Cues to Comparison Classes in Child–directed

Language

by

Anna Sinelnikova

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer

Science

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

May 2020

c

○

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2020. All rights reserved.

Author . . . .

Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

May 18, 2020

Certified by. . . .

Roger Levy

Associate Professor, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

Thesis Supervisor

Certified by. . . .

Michael Henry Tessler

Postdoctoral Associate, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by . . . .

Katrina LaCurts

Chair, Master of Engineering Thesis Committee

Cues to Comparison Classes in Child–directed Language

by

Anna Sinelnikova

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on May 18, 2020, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Abstract

Understanding the meaning of scalar adjectives like big requires a standard of com-parison (“big relative to what”), but that standard is almost never said explicitly. Instead, listeners must infer what comparison class the speaker is assuming using some combination of linguistic cues and the context. It is useful to look at how children come to infer the comparison class because of their limited world knowl-edge. In order to better understand this question, we undertook a corpus study of children interacting with their caretakers in their home environment. We examined the physical surroundings that the conversations took place in and certain cues in the linguistic cues that caretakers used when communicating with children using the scalar adjective big. Results suggest that speakers prefer different syntactic frames when conveying different types of comparison classes and adjust the syntactic struc-ture of a sentence to support listeners’ inferences about the comparison class from the physical surroundings. This work also contributes a set of contextual annotations for utterances containing the word big in the Providence corpus of the CHILDES database.

Thesis Supervisor: Roger Levy

Title: Associate Professor, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences Thesis Supervisor: Michael Henry Tessler

Acknowledgments

This thesis would not be possible without the support and guidance of many individ-uals. I would like to thank Roger Levy for providing me with the opportunity to work in the Computational Psycholinguistics Lab and MH Tessler for investing a great deal of time and energy into mentoring me and providing me with invaluable feedback. I would also like to thank Jon Gauthier for his technical support, Teresa Gao for contributing her annotations to the project, and Polina Tsvilodub for her kindness and insightful conversations throughout. Finally, I would like to thank Steven Shriver for his time, contributions, and guidance through the software development process.

Contents

1 Introduction 15

1.1 Comparison classes and the adjective big . . . 15

1.2 Reference–predication hypothesis . . . 18

1.3 Using big without a comparison class . . . 18

1.4 How do children learn to interpret big in context? . . . 19

2 Related Work 21 2.1 Comparison Classes and Children . . . 21

3 Purpose and Goals of the Study 25 4 Methods 29 4.1 Annotations . . . 29 4.1.1 Motivations . . . 29 4.1.2 Framework . . . 30 4.2 Collecting Annotations . . . 42 5 Results 47 5.1 Distributions of Individual Annotation Categories . . . 48

