Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la

première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site

LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

Internal Report (National Research Council of Canada. Institute for Research in Construction), 1999-11-01

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

NRC Publications Archive Record / Notice des Archives des publications du CNRC :

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=487733a4-9f0b-40ea-b18c-2225e1615ef3 https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=487733a4-9f0b-40ea-b18c-2225e1615ef3

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous.

https://doi.org/10.4224/20331370

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Home Fire Safety Class for Working Adults

Ser I

/

TH1

I*I

Council Canada National Research Conseil national de recherches Canada1

R4271

/

no. 8 0 3 lnst~tute for lnstitut deResearch in

1

c.2 I Construction recherche en constructionI

IRCI

Home Fire Safety Class for

Working Adults

Guylene Proulx, Rita F. Fahy Judy Comoletti,

Meri-K Appy and Ed Kirtley

Internal Report

803

Home Fire Safety Class for Working Adults

by

Guylene Proulx, Ph. D.

National Research Council Canada

Ottawa, ON

Rita F. Fahy, M.

Sc.,

Judy Comoletti and,

Meri-K Appy

National Fire Protection Association

Quincy, MA

Ed Kirtley

Guymon Fire Department

Guymon, OK

* This study was conducted when NFPA's National Fire Alarm Code (NFPA 72) referred to the battery-operated device that warns of smoke in the home as a "smoke detector". However, since the study was conducted, the National Fire Alarm Code Technical Committee changed the term to "smoke alarm". The term "smoke alarm" refers to single- and multiple-station units that contain a sensor, processing electronics, and a sounding device. Generally, the term "smoke detector" refers to a device that is powered by a control unit. A 'smoke detecor" has a sensing device and some

processing electronics, but no sounding device, and must have separate sirens or horns. Most homes have "smoke alarms" rather that "smoke detectors".

List of Figures

...

Figure 1 : Median Scores on Test 2 11

Figure 2: Test 3 Subscale

...

13List of Tables Table 1: Summary of the Experimental Design

...

7Table 2: Table 3: Table 4: Table 5: Table 6: Table 7: Table 8: Table 9: Table 10: Table 1 1 : Table 12: Table 13: Table 14: Table 15: Table 16: Table 17: Table 18: Table 19: Table 20: Table 21 : Table 22: Table 23: Table 24: Gender Distribution for the Five Groups

...

7Age Distribution for the Five Groups

...

7Median Scores on Tests 1. 2 and 3

...

9Scores in Test 1

...

10Scores in Test 2

...

10Scores in Test 3

...

11...

Median Scores for the Main Effects of Participation and Video 12...

Scores in Test 3 on Behaviour and Attitude Change Questions 12...

"What is the most common cause of death from a fire?" 14...

"What should you do to prepare your home and family?" 14 Frequency by Age at Question 2...

14...

"You live on 27th floor...

the fire alarm goes off you discover...

thick black smoke in the hallway.

What should you do?" 15 Frequency by Age at Question 3...

15"It is

2:00

a.m. you are asleep on the second floor...

your two children are asleep down the hall.

The smoke detector sounds . What should you do?"...

15Frequency by Age at Question 4

...

16"You are most likely to experience a fire in which one of the following situations?"

...

16"Have you ever experienced a fire?"

...

16Frequency by Age at Question 6

...

16Scores in Test 2. Question 2

...

17Scores in Test 2. Question 3

...

18Scores in Test 2. Question 4

...

18~urnber of Respondents Who Said They Would Attempt to Escape in Test 1 and Test 2

...

18Home Fire Safety Class for Working Adults

Guylene Proulx. Rita F

.

Fahy. Judy Comoletti.Meri-K Appy and Ed Kirtley

Table of Contents Acknowledgement

...

iv Executive Summary...

v 1.

0 Introduction...

1. .

2.0 Study Objectives...

2 3.0 Research Strategy...

2 3.1 Instructor...

2 3.2 Participants...

2...

3.3 Assessment Tool 3...

3.4 Fire Safety Class 3...

3.5 Videos Used 5...

3.6 Teaching Approach 5 4.0 Study Methodology...

6 5.0 Results...

7...

5.1 Study Participants 7 5.2 Meeting with the Control Group...

85.3 Data Analysis

...

8...

5.4 Scores in Tests 1, 2 and 3 9 5.4.1 Scores in Test 1...

95.4.2 Scores in Test 2

...

105.4.3 Scores in Test 3

...

11...

5.5 Item Analysis of Test 1 13 5.6 Item Analysis of Test 2...

17...

5.7 Item Analysis of Test 3 19 5.7.1 Participants' Attitude and Behaviour Toward Home Fire Safety...

205.7.2 Information Retained from the Fire Safety Class

...

215.7.3 Smoke Detectors

...

245.7.4 Home Escape Plan

...

285.7.5 Behaviour and Attitude Change

...

296.0 Discussion and Conclusion

...

30Appendices

...

A Class Content vii...

...

B Tests 1. 2 and 3 vlli C Coding Manual...

ix...

Table 25: Table 26: Table 27: Table 28: Table 29: Table 30: Table 31: Table 32: Table 33: Table 34: Table 35: Table 36: Table 37: Table 38: Table 39: Table 40: Table 41 : Table 42: Table 43: Table 44: Table 45: Table 46: Table 47: Table 48: Table 49: Table 50:

Scores in Test 2. Question 6

...

19"Do you have someone at home who smokes?"

...

20"Where do you keep matches and lighters?"

...

20"Do you sometimes leave the kitchen when you are cooking?"

...

21"Do you deep fry?"

...

21"Do you use a portable heater?"

...

21"What do you remember from the Fire Safety Class"

...

22"Was there anything new that you learned"

...

22"Did you receive any brochures?"

...

22"Did you read them?

...

23...

"What were these brochures about?" 23...

"What did you do with these brochures?" 23...

"Do you remember seeing a video?" 24...

"What was this video about?" 24 "Do you remember any information about smoke detectors in the home?"...

25"What kind of home do you live in?"

...

25"How many smoke detectors do you have in your home?"

...

26...

"Where are your smoke detectors located?" 26...

"Your smoke detector. does it work?" 26 "When was the last time you tested your smoke detector?"...

27'When was the last time that you changed the battery?"

...

27...

"Did you test or change the battery because of the class?" 27 "Who forms your family?"...

28"What about a Home Escape Plan?"

...

28"Have you changed your behaviour toward fire safeiy

.

...

since the class?" 29

...

Acknowledgment

The participation of many people was critical to the successful completion of this research project. We are particularly grateful to the different fire safety officers who found locations or welcomed us into their workplace to conduct the Fire Safety Class; without them this project would not have been possible.

Our special thanks go to Mr. John Chicken of the Maine Employers' Mutual Insurance Co., Portland, Maine; Mr. Jim Thompson at Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Ottawa, Ontario; Mrs. JoAnn Campbell at National Marine, New Orleans, Mississippi; Mrs. Vicki Wade of the Palm Beach Gardens Fire Department, Palm Beach Gardens, Florida; and Mr. Bruno Roy at the National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. These dedicated people found participants and facilitated the preparation and the conduction of the Fire Safety Classes. Their involvement was essential to successfully complete this research project.

We would also like to extend our thanks to Dr. Russ Thomas, Director of the Fire Risk Management Program at NRC who advised on the statistical analysis for the report.

