ScienceDirect

EuropeanJournalofRadiologyOpen2(2015)32–38

Test-positive

rate

at

CT

colonography

is

increased

by

rectal

bleeding

and/or

unexplained

weight

loss,

unlike

other

common

gastrointestinal

symptoms

D.

Hock

a,∗,

R.

Materne

a,

R.

Ouhadi

a,

I.

Mancini

a,

S.A.

Aouachria

a,

A.

Nchimi

b aDepartmentofMedicalImaging,CentreHospitalierChrétien(CHC),RuedeHesbaye,75,B-4000Liège,BelgiumbDepartmentofThoracicandCardiovascularImaging,CHUdeLiège,DomaineUniversitaireduSartTilman,BâtimentB35,B-4000Liège,Belgium

Received19December2014;accepted23December2014 Availableonline8January2015

Abstract

Purpose: Weevaluatedtherateofsignificantcolonicandextra-colonicabnormalitiesatcomputedtomographycolonography(CTC),according

tosymptomsandage.

Materialsandmethods: Weretrospectivelyevaluated7361consecutiveaverage-risksubjects(3073males,averageage:60.3±13.9;range18–96

years)forcolorectalcancer(CRC)whounderwentCTC.Theyweredividedintothreegroupsaccordingtoclinicalsymptoms:1343asymptomatic individuals(groupA),899patientswithatleastone“alarm”symptomforCRC,includingrectalbleedingandunexplainedweightloss(group C),and5119subjectswithothergastrointestinalsymptoms(groupB).Diagnosticandtest-positiveratesofCTCwereestablishedusingoptical colonoscopy(OC)and/orsurgeryasreferencestandard.Inaddition,clinicallysignificantextra-colonicfindingswerenoted.

Results: 903outof7361(12%,95%confidenceinterval(CI)0.11–0.13)subjectshadatleastoneclinicallysignificantcolonicfindingatCTC.CTC

truepositivefractionandfalsepositivefractionwererespectively637/642(99.2%,95%CI0.98–0.99)and55/692(7.95%,95%CI0.05–0.09).The pooledtest-positiverateingroupC(138/689,20.0%,95%CI0.17–0.23)wassignificantlyhigherthaninbothgroupsA(79/1343,5.9%,95%CI 0.04–0.07)andB(420/5329,7.5%,95%CI0.07–0.08)(p<0.001).Agingandmalegenderwereassociatedtoahighertestpositiverate.Therate ofclinicallysignificantextra-colonicfindingswassignificantlyhigheringroupC(44/689,6.4%,95%CI0.04–0.08)versusgroupsA(26/1343, 1.9%,95%CI0.01–0.02)andB(64/5329,1.2%,95%CI0.01–0.02)(p<0.001).

Conclusion: Bothtest-positiveandsignificantextra-colonicfindingratesatCTCaresignificantlyincreasedinthepresenceof“alarm”

gastroin-testinalsymptomsespeciallyinolderpatients.

©2015TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierLtd.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Keywords: Colorectalcancer;CTcolonography;Gastrointestinalsymptoms

1. Introduction

Colorectalcancer(CRC)isthesecondcauseofcancer-related death[1]andgenerallyresultsfromthetransformationof clini-callysilentadenomas[2]thataresoughtbyscreeningtests[3].

Persistenceorsuddenoccurrenceofvariousabdominal

symp-toms is often considered an indication to search or rule out

colonicabnormalities,including CRCor precancerouspolyps

[4].Literaturesuggeststhattheuseofopticalcolonoscopy(OC)

iswarrantedonlyfor subjects withrectal bleeding and

unex-plainedweightloss[5],whereastheothersymptoms’specificity

∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+3242248800;fax:+3242248810. E-mailaddress:danielle.hock@chc.be(D.Hock).

remain questionable[6–8].Meanwhile, the current diagnosis

guidelinesforindividualswithaverage-riskforCRConlyapply ifthereisnogastrointestinalsymptomorcomplain[2],raising potentiallyimportantconcerns.Indeed,aslongasallsymptoms areconsideredequivalentintermsofdiagnosticyield, individ-ualswithnonspecificgastrointestinalsymptomsareevaluated, whenneeded,byOC,causingpotentialcongestionofthe facil-itiesby lowresection-rateprocedures[9–11].Second,patient

compliancetocurrentCRCscreeningguidelinesislow.Almost

50%ofasymptomaticsubjects50yearsofageandolderescape

screeningprogramsoveraperiodof10years[12],whilesubjects

with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms agree toundergo

colonic explorations, for reassurance in a greater percentage

[7].

