HAL Id: tel-03230848

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03230848

Submitted on 20 May 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Containment as Foreign Policy Doctrine in Two United

States ‘Wars’ : from the Cold War to the War on Terror :

How Do Arab Spring Countries Fit into the Scheme?

Hamda Tebra

To cite this version:

Hamda Tebra. Containment as Foreign Policy Doctrine in Two United States ‘Wars’ : from the Cold War to the War on Terror : How Do Arab Spring Countries Fit into the Scheme?. History. Université Paris-Est, 2020. English. �NNT : 2020PESC0029�. �tel-03230848�

Université Paris Est Creteil UPEC Ecole Doctorale Cultures et Sociétés

Laboratoire de Recherche: Institut des Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman (IMAGER)

Thèse de Doctorat

en Langue, Littératures et Civilisations Etrangers (Anglais) Specialité : Civilisation Américaine.

par

Mr Hamda TEBRA

Containment as Foreign Policy Doctrine in Two United

States ‘Wars’: From the Cold War to the War on Terror

How Do Arab Spring Countries Fit into the Scheme?

Directrice de Recherche Mme. Le Professeur Donna Kesselman

Professeur des Universités en Civilisation Américaine, Université Paris Est Créteil. Présenté et soutenu publiquement à l‘UPEC le 13 Janvier 2020 pour l‘obtention de titre de docteur en Etudes Anglophone - Civilization Americaine.

Membres du jury.

Mme. Isabelle VAGNOUX, Professeure des universités, Université Aix-Marseille, Présidente.

M. Olivier FRAYSSE, Professeur des universités, Université Paris-Sorbonne, Rapporteur.

M. Mokhtar BEN BARKA, Professeur des universités, Université de Valenciennes, Rapporteur.

M. James KETTERER, Professeur, Université Bard College, New York, Examinateur.

M. Mohamed Salah HARZALLAH, Maitre de conférences HDR, Université de Sousse, Examinateur.

Table of contents

Abstract --- v Résumé --- vii Dedication --- ix Acknowledgements --- x Acronyms --- xiList of tables and figures --- xiii

1. INTRODUCTION --- 1

The framework of neo-containment --- 4

Neo-containment in the MENA --- 8

Political Islam and containment --- 13

The dissertation’s main hypothesis --- 18

The PhD setting --- 18

Methodology --- 21

Dissertation outline --- 23

1. HISTORIOGRAPHY OF U.S. FOREIGN POLICY OF CONTAINMENT: THE COLD WAR AND THE WAR ON TERROR --- 28

1.1 Cold War studies --- 30

1.1.1 Orthodox perspective on containment --- 30

1.1.2 Revisionist perspective --- 39

1.1.3 Post-revisionism and the notion of containment --- 51

1.2 Terrorism studies: The U.S. War on Terror and the containment policy --- 60

1.2.1 Orthodox terrorism studies --- 61

1.2.2 Revisionist terrorism studies --- 67

2. CONTAINMENT IN THE COLD WAR AND POST-COLD WAR PERIODS:

REVISITING THE MAJOR PHASES TOWARDS NEO-CONTAINMENT --- 82

2.1 Containing the Middle East in the Cold War: historical perspective--- 85

2.1.1 Truman doctrine as MENA universal program --- 85

2.1.2 Eisenhower: the Middle East and the rise of Nasserism --- 92

2.2 Containment in the post-Cold War era --- 93

2.2.1 Persian Gulf Wars and Iraq War --- 97

2.2.2 Alliance system --- 100

2.2.3 War for oil and primacy --- 102

2.2.4 President Bill Clinton’s Dual Containment--- 103

2.3 The War on Terror: from Bush to Obama --- 117

2.3.1 The War on Terror: a pretext of convenience? --- 117

2.3.2 Bush Doctrine and the War on Terror in the MENA. --- 120

2.3.3 War on Terror: a war for primacy --- 123

2.3.4 Afghanistan --- 124

2.3.5 War on Iraq --- 132

2.4 The President Obama administration: was it a departure from the War on Terror framework? --- 145

2.4.1 The Middle East as the main area for the U.S. --- 148

2.4.2 Iran : from containment to engagement --- 150

3. MAJOR MECHANISMS OF CONTAINMENT FROM THE COLD WAR TO THE WAR ON TERROR --- 157

3.1 Economic containment --- 158

3.1.1 Economic aid --- 158

3.1.2 Aids as national security --- 161

3.1.3 The USAID --- 162

3.1.4 Forms of aids --- 164

3.1.5 Fighting Poverty as a containment policy --- 165

3.1.6 The Middle East and North Africa: specific region for economic aid --- 169

3.1.7 Economic rewards --- 171

3.2 Defending democracy as a means of containment --- 173

3.3 The military containment --- 188

3.3.2 The shift to the militarization of containment --- 190

3.3.3 Regime change --- 198

3.3.4 Military spending --- 199

3.3.5 The Military-Industrial complex --- 201

4. CONTAINING THE MENA: ARAB SPRING COUNTRIES AS CASE STUDY --- 203

4.1 U.S. Response to the Arab Spring and the alliance system --- 209

4.1.1 U.S. response to the uprisings: reluctance and the arc of history--- 211

4.1.2 The Importance of Ben Ali to the United States --- 215

4.1.3 Egypt: the U.S. response --- 221

4.2 The immediate post Ben Ali Tunisia and Mubarak Egypt: primacy at stake --- 230

4.2.1 Tunisia --- 235

4.2.2 Egypt --- 239

4.3 The Immediate post-Ben Ali and Mubarek Era --- 254

4.3.1 The ‘democratic’ transition --- 257

4.3.2 U.S. policy towards Morsi--- 264

4.3.3 Economic aid --- 267

4.3.4 The Israeli- Palestine conflicts --- 273

4.3.5 Iran: a key threat to U.S. primacy --- 276

4.4 Restoring previous alliances --- 280

4.5 Political Islam in the Arab Spring countries: the alliance at stake. --- 291

4.5.1 U.S. and Political Islam: a historical background --- 292

4.5.2 Egypt --- 295

4.5.3 Tunisia --- 296

4.5.4 Algeria --- 297

4.5.5 Palestine --- 298

4.5.6 The Arab Spring: neo-containment of Islamic governments --- 299

5. CONCLUSION --- 307

Labouratoire de Recherche où la thèse a été préparée : (IMAGER)

INSTITUT DES MONDES ANGLOPHONE, GERMANIQUE ET ROMAN (IMAGER) - EA 3958

Université Paris-Est Créteil Val de Marne (UPEC) Campus Centre - Bâtiment i3 - Bureau 202

61, avenue du Général de Gaulle 94010 Créteil Cedex

Structure(s) de rattachement :

UPEC - UFR de Lettres langues et sciences humaines

Abstract

This doctoral dissertation develops the notion of neo-containment in the post-Cold War era. Its premise is that Cold War containment evolved to adapt to new challenges in a new era and continued to be the cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy and notably during the War on Terror and the Arab Spring period in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). This research revisits the sizeable body of literature about the U.S. grand strategies from the early Cold War to the Arab Spring. It relies on data from official policy documents, policy makers‘ speeches, academic writings and various media resources to understand why, how and with what results the United States extended and developed the containment policy as its approach to the War on Terror and the Arab Spring.