5.1.1 Syntactic Frames . . . 48

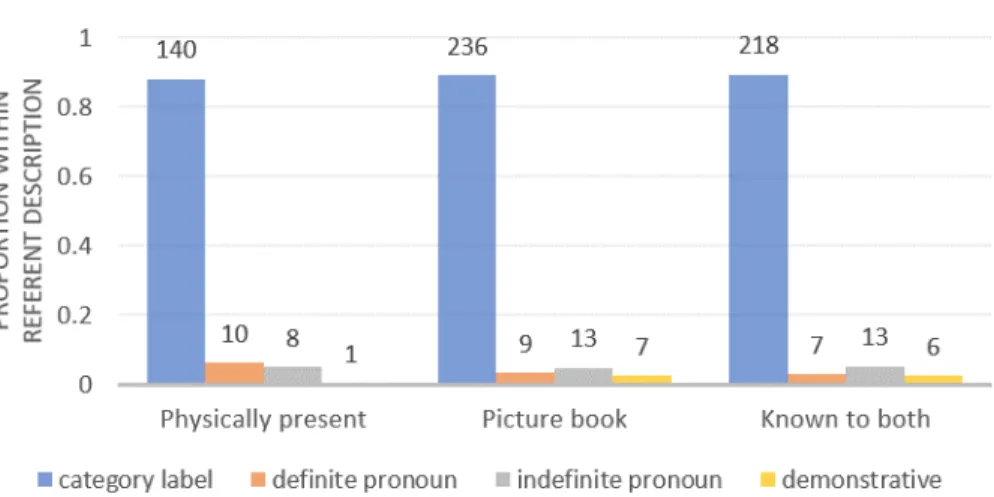

5.1.2 Referent Noun Types . . . 50

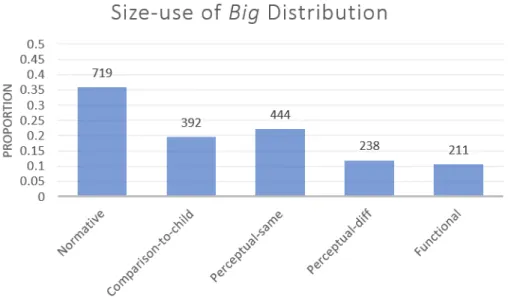

5.1.3 Size–uses of big . . . 52

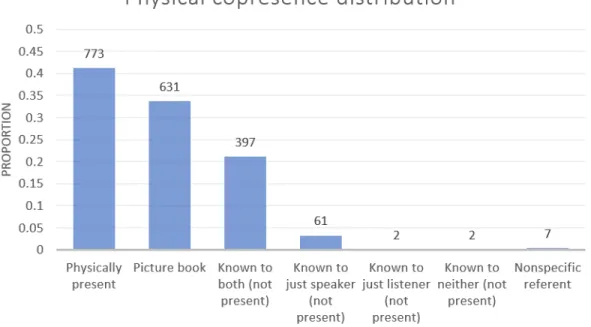

5.1.4 Physical Copresence of the Referent . . . 53

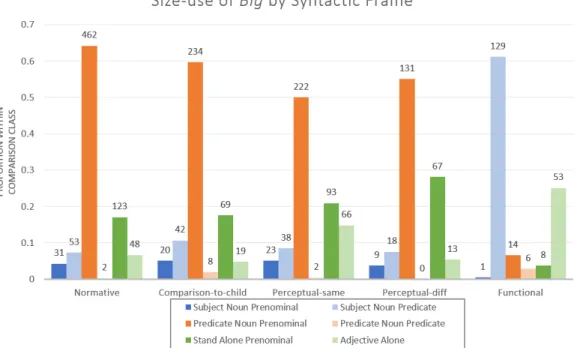

5.3 Size–uses of Big and Syntactic Frame . . . 57

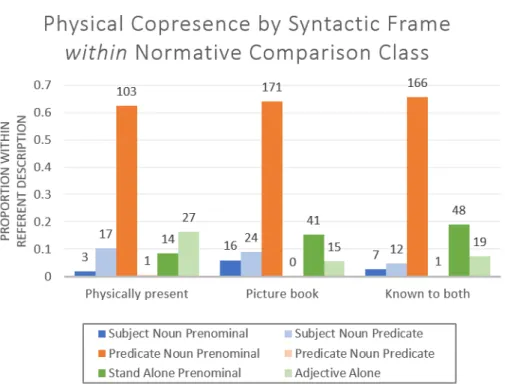

5.4 Physical Copresence of Referent and Syntactic Frame . . . 60

5.5 Size–uses of Big and Physical Copresence of the Referent . . . 62

6 Discussion 65 A Annotation Scheme Summary 71 B Annotator Disagreement Confusion Matrices 73 C System to Collect Annotations 77 C.1 Data Extraction and Preparation . . . 77

