Demystifying the leaking workforce pipeline: barriers facing female

professionals in the Middle East and East Asia

By Aisha Alomair

B.Sc., Joint Honors, Mathematics & Computer Science

The University of Birmingham, 2011

Submitted to the MIT System Design and Management Program

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Engineering and Management

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

June 2017

U MES NSTITUTE

OFT

-,HN

LOGY

JUN 2

7

2017

LIBRARIES

2017 Aisha Alomair. All rights reserved.

ARCHIVES

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly

paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium

now known or hereafter created.

I

Signature of Author:

Signature redacted

Certified by:

Accepted by:

Aisha Alq!mair

System Design and Management Program

27 May 2017

Signature redacted

Richard C. Larson

Mitsui Professor, Institute for Data, Systems, and Society

Thesis Advisor

Signature redacted___

f

Joan Rubin

Demystifying the leaking workforce pipeline: barriers facing female

professionals in the Middle East and East Asia

by

Aisha A. Alomair

Submitted to the Department of System Design and Management on June, 2017 in Partial

Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and

Management

Abstract

The high levels of female unemployment in majority Muslim countries constitutes significant lost opportunity on overall economic development. Nations that employ more women enjoy higher GDP's and a diverse talent pool. There has been little research done on the quality of women's career paths in these countries. Some nations struggle to push women into the workforce due to cultural and traditional expectations. In this thesis, we present a survey-based approach to

understanding three barriers that could hinder women's entry to and development in the workforce. The barriers discussed are barriers to initial entry, barriers to retention and barriers to promotion. Cross examination of survey results from respondents in Middle Eastern countries and Southeast Asia have verified the high tertiary educational attainment of women. The results have verified the struggles of working women obtaining promotions. Working mothers in particular find difficulties balancing work and household responsibilities, which could affect their retention in the workforce pipeline. We end the survey analysis by providing recommendations to better strengthen women's retention and overall job satisfaction. This includes spreading awareness, adding guidelines to auditing institutions, and establishing new policies to make the workforce a more attractive platform for women, such as by subsidizing childcare and transportation. We contend that although these countries have put great efforts in attracting women to the workforce, more systemic female welfare policies will be needed in order to better capitalize on the valuable human capital asset that women add to the talent pool.

Thesis Supervisor: Richard Charles Larson

Table of Contents

LIST OF FIGURES ... 6

Chapter 1 Introduction

...

7

Introduction ... 7

Sustainable Nation Building ... 7

The problem with quotas ... 13

How can we structure women's careers? ... 14

Chapter 2. Country-by Country review

...

17

Strong Tertiary Enrollment ... 17

Gulf States ... 18

Arab States ... 25

East Asian Countries ... 27

Cultural Overview ... 31

Chapter 3 M ethodology

... 36

Introduction ... 36

Survey Administration and Sample ... 36

Questionnaire ... 38

Tablel. Demographics of Respondents by Country ... 38

Data Analysis ... 42

Synthesis ... 42

Chapter 4: Survey Results & Discussion ... 46

Overview ... 46

Barriers to initial Entry ... 46

Gulf States ... 47

Unemployment in the Gulf States ... 52

Arab States ... 56

East Asian Countries ... S9 Summary ... 61

Barriers to Retention ... 63

Childcare ... 64

Arab states ... 66

Job satisfaction ... 68

Evidence from Currently Unemployed W omen in the Gulf States ... 69

Family Support ... 73

Barriers to Promotion ... 74

Equal pay for equal work ... 74

Promotions ... 76

Enhancing Female W elfare ... 92

Results from Top Earners ... 96

Conclusion ... 97

CHAPTER 5 RECOM M ENDATIONS ... 98

Subsidized Childcare ... 98

Independent Auditing Authority ... 103

Limitations & Future Research...104

CHAPTER 6 REFERENCES ... 105

CHAPTER ppe ... 109

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE 1-EMPLOYMENT CURVES FOR WOMEN AND MEN IN SOUTH KOREA (SOURCE:BLOOMBER, 2015) ... 11

FIGURE 2-PERCENTAGE OF SEATS HELD BY WOMEN IN 2015: DATA COURTESY OF THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION ... 13

FIGURE 3-TRADITIONAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING V-MODEL... 14

FIGURE 4-LABOR MARKET COMPOSITION IN GULF COUNTRIES...19

FIGURE 5-SYSTEMS DYNAMICS FEEDBACK LOOP ON OIL PRICES EFFECT ON GULF ECONOMIES...20

FIGURE 6- DIFFERENCES IN STEM SCORES BY GENDER ACROSS COUNTRIES ... 28

FIGURE 7-ENROLLMENT IN STEM DISCIPLINES BY GENDER ... 29

FIGURE 8-GENDER INEQUALITY INDEX IN ASEAN COUNTRIES... 30

FIGURE 9-SYSTEM DYNAMICS STOCK AND FLOW DIAGRAM ON GENDER ROLE IDEOLOGY ... 31

FIGURE 10- PERCENTAGES OF UNEMPLOYED WOMEN BASED ON LENGTH OF UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE GULF STATES ... 53

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I am also grateful to my thesis advisor, Professor Larson for his unlimited support. His wisdom, guidance and prompt assistance throughout the development of the thesis was instrumental, especially in aid regarding analytical thinking, raising appropriate and meaningful questions, and exemplifying what it really means to be a systems' thinker. Being a graduate student of yours was a tremendous honor.

My deep thanks and acknowledgements to the valuable help of Lisa D'ambrosio. Her

professionalism and patience throughout the structuring of the survey, and the editing and drafting phases of the thesis were immensely beneficial to the development of this paper. This would not have been possible without your help.

My gratitude is also extended to my brother, Abdulrahman Al-Omair: Your prompt suggestions and insightful edits helped in perfecting and sculpting the thesis as it is today. Thank you for

enlightening me with historical perspectives that helped shape the narrative of the thesis.

To my husband, Abdullah Al-Arfaj: Thank you so much for supporting my dreams from thousands of miles away. Your patience with leaving the kids with me throughout my two years of study have made us a more resilient and stronger family.

