Word, Image, Woman

Gavarni’s and the Goncourts’ Portrayal of the Lorette

Keri Yousif

Abstract

The article presents a comparative analysis of Gavarni’s lithographic series, “Les Lorettes” (1840-1843), and the Goncourt brothers’ verbal portrait, La lorette (1853). The two texts result in a change of tone: from promiscuous young woman to corrupt prostitute, and of medium: from image to word. The article considers these shifts in terms of the aesthetic and material conditions of caricature and verbal narrative. The pairing of Gavarni and the Goncourts also foregrounds the artists’ use of the lorette . Passed from caricaturist to writers, woman serves as a canvas, a stake in the artists’ aesthetic and commercial claims. And in the changing cultural field of nineteenth-century France, where caricature emerges as literary model and competitor, the stakes are high.

Résumé

Cet article propose une analyse comparée d’une série lithographique de Gavarni, «Les Lorettes» (1840-1843) et d’un portrait verbal des frères Goncourt, La lorette (1853). Les deux œuvres diffèrent à la fois quant à leur tonalité (on passe de la jeune femme promiscue à la prostituée corrompue) et quant à leur médium (on passe des images aux mots). L’article examine ces changements à la lumière des conditions esthétiques et matérielles de la caricature d’une part et du récit d’autre part. La comparaison des deux œuvres fait ressortir aussi l’usage que les artistes font du personnage de la lorette. Chez les caricatures comme chez les écrivains, la femme sert de prétexte à des débats de nature esthétique mais aussi commerciale. Et dans la culture sans cesse changeant de la France du 19e siècle, où la caricature occupe une place capitale, les enjeux de ces débats sont très élevés. Keywords

Beginning in the July Monarchy (1830-1848), the term lorette became a standard reference for the young women of the Parisian Notre Dame de Lorette neighborhood. The women had a reputation for promiscuity and the exchange of sex for money as they were reputed to be financially supported by multiple lovers. As a result, the lorette occupied a sort of mid-point between streetwalker and courtesan in the French panoply of nineteenth-century prostitutes. Numerous period definitions, portraits, and descriptions of the lorette suggest that what captivated artists, writers, social critics, and the public alike was the lorette’s liminal status. She was bound to neither the street nor one wealthy backer. Rather, she embraced a life of “gaieté, mœurs faciles, prodigalité, désordre joyeux, improvisé, festif, amants-protecteurs multiples, vie où l’on ‘s’amuse’” (Czyba 107).

For the French caricaturist Guillaume Sulpice Chevalier, known as Gavarni (1804-1866), and the writers Edmond (1822-1896) and Jules de Goncourt (1830-1870), the artistic figure of the lorette stands as an aesthetic marker. Gavarni’s series of lithographs, “Les Lorettes” (1841-1843), solidified the artist’s reputation as “le peintre de la vie et de l’habit du XIXe siècle” (Goncourts, Journal 2: 59). Indeed, Gavarni’s “Les Lorettes” became the baseline for subsequent representations of the lorette. As Charles Baudelaire argued, Gavarni “a créé la lorette” (2: 560). Gavarni’s fluid illustrations, humorous captions, and collective portrayal of the lorette as a flirtatious, unfaithful lover established the figure as an object of both visual and sexual pleasure. Gavarni’s viewers, like the lorette’s lovers, enjoyed her beauty and her casual approach to life. The Goncourt brothers followed Gavarni’s lead, publishing a verbal portrait of the lorette in 1853, which garnered the writers their first commercial success. In contrast to Gavarni, the Goncourts present the lorette as an insatiable prostitute whose appetite for men and their money threatens the social order. With sections on the lorette, her maid, her conquests, and her parents, the Goncourts’ text offers readers a verbal dissection of the lorette that rewrites Gavarni’s lighthearted women as crass, ambitious gluttons, “poétiques comme des tirelires!” (Goncourts La lorette).

Critics have argued that this shift, from the lorette as carefree pleasure to calculated destruction, can be read in terms of the changing social and political landscape of nineteenth-century France (Czyba, Sullivan). As the country moved from the July Monarchy (1830-1848) to the Second Empire (1852-1870), towards a burgeoning capitalist society spurred by urbanization and industrialization, the lorette evolved in accordance and as a means to map social change and anxieties. In a society increasingly structured around commodities and capital, the lorette became more pragmatic in her negotiation of goods and services. Gavarni’s playful portrayal of the lorette thus gives way to the Goncourts’ narrative of a corrupt man-eater. In each case and, importantly, in the progression from Gavarni to the Goncourts, the figure of the lorette functions as an artistic tool for social commentary. This analysis of the evolution of the lorette is compelling, but it does not fully account for the case of Gavarni and the Goncourt brothers in that it does not consider the significant transposition of the lorette from artist to writer, image to word. Artistic medium is a vital component of the cultural and historical context of Gavarni’s and the Goncourts’ portrayals. Art historians have studied Gavarni’s œuvre in this context, documenting the artist’s contributions to the field of nineteenth-century caricature and popular visual culture (Dolan “Upsetting the Hierarchy,” Gray, Kinsman, Kleinert, Le Men “Le panorama de la grande ville,” Sheon). Additional scholarship focuses on the artistic exchange between Gavarni and the Goncourt brothers, as well as their historical friendship (Le Men “Les Goncourt et Gavarni,” Dolan Gavarni and the

Critics, Suton). This latter work points to places where caricaturist and writer overlap, providing an

overview of the artists’ influences and divergences. What remains to be studied, however, is the singular example of Gavarni’s and the Goncourts’ lorette in terms of medium: how do the aesthetic and material conditions of caricature and verbal narrative, the illustrated press and book publishing, contribute to the artists’ portrayal of the lorette? The article that follows seeks to answer this question, the goal being to complement existing scholarship on the lorette and the Gavarni-Goncourts relationship by revisiting the artists’ representations of the lorette in dialogue and with a focus on artistic medium.

