Defining Transit Oriented Development (TOD) Potential

Along the Commuter Line Stations in Jakarta

By

Jonathan Todo Hasoloan

Bachelor of Science in Architecture Institut Teknologi Bandung Bandung, Indonesia (2012)

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018

2018 Jonathan Todo Hasoloan. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter

created.

Signature redacted

Author

Department of Urban Studies and Planning (May 24, 2018) Certified by_ Accepted b

Signature

/

redacted

Mary Anne Ocampo Thesis Supervisor Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Signature redacted

MASSACHUSETS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

JUN 18 2018

Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning

DEFINING TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT (TOD) POTENTIAL ALONG THE COMMUTER LINE STATIONS IN JAKARTA

By

Jonathan Todo Hasoloan

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24th, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning

ABSTRACT

Transit oriented development (TOD) has been an emerging concept in Jakarta, particularly since the construction of the new Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) and Light Rail Transit (LRT). Besides the two

incoming new transits, Jakarta operates an existing Commuter Line, which has a significant ridership, even compared to the forecasted ridership of the MRT Line and the LRT Line, and an extensive

network coverage across the metropolitan area. The emerging TOD in Jakarta mainly focuses on producing typical vertical mixed-use development, though there are supposed to be many TOD approaches that encompass various scales in response to different contexts. This thesis seeks to

provide a comprehensive approach to achieve a sustainable TOD, using the Commuter Line as the case study

Two imperative studies in TOD planning are combined in this thesis. The first is to investigate TOD as a network of different node, place, and market values. This thesis adopts the Three Value (3V) Framework, which is developed by Salat and Ollivier (2017) for the World Bank. The interplay of the three values distinguishes the development potential of each station and helps create a series of TOD typologies. The second is to investigate station neighborhood as an area for development itself. From the first study, three stations are considered as TOD areas and are selected as case studies to understand the prevalent urban fabric around the stations and how future development could and should transpire on such fabric. The combination of the two studies could help decision-makers better allocate and prioritize different development approaches within the Jakarta transit network to achieve a sustainable TOD.

Thesis Advisor: Mary Anne Ocampo

ACKNOWLEDGMENT My greatest gratitude to you:

DUSP and MIT, for the magnificent experiences that I never have imagined to have. I learned so much from the MCP program and the cohort, amazing individuals and their innovative minds -- the great future urban planner of the world. I am more than fortunate to be a small part of it. The Guadalajara

practicum class and the Guadsquad, for adding another TOD exposure through a memorable journey. Mary Anne Ocampo, my thesis advisor, for dedicating her time to support me through this thesis to the very last errand. Chris Zegras, for being a rigorous reader I know that this thesis is not perfect, but it has been a precious learning process. Sam, for being an amazing friend by sparing his precious time to proofread my script.

LPDP Indonesia, for sponsoring this impossible dream. I owe my country a huge contribution. Ema of DCKTRP Jakarta, the Jakarta Planning Agency, and PT Kereta Commuter Indonesia, for providing the relevant data for this thesis. PSUD, for all the precious work experiences that brought me to the world of urban design and planning.

Foremost, my parents, my brother Theo, and Rachel, for the unwavering love, support, and prayer.

/ can do all things through Christ which strengtheneth me. Philippians 4:13

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.. ... ... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENT ... 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ... 1.1 Background . . . . 1.2 Research Questions. . . . . 1.3 Methods. . . . . 2. LITERATURE STUDY ... 2.1 TOD Principles . . . . TOD is Place-making . .. . . . . TOD and Urban Design . . . . TO D Typologies . . . . 2.2 Sustainable Development . . . . Econom ic Sustainability . . . . Environmental Sustainability . . . . Social Sustainability . . . . Sustainable TO D. . . . . 2.3 Conclusion: TOD is a Holistic Approach . . . . . .. . . . 8 ... 10 . . . . ... .o 11 .. .... 11 . .... . . . . . .13 . . . . 14 .16 18 .19 .19 20 .21 21 2 CnITEVT ANAIVIC 3.1 Transit System. 3.2 The Emergence of Transit Oriented Development . . . . 3.3 TOD Planning and Regulation . . . . TOD in the Ministerial Regulation. . . . . TOD in the Jakarta 2030 Regional Spatial Plan (RTRW 2030) . . . . TOD in the 2014 Detailed Spatial Plan Document (RDTR 2014). . . . . Governor Regulation about TOD Management . . . . 4. STATION CATEGORIZATION ... 4.1 Node Value . . . . Degree of Centrality. . . . . Closeness Centrality. . . . . Betweenness Centrality . . . . Daily Ridership. . . . . Intermodal Diversity. . . . . Lessons Learned: Node Value. . . . . 4.2 Place Value . . . . Density of Street Intersections. . . . . Walkshed Ratio . . . . Diversity of Uses. . . . . Density of Amenities . . . . Lessons Learned: Place Value . . . . . . ... 23 . . . . 25 ... 28 ... 29 . . . . 30 . . . . .3 1 . . . . .. 3 1 . . . . 32 ... 33 . . ...33 . . . . 34 . . . . 34 . . . . 34 . . . . 3 5 . . . . 3 5 . . . . 37 . . ...37 . . . . 38 . . . . 38 . . . . 38 . . . . 3 9 . . . . 3 9 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.3 Market Value . . . .

Land P rice . . . . . . . . . .

Development Capacity . . . .

Lessons Learned: Market Value . . . . 4.4 Result: TOD Categories. . . . .

First Tier Station: Immediate . . . .

Second Tier Station: Emerging . . . .

Third Tier Station: Incremental . . . . 4.5 Evaluating the Designated TOD Districts . . . . 4.6 Additional Insight on the Regional Scale Analysis . . . . 5. NEIGHBORHOOD STUDY . . . .

5.1 Station 1 - Tanah Abang .

Land Use and Activities . . . .

Urban Form . . . .

Zoning Regulation Interpretation . . . . 5.2 Station 2 - Sudirman . . . .

Land Use and Activities . . . .

Urban Form . . . .

Zoning Regulation Interpretation . . . . 5.3 Station 3 - Manggarai . . . .

Land Use and Activities . . . .

Urban Form . . . .

Zoning Regulation Interpretation . . . . 5.4 Findings . . . . 5.5 The Challenge for Sustainable TOD . . . .

Dense Low-rise Fabric Holds the Key . . . .

Large Scale Development is Desirable with Various Station Categories as Reconciliation Tool . . . . .

