HAL Id: halshs-03219259

https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03219259

Submitted on 6 May 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Revising European governance toward capability and

human rights-based benchmarking and allowing voices of

stakeholders to be heard in social investment

Alexis Jeamet, Robert Salais

To cite this version:

Alexis Jeamet, Robert Salais. Revising European governance toward capability and human rights-based benchmarking and allowing voices of stakeholders to be heard in social investment. [Research Report] IDHES. 2019. �halshs-03219259�

Revising European

governance toward

capability and human

rights-based benchmarking

and allowing voices of

stakeholders to be heard in

social investment

Report WP7. 3 - 4

Alexis Jeamet & Robert Salais

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 649447

Revising European

governance toward

capability and human

rights-based

benchmarking and

allowing voices of

stakeholders to be

heard in social

investment

Report Package 7. 3 - 4

This report constitutes Deliverable x ‘xxx’, for Work Package x of the RE-InVEST project.

Type the month and year

© Type the year–RE-INVEST,Rebuilding an Inclusive, Value-based Europe of Solidarity and Trust through Social Investments – project number 649447

General contact: info@re-invest.eu p.a. RE-InVEST

HIVA - Research Institute for Work and Society Parkstraat 47 box 5300, 3000 LEUVEN, Belgium

For more information type the e-mail address of the corresponding author

Please refer to this publication as follows:

Type the bibliographical reference of the publication

Information may be quoted provided the source is stated accurately and clearly. This publication is also available via http://www.re-invest.eu/

This publication is part of the RE-InVEST project, this project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 649447.

The information and views set out in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein.

5

Contents

List of figures 6

Introduction 7

1. The past that obstructs the European vision 9 2. What domains are eligible for a social investment approach? 11

2.1 Freedom of movement of people and structural funds 11

2.2 Social and environmental components of firms’ investment 12

2.3 Investment in the building of social infrastructure 15

2.4 Reforming social policies and schemes and developing new ones in terms of social

investment 18

2.4.1 Is social investment basically an investment like any other, the only difference

being that its content is social and not economic or financial? 18

2.4.2 Or does social investment mean investing in the social? The social, by essence,

concerns society as a whole, people and citizens insofar as they are the collective

and individual living targets. 20

3. Challenging social impact-based governance: implementing the

capability-human rights approach (CHRA) in social investment 21

3.1 From “evidence” to social impact measurement: the case of social impact bonds (SIB) 23

3.1.1 Enlarging the European definition of social enterprises 23

3.1.2 Achieving measurable, positive social impacts as primary objective to justify profit 25

3.1.3 The politics of evidence as applied to social impact measurement 26

3.1.4 What does “evidence” mean? 26

3.1.5 The Open Method of Coordination (OMC) 27

3.1.6 At the edge of financial innovation: Social Impact Bonds (SIB) 30

3.2 The Capability-Human Rights Approach (CHRA) to investment in the social dimension 32

3.2.1 Main specificities 32

3.2.2 The dynamics of Capability-Human Rights Approach (CHRA) implementation. The

deliberative process 34

3.2.3 Is it possible to correct the social impact methodology using capability-human

rights methodology? 36

3.2.4 Reading the WP6s outcomes with the glasses of the CAHR implementation as

above defined 38

3.3 Introducing a capability humain right management (CAHRM) into social services and

institutions 40

3.3.1 The benchmarking 42

3.3.2 The deliberative process 42

3.3.3 The inquiry about capabilities 43

3.3.4 Revising the means: the return of experience 43

3.3.5 Comparing outcomes of the two approaches, the quantitive performance impact

and the capability-human rights impact 43

4. Conclusion 44

6

List of figures

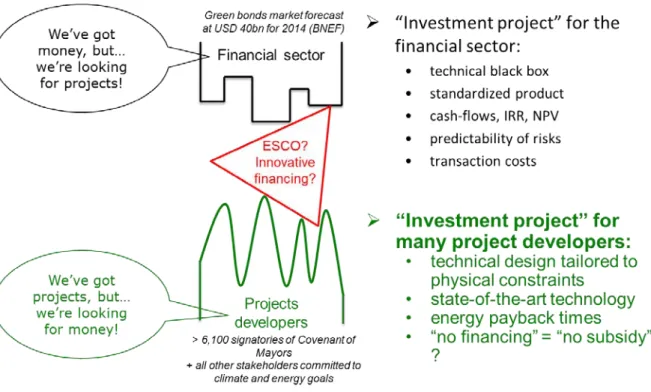

Figure 1 : Finance and sustainable energy. Trying to match squares and circles 19

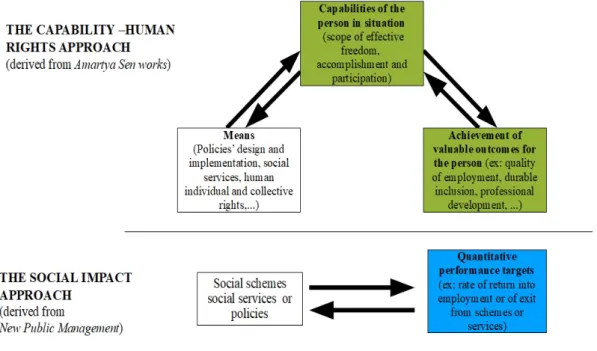

Figure 2 : Two conceptions of the relationship between social policy and evaluation – Improving the

power of conversion of means into achievement of valuable outcomes 22

Figure 3 : A guideline and its indicator 29

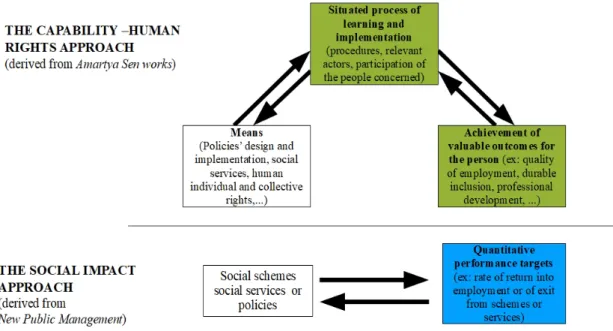

Figure 4 : Two conceptions for implementing social policy – Favouring a situated process of learning

throught open deliberative precedures 34

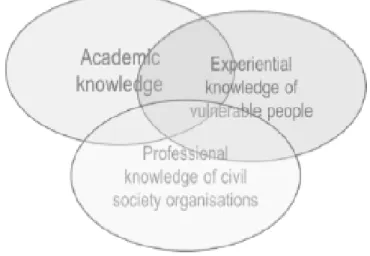

Figure 5 : Quotations from interviewee’s voices in WP6 national monographs. A sample 39

