the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development by

Hannah Highton Creeley B.A. in Individualized Study

New York University New York, New York

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2009

© 2009 Hannah Highton Creeley. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part.

Autho 2 oCI

K

Depaeient of Urban Studies and Planning(date of signing) Certified by

Ezra Haber Glenn Department of Urban Studies and Planning

7 Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by ,

Professor Joe Ferreira Chair, MCP Committee MASSACHUSETTS NT Department of Urban Studies and Planning

OFTECHNOLOGY

JUN 0

8 2009

ARCHVLIBRARIEES

the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development by

Hannah Highton Creeley

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 21, 2009

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning

ABSTRACT

Local housing authorities in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts currently manage over 50,000 state-aided public housing units on a consolidated, authority-wide level-a style of property

management that does not allow for the detailed monitoring or assessment of each property within a local housing authority's portfolio. The private real estate sector and federal public housing

authorities with more than 500 federal public housing units manage properties according to an asset management model in which the funding, budgeting, accounting, and management systems are conducted on a property-specific level. Recently adopted for federal public housing authorities, asset management is recognized as an effective tool for generating increased efficiency and accountability as well as improved financial and physical performance for individual properties.

Some academics and professionals argue that public housing is fundamentally different from the private sector and should not adopt a private sector business practice. The differences cited include unique resident populations (one is high-need, low-income and the other is independent and financially stable) and the objectives of each sector (one is considered a public service and the other is profit-driven).

This thesis investigates the models and mechanisms of two asset management models used in the public housing sector in order to best inform the Massachusetts Department of Housing and

Community Development on how to move towards an asset management model for state-aided public housing. First, strategic asset management employed by the social rented sectors of Europe and Australia is driven by four primary characteristics: market-oriented, systematic, comprehensive, and proactive. Second, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's asset

management model for federal public housing authorities is technical and process-oriented with a focus on five core reform areas: property-based funding, budgeting, accounting, management, and performance assessment. Each case is informative in creating an asset management model for Massachusetts state-aided public housing that will increase efficiency and accountability, place a focus on property performance, and end the stigma and isolation of public housing.

Thesis Supervisor: Ezra Haber Glenn, Lecturer in Community Development and Special Assistant to the Department Head, Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Thesis Reader: Amy Schectman, Associate Director of Public Housing and Rental Assistance, Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development

I would like to offer my sincerest gratitude to Ezra Haber Glenn, my thesis supervisor, and Amy Schectman, my thesis reader, for their guidance and support. Ezra has been an enthusiastic and involved mentor throughout my thesis process: he has pushed me to explore the deeper, harder questions; kept me motivated and on track; and provided rich perspectives and knowledge. Ezra always made time to meet to discuss my progress, questions, and roadblocks. I greatly appreciate Ezra's commitment and know that I have produced better work thanks to his dedication and encouragement. Amy's passionate and determined approach to preserving and improving the Commonwealth's public housing program is what first drew me to investigating a thesis topic with the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development. Over the past months I have been continuously impressed by her dedication to her work and beliefs. Amy has been

incredibly generous with her time and I am truly thankful for her insight, advice, inspiration, and friendship.

I would like to extend my deepest appreciation to all of those who provided me with the

opportunity to interview them for this research: Timothy Barrow, Gregory Byrne, Melanie Cahill, Thomas Collins, James Comer, Stephen Merritt, Gregory Russ, and James Stockard. Even with their busy schedules, all of the interviewees were immediately responsive and helpful, and generous with their time, knowledge, and experiences.

I would also like to genuinely thank everyone at the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development, each of who contributed to this thesis. I would like to specially thank Jessica Berman Boatright, Lizbeth Heyer, and Laura Taylor who together were an incredible team of guidance and support. Each of these remarkable women is an inspiration to me.

Thank you to my classmates, who have contributed greatly to my learning experience, introduced me to new perspectives and experiences, and made the long days and nights of work bearable.

Finally, a warm and loving thank you to my family and friends. Each of you has stood by my side with endless love and encouragement that has kept me strong and smiling. Your support has seen me through every good and bad day, high and low, success and failure, pleasure and disappointment, and bike accident-I am forever grateful.

Thank you all!

-5-CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... ...

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... ... 5

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES ... ... GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS ... ... 8

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ... ... 10

1.1 T hesis Structure ... .... ... ... ... 10

1.2 Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing: Ripe for Reform ... 11

1.3 T h esis M ethodology ... ... 13

CHAPTER 2: FEDERAL AND MASSACHUSETTS PUBLIC HOUSING PROGRAMS ... 14

2.1 Public Housing Funding Regulations... ... 15

2.2 T he Current State of Public H ousing ... 21

2.3 Asset Management Applied to Public Housing ... 23

CHAPTER 3: PUBLIC HOUSING: A HISTORICAL FRAMEWORK... ... 25

3.1 A Legacy of Homeownership ... 25

3.2 Government's Role in the Public Provision of Housing ... 27

3.3 Government Learns from Business Practices ... ... 31

3.4 HUD Moves Toward Asset Management for Public Housing ... 32

CHAPTER 4: ASSET MANAGEMENT: MODELS AND MECHANISMS ... 35

4.1 Asset Management in the Private Sector ... ... 35

4.2 Asset Management in the Social Rented Sector ... ... 36

4.3 Asset Management for Public Housing: HUD's Model ... ... 39

4.4 Opposition and Criticism Regarding Asset Management for Public Housing ... 44

4.5 Evaluating HUD's Asset Management Model ... ... 48

CHAPTER 5: CREATING AN ASSET MANAGEMENT MODEL FOR MASSACHUSETTS STATE-AIDED PUBLIC HOUSING ... ... 56

5.1 An Asset Management Model for Massachusetts Public Housing ... 56

5.2 R ecom m endations and N ext Steps ... 58

5.3 T he Q uestion of Funding ... 62

CHAPTER 6: C ON CLUSION ... 64

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 70

-6-Figure 1 Similarities between Strategic Asset Management Characteristics and

the Goals/Benefits of HUD's Asset Management Model ... 50

Table 1 Current Federal and Massachusetts Public housing Funding Regulations ... 20