C.2 Data Representation . . . 78

C.3 Annotation Service . . . 78

C.4 Frontend . . . 80

List of Figures

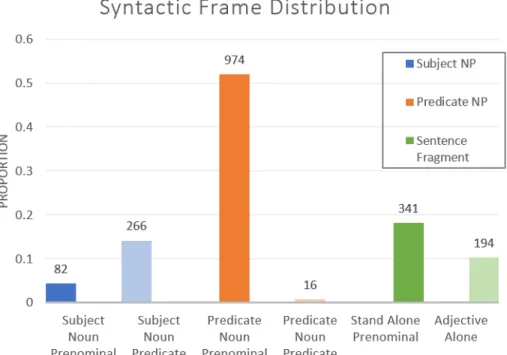

5-1 Distribution of syntactic frames across child–directed utterances con-taining the adjective big. The numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the referent type. . . 49 5-2 Distribution of noun types across child–directed utterances containing

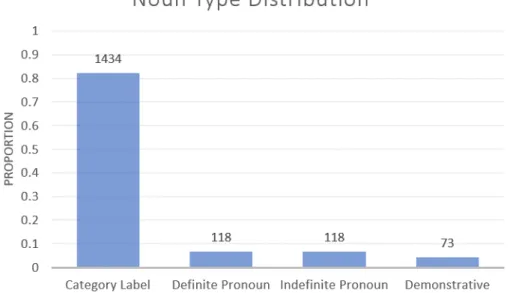

the adjective big. The numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the noun type. . . 51 5-3 Distribution of size–uses of big across child–directed utterances. The

numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the size–use. 52 5-4 Distribution of referent types across child–directed utterances

contain-ing the adjective big. The numbers represent the raw counts of ut-terances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the referent type. . . 54 5-5 Distribution of syntactic frames by referent kind within normative

com-parison class uses only. The blue bars represent syntactic frames where the referent noun is in the subject position; the orange bars where the referent noun is in the predicate position; the green bars where a sen-tence fragment was used. The numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the referent type. . . 56

5-6 Distribution of noun types by physical copresence of the referent within normative comparison class uses. The numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the referent type. . . 58 5-7 Distribution of syntactic frames by size–use of big. The blue bars

repre-sent syntactic frames where the referent noun is in the subject position; the orange bars where the referent noun is in the predicate position; the green bars where a sentence fragment was used. The numbers rep-resent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the size–use. . . 59 5-8 Distribution of syntactic frame by physical copresence of the referent.

The blue bars represent syntactic frames where the referent noun is in the subject position; the orange bars where the referent noun is in the predicate position; the green bars where a sentence fragment was used. The numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the referent type. . . 60 5-9 Distribution of size–uses of big by referent kind. The numbers represent

the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the referent type. . . 62

C-1 Tables comprising the database that stores information related to Prov-idence utterances. OTHER_METADATA includes information such as the speaker, the target child’s age, etc. . . 78

C-2 Data representation of Tasks, Annotations, and Annotator. Here, OTHER_METDATA may represent any post survey data the annotators provide. . . 79

C-3 Outline of Annotation Service with API layer shown. . . 80 C-4 Example view of webpage. . . 81

C-5 Schematic of full system showing how components relate to each other and the hosting environments (MIT Athena Server and Cloud Provider VM). The Annotation Service was published as a public container on Docker Hub under sinelki/annotation–service. . . 82