Gavarni’s and the Goncourts’ portraits of the lorette stand as key texts for such an investigation. They mark the end points of the lorette’s reign, her evolution as cultural icon, and the move from visual to verbal representation. The publication of the Goncourts’ La lorette also marks the beginnings of the writers’ friendship with Gavarni, the three men meeting just one year earlier, in 1852 (Le Men, “Les Goncourt et Gavarni” 71). The Goncourt brothers will spend much of their careers on what they term “Gavarniana”: reviews, journal entries, a biography, and a general, lifelong fascination with the caricaturist and his work (Le Men, “Les Goncourt et Gavarni” 76-78). Yet if the writers looked to the artist as a model, they also sought to compete with him by offering their own portrait of the lorette. Certainly, their choice of the lorette as subject matter, following Gavarni’s notable success, brings the question of artistic competition to the fore. It also implies the need to establish artistic difference rather than influence. What is more, both portraits of the lorette fall in the middle of the rise of popular visual imagery in the nineteenth century. While the trend catapulted Gavarni into the spot light, it cast a shadow on literary production as writers were now forced to contend with an encroaching image. The Goncourts’ portrait can thus be read as not only a response to Gavarni but also to the more general influx of caricatures and illustrations.

It is important to note that the artistic interchange between Gavarni and the Goncourts takes place on the body of the lorette. Woman serves as a canvas on which each artist makes his mark. The female body is, as Luce Irigaray argues, a form of exchange: “la société que nous connaissons, la culture qui est la nôtre, est fondée sur l’échange des femmes. . . . les hommes ou les groupes d’hommes, font circuler entre eux les femmes” (167). The exchange of woman, from Gavarni to the Goncourts, allows the artists to compete on and over the lorette, using the figure to establish their artistic potency. This article will trace this exchange, beginning with Gavarni’s lithographic series. The Goncourts’ La lorette will then be read in relation to Gavarni’s original images. At each juncture, the female body will be considered as a site of artistic staging passed from caricaturist to viewer, caricaturist to writer, and writer to reader.

As briefly stated, nineteenth-century France witnessed an explosion of caricature and illustration. The growth of lithography and the advent of mechanical printing presses and end-cut, wood engraving, which allowed word and image to be printed on the same page, made images easier, quicker, and eventually cheaper to produce (Melot). The social and political climate in France was also ripe for the rise of popular imagery in that a temporary relaxation in government censorship, legislation mandating a public school system for boys and later girls, and a general literacy movement aligned to make the image

artists delineated the varying types of prostitutes and courtesans in a series of visual and literary texts (Bernheimer, Menon, Sullivan). These texts collapse visual and sexual pleasure by detailing, in word and image, the lives of prostitutes. Sexual and visual pleasure also align with consumer pleasure in that the novels, illustrated newspapers, books, and albums and the imagined prostitute are all consumed by a paying customer. As Honoré de Balzac summarized the July Monarchy: “Savoir vendre, pouvoir vendre, et vendre! . . . Il ne s’agit encore que de plaire à l’organe le plus avide et le plus blasé qui se soit développé chez l’homme . . . . Cet organe, c’est l’œil des Parisiens” (7: 847).

