadensjo

(2004),Amuedo-Dorantes,

Malo,andMunoz-Bullon

(2005), and Kvasnicka (2005)also findpositiveeffectsof temporary help

employment on

labormarketadvancement

forworkers inSweden,

Spain,and

Germany,

respectively.Zijl etal.(2004) apply astructuraldurationmodel

to estimate theeffectoftemporary helpjob-takingondurations todirect-hire("regular")

work

intheNetherlandsand

concludethattemporary helpjobs substantially reduce

unemployment

durationsand increasesubsequentjobstability.

Thefixed-effectsestimatorisideallysuitedtoaproblemwheresuccessiveoutcomeobservationsforeachindividualreflect

simpledeviationsfroma stablemean,i.e.,afi,\ed,additive errorcomponent. Butmanylow-skilledworkers,andespeciallythose receiving welfare,are likely tobeundergoingsignificant shiftsinlabor forcetrajectory astheytransitionfromnon-employment

toemployment. Thisheterogeneity inslopes ratlierthanintercepts will notbe resolvedbythe fixed-effectsmodel.InSection3,

While

all ofthesenon-experimental studies concludethattemporaryhelpjobs improve subsequentlabormarket outcomes,

we

believethat the importance oftheresearch questionalso warrants anexperimental(orquasi-experimental) evaluationtoexploretherobustnessoftheseconclusions.

We

pursuesuchanapproachhere.'

b.

Our

Approach:

The

Michigan

Work

First

quasi-experiment

Most

recipients ofTANF

('Temporary AssistanceforNeedy

Families')benefitsmust

fulfillmandatory

minimum

work

requirements. In Michigan,thoseapplyingforTANF

benefitswho

do notmeet

thesework

requirementsmust

beginparticipating inaWork

Firstprogram

designedto helpplacethem

inemployment.

Foradministrativepurposes, welfareandWork

Firstservicesinthe metropolitanarea

we

studyaredivided intogeographicdistricts,which

we

referto asrandomizationdistricts.The

Work

Firstprogram

isadministeredbyacity agency,but the actual provisionofservicesis contracted outtonon-profit orpublic organizations. Within each geographic district,onetothree

Work

Firstcontractorsprovide servicesfor

TANF

recipientsresiding inthedistrictineachprogram

year.When

multiplecontractors provide

Work

Firstservices within adistrict,theyalternatetaking innew

participants.Thus,thecontractorto

which

aparticipantisassigneddepends onthe datethat heor she appliedfor benefits.As

we

demonstrate formally below,thisintakeprocedure is functionally equivalenttorandom

assignment.As

thename

implies,theWork

Firstprogram

focusesonplacingparticipants intojobs quickly. Allcontractors operating inourmetropolitanareaoffera fairlystandardized

one-week

orientationthatteachesparticipants basicjob-search andlifeskills. Services suchaschildcareandtransportation are

provided

by

outsideagencies andareavailableon anequal basis to participants atallcontractors.By

thesecondweek

oftheprogram, participantsare expectedtosearch intensively foremployment

and areformally requiredtotakeany jobofferedto

them

provided it paysthe federalminimum

wage

and'Theapproachtaken

inthispaperfollowsourearlier pilotstudy(AlitorandHouseman2002a),whichexploits asmaller

quasi-experimentalrandomization of

Work

Firstparticipantsinanothermetropolitan areaofMichigan and analyzesonlyshort-temi labormarketoutcomemeasures. (UnemploymentInsurancewagerecordswerenot availablefor thatstudy.)Theearlierstudyandthecurrentworkboth findpositiveshort-temieffectsof temporaryhelpplacements onearnings.ByutilizingUIrecordsto

satisfies

work

hoursrequirements. Althougli Wori< First participantsmay

findjobs ontlieirown, jobdevelopersat eachicontractor play anintegral roleintheprocess. Thisrole includesencouragingand

discouraging participants fi-omapplyingforspecificjobsandto specificemployers, referringparticipants

directly tojob sitesforspecific openings, andarrangingon-sitevisitsby employers

-

including temporaryhelp agencies

-

thatscreenand recruitparticipants attheWork

Firstoffice.For example,Autor andHouseman

(2005,Table 1)report that24percentofcontractorssurveyed inthismetropolitan areareferparticipants totemporaryhelpjobson a

weekly

basis,while 38 percentmake

suchreferralsonlysporadically or never. Similarly, 14 percentofcontractors directly invitetemporaryhelpagencieson-site

weekly

ormonthly

to recruit participants, while29 percentofcontractorsneverdoso.The

correlationsbetweenthese frequenciesandcontractors' (self-reported)temporaryagency placementrates are0.29for

on-site visitsand 0.53 fortemporaryagencyreferrals,thelatterof

which

is highlysignificant. Thisindicates thatthejobs that participantstake

depend

in partoncontractors'employer

contactsand,more

generally, onpolicies that foster ordiscouragetemporary agency

employment

among

participants.It is logical toask

why

contractors' placementpractices significantly vary.The most

plausibleanswer

isthatcontractors areuncertainabout

which

types of job placementsaremost

effectiveand hence pursuedifferent policies.Contractors do nothaveaccessto

UI

wage

recordsdata(used in thisstudy toassessparticipants' labormarket outcomes), andthey collectfollow-updataonlyforashorttime periodand

onlyforindividuals placedinjobs. Hence,theycannotrigorously assesswhether job placements improve

participant

outcomes

orwhetherspecificjob placementtypes matter.During in-personandphone

interviewsconducted forthisstudy, contractors expressedconsiderable uncertainty,and differing

opinions, aboutthe long-termconsequences of temporary job placements (Autor and

Houseman

2005).We

exploit these differences,which impacttheprobabilityoftemporary agency,direct-hire,ornon-employment

among

statistically identical populations,to identifythe effects ofWork

Firstemployment

Participants reenteringthesystemforadditionalWorkFirstspellsfollow thesameassignment procedureandthusmaybe

and jobtypeon long-termearningsand

program

recidivism. Inoureconometricspecification,we

usecontractorassignmentasan instrumental variable affectingtheprobabilitythata participant obtains a

temporary help job, adirect-hirejob, or

no

job duringtheprogram.Our methodology

doesnotassume

thatcontractorshave noeffecton participantoutcomes

otherthanthroughtheireffects

on

job placements-

onlythatanyother practices affectingparticipantoutcomes

areuncorrelatedwithcontractorplacementrates.