List of Tables

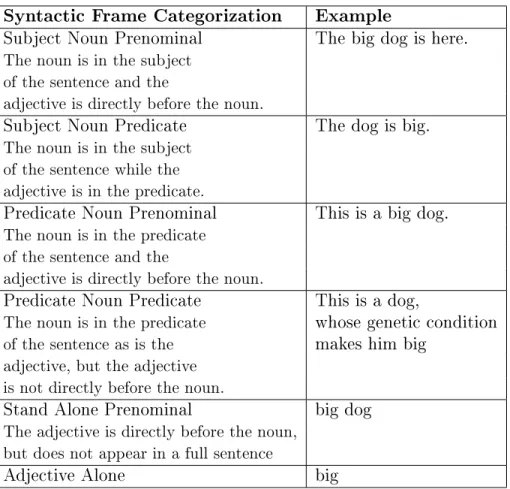

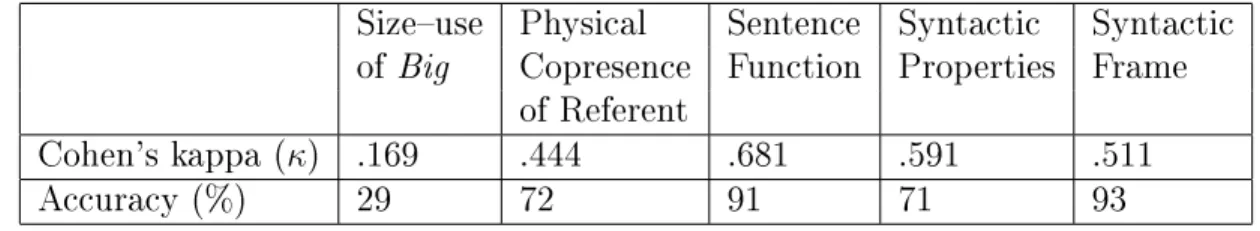

4.1 Examples of possible syntactic frames . . . 31 4.2 Inter–rater reliability and accuracy scores for each of the 5 annotation

categories on the 267 tasks annotated by me and another RA. . . 44 4.3 Number of trials where the modal selection from the pilot experiment

on Mechanical Turk is the same as the annotation I made on the same set of 10 utterances. . . 45 A.1 Summary of Annotation Categories . . . 72 B.1 Sentence Function Confusion Matrix between myself and RA

annota-tor. The rows are my annotations; the columns the RA’s. . . 73 B.2 Syntactic Frame Confusion Matrix between myself and RA annotator.

The rows are my annotations; the columns the RA’s. . . 74 B.3 Syntactic Properties related to adjectives Confusion Matrix between

myself and RA annotator. The rows are my annotations; the columns the RA’s. . . 74 B.4 Syntactic Properties related to nouns Confusion Matrix between myself

and RA annotator. The rows are my annotations; the columns the RA’s. 74 B.5 Physical Copresence of Referent Confusion Matrix between myself and

RA annotator. The rows are my annotations; the columns the RA’s. . 74 B.6 Size–uses of big Confusion Matrix between myself and RA annotator.

B.7 Size–uses of big Confusion Matrix restricted to only the normative, perceptual, and functional size–uses between myself and RA annotator. The rows are my annotations; the columns the RA’s. . . 75

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Comparison classes and the adjective big

Many of our day to day conversations rely on us remembering prior conversations, having general world knowledge, or understanding the environment around us. For example, a “big car” is a lot bigger than a “big cat”: What counts as big depends on the context. The word big, absent anything else, does not carry much meaning. What is big? And big for what? Big is an example of a context–sensitive, gradable adjective. Gradable adjectives are those that permit different degrees of that quality. Something can be a little big, very big, extremely big, etc. and it is in contrast to non–gradable adjectives such as closed (it does not make sense to say something is a little closed or very closed).

When speakers use context–sensitive adjectives, such as “big” or “tall”, they im-plicitly compare the object they described as “big” or “tall” to some standard of com-parison. This standard of comparison is known as the comparison class (Kennedy, 2007). One could rephrase utterances that invoke a comparison class by appending a for phrase at the end which would explicitly specify the set of individuals that comparison is being made to. For example, consider the following utterances:

(i) The car is big.

(iii) Steph Curry is tall.

(iv) Steph Curry is tall for a man.

(v) Steph Curry is tall for a basketball player.

Sentence (ii) explicitly indicates that the car described as big is considered big in relation to other cars that exist. In many ways, including the for phrase does not add additional information because sentence (i) conveyed the exact same meaning. On the other hand, absent any knowledge about who Steph Curry is, sentences (iv) and (v) offer different interpretations to (iii). In (iv), the comparison class is men in general but in (v) the comparison class is basketball players. Absent any contextual information that would point towards the comparison class being basketball players, the most natural interpretation of (iii) is that Steph Curry is tall for a man. Example (iii) illustrates the potential for uncertainty in the comparison class: It is not clear, without additional context, if the speaker wanted to point out that Steph Curry was tall for a man or for a basketball player. But if the speaker and listener were watching a basketball game when this comment was made, then perhaps the listener would infer that the speaker means Steph Curry is tall for a basketball player and point out that this is not true. Assuming the comparison class is understood, the next question is how big or tall must an individual be for the speaker to have called them such. Work by Kennedy (2007) shows that the threshold value above which the size of an object would be considered big can be determined by applying a degree semantics. There is no single size value that an object must have before it is considered big. Rather, this threshold is determined pragmatically (Lassiter & Goodman, 2013).