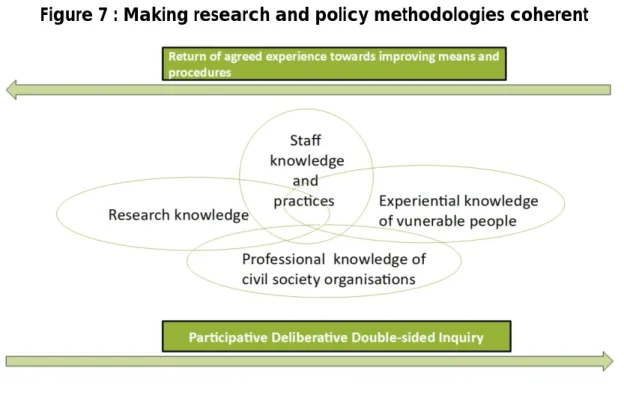

Figure 6 ; Reminding the PAHRCA methodology: merging knowledge 40

7

Introduction

The outlook for our future is not brilliant – we are facing threats of which we were not truly aware at the beginning of our RE-InVEST project, in particular the warming of our planet and all its consequences on the lives and well-being of Europeans, not to mention humanity. It becomes evident that social and the environmental issues go hand in hand. Environmental changes have had and will continue to have dramatic consequences for the quality of life, hence for social conditions. Poor people are too often deprived of the means and security in their daily lives to take care of their environment. They also work in poor social and environmental conditions. Billions and billions must be invested in well designed action and financed according to criteria for fighting global warning and supporting social conditions in relation with human development. This action must no longer separate environmental issues from social issues, nor focus on environmental damage while ignoring measures for improvement. A vital commitment to massive investments in the social and the environmental domains, and their interdependence, is the chance for the European Union to come out of the current crisis on top and to implement a new model for the economy and society. We hesitate to write “would have been”. In any case this is our only chance, and it is not too late. The vision outlined in this Report is much more modest, a timid and small opening towards our less-than-brilliant future. It is worth noting that we face vital crises for which Europe is unprepared, and in which social conditions and their close relationship to environmental issues are major components.

This said, in this Report 7.3-4 we focus primarily on the existing program of RE-InVEST in its non standard macroeconomic aspects.1 How can a capability-human rights approach (CHRA) be implemented in a European social policy environment marked by the concept of social impact? This work is macroeconomic in that it addresses the core issue of aggregating from the particular to the global individual, collective and national situations that are, by essence, heterogeneous and not comparable. Macroeconomics and the market work with macro aggregated data. Social investments as conceived by the European institutions are based on standardization, seeking the simplest way to aggregate situations, indicators, tools and policies and, in the end, individuals themselves. The reason for this is simple: it opens the way for a social investment market. In our analysis, we demonstrate our scepticism and propose another pathway based on CHRA, that we call “investing in the social”. Would it be possible to introduce CHRA in the social impact approach? In other terms, is-it possible to mix market and non market logics?

This Report comprises three parts and a conclusion. The first part gives a brief diagnosis of the difficulties that obstruct the European vision of our future.2 The second part lists four issues that are eligible to a social investment approach, as we envision it. Only the last three issues are discussed here: the social and environmental components of corporate investment;

1 The close connection between the two issues – governance and voices of stakeholders in social investment – has led us to draft a joint report covering the two together.

2 For a detailed diagnosis based on the history of the European Union readers are referred to Salais R. (2013), Le viol d’Europe. Enquête sur la disparition d’une idée, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France

8

investment in the building of social infrastructures; challenging governance based on social impact by implementing the capability-human rights approach in social investments (the longest one). The third part develops the challenging of the social impact-based approach by the implementing the capability-human rights approach.

9

1. The past that obstructs the European vision

Unfortunately, the EU has largely missed the point on these matters. Its conception had neither long-term vision, nor ambition; it is a short-term, mostly regressive and purely market conception framed in a perspective of austerity and of reducing public expenses. Many national monographs3 on the provision of social services mention these underlying trends that continue today and speak, not only of investment, but also of disinvestment in the social domain. Textual analysis of the EC Communication4 “Towards Social Investment for Growth and Cohesion – including implementing the European Social Fund 2014-2020”, only 19 pages long, reveals the obsessional use of seven keywords which have almost nothing to do with social matters, but belong to management and financial domains. They generally function in pairs: ‘efficiency’ (19 occurrences) and ‘effectiveness’ (19 occurrences too); ‘sustainability’, mostly financial (21 occurrences) and ‘adequacy’ (21 occurrences too, and up to 26 if one counts synonyms); the champion keyword is ‘target’, in its diverse modalities (28 occurrences, up to 37 if one adds ‘conditionality’ (9 occurrences)); ‘monitoring’ (strictly 15 occurrences, much more if one adds all the related notions, such as ‘governance’, ‘steering’, ‘guidance’, ‘reporting’, ‘support’).5

Although a tension between this obsessional approach and another approach oriented towards human capital development through education, child care and training appears in the text, such a focus on these keywords engenders the feelings that the main orientation that the European authorities suggest for social policies and welfare reforms is regressive: not extending, and even reducing public budgets devoted to social matters by all possible means. There is no trace of expressions such as ‘social justice’ or ‘struggling against inequalities’ that would have indicated concerns other than efficiency. The keywords and the entire text trace the proper ways to achieve efficiency, ways that European authorities intend to monitor through political methodologies derived from the Open Method of Coordination (OMC), an application of NPM technologies – “that has contributed to steering Member States’ structural reforms in the areas of social protection and social inclusion”6 , i.e. a mix of governance by quantitative performance and diffusion of best practices among countries.

The attempt to employ the notion of capability in the EC Communication falls short; it reveals that the authors know next to nothing about the capability approach, one source of inspiration for RE-InVEST. “If a person can temporarily not find work, the focus should be on improving their capabilities with a view to them returning to the labour market. This needs to be done through a targeted approach focused on the individual needs and delivered in the most cost-effective7 way”8.

3 See the WP6 Final Reports. 4 Called COM/2013/083 below.

5 For each keyword, we add all the modalities. 6 COM/2013, p. 1.

7 Cost-effective is in French a false cognate. For it means “the most beneficial in terms of cost”. 8 COM/2013/083, p. 7.

10

As we will see below (Part 3), targeting and delivering services in the most cost-effective way is not the right way to develop a capability-human rights approach. For this approach, the priority is social efficiency, not financial efficiency.9 The latter (financial efficiency) should proceed from the former (social efficiency). The priority is not to minimize the cost, but to build help for people, by starting, not from their “needs” (a word related to a poverty approach), but from the primary features of their situation, their effective freedom to choose and the conversion factors that impede such freedom. It means considering the functionings that are the most important for the person and how to achieve them. Democratic participation of people in the deliberation on the best choice and the outcome evaluation are also pillars of the capability approach.