The dissertation provides a balanced account of the extent to which what we have qualified as the major Cold War mechanisms of containment continued to be implemented in comparable proportions in the post-Cold War era, but to contain new adversaries, mainly in the MENA. The United States relied firstly on economic containment which consists in using its economic power either to weaken challenging rivals by imposing economic sanctions upon them or empower allies through annual economic packages. The second mechanism of containment is the commitment to defend the U.S. ideology of ―democracy‖ which continued to be a cornerstone of neo-containment policy in the 21st century. The successive U.S presidents played the democracy cardto contain allies and adversaries. They selectively accused some authoritarian governments of abusing democracy while turning a blind eye on others. Finally, military containment reflects the American administrations‘ reliance on annual military aid and training services at consistently high levels, despite the collapse of the ‗Soviet Threat,‘ to its allies, while at the same time continuing to advocate regional proxy wars in geostrategic areas to maintain its sphere of influence.

The dissertation also examines policies through the quest of primacy as U.S. ‗habit‘. It asserts, therefore, that the United States‘ political doctrines remained fundamentally unaltered despite the demise of the Soviet Union. The case study applies the dissertation hypothesis of neo-containment in U.S. foreign policy vis-à-vis the Arab Spring, to the U.S. quest for countering rivals such as Iran, by containing the newly elected Islamic governments in the Middle East and North Africa from 2011 to 2014. The Obama administration contained political Islam and Islamic parties in the Arab Spring countries as

the policy response to the dilemma they posed; even though they were democratically elected, the governments represented a threat to the United States alliance system.

Résumé

Cette thèse de doctorat porte sur le sens et rôle de la notion de néo-endiguement dans le contexte de l‘après-Guerre-froide. Elle postule que la politique d‘endiguement a évolué depuis pour s‘adapter aux nouveaux défis que pose le nouvel ère, tout en restant fidèle aux principes de la politique étrangère américaine développés pendant la Guerre froide durant la guerre contre le terrorisme et la période du printemps arabe qui a surgit dans la région du Moyen-Orient et de l‘Afrique du Nord. Ce travail de recherche revoit la littérature portant sur les grandes stratégies américaines, de la Guerre froide au printemps arabe. Il s‘appuie sur des données issues de documents officiels, de discours politiques, des écrits académiques, et de diverses ressources médiatiques pour comprendre comment les Etats-Unis ont pu adapter et adopter la politique d‘endiguement pour contrer la montée du terrorisme et la venue du printemps arabe.

Cette thèse présente une analyse détaillée des principaux mécanismes d‘endiguement de la Guerre-froide, tels que nous les avons conçus. Aussi, elle démontre l‘emploi de ces mêmes mécanismes durant la période de l‘après-Guerre-froide pour contrer les nouveaux adversaires, notamment dans la région duMoyen-Orient et de l‘Afrique du Nord. Les États-Unis se sont d'abord appuyés sur l'endiguement économique qui consiste à utiliser l‘arme économique, soit pour affaiblir leurs rivaux, en leur imposant des sanctions économiques, soit pour soutenir leurs alliés,en leur versant des aides économiques annuels. Ensuite, il y a l'engagement des administrations américaines à défendre l‘idéologie américaine de la « démocratie dans le monde », qui constitue la pierre angulaire de la politique de la Guerre froide au néo-endiguement du 21ème siècle. Les présidents américains successifs ont joué la carte de la démocratie pour soutenir les alliés et contrer les adversaires. Ils pointent du doigt, d‘une manière sélective, certains régimes autoritaires, tout en fermant les yeux sur d‘autres. Enfin, l'endiguement militaire reflète le recours des administrations américaines à apporter une aide militaire et technique considérable au profit de leurs alliés, malgré l'effondrement de la ‗menace soviétique‘, tout en continuant à préconiser des guerres régionales par procuration dans les zones géostratégiques afin de maintenir la sphère d'influence américaine.

Cette thèse examine également les politiques étrangères du point de vue de la quête de primauté qui constitue une constante de la politique étrangère américaine. Elle met ainsi en évidence la continuité des doctrines de la politique étrangère américaine qui ne s‘est pas

fondamentalement modifiée, en dépit de la disparition de la menace communiste depuis la chute du mur de Berlin. Notre étude de cas confirme notre hypothèse sur le choix du néo-endiguement comme politique étrangère américaine vis-à-vis du printemps arabe, visant à isoler les gouvernements islamiques fraîchement élus au Moyen-Orient et en Afrique du Nord entre 2011 et 2014. L‘administration Obama a œuvré activement pour endiguer l'Islam politique et les partis islamiques dans les pays du printemps arabe comme réponse au dilemme qu‘ils ontposé aux Etats-Unis : bien qu‘élus démocratiquement, ils ont représenté une menace pour le système d'alliances des États-Unis.

Dedication

To my mother and father To my son Ahmed Taha

To my wife Hela

To my brothers: Karim, Wissem, Fekredine and Ramzi To my sisters: Assia and Hamida.

Acknowledgements

I would particularly like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Donna Kesselman

without her unending patience and supportiveness; this doctoral disseration would not have been completed.

My thanks and gratitude also go to my doctoral school L'École Doctorale Cultures et

Sociétés (CS) and Institut des Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman (IMAGER) at the

University of Paris Est (UPEC) for their financial and logistic support and considerable patience. Without their generosity and tolerance, this thesis would not have been started, never mind finished. Grants to participate in the AFEA congrès in 2013 and research trip to the United States in 2018 have also been made possible. On these visits the Library of Congress in Washington, and Pubilic Library of New York in addition to interviews with experts and specialists were particularly helpful in assisting my research.

Secondly, I would like to thank those who have patiently accepted to read parts of my thesis and provided me with stimulating comments and suggestions. Among these, Stephen Pampinella,

Professor at State University New York at New Paltz whose constructive recommendations made outstanding improvements and nuancing of my arguments. Professor Jonathon Cristol, Adelphi

University, USA was so kind to read and comment upon parts of my research.

I wish to express my gratitude to my dear colleagues and friends: professors Bachar Aloui, Nesrine Triki and Adel Najlaoui for their comments, recommendations and moral support along

the writing of this research.

I would like to thank also Professor James Ketterer, the Dean of International Studies at

Bard College, New York and Academic Director of the Bard Globalization and International Affairs (BGIA) program who kindly hosted me as a research fellow at BGIA in 2018 and SUSI foreign policy program in 2015 in addition to his comments as a professor, experts and practioner of U.S foreign in the MENA.

I am grateful to my wife Hela ben Hassine for her unfailing optimism, support and patience.

Finally, I extend my sincere thanks to my family and close friends for their patience with all my many weird manifestations of stress and tiredness, particularly towards the last months of writing.

