Accessibility in Museums: Where are we and where are we headed

byShakti Shaligram

B.Tech. Mechanical Engineering

lilT D&M, 2013

Submitted to the Integrated Design and Management Program

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENTAT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 2019

2019 Shakti Shaligram. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper

and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known

or hereafter created.

Signature redacted

Signature of Author:

Shakti Shaligram

Integrated Design and Management Program

May 21, 2019

-Signature

redacted

Certified by:

Maria(I9ng

Professor and MacVicar Faculty Fellow

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by:

Signature redacted

Matthew S. Kressy

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

Executive Director

OF TECHNOLOGY

Integrated Design and Management Program

MITLibraries

77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 http://Iibraries.mit.edu/ask

DISCLAIMER NOTICE

The pagination in this thesis reflects how it was delivered to the

Institute Archives and Special Collections.

Accessibility in Museums : Where are we and where are we headed

by

Shakti Shaligram

Submitted to the Integrated Design and Management Program

on May 21, 2019, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Engineering and Management at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Abstract

This study examines the experience of blind people in science and art museums. It is

important for two reasons. First, museums have the potential to become hotbeds for the

development of inclusive technology and practices. Second, improving the experience for a

small section of society with special needs, blind visitors in this case, can lead to a better

experience for everyone. In the current landscape, museums are already on this path

consciously or unconsciously. At this juncture, the right decisions could lead to a better and

more inclusive future for everyone.

As a first step in this direction, this thesis describes the use of the human centered design

process to identify opportunity areas that can improve the experience universally. The three

key areas were identified through extensive primary and secondary research involving

interviews with key stakeholders and user observation. Major opportunities lie in the areas of

Navigation, Multimodal experiences and Social Inclusion.

These areas not only represent challenges faced by blind visitors, but also key improvement

areas for all visitors. For example, navigation is important for all visitors, but more so for

blind visitors because it represents independence. Current layouts of museums force

otherwise completely independent visitors to depend on external help. Improvements in any

of these areas is very likely to improve the overall experience of museums, while including

an often overlooked segment of the population.

Thesis Supervisor: Maria Yang

Title: Associate Professor and MacVicar Faculty Fellow, Department of Mechanical

Engineering

Acknowledgement

I would first like to thank Dr. Maria Yang, without whom this thesis would not be possible. Her

unwavering support and strong belief in my abilities got me through the darkest days. She's

a role model for many of us not onli because she's a rare world class expert in her field, but

also because she exudes an air of genuine humility, which is rarer.

Next, I would like to thank Matt Kressy and the

IDM

Team for creating this program and

inviting me to be a part of this family. I'm sure that the habits I've built and the perspective

I've gained here will continue to inform my world view for the rest of my life.

This study benefited enormously from the generous contributions made by several

museums and their staff. The primary contributors for this study were the Museum of

Science, Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the MIT Museum, Boston and the

Exploratorium, San Francisco.

Finally, no acknowledgement for my work would be complete without mentioning my

friends and family. It's difficult for me to make a distinction between these two groups, and I

am very grateful for that.

Index

Abstract 3 Acknowledgement 4 Index 5 Preface 7 Chapter 1 9 Introduction 9 Chapter 2 11 Background 11The Social Model of Disability 11

The Machinery driving Inclusion 12

Chapter 3 16 Primary Research 16 Stakeholder Map 16 Lindsay Yazzolino 17 Interviews 17 Chapter 4 23

State of the Art 23

What are museums doing now? 23

Chapter 5 30

Opportunity areas 30

Navigation 30

Multi-modality 31

Social inclusion 33

Chapter 6 - The Accessible Future of Museums and Concluding thoughts 36

Conclusion 49

Preface

This thesis started with a rather simple realization in Prof. Yang's office. If you take away our ability to see, museums with priceless art are just large halls with closed boxes. Imagine yourself in the shoes of a blind person. This sounds almost trivial, but building empathy for a

lack of sight is one of the most difficult things I've done in my life. More on that later. Imagine you are blind and your sighted friends want to visit the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. One of the finest art institutions on the planet that houses untold riches from far corners of the earth. Art that was created by civilizations that in no way benefit from the museum or are even aware of its existence. Truly, a place that belongs to the people. Would you like to guess the number of things in the MFA that can be touched on a regular day?' The answer will not surprise you. The only thing my friend could feel was a roof tile removed from an old Boston building.

One of the core tenets of the Human Centered Design process is building empathy with your user. Arguably the most important one at that. Products build with empathy far outperform those that are built merely with specifications (K6ppen, 2015). This thesis served as an

exercise in empathy for me. After over 15 hours of personal interviews and over 30 hours of direct observation, I feel that I am one step closer to empathizing with my users.

I chose this direction because it combined two of my favorite topics with an enticing goal of

orthogonal canals in our ears that aid balance. The idea that this almost intuitive sense of up and down, and rotation is driven by tubes with a fluid changed my perception of sense organs. I started thinking of them as sensors, much like the ones we use for prototyping. These sensors have their own limits and fail due to incorrect usage. At MIT I learnt how engineers use this knowledge to design safer flight maneuvers for pilots. Of these senses, we often rely entirely on vision. Look around you. Your watch, your phone, your notebook, even this document requires your ability to see. Even to find these things, you "looked." Unless,

you're reading this on a braille tablet, in which case none of this is a surprise to you and I will happily buy you lunch if you tell me your thoughts on my thesis.

I love learning. My friends were once discussing what they looked forward to the most

everyday. Some said food, others said friends while some mentioned their partners. I dodged the question, too ashamed to admit that what I look forward to the most everyday, is what I am going to learn today. What is the tiny piece of knowledge that I will archive in my mind, to be retrieved at the opportune moment or to be cherished for a while before being forgotten. Fast forward 10 years, and the nerd in me has grown more confident and accepting of my reality. If I were religious, and learning was my religion, museums would be my temples.

Chapter 1

Introduction

Museums are protectors of the ideals o society holds, if we're not inclusive it sends a

message to people (differently abled) that this world is not yours but if we are, it tells them that this is a place for you, so is the community and so is the rest of the world.