Home Fire Safety Class for Working Adults

Guylene Proulx, Rita F. Fahy, Judy Comoletti, Meri-K Appy and Ed Kirtley

Executive Summary

An experimental study was developed to assess the change in attitude and behaviour of working adults after receiving a Home Fire Safety Class. Four groups of working aduits each received a different Class. Each group received the same basic information on Home Escape Planning, but the presentations varied on two aspects; a) two different videos were shown, and b) two teaching approaches were used. A fifth group, the Control Group, received no special information on Home Escape Planning.

The two videos shown were selected by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). The first video, called "News Clip", reports on an actual fire in a residential building where a child died. This video takes the form of a news clip; it is a collection of scenes from the real event. The second video that was used is called "Fire Power". This video was put together in 1986 by NFPA. It uses a theoretical format based on facts. For the experimental study two groups saw the first video and the other two saw the second one. The groups were randomly selected to see either of the two videos.

Two teaching approaches were used: non-participatory and participatory. In the non-palticipatory approach, the class was presented in a formal manner with limited participation by the audience. By comparison, in the participatory approach, the

instructor made a constant effort to obtain the maximum involvement of the participants. The instructor encouraged participants to give an account of their own experiences and used these real life experiences later to illustrate the different pieces of information to be learned. The experimental design was Group 1 : News Clip, Non-participatory; Group 2: News Clip, Participatory; Group 3: Fire Power, Non-participatory; Group 4: Fire Power, Participatory; and Group 5: Control Group.

Most groups received 3 assessment tests. Test 1 was a questionnaire

administered to each participant at the beginning of the Class to assess their knowledge regarding Home Escape Planning prior to the Class. Test 2 entitled "What have you learned?" was administered to the 4 tested groups immediately after the Fire Safety Class, to assess the information learned by the participants during the class. The Control Group did not complete Test 2. Finally, 2 to 3 months after the Fire Safety Class, each participant was met with individually to answer the questions of Test 3 entitled "Post-Test Questionnaire". The participants were previously unaware that they would be inte~iewed to do a follow-up on the Class.

Based on Test 1, it was assessed that the 4 tested groups and the Control Group were comparable in their general knowledge concerning home fire safety before the Fire Safety Class. This was very important for the following analyses of the study.

The tests show that most participants agreed on the importance of having a Home Escape Plan and the majority of participants confirmed having one. Interestingly, usually they had not discussed their Home Escape Plan with their families, drawn it on paper or practiced it. So it appears that, for most participants, having a Home Escape Plan simply means that the person has thought about how to escape from their house and finds this to be sufficient preparation.

A total split of opinion was observed regarding the best behaviour in a scenario of a highrise fire with thick smoke regarding the means of egress. Even though

participants know that people die from smoke inhalation in fires, they don't seem to understand that a very small quantity of smoke could be dangerous or that a short exposure could be lethal. Protect-in-place activities are less likely to be mentioned by older participants who prefer to evacuate. Even after a complete explanation of the protect-in-place option, there were people who still said they would rather evacuate through smoke. The younger participants were more likely to identify the protect-in- place option as the best response for the scenario proposed.

The results in Test 3 show that the participatory teaching approach improved the subjects' scores over those in both the control and non-participatory groups.

Furthermore, the Fire Power Video improved scores regardless of the teaching approach taken but, with the participatory approach, the scores were again significantly better. This finding demonstrates the importance of the video that was used during the Fire Safety Class.

The results of this study show that teaching home fire safety in the work

environment is an excellent strategy to reach working adults. Because of the Class, out of the 63 participants who answered Test 3, 18 (29%) tested their smoke detector; 5 (8%) bought a new smoke detector; 4 families (6%) discussed their Home Escape Plan; 7 others (1 1%) put it down on paper; and another 3 families (5%) practiced their Home Escape Plan. This study shows that, aside from the Control Group, 83% of the participants who took part in a Fire Safety Class felt more aware of home fire safety or had changed something specific about their home fire safety. These results

demonstrate the importance of improving the curriculum of the home Fire Safety Class and of pursuing the education and training of working adults.

The National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and NFPA, collaborated in this research. For NFPA, it is essential to better know what information to provide and how it should be presented to achieve its objective of making people more aware and

knowledaeable about home fire safetv. It is imoortant to make sure that all the effort. time and';noney invested in education and training achieve the expected goals. Identifying the appropriate information that people can handle and the best wav to provide this information is essential in developing better fire safety educationai programs. For NRC, it is important to be able to measure the impact of fire safety education so that this variable can be included in occupant response models. Fire safety education has been identified as a major factor in predicting occupant response time and actions during fire evacuations. The results of this study will help to establish a response factor for the Occupant Response Sub-model of FiRECAMm which, in turn, will be linked to occupancies where educational programs are in place.

Home Fire

Safety Class for Working Adults

Guylene Proulx, Rita F. Fahy, Judy Cornoletti, Meri-K Appy and Ed Kirtley

1.0 Introduction

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), in collaboration with different groups, develops and distributes educational and training material on fire safety for the North American public. For working adults, it is not known

if

the fire safety educational material currently available is effective. The objective of this educational material is twofold: first, it is aimed at increasing people's knowledge about fire safety; secondly, i tis an attempt to change attitudes and make people apply appropriate fire safety

measures. It is expected that,

if

the educational effort is successful, working adults will apply these fire safety measures in different environments, especially in their homes.To ensure that the fire safetv messaae ~rovided in the educational material achieves its goal of educating wo;king adits: it is essential to know what information should be provided. The form in which the information is presented is another critical issue. some advocate presenting realistic videos to shock, or even scare people in an attempt to make them react and apply fire safety measures. Others are of the opinion that explaining the rationale behind important fire safety notions will make people more aware of the danger and take proper actions.

The teaching approach used to convey the fire safety information to working adults is another important issue. The highly participatory approach of the NFPA's Learn Not to Burn63 program has been very successful with children, compared to a more theoretical format. It is not known if a similar participatory approach with working adults would improve learning and eventual changes in behaviour and attitude toward fire safety. It is essential for NFPA to better know what information to provide and how it should be presented to achieve its objective of making people more aware and

knowledgeable about fire safety. It is important to make sure that all the effort, time and money invested in education and training achieve the goals expected. Identifying the appropriate information that people can handle and the best way to provide this information is essential in developing better fire safety educational programs.

For the National Research Council of Canada (NRC), it is important to be able to measure the impact of fire safety education so that this variable can be included in the Occupant Response sub-model of FiRECAMTM I. The importance of fire safety

'

Yung, D.T.; Had~isophocleous, G.V.; Proulx, G., 1999, "A Description of theProbabilistic and Deterministic Modelling Used in FiRECAM", International Journal of Enaineerina Performance Based Fire Codes, Vol. 1, No. 1, Hong Kong, China, pp. 18- 26.

education has been identified as a major factor in predicting occupant response time and actions during fire evacuations. In assessing the impact of educational material, this study will provide more accurate data related to the extent of the impact of education on people's reactions. The results will help to establish a response factor for the Occupant Response sub-model of FiRECAMTM, which in turn will be linked to occupancies where educational programs are in place.