Special thanks to MIT's Work-Life Center for providing backup child care when I had difficulties with meeting assignments. I also thank MIT's mental health for their unrestricted attention and listening to me about my fears, hopes, and dreams. MIT opened its ears, heart and eyes for its students, and it is a mark of pride for MIT to address issues of mental health with finesse. Being a single parent of two in a foreign country will have its toll on a brain's stability.

Special thanks to the SDM faculty especially Patrick Hale, for believing in me as a candidate for this program. A special thank you to Maria Brennan for always being there for struggling international students.

To my family, colleagues and friends whom assisted me with this research and continued to offer their support and wishes, Thank you.

My sincere gratitude goes towards the Saudi Arabian government for its generosity in granting its citizens scholarships abroad. It is with the government's assistance that Saudi women have been able to obtain distinguished degrees in the most prestigious institutions around the world. Thank you my dear country, I hope to contribute to your development and show my appreciation.

Special Dedication

This paper is dedicated to a special woman. A woman crippled by rheumatoid arthritis since the age of 25, she lived most of her life in a chair. This handicapped woman is my inspiration. At the age of

9 in a settlement named Hofuf, modern-day Al-Hasa of Saudi Arabia, she walks out of her home,

holding her father's hand and goes to school. Being one of few girls going to school at the early 50s, she would hide behind her father's back, away from criticism and disapproving looks. On their way to school, the girl is confronted with her maternal grandfather, angrily asking, "Where is she going?". "She is going to school", her father replies. The little girl smiles to her grandfather, but is devastated. His raises his chin, and spat in her face. "If I see you going to school again, I'll cut your legs off," said the grandfather. The little girl wipes her face and follows her father back home. The next morning, her father wakes her up, telling her, "It's time to go to school." When she voices

trepidation, he adds, "Listen to me, if he cuts your legs off, you will go to school on his shoulders." And go to school she did. She finished elementary school, got married, bore children, continued on to middle school, high school, and finally graduated from college and became one of the first female graduates at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. She never stopped learning.

To this day, a body torn by deteriorating bones, dry eyes, short breath, she opens her books, slowly puts on her reading glasses, and takes notes of the book in her hands. At the age of 75, she opens a computer and Googles, researches, and formulates opinions on many diverse topics. Many in her granddaughter's age could not converse with her at equal standing, while most women in her age are not aware of said topics entirely! Up to date with technology, she is a social media fanatic, and to this very day texts, and prays for me, and asks me to "Keep going to school."

That woman is my grandmother: AlSayiddah Fatimah Al-Hashem

Although fighting a monstrous disease that has crippled her body and taken away her dreams, she can still see them. She dreams through me, and through the eyes of my children. Her father, Al-sayyed Alnahwi, my great grandfather, was the one who instilled in her the love of learning. He was the director of the Al-Hasa branch of the Committee of the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. He was a great, kind and thoughtful man. Because of his nobility, my entire maternal line continued their higher education journeys and became valuable contributors to society.

To my daughter Reem: You come from a line of strong women. Your great grandmother fights to this very day a 68-year old disease that is a terribly complex medical case, and your grandmother is a resilient breast cancer survivor. You have crossed half the world with your brother to accompany me on a two-year journey, away from your father, family and country. Carry this legacy with you, and leave your mark in the world.

To my son Saif:

Just

like building a Lego set out from a box, be the architect the world hopes you to be. Build a strong future for your generation, one filled with diversity, tolerance, acceptance,innovation, entrepreneurial thinking and of course, humility.

To my only sister Fatimah: Thank you for being there with me every step of the way. With every difficult night that passes, you were there to pick up a long-distance call. A sister is truly your other mother. I could not have made it without you.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction

Corporations worldwide aim to increase profits and please their shareholders by keeping costs to a minimum, and, to reach that goal, they have designed the workday to be demanding and physically taxing. Although this corporate architecture may have been profitable and successful during the Industrial Era, it may not be as sustainable in the generations to come. Unfortunately, requiring such a demanding workday puts half of the population at risk of having to choose between their careers and their personal lives.

Roughly half of every country's registered births are female, so it is no surprise that including this half of the population in the workforce would lead to significant financial returns. With over three billion women entering the global economy in the next decade, tapping into this significant

population and achieving its full potential could have beneficial effects on the global financial status. Countries that have taken proactive measures to ensure strong developmental pipelines for their female citizens, from K-12 education to initial employment and throughout their careers, will enjoy a more educated, healthier, and independent younger generation

Sustainable Nation Building

Countries that foster strong representation of both genders in their workforce will find a flourishing economic growth trajectory. High female unemployment has therefore been labeled as a threat to countries where imbalance is the norm, as is the case in many Middle Eastern and East Asian countries, (Al Kharouf & Weir, 2008). The Global Gender Gap report, an annual report published

by the World Economic Forum ranks countries based on gender equality measures. These measures

include economic participation, educational attainment, political empowerment and life expectancy. The Gender Inequality Index (GII) measures gender disparity based on three categories namely labor market participation, empowerment and reproductive health. (UNDP, 2010).

Most Middle Eastern and Asian countries fall on the lower end of the Global Gender Gap whereas the Nordic countries consistently rank at the top as in Table

1

below.Country of Interest Global Gender Gap Index Rank

Iceland 1 Finland 2 Norway 3 Sweden 4 Denmark 19 Indonesia 88 Malaysia 106 Japan 111 South Korea 116 Qatar 119 UnitedArab Emirates 124 Kuwait 128 Bahrain 131 Oman 133 Jordan 134 SaudiArabia 141

Table 1.1- Global Gender Gap rankings- Source: Calculated from the World Economic Forum Report, 2016

Since labor market participation in most Middle Eastern and Asian countries is imbalanced,

enhancements to economic participation will benefit these countries significantly. The countries can expect substantial increases in GDP since many studies have directly linked higher female labor participation rates to increases in GDP. A study conducted by Strategy & concluded that raising

female employment to the level of male employment could increase GDP by 5% in the United

States, 9% in Japan, 12% in the UAE, and 34% in Egypt (Strategy &). Based on various studies conducted in the EU, (Lofstrom (2009)) concluded that if the female-to-male ratio were equally balanced in Europe, the EU's GDP would increase by 30%.