-Christine Reich, Museum of Science, Boston

Museums are social institutions that shape the ideas and knowledge preserved for the future generations (Janes & Conaty, 2005). What a museum presents as worthy content and who the museum considers to be part of its visiting public communicates a message about what and who are legitimate parts of "normal" society ( Reich, 2014). Hence, museums are critical in the development of inclusionarg techniques and technology. The museum of the future will play a pivotal role in making our societies more inclusive. To draw an analogy, museums will be to architecture and interaction design what Formula 1 racing is to automotive

technology. Improvement in basic automotive technology such as brakes, steering, composite materials and safety have all made their way to road cars. F 1 is the perfect stage for testing this technology as it represents a special case of driving without road regulations and tight budget constraints. Museums can serve as similar test beds for improvements in inclusive technology.

Currently, most museums are not inclusive places for people with disabilities. Studies have found that visitors of all kinds of disabilities report numerous barriers to full participation in museum offerings including the following: the design of the museum's facilities, exhibits, and

programs; untrained or unhelpful staff members; and the absence of disabilities in museum content and collections (Dodd, Hooper-Greenhill, Delin, & Jones, 2006; Landman, Fishburn, Kelly, & Tonkin, 2005; Poria, Reichel, & Brandt, 2009). This continued exclusion cannot be blamed on the lack of regulation or a lack of effort on the part of museum professionals to raise awareness on the issues of inclusion ( Reich, 2014). Countries such as the United States of America, United Kingdom and Australia have legislations mandating the inclusion of people with disabilities in museums, however this legislation is not always followed. For example the International Spy Museum was found to be in violation of section III of the Americans with Disabilities Act since visitors with visual disabilities were not provided full access to the museum's exhibits and programs (Settlement Agreement, 2008).

The current state of affairs is not as bleak as it appears above. Several field wide initiatives are pushing museums towards an accessible future. American Association of Museum's

(AAM)

Everyone's Welcome initiative (AAM, 1998), the Association of Science-Technology Center's (ASTC) Accessible Practices initiative (ASTC, 2000), and the University of Leicester's Rethinking Disability Representation in Museums and Galleries project (Dodd, Sandell, Jolly, & Jones, 2008).

The social model of disability states that people with disabilities participate more when the people who design museums take action to ensure that the experiences they design cater to the special needs of people with disabilities. The tenets of Universal Design state that

making an experience better for one part of the society can lead to a better design for everyone. Looking at inclusion in museums through the lens of social model of disability and

universal design can lead us to a better experience for everyone. Communicating this idea is the purpose of this thesis.

This study employed the human centred design process to find primary needs of blind visitors that will also elevate the museum experience overall. Evidence is presented in the form of literature reviews, interviews and observations. Further, this thesis provides examples that partly address the key opportunity areas and help form a base for future researchers.

Chapter 2

Background

Before getting into the primary research presented in this thesis, it is important to review some background information. This chapter explores two primary themes; 1) the social model of disability and 2) the machinery in place to drive inclusion in museums.

The Social Model of Disability

The feeling of exclusion is intrinsic to the experience of living with disabilities. Knowingly or unknowingly, the rest of society has created barriers that stop people with disabilities from participating in an equitable manner. This exclusion is visible through data about lower rates of employment and higher rates of poverty in the disabled population ( Waldrop & Stern,

2003).

Scholars posit that this exclusion results from society's response to human differences which results in designs, processes, systems and practices that are based on unstated

assumptions of what it means to be "normal" ( Reich, 2014). The notion that community

and societal inclusion stems from changes within societal institutions rather than changes to characteristics of individuals is called the social model of disability (Barnes, 1998; Shakespeare, 2010). This model differs from the medical model which defines a

disability as a medical defect that must be treated or fixed (Reich, 2014). Disability studies scholars argue that the medical model leads to "ableism" while categorizing persons with

disabilities as the "other". The social model in contrast places the responsibility of change within the society.

The social model of disability has implications on the way society thinks about and defines education for people with disability. The very idea of special education is said to reside in medical assumptions of disability and we need to move away from the deficit framework where the barrier learning is said to reside in the student (Skrtic, 1991). Reich et al. articulate inclusion in museums as follows:

Inclusion in [informal science education] goes further than ensuring that people with disabilities can enter the buildings or use the exhibits,

programs, and technologies that deliver such experiences. It also requires that people with disabilities are able to learn from such experiences and participate as a part of, and not separate from, the

larger social group and community.

The Machinery driving Inclusion

This section is designed to give the reader an understanding of the policy landscape that is driving and guiding most of the work in museum accessibility. Members of this landscape exist at different scales and this section lists them in an increasing order of specificity.

Policies made at a national scale and ideologies such as Universal Design form the top layer which further guides government initiatives and finally the museums themselves.

a. ADA (National Policy)

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) became law in 1990 (What is ADA, 2019). The ADA is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public. The purpose of the law is to make sure that people with disabilities have the same rights and opportunities as everyone else. The ADA gives civil rights protections to individuals with disabilities similar to those provided to individuals on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, age, and religion. It guarantees equal

opportunity for individuals with disabilities in public accommodations, employment, transportation, state and local government services, and telecommunications. The ADA is divided into five titles (or sections) that relate to different areas of public life.

In 2008, the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act (ADAAA) was signed into law and became effective on January 1, 2009. The ADAAA made a number of significant changes to the definition of "disability." The changes in the definition of disability in the

ADAAA apply to all titles of the ADA, including Title I (employment practices of private

employers with 15 or more employees, state and local governments, employment agencies, labor unions, agents of the employer and joint management labor committees); Title II (programs and activities of state and local government entities); and Title Ill (private entities that are considered places of public accommodation).

Topics explored in this thesis fall largely under Title Ill that prohibits private places of public accommodation from discriminating against individuals with disabilities. Examples of public

accommodations include privately-owned, leased or operated facilities like hotels, restaurants, retail merchants, doctor's offices, golf courses, private schools, day care

centers, health clubs, sports stadiums, movie theaters, and so on. This title sets the minimum standards for accessibility for alterations and new construction of facilities. It also requires

public accommodations to remove barriers in existing buildings where it is easy to do so without much difficulty or expense. This title directs businesses to make "reasonable

modifications" to their usual wags of doing things when serving people with disabilities. It also requires that they take steps necessary to communicate effectively with customers with vision, hearing, and speech disabilities. This title is regulated and enforced by the U.S.