2.0 Study Objectives

This study has three main objectives:

1. Assess different methods for providing fire safety information that will be understood and retained by adults.

2. Evaluate the teaching approach used to deliver fire safety educational messages aimed at working adults.

3. Measure the behaviour and attitude change regarding fire safety after receiving the educational messages.

The following two hypotheses govern this study: First, "Fire Safety Education can change behaviour and attitude towards fire safety." Second, "The type of information provided and the ways by which fire safety material is presented will have an impact on the person's behaviour and attitude towards fire safety".

3.0 Research Strategy

To meet the research objectives, it was decided to conduct an experimental study. Four Fire Safety Classes were planned with groups of working adults. Each group received the same basic information on Home Escape Planning, but the presentations varied on two aspects; a) two different videos were shown, and b) two teaching

approaches were used. A fifth group of participants, receiving no special information on Home Escape Planning, served as a Control Group. This Control Group is essential to ensure that any difference between the tested groups can be attributed to the Fire Safety Class and not to the passage of time or any extraneous events.

3.1 instructor

To minimize the impact of the instructor on the participants' learning experience, the same person taught all of the Fire Safety Classes. The instructor was a male, former training officer currently employed as a Fire Chief who has been involved in fire safety education for more than 10 years. The instructor was a member of the research team. He participated in the development of the class curriculum and the participants'

assessment tools.

3.2 Participants

The five groups tested were chosen to represent typical office workers in North America. Sites were selected in a variety of locations. NFPA and NRC combined their efforts to find sites where people were prepared to take part in this study. From our networks, different persons interested in fire safety education were contacted to identify office environments where the study could be conducted. It was essential to find, on location, a person interested in fire safety education, who was prepared to facilitate the organization and selection of participants to attend the class. Selection of the

participants was left to the contact person on location, who had the responsibility to find 15 to 20 people among their staff prepared to spend 1 to 1% h on this class on Home Escape Planning. The participants had to be a mix of male and female working adults between the ages of 20 and 60 years. The Fire Safety Class was carried out in the workplace.

3.3 Assessment Tool

Each of the experimental groups received 3 assessment tests. Test 1 was a questionnaire, which was administered to each participant at the beginning of the class to assess their knowledge regarding Home Escape Planning prior to the class. Test 1,

entitled "Fire Safety Questionnaire", was used in each of the exoerimental arouos and with the Control ~ i o u p (see ~ppendix 6). This initial test would provide a &od'portrait

of what was known by the participants of each group before the Fire Safety Class. It also allowed the research team to ascertain if the groups were at a similar-level of awareness at the start of the study.

A second test was administered to the 4 tested arouos immediatelv after the Fire Safety Class, to assess the information learned by thepakcipants during the class. Test 2 was entitled What have you learned?" (See Appendix

. .

B). The Control Group did not complete Test 2.Finally, 2 to 3 months after the Fire Safety Class, each participant was met with individually to answer the questions of Test 3, entitled "Post-Test Questionnaire" (see Appendix B). The participants were previously unaware that they would be interviewed to do a follow-up on the class. This last test was conducted with participants of the 4 tested groups and the participants of the Control Group. The interviewer was the same person for all the interviews. The individual interviews lasted 10 to 15 min and were tape-recorded. After each interview, Test 3 was filled out by the interviewer based upon the responses of the interviewee.

3.4 Fire Safety Class

The Fire Safety Class was held in the work environment at each location where the participants gathered in a meeting room to take part in the class. Classes were

conducted during normal working hours and lasted for approximately 1 h for the groups receiving a non-participatory approach and 1 % h for groups receiving the participatory approach.

There was a core of information that was given to all 4 groups (see Appendix A). The class started with a few overheads reviewing the number of residential fires that the fire deoartments have to attend and the number of deaths and iniuries. The instructor stressed the importance of smoke detectors. This introduction td the class was completed with the presentation of the Learning Objectives for the class which were:

To know about

...

Risks from smoke inhalation Proper exiting response

Proper locations of smoke detectors Response to a fire in the home How to develop a home escape plan

The importance of

...

Practice, Practice, PracticeThen, one of the 2 videos was presented after which participants were welcomed to ask questions. The class then continued on the topic of smoke detectors. Six main elements were presented:

1. Smoke detectors provide an early warning. This extra time is essential for escape from a burning home or apartment.

2. Detectors are triggered by smoke particles. They are activated by a small quantity of smoke.

3. Smoke detectors should be placed on every level of a home. One should be outside the sleeping area. If an occupant sleeps with the bedroom door closed. there should be a smoke detector in the bedroom.

4. Smoke detectors should be tested at least monthly.

5. Smoke detectors should have the battery chanaed at least vearlv. Smoke

-

detectors should be cleaned regularly.6. Smoke detectors should be replaced after 10 years.

During the section on smoke detectors, the instructor used a battery-operated smoke detector to show participants how to test, clean and change the battery. The smoke detector was then circulated around the class.

The following part of the class was on an escape plan. The instructor stressed the importance of having a home escape plan for the family that has been put down on paper, discussed and practiced by all family members. The rules to develop a Home Escape Plan were described in 6 steps:

1. Gather your family

2. Draw a floor plan of your house or apartment 3. Locate smoke detectors

4. Identify 2 ways out of each room

5. Choose a meeting place outside the building 6. Practice the plan twice a year

The instructor then explained the rules for escaping from a home that is on fire. Simple notions were reviewed, such as checking the door for heat, opening the door a crack to check

if

the corridor is clear, crawling if there is smoke, assisting young children, closing doors on your way out and going to a neighbour to call 91 1 or the emergency number. Different alternatives for highrise apartments, such as the actions to "protect-in- place" by sealing doors and vents before going to a balcony or waving a sheet from a window were also discussed. The participants were then given 5-10 min to draw their own homes and to start planning their home escape plan.For the presentation, the material available in the room consisted of a flip chart, overhead projector, television and VCR.

3.5 Videos Used

Two videos were selected by NFPA to be presented to the 4 tested groups. Two groups saw one video and the other two saw the second video. The groups were randomly selected to see either of the videos.

The first video, called "News Clip", reports on an actual fire in a residential building where one child died. This video takes the form of a news c l i ~ : it is a collection of

scenes of the real event. At the beginning, the video shows

a

ko-storey wood house with smoke pouring out from the windows. A fire truck arrives on location. Firefighters enter the building and one firefighter comes out running carrying a small boy in his arms. He brings the child to an ambulance. As the ambulance is taking off, another firefighter shouts from the building "hold on, there is one more, one more!". The ambulance halts abruptly, the back doors swing open and a firefighter comes carrying a second child. Then another firefighter comes out from the house with a third child. The voice of a woman iournalist savs "this fire killed one of the bovs while the 2 brothers and the woman iemain in the hospital". A firefighter is interviewed, he mentions that the fire probably started with smoking material. The downstairs neighbour is interviewed, he says that he was watchingn/

when he suddenly noticed smoke coming from the back door. He didn't have time to get anything. He just ran outside. The whole News Clip segment lasted only 2 min.The second video that was used is called "Fire Power". This video was put together by the NFPA in 1986. It uses a theoretical format based on facts. The host, Jack Harper, explains that the single-family house shown will be set on fire. The camera follows the host throughout the house, which is fully furnished but is not occupied. The fire is set in a waste paper basket in the living room close to a couch. As the house is filmed burning, the host gives comments on the timing and the extent of the damage. The fire is filmed in real time and lasts for 9 minutes. Eventually firefighters arrive and extinguish the fire. The host visits the remains of the house commenting on the

damages. For the purpose of the study, the original "Fire Power" video was shortened at the beginning and at the end for a total presentation time of 12% min.