In order to achieve this balance, nations must create conditions that enable women to reach their maximum potential so that they can contribute socio-economically (Metle, 2002; Mostafa, 2003).

When development policies are gender neutral, they are more sustainable, and, in turn, they lead more women to participate in nation building because they allow the utilization of all national talent,

regardless of gender, as a tool for growth (Atal et al., 2012).

Although such policies might have an effect to some degree, however, women themselves also need to be aware of their capabilities, strength, and value to nation building. Khader (2011) states that women must be aware of their roles and how their presence influences society. He adds that women currently have limited views of their capabilities. Therefore, skills, capabilities, and talent can

combine into one effort that contributes to the country as a whole.

Countries with low female employment, therefore, need to strongly acknowledge the issue, and they must work towards finding long-term policies and solutions that ensure pipelines for female

development from K-12 education to the first day of employment. Countries that invest national funds in the education of women but fail to ensure their successful placement in the workforce have not gained much return on their investments.

This issue is not easy to address. Unemployment in any country is considered to be a complex socio-technical issue that requires careful analysis and proper understanding of workforce dynamics, and female unemployment is even more complex socially and culturally. Corporations are constantly assessing their gender diversity levels and working to improve imbalances in their workforce pipelines. In other parts of the world, governments face different cultural challenges in trying to increase women's attraction to work. Two prime examples of Asian countries that have faced

cultural challenges in increasing women's participation in the workforce are Japan and South Korea; both happen to be Far East countries also on the lower end of the Global Gender Gap. From the literature, both countries seem to struggle retaining women in the workforce. Women in Japan and South Korea are expected to care for the household after marriage.

Economical trends show that 70% of Japanese women drop out of the workforce after having their first child (The economist, 2014). South Korea is no different, with similar cultural patterns. We describe the challenges these countries have faced in detail in the next few paragraphs.

Japan primarily struggles with retaining women in the workforce. A study conducted by Kyodo News that surveyed 28 of the major Japanese companies showed that of 1,000 women that were employed, 8 0% have left or are no longer working in the position they once held. The pipeline

continues to suffer in the developmental stage, as a mere 9% of managers in Japanese companies are women even though the total participation rate of women in the workforce is over 40%.

In 2003, the Japanese administration set quotas for corporations to target having 30% of board executive positions held by women. Corporations were unable to fulfill that target, and the government needed to reduce that quota by half, to 15%. A policy was added in December 2016 requiring corporations to publicly disclose ratios of women to men and to increase women in management. This policy states that any corporation that employs more than 300 employees will be required to develop plans for increasing the percentage of women in management and to set targets that are verified and validated by the government.

Overall, the Japanese government has worked very diligently for 30 years to close the gender gap, but to date, the targets have not been met. This fact raises the question of how strong an effect the roles of tradition and culture have on women themselves and their ability to compete alongside their male counterparts, develop, and flourish in the workplace. The Japanese government made a

substantial policy change by enacting the Equal Employment Opportunity Law in 1985, and, as a result of this direct policy input, female workforce participation in Japan has grown by 8.8 million (Japan Times, 2016).

South Korea has had similar cultural challenges to Japan. The working day has been structured based on the Industrial Age, with extended hours of work every week. According to the World Economic Forum, South Korea placed second to Mexico globally in the number of hours worked every week. Having such a long work day embedded in the overall Korean culture may make it very difficult for women to balance a career with their personal lives.

The South Korean government, fully aware of the benefits of retaining Korean women in the workforce, has dedicated a ministry tasked with addressing gender equality. The Korean government has made strong steps to increase women's participation in the workforce that require the drastic restructuring of the workplace, so cultural resistance will be inevitable.

A well-known term in Korean culture is the "M" shaped curve, which models the career paths of

women. Women initially enter the workforce at faster speeds than men early in their careers because men in the same age range serve in the military. However, around the mid-career point, when women are more susceptible to childbirth, their workforce participation tends to drop, although it increases slightly later in their careers.

Men, on the other hand, after serving their first two years in the military, begin their careers and sustain them throughout their lifetime until retirement. Figure 1 illustrates the differences in labor participation rates over time for women and men. The Korean government has noticed this trend, as it is working diligently to increase access to on-site childcare at Korean corporations and to ensure that mid-career women return to their jobs after having children and continue building their capabilities in the hopes that, at the end of the pipeline, these women may have obtained the required qualifications and appropriate experience to sit on boards as executives.

Women Fall Behind

Labor participation rates in South Korea in 2014 E Male NFemale 100% 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20:24 25-29 30.34 35'39 40144 45-49 50-54 55-59 60 and up

Figure 1-Employment curves for women and men in South Korea (Source:Bloomber, 2015)

Culture plays a strong role in adopting changes to the workforce structure. Some cultures initially resist, continue resisting, and eventually adopt the trend a few decades later.

Others witness firsthand the swift implementation of these policies and impose penalties on organizations that do not comply with governmental initiatives. In particular, the Nordic countries have enjoyed financial gain and have become a prime model for developing nations by adopting

changes to the workforce structure. It is no surprise why they consistently rank the highest on the Global Gender Gap index. Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, and Finland have implanted strong measures to break the glass ceiling. The most rapid policy change has been achieved by imposing quotas; Figure 2 shows that the Nordic countries are among the countries in Europe with the highest percentage of seats on corporate boards held by women.

To describe a specific example, Norway took the lead in the effort to impose quotas in 2003 by requiring corporations to reserve 40% of their board seats for women. There was strong resistance initially, and corporations struggled to find these women, recruit them, and feel comfortable with their presence in the boardroom. In response to this resistance from corporations, the government enforced the quota by reserving the right to delist companies that failed to meet it. Elin Hurvenes, a

senior Nordic professional executive, stated that men are more likely to hire friends and inner circle members, like shareholders, who support their interests. She adds that as long as men hold executive positions, it is most likely that more men will be hired for board positions. Without direct influence

from the government, the push to place more women in executive positions will likely be a struggle (Hurvenes, 2017).