Walkable Environment is a Compulsory Quality Pushing TOD Further as a Green Development

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .r.c.n.i.i.n. . . . . . . . . . . . 42 42 42 43 44 45 45 46 48 49 51 . . . . 54 . . . . 54 . . . . 55 . . . . 56 . . . . 60 . . . . 60 . . . . 60 . . . .6 1 . . . . 65 . . . . 65 . . . . 66 . . . . 66 . . . . 70 . . . . 75 . . . . 76 . . . . 78 . . . . 79 . . . .8 1 . . . . 83 6. CONCLUSION ... 6.1 General Lessons... 6.2 Future Studies . . . . 7. REFERENCES... ... APPENDIX A: THE JAKARTA TRANSPORTATION MAP . . . . 85 85 86 87 . . . .. . 91

APPENDIX B: THE NODE VALUE CALCULATION . . . . 92

APPENDIX C: THE WALKSHED BOUNDARY. . . . . APPENDIX D: THE PLACE VALUE CALCULATION. . . . . APPENDIX E: THE LAND PRICE SUB-INDEX CALCULATION . . . . APPENDIX F: THE MARKET VALUE CALCULATION . . . . ... 93 ... 95 ... 96 ... . . . 97 . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Jakarta is an emerging megacity with prevalent urban issues in the global south that include over-population, congestion, and increasing inequality within a rapidly urbanizing context. Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) Indonesia revealed that people in Jakarta spend two hours in traffic on average for each trip (The Jakarta Post, 2015). Furthermore, Jakarta has the world's most congested traffic (Greenfield, 2015). Such conditions certainly create a negative impact on people's daily life in Jakarta. According to the National Planning Agency, traffic congestion has cost Jakarta, excluding the metropolitan area, 67.5 trillion Rupiah ($4.82 billion) during 2017 (Sari, 2017). The public realizes that something has to be done to address this situation.

Currently, Jakarta is expecting its new rail-based public transit to mitigate the worsening traffic. The new MRT line is expected to operate in 2019 and the LRT, which was initially planned to serve the 2018 Asian Games, will also be operating soon. In addition, there is also the existing Commuter Line, which was modernized in 2011. PT KCI, the operator of the Commuter Line, restructured their internal organization, introduced automatic tap machine, refurbished trains, and renovated stations. The image of the Commuter Line has been significantly altered since and it has become a major transit options in Jakarta.

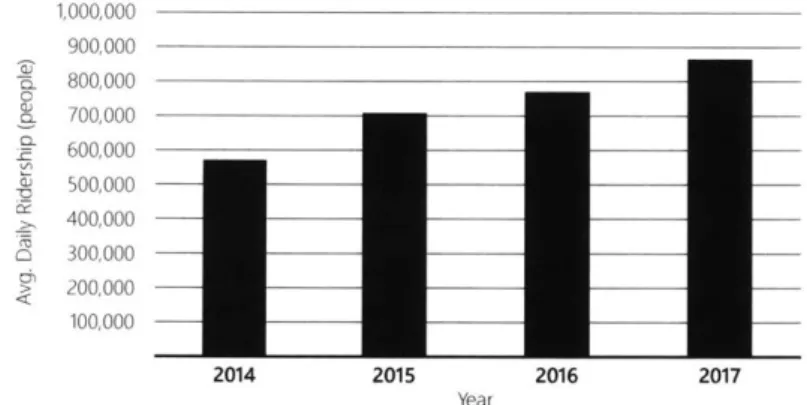

Though the Commuter Line service is still far from ideal, it currently has 865,342 average daily

ridership -- based on the riderhsip data provided by PT KCI. In comparison, the new MRT line and LRT line are forecasted to have 173,400 and 360,000 (Rahmadi, 2017) daily ridership, respectively. These ridership figures show the significance of the Commuter Line in serving the urban mobility in Jakarta. Next year, the Commuter Line is targeting 9.5% increase ridership. The Commuter Line will continue to add the rolling stocks and improve station facilities to achieve their target. Furthermore, since

urban land is becoming scarce and more expensive, the extensive network of the commuter railway and its stations is a crucial asset for future mobility infrastructure in Jakarta.

The massive transit investments and, arguably, the paradigm shift in using public transit have attracted many transit oriented developments (TOD). TOD is now an intriguing concept. TOD is an effort to integrate urban development with transit network through a compact and walkable development in order to encourage transit usage and achieve a more efficient urban mobility. TOD is currently one of the forefront planning initiatives for the provincial government, a strong development branding for developers, and emerging lifestyle for the general public.

As intriguing as it is as a concept, the implementation of TOD in Jakarta is nascent. TOD is being implemented mainly as vertical development that focuses on densifying areas around transit station. Though this is not entirely wrong, there may be missed opportunities in how urban development

might be planned and designed with a TOD framework. Therefore, this thesis seeks to provide a holistic approach to TOD planning by recognizing that TOD should be a set of interconnected implementation strategies that take different forms.

In the absence of appropriate development guidelines coupled with the fact that well established institutional framework and planning order were lacking, these new breed of developers were competing with one another in acquiring large tracts of land in and around Jakarta. They later came to the government with their own version of planning and design

schemes and placed requests for approval. Thus, instead of government's comprehensive planning provides guidelines for project development, it was the project proposals, which became the reference for the formulation of official plans. (Danisworo and Prasetyoadi, 2015, p. 208)

The quote above from the urbanism pundit in Indonesia asserts the adverse reality of urban

development in Jakarta that is conspicuously market-driven and top-down, but also lacks of visionary and comprehensive planning. Hitherto, urban expansion is a product of piecemeal and incoherent developments. Many of these large urban projects are exclusively superior, well-designed, and

equipped with plethora of amenities, but they enclave themselves from the surrounding context. TOD should be able to offer a new development paradigm that could unify various stakeholders and goals to achieve sustainable development.

1.2

Research Questions

This thesis is a response to the author's apprehension of possible TOD misconception or rudimentary implementation in an emerging context such as Jakarta. Since development pace and excitement around TOD is fairly high, the Jakarta Government should optimize planning and urban design as tools to accommodate sustainable TOD. The government, in that sense, plays a significant role as the city manager, who coordinates urban development and mitigates trade-offs to accomplish optimum outcomes. The TOD objective is inherently to achieve efficient movements in the city by matching the transit system and the urban development.

TOD ideally should optimize the interconnected nodes within a transit network to create a synergistic and diverse development. Therefore, if TOD could and should occur across different parts of the

city, then this thesis raises a research question: how are TOD stations along the Commuter Line distinguished within Jakarta? The question searches for an appropriate categorization method that can be used by decision-makers to guide developments and to establish appropriate strategies in TOD planning. The stations could not be equally developed as a generic or typical TOD, because the resources for urban development are limited and each station has its own urban characteristics.

Subsequently, as the categorization may differentiate the scale and the form of development, this thesis raises complementary questions: how can TOD be sustainably implemented in their unique

context? What are the existing urban characteristics and elements that are relevant to TOD principles? What spatial adjustments are required? Because, TOD is inherently a form of urban development that eventually should seek to increase human welfare and livability. Sustainability framework is seen

as the necessary perspective for urban development, including a transit oriented one. Sustainable development principles will help decision-makers in accommodating various development conflicts and trade-offs, which are always inevitable in planning urban development.

1.3

Methods

The first part of this thesis will explore literatures surrounding TOD and its relation to various built environment aspects. This theoretical study will conclude the principles of good urban design and sustainable development goals for TOD, which underlie the subsequent neighborhood analysis. This literature study also provides a justification for the thesis to initiate a holistic analysis of the whole corridor of the Commuter Line. The analysis will be limited to the stations within the Jakarta Province, although the Commuter Line runs through the metropolitan area, because there was limited data available for the areas outside the Jakarta Province.

For the holistic analysis, this thesis adopts the Three-Value (3V) Approach, developed by Salat and Ollivier (2017) for the World Bank, which encompasses node, place, and market values to determine TOD typologies. Several modifications to this method was necessary due to the limited data available in Jakarta, though maintaining its efficacy was important to provide an initial basis in distinguishing the different TOD potential across stations. The 3V methodology is further elaborated in chapter 4.