3.6 Teaching Approach

Two teaching approaches were used during the Fire Safety Class. Two of the groups were non-participatory groups while the others two were participatory groups. In the non-participatory approach, the class is given in a formal manner with limited

participation from the audience. The instructor stands at the front of the group to deliver the information. The participants are welcome to ask questions of the instructor, but that is the full extent of their participation.

By comparison, in the participatory approach, the instructor makes a constant effort to obtain the maximum involvement of the participants. The instructor encourages participants to report their own experiences. Some of these real life experiences are later used to illustrate the different pieces of information to be learned. At the end of the class, the participants are asked tostand up and mimic their evacuation movement from a house drawn on the floor. Using a real smoke detector, the instructor activates the

alarm and a few participants have to show the proper behaviour to follow while the others watch, encourage and comment.

4.0 Study Methodology

All groups met in their work environment during working hours. A video camera was installed on a tripod at the back of the class to record the entire session for later use. The arriving participants sat at tables and the instructor introduced himself and his assistant. It was mentioned to the participants that they were part of a research project on home fire safety being conducted by NFPA and NRC, which explained why they were asked to fill out questionnaires. The Fire Safety Class was carried out in four steps:

Step 1 Initial Evaluation. Test 1, the first questionnaire, entitled "Fire Safety Questionnaire", was distributed to participants to assess each participant's fire safety knowledge prior to the Fire Safety Class. The same procedure was used for all 5 groups. For further comparison, it was important to assess the participant's level of knowledge at the beginning of the study. Step 2 Fire Safety

Class.

Each of the four tested groups participated in adifferent Home Fire Safety Class, which provided them with basically the same content of informatbn. One groupsaw the News Clip video and received a non-participatory teaching approach. Another group saw the News Clip video with a participatory teaching approach. The two last groups saw the Fire Power video, one with the non-participatory teaching approach and the other one with the participatory approach. Finally, the Control Group did not get any specific Fire Safety Class; the participants were asked if they had any questions which the instructor answered. At the end of the class all groups, including the Control Group, received the same three brochures and a sticker (see Appendix C).

Step 3 Fire Safety Tips Learned. At the end of the Fire Safety Class, the four

tested groups completed Test 2 entitled, 'What have you learned?", to evaluate what was learned during the class. The Control Group did not fill out Test 2.

Step 4 Behaviour and Attitude Change. Two to three months after the class,

each participant of the 5 groups were inte~iewed individually. Questions from Test 3 entitled, "Post-test Questionnaire", were used to assess the information retained by each participant, his or her understanding of this information and their change of behaviour and attitude toward fire safety since the class.

The study methodology was designed to assess the knowledge of each group at first in an attempt to establish if the groups were comparable. Then a 2 X 2 design was used to measure the impact of the 2 independent variables, the teaching approach and the video used. Consequently, the experimental design had 4 conditions received by 4 different groups of participants. The fifth group, the Control Group, was used to assess if the fact of receiving Test 1 with no specific Fire Safety Class, with a delay of 2-3 months has an effect on Test 3, the "Behaviour and Attitude Change". The experimental design is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of the Experimental Design

5.0 Results

The study was designed to compare the results of each group from the 3 Tests to measure the effect of the videos and the teaching approach. The research also

provided frequency distributions for the groups for some specific questions, which can be useful in assessing what working adults know and do about home fire safety.

5.1 Study Participants

It was more difficult than first expected to find sites and participants for this study. It is always difficult to take people away from their jobs for over 1 h to conduct a Fire Safety Class. At each site, 20 participants were always expected but last minute commitments, absences and sick leave lowered the participation. Consequently, 1 1 to 17 participants met at each site for a total of 73 participants, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Gender Distribution for the Five Groups

A good gender distribution was obtained, as well as a good representation of different ages from 24 to 63 years old. Table 3 shows the age distribution. Most participants were or had been fire wardens in their workplace.

5.2 Meeting with the Control Group

The Control Group did not receive a formal Fire Safety Class along the lines of that presented to the other four test groups. The participants were, however, met by the instructor in a large room designed for presentations. As a first step, the Control Group followed the same procedure as the other groups and filled out Test 1. Once Test 1 was completed, the instructor told the group that he was available to answer any questions related to Home Escape Planning or Fire Safety in general. This approach can be compared to the set up sometimes used in shopping centres or public assembly buildings where firefighters are on location and the public can come to them to ask questions.

The questions asked by the audience of the instructor are presented below. They are presented in a chronological order. Many of the questions sprang out from the answer that was given by the instructor to the previous question.

Is it important to have a CO detector?

What can be done for nuisance alarms from smoke detectors close to the kitchen area?

Are fire extinguishers useful?

Are hard wired or battery operated smoke detectors better?

Is it enough to have one smoke detector in the hallway between the bedrooms?

Is it safer to sleep with the bedroom door closed?

How many escape ladders are needed in a 2-storey house? What should we do in a highrise fire?

Where should we locate the fire extinguisher?

Is it better to have a fire extinguisher or a fire blanket? Is it important to have a fire extinguisher in the car? What are the symbols A-BC on a fire extinguisher?

Should we unplug appliances such as microwave, W, when leaving for the day or the weekend?

The question and answer period lasted for 32 min. Once there were no more questions, the instructor thanked the audience for their time and distributed the brochures as they left. Test 2 was not administered to the participants of the Control Group.

5.3 Data Analysis

The data analysis of this study is performed in two ways. In the first approach, the scores from the 3 Tests are compared using nonparametric tests, as the scores just represent the frequency of correct responses to the questions. Scores in Test 1 are compared among all groups to assess if the initial knowledge of the participants are similar, which will allow for a comparison of the impact of the Fire Safety Class on their performance on the subsequent tests. Then the scores are compared for the tested groups in Test 2, which assess the information learned immediately after receiving the Fire Safety Class. Finally, data collected with Test 3 are scored to measure the

information retained, and assess changes in behaviour and attitude, 2 months after the Fire Safety Class.

In the second approach, the results of a frequency analysis of the responses to the 3 Tests are provided. This type of analysis provides a good portrait of the fire safety knowledge of the participants that can be compared to the population in general. 5.4 Scores in Tests 1 , 2 and 3

A few questions in the 3 Tests offered a choice of responses. Most questions, however, were open-ended, so participants were given a few lines to elaborate an answer. Specific elements that were expected to be found in the answer were assigned one point each. For example in Test 1, Question 2, the participants were asked: "What should you do to prepare your home and family to respond correctly if a fire occurs in your homeythe question was open-ended so respondents could develop their personal answer. In scoring this question the following elements in the answer were given one point each; 1) have a smoke detector, 2) test smoke detector, 3) have a home escape plan, 4) practice home escape plan. A total score of 4 points could be obtained for this question. The coding manual in Appendix C, lists the expected correct answers for the 3 Tests.

The number of participants in each group who answered each of the 3 Tests varied from 10 to 17. The median score for each group on the 3 Tests are presented in Table 4. A total of 15 points could be obtained in Test I , 25 points in Test 2 and

43 points in Test 3.