This example speaks volumes about how much work corporations and governments alike must do on a professional level to educate women and help them improve their qualifications.

Women on European corporate boards

Percentage of seats held by women in 2015

Iceland 44 Norway 39 France 36 Sweden 33 Latvia M30 Italy 29 Finland 1129 United Kingdom 28 Belgium 26 Denmark 26 Germany 26 Netherlands 25 Croatia 22

Figure 2-Percentage of seats held by women in 2015: Data courtesy of the European Commission

The problem with quotas

Many critics of quotas have labeled them as a "quick fix" for gender parity numbers and have argued that corporations might have to place women that may not necessarily be fit for a board seat in order to meet the quota. A separate study from the University of Michigan (Ahern & Ditmar, 2012) finds that corporations initially lost revenue due to hiring female board members because they lacked the proper experience. These statements clearly point to a need to develop a holistic pipeline

for women starting from their initial entry in the labor market and to further develop their careers dynamically over time so that when corporations do need women, they are confident in their capabilities and can guarantee their qualifications. Quotas themselves are not the problem; the problem instead merely lies in the way in which they were implemented. The instant implementation of quotas might enforce peaks and valleys across the managerial hierarchy, so that there are many women in entry positions, very few at the mid-career level and in senior management, and too many in the boardroom. A balance of women across the levels of management hierarchy can maintain a

How can we structure women's careers?

The creation of human capital is complex, there must be a methodology by which the system is designed, analyzed, fitted to meet requirements, tested to specifications, and validated until its dynamic complexity emerges and feedback is generated over time. This feedback is of utmost importance in allowing an engineer to reevaluate the system and its dynamic complexity and adjust

as necessary. This process is called a V-model in the field of systems engineering.

As system thinkers, we can confidently say that any system, whether it is a physical system (i.e. a hydro-electric dam), a medical system, a financial system, an educational system, or even a female workforce pipeline will eventually suffer if proper monitoring, assessment, and validation are not provided. The question that follows is how the V-model can be applied to women's career paths. The diagram and cycle in Figure 3 illustrate the traditional systems engineering V-model, and Table 1 provides an outline for applying the V-model to women's career paths.

Concept of

Operations

Project

Requi

Definition

a

Archi

rements

nd

tecture

Detailed

Design

Verification

and

Validation

Operat

and

Mainten

System

Verification

and Validatioi

Integration,

Test, and

Verification

Ion

ance

Project

Test and

Integration

Irn

pm

6nEntat V

Time

Level Traditional Systems Engineering V-Model Applied to Women's Career Paths

How can we structure women's career paths in a Concept of Operations How will this system be developed, way that ensures their sustainable growth and

operated, and maintained? extend this model across the pipeline to generations of women across all disciplines?

A solution must acknowledge all stakeholders: a

What are the needs of the end user? mother's family, her health and mental

well-Requirements Users are interviewed in order to being, her financial life, her colleagues (both form an understanding of what this men and women), how they interact with each

system is expected to perform. other, and how feedback is provided and value iP added to the organization.

.What is the framework for this How will a woman's career path look? How do

Detailed Design we structure women's career paths in a way that

system? balances motherhood, marriage, and business?

The system must undergo the

Integration, Test, and appropriate testing and analysis to Who can audit targets, development timelines,

Verification ensure holistic evaluation (i.e., hazard and performance? analysis, risk analysis, etc.).

How can we properly verify that the

System Verification and system is able to achieve the HR verifies that women have the qualifications

Validation requirements, and how can we and training required for placement in

decision-comprehend feedback from the making positions.

system?

Independent third-party authorities audit the

OpertionandHow can we properly enhance the

Operationsystem to better serve the implementation of policies on women's careers

Maintenance requirements outlined? and suggest improvements to women's work-lift

balance. Table 1.2 Traditional systems engineering V-model applied to women's career paths

Without a doubt, acknowledging women's roles in the workplace and working to significantly increase their numbers across the pipeline is a complex system, with many stakeholders involved. A detailed study into historical patterns is necessary to understand the dynamics of women in the workforce. In order to understand how women's career pathways can be better structured, an in-depth review of all of the progress that has been made in the literature is necessary.

This review allows us to understand the following trends, which we group into three barriers to women's progression into the workforce:

a) Barriers to initial employment: These barriers arise when men and women receive similar

educations but women struggle immediately after graduation from tertiary education to enter the workforce at the rate at which they progressed throughout their education.

b) Barriers to retention: These barriers arise when employment curves show a strong trajectory

for both genders at the entry level but, around the mid-career level, when women usually begin to plan a family, a significant portion of women leave the labor market, creating a drop in the employment curve for women.

c) Barriers to promotion in employment: These barriers arise when both genders enter the workforce in large numbers but, over time, men progress at a faster rate, earning promotions,

raises, and better careers, whereas the female workforce lags behind in terms of promotions and overall career development.

Chapter 2. Country-by Country review

In this thesis, we benchmark six countries that have actively pursued increasing women's participation in the labor market, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Jordan, Kuwait, Malaysia, and Indonesia, to better understand the factors that can impact women's workforce participation. While we would like to review Japan, Korea and the Nordic countries in more detail, we primarily will focus on the Muslim countries since they share similar religious preferences and cultural patterns. These countries' markets are developing rapidly and are important to the development of the global economy. As mentioned previously, these countries rank consistently behind on the The Global Gender Gap Index (WEF, 2017). We group these countries under three umbrellas according to demographics, geography, and economic status. The first umbrella groups women from the Gulf states. The second umbrella groups women from Jordan and the final umbrella groups women from Indonesia and Malaysia. We will continue to refer to these groups across this thesis to ease reference during comparisons. In this review, we aim to understand the reasons that women's rapid penetration into the workforce has been delayed in these countries.

Researchers agree that a literature review on women in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) workforce is needed (Omair, 2008). However, before we discuss each of these six countries in detail, we highlight a very important pattern in these countries, the strong educational backgrounds of women.