Department of Justice.

b. Universal Design

Universal Design is the design of objects, buildings or environments to make them

accessible to all people regardless of age, disability or other factors. The exact definition of universal design tends to be re-appropriated by institutions depending on their particular usage. For example the Museum of Science uses the following definition in its Universal Design plan:

The design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design

Principle 1: Equitable Use Principle 2: Flexibility in Use

Principle 3: Simple and Intuitive Use Principle 4: Perceptible Information Principle 5: Tolerance for Error Principle 6: Low Physical Effort

Principle 7: Size and Space for Approach and Use

The interested reader may follow the references to gain a better understanding of these principles. The rest of this report does not make specific mentions of these principles, so they are not necessary to understand this text. Another offshoot of Universal Design is the Universal Design for Learning. The core philosophy behind UDL is represented in the image below:

CAST Until learning has no limits

I

Provide options for Provide options for

Recruiting Interest Perception

Provide options for

Sustaining Effort & Persistence

Provide options for Self Regulation

Provide options for Language & Symbols

Provide options for

Comprehension

* '0lcasre trwr~i ii n

Provide options for

Physical Action

Provide optioni for

Expression & Communication

Prov'ode op ions for

Executive Functions

'I

'UExpert learners who are...

Purposeful & MotAivatedARes Prcefu & Keab veso oe.- kn0& MA Aoi.

sgUWewde~am~se~r I r 4 AS' T. i 20t 16 |sg Crazon: CASTH0 urv.Va; <desqgn foe wwmirwg Z-ge es vwon 2.2 tgrap4,i a:Vnzez,- Wiketmid. PI:. Aoa

Figure 1: The guidelines for UDL as described by the Center for Applied Special Technology

(CAST, 2019)

c. InformalScience.org

InformalScience.org

is a website run by the Center for Advancement of Informal Science

Education(CAISE) . CAISE works in cooperation with the National Science Foundation's

(NSF's) Advancing Informal STEM Learning (AISL) program to build and advance the

informal STEM education field. We do this by providing infrastructure, resources, and

connectivity for educators, researchers, evaluators, and other interested stakeholders

(CAISE, 2019).

CAISE is one of six resource centers funded by the NSF's Division of Research on Learning in

Formal and Informal Settings (DRL) within the Education and Human Resources (EHR) directorate that support and connect principal investigators and their projects.

At our website, InformalScience.org, you will find over 8,000 resources, including project descriptions, research literature, evaluation reports, and other documents related to quality, evidence-based informal STEM learning work supported by a diversity of federal, local, and

private funders.

CAISE also convenes task forces, inquiry groups, convenings, and principal investigator

meetings that are designed to facilitate discussion and identify needs and opportunities for those who design for, research, or evaluate informal STEM learning experiences and settings. These settings include:

Botanical gardens and nature centers

Cyberlearning and gaming community

Events and festivals

Making and tinkering spaces Media (TV, radio, film, social) Parks

Public libraries

Science centers and museums Youth and community programs Zoos and aquariums

Chapter 3

Primary Research

a. Stakeholder Map

Votes -Visitors Inclusive T.... Policy Blind People LLKnow edge Testing

Policy .4.... .... ...

~

-.Muem Project MuseumsI " _ M ke r --... --- --- ---- ------ Makrs;Incentive - PrIetmIproved Methods Researchers Donors E EC-L ... .... Donations Universities LegacyFigure 2: A stakeholder map for this study

A stakeholder map describes the relationships between entities that directly or indirectly

affect a "project." The "project" in this case is the examination of the experience of blind visitors in museums. Stakeholder maps are living documents and they are designed to

evolve with the project. Often they represent hypotheses that are tested and updated over time. Additionally, stakeholder maps are useful to identify incentives that may be driving the actions of entities.

The stakeholder map above shows how this thesis is affected by various stakeholders. Note that some stakeholders do not directly affect the research, but instead affect other entities. This research was restricted to direct stakeholders only. Future researchers are encouraged to reach out to stage two stakeholders such as Donors for a different perspective. If nobody wants to fund museums, accessibility would be out of the question. Hence, it is important to

understand what the donors feel about accessibility as well.

b. Lindsay Yazzolino

Lindsay is an accessibility consultant in Boston. She's worked on countless accessibility projects and currently consults for leading companies such as Touchgraphics and InsideOne. She also happens to be blind. Interacting with Lindsay is an inspiring and mesmerizing experience. Lindsay is adept at tasks that may be considered difficult for a blind person. The author recalls how he's never seen a typo in her text messages and she types with perfect punctuation, every time. She types with this accuracy at a blazing fast

speed.

Lindsay was instrumental in the research for this thesis. She agreed to meet with the author for several hours for one-on-one interviews and many trips to museums in Boston. She is a lead user for most assistive devices aimed at blind people.

c. Interviews

Primary research forms the bedrock of this report. This exercise produced over 30 hours of personal interviews, along with several hours of close quarter observations. The findings from this research are listed below with short bios of the personnelle involved. The list below

includes some stalwarts in museum accessibility such as Christine Reich and Karen

Wilkinson. Museums were a rich source of information, but it was important to reach out to several stakeholders to ensure a holistic understanding of the field. Hence, this list also

includes representation from the Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education

(CAISE). CAISE is one of six centers funded by the National Science Foundation to build and

advance the informal STEM education field (About CA/SE, 2019).

i. Participant A

Participant A is a director at a large science museum facility in Massachusetts.

Participant A gave us an overview of her experience with museums and accessibility which started with her mentor, Dr. Betty Davidson. She recalled one of the first times she witnessed applied universal design. It was for an exhibit at the Museum of Science that was meant to receive an accessibility upgrade. An external researcher evaluated the exhibit for learning outcomes and found a 40-50% increase in the number of visitors reporting a thorough understanding of the exhibit ( Davidson, 1990). This research laid the foundation for universal design in museums. Participant A also highlighted some of the formative studies that led to her engagement with universal design.

ii. Participant B

Participant B is a director at a university museum in Massachusetts.

In 2017, he announced plans for the institute museum in a press release. The colossal structure on Xstreet nome will also house the new museum. In essence, the museum is onlIg changing its location but according to Participant A this is also an opportunity to make some ideological changes. He said " This is the big opportunity for the institute Museum to be something like what the institute and the public deserve", while adding "In our new location, we can anchor and mediate the institute's relationship with the wider community (School of Humanities, 2019)." CuriouslI, this press release did not mention inclusion or any steps towards improving accessibility in the museum. The museum staff widely

acknowledges and understands that the institute museum has a long way to go towards becoming a truly inclusive institution. Recent steps in that direction include the creation of an Accessibilitg Task Force that meets regularly to identify avenues of improvement.