One cannot neglect the search for efficiency in social expenditure, as for other types of expenditure. However, how should we judge the effectiveness and efficiency of social services and their evolution, with regards to whom and by whom? For the European Commission, effectiveness and efficiency are evaluated only by the managers of the social schemes; and they are measured by maximizing the score and minimizing the cost.

In a truly social evaluation (as in a capability and human-rights approach), by contrast, the gain must be appreciated by the real improvement or deterioration of the social situation of the people entering the scheme. Such evaluation is in general not financial. It is made by comparing the situation of the people when entering the scheme and their situation after their exit. And it should implicate the people, who must participate in the evaluation, because their experience needs to be confronted with the administrative data. To avoid biases or premature conclusions, observations should be made some time after the date of exit. Due to the pressure to increase quantitative performance, some people are considered as included as soon as they can be excluded from the register of the institution (such as employment offices or health institutions). But they often return, because it is a false inclusion or health recovery leading to a short and precarious exit only. Such phenomena that artificially increase scores are now well known.

We have written above that the “main approach” is regressive; there are some exceptions, however, notably regarding investment in social infrastructure. Will the future European Commission and national states do better? Will they try to take an ambitious long-run approach and to resolutely implement it?

It remains that, due to the narrowness of the Agenda 2020, RE-InVEST itself risks to be locked into the regressive conception of social matters that was still predominant when we prepared its research agenda; the most striking feature is the absence of links between social and environmental issues10 and consequently the lack reflection on what this connection means for the economy.

We have tried to extract ourselves from this negative framework, however and to oppose to it another conception of social matters that is more open to the future: a capability-human rights approach developed from the work of Amartya Sen and other researchers. The aim here

9 Our underlining.

10 It is worth noting that in the Manifesto Another Europe is possible for a fair distribution. An urgent call for a social, democratic and sustainable Europe (Alliance to fight poverty, Brussels, 2014) in the preparation of which some of us participated, the authors were well aware of the challenges and the link to make between these issues. We quote: “A renewed project for Europe has to reconnect its economic priorities to answer social, ecological and climatic challenges… Through strong and innovative politics, the EU can develop the potentialities of each country and region to stimulate an equal standard of living” (p. 8).

11

is to suggest (this is not the setting for a demonstration) that such an approach has the capacity to develop another conception of social investment and of its governance. Some people criticize the social investment approach for opening the way to funding of social objectives by private capital; they fear it will introduce profitability requirements in the field and distort the very nature of social policies. There are indeed some risks involved, not so much in opening up to the private sector, but rather in governance methods based primarily on performance by numbers. Participation of the people who are supposed to benefit, of stakeholders or a set of actors beyond those of capital and public administration are absent. The involvement and empowerment of people are not the objects of European regulations. And the concept of participation is not expanded to include that of deliberation.

2. What domains are eligible for a social investment

approach?

Re-InVEST has invested mostly in social policies in the strict sense of social schemes or classical categorized social domains such as social protection as revisited through active labour market policies or social services (such as early childhood education, housing, mental health care). These are important. But one must not forget that they are only part of a series of wider fields eligible to a social investment approach. In our view one should include:

- The link between freedom of movement of people and structural funds investing in vulnerable and underdeveloped European regions or countries;

- Social and environmental components of firms’ investment; - Investment in the building of social infrastructure;

- And lastly, reforming existing social policies and schemes and developing new ones in terms of social investment.

2.1 Freedom of movement of people and structural funds

Freedom of movement of people is one of the basic foundations of the European Union. What appears after years of implementation is that outcomes are not always positive, but mainly negative for the economic development of vulnerable regions and countries, especially for eastern European countries. A key illustration is Romania. Since the Enlargement of Europe in 2004, the skilled workforce and educated young people have been leaving Romania and fleeing to developed countries in the EU – France, Britain, Germany, and so on. Romania has been obliged to import workers from India, Pakistan and other Asian countries. What may be good for business is not so good for Europe. It has degraded the European labour marked, pulling it down towards precariousness and low wages. What may be perhaps good for migrant workers and host countries is bad for Romania that has lost key resources for development. What is missing in European policies and funding is the aim to fund investments in these countries,

12

firstly to develop capacities of production and of exportation and the corresponding infrastructure, secondly to target the social objective of developing the capabilities of people and orienting them toward improving their real freedom to stay in their country or not (that is, having enough real opportunities to find a good job and life at home, when compared to western Europe).11

2.2 Social and environmental components of firms’ investment

Macroeconomic policies and market-based arrangements are in themselves dramatically insufficient. They are not concretely designed to efficiently combat global warming and to reduce the environmental footprint. They have perverse side effects, increasing social inequalities (in the case of ‘green’ taxes) or simply moving polluting industries to poor countries (in the case of emissions trading schemes).12 Social damage is increased, instead of being prevented from the start thanks to social and environmentally friendly investment. The environmental footprint must be thought in terms of strong sustainability, that is starting from the objective that production should give back at least as much as it extracts from the environment, as opposed to weak sustainability as is mostly the case today in European policies. The perspective should be to implement policies that see nature as a resource, even as a heritage, complementary to and not replaceable by labour and capital. Polices should ensure that resources are renewed at least at the same pace as they are consumed. Labour itself should be thought of in the same terms with the perspective, not only of compensating for its consumption, but also of developing its capabilities. Many specialists now conceive nature and labour in terms of codevelopment.

The real issue is to work on the sources of social and ecological damage. One source is consumer behaviour; another more significant cause is production and corporate practice in terms of management and investment criteria. Every investment should be specific to each concrete situation from where are issued social and ecological damages. Even if, as it is the case for global warming, the problem is global, carbon emissions are localized in places with specific types of housing, specific industries and technologies, specific people; idem for bad conditions of work and life. To be efficient for reducing ecological and social footprints, investments are to undertake and design in all these places, in taking into account their singularities even if the problem is global. One has to think global, but to act and invest local. This tension between the global and the local underlines the reason why the grand ceremonies at international levels in themselves cannot solve the increasing ecological and social footprints. Research is developing in these areas and should be actively supported by the European Union. The notion of social imprint has to be added to the notion of environmental footprint. Regarding the standard conception of investment by a firm, three big changes are to introduced.

1. Social and ecological footprints for a given firm are not only directly produced by the firm’s mode of production, technology and organization. They also arise from the components, parts, products and energy the firm buys from its suppliers. They also stem from the use of its products (by consumers or downstream firms) and, later, at the end of the life of products, when they are recycled or discarded. The effort made by firms to reduce their footprints is impacted, positively or negatively, by the footprints created by suppliers, customers, users and recyclers.

