Building a Community of Reflective Practitioners:

A Reflection-in-Action with MIT DUSP by Carrie Sarah Watkins B.A. International and Global Studies Brandeis University, 2012 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2019 © 2019 Carrie Watkins. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author_________________________________________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 23, 2019 Certified by ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Lawrence Susskind Ford Professor of Environmental and Urban Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by_________________________________________________________________________________________ Ceasar McDowell Professor of the Practice Co-Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Building a Community of Reflective Practitioners:

A Reflection-in-Action with MIT DUSP By Carrie Sarah Watkins Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning On May 23rd, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning ABSTRACT In 1983, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Professor Donald Schön published The Reflective Practitioner. In this book, he challenged the prevailing view of professional practice, which he understood as linked to the positivist practice of technical rationality. He called on educational institutions to instead train professionals such as planners, architects, and teachers to be reflective practitioners - to practice reflection-in and on-action. In this thesis, I set out to explore the curious tensions and patterns that shape MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning’s relationship with reflective practice. This thesis is my reflection-in-action, the pursuit of knowledge through active interventions and observations. I worked with Professor Ceasar McDowell this Spring of 2019 to facilitate reflective sessions for practicum classes, and through observation, surveys, and interviews, I studied the reflections’ effects on class learning and effectiveness and on how students and faculty value and understand reflection. As an international leader, my home institution, and the locus of Schön’s work, MIT offers an excellent case example to study. I ultimately found that, while successful and innovative reflective practices can be found throughout DUSP, a large gap exists between the high value of reflective practice faculty and students espouse and the efforts individuals and the department as a whole actually take to train and incorporate reflective practice. This process also uncovered insights that I wove into a set of recommendations for students, faculty, and the department to help close this gap between espoused theory and theory-in-use. While my findings and analyses are specific to this location, I hope they will inform and provide energy to the broader conversation in support of reflective practice. Thesis Supervisor: Lawrence Susskind Title: Ford Professor of Environmental and Urban PlanningAcknowledgements

To Larry Susskind for showing me reflective practice in action. Your consistent and generous support has made all this possible. To Ceasar McDowell for living his dedication to the students in this department. To Dayna Cunningham for your radical commitment to weaving the arc towards justice. To my parents, a child psychologist and special education teacher who built careers of harnessing reflection as a tool for tikkun olam. To my sister, an artist and M.D. who is proving to the world that the details of care (often known as Frozen stickers) matter. To my friends in Camberville for holding me up with love, adventure, and song. To everyone at DUSP - faculty, students, staff - who supported me by filling out surveys, giving time and presence to long interviews, asking me how it was all going in the hallways, offering to read chapters, and dancing at the end of long days.“We look back and analyze the events of our lives, but there is another way of seeing, a backward-and-forward-at-once vision, that is not rationally understandable” -Rumi “our knowing is in our action” -Donald Schön

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 4

PART I. PROBLEM FRAMING ... 8

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ... 8

RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 10

CHAPTER 2 REFLECTIVE PRACTICE: AN IDEA EMERGES ... 11

THE ALTERNATIVE - REFLECTION ... 13

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE SINCE SCHÖN ... 14

PART II. THE STATE OF THE ART AT DUSP ... 20

CHAPTER 3 THE INTERVENTION: CEASAR'S CRITICAL MOMENTS REFLECTIONS ... 20

CMR I : LEADING EDGE QUESTIONS ... 23

CMR II: CRITICAL MOMENTS REFLECTION ... 31

CHAPTER 4 SURVEY AND INTERVIEWS ... 43

SURVEY ... 43

QUALITATIVE RESULTS: SURVEY AND INTERVIEWS ... 53

ANALYSIS OF INTERVIEWS ... 55

CHAPTER 5 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ... 66

PART III. ACTION ... 68 CHAPTER 6 RECOMMENDATIONS ... 68 APPENDICES ... 76 WORKS CITED ... 84

List of Figures

Figure 1 – Students participating in Leading Edge Questions reflection ... 23

Figure 2 - a meta-category ... 27

Figure 3 – Ceasar facilitating in CMR in a hallway ... 31

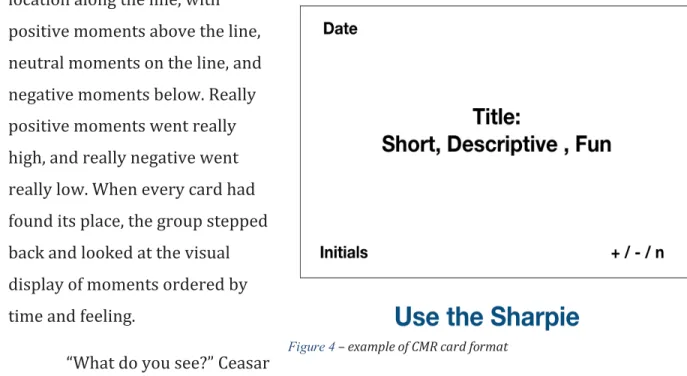

Figure 4 – example of CMR card format ... 32

Figure 5 – CMR moment referencing the first reflection! ... 33

Figure 6 – CMR personal moment ... 34

Figure 7 - students, TAs, and faculty creating a shared timeline in the CMR ... 36

Figure 8 Word Cloud of Survey 1 responses to where students engaged with reflective practice at DUSP ... 46

Figure 9 – Survey results ... 48

Figure 11 – Survey results ... 49

Figure 10 – survey results ... 49

Figure 12 – Survey responses for students who participated in the reflections ... 52

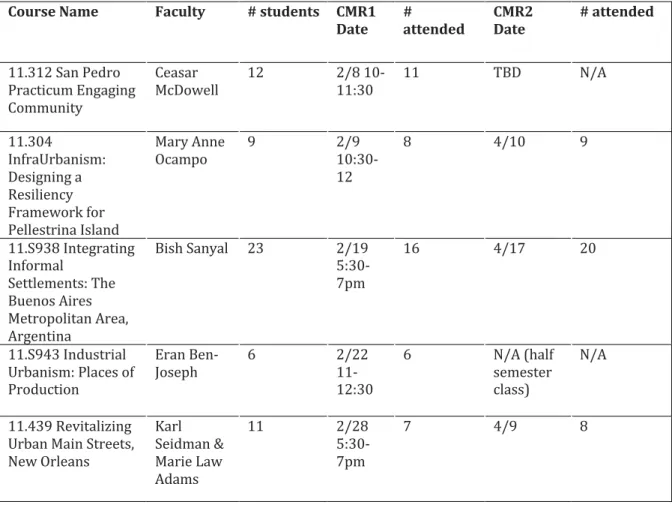

List of Tables Table 1 - PARTICIPATING PRACTICA ... 22

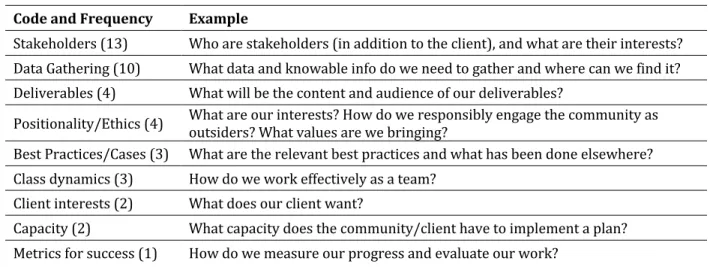

Table 2 - Categories of Meta Questions ... 28

Table 3 – CATEGORIES OF CRITICAL MOMENTS with frequency and percentage of total moments per class ... 40

