To link to this article: DOI:10.1016/j.eurtel.2014.04.001

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurtel.2014.04.001

This is an author-deposited version published in:

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID: 11813

To cite this version:

Kamsu Foguem, Bernard An ontological view in telemedicine. (2014)

European Research in Telemedicine / La Recherche Européenne en

Télémédecine, vol. 3. pp. 67-76. ISSN 2212-764X

O

pen

A

rchive

T

oulouse

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and

makes it freely available over the web where possible.

Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator:

staff-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

An

ontological

view

in

telemedicine

Une

vue

ontologique

en

télémédecine

B.

Kamsu-Foguem

LaboratoryofProductionEngineering(LGP),EA1905,ENIT-INPTUniversityofToulouse, 47,avenued’Azereix,BP1629,65016Tarbescedex,France

KEYWORDS Telemedicine; Formalsemantic; Verificationand validation; Informationsystem; Ethicalissues

Summary The verification and validation of information system models impact on the

adequacy andappropriateness ofusing the value oftelemedicine services for continuously optimizinghealthcare outcomes.We havedefinedamethodology tohelpthemodeling and rigorousanalysisoftherequirementsofinformationsystems intelemedicine. Ononehand, thismethodologywillbebasedonaformalrepresentationofrequirements(systemic,generic domain, etc.)withinaknowledgebasethatwillbearequirementsrepository.On theother hand,thismethodologywilluseconceptualgraphsfortheformalizationofontologyof activi-tiesandtheproductionofargumentsrelatedtotheformalverificationofmodelsbuiltfromthis ontology.Wedescribeanexampleillustratingtheengagementofconceptualgraphprocedures tomodelthecontextualsituationsinthetelemedicinedevelopment.Wealsodiscusstheway inwhichethicalissueswillactuallytakeplaceintelemedicineapplications.

MOTSCLÉS Télémédecine; Sémantique formelle; Vérificationet validation; Systèmes d’information; Questionséthiques

Résumé Lavérification etla validationdemodèlesdesystèmesd’informationinfluentsur

la pertinenceet lajustesse del’utilisationde la valeurdes services detélémédecinepour optimiser enpermanence les résultatsdes soins. Nous avonsdéfini uneméthodologiepour aiderlamodélisationetl’analyserigoureusedesbesoinsdessystèmesd’informationpourla télémédecine.D’unepart,cetteméthodologieserabaséesurunereprésentationformelledes exigences(systémique,domainegénérique,etc.)auseind’unebasedeconnaissances struc-turantleréférentieldesexigences.D’autrepart,cetteméthodeutilisedesgraphesconceptuels pourlaformalisationdel’ontologiedesactivitésetlaproductiondesargumentsliésàla vérifi-cationformelledesmodèlesconstruitsàpartirdecetteontologie.Nousdécrivonsunexemple illustrantl’engagementdesprocéduresdegraphesconceptuelspourmodéliserlessituations

contextuellesdansledéveloppementdelatélémédecine.Nousdiscutonsaussidelamanière aveclaquellelesquestionséthiquespourronteffectivementprendreplacedanslesapplications detélémédecine.

Introduction

Usually, the quality of a system is judged primarily on the satisfaction of the services provided and assigned by users,especiallyintermsoffunctionality,stability,integrity, dependabilityandperformanceobjectives.Theseusersare healthcaremanagers,decision makers,physiciansandthe engineersthatareresponsibleforthedevelopment,piloting ormaintainingthissystem.Theirgoalsarevariedand some-timesconflicting,accordingtotheirviewsandperspectives offeredbytheenvironmentinwhichtheyoperate.

Thus,theprocessofbuildingacomplexsystemmusttake intoaccountalltheseexpectationsandcheckthat, through-outtheconstructionproject,theyarewellrespected.The modelingprocessesaresubjectedtoregularinspectionsfor thepurposeofmonitoringandverifyingcompliancewiththe specificationsandconstrains.

For this, System Engineering seems to offera way to, onthe one hand, comprehend the requirements of ‘‘real world’’andtoprovideacommonandconsistent understand-ingamongallactorsand,ontheotherhand,toensurethe adequacyofthefuturesystemwithasetofspecific objec-tives[1].Tocreateasystem,thisengineeringimplementsa seriesofactivitiesinwhichanoverviewofmethods, mod-elinglanguagesandtoolscanbeusedtocovereveryphase ofthelifecycleofthesystem.

Particularly,theSEIPS(SystemsEngineeringInitiativefor PatientSafety)modelofworksystemandpatientsafetyisa valuablesystemsapproachtohealthcarequalityandpatient safety[2].

The engineering must also take into account that the requirements of the variousstakeholders of telemedicine are evolving: additional functional requirements, specific behavioralrequirements,requirementsofindependenceto hazards,etc.Thescientificcommunityhasabodyofworkto modelandunderstandhowtelemedicineactivitiesare work-ing.However,ineachphaseofthelifecycle,thedeveloped modelsaresometimesinadequateortaintedwitherrorsthat havenegativeeffectsonthefollowingphases.Forexample, usingthewrongmodelofthesystemcontrol/commandcan causemachinedowntime.

Theneedtoensurethesatisfactionoftherequirements expressed (qualities of activities and services, control of costsandtime,etc.)isessential;thereforethismakesmore senseinahealthcareenvironment,andleadsustopaymore attentiononverificationandvalidationissues.