11 See Salais Robert, 2011, “From social citizenship to social capability in an enlarged economic Europe” in: Lessmann Ortrud, Otto Hans-Uwe, Ziegler Holger (eds.), Closing the Capabilities Gap. Renegotiating Social Justice for the Young, Opladen, Barbara Budrich Verlag, 2011, pp. 27-52.

12 Carbon markets could even crash, leading to a major crisis. See the report “50 shades of green: the rise of natural capital markets and sustainable finance” from the Green Finance Observatory.

13

For instance, we know that even if a smartphone may be not so harmful in itself, , the use of rare earth resources and minerals involve costly and hard to undertake upstream extraction and downstream recycling, with both environmental and social harm. The same is true for electric vehicles.

2. Companies, especially multinational corporations, should include all these upstream and down-stream effects and costs in their design and their profitability evaluation, as well as internal impacts generated directly by the firm itself. These effects should be integrated and remedies sought both in terms of prices and in the material design of investment. The calculation and comparison of return on investment should also integrate these effects. It is also likely that the distribution of the expected outcome should include ex ante forecast provisions to finance the required ecological and social investment, to compensate for damage and even to improve the environment and people’s capabilities (see, for instance, the proposals made by Rambault (2015)).This needs that all relevant voices should participate with adequate rights to the deliberations around the design of investments and their funding: not only shareholders and management, not only the public administrations, but too workers, local populations, the environment itself with adequate and well-informed representatives. One requires economic democracy.

3. Another key change is that cooperation must be required between firms belonging to the same chain, branch, or cluster. In this cooperation, information, knowledge and research must be shared, and all members will gain in efficiency for reducing social and environmental imprints. In this way social and environmental gains will spread horizontally to other chains, branches, clusters, territories.13 European and national policies should create relevant incentives and regulations, and even obligations for firms to enter in such cooperative relationships. Banks, financial funds and all investors should be taught and induced (even subject to regulatory constraints) in order to modify their rules, criteria and practices in these directions. Such cooperation does not impede competition between firms. The main difference with the standard conception is that competition becomes fair, i.e. competition between equals with regards to consideration of environmental and social objectives (close to a common good or the intérêt

general) decided by the Center. In the 1980s Jacques Delors had the same preoccupation when

implementing social Europe, to put firms in an equal situation and on equal footing regarding respect for basic rights. His preoccupation is evident in the case of workplace health and security in European regulations.

For several years the notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been at the core of EU questions regarding the role of companies in society. Unfortunately, international norms (ISO 26000) and the CCE (2001) do not set any constraining rules for corporate behaviour. They propose only vague and limited guidelines concerning the democratic and emancipatory potential of CSR (Jeamet, 2017; Pesqueux, 2011). If one agrees – and this should not be difficult – on a definition of democracy as equal opportunity to participate in the building of our common destiny and future, a certain form of constraint is required to reintegrate politics and democracy everywhere they should be.

Invoking as mantras ethical behaviour for enterprises or social or green capitalism is no longer sufficient. The path in front of us is narrow. We will have to anticipate the impacts of inevitable climate change that define an environment full of uncertainty. Situations will

13An excellent historical example of this horizontal cooperative process of very efficient dissemination and innovation is found in the ways German firms coordinated their standards between firms belonging the same chain or branch of production in the1920s (Brady, 1933).

14

multiply that will require arbitration between priorities – climate risks, socio-economic risks, long-term degradation of ground, water and air quality), all leading to deterioration of an irreplaceable heritage, nature itself (AcclimaTerra, 2018). We must rapidly build up instruments necessary to develop and consolidate a social and economic model that views respect for the environment and well-being as major macroeconomic imperatives.

This is not a utopian vision. Let us keep in mind the projects of the European Commission in the 1970s when it was working on the status of European corporations; and the use of mixed public-private financing for investment in the 1980s. These can serve as models today.

In the 1970s the European Commission proposed a Directive on the European Company Statute that, in retrospect, tried to take on board these objectives at least partially. At the end of process in 1975 (BEC, 1975), and after significant work by the European Parliament (JOCE, 1974), the most advanced propositions were:

- Workers should have equal representation in the Board of Management: one-third of seats for workers’ representatives, one-third for shareholders and one-third for representatives of the ‘general interest’ chosen by common agreement by the other two-thirds The idea was “to enable [workers] to express their point of view when important economic decisions are made upon matters of company management and on the appointment of members of the Board of Management.”

- That “decisions concerning the following matters may be made by the Board of Management only with the agreement of the European Works Council” (article 123).14 These matters were (and we quote):

a) Rules relating to recruitment, promotion, and dismissal of employees; b) Implementation of vocational training;

c) Fixing of terms of remuneration and introduction of new methods of computing remuneration;

d) Measures relating to industrial safety, health and hygiene; e) Introduction and management of social facilities;

f) Daily time of commencement and termination of work; g) Preparation of the holiday schedule.

All of these matters could be addressed through a capability-human rights approach. Freedom in work and workers’ evaluation, in particular, could be treated by relying on items a, b, c, and d. It is not difficult to imagine worker representatives on the Board of Management involved in a strategy of alliances with at least some of the representatives of the general interest and, who knows, perhaps with one or two shareholder representatives, alliances that would be favourable to our objectives.

These projects of the European Commission were not accepted and later disappeared from the European social agenda in the course of financial liberalization. But they remain present as references and resources in the still brief history of the construction of Europe. Furthermore, research continues to explore the field, for instance see work by Favereau and Baudouin (2015), Ferreras (2017) and Robé (2001) on the firm as political entity. These projects should be

15

updated and adapted to the new urgent need to combine environmental and social objectives. It would be necessary, for instance, to include representatives of nature and environmental protection groups and local municipalities, cities and regions among civil society members on corporate boards (at least in the Board of Management). Such partnerships should be instituted at several levels – company, group, country – of firms all the more in case of multinational corporations. It is worth remembering that at the beginning of the 1980s Henk Vredeling, at that time European Commissioner for Social Affairs, proposed a Directive on information, consultation and participation of workers in enterprises belonging to complex structures, such as multinational groups. Among other ideas, the project suggested that workers’ representatives belonging to subsidiaries have direct access to the information available at corporate headquarters regardless of location.15 The least one could do today would be to give access to all relevant information available at all these levels, especially in case of investments choices, to all .One can also imagine that these partners, individually or collectively, would be encouraged to make alternatives choices, or to suggest corrections and improvements; with the condition that such alternatives, corrections or improvements would have to be discussed and, if judged relevant, to be implemented.