Participant B is an incredible raconteur and communicated through a great collection of stories. He recalled a story about a researcher named Richard Gregory who found the

relationship between learning and physical interaction with the world. Gregory's findings were based on were based on experiments with a subject that was born blind but gained vision in his middle age. This research was instrumental in the creation of the Exploratorium

and science centers across the world (Lazar, 1964). He proceeded to make an intriguing analogy between the state of advanced science and the experience of blind people in the world. Currenty, advanced science is based on phenomenon that is not visual, but the

representations we use tend to be visual. Another interesting highlight was his account of the history of science museums. Museums started as research institutions but over time they shifted to an objective of education for K-12.

iii. Participant C

Participant C is an accessibility expert at an arts museum in Massachusetts

Participant C described the accessibility measures that are in place to help blind visitors at the museum. When the art museum encounters a group of students and one of them has a disability, they encourage the group to move together and instead add trained museum personnelle to the group to assist the visitor. She also recalled how they had used RFID in the museum, but the intervention achieved limited success because of technical difficulties. This mixed experience with technology was echoed in her recollection of most technological

interventions. She also mentioned how navigation is one of the primary needs of visitors to the museum, especially for a museum the size of the art museum. We also discussed how the experience of discovery is an essential part of the museum experience. "People power" is the immediate solution for a lot of the accessibility needs of the museum. Her experience with people who have low vision have taught her how even people with accessibility needs

exist on a spectrum of preferences and tastes. This is important to remember when designing anything for accessibility, especially for people who don't personally experience the problem they are addressing.

iv. Participant D

Participant D is the director of an interactive program at a major California science museum for children.

D admitted how designing for accessibility is a formidable challenge, especially when

describing phenomenon that is counterintuitive or complex. The children's museum does not use a concrete framework for designing accessible interactions. Instead, they rely on an experimental approach where every exhibit is tested and evaluated. She recalled some of the most successful exhibits at the children's museum all of which included a multi modal interaction. An interesting anecdote mentioned how an exhibit called the musical bench was managed by custodian staff that are deaf. They still enjoy the vibrations from the exhibit and relish their experience with the setup. She was however reluctant to classify exhibits that were less successful from an accessibility perspective. An understandable omission as the exhibit designers are her colleagues. She stressed on the deeply rooted philosophy of testing prototypes at the children's museum.

v. Participant E

Participant E is a director for visitor research at a major California science museum for children.

E discussed some of the accessible interventions in place at the children's museum. Labels at

the museum have a QR code which can take visitors to the same label in different

languages. He also spoke about the characteristics of a good interactive experience. A good exhibit takes very little effort to begin. They are usually understand and invite visitors

through easy to implement first tasks. The aspect that elevates this experience is the depth in interaction. Apart from being easy to start, a great exhibit also leads the participant on a path of inquiry that can be guided in multiple directions. This philosophy is reflected in a

book published by the exploratorium about a framework called Active Prolonged

Engagement ( Humphrey, 2017). As the director of visitor research and evaluation he gave us an account of how exhibits are evaluated. Not surprisingly, they use quantitative and qualitative methods, most of which covered in detail in the book on APE. One of the

highlights was his perception of differences between schools and museums. He believes that one of the key differences is that museums primarily impart positive experiences.

vi. Participant F - CAISE

Participant F is a Project Director for the Center of Advancement for Informal Science Education. He also worked at the Exploratorium as an explainer. He recalls how a visit to the Exploratorium had a lasting effect on his life and changed the trajectory of his career. His experience extended to the emergence of accessibility at the exploratorium. Initially, the exploratorium was heavily biased towards oculocentric experiences and the tactile exhibits were restricted to a small section. His perception of great interactive exhibits rested on representing discrepant events or evokes surprise. As a valuable contrast, he recalled exhibits that failed to evoke a similar reaction because they were "dry" in the experience. "Black box" exhibits, boxes where visitors put their hands into a box to feel objects, were particularly high on this list. This is similar to the APE philosophy mentioned by Participant E.

vii. Participant G

Participant G is the owner of an accessibility tech firm, a company he started 20 years ago. He started his career as an architect and switched to this space after designing a tactile map for the New York City subway system.

One of the biggest challenges when designing interactive maps for the museum was accounting for the wide range of visitors. He contrasted this experience with designing something for a targeted audience such as children of a certain school level. Another aspect that is essential is ensuring their designs are usable by the mainstream audience. Often designers get lost in the weeds with accessibility and end up creating experiences that ignore the majority of people, who may not have a disability. He gave specific examples of how human centred design was incorporated into their designs. For example they built an interactive model of a rocket that would provide audio feedback when a blind person pointed towards a specific part. The exhibit functions in two states; exploration and investigation. If the model was touched by two hands, the model knows that it's being touched to feel the shape. The model does not react with audio feedback in this case.

Instead, the model only provides audio feedback when only one of the parts is being touched. He also included a political commentary, suggesting that the current

administration is not creating external pressure on institutions; something that was initiated

Chapter 4

State of the Art

The goal of this study is to identify opportunities for improvements in museum accessibility and then propose measures to address the same. But before delving into the opportunities,

it's important to understand the current state of affairs in museums. Of course, not all museums are created. This is especially true for museums in the developing world. In its current scope, this study only examines museums in the developed world ( US, Europe and

Japan).

The author's personal experience with museums in India are reminders of the vast chasm that exists between rich museums in the west and the resource starved institutions that

serve the citizens in the sub-continent. Many museums fail to provide engagement to even the most able visitors.

What are museums doing now?

This section describes the current measures adopted by museums across. What follows below is not an exhaustive description of all efforts across the globe, but it captures the scope of efforts at different levels. These levels are broadly defined as Ideology level, organization level and technology level.

Ideology Level

According to a poll, majority of science museum professionals feel that less than half of their exhibits are accessible to people with a wide range of disabilities (Tokar, 2004). Further,

a survey of all US museums found that less than 25% have accessibility plans relating to technology (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2006). These surveys relied on self-reported estimates of inclusion. Hence, even though these numbers seem low, they are likely to be overestimates( Reich, 2014).

A study of museums in the US and UK found discrepancies between whether an institution

felt it was accessible to people with disabilities and the actual policies, access or practices that were in place(Walters, 2009). Furthermore, a report by CAISE suggested that only a handful of museums are responsible for the majority of inclusive programs and exhibits created by science museums (Reich, Price, Rubin, & Steiner, 2010). A small group of institutions producing a majority of the developments may not be surprising to readers familiar with the pareto rule. However, this is also a symptom of excluding accessibility at an ideology level.

One of the institutions that includes accessibility at an ideology level is the Museum of Science in Boston. This section reviews measures the MoS has taken towards universal design.