Table 4 - SURVEY MEASUREMENTS OF REFLECTION AT DUSP ... 44

Table 5 Student Interview Demographics ... 53

Table 6 FACULTY INTERVIEWS ... 54

Table 7 - Student Positive Experiences with Reflections ... 56

Table 8 - Student experiences with limitations of Reflections ... 56

Table 9 - Student Experiences with Reflection Memos ... 60

Table 10 - DUSP Students and Faculty Definitions of Reflection ... 62

PART I. Problem Framing

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 1983, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Professor Donald Schön published The Reflective Practitioner. In this book he challenged the prevailing view of professional practice, which he understood to be linked to the positivist practice of technical rationality. He called on educational institutions to instead train professionals such as planners, architects, and teachers to be reflective practitioners. His theory was that they should primarily learn by doing. I first read The Reflective Practitioner last July. I had a copy shipped to The Netherlands, where I was working on an organizational development project with two Dutch dispute resolution firms. I asked my advisor, Ford Professor of Environmental and Urban Planning Lawrence Susskind, for advice, and he directed me to this book. In addition to reframing my summer work, The Reflective Practitioner also hit close to home. Schön’s framing brought form and language to a discomfort I had felt my whole first year at MIT. Larry and I began discussing Schön’s ideas in the context of our department, the Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP), and this thesis project started to take shape. When I returned to DUSP in the Fall, I set out to uncover more of this department’s relationship with reflective practice. I attended office hours with several faculty, and I struck up informal conversations with classmates in the hallways. Some of these conversations directly referenced Schön and The Reflective Practitioner. Many did not. The faculty members I spoke with – with the exception of a newer member - were well familiar with Don Schön and The Reflective Practitioner, even referring to ideas as “Schönsian.” All faculty members shared with me some desire to more fully integrate reflective practice into DUSP. Of the dozen or more students I spoke with, however, I noticed that most shared some conceptual understandings of what reflective practice means, but had not heard of the professor or the book. As with faculty, I also found that students expressed desire to both learn about reflection and to reflect more in this program. A couple classmates, when Ishared more about The Reflective Practitioner, had “aha!” moments similar to mine, saying something like, “That’s it! That’s the tension I’d been feeling here that I couldn’t put into words!” The more I explored this topic, the more a few particularly curious tensions, patterns, and questions emerged. For one, while there seemed to be a shared value of reflective practice across the department, the term was not defined or stated anywhere. The only institutionalized reference is in an undefined “reflection requirement” for field-based practicum. The department even hosted a conference this Fall for the SPURS 50th Anniversary called “The Reflective Practitioner Reconsidered,” but, despite actively keeping an ear out all day, I didn’t hear anyone define the term. Definitions that implicitly arose from conversations, at the conference and in my conversations, did not necessarily conflict, yet they varied widely. I also found myself surprised at how supportive everyone was of my thesis, not just of my endeavor to document but of my interest in actively increasing reflective practice at DUSP. I had been expecting to find more resistance to the idea, from faculty and students. Instead, I found my inquiries met with enthusiasm and interest. If resistance to reflection wasn’t coming from lack of espoused value, then why did so many people still feel the reign of positivism and technical rationality? DUSP continues to honor Schön’s legacy, yet reflective practice seems to be at once highly valued and sparsely taught or practiced. Schön speaks about the feeling of surprise as a moment of choice. When we feel surprised, we can do what we so often do, which is brush it aside “in an attempt to preserve the constancy of our usual patterns of knowing-in-action” (1987 p.26). Or, Schön asserts, we can reflect. This thesis is my reflection, an effort to uncover the roots of my surprise. It is also not just reflection-on-action, a reflection of looking back at what has happened. By implementing an active intervention this past semester, I organized my process of discovery as a reflection-in-action, as learning-by-doing. I worked with Professor Ceasar McDowell to facilitate reflective sessions in five of the seven practicum this Spring Semester, 2019, and I studied the reflections’ effects on class learning and effectiveness and on how students and faculty value and understand reflection. I also conducted surveys and interviews, which I also consider forms of intervention in the sense that they’re sparking further conversations about reflective

practice. I view the Department of Urban Studies and Planning as my client for this thesis in the hope that the actions and results of my research will inspire the Department to consider placing greater emphasis on reflective practice and the training of reflective practitioners. My thesis will have three parts. First, it will trace the idea of “reflective practice” as it emerged from DUSP in the 1980’s. Second, it will describe my work with Ceasar facilitating these reflective sessions and gathering and analyzing the results. Third, I will generate a set of recommendations describing ways in which the department could become more reflective and train planners to become more reflective practitioners. As an international leader, my home institution, and the locus of Schön’s work, MIT makes an excellent case example to study. While my findings and analyses are specific to this department, I hope they can inform and prove useful to the broader conversation.

Research Questions

I organized my inquiry around three questions: (1) What is the state of teaching and practicing reflection at DUSP? What is DUSP’s espoused theory and theory-in-use of training reflective practitioners? Is there a gap between espoused theory and theory-in-use? (2) Do Ceasar’s Critical Moments Reflection interventions create opportunities for reflection-in-action that are otherwise missing in DUSP? (3) What do they reveal about ways in which DUSP could better train reflective practitioners? I hypothesized that students will both self-report and demonstrate enhanced learning and greater feelings of effectiveness as a result of the critical moments reflection exercises. I further hypothesized that these results will hold true across a range of practicums in DUSP, even though each is focused on a very different planning problem and taught by different faculty.I also hoped that student discussions generated during Ceasar’s interventions would prove valuable in helping DUSP better understand what MCP students want and need to learn in order to be effective planners.

