EFFET DES VERS DE TERRE EXOTIQUES SUR LES COMMUNAUTÉS DES 2

PLANTES DE SOUS-BOIS DE FORÊT DU SUD DU QUÉBEC 3 4 5 par 6 7 8 Claude Ndabarushimana 9 10 11

mémoire présenté au Département de biologie en vue 12

de l’obtention de grade de maître ès sciences (M.Sc.) 13

14 15 16

FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES 17 UNIVERSITÉ DE SHERBROOKE 18 19 20 21

Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada, juin 2019 22

23 24

25

Le 18 juin 2019 26

27

le jury a accepté le mémoire de M. Claude Ndabarushimana dans sa version finale. 28 29 Membres du jury 30 Pr Bill Shipley 31 Directeur de recherche 32 Département de Biologie 33 34

Pre Sophie Calmé 35 Évaluatrice interne 36 Département de Biologie 37 38 39 40 41 Pr Mark Vellend 42 Président-rapporteur 43 Département de Biologie 44

iv 45

SOMMAIRE 46

47

Le présent mémoire traite de deux approches permettant d’aborder les effets de l’invasion de vers 48

de terre exotiques dans les forêts du sud du Québec : il s’agit d’un échantillonnage des vers de 49

terre et des espèces herbacées de sous-bois de forêt, et d’une étude expérimentale faite en 50

mésocosmes. 51

52

En premier lieu nous avons réalisé un échantillonnage des vers de terre et des espèces herbacées 53

de sous-bois de forêt du parc écoforestier de Johnville. On est parti de l’hypothèse de travail 54

selon laquelle la structure de communautés des espèces herbacées du sous-bois de forêt est 55

déterminée par les abondances des vers de terre et en essayant de répondre à la question de savoir 56

s’il existe une corrélation entre la structure et la composition des communautés des espèces de 57

plantes de sous-bois et l’abondance des vers de terre du parc écoforestier de Johnville, 58

indépendamment des variables abiotiques et historiques. Ici, nous donnerons les détails sur des 59

résultats issus de l’analyse des données d’un échantillonnage de vers de terre et d’espèces 60

herbacées du sous-bois de forêt réalisé sur 87 placettes dans trois zones du parc, tout au long de 61

18 transects perpendiculaires aux chemins se trouvant dans notre zone d’étude. On a trouvé que 62

les vers de terre sont présents en grande quantité dans les zones Récréation et Plantation tandis 63

qu’ils sont quasiment absents dans la zone Conservation et que les espèces herbacées du boisé de 64

Johnville sont structurées en trois communautés réparties respectivement sur les 3 secteurs de ce 65

territoire. Les résultats tirés des analyses statistiques montrent comme plusieurs autres études 66

qu’il y a une association entre l’abondance des vers de terre et la structure de la végétation du 67

sous-bois au parc écoforestier de Johnville. Contrairement à nos attentes, nous n’avons pas 68

détecté un lien entre les perturbations anthropiques actuelles (distance des routes et sentiers) et 69

l’abondance de vers de terre. Après avoir analysé les données de l’échantillonnage, il se trouve 70

que l’abondance des vers de terre est différente d’une zone à l’autre. Comme la répartition des 71

abondances des vers de terre, les espèces herbacées du parc sont structurées en respectant la 72

zonalité de ce site, ce qui nous amène à croire que c’est l’historique de chaque zone qui est 73

déterminant et non les abondances de vers de terre en place. 74

v 75

En deuxième lieu, j’ai réalisé une étude expérimentale faite en mésocosmes dans des conditions 76

contrôlées. Les forêts du Canada et du nord des États-Unis connaissent des changements des 77

communautés des espèces herbacées du sous-bois reliée à une invasion des vers de terre 78

exotiques introduits à l’époque coloniale dans ces forêts qui se sont régénérées, en absence de 79

vers de terre, au lendemain de la glaciation du Wisconsin il y a plus de 10000 ans. Dans cette 80

étude nous essayons de comprendre si ces vers invasifs affectent les plantes herbacées de ces 81

forêts et si oui, par quels mécanismes? 82

83

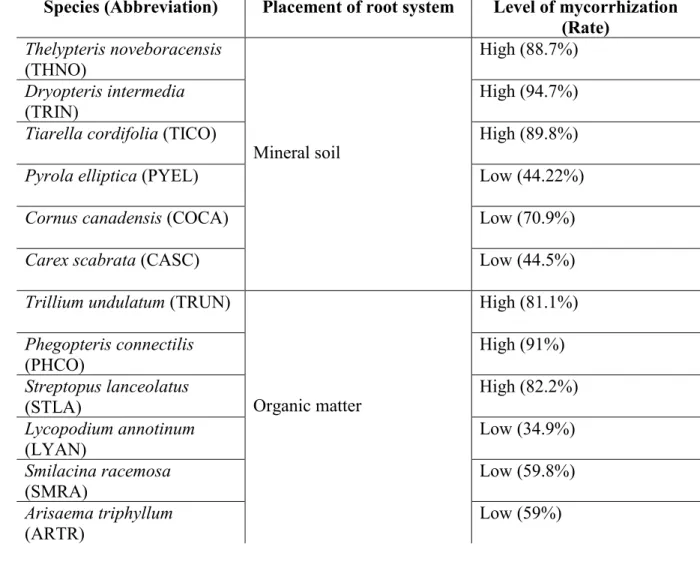

Pour comprendre ces mécanismes, nous avons privilégié l’approche par analyse des traits 84

fonctionnels en choisissant des espèces végétales qui possèdent des traits fonctionnels qui 85

peuvent accentuer ou diminuer les effets négatifs hypothétiques créés par des changements 86

environnementaux provoqués par les vers de terre. Ainsi nous avons mis en place un dispositif 87

expérimental fait de 96 mésocosmes dans lesquels nous avons transplanté 12 espèces herbacées 88

représentatives d’une communauté de sous-bois sélectionnées selon leurs abondances pour 89

s’assurer d’avoir suffisamment d’individus, en utilisant deux traits: (i) la position d’enracinement 90

des plantes (2 niveaux, soit dans la matière organique, soit dans le sol minéral) et (ii) le taux de 91

mycorhization des racines (2 niveaux, fortement mycorhizées ou faiblement mycorhizées). 92

93

Après deux saisons de croissance, seule l’espèce Phegopteris connectilis a répondu de façon 94

significative à l’effet des vers de terre et sa biomasse a augmenté en présence de ceux-ci. Si 95

l’effet des vers de terre sur les sols dans nos mésocosmes est semblable aux effets sur les sols 96

agricoles, il est possible que l’effet positif sur cette espèce soit dû à l’augmentation de fertilité 97

causée par l’augmentation de décomposition de la matière organique du sol. Si cela est le cas, 98

nous ne pouvons cependant pas expliquer pourquoi les autres espèces n’ont pas répondu de la 99

même façon. 100

Mots clés : Invasion de vers de terre, espèces herbacées, plantes de sous-bois, forêt. 101

vi

REMERCIEMENTS 102

103

Je te remercie Éternel Dieu pour ton amour, pour ta miséricorde et pour m’avoir assisté tout au 104

long de mes études. Grâce à toi, j’ai l’espérance d’un avenir meilleur! 105

106

Je tiens à remercier du fond du cœur mon directeur de recherche Dr. John William Shipley. Avoir 107

placé sa confiance en moi durant tout le cheminement de ce programme m’a permis d’avoir 108

motivation et persévérance du début jusqu’à la fin de mes études graduées. Avec monsieur Bill 109

Shipley, j’ai non seulement appris l’écologie fonctionnelle mais aussi comment un scientifique 110

doit avoir un esprit critique avec une rigueur scientifique inébranlable. J’apprécie aussi le côté 111

humain de ce grand professeur, je n’oublierai pas les soirées auxquelles j’ai été convié à son 112

domicile en compagnie des étudiants gradués de son laboratoire. L’ambiance y était chaleureuse, 113

le tout dans une atmosphère agréablement détendue. 114

115

Par cette occasion, je tiens également à remercier les professeurs Mark Vellend et Robert 116

Bradley, tous deux membres de mon comité de conseillers, pour leurs conseils et leur aide. Je 117

remercie du fond du cœur les étudiants Michael, Françoise, Laurent et Lee pour leur aide 118