Verification

and

validation

Theactivitiesofverificationandvalidationaimtogive confi-dencetoallpartiesinvolved inensuringthat systemsand

activities comply withrequirements and meet the design featuresexpected.Theymustbeabletohighlightthe short-comingsofthesystemanddecideifitcanbeturnedonor not.

Theverificationis:

‘‘The confirmation by examination and by providing objective evidence (information which can be proved true, based on facts obtained through observation, measurement, test or other means) that specified requirementshave been satisfied’’ (ISO8402). Verifica-tionshouldallowtoanswerthequestion:arewebuilding themodelcorrectly?

This check is usually done through expertise, or sim-ulations based on the use by specialists in the field of mathematical demonstration tools such as ‘‘theorem prover’’and‘‘modelchecker’’.Wemustcopewith increas-ingcomplexity:healthcaremodelsareprogressivelydifficult toverifybyconventionalsimulationtechniquesand exper-tisethatoftenreachtheirlimits.

Itisthereforenecessarytoconsideralternative(or addi-tional)formalapproachestoprovideevidenceofspecified requirementsortodetectinconsistenciesforeffective ver-ification of such models. Moreover, to ensure that the developedsystemmeetstheuser,formalverificationshould becompletedbythevalidationbecause,firstly,theformal requirements donot necessarily cover all the needs, and secondly, it is not impossible to have misinterpreted the requirementsinboththerequirementsandthesystem.

Thevalidationis:

‘‘Theconfirmationbyexaminationandbyproviding tan-gible evidence (investigations in practical situations) thattheparticularrequirementsforaspecificplanned purposehavebeensatisfied.Severalvalidationscanbe made ifthereare differentintended uses’’ (ISO8402). Thevalidationshouldanswerthequestion:arewe build-ingtherightmodel?

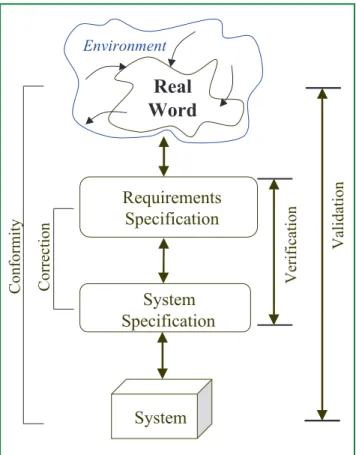

Generally, the validation that often includes the audit mayinvolvethedevelopmentcycleitself,orfocusona sin-gle phase,ensuring that the resulting model corresponds to what is expected of him. As shown in Fig. 1 (adapted from[3]), validationistoensure thatall functionsof the developedsystemmeettheneedsfromtherealworld.

Theensuingchallengeis:

Howtohelpthemodelertocarefullyobservethesetwo activities,toapplyinthecaseofacomplexengineering

Real

Word

Requirements

Specification

System

Specification

System

Validation

Verification

Conformity

Correction

Environment

Figure1. Thesubstanceoftheverificationand validation pro-cesses.

Lasubstancedesprocessusdevérificationetdevalidation.

system,andfinallytheuseoftoolsandmechanisms guar-anteeingasufficientqualityoftheanalysisresults?

Verification

/

validation

criteria

To ensure the smooth running of the engineering process definedabove,severalcriteriaofverificationandvalidation canusuallybechosen(Figs.1—2).

Firstly to facilitate the understanding of our criteria, somefundamentaldefinitionsmaybeuseful[4]:

• domainrequirements=setofaxiomaticknowledgeinthe applicationdomainthatare(oraresupposedtobe)always true,regardlessoftheexistenceoftherequiredsystem. Themodelermustthen useandtakeintoaccountthese requirementsduringtheanalysisphase;

• expressedneeds=setofstatementsonthescopeyouwant toseerespectedbythefuturesystem;

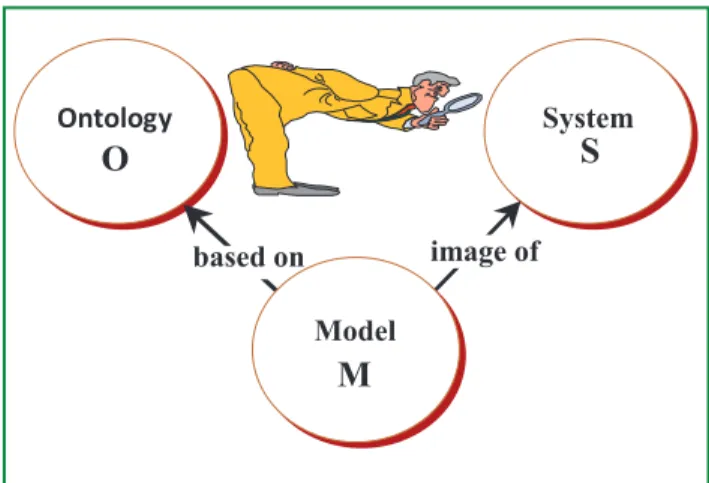

Figure2. Formalizationparadigminsystemsengineering.

Leparadigmedeformalisationdansledomainedel’ingénieriede systèmes.

• specifications=setofstatementsdescribingthebehaviors andfunctionsthatthesystemmusthaveinordertomeet theneedsexpressed.

Havingmadetheseobservations,SteveEasterbrookand John Callahan gave a formulation of the formalization paradigm in requirements engineering [5] according to whichweadjusttheinterpretationtosystemengineering. This meansthat theprinciple of theverification and vali-dationprocessescanbeformulatedinsystemsengineering bythefollowingequation:

DomainRequirements∧ Specifications ⇒ ExpressedNeeds?(1) In other words, it is to find the specifications associ-atedwiththerequirementsofthemodelingdomain.They wouldmeettheneedsexpressedbythevariousstakeholders (employees,customers,management)withpotentialusers ofthesystem.