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejro.2014.12.002

2352-0477/©2015TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierLtd.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Computed tomography (CT) colonography (CTC) has

emerged over the past decade as an accurate and less

inva-sivealternativetoOCinseriesofsymptomaticpatients[13,14]. Similarlygoodresultswereobtainedinseriesofasymptomatic subjects[15].Toourknowledge,therearelittledataevaluating thetest-positiverateaccordingtogastrointestinalsymptomsat CTCintheliterature.Thishasimplicationsforrisk-stratification

andpotentiallyimpacts CRCscreening recommendation. We

thereforeevaluateinthisstudy,thedistributionofclinically sig-nificantcolonicfindingsandextra-colonicatCTC,accordingto

symptomsandagethroughareviewofa7-yearexperienceina

singlenon-academiccenter.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Patients

Ourinstitutionalreviewboardapprovedthestudyand autho-rized this retrospective patient data analysis without further

consent. We searched our hospital records for all subjects

who completed a CTC procedure between June 2003 and

August2010.Thissearchyielded9122subjects(3822males,

5300females,averageage:60.11±13.75years,range:18–96

years). Indications for CTC included screening and direct

referral (n=8573), secondary referral after incomplete OC

(n=285),andDoubleContrastBariumEnema(DCBE)referral

change(n=264).Thisreferralchangewasjustifiedbythe

non-superiorityof DCBEoverCTC forcolonic lesionsinseveral

studies[16,17].

Writteninformedconsentwasgivenbyallsubjectspriorto procedures.1761subjectswithafamilialorpersonalhistoryof

polypsor colorectal cancer,genetic conditions, inflammatory

boweldisease,whowereatincreased-orhigh-riskfor colorec-talcancer[2]wereexcluded.Theremaining7361subjects,with

average-risk [18]for CRC (general population)(3073 males,

4288 females, average age: 60.3±13.9 years, range 18–96

years)wereevaluated. Theirclinicalstatus withregardtothe

presence ofthe following gastrointestinalsymptoms, prior to

CTCwasretrievedfromthereferralformsand/orgatheredby

patient’sanamnesisandallotheravailablepatientdata, includ-ing: (i) abdominal pain, (ii) constipation, (iii) diarrhea, (iv) irregularbowelmovement,(v)bloating,(vi)melena,(vii)rectal bleeding,and(viii)unexplainedweightloss.Weretrospectively assignedthesubjectstothreemaingroups,accordingtothe pur-portedclinicalimportanceofthesesymptomsregardingthelevel ofspecificityforCRC[5]:groupAincludedtheasymptomatic

subjects; groupB, the patients withone or morenonspecific

symptom(s) (i–vii) in the absence of an established “alarm”

symptom(viiandviii),whowereassignedtogroupC. 2.2. CTCtechnique

Allpatientsunderwentthesamestandardizedprocedurethat consistedintothree stepsincluding patientpreparation, scan-ninganddatainterpretation.Thepreparationinvolvedtwosteps

including cathartic colonic cleansing and residual fluid

tag-ging.Forpatientsingoodgeneralcondition,coloniccleansing

was achieved by a one-day clear liquid diet, one bottle of

sodium phosphate preparation (Fleet-Phospho-soda®, Wolfs,

Zwijndrecht,Belgium)and4tabletsofbisacodyl(Dulcolax®, BoehringerIngelheim,Ingelheim,Germany).Forfrailpatients,

cleansing consistedinto2 days of low-residuediet combined

to8gofmagnesium–sulphateontheexaminationday’s

morn-ing,inadditionto2tabletsofbisacodyland100mlofcontrast

agent(Gastrografin®,ScheringAG,Berlin,Germany)twicea

day.Inpatientswithrenalinsufficiency,cardiacfailureorsevere hypertension,preparationconsistedin3daysoflow-residuediet with2lofMoviprep®(Norgine,Heverlee,Belgium) (propylene-glycol+ascorbicacid)and4tabletsofbisacodylthedaybefore thestudy.Residualfluidtaggingwasobtainedbyingestionof 100mlGastrografin®theeveningbeforetheprocedureandtotal

colonicresidualfluidvolumewasreducedbyusinga

supposi-toryofbisacodylapproximately2hbeforeexamination,except

for patientswhounderwentCTCafter incompleteOC. These

patientsdrank100mlofGastrografinandinsertedasuppository ofbisacodyl1hbeforetheprocedure.Beforedataacquisition,an

ivinjectionof20mg/1mlofBuscopan®(butylhyoscinbromid

– Boehringer Ingelheim, Bruxelles,Belgium) was performed

andarectal cannula was inserted for colonicdistensionwith

an automaticcarbondioxideinsufflatorVMX-1010A(Vimap

technologiesTM,Girona,Spain).

A32-row(GELightspeedVCTTM,GEHealthcare,

Milwau-kee, WI)until09/2010,thena64-row(GEDiscoveryCT750

HDTM, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) multislice scanners

were used for image acquisitions. Parameters consisted into

1.2mm-thick slices with a 0.625mm reconstruction interval,

usinga50mAslow-doseprotocolswithvariablekV,adjusted

tobody-densityfordosereduction,supplementedsince2010by anadaptivestatisticaliterativereconstructionalgorithm(ASIR)

(GEHealthcare,Milwaukee,WI).Twoacquisitionswere

per-formed: the first in supine position andthe second, either in proneposition,or rightdecubitusfor unfitandobesepatients.