Subsequently, the neighborhood analysis will select three stations as the case studies. The

investigation combines field observation, secondary research on the context, and spatial analysis in order to understand the prevailing urban characteristics around the commuter stations. From that, this thesis synthesizes the relevant spatial interventions in relation to the sustainable development goals, drawn from the literatures, to eventually propose the challenges to implement sustainable TOD and that the typologies could be incorporated in the decision-making process.

2. LITERATURE STUDY

The literature study provides the basis for how this thesis approaches the study of TOD since the concept is multidimensional and multidisciplinary. In this thesis, TOD is framed within urban design and development studies, therefore this chapter elaborates several theories and principles about the relationship between the built environment and TOD. This study also explores sustainability concept in urban development, particularly TOD, in order to extract a set of comprehensive objectives of TOD.

2.1 TOD Principles

The strong relationship between urban development and mobility has always been the case since the invention of wheel, streetcar, automobile and highway, and now the mass rapid transit. It encouraged development of new economic centers, increased density, and expanded the cities --in other words, a generator of growth. Uncoordinated growth will pose a future threat and lead to the missed opportunity of optimizing massive infrastructure investment, thus not allowing the city to capitalize the virtuous cycle of leveraged mobility and development (Cervero, 2013).

Thus, what is TOD?

A Transit-Oriented Development is a mixed-use community within an average 2,000-foot walking distance of a transit stop and core commercial area. TODs mix residential, retail, office, open space, and public uses in a walkable environment, making it convenient for residents and employees to travel by transit, bicycle, foot, or car. (Calthorpe, 1993, p. 56).

[...] integrated urban places designed to bring people, activities, buildings, and public space together, with easy walking and cycling connection between them and near-excellent transit service to the rest of the city. (ITDF) 2017, p. 8)

TOD is a tool to manage growth and to encourage sustainable development in the city It occurs in multiple scales: neighborhood, city, and regional. The implementation requires a holistic strategy across many scales. TOD as a concept was introduced by Peter Calthorpe in early 1980s, commonly associated with compactness, diversity, walkability, density, and good transit service. It is often seen as the panacea to urban sprawl and unsustainable development -- but if only being implemented prudently Some argue that the concept itself is an evolution of the previous movements such as the new urbanism and the smart growth, and thus their objectives often intersect in many aspects.

Transit investments and services are incapable by themselves to trigger significant land-use and urban form changes without public policies that leverage investments. Experiences in Europe and Canada underscore the importance of coupling rail investments with reinforcing local policies such as up-zoning around stations, supplemental acquisition, joint development of station-area land, and situating publicly provided housing near stations. (Cervero & Seskin, 1995, p.5)

Cervero & Seskin (1995) concluded that there are two imperative forces that should exist for successful TOD: policy and the market. Significant transformations do not happen spontaneously without any initiatives from those sectors. TOD will take place if there are actions that coordinate the different forces and stakeholders, and one of is planning.

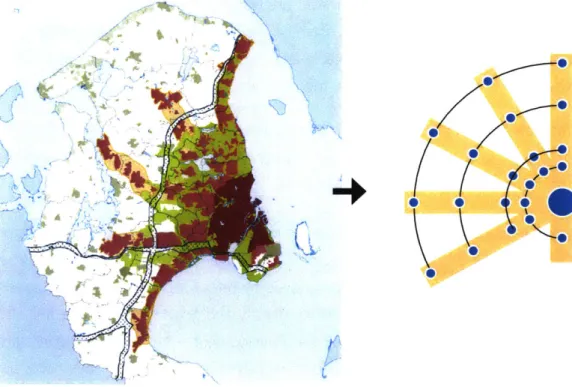

Drawing lessons from Europe and some Asian countries, the implementation of TOD needs to be complemented by comprehensive planning. Cervero (2016) emphasized the necessity of formulating a vision and a conceptual image of the future metropolis such as the Finger Plan in Copenhagen and the Planetary Cluster Plan in Stockholm. The Finger Plan, without actually branding itself as TOD, defined growth axes along a transit network - creating a finger-shaped urbanization. Singapore, often referred as a successful example of TOD implementation, had the Constellation Plan which combines

4/t r

'AL

0 0 (0 0 0Figure 2.1 The Copenhagen Finger Plan

compact and mixed-use development around many MRT stations. This constellation consists of satellite nodes with specialized functions that interact and complement each other, which also encourages movement between nodes - encourage ridership.

In general, the main idea is to have a heterogeneous built environment along the transit line to allow synergistic interaction among the different parts of the city, because the city itself is naturally heterogeneous. In this case, creating typologies for TOD based on the knowledge of the different contexts is a more nuanced approach in working within this heterogeneity.

In a simple concluding remark, TOD can be perceived as an effort to bring people and activities toward transit station. The "effort" refers to the various means in transforming the built environment. "Towards transit stations" refer to the proximity to transit station and thus emphasizes on the

walkable environment. "Bringing people and activities" refer to the mixed of uses and people and the appropriate density. Cervero and Kockelman (1997) summarized the TOD relationship with the built environment into the 3Ds -- density, diversity, and design with further additions of distance to transit and destination access.

TOD is Place-making

Place is the convergence of the spatial design, the people who use the space, and the activities - how people use the space. Hence, place-making is the best practice of good space design that is catered to the people and communities who are using it. It allows physical, cultural, and social identities to define the place. Bertolini (1996) perceived station as node of networks and a place in the city at the same time. He argued that TOD is an effort to balance the nature of mobility and community, turning the transit station into a "place to be" rather than simply "a place to pass through". Bernick and Cervero (1997) describe TOD from the perspective of place-making as follow:

The centerpiece of the transit village is the transit station itself and the civic and public spaces that surround it. The transit station is what connects village residents and workers to the rest of the region, providing convenient and ready access to downtowns, major activity centers like a sports stadium, and other popular destinations. The surrounding public spaces or open grounds serve the important 27 function of being a community gathering spot, a site for special events, and a place for celebrations - a modern-day version of the Greek agora. (p.5)

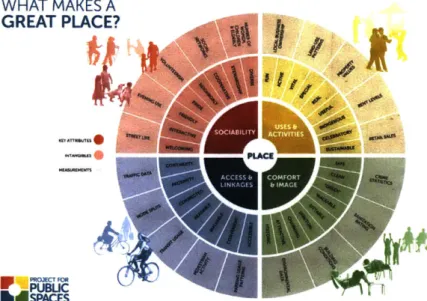

In this sense, TOD is not always about introducing new development that often alienates the existing environment. Instead, TOD should enhance the existing virtues and alleviate the

prevailing issues. This is a very ideal principle yet arduous to implement. Project for Public Spaces (PPS) comprehends four qualities that constitute place-making: they are accessible; people are engaged in various activities; the space is comfortable and has a good image; and finally, it is a sociable place, a melting pot where people meet and interact with each other. PPS summarizes these four qualities and the relevant characteristics into the diagram below. They reasonably align well with TOD.

WHAT MAKES A GREAT PLACE?