When interpreting an utterance where an object is described as big, the listener may use a comparison class that fixes a standard of comparison and evaluates the object under discussion in relation to the determined standard. Various contextual cues can help listeners infer what the appropriate comparison class is. When adult participants were asked to interpret the meaning of various utterances containing context–sensitive gradable adjectives, researchers found that participants flexibly ad-just the comparison class with world knowledge judgements (Tessler, Lopez–Brau, &

Goodman, 2017). This ability for the basis of comparison to change depending on the context is what we call comparison class flexibility. Specifically, participants were presented with underspecified sentences, such as “it is warm outside.” They were also provided with additional information regarding the speaker’s location and the time of year. The general expectation for a sentence like “it is warm outside” may be that it is warm compared to other days. However, with the information that the month was January in the northern hemisphere, participants stated that it was warm com-pared to winter days. This experiment showed that participants readily adjust the comparison class to accommodate the present context. These findings were in line with a Rational Speech Acts model that integrates world knowledge and pragmatic reasoning to infer the comparison class.

Another study tested if participants would choose different comparison classes when the noun was placed in the subject of the sentence versus the predicate (Tessler, Tsvilodub, and Levy, under review). The results indicated that participants chose different kinds of comparison classes when the referent was in the subject position (“That NP is big”) or in the predicate position (“That’s a big NP”). Specifically, basic level nouns – nouns that are the most natural, preferred label for the kind (i.e. “dog”) – were preferred in the predicate position and subclass nouns – nouns that are more specific descriptions for the object (i.e. “Great Dane”) – were preferred in the subject position (Tessler, Tsvilodub, and Levy, under review). For example:

(i) That is a big dog.

(ii) That Great Dane is big.

In sentence (i) reference is established with the demonstrative “that” and “dog” sets the comparison class – that dog is big for a dog. Sentence (ii) uses “Great Dane” to establish reference leaving the comparison class more open to interpretation. The Great Dane could be big for a Great Dane or it could be big for a dog.

1.2 Reference–predication hypothesis

The tradeoff between the role of the noun to establish reference or set the comparison class is the basis of the reference–predication hypothesis. Reference is a communica-tive goal that identifies the object under discussion for the listener. Complementing the reference goal is the predication goal, where the predicative phrase expresses a property that may apply to the referent or expresses that the referent belongs to some category (Reboul, 2001). The goals of reference and predication become important when considering the role of the noun that is described by the adjective – does the noun act to establish reference or the comparison class (or both)? We hypothesize that nouns appearing in the subject of the phrase are used for reference while those in the predicate are more likely to establish the comparison class. This distinction be-tween subject and predicate nouns was explored by the Tessler et al. (under review) study described above, and we use their results as some evidence that this tradeoff results in differences in how the comparison class is interpreted.

1.3 Using big without a comparison class

However, not every size–use of big (when big is used to refer to a referent’s size as opposed to being used in an idiosyncratic phrase) needs a comparison class to be interpreted. Consider the following:

(i) The hat is big for the doll.

In this example, “big” is used to indicate that the referent, “hat,” does not satisfy the intended goal of placing the hat on the doll’s head. The basis of comparison is the doll’s head, not other hats. In other words, one might use the word big comparatively when trying to differentiate an object from a field of other items or one might use it functionally to explain that the object does not fit the desired parameters. The fact that big can be used with or without a comparison class contributes to the challenge of learning how to interpret utterances containing the adjective big.

