A DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND EVALUATION: CONSTITUTION AVENUE SITE IN CHARLESTOWN

by

C. David Carlson

Bachelor of Environmental Design University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota 1974 Bachelor of Architecture University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota 1977

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 1986

C. David Carlson 1986

The Author hereby grants to M.I.T.

permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Signature of the Author

O. davdCarlson Department of Architecture August 15, 1986 Certified by Accepted by James McKellar Professor of Architecture and Planning Thesis Supeyvisor \ss. msT. rec . James McKellar Chairman Interdepartmental Degree Program

ST. in Real Estate Development

A DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND EVALUATION: CONSTITUTION AVENUE SITE IN CHARLESTOWN

by

C. David Carlson

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate the

feasibility of the redevelopment of a waterfront site in Charlestown. The site is the only remaining underdeveloped waterfront site on Boston harbor between the Charlestown Navy Yard and the Fan Piers in South Boston. Because the

site has been on the market for almost eighteen months, it was suspected that the seller was asking more than the property is worth. However, the owner recently signed a

creative agreement, to sell the property for an attractive price to a prospective developer, provided the owner will

share some of the development risk.

The focus of the study is to first understand the potential risks and rewards inherent in the redevelopment. Next, it evaluates the risks and their effect on the

seller's interests. Finally, it suggests strategies the seller may use to manage the risks and protect his

interests.

The conclusion drawn from this study is that many deal structures are not as simple as the may first appear. The motivations of each participant may be vastly different from

the other. In addition, the analysis demonstrates that it is unlikely this development will proceed according to the prospective developer's plan, and opportunities will arise to renegotiate the initial agreement. Therefore, the

management of that ongoing relationship will be as important as the initial deal structure.

Thesis Supervisor: James McKellar

Title: Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development

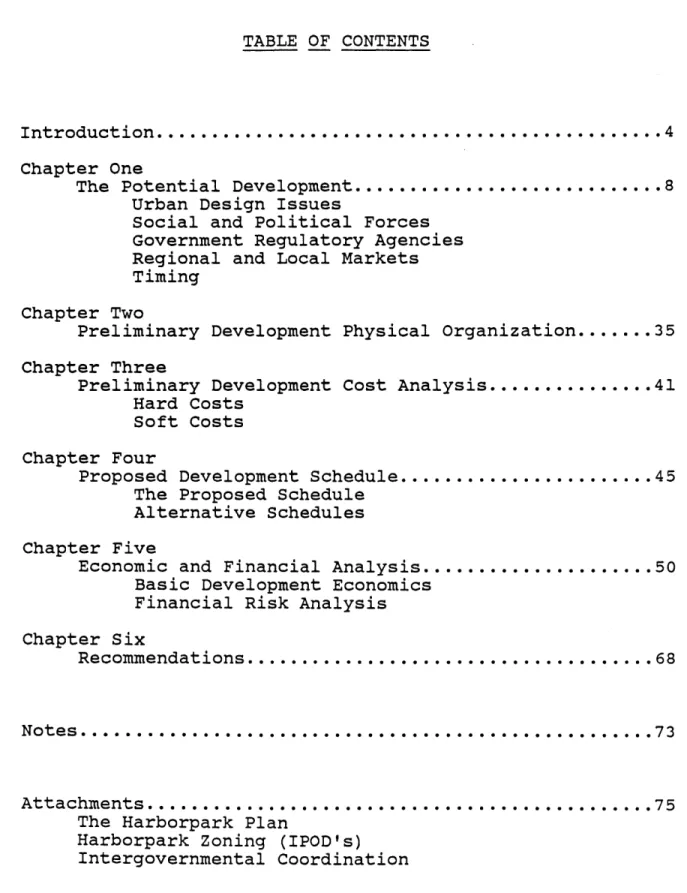

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction...4 Chapter One

The Potential Development...8 Urban Design Issues

Social and Political Forces Government Regulatory Agencies Regional and Local Markets Timing

Chapter Two

Preliminary Development Physical Organization...35 Chapter Three

Preliminary Development Cost Analysis...41 Hard Costs

Soft Costs Chapter Four

Proposed Development Schedule...45 The Proposed Schedule

Alternative Schedules Chapter Five

Economic and Financial Analysis.. Basic Development Economics Financial Risk Analysis Chapter Six Recommendations... Notes... Attachments... ... ... .. 50 .. 68 ... ... 73 ... ... 75

The Harborpark Plan

INTRODUCTION

"When Rapids Furiniture Co. moved out of its 90 Canal Street headquarters after doing business there for 70 years, it represented another step in the changing nature of the North Station area. The neighborhood had long been

dominated by the furniture industry, and the move by Rapids, the last of the major furniture outlets, was the end of an era. In the past five years the area has been gaining

strength as one of the city's newest office centers."1 The decline of the North End furniture businesses also directly affected other properties in nearby communities

such as Wharf Number 3 in nearby Charlestown.

Wharf Number 3 and its buildings have long been used by the Rapids Furniture Company as a warehouse for storing

furniture and as a distribution base. The decline in the North End furniture industry and the close of Rapids

showroom greatly reduced this property's value as a furniture warehouse. At the same time, the Boston real estate market experienced dramatic expansionary moves

providing enormous opportunities and profits for land owners surrounding the rapidly expanding downtown financial

district. In addition, recent redevelopment efforts have taken place in the Charlestown Navy Yard, expansion of the National Historic Park at Constitution Wharf, and an

enormous volume of housing redevelopment has occured in Charlestown itself. This situation convinced the owners of Wharf Number 3 that perhaps furniture warehousing may not be the highest and best use for their property and they might realize substantial gain by selling this property to someone with real estate development experience. Consequently, the property was listed with the firm of Peter Elliot and

Company, an established Boston real estate broker with

extensive experience in commercial and industrial property.

The property remained on the market considerably longer than most observers envisioned. It has been suggested that perhaps the asking price of 2.5 million dollars was a bit high, or that either the Boston Redevelopment Authority or Massachusetts regulatory agencies impose development

restrictions that limit what can be built and make

redevelopment of the property too risky for most developers to consider purchacing the property. Further, it was

suggested that perhaps the owner was unwilling to structure the sale in such a manner so as to share in some of the risks inherent in Boston's lengthy approval process. This speculation has recently ended when it was announced that a developer has signed an agreement with the property owner to purchace the property in two years for 4.5 million dollars.