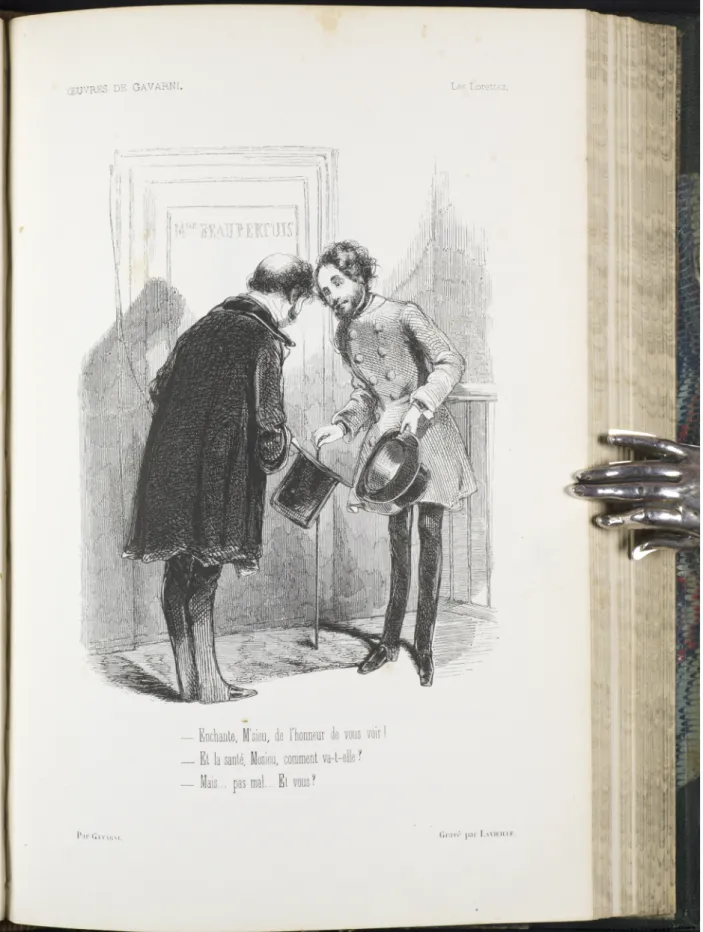

Gavarni capitalized on the period’s conflation of visual, sexual, and consumer pleasure in his lithographic series, “Les Lorettes.” The series offered readers a humorous and tantalizing peek into the intimate world of the lorette. Gavarni simultaneously announces and encapsulates the series’ visual and sexual offerings in the caricature “Enchanté M’sieu” (fig. 1), in which two men meet outside the door of Mlle Beaupertuis. The men greet each other, and the one inquires about the other’s health. The second man responds hesitantly, confounded by the use of the third-person, singular pronoun, elle. Given the woman’s name on the door, viewers assume the confusion is due to the man’s prior encounter with elle, Mademoiselle Beaupertuis, the exact woman whom the second man has come to see. The pun on elle, a referent for both la santé and Mlle Beaupertuis, as well as the awkward meeting of the men outside her door, results in a humorous portrait of the lorette’s life, namely her juggling of multiple lovers, who face each other as compatriots and potential rivals. These are men of different ages, the one balding, the other with a full head of hair; and of different social groups, the standard frock coat of the bourgeoisie and the more fitted, less traditional jacket of the younger man, signifying an artist or perhaps a dandy. The men are nonetheless united in their mutual partaking of elle.

Figure 1. Gavarni, “Enchanté, M’sieu,” “Les Lorettes,” Œuvres choisies. Vol. 1. Paris: J. Hetzel, 1846-1848.

Mademoiselle is an additional verbal/sexual pun as the fictional name Beaupertuis consists of the adjective beau and the noun pertuis: a beautiful channel. From caption to image, Gavarni’s caricature presents a woman and a moment of sexual exchange, both between the two men figured and the image’s external viewers. Like the lorette’s diegetic lovers, Gavarni’s viewers will metaphorically open Mlle Beaupertuis’ door, entering her private space via the artist’s illustrated series.

