FACULTE DE MEDECINE D’AMIENS UNIVERSITE DE PICARDIE JULES VERNE

Année 2017 Thèse n° : 2017 - 78

THESE POUR LE DIPLOME D’ETAT DE DOCTEUR EN MEDECINE

SPECIALITE HEMATOLOGIE OPTION ONCO-HEMATOLOGIE

Par Déborah ASSOUAN

Soutenue publiquement le jeudi 7 septembre 2017 à 14h00

RUXOLITINIB : UN TRAITEMENT PROMETTEUR DE LA

MALADIE DU GREFFON CONTRE L’HÔTE

CORTICORESISTANTE

Membres du jury :

Président : Monsieur le Professeur Jean-Pierre MAROLLEAU Assesseur(s) :

Monsieur le Professeur Loïc GARCON

Monsieur le Professeur Julien MAIZEL

Monsieur le Docteur Mathurin FUMERY

Directeur de thèse : Madame le Docteur Bérengère GRUSON

Remerciements

Au président du jury

Monsieur le Professeur Jean-Pierre MAROLLEAU

Professeur des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier (Hématologie, Transfusion) Chef du service d’Hématologie clinique et de Thérapie cellulaire

Chef du Pôle « Oncopôle »

Je vous remercie de m’avoir transmis votre passion de l’hématologie avec rigueur, humour et bienveillance.

Aux membres du jury

Monsieur le Professeur Loïc GARCON

Professeur des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier (Hématologie, Transfusion) Chef de service du laboratoire d’Hématologie

Je vous remercie de m’avoir enseigné avec beaucoup de pédagogie les bases de la cytologie lors de mon semestre au laboratoire. Veuillez trouver l’expression de mon profond respect et de mes remerciements pour l’honneur que vous me faites d’accepter de juger ce travail.

Monsieur le Professeur Julien MAIZEL

Professeur des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier (Réanimation, médecine d’urgence)

Je vous remercie de la qualité de votre enseignement dans le service de réanimation, en particulier durant les staffs médicaux. Veuillez trouver l’expression de ma gratitude pour l’intérêt que vous portez à ce travail et l’honneur que vous me faites de participer à mon jury de thèse.

Monsieur le Docteur Mathurin FUMERY

Maître de Conférences des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier (Gastro-entérologie)

Veuillez trouver l’expression de mes plus sincères remerciements pour votre enthousiasme et l’honneur que vous me faites d’accepter d’évaluer cette thèse.

A mon directeur de thèse

Madame le Docteur Bérengère GRUSON Praticien Hospitalier (Hématologie, Transfusion)

Travailler avec toi est un réel plaisir, tant tu transmets avec aisance et pédagogie tes connaissances. Tu es un modèle pour moi et nombre de mes collègues. Je te remercie de m’avoir fait l’honneur de diriger ce travail.

Je tiens également à remercier les équipes médicales

Toute l’équipe médicale du service d’hématologie : Delphine LEBON, Amandine CHARBONNIER, Magalie JORIS, Marie BEAUMONT, Lavinia MERLUSCA, Pierre MOREL, Caroline DELETTE, sans oublier Bruno ROYER et Anne PARCELIER

Merci à tous pour tout ce que vous m’avez appris

A tous les médecins avec lesquels j’ai eu la chance de travailler durant l’internat et en particulier :

Professeur Bruno CHAUFFERT

Je vous remercie pour vos enseignements et vos conseils prodigués avec rigueur, dynamisme et humour et pour continuer de m’encourager à allier oncologie et hématologie. Je garde un souvenir savoureux des visites hebdomadaires dans votre service.

Docteur Elisabeth CAROLA

Je vous remercie de m’encourager en oncogériatrie avec votre enthousiasme légendaire.

Docteur Pascal CHAIBI

Ce fut un plaisir de vous voir allier brillamment l’exercice de l’hématologie et la subtilité que nécessite la prise en charge dans la population âgée. Mon expérience au sein de votre équipe me fut particulièrement enrichissante. A bientôt en Picardie.

Docteur Reda GARIDI

Je n’oublie pas mon premier semestre d’hématologie au B10. Merci de si bien accompagner les internes avec beaucoup de pédagogie, d’amitié et de bienveillance. A toutes les équipes paramédicales

Trop nombreux pour être tous cités, c’est un plaisir de travailler avec des équipes toujours motivées, dynamiques et prêtes à donner beaucoup pour la prise en charge multidimensionnelle des malades en toute circonstance.

A mes amis

A Sabrina, Elise, JB, Loïc, mes déjà vieux amis d’enfance. A Juliette F. Merci de ton amitié et d’être toujours si drôle.

A mes lillois chéris. Zazou, Cécé, Adrien, Juliette W, Juliette B, Flore. Quelle intelligence nous avons eu de nous éparpiller, et d’être obligés de se retrouver autour d’un punch planteur au Gosier, d’un barbecue aux Salines, d’un brunch au Rowing à Marseille, sur le dancefloor à Farber et autres rooftops parisiens et semaines au ski. A nos toujours savoureuses retrouvailles.

A mes amis de Picardie et co-internes. A Angie, Mathieu et Diane, déjà de nombreuses aventures depuis notre première garde, seules à rechercher les normes de la troponine dans la pampa abbevilloise à 3h du matin puis les premières battles de danse d’anthologie. A Sophie, Geoffrey, Circé et Paul, je n’oublierai jamais le mango lolo! Merci pour votre belle

philosophie. A ma Nathou, merci pour ta politesse (tu n’oublies jamais de dire bonjour !) et à nos moments de folie. A Elodie et Adelin, merci pour votre bonne humeur constante et tous les bons plans, jeux et lieux découverts grâce à vous. A mes pros du coloriage Jessica, Julien. A Vivien et Soraya. A Léa et Weswes, merci pour nos moments de danse chic et choc. A Anne-Elise, Marie-Jo et Charlotte, mes sacrées co-internes au labo. A la fine fleur de l’hémato picarde Alexis C, Candice, Mathieu, Alexis L, merci pour tous ces bons moments en stage et en dehors, sans oublier Hélène, Laura et Lydia. A Juliette P comme Pont, Sarah, Myriam, Pauline, Romain et Mathieu pour un semestre top. A Diana, à Arnaud

A ma famille

Si la chanson dit qu’on ne choisit pas ses parents, c’est bien vous que j’aurai choisie. Papa, Maman, votre bienveillance, votre soutien, et surtout vos prétextes facétieux pour déboucher le champ m’ont toujours été d’une aide précieuse.

A Mélanie et Emmanuelle, mes complices et sœurs adorées. A Sarah, ma magnifique filleule.

A ma grande famille aux quatre coins du monde, aux anciens et aux adorables petits nouveaux Raphaël et Mathis.

A Antoinette, Jean-François,Marielle, William, Laurie, Manu, Cassandre et Aurèle, ma fantastique nouvelle famille.

A Rody, merci pour ton second degré et ta délicieuse insolence. A mon Yann, pour ta patience et ton amour.