Universal Design in MoS

Like many other institutions, MoS employs Universal Design to reach the widest possible audience (MoS.org, 2019). They define Unversal Design as follows:

The design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.

The UD manifesto at the museum has a short section dedicated to the ideological

framework. It lists the following three key areas to promote inclusion in a holistic manner. The following areas describe learning opportunities that are accessible to a wide range of visitors.ldeally, most visitors can:

Physically interact with/perceive the space

Is the environment inclusive so that a diversity of individuals can physically interact with/relate to the space? In other words, is the space set up so that a diversity of individuals can move around the space comfortably and safely? Is the information in the space conveyed in a variety of formats so that a diversity of individuals can perceive it? Can a diversity of individuals manipulate or cause things to happen within in the space?

Cognitively engage with the materials

Is the environment inclusive so that a diversity of individuals can cognitively engage with the materials? In other words, is the information conveyed using a range of media to allow a diversity of individuals with a range of learning styles to engage with the materials? Do the materials take into account a diversity of individuals with a range of learning and cognitive skills? Do the materials take into account a diversity of individuals with range of experiences and sets of background knowledge?

Socially interact with one another

Is the environment inclusive so that all individuals can socially interact with/relate to one another? In other words, is the environment generally safe and welcoming for a diversity of individuals? Is the space set up to comfortably and safely foster and facilitate encounters and engagement among a diversity of individuals? Are the materials designed to provide meaningful reasons to foster and facilitate encounters and engagement among a diversity of individuals? To ensure the physical accessibility of the exhibition and the Museum's adherence to its legal requirements, the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design will be followed.

Figure 4: An excerpt from the UD report created by the MoS Boston.

Each key idea is followed by questions aimed at exhibit designers. Asking themselves these questions is supposed to guide them towards a more equitable vision for the museum. The inclusion of questions, instead of a framework suggests that universal design in this case works as a mechanism that corrects the path instead of something that guides the designer towards a universal design. The rest of the report contains helpful objective guidelines for designers to follow when designing the exhibits or the exhibition space.

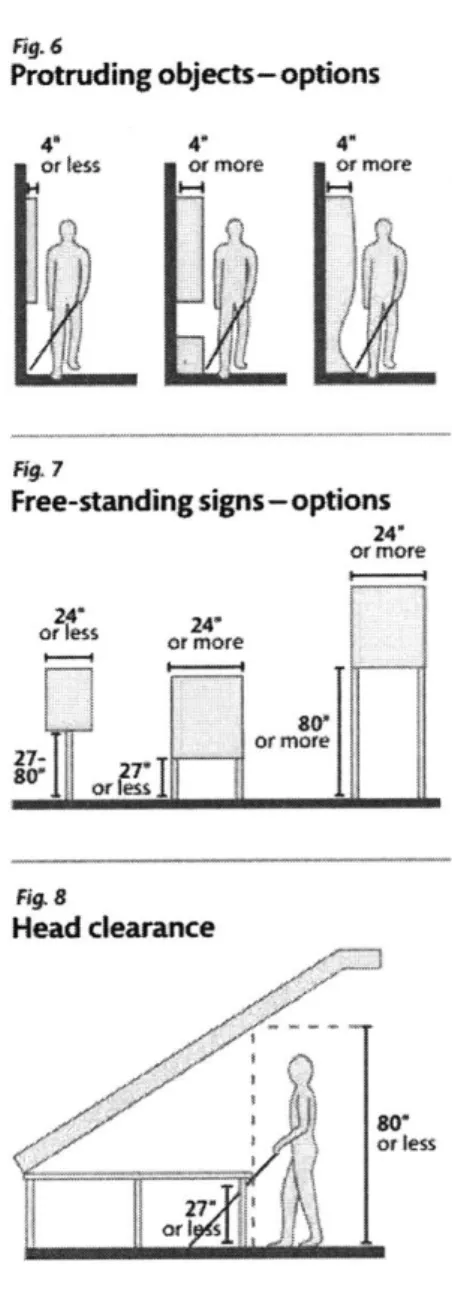

Fiq. 6

Protruding objects-options

4* 4*

or Its or more or more

~L

L

Rg 7

Free-standing signs - options

24" or more 24' 4 or less or or ir i or mo e 800* or mor Head clearance or ess orL

Figure 5: A few of the objective guidelines listed in the report.

The report contains extensive diagrams and figures towards measurements, however lists a peculiar omission when it comes to the idea generation phase.

Idea Development phase

No specific UD to-dos, checkpoints or deliverables

Concept Development

* The exhibit team will brainstorm multi-sensory concepts and interactive ideas * Develop project-specific draft of Universal Design Plan

* Eliminate unrealistic concepts (based on space, time, budget, safety, maintenance, and accessibility) * Deliverable: Universal Design Plan for project

* Approvals: Universal Design for Exhibits Committee (UDEC) reviews and approves UD Plan

Design & Prototyping Phase: Story Testing

* Conduct visitor evaluations of Stage 1 prototypes for visitor learning and engagement and for usability of component

* Exhibit design team will develop potential logos, typefaces, and graphic treatments, which will have

a UD review

* Eliminate unrealistic concepts (based on space, time, budget, safety, maintenance, and accessibility)

Figure 6 : Strangely, the Idea Development Phase contains no to-do, checkpoints or

deliverables.

This omission is in line with statements made during the interview with Christine Reich.

Inducting inclusive policies at an ideological level is difficult. However, the report includes

bullet points for evaluators, which has some traces of ideological guidance.

Evaluation

(Evaluator)

Have a broad range of users been included in evaluating exhibit concepts

and prototypes throughout the exhibit development process?

* During Concept Development phase, the exhibit team will consider

whether inicuding people with disabilities in early formative

evaluation, such as focus groups, would be pertinent.

* Conduct evaluations of Stage 2 prototypes with people with a

wide range of abilities and disabilities for usability, learning, and

engagement. Ideally, test a cluster of prototypes rather than single

components.

* The exhibition team will ensure that the component adheres to the

UD requirements for exhibition design to the greatest extent possible,

as stated in the above section, when this evaluation takes place.

* Evaluators will recruit people with a range of disabilities-e.g,

sensory, physical, cognitive disabilities-for evaluation.

* Evaluators will use think-aloud protocols or other usability testing

methods to identify potential barriers to inclusion, in addition to

general formative evaluation interview.

Figure 7: Some of the guidelines for evaluators.

The addition of a framework at the ideology level may be compensated by a few measures.