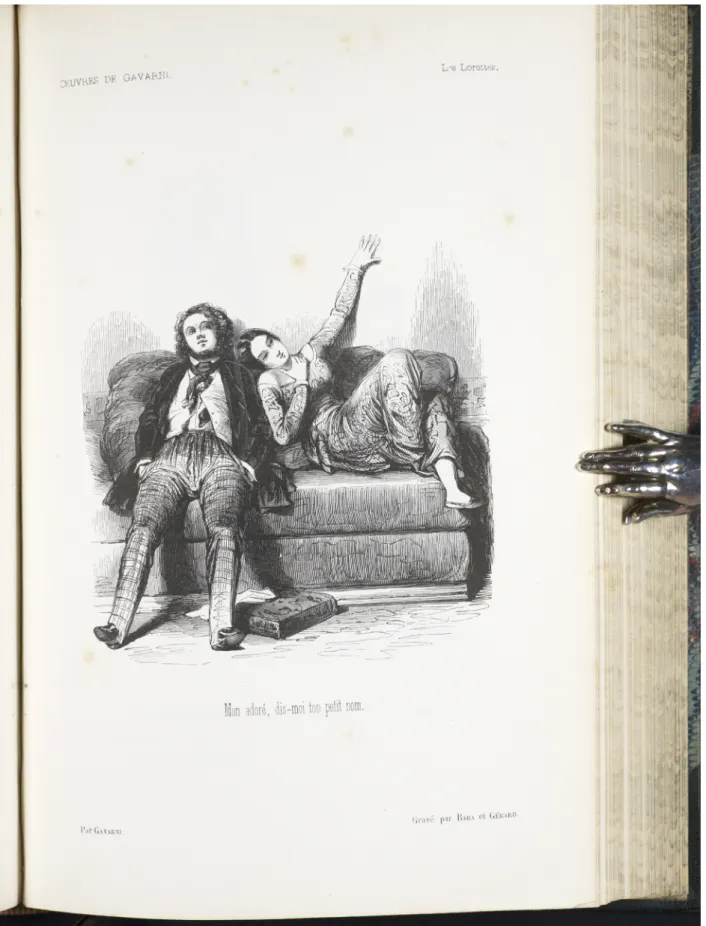

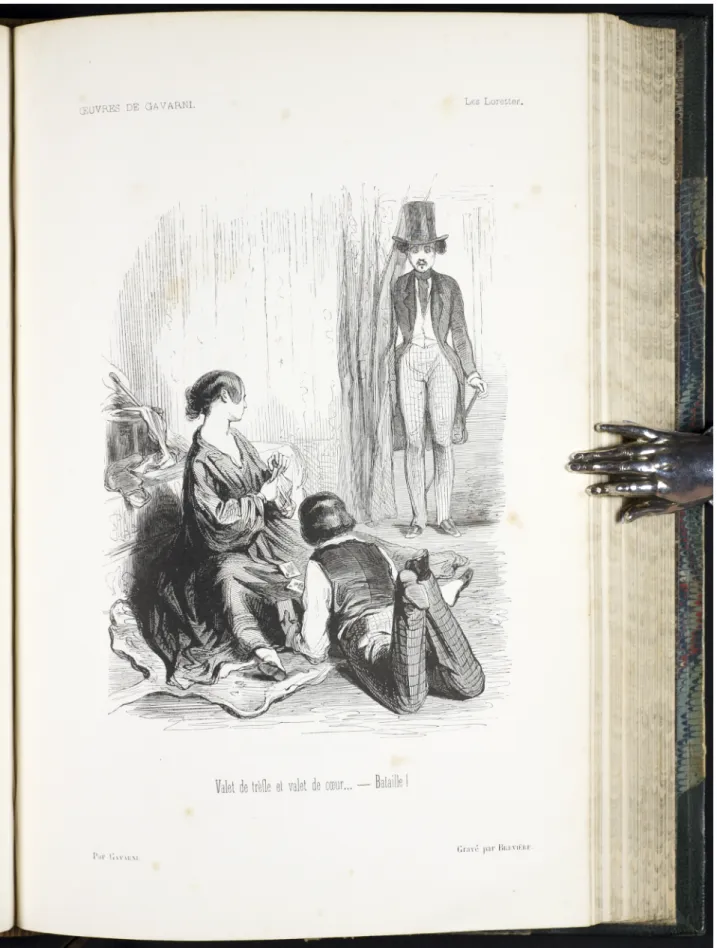

The lorette’s world is punctuated by men and amorous encounters. In “Mon adoré,” the lorette lounges with her lover, leaning on her male companion, one arm seductively running along the wall, the other clutching her heart (fig. 2). Her legs are crossed and pulled into her body, which results in the exposure of her ankle. The man is also relaxed, slouched on the couch, his legs stretched out before him. The scene is one of romance, two lovers tucked away in an interior setting. Despite the couple’s intimacy, the lorette does not know the man’s first name. As in “Enchanté M’sieu,” Gavarni’s caption produces a humorous, verbal-visual juxtaposition that parodies the lorette’s actions and corresponding morals. In “Valet de trèfle,” the lorette appears in a similar setting, wearing a dressing gown and sitting on the floor playing cards with a male companion (fig. 3). The physical position of the figures suggests an intimate, sexual relationship, as the man leans between the lorette’s spread legs, tossing cards onto her lap. His hat, gloves, and a cane lay on the side table, metonymically reinforcing this reading by intimating a state of undress. A second man stands in the doorway, shocked to find the lorette with another. As the caption explains, the two men are rival lovers caught in a ménage à trois. Following Gavarni’s metaphor of cards, the player with the strongest hand will win. For the lorette, love is a game, one to be played repeatedly and with a variety of opponents. “Mon adoré” and “Valet de trèfle” turn on the voyeuristic pleasure of observing the lorette in her private space during amorous encounters. In Paul-André Lemoisne’s words, “Voici la lorette à sa toilette, débraillée, dépeignée. . . . La voici lisant vaguement, souplement étendue à plat ventre” (138). Much of Gavarni’s portrayal of the lorette features the woman in compromising positions with different, often numerous, men, the two figures in “Enchanté M’sieu” a prefiguration of the world behind the closed door. Gavarni’s images also play off the suggestive juxtaposition of word and woman, as the captions sexualize the women figured through a series of puns and innuendos. In sum, the captions work in allegiance with the images, giving viewers a totalizing portrait of the lorette: what she looks like, whom she meets, what she does, what she thinks, and what she says. Consequently, the viewers’ pleasure stems from the combined voyeuristic and omniscient perspective of Gavarni’s images: they can look without being seen.