2.3 Investment in the building of social infrastructure

Investing in the social domain must no be reduced to a purely productivist logic, nor exclusively focus on the financial returns of social policies. In a capability-human rights approach the goal of investment is to protect people against labour markets contingencies, and not merely only to create a perfectly and immediately mobile and flexible market – the “ideal” market. We will see below that the European conception has a hard time escaping from this so-called ideal.16 On the contrary, people should have the capability to master their lives and the real freedom to choose their employment insofar as possible (Morel and Palme 2016, Report Re-InVEST WP4.1).

The Report of the High-Level Task Force chaired by Romano Prodi and Christian Sautter on Investing in Social Infrastructure in Europe offers proposals, some of which go in this direction, others not. But the right questions are formulated that lead to interesting lines of thinking.

Among other things, this report proposes that the greatest attention should be given to: 1. Shifting from an underinvestment scenario towards a smart capacitating investment

framework with ongoing monitoring of progress at national level;

2. Promoting social infrastructure finance, focusing on the regions with the greatest needs; 3. Increasing and boosting the pipeline of viable projects for social infrastructure;

4. Setting up in the medium-term a public-private fund dedicated to social investment in the EU;

15 See Didry C. and A. Mias, 2005, pp. 75-76. The project was cancelled in 1986 by the new Delors Presidency.

16 Here is an anecdote that expresses this vision that job seekers must accept any task, whatever it is. Once upon a time (17 September 2018), a young man was looking for work as a gardener. By good fortune on this day the gardens of the presidential Elysée Palace were open to the public. The young job seeker met the French President and explained his problem: “I have sent my resumé and motivation letter to many towns and cities. No one has answered me.” The President’s reaction was (our translation): “If you are ready and motivated, there is work in the hotel business, bars, restaurants… or in building construction! Everywhere I go, they all tell me that they are looking for people! All of them! ... You must go. Right now, I could simply cross the street and find a job for you.” (Le Figaro du 18 09 2018, « macron-a-un-jeune-chomeur-je-traverse-la-rue-je-vous-trouve-du-travail »).

16

5. More extensive data collection, on infrastructure risk in general and social infrastructure in particular, should be put in place to help regulators in their effort to combine proper risk evaluation and financial stability;

6. Establishing a stable and more investment-friendly environment; 7. Boosting evidence-based standards for impact investing;

8. Strengthening the role of national and regional promotional banks and institutions (NPBIs) in Europe in their cooperation with public authorities and European bodies. Proposals 3, 5, 6, 7 aim to improve access of the private sector to social bonds and to set standards for impact investing. Expectations are thus turned towards public-private partnership and a “responsible” finance sector. The problem for us is that, instead of the standardization of investments offered by Proposals 5 and 7, it would be more efficient to provide European authorities (and national governments) with financial tools for co-construction of investment in the social sector, alongside bottom-up logic. The gain would be to stimulate a process of collective deliberation for each social investment and thereby better evaluate specific features and be more efficient, socially and economically, by preserving the diversity of the frames for evaluation. The basic issues are to preserve diversity in the design of investments and their end purposes, instead of focusing on financial returns; and to ensure the participation of stakeholders, the population and even the environment itself, through appropriate representatives) and give them genuine empowerment, real tools and adequate resources. As Alix and Baudet (2013) have written, one must “consider that the ground knowledge remains an unavoidable element, complementary to any responsible social policy” (p. 19). The same questions and issues hold for the idea of “social impact bonds” (SIB).

The Prodi/Sautter Report proposes the creation of a Social Investment Fund. This fund should be provided with the capacity – legal, technical and financial – to issue bonds allowing firms and investors to finance social investment. The targeted objective is to achieve a coherent mix between private and public funding, subsidies and financial instruments.

One may regret that the mandate of the Task Force has not been enlarged to include joint consideration of social and environmentally friendly investments, or at least to explore ways in which the standard tools of social and employment policies could be coordinated and renewed. One should overcome the classical bureaucratic division that artificially separates domains which in reality are intimately interwoven. This division is a waste of time, of effort and money, and ultimately is inefficient in politics.

There has been much rich reflection and innovation around financial instruments – expanding an already broad range of contracts to be used. Inversely the technical and economical expertise of investment has been somewhat neglected, specifically the place and role of expertise in the chain from investment design to the structuring of its funding, especially in public/private financing procedures. Too much confidence is given to purely market mechanisms and to their capacity for selecting “good” investments. One needs to go back to earlier funding mechanisms that attributed a basic role to technical and economic expertise in allowing or refusing public financing in the case of mixed procedures. This is all the more necessary because the massive investments needed for joint social and environmental challenges are of a new type, and we have little collective experience and learning in this area. Another specific feature of investing in social infrastructure is that, depending on the country, this investment may fall to municipalities, cities or regions and their elected governments. Territorial governments are closely watched by the local population who are eager to have at their disposal modern infrastructures that deliver real and efficient services (health care,

17

education, employment services and so on). It is essential to give prefer a bottom-up approach, while not neglecting the gains obtained by collective experience. Following OECD (2014), partnership with and participation of the population and local authorities must be facilitated, and proximity between citizens and institutions valued (Drancourt 2015).

Many other proposals of investment financial institutions are on the table at the European and national levels. What is lacking is a “Discourse on Method” that connects financial expertise and technical expertise in order to give priority to the concrete and specific needs and aspirations of the people that live near the proposed social and environmental projects. The starting point for realizing the expertise of projects should be to hear their voices and their needs, directly or through representatives. One must build this Discourse on Method from the bottom up, instead of applying a standard top-down model regardless of location, population, type of economic, social and development to favour. The question is to devise the right approach, a process that addresses the specificities of the circumstances, and not oblige people and stakeholders to choose among standard ready-made solutions or generic instruments.

Here too, going back to past experiments can be fecund, even if they have been forgotten by politicians and policy makers who too often reinvent the wheel instead of looking back to work done by their predecessors. In France, from 1983 to 1986, an investment fund – the Fonds Industriel de Modernisation (FIM) – was created by the government. To be efficient and invest in true modernization of firms (public or private), this fund proposed a strategy for analysing the investment projects –material and immaterial – that applied for funding , a strategy specifically adapted to the diversity of productive organizations, of technologies, of products and of markets in which the enterprises were active.17 The question was not only to focus on standard quantitative indicators defining best practices for management and investment, but to develop a more in-depth qualitative analysis by asking firms to answer a questionnaire on all these matters. The FIM relied upon a vast network of industrial experts, well implanted in regions and branches, either public agencies (for instance the ANVAR – National Agency for the Research Valorization – now a subsidiary of the BPI – the Public Bank for Innovation), private consulting firms or independent workers. Parallel to the technical analysis a financial analysis of the firm’s accounts was conducted and a financial plan established for the selected firms. The funding was innovative, a mix of public and private funding based on equity loans provided by the state. The resources of these loans came from household savings, that were – and still are – managed by a dedicated public bank, la Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations.18 Equity loans, in the French case, are repayable loans, but count as equity for the firm. As such they increase the solvability ratio and improve the company’s capacity to receive private loans from banks and investment funds. Public equity loans serve to guarantee that private investors are the first to be reimbursed in case of unforeseen hazards.