Immediatereviewof theimageswasperformed bya

radiolo-gistinallcases.In897patients(10%),athirdacquisitionwas

orderedbecauseof asegmentalcollapse preventingconfident

analysis.

Reading was performed offline on a workstation

(Advan-tageWindows,GEHealthcare,Milwaukee,WI)withasoftware

(Colon VCAR) allowing filet-view, supplemented by

“com-puter aided diagnosis” (CAD) assistancefrom January 2009,

andelectroniccleansingfromJune2010.Reconstruction

algo-rithms,imagedisplaypreferencesandreadingprinciplesused

forinterpretationaredescribedelsewhere[19].WeusedC-RAD reportingclassificationforallfindings[20].Eachfinding was

assigned tobothacolonicsegmentandadistancetotheanal

margin.

2.3. Dataanalysis

Clinicallysignificantcolonicfindingsweredefinedaseither

≥6mmpolyps,massesorothersrequiringwork-uportreatment

[20].Clinicalfiles,andreportsweresearchedforrepeatCTC, OCandsurgicalproceduresaftertheinitialCTC,when

standardfindings,usingavailablelocationbysegment,and/or distancefromtheanalmargin.Wedidnotattempttomatchusing

thesizecriteriabecause ofknownsizediscrepanciesbetween

OC and CTC polyp measurement [21]. Using an “intention

totreat”algorithm,per-patient CTCdiagnostic valuesforthe diagnosisofclinicallysignificantcolonicfindingswere calcu-lated.Patientswithatleastonematchedfindingwereconsidered

true-positivewhilepatientswithCTCfindingsunmatchingthe

referencestandardwereconsideredasfalse-positive.Thosewith nofindingatCTCandatleastonepositivefindingonthe refer-encestandardswereconsideredfalse-negative.

For patients with several colonic findings, two clinicians

having access to all available data were requested to

deter-mine inconsensus, the most significant withregard toCRC.

Forexample,an individualwithbotha>6mmcolonic polyp

andanon-neoplasticcolonicmassaccounted,foronlythefirst. In addition, theywere requested to establish a potential

cor-respondencebetweentheclinicalsymptomsandCTCcolonic

andsignificantextra-colonicfindings(i.e.:E4gradeoftheCTC ReportingandDataSystem,unrelatedtoacolonicdisease). 2.4. Statisticalanalysis

Percentages are given with their 95% Confidence

Inter-vals(CI).Continuousvariablesarecomparedusinganalysisof

variance,andtwo-tailedt-testsareusedfor directcomparison

betweentwogroups.Pearsonchi-squaretestsareusedto

com-pareproportionsandpercentages.Weusedaregressionanalysis toevaluatetheimpactofthegroupofsymptoms,ageandgender onthetest-positiverate.Ap-valueoflessthan0.05denotesa statisticalsignificance.

3. Results

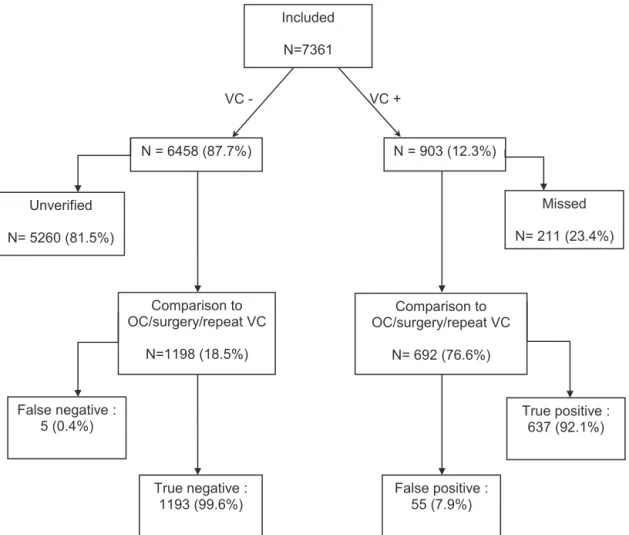

Fig.1summarizesthepatientflowchartinthisstudy.903out

of the 7361(12%,95%CI 11–13%)subjects hadatleastone

clinicallysignificantcolonicfindingatCTC.Histopathological diagnosesand/oretiologyfortheconfirmedfindingsaregivenin