Strong Tertiary Enrollment

An important observation from the overall literature is that women in the Middle East and East Asia frequently receive academic degrees, advancing in their studies with strong performances, but

immediately after graduation, that strong trajectory ceases to accelerate and eventually experiences a steep decline. According to (Al Zuabi, 2016), "In Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Algeria, Oman, Jordan, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia, tertiary education enrollment rates are higher for women than men." Women with tertiary degrees also achieve higher grades than their male counterparts (Bernard, 2006; Gonzalez et al., 2008; Karoly, 2010). Despite this high rate of success in education, the same cannot

These countries have made generous investments in educating their populations, but the high unemployment rates for women do not mirror this high investment and therefore represent a loss on that investment. Across the GCC, women constituted a higher percentage of nationals entering college. In the UAE, 50% of nationals that were granted scholarships overseas were women (Nelson, 2004). Women also comprise a higher percentage of those enrolled in all vocational subjects, such as information technology, except for engineering. In Saudi Arabia, the enrollment rates for women are highest in medicine and management studies. In Bahrain, 19 out of the 20 schools that achieved the highest grades were girls-only schools. Across the GCC, girls

outperformed boys in STEM subjects. In the UAE's 14 Higher Colleges of Technology, 65% of nationals awarded "distinction with honors" in 2006-2007 were women.

With this strong background of educational attainment, it is unclear why a large percentage of women are unable to become employed, and, if they are employed, are unable to become employed in jobs that mirror their educational majors. Rutledge (2009) argues that male nationals support their female counterparts in education much more strongly than they do in employment, especially when such employment is in the private sector. According to the World Economic Forum, the GCC countries are highly ranked and surpass even the United States and Switzerland in terms of

educational attainment, but in terms of economic participation, the GCC countries are consistently behind. The UAE and Saudi Arabia are the GCC's largest two economies, yet they fall on the far ends of the Global Gender Gap Index with Saudi Arabia ranking 134/144 and the U.A.E ranking 124/144.

This discussion brings us to our first research question. Why do the countries considered in this study continue to face low female employment rates even though significant numbers of their female citizens hold high-quality tertiary degrees?

Gulf States

Due to demographic and economic similarities, the Arabian Gulf countries have been grouped together for ease of comparison. Since the discovery of oil in the early 1930's, the Gulf States have developed rapidly. With this financial development, education flourished, populations surged, and prosperity stabilized the labor market in the public sector and foreign businesses alike.

Due to the affluence of the Gulf States in the initial years of oil exportation, their labor markets were designed to pass this affluence on to citizens by granting them high-compensation jobs in the public sector, with strong labor laws that guaranteed their long-term retention and benefits. This generosity allowed citizens to avoid the brutal demanding jobs that the private sector is usually known for (World Bank, 2004b; Davidson, 2008a). Although this system initially served as a wealth platform for citizens of Gulf countries, it is currently experiencing turbulence due to declining oil prices. The original employment system caused nationals to prefer public sector jobs, leading to nationals making up over 70% of the public sector workforce and allowing the private sector to be dominated by expatriates (Rutledge, 2009). Table 2 shows the percentage of nationals in each sector in each of the Gulf countries. Figure 5 illustrates the complex system dynamics involved in GCC markets. Bahrain

Kuwait

Oman

Qatar

Saudi Arabia

United Arab Emirates

GCC

National workforce

(as % of total workforce)

Total

Public sector

Private sector

36.1

90.8

28.6

16.9

74.6

2.7

28.7

80.5

15.5

44.8

52.8

17.0

50.5

91.3

45.3

10.4

27.4

1.3

38.3

72.3

31.7

National unemployment

(as % of total national

workforce)

Total

Males

Females

18.4

12.4

32.8

3.7

6.3

...

3.1

1.7

6.0

9.8

6.9

24.9

13.8

2.0

12.0

9.2

7.0

21.2

Figure 4-Labor market composition in Gulf countries

As mentioned, the GCC countries mainly depend on expatriates to staff the private sector. Furthermore, nationals who own private sector corporations hire expatriates from South Asian countries cheaply to earn profits rapidly. The downside of this approach emerges because, when the public sector shrinks and the public sector is pressured to cut costs and raise attrition rates, nationals find themselves pushed into a private sector that they were not trained for. Dependence on

According to the (World Bank, 2015) $100 Billion leaves the GCC annually in the form of remittances, and that money is never recycled back into their economic circles. Furthermore, the

Gulf States' private sectors are limited for the most part to basic services such as retail, food and beverages, and leisure.

There is yet no pressure for innovation and competition in advanced economical avenues or services such as manufacturing, IT, engineering, and consulting, which makes relying on trained expatriates a non-option for companies that work in light industries or manufacturing.

The GCC countries, fully aware of the detrimental effects of overdependence on expatriates and an oil-based economy, began swift nationalization efforts in the hopes of placing more nationals in the private sector. However, nationals dislike the private sector because it provides poor compensation package options, is not considered a real career, and is considered culturally inappropriate (Harry,

2007). At the same time, private firms find nationals to be costly to please and to maintain (Al-Ali, 2008). Moreover, private corporations consider nationals to be vocationally unprepared for the roles

of the private sector, as the expatriates were.

# of employees 0 &employee0

Payroll 0

cost

AX 0

Atrition rare B

Attrition 0 operating expenses0

Pressure to cut cost

0 profit "W-, 0, 0 efi

+-oil production oil price S/barrel

Figure 5-Systems dynamics feedback loop on oil prices effect on Gulf economies

Compounding this severe imbalance between the private and public sector, male nationals

discouraged women from seeking employment in the private sector. Although this may have seemed

like a reasonable preference when oil prices were high, it is no longer sustainable for one family

member to maintain the lifestyle that the culture has become accustomed to.

The plunge in oil prices has caused the prices of goods and services, the cost of private education, and domestic helper's salaries to rise. If oil-dependent businesses suffer, the employees suffer, budgets are cut, salaries are lowered, and household income shrinks.

The country cannot easily survive a recession with half of its talent unemployed. One way to raise

GDP in this difficult situation is by incorporating unemployed women in the labor force.