également. 119

120

Pour terminer, je remercie Micheline, Jean Pierre, ma famille, mes amis et toutes les personnes 121

qui de près ou de loin ont contribué au bon déroulement de mes études à la maîtrise en Biologie. 122

vii

TABLE DES MATIÈRES 123 124 125 SOMMAIRE ... iv 126 REMERCIEMENTS ... vi 127

TABLE DES MATIÈRES ... vii 128

LISTE DES TABLEAUX ... ix 129

LISTE DES FIGURES ... x 130 CHAPITRE 1 ... 1 131 INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE ... 1 132 CHAPITRE 2 ... 7 133

La structure d'une communauté végétale herbacée de sous-bois de forêt et sa relation avec 134

l'abondance des vers de terre invasifs. ... 7 135

Abstract ... 9 136

1. Introduction ... 10 137

2. Materials and Methods ... 13 138

Presentation of the study area ... 13 139 Sampling ... 13 140 3. Statistical analyses ... 16 141 4. Results ... 17 142 Earthworm community ... 17 143

Influence of earthworm abundance on the structure of forest understory plant 144 communities ... 18 145 5. Discussion ... 20 146 6. Acknowledgements ... 23 147 7. References ... 24 148 CHAPITRE 3 ... 27 149

Effet des vers de terre exotiques sur les plantes de sous-bois de forêt. ... 27 150 Abstract ... 28 151 1. Introduction ... 30 152 2. Methods ... 34 153 Experimental design ... 34 154 Experimental treatments ... 35 155

viii

Application of treatments ... 38 156

Initial and final above-ground biomass measurement ... 39 157 3. Statistical analyses ... 41 158 4. Results ... 41 159 Survival: ... 41 160 Growth: ... 43 161 5. Discussion ... 46 162 6. Acknowledgements ... 48 163 7. References ... 49 164 CHAPITRE 4 ... 53 165

DISCUSSION ET CONCLUSION GÉNÉRALE ... 53 166 ANNEXES ... 56 167 BIBLIOGRAPHIE ... 60 168 169 170

ix

LISTE DES TABLEAUX 171

172

CHAPITRE 2 173

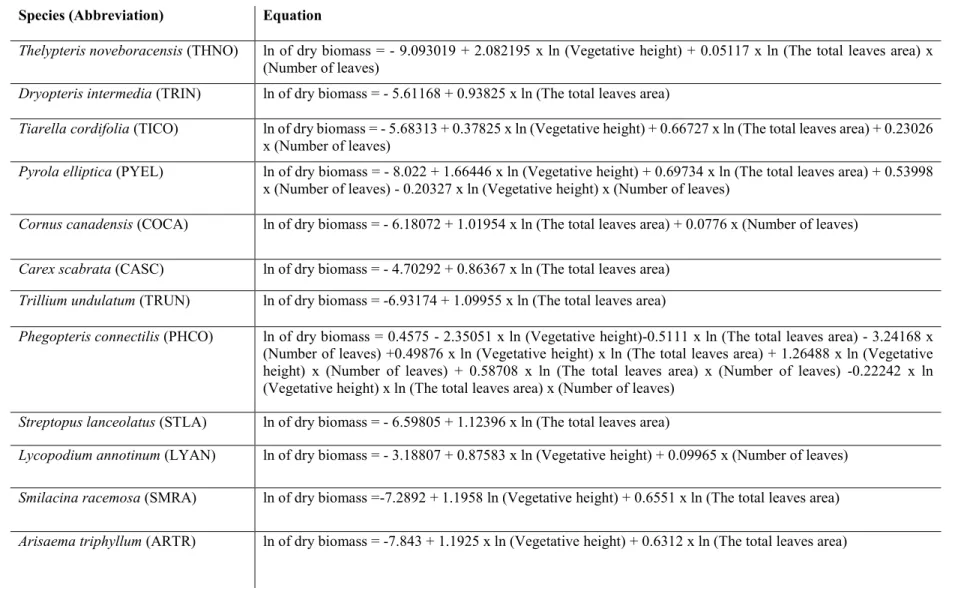

Table 1. Species according to root placement and mycorrhization rate………..…...37 174

Table 2. Prediction equation of the initial biomass of twelve species used in the 175

experiment.……….……….…….……….40 176

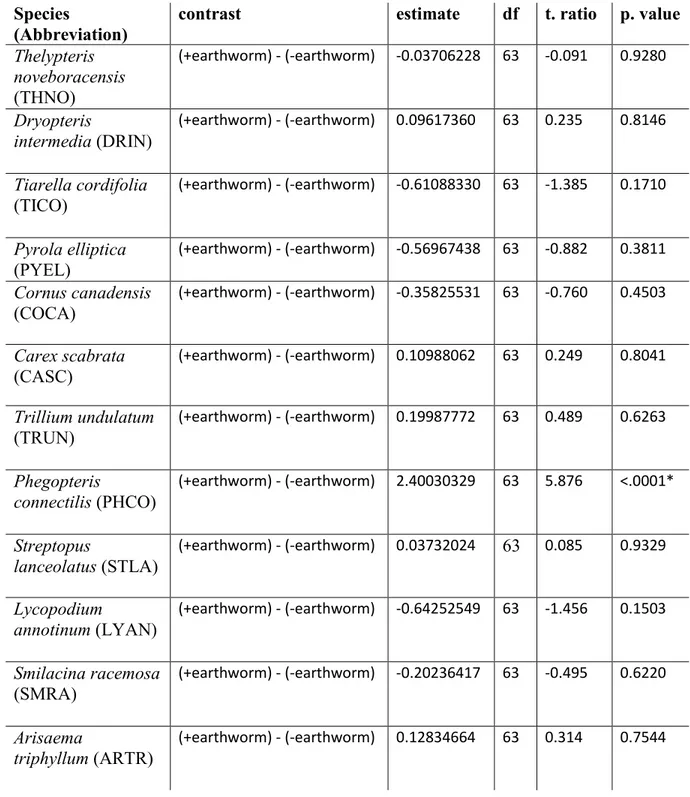

Table 3. Statistical results of multiple ANOVAs to determine the effect of earthworms 177

depending on the plant species. ……….………...45 178

x

LISTE DES FIGURES 180

181

CHAPITRE 2 182

Figure 1. 1945 aerial photo of Johnville ecoforest park………....………..…….14 183

Figure 2. Sampling plan and illustration of earthworm abundances per plot. ………..……18 184

Figure 3. Ordination of understory plant community……….…...….20 185

186

CHAPITRE 3 187

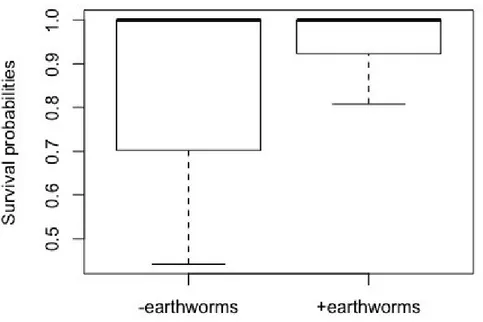

Figure 4. Probabilities of survival of species with or without earthworms……….……...….42 188

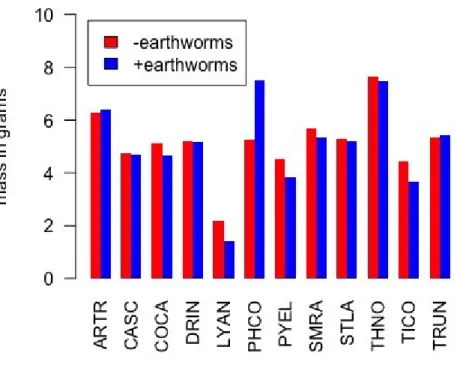

Figure 5. Species growth by treatment type. ……….…….……….….…….43 189

190 191

1 CHAPITRE 1 192 INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE 193 194 195

Au Canada et dans la partie septentrionale des États-Unis, il est généralement admis que la 196

plupart des vers de terre indigènes n’ont pas survécu aux glaciations du Wisconsin. La glaciation 197

du Wisconsin a décimé la quasi-totalité des vers de terre indigènes de cette partie du continent. 198

La très grande majorité des espèces de vers de terre qui vivent maintenant dans le sol au Canada 199

et les régions nordiques des États-Unis résultent des récentes introductions faites par les colons 200

européens (Reynolds 1994). Ainsi, la majorité des espèces de vers de terre dans les parties 201

nordiques de l’Amérique de Nord font partie de ces espèces exotiques envahissantes. La 202

dispersion des vers de terre par les humains est la plus importante puisque la dispersion naturelle 203

des vers de terre est très lente, avec une vitesse de propagation allant de 5 à 10 mètres par an 204

selon la région (Addison 2009, Cameron et Bayne 2009). Les sols contenant les vers de terre, 205

même aujourd’hui, sont surtout associés aux activités humaines (agriculture, horticulture, etc). 206