-U -eMA P A C T IE 0

-I,1

Figure 2.2 The attributes to a great place

Source: Project for Public Spaces

TOD and Urban Design

Public transit is a point-to-point movement and public realm exists between the points -- points

are the stations and the destinations. Public realm is the base for every first and last-mile of a trip, which ideally are served by non-motorized modes like walking or biking. This implies that public space design, particularly in relation to walkability, is an inseparable element of transit activities. Even a door-to-door transportation will require certain integration with the design of public realm - parking and drop-off area are examples.

Transit is a utility based decision and people's preferences are typically to maximize their individual utility function. McFadden (2000) suggested that there are two main determinants to people's decision-making process. The first is the internal and intangible aspects that are formed by one's personal experiences and memories. This is the preference. The second is influenced both by the individual memories and the external aspects that creates one's belief or perception. Both preference and perception are the input to the decision-making process.

In transit decision-making, both determinants could be influenced by the condition of the built environment. Several studies have investigated and confirmed the relationship between built form and transit activities, although the magnitude of the impact differs in various contexts and studies (Cervero & Seskin, 1995; Cervero and Kockelman, 1995). Therefore, influencing (transit) choice is highly possible through designing a more convenient experience, by practicing good urban design and planning. A particular urban design approach may deliberately favor pedestrian and bicycle spaces in order to promote a more walkable area, which is desirable for TOD.

Innovative design and marketing strategies are also effective to improve perception toward public transportation (uses). The Regional Metro System in Naples and Campania combines transport infrastructure with architecture, contemporary art, and archaeology as marketing tools (Cascetta and Pagliara, 2009). This exciting strategy, partly place-making, is crucial especially for a context where public transit is often associated as an inconvenient option.

There are only few studies that meticulously elaborate the urban design aspects of TOD, but some of the most relevant elements of urban design for transit activities can be extracted from the to design principles for a walkable and livable city Ewing and Clemente (2013) suggested the following criteria to define the quality of urban design:

- Imageability is about the quality of a place that makes it memorable. It may be produced by one or a combination of many elements of urban design that capture attention and leave impression on the users. Imageability is also considered as the net result of the other urban design qualities.

- Legibility: refers to easy navigation and orientation of the spatial structure. This is a very important element in TOD because it emphasizes that connectivity should be practically feasible in the field for users - not simply possible based on network analysis.

- Enclosure: is the room-like quality of the place as defined by buildings, walls, trees, and other vertical elements. It is highly influenced by the proportion of the space - the width and the height of the volumetric boundary

- Human Scale: refers to the ergonomic of the built environment, how all aspects fit into human nature - form, movements, speed, etc. This human-scale consideration become relevant since technology advancement have introduced various new urban dimensions that do not always cater to human nature, like automobile.

- Transparency: refers to the visual access towards the surrounding environment.

- Linkage: refers to the connection between urban spaces - between public and private spaces and between themselves.

- Complexity: refers to the variety of urban elements that create rich urban experience.

- Coherence: refers to the consistency of urban characteristic that ties a place into a sensible

place. Complexity without coherence is chaotic and vice versa, coherence without complexity is boring.

These criteria resonate with and adopt many theories around the study of the quality of urban design (Lynch, 1984; Jacobs, 1993; Jacobson & Forsyth, 2008; Speck, 2012).

TOD Typologies

TOD is a very demanding concept that can align with a plethora of good development principles. Unfortunately, resources are limited and trade-offs are inevitable for many development endeavors. Therefore, TOD should never be seen as independent individual development across the city and offered as one type solution for all (Calthorpe, 1993; Suzuki, Cervero, and luchi, 2013; Salat and Ollivier, 2017). TOD should exploit the nature of transit system as an urban or even regional system which forms interconnected nodes (stations) within various contexts.

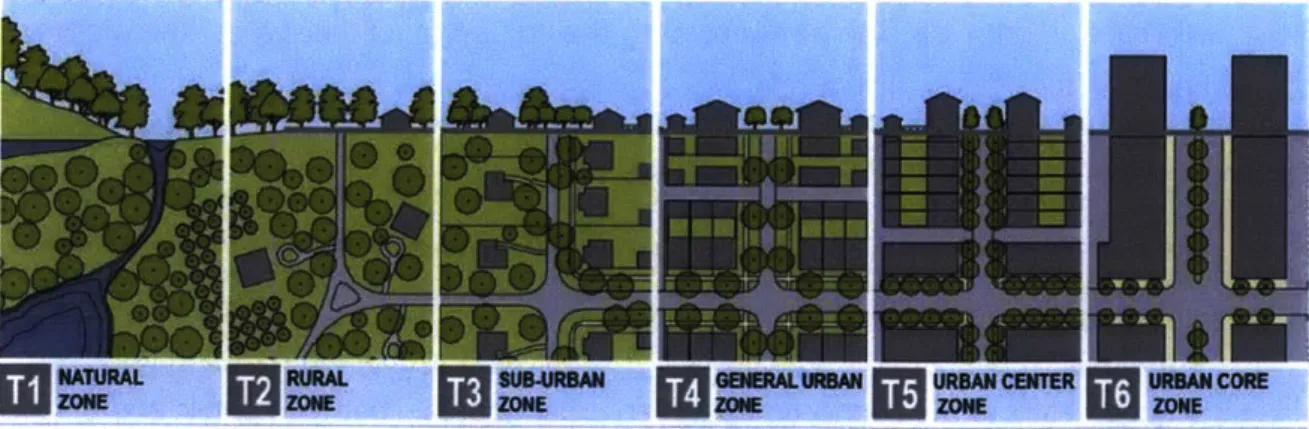

The continuum of different contexts could best be represented by a transect. Transects have originally been used as an analytical tool by scientists, like Alexander von Humbolt, to describe the idea that there is an appropriate place for all different development types. Duany Plater-Zyberk (DPZ) adopted the concept of transect as a master planning tool that differentiates the built environment and utilizes design guidelines to create a context-sensitive built environment. Dittmar and Pinzon (2009) further developed guidelines for TOD in the Smart Code 9.2, based on this transect approach. They excluded rural and sub-urban classification that existed on the initial transect. The TOD transect is grounded in the understanding that urban and rural areas response to different urban form, which subsequently defines what the ideal urban form is.

NATURAL RURAL SUB-URBAN GENERAL URBAN URBAN CENTER URBAN CORE

ZONE

k

ZONE[aZONE

2MMNET5ZONE

M

ZONEFigure 2.3 The transect

The transect concept is applicable to TOD typologies because the extensive transit network that runs across different part of the city, or even connects different city, creates a geographical continuum of various urban or rural context. The interconnected network invites us to recognize the different feasible development around different station areas. Therefore, "TOD typologies aim at creating an aspirational vision of future land uses, prioritizing stations for investment, and providing guidelines and actions for implementation" (Salat and Ollivier, 2017, p. xxv).