Table1,showingthattheabnormalitiesweremostcommonlyof

mucosalorigin.ComparisonofCTCtoOCand/orsurgerywas

possible for692/903(77%;95%CI0.074–0.79) ofthese

sub-jects. CTCfindingswereconfirmedin637,while55 patients

werefalse-positive.Inaddition,repeatCTC,OCand/orsurgery

was performed within arange of 6–60 months in1198

sub-jectswithnegativeCTCfindingsforthefollowingreasons:656

patients underwentOCincludingprogrammedscreeningtests

in 168, exacerbation of a“non-alarm” gastrointestinal

symp-tom oroccurrenceof anewsymptomin443,andoccurrence

of an “alarm” symptomin48.527 patientsunderwent a

sec-ondCTCincludingprogrammedscreeningtestsin287,newor

Included N=7361 N= 6458 (87.7%) N= 903 (12.3%) VC - VC + Comparison to OC/surgery/repeat VC N=1198 (18.5%) Comparison to OC/surgery/repeat VC N= 692 (76.6%) True negative: 1193 (99.6%) False positive: 55 (7.9%) True positive: 637 (92.1%) Missed N= 211 (23.4%) False negative : 5 (0.4%) Unverified N= 5260 (81.5%)

Table1

HistopathologyandcausesofconfirmedCTCfindingsin642patients. Causesoffindings Confirmed

findings(N=642)

% 95%CI

Tumorsandpolyps

Adenocarcinoma 97* 15.10 0.12–0.18 Carcinoidtumor 1 0.15 NA Gastrointestinalstromal tumor 1 0.15 NA Peritonealmetastasis 1 0.15 NA Bladdercancerinfiltration 1 0.15 NA

Villous 11 1.71 0.01–0.03 Tubulovillous 69 10.75 0.08–0.13 Tubular 70** 10.90 0.08–0.14 Hyperplasic 35** 5.45 0.04–0.07 Hamartomatous 1 0.15 NA Fibrolipoma 1 0.15 NA Lipoma 4 0.62 0.00–0.01 Post-hemorrhoidscar 1 0.15 NA Others Diverticulitis 24 3.73 0.02–0.05 Ischemia 7 1.09 0.00–0.02 Endometriosis 7 1.09 0.00–0.02 Non-specificcolitis 1 0.15 NA Post-radiationcolitis 1 0.15 NA Leiomyoma 1 0.15 NA

Unknown(notrecovered foranalysis)

308 48.0 0.44–0.52

* Including3virtualcolonoscopyfalse-negative. ** Including1virtualcolonoscopyfalse-negative.

exacerbated “non alarm symptoms in 216 and“alarm

symp-toms” in 24. Twelve patients (all in group B) had surgical

resectionafteracutediverticulitis.

Fivepatientswerefalse-negative(2with>6mmpolypsand 3withcancers).Allcontrolledcases,yielda637/642(99.2%,

95%CI0.98–0.99)true-positivefractionanda55/692(7.95%,

95%CI0.05–0.09)false-positivefraction.

Theaveragenumberofsymptomsperpatientwas1.54±0.35 (3800,1524,662,29and3patientshadrespectively1,2,3,4and

5symptoms).Abdominalpainandconstipationwerethemost

frequent,whileunexplainedweightlosswastheleastfrequent

symptom.GroupsA,BandCincludedrespectively1343,5329

and689patients;theirdemographiccharacteristicsaregivenin

Table2.TheaverageageingroupC(64.37±14.61years)was significantlyhigherthaninbothgroupsA(60.96±11.22years) andB(59.43±14.31years)(p<0.001).Themale/femaleratio wasloweringroupB(0.63)versusgroupA(1.03)(p<0.001). TherateofE4findingsintheC-RADreportingsystemwas

sig-nificantlyhigheringroupC(44/689,6.4%,95%CI0.04–0.08)

versus groups A (26/1343, 1.9%, 95%CI 0.01–0.03) and B

(64/5329,1.2%,95%CI0.01–0.02)(p<0.001).Theregression

analysis showed that the group of symptom (B<C), gender

(F<M)andageallsignificantlyimpactedthetest-positiverateat CTC.Whenpoolingpatientsbyagegroups(Table3),the

test-positiverate ingroupC (138/689,20.0%, 95%CI 0.17–0.23)

was significantly higher than in groups A (79/1343, 5.8%,

95%CI0.04–0.07)andB(420/5329,7.8%,95%CI0.07–0.08)

(p<0.001),then, acrossall ages, exceptfor patients younger

than 50 years of age whose test-positive rate in groups C,

A andBwere respectively(6/96, 6.25%, 95%CI 0.01–0.11),

(5/173,2.9%,95%CI0.00–0.05)and(47/1241,3.8%,95%CI

0.02–0.04) (p=0.412). Diagnostic values of CTC within the

threegroupsaregiveninTable4.Boththetrue-positive frac-tionthatwasconsistentlyabove97%inallgroups(p=0.991) andthe false-positivefractiondid nodifferamongallgroups (p=0.240).

4. Discussion

In a recent meta-analysis evaluating the value of various

symptomsforCRCinprimarycare,Jellemaetal.foundlarge

heterogeneitiesinthesensitivityandspecificityofmost

symp-toms [6]. Rectal bleeding and unexplained weight loss have

consistently higher specificity than the others, according to

another recent meta-analysis [5]. Similarly to studies using

OC, the test-positive rate at CTC inour study washigher in

patientswiththese“alarm”symptomsthaninasymptomatic sub-jectsandthosewithminorgastrointestinalsymptoms(p<0.05).