Leur abondance relative et composition spécifique sont fortement liées au type de sol, climat, 207

végétation, topographie, historique de l’utilisation des sols et surtout à son historique 208

d’envahissement par des espèces exotiques (Hendrix et Bohlen, 2002). 209

210

Même si les vers de terre se trouvent de plus en plus en milieu forestier, il y a encore plusieurs 211

forêts sans vers de terre (Hedrix et Bohelen, 2002). C’est le cas notamment des endroits qui 212

n’ont pas été soumis à une influence humaine après la glaciation. L’intérieur des forêts semble 213

relativement peu affecté par l'invasion des vers de terre: la probabilité d'apparition de vers de 214

terre et l'étendue de la propagation augmentent en fonction de la proximité des routes et des 215

aménagements (Cameron et Bayne 2009, Sackett et al, 2011; Shartelletal, 2013). On les trouve 216

généralement sous une forte densité dans des terres agricoles, à proximité des routes et autour des 217

lacs utilisés pour la pêche, ce qui laisse penser que leur introduction a été facilitée par les 218

activités humaines telles que le transport par le biais des pneus ou tout simplement apportés pour 219

être utilisés comme des appâts de pêche (Hendrix et Bohelen, 2002). 220

2 221

Les vers de terre sont souvent appelés des « ingénieurs écosystémiques » puisqu’ils modifient 222

beaucoup les attributs physiques et biolniques du sol. Vu que différentes espèces végétales sont 223

adaptées différemment à ces attributs du sol, il est possible que l’envahissement des sols 224

forestiers par les vers de terre exotiques puisse modifier également la structure des communautés 225

végétales. En particulier, les vers de terre modifient directement le taux de décomposition de la 226

litière, la structure physique du sol et les communautés microbiennes du sol. L'ampleur de la 227

perte de l’horizon organique du sol de forêt et les conséquences pour les communautés végétales 228

de la forêt indigène dépendent de l'espèce de vers de terre (Hale et al., 2005). Cela étant, il est 229

raisonnable de croire que l’introduction des vers dans les écosystèmes qui se sont développés 230

sans ces espèces au lendemain de la dernière glaciation auront des répercussions importantes. 231

L’activité des vers de terre n’est pas toujours bénéfique aux plantes. Après l'envahissement, les 232

vers de terre modifient la structure de horizons du sol, la disponibilité des éléments nutritifs, et le 233

biote du sol. Parmi les conséquences attribuables aux vers de terre exotiques envahissants, on 234

trouve notamment la modification de la structure du sol forestier (McLean et Parkinson 1997a) et 235

la réduction ou l’éradication de la couche de litière (Edwards et Bohlen, 1996). Ceci peut 236

affecter les espèces de différentes façons; les espèces herbacées du sous-bois varient en fonction 237

de leur placement du système racinaire dans le sol et les espèces dont les racines sont limitées à la 238

couche organique peuvent être affectées de façon négative alors que celles dont les racines sont 239

limitées au sol minéral peuvent être affectées de façon positive. Ensuite, d’après Wardle (2002), 240

quand les vers de terre transforment la structure d'un sol dominé par les champignons en un sol 241

dominé par les bactéries, les relations cruciales entre les racines et la plante sont affectées. La 242

perte de mycorhizes peut entraîner des effets négatifs sur la fonction racinaire des plantes 243

(Lawrence et al., 2003), la croissance des plantes (Gundale, 2002) et des assemblages de 244

communautés végétales (Holdsworth et al., 2007). Donc, les espèces peuvent être affectées 245

différemment selon leurs taux de mycorhization. 246

247

En connaissance de ce qui précède, nous avons voulu dans le premier chapitre de ce mémoire 248

vérifier l’hypothèse selon laquelle l’abondance des vers de terre influence la structure des 249

3

communautés de plantes de sous-bois de forêts indépendamment des autres facteurs abiotiques et 250

biotiques, incluant l’historique du site. 251

Pour ce faire, nous avons posé deux questions : 252

1) Existe-t-il une corrélation entre la structure et la composition des communautés des 253

espèces de plantes de sous-bois et l’abondance des vers de terre? 254

2) Si oui, cette corrélation existe-elle indépendamment des variables abiotiques et 255

historiques? Autrement dit, est-ce que cette corrélation disparait en contrôlant pour des 256

variables abiotique et historiques? 257

258

Quand l’abondance des espèces introduites devient importante, et quand l’impact de ces espèces 259

introduites sur ces écosystèmes devient majeur, on parle d’espèces exotiques invasives. 260

Cependant, l'histoire de l'utilisation des terres et d'autres facteurs spécifiques du site peuvent 261

confondre les études comparant les sites sans vers avec les sites envahis par les vers (Callaham et 262

Blair 1999 ; Jordan et al. 1999 ; Cortez et al. 2000 ; Bohlen et al. 2004a; Hale et al, 2005). 263

Les vers de terre affectent directement la structure et la fonction de l'écosystème en ingérant, 264

modifiant et mélangeant la matière organique et le sol minéral (Lavelle et al. 1998), modifiant 265

ainsi la structure, la chimie et la biologie du sol (Devliegher et Verstraete 1997; Hale et al, 2005). 266

Les espèces végétales du sous-bois varient dans le placement de leurs systèmes racinaires. 267

Certaines espèces placent leurs racines uniquement dans la couche superficielle de litière, 268

certaines uniquement dans le sol minéral, et certaines dans les deux. Donc, il est raisonnable de 269

croire que l’abondance des espèces végétales du sous-bois ayant ces différences dans le 270

placement de leurs systèmes racinaires seront affectées différemment par l’invasion des vers de 271

terre. Ensuite, nous savons que ces vers de terre modifient la structure des horizons du sol, la 272

disponibilité des éléments nutritifs, et la faune du sol. 273

Les vers de terre font partie de la communauté détritivore, consommant la litière de feuilles et 274

augmentant les taux de décomposition. L'ampleur des impacts des envahissements de vers de 275

terre sur les sols forestiers dépend de l'assemblage des espèces de vers de terre qui envahissent le 276

sol ainsi que de l'historique de leur utilisation (Frelich et al, 2006). 277

Finalement, la perte de la couche superficielle des sols forestiers cause des changements dans la 278

communauté mycorhizienne. Les changements dans la structure et la chimie du sol et le pâturage 279

4

par les vers de terre conduisent aux changements dans l'abondance et de la structure des 280

communautés fongiques du sol (Johnson et al 1992; McLean and Parkinson, 1998b, 2000). 281

La perte de mycorhizes peut avoir des effets négatifs sur la fonction racinaire des plantes 282

(Lawrence et al., 2002), la croissance des plantes (Gundale, 2002) et les assemblages de 283

communautés végétales (Holdsworth et al., 2007). De plus, une augmentation de la diversité des 284

vers de terre peut entraîner une diminution de la diversité des espèces végétales en raison du fait 285

que différentes espèces de vers de terre occupent plusieurs niches dans le sol. Hale et ses 286

collaborateurs, en 2005, ont constaté une diversité végétale plus faible dans les régions où l'on 287

trouve à la fois des espèces de vers épigéiques (vivant dans la couche organique supérieure du 288

sol) et endogéniques (dans des couches organiques et minérales du sol) que dans les régions où 289

l'on ne trouve que des vers endogéniques (Hopfensperger et al., 2011). Le déclin des taux des 290

champignons en abondance ou en colonisation ou des changements dans la composition de la 291

communauté fongique mycorhizienne pourrait conduire à des changements dans les 292

communautés végétales des forêts feuillus et boréales, incluant les communautés du sous-bois 293

(Frelich et al, 2006), qui sont la cible de cette étude. Bien qu'il y ait peu d’espèces végétales 294

mycorhiziennes, comme Arisaema triphyllum et Circaea lutetiana, qui ont une relation positive 295

avec la biomasse lombricienne, un beaucoup plus grand nombre d'espèces végétales est 296

négativement corrélé avec la biomasse lombricienne (Hale 2004). Donc, nous savons que les 297

structures physique, chimique et microbiolnique des sols forestiers sont changées suite à 298

l’invasion des vers de terre. Plusieurs auteurs ont affirmé que les vers de terre influencent 299

fortement la composition de la communauté végétale herbacée (Drouin et al, 2014, Frelich et al, 300