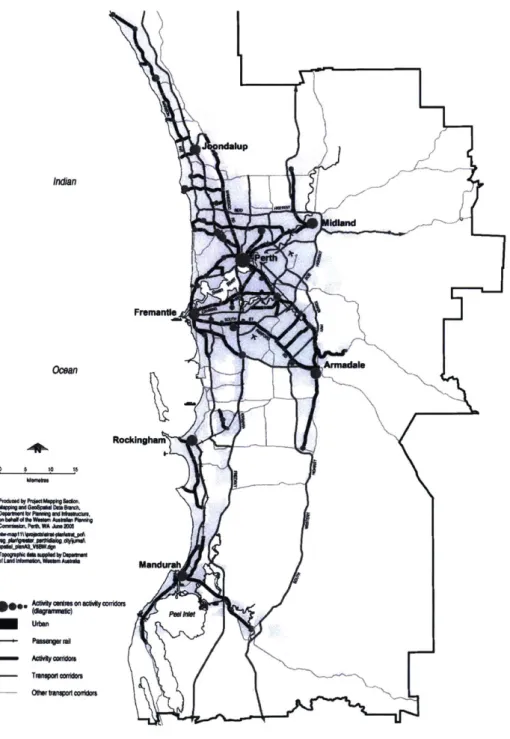

Indan Omean 0 6 10 IS Faft ,WA Ju S---I a ah Wanimr Pfn" rcs7dm co0bo

Figure 2.4 The Network City Plan in Metropolitan Perth Source: Curtis (2006)

ndolup

Fremonde

Rockdngh

In the 1990s, the city of Perth invested strongly in public transport and has since integrated their planning practice with TOD. The city came up with a planning strategy for the Metropolitan Perth called 'Network City' (see figure 2.3). The 'Network City' is a spatial framework comprising three interconnected elements: activity corridors, activity centers, and transport corridors. Curtis (2006) emphasized the importance of defining and planning for Activity Centers. In other example, Dittmar and Pothica (2004) elaborated a more detailed TOD classification into six different categories: urban downtown, urban neighborhood, suburban center, suburban neighborhood, neighborhood transit zone, and commuter town center. In conclusion, establishing TOD typologies is one of the initial milestone required to initiate a TOD planning (Suzuki, Cervero, and luchi, 2014; Cervero, Guerra, and Al, 2017).

2.2 Sustainable Development

Sustainability can be defined as a process or condition that can be maintained indefinitely without progressive diminution of valued qualities inside and outside the system where the process operated or the condition prevails (Daily and Ehrlich, 1992). The terms initially applied to the renewable

resources such as fisheries and forestry by limiting the rate of utilization to not exceed the natural reproduction rate or disrupt the ecosystem as the resource base itself Subsequently, the utilization of non-renewable resources and the establishment of urban context for human activities makes the concept of sustainability becomes more complicated to be implemented (Sarosa, 2002).

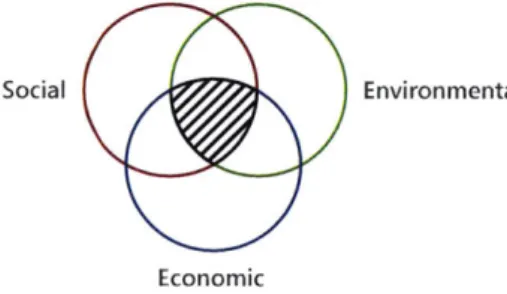

Social Environmental

Economic

Figure 2.5 The three elements of sustainability

Sustainability has certainly been a prominent principle in urban planning practice around the world. Although, this thesis argues that sustainability is rarely implemented as a comprehensive concept that fundamentally embodies the various perspectives - that are often contradictive. Early discourses

around sustainable development was dominated by economic and environmental perspectives. As the objective of development expands the definition of increasing welfare to not just simply about capitalization of resources, but also poverty alleviation and equality, sustainable development concept appends the social objectives into the equation. Barbier (1987) suggested three main elements of

economic, environmental, and social to comprehend sustainable development. Equally considering the three elements is necessary to consider the trade-offs in achieving progress. This is especially relevant for the developing world where the urbanization rate and development impetus are arguably high.

Economic Sustainability

"Economic sustainability implies a system of production that satisfies present consumption levels without compromising future needs" (Basiago, 1998, p.150). It focuses on exploring and exploiting the available resources for maximum gain while ensuring the continuity of the process. Theoretically, the two main components are labor and capital.

The search for economic growth is the main driver of urban development. The capitalists have always found ways to capital extraction which often have encouraged innovations and technology advancement like new transportation and infrastructure. The system seeks for the better and best solution to utilize resources for optimum outcome. The term highest and

best use in real estate development highly resonates with this concept. Highest and best use considers the feasibility (physical, financial, and legal aspects) of a development to generate

maximum value.

Cities are fundamentally a (economic) growth machine, where economic activities are

concentrated in and people are attracted to. Urban planning and design are the tools to ensure that the economic gears will always rotate within the city. Basiago (1998) emphasized that the implementation of economic sustainability principle is inherently fulfilling public needs through good urban design.

Environmental Sustainability

Environmental sustainability is often perceived as the forefront of sustainability practice - as the most common. It refers to the preservation of natural resources for future uses as well as mitigating the impact of current development to the environment. Environmental consideration provides the necessary limit to the extent of economic-oriented development. Although the term is only recently used, the urban planning practice has been considering environmental

aspects to a certain extent. Some examples were Howard's Garden City and McHarg's Design with Nature which tried to integrate urban development with significant environmental consideration.

The recent concept of environmental sustainability within urban development could be manifested in the green urbanism movement (Beatley, 2015). The idea promotes a compact

and an ecological urban form. Beatley's elaboration of sustainable future concerned a lot on reducing the car usage and the carbon footprints of car-oriented lifestyle while enhancing the quality of life by doing so. In addition, environmental sustainability encompasses many

interconnected elements within regional and even national scale, hence it cannot be seen narrowly in practice.

Despite the emerging concern surrounding environmental issues, many solutions within the planning and urban design realm are being critique as a cliche. Jeff speck (2012) labeled

"pseudo-green" on green-certified architecture that do not inherently encourage green lifestyle. He argued that environmental sustainability has to be embedded in daily lifestyle through a systemic transformation in our urban system. The walkable city, as he elaborated in his book as the real solution to green lifestyle, is only possible through a set of comprehensive changes in our built environment. Lim (2011) expressed his critique to the approach to environmental sustainability as an eco-city syndrome, where solutions are focused on the sophisticated and the cutting-edge technologies that are agnostic to the local context and culture. He brings in social aspects in the equation where typical eco-city projects try to introduce brand new cities and invent a new culture, instead of embracing the existing social and cultural framework. Social Sustainability

Social sustainability is arguably the more recent concern in the framework, compared to economic and environmental sustainability. Urban developments have been revolving around the conflict between the economic forces and the environmental issues since the two are directly connected. The environmental issues have also captured more attention since their impacts are global, while the social issues are more localized and specific to a certain demographic.

Social sustainability emphasizes on the distribution of growths and development benefits to the different socio-economic groups. Capitalism does not inherently encourage social sustainability where it produces winners and losers. Although the concept of winners and losers ensures progress and innovation (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2013), the outcome often emanates a perennial inequality. The losers are trapped in the adverse cycle and the winners enjoy the privilege of progress.

Accessibility is an important factor in promoting social sustainability. An example is the equal access to employment opportunities or public amenities. Auto-oriented mobility tends to be unaffordable for most people and public transit should ideally be an answer this issue. Unfortunately, high-pace development often widens the gap between the two extremes and

eventually induces segregating urban forms. TOD, which resides more on the economic growth endeavors, is inherently market-oriented and often brings gentrification with it. Consequently, the objectives of TOD to increase accessibility for all and to promote effective mobility in the city could be undermined by the unequal access to the benefits.