However,

fewresourcesarespenton anything butjobdevelopment

(AutorandHouseman

2005).General orlifeskillstraining providedinthe firstweek

oftheWork

Firstprogram

isvery similar acrosscontractors.And

supportservices intendedto aidjobretention,suchaschildcare andtransportation,are equally availabletoparticipants inallcontractorsandare

providedoutsidetheprogram.

Survey

evidencecollected forthe majorityofcontractors in oursampleconfirmsthat

Work

Firstservices otherthanjob placementsarealmostentirelystandardized acrosscontractorsoperating in thismetropolitanarea(Autorand

Houseman

2005). InSection4,we

provideeconometric evidence supportingthevalidityoftheidentificationassumption.

2.

Testing the research design

a.

Data

and

sample

Our

research dataarecomprised ofWork

Firstadministrative records data linkedto quarterlyearnings

from

the Stateof Michigan'sunemployment

insurancewage

records data base.We

useadministrativedataonall

Work

First spells initiatedfromthe fourthquarterof1999 throughthe firstquarterof

2003

inthemetropolitanarea.The

administrative datacontain detailed informationon

jobsobtainedby participantswhilein the

Work

Firstprogram.To

classifyjobs intodirect-hireand temporaryhelp,

we

use thenames

ofemployersatwhich

participantsobtainedjobsinconjunctionwithcarefullyq

compiled lists of temporary helpagencies in themetropolitanarea. Inasmall

number

ofcaseswhere

the*Inasurveyofcontractorsoperatinginthis city,half indicated theyweredirectlyinvolvedin75percent ormoreofWorkFirst

participantjob placements, and85 percentofcontractorstookcredit formoretlian50percentofthejobs obtainedintheir

program(AutorandHouseman2005).

'Particularlyhelpftilwasacomprehensivelistof temporaryagencies operatinginourmetropolitan areaasof 2000, developed by DavidFasenfestandHeidi Gottfried.

appropriate coding ofan

employer

was

unclear,we

collected additional informationonthe natureofthebusinessthroughaninternetsearch ortelephonecontact.

We

alsousetheadministrative datatocalculatetheimplied

weekly

earnings foreachWork

Firstjobbymultiplyingthehourlywage

ratebyweekly

hours.

The

Ul data include totalearningsin thequarterandthe industry inwhich

theindividual hadthemost

earningsinthe quarter.

We

usethem

toconstruct pre- andpost-Work

FirstUI earnings foreachparticipant forthe fourtoeight quarters prior toand subsequenttothe

Work

First placement.In 14 ofthedistricts inthe metropolitanarea,

two

ormore

Work

Firstcontractors servedthedistrictoverthetime period studied. In

two

districts,however, one contractorineachdistrictwas

designatedtoserve primarily ethnic populations,andparticipantswere allowedtochoosecontractorsbasedon language

needs.

We

dropthesetwo

districtsfrom

oursample.We

further limitthesampleto spellsinitiatedwhen

participantswere

between

the ages of16and 64 and dropspellswhere

reportedpre-orpost-assignmentquarterly

UI

earnings valuesexceed $15,000 in asinglecalendarquarter. These restrictionsreduce thesample by lessthan 1 percent. Finally,

we

dropall spells initiated inacalendar quarter inanydistrictwhere

oneormore

participating contractorsreceivednoclients duringthe quarter, asoccasionallyoccurred

when

contractorswere terminated andreplaced.Table 1 summarizes the

means

ofvariableson demographics,work

history,andearnings followingprogram

entry forallWork

Firstparticipants inourprimarysampleaswellas byprogram

outcome:direct-hirejob, temporaiyhelp job, ornojob.

The

sample ispredominantly female(94 percent)and black(97percent). Slightlyunderhalf (47 percent)of

Work

Firstspells resultedinjob placements.Among

spellsresulting injobs, 20 percenthave at leastone jobwith atemporaryagency.

The

average earningsandtotal quartersof

employment

overthe fourquarters followingprogram

entry arecomparable forthoseTheUIwagerecordsexcludeearningsoffederalandstateemployees and oftheself-employed.

'

'Thisfurtherreducedthe finalsample by3,091spells,or7.4percent.

We

haveestimatedthemainmodelsincluding theseobservations with near-identicalresults.

obtainingtemporaryagency and direct-hire jobs, while earnings andquartersof

employment

forthosewho

do not obtainemployment

duringtheWork

First spell are40

to50percent lower.The

averagecharacteristics ofparticipants varyconsiderablyaccordingtojob outcome.Those

who

do

not findjobs whilein

Work

Firstaremore

likely tohave droppedoutof highschool,tohaveworked

fewerquarters before entering the program, andtohave lowerprior earnings than those

who

find jobs.Among

thoseplaced injobs,those takingtemporai7agency

jobs actuallyhavesomewhat

higheraveragepriorearningsandquarters

worked

than those takingdirect-hirejobs.Not

surprisingly, thosewho

taketemporally jobswhile inthe

Work

Firstprogram

havehigherpriorearnings andmore

quartersworked

inthetemporary help sectorthanthose

who

takedirect-hire jobs. Data used inpreviousstudiesshow

thatblacksare

much

more

likelythan whites towork

intemporary agency jobs (Autor andHouseman

2002b;Heinrich, Mueser, and Troske2005).