2006). Typiquement, ces études démontrent une association entre l’occurrence ou abondances 301

des vers de terre et un changement dans la structure de la communauté végétale. 302

303

Cependant, une association entre la distribution des vers de terre et la structure de la végétation 304

de sous-bois n’est pas nécessairement une relation causale puisque la corrélation entre les deux 305

peut être une réponse commune aux perturbations humaines, même pour des perturbations qui 306

datent de plusieurs décennies. Par exemple Beauséjour et al (2015) ont conclu que certaines 307

espèces étaient distribuées en tenant compte non seulement de la distribution spatiale des 308

perturbations humaines, mais aussi du délai après lequel la perturbation s’est répandue. Notre 309

5

premier chapitre nous a permis de conclure que la distribution des vers de terre et la structure des 310

communautés d’espèces de sous-bois de forêt du parc écoforestier de Johnville suivent 311

l’historique de l’utilisation de ce site. Pourtant, il existe de bonnes raisons pour supposer que 312

l’invasion des vers de terres des sols forestiers provoque un changement de la structure et la 313

composition des communautés végétales du sous-bois. 314

315

Il y a deux faiblesses importantes dans toutes ces études. D’abord, ces études se basent sur des 316

corrélations entre la présence/absence (ou abondance) des vers de terre et des changements de 317

composition des espèces végétales. Par contre, nos forêts sont bousculées simultanément par 318

plusieurs changements : l’aménagement forestier, les changements dans les populations 319

d’herbivores (surtout les cerfs de Virginie), les dépositions azotées et les changements 320

climatiques. Il est très difficile de séparer les effets des invasions des sols forestiers par les vers 321

de terre de ces autres changements en utilisant les études observationnelles. Ensuite, même si 322

nous pouvions attribuer un effet causal aux vers de terre, il est probable que cet effet sera 323

différent sur différentes espèces végétales. Certaines espèces végétales peuvent être favorisées, 324

et d’autres affectées négativement. Comment prévoir ces effets? Pour démontrer une relation 325

causale entre l’introduction des vers de terre et des changements dans la composition de la 326

communauté des plantes de sous-bois, il faudrait faire une expérience sur le terrain en 327

introduisant des vers de terre dans un sol qui n’a jamais eu des vers de terres, avec un contrôle 328

statistique approprié, et ensuite suivre les changements dans la végétation. Une telle expérience 329

n’a pas été faite et ne se fera probablement jamais à cause des contraintes d’éthique 330

environnementale. 331

332

Dans notre chapitre 2, nous proposons un compromis entre une telle expérience idéale et des 333

études purement observationnelles : une expérience dont on manipule la présence/absence des 334

vers de terres mais dans des conditions plus contrôlées qui ne mettent pas en danger les sols 335

forestiers. En plus, nous avons privilégié l’approche par analyse des traits fonctionnels en 336

choisissant des espèces végétales qui possèdent des traits fonctionnels qui peuvent accentuer ou 337

diminuer les effets négatifs hypothétiques créés par des changements environnementaux 338

provoqués par les vers de terre. L’arrivée des vers de terre dans un sol forestier cause la réduction 339

6

de la couche de feuilles mortes (litière) sur la surface du sol, la couche de la matière organique 340

décomposée des sols forestiers. Puisque plusieurs espèces de sous-bois gardent leur système 341

racinaire dans cette couche, on peut supposer que ces espèces seront négativement affectées par 342

les vers de terre. Les espèces dont les racines se trouvent dans le sol minéral ne devraient pas 343

être affectées autant. 344

345

Ensuite, nous savons que les vers de terre détruisent des hyphes fongiques, incluant des hyphes 346

mycorhiziennes (Pelosi et al, 2014) présumément en les mangeant. Si c’est bien le cas, les 347

espèces de sous-bois qui sont plus fortement mycorhizées devraient être plus affectées 348

négativement par les vers de terre. Existe-t-il des attributs morpholniques, physiolniques ou 349

phrénolniques (« traits fonctionnels ») des espèces végétales qui peuvent prédire leurs réponses 350

face aux vers de terre ? Pour approcher cette problématique, nous avons fait une expérience dans 351

des mésocosmes. Nous y avons transplanté des espèces de sous-bois ayant des trais fonctionnels 352

variés. Certaines espèces ont uniquement des racines dans la litière et d’autre dans le sol minéral. 353

Dans chacune de ces deux catégories, la moitié des espèces sont fortement mycorhizées les autres 354

faiblement. La moitié des mésocosmes a fait l’objet d’un ajout des vers des terres tandis que 355

l’autre moitié des mésocosmes a fait l’objet d’une exclusion des vers de terres. 356

357

Ainsi dans ce deuxième chapitre nous avions deux hypothèses de travail: (1) les espèces ayant 358

leurs racines uniquement dans la couche de litière seront affectées négativement par les vers de 359

terre exotiques; (2) les espèces qui sont fortement mycorhizées seront aussi affectées 360

négativement. 361

7

CHAPITRE 2 362

La structure d'une communauté végétale herbacée de sous-bois de forêt et sa relation avec 363

l'abondance des vers de terre invasifs. 364

365 366

Titre original: The structure of a herbaceous understory plant community and its relationship to 367

invasive earthworm abundance. (sera soumis à Botany) 368

369

Le présent chapitre présente les résultats issus de l’analyse des données d’un échantillonnage de 370

vers de terre et d’espèces herbacées du sous-bois de forêt réalisé sur 87 placettes dans trois zones 371

du parc écoforestier de Johnville au long de 18 transects perpendiculaires aux chemins. 372

373

On a trouvé que les vers de terre sont présents en grande quantité dans les zones Récréation et 374

Plantation tandis qu’ils sont quasiment absents dans la zone Conservation et que les espèces 375

herbacées du boisé de Johnville sont structurées en trois communautés réparties respectivement 376

sur les 3 secteurs de ce territoire. 377

378

Les résultats montrent comme plusieurs autres études qu’il y a une association entre l’abondance 379

des vers de terre et la structure de la végétation du sous-bois au parc écoforestier de Johnville. 380

Comme la répartition des abondances des vers de terre, les espèces herbacées du parc sont 381

structurées en respectant la zonalité de ce site. On est amené à penser que c’est l’historique de 382

chaque zone qui est déterminant, en contraste avec l’affirmation selon laquelle la réponse de la 383

forêt est fortement corrélée au type d’espèce de vers de terre présents. 384

8

The structure of a herbaceous understory plant community and its relationship to invasive 385

earthworm abundance 386

Claude Ndabarushimana, Bill Shipley* 387

Laboratoire d’Écologie Fonctionnelle 388

Département de biologie, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke (QC) Canada J1K 2R1 389

9 Abstract

390 391

We asked if the community structure of forest understory herbaceous species is determined by 392

earthworm abundances independently of abiotic and historical variables. To answer this question, 393

we studied the structure and community composition of understory plant species and the earthworm 394

abundance of Johnville Ecoforest Park (Quebec). Here we report results from a sampling of 395

earthworms and herbaceous forest understory species on 87 plots in three zones of the park that 396

differ in historical land use, along 18 transects perpendicular to the roads. Earthworms are present 397

in large quantities in the Recreation and Plantation zones, while they are nearly absent in the 398

Conservation zone. The herbaceous species are also structured into three communities distributed 399

respectively over the three zones of this territory and there is an association between the abundance 400

of earthworms and the structure of herbaceous understory vegetation. The statistical significance 401

of this association disappears once we take into consideration the differences between land use 402

zones. There is no link between current anthropogenic disturbances and the abundance of 403

earthworms. The observed association between the abundance of earthworms and the structure of 404

herbaceous understory vegetation is not causal but generated by the common response of each to 405

land use history. 406

407

Keywords: Invasive earthworms, forest understory plant communities. 408

10 1. Introduction

410 411

In Canada and the northern United States, it is generally accepted that most native earthworms did 412

not survive the Wisconsin glaciations. Rather, the vast majority of earthworm species now 413

occurring in Canada and the northern United States are the result of recent introductions by 414

European settlers (Reynolds 1994). In Quebec (Canada), 17 of 19 known earthworm species have 415

been introduced by European settlers (Reynolds and Reynolds 1992; Addison 2009, Drouin et al. 416

2014). Among the exotic earthworm species, the most abundant are those of the genus Lumbricus 417