The tenets of Universal Design account for inclusion and a reasonable practitioner of the

process would keep this in mind. Another measure commonly employed is hiring personnelle

with disabilities to help make the institution more inclusive. This is practiced by leading

museums across the world. The MoS also has visually impaired members in the team that

actively participate in the development process for exhibits. Similarly, Japan's National

Museum of Ethnology employs Hirose K. who organizes frequent touch based exhibitions.

Hirose lost his sight at the age of thirteen and now works at the museum to improve the experience of all visitors to the museum. An exhibit he organized was titled "Touch the world

: Widen your perspective" which invited viewers to touch artefacts. Phrases such as the ones listed below, guided the visitors through the exhibit (Hirose, 2013):

Stop and touch:

Have a conversation with an artifact. Touch it, hold it, take your time, observe its form and texture. Handle it gently and think about the people who made it, their culture and society. This is where touching the world begins.

Look and touch

As you read the explanations, feel free to use both hands and eyes to explore the overall form, structure of the details, the relationship of inside and outside. think about the materials used and how the object was made.

Don't look, just touch

What can you learn about form and details by touch? Try it. Investigate the difference between the senses of touch, sight, and hearing.

Hirose conceded that less than 1% of the visitors to the museum were visually impaired, but his exhibit improved the experience for all the visitors coming to the museum. Such change comes through only with an ideological shift in planning for museums.

Similarly, the Victoria and Albert museum in London employs Barry Ginley, a visually impaired consultant who has made significant changes to the inclusion policies at the museum. She describes how changes at an organizational level led to her hiring as the museum's first Disability and Access Officer (Ginley B. 2013). One of the more recent

changes by the Project Team was including her in the design process. She says " It is too late when your half way through a project to make changes as it becomes difficult to alter designs and becomes more costly. Since we have taken this approach, I feel access is more integrated and "we often get it right, more than we get it wrong"."

The examples above are meant to indicate the importance of including accessibility at an ideological level for true change. This could be achieved by instituting policy that forces exhibit designers to think about accessibility and by hiring team members that have

accessibility requirements themselves. The next section describes some of the opportunities that were identified through primary and secondary research. Once an organization

overcomes the hurdle of including accessibility at the strategy level, the needs in the next section can guide them towards more objective goals.

Chapter 5

Opportunity areas

The following section contains opportunities identified through primary and secondary

research. Besides improvement areas for museums, this section also suggests

characteristics of possible solutions. These characteristics are based on need of VIPs

(Visually Impaired Persons) identified during the course of this research.

Navigation

Navigation in large museums is a great opportunity for universal design. It's a problem

faced by all visitors, able or otherwise. Of course, this problem is exacerbated for visually

impaired people. In the current layout for nearly all buildings, navigation is guided purely by

visual aids. It's important to note a stark distinction between navigating indoors and

outdoors. Outdoor navigation has been the object of countless technological innovation. We

can not only localize (GPS) but also change our position using mobile phones ( uber).

However, indoor navigation is still untouched by such aids. Many efforts exist in research

labs, but they are yet to make an appearance on the mainstream stage (Meliones, A., &

Sampson, D., 2018). Google maps has started including maps for public buildings such as

malls but this information is scarce and not accessible to the visually impaired. Navigation is

essential for a number of reasons, listed below.

Independence

Many museums claim to include accessible exhibits. Many do. Universal Design

guidelines are strictly adhered when they're designing spaces. But, can a blind person

walk into a museum, unaccompanied and experience all these accessible exhibits?

This creates a factor of dependence. A visually impaired person who is completely

independent in all other spheres of life should not be made to feel dependent to

experience a museum. Accessibility must extend from discovery, i.e. finding out about

a museum, to post engagement which is interaction with the museum even after

leaving the compound. This may sound idealistic, but if we are striving for an

accessible future, why not strive for one that is completely accessible?

Safety

Museums are large, confusing structures that are full of people. When designing, it is

also important to consider fringe cases, which in this case would be emergencies. An

important aspect of any system that enables VIPs to navigate a museum, must also

account for emergencies. Of course, this could also be combined with a service

component. For example, locations of all visitors that may require assistance could

be anonymously tracked through a central server. In case of an emergency,

personnelle could be assigned to find and assist them to safety.

Multi-modality

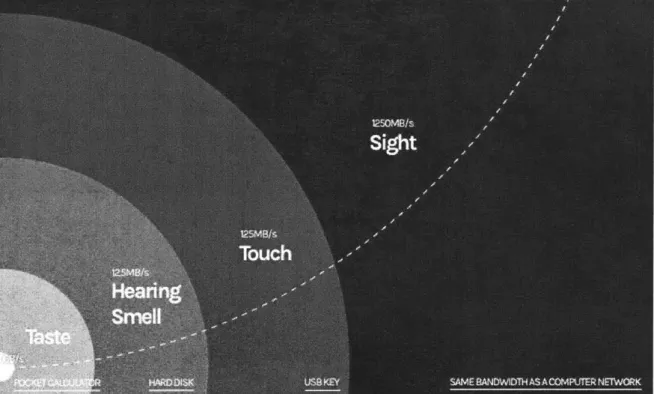

Figure 8: Rate of data transfer for different senses created by Tor Norretranders (Data

Visualization, 2079).

Tor N0rretranders created the visualization above to show varying rates of data transfer for different human senses. The numbers above, although apocryphal, signify a much deeper rooted dependency. We are physical beings and we communicate with each other through multiple modalities. The bandwidth for inter-human communication is incredibly high because even the most subtle differences in behaviour, tone, body language signify something. However, when it comes to the built world around us, we rely almost entirely on visual stimuli.

Perception

Stages

1

Workingm Responding and Cogniition Verbal Vocal vl\Respons

Visual Spatial Manual

Modalities

Auditory

VI\

Verbal

Cod

Spatial

Figure 8: The Wickens model for human information processing (White, 2018).

The Wickens model for human information processing provides a clearer understanding of

how the human body interprets information. From Tor's image, one may begin to believe

that sight is the fastest of all human senses hence relying on that will lead to efficient

communication. While the Wickens model tells us that information is processed through

various channels that can run in parallel. And it is easy for one of these senses to get

overwhelmed. Hence, a multi modal is more resilient and can be even more efficient if

designed correctly.

es

The case for multimodal exhibits is a strong one and it continued in the next chapter. This is

already understood well by exhibit designers and planners and many new exhibits now

include multiple modes of communication. Formally including models such as the one made

by Wickens is essential for a universally designed experience.