Even

in ourpredominantly African-American sample,we

also findthisrelationship.

The

tablereveals onefurthernoteworthypattern:hourly wages,weekly

hours, andweekly

earningsareuniformlyhigherforparticipantsintemporary helpjobsthan forthose in direct-hirejobs. This pattern

stands in contrasttothewidelyreported finding oflower

wages

intemporary help positions (Segal andSullivan 1998; General

Accounfing

Office2000; DiNatale2001).Although

it is possiblethatthispatternisspecific totheregional labormarket

we

study,many

studiesthatreportlowerearnings fortemporaryhelp

agency

jobs, includingSegal and Sullivan (1998),relyon quarterlyunemployment

insurancerecordswhich

reporttotal earnings but nothoursof work.Because

temporary help jobs aregenerallytransitory,theabsence of hours information in UI data

may

lead tothe inferencethattemporary helpjobspay lowerhourly

wages

when

in facttheysimply provide fewertotal hours.b.

Testing

the efficacy of the

random

assignment

If

Work

Firstassignments arefunctionally equivalenttorandom

assignment, observedcharacteristicsofclients assignedto contractors within arandomization districtshouldbe statisticallyindistinguishable.

'^Note

thatbecauseparticipantswhodonotfindjobs duringtheirWorkFirstassignmentsface possible sanctions, unsuccessful participantscontinuetofacestrongworkincentivesafterleavingWorkFirst.

We

testtherandom

assignment across contractors withinrandomization districtforeachprogram

year bycomparing

the following tenparticipant characteristics; gender,white race, other(non-white)race, age,elementary-school-onlyeducation,post-elementary high-schooldrop-outeducation,

number

ofquartersworked

intheeight quarters beforeprogram

entry,number

ofquarters primarilyemployed

with atemporary agency inthese prioreightquarters,total earnings inthese prioreight quarters,andtotal

earningsinthe prioreight quarters

from

quarterswhereatemporaryagencywas

the primary employer.With

ten participantcharacteristics,we

are likelytoobtainmany

falserejectionsofthe null(i.e..Type

Ierrors), andthisisexacerbatedby the fact thatnotall participant characteristics areindependent(e.g.,

lesseducated participants are

more

likely to beminorities).To

resolve these confoundingfactors,we

usea

Seemingly

Unrelated Regression(SUR)

systemtoestimatetheprobabilitythattheobserveddistributionofparticipantcovariates across contractors withineach randomizationdistrictandyearisconsistentwith

chance. ^

The

SUR

accountsforboththe multiplecomparisons(ten)simultaneously ineach districtand

thecorrelations

among

demographic

characteristicsacrossparticipantsateachcontractor.Formally,let X*„ be a

^xl

vectorofcovariatescontaining individual characteristics forparticipant/ assignedtoonecontractorin district

d

during year t. Let Z^, be avectorofindicatorvariablesdesignating thecontractorassignment forparticipant /,

where

thenumber

ofcolumns inZ

isequalto thenumber

ofcontractors in districtd

. Let /,. bea ^ by k identitymatrix.We

estimatethefollowingSUR

model:

(1)

x,=(/,®(z„

1))^+^

x„={xi,:,...,x:;)'.Here, Xj^ isastackedsetoftheparticipant covariates, theset ofcontrol variables include contractor

assignment

dummies

anda constant, and^

isa matrixoferrortermsthatallows forcross-equationcorrelations

among

participant characteristicswithin district-contractorcells.'""The

p-value forthe joint'^This

methodfor testingrandomizationacrossmultipieoutcomesisproposedbyKlingetal.(2004)and Kiing andLiebman (2004).

Since the contractorassignmentdummiesin Z aremutuallyexclusive,oneisdropped.

significanceofthe elements of

Z

in thisregressionsystem providesanomnibus

testforthenullhypothesisthatparticipant covariatesdonot differ

among

participantsassignedtodifferentcontractorswithin adistrict

and

year;ahighp-value correspondstoan acceptance ofthis null.Table 2 providesthe chi-squarestatistics andp-valuesforthesignificance of

Z

inestimatesofEquation(1) foreach ofthe 41 district-by-yearcells inoursample. Consistent withthe hypothesisthat

assignment ofparticipantsacross contractors operatingwithineach district is functionally equivalentto

random

assignment,we

find that46 of48

comparisonsacceptthe nullhypothesis atthe 10percent leveland

47

of48 at the 5 percent level.We

nextperform groupedstatisticalteststoevaluate thevalidityoftherandomizationforthe entireexperiment. Sinceparticipantassignmentsare independentacrossdistricts

and overtime, thechi-squareteststatistics ineachcellcan be

combined

toform anoverall chi-squaredtest statistic

(DeGroot

and Schervish 2002,Theorem

7.2.1).As

isshown

inthefinalrow and column of

Table2,the overall p-valueoftherandomizationacrossall41 cells inoursamples is0.33,with

587

degreesof freedom. Moreover,the nullofparticipantbalance across contractorswithin districtsis

acceptedatthe 5percentlevelorbetter ineach ofthe 12districts and inall fouryearsofthesample.In

sum,thedataappeartoaffirmthe efficacyofthe

random

assignment.c.

The

effect

of

contractor

assignments

on

job

placements

Our

research designalso requiresthatcontractorrandom

assignmentssignificantly affectparticipantjob placement outcomes.

To

testwhetherthisoccurs,we

estimatedasetofSUR

models akinto equation(1)

where

the dependentvariables areparticipantWork

Firstjoboutcomes

(direct-hire,temporary help,non-employment).