(Reynolds 1977; Addison 2009). These exotic species are found mainly in agricultural land or 418

other places disturbed by humans but are also found in some forest soils in this region (Hale et al. 419

2005, Bohlen et al. 2004a, Burtelow et al. 1998). 420

421

In historically worm-free soils in North America, the invasion of European earthworms is strongly 422

linked to human activities, leading to their introduction into new areas where their establishment 423

and spread will depend on their habitat (Kalisz and Dotson 1989, Suarez et al. 2006, Tiunov et al. 424

2006, Cameron et al. 2007). This human dispersal is important because the natural dispersion of 425

earthworms is very slow, with a propagation rate ranging only up to 5 to 10 meters per year 426

depending on the region (Addison 2009, Cameron and Bayne 2009). Soils containing earthworms, 427

even today, are mainly associated with human activities (agriculture, horticulture, etc.). Their 428

relative abundance and species composition are strongly related to soil type, climate, vegetation, 429

topography, land use history and especially its history of invasions by exotic species (Hendrix and 430

Bohlen 2002). Although earthworms are increasingly found in forest environments in these areas, 431

there are still many forested areas without earthworms (Hendrix and Bohlen 2002). Forest interiors 432

are often relatively unaffected by earthworm invasion; the probability of earthworm establishment 433

and the extent of spread increases with proximity to roads and other human developments 434

(Cameron and Bayne 2009, Sackett et al. 2011; Shartelletal 2013). In forests, they are generally 435

found in high density near roads and around lakes used for fishing, suggesting that their 436

introductions have been facilitated by human activities such as transport by vehicles or simply 437

brought in to be used as fishing bait (Hendrix and Bohlen 2002). Drouin et al. (2016) confirmed 438

that the distribution and abundance of exotic earthworms observed in forests reflect human 439

11

accessibility to these environments and that their dispersal is facilitated by humans because 440

earthworms have been found in unprotected sites and crossed by trails and no worms have been 441

found on protected sites or sites remote from trails and dwellings. The authors of this study also 442

suggested that the consequences of the growing spread of earthworms in temperate forests could 443

compromise the integrity of biodiversity and the recruitment of shrub species. The authors of the 444

study found a negative correlation between earthworm abundance and the abundance of some plant 445

species. However, it is also known that the history of site use can explain the distribution and 446

dispersal rate of earthworms. Beauséjour et al. (2015) concluded that earthworm distributions are 447

determined by not only the current spatial distribution of human disturbances, but also the history 448

of such human disturbances. Some of the oldest human disturbances on their study site (Mont Saint 449

Hilaire, Quebec) that are up to one hundred and fifty years old, are now barely evident in the 450

vegetation structure, but their influence on earthworm distributions persists to this day. Therefore, 451

the history of forest sites (former agricultural and non-agricultural land) must be taken into account 452

to understand the current distribution of earthworms in these forest soils. 453

454

Earthworms are often referred to as "ecosystem engineers" because they significantly alter the 455

physical and biolnical attributes of the soil. Since different plant species are adapted differently to 456

these soil attributes, and since these North American plant communities have developed since the 457

end of the Wisconsin glaciations in the absence of earthworms, it is possible that the invasion of 458

forest soils by exotic earthworms may also alter the structure of these forested plant communities. 459

In particular, earthworms directly modify the rate of litter decomposition, the physical structure of 460

the soil and the microbial communities of the soil. The extent of loss of the organic horizon of 461

forest soil and the consequences for plant communities of native forest depends on the invasive 462

earthworm species (Hale et al. 2005). However, it is reasonable to believe that the introduction of 463

worms into ecosystems that developed without these invasive species in the aftermath of the last 464

glaciation more than 10,000 years ago will have significant impacts. The invasion of exotic 465

earthworms into temperate and boreal forests in North America, long ignored, has become a 466

growing concern in the scientific community (Hale et al. 2005; Suarez et al. 2006; Addison 2009). 467

12

The activity of earthworms is not always beneficial to plants. After invasion, earthworms modify 469

the structure of soil horizons, nutrient availability, and soil biota. The type and magnitude of these 470

impacts vary with lumbricid species and soil characteristics (Frelich et al. 2006). Earthworms are 471

key members of the soil macrofauna and they can affect the composition of primary producers and 472

ecosystem productivity by changing seedbed conditions, soil characteristics, water flow, nutrients 473

and carbon, and plant relationships. There is indirect evidence that they strongly influence the 474

composition of the herbaceous plant community. Changes in the tree seedling community 475

attributed to exotic earthworms suggest that the composition of the tree layer will eventually change 476

(Drouin et al. 2014, Frelich et al. 2006). However, an association between earthworm distribution 477

and understory vegetation structure in the field is not necessarily a causal relationship since the 478

correlation between the two can be a common response to human disturbances, even for 479

disturbances that date back several decades. However, there are good reasons to assume that the 480

invasion by earthworms of forest soils causes a change in the structure and composition of 481

understory plant communities. Consequences attributable to invasive exotic earthworms include 482

changes in forest soil structure (McLean and Parkinson 1997) and reduction or eradication of the 483

bedding layer (Edwards and Bohlen 1996). This can affect species in different ways; herbaceous 484

species in the understory vary according to their placement of the root system in the soil and species 485

whose roots are limited to the organic layer might be negatively affected while those whose roots 486

penetrate into the mineral soil might be positively affected. Furthermore, according to Wardle 487

(2002), when earthworms transform the structure of a fungus-dominated soil into a bacteria-488

dominated soil, the relationships between the roots and the plant are affected. The loss of 489

mycorrhizae can have negative effects on the root function of plants (Lawrence et al. 2003), plant 490

growth (Gundale, 2002) and plant community assemblages (Holdsworth et al. 2007). Therefore, 491

species may be affected differently depending on their mycorrhization rates. 492

In this respect, we wanted to test the hypothesis that the abundance of earthworms influences the 493

structure of forest understory plant communities independently of other abiotic and biotic factors, 494

including the history of the site. To do this, we asked two questions: 495

1) Is there a correlation between the structure and community composition of understory plant 496

species and the abundance of earthworms? 497

13

2) If so, does this correlation exist independently of abiotic and historical variables? In other words, 498

does this correlation disappear by controlling for abiotic and historical variables? 499

500

2. Materials and Methods 501

502

Presentation of the study area 503

504

The sampling campaign was conducted in the summer of 2017 at Johnville Ecoforest Park (45.345° 505

N, 71.755° W) in the Estrie region of south-central Quebec, Canada. This park covers 224 ha, 85 506

of which is a peat bog (Grégoire et al. 2010), the rest being a mixed forest located about 300 km 507

south of the boreal forest. The dominant tree species are Acer rubrum Linnaeus, Betula papyrifera 508

Marshall, Abies balsamea Linnaeus, Betula alleghaniensis Britton. The park prohibits activities 509

that could have a negative impact on wetlands and forests, such as drainage, road construction, 510

motorized traffic, among others except for some recreational and educational activities intended 511

for the general public (L. DeSerres, personal communication). This study site is located in an area 512

that receives up to 1209 mm of precipitation per year and average temperatures range from -10.2°C 513

in January to 19.0° in July (Environment Canada 2018). 514

515

Sampling 516

517

Sampling was carried out at three sectors of the park that we will call "zones": the Plantation zone 518

(P) in the northeast, the Conservation zone (C) in the southeast and the Recreation zone (R) in the 519

southwest,which shelters the Lavigne spring that has supplied water to the villages surrounding the 520

site since 1919. The "P" zone was planted before the 1900s, mainly with forest species such as 521

white pine, red pine and maple. The "R" zone is a secondary forest that has developed on former 522

agricultural fields (Figure 1). 523

14 524

525

Figure 1. 1945 aerial photo of Johnville Ecoforest Park. 526

(source: Department of Energy, Mines and Resources, Canada). Flight line: A9429, Photo no. 56, 527

Latitude: 45°20'14'', Scale: 1/20 000. The red outline determines the approximate location of the 528

park. 529

530

Zone "C", which is located around the lakes, one of which has historically provided drinking water 531

for the village of Lennoxville, does not appear to have ever experienced significant anthropogenic 532

15

pressure. Indeed, the road leading into this part of the park was built with local materials around 533

1969. 534

535

We collected our samples from 87 plots of 50 cm X 50 cm each, along 18 transects perpendicular 536

to the roads or trails of the park. On the same path, in the same sector, the transects were parallel 537

to each other and equidistant by 50 m. For a given transect, the plots were placed 1m, 6m, 16m, 538