Acronyms

AMFOG: The Allied Mission for Observing the Greek Election. CCF: Congress for Cultural Freedom.

CENTO: Central Treaty Organization ―the Baghdad Pact‖. DAG: Democratic Army of Greece.

DOD: Department of Defense.

EBRD: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. FDR: Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

FIS: Islamic salvation Front.

FJP: Freedom and Justice Party (Jordon). GCC: Gulf Cooperation Council.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

IAEA: International Atomic Enegry Agency. IAF: Islamic action Front (Jordon).

ISIL: Islamic State of Iraq and Levant. ISIS: Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

JDP: Justice and Development Party (Morocco). JDP: Justice and Development Party (Turkey). KKE: Greek Communist Party.

MCC: The Millennium Challenge Corporation. MENA: Middle East and North Africa.

METO: Middle East Treaty Organization. NED: National Endorsement of Democracy. NSC: National Security Council.

NSC-68: National Security Council. NSR 12 The National Security Review.

OMA: Office Miliray Affairs.

PNAC: the American Project of New American Century. QDDR : Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review. SCAF: The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.

STAR: Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty.

UNITA: The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola. UNSCOM: The United Nations Special Commission on Iraq.

USAID: The United States Agency for International Development. USSR: The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

List of tables and figures

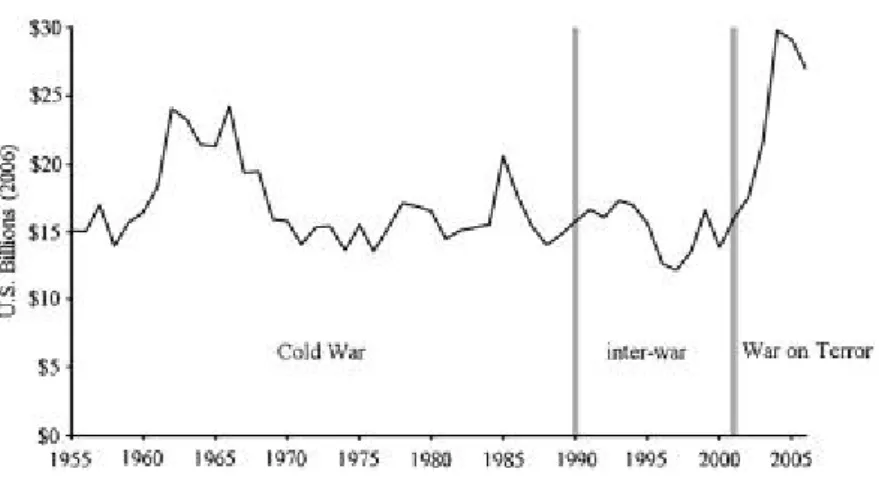

Figure 1: U.S. Economic aid: Cold War, Inter War period aand War on Terror ... 172 Figure 2: Map of the Greater Middle East ... 345 Figure 3: Countries scaled to the economic aid they receive from the United States ... 346 Figure 4: U.S. Defense Spendong from the Cold War to the Arab Spring (1947-2020) .. 347 Figure 5: Foreign Aid: Miliray and economic Aid from 1962 to 2020 ... 347 Figure 6: OPEC proven crude reserve by the end of 214 (Billion Barrrels) the MENA share ... 348 Figure 7: U.S. military expenditure from the War on Terror to the Arab Uprisinhs ( 2001-2014) ... 349 Figure 8: Miliray expenditure as a Percentage of GDP from 1941 to 2011 ... 350 Figure 9: U.S. military spending Percent of the World ... 350

1. Introduction

―Containment is something with which most people in the national security community have spent most of their lives.... We have become so accustomed to it that we rarely stop to consider what its precise goals are supposed to be.…‖1.

John Lewis Gaddis, 1986.

―Containment‖ was an American geopolitical and geostrategic grand strategy that aimed to restrict the influence and expansion of the Soviet Union during the Cold War through economic, political, diplomatic and military means. It was defined by its main framer, George Kennan as a ―long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies‖2. The main stated objective of this policy was to isolate, weaken and thereby lead to the collapse of Soviet Union from within, in other words as a means of avoiding direct confrontation. Containment is also defined as a middle ground ―between appeasement and détente‖. A more accurate identification is a ―policy of creating strategic alliance in order to check the expansion of a hostile power or ideology or to force it to negotiate peacefully‖3.

Containment policy was expanded beyond the initial geographic divisions that emerged in Europe, in the wake of the Yalta and Potsdam conferences at the end-World War II, towards continents and countries in other areas of the world where the Soviet Union challenged the interests of the United States. The competition was between ―spheres of influence‖ and ―Leadership‖. Containment became more and more militarized when, after Greece, the two superpowers became involved in indirect proxy conflicts including all-out wars in Korea and Vietnam, signaling the militarization of containment.

1 John Lewis Gaddis and Terry L. Deibel, Containment: Concept and Policy : Based on a Symposium

(National Defense University Press, 1986) 721.

2 George F Kennan, ―The Sources of Soviet Conduct,‖ Foreign Affairs 25, no 4 (July 1947): 566-582. 3 David J. Bishop, Dismantling North Korea's Nuclear Weapons Programs (Ft. Belvoir: Defense Technical

Administrations concomitantly endeavored to spread market capitalism and counter attempts to spread communism through economic and military aids and what is called today ―soft power,‖ diplomatic initiatives, all of which are termed here as the ―mechanisms of containment.‖ Their consistent deployment embodies the continuity analyzed here into the post-Cold War era.

What is termed as détente in the 1970s and the rollback in the 1980s during the Cold War, followed by the New World Order of the early 1990s and democratic enlargement and dual containment of the 1990s, were different faces of the same coin. They were the successive faces of the containment policy that was extended, according to the dissertation hypothesis, into the War on Terror and the Arab Spring era. What we term as ―neo-containment policy‖ is the vector of setting up the new system of post-Cold War regional alliances in the MENA in this overall framework. In the early 1990s and since the collapse of the Soviet Union, ―the United States show(ed) interest in the deepening of the neo-containment‖ with a great ―emphasis to the War on Terror‖ 4. In the MENA, since the 1979 revolution, it has been necessary to contain the regional rivalry of Iran and what other ―rogue states‖ in the MENA. The construction of the terrorist threat, the rise of political Islam in the late 1980s and 1990s as a threatening ideology to the United States interests in the great Middle East became the guiding line of U.S foreign policy. The War on Terror was the legacies of the President George H Bush New World Order and President Clinton‘s Dual containment.

Like during Cold War containment policy the aim was to avoid direct confrontation, to check the expansion of a hostile power or ideology while containing the « expansive tendencies at play, and this through the rebuilding a system of strategic

4 Emanuel Pietrobon, ―The neverending containment,‖ Association of Studies, Research and

Internationalization (Feb. 2019), online, internet, June 6, 2019. Availble: www.asrie.org/2019/02/the-neverending.

alliances in the region. American leadership has been threatened internationally by the emergence of the ascending superpowers such as China and Russia, the ex-U.S. Cold War nemesis whose attempt to gain ground in the MENA, especially since the 2010 events, has been a source of concern. Moreover Russian leaders have ―allowed China to emerge as an economic major power whose planetary ambitions are threatening the stability of the American empire‖5. These are the major factors involved in the U.S. attempt to reshape the MENA alliance system by mobilizing traditional allies to be engaged in the New World Order around the perusal of U.S. primacy. The 2010 Arab uprisings appeared as a concentration of these threats and as a testing ground of this strategy, as well as of its limits.