1.4 How do children learn to interpret big in

con-text?

Even young children have been shown to understand comparison class flexibility and select the correct interpretation when presented with different scenarios (Ebeling & Gelman, 1994). However, less is known about the linguistic and environmental cues that are available to children that help them select the correct interpretation.

In order to gain insight into the cues that help children select the correct inter-pretations of the size–uses of gradable adjectives, we need to clarify what potential size–uses there might be. The first use case is when the referent is compared to the prototypical object of that kind. When the prototypical object is the reference point, we call this the normative comparison class, following Ebeling & Gelman. Another comparative use of big can occur when speakers wish to distinguish an object from a set of visible objects. For example, it is very natural to ask for the “big bead” when crafting with a set of differently sized beads and to intend for the listener to pick out the bead that is larger than the ones around it, regardless if that bead is big compared to the prototypical bead. Such use cases employ a perceptual comparison class. There can also be functional uses for big when indicating whether an object can accomplish a specific task in relation to another object. Recall the example about the hat for the doll. In that case, no comparison class is needed. These three usage categories can be further broken down, but they highlight the main ways that comparison classes can change when the context changes.

We have chosen to do an observational study of young children in their home en-vironments focusing on the adjective big. By using longitudinal videos of children at home with their caretakers, we have access to the varied circumstances and conver-sations that children grow up with and learn from. Using this data should give us a good idea of what kinds of cues are naturally available and used when talking about objects and ideas that are big. The Providence corpus provides weekly or monthly videos and transcripts of five children as they grow from age one to four (Demuth, 2009). The videos were annotated for the size–uses of big and four potential cues

that would help establish the comparison class, if applicable. Some of these cues characterize the perceptual environment and some characterize the linguistic aspects of the utterances.

Chapter 2

Related Work

2.1 Comparison Classes and Children

Because we are interested in how children may learn to infer the comparison class, we look to prior work to understand what evidence exists for children’s understanding of comparison classes. Research has shown that by age 4, children are sensitive to the distribution of sizes of objects in the comparison class and adjust the meaning of “tall” and “short” according to the objects they were presented with (Barner & Snedeker, 2008). This study shows that children understand that their interpretation of gradable adjectives is dependent on a standard of comparison, which in turn comes from their world knowledge.

Separate studies on children 2–4 years show that children can flexibly change their interpretation of the comparison class when the linguistic and physical context was changed (Ebeling, Gelman, 1994). In this work, the researchers defined three distinct comparison class categories: normative, perceptual, and functional, which we also adopt in this work. To briefly recap: When only the referent was present and the participant needed to rely on their mental representation of the object in general in order to determine if the referent was indeed big for the category or not, the comparison class was classified as normative. When there were several exemplars of the object in front of the participant and they needed to pick out the one that was big compared to the others, the comparison class was classified as perceptual.

When there was an implicit goal to be achieved with the referent, the comparison class category was classified as functional. An example of such a goal was presented when participants were presented with hats and dolls and asked if the hat was big for the doll. The results showed that children were able to change the meaning of what was considered big when the context changed (e.g., on the first trial, big may have been intended to be interpreted normatively, while on a subsequent trial, more objects were added to the scene and big was intended to be interpreted perceptually). But understanding comparison classes is a complex task that includes understand-ing the adjective’s meanunderstand-ing and its relation to the noun. For example, the utterance “the dog is big” requires the listener to understand the meaning of “big” – it is a property that describes the size of an object – and understand how “big” relates to “dog” – “dog” is described as having the property “big.” Once this connection is in place, the next step of interpreting this utterance is understanding that “the dog” is compared to a basis of comparison, “dogs in general,” which has a distribution of sizes. For the speaker to have called the dog “big,” the referent dog’s size must have exceeded some threshold. The first step of this inference is understanding the meaning of the adjective, and studies have investigated how children learn adjectives and what linguistic cues help them extend their meaning to new situations.