Chapter 2 Reflective Practice: An Idea Emerges

Schön was operating as part of a larger movement challenging the dominant epistemological frameworks of his day. He explicitly set his work in the context of the writings of Edgar Schein, Nathan Glazer, Herbert Simon, and others who were working to identify the gap between professional knowledge and the demands of practice (Schön 1983). Schön was not the first to identify reflection as an important educational tool. He was himself a student of American philosopher and psychologist John Dewey, who wrote about reflection as an experiential learning tool that could turn “perplexity” and uncertainty into inquiry, learning, and resolution that improve practice (Deaton, C et al. 2013; Dewey 1933). Dewey understood reflection to be an active mental process that incorporates both reason and emotion and allows us to rise above otherwise routine thought and decision-making processes. Scholars have also noted that the specific employment of reflection as a tool has ancient origins. Learning-through-reflection was transcribed by ancient religions and philosophers. Socrates wrote about reflection as a necessary practice of “active thought,” and Plato famously quoted Socrates in his work The Apology as saying “the unexamined life is not a life worth living” (Deaton et al. 2013). Reflection has also been practiced and developed as an epistemological frame and pedagogical tool through spiritual traditions, including Buddhist mindfulness and meditation dating from the fourth century BCE (Deaton et al. 2013; Raelin 2001; Scharmer 2018). Schön incorporated Dewey’s basic understanding of reflection and used it to pose a challenge to the positivist epistemology of practice and pedagogy which he termed “technical rationality.” Embedded in the foundation of many Western institutions of higher education (founded and formed in the height of 19th and early 20th century), positivism was a philosophical system born from the Enlightenment that holds that every rationally

emergence of most modern professions. Technical rationality involves the understanding of professional practice as “instrumental problem solving made rigorous by the application of scientific theory and technique” (Schön 31). In this sense, professional expertise requires possessing and applying a discrete set of skills, knowledge, and techniques to each new situation in order to solve problems. The shortcoming of this way of thinking is that it cannot cope with the “complexity, uncertainty, instability, uniqueness, and value conflict” of real practice (Schön 18). It ignores and is incompatible with many of the core competencies planners actually need to be effective in practice. The elements missing from technical rationality, according to Schön, reflect an “irreducible element of art” in practice that is not “invariant, known, and teachable” but is nevertheless “learnable” (18). A tightrope walker cannot and does not need to explain in words exactly how she does what she does; much of the knowing professionals demonstrate cannot be explained but rather is tacit, “is in our action” (Schön p.49). One example of the tacit (or subjective) skills planners need to bring to their practice is a way of defining and understanding a problem. Technical rationality defines professional skills as the tools used to solve problems, but Schön points out the necessity of first defining a problem effectively.1 In the complex and constantly changing situations in which professionals operate, they invariably have incomplete information. Thus, problem definition is subjective and imperfect – qualities that positivism presumes away. A planner can look at a neighborhood with high rates of violent crime and construe the situation in many ways. The problem might be a function of low morality, poor gun control, poverty, or systemic racism. Understanding how to frame a problem in a way that makes it susceptible to resolution requires careful reasoning, but the dynamics involved cannot be studied through controlled experiments or defined using a common set of scientific laws. Thus, technical rationality won’t help. Schön was writing in reaction to what he called a “crisis of confidence in professional knowledge.” He observed, in part stemming from the radical cultural shifts of the nineteen sixties, a public outcry against “the long-standing professional claim to a 1Schön wrote an entire book about this idea with Martin Rein, Frame Reflection, in the

monopoly of knowledge and social control” resulting from professionals not living up to expectations (p.11). He also saw a widening gap between the theories created and taught in the professional schools and the actual practices of effective professionals, resulting in a hierarchical dilemma between “rigor or relevance, in which one must choose between the narrow confines of technical practice or “muddling through” the unacknowledged territory of intuition, learning by doing, trial and error, and tacit knowledge (p.49). In professional planning, this crisis manifested in Jane Jacobs and others scathingly breaking down the hegemony of urban renewal and the male-dominated field of planning. Through advocating for reflection-in-action, Schön brought to this conversation a solution of not booting out planners from city planning, but rather showing a trust in planners’ ability to learn through reflection (Fischler 2012). While the sense of “crisis” may not be as vivid today as it was when he was writing thirty years ago, the underlying discrepancy between the actual work of professional practice and the instrumental theories the academy espouses persists (Schipper 1999).

The Alternative - Reflection

Schön advocated for a shift from positivist framing and its resulting pedagogy to understanding the core mode of professional understanding as constructivist and rooted in action. He posited that effective professions demonstrate a knowing-in-action. The tightrope walker demonstrates this knowing-in-action in performing her art despite being unable to systematically describe it. This knowing should not be static but rather part of a continuing process of learning. Learning by doing, posits Schön, takes place through reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Reflection-in-action is the learning that happens through and in the moment of conscious awareness and experimenting. Reflection-on-action is the learning that happens from thinking back on a previous moment (Schön 1987). Schön calls on academics and practitioners to develop a new epistemology of practice that does not reject technical problem solving but rather places it in a broader repertoire of professional competencies framed by reflective inquiry.

Schön recognizes a broad range of actions that constitute reflection. Reflection can range from idle musing to deliberative inquiry. It can be motivated by surprises and challenge or by a recognition of patterns. A person may reflect on tacit values and norms, strategies, mistakes and successes, or their social position within a larger context of a whole. Reflection is a capacity each person possesses that can be further developed as a competency and a skill. Recognizing and legitimizing reflection as a necessary tool for professional practice and learning, Schön posits, will allow practitioners to overcome the dilemma of “rigor or relevance” and quell the “crisis in confidence” of professionals.

Reflective Practice Since Schön

Schön was not only building on the work of others, he was also part of a larger contemporary conversation within his broader field. He worked and wrote with several colleagues, including Chris Argyris and Martin Rein. Still, The Reflective Practitioner remains a keystone work; it has been cited over sixty thousand times (Google Scholar). Since these initial efforts to define and document reflective practice, the conversation has continued. Schön wrote about professions in a broad sense -focusing his case studies in The Reflective Practitioner on Architecture, Psychotherapy, Town Planning, and Management. His work has had a lasting impact in many fields, including the field of planning (Sanyal et al. 2012). His thinking is commonly cited in conversations about what it means to be a planner (Fainstein et al. 2016; Fischler 2012; Sanyal et al. 2012), particularly in conversations about what core competencies professional schools should develop in their students (Fischler 2012). Reflective Practice has also become common parlance outside the field of planning, particularly in the field of education (teaching) and in institutions of higher education (particularly professional schools) (Fischler 2012). Informal conversations since beginning this project have led me to citations of reflective practice in contexts across the globe, from

the “Program Philosophy and Goals” of Antioch University’s PsyD program2 to Ireland Teaching Guild’s “National Framework for Teachers’ Learning.”3 While mapping Schön’s ideas about reflective practice as they spread across the globe and evolved would be a fascinating project, it is beyond the scope of this thesis. Instead, I will focus on how the idea has evolved within the field of planning, specifically at MIT DUSP.