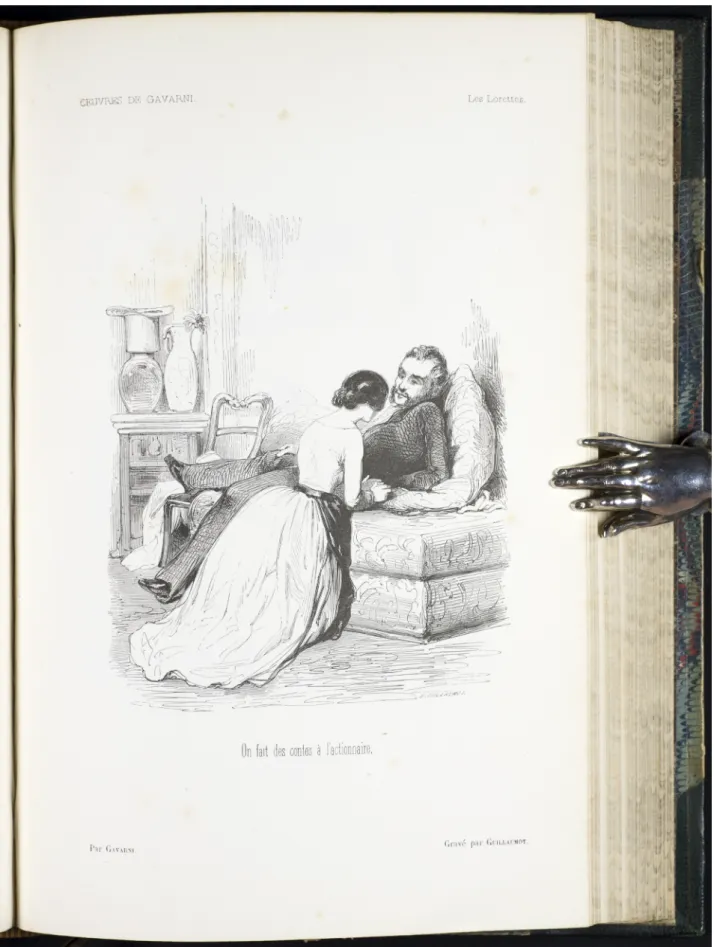

This look, however, comes at a price. The fictional men in Gavarni’s series paid for their time with the lorette, the encounters colored by the implicit exchange of sex and money. “On fait des contes” depicts the lorette in a position of submission, as she kneels before a man, her hand pressing his, her head lowered in obedience (fig. 4). Analogous to previous images, “On fait des contes” presents an interior scene, perhaps a boudoir as the man reclines on an ottoman. The intimate nature of the couple and their interaction is framed by the verbal caption, which announces their discussion to be double, both “faire des contes,” to tell stories; and “faire des comptes,” to do the accounts. The homophones contes/comptes underline the fiction and financial transaction underway in the image. Following Gavarni’s series, which establishes the lorette’s multiple lovers, the viewers of “On fait des contes” assume that the lorette fictionalizes her account of loyalty and need in hopes of putting her romantic and financial books in

Figure 2. Gavarni, “Mon adoré,” “Les Lorettes,” Œuvres choisies. Vol. 1. Paris: J. Hetzel, 1846-1848. Photo

Figure 3. Gavarni, “Valet de trèfle,” “Les Lorettes,” Œuvres choisies. Vol. 1. Paris: J. Hetzel, 1846-1848.

order. Mirroring the physical positioning of the figures, the man rules over the lorette as “actionnaire” or stockholder. She, in turn, is a commodity and an investment, supported, regardless of her potential tale, by a number of financial backers.

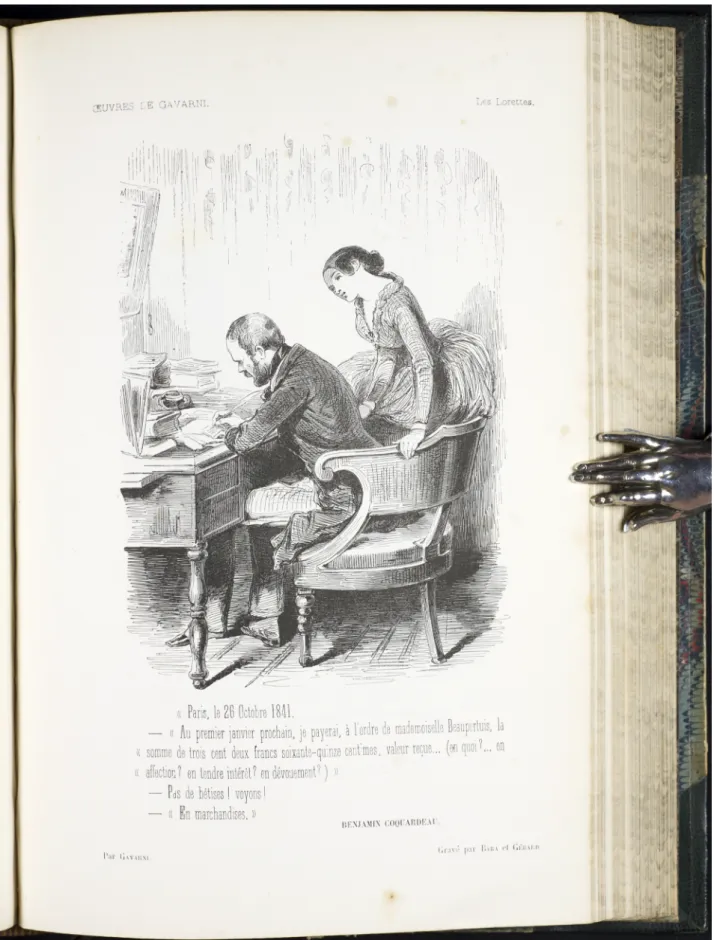

The same parallel, between money and sex, is literally spelled out in a second image, in which the male lover writes a promissory note to the lorette for services rendered (fig. 5). The man teases that the money is in exchange for the lorette’s affection, perhaps even devotion. In the end, Mademoiselle Beaupertuis and Benjamin Coquardeau agree on the final term, merchandise, an accord that implies that each of them is aware of his and her specific role. The older, bourgeois man plays the part of banker, paying for sex, and the young, beautiful woman is cast as the man’s mistress, available for a fixed price. Benjamin Coquardeau’s name, coquardeau meaning sot or niais, suggests that while he may be aware of the transaction underway, he is still a fool. As Gavarni’s viewers know from “Enchanté, M’sieu,” Coquardeau is one of several men to wait outside Mlle Beaupertuis’ door. Gavarni’s repeat use of Mlle Beaupertuis establishes the lorette’s modus operandi: to seek amorous and financial support from a variety of men.