It is now assumed that the developer is willing to pay more than 2.5 million for the property because he has

approval processes before closing on the property, therby reducing his exposure and risk. It is also assumed that the seller is willing to wait for two years before realizing substantial gain from the property, because at that time he will receive considerably more money. In fact, the

increased sale price represents an anualized return on the seller's $2,500,000 investment of almost 35%.

It may appear that this arrangement has a number of potential advantages to both buyer and seller. However, the situation is not as simple as it appears and the advantages will not be realized without significant risk to the seller. For example, the buyer may simply interested in realizing

appreciation in a rapidly inflaying real estate market with alot of speculation by selling his agreement, rather than developing the site. Or, he may tie up the property for two years only to discover that his proposed development is not allowed, that it is allowed but doesn't generate as much value as projected, that market forces will not support proposed uses at the assumed rates, or that unforseen construction or infrastructure costs have excceded

expectations. At this point he will be in a very favorable barganning position to re-negotiate the sales price and terms in a way which benefits him and certainly not the seller. If he cannot sell his option or renegotiate the deal to his

satisfaction, he may walk away from the deal leaving only his small deposit.

This paper examines the various risks and rewards inherent in this deal structure, indicates measures the seller should take to understand and manage these risks, protect his interests, and under what conditions he should consider using the contingencies, built into his agreement with the buyer, to terminate the agreement and renegotiate with another potential developer.

CHAPTER ONE

THE POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT

It is important, to both the buyer and seller of the Wharf Number 3 property, that the development proposal presented to the appropriate public agencies is indeed the highest and best use of the site. In order to understand what is the best use, it will be necessary to examine the proposed development from a number of different points of view.

For example, an urban design point of view will show us how the site fits in to the surrounding environment and how surrounding uses, amenities and nusances will affect the development uses and location of those uses within the

site. Second, an understanding of the social and political structure of the community will help us understand the

concerns of the neighbors and the power they have to influence the development. Third, an examination of the appropriate government regulatory agencies controls and powers will show us how they control the development uses and development schedule. Fourth, regional and local market

forces will have a great deal of affect on the uses

scheduled for the development and the proportions of those uses. Finally, an understanding of how these forces are expected to change, over time, is essential in selecting the

most appropriate uses for a development that cannot be completed for a number of years.

URBAN DESIGN ISSUES

From an urban design point of view, The site has the potential to be extremely well located. See Exhibit 1,

Wharf Number 3 Location. It lies immediately adjacent to the Charlestown bridge, directly in the path of all

pedestrian traffic between downtown Boston and the new housing development in Charlestown, the Charlestown Navy Yard redevelopment and the National historic Park at

EXHIBIT 1

On a typical week day, more than 1,000 people walk by the site on their way to and from work and, according to the Boston Globe Extra Index, an additional 1,000 tourists visit the nearby Constitution Wharf. On weekends, an estimated 5,000 tourists visit Charlestown and Constitution Wharf each day. As the present renovation and construction activity in Charlestown and at the Charlestown Navy yard continues, the population in these areas will continue to increase,

exposing the site to even more pedestrian traffic.

The site is also located in a position that is readily visible from the Charlestown bridge, Boston's north end and Boston harbor. By the same token there are excellent views of the Boston Harbor from the south and east sides of the site which overlook the Constitution Wharf Marina.

Unfortunately, the buildings that occupy space on Wharf Number 3 are of recent, utilitarian, concrete block

warehouse design, and contribute little to the historic nature of the site. Thus, the most appropriate building form may be new construction that echos the character and environment of Charlestown, yet provides for the functional requirements of today's uses.

EXHIBIT 2

WHARF NUMBER 3 SURROUNDINGS

Because the site's present use, warehousing, makes little use of this pedestrian traffic and these amenities, access to the site is not pleasant. At present, access

consists primarily of service roads more suitable to heavy trucks than to pedestrians. However, according to Jim English, Director of Design and Development: Boston

Harborpark, the Harborpark plan will require development of amenable pedestrian access along the waterfront through this site.2

In addition, the state highway construction project, beginning in late 1986, will depress the existing overhead expressway shadowing nearby City Square, and is expected to be completed by 1991. This highway construction will open City Square to extensive redevelopment, creating a

comfortable and friendly approach to Charlestown and Wharf Number 3. Also, plans for expanding the Boston harbor water ferry network will make the site more attractive and accessable. Ferries will dock at nearby Constitution Wharf and will go to the north shore, Logan Airport, the financial district, the Fan Pier development, South Boston and the south shore.

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL FORCES

The social and political forces in the community

surrounding Wharf Number 3 are undergoing enormous change. "Charlestown was recognized as a good residential area at the turn of the century, but between 1930 and 1980 the population declined to only 50% of its former level. This decline in population was largly due to encroachment of industry and unsightly transportation facilities. (the elevated "T")." 3 "By 1963, a six room house in

Charlestown would sell for only $4,000 and a townhouse mansion on Monument Square would sell for $12,000. That year, the BRA developed urban renewal plans to help blight by building new parks, schools, removing the elevated "T", and building new subsidized housing in the worst parts of town." 4

Recent economic growth of Boston's financial and service businesses have fueled residential redevelopment and

associated gentrification in many of the historic

communities surrounding the downtown financial district

including Charlestown. Thus, the number of new residents in Charlestown appear to outnumber the existing former

residents. This rapid change has created an understandable concern by the present residents about any further change.

This concern has not, at least yet, been directed

toward potential development at Wharf Number 3. Because the site is on the waterfront, separated from the rest of

Charlestown by active Constitution Avenue, the elevated expressways, and the deserted City Square, it has been overlooked in many of the Charlestown planning studies and by many of the neighborhood groups. However, once the

overhead expressways are depressed, Wharf Number 3 will become an important element of the City Square

re-development, and will present a visitor who crosses the bridge into Charlestown with his first impression of the city.

One political or community force that does express interest in the site is the group led by Father David

Murphy, pastor of St. Peter and Paul's/St. Vincent Church. His group is interested in maintaining waterfront locations

for traditional water related industries, therby maintaining water related employment opportunities in Boston. This group has the expressed public support of Mayor Flynn, who has long standing ties and commitments to the South Boston maritime industry. Even though the present warehouse use of Wharf Number 3 does not take advantage of its waterfront location, and employs no people who's job could be classified as water related, these groups may be interested in maintaining the present waterfront industrial zoning out of principle. This group has had a great deal of influence on the Harborpark

Charlestown waterfront properties such as the Revere Sugar plant redevelopment, and the Pier-4 and Fan Pier

developments in South Boston. Therefore a strategy for for incorporating and dealing with their concerns must be included in any development proposal for this site.