Since the onset of the Cold War between the United States and the Communist bloc led by the Soviet Union, the foundations of U.S. foreign policy has been subject to debate among historians, international relations analysts, political pundits and political-makers. More recently scholars have renewed these schools of thought to analyze the nature of the post-Cold War period and then the War on Terror.

Our contribution is to revisit these debates from our neo-containment perspective. We do so by shedding light upon the degree of continuity that links the periods of the ―two U.S. wars‖ and the superpower‘s policy in the MENA region. Containment policy was the core component of U.S. grand strategy during the Cold War and, as we will attempt to demonstrate here, it would continue to be the main policy pillar in post-Cold War era in the MENA region, during the George W. Bush and Barak Obama presidencies, in the face of new challenges, notably the declared Global War on Terror. The neo-containment prism shows to what extent scholarly analysis reflects, and is even a component of, this continuity.

The framework of neo-containment

President Bush stated the night of 9/11 that ―the Pearl Harbor of the 21st century took place today,‖6 referring to the foreign attack that propelled the United States into World War II and onto the world scene as a superpower. It was a clarion call for a revival of the U.S. grand strategy of primacy which is based on the need for U.S. leadership and its military supremacy to fight off a world-threatening enemy. This was not the starting point of neo-containment, however. A hard version had been imposed on Iraq and Afghanistan in the 1990s and yet doomed to failure, at least in terms of U.S. gains, for a military intervention to rollback the state was subsequently necessary to change the regimes and install pro-American rulers.

Afghanistan and Iraq were then to become the first countries forming ―the axis of evil‖7 according to George W. Bush, followed by Iran and North Korea. Iraq was the main concern after Afghanistan, it ―continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror‖8. Iran challenged U.S. power and ―aggressively pursues these weapons (WMD) and exports terror, while an unelected few repress the Iranian‘s people hope for freedom‖9. According to President George W. Bush, sponsoring terror and proliferation of WMD were the new motives to rationalize intervention in the Middle East. The message sent out through the military campaigns was that other key Middle East countries would face the same destiny if they would not cooperate in the War on Terror or challenge the U.S. in the region. ―You are Either with us or against us‖10 in the War on Terror, stated

6 David Kohn, ―Bush on 9/11: Moment to Moment, the President Talks in Detail about His Sept.11

Experience,‖ CBC News Sept .2, 2002. Online, Internet, Dec. 15, 2015. Availabe: www.cbsnews.com/news.

7 George W. Bush. President George W. Bush State of the Union Address, January 29, 2002 (Washington,

D.C: United States. White House, 2002).

8 Ibid. 9 Ibid.

10 George W. Bush. President George W. Bush Address to Joint Session of Congress, September 20, 2001. ,

President Bush; the MENA were in this way called upon to demonstrate unconditional support to the United States‘ campaigns in the Arab Muslim world.

The 9/11 attack was also seen by some historians as ―a new Pearl-Harbor-style‖11. For them, however, the meaning was that the event was instrumentalized, as the historical precedent in their eyes, to rationalize intervention into countries that had been for long hostile to United States strategic interests in the region. Martin Haliwell argued that ―[9/11] was a repeat of Pearl Harbor‖12 that was exploited to justify U.S. military operations on geostrategic countries like Afghanistan and Iraq that had been outside U.S. sphere of influence. In other words, the attack was turned to the advantage of U.S. decision-makers and so was perceived as a ―pretext of convenience‖13 to carry out policies that were already on the drawing board.

The war on Afghanistan and Iraq was a preventive measure against potential attacks upon the USA. Such ‗preventive‘ measures laid the basis for our hypothesis of neo-containment. George .W. Bush was essentially giving substance to the ‗New World Order‘ doctrine developed in 1990 by President George H. Bush after the fall of the Berlin Wall and while preparing to launch the first Gulf War.

The complex and ambiguous relationship between the U.S. government, its traditional allies and international organizations such as the United Nations is also a cogent area of continuity in U.S. policy when dwelling upon how the New World Order alliance, around U.S. leadership, would be built. International organizations such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the United Nations along the International Monetary Fund were traditionally integrated by successive U.S. administrations in the deployment of

11 David R Griffin, The New Pearl Harbor: Disturbing Questions About the Bush Administration and 9/11

(Moreton-in-Marsh: Arris, 2007) xi.

12 Martin Halliwell and Catherine Morley, American Thought and Culture in the 21st Century (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2013) 3.

the containment policy since the early Cold War. The United States engaged the U.N. in sanctioning unfriendly regimes worldwide and getting Security Council resolutions to authorize interventions in countries that ran counter its interests. In 1991, George W. H. Bush managed to form a coalition under the banner of the United Nations to attack Iraq while the next president to take the same path, George W. Bush, failed to get a resolution to legitimize the 2003 invasion. Although both the permanent members of the United Nations, except United Kingdom, and the majority of U.S. allies rejected the suggested American resolution to intervene in Iraq in 2003, George W. Bush authorized the war forming what he called ―coalition of the willing‖14. European countries and even Russia which had joined the first Gulf War in 1991 refused to be engaged in the 2003 War. The Bush administration nevertheless proceeded to unilaterally initiate the Iraq war with neither a U.N resolution nor the participation of the long-standing allies as France and Germany.

So while the operation was intended to be a manifestation of U.S. world leadership, it brought instead harsh criticism of the George W. Bush administration and a repositioning of U.S. leadership. The immediate post-Cold War era had been characterized by the U.S. habit to deploy allies in its interventions abroad to both legitimize wars and at the same time lessen the burden of military spending, as was the case in the first Gulf War in 1990-1991 and Haiti in 1994. ―In eight out of ten post-Cold War military interventions‖, the United States ―has chosen to use force multilaterally rather than going alone‖15; this is the New World Order U.S. Warfare strategy that was introduced by George H. W. Bush. In his book Coalitions of Convenience: United States Military Interventions after the Cold

War, Patrick A. Mello, argues that U.S. presidents from George Herbert Walker Bush to

14 George W. Bush, NATO Speech: Press Conference Bush - Havel - Prague Summit - 20 November 2002.

Online, internet, Nov. 19, 2015 Available: https://www.nato.int/docu/speech/2002/s021120b.htm.

15 Sarah E Kreps, Coalitions of Convenience: United States Military Interventions After the Cold War

Barack Obama relied heavenly on multi-national war rather than going alone to wars. It relied on ―coalitions and international organization blessing‖ which ―confer legitimacy and provide ways to share what are often costly burdens of war‖16That is the costs of war expenses and the political consequences of mult-national warfare are shared, and so less expensive to the United States.