66m, and 116m from the road or path. We used this sampling design since many studies have 539

shown that earthworm density often decreases as one moves away from a road (Cameron and Bayne 540

2009; Hale et al 2008). In each plot, herbaceous species were identified and the abundance of each 541

was estimated by counting the number of stems. The number of earthworms per plot was quantified 542

using Lawrence and Bowers' (2002) mustard solution extraction method, in which a mustard 543

solution (10g/l) is poured on the soil previously cleared of litter and vegetation after counting the 544

number of herbaceous plant individuals. This solution causes earthworms to return to the surface. 545

All individuals observed for 15 to 20 minutes after application of the mustard solution were 546

counted. Lawrence and Bowers (2002) showed that this method is as effective as other methods 547

while being much faster. Since we could not identify juvenile individuals to species, we worked 548

only with the total abundance of earthworms. Environmental data were collected on the following 549

variables: (1) the thickness of the litter layer (in cm) was measured using a ruler; (2) soil drainage 550

was estimated from the absorption rate of the mustard solution by the soil and classified into three 551

categories. After pouring 5 liters of mustard solution onto the quadrat, drainage was deemed rapid 552

if it disappears within 5 min, moderate for 5-10 min and slow for 10 and more; (3) soil texture was 553

classified into the four categories (sand, silt, clay and organic matter) assessed taking into account 554

the most dominant constituent element. These elements have been classified according to a rapid 555

test as described by Saucier (1994, pp. 32-35); (4) Percent canopy cover was estimated using a 556

digital photo taken by a camera equipped with a hemispherical lens and the free LGA (Gap Light 557

Analyzer) software from the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies (www.caryinstitute.org). The 558

DBH (diameter at breast height) was measured with a tape on tree stems larger than 2cm to deduce 559

basal area. The DBH was been estimated in a circle of 2m radius with the center of the plot. 560

16 3. Statistical analyses

562 563

All statistical analyses were performed with R software (version 3.4.3). The relationship between 564

earthworm density and environmental conditions was determined using generalized mixed linear 565

models using the lmer function (lme4 library) with transect as a random variable and using the 566

quasi-Poisson distribution in our model to manage cases of overdispersion (Crawley 2012). We 567

tested the statistical significance of the relationships in these generalized linear models between 568

earthworm abundance and environmental variables such as distance from plots to roads, zone 569

(zoning in park sectors), percent canopy, basal area, bedding thickness, soil drainage, number of 570

stems and soil texture with ANOVAs by using the chi-square distribution and comparing nested 571

models (with/without the explanatory variable). 572

The relationships between the structure of understory vegetation and environmental variables were 573

determined using redundancy analysis (Legendre and Legendre 2012) using the vegan package 574

(version 2.4.6). We constructed a matrix of the relative abundances of each herbaceous species 575

(response variable) found in each quadrat. To do this, we used a Hellinger transformation from 576

abundances per plot to relative abundances (Legendre and Gallagher 2001). A Hellinger 577

transformation is available in the vegan library of R under the decostand function (). This 578

transformation is appropriate for our species abundance data because the proportion of zeros in the 579

matrix is high (92%), and this avoids double zeros being considered in the calculation of similarity 580

between plots (Legendre and Gallagher 2001). This produces a matrix (V) that describes the 581

relative abundance of each plant species in each quadrat. Next, we constructed a matrix of 582

explanatory variables (E). This matrix describes the values of each environmental variable, 583

including the zone in which the plot is found, plus the abundance of earthworms found in each 584

quadrat. Having different units, the environmental variables in matrix E were standardized before 585

calculating the distance measurements used to perform the ordination analyses (Borcard et al. 586

2011). Some variables were ln-transformed before analysis as ln(x) or ln(x+1) on a case-by-case 587

basis to ensure that their residuals were distributed according to a normal distribution. The 588

abundance of earthworms was also included in matrix E; these abundances were transformed into 589

ln(x+1), where x is the number of individuals recorded. We related the vegetation (V) and 590

environmental E matrices using redundancy analysis (RDA) via the RDA function of the vegan 591

17

library. Null probabilities, associated with these models, were determined by permutation tests, 592

using 1000 permutations. The analysis was done in three steps: 593

Step 1: We tested the null hypothesis that there is no association between earthworm abundance 594

and vegetation structure, without reference to other environmental variables, using an RDA that 595

relates the matrix V to only the transformed abundance of earthworms. The rejection of this null 596

hypothesis demonstrates that there is an association between the abundance of earthworms and the 597

structure of vegetation. 598

Step 2: An RDA was then performed using all environmental variables without the abundance of 599

earthworms. We retained the significant explanatory variables by progressive selection using the 600

vegan ordiR2step function. A significant relationship shows that there is an association between 601

some of these environmental variables and vegetation structure. 602

Step 3: Then the RDA was redone using the environmental variables selected in Step 2 plus the 603

transformed abundances of earthworms. If the structure and composition of vegetation is affected 604

by earthworm abundance independently, or in addition to other environmental variables, then this 605

variable will have a significant association in the model. If, on the other hand, the association 606

between the structure and composition of vegetation and earthworms is caused only by a common 607

response to other environmental variables, then the abundance of earthworms will lose its 608

significance in this model. 609 610 4. Results 611 612 Earthworm community 613 614

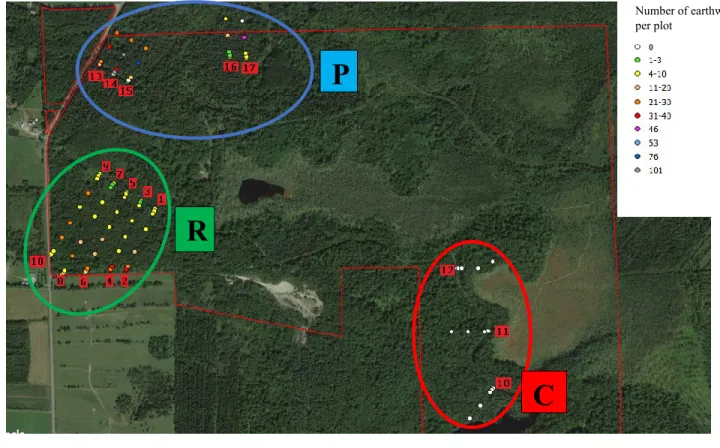

A model linking the abundance of earthworms according to the three zones shows that the 615

abundance of earthworms differs from one zone to another (p<0.001). Earthworms are present in 616

large quantities in the Recreation and Plantation zones while they are almost absent in the 617

Conservation zone. We observed only one earthworm in the Conservation zone while we observed 618

637 and 583 earthworms in the Recreation and Plantation Zones, respectively (Figure 2). 619

18 620

Figure 2. Sampling plan and illustration of earthworm abundances per plot. 621

Google aerial image/ unknown year (Municipalité régionale de comté du Haut St-François), P = 622

Plantation, R = Recreation, C = Conservation, the numbers 1 to 18 represent the number of each 623

transect. 624

Contrary to our hypotheses, earthworms, in the two zones (R and P) where they are abundant, are 625

not distributed according to any environmental variable. Their abundance is not significantly 626

correlated to any of the response variables (bedding thickness, soil texture, drainage, moisture, 627

DBH, canopy opening, basal area), including distance from a source of human disturbance, whether 628

a road or a walking trail. 629

630

Influence of earthworm abundance on the structure of forest understory plant communities 631

632

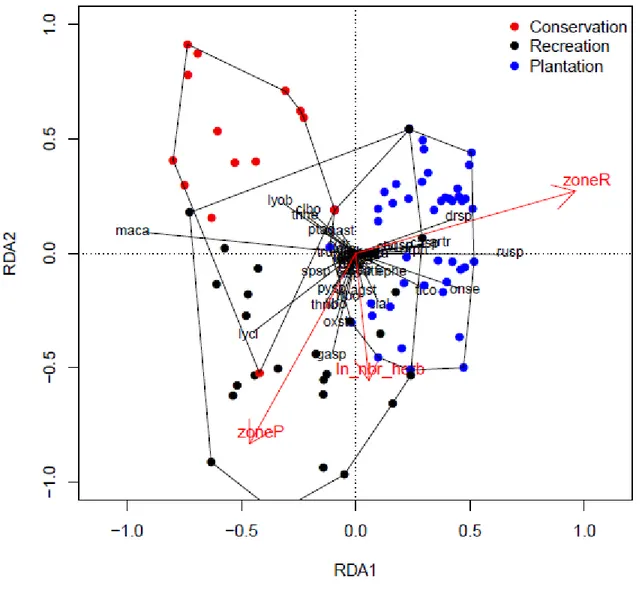

A redundancy analysis (RDA) of the structure (V) of the herbaceous community as a function of 633

earthworm abundance shows that the two are significantly associated (F1,85 = 3.1352, p = 0.001).