Although theaverageagewasalsosignificantlyhigher inthe

“alarm”symptomsgroup(p<0.05),agewasnotakey determi-nant,sincesimilardifferenceswereobservedinallagegroups

above 50 years. In terms of CRC diagnostic

recommenda-tions,atest-positiveratearound20%makesOCtheprocedure

of choice in patients with “alarm” symptoms, owing to the

high resection-rate. An exceptionto thisrule, though requir-ingstrongerevidence,maybepatientsagedlessthan50years.

Theirfindingsprevalencewas6/96(6.25%;95%CI0.01–0.11),

i.e.:higherthaninage-matchedpatients,butcomparabletothe overallprevalenceintheothergroups.

Duetothelowspecificityoftheremaininggastrointestinal

symptoms (alone or in combination), diagnostic

recommen-dations currently fails to avoid OC facilities congestion by

proceduresyieldinglowratesofresection[9–11,22,23].

Excep-tion made of melena and hemorrhoids, the “non-alarm”

symptoms evaluated in this study are commonly described

in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) which is a

functionalboweldisorderaffecting7–15%ofthegeneral

pop-ulationin the USA,women being twice more oftenafflicted

thanmen[24,25].Itsdiagnosisnicelyillustratesthedichotomy

between the daily management of gastrointestinal symptoms

and evidence-baseddiagnostic recommendations. Indeed, the

diagnosisof IBSisbasedexclusivelyonclinicalcriteria[26],

but, up to 75% of clinicians believe that it should be

ascer-tainedbyexclusionof organicdisease [27].Forthispurpose,

approximately half of the patients with known or suspected

IBShaveundergoneatleastonediagnosticOCprocedure[28].

Lastly, it hasbeen estimated that 25% of the OCprocedures

performed inthe USAarefor patientswith“non-alarm”

gas-trointestinalsymptoms,althoughtheactualriskofCRCinthese patientsisnothigherthaninasymptomaticindividualsin sev-eralstudiesreportingvery closerangesoftest-positive rateat

OCamongIBS(range1.9–9.3%)andasymptomaticindividuals

(range4.5–12.1%)[29,30].Severalreasonscouldbeadvocated forthisdichotomy,includingphysiciansandpatient’sanxiety,

Table2

Patientgroupsdemographics.

Age±SD(years) Agerange(years) Sexratio C-RADreportingclassification

C0 C1 C2 C3 C4 E4 GroupA (N=1343) 60.96±11.22 21–91 683M/660F(1.03) 11 1179 (87%) 58 (4%) 55 (4%) 40 (3%) 26 (2%) GroupB (N=5329) 59.43±14.31 18–96 1975M/3144F(0.63) 21 4587 (86%) 269 (5%) 287 (5%) 165 (3%) 64 (1%) GroupC (N=689) 64.37±14.61 20–95 318M/371F(0.86) 0 594 (86%) 34 (5%) 38 (5%) 23 (3%) 44 (6%) p-value <0.0001* NA <0.0001** NA 0.906 0.573 0.174 0.916 <0.001*

* Significantlyhigher(p<0.05)ingroupCversusgroupBandgroupCversusgroupA. **TheproportionofmalesissignificantlyhigheringroupAversusgroupB(p<0.0001).

NA=notapplicable.

C-RADreportinganddatasystem.

• C0=inadequatestudy.

• C1=normalcolon/benignlesion.

• C2=polyps6–9mmindiameteror<3innumber.

• C3=polyp>10mmindiameteror>3polypswitheach6–9mm. E4=potentiallyimportantfinding:communicatetoreferringphysician.

symptomsseverityandthelackofevidencethatotherdiagnostic proceduresmaybeasaccurateorcost-effectivethanOC.

Toourknowledge,ourstudy isthefirstevaluatingcolonic

findings according to gastrointestinal symptoms using CTC.

Thiswaspossibleas,since2002,CTChasprogressivelybecome

aroutine procedurein ourinstitution, acknowledgedboth by

ourgastroenterologists,generalpractitionersandpatients.The

ranges of test-positive rate in asymptomatic individuals and

those with“non-alarm”symptoms werelow andcomparable

to thosereported using OC. In bothgroups, the test-positive

rate increased roughly linearly with aging (p<0.05). Given theirrelativelylowtest-positiverate,patientswith“non-alarm”

Table3

CTCtest-positiveratebyageinallgroups.