These

tests providestrong supportforthe efficacyofthe research design:alltestsofcontractor-assignmenteffectson participantjob placements

-

eitheracross contractorswithin a year or'^

Sevenof 48district-by-yearcellsaredropped becausethereisonlyone(orinsomecasesno) participating contractorinthe

districtformostorallofthe year. Intwodistrict-by-yearcells,one matchingcharacteristics(raceor education)wasidentical for

allrandomly-assignedparticipants;wetherefore didnottestforequalityofthis characteristicwithin thecell,andthedegreesof freedomforthechi-squarestatisticarereducedaccordingly.

within contractors across years

-

rejecttinenull atthe 1 percentlevel orbetter.The omnibus

testforall 41comparisonsalso rejectsthe nullat well

below

the 1 percentlevel.'*Are

the effects of randomization on participantjobplacementoutcomes

economically large inadditionto beingstatistically significant?

To

answerthisquestion,we

calculatepartialR-squared valuesfromaset ofregressions ofeachjob placement

outcome on

therandom

assignmentdummy

variables.Thesepartial-R-squared values are0.019 forany

employment.

0.013 fortemporary helpemployment,

and0.011 fordirect-hireemployment.

We

benchmark

thesevalues againstthe partialR-squaredvalues from asetofregressions ofthethreejob placement

outcomes

on

allotherpre-determined covariatesin ourestimates including theten

demographic

andearnings history variablesdiscussedabove andacompletesetofdistrict-by-year andcalendar-year-by-quarterofassignment

dummies.

The

partial-R-squared valuesforthesepre-determined covariatesare0.036 forany

employment,

0.024 fortemporaryhelpemployment,

and 0.026 fordirect-hire

employment.

A

comparison ofthetwo

sets ofpartialR-squared valuesshows

thatthe

random

assigmnentsexplain40to 55 percentasmuch

ofthe variation injob placementoutcomes

among

participants asdothecombined

effects of demographics,earnings history,anddistrictand timeeffects.

We

concludethattheeconomic

magnitude ofthe randomizationon

job-takingoutcomes

issubstantial.

3.

Main

results:

The

effects

of

job

placements

on

earnings

and

employment

We

now

use thelinked quarterly earnings records fromthe stateof Michigan'sunemployment

insurancesystem toassess

how Work

Firstjob placementsaffect participants' earningsandemployment

overthesubsequenteightcalendar quarters following

random

assignment.Our

primaryempiricalmodel

is:

(2) };„„

=a

+

/ij,+P,D,+

X;p, +

y,+0,+

{y,x0,)+

f,^.,,,

^Tablesdisplaying these

resultsareavailablefromtheauthors.Atthe district-by-yearlevel,werejectthe nullhypothesisof no

contractoreffectson job placement outcomesin36 of41district-year cellsatthe1percentlevel,andwerejectatthe 5percent

level in39of41 cells.

where

thedependentvariable is realUI

earnings or quarters of UIemployment

followingthequarterofWork

Firstassignment. Subscript ; refers toparticipants,d

to randomizationdistricts, c tocontractorswithinrandomizationdistricts, and t toassignmentyears.

The

variables Z), and 7^ are indicatorsequaltoone

ifparticipant i obtained a direct-hire ortemporary-agency jobduring theWork

Firstspell.The

vectorofcovariates,

X

, includesgender, race (white, black, or other), age,education (primary school only,highschool dropout, highschool graduate, greaterthan highschool), and

UI

earnings(in real dollars) forthe4quartersprior to

random

assignment.The

vectorsy

and containdummies

forrandomizationdistrictsand

yearby

quarterofrandom

assignment.The

coefficients ofinterest inthismodel

are /]^ and /?,,which

providetheconditionalmean

difference inhoursandearningsfor participants

who

obtaineddirect-hire ortemporary-agencyjobsduringtheir

Work

Firstspells relative toparticipantswho

did notobtainanyemployment.

The

estimationsample

includes38,689 participantspells initiatedbetween

1999 and2003

inthe 12randomizationdistricts inour sample.

To

accountforthegrouping ofparticipants withincontractors,we

useHuber-1

R

White

robust standard errorsclusteredatthecontractor x yearofassignment level.Insubsequent two-stage leastsquares

models

(2SLS),we

instrumentT

andD

withcontractor-assignment-by-year

dummy

variables.For purposes ofthe2SLS

models, useofthese contractor-by-yeardummy

variables is almost identical tousing contractor-yearplacement jobrates(byjobtype)asinstrumental variables. Accordingly,this

model

can be convenientlyapproximatedas"It isnot yet feasibletotrackpost-assignmentearningsformorethan eight quartersbecausemanyoftheWorkFirst

assignmentsinourdataoccurredasrecently as2002and 2003.

'^Thesestandarderrorsdonot,however, accountforthefact thatthereare25,802 uniqueindividuals representedinourdataand

sosomeparticipantshaverepeatspells,whichmayinduceserialcorrelationinemploymentoutcomesacrossspells forthesame individual.

We

demonstratebelowthatourresultsarequalitativelyidenticalwhenthesampleislimitedtothe firstspellforeachparticipant(see alsoAppendixTable 1).

"

It isalmostidentical becausemeansanddummy

variableswilldiffer slightlyifthereisany samplecorrelationbetweencontractordummiesandparticipantcharacteristics.However,wehavealready establishedtliat,becauseoftherandom assignment,thiscorrelationisnot significantly differentfromzero.

where

Pa

andPa

are contractoi"x yeartemporary helpanddirect-hire placementrates, andwhere

theerror term is partitioned into

two

additivecomponents, e.^j,=

r^,+

co^^^^.The

firstis acontractor-by-yearrandom

effect, reflecting unobservedcontractor heterogeneity.The

secondisaparticipant-spell specificiid

random

errorcomponent. Equation(3) underscores thetwo key conditionsthatour identificationstrategy requiresfor valid inference. First, it mustbethecasethat co isuncorrelated with

Pa

andPa

, aconditionthatis (almost)guaranteedtobe satisfied bytherandomization.