Table 2 Characteristics and 'Indicators' of Strategic Asset Management ... 38

Table 3 Goals/Benefits and 'Indicators' of HUD's Asset Management Model ... 43

Table 4 An Evaluation of HUD's Asset Management mechanisms ... ... 51

-7-GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS

AMP Asset Management Project-under the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development's asset management model, public housing authorities can organize properties with similar characteristics into groups for easier implementation of asset management practices

ANUEL Allowable Non-Utility Expense Level-for Massachusetts state-aided public

housing, the amount of non-utility expense allowed for each local housing authority based upon the type/s of housing program administered

CIAP Comprehensive Improvement Assistance Program-for federal public housing, a

competitive program with annual awards for capital funds, introduced in 1980

CFP Capital Fund Program-for federal public housing, the system for allocating capital

funds to all public housing authorities regardless of size, introduced in 1998 with the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act

CGP Comprehensive Grant Program-for federal public housing, a formula funding

system for capital funds for larger public housing authorities, introduced in 1987

CPS Capital Planning System-a program proposed by the Massachusetts Department of

Housing and Community Development to help local housing authorities assess capital needs and plan for future capital improvements

DHCD The Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development-the

state department that oversees the state's 234 local housing authorities

EUM Eligible Unit Months-a public housing authority's number of viable occupied units

per month, used to calculate operating subsidy

GSD Harvard University's Graduate School of Design

HUD The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

LHA Local Housing Authority-the municipal body that administers and oversees a

Massachusetts state-aided public housing program

PEL Project Expense Level-a public housing authority's non-utility expenses used to

calculate operating subsidy

PHA Public Housing Authority-the municipal body that administers and oversees a

federal public housing program

-8-well-run public housing, completed in 2003

PFS Performance Funding System-the method used for calculating public housing

authority operating subsidies between 1975 and 2003

PUM Per Unit Per Month-a public housing authority's expenses are calculated on a per

unit per month basis

QHWRA The Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act-the Act that introduced a

number of major public housing reforms in 1998

UEL Utility Expense Level-a public housing authority's utility expenses used to calculate

operating subsidy

-9-CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 THESIS STRUCTURE

This introductory chapter begins with an examination of the current political climate of

Massachusetts state-aided public housing and investigates why asset management is being considered by the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development. The research

methodology used to gather information for this thesis is also summarized at the end of this chapter.

Chapter 2 presents the current state of federal and Massachusetts public housing programs with specific attention given to the regulatory systems of each program's operating and capital funds. The methods of allocating operating and capital funds have largely influenced the capabilities and

performance of the federal and Massachusetts public housing programs.

Chapter 3 considers three primary factors that have influenced the shape of public housing

programs in the United States: the praise for homeownership; the debate over government's role in the provision of housing assistance to those most in need; and government's adoption of a business-like approach to governing.

Chapter 4 evaluates the current models and mechanisms of asset management for public housing. The strategic asset management model utilized in the social rented sectors of Europe and Australia is informative in its objective-driven approach. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

-10-Development's model is a domestic example of the specific processes and systems of an asset management model for the public housing sector.

Chapter 5 draws upon the analysis and research findings to recommend an asset management model that is best fit for Massachusetts state-aided public housing. Consideration is given to next steps that the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development should take to

successfully move towards an asset management model.

Finally, Chapter 6 concludes this thesis with a brief summary of the main issues addressed in the preceding chapters, and the larger implications and consequences of adopting an asset management model for Massachusetts state-aided public housing.

1.2 MASSACHUSETTS STATE-AIDED PUBLIC HOUSING: RIPE FOR REFORM

Massachusetts is unique in that it is the only state that continues to manage a substantial public housing portfolio, with more than 50,000 units. Only three other states provide subsidy to state-aided public housing units: Connecticut, Hawaii, and New York. In recent years, these three other

state-aided public housing portfolios have been downsized: by means of transferring state units to non-profit organizations, private management companies, or by converting state units into federal public housing units. The Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development

(DHCD) is in a critical position in which it can either follow the example set by other states or it can lead the way in establishing innovative methods for managing public housing.

After sixteen years of neglect by Republican administrations, the Massachusetts state-aided public housing program has found renewed investment and commitment to providing decent and safe

-11-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

housing under the Governor Patrick's administration and Amy Schectman, DHCD's newly appointed Associate Director of the Division of Public Housing and Rental Assistance. With the support of Governor Deval Patrick and DHCD Undersecretary Tina Brooks, Amy Schectman convened the Real Cost Task Force to conduct a study of the actual cost of operating well-run public housing in Massachusetts. The Task Force, comprised of a number of local housing authority officials, scholars, and non-profit and private sector professionals, completed the study and

presented their findings in The 'Real Cost' of Operating Massachusetts Public Housing: Anaysis and

Recommendations (2008). In addition to estimating the actual cost of operating well-run state-aided

public housing, the final report recommends that DHCD identify, evaluate, and aggressively pursue all opportunities for cost savings and systems improvements to reduce the need for state subsidy. In the time since the study, DHCD has identified a number of cost savings and systems improvements including adopting an asset management approach to operating and monitoring public housing.

Briefly defined, asset management is a property management tool adopted from the private sector that requires property owners to monitor and report on the financial, physical, and management performance of individual properties within a portfolio. If applied to state-aided public housing, asset management would convert the current operating and monitoring systems from a consolidated,

authority-wide level to a property-specific, detailed level. In line with the Real Cost Task Force's recommendations, asset management is a business tool that could help DHCD realize a number of cost saving strategies while helping LHA's increase efficiency and accountability and also realigning public housing with the larger field of affordable housing.

The introduction and consideration of asset management for state-aided public housing has come at an opportune time as DHCD explores other methods of focusing on improving property conditions

and performance levels. DHCD is currently implementing a Capital Planning System that will help local housing authorities (LHAs) better identify and plan for capital improvement needs. Similar to asset management, the Capital Planning System is designed on a property-specific level so that LHAs can more closely realize a property's capital and maintenance needs. Furthermore, DHCD is also proposing a Self-Assessment tool so that LHAs can better evaluate their portfolio's fiscal and physical performance. If these initiatives are introduced in cooperation with an asset management model, LHAs will have the property-specific information and knowledge necessary to examine each property's performance rather than being limited to a consolidated, authority-wide lens.