Critiques within Planning

Despite the idea’s widespread discussion across many disciplines, McGill Professor Raphael Fischler asserts that, across the field of planning, the concept of reflective practice “is at once popular and marginal,” often referenced and yet rarely researched and only moderately practiced explicitly in the field by planners (2012 p. 313, p. 324). Fischler attributes this paradox to “problems inherent in that theory.” For one, it is both complex and vague. “Reflection-in-action” is neither intuitively understandable or easy to analyze empirically. It is also grounded in organizational theory and organizational behavior, but it focuses on individual behavior. The planning field in particular, Fischler asserts, prefers to think in terms of the systems of society, not within the bounds of organizational structure. In this way and others, Schön’s work is not speaking the language of planning, criticizing it without engaging fully (323). Fischler’s most poignant criticism is that Schön’s work was a theory of individual behavior, one that recognized the necessity of social processes for discovering insights but does not go far enough in acknowledging the impact of larger political, social, or economic forces on individual behavior. While Schön acknowledges that a professional’s “knowing-in-practice” is embedded in the “socially and institutionally structured context shared by a community of practitioners,” he does not speak about the ways individuals and professions are embedded in even larger systems, and he understands reflection as a largely personal act with the goal of increasing individual professional effectiveness (Schön 1987 p.33; Fischler 2012 p.323). Cornell Professor John Forester says it well, stating that Schön’s 2 https://www.antioch.edu/new-england/degrees-programs/psychology-degree/clinical-psychology-psyd/program-philosophy-goals/

assertions were “right . . . but not right enough” (Forester 2018). Forester calls for planners to understand themselves not just as Reflective Practitioners but as Deliberative Practitioners, working and learning with others (Forester 1999). He understands the theory of deliberative practice to be a model that builds upon the Deweyan “reflective pragmatism” articulated by Schön, Argyris, and others, and the dialogical learning model of Paolo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed. (p.130). Freire contends that the cultivation of knowledge is inexplicably linked to relationships of politics and power, and thus teaching should not be the delivery of knowledge from teacher to student but an act of co-creation. Action-science Professor Joseph Raelin also asserts that reflection must happen in community, as the self “is linked to the social communities that give it definition” (2001. p.16). Others take the critique a step further, understanding reflection not just as a tool to increase individual professional effectiveness, even while understanding that the professional is embedded in a larger social system, but is necessarily involved in a collective process with broader implications for social justice and social transformation (Amulya et al. 2005; Raelin 2001; Scharmer 2016). These later scholars and practitioners highlight the deliberative and communal nature of reflection. They understand “knowing-in-practice” and the processes of reflection in and on action belong not just to professionals, but to everyone. One example of these community and justice focused reflective practices is the Critical Moments Reflection.

Critical Moments Reflection

MIT DUSP Professor Ceasar McDowell’s Critical Moments Reflections represent one such social justice-oriented approach to reflective practice. Like the others, Ceasar and colleagues specifically cite Schön’s “reflection on action” as a baseline “powerful process for allowing people to become aware of the knowledge embedded in their actions” (Amulya et al. 2005 p.1). Critical Moments in particular was created not for professionals facing a “crisis in confidence” as defined by Schön, but for grassroots community organizations who, due to the “urgent and resource-strapped conditions surrounding community social

justice work,” often lack the time, resources, or intellectual frameworks to reflect on their “highly evolved frameworks of knowledge and theory” (Amulya et al. 2005 p.1). The tacit knowledge Schön calls “knowing-in-action,” Ceasar brings out by “helping people know what they know” (McDowell 2019). In contrast to Schön’s reflective practice, CMR is a process that, while promoting personal reflection, focuses on group reflection. It seeks to make an individual more effective by helping a community name, examine, and share the “highly evolved frameworks of knowledge and theory” that typically remain tacit and unexamined (Amulya et al. 2005 p.1). Ceasar, recognizing that many communities hold their collective knowledge in narrative and stories, created CMR to bring out these stories in full. Naming, examining, and sharing individual, organizational, and communal theories of practice not only improves individual and organizational effectiveness, the literature of Critical Moments Reflection asserts, it is also an essential tool for fostering the societal transformations social justice organizations seek to achieve. Critical Moments Reflection is a practice of “disruptive design and facilitation,” where disruptive refers to the “creation of environments that upset those stereotypes and habits of mind that limit one’s ability to be self-reflective, empathetic and open to change” (McDowell et al. 2005 p.30). In the article, “Building knowledge from the practice of local communities,” the authors assert that the Critical Moments methodology “has helped community practitioners develop the ability to incorporate more nuanced information, community wisdom, knowledge and personal experiences” into action and “strengthens the capacity to improvise and innovate during the process of community development itself” by “discouraging impulsive or simplistic theory building” (McDowell et al. 2005 p.31). This “greater consciousness and visibility of the learning generated from social change may be key to allowing practitioners to keep their work aligned with deeper democratic and justice principles” (Amulya 2004 p.2). For many organizations, this means becoming “self-conscious about their efforts to build inclusion and to explore obstacles to inclusion, particularly those that might be imbedded in painful racial histories” (Amulya & McDowell 2003). Thus, Ceasar McDowell has taken the notion of reflective practice and turned it into a community-scale learning system. Through MIT’s Center for Reflective Community Practice (now MIT Community Innovators Lab), he has been developing, performing, and

continuing to modify the Critical Moments Reflection process since 2001. The Critical Moments Reflection as a defining methodology has some variation in implementation. It is a process that has been used by individuals, groups, and groups of groups. The facilitators involved have adapted it to each context. It can be performed with varying degrees of depth, retrospectively or in real time, focused on one critical moment or on a long timeline of moments (Amulya 2004). Critical Moments Reflection theory diverges from Schön in one other key aspect. The word “emotion” does not appear even once in The Reflective Practitioner. Schön used the term “feel” in several places, but mostly as in “getting a feel for.” Schön’s reflection paradigm reflects on and in action and thought, and he does not discuss how emotion might play a role. Critical Moments, on the other hand, actively draws emotional responses into the conversation, using it as fuel and as a data point to draw out the knowledge embedded in actions.

Part II. The State of the Art at DUSP

Schön writes specifically about the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in several of his books. Most notably, in Educating the Reflective Practitioner, he gives an accounting of the shifting epistemological thinking in the department and tells the story of the MCP (Master in City Planning) Committee’s creation of the “Core Curriculum” (Schön 1987). Despite Schön and others’ efforts to subvert the standing of technical rationality as the dominant epistemology of professional planning practice, my experience at MIT over the past year and a half has shown me that technical rationality is still alive and well here. And yet, amidst technical rationality’s deep entrenchment, I also found a strong undercurrent of concern about reflective learning and practice in DUSP, stemming from both students and faculty. Reflective practices can be found tucked away in organized and informal activities, assignments, and groups. In the following sections, I have attempted to paint a detailed picture of DUSP’s current relationship with reflective practice. I have done it not merely through description but by laying out my process of implementing this research. The methods, process, results, and analysis are woven throughout this story.Chapter 3 The Intervention: Ceasar's Critical Moments