GOVERNMENT REGULATORY AGENCIES

Government regulatory agencies are another story. There are almost fifty different city, state and federal

agencies that must review an approve development along the Boston waterfront. These include the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), the Civic Advisory Committee, the

Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA), Chapter 91 (the Tidelands Licensing Statute), The Executive office of Transportation and Construction, the Office of Coastal Zone Management and the state Inter-Agency Coordinating

Committee. In additon, permits are required from the US Army Corps of Engineers, the US Fish and Wildlife Agency,

the Bureau of National Marine Fisheries, the US

Environmental Protection Agency, the State Department of Environmental Quality Engineering and Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, the City Conservation Commission and the Boston Harbormaster.

Recently, the Boston Harborpark overlay district was created to provide unified design control and guidelines for

all development along the water's edge. In October of 1984, the BRA established interm planning zones to prevent

unwanted development in these areas. The zones create

overlay districts (IPOD's), suspend existing zoning, exclude certain uses, and force developers to obtain case-by-case approvals. The BRA has attempted to streamline the approval processes for development within this district.5

According to Stephen Coyle, BRA Director, "Permits should be concurent, not consecutive." Further, he says "Everybody has the right to do their review, but there should be a limited number of evidentiary hearings."6 Even in its streamlined form, the approval process for a development on this site is expected, by Jim English, to take at least eighteen months.

The site's zoning, at present, is W-2 or Waterfront Industrial. Representatives of the BRA have indicated that redevelopment of the site for other uses will simply require rezoning. However, the BRA's development restrictions, as set out in the Harborpark planning documents, for this site are quite specific. First, new buildings cannot be higher than two stories. However, Jim English indicated that in other similar developments the requirement had been ammended to allow "buildings no higher than surrounding buildings."7

At this site, the nearest buildings are the Barretts

Second, parking for the site's uses must be developed within the site. The exact number of required spaces however, is unclear and may be the product of some

negotiation. Most likely, one space will be required for each condominium unit and two spaces for each 1,000 sf of commercial space.

Third, as part of the Harborpark overlay district, open and unrestricted public access to the waterfront side of the development must be provided according to the Harborpark guidelines. In addition, continuous pedestrian access must be provided across this site connecting the Charlestown

bridge pedestrian walkway to the Harborwalk system now under construction at Hoosac Pier, Constitution Wharf and The Charlestown Navy Yard.

Finally, the Harborpark planning documents say that in the Charlestown Waterfront area, "no structure other than those which facilitate public access and recreation, or which are necessary for water-dependent and maritime uses, should be built at the water's edge."8 It was indicated by BRA officials that on this particular site, a great number of uses may be considered to facilitate public access and recreation, while in other more industrial areas, specific guidelines may be enforced more strongly.

Based on this potential zoning, and assuming Charles River Avenue can be vacated within the site limits, the developable area on the site is as indicated on the

A

V(1)

V rd . 4 N 9 rI 0 44 ME-4 H C) M W 0Eni

cvm H M~1EXHIBIT 4

POTENTIAL SITE DEVELOPMENT FLOOR AREAS

FOR BOTH HOUSING AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT

TOTAL SITE AREA

Developable site area Harborwalk site area Maximum Gross building area

(assume 5 floors)

76,000 sf 53,000 sf 23,000 sf 265,000 sf

HOUSING DEVELOPMENT (if developed only as housing)

Parking area: 200 cars * 350 sf (Housing at 1 space/ 1000 sf) Gross saleable or rentable area

T

70,000 sf

195,000 sf OTAL 265,000 sf

COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT (if developed only as commercial)

Parking area: 350 cars * 350 sf (commercial at 2 spaces/ 1000sf) Gross saleable or rentable area

TOT

112,000 sf

153,000 sf AL 265,000 sf

REGIONAL AND LOCAL MARKET FORCES

Regional and local market forces will have a dramatic influence on both the mix of uses developed on this site and the profitability of those uses. It is understood that the buyer of the site intends to develop the site largely as housing. One must ask the question that if the site has the

opportunity to be intensely used by pedestrian traffic,

should not the mix of uses be more directed toward uses that benefit from high levels of pedestrian traffic, great

visability and harbor views.

On the other hand, there appears to be an extreme shortage of housing in the Boston area. That shortage of supply is creating a demand that is driving local housing prices to the highest of any city in the nation. At todays sales prices, the returns to the land from intensive

development of housing appears to approach, and even exceed, returns from traditionally more high paying commercial uses. In addition, the apparent high demand for housing within easy walking distance from the financial district may reduce the traditionally high marketing risks associated with the development of housing. Therefore, it may make good

economic sense to redevelop this site, which otherwise may be more appropriate for commercial uses, principally as housing.

LOCAL HOUSING MARKETS

In order to better understand the Boston housing

market, and determine if housing is the most appropriate use for this site, therby creating enough value to justify the stated purchase price, a unit pricing strategy and

absorbtion rate must be assumed. To do this we must look at the local supply and demand for waterfront housing. "Brokers

state that it is this market (young professionals) and the empty nester and divorced persons which has created the great demand for condominiums in this area. From 1969 to

1983, 1,022 condominium units were established .... through

conversion of rental property, rehabilitation of existing buildings and some new construction." 9 A number of

waterfront housing developments have been built, and it may be useful to look at how quickly they have been absorbed and at what price.

The following table, Exhibit 5, lists average sale and resale prices for Lewis Wharf, Union Wharf, The Mariner, and Harbor Towers. The sources of information include interviews with waterfront brokers, two waterfront developers and sale histories of the developments over the last three years.

EXHIBIT 5

AVERAGE SALE AND RESALE PRICES OF BOSTON WATERFRONT HOUSING

EXISTING DEVELOPMENT year units price/sf resale/sf

Lewis Wharf Union Wharf The Mariner Harbor Towers 1977 1977/79 1985-86 84 59/27 84 295 75* 365 302 266 -- 150-200

* Prices for unfinished "loft space" units

PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT year units price/sf

Lincoln Wharf 86-87 44 300

Rowes Wharf 87-88 100 450

Fan Pier/Pier 4 88-98 1500 250-275

San Marco 86-87 192 Units will be sold

at cost to North end residents

Based on the prices for existing residential

waterfront developments averaging around $250/sf, proposed waterfront developments averaging about $325/sf, new

Monument Square condominiums at $250/sf, an average sale price of $250/sf may be assumed for the Wharf Number 3 development. There is however, some concern, expressed by

real estate brokers that sites such as Wharf Number 3, with the potential for high levels of tourist pedestrian traffic, are not as desirable for housing as more private and

isolated locations. The same brokers also suggested that the Rowes Wharf development will not reach its expected sales potential because of the high levels of pedestrian traffic on the waterfront, at nearby Quincy Market, and from the ferry terminals.