The political climate introduced by Governor Patrick's administration and DHCD's other current systems improvement proposals establish an opportune environment for the implementation of an asset management model for state-aided public housing. In addition, DHCD can learn from other asset management models, both abroad and here in the United States, that have been applied to the public housing sector.

1.3 THESIS METHODOLOGY

The research methodology to gather data for this thesis consisted of a literature review and a number of interviews. The literature drew upon various sources including books, scholarly articles, professional reports, government documents (policy memoranda, federal register notices, regulatory codes, and legislative documents), and websites. The interviews engaged state and federal

government officials and scholars and practitioners in the housing field. The interviewees were identified and contacted from literature, academic, and professional references. Each interviewee granted permission to use their identity information in this thesis.

-13-CHAPTER 2

FEDERAL AND MASSACHUSETTS STATE-AIDED PUBLIC HOUSING

The United States federal public housing program has grown substantially since its inception in 1937. Introduced to create jobs after the Great Depression, federal public housing was originally conceived as a temporary housing assistance program (Marcuse, 1986). However, the need for subsidized housing has steadily increased over the course of several decades requiring the federal government to reassess the means of providing decent and safe housing'. Today, the federal program is comprised of over 3,300 public housing authorities (PHAs), providing housing to approximately 1.2 million households (HUD, n.d.c). In 2008, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) spent $4.2 billion in public housing operating funds and $2.02 billion in capital funds (HUD, n.d.b).

Massachusetts was one of the first of only a small number of states to provide an exclusively state-funded public housing program. In 1948, in response to the post-war affordable housing shortage, more than 15,000 units of family housing were constructed in four years. In 1954, Massachusetts set another precedent by constructing more than 32,000 units of state-aided housing units for the elderly (Regan & Stainton, 2001). These family and elderly units are now over fifty years old and

suffer from inadequate maintenance and modernization primarily due to a lack of sufficient funding. Today, Massachusetts' state-aided public housing inventory totals 49,550 units and makes up almost 25% of the affordable housing units in the state's subsidized housing inventory (CHAPA, 2008a). 1 See Chapter 3 for a detailed look at the roots of the federal pubhc housing program.

-14-The state public housing program is administered by 234 local housing authorities (LHAs) which are overseen by DHCD.

2.1 PUBLIC HOUSING FUNDING REGULATIONS

The particular funding regulations governing the federal and state public housing programs are of critical importance. The source and means of appropriating operating subsidies and funds for capital improvements greatly impacts a housing authority's financial and physical performance. The

following is an outline of past and current funding systems for the operating and capital funding systems of both federal and Massachusetts public housing programs.

Federal Public Housing--Operating Fund. Before the early 1960s, PHAs received no federal operating

subsidies, relying solely on the rents collected from tenants to cover operating expenses. After a brief period of experimenting with various subsidy schemes, HUD instituted the Performance Funding System (PFS) in 1975. According to PFS, a PHA received an operating subsidy that was the difference between a formula-determined "allowable expense level" and what was collected in rents. The allowable expense level was meant to reflect what a well-run housing authority would spend on

operations, based on a study of a small sample of agencies conducted in the early 1970s and updated annually to account for inflation.

The PFS required PHAs to rely on annual appropriations for their operating subsidies. A major criticism of the PFS is that operating subsidies are based on outdated funding levels and do not account for the actual cost of providing an adequate level of management and maintenance services. In recent years, the federal funding amounts had become increasingly unpredictable. Since the early

1990s, operating subsidies have been funded at 100 percent of the HUD-estimated levels only twice

-15-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

while other years the funding levels range from 89% to 99.5% (Byrne & Day & Stockard, 2003). The consistent lack of operating subsidies raised concerns about the accuracy of the PFS funding system and lead to questions regarding program performance and the willingness to invest in a public program that has traditionally struggled to gain majority support2.

In response to concerns about the PFS and other issues surrounding the federal public housing program, the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act (QHWRA) was signed by President Clinton on October 21, 1998, marking the start of major reforms for federal public housing.

QHWRA efforts include: reducing the concentration of poverty in public housing; protecting access to housing assistance for the poorest families; raising performance standards for public housing agencies; and supporting HUD management reform efficiencies through deregulation and program consolidation (HUD, n.d.e). Regarding federal funding regulations, QHWRA called for a

replacement of the PFS and required new formulas for both the operating and capital funds.

HUD's efforts to establish a new operating fund formula revealed a substantial lack of data on what it should cost to operate well-run public housing. To resolve this issue, HUD contracted with Harvard University's Graduate School of Design (GSD) to conduct a study about the actual cost of operating well-run public housing. The Public Housing Operating Cost Study (PHOCS) was presented to HUD in 2003. The study established a cost model to determine how much it should cost to operate a public housing property. GSD conducted extensive statistical and field analyses to test and evaluate the cost model. The cost model produced ten variables, or determinants of costs, each with a

separate "coefficient" that indicates the variable's unique impact on costs (holding all other costs

2 See Chapter 3 for more information regarding the challenges of introducing a federal public housing program.

constant). The ten variables are: geographic; central city; clientele; property size; building type; bedroom mix; percent assisted; property age; neighborhood poverty; and ownership type.

The cost model established in the PHOCS is a primary component of HUD's new operating fund formula. The formula calculates operating subsidy as the difference between a property's formula expense and formula income. If a property's formula expense is greater than its formula income, then the property is eligible for an operating subsidy. The formula expense is an estimate of a property's operating expense and is determined by three components: Project Expense Level (PEL), Utility Expense Level (UEL), and other formula expenses (add-ons). The PEL is a model-generated estimate based on the GSD study and estimates operating cost based on the property's specific characteristics (i.e., the ten cost variables). The three components of formula expense are calculated in terms of per unit per month (PUM) amounts and are converted into whole dollars by multiplying the PUM amount by the number of eligible unit months (EUMs). Formula income is an estimate

for a property's non-operating subsidy revenue. A PHA's formula amount is the sum of the three

formula expense components and is calculated as follows:

{

[(PEL multiplied by EUM) plus (UELmultiplied by EUM) plus add-ons] minus (formula income multiplied by EUM) } (HUD, 2002).