Reflections

Professor of Civic Design and Co-Chair of the MCP Committee Ceasar McDowell was one of the first faculty I approached when I returned to school in the Fall, and our conversations helped me begin to understand the context of my inquiries. Ceasar’s teaching, research, and professional practice focuses on the development of community knowledge systems and civic engagement. One of his primary tools is reflection, specifically in group reflective processes. Ceasar has been facilitating some of these reflections for different practicum over the years at the request of individual faculty. Near the end of Fallexercises with us. He adapted a version of the Leading Edge Questions exercise that’s part of the greater Critical Moments methodology, asking questions that prompted us all to write questions about our learning experience on notecards. After we collectively sorted the cards and discussed them, I looked at all the responses and thought, “Data!” These questions were an incredible insight into what students are interested in learning, what students need to learn, what resources would help us learn, and how practicum could be structured differently. I had taken part in a breakout group about practicum in a “DUSP Town Hall” event a few weeks prior, but what I saw on these notecards more than mirrored those conversations. The Town Hall format centered on a relatively abstract conversation held by those most willing to speak up. How much more compelling to see ideas drawn from a tangible experience and collectively generated. I met with Ceasar later that afternoon, and a half hour later we had the basic framework of the research intervention that would become this thesis. Ceasar generously agreed, if I could successfully organize it, to facilitate reflections in each practicum Spring semester. I would study the process and the results with the goal of gaining a deeper understanding of what reflective process means for this department, and how we can shape its future. Ceasar has referred to the Critical Moments Reflection as a form of “disruptive facilitation,” so it is appropriate that we staged these reflective events as the centerpiece of our intervention. This Spring, Ceasar and I worked together to systematically conduct reflective interventions in five of the seven practica. Given that the only institutionalized reference to “reflection” rests in the undefined reflection requirement for practicum, this seemed a good place to start. Ceasar adapted what is usually a two-and-a-half day Critical Moments Reflection intervention to fit the needs of the classes and this study. The following description of the process describes this adapted structure, which, while notably shorter than normal, covers the essentials. The first session, called the “Leading Edge Questions” exercise took place during the first month of the semester, after each practicum returned from January Independent Activities Period (IAP) fieldwork. While we had hoped to complete all the sessions during the first couple weeks of the semester, scheduling conflicts meant some took place in the

third or fourth weeks. The second reflective intervention occurred midway through the semester, just after Spring Break. In addition to observing these activities, I handled the logistics and occasionally facilitated. Each session ran about 90 minutes. While we tried to find one consistent and appropriate physical space, room calendars and other logistical constraints meant we often had to make do with what we had. On more than occasion, we brought a class out of a cavernous workshop space or cramped classroom to tape notecards onto large hallways. Table 1 - PARTICIPATING PRACTICA In the following two sections, I will describe in detail the processes of the two reflective processes - Leading Edge Questions and Critical Moments Reflection. I will

Course Name Faculty # students CMR1

Date # attended CMR2 Date # attended

11.312 San Pedro Practicum Engaging Community Ceasar McDowell 12 2/8 10-11:30 11 TBD N/A 11.304 InfraUrbanism: Designing a Resiliency Framework for Pellestrina Island Mary Anne Ocampo 9 2/9 10:30-12 8 4/10 9 11.S938 Integrating Informal Settlements: The Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area, Argentina Bish Sanyal 23 2/19 5:30-7pm 16 4/17 20 11.S943 Industrial Urbanism: Places of Production Eran Ben-Joseph 6 2/22 11-12:30 6 N/A (half semester class) N/A 11.439 Revitalizing Urban Main Streets, New Orleans Karl Seidman & Marie Law Adams 11 2/28 5:30-7pm 7 4/9 8

integrate these descriptions with my observations, and then I will provide some analysis gleaned from the sessions.

CMR I : Leading Edge Questions

Figure 1 – Students participating in Leading Edge Questions reflection

Ceasar designed the “Leading Edge Questions” process to help each practicum clarify learning and practice goals. Two underlying theories behind this are that students generate questions as they learn, and that those questions can remain tacit or unrecognized until drawn out through reflection. Thus, this process seeks to draw out the questions generated during IAP fieldwork, and to use those questions and that learning to frame the work of the upcoming semester.

In every session, Ceasar began by asking each student, professor, and teaching assistant to pen down a series of questions in response to the following prompt: “What is the question that, if you knew the answer to, would enhance your ability to meet the goals of this class?” A minute into this personal reflection, Ceasar requested someone offer an example to the group. He used this concrete example to lay out two guidelines. Namely, questions shouldn’t be unanswerable “God questions” like “Why is there suffering in the world?” or “what is the best possible way to do our work?” Similarly, he asked that questions be reasonably actionable during one semester. Thus, an appropriate question might be, “Who are the relevant stakeholders in the community we’re working in?” or “How should our class divide up the workflow?” After each individual answered for themselves, Ceasar asked everyone to use Sharpies to record their top five questions on 5” x 7” notecards (one class ended up with only three questions due to time constraints). Next, Ceasar guided the group through a process of grouping the cards into categories of “meta questions” -- capturing the full group’s answers to the original prompt. In most classes, this process happened with the entire class. One course, however, was 26 people, about double all other practica. For this class, Ceasar split the room in half at this point by project group. Two of the project groups went to one side of the big room with Ceasar, and two came to the other with me. Ceasar and I then conducted this next section in parallel, each facilitating for half the class. This twenty-six-person class was our third reflection, so I had already observed Ceasar guide the process through twice, and I had spent additional time discussing the underlying theory with him. I felt excited about the opportunity to try it out for myself. I also worried about it its effect on this study. Normative research protocol pulls me to hold as many variables constant as I can if I’m trying to measure before and after effects of an intervention. For most of the sessions, my role was to help Ceasar set up the meetings, and then to sit off to the side to observe and take notes and photos. I would troubleshoot when challenges arose, such as figuring out alternative spaces to use when the room proved unconducive to the exercise or taping cards onto the walls when time was running short, but my primary role remained observer of a process. Putting me in front of the room

represented a big disruption to that constancy and to my role as observer. However, we needed to fit a twenty-six-person reflection into an hour and a half, so I chose to step up. I thus found myself in front of a room of people, acting out the role I had previously been observing. At first, I harbored a certain researcher’s guilt at deviating from the norm. During the session and reflecting after, however, I began to understand my role differently. If the goal of a researcher is to reach deeper understandings of complex and messy circumstances by bringing curiosity and critical awareness to a field of study, then jumping into this active role enabled me to do just that. The view from the front of the classroom brought a whole new perspective and awareness. When I had been observing Ceasar, I often couldn’t quite keep up with how quickly everything was happening, especially during the initial categorization of questions. Trying to pick up on the threads of a class’s internal-facing conversations while paying attention to the active dynamics of the exercise, I found myself in awe of Ceasar’s ability to orchestrate these conversations. However, when I was the one standing in front of the room, my attention sharpened. I navigated the unfamiliar conversations with ease, knowing when to ask clarifying questions and when to trust the group’s flow. My own facilitation experience kicked in, and I felt like Schön’s tightrope walker, demonstrating a knowing-in-action I had been unable to access until I stepped into my own embodied practice. With Ceasar on the one side of the room and me on the other, we performed the second part of the reflection in parallel. I therefore was unable to observe what Ceasar was doing, but instead began to observe myself, to reflect-in-action. I followed the basic structure I had learned from Ceasar, beginning by asking someone to share one of their questions. After they read it, I taped that notecard up on the wall. Then I asked, “Does anyone have a question that’s similar to this one?” Someone else raised a hand and read their question, and I stuck that card up under the first one. The process continued in this way, drawing out related questions until there were no more and then starting a new column. I used some discretion here, occasionally giving a question someone offered a new category and providing a short reason why. Participants occasionally also piped up, saying something like, “I think your question is actually more like the question in the third