Table des matières

Abréviations... 7

Introduction générale ... 8

Allogreffe de cellules souches hématopoïétiques ... 8

Complications de l’allogreffe ... 9

GVH ... 11

Epidémiologie et manifestations cliniques ... 11

Physiopathologie de la GVH aiguë ... 11

Traitements de la GVH aiguë ... 13

Epidémiologie et manifestations cliniques ... 14

Physiopathologie de la GHV chronique ... 15

Traitements de la GVH chronique ... 16

Ruxolitinib dans la GVH-CR ... 16

Rationnel et objectif de l’étude ... 17

Article - Ruxolitinib as a promising treatment for corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease. ... 19

Introduction ... 19

Patients and methods ... 20

Results ... 20

Discussion ... 23

Abstract ... 24

Discussion générale ... 25

Principaux résultats et analyse de la littérature ... 25

Limites de l’étude ... 26

Perspectives ... 27

Conclusion générale ... 27

Bibliographie ... 28

Article publié ... 32 Classification de la GVH aiguë : critères de Glücksberg ... 36 Classification de la GVH chronique ... 37

Abréviations

CHU : centre hospitalier universitaire

CIBMTR : center for international blood and marrow transplant research CMH : complexe majeur d’histocompatibilité

CMV : cytomégalovirus

CPA : cellule présentatrice de l’antigène CS : cellules souches

CSH : cellules souches hématopoïétiques

CTCAE : common terminology criteria for adverse events Jak2 : Janus-activated kinase 2

GVH : graft versus host disease (Maladie du greffon contre l’hôte) GVHa : maladie aiguë du greffon contre l’hôte

GVHa-CR : maladie aiguë du greffon contre l’hôte corticorésistante GVHc : maladie chronique du greffon contre l’hôte

GVHc-CR : maladie chronique du greffon contre l’hôte corticorésistante GVH-CR : GVH corticorésistante

GVL : graft versus leukemia (réaction du greffon contre la leucémie) GVT : graft versus tumor (réaction du greffon contre la tumeur) HLA : human leukocyte antigen

IC95% : intervalle de confiance à 95% IFNgamma : interferon gamma IL : interleukines

LAL : leucémie aiguë lymphoblastique LAM : leucémie aiguë myéloïde NIH : national institute of health

PAMPs : motifs moléculaires associés aux pathogènes SMD : syndrome myélodysplasique

Introduction générale

Allogreffe de cellules souches hématopoïétiques

L’allogreffe de cellules souches hématopoïétiques (CSH) est le traitement curateur d’hémopathies malignes principalement, mais aussi d’hémopathies bénignes et de pathologies dysimmunitaires. Les leucémies aiguës myéloblastiques (LAM) et lymphoblastiques (LAL) sont les principales indications. Viennent ensuite les syndromes myélodysplasiques (SMD), les aplasies médullaires puis les hémopathies lymphoïdes et les myélomes multiples (figure 1).1

FIGURE'1':'REPARTITION'DES'INDICATIONS'D'ALLOGREFFE'EN'EUROPE'EN'20141'

Abréviations et traduction : AML : leucémie aiguë myéloblastique, ALL : leucémie aiguë

lymphoblastique, CML : leucémie myéloïde chronique, MDS/MPS : syndromes

myéloprolifératifs/myélodysplasiques ; CLL : leucémie lymphoïde chronique, PDC : maladies plasmocytaires, HD : maladie de Hodgkin, NHL : lymphome non hodgkinien, solid tumors : tumeurs solides, BMF : aplasies médullaires, thal/sickle : hémoglobinopathies, PID : déficits immunitaires

primitifs, IDM : désordres métaboliques, AID : maladies autoimmunes, others : autres

Le principe de ce traitement repose sur l’efficacité du conditionnement, le remplacement de la moelle défaillante du patient par un greffon de cellules souches hématopoïétiques d’un donneur sain, et surtout sur l’effet immunologique du greffon contre la tumeur (GVT) encore appelé effet du greffon contre la leucémie (GVL).2 Dans un premier

temps, est réalisé un conditionnement par une chimiothérapie et/ou une radiothérapie qui vise à induire une immunodépression indispensable à la « prise de greffe ». Il a aussi un effet anti-tumoral direct. La deuxième étape consiste en la réinjection du greffon de cellules souches hématopoïétiques d’un donneur sain. Celui-ci est issu d’un don de cellules souches périphériques obtenues par cytaphérèse ou par don de moelle osseuse 3. L’utilisation de sang de cordon placentaire4 est plus rare. Le donneur et le receveur doivent avoir une histocompatibilité HLA suffisante. Une allogreffe est dite géno-identique lorsque le donneur est issu de la fratrie, phéno-identique en cas de donneur non apparenté, identifié sur le fichier international des donneurs volontaires, ou encore haplo-identique lorsque le donneur est un enfant ou un parent à moitié compatible. Il peut exister un certain degré d’incompatibilité HLA, appelé mismatch en cas de greffe phéno-identique (9/10ème ou 8/10ème) ou haplo-identique (5/10ème).5 Malgré les bénéfices apportés par la procédure d’allogreffe, de nombreuses complications sont imputables au traitement, en particulier les complications infectieuses et la maladie du greffon contre l’hôte (GVH).

Complications de l’allogreffe

Les complications de l’allogreffe ont une incidence et une gravité variables selon les facteurs de risques du receveur et les modalités de la greffe. Elles sont responsables d’une morbi-mortalité importante. En effet, la survie à 2 ans après allogreffe, toutes indications et types d’allogreffe confondus, est de 56.4% d’après les données de l’agence de biomédecine. La première cause de décès est la rechute de la maladie initiale pour plus de la moitié des cas, puis la GVH et les infections d’après les données du CIBMTR (Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research) (figure 2).

FIGURE'2':'REPARTITION'DES'CAUSES'DE'DECES'APRES'ALLOGREFFE'(CIBMTR':'2010:2011)'

Complications immunologiques : GVH et rejet du greffon

La réaction du greffon contre l’hôte (aiguë et chronique) est une complication très fréquente après allogreffe atteignant environ la moitié des patients6, malgré un traitement immunosuppresseur préventif systématique. Le rejet du greffon est, quant à lui, très rare avec une incidence inférieure à 1%.7

Complications infectieuses

Les infections bactériennes8 sont quasi-systématiques et les infections fongiques, virales ou parasitaires sont très fréquentes chez les patients allogreffés. Elles surviennent soit pendant la période initiale d’aplasie post-chimiothérapie, soit plus tardivement, induites par les traitements immunosuppresseurs.

Autres complications

Les autres principales complications sont : la maladie veino-occlusive9, de microangiopathie thrombotique10 et les cancers secondaires.11

GVH

Définitions

La GVH a été initialement décrite par Barnes12 en 1962 et définie par Billingham13

comme étant un syndrome dans lequel les cellules immunocompétentes du donneur reconnaissent et attaquent les tissus de l’hôte immunodéprimé. La GVH est secondaire à la reconnaissance, par les lymphocytes T immunocompétents du donneur, des tissus du receveur. Les manifestations cliniques de la GVH sont hétérogènes et peuvent impliquer de multiples organes. Selon le délai d’apparition des symptômes, avant ou après 3 mois post-greffe, on distingue classiquement deux entités : la GVH aiguë et la GVH chronique.14 Plus récemment, la conférence de consensus NIH (National Institute of Health) apporte 2 nouvelles catégories intégrant le type de symptômes et la temporalité. La GVH aiguë persistante, correspond à des symptômes de GVH aiguë après 100 jours. L’overlap syndrom ou syndrome de chevauchement est la coexistence de symptômes de GVH aiguë et chronique.15

GVH aiguë

Epidémiologie et manifestations cliniques

La GVH aiguë touche principalement la peau, le foie et le tube digestif. Elle peut également être responsable de cytopénies par inhibition de l’hématopoïèse. La classification de Glücksberg permet de classer la GVH aiguë en 4 grades de sévérité croissante selon le nombre d’organes atteints et l’intensité des lésions.16 L’incidence de la GVH aiguë, cliniquement significative (de grade II à IV selon la classification de Glücksberg) varie entre 40%17,18 pour un donneur apparenté et 50% pour un donneur non apparenté. Les principaux facteurs de risque de GVH sont : un donneur non apparenté19, un mismatch HLA20, le jeune âge du receveur, la leucémie aiguë comme pathologie initiale, le type de greffon (cellules souches périphériques).6 Le pronostic de la GVH aiguë cortico-résistante (GVHa-CR) est défavorable avec une survie de 36% pour les répondeurs à une deuxième ligne et de 17% pour les non-répondeurs.21