Thisissueisdividedintotwoaspectsandrequiresthree verificationcriteriaandtwovalidationcriteria[6—11].

Verificationcriteria:

• expressedneedstobeconsistentandrealisticinrelation totherequirementsofthedomain;

• the specification model must take into account the requirementsoftheareaconcerned,andconformtothe needsexpressed;

• thefunctionalityofthesystemmustconformtothemodel specification.

Validationcriteria:

• theresultingsystemmusthavetheappropriatestructure and perform the functions and behaviors satisfyingthe needsexpressedcorrectly;

• the system must meet the requirement of ‘‘completeness’’ that is to say taking into account all the important needs of all stakeholders and the relevant requirements of the area in relation to the objectivesofthemodeler.

InpracticetheapproachshowninFigs.1and2,hasoften failedforseveralreasons:

• theneedsarepoorlyexpressedduetoinsufficient commu-nication between actors, a lack of analysis, or the ignorance of the changing situation. A new dialogue between actors, a new modeling and formal validation canovercometheseshortcomings;

• the specification is wrong due to misunderstanding of requirements, poor choice of language specification, ambiguityorincompletenessofthespecification.Thiscan beremediedbyaformalauditorbyrecursivetests; • thedomainrequirementsarequestionable,becausethere

is a lack ofexpertise andthorough investigation ofthe areawasrough.Also,takingintoaccountspecialized doc-umentsandexpertadviceisneeded.

The

need

for

a

formal

modeling

language

Thenotion ofprocessisstronglyanchoredinthe method-ologicalthinkingin variousfieldsin whichprocess models nowappearnecessaryforinformationsystemsandservices bestservetheirpurposesofmanagement.

Succinctly,wereviewthemodelinglanguagesofbusiness processes,andwefoundthatmostofthemhaveagrammar

defining the possible combinations of symbols associated with the various concepts handled and provide guidance for the inclusion of various views of a system. However, duetotheirinformalsemantics,theyofferonlythe imple-mentationofalimitednumberofargumentsandtherefore a fragmentary vision of the audit. Given a sample of ini-tial data, we can experimentally test whether a method usingthelanguage leadstocorrectresults, butthat does notexcludeothererroneousresults.Itisalwaysapositive contributionevenifitisinsufficient,becausethe construc-tionofnon-trivialsystemscansometimesleadtoambiguous models (useless and binding details, errors, inaccuracies, andincompleteness)andcausedifficultiesduringanalysis.

Therefore toovercomethis limited expressiveness and the limited opportunities for verification and to reassure the user about the qualityof the model (coherency, con-sistency,completeness,etc.)theuseofaformallanguage isessentialtous.Indeed,aformallanguageintroducessome mathematicalrigortoaccuratelydescribetheobjectsthat aremanipulatedandbettercontroltheverificationprocess. ‘‘Itishardtoimaginehowaleading-edgedesign com-panycouldremaincompetitivetodaywithoutadopting aformalverificationstrategy.’’

ScottSchroeder.Directoroftheverification,Cray ResearchInc.

Suchaformallanguageenablesusto[12]:

• formalizethespecificationsinordertoobtainaclearbasis tochecktheircompliancewiththeneedsexpressed.In addition, we can have an explicit model of the system behavioreasilycomparableneeds;

• formalize the domain knowledge to be able to reason aboutitscompletenessanddeduceconsequencesforthe system.Similarly, thisformalizationwillhelpusbe spe-cificandexplicitabouttheenvironment;

• formalizetheexpressedneedstohavetheopportunityto testtheirconsistencyandcompletenesscheck;

• toensuregoodauditcoveragebyofferingthepossibility ofestablishingtheaccuracyofreasoningmeanstoensure thatmethodologyprovidesaccurateresultsforanyinitial data.

Formal

specification

languages

Characteristics

of

approaches

Aspecificationlanguageiscalledformalifandonlyifitis alanguagewithadequatemathematicalsemantics exclud-ing(i) interpretation of rules that guaranteethe absence of ambiguity in the descriptions produced and (ii) rules deductionthat canreasonabout thespecifications to dis-coverpotentialincompleteness,inconsistenciesorevidence requirements[13].

The first constraintallows thespecification of a single reading.Thesecond constraintismoredifficult toobtain, but it is thanks to it that we can expect, state and ver-ifybehavioral orfunctionalrequirements. Inaddition,the operationalizationofthemodelsispartlyautomated, pro-totypingisfacilitated.

Formallanguagesoftendifferincertaincharacteristics:

• theontologythatcanbefixed(states,events,actions,as isthecasewithStatecharts)orextensible(meta-language definingnewconcepts);

• the mathematical basis can be expressed using logic appliedtofirstorderpredicatesor temporallogic. This foundationisalsooftenbasedonalgebraiclanguagesor settheory;

• the processingof time maybe accomplished througha statemodelorevents.Timeissometimessymbolizedby objectclasses.

Thuswedistinguishthreemajortraditionsofformal mod-eling:approachessuchasthetransitionsystem(basedonthe conceptsofstateandtransition),theset-orientedcoherent descriptionofthesystemmodelconsideredapproachesand finallyconceptualapproaches.