In this line of thought the Iraq War is studied from a neo-containment perspective: how was it a manifestation of the U.S. attempt to reorient the regional alliance system and primacy as a continuation of the U.S. grand strategy, in this situation where the United States could not depend on its allies to endorse its interventions with legitimacy and credibility. The case also shows how the failure of political and economic containments led to military containment and therefore an intervention either to change the regime or destroy its economic and military power. The U.S. sphere of influence and other international organizations have been part and parcel of U.S. containment policy from the early Cold war to the Arab Spring era.

The fact that George W Bush ordered the intervention in Iraq in March 2003 without obtaining a U.N resolution, in line with standards of international law, could be seen as the pursuit of U.S. military domination. This display was a message toward enemies and allies alike to reassert U.S. leadership in the MENA and an implicit message to rival powers such as China, Russia and especially Iran. There are numerous interpretations explaining this raging aggressiveness to invade Iraq to the point of doing so through a unilateral decision, contrary to the first Iraqi War in 1991, a decade earlier, which had been waged under the U.N. banner.

Neo-containment in the MENA

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region were an integral part of containment policy since the early Cold War, a political strategy that, we argue, has continued in the post-Cold War era and especially in relation to the War on Terror. This takes the form of what is termed here as ―neo-containment‖. We study neo-containment by analyzing the continued application of the mechanisms of containment, from the Cold-War to the post-Cold War eras including the War on Terror and the Arab Spring eras and this through the theoretical framework of historical institutionalism.

The MENA was a key ground of dispute for the United States between the Soviet Union and the United States throughout the Cold War. Some MENA countries adhered to the Soviet orbit while others to that of the United States. The mechanisms of containment were deployed, to various degrees and periods in the MENA in relation to Iran, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Palestine, Lebanon etc., and notably in the two countries that will be the major focus of our study in chapter four, Egypt and Tunisia

.

The United States endeavored to contain Soviet influence and at the same time, for the same reasons of defending its interests, the spread of Arab nationalism in the Middle East and the Persian Gulf. During the Cold War, it opposed nationalization of the petroleum sector and any attempt was prevented by all means, including military coups and regime change. This is because ―U.S. companies produced about 50 percent of the Middle East's petroleum. Of Europe's crude oil imports in 1955, 89 percent came from that region‖17. The nationalization of these sectors therefore preventing major U.S. corporations from benefiting was perceived as a serious threat to American business and hegemony. This explains the importance of the region to the American economy and the persistence to

17Thomas G. Paterson, John Garry Clifford and Kenneth J. Hagan, American Foreign Relations: A history

maintain it in its sphere of influence. In 1953, when the nationalist Mohammad Mosaddegh planned to nationalize the Iranian oil resources, the United States, through the CIA, orchestrated a military coup to topple the the unfriendly regime and instal a pro-American government headed by Mohmmad Reza Pahalvi. This was arguably an important marker of the U.S. policy of containment with regards to national oil security. The end of the Cold War and the disappearance of the Soviet Union as a rival power did not put an end to U.S. eagerness to acquire and maintain a vital zone like the Middle East and North Africa. Containment and neo-containment of rivals in the rich-oil area have been the main U.S. policy goals in the MENA since the early Cold War. U.S. Iraq wars in 1990-1991 and 2003 in addition to Afghanistan in 2001 and the involvement in Arab uprisings in the 2010s were quests for oil and primacy, as much as for U.S. strategy presence, as it is examined in details in chapter two.

Rollback, although it appears as anti-thesis of containment as it is a regime change,18 is one major mechanism of containment initiated during the Eisenhower presidency; changing regimes secretly with the assistance of the CIA was carried out : in Egypt in 1952, Iran in 1953, Chile in 1973, and reportedly Egypt in 2013. The United States orchestrated and sponsored dozens of military coups and regime change operations during the Cold War and the New World Order then the War on Terror to contain vital areas within U.S. interests and intimidate other countries hostile to the United States. Regime change was exploited to enlarge U.S. influence and stop the regional and international powers from competing in these vital areas. Moreover, regime change was an intimidation to countries especially in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Comparable military coups and proxy wars carried out during the two phases of the Cold War and then the War on Terror reveal the continuity of containment from the 20th to the

18 Robert Litwak, Regime Change: U.S. Strategy Through the Prism of 9/11 (Washington, D.C: Woodrow

21st century, between the two U.S. wars and make the link with the Arab uprisings in the early 2010s. Such a strategy was developed to contain the spread nationalism embodied mainly in political Islam in the MENA during both wars in relation to defending the U.S. sphere of influence. This continuity will be the matter of my concern when revisiting twentieth and twenty-first century historiography and the post-Cold War U.S grand strategy notably during the War on Terror.

This system of alliances aimed at allying MENA countries within the U.S. sphere of influence was shaken during and after the Iranian Islamic revolution. When the United States ‗lost‘ Iran - one of its key allies in the region- this introduced the threat that it could lose other that embraced the same ideology of political Islam as an anti-American ideology. A second political earthquake occurred a generation later with the Arab Spring in the 2010s and the overthrow of the new vital U.S. allies. The situation became more complex with the subsequent empowerment of Islamic parties and their victory in the parliamentary and presidential elections in Tunisia and Egypt, suggesting that they could gain decisive influence in the MENA. The United States claims the mission to defend democracy and democratic elections around the world. If so, how would it balance values and interests in an increasingly strategic area where Iran has remained the primary rival since 1979?

In the post-Cold War, a neo-containment policy has developed since the mid-1990s to enhance U.S. primacy over the region and, to this end, to isolate the main regional threat to U.S. strategic influence, Iran. Political Islam and the War on Terror would end up by fitting into this framework. The United States is of course concerned with Russia‘s new post-Cold War expansionism, as well as the emergence of China as a superpower, these concerns will only be dealt with here to the extent that it influences these regional balance of power stakes.

The term ―neo-containment‖ first appeared in the early 1980s to designate the Reagan administration‘s intensifying tension with the Soviet Union.19 Then it was used in 1995 to depict a ―more modern and nuanced version of strategic (Cold War) containment‖20 which was deployed in the post-Cold War era. It was defined by the Economist in 1995 as ―not . . . an overarching strategy for dealing with an overriding

threat. But as series of mini-containments in response to the increasingly difficult Russia‖21. Another more recent definition of neo-containment is ―a revival of George Kennan‘s recipe for stopping subversion generated by the Kremlin‘s insatiable geostrategic hunger22.

Neo-containment strategies favored the United States in the immediate post-Cold War era but then the situation began to change in favor of rival powers, including Russia. While the United States focused on the War on Terror, China, Russia, and the Islamic Republic of Iran emerged to challenge the stability of the American Empire23. ―Russia has invaded Crimea and other parts of Ukraine and tried covertly to destabilize European democracies. China built artificial island fortresses in international waters, claimed vast swaths of the Western Pacific, and moved to organize Eurasia economically in ways favorable to Beijing. And the Islamic Republic of Iran has expanded its influence over much of Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen and is pursuing nuclear weapons‖24. In this context, preserving its footing in the MENA, the U.S. outpost towards the global East, has taken on ever greater importance. For the U.S, the major threat to its strategic interests and

19 Stephen Woolcock, ―US-European Trade Relations,‖ International Affairs Vol. 58, No. 4 (autumn, 1982):

610-624.