Sustainable TOD

The indicators for sustainable development are cross-cutting, so it is hard isolate one to only a certain dimension of sustainability. Renne (2009) proposed a comprehensive set of goals to measure sustainability, which are:

- The travel behavior: the goal is to encourage mode shift to be more transit- and pedestrian-oriented. It can be measured by the vehicle usage and ownership, the pedestrian

accessibility, and the quality of transit;

- The local economy: the goal is to achieve thriving economic activities within station areas. It can be measured by the range and success of business and housing in the area, as well as the change in property value;

- The natural environment: the goal is to provide green and natural space to mitigate the

impact of development. It can be measured by the level of noise, pollution, energy use and water retention and infiltration;

- The built environment: the goal is to create an attractive and livable environment. It is

measured by the vibrancy, the attractiveness, the mixture of uses, the safety, and the proportion of people-oriented space;

- The social environment: the goal is to empower community through development. It is

measure by safety and security, sense of belonging (ownership), diversity, and opportunities for advancement;

- And eventually, the policy context: the goal is to incorporate TOD in the regulation.

These goals are proposed as a way to measure TOD success, but in this thesis, they will be used for TOD planning instead. Recognizing what the goals and measures (of sustainable TOD) are

helps frame the necessary interventions to achieve these goals and to promote a sustainable TOD.

2.3 Conclusion: TOD is a Holistic Approach

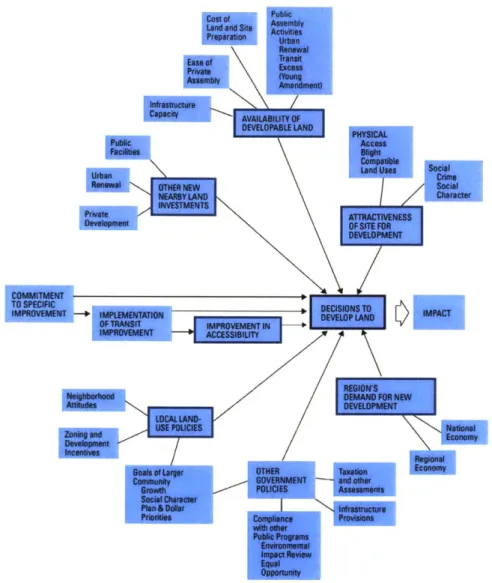

TOD should be approached holistically from two complementary scales: an urban scale and a neighborhood scale. Understanding both scales helps determine the appropriate interventions and especially where trade-offs should be made. The urban scale analysis assigns different hierarchies and

Public

Land and $it Assemblye Preparation Urban Renewal Ease of Transit

Private Excess

Assembly Amendment)(Young Infrastructure Capacty AVAILABILITY OF DEVELOPABLE LAND PHYSICAL Access Blight Compatible

Land Uses Social

UrbanCrime

Rene" OTHE NEWSocial

NEARB LANDCharacter

ATTRACTIVENESS OF SITE FOR

DEVELOPMENT

COMMITMENT

TO SPECIFIC ____________ DECISIONS TO r\IPC

IMPROVEMENT IMPLEMENTATION DEVELOP LAND MPACT

OFTRANSF IMPROVEMENT1N

IMPROVEMENT ACCESSIBILITY

AREGION'S

Goals of Larger OTHER T aONi

C nity O NMENT and other

USoEi POLUCIES Assessment

Zoc: ni and rygEc1n77.

Social Character Plan & Dollar

Priorities Compliance with other Public Programs Environmental Impact Review Equal Ougnunity a oure: Knight and Trygg 1977.

Figure 2.6 The diagram of TOD determinants

Source: Knight and Irygg (1977) cited in Suzuki, Cervero, and luchi (2013)

roles to an expansive transit system by understanding different existing contexts where the stations are located in and the relationship between them. Lim (1998) offered the term "hold and shift" in urban development where the government performs as the city manager, who coordinates and allocates development. The conceptual diagram by Knight and Trygg (1977) is a relevant summary of the various influential factors for TOD. TOD decisions are a result of the interplay between the land availability, place attractiveness, market value, and policy -- in addition to the transit system itself Finally, sustainable TOD objectives are the product of intractable development trade-offs. It requires TOD to create vibrant economic activities, affordable settlements, strong communities, walkable environments, and vast open spaces, all within station area. Because land is such a limited resource, any particular development will inevitably face conflicts and trade-offs amongst these goals.

3. CONTEXT ANALYSIS

Jakarta is the capital city of Indonesia and is administered directly by the provincial government -rather than a municipality The Jakarta Province consists of five municipalities: North Jakarta, South Jakarta, West Jakarta, East Jakarta, and Central Jakarta. Below the municipal administrative level are Kecamatan (District level), which are in turn divided into Kelurahan and Desa (Sub-district level). Besides this formal administrative division, each Kelurahan and Desa is composed of Rukun Warga (RW) and Rukun Tetangga (RT), the local community or neighborhood units. One RT generally consists of 10-50 families, while one RW consists of 3-10 RT. The administrative and community units are

potential planning instruments. Unfortunately, highly top-down approaches rarely involve the lower hierarchical units in the planning process, let alone the RT and RW which are not official administrative units. 2 9 5 3 F10 4 6 8 A0 5 10 20 Kilometers Legend: 1. Central Jakarta 2. North Jakarta 3. East Jakarta 4. South Jakarta 5. West Jakarta 6. Bekasi 7. Depok 8. South Tangerang 9. Tangerang 10. Bekasi Regency 11. Bogor Regency 12. Bogor 13. Tangerang Regency 14. Cianjur Regency

Population Density (people/km2)

_-_ < 2,000

w 2,000 -6,000

m 6,000 -10,000 - 10,000 -14,000 - >14,000

Figure 3.1 The administrative boundary and population density of the Jakarta Metropolitan Area

Jakarta, like many other mega-cities in the global south, has experienced massive urban expansion and agglomerated into a large metropolitan area. The Jakarta Metropolitan Area (JMA) consists of ten municipalities and four regencies, but a large portion of the population remains concentrated in Jakarta itself

As it has expanded, Jakarta has transformed into a polycentric city, although arguably with certain urban centers have remained dominant, especially where the business district and commercial

activities are concentrated. A study by Bertaud and Malpezzi (2003) suggested that a combination of public transit and individual cars is the effective means of transportation in cities like Jakarta. However, the fairly low density and moderate level of land use mix in Jakarta suggests that public transit is slightly less effective compared to individual cars (Hasibuan, Soemardi, Koestoer, & Moersidik, 2014), which is corroborated by Jakarta's terrible traffic condition today.

As the city has become increasingly polycentric, private developers have contributed to the disruptive, sprawling, and haphazard pattern of development. In fact, the activity centers designated in the official planning documents such as the West Primary Center and East Primary Center, have not thrived as much as other new large developments initiated by private developers. Developers have competed to introduce new towns and urban centers around the perimeter of the metropolitan area where land is cheaper, which have increased the number of people commuting daily to Jakarta. These precincts are connected mainly by highways, major roads, and, in places, by the Commuter Line. This development trend has been prevailing and remains attractive to developers. Several studies indicate that developers still expand their market to the satellite cities with new town development as the main business model (Firman & Dharmapatni, 1994; Firman, 2004). They offer a more affordable housing further from the city center accompanied by complementary amenities such as shopping centers.