In addition to the negative impact of pedestrian

traffic on this site, other factors may reduce the value of residential units. For example, even though there exists, at present, a tremendous demand for housing in downtown, a number of factors may change over the course of this

project's development, reducing that demand. Much housing is now under development and construction. According to the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, the pace of new Massachusetts housing construction is at its highest in seventeen years and may set a new record by the end of 1986.10

During the first half of 1986, permits were issued in the city of Boston for construction of more than 2,300 new housing units. This is nearly double the rate of new

Boston housing construction in 1985 and is expected to set record levels for 1986. This rate of increase in the supply

of housing exceeds the household growth rate and will have a net affect of reducing demand. Further, the present high level of housing demand has forced the city of Boston and the state of Massachusetts to create new programs that

encourage housing construction through simplification of the approval process. In addition, many new Boston area

construction and development firms have been recently formed to fill the demand for housing. It is unlikely they will

quit building until the supply is increased enough to reduce demand and prices to the point where housing construction is no longer economical.

It is therefore expected that these present high levels of Boston area housing construction will continue

satisfying any increases in demand, and softening the

present strong housing market. Accordingly, $200/sf may be a more conservative estimate of 1989 housing values at this location.

Even at a "conservative" $200/sf, the $180,000 sale price of a 900 sf condominium in this development will be well beyond the means of the average two or three person household within the Boston SMSA. Assuming a 10%, 30 year mortgage, the average two person household with an anual income of $30,600 qualifies for slightly less than a

$100,000 loan. Therefore a lender will require this buyer to contribute more than $80,000 in downpayment to purchase a unit. If a potential buyer has only $25,000 for

downpayment, he will need to have an anual income of almost 50,000. While this is significantly above the average

Boston SMSA two person household income, there still exists a large pool of potential buyers in this income range. If however, mortgage interest rates rise to 13% during the course of this development, the buyer with a $25,000

downpayment will have to earn slightly more than $60,000 per year to qualify. The pool of Boston home buyers with incomes greater than $60,000 is considerably smaller and unit

absorbtion rates will most likely be slower. Thus, the market for these units is extremely interest rate sensitive.

In addition to the pricing of the units, it is

important to better understand the rate at which they might sell and what factors can influence that rate. Exhibit 6 indicates absorbtion rates realized in other Boston

waterfront developments. 12

EXHIBIT 6

HISTORIC ABSORBTION RATES FOR BOSTON WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT

presale sale total absorp.

Development period period units units/mo

Lewis Wharf 12 8 84 4.7

Union Wharf 9 12 59 2.8

Phase One

Union Wharf 12 0 27 2.3

Based on these absorbtion rates, averaging about 3.5 units per month it is assumed that a well priced, well

marketed development on Wharf Number 3 will sell as least as well as these other developments. Therefore, we can assume a conservative sales rate of 3.5 units/month.

After taking into consideration the pricing information discussed earlier in this chapter, it is important to note that a strong absorbtion rate is dependent on the units being priced below the bulk of other waterfront projects expected be on the market at the same time, such as the Pier

4 and Fan Pier condominiums. This will ensure few waterfront substitutes exist and the largest number of potential buyers in the development's price range.

Therefore, demand for these units may be less price elastic than the higher priced "luxury" units with a smaller

potential pool of buyers and many housing substitutes.

RETAIL MARKETS

It is assumed that the retail or commercial portion of this development will play a less significant economic roll than the residential portion. Nevertheless, an

understanding of the waterfront commercial market will be helpful in ensuring the correct mix of uses for the site.

Retail space within the Pier 4 and Fan Pier development is expected to come on line at about the same time as the Wharf Number 3 development, and is expected to net more than $45/sf. This number appears somewhat high in light of

exclusive Quincy Market retail space renting today for the mid 30s, according to Mary Ann Gilligan Rose, Manager of Tenant Services, Faneuil Hall Marketplace.13 The rents in Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market also include percentage rent plus a healthy $30/sf "extra charge", typical of festival market places, in addition to the mid 30s base rent. (at a typical suburban mall these extra charges amount to about

$7 or $8/sf) "In general," said Mary Ann Gilligan Rose,

"total rent should be about 10% of the retailer's gross sales." 1 Based on this information, the expected high

level of tourist and pedestrian traffic, it is assumed that retail space on Wharf Number 3 will net about $30/sf.

However, due to the un-proven location, it may be

necessary to invite retailers with low base rents and expect to realize the full rent in percentage of sales. Retail and commercial rents at this location are extremely difficult to predict, but as the economic analysis in Chapter Five

demonstrates, variability in retail rents achieved will not greatly influence the expected returns, due to the low

TIMING

Even more important than today's demand, will be the demand in three or four year when this project is finally ready to be occupied. Therefore, a thorough understanding of both the proposed development schedule and opportunities that exist for flexibility in that schedule is essencial in evaluating the probability that the buyer will indeed be able to pay the stated price.

For example, changing demographics, particularly the large number of people in their mid thirties entering the family formation and child rearing years, may make urban housing somewhat less attractive than other alternatives. Also, proposed changes in the federal income tax laws may make condominiums less attractive to investors. In

addition, if the demand is perceived to be slipping, many investors who are currently buying urban condominium

properties for the expected appreciation may select other investment alternatives, further reducing the demand for housing. The market influencing power of these investor buyers is not to be underestimated. According to Mayor Flynn's policy director, Neil Sullivan, "the study by the mayor's office of 1984-85 condominium sales showed that 75% of converted (condominium) units in Boston were sold to investors."1 5 Further, Bob Van Meter, legeslative director

of the Massachusetts Tenants Organization, says "a study he conducted in April, 1985 showed that investors held well over half the condominium market, especially in areas such as the Fenway, Allston and Brighton."1 6

There is some evidence that due to the changing tax laws this may already be occuring. According to the Boston Globe, "Adding to the gloom of condominium converters and investors are increasing indications that the housing market in Boston has crested, which would mean an end to the fast-paced appreciation of recent years."1 7

By the same token, current demand for office and retail space is somewhat less dramatic than the housing demand, and accordingly, developers are building fewer new office and retail facilities along the waterfront than are building

expensive condominium projects. Therefore, in three or four

years, demand for retail or office space may dictate that a

greater portion of the development be dedicated to those uses.