Physiopathologie de la GVH aiguë

La compréhension de la pathogenèse vient essentiellement de modèles animaux. Le développement de la GVH aiguë peut être modélisé en 4 grandes étapes avec des boucles de

rétrocontrôle qui entretiennent le processus. La première étape consiste en l’activation des cellules présentatrices de l’antigène (CPA) par le conditionnement et les lésions tissulaires qu’il engendre. De plus, la translocation de bactéries digestives, les PAMPs (motifs moléculaires associés aux pathogènes) et les chimiokines activent des éléments de l’immunité innée qui vont également participer à la création de lésions tissulaires. Toutes ces lésions vont provoquer une importante libération de cytokines pro-inflammatoires (Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, interleukines IL1, 2 et 6) en réponse à la présentation de l’antigène. L’étape suivante est le recrutement, l’activation et la prolifération de cellules T effectrices et de cellules de l’immunité innée du donneur en réponse au relargage de cytokines. Les cellules T cytotoxiques, les cellules NK, les macrophages et les cytokines pro-inflammatoires vont entraîner des lésions d’organes au niveau du foie, du tube digestif, de la peau. En l’absence de traitement, le processus s’entretient par un rétrocontrôle positif des cytokines entraînant une aggravation des lésions (figure 3).22

FIGURE'3':'PHYSIOPATHOLOGIE'DE'LA'GVH'AIGUË'(D'APRES'BLAZAR'ET'AL)22'

Abréviations et traduction : TLR : Toll-like-receptor, APC : cellules présentatrices de l’antigène, CTL : lymphocyte T cytotoxique

Traitements de la GVH aiguë

La prévention repose sur un traitement prophylactique par des immunosuppresseurs, dont l’objectif est de limiter l’activation des lymphocytes T. Le choix des molécules dépend du conditionnement, du type de greffon, du type de donneur et des facteurs de risque de GVH. Le traitement de référence repose sur la ciclosporine A, associée au méthotrexate23 dans les conditionnements myéloablatifs et au mycophénolate mofétil24 dans les conditionnements non myéloablatifs. Lors de l’apparition d’une GVH aiguë de grade supérieur ou égale à II de Glucksberg (annexe), la première ligne thérapeutique consiste en l’emploi de corticoïdes à forte dose (1 à 2 mg/kg/j). La moitié des malades va être cortico-résistante, c’est à dire avec une aggravation des symptômes au bout de 3 jours ou une stabilité au bout de 5 à 7 jours ou une réponse incomplète à 14 jours de méthylprednisolone à la dose de 2 mg/kg/j.25 En cas de

GVH-CR, il n’existe aucun consensus thérapeutique et le pronostic défavorable puisque les immunosuppresseurs classiquement utilisés ont une faible efficacité.

Les principales classes thérapeutiques utilisées dans le traitement de la GVHa-CR ciblent la CPA, le lymphocyte T et leur interaction (figure 4):26,27

,! Inhibiteurs cytokiniques : infliximab28, etanercept29! ,! Antagonistes des récepteurs aux cytokines 30!

,! Inhibiteur des lymphocytes T : sérum anti-lymphocytaire31 , photophorèse extracorporelle32!

,! Inhibiteurs mTOR33!

,! Inhibiteurs de la prolifération cellulaire : méthotrexate34, micophénolate mofetil35! ,! Inhibiteurs HDAC36!

,! Inhibiteur des récepteurs aux chimiokines37! ,! Traitements immunomodulateurs38,39!

FIGURE'4:'MODE'D'ACTION'DES'PRINCIPALES'STRATEGIES'THERAPEUTIQUES'DANS'LA'GVH'AIGUË26'

Abréviations et traduction : Ab : anticorps, ECP : photophorèse extracorporelle, ITAM : immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif, MMF : mycophenolate mofetil, MSC : cellules souches mésenchymateuses, mTOR : mammalian target of rapamycin complex, NKT : lymphocyte T natural killer.

GVH chronique

Epidémiologie et manifestations cliniques

La GVH chronique est une cause importante de morbidité et de mortalité tardive après allogreffe. Son incidence est de 30 à 70% selon les études.40 Les manifestations cliniques de la GVH chronique sont souvent similaires à celles de maladies auto-immunes et peuvent toucher de nombreux organes (peau, phanères, œil, bouche, organes génitaux, tube digestif, foie, poumon, système musculo-squelettique, moelle osseuse, système immunitaire). La conférence de consensus NIH de 200514, révisée en 201415 (annexe), a permis de caractériser les manifestations cliniques pléomorphes de la GVHc-CR, d’établir un score de sévérité et d’émettre des recommandations de traitement. Bien que la moitié des patients répond à la

première ligne de traitement par des corticoïdes41 plus ou moins associés à un inhibiteur de la calcineurine42, le pronostic de la GVHc-CR est défavorable.

Physiopathologie de la GHV chronique

La physiopathologie de la GVH chronique reste mal connue notamment parce que peu de modèles animaux permettent de reproduire la maladie humaine. En plus de l’allo-réactivité, la GVH chronique serait la conséquence de réactions d’auto-réactivité consécutives à une prolifération homéostatique des lymphocytes T matures du donneur43, à une thymopoïèse anormale et à une diminution de la production de lymphocytes T régulateurs44. De plus, on sait depuis quelques années que les lymphocytes B ont un rôle important dans la physiopathogenèse de la GVHc-CR (figure 5).

Traitements de la GVH chronique

Le traitement initial repose sur la corticothérapie associée à la poursuite de la ciclosporine A. En cas d’échec de cette première ligne, il n’existe pas de consensus pour la prise en charge. Les principales molécules utilisées en cas de GVHc-CR sont le rituximab, l’imatinib et la photothérapie extracorporelle, l’azathioprine, le sirolimus, le mycophenolate mofetil, la pentostatin, l’IL-2, le methotrexate, le bortezomib et le thalidomide. De nombreuses autres cibles thérapeutiques sont à l’étude (figure 6).26

FIGURE'6'MODE'D'ACTION'DES'PRINCIPALES'STRATEGIES'THERAPEUTIQUES'DANS'LA'GVH'CHRONIQUE26'

Abréviations et traduction : BCR: Récepteur cellule B, M : phase M, S : phase S, SYK : spleen tyrosine kinase

Ruxolitinib dans la GVH-CR

Le ciblage de la voie de signalisation intracellulaire JAK/STAT, est une modalité intéressante de traitement de la GVH. En effet, les inhibiteurs de JAK bloquent l’activation des facteurs de transcription STAT. Le ruxolitinib est un inhibiteur de JAK2, déjà disponible

sur le marché pour le traitement de la myélofibrose.45 On sait que la voie JAK/STAT est exprimée dans les cellules T et joue un rôle important dans la régulation du système immunitaire. Dans les cellules T, Jak1 et 2 régulent de nombreuses cytokines pro-inflammatoires, impliquées dans la GVH, comme l’interféron-gamma (INF-gamma), les interleukines IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 et IL-23 (figure 7).

FIGURE'7':'MODE'D'ACTION'DE'L'INHIBITEUR'JAK1/2'(D'APRES'TESHIMA'ET'AL)'46'

L’inhibition du signal de JAK1/2 par le ruxolitinib a réduit la GVH dans un modèle murin, par l’inhibition de l’expansion des cellules T du donneur et de la production de cytokines et par l’augmentation de la proportion de lymphocytes T régulateurs. Suite à ces observations les auteurs de ce travail ont traité par ruxolitinib 6 patients avec une GVH-CR lourdement prétraitée. Le passage du modèle murin à la clinique fut un succès car tous les patients ont eu des réponses rapides.47

Rationnel et objectif de l’étude

La prise en charge actuelle de la GVH-CR ne repose sur aucun consensus et les traitements habituellement utilisés sont souvent inefficaces. Dans ce contexte, la pertinence du rationnel biologique et la disponibilité de la molécule nous ont conduit à expérimenter le

ruxolitinib. Des premiers résultats intéressants, nous ont conduit à mener cette analyse rétrospective.

Article - Ruxolitinib as a promising treatment for

corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease.