The

second condition isthatcontractor-by-year

random

effectsaremean

independentofcontractorplacementrates, i.e.,E{v^^Pj)

=

£(v'„P^°) .It istherefore not problematicforourestimation strategy ifcontractors havesignificant effectsonparticipant

outcomes

throughmechanisms

otherthanjob placements(e.g.,otheractivitiesand supports)providedthattheseeffects arenotsystematicallyrelated tocontractorjob

placementrates.

We

proceed fornow

undertheassumptionthatthis condition issatisfied andexamine

corroborating evidencein Section4.

a.

Ordinary

least

squares estimates

To

facilitatecomparisons withearlier empirical work,we

begin ouranalysiswith ordinary leastsquares

(OLS)

estimatesof Equation (2).The

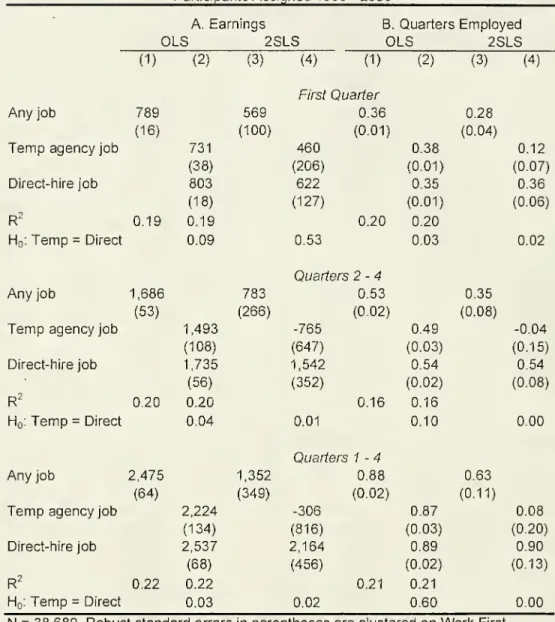

firsttwocolumns

of Table 3 presentsOLS

estimates ofEquation (2) forrealearnings andquarters of

employment

for thefirst four calendar quartersfollowingWork

Firstassignment forall38,689 spellsinourdata.As

shown

incolumn

(1),participantswho

obtainedany

employment

duringtheirWork

First spellearned$789

more

inthecalendar quarterfollowing UI placementthan didclients

who

did not obtainemployment.

Interestingly, there is littledifference

between

thepost-assignmentearningsofparticipants takingdirect-hireand temporary helpjobs. Firstquarter earningsare estimatedat$803 and $731, respectively.

These

contrasts are significantlydifferentfromzero butnotsignificantly differentfrom oneanotheratthe 5 percent level {

p

=

.09).Additional rows of Table 3 repeat the

OLS

estimatesfortotalUl

earningsinthefourquartersfollowing

program

entry.Participantswho

obtained anyemployment

duringtheirWork

Firstassignmentearned approximately $2,500

more

overthe subsequentcalendaryear than thosewho

did not. Inallassignmentquarters, those

who

obtaineddirect hireplacements earned about 15 percentmore

than thosewho

obtainedtemporaryhelpplacements. PanelB,which

presents comparableOLS

models

forquartersof

employment

followingWork

First assignment,shows

thatparticipantswho

obtaineddirect-hireortemporary helpjobs

worked

about0.9calendar quartersmore

overthesubsequentyearthandidparticipants

who

did notfind work.Table 4 extendsthe UI earnings and

employment

estimatestotwo

fullcalendar years followingWork

20

Firstassignment.

Over

thisperiod, participantswho

obtainedtemporary helpanddirect-hire placementsearned $3,385 and $4,212

more

thanthosewho

did not findajob andworked

anadditional 1.2and 1.3quarters respectively(bothsignificantat

p

=

0.01).b.

Instrumental

variables

estimates

The

precedingOLS

estimates areconsistentwithexisting research,most

notablywith Heinrichet al.(2005),

who

findthatMissouri andNorth Carolinav/elfarerecipients takingtemporaryhelpjobs earnalmostas

much

overthesubsequenttwo

yearsasthoseobtaining direct-hireemployment -

andmuch

more

than non-job-takers. Like Heinrichetal., ourprimary empiricalmodels

forearnings andemployment

containrelatively rich controls, includingprior(pre-assignment) earningsandstandarddemographic

variables. Instrumental variables estimatesforthe labormarket consequences ofWork

Firstplacements appear initiallytobe consistentwiththe

OLS

models.The

2SLS

models

incolumns

(3)and (4)of Table 3 confirm aneconomically largeandstatisticallysignificantearnings gainaccruing

from

Work

Firstjob placements during thefirstpost-assignmentquarter.The

estimated gaintoaWork

Firstjob placement,

$559

(/=

5.8),isabout 25 percentlessthanthe analogousOLS

estimate.When

job placements aredisaggregated byemployment

types, however, discrepanciesemerge.Temporary

help anddirect-hirejob placements are estimatedto raise quarterone earningsby$460

and^°To

includeU!outcomesforeightcalendar quartersfollowingassignment,wemustdropallWorkFirstspells initiated after

2002.This reducesthesampleto27,029spells. ^'

Allof ourmainmodelscontrol fordemographic andearnings history covariates as wellas fortimeanddistrictduinmies and

theirinteraction.

OLS

(butnotIV)estimatesofwageandemploymenteffectsofdirect-hireand temporary-help placementsareabout 20percentlargerwhenthesedemographic and earnings history controlsareexcluded(estimates availablefromthe authors).