Regional economic health, currently strong due to expansion of the service businesses, law, banking etc, and the high technology and defense related industries, may change, therby reducing the ability of some Boston area companies and people to continue their present pattern of

increasing the quality and quantity of space they consume. If the present trend changes, due to a change in political

administration or other macro-economic forces, demand for all uses will be reduced and some uses will be more

sensitive than others.

In addition to demand and supply, other physical or social changes, over time, can affect the proposed

development. For example, the Massachusetts State Highway Department's plans to depress the existing overhead

expressways at Charlestown's City Square will have a dramatic impact on the marketability of this project.

Exhibit 7 illustrates the present expressway configuration over Charlestown's City Square as it relates to Wharf Number

3, and Exhibit 8 illustrates the proposed expressway configuration.

The expressway construction is expected to take place over a five year period, starting in 1986 and completing in

1991. At the time of completion, six parcels of land

surrounding the new City Square will be turned over to the BRA and developers will be invited to submit redevelopment proposals for those sites. Accordingly, the ultimate

character of those sites will have a large influence on the value of the Wharf Number 3 development.

EXHIBIT 7

EXISTING OVERHEAD EXPRESSWAY CONFIGURATION AT CITY SQUARE

\ ~ / N \ \ / // / I \Y/ t. - 1 V~-1\co/ 14,Y/

EXHIBIT 8

PROPOSED EXPRESSWAY CONFIGURATION AT CITY SQUARE

\

/N\////

&vV(6-

)/)h

All this construction and change will affect the Wharf Number 3 site in two ways. First, during the construction period, access to the site by both pedestrians and

difficult until the highway construction is complete. Second, the final configuration of surface streets and development parcels surrounding City Square is not yet

determined, and may go through several evolutions before the final character can be established. This means that the quality of ultimate finished access to this site cannot yet be determined. Further, it means that future City Square developments may either compliment or compete with Wharf Number 3 uses. Therefore, a developer of this site must start immediately to understand the potential character of

future neighboring uses and to lobby for the most positive "front door" possible.

Also there is political support, at present, for

inclusionary zoning that will require condominium developers to make a percentage of their units available and affordable to low or moderate income families. Mayor Flynn supports this movement and, if it is incorporated in zoning rules, will have a serious affect on the profitability of the development.

CHAPTER TWO

PRELIMINARY DEVELOPMENT PHYSICAL ORGANIZATION

In order to thoroughly evaluate whether or not

redevelopment of the Wharf Number 3 property will generate sufficient value to cover development costs and leave a

residual value to the land that will justify its sales price, it is important to examine more specifically the optimum

organization of site uses. The following diagrams define a physical development that attempts to take best advantage of the urban design, social and political, government agency regulatory, market forces, and timing issues discussed above.

EXHIBIT 9

SITE ORGANIZATION PLAN

EXHIBIT 10

SITE ORGANIZATION CROSS SECTION

48Units

48 Units

48 Units

26 Units

Retail

Harborwalk

Site

Section

EXHIBIT 11 DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Housing (170 units at 900 sf = 153,000sf net) Designated parking for housing(170 spaces at 350 sf/space) Retail/Commercial space

Public parking

(outdoor unstructured)

(40 spaces at 350 sf/space)

Public Harborwalk area (25 X 550) 170,000 sf 60,000 sf 20, 000 sf 15,000 sf 13,750 sf

Incorporated in this preliminary design are a number of important features. The public Harborwalk access can be provided along the water side of the Wharf, connecting the

Charlestown bridge on the west side of Wharf Number 3 to continuing pedestrian activities at Hoosac Pier,

Constitution Wharf and the Charlestown Navy Yard on the

Wharf's east side. Immediately adjacient to this walkway is located all the commercial activity within the development. It is hoped that this walkway and commercial activity will be attractive enough to "pull pedestrians off the

Charlestown Bridge and through this development on their way home to Charlestown or the Navy Yard.

Immediately behind this commercial activity is the required parking and service activities with ready access along Charles River Avenue to Constitution Avenue. On the second level will be residential units located on the east side of the Wharf with views of Boston harbor, and

residential parking on the west side adjacent to Charles River Avenue and the Charlestown Bridge. On the upper

floors will be additional residential units with views toward the east and Boston harbor as well as toward the west, over the Charlestown bridge toward the Charles River.

It is likely that the upper units with harbor and downtown views will sell at a significant premium above the $200/sf

will sell at a discount.

The extreme south end of the Wharf appears to be a good location for a restuarant. A well designed restaurant in this location, with fair weather expansion potential for outdoor seating and excellent views of the Boston skyline and Boston harbor, will give the development a unique

identity and special character.

This unique character has the potential to aid the marketing of condominium units provided the concerns for privacy expressed in the local housing markets section of Chapter One are addressed. Of critical importance

therefore, is maintaining the perception of separation

between residential units and retail or commercial activity. If commercial activity and public walkways are limited to the first or wharf level, this space will be accessable and attractive to pedestrian traffic. By placing the

residential units above the commercial activity, public walkways, service traffic and parking, and by emphasizing privacy and security in the unit construction and design, a number of the concerns about living close to public retail activity can be addressed.

It is important that balconies and outdoor spaces be designed with privacy in mind, and that views from the units be directed toward distant amenities but shielded from

designed to provide private, dignified and secure access to the private residential portion of the development. Also, the construction must be of a type that reduces noise

transmssion from the public level retail spaces to the housing. Accordingly, the insulation, windows and doors must be selected with privacy and sound control as primary

CHAPTER THREE

PRELIMINARY DEVELOPMENT COST ANALYSIS

An evaluation of the various hard and soft costs involved in the development of the Wharf Number 3 site is most important at this stage, and yet very difficult to do without a more specific idea of the exact uses and building design. Further, it is assumed that the exact mix of uses and density of the development may change before

construction is started and during the course of development to take advantage of changes in market conditions,

regulatory modifications, or community concerns. Therefore it is important to develop a model for these costs that can be easly modified to represent different mixes of uses for

future economic analysis.