Syrett (2010) conducted a study with 30 month–olds to test if they are able to learn a novel, gradable adjective and found that adverbs such as “completely” or “very” help children understand the meaning of the adjective, which in turn should help them set the threshold for the comparison class. Their stimuli were pictures of objects, some of which displayed the novel property, effectively invoking the perceptual comparison class. Sometimes, the adverb “completely” or “very” preceded the adjective. They found that children in the “no–adverb” condition did not show evidence of learning the meaning of the novel adjective, as judged by a task asking children to pick out the item that exhibited the test property from a set of two objects – one which did not exhibit the tested property and one which did (Syrett, 2010). This work demonstrates that intensifiers, such as “very,” may play a role in helping children understand the adjective, which would help them set the comparison class.

Despite children’s success in lab settings to learn new adjectives, and by extension, possibly learn the comparison class, some evidence suggests that children struggle with adjectives in naturalistic settings (Sandhofer & Smith, 2007; Ninio, 2014). Because understanding the comparison class requires one to understand the meaning of the adjective, it is important to uncover how well children learn adjectives in their home environments. Sandhofer and Smith (2007) hypothesized that perhaps the language used in naturalistic environments was not as specific and helpful to learning adjectives as the language used in lab experiments was. To test this, they set up an experiment where they asked children and their caretakers to play with toys over a time period of 24 weeks. They found that parents often used ambiguous nouns such as “one” or “this” when referring to objects or even used no noun at all and just referred to something by its color. Because parents may not be using nouns that explicitly name the object when conversing with children, it may explain why learning adjectives may be more difficult in a natural environment. Using ambiguous nouns provides a weak cue to the referent and also a weak cue to the comparison class, if there is one, because the listeners needs to first understand what the pronoun (or no noun) is referring to and then decide what the comparison class might be (if one is needed). Using named nouns would provide a much stronger cue because then the child could fall back on the named noun as being the comparison class, if there are no indications that it may be something else (recall the basic examples of “this is a big dog” where the noun “dog” directly related to the comparison class “dogs”). The child may need to lean on perceptual cues in the environment to understand the basis of comparison. This work motivates the desire to look at children’s understanding of comparison classes in a natural setting and also to pay attention to the linguistic markers present, especially the type of noun used.

Children from a young age are able to learn new gradable adjectives and apply their knowledge to change the comparison class when the context makes it appropriate to do so. We extend prior work on child comparison class understanding by looking for evidence of different types of comparison classes in child–directed speech and analyzing the linguistic and perceptual contexts in which these comparison classes

Chapter 3

Purpose and Goals of the Study

For a listener to correctly interpret an utterance with a gradable adjective, they must be able to understand when a comparison class is needed for the interpretation and if it is needed, what the appropriate comparison class is. This inference is a complex problem that requires the listener to integrate several pieces of information. We wish to gain insight into possible cues available to children in their home environment that may be used to solve comparison class inference. We hypothesize there is a correlation between the language used to communicate the comparison class and the greater context in which the comparison class is communicated.

The reference–predication hypothesis introduced in the Introduction serves as the motivation to analyze the syntactic frame the speaker chooses to use. Specifically, we are interested in the position of the referent noun, as the position of the noun may affect if it is used for reference (if it is in the subject) or predication (if it is used the predicate). If the noun is used for predication, then it is likely that the noun also sets the comparison class. Further, we believe the syntactic frame chosen may be correlated with the way the referent manifests — is it available in the environmental context or is it only available linguistically? We think it is reasonable there may be a correlation between these two factors because speakers may be less likely to use the noun for reference if reference can be readily establish via the perceptual environment. Besides paying attention to the position of the noun, we also care to note the position of the adjective in relation to the noun — does it appear prenominally

or not? Consider the difference between (i) The big dog is here.

(ii) The dog is big. (iii) That is a big dog.