$622

respectively.Both arestatisticallysignificant. Whileavailableprecisiondoesnotallow usto rejectthe nullhypothesis thatthese point estimates are

drawn

from

thesame

distribution{p

=

0.49), itisnoteworthythatthe

IV

estimatefortheearningsgainfrom temporaryhelp placementsisapproximately25 percentsmaller thanthe

wage

gainfor direct-hirejobs.Comparable

2SLS

models

forquartersofemployment

(ratherthan earnings)confirm important differences intheemployment

consequences oftemporary helpanddirect-hirejob placements.Placements in direct-hirejobsraisethe probabilityofany

employment

inthefirst post-assignmentquarterby 36 percentage points (?=

6.1).By

contrast,placements intemporaiy helpjobsraisetheprobability offirstquarter

employment

by only 12 percentagepoints. Thispoint estimateis notdistinguishable from zero(/

=

1.7), but itis significantly differentfrom

the pointestimatefordirect-hireplacements.

When

thewage

andemployment

analysis isextendedbeyond

thefirst post-assignmentquarter,a farmore

substantial disparity isevident. In thefirstfourcalendarquarters followingassignment.Work

Firstclientsplaced intemporary helpjobsearn$2,470 lessthan those receiving adirect-hire placement and

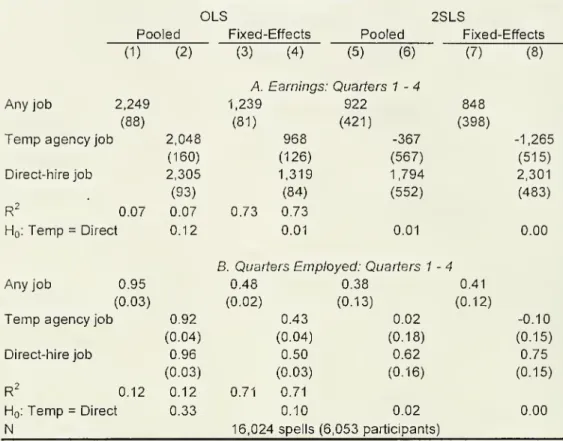

$306

lessthan those receivingno placementatall(thoughthis lattercontrastis insignificant). Estimatesforquarters of

employment

tellacomparablestory. Direct-hire placementsraise totalquartersemployed

by0.90 overthesubsequent fourcalendar quarters{t

=

6.5), whiletemporaryhelpplacementshave aneconomically small andstatistically insignificanteffectontotal quarters

worked

inthefirstyear.Examining outcomes

overatwo-yearperiod followingWork

Firstassignment(Table4)addstothestrengthoftheseconclusions. Estimated lossesassociatedwithtemporary helpjob placements are sizable,

$2,176 in earningsand0.16 calendar quartersof

employment,

thoughnotstatisticallysignificant.By

contrast, direct-hireplacementsraise earningsby $6,407 andtotalquarters of

employment

by 1.56overtwo

years. Forboth estimates,we

caneasily reject the null hypothesisthatthe effects ofdirect-hire andtemporary-help job placements areequal.

The

clearpicture thatemerges fromthese2SLS

models

isthattemporaryhelpplacements

do

notimprove

-

andpotentiallyharm

-

labor marketoutcomes

fortheWork

Firstpopulation.-"

c.

The dynamics

of earnings,

employment,

and

Work

First

recidivism

To

betterunderstandthe disparate impacts oftemporary helpand direct-hirejobplacements,we

explore the

dynamics

underlyingtheseoutcomes.We

firstestimate asetof2SLS

models thatdistinguishbetween

employment

and earnings intemporary help versusdirect-hire jobs. Specifically,we

estimate avariantofEquation(2)

where

thedependentvariable isearnings oremployment

intemporary helpemployment

ordirect-hireemployment.

Participantsnot receiving earnings oremployment

inthe relevant23 sectorare

coded

aszero tortheseoutcome

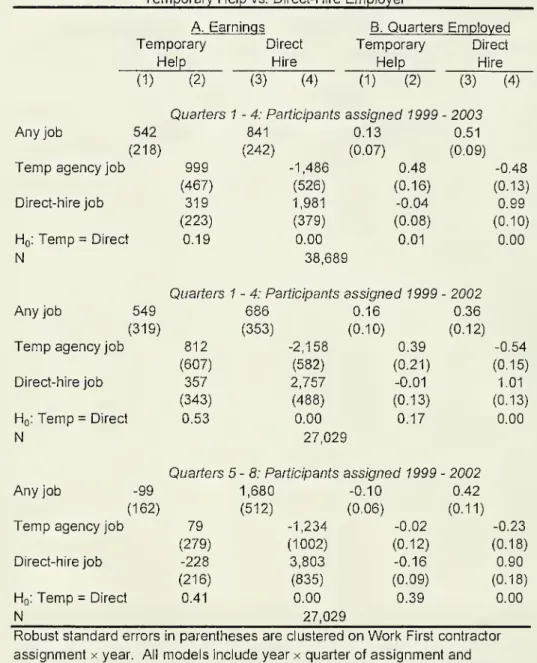

measures.Table5

shows

thatmarginaltemp

workersearnan additional$999

andwork

an additional0.48quarters intemporary help jobs inthe firstcalendaryearfollowing

random

assignment.(Botharesignificant.)

However,

these gains intemporaryhelp earningsandemployment

appeartocome

attheexpense ofearnings and

employment

indirect-hirejobs.We

estimatethattemporary help placementsdisplace $1,486 indirect-hireearningsand 0.48 quarters indirect-hire

employment

inthefirstyear.On

net,the first-quarterbenefits totemporary helpplacements, clearlyapparentinTable4,

wash

outentirelyoverthe firstyear.

As shown

in thebottom panelof Table 5,direct-hireplacementscontinuetohavelargepositiveandsignificantimpacts ondirect-hire earningsand

employment

inthesecond post-assignmentyear, whereas temporary helpplacements have nostatisticallysignificant effect

on

employment

andearningsineitherdirect-hire ortemporaryagency jobs overthishorizon.Thus,thepositive short-term

benefitsof temporaryhelp placements displayed inTable 3 derive entirely fromincreased

employment

in' Thestandard errorsthatweestimateabove cannot simultaneously accountforthe clusteringoferrorsamongparticipants assignedtoacontractorandtheclusteringoferrorsacrosstime withinthesameindividual.