HARD COSTS

An estimate of the hard costs associated with the Wharf Number 3 development, previously described in Chapter Two, Preliminary Development Physical Organization, are included

in the following table. These costs are inflated to 1988 dollars based on a three per cent per year inflation rate. Infrastructure costs, costs for utilities, streets, wharf repair, etc, are based on recent BRA Harborpark planning

guide estimates. In addition, wharf repair estimates are based on conversations with Maurice Freedman P.E. of Sasaki Associates Inc.19 Site costs represent only those costs associated with the surfaces required by the BRA on the public Harborwalk portion of the site. Costs for

construction of housing units, commercial and office space were taken from recent development proposals within the

nearby Charlestown Navy Yard. In general, if there existed a difference of opinion about a particular cost, the higher cost was used. Therefore these cost estimates may be somewhat conservative.

EXHIBIT 12

UNIT PRICE ASSUMPTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT HARD COSTS

UNIT PRICES Site (Landscape) 7/sf Infrastructure allow. Demolition allow. Housing 70/sf Retail 45/sf Parking 25/sf

DEVELOPMENT HARD COSTS

Site Costs $161,000 Infrastructure $1,100,000 Demolition $500,000 Housing $11,000,000 Retail $900,000 Parking $1,847,000 $16,486,000 Contingency 5% $824,000 HARD COSTS $17,310,000

A number of risks are associated with these hard cost assumptions and should be monitored during the course of the

development. For example, the wharf itself may require significant repair, the BRA may require significant

public walkway improvements site or infrastructure costs may exceed the estimate, or the architectural design of the buildings may not fall within the expected price ranges. Also, micro-economic conditions in the local construction

industry, such as strikes and material or labor shortages may drive prices up. Finally, macro-economic construction

industry trends affecting costs of materials such as steel and lumber may increase or decrease the cost of building the development.

SOFT COSTS

An evaluation of the soft costs associated with the development is equally important, particularly in a

complicated and heavly regulated project that may take as long as four years to complete. The following table of soft cost values is based on soft costs included in recent

developer's proposals for other mixed use developments within the nearby Charlestown Navy Yard.20 Construction loan

interest costs are calculated based on a 10 % interest rate and a unit sales rate of 3.5 units per month. Construction

loan interest is a large expense and will have a large

variations in this amount due to changing interest or

absorbtion rates are addressed in the financial risk analysis portion of Chapter Five.

EXHIBIT 13

DEVELOPMENT SOFT COSTS

Architecture and Engineering % of hard costs Developer's fee % of total cost Marketing % of sales Real Estate Taxes Charlestown Contrib. Legal and Accounting Fees and Permits

Contingency 5% TOTAL SOFT COSTS

HARD COSTS SOFT COSTS

INTEREST EXPENSE LAND COST

TOTAL PROJECT COST

$824,300 5% $1,000,000 3% $1,580,000 5% $633,333 $100,000 $200,000 $100,000 $4,437,633 $221,882 $4,659,525 $17,310,000 $4,659,525 $3,762,686 $4,500,000 $30,232,211

CHAPTER FOUR

PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT SCHEDULE

Based on the present understanding, the developer of Wharf Number 3 plans to gain all necessary approvals and do necessary preparation during 1986 and 1987, purchase the property in 1988 and begin construction immediately. If he proceeds on this schedule, he will be able to complete the

construction in mid-1989 and complete selling out his units by 1992. Exhibit 14 illustrates a preliminary schedule for this assumed plan.

EXHIBIT 14

PRELIMINARY DEVELOPMENT SCHEDULE "A"

Schedule "A" assumes purchase of site in 1988 and construction beginning immediately.

SCHEDULE '

PROJECTED SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

1986 198? 1908 1989 1990 1991 1992 Establish Program XXXXXXXXXX XX XX XX Market Research XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Approval Process XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Rrch./Engineering xx XX XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Financing XX xxxxxxx Purchase Property XX Construction XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Lease Retail Space XX XX XXXXXX

Based on the BRA's estimate of an eighteen month approval process for a development on this site, it is necessary that the developer complete initial market and

feasibility studies by early 1987. Then, during the approval process further architectural development,

community relations financing and cost control work can be accomplished so that, once the land is purchased in mid-1988, construction can immediately begin. The construction period is expected to extend for aproximately eighteen

months with units ready to occupy in early 1990. This construction period is a little longer than one might

usually expect for a development of this size. The longer construction period includes delays resulting from potential site accessability problems and the BRA Harborpark

requirments for continued public pedestrian access across the property. On the other hand, nearby pedestrian traffic while construction is in progress, will help to pre-sell

residential units and pre-lease the retail space. It is assumed that the 170 residential units will continue to be sold, at the conservative rate of aproximately 3.5 per month, through the end of 1991.

It may however, be in the developer's best interest to change this schedule. Accordingly, the seller should be aware of, and prepare for, such an occurance. For example, due to the uncertianty and limited access during the highway construction associated with depression of the overhead

expressway at nearby City Square, the developer may feel it is in his best interest to delay starting construction. He may wait until the outcome is more certain and access to his

site for both construction and residential unit buyers is secure. This may simplify the construction process, reduce construction costs and ensure that the retail space and residential units are marketable when they are complete and ready for occupancy. This will mean closing on the property in 1988, performing market research, approval, and design work in 1989 and 1990, once the final City Square character

can be better determined. Then construction can be started

in late 1990, putting new residential units on the market at

the same time the new City Square is complete, but before any of the redevelopment occurs on the six parcels surrounding the square to compete with Wharf Number 3 units. An

illustration of this revised schedule is included below in Exhibit 15.

EXHIBIT 15

PRELIMINARY DEVELOPMENT SCHEDULE "B"

Schedule "B" assumes purchasing site in 1988 and delaying construction start until 1990.

SCHEDULE 'I"

PROJECTED SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

1986 198? 198g 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 Establish Program XXXXXXXXXX XX XX XX Market Research XXXXXXXXXXXX XX XX XX XX XX XX XX XX XX XX Approval Process XX XX XX XX XX XX XXXXXXXXXXXMXXXMXXXXXXXX Arch./Engineering XX XX XX XX XX XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Financing XX XXXXXXXX XXXXXXX Purchase Property XX Construction XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Lease Retail Space XX XX XXXXXX

Sell Residential XX XX XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXJXijQ(

Expressway Const n 00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 0000000000

While Schedule "B" may make more sense from a construction and marketing point of view, it has some

negative aspects. For example, the market for housing and commercial space can change dramatically during 1988 and 1989, making alot of the market research and architectural design and government approval work obsolete and out of date by 1990 when construction is due to start. In addition, a substantial amount of money will be expended quite early in the project, during 1987 and 1988, for research, design, and particularly for the property, only to accrue interest

expense during 1989 and 1990.