20 Bob Lo, Axis of Convenience: Moscow, Beijing, and the New Geopolitics (United States, Brookings

Institution Press, 2009 ) 242.

21 Ibid.

22 George Anglițoiu, ―Putinization and Neo-Containment,‖ Europolity Continuity and Change in European

Governance. 12.2 (2018): 179-190.

23 Christopher Layne and Bradley A. Thayer, American Empire: A Debate (New York: Routledge, 2007). 24 Michael Mandelbaum, ―The New Containment Handling Russia, China, and Iran,‖ Foreign Affairs. 98.2

supremacy in the MENA and especially to oil rich Iraq, to Israel and its neighbors, Syria and Lebanon. According to the logic of the Cold War doctrine, adapted to the MENA in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings and the triumph of Islamic parties, the Iranian Domino could inspire new Islamic revolutions and regimes.

Neo-containment, we contend, then, applies to containing Iran in the Middle East and to political Islam in Arab Spring countries which tended to quit the U.S. sphere of influence. It was also recommended by George W Bush‘s advisers before 9/11 as a new ‗grand strategy‘ to substitute the Clinton administration‘s declared strategic ‗mission‘ of democratic transformation25. Significantly, neo-containment needed to be articulated with the War on Terror during the Bush and Obama administrations then with the Arab Uprising period in the 2010s. These new foreign policy challenges, made conciliating the defense of U.S. strategic and economic interests, and at the same time its democratic values, even more complex. In this context, the objective of maintaining Arab Spring countries as defenders of U.S. strategic and economic interests rather than siding with Iran was an effort that was not an easy task for the U.S. Its policies at first seemed to waver and even be marked by some confusion.

Despite the difficulties, U.S. governments have encountered in finding the right policy measures and balance to implement it, neo-containment of the MENA has largely succeeded in benefiting the United States geo-strategically. At the same time, it has revived the Cold War antagonism between the United States and Russia over competition for influence in the region and especially since the Arab Uprising and within these countries. Iran‘s own ambitions and the War on Terror have further complicated the task of U.S. policy makers. Analyzing events in Tunisia and Egypt, the first two Arab Uprising

countries and that also gave rise to political Islam regimes, is key to understanding U.S. foreign policy in the MENA region.

Political Islam and containment

Political Islam denotes the political interpretation of Islam that is the use of the Islamic principles as the main source of the political practice. It is ―any interpretation of Islam that serves as a basis for political identity and action‖.26 The term is often used interchangeably with Islamism. Although the notion was created by the Egyptian scholar Hassan-al Banna in 1928, the term and practice remerged in the aftermath of the Six-Day War in 196727 when Arab Nationalism lost popularity and efficiency. It was the end of Nasserism, the main promoter of this movement and the 1967 War that ―opened new space for Islamism in the Arab world‖28. Arab Nationalism was an anti-imperialism ideology that grew hostile toward the West. It has been explained as a ―political movement that stands against western imperialism and colonization and in favor of the emancipation of the third World‖29 and especially, the Arab world. Gamal Abdel Nasser, the main founder and key figure of Nasserism and Arab Nationalism advocated an international non-alignment policy since the early 1950s. He retreated from being included in American and Soviet sphere of influence and support revolutionary nationalism in the Arab Muslim World. ―Revolutionary nationalism had to be both anti-capitalist and geared toward a special type of socialism‖30. This political ideology brought American hostility to Nassser and other Arab countries that followed the same path.

26 John O. Vall and Tamara Sonn, Political Islam: Oxford Bibiliographies online Research (Oxford

University Press, 2003) 3.

27Ibid.

28 Shadi Hamid, ―The end of Nasserism: How the 1967 War opened new space for Islamism in the Arab

world,‖ The Brookings Institution June 5, 2017, online, internet Jun.30, 2018. Available: https://www.brookings.edu .

29 Gerhard Böwering, Patricia Crone and Mahan Mirza, The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political

Thought (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2012) 385.

30 Federico Vélez, Latin American Revolutionaries and the Arab World: From the Suez Canal to the Arab

The Eisenhower Doctrine targeted it in the late 1950s and the 1960s; it “sought to contain the radical Arab nationalism of Egyptian president Jamal Abdel Nasser‖31. And

through economic, political and military means, what can be considered already as a regional version of containment aimed at a local rival, the United States aimed to restrain Nasserism in the Middle East. The policy failed to fully meet its objectives, however, as this ideology was transmitted to the major Arab Muslim World and even to Latin America.

Political Islam came not only as an opposition of Arab Nationalism but also as an alternative political ideology that began to emerge in the MENA in the 1970s and 1980s. Adherents to political Islam opposed the pro-Western rulers and worked on positioning themselves on the political scene. The Iranian Islamic revolution of 1979 was labeled as ―the coming of age of Political Islam‖32. Since then, Iran was, like China in 1949, ‗lost‘ and left the U.S. orbit. Iran had been a key U.S. ally in the MENA since 1953, when the CIA orchestrated a military coup against the nationalist Mohammad Mossadegh to install Shah Pahlavi, a pro-American ruler. U.S. policy was geared around the concern that MENA countries were likely to follow the Iranian revolution as Islamists there started to oppose and challenge their rulers.

Islamic-based governments and Islamic parties have been a matter of concern of U.S. foreign policy as they have been traditionally perceived as anti-American. The application of the containment policy to stop them from spreading thus became an imperative, though a complex one, to carry out. On the one hand, the notion of ‗political Islam‘ is essential to the War on Terror because its presence was a turned to the advantage of U.S. policy, another example of the ‗pretext of convenience‘. Although they themselves refuse to make any claim to radicalism, Islamic parties and governments are associated

31 Salim Yaqub, Containing Arab Nationalism: The Eisenhower Doctrine and the Middle East (The

University of North Carolina Press, 2005) 2.

32 John O Voll and Tamara Sonn, Political Islam: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide (Oxford

with extremism and radicalism by the U.S. political machine and therefore they have been contained, but not defeated and dismantled. This is because they are essential to justify the U.S. waging of the War on Terror33. On the other hand, when opposing its rise at all costs American diplomacy thereby lacks consistency with its own values towards democratically elected national leaders who adhere to religious precepts in Arab spring countries, notably Egypt and Tunisia. The problematical frame of neo-containment enters at this point. Is Islam in government, even democratically elected, meant to be ‗contained‘? Or just ‗political Islam‘, which is equated in U.S. foreign policy with ‗terror‘? How are the two defined, perceived and distinguished in U.S. foreign policy? How does 21st century U.S. policy frame its diplomacy and interests towards Islam in government? It is in this sense that U.S. policy towards the War on Terror and towards the Muslim world and Arab Spring governments are inexorably intertwined. What, in fact, is meant to be ‗contained‘? The Egyptian and Tunisian cases are exemplary to illustrate the commonalities and contradictions of U.S. diplomacy with regards to multiple interests in these policy areas.