Federal Public Housing Proram-CapitalFund. In 1968, HUD began funding repairs and renovation to public housing properties under a series of modernization programs. One of these modernization programs was the Comprehensive Improvement Assistance Program (CIAP), established in 1980. The CIAP was a competitive program with annual awards that provided capital funds for the comprehensive modernization of a development. A second program was the Comprehensive Grant Program (CGP), enacted by the Housing and Community Development Act of 1987. The CGP provided a formula funding method to meet the capital needs of larger PHAs rather than require

-17-Creating an Asset Management Modelfor Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

them to compete for funds. The CGP marked a substantial change in HUD's approach to capital funding in that it provided more predictable annual funding and enabled larger PHAs to make short-and long-term modernization plans (HUD, 2008).

The QHWRA completely revised the means for allocating capital funding to PHAs by consolidating prior capital fund programs (e.g., CIAP, CGP) into a single formula grant known as the Capital Fund Program (CFP). A critical change of the CFP is the new formula that distributes capital funds

to all PHAs regardless of size3. The CFP permits PHAs to use their capital funds for financing

activities, such as debt service payments and other financing costs, for the development and modernization of public housing units. The CFP also requires that PHAs create a Five-Year Plan and Annual Plan with resident participation to serve as operations, planning, and management tools for PHAs (HUD, 2008). HUD's FY2008 Citizens' Report states that over 3,100 PHAs received capital funds with an average grant amount of $750,000 for improvements such as the development, financing, and modernization of public housing units and for management investments (HUD, n.d.a).

Massachusetts State-aided Public Housin--Operating Fund. Massachusetts provides operating subsidies to

LHAs to cover the difference between tenant rents and operating costs. The state began to provide operating subsidy in the early 1970s when rental income was no longer sufficient to cover operating expenses as a result of declining tenant incomes and state legislation that limited tenant rent to 25% of their income.

3 The Capital Fund formula mandated by the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act was developed through negotiated rule making. For more information on the development and details of the Capital Fund formula, see Qualiy Housing and Work Responsibility Act (QHWRA) and the Capital Fund, Chapter One. Pp 4.

<http://www.hud.gov/utilities/intercept.cfm?/offices/pih/programs/ph/capfund/cplqhwra.pdf>

-18

LHAs in Massachusetts are provided with operating subsidy according to the following regulations: (i) regarding utility costs, LHAs are funded dollar-for-dollar for actual expenses; (ii) for non utility operating costs, LHAs are assigned an Allowable Non-Utility Expense Level (ANUEL), based on

the type of program4; (iii) a LHA's utility costs and its ANUEL are added together to obtain a total

allowable operating cost figure. From this total amount, a LHA subtracts projected rental income and other revenue; the resulting difference represents the LHA's eligible operating subsidy (Stockard et al, 2005).

Massachusetts State-aided Public Housing -Capital Fund. In terms of modernization and capital

improvement funding, the state's approach is a competitive funding round to make awards from periodic bond bills. In order to have new projects considered for funding, LHAs must submit

reports to DHCD presenting new modernization and capital projects. DHCD then categorizes and ranks the submissions to determine which will receive funding awards. The design of the capital fund forces DHCD to implement a subjective ranking system of awarding capital funds that often leads to situations in which some LHAs do not receive awards for a given bond bill period because

their needs are of comparatively lower priority or do not fit adequately into determined categories. Furthermore, state capital funding levels funds are unpredictable from one year to the next due to the unstable fiscal environment impacting all government agencies and programs. LHAs that receive no award can make no capital improvements, unless there is an emergency or available reserve

funds, until the next bond bill is approved and another round of project submissions begin.

4 Massachusetts state-aided public housing provides housing assistance via four program types: Chapter 667 is elderly housing; Chapter 200 is veterans family housing; Chapter 705 is family housing; and Chapter 689 is special needs housing.

-19-Creating an Asset Management Modelfor Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

DHCD is aware of the flaws of the current award system for capital funds and is working towards a new capital planning and funding system. The Capital Planning System (CPS) is designed to help LHAs identify capital needs and plan for future capital improvements. Funding for capital

improvements will be based upon an LHA's submitted CPS reports and will serve as a predictable funding system so that LHAs can move confidently forward with their CPS projections. The implementation and success of the CPS and capital funding system is dependent upon securing a steady funding stream from the state legislature.

Table 1 below summarizes the funding regulations governing the operating and capital funds for the federal and Massachusetts public housing programs.

Table 1: Current Federal and Massachusetts Public Housing Funding Regulations

Operating Fund Capital Fund

Property-level formula funding: The Capital Fund Program

{[(Project Expense Level X (CFP) provides formula

Eligible Unit Month) + (Utility funding to all PH-As regardless

Federal Public Housing Program Expense Level X Eligible Unit of size. PHAs must complete a

Month) + add-ons] -(formula Five-Year Plan and an Annual

income X Eligible Unit Plan.

Month) }

Formula funding to cover Competitive funding rounds to

difference between rents and make awards from periodic

costs: (i) utility costs funded bond bills. LHAs apply for

dollar-for-dollar of actual costs; capital funds and applications

(ii) non-utility costs limited by are ranked by DHCD

the Allowable Non-Utility according to priority and need.

Massachusetts State-aided Public Expense Levels (ANUELs); (iii)

Housing Program utility costs + ANUEL

determine a total allowable operating cost figure; (iv) final operating subsidy calculated by subtracting rental and other income from total operating

costs.

20

2.2 THE CURRENT STATE OF PUBLIC HOUSING

Public housing in the United States began in the 1930s and 1940s to create jobs after the Great Depression and to house the working class. By the 1960s, public housing's resident population experienced a major shift': instead of serving the working class, public housing now targeted those most in need-minorities and those with very low incomes. As the white working class families moved out of public housing and into the newly constructed suburbs, public housing became

stigmatized as "the projects" and was increasingly regarded as "housing of last resort" (Curley, 2005: 105). This unfortunate stigma has largely shaped the political and social regard for public housing in the past several decades. The stigmatization of public housing has led to two trends that have greatly influenced the present conditions of both the federal and Massachusetts state public housing

programs: (1) years of insufficient operating subsidies and a lack of capital investment; and, (2) an isolation from the larger realm of non-profit and private real estate business sectors.