Age(years) GroupA GroupB GroupC Total p-value*

<50 5/173 47/1241 6/96 58/1510 0.412

(2.89%) (3.78%) (6.25%) (3.84%)

95%CI 95%CI 95%CI 95%CI

0.00–0.05 0.02–0.04 0.01–0.11 0.02–0.0.5

50–59 23/441 91/1362 22/159 136/1962(6.93%) 0.003*

(5.21%) (6.68%) (13.83%) 95%CI

95%CI 95%CI 95%CI 0.05–0.08

0.03–0.07 0.05–0.08 0.08–0.19

60–69 30/420 107/1251 42/151 179/1822(9.82%) <0.0001*

(7.14%) (8.55%) (27.81%) 95%CI

95%CI 95%CI 95%CI 0.08–0.11

0.04–0.09 0.07–0.10 0.21–0.35

70–79 14/244 134/1077 42/180 190/1501(12.65%) <0.0001*

(5.73%) (12.44%) (23.33%) 95%CI

95%CI 95%CI 95%CI 0.10–0.14

0.02–0.08 0.10–0.14 0.17–0.29

>80 7/65 41/398 26/103 74/566(13.07%) 0.003**

(10.77%) (10.30%) (25.24%) 95%CI

95%CI 95%CI 95%CI 0.10–0.16

0.03–0.18 0.07–0.13 0.17–0.33

Total 79/1343 420/5329 138/689 637/7361 <0.0001*

(5.88%) (7.88%) (20.02%) (8.65%)

95%CI 95%CI 95%CI 95%CI

0.04–0.07 0.07–0.08 0.17–0.23 0.08–0.09

p-value 0.176 <0.0001 =0.002 <0.0001 NA

* SignificantdifferencebetweengroupCversusgroupsAandB. **SignificantdifferencebetweengroupCversusgroupsB.

Table4

DiagnosticvaluesofCTCversusOCand/orsurgeryingroupsA,BandC. Abbreviationsasinthetext.

True-positivefraction False-positivefraction GroupA 79/79(100%) (95%CI=NA) 10/89(11%) (95%CI0.04–0.17) GroupB 420/422(99.5%) (95%CI0.98–1.00) 38/458(8%) (95%CI0.05–0.11) GroupC 138/141(97.9%) (95%CI0.95–1.00) 7/145(5%) (95%CI0.01–0.08) p-value 0.991 0.240

symptoms may indeed benefit from accurate noninvasive

diagnosticprocedures.Inourseriesof5329patientswith

“non-alarm” symptoms, 4088 were older than 50 years of age: it

maythusbeemphasizedthatthesesymptoms werean

incen-tivetocomplywithscreeningguidelines andshouldtherefore

becarefullysought.Althoughpatientsunder50yearsofageand

suspectedofIBSshouldnotundergoanycolonicexploration,

manyof themunfortunatelydoinmostinstitutions,including

ours.Inourseries,thismalpracticeappliesto1241patients(23%

referredbygastroenterologists)forwhomCTChasalow

test-positiverateingoodcorrelationwithotherseries,butrepresent themostcomprehensiveandthelessharmfuloptionascompared toOC,thestandardofreference.

Inthissetting,ourstudyconfirmedthatCTChasahigh true-positivefractionandalowfalse-positivefractionforpolypsand CRCinallgroups[15,31]clearlyadvocatingforits recommen-dationinpatientswith“non-alarm”gastrointestinalsymptoms.

Consideringtherecommendationsguidelines forCRC,the

main disadvantage of CTC, namely the inability to perform

polypectomy,mayraisecost-effectivenessissues.Inourstudy,at least420additionalOCwereperformedinthegroupofpatients

with“non-alarm”symptoms,whileapproximately5000

poten-tialdiagnosticOCprocedureswerereplacedbylessexpensive

CTCprocedures,puttingobviouslythecost-effectiveness

bal-anceinfavorofaprimarydiagnosticprocedurebyCTCinour

institution.In addition,offeringasame-dayOCafter positive

CTCscenario currently prevent the needfor asecond bowel

preparationinmostinstitutions includingours[32].The abil-ityto detect clinicallysignificant extra-colonic abnormalities

(E4)mayalsoimpactCTCcost-effectiveness.Atotalnumber

of 134 individuals hadE4findings, whichrepresentan asset

forCTC.Interestingly,therateofE4findingsdistributionper group was quite similar to the test-positive rate distribution, prevailingthus in olderpatients. Thisindicates that E4 find-ingsratearenoteitherincreasedbynonspecificgastrointestinal symptoms.Lastly,theconcernofexposuretoionizingradiation

during CTC,has dropped significantly with the latest

gener-ationof scanners [33]. In our institution, the combined dose

forsupine andproneacquisitions of anaverage-sizedsubject

isapproximately3mSv (i.e.: levelscomparabletotheannual

environmentalscatterdoses).

Somelimitationsmaybeappliedtothisstudyandits conclu-sions,thefirstofwhichisitsretrospectivenaturethatresulted intoseveralpatientslosttofollow-upandclinicaldatamissing.