column,” or “Shouldn’t that be its own category?” I balanced listening and responding to these interjections while keeping the process moving quickly. Once each question had been taped to the wall, I asked everyone to stand up, come to the board, and move cards around to refine the categorization. The one rule was that anyone could move a card, but they had to state out loud their reasoning. I stepped back and allowed this process of group deliberation and storytelling to unfold. I noticed people in my group turning to me as they spoke, perhaps implicitly asking my permission as they moved cards, as opposed to taking initiative or looking to each other. I thus decided to visually remove myself from the process, stepping behind the group and out of eyesight. At this point, I found Ceasar had done the same, so we met up to confer about how it had been going and how we should time the rest of the session. We decided that for the final stage, Ceasar would bring the whole group back together. Interesting group dynamics also emerged in other practica at this stage of self-organization to categorize questions. Most of the time, the group would start all together, but at some point would break into clusters as multiple people moved cards at once. They all returned to a full group for the last review. Sometimes people would move cards by doing what Ceasar said, stating why they were moving the cards. Other times, people would not state but would ask those around them if they could move the cards, saying something like, “I think we should move this card to this category because . . . what do you think?” One class in particular did this questioning almost exclusively, looking to each other to collectively decide. This class also had most of the conversation as one class, instead of breaking into groups. The exception was a period in which a student who wasn’t in the class came in and began speaking loudly to the TA. The noise changed the space, and I noticed at this point that the deliberation process split into two groups, perhaps so people could better hear each other. When Ceasar asked the other student to take the conversation outside, the class slowly folded back into one conversation, and continued their process of consensus-based deliberation.

This was a class that had all pitched in to bring breakfast that morning and told me they had committed to all sharing food every week. From the moment I walked in, I noticed an ease and comfort to the group’s dynamic not present in all classes. I believe this trusting and positive group dynamic is connected to a feeling of collective value and respect that led to this group asking as they moved cards instead of stating. While I might have expected this process of asking to be less efficient than stating, it was not the case. After the group categorization, Ceasar gave one final task. He split the class into sections and asked each to take a chunk of the columns and write on a new notecard the “meta question” that all the cards in the column were asking. For example, a column with questions like, “Who is invested in the outcome of this process?” and “Which groups are currently in opposition?” might generate the meta-question, “Who are all the stakeholders?” Figure 2 shows one example. Once each group had written their meta question on the card and taped that to the top of each column, the activity was over. Everyone returned to their seats. In Table 2 below, I categorized the 42 total meta questions generated by the four different classes into 9 questions I believe capture the essence of the questioning and learning of the practica. See Table 2 below for the Meta Categories and questions, and see Appendix 5 for the full list of all 42 questions by class. Figure 2 - a meta-category

Table 2 - Categories of Meta Questions CATEGORIES OF META QUESTIONS Numbers represent frequency of each category across the 42 total questions found in Appendix 5 Code and Frequency Example Stakeholders (13) Who are stakeholders (in addition to the client), and what are their interests? Data Gathering (10) What data and knowable info do we need to gather and where can we find it? Deliverables (4) What will be the content and audience of our deliverables?

Positionality/Ethics (4) What are our interests? How do we responsibly engage the community as outsiders? What values are we bringing? Best Practices/Cases (3) What are the relevant best practices and what has been done elsewhere? Class dynamics (3) How do we work effectively as a team? Client interests (2) What does our client want? Capacity (2) What capacity does the community/client have to implement a plan? Metrics for success (1) How do we measure our progress and evaluate our work? Ceasar concluded by saying that the aim of this activity was to use these collectively-generated meta questions to create an action plan and group structure for the semester. For example, the question ,“What is the context of the Island historically, environmentally, culturally, and regionally?” could be assigned to a sub-set of students, who could then review relevant literature required to answer the question. Subsequent interviews and surveys I conducted revealed the extent to which this directive had been taken up by classes, and the extent to which the questions and conversations generated by the reflections effected the course of each practicum.

Analysis of Leading Edge Questions Reflection

Demonstrated Value of the Reflection

Performing and observing this first round of reflections in four practica highlighted many ways these reflections provide otherwise missing opportunities for individual and group reflection and learning in class. The method of prompting students to ask questions

of openness and curiosity and shifted the inquiry from one of technical problem solving to, in the words of Schön, problem-setting. By successfully implementing the CMR’s stated goals of facilitating individual and group reflection to help people know what they know through asking questions, classes collectively and deliberatively created a shared intellectual framework that proved an asset to projects. Without these reflections, knowledge doesn’t just go unexamined, it often doesn’t even get recognized and named. One student, looking at the columns of questions, exclaimed, “we have some big questions I didn’t know we have, like, ‘what is our purpose?!’” She added that even if the group wouldn’t be able to fully find answers, they should have a longer conversation about them. In this way, the reflections effectively do, as their theory states, help people “know what they know,” and then generate new actions and knowledge as a result. This active process of problem-framing also has often overlooked value. As one student from the Media Lab shared at the end of a reflection, “we solve non-existing problems in the Media Lab because we don’t ever do this process.” Without a time specifically set aside for slowing down and deliberately looking back at what happened and forward at the goals of the course, individuals and groups often get caught up in cascades of tasks. This can lead to losing sight of the bigger picture and missing opportunities for learning. Dedicating time to problem-framing is not a common practice in group work, yet it allows for a critical examination of the assumptions behind the work. The invitation to air questions can bring those assumptions forth, allowing groups to distinguish between what they do and don’t know in order to make informed decisions in the face of the “complexity, uncertainty, instability, uniqueness, and value conflict” of real practice (Schön 1983 p.18). Additionally, the process of reflecting individually by generating a list of questions, and then categorizing and naming those categories as a group, makes this process a truly deliberative one, one that harnesses individual knowledge and cultivates group knowledge. In most class and project settings, those with the loudest voice often end up with the largest influence, and contesting opinions do not always fit in to conversations. In these processes, where each person is given a few opportunities to speak, every participant is equal and active, and the confluence of perspectives allows for more complex and multi-dimensional analyses to emerge.

Different practica used the resulting set of meta questions in different ways. Surveys and interviews elucidated the extent to which each class incorporated the leading edge questions into their practice. From the reflection sessions alone, however, it was clear to me from the level of critical engagement and interest of every participant, and from comments made throughout, that these conversations provided valuable time to deliberatively align the classes’ understandings of the problem and what is necessary to tackle it. The analysis after the following description of the second reflection further illuminates the positive effects of both these reflections.