Both federal and Massachusetts public housing programs have recently suffered through several years of disinvestment. On the federal side, PHAs have attempted to operate well-run federal public housing with the inadequate operating subsidies calculated by the PFS formula. In Massachusetts, public housing has struggled through several administrations of under funded operating subsidies. Through most of the 1990s, LHAs in Massachusetts were repeatedly required to artificially depress their budgets to effectively minimize operating deficits thus justifying the continuously low levels of appropriated operating subsidy (DHCD, 2008b). During these years, LHAs were receiving an average of only 59 percent of the estimated actual cost of operating well-run public housing

programs6.

5 See Chapter 3 for more information about the political and social histories of public housing in the United States.

6 59 percent calculated using information identified in A Study of the Appropriate Costs for State-Funded Public Housing in

Massachusetts (Stockard et al, 2005). The report indicates that the current (in FY2005) average Allowable Non-Utility

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

Due to the lack of funding, housing authorities have been unable to adequately maintain and manage the properties in their portfolio. Housing authorities are not poorly run as a result of incompetence or carelessness; rather, federal and state funding regulations and annual appropriations did not enable housing authorities to commit the time and attention necessary to provide decent, safe, and

attractive living environments. Furthermore, public housing authorities have been criticized for being too focused on process rather than product. Yet, it is well known that under funded government programs of any variety are confined by numerous constraints. Housing authorities have often been limited to simply meeting the stated requirements and working within bureaucratic red tape rather than dedicating time and energy towards improving their housing stock. If housing

authorities were to redirect their efforts towards improving the assets, the likely result would be a failure to comply with the required processes and rules. Thus, the lack of funding and the

bureaucratic constraints imposed upon government programs have left federal and state public housing authorities with a deteriorating housing stock and a staff that is focused on process rather than product.

Since its inception, public housing has existed in isolation from the private real estate sector. The nation's federal public housing stock was purposefully built to be easily distinguished from private housing and it explicitly served only those people who could not secure housing on the private market. Being a government program with insufficient funding and serving a very low-income population effectively separated public housing from the private sector. Public housing's stigma as "housing of last resort" has held strong even through recent capital improvements and efforts to decentralize poverty.

Expense Level (ANUEL) is $202 per unit per month. The study finds that the actual cost of operating well-run public housing is an ANUEL of $340 per month. Using this information, we can calculate that $202 is 59 percent of $340.

22

Isolation from the private real estate sector has been detrimental to public housing in several ways. First, the segregation of the sectors further pushed public housing into the bureaucratic processes of being a public agency. Second, public housing authorities have not been able to benefit from new technologies and improved business practices for operating real estate because they do not

communicate with the non-profit or private real estate sectors. Third, the social and psychological stigma that is a result of the isolation from the private real estate sector is often painful and injurious to residents. A home is a person's foundation and support; therefore, if that home is publicly

regarded as a lesser product, then the person is more likely to feel inadequate himself. Kwak and Purdy (2007) comment on this issue in their article "New Perspectives on Public Housing Histories in the Americas": "People's notions of housing, their own and others', centrally shape their larger ideas about neighborhoods, towns, and cities. Dwellings, as Richard Harris writes, have a deep personal and ideological significance for people: 'For better or worse, we spend a lot of our lives at home and we care a lot about how we are housed"' (Kwak & Purdy, 2007: 360).

2.3 ASSET MANAGEMENT APPLIED TO PUBLIC HOUSING

Recent literature and studies prescribe an asset management approach to operating public housing as part of a solution to the challenges outlined above (Stockard et al, 2003 & 2005; Byrne et al, 2003; Smith, 2007; Bobb & Husock, 2001). Briefly, asset management is a property management tool adopted from the private real estate sector and can be summarized as "identifying, valuing, and periodically monitoring an LHA's assets, and incorporating that process-and the information it generates-into the agency's planning, decision-making, and operations" (Smirniotopoulos, 1999:

12).

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

The consideration of asset management for public housing came to the forefront with GSD's

PHOCS prepared for HUD and published in 2003'. In addition to developing a new formula to

calculate federal operating subsidy appropriations, the study recommends that HUD implement asset management practices similar to common private real estate business practices. The study finds that within PHAs "the focus is on the organization and not the properties; there is no analysis of the

financial performance of individual properties; and, there is no evaluation of a property's physical appearance, curb appeal, or general presentation, a fundamental construct in property management" (Stockard et al, 2003: 89). The study recommends that HUD require PHAs to adopt an asset

management model to increase PHA efficiency and accountability while enabling strategic decision-making and future planning.

7 See Chapter 2, Section 2 for more information regarding the PHOCS.

24

In order to best understand public housing's current position, it is important to analyze the key factors that have shaped the program. First, the country's overwhelming preference for

homeownership has cast a shadow upon those people who are unable to secure housing for themselves and has prevented a determined commitment to the public provision of housing. Second, the country has persistently questioned what the government's appropriate role is regarding issues of social equity. In consideration of public housing, the opposition to government

intervention has greatly influenced the program's goals. Third, there has been an ongoing debate regarding the most efficient method of organizing and operating a government agency: one side

argues that government agencies must adhere to stricter regulatory processes while the other side argues that government agencies can benefit from implementing the more efficient and streamlined processes of private business. The country's public housing program has been predominantly run as

a bureaucracy. The recent movement towards asset management marks the introduction of a business tool to the country's public housing sector.

3.1 A LEGACY OF HOMEOWNERSHIP

Individual ownership of land and home has been an overwhelming ideal and formative goal in the United States since the mid-18th century. The country's founding fathers envisioned an egalitarian

society characterized by independence and freedom for the whole citizenry. The equal distribution

-Creating an Asset Management Modelfor Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

of productive property was essential to securing such liberty (Daly, 2008). The government would be limited in its power and would act primarily to uphold this vision of society. Ownership of land was a man's inalienable right and was critical to his engaging in civil society and pursuing happiness.

The emergent ideal of the "yeoman farmer" gave birth to a national ethos that espoused the integrity of working to sustain one's self and family. In Notes of the State of Virginia, published in 1785, Thomas Jefferson wrote "Those who labor in earth are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people... Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example." Individuals who were unable to rely on their own land and labor were considered dependent, and "Dependence begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition" (quoted in Vale, 2000: 94).