634

However, in the stepwise selection of variables, the only environmental variables selected that had 635

P

R

C

Number of earthworms per plot19

a significant association with the structure of the understory herbaceous communities were the zone 636

in which the plot was found. In particular, the redundancy analysis of the structure (V) of the 637

herbaceous community according to zone (Z) shows that the latter has a significant response (F1,85

638

= 4.6439, p = 0.001). Thus, the vegetation structure of the understory is associated with both the 639

zone and the abundance of earthworms. On the other hand, there is also a strong association 640

between the zone and the abundance of earthworms. A third redundancy analysis (RDA) of the 641

structure (V) of the herbaceous community as a function both of the abundance of earthworms and 642

the zone together shows that earthworms do not have a significant response (F1,84 = 0.9439, p =

643

0.5246) by controlling for the zone but the zone remains significant (F1,84 = 2.3979, p = 0.0013)

644

when controlling for earthworm abundance. Figure 3 summarizes the RDA and shows that the 645

herbaceous species of the Johnville woodland are structured into 3 communities spread over the 3 646

sectors of this territory. 647

20 648

Figure 3. Ordination of understory plant community from Johnville ecoforest park. 649

The output of an RDA shows 3 distinct zones (Conservation zone in red, Recreation zone (R) in 650

black and Plantation zone (P) in blue. The meaning of the plant species codes is given in the 651 appendix. 652 653 5. Discussion 654 655

In our study, as in several other studies (for example, Frelich et al. 2006; Drouin et al, 2016), there 656

is an association between the abundance of earthworms and the structure of understory vegetation. 657

Contrary to our expectations, we did not detect an association between current anthropogenic 658

21

disturbances (distance from roads and trails) and the abundance of earthworms. However, there is 659

a very clear association between the historical use of the site and the abundance of earthworms. At 660

Johnville Park, the three sectors (zones) have experienced different human activities in the past. 661

The Plantation zone is currently occupied by conifers originally planted on an old farm. The 662

Recreation zone, dominated by yellow birch, is a younger secondary forest that has also developed 663

on former agricultural land. These two zones have experienced agricultural activities in the past 664

and anthropogenic pressure has been further encouraged by the alignment of access roads for water 665

intake work from the site's source to supply water to surrounding villages, including the current 666

town of Lennoxville. This activity dates back to 1919 (History of the Johnville Woodlands, 2002), 667

i.e. nearly 100 years ago, before which there were agricultural activities. Agricultural activities are 668

pointed out because they have a great potential to be associated with the spread of earthworms, 669

which could partly explain the presence and high density of earthworms in these zones. The 670

Conservation zone remained isolated until 1979 when a road was built to access it. This may partly 671

explain the very low density of earthworms (1 worm sampled throughout the area) compared to the 672

other two zones. It is also important to note that the only earthworm in this zone was sampled close 673

to the road, at 1 meter. This indicates that this zone remains well preserved and that the introduction 674

of worms into this part of the park is probably recent. 675

676

There is an additional reason that could explain this uneven distribution of earthworm densities at 677

the study site. According to information gathered from current park managers, roads and hiking 678

trails in the Recreation and Plantation sectors have been developed with materials collected 679

elsewhere, potentially containing earthworms, while for roads in the Conservation Zone, the 680

materials used have been dug on site in the zone itself. The Conservation Zone has been lnged in 681

the past but does not have an agricultural past. Since the natural dispersion of earthworms is very 682

slow, at most 10 meters per year (Addison 2009), the most likely explanation is that earthworms 683

were introduced into the Recreation and Plantation zones by agricultural activities prior to 1919, 684

the year the site was acquired by the Town of Lennoxville, and that earthworms have not yet 685

invaded the Conservation Zone. 686

22

Although the current distribution of earthworms and understory vegetation structure appears to 688

follow the history of the site, does this necessarily mean that earthworms do not have an effect on 689

vegetation structure? Indeed, there is a considerable spatial variation in the abundance of 690

earthworms within the Recreation and Plantation sites, ranging from 0 to 404 individuals per m2

691

(101 worms being the largest count on a 0.25 m2 plot). On the other hand, by including the zone

692

and abundance of earthworms in the RDA, the abundance of earthworms lost its statistical 693

significance, but the zone continued to be significant. This suggests that the association between 694

earthworm abundance and vegetation structure was due to the fact that both respond simultaneously 695

to differences in historical use of the site (zoning). Within each zone, the variation in earthworm 696

abundance is not correlated with differences in understory vegetation structure. Like the 697

distribution of earthworm abundances, the herbaceous species in this park are structured according 698

to the land use history of the park, contrary to our working hypothesis that this structure would be 699

determined by the abundances of earthworms. Here too, we are led to believe that it is the past of 700

each zone that is decisive in the assertion that the forest response is strongly correlated to the type 701

of earthworm species in place (Bohlen et al. 2004). Our results and conclusions are based on 702

observational data. There is a need for experimental studies to try to approach the impact of exotic 703

earthworms on forest understory species. 704

23 6. Acknowledgements

705 706

We thank David R. Sanchez for his participation in the sampling campaign, and Mathieu Dufresne 707

of the Johnville Park for his help. This research was supported by an NSERC Individual Discovery 708

Grant to BS. 709

710 711

24 7. References

712 713

Addison, J.A. 2009. Distribution and impacts of invasive earthworms in Canadian forests 714

ecosystems. Biol. Invest. 11, 59–79. 715

Beauséjour, R., Handa, I. T., Lechowicz, M. J., Gilbert, B., & Vellend, M. 2015. Historical 716

anthropogenic disturbances influence patterns of non-native earthworm and plant invasions 717

in a temperate primary forest. Biolnical Invasions, 17(4), 1267-1281. 718

Bohlen, P.J., Pelletier. D., Groffman, P.M., Fahey, T.J., Fisk, M.C. 2004a. Ecosystem 719

consequences of exotic earthworm invasion of north temperate forests. Ecosystems 7:1–12. 720

Bohlen, P.M. Groffman, T.J. Fahey, M. Fisk, E. Suarez, D.M. Pelletier and R.T. Fahey. 2004C. 721

Ecosystem consequences of exotic earthworms invasion of north temperate forests. 722

Ecosystems, 7: 1-12. 723

Borcard, Gillet & Legendre. 2011. Numerical Ecolny with R. Springer New York. 724

Cameron, E.K., Bayne, E.M. 2009. Road age and its importance in earthworm invasion of 725

northern boreal forests. J Appl Ecol 46:28–36. 726

Cameron, E.K., Bayne, E.M, Clapperton, M.J. 2007. Human-facilitated invasion of exotic 727

earthworms into northern boreal forests. Ecoscience 14:482–490. 728

Crawley, M.J. 2012. The R book. John Wiley and Sons. 729

Drouin, M., Bradley, R., Lapointe, L., 2016. Linkage between exotic earthworms, understory 730

vegetation and soil properties in sugar maple forests. Forest Ecolny and Management. 364, 731

113-121, Mar. 15, 2016. ISSN: 0378-1127. 732

Drouin, M., Bradley, R., Lapointe, L., Whalen, J. 2014. Non-native anecic earthworms 733

(Lumbricus terrestris L.) reduce seed germination and seedling survival of temperate and 734

boreal trees species. Applied Soil Ecolny, ISSN: 0929-1393, Vol: 75, Page: 145-149. 735

Edwards, C.A., Bohlen PJ. 1996. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. In: Edwards, C.A., Bohlen PJ, eds. 736

Biolny and ecolny of earthworms. London, UK: Chapman & Hall, 64–80. 737

25

Environnement Canada. 2018. 1981 to 2010 Canadian Climate Normals station data. 738

«http://climate.weather.gc.ca/climate_normals/» (Accessed 09 April 2018). 739

Frelich, L.E., Hale, C.M., Scheu S, Holdsworth, A.R., Heneghan, L., Bohlen, P.J., Reich, P.B. 740

2006. Earthworm invasion into previously earthworm-free temperate and boreal forests. 741

Biol Invasions 8:1235–1245. 742

Grégoire Taillefer, A., & Wheeler, T. 2010, Effect of Drainage Ditches on Brachycera (Diptera) 743