However,itisnotpossibletoclassifyalllanguagesbased on these three criteria, some have a mixed or a general approach.

Focus

on

the

conceptual

approach

Conceptual formallanguages are interested in knowledge representationoftherealworld,focusingonmodeling enti-ties,activities,actorsandassertionsofadomain.

Conceptual formal languages are very expressive and accuratebecausetheyofferopportunitiestotranscribeina moreorlessdirectlyexpressedneedsandtherealitymodel inunambiguousterms.Theirapplicationtoengineering sys-temsisexcellentsincetheyprovidethreemajoradvantages

[14]:

• reading and management models are easier, especially sincetheproduced formaldescriptionsareclosetothe vocabularyoftheconsidereddomain;

• theyhaveinferencemechanismswithlogicalfoundations. Thesemechanismsalloweasy implementationof proce-duresforformalverification;

• intermsofchecksandvalidationsmadeonformalmodels, presentationof theresultsinterms thataredefinedby andsalienttotheinvolved actorscreatesconfidence in thequalityandsafetyofthemodels.

Wepresentbelowalanguageofthisfamily,namelythe conceptualgraphformalism,whichisusedforcomplex sys-temsmodelingdrivenbyontologies(Fig.3).

Conceptualgraphs:presentation

Theconceptualgraphformalismisalanguageforknowledge representation inspired by semantic networks [15] which resultedinanumberofstudiessinceitsintroductionin1984 byJohnSowa.

Aspecialfeatureofthislanguageistorepresent knowl-edgeinagraphicform.Morespecifically,aconceptualgraph

[16]is abipartitegraph,thetwoclassesof verticesbeing labeledbytherespectivenames‘‘concepts’’andthenames of ‘‘conceptual relations’’ between these concepts. Such a graphical representationof knowledge enables usersto understand,create,ordirectlymodifyobjectsofthistype, somuchsimplerwithalogical representationof such for-mulas.

The ease of use of the formalism is reinforced by an explicit separation of different types of knowledge.

System

S

Onto logyO

based on image of ModelM

Figure3. Systemsmodelingdrivenbyontologies.

Lamodélisationdessystèmesentrainéeparlesontologies.

Different types of knowledge are indeed represented by suchdissimilar distinct objects andthe structure leadsto greaterclarityintheuseofthisformalismconcerningthe acquisitionorknowledgemodeling.Thevocabularyfor rep-resentingknowledge(ontology)isstructuredinsuchamodel objectcalled‘‘support’’ forrepresentingsimplewaylinks ‘‘sortof’’and‘‘is’’.

The other advantage of the formalism is that reason-ingcanbeperformedontheknowledgerepresented.These arguments vary onthe choice of a very abstract styleto a more graphic style[17]. In particular in this paper,we preferthe second approach becauseit developsviewable argumentsthatrelyontheworkofalgorithmicgraphtheory. Finally,theformalismhassomesemanticsinfirstorderlogic thatisadequate andcompletewithrespecttothe deduc-tion. These characteristics are useful to generate formal modelsforthedescriptionofinformationsystems architec-ture,inthisparticularcaseoftelemedicine[18].

Conceptualgraphs:handling

All the features mentioned above in the use of concep-tual graphs for modeling complex systems can provide a better understanding of thescope, a fluid or harmonized communication,especiallyautomationoftheanalysiswith inpremiumdetailedreasoning.

As part of our problem of verification in telemedicine models,wechoosetoreadtheconceptualgraphformalism, becauseithasthefollowingadditionaladvantages[19]: • first,itsability tomodel the knowledge in thefield by

producingaprecisevocabularythatformalizesmodels; • second, graphs areeasily manipulated (join,

decompo-sition)and understandable by a‘‘final’’ user (asystem engineer,orevenanon-expertspecialistfieldformalism), astheyarenottoolarge;

• third, the arguments can be made with graph opera-tions thatallow to rigorouslyanalyze therequirements ofmodelsoftelemedicineandeventuallytheemergence ofnewones;

• andfinally,predominantquality,thesearguments‘‘with drawings’’canbeeasilyexplainedtoauseronthe repre-sentationthathebuilt.Thisexplanatorypowerwouldbe lostiftheargumentsweremadelogically.

Inaddition,applicationsrelatingtotherecent outstand-ingadvanceofsemanticwebprovideevidenceofinterestfor theinformationsystem andknowledge management com-munities.

Semantic

formalization

with

conceptual

modeling

This workaimstoprovide a frameworktoaid theuser in themodelingprocess,fromwriting specificationsuntilthe formalanalysisofprocessmodelsfortelemedicine.

Itseemsnecessary:

• tobuild amodeling frameworkthatsupports arigorous formulationoftheneedsandknowledgeoftheconsidered domain;

• tohaveamethodologytocollectandorganizeknowledge inaformalwayfor greaterefficiencyduringthephases ofverificationandvalidationimplyingmodelsofsystems thatmayincludetelemedicine;

• to define mechanisms for verification and validation to ensurethatalloperationsofthedevelopedsatisfyallthe expressedneedsandrespecttheknowledgeaxiomsthat areavailableinadomainanditsenvironmentaccording toaconsideredviewpoint.

Forthisweuseacombinationoftwobasicprinciples: • anapproachtomodelingrequirements,

• anapproachusingconceptualgraphs.