The financial expertise analysed profit expectations, economic and financial issues in relation with the projected investment (working capital needs, history and distribution of equity shares, sustainability of future debt load, etc.). With the help of a summary report and a data form, the steering committee was able to choose projects to be funded and ensure follow-up.

17 Details in Salais R. (1988) « Les stratégies de modernisation de 1983 à 1986 : le marché, l’organisation, le financement », Economie et statistique, 213, pp. 51-73 and in Storper M. and R. Salais (1997), Worlds of Production. The Action Frameworks of the Economy, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, chapter 4, p. 77-93.

18

By including social and environmental issues in such a questionnaire, one can obtain the right questionnaire for today, and even more importantly a strong incentive for firms in examining these issues, internally and externally, and proposing solid solutions, to qualify for funding.

2.4 Reforming social policies and schemes and developing new ones in terms of social investment

The notion of social investment has all the characteristics of a good idea. Investment looks to development of the economy and society, its efficiency, modernisation and prosperity. Investment in the social sector could be seen as starting from the consideration that human beings are not merely resources to be exploited or simply factors of production. They are living beings whose care, competences, and aspirations to well-being (and adding, according to Sen19), freedom, autonomy, participation and solidarity are not only key values, but key objectives to achieve in our societies in their several dimensions – ethical, political, social, environmental and economic. This means that social investment is not exactly the same as investing in social matters. Our attention should be drawn to a basic ambiguity in the European notion of social investment.

2.4.1 Is social investment basically an investment like any other, the only difference being that its content is social and not economic or financial?

If social investment is an investment like others, one need not focus on the diversity of choice criteria or heterogeneity of situations, people, and social schemes and domains, but only on profitability, more or less revisited in its definition and level. The major issue is how to attract investors, private or public, to a new field, how to create a market able to respond to investors’ needs (security, liquidity, profit expectations, size and depth of the market). Meeting investors’ needs means standardization of procedures, of assets, of measurement of outcomes, of beneficiaries’ profiles. If not, investors would not be able to make secure comparisons between investment opportunities, in the social domain and in other sectors; as a consequence, the market would not work. There would be little or no social investment, and some investors would not make the anticipated profit. As we will see, standardization is hard to undertake efficiently. The same problem has arisen when the Commission has studied financing of environmentally friendly investments through financial markets (in the case of sustainable energy).

19

The above slide is taken from the presentation “Finance for sustainable energy” by Adrien Bullier, Project adviser at the European Executive Agency for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (EASME).20 It points to the gap between investment criteria for project developers and those for the financial sector: how “to match squares and circles?” For developers, the relevant criteria are about efficiency gains in terms of economies of energy: technical design tailored to physical constraints, state-of-art technology and energy pay-back times. The latter criteria emphasise that the shorter the energy payback time the more efficient and the less costly will be the investment be for consumers and for society as a whole. These criteria are to be compared with those of the financial sector. What financial investors love above all is maximising the cash flow, the highest return on investment (at least 15% or more a year) to be able to quickly disengage, and predictable risks. They are not interested in design factors (technical, material and immaterial) which they see as a black box. It follows that they need standardization for risks to become predictable (i.e. can be submitted to probability calculation). Thus investors can compare different investments and take insurance against these risks. They fear uncertainty that remains inevitably associated with the many contingencies surrounding the preparation, implementation and functioning of these new types of investments.

However, at the difference of the NPM-based social experts, European environmental experts have seen the contradiction between the squares and the circles: between the technical criteria required for investments in economizing energy, and the financial criteria. The seconds ones impose to find standardized criteria; the first ones have to be adapted to each situation. They oblige to take into account tangible outcomes in economies of energy that should effective fot the concerned people. In the case of the environmental issues dealt with by Adrien Bullier, solutions to bridge the gap are sought by creating new financial tools or renovating old ones, to obtain an adequate mix of public and private funding. Public funding (national and European) is solicited primarily to insure the predictability, and even the security of financial returns for

20 Horizon 2020 Energy Efficiency Information Day, 12 December 2014.

Figure 1 : Finance and sustainable energy. Trying to match squares and circles

20

private investors. One possibility is that the public sector should act as the financer of last resort. In the event of problems leading to financial losses, private creditors are reimbursed first and the state is positioned at end of the process, in short to take losses. This can take the form of, for instance, funding risk-sharing schemes, dedicated credit lines or equity provisions (in particular, to increase the lever effect of European funding). To bridge the gap, the European Commission also proposes to organise dialogue between all relevant stakeholders, to develop roadmaps, to propose improvements in the legal frameworks and to develop template documents and contracts leading to a better understanding of the market.

All in all, in environmental issues the European Commission and investors privilege the financial return and are led to neglect developers’ knowledge and expertise, not to mention the expertise of citizens, even if their relevant mobilization conditions the economic efficiency of each investment. The reason for this is that the financial tools and correlated standardization required by the Commission and investors cannot be grounded in the technological and market expertise of the developers. For this expertise and evaluation will follow the particular features of the local situation and environmental problems, very diverse from one situation to another, and as such cannot be standardized. Our proposal (see below) is to impose, before delivering public loans or subsidies, that technical expertises agree the investment proposed. Such agreements should be an obligatory intermediary step in the funding process for each investment. Such expertises should be made by independent experts, not linked to the investors; these experts should be committed to follow the implementation of investments and evaluate their final outcomes.

The same type of gap between environnemental and financial criteria can be found in the case of social investments. In the social domain, the milieu of financial investors, in relation with the European Commission efforts, have taken a road similar to the one described for environmental issues. But they seem to believe that there is a path that leads from the micro and the individual to the macro and the collective, from the particular to the general. Such belief serves to eliminate the gap in making the micro, the individual and the particular a pure application and duplication of the macro model, as identical clones summed into a global number. This solution is well-known as the notion of “representative individual” in macroeconomics. Here we are not outside of the field of macroeconomics; on the contrary, we cut to its core: the problem of aggregating multiple diverse singular occurrences in one aggregate, one number. The miracle solution is the New Public Management (NPM) that the European Commission has largely contributed to disseminate within the EU, first in macroeconomic guidance and in employment and social domains and now absolutely everywhere. National administrations have followed the EC and implanted NPM methodologies. The problem is that it eliminates any consideration of the value of outcomes for the applicants, for their diversity, from the point of view of their problems and expectations. As the French President Macron answered to this young unemployed aspiring to become gardener: “Right now, I cross the street and I find a job for you”21

2.4.2 Or does social investment mean investing in the social? The social, by essence, concerns society as a whole, people and citizens insofar as they are the collective and individual living targets.