On the other hand, the urban center has developed into an interesting convergence of extreme ends of socio-economic ladder, creating the dualism that characterizes urban development in Jakarta (Danisworo and Prasetyoadi, 2015; Firman, 2004; Kusumawjaya, 2004; Peresthu, 2002). This urban dualism refers to "the tension between formal-informal, planned-unplanned, rich-poor within urban development" (Winarso, 2011, p.164). "Urban villages" exist next door to sophisticated residential areas; informal commercial areas lie adjacent to modern malls and shopping centers; and kampungs are surrounded by modern office buildings, apartments, and condominiums (Winarso, 2011). This is a unique form of spatial segregation that can be both dangerous and beneficial at the same time. It is dangerous because it creates an exclusive environment for the affluent and may exacerbate social disparities and raise class conflicts. But it could also be seen as a sustainable form of diverse urban community and potentially create mutual symbioses between different economic groups.

TOD within the urban area will have to compete with this outward-oriented development trend while addressing the complicated dualisms of the urban core. TOD has to be able to perform as a cohesive endeavor that stitches and unifies the city and its diverse neighborhoods.

3.1 Transit System

Public transit has never been a strong feature of most cities in Indonesia, including Jakarta. The latest successful transit system in Jakarta was arguably the BRT line, Transjakarta, which is the world's longest BRT network and has been widely used since its opening in 2004. Transjakarta has an extensive

coverage throughout the city, although it fails to maintain reliable frequency and headway particularly because of the disjointed dedicated busway, so buses are still stuck in congestion.

awai

0_

Population Density (people/kn2)

r- < 2,500 m 2,500 -5,000 - 5,000 - 10,000 m 10,000 - 15,000 - 15,000 - 20,000 = 20,000 - 25,000 = 25,000 -30,000 - > 30,000 0 2.5 5 10 1 1 a111111

--

A

Figure 3.2 Overlay between population density at sub-district level and the location of the commuter stations Source: Badan Pusat Statistik and Open Street Map

The only operating rail-based transit today is the Commuter Line, which serves the metropolitan area. The Commuter Line was significantly improved and modernized in 2011 and has since been experiencing a ridership increase. An automatic ticketing system, train refurbishment, station renovations, and, arguably, the recent spread of the transportation network companies (TNCs) and ride-sharing technology together have helped to transform the Commuter Line into a convenient transit option.

The Commuter Line has an extensive coverage throughout the metropolitan area. PT KCI (Kereta Commuter Indonesia), the corporation that operates the Commuter Line, is now operating 75 stations serving the whole JMA. It connects the urban center with substantial residential pockets around the perimeter Figure 2.2 shows that the Commuter Line network aligns quite well with the densest sub-districts. Since the Commuter Line operates on urban infrastructure that has been in place since 1925, many stations that were previously in the outskirts of the city are now located within the urbanized area. 1,000,000 900,000 ' 800,000 o 700,000 600,000 500,000 400,000 2 300,000 > 200,000 100,000 2014 2015 2016 2017 Year

Figure 3.3 The Increase of average daily ridership of the Commuter Line

Source: PT Kereta Commuter Indonesia

In the next two years, Jakarta will be operating a new MRT line and LRT line. These projects have been hailed as imperative infrastructures that Jakarta should have had for quite some time now - Bangkok had its Skytrain in 1999, Kuala Lumpur opened its monorail in 2003, and Singapore opened its first

mass rapid transit (MRT) in 1987. The new MRT line and LRT are both only a small part of the larger planned network. They may struggle to significantly impact accessibility in Jakarta and attract high ridership right away

The Ministry of Transportation has targeted a significant increase of transit usage from 26% of the modal share in 2016 to 40% in 2019. This requires a major paradigm shift in transportation system in Jakarta's transportation system. It is a good ambition that can only be achieved through an integrated

(SATELLTNort CoY)aetsriar

Recsamatio

industrial Park

The old City

AIRPORT

Conveton

-- LR~ine 0 2. 5 1 Kiloeter

TANGERANG Center

(sATELUr CITY) 'West Primary

Center

- BEKASI

- (sAWELITE CTY)

CB

-BSD

(NEW CITY DEVELOPMENT)

Leg d

+-o MRT Station with TO Designation

---MRT Phase 2 (Approx.)

Fig-

Commuter Line (Larger int indicate transfer (SATUTE CITY)

station) ---LRT Line 1

-- LRT Line 2 0 2.5 5 10 K11ometers

0 Designated TOD Area in the Detailed Spatial Plan

CDVarious Center of Activities

Figure 3.4 The existing and planned rail transit network in Jakarta Source.- Author with data from RDTR 2014, The Jakarta Planning Agency, Open Street Map

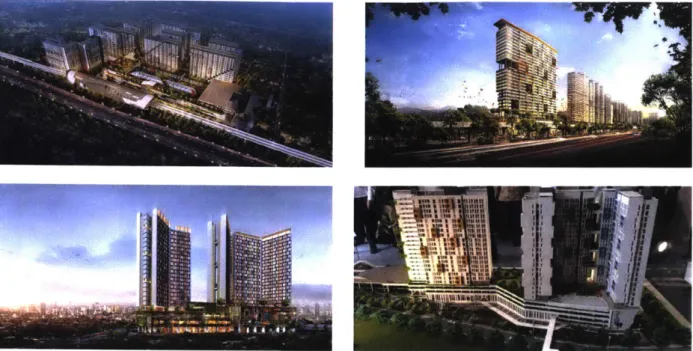

Figure 3.5 Illustration of current TOD projects in Jakarta

Source: LRTCITY; Liputan6.com

3.2 The Emergence of Transit Oriented Development

Transit oriented development is currently one of the forefront planning initiatives for the government, a strong development branding for developers, and an emerging lifestyle for the general public. The next sub-chapter will discuss how the TOD concept is incorporated into the regulatory system. Equally important is to observe the way in which developments have started to brand themselves as TOD in the past few years.

PT Adhi Karya, a public construction and property development enterprise, has been granted the right to construct the new LRT line along with supporting properties. The company developed the LRT City project, which is a set of superblock developments next to several LRT stations. Perumnas, the national housing development enterprise, has just started constructing two apartments around commuter stations on land owned by PT KAI (Kereta Api Indonesia), the National Train enterprise.

In addition, Perumnas seeks to develop more apartments around another three stations. Private developers have exploited TOD in their development branding as well. This trend has occured

because the general public started to see living in proximity to transit as a promising investment, if not a future lifestyle. Therefore, the market of TOD-branded development, particularly apartments, have been thriving.