Social inclusion

Fiona Candlin interviewed blind people to study their exclusion from museums and their

responses towards projects that aim to remedy that marginalisation. She found that

responses to her queries were highly polarized; respondents were either highly critical or

very enthusiastic. She later posits that this high level of satisfaction had little to do with

museum provision and more the result of social interaction and rare inclusion (Candlin, F.,

2003). The importance of social inclusion should not be surprising, but out of the museums

studied for this paper, none had any programs geared towards the inclusion of blind people.

One may argue that the footfall for blind people is so low that such a program would no be

sustainable. That is but a chicken and egg problem. Without the creation of such programs,

blind people would not feel welcome in museums.

A study of the interaction between sighted guides and VIPs (Vom Lehn, D., 2010) revealed

some interesting insight about current measures for accessibility. The study says:

"The analysis suggests that the mere provision of

interpretive

resources like labels,

tangible objects, and guides is insufficient to achieve social inclusion in exhibitions.

Social

inclusion

in museums is a practical achievement. It requires practical actions

by the visitors (and guides), actions through which they use interpretive and other

resources to make sense of the exhibits. These actions

include

looking at exhibits,

tactile actions across the surface of exhibits, verbal descriptions of exhibits and their

features, and so on. They are organised in interaction between the sighted and

visually impaired participants. They closely monitor each other's actions and align

their actions with each other, thus progressively producing a shared experience of

the object they are jointly facing."

Further, the study also sags that this interaction was beneficial in both directions:

"The analysis of the video recordings discussed here suggests that VIPs are not passively following the guidance of their sighted companions, but, indeed, their experience and descriptions of the exhibits also enhance the experience of the sighted guides. In this sense,

then, the VIPs provide the guides with resources to make sense of the exhibits. Thus the notion of the '(sighted) guide' that implies a power imbalance between the guide and the guided is challenged and emphasis is put on the interactional achievement of social inclusion. "

The figure below lists the findings of a study ( Bookstore, 2019) aimed at identifying preferences of visually impaired people towards games. Needs 3 and 5 point towards a sense of inclusion with sighted people.

Recommendations The universal design approach should be fully incorporated into the process of developing games for visually impaired young adults.

Visually impaired young adults enjoy A "tolerance for error" should be allowed when visually competition and prefer to receive impaired players try to immerse themselves in interactive immediate feedback. games. Users may try again when they are notified that they

have made a wrong decision. Game designs that incorporate tolerance can maximise the play value and provide an immediate response to the player.

Games should allow visually Designers should provide enough "size and space for impaired young adults to move approach and use" to enable all players to engage in trial and around with as much freedom as error regardless of their visual ability.

possible.

Games should provide opportunities Game should provide "equitable use" and be marketable to for VIPs to gain the trust of fully people with diverse abilities. With respect to equity, the sighted people and collaborate with games should enable people to participate together without

them. experiencing social stigma.

Indicators and markings on the game Game should be designed with "perceptible information" to should comply with the international provide players with enough information. For example, an standards to avoid confusion. improved tactile feeling maximising the "legibility" of the standardised game control buttons is crucial for avoiding any confusion during the playing process.

Visually impaired young adults Facilitating "simple and intuitive use" can enhance the pursue multisensory feedback multisensory experiences of players and minimise the

through the senses of touch and possibility of errors occurring during the playing process. If smell, and locating the

right

position not, the gamesmay

create unnecessary hurdles that VIPsfor "seeing." need to overcome.

Games should promote the concept The design process should incorporate "flexibility in use" of sharing with all people. such that all tangible objects accommodate left-handed or right-handed access and provide options for meeting a wide range of individual preferences, including those of VIPs. Games should require less time and "Low physical effort" can be particularly beneficial to VIPs effort to set up. because they require more time to set up the games and to

put the pieces back in the original position than fully sighted people. If the setting-up process repeatedly consumes a lot of energy, players may be reluctant to play games.

Figure 9: Preferences of blind people towards interactive games ( Bookstore, 2019)

Social inclusion is just as important as the objective guidelines laid out by universal design. To create a truly inclusive space, people with disabilities will also have to included socially.

Chapter 6

The Accessible Future of Museums

and

Concluding thoughts

This chapter seeks to point a picture of the museums of the future. We start with a clean slate and examine the vision for a universal museum. Further, we evaluate whether a museum even needs to exist for the blind and if we could achieve all of this digitally. Finally, we examine a few solutions to some of the opportunities identified in chapter 4.

The need for physical spaces

When talking about the museums of the future, the virtual or digital museum is a common trope. Maybe in the future the museums will exist only on the internet. This may seem like a

dystopia or a utopia, depending on the reader's inclination. On the face of it, a purely digital experience with museums sounds like a good idea for making museums accessible to blind people. It tackles the tricky job of making an entire space accessible, as discussed in chapter 4. Further, creating a digital experience in a controlled environment could be easier

compared to the chaotic galleries of a museum. Well, then should museums invest only in digital spaces for the future? If blind people cannot see the artwork, then why would they need to come to a museum to experience it through some other medium? Why not take the medium to them?

These are important questions and any museum investing in accessibility must have good answers to these questions. Judging from research, for blind people proximity to art is at

least as important as learning about it (Hayhoe .2013). This should not be surprising as the same argument could be made for sighted people. Why do people go to museums when most things are available on the internet? Our traditional understanding of museums only affords a visual perception, with little opportunity for other forms of engagement. Gombrich articulates this as follows in his description of the economy of vision:

art educators sometimes try to make us feel guilty for our failure to use our eyes and to pay attention to the riches spread out before us. No doubt they are occasionally right, but their structures do little justice to the difference between seeing, looking, attending and reading, on which all art must rely.

Hayhoe in 2013 studied blind people through extensive interviews and observation and presented some interesting observations. Firstly, he found that an individual's experience with art evolved with deterioration in eyesight, and the level of physical blindness was not a predictor of visual arts or the development of a cultural identity. For individuals represented in his case study, merely standing in the building that houses major works of art provides a significant symbol of identity beyond the learning of the artifacts' structure and meaning. Therefore, even with advancements in technology, ensuring the interaction of blind people within the space of the museum is likely to remain critical.

What is a universal museum?