We

evaluatetlieimportanceofserialcorrelationbyestimatingkeymodelsusing only thefirstWorkFirstspellperparticipant.Thesefirst-spellestimates,shownin

Appendi.xTable 1,arecloselycomparabletoourmainmodelsforearningsandemployment

m

Table3.Notably,giventheone-thirdreductioninsamplesize,theslightreductionintheprecisionoftlieestimates indicatesthatdieprecisionof our primary

estimatesisnot substantially affectedbyserialcoirelation.

^"'

Forasmallsetofcases,theindustrycodeismissing fromthe UIdata(thoughwedo measuretotalearningsand employment). Theseobservations are includedintheTable5analysis but theoutcomemeasuresarecodedaszeroforboUidirect-hireand temporary-helpearningsandemployment. Consequently,theTable5point estimatesdonotsumpreciselytothetotalsinTables

3and4. In theWorkFirstadministrative case datausedtocode jobtypesobtained duringthe WorkFirst spell,jobtypes

(temporaryhelp ordirect-hire) are identifiedbyemployernamesin allcases.

thetemporary helpsector;

we

find no evidencethattemporaryagency placements help workers transitiontodirect-hire jobs.

To

furtherexplorethedynamics

of job placementand jobholding,we

alsoexamine

how

jobplacement typeaffects

Work

Firstprogram

recidivism.Using

Work

Firstadministrative data,we

implement

a variant of Equation(2) wherethedependentvariable isan indicator variable equaltooneifaparticipantreturnsto

Work

Firstwithin360

or 720 days ofthecommencement

oftheprior spell.As

shown

inTable 1,36 percentoftheWork

Firstspells resultin welfareprogram

recidivisminMichigan

within oneyearand 51 percent leadtoreentry within

two

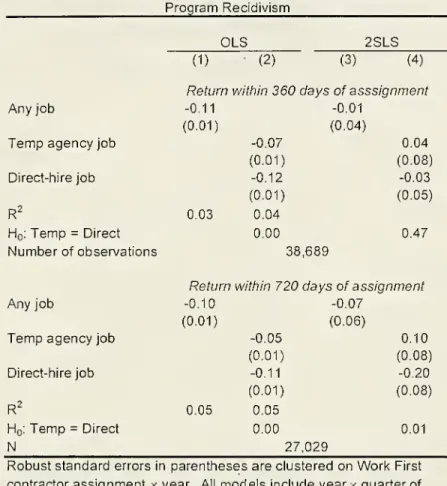

years. Table6shows

thatparticipantswho

obtainjobsduring their

Work

First spells aresubstantially less likelyto recidivatewithin ayearortwo.Those

takingdirect-hirejobs are 12and 11 percentagepoints less likely torecidivate overone andtwo

years,respectively (33 and 22percentlessthan average).

Those

takingtemporaryhelpjobsare7 and5percentage points (19and 10 percent)less likelyto recidivateoverone and

two

years.These

OLS

modelsareunlikelytorevealcausalrelationships.

When we

estimatetherecidivism models usingWork

Firstrandom

assignmentsas instruments forjobattainment,

we

find thatonlydirect-hirejobsreducethe probability ofrecidivism. Point estimatesfortemporary helpjobs are positive, indicating a higher probabilityofrecidivism, but neitheris significant.

However,

we

canreadily reject the nullhypothesis thatthe effectsofdirect-hireand temporaryhelpjobplacements

on

two-year recidivismareequivalent. Thus,consistentwiththefindings pertainingtoemployment

andearnings, only direct-hireplacements appeartohelpparticipantsreduceprogram

recidivism,presumably because theymost likelyto leadtostableemployment."

4.

Bad

jobs

or

bad

contractors?

A

potentialobjectiontothe interpretationofour core resultsisthattheymay

conflatethe effectofcontractor qualitywiththe effect ofjobtype.Imagine, forexample, that

low

qualityWork

Firstcontractors

-

thatis,contractorswho

generally providepoorservices-

placeadisproportionateshareoftheir

randomly

assignedparticipants intemporary helpjobs, perhaps becausethesejobsare easiest tolocate.Also

assume

forthe sakeofargument

thattemporaryhelp jobshavethesame

causal effectonemployment

andearningsasdirect-hirejobs.Under

theseassumptions, our2SLS

estimateswillmisattribute theeffectofreceiving abadcontractorassignmenttothe effectofobtaining atemporaryhelp

job.

Our

causalmodel assumes

that contractorssystematicallyaffect participantoutcomes

onlythroughjob placements, notthrough other qualitydifferentials.

The above

scenario violatesthis assumptionsinceitimpliesthat

ECv.PJ)

< or £(i'„Pf)>

(orboth).We

view

the"bad contractor" scenarioasimprobable.Based on

asurvey ofWork

Firstcontractorsservingthismetropolitan area(Autorand

Houseman

2005),we

document

thatprogram

fundingistightand

few

resources arespenton anythingbutjob development.A

standardizedprogram

ofgeneral or lifeskills trainingis providedinthefirst

week

oftheprogram

atall contractors.After the firstweek,allcontractors focus

on

job placement. Supportservices intendedto aidjobretention, such as childcareandtransportation,areequally availableto participants from allcontractorsandareprovidedoutside the

program. Italso bears

emphasis

that direct-hire and temporaryagency job placementrates arepositivelyand significantlycorrelatedacross contractors, implyingthatcontractors withhigh job placementrates

tendtobe strong

on

both placement margins;this factreducesthe plausibilityofa scenarioinwhich

"bad"

contractorsprimarily place participantsintemp

agency jobs and"good"

contractorsprimarily placeparticipants indirect-hirejobs. Nevertheless,

we

believe thebadcontractorconcern deservesclosescrutinyandso provide

two

formal checks on itbelow.a.