Table 4: Median Scores on Tests 1 , 2 and 3

5.4.1 Scores in Test 1

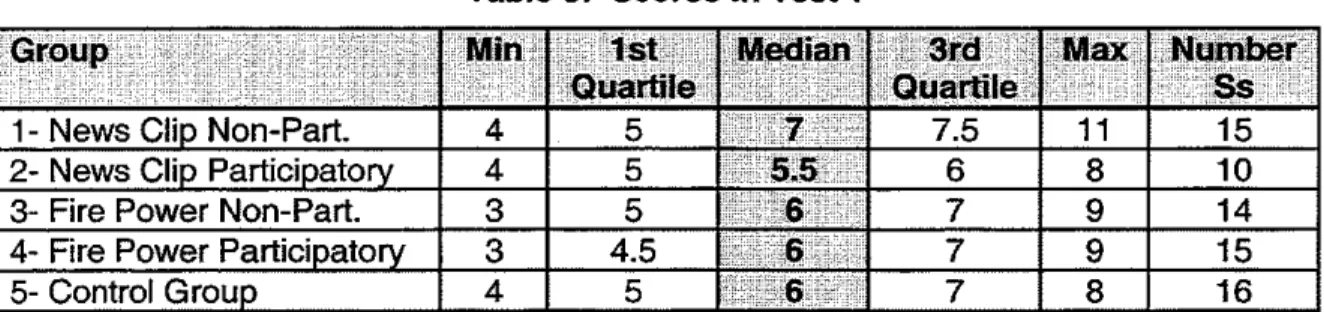

Test 1, which was administered to the participants before the Fire Safety Class, is used to assess if participants of the five groups are comparable at the start of the study. It is essential for the study that participants from each group obtain similar scores in Test 1 to be able to compare these groups after the Fire Safety Class. The maximum number of points a participant could receive in Test 1 was 15. Nobody obtained a perfect score. Table 5 presents the median scores for each group on Test 1.

Table 5: Scores in Test 1

An analysis of this data showed no significant difference between the scores in Test 1 for the 5 groups (Kruskal-Wallis, H = 2.456, df =4, n.s.). This result shows that there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of their knowledge of fire safety prior to the Fire Safety Class. This indicates that later differences can be

attributed to the impact of the Fire Safety Class and its content. Three participants did not complete Test 1, since they arrived late for the presentation: one was in Group 1 and two were in Group 4.

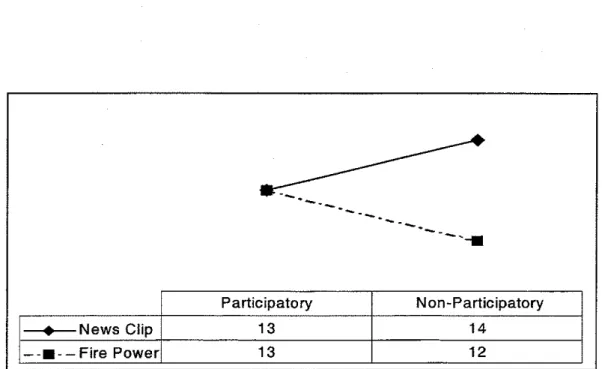

5.4.2 Scores in Test 2

Test 2 was administered immediately after the Fire Safety Class. Respondents could obtain a maximum of 25 points on this test. Median scores for each group are presented in Table 6. An analysis of this data indicated that there was a significant difference (Mann-Whitney U = 158.5, df =

I,

p < 0.02) between the type of video used in the class in the non-participatory condition (see Figure 1). In this case, the News Clip video resulted in a significantly higher score on Test 2.Figure 1: Median Scores on Test 2

/

---_

-.---_

-

-

-

-

-

'1 5.4.3 Scores i n Test 3 +News Cllp - - m --

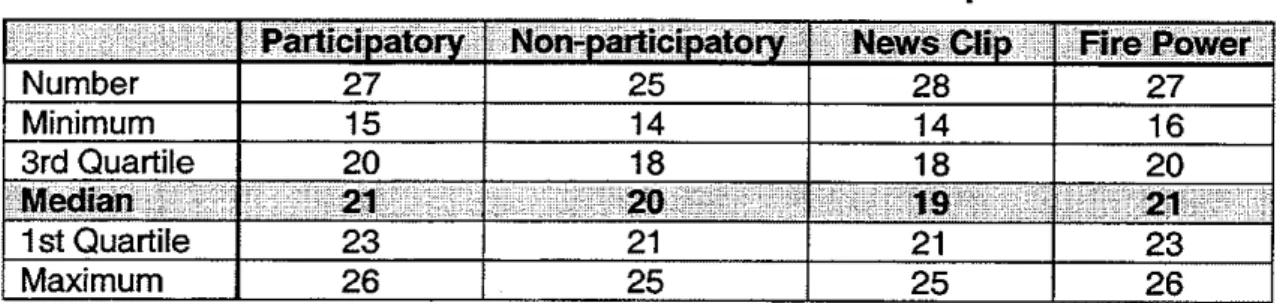

Fire PowerTest 3 was based on an interview conducted face to face with each participant in the work environment 2 to 3 months after the Fire Safety Class. This was carried out to investigate the retention and use of the information presented in the class. A few questions in Test 3 were designed to better understand the participants and their safety habits in their home. Other questions were intended to be indicators of how much information had been retained, and used, from the Fire Safety Class. Finally, some questions were more specific to attitude and behaviour changes, which were influenced by the Fire Safety Class. Participants could obtain a maximum of 43 points on this Test. The results of Test 3 are presented in Table 7.

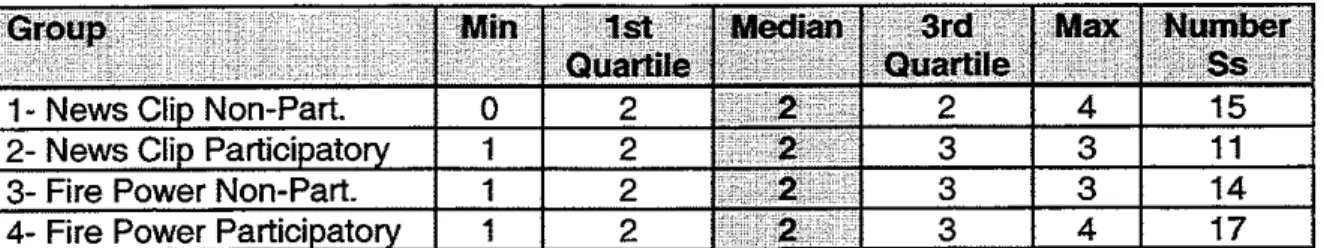

Table 7: Scores i n Test 3 Participatory

13 13

An analysis of the data identified a significant difference among the conditions (Kruskal-Wallis H = 32.597, df= 4, p < 0.005). Simple main effects showed that there

Non-Participatory

14 12

has a significant difference (~ann-whitney

u

= 183.5,&=I,

p < 0.005) in the scores between the two videos and a significant difference between the groups thatexperienced a participatory vs. a non-participatory class (U = 466, df =l

,

p < 0.02) (see Table 8). Post-hoc tests were then conducted and indicated a number of significant differences between specific conditions (Fire Power Participatory vs. Fire Power Non- participatory: U = 32.5, df = 1 p < 0.005; Fire Power Participatory vs. News ClipsParticipatory: U = 33.5, df = 1 , p < 0.01; Fire Power Participatory vs. News Clips Non- participatory: U = 36.5, df = 1, p < 0.005; Control vs. News Clip Participatory: U = 10,

df =

I,

p e 0.001 ; Control vs. Fire Power Participatory: U = 0, df= 1, p < 0.001 ; Controlvs. News Clip Non-participatory: U = 13.5,

df=

1, p e 0.001 ; Control vs. Fire Power Non- participatory: U = 5, df=I,

p e 0.001). These results indicate that all groups whoreceived the Fire Safety Class scored significantly higher than the Control Group. Also, Group 4 who saw the Fire Power video and who received the participatory teaching approach, scored significantly higher than ail the other groups.