As we shall see in Chapter Five: Economic and Financial Analysis, these holding costs are not insignificant and

directly affect the profitability of the development.

Therefore, an astute or shrewd developer may attempt to delay the majority of his market research, government agency

approval, and architectural design work as long as possible and stall the property purchase until he is ready to begin

construction in 1990. This strategy will reduce his risk by delaying his expenses as long as possible, and still bring retail space and residential units on the market at the best time. In addition, it postpones his true decision point until 1990, a time when he has a better idea of market

conditions. Exhibit 16 illustrates this potential schedule.

EXHIBIT 16

PRELIMINARY DEVELOPMENT SCHEDULE "C"

Schedule "C" assumes delaying the site purchase and construction start until 1990.

SCHEOULE "C'

PROJECTED SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 Establish Progran XX XX XX Market R.rearch XX XX XXXX XX XX XX Approval Process XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Arch.iEngineering XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Financing XX XXXXX X Purchase Property XX Construction XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Lease Retail Space XX XX XXXXXX

Sell Residential XX XX XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

CHAPTER FIVE

ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

Based on a land price of 4.5 million dollars and the potential of constructing 170 condominium units, the

property is selling for $26,500 per unit. This represents less than 15% of the $180,000 unit sales price and, by traditional rules of thumb, is a reasonable sales price. However, there are a number of factors unique to this

specific development that require a more complex analysis of the project economics before predicting a successful

development.

DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS

Based on the following income and expense pro forma, Exhibit 17, the development of Wharf Number 3 as assumed in Schedule "A" provides an IRR of 18% and a Net Present Value at 15% of $926,555, in an all equity development, before debt service or tax considerations. These return measures appear to be sufficient to justify pruchase of the property and

preceeding with the development. However, there is not a lot of room within these returns for the developer to share the profit with limited partners.

These returns are, of course, based on a number of

assumptions. For example, it is assumed that all the soft

costs are equal during each of the first four years of the

development process. Since these include costs that will be expended later, rather that earlier, this averaging

convention is conservative. Also construction costs are simply assumed to be equal during both of the two years in which construction occurs, rather than a more accurate, but less conservative, " back end loading" of these costs. In the same way, proceeds from the sale of residential units are simply assumed to be evenly distributed over the three year post construction sale period. While the favorable returns that result from these conservative assumptions

appear to justify proceeding with the project, there exist a number of risks associated with the development.

EXHIBIT 17

INCOME AND EXPENSE PRO FORMA (SCHEDULE "A")

Schedule "A" assumes the site is purchased in 1988 and construction begins immediately.

SCHEDULE 'A'

OPERATING PRO FORMA

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 S3;22222222 .... 23 . . 2. .2. . . . . . . . . 3 EXPENSES soft costs ($825,349) ($825,349) ($825,349) ($825,349) Hard costs ($9,067,3001 ($9,067,300) Land cost ($4,500,000)

Real Estate Taxes ($100,000) ($100,000) ($100,000) (1100,000)

and op exp

INCOME

Retail rent (net) $570,000 $570,000 $570,000 $570,000 $5,700,000

Unit sales (less coaissions) $9,753,333 $9,753,333 $9,753,333

Cash Flow ($825,349) ($825,349) ($14,392,649) $330,684 $10,223,333 $10,223,333 $470,000 $5,700,000

IRR 181

NPV 1 151 $926,555

These risks may have a direct affect on the developer's ability to produce a successful development and pay the seller's sale price. For example, the approval process may not go as smoothly as planned, resulting in substantial program modifications, an extended time period required for gaining approval or complete denial of the development. Second, the costs of construction may greatly exceed preliminary estimates, reducing the feasibility of the project.

Of even more importance, the preliminary program or expected markets for retail and housing on this site may change, reducing the sale or rental price achievable or increasing the time required to market the project. The following table, Exhibit 18, indicates the effect variations in average residential sale price per sf, and average retail rent per sf can have on the IRR. Given that all other

assumptions are accurate, the retail rent/sf can drop to 15/sf and the average residential sale price can drop to 175/sf, and the IRR only drops to 12%. If however, retail rent of 35/sf and residential sales of 275/sf are

achievable, the IRR can be as high as 44%. Based on this analysis, it is understood that housing prices are more important than retail rents in determining the ultimate feasibility of the project, and in determining the

EXHIBIT 18

IRR AS A FACTOR OF RETAIL RENT/SF AND HOUSING SALES PRICE/SF

RETRIL RENT / SF

10 15 20 25 30 35

100 -iU -A - 2 -32 71

125 -6x -3% -11 2. 412 6x 150 22 I2 71 a% 102 12x UNIT SALES/SF 175 10E 121 12 152 172 18

200 1? 19M 21x 222 24x 252 225 25% 26a 282 291 302 312 250 32z 33% 341 362 372 382 275 391 4ON 41 422 43. 4 300 161 4?x 491 481 491 50 325 52z 531 541 552 562 561 350 582 592 602 612 622 622

While these projections of potential return from developing the Wharf Number 3 property appear to indicate the buyer should not have a problem proceeding with the project and paying the seller, he may, for reasons

discussed earlier in Chapter Four, decide to delay starting construction until 1990. Exhibits 19 and 20 illustrate

income and expenses for developments described in Schedules

"B" and "C" respectively. Pursuing the course of action

described in Schedule "B" generates significantly lower returns than those derived by building immediately. The developer who desires to delay construction beyond 1988 or

1989 may not find the development feasible unless he can renegotiate the sale price or delay expenses as indicated in Schedule "C". On the other hand, while this delay helps the developer, it results in the equivalent of a $1,097,000

EXHIBIT 19

INCOME AND EXPENSE PRO FORMA (SCHEDULE B)

Schedule "B" assumes purchase of the site in 1988 and delaying construction start until 1990.