Insights from the Reflections

The similarities across each group’s meta questions proved one of the more

interesting findings from this reflection. As shown in Table 2 above, many common themes emerged across the classes. Most notably, questions of how to identify and understand the needs of all stakeholders, finding data and information, the content and function of the final deliverable, and positionality and ethics played most strongly across all practica’s reflections. The emergence of similar themes across each of the practica support my hypothesis that these questions represent an incredible insight into what students are interested in learning, what students need to learn, what resources would help us learn, and how practicum could be structured differently. Survey and interview data, discussed in later chapters, will further support my recommendation that DUSP develop methodological and pedagogical approaches to helping students develop and practice their own theories of practice around stakeholder engagement, data, deliverables, and ethics and positionality.

CMR II: Critical Moments Reflection

Midway through the semester, we returned to several practica to conduct the namesake process of the whole theory, the Critical Moments Reflection. These happened after Spring break, between April 9th and 15th. Each participant took ten notecards and a sharpie and wrote critical moments that occurred during the practicum. We showed an image of Figure 4 to demonstrate the formatting of each card. The definition of a critical moment was left broad; it can be an “aha!” moment, a downturn, an upturn, or some other shift (Amulya & McDowell 2003 p.4). Each person then indicated whether the moment led to a good, bad, or neutral outcome. Ceasar noted to each class that it is important people think about the positive, negative, or neutral emotional tone of each moment both at the moment it happened and in terms of their own experience. Some moments can feel bad in

the moment but then later can prove a valuable and positive learning experience. For this exercise, participants are directed to capture the feeling as the moment happened. It’s also important for each individual to consider their own experience, not try to figure out how the moment felt for everyone but to focus on their own reaction. The theory behind these instructions is that insights can be learned through emotions, but that in professional and academic contexts, we often need to explicitly and systematically welcome in the emotional side of our experiences. Once each person had approximately ten cards, Ceasar asked everyone to put a star in the top right on their three most significant cards, and then stand up and come to the side of the room (or in a couple cases, the hallway) in which I had taped a long horizontal line of blue tape punctuated by small vertical pieces of tape and labeled by month. This was a timeline, starting in the months leading up to the practicum and continuing to the present. Each person was tasked with taping up their cards in their proper chronological location along the line, with positive moments above the line, neutral moments on the line, and negative moments below. Really positive moments went really high, and really negative went really low. When every card had found its place, the group stepped back and looked at the visual display of moments ordered by time and feeling. “What do you see?” Ceasar asked. Different voices piped up, noticing patterns like “there are more positives overall than negatives,” and “there’s a heavy concentration of cards in January,” and, “cards tapered off in these last few weeks.” After overall patterns had been established, we zeroed in on individual moments. Ceasar scanned the timeline from left to right, stopping at each Figure 4 – example of CMR card format

they had written and why. Some individuals, more in some classes than others, took to heart Ceasar’s earlier directive to name the moments in fun and funny ways, names like “Tear it Down!” and “wet feet.” This gave this process some lightness and laughter. A favorite of mine was “Reflection #1,” referring to our Leading Edge Questions reflection two months prior. Everyone was given chances to speak, and I noticed in every class that everyone else listened attentively. In the first couple classes, people chose only critical moments directly related to the project. In our third reflection, someone wrote “Mom’s 1st birthday,” and shared that this moment marked a year after her mom received a transplant. It was an emotional and critical moment for her that affected how she showed up in the group, and so she believed it appropriate to include. Still, she felt self-conscious about being the only one to share something so personal. Ceasar assured her she was right on for recognizing the connection between our personal lives and our work, and the tension that arises from often not being able to recognize both in one space. He then told a story to the group to illustrate this point. In the reflection with the next class, he made a specific point to emphasize the value of bringing more emotional and personal critical moments into the exercise, and he told this story at the beginning to illustrate. Several years ago, conducting this exercise for a group in Honduras, Ceasar noticed, at the moment everyone stepped back to look for big picture patterns, that a large swath right in the middle of the timeline was curiously sparse. He asked the group for their observations, and nobody brought up the near-empty space. Finally, he asked directly. There was a pause, and then the head of the program manager spoke up. “That,” he said, “that’s when I started drinking again.” This opened up a conversation about his process and his recovery, and for Ceasar it highlight how much what is happening in our lives can inform our work, and the value of creating space to explore those connections. Figure 5 – CMR moment referencing the first reflection!

For this last class in which Ceasar specifically emphasized this point in the beginning and reiterated several times that people should bring their emotional

experiences into the space, the timeline and resulting conversation included many more personal and social experiences. One woman, a

SPURS Fellow living across the ocean from her family, put a card, seen in Figure 6, below the timeline called “Night calls from family” and shared that many nights she wakes up in the middle of the night to receive calls from her daughter. This leaves her emotionally and physically tired, which can make it challenging to always show up fully to the group work. Some of the most generative moments of the reflection happened when two people wrote the same moment but placed them on different sides of the emotional scale. In one class, a faculty shared a moment from fieldwork, “Community Books” in which a bookstore owner described the behaviors of white people moving into the neighborhood, and the discomfort the faculty felt realizing that the she and the class were in many ways exhibiting those behaviors. Ceasar asked how she’d processed that. “It made me a little bit nervous about what our role was in the project.” A student piped up: “I put up that same moment,” but I experienced it differently, so I called it ‘coffee cup drive-bys’ because she was talking about how people just pop in with their coffees and don’t really feed her store but are just assessing it for what it could be . . . I saw people feel that, so people even put their coffee cups down. . . and there was also this weird thing that was happening, I don’t know why, but all the black people were on one side of the room, including myself, and so it was kind of comical to me. That whole moment was really weird, but it made me happy it happened because it made me think about how to center what she was saying as part of the work we’re doing.” Several others moments throughout this class’s timeline addressed these issues of positionality, of what role the group plays as outsiders in the community, and of how racial

broadcast a community member asking a student why he should trust her to facilitate a community meeting: “I don’t know who you are, where you’re from or what your last name is,” he'd said. She’d responded that those were valid concerns, and that she had been feeling them, as well, that everyone in the class shared those concerns. This moment had stayed with her in an uncomfortable way, and she wasn’t clear on the best way to incorporate its lessons into her work. After the run through of the timeline, Ceasar asked if anyone had anything they wanted to make sure the class spent more time addressing after this reflection ended, a student stated, and other echoed approval, that she wants to have a more formal, integrated conversations about the “parts around the process that people are struggling with” specifically around racial dynamics. She shared that these conversations have been happening, but only in one-on-one settings, which, as one of the few people of color in the class, she felt often put the burden on her to have so many individual conversations. Someone else seconded that, adding that it’s even more critical now that the class has entered the ideation stage, and they shouldn’t “assume people are thinking about these issues. It has to be an integrated part of our process.” The faculty agreed to find time to formally address these issues as a class.

Analysis of Critical Moments Reflections

Demonstrated Value of the Reflections

About two weeks after the final reflection, one of the participants approached me in the hallway and let me know the class had had just circled back and had a conversation about positionality and race in their project. It hadn’t been easy to make time – a couple of the students had to push several times. But, as a direct result of the CMR, they were mobilized, and they worked to create the space to collectively begin working through tough issues.