Histopathologicaldatawerealsomissinginseveralpatientfrom

mis-retrievedpolypectomiesthatare,however,notuncommon

[33].Reportedsymptomswerenotbasedonachecklistofall

gastrointestinalsymptoms.Thesamedesignforcedustopool

symptomsintwogroups,resultingintopotentialmaskingofthe effectofoneorseveralunderrepresentedindividualsymptom(s) ontheCTCtest-positiverate.Moreover,ageofsymptomsonset, theirintensityanddurationlacked,preventingabetterdetailed relationshipbetweensymptomsandtest-positiverate.Reported

diagnosticvaluesofCTC,thoughcomparablewithpreviously

reportedstudies,aresubjecttoverificationbias,sinceOCwas

mostlyperformed when CTC waspositive. In addition, most

oftheunverifiedCTCpositivecasesweresmallpolyps,which

probably decreased artificially the false-positive rate. Lastly, patientswithatleastonegastrointestinalsymptomlargely

out-numberedasymptomaticsubjectsinourstudy,with6929outof

the7361average-risksubjectsforCRChavingatleastone

symp-tom. Thisselection biaswas causedbyaprogressive referral

replacementofDCBEbyCTCduringthestudyperiod.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, asymptomaticsubjects, patients with

“non-alarm” gastrointestinal symptoms and even young patients

with “alarm” symptoms for CRC have nearly similarly low

test-positive rates at CTC. Overall, the rate of colonic and

extra-colonicfindingsincreasedwithage,malegenderandthe

presence of“alarm” symptomsfor CRC.The highdiagnostic

valueofCTCinallpatientgroupsmakesittheexaminationof choiceinlow-yieldpatients;whoincludeasymptomaticsubjects

andthosewith“non-alarm”gastrointestinalsymptoms.

Conflictofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarethatthereisnoconflictofinterest.

References

[1]FerlayJ,Steliarova-FoucherE,Lortet-TieulentJ,RossoS,CoeberghJW, ComberH,etal.CancerincidenceandmortalitypatternsinEurope: esti-matesfor40countriesin2012.EurJCancer2013;49(6):1374–403.

[2]LevinB,LiebermanDA,McFarlandB,SmithRA,BrooksD,AndrewsKS, etal.Screeningandsurveillancefortheearlydetectionofcolorectalcancer andadenomatouspolyps,2008:ajointguidelinefromtheAmericanCancer Society,theUSMulti-SocietyTaskForceonColorectalCancer,andthe AmericanCollegeofRadiology.CACancerJClin2008;58(3):130–60.

[3]McFarlandEG,LevinB,LiebermanDA,PickhardtPJ,JohnsonCD,Glick SN,etal.Revisedcolorectalscreeningguidelines:jointeffortofthe Amer-icanCancerSociety,U.S.MultisocietyTaskForceonColorectalCancer, andAmericanCollegeofRadiology.Radiology2008;248(3):717–20.

[4]ArditiC, Peytremann-BridevauxI, BurnandB, EckardtVF, BytzerP, AgreusL,etal.AppropriatenessofcolonoscopyinEurope(EPAGEII). Screeningforcolorectalcancer.Endoscopy2009;41(3):200–8.

[5]AdelsteinBA,MacaskillP,ChanSF,KatelarisPH,IrwigL.Mostbowel cancersymptomsdonotindicatecolorectalcancerandpolyps:asystematic review.BMCGastroenterol2011;11:65.

[6]JellemaP,vanderWindtDA,BruinvelsDJ,MallenCD,vanWeyenberg SJ,MulderCJ,etal.Valueofsymptomsandadditionaldiagnostictests forcolorectalcancerinprimarycare:systematicreviewandmeta-analysis. BMJ2010;340:c1269.

[7]LiebermanDA,WilliamsJL,HolubJL,MorrisCD,LoganJR,EisenGM, etal.Colonoscopyutilizationandoutcomes2000to2011.Gastrointest Endosc2014;80(1):133–43.

[8]AstinM,GriffinT,NealRD,RoseP,HamiltonW.Thediagnosticvalueof symptomsforcolorectalcancerinprimarycare:asystematicreview.BrJ GenPract2011;61(586):e231–43.

[9]RexDK,LiebermanDA.Feasibilityofcolonoscopyscreening:discussion ofissuesandrecommendationsregardingimplementation.Gastrointest Endosc2001;54(5):662–7.

[10]Hoffman RM, Espey D, Rhyne RL. A public-health perspective on screeningcolonoscopy.ExpertRevAnticancerTher2011;11(4):561–9.

[11]LevinTR.Colonoscopycapacity:canwebuildit?Willtheycome? Gas-troenterology2004;127(6):1841–4.

[12]ShapiroJA,SeeffLC,ThompsonTD,NadelMR,KlabundeCN,Vernon SW.Colorectalcancertestusefromthe2005NationalHealthInterview Survey.CancerEpidemiolBiomarkersPrev2008;17(7):1623–30.

[13]Halligan S,Wooldrage K,Dadswell E, Kralj-Hans I, vonWagner C, EdwardsR,etal.Computedtomographic colonographyversus barium enema for diagnosis of colorectal cancer or large polyps in symp-tomatic patients (SIGGAR): a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2013;381(9873):1185–93.