Table 8: Median Scores for the Main Effects of Participation and Video

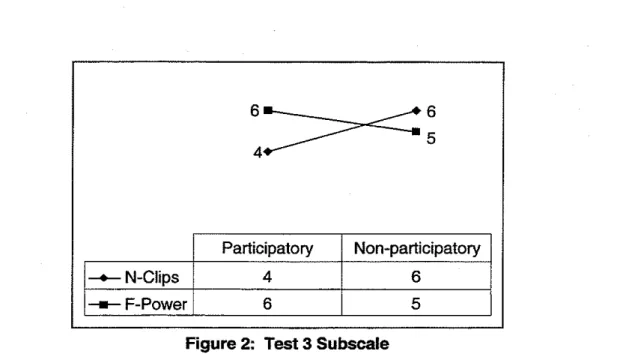

An analysis was conducted on a sub-set of questions (see Appendix C) specifically related to behavioural and attitude changes that were relevant to all five groups. This sub-set of questions was related to checking and changing the smoke detector battery, having a home escape plan, discussing the plan with family, putting it down on paper, practicing the plan and, finally, changed behaviour toward fire safety since the Fire Safety Class. Participants could receive a maximum

of

12 points on these questions. The results are presented in Table 9.Table 9: Scores in Test 3 on Behaviour and Attitude Change Questions

The analysis indicated a number of significant differences amona the exoerimental " - - ~ ~

conditions and-with the Control Group (~ire-power Participatory vs. Fire Power Non- participatory: U = 37.5,

df=

1 p < 0.05; Fire Power Participatow vs. News C l i ~ s Participatory: U = 38.5, df= 1, p c 0.02; Control vs. ~ e w s ~ l i ~ ~artici~atory:u

= 25.5, df = 1, p < 0.02; Control vs. Fire Power Participatory: U = 8.5, df = 1, p c 0.001; Control vs. News Clip Non-participatory: U = 13, df = I , p c 0.001; Control vs. Fire Power Non- participatory: U = 18, df= 1, p c 0.01).Figure 2: Test 3 Subscale

Although the overall results of Test 3 indicate that a significantly higher score was obtained by those who experienced the participatory approach, this was not consistently true when looking at the behaviour and attitude subscale. In terms of long-term

behaviour and attitude change, it would appear that this is determined both by the participatory approach and the video used in the class (see Figure 2). In the

participatory class, the Fire Power video results in a significantly greater retention than the News Clip video. In contrast, in the non-participatory class, the News Clip video results in the same level of behaviour and attitude change as that found with the Fire Power video in the participatory class.

The same is true in terms of the video used in the class with the Fire Power video showing a significantly higher score on the overall scale of Test 3 than the News Clip video (see Figure 2). Again, there was significant interaction between presentation type and video on the behaviour and attitude change subscale with the Fire Power video resulting in a significantly higher score when used in the participatory class than the News Clip video.

There is clear evidence that taking part in the classes did result in significantly higher scores on both the full scale score of Test 3 and on the behaviour and attitude change subscale.

5.5 Item Analysis

of

Test 1In a way to efficiently summarize responses in Test 1, frequencies have been calculated for each question. This approach gives a good overview of the participants' general knowledge about fire safety. Since no statistical differences were found among groups, all participants' responses can be analyzed together.

Test 1 had 6 questions. Question 1 was: "Many people die in fires every year. What is the most common cause of death from a fire?" Participants could choose only one of 4 options. Response distribution to this question is presented in Table 10. It is clear that everyone knew that smoke is the most common cause of fire deaths.

Table 10: "What is the most common cause of death from a fire?"

Question 2 asked: "What should you do to prepare your home and family to respond correctly if a fire occurs in your home?" This was an open-ended question where respondents could elaborate their views. Points were given for four major elements, as presented in Table 11. Respondents could provide more then one

element. Out of the 70 participants who completed Test 1, 74% mentioned that the best way to prepare your family for the eventuality of a fire is to have a home escape plan. Fifty percent said that they should practice the home escape plan, 40% indicated the need to have a smoke detector and only 9% said that they should test their smoke detector. A n s w Burns Heat Heart failure Smoke Total

Table 11 : "What should you do to prepare your home and family?"

If the frequency of answers is calculated for this question in relation to the age of the respondents, a slightly dierent picture appears as can be seen in Table 12. Across the 5 age groups, the most popular way to prepare your family for a fire is still to have a Home Escape Plan. Those in the 20-29 years age range are the ones who express the importance of practicing the Home Escape Plan. Interestingly, no one over the age of 40 mentioned the importance of testing their smoke detector.

Total 0 0 0 70 70 Male 0 0 0 31 31 ' .Ansuue:r' :,

. .

.,; .< , -~ ,.

,-

,;!; ,. # .;.: [ : ,~ -,,, :!:,., . 'Have a home escape plan Practice home escape plan Have a smoke detector Test smoke detector Total

Table 12: Frequency by Age at Question 2 Female 0 0 0 39 39

Table 13 presents the answer by gender to Question 3: "You live on the 27th floor of a highrise apartment building. The fire alarm is going off at 4:00 a.m. You discover thick black smoke in the hallway. What should you do?" This question was an attempt at assessing if participants knew about alternative procedures in highrise buildings, which stress the need to attempt to evacuate only if the path of egress is clear from smoke, otherwise, if there is smoke in the corridor or stairwells, to start protect-in-place activities.

'-,I,:

~.:. ',.f,@w;:,:<;;.;;

24 18 9 0 31 ;;;-;::;;: (rn@&k'ii:;;;.;

27 17 19 6 39$c::'.::!,:;!;~*f:$;t;;;2:

..-.: ,,., 51 (73.9%) 35 (50.0%) 28 (40.0%) 6 (8.6%) 70 (1 00%)Purposely, the question implied that the hallway was not safe and people should stay in the apartment and start protect-in-place actions, such as sealing the main door, calling

91 1, going onto their balcony, using a wet towel to protect their face, etc. Out of the

63 participants who answered this question, opinions are quite different; 52% would protect-in-place, while 48% would attempt to get out!

For this question, the respondent's age seems to make a difference in the option chosen, as presented in Table 14. On one hand, participants in the age ranges 20-29

and 30-39 are more in favour of protect-in-place activities instead of attempting to get

out. On the other hand, participants in the age ranges of 40-49, 50-59 and over 60, are more in favour of attempting to get out instead of starting protect-in-place activities. This result appears to indicate a clear shift in strategy in the older age groups.