The linking of sex and money in “Les Lorettes” is humorous and playful. The lorette may seek money from her lovers, but she does so in a flirtatious way, leaning over them, putting her head on their knees, smiling as she explains her needs. And the men respond accordingly, amused and willing to accept her requests, as evinced by Coquardeau’s jest of the lorette’s value. These are not men financially ruined by the lorette. Moreover, her practice of multiple lovers appears more awkward than brutal betrayal. Gavarni’s aesthetics reinforce this reading of “Les Lorettes.” The fluid lines, soft shading, intimate positioning of figures, and an interior setting all create a sympathetic portrait of the lorette. She is physically and morally soft on the viewer’s eyes.

Gavarni’s approach to the lorette stems, in part, from its original venue. His series was first published in the illustrated, daily, satirical newspaper, Le Charivari. Following Le Charivari’s format, Gavarni’s caricatures appeared as full-page images, part of the newspaper’s promise of a new caricature every day. Although Le Charivari’s circulation remained limited, rarely more than 3,000 copies, it stood as the biggest, daily, satirical newspaper of the period (Watelet 371). Furthermore, its editor, Charles Philipon, recruited key artists: Honoré Daumier, Henri Monnier, Traviès, Grandville, and Gavarni, whose political and social critiques made Le Charivari one of the most influential periodicals of its time. Like all newspapers, Le Charivari was subject to government censorship. Following the reinstatement of prior censorship for images in 1835, Le Charivari had to negotiate its role as an illustrated, satirical newspaper with the constraints of receiving government approval for caricatures prior to publication (Goldstein). Gavarni’s series offered the exact balance in that the lighthearted images were only coded sexual, and hence in potential violation of the censor, via indirect references and puns. “Les Lorettes” could pass the censor and still captivate Le Charivari’s audience with tantalizing images that satirized sexual promiscuity.

Figure 4. Gavarni, “On fait des contes,” “Les Lorettes,” Œuvres choisies. Vol. 1. Paris: J. Hetzel, 1846-1848.

Ultimately, the allusions, double entendres, and innuendos in Gavarni’s “Les Lorettes” align the caricaturist with his heroine; he too is selling sex, exchanging a woman for money. In “Les Lorettes,” he creates a promiscuous, financially supported woman and sells her to the public: 4 francs a month or 60 francs for an annual subscription of Le Charivari. Just as the lorette, Gavarni’s lithographic series is a visual-sexual commodity, an image, which is based on another visual-sexual commodity, the prostitute. This mise en abyme of ocular and carnal consumerism, the lorette to Gavarni’s “Les Lorettes,” emblematizes the period’s growing industry of visual culture. Similar to the new store windows and cafés, illustrated newspapers and prostitutes were based on visual enticement with the end goal being a financial transaction. As the lorette feeds Gavarni, the caricaturist feeds Le Charivari, each one part of the growing field of popular visual culture, in which images became a media staple. And just as the lorette’s diegetic lover, the public was buying. Gavarni’s series lasted two years and was followed by a number of literary takeoffs, including its contemporary La physiologie de la lorette by Maurice Alhoy (1841) and later Mémoires d’une lorette by Maximilien Perrin (1843), Filles, lorettes et courtisanes by Alexandre Dumas, père (1843), and La lorette, chansonnette nouvelle, unattributed (1847). The proliferation of publications crowned the lorette a commercial success. She was bought, sold, and consumed as woman, word, and image.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt entered the market in 1853 with their verbal portrait, La lorette. Literary debutants, the authors sought to make a name for themselves. Although they had self-published their first novel, En 18…, in 1851, the work received little critical or market attention. In 1852, they moved to art criticism, publishing a review of the salon. That year, they additionally wrote for the newly founded, satirical newspaper, Paris, through which they met Gavarni. The artist served as mentor and model for the young writers. The Goncourts’ appreciation of Gavarni, however, did not preclude artistic rivalry, for while the subject matter of the lorette assured sales, it forced the writers to compete with Gavarni and his legendary images. Unable to recreate Gavarni’s visual pleasure, the Goncourts had to adopt an alternative artistic strategy, one that borrowed Gavarni’s lorette, but presented her in a new light.

Accordingly, La lorette opens with a tribute to Gavarni and a proclamation of difference: “à notre

ami Gavarni. . . . À vous, ce petit livre. Vous trouverez dans ces quelques lignes du cru, du brutal même: il est des plaies qu’on ne peut toucher qu’au fer chaud.”1 The Goncourts’ dedication acknowledges

Gavarni’s parentage in the creation of the lorette as artistic figure. Yet it also announces a break with Gavarni by proclaiming a textual violence: raw, brutal wounds that expose the woman beneath the coquettish glances and gowns of Gavarni’s figure. This difference is doubly marked by the inclusion of a prefatory note on the first page of the book, the page facing the dedication: “Nous prions donc le lecteur de vouloir bien faire attention aux dates de publication de ces six articles. Il verra ainsi qui, le premier, a protesté contre l’assomption de la Lorette” (Goncourts La lorette). Here, the Goncourts draw the reader’s attention to the fact that the text’s sections were previously published as individual articles in L’Éclair