As early as 1862, the federal government enacted legislation to encourage ownership and ostensibly provide for the equal distribution of productive property. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave

applicants a freehold title to a minimum of 160 acres of undeveloped land west of the thirteen colonies. In the years since, the federal government and the private housing market have

collaborated to promote homeownership. The federal income tax legislation of 1907 established tax deductions for property taxes and interest on home mortgages. In 1920, the U.S. Department of Labor paired with the National Association of Real Estate Boards and other private home industry groups to launch the "Own Your Own Home" campaign (Vale, 2000). The government's efforts shifted from propaganda to legislation with the creation of the Homeowners Loan Corporation in 1933 and the Federal Housing Administration in 1934. Both programs encouraged homeownership by insuring mortgages for construction and protecting lenders from drops in mortgage values and, thus, essentially shifting the risk of nonpayment and foreclosure from the private institutions to the

26

federal government. The National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956 is considered the final touch to enabling the private home industry and citizens ripe for homeownership.

3.2 GOVERNMENT'S ROLE IN THE PUBLIC PROVISION OF HOUSING

The insistent promotion of homeownership and the opposition to government interference greatly impacted the formation of public housing. The federal government did not address the need for

better housing until the effort could be paired with another national issue-the need for

employment opportunities after the Great Depression. The legislative language of the United States Housing Act of 1937 made this dual objective clear: "to alleviate present and recurring

unemployment and to remedy the unsafe and insanitary housing conditions and the acute shortage of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low income..." (United States Housing Act, 1937). The federal government was hesitant to address the country's housing issues due to the larger debate concerning the government's role and responsibility regarding social and economic issues-is it better to have welfare state or a laissez-faire approach?

The country's founding fathers would argue that providing public housing is the government's responsibility to successfully restore an equal balance of productive property. Though many conservatives opposed public housing in favor for a laissez-faire government, it was clear that an unresponsive government would only worsen the country's socio-economic condition. In his article "What Would Jefferson Do? How Limited Government Got Turned Upside Down" (2008), Daly

states, "...limited government is not an end itself, but the instrument of a particular vision of society, an egalitarian vision. It was a social vision in which extremes of wealth and poverty did not exist..." (Daly, 2008: 5). Furthermore, "The republic social objective of securing a relatively equal distribution of productive property was paramount in their [the founding fathers'] thinking about

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

what government should or should not do" (Daly, 2008: 5). Viewed in this regard, the creation of public housing was acted as a necessary balancing tool to support those citizens who were unable to

secure a home.

Though the Housing Act of 1937 established the public provision of housing, the opponents of public housing strongly influenced the nature of the program. The private home building industry, and others who believed wholeheartedly in the virtues of homeownership, argued that the

government's involvement was socialist and would interfere with the nature of private market competition (Marcuse, 1986; Bratt, 1986; Vale, 2000). As a concession to the private housing

industry, the legislation included a provision that required the destruction of one inadequate dwelling unit for every new unit created. This provision ensured that the construction of public housing would only replace substandard units without increasing the total number of housing units available so as to not saturate the market and reduce rents.

In addition to the opposition from the private home building industry, the Red Scare and

McCarthyism of the 1940s inspired a movement against the public provision of housing. As noted by Kwak and Purdy (2007), Don Parson argues that "the Red Scare was an assault on social-democratic reform and the Left-liberal popular front that ushered in public housing during the Great Depression" (Kwak & Purdy, 2007: 365). Parson drew upon numerous local media sources of the time in Los Angeles to examine the trends and changes in the popular attitude toward public housing. He finds that "Los Angelenos moved from the 'ridicule and disdain' of red-baiting tactics in 1945 to a general dislike of public housing and its 'undesirable socialistic qualities'" (Kwak &

Purdy, 2007: 365).

28

Since its inception and in the decades since, public housing has consistently been regarded as a temporary solution or way station for people who need a little help along the path to

homeownership. After the Depression, the Housing Act of 1937 aimed to ease social unrest and create jobs while specifically not interfering in the private housing market. The program's targeted population was the temporary, "deserving" poor-the "submerged middle-class" (Friedman,

1968)-and not those "undeserving" poor with no means to pay rent. To distinguish itself from the rest of the country's housing stock, the character of the federal public housing constructed was intentionally unsound in structure and austere in appearance.

After World War II, a resurgence of legislation favoring homeownership led to the dramatic shift in the population served by public housing. The submerged middle class and others benefited from the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration programs that offered mortgage insurance and guarantee programs to new homebuyers. As a last push to promote and veritably

require homeownership, the 1949 Housing Act limited those eligible for housing assistance to only very low-income citizens. The Act required that the highest rents be 20 percent lower than the lowest rents for decent housing in the private sector and authorized the eviction of above-income

families.

After every potential homeowner had vacated public housing, a new population of mostly minorities and the very poor moved into public housing. These new tenants were not on the road to

homeownership but, rather, were very much in need of any aid being offered. The government recognized this difference between populations and responded with a combination of total neglect

and sporadic social support services. Public housing's neglect is characterized by insufficient

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

funding, the isolation and segregation of housing types, and President Nixon's moratorium8 on all

federally subsidized housing programs in 1973. In the early 1990s, government began to pay more attention to the dire state of public housing by introducing a number of social support initiatives. These initiatives again confirmed the government's consideration of public housing as a temporary solution-the provision of a shelter rather than a home. Programs such as the Family

Self-Sufficiency program introduced in 1990, Moving to Opportunity in 1992, and Moving to Work in 1996 each proposed to disperse and alleviate poverty using various methods. Yet, the government's bottom-line goal was to encourage those residents could to leave public housing to do so thus becoming self-sufficient.