Table 13: "You live on 27th floor

...

the fire alarm goes off...

you discover thick black smoke in the hallway. What should you do?"Table 14: Frequency by Age at Question 3

Answer

Protect-in-Place Get Out

Number in each group

Question 4 suggested a diierent fire scenario: "It is 2:00 a.m. and you are asleep in the second floor bedroom of your home. Your two- and four-year old children are asleep down the hall. You are the only parent in the house. The smoke detector sounds and awakens you. What should you do?" Five answers were associated with this

auestion, the freauencv for each answer is Dresented in Table 15. Women aDDf?ared

:,M&&.f:'>;

:$- ,;.: .e-:Ti::

Protect-in-Place Get Out

Total

more likely to children" and to "call 91 ' 1' than men. Men seemed more lkely to suggest "investigate" than women. Nobody mentioned the importance of closing doors

Total 33 (52%) 30 (48%) 63 (1 00%) Male 16 12 28

behhd them as ihey leave.

-

Female 17 18 35

;.,

.' ?%% :,, :? 3 (60%) 2 (40%) 5Table 15: "It is 2:00 a.m. you are asleep in the second floor bedroom

...

your two children are asleep down the hall. The smoke detector sounds.What should you do?"

2 ; , ; ; . , 3 ~ g : ; < ' , : ; g ; ~ ; ~ ~ ; ~ ! k ~ : - ~ g : . : : ;

5 (38%) 8 (62%) 13 15 (68%) 7 (32%) 22 9 (45%) 1 1 (55%) 20:@.%:$@2

1 (33%) 2 (66%) 3;:)xQ&jk:

33 30 63For this question, the frequencies across age present a similar distribution (see Table 16). It appears that age does not have an impact on the way participants answered.

Table 16: Frequency by Age at Question 4

Question 5 asked: "You are most likely to experience a fire in which one of the following situations?" As presented in Table 17, respondents had to choose one answer among 4 options. Most respondents (96%) chose that they are more likely to experience a fire in the home, but still, 2 chose "hotel" and 1 chose "office".

Table 17: "You are most likely to experience a fire in which one of the following situations?"

Finally, in Question 6 participants were asked if they had ever experienced a fire in the past. As many as 37% had indeed experienced a fire in the past, as presented in Table 18. Also 45% of the males had experienced a fire in the past while only 31 % of the females had a similar experience.

Table 18: "Have you ever experienced a fire?"

;G-*b<;...: ;;;:.;, , j ".::,.;:;,.,

.:.',;,;':

Home Hotel Office School Total . . ;;:;$;':,;: ;'ws,jir?;.?.& ,.. ,.

, . . 36 1 1 0 38:$j";!,>:<., ;,!Ma-@,.;;:. 2.i ':A,,

29 1 0 0 30

Respondents who had experienced a fire before are, as one would expect, more prevalent in older age groups (see Table 19).

Table 19: Frequency by Age at Question 6

:.:::,,, . ;;.,,:

;~wl::;;::

;

,:;, 65 2 1 0 68m.&er<,::

,--:~c.r;.

.,z ,;: &??,h Yes No Total ,,;-:,ma::;,i

14 (45.2%) 17 (54.8%) 31 ,;::; ',' ,, . . -,.. ..: , ,: , , . - . - .~ . - ~~ ..,,.,. ,,,. Yes No Total , : . ~ ~ ~ ~ j ; : ; ; ~ ; ~ ~ ; { ~ ~ ~ ~ ; y ~ : ~ p ; $ ; ~ j 3 ~ , ~ ; : c : ; ; ~ ~ ; ; ~ ~ ; ~ ~ s j 12 (30.8%) 27 (69.2%) 39 ,::2622B '. , . . .,,..~ li . ' ' "' <i__ ....[

7 ,.. , ,..$@&&;?

26 (37.1 %) 44 (62.9%) 70 ;";&&&f-;:,

7 (30%) 16 (70%) 23 1 (14%) 6 (86%) 7 7 (33%) 14 (67%) 21:i:x*[,j,j

26 44 70j;$;srn',gl

7 (47%) 8 (53%) 15~ ; ~ ~ 3 , g @ : : i

4 (100%) 0 45.6 Item Analysis of Test 2

Test 2 was administered immediately after the Fire Safety Class to assess what participants had learned from the class. The 4 tested groups received the same information on fire safety, the difference between each group was the video and teaching approach used to transmit this fire safety information. All participants of the 4 experimental groups filled out Test 2.

In a way to efficiently summarize answers in Test 2, frequencies of responses are calculated for each of the 6 questions of this test. Each group's responses will be studied individually since statistically significant differences have been found between groups.

Question 1 asked: "Which one of the following poses the greatest health risk during a fire?" The choices were; a) smoke inhalation, b) heat, c) bums and d) heart failure. All the respondents chose the right answer, a) smoke inhalation. This score is not surprising since all participants had already correctly answered a similar question in Test 1 before the Fire Safety Class.

Question 2 was designed for occupants to apply new information learned during the class about a Home Escape Plan. A simple floor plan drawing of a split-level home was given with this question: "Using the diagram below, create an escape plan for this split-level home". The proper answer to this question was composed of three elements: 1- the identification of 2 ways out of each room, 2- the location of 2 smoke detectors and, 3- the identification of a meeting place outside. Scores to Question 2 for the 4

groups tested are presented in Table 20. Out of a possible 3 points to this question, Groups 1 and 2 obtained a better score than the other two groups. Group 4 scored remarkably poorly on this question.

Table 20: Scores i n Test 2, Question 2

In Question 3, respondents had to "Explain what you should do to ensure that your smoke detector will work if there is a fire." Table 21 presents the results of the 4 groups to this question. A total of 4 points could be accumulated for the following answers: 1

-

test monthly, 2-

clean the detector, 3-

change the battery once a year, and 4-

replace the detector after 10 years. Here Groups 1, 2 and 4 scored well on that question; it is Group 3 this time that obtained the poorest score on this question.Table 21: Scores i n Test 2, Question 3

Questions 4 and 5 are especially interesting to analyze. Both these questions are the same as Questions 3 and 4 of Test 1. Since the proper answer to these questions had been discussed during the Fire Safety Class it is interesting to assess how well participants grasped the information.

Question 4 asked: "You live on the

2?'

floor of a high-rise apartment. The fire alarm is aoino off and vou discover thick black smoke in the hallwav. What should vou-

.,

do?" As presented in table 22, respondents to this question could'accumulate a tAal of 4 points bv answering: 1-

protect-in-place, 2-

call 91 1 or fire department, 3-

turn off HVAC and, 4-

go to balcony or window. One more time ~ r o u ~ s 1 , 2 and 4 obtained a much better score on this question compared to Group 3.Table 22: Scores in Test 2, Question 4

No one should answer that they would attempt to escape in Question 4, since it was explained during the Fire Safety Class that such a response would be extremely dangerous under such a scenario due to the smoke condition. Nevertheless, some participants still answered that they would attempt to escape as presented in Table 23. As many as 4 out of 14 respondents in Group 3 said they would attempt to evacuate. In all groups, most participants understood that protect-in-place activities are a valid

alternative to evacuation if smoke is blocking the evacuation route, however, a few did not understand it. In all groups, more than half who had the wrong answer in Test 1 had the correct answer in Test 2.

Table 23: Number of Respondents Who Said They Would Attempt to Escape i n Test 1 and Test 2

Question 5 was worded: "It is 2:00 a.m. and you are asleep in the second floor bedroom of your home. Your two- and four-year old children are asleep down the hall.

18 ,~!:~;;,~:?:l~,,f:.~ .,..