These approaches are complementary and it is inter-esting to combine them into a coherent framework to take advantage of each of these formalisms and reduce their weakness. Indeed, the combination provides a very expressiveformalframeworkthatprovidesawiderangeof concepts formodeling variousaspects.This jointuse also improves the simplicity of themodeling concepts by pro-vidinghighlevelsadaptabletodifferentareasofmodeling. Finally, this formal framework provides the methodologi-calmeans toensurethatthedevelopedsystem meetsthe expectationsoftheenduser.

There could be some similarities between these con-ceptual modeling procedures and other approaches from conceptual modeling to requirements engineering in information systems and software technologies [20—22]. However,tofully address the issuesguiding and adapting changes in IT systems, a consistent taxonomy of process models,describingasetofmodelsandassociatedmethods canbehelpfulinchoosingappropriateapproachesadapted tocontextualneeds[23].

An

approach

using

conceptual

graphs

The design and development of computer systems are increasinglybasedontheassemblyoftestedandvalidated softwarecomponentsthatcanbereusedinapersonalized way(orsemi-customized).

Theideatodefinereusabletemplatesspreadtoseveral areas,includingspecificcontextuallanguagewhichdefines initsmodelingframeworkthenotionofpartialmodelthatis intendedtobereusedbycertainclassesoftelemedicine sys-tems.Morerecently,worksonontologiesemphasizeaspects

Environment Analysis of properties in behavioural and functional terms System Formalized Requirements in Conceptual Graphs Expression of Requirements Systemic Requirements Domain requirements User Requirements Domain Ontology

Conceptual Graph-based Verification

Taxonomies, values, beliefs and axioms Modeling Requirements precond implication Activity Decision Request effect Tele-service Characterisation of requirements Reasoning Mechanisms Constraints Graph Rules Projection Improvements Performance Stability Intégrity Analysis Perspective

Figure4. Stepsoftheproposedresearchapproach.

Lesétapesdel’approchederechercheproposée.

ofreuseandformalization.Anontologyisaformal descrip-tion of entities, relationships and constraints in order to allowseveralgroupstoshareandexchangeknowledge[24]. Thedifferentstepsofthesuggestedapproacharedescribed inFig.4.

Informative

and

illustrative

guidance

in

specific

situations

Asafirststep,wewilldevelopanexampleofatelemedicine systemofdeployingaterritoryandforpatientswithchronic illnessrequiringregularmonitoring,measurementand auto-maticrecoveryofdataconnectedbyelectronictransmission toahospital[25].Thismethodhastheadvantageof allow-ingthemonitoringofcertainparametersandtriggerifneed medicaladviceoremergency.

To begin with, define the purpose (experimentation, make it possible to monitor, save lives), mission (launch monitor patients andinterventions) and theobjectives of thesystem(improvingthesurvivalrateofx%improvethe qualityof life, reduce costs). This step requires, in most cases, several exchanges between the design and imple-mentation at all levels. Indeed, every defined element is reassessedand possibly amended thereafter.Then it is necessary toidentifythe interfaceswiththe outside:the patient,theattendingphysician,the manufacturerofthe device, thecommunication network,the hospitalservice, the funding institution, the patient’s family. Then it is a question of determining the services that must be ren-deredorexpectedofeachoftheelementsof thecontext

(measuring physiological parameters on the patient, pro-vidinginformationtothenursemonitoring,reimbursement by the funding agency, using the communication network ADSL...).Moreover,itisusefultospecifytheinterfacesof our system with itsenvironment: the physical links (sen-sor,screen,form,networkcommunication...)andflowsthat aretraded(physiologicalmeasures,patientdataencryption acts,encrypteddata...).

Forexample,thecycleofcareforbreastcancerhasbeen engineeringwork,arichsystemofteachings,whichhelped tobringverynoticeablebenefitsfor itsusers(oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, surgeons...). At first, it wasto conduct an analysisand then tomodelthe current cycle. This phase is to identify how the information about the patientand thediseaseareprocessedin each stage (pre-vention,screening,diagnosis,characterizationofthetumor, treatment,medicalcare)andtostartengineering.Suchan approachallowsintroducing naturallyandfullyintegrated telemedicine:atscreening(readingdistanceshots), diagno-sisandcharacterization(teleconference peer),monitoring oflong-termtreatment(dailymeasurementandelectronic transmission of certain physiological parameters) or the overallmonitoringofremission.

The definition of need and requirements analysis can have a complete and consistent set of requirements and constraintsvalidatedbystakeholders.Inourexample,this willlistboththefunctionalneeds(patient’sbloodpressure tocheck...)andperformance(monitorpatientsthroughout theterritorycoveredbythehospital,measureandtransmit certainparametersforcing thepatienttoremainstillless

thanhalfanhouraweek...).Wecanalsoformalizethe secu-rityrequirementsfortheoperation(objectivesofreliability, security, and privacy), cost constraints and compatibility with existing systems (computer systems, organization of hospitalservices).

The design of the functional architecture defines the mainfunctionsofthesystem(measuring,display,triggera medicalprocedure...)andseeshowtheyfittogetherfrom a staticpoint of view(definition of flowsexchanged) and adynamicperspective(inrelationtothestatesofthe sys-tem and its operatingmodes: unplugged, in test, in use, in alertlevels...).The designprocess oforganic architec-ture,meanwhile,willidentifythecomponentsofthesystem (medicaldevice,communicationdevice,computer worksta-tion,software,technicalsupportpersonnel,anddoctors... intheborderofthesystemthathasbeenchosen)andthe linksbetweenthem,andtheallocationoffunctionsofthese constituents.