Authors: Déborah Assouan1, Delphine Lebon1, Amandine Charbonnier1, Bruno Royer1, Jean-Pierre Marolleau1, Bérengère Gruson1

1 Hématologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire d’Amiens, France

Keywords: GVHD, HSC TRANSPLANTATION, RUXOLITINIB, MALIGNANT HAEMATOLOGY, CORTICOSTEROIDS

Introduction

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the main cause of morbidity and mortality in patients having undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Although there is a consensus on the first-line use of high doses of corticosteroids to treat GVHD, 30% to 40% of patients will display corticosteroid-refractory GVHD (CR-GVHD). This condition is associated with a poor prognosis (i.e. a long-term survival rate of only 5% to 30%).27 Immunosuppressants and immunomodulators (such as anti-IL2 receptor antibodies, anti-thymocyte globulins, mycophenolate mofetil, mTOR inhibitors, low-dose methotrexate, rituximab, alemtuzumab, anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antibodies, pentostatin, mesenchymal stem cells and extracorporeal photopheresis)48 are the main salvage therapy

options for CR-GVHD but lack satisfactory effectiveness. None of these treatments has been established as a standard second-line option. The combination of corticosteroids with other immunosuppressants agents is associated with high toxicity. Furthermore, broad immunosuppression leads to both secondary infectious complications and mitigation of the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect. Hence, there is a strong need for targeted therapies that yield long-lasting responses with as little immunosuppression as possible. Ruxolitinib is an orally administered tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor used in the treatment of myelofibrosis.45 Experiments in an animal model has shown that by inhibiting the JAK-STAT signalling pathway (involved in the development of T-cell alloreactivity), ruxolitinib is effective in GVHD and does not affect GVL activity.49

Patients and methods

We performed a retrospective study of 10 CR-GVHD patients having been treated with ruxolitinib in our institution (the Department of Haematology at Amiens University Hospital, Amiens, France), between May 2014 and July 2015. Acute CR-GVHD was defined by disease progression after 3 days, with stable disease at 7 days and an incomplete response to 2 mg/kg/d methylprednisolone at 14 days.25 We staged the severity of acute GVHD by applying Glucksberg’s system.50 Overlap syndrome was defined as the concomitant occurrence of features of chronic GVHD and acute GVHD, according to the NIH consensus criteria.14

We defined a complete response as the complete resolution of all signs and symptoms of GVHD in all organs. A partial response was defined as an improvement (by at least one Glucksberg stage) in one or more organs and the absence of progression in any other organs.51

Infectious adverse events and hematologic toxicity were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

Results

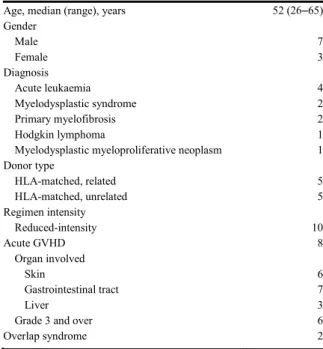

The characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The 10 patients with CR-GVHD (3 women and 7 men) had a median (range) age of 52 (26-65). Five patients had received a graft from a related HLA-matched donor, and 5 patients had received a graft from an unrelated HLA-matched donor. All patients received a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen with fludarabine and busulfan. This was combined with sequential therapy for refractory acute leukemia in two cases and fludarabine-melphalan conditioning in one case. The patients received prophylactic combination treatment with anti-thymocyte globulins, cyclosporine and (in some cases) methotrexate. Eight patients had acute GVHD and two had overlap syndrome (Table 1).

All patients underwent first-line (n=6) or second-line (n=4) treatment with ruxolitinib 10 mg bid. The median treatment duration was 134 days. Ruxolitinib was given alone for 7 patients and was combined with an anti-IL2 receptor antibody in two cases and with an anti-TNF alpha antibody in one case.

TABLEAU 1: CHARACTERISTICS OF 10CR-GVHD PATIENTS TREATED WITH A RUXOLITINIB -BASED REGIMEN Age!(median,!range)! 52!(26,65)! Gender( ( male! 7! female! 3! Diagnosis( ( acute!leukaemia! 4! myelodysplastic!syndrome! 2! primary!myelofibrosis! 2! Hodgkin’s!lymphoma! 1! myelodysplastic!myeloproliferative!neoplasm! 1! Donor(type( ( HLA,matched,!related! 5! HLA,matched,!unrelated! 5! Regimen(intensity( ( reduced,intensity! 10! Acute(GVHD( 8! Organ!involved! ! skin! 6! gastrointestinal!tract! 7! liver! 3! Grade!3!and!over! 6! Overlap(syndrome( 2!

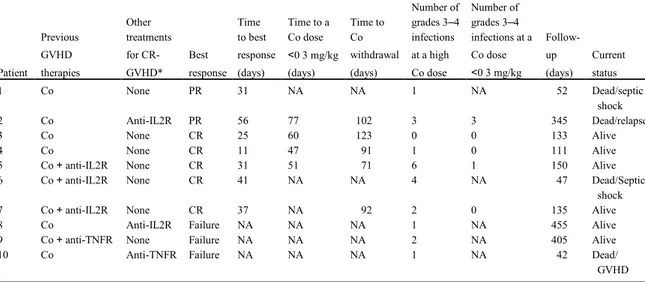

Seven patients (5 of the 8 patients with acute CR-GVHD and both of the patients with overlap syndrome) were seen to be responders after a median (range) time interval of 31 days (11-56). There were five complete responses. For five of the responders, we were able to (i) decrease the corticosteroid dose to below 0.3 mg/kg per day after a median (range) of 55.5 days (47-77), and (ii) withdraw corticosteroids after a median of 92 days (71-102). A reduction in the prednisone dose to below 0.3 mg/kg/day was associated with a decrease in the frequency of severe grade 3 or over infectious events (Table 2).

TABLEAU 2:RESULTS

* other than corticosteroids.

Abbreviations: Co: corticosteroids; anti-IL2R: anti-IL2 receptor antibody; anti-TNFR: anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor antibody; NA: not applicable; CR-GVHD; corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host-disease; PR: partial response; CR: complete response

Patient! Previous!GVHD2!therapies!

! Other!treatments! for!CR2GVHD*! Best!response! Time!to!best! response!(days)! Time!to!Co!dose! <!0.3!mg/kg! (days)! ! Time!to!Co! withdrawal! (days)! Number!of!grade! 324!infections!at! a!high!Co!dose! Number!of!grade! 324!infections! at!a!Co!dose!<0.3! mg/kg! Follow2up!(days)! Current!status!

1! Co! none$ PR! 31! NA! NA! 1! NA! 52! septic!shock!Dead/!

2! Co! anti2IL2R! PR! 56! 77! 102! 3! 3! 345! relapse!Dead/!

3! Co! none! CR! 25! 60! 123! 0! 0! 133! Alive!

4! Co! none! CR! 11! 47! 91! 1! 0! 111! Alive!

5! Co!+!anti2IL2R! none! CR! 31! 51! 71! 6! 1! 150! Alive!

6! Co!+!anti2IL2R! none! CR! 41! NA! NA! 4! NA! 47! Septic!shock!Dead/!

7! Co!+!anti2IL2R! none! CR! 37! NA! 92! 2! 0! 135! Alive!

8! Co! anti2IL2R! Failure! NA! NA! NA! 1! NA! 455! Alive!

9! Co+!anti2TNFR! none! Failure! NA! NA! NA! 2! NA! 405! Alive!

Platelet loss was the most common form of cytopenia. Grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia was observed in 7 of the 10 patients, whereas severe neutropenia and anaemia was reported in 4 cases. With a median follow-up of 134 days, median survival of the cohort study hasn’t been reached.

Discussion

A standardized treatment is not available for acute and chronic CR-GVHD. Ruxolitinib is a promising targeted therapy, with encouraging results in our cohort. 70% of the patients responded to the drug after about a month. A retrospective study assessed the use of ruxolitinib in 95 patients with GVHD.52 The overall response rate was high (81.5% and 85.4%, for acute and chronic CR-GVHD, respectively). These data are consistent with our findings; although none of the patients in our cohort had chronic GVHD.

The infectious risk (enhanced by prolonged exposure to high doses of corticosteroid) remains an important cause of non-relapse-related mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In our cohort, we observed a number of severe infections in patients taking high doses of corticosteroid, including two deaths due to septic shock.