Figure 5. Gavarni, “Paris, le 26 Octobre 1841,” “Les Lorettes,” Œuvres choisies. Vol. 1. Paris: J. Hetzel,

and Paris (Barbier Sainte Marie 9-10). The dating of the texts establishes the Goncourts’ portrait as the first to counter the artistic elevation of the lorette, including that of Gavarni. The Goncourts’ pen will be the first hot iron, used to strip away the lorette’s status as playful lover, wound by wound, page by page. Following the terms of the dedication, what the Goncourt brothers’ find is painful. As the opening paragraph states, the lorette “est née avec l’instinct de la truffe” (Goncourts La lorette). This makes her both a gourmet, who loves the delicate mushrooms, and a pig, the animal that is trained to root out the elusive truffle on the forest floor. Aligned with a sow, the lorette becomes greedy and grotesque, a beast that wallows in overindulgence. As the Goncourts explain, “elle soupe, parce que cela est son état” (La

lorette). The theme of instinctual, excessive consumption sets the tone for the Goncourts’ portrait of the lorette. She consumes people just as she consumes food: “Elle a un entreteneur . . . elle a un amant de

cœur . . . elle a une portière . . . elle a une femme de ménage” (Goncourts La lorette). The authors’ repeat use of “elle a” makes the lorette the grammatical subject of the sentence and the owner of the following objects. In a reversal of Gavarni’s images, in which the lorette was consumed, she turns the tables on her lovers by owning them. Parallel to the maid, the men in the lorette’s life are servants.

This revision makes the lorette a dangerous figure. Contrary to the flirtatious women of Gavarni’s images, the Goncourts’ lorette stands as an aggressive eater, one that will eventually ruin her lover’s life. As testament to her destructive power, the Goncourt brothers recount the case of the old gentleman, who “apporte à la lorette de l’or tout neuf. Il fait porter à la lorette . . . le premier régime de bananes, . . . le flacon en cristal de roche . . . . Il fournit la lorette de cigares . . . . Il a fait venir . . . un chien d’Angleterre et des coussins de cygne de la province d’Oran” (La lorette). So many gifts and luxuries, but as the Goncourts ask: What does the lorette do in return? According to the writers, she humiliates the man, ordering him to kneel before her and prostrate himself financially and emotionally. While degrading in its own right, the lorette’s abuse of the older gentleman ultimately leads to a larger realm of destruction: the family, for in his absence, the gentleman’s daughter “se demande, le cœur gros, pourquoi son père sort tous les soirs après dîner,—et si c’est qu’il ne l’aime plus!” (Goncourts La lorette). Although the old man is equally to blame, it is nevertheless the lorette who is branded “a thief,” robbing the man and his family of money, time, and affection.

Lest the readers think that the old man is an isolated example, the Goncourts remind their audience that the lorette has many victims, among the most popular “Monsieur Tout-le-Monde,” who is “de toutes les nuances de cheveux, de toutes les nationalités, de toutes les tailles, de toutes les religions, de tous les âges” (La lorette). The Goncourts’ definition of “Mr. Everyman” includes the male readers and the female readers’ husbands, fathers, brothers, and lovers. The latter may consider themselves superior to the old man, incapable of such baseness, but the Goncourts argue otherwise: “Malgré tout, c’est Monsieur Tout-le-Monde qui, par toutes ses mains, donne la pâtée à la femme-estomac” (La lorette). Again, the

lorette is described in terms of her compulsions; she is depicted as a digestive organ. Consequently,

she has neither heart nor brain; she is driven purely by her desire to consume. “Mr. Everyman” dreams that “quand il pose la main sur la poitrine de la créature, de sentir battre quelque chose sous sa main”

a heartless whore. As Czyba and Sullivan argue, this shift is representative of the changing social and political climate. Yet the Goncourt’s portrait of the lorette can also be read as an artistic gambit. In choosing to publish a book on the lorette, the Goncourts must distance themselves from other writers and artists. Their verbal dissection of the lorette counters past texts that romanticized the lorette. However, their main competitor is not another writer; it is Gavarni, the caricaturist who brought the lorette to life, making her a commercial and artistic success. The Goncourts must establish their difference, above all, from the original master, Gavarni. To do this, they emphasize the lorette’s status as consumer rather than object, constructing a sort of inverse image to that of the artist by revealing the “brutal” reality that hides beneath her charming exterior. What Gavarni visually glamorizes, the Goncourts verbally probe. Both portraits turn on voyeurism: Gavarni’s titillating images and the Goncourt brothers’ textual dissection. In fact, although the portraits reach different conclusions, they employ the very same artistic means, for despite the Goncourt brothers’ efforts to distinguish themselves from Gavarni; the end result is a verbal caricature. Like Gavarni’s original series and individual images, the Goncourts’ short text is divided into a succession of verbal sketches that rely on reduction, exaggeration, and repetition. These are the exact tenants of visual caricature, in which a figure is reduced to its most salient characteristics for humorous effect and as to be immediately recognizable. Gavarni’s lorette is identified through the artist’s repeat depiction of clothing, setting, and company, and the Goncourts’ figure is marked by recurrent greed and gluttony. Gavarni and the Goncourts work in different medium: image and word, however they engage the same genre. This parallelism suggests the commercial and aesthetic power of caricature in mid-nineteenth-century France. Indeed, the growth of popular visual imagery reshaped the ways in which writers entered and competed in the cultural market (Berg). The Goncourts establish their difference from Gavarni by competing in the same genre and over the same subject. And the work paid off. In their journal, the Goncourts write: “La lorette paraît. Elle est épuisée en huit jours. Il nous apparaît pour la première fois qu’on peut vendre un livre” (1: 111). The text went into a second edition in 1853, with seven total editions by 1883 (Barbier Sainte Marie 11-12). The popularity of the Goncourts’ La lorette, published some ten years after Gavarni’s original images, testifies to caricature’s market prowess. While a novel may have gone unnoticed, a collection of verbal caricatures earned the Goncourts their first commercial feat.