Today, public housing faces a number of pressing issues: a housing stock that requires a significant amount of maintenance and repair; persistently low levels of federal subsidy; and the need to provide additional support services for residents. In his essay "Housing Policy and the Myth of the Benevolent State" (1986), Marcuse examines the concept of the benevolent state in reference to the

U.S.'s housing policies. The foundation of a benevolent state is the belief that "the government acts out of primary concern for the welfare of all its citizens, that its policies represent an effort to find solutions to recognized social problems, and that government efforts fall short of complete success only because of lack of knowledge, countervailing selfish interests, incompetence, or lack of

courage" (Marcuse, 1986: 248). Marcuse finds that, in consideration of the U.S.'s housing policies throughout the years, the government has not always acted as a truly benevolent state. In its current state, the federal government may be attempting to solve too many problems at once-providing housing while also offering social support services. At this point it would be in the government's

8 President Nixon impounded congressionally appropriated funds for all new federally subsidized housing in January 1973. The impoundment of housing funds was justified by the administration "on the grounds that subsidized housing programs were ineffective and uneconomical." Lamb, Charles M. 2005. Housing Segregation in Suburban America since 1960: Presidential and Judicial Politics. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. Pp. 157.

30

and the public housing residents' best interests to reevaluate to the goal of public housing: to provide housing for individuals and families who are unable to compete in the private housing market. In addition, the government must recommit to its mission by focusing on the physical condition of the public housing stock.

3.3 GOVERNMENT LEARNS FROM BUSINESS PRACTICES

Implementing an asset management model for the operation and management of public housing is one possible means of recommitting to providing decent and safe housing to low-income citizens. Private real estate businesses have long utilized asset management as a tool to efficiently and effectively manage real estate.

Whether or not the government should adopt an asset management model based upon private business practices raises a larger debate about how a government should function. In Bureaucracy:

What GovernmentAgencies Do and Why They Do It (1991), Wilson finds that government agencies are fundamentally different from private businesses and, thus, it may not be possible or appropriate for government to adopt private business practices. For example, government agencies focus on the various constraints and regulations they must operate under while businesses are profit-driven and focus on the bottom-line. While implementing certain business practices in government agencies would not be a viable option (e.g. procurement processes), asset management is a standard means of managing real estate that proposes to aid in the transformation of this country's approach to public housing.

In recent years, a number of state and local governments have transferred traditionally public responsibilities to the private sector. Privatization is defined as "the use of the private sector in the

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

provision of a good or service, the components of which include financing, operations (supplying, production, delivery), and quality control" (Kosar, 2006: 1). The privatization of public services has emerged for a number of reasons including fiscal stress and concerns regarding information, monitoring, and service quality (Hebdon & Warner, 2001: 315). In terms of privatization proposals

for the federal government, President George W. Bush supported the privatization of military housing and the creation of a Medicare prescription drug benefit to be provided by private firms (Kosar, 2006: 1). Briefly, advocates of privatization argue that "private firms can provide goods and services 'better, faster, and cheaper' than government" (Kosar, 2006: 6).

It is critical to note that the introduction of asset management to public housing programs in the United States is not an act of privatization. Rather, asset management is a private sector business tool that may be effective and beneficial to the public housing sector. The responsibility of providing housing assistance is not being transferred to the private sector, nor is a private sector profit-driven mentality being adopted with asset management. The recent privatization trend may have informed the proposal of adopting an asset management model for public housing but it is by no means a proposal for wholesale privatization.

3.4 HUD MovES TOWARDS ASSET MANAGEMENT FOR PUBLIC HOUSING

HUD's conversion to asset management is the result of a greater realization that the need for public housing is not going to disappear and that the purpose of the program must be reevaluated and

commitment reinstated. As examined earlier, the federal public housing program was originally regarded as a temporary program to resolve a short-term job and housing shortage. As the need for housing assistance steadily increased throughout the decades and public housing's demographics

shifted to a majority very-low income resident population, it became evident that HUD should

32

invest in the program's foundation, the physical infrastructure, in order to provide decent and safe housing to those in need of assistance.

As previously noted, the QHWRA was enacted in 1998 in response to the growing tensions and conversations about the failure of public housing. The Findings and Purpose section of the

legislation states, "Congress finds that there 1) is a need for affordable housing; 2) the government has invested over $90 billion in rental housing for low-income persons; 3) public housing is plagued with problems; 4) the Federal method of oversight of public housing has aggravated the problems;

and 5) public housing reform is in the best interests of low-income persons" (Hunt, Schulhof, & Holmquist, 1998: 2). The goals of the QHWRA include deregulating PHAs, providing more flexible

Federal assistance, and increasing PHA accountability and effective management.

Harvard University presented the PHOCS to Congress and HUD in 2003. In addition to establishing a cost model to determine how much it should cost to operate well-run public housing, the final report recommends that HUD require PHAs to convert to asset management. The report states, "Public housing has existed since its inception in isolation from the rest of the housing development and management world. This isolation has led to an unhealthy reliance on HUD as its measure of performance (please the funder) instead of reliance on consumer preference and market value

(please the client, maximize return)...PHAs operate like public agencies and not like real estate businesses, managing under extremely centralized arrangements that run counter to good business practice" (Stockard et al, 2003: iv). For these reasons GSD made the following recommendations (in addition to adopting the cost model): HUD should move in the direction of project-based

budgeting, management, and funding of public housing; HUD should make clear that the primary mission of public housing is property/asset management; and, finally, HUD should give greater

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

focus to the performance of the assets and not to the PHA as an organization in its monitoring systems of public housing.

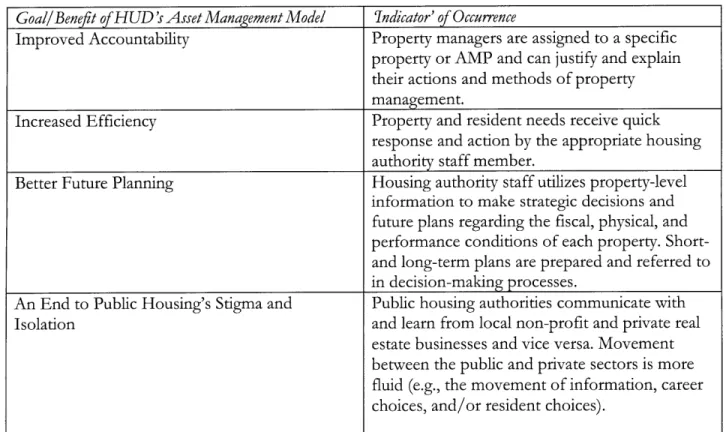

In light of GSD's cost model and recommendations, HUD issued the new Operating Fund rule (HUD, 2005) that required PHAs with 250' or more housing units to convert their operating systems to a new asset management model. Similar to the mechanisms of private real estate asset management models, HUD's model is characterized by five major reforms: property-based funding, budgeting, accounting, management, and performance assessment. The new Operating Fund rule replaces the previous system by which PHAs managed, operated and reported on an aggregate, portfolio-wide level. The goal of the new rule is to increase accountability and give greater attention to the financial, physical, and management performance of each public housing property.