This was not the only class to begin approaching previously avoided conversations during and after the reflections. While this was particularly prevalent in the Critical Moments, it also presented as a theme in Leading Edge Questions. As observing these conversations made clear, and as later survey and interview comments would support, DUSP students find great value in these conversations and crave more of them. In this sense, the CMRs provide otherwise missing spaces for reflection and learning in DUSP. I believe there are several reasons why both the Leading Edge and the Critical Moments Reflections draw out conversations that class and workshop structures often stifle. The emphasis on emotion and social experience, the big picture lens and encouragement of voicing differences, and outsider facilitation lend themselves to these Figure 7 - students, TAs, and faculty creating a shared timeline in the CMR

The second reflections put a particular emphasis on emotion, on noticing and naming if a moment felt positive, negative, or neutral for each individual. Emotion is often considered an unwelcome element in a professional or class setting. This process recognizes the inevitable dimension of emotion in any setting and legitimizes it expressions, both in the context of the class and more generally as part of practice. The underlying theory is that there is a kind of knowing in the emotion, and recognizing and constructively drawing that out will help the individuals and groups learn and reach their goals. Having everyone participate by naming discussing emotion helps makes this a social, and therefore engaging, activity. While I expect to see at least a couple students looking down at their phones or zoning out with their laptops in any given class, these reflections held the group’s attention. About once a class, in slower moments, someone would step back, pull out their phone, and disengage for a minute. Otherwise, eye contact, body language, engaging conversations, and intermittent laughter made it clear that people were paying attention to each other throughout. Whole-class attention and engagement is a huge value add of these reflections. The reflections in many regards succeeded in bringing emotion into the conversation, which had a positive effect on the overall process and results. Near the end of the class reflection described above that kept coming back to positionality, Ceasar asked if anyone had other moments they want to share, and what take-aways the group had. Student responses centered around emotions, and they very effectively used these emotions to make and support their points. A couple students shared that hearing others express these concerns about positionality, especially the faculty, and then also realizing that these are the same concerns the community shares, felt refreshing and validating, and that they hope bringing them into the open ensures the issues are addressed properly in the content and process of the project. Two students then shared that, indeed, the class suffered from a lack of open conversation and feedback that makes these classes difficult, and that as the workload picked up, it became harder to try to address this issue. One added, “I feel disappointed and sad about that.” Someone else said, “When we do have discussions in class, there are often long silences that make me feel really uncomfortable.” Trying to diagnose why, she attributed this both to the discomfort of racial dynamics not

being discussed and because “this program [DUSP] in general sometimes makes people feel less confident in talking and saying that they think something’s right.” Students used their emotions as data, and, by naming and sharing them, they collectively were able to learn from their experiences and take active steps to align their values and desires with their actions. Placing each moment in the broader context of the class by using them as building blocks for a timeline visually draws a wide lens for the reflections. Looking at the project as a whole encourages noticing patterns and other broader implications – such as ethics - which can be missed in normal day-to-day task management that often dominates class time. This combined with permission to share emotion and to disagree with others, allowed for bigger questions and conversations to present themselves throughout both first and second round reflections. In Leading Edge Questions, meta questions like “How do we responsibility engage the community as outsiders?” and “How do we be good planners?” arose in each class, and resulting discussions several times dipped into even bigger questions of the very nature of many of the practica as outsider, temporary interventions and of discomfort at playing the role of “expert.” In one class, a SPURS Fellow, started with “since you are encouraging us to get into the contestation,” and then shared that as a planner in India, “if a bunch of foreign nationals would have come for one week and come up with a plan, I would have protested,” and yet here she found herself reversing roles as part of this practicum. The class, she asserted, hadn’t been talking enough about the implications of their actions and their role. Students, unaware they had the questions, constrained by time, feeling uncomfortable breaching tough conversations, hadn’t been having the conversations they thought were important for their learning and practice. When the reflections created a safe space to disagree and time and space to paint the big picture, participants opened up, and in doing so explicitly stated their desires to spend more time collectively exploring these important questions. At this point, the faculty spoke up, agreeing that it is an important conversation, and committing to making more time for class reflection, if Ceasar and I could come back. Here again, these reflections led to productive next steps.

Ceasar’s and my role as outsiders also proved valuable. Explaining an insider situation and dynamics to an outsider requires perspective-shifting, which can create some space for insight. Faculty or students shared their moments with significantly more detail than they would if they were just speaking with each other. Often, someone would read the title of their moment, and the class would burst our laughing or nod in ways that demonstrated understanding. Because Ceasar and I didn’t understand, however, the participant would then have to explain the moment in more detail. This would sometimes surface differing understandings of the moment, such as the dual narratives of the “coffee cup drive-bys” moment described in the last section. Additionally, I noticed many times that someone shared a potentially contentious or challenging opinion while looking directly at Ceasar, instead of at the faculty or classmates. It can feel less adversarial to share something to an outsider in response to a prompt than to spontaneously bring up a tough issue in class. The “coffee cup drive-bys” class had set aside unstructured moments for reflection in class, but these tougher feelings and issues had not arisen. In a later interview with one of the faculty, he shared that he believes the fact that he was participating as an equal – not as a facilitator of the discussion - and that students have a certain rapport with Ceasar allowed these conversations to surface. Here again, outsider facilitation can help surface important conversations.

Insights from the Reflections

The similarities, and a couple key differences, across patterns in each group’s critical moments proved one of the more interesting findings from this reflection. As shown in Table 3 below, common themes emerged across each session.

Table 3 – CATEGORIES OF CRITICAL MOMENTS with frequency and percentage of total moments per class

Client/Site Class/Assignments Social Personal

Class 1 47 (87%) 4 (7%) 3 (6%) 0 Class 2 43 (47%) 45 (49%) 3 (3%) 0 Class 3 36 (40%) 22 (24%) 20 (22%) 12 (13%) Class 4 42 (43%) 48 (49%) 4 (4%) 3 (3%) This table shows the frequencies of categories of critical moments from each class’s timeline, organized by four categories. Whether positive, negative, or neutral, each represents a learning moment, and the particular distribution of these moments has implications for how we understand practicum. “Client/Site” refers to critical moments of direct contact with the client (including Skype meetings) or during fieldwork. This includes moments like “conducting business surveys – putting faces to business names” and “seeing the site for the first time – the scale, magnitude.” The heavy concentration of critical moments from direct interactions with clients, community, and location represent a hefty proportion of the critical moments of each class. As interviews and surveys will also elucidate, students find these moments incredibly valuable, and yet the physical distance and time constraints limit these interactions. “Class/Assignments” are moments that took place in class or while doing assignments, such as “sorting hat: initial teams + roles,” or “roaming Google street-view.” Moments called, “First Reflection Session” and “Reflection #1!” referring to the Leading Edge Questions session, also went into this category. I was pleased to notice that of the three classes doing the second reflection that had also doing the first, at least one critical moment card per class referred positively to the first reflection, and that these cards were written by both faculty and students. This provides one more data point in support of the value of the Leading Edge Questions reflections.