The Goncourts’ success is also due to woman. Regardless of the writers’ portrayal of the lorette as a rabid consumer; she remains an object, a text created by artists for public consumption. She may purportedly eat the men in her life, but the act is reciprocal, the readers of La lorette enjoying their verbal feast. The Goncourts, just as Gavarni, are caught in their own portrait, becoming a sort of artistic “Mr. Everyman,” who uses the lorette for his own advancement. The lorette is passed from caricaturist to writer as a site for artistic exchange and recognition. Whether word or image, the prostitute sells. More important is the way the evolution of the lorette, from daily caricatures to published text, illustrates the exchanges, appropriations, and revisions at work across media. The shifts of figures, tropes, and themes mark key moments in which artists and writers both compete and unite in their artistic exploitation of woman.

Works Cited

Balzac, Honoré de. Œuvres complètes. Ed. Pierre-Georges Castex. 12 vols. Paris: Gallimard, 1976-81. Print.

Barbier Sainte Marie, Alain. Introduction. La lorette. Edmond and Jules de Goncourt. Ed. Alain Barbier Sainte Marie. Tusson, Charente: Du Lérot, 2002. 7-34. Print.

Baudelaire, Charles. Œuvres complètes. Ed. Claude Pichois. 2 vols. Paris: Gallimard, 1975-76. Print. Berg, Keri A. “Contesting the Page: The Author and the Illustrator in France, 1830-1848.” Book History

10 (2007): 69-101. Print.

Bernheimer, Charles. Figures of Ill Repute: Representing Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century France. Durham: Duke UP, 1997. Print.

Crubellier, Maurice. “L’élargissement du public.” Histoire de l’édition française: le temps des éditeurs,

du romantisme à la Belle Époque. Eds. Roger Chartier and Henri-Jean Martin. Paris: Fayard,

1990. 15-39. Print.

Czyba, Lucette. “Paris et la lorette.” Paris au XIXe siècle: aspects d’un mythe littéraire. Ed. Roger Bellet. Lyon: PU de Lyon, 1984. 107-122. Print.

Dolan, Therese. Gavarni and the Critics. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1981. Print. — “Upsetting the Hierarchy: Gavarni’s Les Enfants Terribles and Family Life during the

‘Monarchie de Juillet.’” Gazette des Beaux Arts 109 (1987): 152-158. Print.

Gavarni, Guillaume Sulpice Chevalier. Œuvres choisies. 4 vols. Paris: J. Hetzel, 1846-48. Print.

Goldstein, Justin Robert. Censorship of Political Caricature in Nineteenth-Century France. Kent: Kent State UP, 1989. Print.

Goncourt, Edmond and Jules de. Journal: Mémoires de la vie littéraire. Ed. Robert Ricatte. 22 vols. Monaco: Imprimerie Nationale de Monaco, 1956-1958. Print.

— La lorette. First Edition. Unpaginated. Paris: E. Dentu, 1853. Print.

Gray, David. “Gavarni’s Parisian Populations Reproduced.” Printed Matters. Eds. Malcolm Gee and Tim Kirk. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002. 48-69. Print.

Irigaray, Luce. Ce sexe qui n’est pas un. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1977. Print.

Kinsman, Jane. “Developing Character: Gavarni’s Lithographs for Paris 1852-1853.” Gazette des

Beaux-Arts 115 (1990): 25-33. Print.

Kleinert, Annemarie. “Les Débuts de Gavarni, peintre des mœurs et des modes parisiennes.” Gazette des

Beaux-Arts 134 (1999): 213-224. Print.

Le Men, Ségolène. “Les Goncourt et Gavarni.” Francofonia 11.21 (1991): 71-85. Print.

— “Le panorama de la grande ville: la silhouette réinventée.” Pour rire! Daumier, Gavarni,

Rops: l’invention de la silhouette. Musée Félicien Rops and Musée d’art et d’histoire Louis Senlecq.

Paris: Somogy Éditions d’art, 2010. 21-156. Print.

Lemoisne, Paul-André. Gavarni, peintre et lithographe. Vol. 1. Paris : H. Floury, 1924. Print.Melot, Michel. “Le texte et l’image.” Histoire de l’édition française: le temps des éditeurs, du

Illinois P, 2006. Print.

Sheon, Aaron. “Parisian Social Statistics: Gavarni, ‘Le Diable à Paris,’ and Early Realism.” Art Journal 44.2 (1984): 139-148. Print.

Sullivan, Courtney. “‘Cautériser la plaie’: The Lorette as Social Ill in the Goncourts and Eugène Sue.”

Nineteenth-Century French Studies 37.3-4 (2009): 247-261. Print.

Sutton, Denys. “Gavarni and the Goncourts.” Gazette des Beaux Arts 117 (1991): 140-146. Print. Watelet, Jean. “La presse illustrée.” Histoire de l’édition française: le temps des éditeurs, du romantisme

à la Belle Époque. Eds. Roger Chartier and Henri-Jean Martin. Paris: Fayard, 1990. 369-382.

Print.

Keri Yousif is associate professor of French in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics at Indiana State University. She specializes in nineteenth-century French studies. Yousif is the author of Balzac, Grandville, and the Rise of Book Illustration (Ashgate 2012), as well as articles on French caricature and early French photography.