As the spread of political Islam could endanger U.S. interests, a containment policy toward Iran and other threatening Arab states was the main priority in the region of U.S. governments. This strategy is backed to the Reagan administration in the 1980s and continued to the post-Cold war era. The United States advocated an anti-political Islam policy in the MENA. It was manifested in 1982 when the United States interfered to save the Lebanese President Camille Chamoun from being overthrown by the Islamists, thereby keeping the country within the United States sphere of influence. Moreover, the United States engaged their allies in the MENA to distance Islamists from political power. The crackdown of Islamists notably in Tunisia in the 1980s and Algeria in the 1990s best exemplify the U.S. rejection of political Islam. The Arab Spring in the 2010s then

33 Christine Chinkin and Mary Kaldor, ―Self-defence As a Justification for War: the Geo-Political and War

witnessed, through the initial reaction of Washington, the continuity of U.S. rejection of Islamic-based parties and governments.

Opposition to political Islam has remained a main component of its alliance system in the MENA region. The Islamists embraced anti-imperialist ideology in search of emancipation and economic and political independence. These ambitions ran counter to U.S regional interests and threatened to lead competitors like China and Russia to forge new alliances. To maintain its alliance system, the U.S. emboldened its allies through by implementing its policies through the major mechanisms of containment, through economic, military, diplomatic means.

What mattered for the United States, I argue, was not Islam as a religion or political Islam as such, but the preservation of its interests and alliance system that was threatened by such groups. ―This is not primarily because Iran is ‗Islamic‘ or ‗fundamentalist‘ but because Iranian nationalism, and the experience of Iran‘s mass political mobilization, represents the strongest challenge to the present configuration of Western interests and clients regimes‖34. Moreover, the Iranian model extended to other countries in the MENA. ―Islamist Ideology extends beyond Iran to include Palestinians, Lebanese, Egyptians, Sudanese, Tunisians, Algerians and others. All these share ‗anti-imperialism and anti-Americanism‘‖35. In response, the United States engaged the actions of the various governmental and non-governmental institutions, such as the department of State, the CIA, the Congress, USAID, to contain the spread and empowerment of political Islam in the MENA. In Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt, under the United States umbrella, Islamists were oppressed and elections were falsified. In April 1989, as the Islamic Party

Ennahda won around 17% of the total votes in the parliamentary election, President Ben

34 Joel and Joe Stork, Political Islam: Essays from „Middle East Report‟ (Berkeley, Calif: University of

California Press, 1997) 15.

Ali banned the party, jailed and exiled its members36. The Algerian election of December 1991 in which The Islamic Salvation Front gained 54% of the total votes37 was bloodier after the nullification of the FIS victory. The United States even claimed its responsibility for the intervention in MENA elections and notably the 1992 Algerian election38.

In this vein, how would the United States embrace and champion democracy if these groups came to power? The question was directly raised during the period studied here in light of Condoleezza Rize‘s speech in 2005 in Cairo on the American duty to spread democracy then the famous speech of Barack Obama at Cairo University in 2009 in which he promised a new phase with the MENA and the Muslim countries in terms of defending democracy. The first test was the Arab Spring when the Obama administration ended up, as we show here, back-tracking on this promise to engage in a continuity of the long-established grand strategy in the MENA. A study of U.S. response to the various phases of the Arab Spring in the MENA and especially in Tunisia and Egypt enhances the continuity thesis of primacy as the grand strategy to maintain U.S leadership and to renew the system of alliances and through the application of neo-containment.

The War on Terror was from neo-containment perspective ―selective with regards to goals, means and targets‖39. That is the United States was selective to contain specific countries to meet political goals and also took into account the cost, attempting to find the least expensive means for achieving them. In the final analysis, it prioritized stability over democracy: ―Stability is a more reasonable and achievable goal than democratization‖40. Without meaning to undertake a comprehensive comparative historical, political and

36 Rémy Leveau, ―La Tunisie du Président Ben Ali: �quilibre Interne et Environnement Arabe,‖ Maghreb

Machrek: Monde Arabe : Al-ʻālam Al-ʻarabī. (1989): 10.

37 Robert Mecham, From the Sacred to the State: Institutional Origins of Islamist Political Mobilization

(Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2006) 1.

38 Fawaz A. Gerges, America and Political Islam: Clash of Cultures or Clash of Interests? (Cambridge:

University Press, 1999) 76.

39 Glenn P Hastedt, American Foreign Policy: Past, Present, and Future (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

2018) 398.

economic analysis on this last topic, introducing this contextual and conceptual dimension will inevitably revise a number of American Superpower clichés inherited by the postwar period, notably the self-proclaimed American mission to defend ‗democracy‘ in all instances as a justification of maintaining its super-power status.

The dissertation’s main hypothesis

The thesis main hypothesis is that containment has been employed in the Cold War era in order to maintain American super-power status, beyond the former post-war sphere of influence, and enhance U.S. primacy at the expense of potential rival powers. Containment remains the main foreign policy axis which has been adapted to the wars that opened the 21st century and still going on.

The aim is to study U.S. foreign policy mechanisms applied to both wars, to test the notion of ‗neo-containment‘ in the post-Cold War era. Thus renewing with the Cold War doctrine, according this hypothesis, has found its application in the U.S. War on Terror as well as towards Arab Spring governments. In this context, the question to be answered and to which I will attempt to answer is how the Arab Springtime fits into the overall scenario of U.S. Diplomacy, focusing on two specific countries, Egypt and Tunisia.

The PhD setting

The dissertation‘s subject is immensely broad in time and place thus stetting the boundaries temporally and geographically is needed to answer its main research questions and test its main hypotheses.

Setting the temporal boundaries:

The dissertation surveys ‗the containment policy‘ as American Cold War strategies. The focus is put mainly on the War on Terror from 9/11 to 2008 and the Obama foreign policy toward the Arab Spring countries from December 17, 2010 to the late 2014.

Meanwhile, the argumentation extends forwards and backwards from 1945 to 2014 to follow the continuity or discontinuity of the same grand strategy despite the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. It highlights the hypothesis that the post-WWII American grand strategy based on primacy has not fundamentally changed. The late phase of the Cold War from 1980 to 1990 marked the peak and fall of the containment policy. President Reagan escalated tensions in his first term as he called for the implementation of ‗rollback the state‘ as a response to the 1970s détente, coining the Soviets as ‗the evil empire‘ in 1983, however then turned back to détente in his second term. His successor George H. Bush followed the same path during the transition period from the Cold War to the post-Cold War. His ‗New World Order‘ was based on deterring the potential threat to U.S. primacy and on the re-forging of the alliance system. This was manifested in the first Gulf War in 1991 and how the United States bolstered its alliance system on the one hand and damaged a potential threat to U.S. leadership in the Middle East and notably the rich oil countries, on the other.