The GCC has made strong efforts to employ women in greater numbers, beginning with generous educational scholarships granted unconditionally to its citizens. In the following sections, we compare these efforts in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is a nation with bountiful resources, which include not just oil and natural gas but also the potential of its human capital. Saudi Arabia has a population of over 31 million as of 2016, with

70% of its workforce in the public sector and the remaining 30% in the private sector. Of those private sector workers, only 16% are Saudi nationals, whereas the rest are expatriates. As the country introduces its ambitious Vision for 2030 to transition from an oil-based economy to a knowledge-based economy, one of the big questions is how to push more Saudi nationals into the private sector, which can be a breeding ground for startups, incubators, high-tech firms, and industrial services.

A detailed review of the Saudi workforce reveals that only 22% of women are working. Saudi

Arabia's GDP could increase significantly in the next 14 years if more women are encouraged to join the workforce. With over 60% of the Saudi population under 21 years old, the upcoming generation

is tech-savvy, ambitious, and anticipating a bright future. Saudi women constitute 48% of the

population, 51% of university graduates, making them the prime target for job creation and potential contributors to increases in GDP.

Another challenge in Saudi Arabia is the high proportion of expatriates in the private sector. Saudi Arabia has been generous in terms of education, providing unlimited scholarship opportunities both locally and abroad.

Table 3 shows that Saudi Arabia has a large and growing educational budget. As a result, Saudi Arabia graduates 250,000 Bachelor's degree holders annually, but it struggles to employ more than 40% of them.

Table 2.1-Annual education expenditure in Saudi Arabia, Source: (Alshahrani,2014)

Saudi Arabia is the second highest in remittance sending globally and in 2015, the World bank estimated that expatriates remitted $37 billion outside Saudi Arabia. (Hamiz, 2017) This figure is over a third of what the GCC countries collectively lose annually in remittances due to expatriates. We see similar patterns in the UAE and Saudi Arabia in terms of expatriates gaining significant shares of the private sector and low female employment rates.

The United Arab Emirates

As mentioned above, the UAE is similar to its neighboring Arab states in terms of human capital.

75% of UAE university students are women, but after graduation only 15% of these women are

employed full time. (Marmenout & Lirio, 2014). Referring back to the three employment barriers outlined in the introduction, the female workforce in the UAE suffers the most from the retention barrier.

The UAE also faces the challenge of a high proportion of expatriates in the private sector. An oil-rich country, the UAE first discovered oil in early 1971 and has enjoyed tremendous growth

economically for a generation. Due to its flourishing economy, expatriate workers flocked to the

UAE to build businesses, creating a diversified society with over 200 nationalities. As rapid as this

development was, it caused the nationals to be marginalized, and in 2012, nationals comprised about 0.4% of the private sector workforce.

Year Education Budget (Billion U.S.D)

2008 $28.12 2009 $32.62 2010 $36.63 2011 $45.18 2014 $56.56 Aj

Policy had a strong role in enforcing nationalization efforts, as, for example, in the banking sector, where banks are held to a quota system that is based on an incremental percentage of nationals annually. In 1999, this system was put into place since the banking sector was an important sector for employing Emiratis. In order to meet the target, banks needed to increase Emirati representation at a 4% annual increase. The prime target was for nationals to occupy 40% of the banking workforce but it currently hovers around the 35% mark. Multinational corporations are hesitant to hire

nationals due to their lack of vocational training and the difficulty of pleasing the nationals, and the nationals themselves also prefer the public sector.

As in Saudi Arabia, unemployment is a challenge for both genders, but it is especially acute in the female population due to the high tertiary rates of education that these women have achieved. Certain social complications add to the challenges facing Emirati women. Because expatriates constitute the majority of the population in the UAE, a high birth rate among nationals is

encouraged by the government and is further encouraged by nationals and their families. A study conducted by Omair (2010) concluded that women encounter gender-based barriers in their career development that vary depending on the social status of the family. Further focus groups formed by Marmenout and Liio (2014) on 18 Emirati women working across various organizations identified four key challenges for women pursuing careers in the UAE. They are societal norms that limit career pursuits, the reconciliation of family planning with career pursuits, the prioritization of family and home, and maintaining modesty relative to men in earnings and career progression. Hodgson et al. (2015) study social marketing and its effect on the female workforce and conclude that the UAE is distinct in its open economic model and attractive business platform, which has significantly helped encourage nationals to liberalize their social values and which, as a result, has had a direct effect on the lifestyles of women. The authors add that government intervention was a prime factor in female workforce enhancements in both Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Kuwait

Among all of the Arab countries, Kuwait has the highest female work participation rate of 45% (Coleman & Abdelgadir, 2014). We aim to understand in this literature review why Kuwait had success in pushing more women into the workforce and what the implications may be for nearby GCC and Arab states. Kuwait's high female employment rate can be attributed to many reasons. Chief among them is the establishment of a coeducational institution, Kuwait University, as early as 1965. According to Alzuabi (2016), Kuwaiti women are moving towards modernization much more quickly than women in the other Gulf countries. The pipeline of Kuwaiti women, however, although strong in terms of initial entry, is not as strong in terms of leadership positions.

He adds that the Kuwaiti talent pool will remain underutilized if Kuwaiti women cannot be raised to leadership levels. Similar to Jordanian law, Article 7 of Kuwait's constitution recognizes the principal of equality among its citizens regardless of race, origin, language, or religion.

As in many Gulf countries, oil played an important role in Kuwait's development. After the discovery of oil in Kuwait, the economy improved, and Kuwaiti women enrolled in school and worked side by side with men instantaneously.

According to the literature, in 2009, Kuwaiti women occupied 8.5 5% of leadership positions in the public sector and 6.5% of those in the private sector. To date, woman's employment has

skyrocketed to 54.3% in the public sector. The tertiary education pattern is no different in Kuwait, where 70% of college undergraduates are women.

The literature implies that the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait had a strong impact in energizing women to step forward in rebuilding the country. According to (Zuaibi,2016) women took part in resisting occupying forces, and in recognition for their efforts, a conference in Jeddah in October 1990 granted women the constitutional right to equality in decision-making processes and equal powers in the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government (Fayeq, 2001). Kuwaiti nationals felt an urgent need to rebuild and heal their country after the invasion, so they ensured that every citizen had an equal opportunity to contribute to this rebuilding and, thus, moved to enshrine this value in policy, where it was easy to propagate and make claims on behalf of women if needed.