Company Station Location Transit Mode

PT PP Tbk. * Juanda Station Commuter Train

- Manggarai Station

PT Waskita Karya Tbk. - Bogor Station Commuter Train

PT Adhi Karya TBk. - LRT City

- Bekasi

- Royal Sentul Park Bogor LRT

- Jati Cempaka

- West Bekasi

PT MRT Jakarta - Duku Atas (Sudirman) Station

- Fatmawati Station

MRT

- Cipete Raya Corridor

- Blok M - Sisingamangaraja Station

Table 3.1 Current TOD Projects

source: Nurcaya (2017)

Most of these developments have apartments for sale or office towers with proximity to a station, usually with retails stores as well as complementary amenities on the ground floor. While dense residential is indeed necessary for TOD, this trend does not display a holistic implementation of TOD. There has been more attention to the density aspect than to how these projects actually fit into and shape their contexts (In the Spotlight: Sibarani Sofian, 2018). Affordability is another attribute that many of these projects try to promote, especially for projects built by public enterprises. But this can only be proven effective after the properties reach the stabilized-occupancy stage and be re-evaluated, since people often buy these units as their second homes for future investment.

3.3 TOD Planning and Regulation

The Provincial Government of Jakarta created the Regional Spatial Plan for Jakarta 2030 (RTRW 2030), which is more elaborately developed in the 2014 Detailed Spatial Plan (RDTR 2014) document. The Detailed Spatial Plan contains, among other things, the city's zoning regulations. The zoning regulations are generally similar to those of US cities. The RDTR coordinates and regulates urban development at the province scale as well as at the parcel level. The provincial government also produces Urban Design Guidelines (UDGL) for various special areas that require specific guidelines, including TOD areas. Figure 2.6 shows the location of areas with UDGL, which also indicate the location of large urban projects in the city. Most of the areas with UDGL are located along the new MRT corridors, because UDGL is required for new TOD and density (FAR) increase proposals around MRT stations.

~-W-Legend

Areas with UDGL "

0 25 5 10 Miometers

Figure 3.5 Transit Stations and UDGL Locations

Source: The Jakarta Planning Agency (DCKTRP); and Open Street Map

However, UDGL documents are inherently advisory and not legally binding. The actual

implementation of the guidelines is controlled by the executive, the planning agency, during the permitting process. Only a few aspects of the recommendations, such as FAR, BCR, and block plans, are usually codified and signed by the Governor In general, UDGL is the direct planning instrument to control the form of development and is crucial for TOD. The following are several regulations that have addressed TOD:

TOD in the Ministerial Regulation

At the national level, the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning (2017) published a regulation about TOD guidelines. This regulation was released to anticipate the prevalent TOD initiatives in several major cities in Indonesia and to fill the gap in the spatial arrangement regulation about TOD and urban renewal. This regulation defines TOD as the area within 400 m - 800 m from the transit station. The major takeaway from this regulation is its TOD classification which discerns three general typologies:

- Urban TOD: characterized by the regional scale services and activities or the area that has been designated as an activity center

- Sub-urban TOD: characterized by the urban scale services and activities.

- Neighborhood TOD: characterized by the neighborhood scale services and activities.

These typologies are assigned with different urban characteristics which are represented by gradients of density, development intensity, open space requirements, parking requirements, and mixed-use proportions. Indeed, this regulation provides very comprehensive guidance on TOD, although its efficacy is questionable because it is a national level regulation; the regulation specifies various quantitative urban design guidelines that may or may not be appropriate for different contexts or different cities.

TOD in the Jakarta 2030 Regional Spatial Plan (RTRW 2030)

The Jakarta 2030 Regional Spatial Plan (Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta, 2012) is a provincial level plan which contains a development vision for the region and prescribes high-level guidance and ordinances. TOD in this document is characterized by three main attributes which are a mixture of residential and commercial uses, high accessibility from mass public transit, and compact and dense development. The document also mentions several TOD principles, whereby development should:

- Adopt regional or urban scale planning approaches with an emphasis on transit integration;

- Promote diverse land uses and activities;

- Encourage development in the area around transit in the form of infill development, revitalization, or redevelopment;

- Prioritize pedestrian oriented development; and

- Focus on the quality of public space and preserve green open spaces.

Most, if not all, of the important TOD principles have been mentioned in this document. This document also indicates several areas that should be developed as TOD, but without further elaboration of any typologies. This TOD designation is mainly based on the areas in the existing and planned transit network that are considered significant. The details on specific developments are to be elaborated in subsequent planning documents and regulation. TOD in the 2014 Detailed Spatial Plan Document (RDTR 2014)

The Jakarta 2014 Detailed Spatial Plan (Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta, 2014) is derived from the RTRW 2030 document. This document specifically mentions several station and terminal areas to be developed as TOD. They consist of the following areas:

- Harmoni District - Senen* - Grogol* - Blok M - Kebayoran Lama* - Dukuh Atas/Sudirman* - Manggarai*

- Pulo Gebang Terminal

- Jatinegara*

(*) indicates area with Commuter Line station.

These designated TOD areas are derived from the RTRW 2030. There are six designated areas that involve the Commuter Line stations. Furthermore, The most important feature of RDTR

2014 is the zoning regulation. It provides all the necessary guidance relevant for development such as land use, building coverage ratio (BCR), floor area ratio (FAR), green area ratio (GAR), building height, and setback.

Governor Regulation about TOD Management

One crucial progress step for TOD in Jakarta was the appointment of PT MRT Jakarta, the operator of the MRT Line, as the managing entities for TOD area around MRT stations

(Provincial Government of DKI Jakarta, 2017). This was promulgated by a Governor Regulation in 2017, which designated PT MRT the authority to engage with involved stakeholders and to coordinate developments. With this designation, PT MRT Jakarta as a state-owned enterprise could establish a business-to-business relationship with property owners and developers, and thus could ease the process for forming Public Private Partnership (PPP). This is particularly

crucial for financing strategies because the government is usually less nimble in this matter and often restricted by bureaucratic processes.

4. STATION CATEGORIZATION

In this chapter, this thesis explores a framework to initiate TOD planning with a quantified process that can characterize stations differently The Three Value (3V) Framework by Salat and Olivier (2017) provide a comprehensive analysis to distinguish stations based on node value, place value, and market value. It is a methodology for identifying economic opportunities in areas around mass transit stations and optimizing them through the interplay between the three values. A significant station with multimodal connectivity increases access for people and thus encourages the agglomeration of activities. Conversely, a vibrant urban area with robust activities encourages the influx of people and hence increases the significance of a station. Market forces trigger development and value good places, while a well-designed place eventually attracts higher market value. Analyzing the three values of each stations equips policy and decision-makers to better understand the relationship between the economic vision for the city, its land use, its mass transit network, and its stations' urban qualities and market vibrancy (Salat and Olivier, 2017).

4.1 Node Value

Node value recognizes the significance of a station based on its location within the transit network as well as its connection to other stations and transit modes. Ideally, TOD decision making should begin from an understanding of the node value of each station in order to effectively allocate and concentrate development that capitalizes on the transit network itself In cities with established transit networks like Paris, London, and Tokyo, studies reveal that the concentration of people and economic activities are highly influenced by their transit network. From this perspective alone, development should ideally be concentrated around stations with high node value to ensure maximum integration between connectivity and destinations - which together form accessibility

The commuter line in Jakarta consists of six lines that expand to nine municipalities and four regencies. Although this thesis focuses only on stations within the Jakarta Province, the centrality analysis includes the whole Commuter Line network and all the active stations based on the current operational map (see figure 4.1). Each of the following sub-indexes are normalized into a 0-1 scale (using Min-Max Normalization) and later compounded into one Node Value.