For the seven responders, we were able to decrease the prednisone dose to below 0.3 mg/kg/d in a median of 55.5 days (47-77). After cautious dose reduction, we were able to withdraw corticosteroids after a median of about 3 months. Achieving a low-dose corticosteroid regimen may help to avoid severe infections. Most of the patients had severe thrombocytopenia (a well-known ruxolitinib-related adverse drug reaction) but there were no case of haemorrhage. At baseline, six patients already had an abnormally low platelet count (i.e. below 100000/mm3).

We were unable to assess any loss of GVL activity. We noticed one case of relapsed acute leukemia during combination treatment with ruxolitinib and an anti-IL2 receptor antagonist. A longer follow-up period with more data would be informative. For Zeiser et al, loss of the GVL effect appears in 9.3% of patients with acute CR-GVHD and in 2.4% of patients with chronic CR-GVHD. Ruxolitinib is a valuable drug, with efficacy in CR- GVHD. Prospective clinical trials of JAK-inhibitors might enable a treatment strategy in CR-GVHD to be defined.

Abstract

Corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease (CR-GVHD) is still a major problem in patients having undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Here, we report on the outcomes for 10 CR-GVHD patients treated with ruxolitinib from May 2014 to July 2015. Seven patients responded after a median (range) time interval of 31 days (11-56). There were 5 complete responses. For five of the responders, we were able to decrease the corticosteroid dose to below 0.3 mg/kg per day after a median (range) of 55.5 days (47-77). We observed a reduction in the number of severe infections following corticosteroid dose reduction to below 0.3 mg/kg/d. Ruxolitinib appears to a promising treatment for CR-GVHD.

Author contributions: DA, DL, AC, BR, JPM and BG performed the research. DA and BG

Discussion générale

Principaux résultats et analyse de la littérature

La GVH-CR est une des complications majeures de l’allogreffe de CSH, avec une faible survie de 17% à 34%21 pour la GVHa-CR, une morbidité au premier plan dans la

GVHc-CR53, des options thérapeutiques limitées et mal codifiées. Il est donc particulièrement

intéressant de constater que dans notre étude 7 patients sur 10 sont répondeurs au ruxolitinib avec un délai médian de 31 jours. Nos résultats sont concordants avec ceux de Zeiser52 et al, publiés en juillet 2015 dans Leukemia. Cette analyse rétrospective est la principale, portant sur l’efficacité du ruxolitinib à 10mg et 20mg/j chez 54 patients atteints de GVHa-CR de grade III ou IV et 41 patients atteints de GVHc-CR dans 19 centres. Les patients étaient déjà lourdement prétraités avec une médiane de 3 lignes antérieures de traitement de la GVH-CR. Le taux de réponse globale était de 81,5% dont 46,3% de réponse complète dans le groupe GVHa-CR avec un délai médian de réponse de 1,5 semaines. Dans le groupe GVHc-CR, le taux de réponse globale était de 85,4% dont 74% de réponse partielle avec un délai médian de réponse de trois semaines. La survie globale à six mois était de 79%, IC95 67.3-90.7% (intervalle de confiance à 95%) et de 97,4 % IC95% 92.3-100% respectivement dans les groupes GVHa-CR et GVHc-CR. Moins de 7% des patients répondeurs avaient une rechute de la GVH. Les cytopénies et les réactivations du CMV étaient les principaux effets secondaires décrits sous ruxolitinib. La perte de l’effet GVL, effet secondaire redouté sous immunosuppresseur, semble faible avec un taux de rechute de la maladie initiale de seulement 9.3% (5 patients sur 54) et 2.4% (1 patient sur 41) dans la GVHa-CR et la GVHc-CR respectivement. Malgré la nature rétrospective de ces données, les résultats d’efficacité et de survie globale sont particulièrement intéressants dans la GVHa-CR et dans la GVHc-CR au regard des autres traitements de seconde ligne publiés.

En plus de l’analyse d’efficacité, notre étude s’est aussi intéressée à l’épargne cortisonique. En effet, les infections sont le principal risque de l’utilisation de corticoïdes à forte dose et au long cours, en particulier chez les patients immunodéprimés suite à l’allogreffe. Un traitement efficace de la GVH-CR permet d’arrêter la corticothérapie après une période de décroissance. Pour 5 des 7 patients répondeurs, la corticothérapie a pu être diminuée à une dose inférieure à 0,3mg/kg/j d’équivalent prednisone après un délai médian de 55,5 jours (47-77) et arrêtée au bout de 92 jours (71-102). Dans notre étude, lorsque les

patients avaient encore une dose élevée de corticoïdes (supérieure à 0,3mg/kg), on a recensé un total de 21 épisodes infectieux sévères de grade 3 et 4 de la CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events)54 et un cas de décès suite à un choc septique. A faible dose de corticoïdes (inférieure à 0,3mg/kg/j) seuls 4 épisodes infectieux graves sont survenus. Ainsi, sous réserve d’une courte période de suivi, il semble que l’efficacité du ruxolitinib permettrait indirectement de diminuer la morbi-mortalité infectieuse grâce à une diminution rapide des corticoïdes. Notre étude est la seule à analyser les bénéfices d’une épargne cortisonique sur le risque infectieux.

Dans notre étude, les effets secondaires principaux étaient les cytopénies se développant sous ruxolitinib et en particulier la thrombopénie. Les données de Zeiser et al. montrent également un profil habituel de toxicité, déjà observé dans les syndromes myéloprolifératifs.

L’efficacité de ce traitement dans la GVHc-CR n’a pu être réellement évaluée dans notre série, même si les 2 patients atteints d’un overlap syndrom étaient répondeurs. Les résultats de Zeiser et al sont aussi intéressants dans la GVHc-CR avec cependant peu de réponses complètes obtenues. Une autre série a rapporté les résultats de 12 patients traités par ruxolitinib pour une GVH chronique sclérodermiforme sévère, réfractaire aux corticoïdes et ayant reçu une moyenne de cinq autres immunosuppresseurs. Huit patients sur 12 avaient une amélioration des lésions mais aucune réponse complète n’avait été obtenue.55

Dans la population pédiatrique, peu de données sur l’utilisation du ruxolitinib sont disponibles. A ce jour la seule publication disponible rapporte un taux de 45% de réponse globale56 chez 11 enfants.

Limites de l’étude

Notre analyse présente plusieurs limites. Le ruxolitinib ayant été associé à un anti-IL 2 chez la moitié de nos patients, il est impossible d’attribuer l’efficacité à la molécule seule ou à l’association synergique. Par ailleurs, il s’agit d’une analyse rétrospective dans notre seul centre, ce qui peut entraîner un biais de sélection. Le faible effectif de patients ne permet pas d’évaluer l’efficacité selon le type d’organe atteint.

Perspectives

La proportion de patients répondeurs, la survie, les modalités de traitement, les effets secondaires, la perte de l’effet GVL sont à évaluer prospectivement. L’essai de phase II en cours, intitulé « A Study of Ruxolitinib in Combination With Corticosteroids for the Treatment of Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease (REACH1) » permettra probablement de déterminer la place du ruxolitinib, traitement prometteur de la GVH-CR.

Conclusion générale

Avec l’accroissement du nombre d’allogreffes de cellules souches, la prise en charge de la GVH, responsable d’une morbidité et d’une mortalité encore trop importantes, reste un enjeu majeur. Alors que la corticothérapie est le traitement de première intention, aucun consensus n’est à ce jour établi parmi les nombreuses secondes lignes d’immunosuppresseurs faute d’efficacité. Le ruxolitinib est un inhibiteur de Jak disponible sur le marché depuis 2015. Cette molécule prometteuse a montré une efficacité particulièrement intéressante et sera bientôt évaluée de manière prospective.

Bibliographie

1 Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bader P, Bonini C, Cesaro S, Dreger P et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Europe 2014: more than 40!000 transplants annually. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51: 786–792.

2 Storb R, Gyurkocza B, Storer BE, Sorror ML, Blume K, Niederwieser D et al. Graft-versus-host disease and graft-versus-tumor effects after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 1530–1538.