Kuwait is also significantly smaller and more geographically uniform than most of the Arab states, and, therefore, the spread of education was much swifter than in its neighboring GCC states. Entrepreneurship is strong in Kuwait, with both genders contributing significantly to the private sector. Despite all of the previous milestones reached, however, Kuwaiti women are still lagging behind in terms of leadership positions.

Arab States

Jordan

In 2004, the national development of human rights noted that women's low workforce participation rates imposed a high cost on Jordanian economic development, especially in the private sector

(Khalaf et al., 2015). Jordanian research has highlighted the significant effect of the low participation rate of women in the workforce as a cost to Jordan's economy, especially when a significant portion

of women are well educated, leading to the underutilization of human resources (Peebles et al., 2007; Moghadam, 2013).

Women's workforce participation is lower in Jordan for several reasons. Compared to other Middle Eastern countries, Jordan has one of the highest costs of living (Al Qadi & Gharib, 2012). As a result, women with lower incomes may not see the value of working away from home, as the costs

of childcare are far greater than the potential net earnings from working. Traditional cultural restraints in Jordan also affect the retention of women in the pipeline, according to Sawalha (1999). Women in Jordan are most likely to leave their jobs after marriage, since marital relationships are a priority for men and women in Jordan.

Nevertheless, Jordanian law is very protective of women's labor participation and rights. According to the literature, Jordan has protected women through the regulation that "all Jordanians are equal by law and have the right to assume public office and the right to work." In 1996, a national

committee was developed to increase female support within governmental and non-governmental sectors, and the Jordanian Women's Union (JWU) was formed. Some policies that were initially intended to help women, however, ended up causing discrimination instead (Council, 2008).

For example, Jordanian law includes a detailed summary on childcare, pregnancy, and paid maternity leave. However, since these policies are enforced by law, corporations abuse them by choosing to hire men due to the higher costs of hiring women. Table 4 showcases the laws and regulations for women in the Jordanian workforce.

Category Jordanian Labor Laws

Pregnancy and maternity leaves

Childcare regulations

Law no (8) of the 1996 labor code forbids the firing of pregnant women after the sixth month of pregnancy and of working mothers during their maternity leaves.

Maternity leaves were increased from 60-90 days.

The 1996 labor code requires the private sector to grant maternity benefits to female employees. Article 70 states that ten weeks of maternity leave should be taken before or after delivery, and it is illegal for women to work during the first six

weeks after delivery.

The 1996 labor code provides female employees who have worked in establishments for ten weeks or more the right to one year's leave without pay for

childcare purposes.

Article 71 grants a working mother the right to a total of one hour per day to nurse her children for a period of one year after delivery

Article 72 requires employers with a minimum of twenty married women to provide a nursery and qualified childcare worker to care for children under four

years old if there are at least ten children

Table 2.2 Jordanian labor laws relevant to pregnancy and childcare

These Jordanian labor laws were passed in good faith to protect the interests of working women. Although these policies seem to provide strong protection, they can be used against women by providing reasons to avoid offering women positions in a corporation. Since a corporation needs to budget for daycare if it hires more than 20 women, it may work hard not to exceed that head count so that it does not incur more costs. By Jordanian law, women are granted a full year of voluntary maternal leave to look after her children.

Having such an extended option may target mothers as intermittently unavailable. This could lead employers to overlook mothers as project managers since placing household duties over the

corporate job may significantly delay the completion of projects, and, therefore, important work may be assigned to men instead.

We conclude that there is a need for more gender-neutral policies and a methodology to incentivize pay for childcare where the government pays subsidies to assist small- to medium-sized corporations with maternity benefits

Khalaf et al. (2015) conducted a study interviewing a focus group of five Jordanian women from difference career paths and marital statuses as well as the JWU. According to the general manager of the JWU, there are two main factors that affected Jordanian women's participation in the workforce: traditional cultural restrictions and political reasons. According to her, "Women present 52% of Jordanian society. Accordingly, half of our society is inoperative in the production process, and

surprisingly that by the increasing level of women education and the rate of turnout on education, women still represent 14% of the Jordanian workforce." She adds "Marriage sets some

responsibilities on women, so that all the work distribution may be against women" Therefore, marital status in Jordan is considered to be an important factor in retention. Moghadam (2013) states that social perceptions differ for single and married women in Jordan. The conclusion of the

interview and the IE framework developed by Khalaf et al. (2015) is that internal factors are interconnected and cause ripple effects within the pipeline of women. Female employees in Jordan leave the workforce likely due to a lack of motivation and productivity. In the interview, women themselves openly stated that being a mother is their primary job and that any role outside the home is secondary (Majcher-Teleon & Slimene, 2009)

East Asian Countries

We group Malaysia and Indonesia to ease comparison under one umbrella. Both countries are largely Islamic but are non-Arabic speaking, and both have large developing populations with a high

percentage of female penetration in STEM-related education. An important observation to note is that women's average STEM scores were significantly higher in Malaysia and Indonesia than those of than their male counterparts as early as grade 8, as shown in Table 5.

Female

Male

Female

Male

Australia

Hong Kong- China

500

588 509 583+9

-5511

536 527 534 +16 -2 Indonesia 392 379 -13 409 402 -7Iran

411

418

+7

477

472

-5

Japan

566

574

+8

554

562

+8

Kazakhstan

486

488

+2

434

419

-15

R k ra 616 +61

55 563 +Malaysia

449 430 -19 434 430 -4New Zealand

Singapore

Thailand

Turkey

478 615 435 457 4% 607 417 448 +18 -8 -18 -9501

589 458 491522

591

443 475 +21 +2 -15 -16Figure 6- Differences in STEM scores by gender across countries

Malaysia

Similar to the previous countries discussed earlier, Malaysia also lacks a strong literature on female workforce analytics. The literature shows that the Malaysian female workforce increased during the 1970-1990s but experienced a sharp decline afterwards. In 2008, the female labor force participation rate was around 45%, which is the lowest by far in comparison to other Southeast Asian countries. In a national survey conducted in 2008, 4.7 million women labeled themselves "out of the labor force," and, of them, 3 million cited "housework" as the reason behind their unemployment (Malaysia, 2009).