Exploiting

the

12

experiments

togauge

the

consistency

of

the

estimates

A

firsttest isto reestimate ourmain models

separately foreach ofthe 12randomizationdistrictsinour sample.Iftheaggregateresults aredrivenby outlying contractorsoraberrantrandomization districts,

"''

A

keyquestionthatourdatadonot yetallowustoansweriswhetherWorkFirstjobplacementsfosteredbyrandom assignmentsreducestatewelfarepayments.Infuturework,wewillobtain linked welfarepaymentdatafrom the stateof MichigantoanalyzethefiscalimpactsofWorkFirstjob placements.these

models

will revealthis fact.Appendix

Table2apresentsOLS

and2SLS

models

bydistrictforthetwo-way

contrastbetweenemployment

andnon-employment.As

is consistentwiththepooled, districtestimatesin Table 3,eightof12

2SLS

pointestimates forthe effectof job placementson earningsarepositiveandfive arestatistically significant.

Of

thethree negative point estimates, none isstatisticallysignificant(though oneismarginally so). Similarly, 11 of12

2SLS

estimates forthe effects ofjobplacement

on

quarters ofemployment

arepositiveandeightare statisticallysignificant.In

Appendix

Table2b,we

provideestimates forthecontrastbetween

direct-hireemployment,

temporaryhelp

employment and

non-employment. Theseestimates use thesub-sample ofdistricts (7of12)

where

participantswererandomly

assignedamong

threecontractors during atleastsome

part ofthethree-yearsample

window.

The

results,summarized

inFigure 1,provideconsistentsupport forthemain

inferences.In five of seven randomizationdistricts, thepointestimate forthe effectof temporary-help

placements onfour-quarterearningsissubstantially lesspositive (or

more

negative)thanfor direct-hireplacements (byat least$2,000), andthreeofthese fivecontrasts are significant." Similarly, the estimated

effectofdirect-hireplacements

on

four-quarteremployment

exceeds thatof temporary-help placements insix of sevendistricts, andthreeofthese contrasts are statistically significant. Thesedisaggregated

estimates confirm thatour core findings reflect arobustandpervasive feature ofthe data.

b.

A

testof

contractor heterogeneity

As

noted above,asurveyofcontractors failed touncoversystematic differences incontractorpracticesasidefromdifferences intheirjob placementrates. Here,

we

providea formal testoftheexistence ofother differences incontractor practices that affectparticipantoutcomes. Referring to

equation(3),thereduced form versionofour

main

estimating equation,thepresence ofsizablecontractorheterogeneity inearnings or

employment outcomes

(large a^) indicates thatcontractors havesubstantial"'The

correlationbetweencontractor-by-yeartemporaryhelpanddirect-hireplacementratesis0.241 (p=.02).

A

regressionofdirect-hireplacementrateson temporaryhelpplacementrates,yeardummies,anda constant yields a coefficientonthe

temporaryhelpplacementratevariableof 0.389(p=.01).

'Onecountervailing contrast

isalsosignificantat p=.05.

impactson

Work

First participants that are independentoftheirplacement practices.While

notintrinsically a

problem

forour identification strategy, thisfindingwould

suggestthatourstatisticalmodel

focused

on

job placements, providesalimited empirical characterizationofhow

contractors affectparticipantoutcomes.

Moreover,

ifthese other contractoreffectswere

correlatedwithplacementpractices, this

would

causeusto (atleast partly)misattributethe consequences ofother contractorpracticestojob placementpractices.

By

contrast, asmall(or insignificant)value of a^ indicates thatplacementrates foratemporary help, direct-hire,orno jobcapture theentire effect thatcontractors have

on

participantoutcomes.We

testthemagnitude

of al byfirstestimatingequation(3)by

OLS

and retainingtheresiduals.We

next re-estimate Equation(3), replacing

Pa

and Piywithacompletesetofcontractor-by-yeardummies,

alsoretaining the residuals.

We

thentestforthesignificance of o",'by

usingaconventional F-test toevaluate whetherthe unrestrictedmodel, containingthe 59contractor-by-year

dummy

variables,hassignificantly

more

explanatorypower

forparticipantoutcomes

than the restrictedmodel

inwhich

thesedummies

areparameterized using onlytwo

measures.Pa

andPa

.'TheseF-testsyielda surprisingly strong result.For bothparticipant

outcomes

(four-quarterearningsand four-quarter

employment),

we

acceptatthe 16 percent levelorbetterthenull hypothesisthat the59contractor-by-year

dummy

variables have noadditionalexplanatorypower

forparticipantoutcomes

^T

^ Dbeyond

simplemean

contractor-by-yearjobplacementrates,Pa

andPa

.We

therefore canrejectthepossibility thatthere isanysignificant, non-placement-relatedeffect ofcontractors

on

participantoutcomes. This findingdemonstratesthat

we

arenot misattributing the effects ofother contractor"Thereare100contractor-by-yearcellsand 40district-by-year

dummy

variablesplus anintercept.Thisleaves59contractor-by-yeardummiesasinstruments.TheF-testoftheserestrictionsisdistributedF(J-M,N-.I),where

N

isthetotalcountofobservations,Jisthenumberof parametersintheunrestrictedmodel,andJ-Misthenumberof parametersintherestricted

model.

"*By

contrast,whenplacementratesareparameterizedusingasingleplacementmeasurethatdoesnot distinguishbetween

temporaryhelpanddirect-hirejobs(

£

, =7^,+ A,)'''""^F-test rejects thenullatthe7 percentlevel forbothoutcomemeasures.