-

k,,*.. '~~**~:~;'z;'~/;;~;z,;~;$j ~.,.,~ 0 2 4 2:;,:;

;+,.;;~

;;,:; , ,..,-

,;.:..-

:;,.;:~::::;;~.:.,:

- , . r . i :1- News Clip Non-Part. 2- News Clip Participatoly 3- Fire Power Non-Part. 4- Fire Power Participatory

i,?. ," ;; ".{,,;ysm.q ;,,;:;:i::-:.;: ::".

. i d . , *

...

;.

..- ...:i2 8 9

You are the only parent in the house. The smoke detector sounds and awakens you. There is light smoke in the hallway. What should you do?" This question is exactly the same as Question 4 in Test 1. This time 6 points could be obtained for this question with the following answers: 1

-

react immediately, 2-

crawl low under smoke, 3-

get children,4

-

use 2"6 way out if needed, 5-

shut door and 6-

call 91 1 from outside. Scores fromthis question are comparable among the 4 groups tested, as presented in Table 24. Results for this question are very similar to the results obtained for the same question in Test 1. The only substantial difference is that, in Test 1, only 43% mentioned "Call 91 1 " as one of the things to do, while 60% mentioned "Call 91 1" as one of the things to do in Test 2.

Table 24: Scores in Test 2, Question 5

Finally, the last question of Test 2 was: "List the steps required to develop a home escape plan." Lines numbered 1 to 6 were provided for the answers. The answers expected were; 1

-

Gather family, 2-

Draw floor plan, 3-

Plan 2 ways out, 4-

Locate smoke detectors, 5-

Choose a meeting place, 6-

Practice the plan. The answers could be presented in any order. The best score to this question rests with Group 3, while Group 2 scored the lowest. Results are presented in Table 25.Table 25: Scores in Test 2, Question 6

5.7 Item Analysis of Test 3

Test 3 was the most important test of the study, since it measured the information remembered by the participants and their behaviour and altitude change toward fire safety following the Fire Safety Class. Participants were not aware that this post-class evaluation was going to occur 2 months after the class. Test 3 was a face to face

interview which was recorded. Out of the 73 participants who took part in the study there were 10 participants who were not available for the interview of Test 3: people were either on sick leave, holidays or had left their job. This section is subdivided into 5 sub- sections related to the different topics covered during the interview.

5.7.1 Participants' attitude and behaviour toward home fire safety

A few general questions were asked to participants in an attempt to identify their attitude and behaviour toward home fire safety. The following issues were not formally discussed during the Fire Safety Class so participants might not have been directly affected by the class. Consequently, totals are the most interesting results to look at, though scores are also provided for each group.

Since careless smoking is the most prevalent cause of home fire deaths,

participants were asked if someone at home smokes, and if so, if this or those persons smoked in bed. Responses are presented in Table 26. Most participants (62%) have no one at home who smokes and, among the participants who have smokers at home, no one admitted that they smoked in bed.

Table 26: "Do you have someone at home who smokes?"

Participants were also asked where they store matches and lighters. Responses were put to two categories, as presented in Table 27, out of reach or accessible. Answers such as upper cupboard or dresser were put in the "out of reach" category while on the counter or on the coffee table was put in the "accessible" categoly. Most people (67%) kept matches and lighters "out of reach". The ones who kept matches and lighters "accessible" (33%) were participants who did not have pre-schoolers or children. Among them, some specified that they would put away the matches when their grand- children were visiting.

Table 27: "Where do you keep mafches and lighters?"

Due to the prevalence of cooking fires, two questions about cooking habits were asked. First, participants were asked if they sometimes leave the kitchen when cooking to answer the phone or the door, or to watch some television. Some 33% of the

participants mentioned they never leave the kitchen when cooking. This is a surprising result since it is difficult to believe that people will stay in the kitchen when they have a roast or turkey in the oven for a few hours. However, some people may only cook on the stove which could explain some of the responses. Table 28 presents the responses to this question.

Table 28: "Do you sometimes leave the kitchen when you are cooking?"

A second question regarding cooking habits was about participants doing deep fry cooking. As presented in Table 29, very few participants (3%) deep fry regularly, a few (22%) deep fry rarely, which is 2-3 times per year, and most participants (75%) never deep fry.

Table 29: "Do you deep fry?"

Another question was related to the use of a portable heater, which is another frequent cause of home fires. Table 30 presents the results. Most participants (86%) did not use portable heaters. Group I was the only group where most people used a portable heater. This is difficult to explain, since Group 1 and the Control Group were both from the same northern city and no one from the Control Group used a portable heater.

Table 30: "Do you use a portable heater?"

5.7.2. Information retained from the Fire Safety Class

To start this section each participant was asked: "What do you remember from the Fire Safety Class you had2-3 months ago?" As presented in Table 31, responses were classified under 5 categories: Home Fire Safety, Smoke Detector, Home Escape Plan, Video, Don't Remember the Class. Interestingly, 5 participants who were in the Control Group did not remember having taken part in a class or a meeting on fire safety. All the participants in Group 4 remembered that the class was on Home Fire Safety and more specifically on a Home Escape Plan.

Table 31 : "What do you remember from the Fire Safety Class"

Participants were asked: "Was there anything new that you learned from the instructor, the class or the material distributed?" Points were given for 7 different answers. In each group, there were participants who said they learned nothing new. It should be kept in mind that most of the participants were fire wardens in their

organization, so they already knew a few things about fire safety. As presented in Table 32, Groups 3 and 4 who saw the Fire Power video were the only ones to mention what they leamed about "how to do a home escape plan" that "fire is fast" and you should "leave right away".

Table 32: "Was there anything new that your learned"

After the Fire Safety Class, each participant received a set of 4 brochures and a sticker that are reproduced in Appendix D. One brochure was on smoke detector, one was on home escape planning, two were on fire safety in apartment buildings and the sticker was on protect-in-place activities. Participants were asked if they remembered receiving these brochures. Scores are presented in Table 33. There were 8 participants who did not remember receiving any brochures so they probably discarded them rapidly.

Table 33: "Did you receive any brochures?"

The participants who remembered receiving brochures were asked if they had read them. Responses to this question are presented in Table 34. Among the

participants who remembered receiving brochures, 30 of them, thus almost half, had a

glance at the brochures, another 20 participants even took the time to read them through. Finally, 5 participants admitted not having looked at the brochures.

Table 34: "Did you read them?

Since most participants remembered receiving the brochures and 50 out of the 63 participants read or had a look at the brochures, they were asked what was the content of the brochures. Answers were put in 5 different categories as presented in Table 35. Some participants may have answers in more then one category. It is interesting to note that 42% of the participants who looked at or read the brochures remembered that the content was about Home Escape Planning.

Table 35: "What were these brochures about?"

Finally, participants were asked what they did with these brochures. Table 36 shows that 25 participants took the brochures home, while another group of 19 kept the brochures at work. Many participants mentioned that they had a specific file for that kind of information either at home or at work where they kept them. Only 4 people admitted throwing the brochures away. Four others could not recall what they had done with the brochures. There were 3 participants who gave the brochures to grown-up children who did not live at home anymore.

Table 36: "What did you do with these brochures?"

Since the 4 tested groups saw a video during the Fire Safety Class, participants were asked if they remembered seeing a video. As presented in Table 37, only two