3 Couban S, Simpson DR, Barnett MJ, Bredeson C, Hubesch L, Howson-Jan K et al. A randomized multicenter comparison of bone marrow and peripheral blood in recipients of matched sibling allogeneic transplants for myeloid malignancies. Blood 2002; 100: 1525–1531.

4 Barker JN, Wagner JE. Umbilical-cord blood transplantation for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 526–532.

5 Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1813–1826. 6 Eapen M, Logan BR, Confer DL, Haagenson M, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ et al. Peripheral blood

grafts from unrelated donors are associated with increased acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease without improved survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2007; 13: 1461–1468.

7 Olsson R, Remberger M, Schaffer M, Berggren DM, Svahn B-M, Mattsson J et al. Graft failure in the modern era of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 537–543. 8 Mikulska M, Del Bono V, Viscoli C. Bacterial infections in hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation recipients. Curr Opin Hematol 2014; 21: 451–458.

9 Mohty M, Malard F, Abecassis M, Aerts E, Alaskar AS, Aljurf M et al. Revised diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a new classification from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51: 906–912.

10 Rosenthal J. Hematopoietic cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Blood Med 2016; Volume 7: 181–186.

11 Adhikari J, Sharma P, Bhatt VR. Risk of secondary solid malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and preventive strategies. Future Oncol Lond Engl 2015;

11: 3175–3185.

12 Barnes DW, Loutit JF, Micklem HS. ‘Secondary disease’ of radiation chimeras: a syndrome due to lymphoid aplasia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1962; 99: 374–385.

13 Billingham RE. The biology of graft-versus-host reactions. Harvey Lect 1966; 62: 21–78.

14 Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 945–956.

15 Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, Williams KM, Wolff D, Cowen EW et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic

Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21: 389–401.e1.

16 Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation 1974; 18: 295–304.

17 Jagasia M, Arora M, Flowers MED, Chao NJ, McCarthy PL, Cutler CS et al. Risk factors for acute GVHD and survival after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2012; 119: 296–307. 18 Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, Hingorani S, Sorror ML, Boeckh M et al. Reduced mortality

after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2091–2101.

19 Lee S-E, Cho B-S, Kim J-H, Yoon J-H, Shin S-H, Yahng S-A et al. Risk and prognostic factors for acute GVHD based on NIH consensus criteria. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 587–592. 20 Flowers MED, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, Lee SJ, Kiem H-P, Petersdorf EW et al. Comparative

analysis of risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease and for chronic graft-versus-host disease according to National Institutes of Health consensus criteria. Blood 2011; 117: 3214– 3219.

21 Westin JR, Saliba RM, De Lima M, Alousi A, Hosing C, Qazilbash MH et al. Steroid-Refractory Acute GVHD: Predictors and Outcomes. Adv Hematol 2011; 2011: 601953.

22 Blazar BR, Murphy WJ, Abedi M. Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12: 443–458.

23 Storb R, Deeg HJ, Whitehead J, Appelbaum F, Beatty P, Bensinger W et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine compared with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease after marrow transplantation for leukemia. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 729–735.

24 Ram R, Yeshurun M, Vidal L, Shpilberg O, Gafter-Gvili A. Mycophenolate mofetil vs. methotrexate for the prevention of graft-versus-host-disease--systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk Res 2014; 38: 352–360.

25 Deeg HJ. How I treat refractory acute GVHD. Blood 2007; 109: 4119–4126.

26 Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Preclinical models of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease: how predictive are they for a successful clinical translation? Blood 2016; 127: 3117–3126.

27 Martin PJ, Rizzo JD, Wingard JR, Ballen K, Curtin PT, Cutler C et al. First- and Second-Line Systemic Treatment of Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease: Recommendations of the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2012; 18: 1150– 1163.

28 Patriarca F, Sperotto A, Damiani D, Morreale G, Bonifazi F, Olivieri A et al. Infliximab treatment for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica 2004; 89: 1352–1359. 29 Kennedy GA, Butler J, Western R, Morton J, Durrant S, Hill GR. Combination antithymocyte

globulin and soluble TNFalpha inhibitor (etanercept) +/- mycophenolate mofetil for treatment of steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 2006; 37: 1143–1147. 30 García-Cadenas I, Valcárcel D, Martino R, Piñana JL, Novelli S, Esquirol A et al. Updated

Experience with Inolimomab as Treatment for Corticosteroid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013; 19: 435–439.

31 Ballesteros M, Ferrá C, Serrano D, Batlle M, Ribera JM, Díez-Martín JL. Antithymocyte globulin therapy for steroid-resistant acute graft versus host disease. Am J Hematol 2008; 83: 824–825. 32 Greinix HT, Worel N, Just U, Knobler R. Extracorporeal photopheresis in acute and chronic

graft-versus-host disease. Transfus Apher Sci 2014; 50: 349–357.

33 Lutz M, Mielke S. New perspectives on the use of mTOR inhibitors in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and graft-versus-host disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 82: 1171– 1179.

34 de Lavallade H, Mohty M, Faucher C, Fürst S, El-Cheikh J, Blaise D. Low-dose methotrexate as salvage therapy for refractory graft-versus-host disease after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 2006; 91: 1438–1440.

35 Furlong T, Martin P, Flowers MED, Carnevale-Schianca F, Yatscoff R, Chauncey T et al. Therapy with mycophenolate mofetil for refractory acute and chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009; 44: 739–748.

36 Leng C, Gries M, Ziegler J, Lokshin A, Mascagni P, Lentzsch S et al. Reduction of graft-versus-host disease by histone deacetylase inhibitor suberonylanilide hydroxamic acid is associated with modulation of inflammatory cytokine milieu and involves inhibition of STAT1. Exp Hematol 2006; 34: 776–787.

37 Moy RH, Huffman AP, Richman LP, Crisalli L, Wang XK, Hoxie JA et al. Clinical and immunologic impact of CCR5 blockade in graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. Blood 2017;

129: 906–916.

38 Munneke JM, Spruit MJA, Cornelissen AS, van Hoeven V, Voermans C, Hazenberg MD. The Potential of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells as Treatment for Severe Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease: A Critical Review of the Literature. Transplantation 2016; 100: 2309–2314. 39 Kim B-S, Nishikii H, Baker J, Pierini A, Schneidawind D, Pan Y et al. Treatment with agonistic DR3 antibody results in expansion of donor Tregs and reduced graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2015; 126: 546–557.

40 Stem Cell Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Allogeneic peripheral blood stem-cell compared with bone marrow transplantation in the management of hematologic malignancies: an individual patient data meta-analysis of nine randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 5074–5087.

41 Vogelsang GB. How I treat chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2001; 97: 1196–1201.

42 Sullivan KM, Witherspoon RP, Storb R, Deeg HJ, Dahlberg S, Sanders JE et al. Alternating-day cyclosporine and prednisone for treatment of high-risk chronic graft-v-host disease. Blood 1988;

72: 555–561.

43 Marleau AM, Sarvetnick N. T cell homeostasis in tolerance and immunity. J Leukoc Biol 2005;

78: 575–584.

44 van den Brink MR, Moore E, Ferrara JL, Burakoff SJ. Graft-versus-host-disease-associated thymic damage results in the appearance of T cell clones with anti-host reactivity. Transplantation 2000; 69: 446–449.

45 Harrison C, Kiladjian J-J, Al-Ali HK, Gisslinger H, Waltzman R, Stalbovskaya V et al. JAK Inhibition with Ruxolitinib versus Best Available Therapy for Myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012;

46 Teshima T. JAK inhibitors: a home run for GVHD patients? Blood 2014; 123: 3691–3693.

47 Spoerl S, Mathew NR, Bscheider M, Schmitt-Graeff A, Chen S, Mueller T et al. Activity of therapeutic JAK 1/2 blockade in graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2014; 123: 3832–3842.

48 Garnett C, Apperley JF, Pavlů J. Treatment and management of graft-versus-host disease: improving response and survival. Ther Adv Hematol 2013; 4: 366–378.