A museum that is built on the principles of universal design it ought to be called a universal

museum. However, the term Universal Museum is mired in controversy. The dispute stems from a declaration issued in 2002 called the Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums (ICOM, 2004). This document was signed by directors of 40 of the

world's foremost institutions. Although this is not directly related to the content in this study,

it's important to note how the term Universal Museum has probably been lost for a long

time. The declaration was issued primarily in response to the pressure Great Britain faced

from Greece concerning the Elgin Marbles, in addition to other other repatriation claims

against museums throughout the world. This study is not concerned with the political

motivations behind this declaration. However, it is largely ( Opoku, 2013) believed to be a

piece of propaganda to protect the art in museums that was acquired through means that

are deemed unfair. The first two paragraphs of the declaration are included below for

reference, while the whole document can be found at the source (ICOM, 2004).

Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums

The international museum community shares the conviction that illegal traffic in archaeological, artistic, and ethnic objects must be firmly discouraged. We should, however, recognize that objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values, reflective of that earlier era. The objects and monumental works that were installed decades and even centuries ago in museums throughout Europe and America were acquired under conditions that are not comparable with current ones.Over time, objects so acquired-whether by purchase, gift, or partage-have become part of the museums that have cared for them, and by extension part of the heritage of the nations which house them. Today we are especially sensitive to the subject of a work's original context, but we should not lose sight of the fact that museums too provide a valid and valuable context for objects that were long ago displaced from their original source.

Figure 10: The first two paragraphs of DIVUM

Even though the the declaration above does not relate to universal design or accessibility, it

would be difficult to disassociate the term "Universal Museum" from this event. Future

researchers are encouraged to investigate this further and understand the relationships

between the term "Universal Museum" and universal design. For now, it seems like this

nomenclature may be lost to the community. This is not unlike the loss of the word

Astrology to horoscope study, while scientists studying stars have to be content with being called star-namers (astronomers) instead. C'est la vie.

A truly accessible museum of the future will have to address the opportunities listed in

chapter four. They represent the biggest challenges facing the blind community from participating in museums. Presented below are possible solutions to the three opportunities. These are meant to be starting points for future researchers and only meant to be

representative of the current directions explored in this space.

Navigation solutions

Tactile Map based

A tactile map is the most obvious step towards making spaces more navigable. Companies

such as Touch Graphics (interviewed in Chapter three) aim to refine and commercialize tactile technology for use in public spaces. Shown below is one of their tablets in use at the shedd aquarium.

A1

Figure 11: Steve Landau from Touch Graphics next to one of the tactile maps at the Shedd Aquarium

Touch graphics uses a combination of physical and digital methods to make their maps accessible. Their most common layout consists of an android tablet (15-20") overlaid with a custom made tactile map of the environment. Their offering is unique as they consider usability both for blind and sighted visitors. Their maps consist of different tactile patterns combined with different colors. The maps also provide an audio feedback when touched. Urbas et al. explored several 3D printing techniques to create similar models (2016).

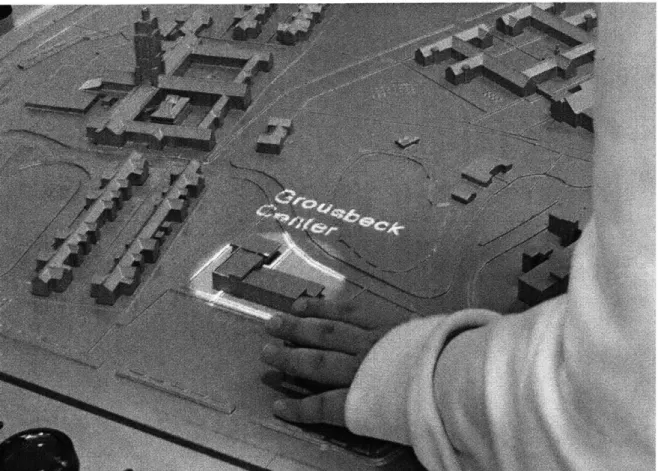

Another take on the tactile map solution is using spatially accurate models of the building. In contrast to the models above, this model also provides users with a sense of shape and structure of buildings. The model depicted below is a one of kind representation created for

the Perkins School for the Blind, created by Touch Graphics. It's a multimodal representation

of their sprawling campus which features audio feedback as well as visual highlights.

Figure 12: The multimodal interactive map in the Perkins school for the blind

The touchable nature of this map is aimed at blind visitors, but it also does a good job of

engaging sighted participants. The image below shows how visual highlights are used to

create interactions. This is a fundamental tenet of universal design, where the whole

spectrum of users must be considered. Not all of the needs can be met every time, but this

map comes pretty close.

Figure 13: The model also uses visual highlights to engage sighted participants.

Multi modality examples

Digital 3D representations

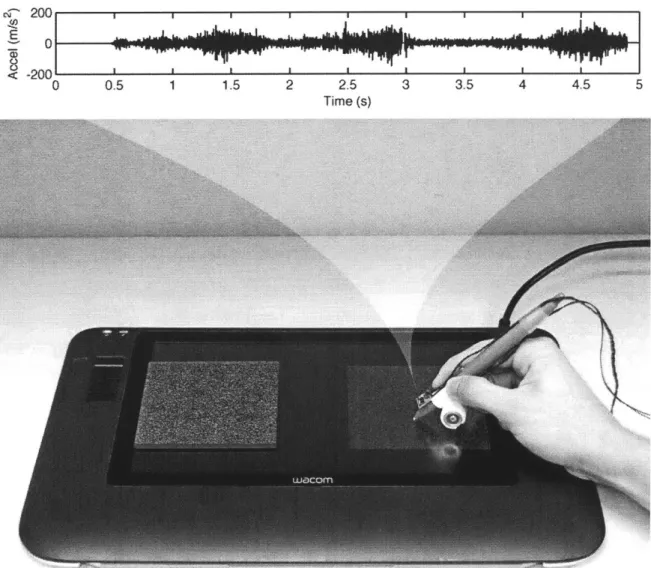

Haptography is a relatively new field. However, recent advances have made it possible to

digitize multiple surfaces and recreate them digitally with increasing fidelity (Kuchenbecker,

2011). In its current form the technology demonstrated by Kuchenbecker Et al. is good for

recreating surface differences, but does not apply well to 3D shapes. The haptography

stylus works on a simple principle. Textures are recorded through a stylus that's moved on a

surface. It records small variations on the surface along with lateral movement data. This

information is recreated on the output device using a voice coil. The haptography stylus is

meant to be an add on to full 3D actuated devices, such as the ones described in this section

below.

E~' -200 -00 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4,5 5 Time (s)Figure 14: Haptography apparatus recreates the feeling of textures through a stylus