The Human Resources Ministry stated that Malaysia has an untapped idle workforce of around 1.5 million women who have difficulty being employed due to various cultural constraints. According to

a study conducted by Frank and Olsen, 2008 who interviewed 80 Malaysian women, some women mentioned that women are largely expected to conform to traditional gender roles whereby the husband is the head of the house and has the final say with respect to his wife's employment

(Abdullah & Noor, 2008). Recent efforts to find workaround solutions to increase female employment rates have included corporations establishing telecommuting jobs.

A questionnaire survey conducted by Abdulazeez Hamsa et al. (2016) on a population of 64,000

female workers in Malaysia, representing a quarter of the nation's workforce and comprising women in the financial, baking, real estate, education, and telecommunication sectors, led to interesting results. More than half of the women were married, and 43% of them had children who require childcare. In addition to the burdens of childcare, a high percentage of respondents indicated that they were responsible for caring for elderly parents as well. We find a pattern of high educational attainment in Malaysia as well, with over 67% of respondents holding Bachelor's degrees, a quarter holding Diplomas, and around 5% relying on a high-school education. Despite such a high rate tertiary education, the nation's economy could suffer due to low retention rates of women in the workforce.

Indonesia

Indonesia, a populous country with tremendous potential for economic growth, has an annual grown at a rate of 2% over the last five years (BPS, 2013). The pattern of a high rate of tertiary education found elsewhere holds for Indonesian women as well, as they outperform their male counterparts in some subjects, as shown in Figure 6.

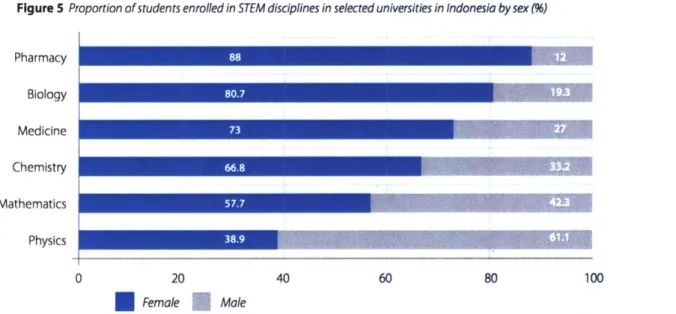

Figure 5 Proportion of students enrolled in STEM disciplines in selected universities in Indonesia by sex (%)

Pharmacy Biology Medicine Chemistry Mathematics Physics 0 20 40 60 80 100 Female Male

Note: All data presented in this figure is based on enrolment rates at the undergraduate level at the Bandung Institute of Technology and the

University of Indonesia (Jakarta), with the exception of pharmacy, which is based on data from Gajah Mada University. Source: DoHE, 2014; Yogyakarta Statistics, 2013.

In addition to economic growth, new policies have been put into effect to push more women into the workforce in Indonesia. Chief among them is the implementation of the Equal Employment Opportunity strategy (MMTRI, 2005). This strategy is primarily intended to achieve gender equality in the workplace. Despite political efforts to close the gender gap in Indonesia, the women's

employment rate is still stagnating at 37%. This gender gap has affected Indonesia's placement on the Gender Inequality Index, and till 2011, Indonesia was one of the lowest-ranked Asian countries, as shown in Figure 8.

Gender Inequality Index (Gil) Trends in ASEAN

Countries, 1995-2011

0.6

-

Indonesia

0.5

0.4 -

Malaysia

0.3

M

Philippines

0.2

E

Singapore

0.1

0

_Thailand

1995

2000

2005

2008

2011

UViet Nam

Figure 8-Gender Inequality Index in ASEAN Countries

There is a substantial literature on the dynamics of women's employment in Indonesia. Pinagara and Bleijenbergh (2016) outline a dynamic systems model of the various factors that affect women's employment. Building on a standard human resources-based model illustrated in Figure 9, a factor called Gender Role Ideology (GRI) significantly shifted the dynamics for women seeking diversified roles in the economy. According to the authors, state and political efforts have very little effect on societal ideology, according to which women in Indonesia are expected to have a stellar education, perform well in tertiary schooling, and then remain in the household to care for her children and spouse. The GRI factor has a negative impact on the hiring rate for women, which in turn increases the hiring rate for men and implies more men into the Indonesian workforce.

0 Wo,1ne Z .|

Gender Role + HiringRae bynent Leaving Rate

Ideolgy Wonn Worn

Hiring Proportion

Average Tim to Fil Average Duration of VacanciesEpymn

Vacancies

V4- Men

Hiring Rate Men Leaving Rate Men

Figure 9-System Dynamics stock and flow diagram on Gender Role Ideology

The results from the model are significant and compelling; the authors predict that without significant changes to gender ideology, women's employment rates will remain the same in the decade to come, stabilizing at an equilibrium of 38%. The authors suggest stronger implementation procedures in addition to national policies to stimulate women's hiring rates. Since societal ideology in the model is at 10% strength, the authors quantitatively prove that if the GRI shifted to 0.5, women's employment would reach a high of 50% by the end of the next decade, increasing female penetration in the labor force.

Cultural Overview

The countries studied are all Muslim majority countries, and all equally members of the international Organization of Islamic Cooperation of 1969. Comprehensively, 50 countries have Islam as the dominant religion. Each of these countries, however, have differing customs, traditions, ways of life, understanding of religious tradition, and cultural dynamics. Each country interprets religion

differently, some more orthodox than others. In many instances, tradition enforces a patriarchal view that fuels segregation policies and outlooks.

From an anthropological perspective, it is important to note that all Gulf States derive their political elite, legitimacy to rule, and authenticity from their histories as closely knit tribes, where concepts such as family honor, chivalry, and alliances built or broken by marriage dominated the political landscape. Such methods were required in order to ensure the tribe's survival, growth, in the harsh,