Information

system

design

for

telemedicine

implementation

Themostimportantsuccessfactorintheinformationsystem design for telemedicine applications is the combined use ofdesign scienceandparticipatory approachestodevelop an ICT-based healthcare for rural communities through focusing on core indicators and the related sustainability challenges. The participatory approach is a social prob-lemsolvingperspectiveforbetteranalyzingthesocialand culturaldimensionsintheuser’scontextinordertoensure furthercompliancebetweeninformationsystemdesignand local user reality [26]. The design science approach for information systemsis a research strategyto gain knowl-edge and understanding about a knownresearch problem

[27], according to three cycles of inquiry: a relevance cycle for requirements of elicitation and contextual veri-fication, a rigor cycle for determination of the pertinent knowledge base and frameworks, and a design cycle for prototype development and evaluation [28]. Hence, the designed research project is leading the assessment of this modality in order to improve on its practicality and effectiveness. Consequently, designing a sustainable sup-port system for rural healthcare delivery in a specific country environment signifiesthe establishment of a suc-cessful development and implementation of the system. Thisgoalcanbeachievedbyactionsguaranteeingresearch approachesthataremorecontextual,reportmoreonsetting factors, engage more participatory and pragmatic design processesandreportresultseffectivelyandopenlyontopics significanttoprospectiveapprovingpatients,physiciansand managerialdecisionmakers[29].

Itisstillusefultoclarifythecontextualsituationbetter, toexamine potentialimprovements andtospecify formal rulesthatmustbeestablishedatinformationsystemlevel. These rules can allow us todescribethe various types of required properties of the concepts in the telemedicine domain.Generally,ruleswithintheinformationsystemare broadlyclassifiedintotwodistinctcategories[30].Thefirst category refers mainly to organizational rules concerning resources managementandproceduresneeded to guaran-teelegalandethicalcompliance.Inthesecondcategory,the

communicationrulesaregenerallydesignedtoprocessdata of exchanged messages engendered by the telemedicine activitiesfor makingand prioritizingdecisionsand associ-atedremoteactions.Theverificationandvalidationofrules impactontheadequacy andappropriateness of usingthe valueof telemedicineservicesforcontinuouslyoptimizing healthcareoutcomes. We represent below an example of conceptualgraphrulestomodelthecontextualsituationin thetelemedicinescenariothatrequirescoronary catheter-ization(Fig.5).Itisperformedforbothcardiologydiagnostic andtreatmentprocedures.

Ethical

considerations

latent

in

global

situations

of

telemedicine

Ethicsinmedicineexaminethephilosophyandcore princi-plesofhowmedicalproceduresandmedicalpracticesare executed.Medicalethicalissuesfallwithintheframework traditionallyascribedtothedoctor-patientrelationshipand aregroundedinthefourfundamentalethicalprinciples[31]: • respectforthedignityofpersonsthatrecognizesrespect for human rights(e.g.,privacy, self-determination,and personalliberty);

• responsiblecaringthatsupportsanactiveconcernforthe welfare of thepersons. This includes actions, interpre-tations, choices andrecommendationsthat trytoavoid harm,minimizeharmthatcannotbeavoided,andcorrect harmwhenitispossible;

• integrityinrelationshipthatpromotescompletenessand opennessofcommunicationwithcontextualvariancesand expectations regarding appropriateness. This needs to monitor,andmanagepotentialbiases,multiple relation-ships,andotherconflictsofinterest;

• Responsibility tosociety thatreflects commonconcerns for thewelfareof allhuman beingsinsociety in accor-dance with the established laws, social structures and thepublicinterest.Thisimplieschoosingthemost appro-priate and beneficial use of available knowledge and technologiestoimprovethewelfareofallhumanbeings insociety.

The introduction of new remote procedures with telemedicine adds a layer of complexity tothe notion of ethical expectations. This complexity increases with the state of diffusion, adoption andapplication of new infor-mation and communication technologies in the stage of telemedicine[32][33]:

• atthefirststageoftelemedicine,thereistheuseof mul-timedia and exchange tools (email, videoconferencing, jointdevelopmentofwebsites).Compliancewithasetof ethics,involvesissuesofdatasecurity,respectofmedical confidentiality,andcompensationpoliciesfor practition-ers;

• atthesecondstageoftelemedicine,thereisthe involve-ment of non-medical third parties (medical devices or non-medicalstaff).Suchisthecase,forinstance,ofthe telemonitoringinwhichthemainproblemconcerns peo-plewhoaremedicallydependent,butalsointheremote robotizedtransmissionsforteleassistanceactivities. Ethi-calproblemsthenshifttothelegaldomainwiththenotion ofindividualorsharedresponsibilityininterprofessional relationships;

Conclusion

Implication Hypothesis

Has-ConcernedPatient

Telemedicine_Task: Tele-Task Patient: P HasStatus Chest_Pain: CP

Require

Telemedicine_Task: Tele-Task CoronaryCatheterization: cc

Exampleof organizationalrule

Ischemic Heart Disease: IHD Possible aetiology

Object Cardiology Procedure: cpr

Figure5. Exampleofaconceptualgraphrule.

Exempled’unerègleorganisationnelleengraphesconceptuels.