9 The unit threshold for required conversion to asset management has been increased to PHAs with 500 or more federal public housing units since the new Operating Fund rule was first enacted.

-

Asset management is a well-known and widely utilized property management tool. Although asset management for public housing has only recently been introduced, conversations concerning how to introduce asset management in the public sector are not limited to the United States. Considerations

of asset management for social housing in Europe and Australia add substantial academic and professional insights while an evaluation of HUD's model provides a domestic example of how asset management can be applied to a public housing program.

4.1 ASSET MANAGEMENT IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR

Asset management is traditionally a private real estate business practice by which an agent of the property owner supervises the operation and monitors the performance of each property in a portfolio and creates and implements plans for the maintenance of each property. Asset

management is valuable because it provides owners with the relevant information necessary to make cost effective decisions on a property-specific basis.

The private sector utilizes asset management to place emphasis on optimizing financial performance. The property-specific information gathered from asset management is utilized to identify properties that are not cost efficient while also realizing cost-saving strategies. Properties that are not financially viable are often cut loose from a private sector portfolio and investment decisions are made in a

strategic manner with the property-specific information gathered from asset management.

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

4.2 ASSET MANAGEMENT IN THE SOCIAL RENTED SECTORS OF EUROPE AND AUSTRALIA

Similar to the United States, asset management is a fairly new concept for social housing in Europe and Australia. There is no single steadfast definition of social housing, as it varies depending on country. Yet a number of similarities exist that allow us to learn from social housing as a

comprehensive housing program: the objective of social housing is to provide housing for citizens with low-income who are unable to secure housing in the private market; owners are usually local government authorities or non-profit organizations; and, government often provides some form of

subsidy. The characteristics of social housing in Europe and Australia are similar to those of public housing in the United States allowing legitimate comparisons between the housing programs' experience with asset management.

In contrast to private sector asset management, the social rented sector employs asset management to help social landlords make management decisions in order to reach their housing objectives efficiently. In the context of social housing, asset management is defined as "the range of activities undertaken to ensure that the housing stock meets needs and standards now and in the future in the most efficient way" (Larkin, 2000: 8).

Gruis and Nieboer (2004) present an enhanced model of asset management referred to as "strategic asset management." Strategic asset management merges asset management, as defined above, with strategic business planning. Strategic business planning is "the process of developing and

maintaining a viable fit between the organisation's objectives and its recourses" (Gruis & Nieboer, 2004: 6). Thus, strategic asset management combines the best practices of asset management and

strategic planning to create a comprehensive and deliberate management approach.

-

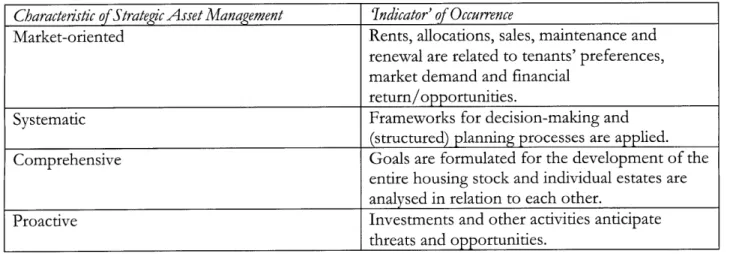

Strategic asset management is formed by four principal planning and management characteristics that can be summarized as (1) market oriented; (2) systematic; (3) comprehensive; and (4) proactive.

1. Market-oriented. Strategic asset management emphasizes that the social rented sector should not operate in isolation from the larger real estate market. Although social housing has traditionally been provided and managed via bureaucratic mechanisms and not by market forces, social housing managers and directors can still be mindful of the larger real estate market in management and decision making processes. A market-oriented approach encourages the analysis of a company's own strengths and weaknesses in relation to opportunities and constraints in the market in order to formulate strategies. In the social rented sector, a landlord will place an emphasis upon understanding market demand and opportunities to make decisions about current rentability, future market expectations, financial return, and opportunities for sale.

2. Systematic. A systematic and rational approach to planning and decision-making is a central feature of strategic planning. In a social housing context, transparent and logic planning and decision-making processes characterize a systematic management approach.

3. Comprehensive. Strategic asset management supports a comprehensive approach to planning and management. Rather than take a piecemeal and fractured approach, a clear mission and set of goals should be established to guide the authority in its day-to-day actions. While asset management is primarily concerned with an authority's portfolio on a property-specific level, the comprehensive approach will help inform planning and decision-making that is most

-Creating an Asset Management Model for Massachusetts State-Aided Public Housing

effective in achieving the authority's stated objectives. Furthermore, while emphasizing a property-specific level of attention, strategic asset management asserts that it is also important to be mindful of a portfolio's performance as a comprehensive whole.

4. Proactive. A passive and reactive approach to managing social housing results in poor

performing properties. Strategic asset management emphasizes that a social housing landlord anticipates a challenge and readies a response in advance, based on the observation of innovative and novel alternatives. This approach requires attentiveness and the ability to identify problems before they materialize and the action is a reaction rather than prevention.

Table 2 below summarizes the four principle characteristics of strategic asset management and the 'indicators' of each.

Table 2: Characteristics and 'Indicators' of Strategic Asset Management Characteristic of Strategic Asset Management Indicator' of Occurrence

Market-oriented Rents, allocations, sales, maintenance and

renewal are related to tenants' preferences, market demand and financial

return/opportunities.

Systematic Frameworks for decision-making and

(structured) planning processes are applied.

Comprehensive Goals are formulated for the development of the

entire housing stock and individual estates are analysed in relation to each other.

Proactive Investments and other activities anticipate

threats and opportunities. Source: Gruis & Nieboer. (2004).

Strategic asset management is a comprehensive and calculated approach to property management in the social rented sector. The four characteristics of strategic asset management are useful in that they provide a qualitative framework based upon goals rather than prescriptive methods.

-