The post-Cold War era could be divided into two main eras. The first extends from December 31, 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed officially to the 09/11. The interwar period - from 1991 to 2001- was an era of leadership crisis and search for a new containment policy and so, one might say, a new George Kennan. President Bill Clinton introduced the dual containment of Iran and Iraq as the main U.S. rivals in the MENA which, we argue, is a continuity of the Cold War containment. In the mid-1990s this policy was described as the ―neo-containment‖41, according to The Economist magazine. Major focus is placed on the important era between the post 9/11 and America‘s War on Terror in the MENA. It covers the President George W. Bush presidency and its main wars against Afghanistan and Iraq then the President Barack Obama presidency policy in the MENA

41 Bobo Lo, The Axis of Convenience - Moscow, Beijing and the New Geopolitics (Washington: Brookings

and notably during the Arab Spring countries. The main area of concern is the neo-containment policy and whether it has been applicable on the War on Terror then the Arab Spring or not.

Geographical boundaries

Although the thesis studies the MENA region as a key area to United States foreign policy concerns during the Cold War and War on Terror, it simultaneously covers the area of conflicts during the Cold War where the policy of containment was implemented either to distance the Soviet influence or to bring countries into, or back into, the American orbit. Europe, Latin America and Asia along with the Middle East and North Africa were subject to containment policy since the early Cold War.

The MENA typically includes Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Palestine, and Yemen, Ethiopia and Sudan42.Reference is made to the MENA region when the policy overrides all countries, despite the fact that the study of the containment policy in detail throughout the entire MENA is beyond the scope of this thesis. The focus is put on key areas such as Egypt, Iraq and Iran as a particular area of conflicts between the major powers and concern of the United States from the Cold War to the Global War on Terror eras. North Africa such as Tunisia, Algeria along with Egypt has witnessed political turmoil because of the political Islam and its relations with United States interests in the region. The Arab Spring, which occurred in the MENA region, is examined from neo-containment perspective and in relation to U.S. ‗habits‘ and grand strategy of ‗primacy‘. Tunisia and Egypt are the center of concern when dealing with the Arab spring in chapter four.

Methodology

The dissertation uses various primary sources which are linked mainly to the Cold War policy of containment. The first material is George Kennan‘s Long Telegram which was a secret cable sent from U.S embassy in Mosco in 1946 to the State Department. Later on it was published in Foreign Affairs Magazine under the pseudo X in 1947. This document was seen as the bible of the containment policy as it coined the expansionist policy of Stalin that it claimed was aimed at world domination and recommended a series of counter policies to limit the spread of communism worldwide. It set out the framework of containment as a grand strategy. The dissertation relies on the presidential and state department secretary speeches and position statements that are relevant to the main hypothesis. Other government sources are used to reveal the national security strategies such Truman NSC-68, George H Bush‘s 1992 DPG and George W Bush 2002 NSS. A direct access to the Library of Congress in Washington and several New York Libraries allowed use relevant archives such as ―Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States‖ in addition to declassified documents from the National Archives website. For accurate and concrete statistics, the USAID website also was fruitful to analyze data on U.S. economic aids to countries along various periods of time. A direct access to the headquarter of the USAID in Washington and interviews with high civil servants during my research study the United States in July 2015 allowed me to use analytical data and information provided by the USAID organization.

Much attention is devoted to revisiting Cold War and post-Cold war scholarship through the lens of neo-containment. The secondary sources studied include a wide range of various books, articles and interviews with specialists in the Middle East and North Africa studies along with War on Terror researchers in the United States and Tunisia. Authors and writers belonging to different schools of thoughts are taken into consideration.

This includes their work and also the intersection between academia and politics that is pointed out and analyzed with great precaution. One noteworthy element of continuity between the two U.S. ideological wars is the phenomenon of leading and influential historians in the early Cold War and then War on Terror becoming members of American presidential administrations. John Lewis Gaddis is a case in point, the most prominent historian in the Cold War in late 1970s and 1980s who later joined George W. Bush administration. He not only showed his admiration to Bush‘s preventive War but also rationalized the War on Terror. Other examples include the orthodox Cold War historians Herbert Fies, William McNeil and Arthur Schlesinger who were policy practitioners rather than acdemian in Truman and Eisenhower administrations to the extent that Feis was depecited as ―court historian‖43. This is an indication of the highly ideological nature of both U.S. post-WWII wars, just as of their schools of scholarship, that we attempt to deconstruct here.

To do so, the methodology adopts a close textual analysis of sources from a historical institutionalist and path dependency theoretical perspective. Data is also analyzed thanks to insight gained through interviews and collaborations with intellectuals and policy makers during and in the follow-up of the 2015 Study of the U.S. Institute (SUSI)44 on U.S. Foreign policy. The 120-hour course entitled ―Grand Strategy in Context: Institutions, People, and the Making of U.S. Foreign Policy,‖ renown U.S. foreign policy professors and specialists including Walter Russel Mead -the authors of books such as

43 Christos Frentzos and Antonio S. Thompson, The Routledge Handbook of American Military and

Diplomatic History: 1865 to the Present (Routledge, 2017) 170.

44 Study of the U.S. Institute (SUSI) on U.S. Foreign Policy examines how contemporary U.S. foreign policy

is formulated and implemented. The Institute includes a historical review of significant events, individuals, and philosophies that have shaped U.S. foreign policy. The Institute explains the role of key players in U.S. foreign policy including the executive and legislative branches of government, the media, the U.S. public, think-tanks, non-governmental organizations, and multilateral institutions. it was designed to foster a better understanding in academic institutions overseas of how U.S. foreign policy is formulated, implemented, and taught.

Power, Terror, Peace of War45 and Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World 46 – were the lecturers who contributed to this dissertation. The program was also an opportunity to meet and interview with political academic and practitioners at Bard College New York, – the Congress, the United Nations and the Department of States and the Pentagon which under the program had the opportunity to visit them and interact with key civil servant and policy makers.

The body of knowledge is then applied to studying policy evolution in order to evaluate whether one can determine either continuum – with high or low points– transitions or break of the containment doctrine, as applied through the mechanisms studied here, and leading up to the Arab uprisings in the early 2010s.

Dissertation outline

The dissertation is divided into four main parts:

Chapter one Literature Review presents a commented bibliography on how historians and political scientists have surveyed and analyzed the implementation of the containment policy in the two eras under study: the Cold War and the War on Terror. It sheds new light on traditional analyses of the major schools of thought, tracing the continuity of the intersection between politics and academia in the two eras. From historical prespective, this chapter examines the continuity or discontinuity of the same U.S. foreign policy since the onset of the Cold War until the ―Arab Uprising‖ in early 2010s.

The historiography of the Cold War strategic doctrine of containment is presented as a pivotal in shaping American domestic and foreign credos along five decades. The

45 Walter R Mead, Power, Terror, Peace, and War: America's Grand Strategy in a World at Risk (New

York: Vintage Books, 2013).

46 Walter R Mead, Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World (Burnaby,