• at the third stage of telemedicine, there is the deploymentofintelligentsystemswithknowledge-based information components for visual support in critical decision-making.Thesesystemspavethewaytothe inte-grationofnumericalandsymbolicprocessingforlearning and explanations of reasoning. This generates a new complementarystyleofhuman-computerinteraction,in whichthecomputerizeddevicebecomesasmart,active andpersonalizedcollaborator.Therefore,intelligent sys-temsaredirectlyinvolvedinthedecisionprocessesthat are ultimately performed and assumed by the medical practitioners.Thedeterminationofcomprehensive medi-calcareforthewell-beingofpatientsisasensitivetopic andsubjecttovariousrepresentations.

By theremotemedicalserviceswhich theyhave deliv-ered, the activities of telemedicine have opened ethical issues that impose new requirements and create some legalchallengesconcerningmanydifferentinterpretations of human rights and fundamental freedoms. The priority projects of telemedicine would generate certain experi-ences,knowledgeable approaches and bestpracticesthat canbesharedforthecommongood.

Conclusion

A control stepanalysis model becomes essential, sinceit conditionsthe proper implementation of thesystem. Any approachfacilitatesformalanalysisofmodels,verification

ofcompliancewithexpectedrequirements, contributesto thereductionoftimeinherentinthecompletionofthisstep, asthefollowingsteps.Anadditionalrequirementtoachieve

thisgoalandensurethevalidityofthemodelsdevelopedis to formalize the maximum specifications while producing understandableconstructions.

Despite thesubstantial body of existinglanguages and methodsinmodelingactivities,mostoftheprocedureslack verification tools and validation. Hence, the difficulty of ensuringthattheobtainedmodelsleadtocompliancewith therequirementsexpressedinastudiedsystem.

Basedonthisobservation,wesettheobjectiveof defin-ingamethodologytohelpthemodelingandrigorousanalysis oftherequirementsoftelemedicinesystems.Ononehand, thismethodologywillbebasedonaformalrepresentation of requirements(systemic,generic domain, etc.)withina knowledgebasethatwillbearequirementsrepository.On theotherhand,thismethodologywilluseconceptualgraphs (CG)fortheformalizationofontologyofactivitiesandthe productionofargumentsrelatedtotheformalverification ofmodelsbuiltfromthisontology[34].

The importance of this modeling and rigorous analysis oftherequirements oftelemedicinesystemsis evenmore apparentsincetherecognitionofthegenericrepresentation is declinedintwometa-models: thefirstcovers the activ-itiesof teleconsultation,teleexpertiseandteleassistance; the second concerns the telemonitoring. The framework designedfortheanalysisoftheassociatedinformation sys-tem needs to be considered in this perspective. Actions andmodalitiesaimedat puttingthetelemedicine applica-tions into place, therefore, must be compatiblewithand contribute tothebroadestoperational deploymentof the remotehealthcareservices.Itis reallybelievableand sig-nificant togathertechnologyintelligenceontelemedicine implementation [35], to support the general purpose of improvinghealthcaredelivery.

Telemedicine is a wonderful tool for the continuous improvement of patients’ health by its quality, timeli-ness,informationandcommunicationtechnologiesthatare increasinglyinnovativeandspecialized[36].However,there arestill ethicalandlegal issues(e.g. confidentiality, free choice,individual andcollectiveresponsibility) [37]. They would find adaptability to progress, if possible, correct responses,tothequestioningandrelevantreflectionneeded tobringaboutoperationalchange.Finally,itisimportantto considerthattheintegrationoftelemedicineinthe health-caresettingisthepromotionofinnovationascontributingto asustainableincreaseinthegrowthpotentialofthe medi-calprogramsorservices[38].Intheinterestofpatients,all stakeholdersmustconformtoacertainnumberofgeneral rules,codes andprinciplestoputthepatient’sneedsfirst andbuildahealthcaresystemthatwouldprovidemedical servicesfortheindividualwhoissick.

Disclosure

of

interest

Theauthordeclaresthathehasnoconflictofinterest con-cerningthisarticle.

References

[1]ZaveP.Classificationofresearcheffortsinrequirements

engi-neering.ACMComputSurv1997;29(4):315—21.

[2]Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Hundt AS,

HoonakkerP,Holden R.Human factorssystemsapproach to

healthcarequalityandpatientsafety.ApplErgon2014;45(1):

14—25.

[3]BlumBI.Softwareengineering:aholisticview.Oxford

Univer-sityPress;1992.

[4]JacksonM.Softwarerequirements&specifications:alexicon

of practice, principles and prejudices. New York, NY, USA:

Addison-WesleyandACMPress;1995.

[5]EasterbrookS,CallahanJ.Formalmethodsforverificationand

validationofpartialspecifications:acasestudy.JSystSoftware

1998;40(3):199—210.

[6]Dibie-BarthélemyJ,HaemmerléO,SalvatE.Asemantic

vali-dation of conceptual graphs. Knowl-Based Syst 2006;19(7):

498—510.

[7]Kamsu-FoguemB,Tchuenté-FoguemG,FoguemC.Using con-ceptual graphs for clinical guidelines representation and knowledgevisualization. Inform Syst Front2012, http://dx.

doi.org/10.1007/s10796-012-9360-2.

[8]Kamsu-FoguemB,Tchuenté-FoguemG,AllartL,YoucefZennir,

VilhelmC,MehdaouiH.User-centeredvisualanalysisusinga

hybridreasoningarchitecture forintensive careunits. Decis

SupportSyst2012;54(1):496—509.

[9]Kamsu-Foguem B, Diallo G, Foguem C. Conceptual

graph-basedknowledge representationfor supporting reasoning in

Africantraditionalmedicine.EngApplArtifIntel2013;26(4):

1348—65.