[14]Atkin W, Dadswell E, Wooldrage K, Kralj-Hans I, von Wagner C, Edwards R, et al. Computed tomographic colonography versus colonoscopyforinvestigationofpatientswith symptomssuggestiveof colorectal cancer (SIGGAR): a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2013;381(9873):1194–202.

[15]PickhardtPJ,ChoiJR,HwangI,ButlerJA,PuckettML,HildebrandtHA, etal.Computedtomographicvirtualcolonoscopytoscreenfor colorec-talneoplasiainasymptomaticadults.NEnglJMed2003;349(23):2191– 200.

[16]JohnsonCD,MacCartyRL,WelchTJ,WilsonLA,HarmsenWS,Ilstrup DM,etal.ComparisonoftherelativesensitivityofCTcolonographyand double-contrastbariumenemaforscreendetectionofcolorectalpolyps. ClinGastroenterolHepatol2004;2(4):314–21.

[17]SosnaJ,Bar-ZivJ,LibsonE,EligulashviliM,BlacharA.Criticalanalysis oftheperformanceofdouble-contrastbariumenemafordetecting colorec-talpolyps≥6mmintheeraofCTcolonography.AJRAmJRoentgenol 2008;190(2):374–85.

[18]Summariesforpatients.Screeningforcolorectalcancer:recommendations fromtheUnitedStatesPreventiveServicesTaskForce.AnnInternMed 2002;137(2):I38.

[19]HockD,OuhadiR,MaterneR,AouchriaAS,ManciniI,BroussaudT, etal.VirtualdissectionCTcolonography:evaluationoflearningcurves andreadingtimeswithandwithoutcomputer-aideddetection.Radiology 2008;248(3):860–8.

[20]ZalisME,BarishMA,ChoiJR,DachmanAH,FenlonHM,FerrucciJT, etal.CTcolonographyreportinganddatasystem:aconsensusproposal. Radiology2005;236(1):3–9.

[21]deVriesAH,BipatS,DekkerE,LiedenbaumMH,FlorieJ,FockensP, etal.PolypmeasurementbasedonCTcolonographyandcolonoscopy: variabilityandsystematicdifferences.EurRadiol2010;20(6):1404–13.

[22]BrownML,KlabundeCN,MysliwiecP.Currentcapacityforendoscopic colorectalcancerscreeningintheUnitedStates:datafromtheNational CancerInstituteSurveyofColorectalCancerScreeningPractices.AmJ Med2003;115(2):129–33.

[23]Seeff LC, Manninen DL, DongFB, Chattopadhyay SK, NadelMR, TangkaFK,etal.Isthereendoscopiccapacitytoprovidecolorectalcancer screeningtotheunscreenedpopulationintheUnitedStates? Gastroenter-ology2004;127(6):1661–9.

[24]MeleineM,MatriconJ.Gender-relateddifferencesinirritablebowel syn-drome:potentialmechanismsof sexhormones.WorldJGastroenterol 2014;20(22):6725–43.

[25]KhanS,ChangL.DiagnosisandmanagementofIBS.NatRev Gastroen-terolHepatol2010;7(10):565–81.

[26]LongstrethGF,ThompsonWG,CheyWD,HoughtonLA,MearinF,Spiller RC.Functionalboweldisorders.Gastroenterology2006;130(5):1480–91.

[27]Spiegel BM, Farid M, Esrailian E, Talley J, Chang L. Is irritable bowelsyndrome a diagnosis of exclusion?: a surveyof primarycare providers, gastroenterologists, and IBS experts. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105(4):848–58.

[28]Talley NJ, Boyce P, Owen BK. Psychological distress and seasonal symptom changes in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90(12):2115–9.

[29]LiebermanDA,HolubJ,EisenG,KraemerD,MorrisCD.Prevalenceof polypsgreaterthan9mminaconsortiumofdiverseclinicalpractice sett-ingsintheUnitedStates.ClinGastroenterolHepatol2005;3(8):798–805.

[30]CashBD,Schoenfeld P, CheyWD. Theutilityof diagnostic tests in irritablebowelsyndromepatients:asystematicreview.AmJGastroenterol 2002;97(11):2812–9.

[31]JohnsonCD,ChenMH,ToledanoAY,HeikenJP,DachmanA,KuoMD, etal.AccuracyofCTcolonographyfordetectionoflargeadenomasand cancers.NEnglJMed2008;359(12):1207–17.

[32]PickhardtPJ,TaylorAJ,KimDH,ReichelderferM,GopalDV,PfauPR. ScreeningforcolorectalneoplasiawithCTcolonography:initial expe-riencefromthe1styearofcoveragebythird-partypayers.Radiology 2006;241(2):417–25.

[33]BerringtondeGonzalezA,KimKP,KnudsenAB,Lansdorp-VogelaarI, RutterCM,Smith-BindmanR,etal.Radiation-relatedcancerrisksfrom CTcolonographyscreening:arisk-benefitanalysis.AJRAmJRoentgenol 2011;196(4):816–23.