21

In this conception, the major issue is that society as a whole, people and citizens – collectively and individually – must imperatively have their voice heard in investment choices. So a major issue arises, that of democracy, which calls into question modes of governance and of participation. In this conception one faces the same wide diversity and even heterogeneity of situations, of domains, of personal aspirations and of possible solutions as before. However, thanks to the capability-human rights approach (CHRA), another path can be elaborated to solve the problem of heterogeneity while taking in true account the diversity of people’s aspirations and seeking adequate solutions (see, below, Part III). At what levels or steps of the investment process should this approach intervene? Through what participative procedures? What should be the feedback between expression of voices, capability development and investment implementation? How far could one consolidate its status as a democratic issue? How can standard NPM-based governance be renovated? These are some of the many questions to which appropriate answers must be found.

3. Challenging social impact-based governance:

implementing the capability-human rights

approach (CHRA) in social investment

To illustrate and make understandable what follows, we will base our developments on two figures. They go further and complete the methodology on which the WP6 has funded its empirical works and outcomes in that: firstly, they compare line by line, so to speak, social impact-based governance with a CHRA-based approach, and secondly, they introduce what is, in our view, the core issue for social policies, services and schemes and is lacking in the WP6: the type of evaluation of outcomes and the feedback to be created between outcomes and the design and procedures of social policies, services and schemes.

Figure 1 focuses on the type of evaluation and its place and role in social policies. Figure 2 illustrates the process of implementing them. It should be noted that these figures can be read either as ways to build the relationship between social policies and evaluation, or as a methodology to analyse existing policies and to find possible compromises or mixes between the two approaches, i.e. social impact and capability-human rights approaches.

22

Source : Authors’ elaboration

Figure 2 opposes two conceptions of social policies,22 with regards to the relationship between implementation and evaluation, and to their dynamics and adjustment to situations. The lower half of the diagram refers to the social impact approach in which social policies are guided by the maximisation of performance targets. The upper half represents the capability-human rights approach in which policies are guided by the achievement of valuable outcomes for the people concerned. The social impact approach is the one chosen by the European Commission and investors in their conception of social investment; it focuses on maximising the “social impact”, which is precisely the performance with regards to quantitative indicators. The dynamic feedback shown by the arrows in the diagram between policy and performance, results in modifications that are intended to improve performance. This feedback inevitably pushes managers to seek the best statistical profile of the scheme (public or private), i.e. the one that ensures better quantitative performance. The main attraction for private investors is that quantitative performance can be easily expressed in terms of financial return calculations and expectations, yielding incentives that make sense to them.

The capability-human rights approach (CHRA) to social investment would be fundamentally different in all respects. Figure 1 above presents a triangular combination between “means” and “valuable outcomes” mediated by the “capabilities of the person in her/his situation”. It also creates a dynamic feedback between means and outcomes, mediated by the capabilities.

22 In the following we use indifferently the terms of policy, scheme or service as covering the whole field of social tools.

Figure 2 : Two conceptions of the relationship between social policy and evaluation – Improving the power of conversion of means into achievement of valuable

23

Our view is that social investment in Europe (in the sense of investing in the social dimension) should be conceived along the lines of this triangular conception and dynamics. We will begin by deciphering the social impact approach (SIA), its origins, current developments and difficulties (paragraph 3.1), and then compare it with the capability-human rights approach (CHRA).

Paragraph 3.1 analyses the social impact governance as put in place by the European Commission. To invest in the social domain, paragraph 3.2 opposes to to the social impact governance the capability – human rights approach. Paragraph 3.3 explores what implementing a CHRA could be.

3.1 From “evidence” to social impact measurement: the case of social impact bonds (SIB)

In its Communication COM (2013/083) the European Commission blurs the distinction between the third sector and the private sector. It develops what it calls “Targeted EU Initiatives” as if there were no need to consider the third and private sectors as having different goals, principles of action and social philosophy. For instance, the Commission writes: “Innovative financing of social investment from private and third sector resources is crucial to complement public sector efforts.”23 However NGOs, not-for-profit associations, charitable foundations and other social organisations of the same type– have long intervened in the social domain, alone or in cooperation with the public sector. Unlike private capital, in principle at least, NGOs that create infrastructure and provide social services are not searching for financial profit, but seek to contribute to the common good of the community. These EU “initiatives” are not ordinary or banal undertakings, for they range from “supporting social enterprises’ access to finance”, to “exploring the use of new financial instruments” and, not the least, to Social Impact Bonds (SIB) as “avenues to be explored”. The SIB, in particular, are seen as the most advanced type of “social investment”. For private investors the purpose of these bonds is, under certain conditions, to procure a profit to be paid by the public sector. As the Commission states: “With a social impact bond, typically a private investor funds a social service provider to implement a social programme in return for a promise (‘bond’) from the public sector to reimburse the initial investment and pay a rate of return if the programme achieves predefined social outcomes”.24

3.1.1 Enlarging the European definition of social enterprises

For more in-depth understanding, we have to go to another sector of the European Commission, not the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, but the Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Private capital is governed by internal market regulations and controls, including for social activities and social investments as defined by the Communication.25

23 COM (/2013 )83 final, p. 19.

24 COM (2013) 83 final, footnote 17, p. 6.

25 Our thanks to Nicole Alix who was the first to draw our attention to social entrepreneurship as viewed by the European Commission. See Alix N. and A. Baudet, 2013.

24

We know that, thanks to the economic crisis and the abdication of most national governments, the Commission and other European authorities have enlarged their domains of competence and of intervention to include domains for which they have no juridical competence. Public social expenditure has been included in the calculation of States’ overall deficit, bringing social expenditure under the surveillance of the ECB and accentuating its status as an adjustment variable. The European Court of Justice frames its rulings by giving some priority to economic freedoms over social rights. The Communication on social investment recalls that “although social policies are primarily the competence of Member States, the EU supports and complements the activities of the Member States”, which, clearly stated, implies “stronger economic governance and enhanced fiscal surveillance in Member States…and must be accompanied by improved policy surveillance in the social areas which over time contributes to crisis management, shock absorption and an adequate level of social investment across Europe”.26 This is all the more true as the Commission intends to use the European Funds created under the label of social investment to press Member States to employ specific methods of governance.