[10]Kamsu-FoguemB.Knowledge-basedsupportinnon-destructive

testingforhealthmonitoringofaircraft structures.AdvEng

Inform2012;26(4):859—69.

[11]Croitoru M, Oren N, Miles S, Luck M. Graphical norms

via conceptual graphs. Knowl-Based Syst 2012;29:

31—43.

[12]BagetJF,MugnierM-L.Extensionsofsimpleconceptualgraphs:

the complexity of rules and constraints. J Artif Intell Res

2002;16:425—65.

[13]NuseibehB,EasterbrookS.Requirementsengineering.

Ency-clopediaofphysicalscienceandtechnology.3rded.SanDiego

(USA):ElsevierScienceLtd;2003.p.229—36.

[14]SowaJF.Knowledgerepresentation:logical,philosophicaland

computationalfoundation.PacificGrove,CA:BrooksCole

Pub-lishingCo;2000.

[15]Quillian MR.SemanticMemory.In:Minsky M,editor.

Seman-ticInformationProcessing.Cambrige:TheMITPress;1968.p.

227—70.

[16]SowaJF.Conceptualstructures:informationprocessinginmind

andmachine.NewYork(U.S.A):Addison-Wesley;1984.

[17]Chein M, Mugnier ML. Graph-based knowledge

representa-tion:computationalfoundationsofconceptualgraphs.series:

advanced information and knowledge processing. London

(UnitedKingdom):Springer;2008.

[18]Sowa JF,ZachmanJA.Extendingand formalisingthe

frame-work for information systems architecture. IBM Syst J

1992;31:590—616.

[19]CheinM,CroitoruM,MugnierM-L.Visualreasoningwith

graph-basedmechanisms:thegood,thebetter,thebest.KnowlEng

Rev2013;28(3):249—71.

[20]EtienA,RollandC.Measuringthefitnessrelationship.Requir

EngJ2005;10:184—97.

[21]Rolland C.Fromconceptualmodellingtorequirements

engi-neering.In: Embley D,Olivé A, RamS, editors.Conceptual

modeling—ER.Berlin/Heidelberg:Springer;2006.p.5—11.

[22]Rolland C, Salinesi C. Supporting requirements elicitation

throughgoal/scenariocoupling.ConceptualModeling:

Foun-dationsandApplications2009:398—416.

[23]CéretE,Dupuy-ChessaS,CalvaryG,FrontA,RieuD.A

taxon-omyofdesignmethodsprocessmodels.InformSoftwareTech

2013;55:795—821.

[24]UscholdM,GruningerM.Ontologies:Principles,Methodsand

Applications.KnowlEngRev1996;11(2):93—136.

[25]MoucheroudG.Ingénieriesystèmeettélésanté.TIC&santé:

au-delàdel’innovationtechnologique?Paris,France:Kalisté,

AltranTelecoms&Media;2010[French].

[26]Heeks R. Information systems and developing countries:

failure, success, and local improvisations. Inform Soc

2002;18:101—12.

[27]Peffers K, Tuunanen T, Rothenberger MA, Chatterjee S.

Designscienceresearchmethodologyforinformationsystems

research.JManageInformSyst2008;24(3):45—77.

[28]HevnerAR.Athreecycleviewofdesignscience.ScandJInform

Syst2007;19(2):87—92.

[29]Glasgow RE, Phillips SM, Sanchez MA. Implementation sci-enceapproachesforintegratingeHealthresearchintopractice and policy. Int J Med Inform 2013, http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.07.002.

[30]Nageba E, RubelP,Fayn J.Towards anintelligent

exploita-tionofheterogeneousanddistributedresourcesincooperative

environmentsofeHealth.IRBM2013;34(1):79—85.

[31]Canadian Psychological Association, Retrieved from http:// www.cpa.ca/cpasite/userfiles/Documents/publications/ guidelines%20for%20psychological%20practice%20women.pdf

[32]BérangerJ,ManciniJ,DufourJ-C,LeCozP.Évaluationéthique

dessystèmesd’informationauprèsdesacteursdesanté.

Euro-peanResearchinTelemedicine/LaRechercheEuropéenneen

Télémédecine2013;2(3—4):83—92.

[33]Béranger J,Mancini J,Dufour J-C,LeCoz P.Mise enplace

humainedessystèmesd’informationencancérologie:mesure

dudegréd’applicabilitédesmoyensetdedésordre(entropie).

IRBM2012;33(5—6):308—15.

[34]Kamsu-FoguemB,Tchuenté-FoguemG, FoguemC.Verifiying amedicalprotocolviavisualmodeling:thecaseofa nosoco-mialdisease.JCritCare2014;29(4):690—8,http://dx.doi.org/

[35]BehkamiNA,DaimTU.ResearchForecastingforHealth

Infor-mationTechnology(HIT),usingtechnologyintelligence.

Tech-nologicalForecastingandSocialChange2012;79(3):498—508.

[36]Doumbouya MB, Kamsu-Foguem B, Kenfack H, Foguem

C. Telemedicine using mobile telecommunication: towards

syntactic interoperability in teleexpertise. Telemat Inform

2014;31(4):648—59.

[37]Kamsu-FoguemB,Tchuenté-FoguemG,FoguemC.Conceptual graph operations for formal visual reasoning in the medi-cal domain. IRBM 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.irbm.

2014.04.001.

[38]Kamsu-Foguem B. Systemic modeling in telemedicine. Eur ResTelemed 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurtel.2014.