SCHEDULE '8*

OPERATING PRO FORMA

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993

EXPENSES

soft costs

Hard costs Land cost Real Estate Taxes

and op exp ($550,233) ($550,233) ($550,233) ($4,500,000) ($550,233) ($550,233) ($550,233) ($9,067,300) ($9,067,300) ($100,000) INCOME

Retail rent (net)

Unit sales (less comeissions)

$570,000 $570,000 $5,700,000 $9,753,333 $9,753,333 $9,753,333 ($550,233) ($550,233) ($5,050,233) ($550,233) ($9,617,533) $605,801 $10,223,333 $15,453,333 141 ($154,383) $9,964,003 EXHIBIT 20

INCOME AND EXPENSE PRO FORMA (SCHEDULE C)

Schedule "C" assumes delaying site purchace and start construction until 1990.

of

SCHEDULE "C'

OPERATING PRO FORMA

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993

Zzma

mm xan2232z2azx.EEE33323Ema2.E 23mc~asszzxz2=22=2jmzuzzxxzammxzzxsmamma323EEEEEEEEEE.BRREREz3E3E33sRERxmEER.E M.2($825,349) EXPENSESsoft costs Hard costs Land cost Real Estate Taxes

and op exp

INCOME

Retail rent (net)

Unit sales (less cossissions)

Cash Flow IRR NPV I 15Z sun ($825,349) ($825,349) ($825,349) ($9,067,300) ($4,500,000) ($825,349) ($9,067,300) ($100,000) $570,000 $570,000 $5,700,000 $9,753,333 $9,753,333 $9,753,333 Cash Flow IRR NPY 1 15Z suN ($100,000) ($100,000) so $0 ($825,349) ($825,349) ($14,392,649) $330,684 $10,223,333 $15,453,333 19Z $867,749 $9,964,003 manazaazzxszxacuxn*zzuzzax2zuxznxazazczznxzzxsmz===Zzzzizszz=zzzzzz=z==zxxxzzzzzxzzcxanxz=aaunuszaxazu2nz=zzsznxx

FINANCIAL RISK ANALYSIS

In addition to examaning the basic economics of this development, it is necessary to look at a more complex,

leveraged development plan, and at the effect leverage will have on the expected returns and associated land value. This more realistic development model will enable us to understand the affect variations in absorbtion rates will have on holding costs and expected returns. It will also help us understand the interest rate risk and equity

requirements under our three different schedule assumptions.

The following income and expense proforma, Exhibit 21, models development of the site with a construction loan and

a permanent or take out loan for the retail portion of the development. According to this leveraged analysis, the development yealds an IRR of 27% and an NPV at 15% of

$926,555. These leveraged returns include enough profit to split with potential limited partners and appear to justify proceeding with the development.

EXHIBIT 21

LEVERAGED PRO FORMA (SCHEDULE "A")

Schedule "A" assumes purchase of the site in 1988 and beginning construction immediately.

SCHEDULE 'A'

OPERATING PRO FORMA WITH LEVERAGE 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 EXPENSES soft costs ($825,349) ($825,349) ($825,349) ($825,349) Hard costs ($9,067,300) ($9,067,300) Land cost ($4,500,000)

Real Estate Taxes ($100,000) ($100,000) ($100,000) ($100,000) ($100,000)

and op exp LEVERAGE Construction Loan Draw $11,543,348 $9,892,649 Interest (accrued) $577,167 $1,706,684 $1,168,651 $310,183 Repayment ($12,033,333) ($9,753,333) ($3,412,016) Permanent Loan $4,560,000 Interest ($228,000) ($456,000) ($456,000) ($456,00 Repayment ($4,560,000) INCOME

Retail rent (net) $570,000 $570,000 $570,000 $570,000 $5,700,000

Unit sales (less commissions) $9,753,333 $9,753,333 $9,753,333

Cash Flow ($825,349) ($825,349) ($2,849,302) $2,522,000 $14,000 $6,355,317 $14,000 $584,000

IRR 271

NPV 1 151 $1,177,435

sum $4,989,317

This pro forma assumes construction loan and permanent loan interest of 10%. It also assumes that the construction loan repays soft costs expended during the two years prior to the construction loan closing. It also assumes that the

construction loan does not "finance out" the site costs. Construction loan interest accrues until cash flow is

available. at that time, all cash flow from unit sales and one half the proceeds from retail space refinancing goes to

repay the construction loan.

Based on this schedule, total construction draw equals about 25.6 million dollars or about 70% of the development's market value. Most lenders will find this an acceptable

ratio of loan-to-value. In addition, it assumes net retail rents of 27/sf (net of commissions) and condominium unit sales of 190/sf net of 5% sales expenses. Based on these assumptions, the development requires 4.5 million dollars in equity over the first three years, equal to the site

costs since the soft costs are repayed to the developer from construction loan proceeds.

While it appears that leverage improves the returns and limits the equity requirements, this is not true if the

development proceeds more slowly as discussed earlier in Chapter Four. According to Schedule "B", as indicated in the Exhibit 22 pro forma, if the construction is not started until 1990, the development requires more than 6.7 million dollars in equity over the first four years and delivers only an IRR of 15%. The higher equity requirement covers soft costs expended during the first few years that would not be recoverable from construction loan proceeds because they were spent so early on in the process. While this is considerably less equity required than the unleveraged development plan presented in the economic analysis of

EXHIBIT 22

LEVERAGED PRO FORMA (SCHEDULE "B")

Schedule "B" assumes that the site is purchased in 1988 but

costruction is postponed until 1990.

SCHEDULE '8'

OPERATING PRO FORMA

WITH LEVERAGE 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 EXPENSES soft costs Hard costs Land cost Real Estate Taxes

and op exp LEVERAGE Construction Loan Draw Interest (accrued) Repayment Permanent Loan Interest Repayment ($550,233) ($550,233) ($550,233) ($4,500,000) ($550,233) ($550,233) ($550,233) ($9,067,300) ($9,067,300) ($100,000) $10,717,998 $9,617,533 $535,900 $1,606,266 ($12,033,333) $4,560,000 ($228,000) INCOME

Retail rent (net)

Unit sales (less commissions)

($100,000) $1,044,436 ($9,753,333) ($456,000) ($100,000) $173,547 ($1,909,014) ($456,000) ($4,560,000) $570,000 $570,000 $5,700,000 $9,753,333 $9,753,333 $9,753,333 ($550,233) ($550,233) ($5,050,233) 14Z ($131,774) $5,363,854 ($550,233) $1,100,466 $2,522,000 $14,000 $8,428,319

On the other hand, if the developer can delay the land purchase until 1990 as indicated on Schedule "C" in Chapter Four, he will experience much better returns. As indicated

58 Cash Flow IRR NPV 1 151 sun anazzzz=====ZZZKRNZZZZZZZ==ZZZZ=r--Zu=szzczzczzzzzzrzzzz=zzz2szz=czzzzzzzzzzzzzzman2azzmazzzxczsxzzzzzzzzzzczzzau