49 Choi J, Cooper ML, Alahmari B, Ritchey J, Collins L, Holt M et al. Pharmacologic Blockade of JAK1/JAK2 Reduces GvHD and Preserves the Graft-Versus-Leukemia Effect. PLoS ONE 2014;

9: e109799.

50 Rowlings PA, Przepiorka D, Klein JP, Gale RP, Passweg JR, Jean Henslee-Downey P et al. IBMTR Severity INDEX FOR GRADING ACUTE GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE: RETROSPECTIVE COMPARISON WITH GLUCKSBERG GRADE. Br J Haematol 1997; 97: 855–864.

51 Saliba RM, Couriel DR, Giralt S, Rondon G, Okoroji G-J, Rashid A et al. Prognostic value of response after upfront therapy for acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2012; 47: 125–131. 52 Zeiser R, Burchert A, Lengerke C, Verbeek M, Maas-Bauer K, Metzelder SK et al. Ruxolitinib in

corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a multi-center survey. Leukemia 2015. doi:10.1038/leu.2015.212.

53 Wolff D, Schleuning M, von Harsdorf S, Bacher U, Gerbitz A, Stadler M et al. Consensus Conference on Clinical Practice in Chronic GVHD: Second-Line Treatment of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011; 17: 1–17.

54 Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program NCI. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v3.0 Online Instructions and Guidelines.

https://webapps.ctep.nci.nih.gov/webobjs/ctc/webhelp/welcome_to_ctcae.htm. Accessed May 19, 2009. .

55 Hurabielle C, Sicre de Fontbrune F, Moins-Teisserenc H, Robin M, Jachiet M, Coman T et al. Efficacy and tolerance of ruxolitinib in refractory sclerodermatous chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Br J Dermatol 2017. doi:10.1111/bjd.15593.

56 Khandelwal P, Teusink-Cross A, Davies SM, Nelson AS, Dandoy CE, El-Bietar J et al. Ruxolitinib as Salvage Therapy in Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease in Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2017. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.03.029.

Annexe

correspondence)

Ruxolitinib)as)a)promising)treatment)for)corticosteroid5

refractory)graft5versus5host)disease)

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the main cause of mor-bidity and mortality in patients having undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Although there is a consensus on the first-line use of high doses of corticosteroids to treat GVHD, 30–40% of patients will dis-play corticosteroid-refractory GVHD (CR-GVHD). This condition is associated with a poor prognosis (i.e. a long-term survival rate of only 5–30%) (Martin et) al, 2012). Immunosuppressants and immunomodulators [such as anti-interleukin 2 (IL2) receptor antibodies, anti-thymocyte glob-ulins, mycophenolate mofetil, mTOR inhibitors, low-dose methotrexate, rituximab, alemtuzumab, anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antibodies, pentostatin, mesenchymal stem cells and extracorporeal photopheresis] (Garnett et)al, 2013) are the main salvage therapy options for CR-GVHD but lack sat-isfactory effectiveness. None of these treatments has been established as a standard second-line option. The combina-tion of corticosteroids with other immunosuppressant agents is associated with high toxicity. Furthermore, broad immunosuppression leads to both secondary infectious com-plications and mitigation of the graft-versus-leukaemia (GVL) effect. Hence, there is a strong need for targeted therapies that yield long-lasting responses with as little immunosup-pression as possible. Ruxolitinib is an orally administered tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor used in the treatment of myelofibrosis (Harrison et)al, 2012). Experiments in an ani-mal model have shown that, by inhibiting the JAK-STAT sig-nalling pathway (involved in the development of T-cell alloreactivity), ruxolitinib is effective in GVHD and does not affect GVL activity (Choi et)al, 2014).

We performed a retrospective study of 10 CR-GVHD patients treated with ruxolitinib in our institution (Depart-ment of Haematology, Amiens University Hospital, Amiens, France), between May 2014 and July 2015. Acute CR-GVHD was defined by disease progression after 3 days, with stable disease at 7 days and an incomplete response to 2 mg/kg/day methylprednisolone at 14 days (Deeg, 2007). Acute GVHD was staged according to the Glucksberg system (Rowlings et) al, 1997). Overlap syndrome was defined as the concomi-tant occurrence of features of chronic GVHD and acute GVHD, according to the National Institutes of Health con-sensus criteria (Filipovich et)al, 2005).

Complete response was defined as the complete resolution of all signs and symptoms of GVHD in all organs. A partial response was defined as an improvement (by at least one

Table I. Characteristics of 10 CR-GVHD patients treated with a ruxolitinib-based regimen.

Age, median (range), years 52 (26–65) Gender Male 7 Female 3 Diagnosis Acute leukaemia 4 Myelodysplastic syndrome 2 Primary myelofibrosis 2 Hodgkin lymphoma 1

Myelodysplastic myeloproliferative neoplasm 1 Donor type HLA-matched, related 5 HLA-matched, unrelated 5 Regimen intensity Reduced-intensity 10 Acute GVHD 8 Organ involved Skin 6 Gastrointestinal tract 7 Liver 3

Grade 3 and over 6

Overlap syndrome 2

CR-GVHD, corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HLA, human leucocyte antigen.

Glucksberg stage) in one or more organs and the absence of progression in any other organs (Saliba et)al, 2012).

Infectious adverse events and hematologic toxicity were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/protoc olDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf).

The characteristics of the study population are summa-rized in Table I. The 10 patients with CR-GVHD (three women and seven men) had a median (range) age of 52 (26–65) years. Five patients had received a graft from a related human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-matched donor, and five patients had received a graft from an unrelated HLA-matched donor. All patients received reduced-intensity con-ditioning with fludarabine and busulfan. This was combined with sequential therapy for refractory acute leukaemia in two cases and fludarabine-melphalan conditioning in one case. The patients received prophylactic combination treatment with anti-thymocyte globulins, ciclosporin and (in some

Correspondence*

Table II. Results

Number of Number of Other Time Time to a Time to grades 3–4 grades 3–4

Previous treatments to best Co dose Co infections infections at a Follow- GVHD for CR- Best response <0 3 mg/kg withdrawal at a high Co dose up Current Patient therapies GVHD* response (days) (days) (days) Co dose <0 3 mg/kg (days) status

1 Co None PR 31 NA NA 1 NA 52 Dead/septic

shock

2 Co Anti-IL2R PR 56 77 102 3 3 345 Dead/relapse

3 Co None CR 25 60 123 0 0 133 Alive

4 Co None CR 11 47 91 1 0 111 Alive

5 Co + anti-IL2R None CR 31 51 71 6 1 150 Alive

6 Co + anti-IL2R None CR 41 NA NA 4 NA 47 Dead/Septic

shock

7 Co + anti-IL2R None CR 37 NA 92 2 0 135 Alive

8 Co Anti-IL2R Failure NA NA NA 1 NA 455 Alive

9 Co + anti-TNFR None Failure NA NA NA 2 NA 405 Alive

10 Co Anti-TNFR Failure NA NA NA 1 NA 42 Dead/

GVHD

Anti-IL2R, anti-IL2 receptor antibody; anti-TNFR, anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor antibody; Co, corticosteroids; CR-GVHD, corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host-disease; CR, complete response; NA, not applicable; PR, partial response. *Other than corticosteroids.

cases) methotrexate. Eight patients had acute GVHD and two had overlap syndrome (Table I).

All patients underwent first-line (n = 6) or second-line (n = 4) treatment with ruxolitinib 10 mg bid. The median treatment duration was 134 days. Ruxolitinib was given alone in seven patients, combined with an anti-IL2 receptor anti-body in two cases and with an anti-TNF alpha antibody in one case.

Seven patients (five of the eight patients with acute CR-GVHD and both of the patients with overlap syndrome) responded after a median (range) time interval of 31 (11–56) days. There were five complete responses. For five of the responders, we were able to (i) decrease the corticosteroid dose to below 0 3 mg/kg/day after a median (range) of 55 5 (47–77) days, and (ii) withdraw corticosteroids after a med-ian of 92 (71–102) days. A reduction in the prednisone dose to below 0 3 mg/kg/day was associated with a decrease in the frequency of infectious events of severe grade 3 or over (Table II). Platelet loss was the most common form of cytopenia. Grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia was observed in 7 of the 10 patients, whereas severe neutropenia and anaemia was reported in four cases. With a median follow-up of 134 days, median survival of the cohort study hasn’t been reached.