Diversity in a Southern Quebec Peatland, The Canadian Entomolnist, 2, p. 160, BioOne 744

Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 9 April 2018. 745

Gundale, J. M. 2002. Influence of exotic earthworms on the soil organic horizon and the rare fern 746

Botrychium mormo. Conserv. Biol., 16:1555–1561. 747

Hale, C.M., Frelich L.E., Reich ,P.B. 2005. Exotic European earthworm invasion dynamics in 748

northern hardwood forests of Minnesota, USA Ecol Appl. 15(3):848–860. 749

Hale, C. M., Frelich L, Reich P., Pastor J. 2008. Exotic earthworm effects on hardwood forest 750

floor, nutrient availability and native plants: a mesocosm study. – Oecolnia 155: 509–518. 751

Hendrix, P., Bohlen, P. 2018. Exotic Earthworm Invasions in North America: Ecolnical and 752

Policy Implications. Bioscience [serial online]. September 2002;52(9):801. Available from: 753

Academic Search Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed August 1. 754

Holdsworth, A. R., L. E. Frelich and Reich, P. B. 2007. Effects of earthworm invasion on plant 755

species richness in northern hardwood forests. Conserv. Biol., 21:997–1008. 756

Kalisz, P.J., Dotson, D.B. 1989. Land-use history and the occurrence of exotic earthworms in the 757

mountains of eastern Kentucky. Am Midl Nat 122:288–297 758

Lawrence, A. P., & Bowers, M. A. 2002. Short communication: A test of the ‘hot’ mustard 759

extraction method of sampling earthworms. Soil Biolny And Biochemistry, 34: 549-552. 760

doi:10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00211-5. 761

Legendre, P., Gallagher, E.D., 2001. Ecolnically meaningful transformations for ordination of 762

species data. Oecolnia 129, 271-280. 763

26

Legendre, P., Legendre, L., 2012. Numerical Ecolny, third ed. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The 764

Netherlands. 765

Reynolds, J.W. 1977. The Earthworms (Lumbricidae and Sparganophilidae) of Ontario. Toronto 766

(ON): Royal Ontario Museum Miscellaneous Publication. 767

Reynolds, J.W., 1994. The distribution of the earthworms (Oligochaeta) of Indiana: a case for the 768

post quaternary introduction theory for megadrile migration in North America. 769

Megadrilnica 5:28–32 770

Sackett T.E., Smith SM, Basiliko, N. 2012. Exotic earthworm distribution in a mixed-use 771

northern temperate forest region: influence of disturbance type, development age, and soils. 772

Can J Forest Res 42:375–381. 773

Saucier, J.P., 1994. Le point d’observation écolnique : normes techniques : [Charlesbourg] : 774

Gouvernement du Québec, Ministère des ressources naturelles, 1994. 775

Shartell, L.M., Lilleskov, E.A., Storer, A.J. 2013. Predicting exotic earthworm distribution in the 776

northern Great Lakes region. Biol Invasions 15:1665–1675. 777

Suarez, E.R., Tierney, G.L., Fahey TJ, Fahey, R. 2006 Exploring patterns of exotic earthworm 778

distribution in a temperate hardwood forest in south-central New York, USA. Landsc Ecol 779

21:297–306. 780

Tiunov, A.V., Hale, C.M. Holdsworth, A.R., Vsevolodova-Perel, T.S. 2006. Invasion patterns of 781

Lumbricidae into the previously earthworm-free zones of northeastern Europe and the 782

western Great Lakes region of North America. Biol Invasions 8:1223–1234. 783

Wardle, D., 2002. Communities and ecosystems: linking the aboveground and belowground 784

components. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. 785

27 CHAPITRE 3 786

Effet des vers de terre exotiques sur les plantes de sous-bois de forêt. 787

788 789

Titre original: Effect of exotic earthworms on forest understory plants (sera soumis à Botany) 790

791

Le présent chapitre présente une étude expérimentale qui a été réalisée en mettant en place un 792

dispositif expérimental fait de 96 mésocosmes dans lesquels nous avons transplanté 12 espèces 793

herbacées représentatives d’une communauté de sous-bois afin de mesurer l’effet d’un ver de 794

terre introduit sur ces dernières. 795

796

Les résultats de cette étude montrent qu’après deux saisons de croissance, seule l’espèce 797

Phegopteris connectilis a répondu de façon significative à l’effet des vers de terre et sa 798

biomasse a augmenté en présence de ceux-ci. 799

800

De cette étude, on a conclu que si l’effet des vers de terre L. terrestris sur les sols dans nos 801

mésocosmes est semblable aux effets observables sur les sols agricoles, il est possible que 802

l’effet positif de cette espèce soit dû à l’augmentation de fertilité causée par l’augmentation de 803

décomposition de la matière organique du sol. Si c'est bien le cas, nous ne pouvons pas 804

expliquer pourquoi les autres espèces n’ont pas répondu de la même façon. 805

806 807

28

Effect of exotic earthworms on forest understory plants 808

Claude Ndabarushimana, Bill Shipley* 809

Laboratoire d’Écologie Fonctionnelle 810

Département de biologie, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke (QC) Canada J1K 2R1 811

812

Abstract 813

814

It has been hypothesized that forests in Canada and the northern United States are experiencing 815

changes in communities of herbaceous forest understory species following an invasion of exotic 816

earthworms. These earthworms were introduced during colonial times into these forests that 817

have existed in the absence of earthworms since the end of the Wisconsin glaciation over 10,000 818

years ago. In this study we experimentally test if the addition of Lumbricus terrestris changes 819

the probability of survival and growth of understory plants and, if so, the mechanisms by which 820

these invasive worms affect the herbaceous plants in these forests. To understand these 821

mechanisms, we chose plant species that have functional traits that can enhance or reduce the 822

hypothetical negative effects created by two environmental changes caused by earthworms. 823

Thus we set up an experimental system made of 96 mesocosms in which we transplanted 12 824

herbaceous species representative of a community of forest understory selected according to 825

their abundance to ensure that we had enough individuals. The species were chosen according 826

to two traits: (i) the rooting position of the plants (2 levels, either in organic matter or in mineral 827

soil) and (ii) the rate of root mycorrhization (2 levels, strongly mycorrhized or weakly 828

mycorrhized). After two growing seasons, only Phegopteris connectilis responded significantly 829

to the effect of earthworms and its biomass increased in their presence. If the effect of 830

earthworms on soils in our mesocosms is similar to the effects on agricultural soils, it is possible 831

that the positive effect of this species is due to increased fertility caused by the increased 832

decomposition of soil organic matter. 833

Keywords: Earthworms, forest understory plant communities 834

29 835

30 836 1. Introduction 837 838 839

Human impacts on global ecosystems are now so pervasive that many speak of the 840

Anthropocene era (Sprankling, 2017). One of these impacts is the introduction of exotic species. 841

When the abundance of introduced species becomes significant, and when the impact of these 842

introduced species on these ecosystems becomes major, we speak of invasive alien species. The 843

majority of earthworm species in northern North America are among these invasive alien 844

species. The Wisconsin glaciation decimated almost all of the native earthworms in Canada and 845

the northern United States. The forests of this part of the American continent have evolved in 846

the absence of these worms (Portes 1977, James 1998). Soils containing earthworms in this 847

region, even today, are mainly associated with human activities (agriculture, horticulture, etc.) 848

and their relative abundance and specific composition are strongly linked to soil type, climate, 849

vegetation, topography, land use history and especially its history of exotic species evasions 850

(Hendrix and Bohlen, 2002). Although earthworms are increasingly found in forest 851

environments, there are still several forest areas without earthworms (Hedrix and Bohelen, 852

2002). This is particularly the case for areas that were not subject to human influence after the 853

glaciation. This is because, in the absence of human introductions, their propagation is only 854

about 5-10 meters per year depending on the region (Addison 2009, Cameron et Bayne 2009). 855

856

Earthworms are often referred to as "ecosystem engineers" because they significantly alter the 857

structure of the soil. In particular, they directly modify decomposition rates, the physical 858

structure of the soil and the microbial communities of the soil. Therefore, it is reasonable to 859

believe that the introduction of these species into ecosystems that have developed without these 860

species for more than 10 000 years will have significant impacts. One of the first consequences 861

of introducing earthworms into a forest ecosystem is the reduction of the dead leaf layer (litter). 862

Exotic earthworm invasions have been associated with decreased forest soil thickness and the 863