In the social investment domain, this innovation, built from 2011 to 2013, comes from the DG for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs27. It enlarges the European legal definition of social entrepreneurship. Until now, the standard definition of social enterprise referred to an operator on the social field whose objective was to have a social impact, not to make a profit for their owners or stakeholders. If a positive net income remained after costs, it was expected to be used to better achieve the social objectives, qualitatively and quantitatively. Such operators are generally cooperatives, mutual societies, not-for-profit groups, charitable foundations, and the like.

But the European Commission has subtly modified and extended the definition of social entrepreneurship, so that it now covers new private-sector actors, in particular private investment funds. The Commission considers that “one should use the formidable leverage that the European industry of assets management offers (7000 billion Euros in 2009) to favour the development of enterprises that, beyond the legitimate search for financial profit, also pursue objectives of general interest, of social, ethical and environmental development”.28 So the EU has adopted a series of regulations aiming at creating a framework favourable to social enterprises. The Regulation n°346/2013 on European Social Entrepreneurship Funds (version 14/7/2016)29 is part of the Social Business Initiative established by the Commission in its Communication of 25 October 2011 entitled Social Business Initiative – Creating a favourable climate for social enterprises.

In its preliminary remarks the Regulation states that, “Increasingly as investors also pursue social goals and are not only seeking financial returns, a social investment market has been emerging in the Union, comprising, in part, investment funds targeting social undertakings.30 Such investment funds provide funding to social undertakings that act as drivers of social change by offering innovative solutions to social problems, for example by helping to tackle

26 COM (2013) 83 final, p. 21.

27 See Communication COM/2011/682 25 October 2011, Social Business Initiative. Creating a favourable climate for social enterprises, key stakeholders in the social economy and innovation.

28 Quoted in Nicole Alix and Alain Baudet, 2013. 29 Called REG No 346/2013 below.

25

the social consequences of the financial crisis, and by making a valuable contribution to meeting the objectives of the Europe 2020 Strategy”.31

3.1.2 Achieving measurable, positive social impacts as primary objective to justify profit

The Regulation defines social enterprises as enterprises having among their objectives “to produce positive social impacts”. It is worthwhile examining these conditions in detail. Assets can enter a qualifying social portfolio (i.e. allowing investment funds to participate to the social investment market), when the undertaking satisfies the following main conditions:

- “having the achievement of measurable, positive social impacts as their primary objective in accordance with its articles of association, statutes or any other rules or instruments of incorporation establishing the business,

- providing services or goods to vulnerable or marginalised, disadvantaged or excluded persons,

- employing a method of production of goods or services that embodies its social objective, or providing financial support exclusively to social undertakings,

- using its profits primarily to achieve its primary social objective in accordance with its articles of association, statutes or any other rules or instruments of incorporation establishing the business and with the predefined procedures and rules therein, which determine the circumstances in which profits are distributed to shareholders and owners to ensure that any such distribution of profits does not undermine its primary objective”.32

Banks and insurances are authorized to have social assets that fulfil these conditions in their overall portfolio.

The Commission insists on the fact that positive social impacts should be for these investors “their primary objective”. One cannot be against measurable impacts of social investments, all the more if they appear positive, whether they come from the public sector, the third sector or the private sector. The decisive question regards the methodology and procedures for measuring social impacts. In Paragraph 3.2, we sketch out the measurement methodology of the capability-human rights approach, which, in itself, is not restricted to the public sector, the third sector or the private sector. The pathway preferred by the Commission – developing a social investment market and using performance indicators to evaluate social impacts – appears to be a cul-de sac (a dead-end if one prefers), with regards to its ambition. For any market needs to standardise evaluation procedures. To choose where to invest, investors need to compare the available opportunities. Comparability, to be secure, requires the use of strictly identical methods of measurement, hence standardisation. Given the huge heterogeneity among social domains, it is quite impossible to achieve standardisation in a way that would be satisfactory for private investors. As for investment in environmental issues, the minimum would be risk-sharing between the public and the private sectors, which generates other problems.

Public administration is now accustomed to these notions and has been progressively converted management via market solutions. Depending on the country, more and more public

31 REG No 346/2013, p. 1 32 Ibid., p. 10

26

social services are subcontracted to the private sector, and privatization continues and public-private partnerships flourish. However such arrangements require contracting, negotiation, and recourse to expertise or consulting firms that help management by quantitative performance to penetrate the public sector33. They induce non-negligible indirect costs (the famous transaction costs), and a changing conception of social welfare. Instead of durable procedures, schemes and rules, it favours the development of a project culture, hence of short term and flexible programmes, cobbled together to the detriment of long-term investments.

3.1.3 The politics of evidence as applied to social impact measurement 34

Another aspect of the proposed reforms is to generalise social impact measurement. Not only does such measurement intervene in evaluating the performance of service providers and builders of social infrastructures, and favour the creation of a market, they must also provide the “evidence” required to justify the recourse to private financing. This recourse must exhibit efficient performance in terms of costs and outcomes. It is at the core of the most advanced instrument, Social Impact Bonds (SIB), in which the state has to pay back the initial investment with an additional rate of return for the capital invested in schemes that achieve their targets. Quantification activities are thus tasked with producing evidence that will serve as justification for profits.

One of the main issues to be disentangled is apprehending the biases that the political context surrounding social investments is producing in quantification practices and in evaluation. In this context rational bargaining is developing between the State, investors and service providers (or infrastructure builders). As the example of the Open Method of Coordination (OMC) demonstrates, all the parties have incentives to orient quantification procedures and rules in their favour. For instance, they have incentives to select the best indicators of performance, those that conform to the contractual targets. This cannot but create tensions between the divergent interests of the public administration and the investor. Furthermore, the provider may be tempted to directly maximise the indicators instead of truly improving the social situations of the beneficiaries.

We will look first at this notion of “evidence” and then try to disentangle the “social impact” methodology chosen by the EC. It is not easy for researchers to obtain relevant data and information, as these contracts are increasingly covered by laws protecting business secrecy.

3.1.4 What does “evidence” mean?

The notion of “evidence” is at the core of the political approach to social investment-based reforms of social policies in Europe. “Evidence” belongs to the English tradition of scientific thought since the 17th century, as found in the seminal works of Francis Bacon.35 For Bacon knowledge is not necessarily “fact”. In a nutshell, data are considered as evidence by Bacon and his successors, when they meet two conditions. They should be detached both from

33 See Suleiman E., 2003, Desrosières A., 2008, Salais R., 2010a, 2010b

34 The discussion we pursue here is developed in Mennicken A. and R. Salais, eds., 2019, The New Politics of Numbers. Quantification, Administrative Capacity and Democracy, London, Palgrave, forthcoming.