A standardized treatment is not available for acute and chronic CR-GVHD. Ruxolitinib is a promising targeted ther-apy, with encouraging results in our cohort: 70% of the patients responded to the drug after about a month. A retro-spective study assessed the use of ruxolitinib in 95 patients with GVHD (Zeiser et*al, 2015). The overall response rate

was high (81 5% and 85 4%, for acute and chronic CR-GVHD, respectively). These data are consistent with our findings, although none of the patients in our cohort had chronic GVHD.

The infectious risk (enhanced by prolonged exposure to high doses of corticosteroid) remains an important cause of non-relapse-related mortality following allogeneic HSCT. In our cohort, we observed a number of severe infections in patients taking high doses of corticosteroid, including two deaths due to septic shock.

For the seven responders, we were able to decrease the prednisone dose to below 0 3 mg/kg/day in a median of 55 5 (47–77) days. After cautious dose reduction, we were able to withdraw corticosteroids after a median of about 3 months. Achieving a low-dose corticosteroid regimen may help to avoid severe infections. Most of the patients had severe thrombocytopenia (a well-known ruxolitinib-related adverse drug reaction) but there were no case of haemorrhage. At baseline, six patients already had an abnormally low platelet count (i.e. below 10 9 109/l).

We were unable to assess any loss of GVL activity. We noted one case of relapsed acute leukaemia during combina-tion treatment with ruxolitinib and an anti-IL2 receptor antagonist. A longer follow-up period with more data would be informative. Zeiser et*al (2015) reported loss of GVL effect in 9 3% of patients with acute CR-GVHD and in 2 4% of patients with chronic CR-GVHD. Ruxolitinib is a valuable drug, with efficacy in CR-GVHD. Prospective clinical trials of JAK-inhibitors might enable a treatment strategy in CR-GVHD to be defined.

Correspondence*

Author*contributions* Jean-Pierre Marolleau

DA, DL, AC, BR, JPM and BG performed the research. DA Berengere Gruson

Hematologie,*Centre*Hospitalier*Universitaire*d’Amiens,*Amiens,*

and BG analysed and interpreted the data. DA and BG wrote

France.*

the manuscript.

E=mail:*deborah.assouan@hotmail.fr*

Deborah Assouan

Delphine Lebon Keywords: graft-versus-host disease, hematopoietic stem cell

Amandine Charbonnier transplantation, ruxolitinib, malignant haematology, corticosteroids

Bruno Royer

References*

Choi, J., Cooper, M.L., Alahmari, B., Ritchey, J., Collins, L., Holt, M. & DiPersio, J.F. (2014) Pharmacologic blockade of JAK1/JAK2 reduces GvHD and preserves the graft-versus-leukemia effect. PLoS*ONE, 9, e109799.

Deeg, H.J. (2007) How I treat refractory acute GVHD. Blood, 109, 4119–4126.

Filipovich, A.H., Weisdorf, D., Pavletic, S., Socie, G., Wingard, J.R., Lee, S.J., Martin, P., Chien, J., Przepiorka, D., Couriel, D., Cowen, E.W., Dinndorf, P., Farrell, A., Hartzman, R., Hen-slee-Downey, J., Jacobsohn, D., McDonald, G., Mittleman, B., Rizzo, J.D., Robinson, M., Schubert, M., Schultz, K., Shulman, H., Turner, M., Vogelsang, G. & Flowers, M.E. (2005)

National Institutes of Health consensus

development project on criteria for clinical tri-als in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biology* of* Blood* and* Marrow* Transplantation,* 11, 945– 956.

Garnett, C., Apperley, J.F. & Pavlu, J. (2013) Treatment and management of graft-versus-host

disease: improving response and survival. Thera= peutic*Advances*in*Hematology,*4, 366–378. Harrison, C., Kiladjian, J.J., Al-Ali, H.K.,

Gisslin-ger, H., Waltzman, R., Stalbovskaya, V., McQuitty, M., Hunter, D.S., Levy, R., Knoops, L., Cervantes, F., Vannucchi, A.M., Barbui, T. & Barosi, G. (2012) JAK inhibition with ruxoli-tinib versus best available therapy for myelofi-brosis. New* England* Journal* of* Medicine, 366, 787–798.

Martin, P.J., Rizzo, J.D., Wingard, J.R., Ballen, K., Curtin, P.T., Cutler, C., Litzow, M.R., Nieto, Y., Savani, B.N., Schriber, J.R., Shaughnessy, P.J., Wall, D.A. & Carpenter, P.A. (2012) First- and second-line systemic treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: recommendations of the American Society of Blood and Marrow Trans-plantation. Biology* of* Blood* and* Marrow* Trans=plantation,*18, 1150–1163.

Rowlings, P.A., Przepiorka, D., Klein, J.P., Gale, R.P., Passweg, J.R., Henslee-Downey, P.J., Cahn, J.Y., Calderwood, S., Gratwohl, A., Socie, G., Abecasis, M.M., Sobocinski, K.A., Zhang, M.J. & Horowitz, M.M. (1997) IBMTR Severity Index for grading acute graft-versus-host disease:

retrospective comparison with Glucksberg grade. British*Journal*of*Haematology,*97, 855–864. Saliba, R.M., Couriel, D.R., Giralt, S., Rondon, G., Okoroji, G.J., Rashid, A., Champlin, R.E. & Alousi, A.M. (2012) Prognostic value of response after upfront therapy for acute GVHD. Bone* Marrow*Transplantation,*47, 125–131. Zeiser, R., Burchert, A., Lengerke, C., Verbeek, M.,

Maas-Bauer, K., Metzelder, S.K., Spoerl, S., Ditschkowski, M., Ecsedi, M., Sockel, K., Ayuk, F., Ajib, S., de Fontbrune, F.S., Na, I.K., Penter, L., Holtick, U., Wolf, D., Schuler, E., Meyer, E., Apostolova, P., Bertz, H., Marks, R., Lubbert,€* M., W€asch, R., Scheid, C., Stolzel,€ F., Orde-mann, R., Bug, G., Kobbe, G., Negrin, R., Brune, M., Spyridonidis, A., Schmitt-Gr€aff, A., van der Velden, W., Huls, G., Mielke, S., Grigo-leit, G.U., Kuball, J., Flynn, R., Ihorst, G., Du, J., Blazar, B.R., Arnold, R., Kroger,€ N., Passweg, J., Halter, J., Socie, G., Beelen, D., Peschel, C., Neubauer, A., Finke, J., Duyster, J. & von Bubnoff, N. (2015) Ruxolitinib in

corticos-teroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease after

allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a multicen-ter survey. Leukemia, 29, 2062–2068.

Classification de la GVH chronique

Chaque organe est évalué de manière à lui attribuer un score par organe, entre 0 et 3 avec : ,! Score 0 : pas de symptomatologie

,! Score 1 : symptômes légers

,! Score 2 : symptômes modérés avec gêne fonctionnelle partielle ,! Score 3 : atteinte sévère avec gêne fonctionnelle majeure La gravité de la GVH est définie comme suit :

1. GVH légère ou de bas risque :

- Atteinte de score 1 d’un ou deux organes - Pas d’atteinte pulmonaire

- Score de Karnofsky 80 %

2. GVH modérée ou de risque intermédiaire : - Atteinte de score 2 d’un organe

- Ou atteinte de score 1 de deux ou trois organes - Ou atteinte pulmonaire de score 1

- GVH persistante (continuum entre GVH aiguë puis GVH chronique) ou thrombopénie

- Karnofsky < 80 %. 3. GVH de haut risque ou sévère :

- Atteinte de score 3 d’un organe au moins - Ou atteinte pulmonaire de score 2 ou 3 - GVH persistante et thrombopénie - Karnofsky < 80 %.