Example (i) illustrates how a noun with a prenominal adjective in the subject of the sentence acts to identify a specific referent (establish reference). On the other hand, Example (ii) uses the noun “dog” to establish reference in the subject of the sentence but then predicates the property “big” in the predicate of the sentence. The way in which Example (ii) is structured may help the listener understand that a comparison class is needed to interpret the utterance and the comparison class may be “dogs.” The comparison class may be something else such as “animals”; additional context is needed to properly disambiguate the comparison class. Even with “big” appearing in the predicate of the sentence, the referent noun may be syntactically modified by “big” or not, as in Examples (ii) and (iii). As was just described, Example (ii) establishes reference with the noun “dog” and the listener is left to infer what the comparison class may be. In Example (iii), however, reference is established with the demonstrative “that” and “big dog” appears in the predicate of the sentence. In this case, the modified noun (“dog”) is more likely to be the intended comparison class. In fact, Tessler et. al (under review) found that listeners were more likely to use the referent noun as the comparison class when the referent noun was in the predicate of the sentence.

Alternatively, it is possible that the comparison class is determined by the noun phrase that is directly modified by the adjective. In that case, both Examples (i) and (iii) would be strong indicators to the comparison class being “dogs” and Example (ii) would be more ambiguous. This alternate hypothesis is another reason we are motivated to look at the position of the referent noun and adjective in the sentence and in relation to each other, and at the direct modification frame in particular.

In order to test our hypotheses, we developed an annotation scheme of linguistic and perceptual markers that might contribute to comparison class inference that are

described in Methods. We chose to do a corpus analysis focusing on the Providence corpus (Demuth, 2009) from the CHILDES database (MacWhinney, 2000) because this corpus had video data in addition to audio transcripts. The video data helped us understand the environment the conversations took place in and what physical characteristics of the environment were used to supplement the conversations.

The goal of annotating the utterances for linguistic and perceptual markers is to see which cues are correlated with which size–uses of big and if these uses constitute different comparison classes. The reference–predication hypothesis guides us to look at the syntactic frame of the utterance, and we further break down the linguistic mark-ers by looking at the referent noun that is used, if any, and what additional adjectives or adverbs there may be in the utterance. These linguistic cues may help the listener establish the basis of comparison. Additionally, looking for perceptual cues from the environment may help inform when reference is established non–linguistically. Fur-ther, this information would allow us to determine if certain contextual cues can change the basis of comparison used. To help elucidate how contextual cues might change the basis of example, consider the beads crafting example from before. If there was only one bead present, and the speaker said “Give me the big bead,” the listener may infer that the comparison class is prototypical beads. On the other hand, if there are many beads present, and the speaker said, “Give me the big bead,” the listener may infer that the comparison class is the set of present beads. Knowing if there is any correlation between different cues and comparison classes can help frame future experiments that would look for causal evidence.

By analyzing the empirical distributions of the types of comparison classes that are used in child–directed language and related cues, we will have more insight into the characteristics of the comparison class inference problem that children are learning to solve. Further, we wish to determine if all uses of comparison classes behave in the same way or if some uses need more contextual support than others.

Chapter 4

Methods

4.1 Annotations

4.1.1 Motivations

To help us identify the cues present in child–directed language and their relation to comparison class inference, we want to create an annotation framework that will support this goal. One key component of this annotation framework should be that the linguistic markers are independent of the perceptual environment the utterances take place in. Because we are looking for correlations between cues and the size– uses of big, it is important to ensure that the different annotation categories are independent of each other. We wish to identify both linguistic and perceptual cues that are used with comparison classes in child–directed language. The linguistic markers are motivated by work by Syrett (2010) who suggests that adverbs are useful cues to the meaning of adjectives (and by extension understanding the comparison class), Sandhofer and Smith (2007) who found that the type of noun used may be a strong or weak cue to the referent object, and Tessler et. al. (under review) who suggest that the syntactic frame may play a role in setting the comparison class. We also annotate for features of the perceptual environment in order to understand if there are non–linguistic cues that may help the child infer the comparison class.

4.1.2 Framework

We chose the following five annotation categories: Sentence Function1, Syntactic

Frame, Syntactic Properties, Physical Copresence of the Referent, and Size–Uses of Big, which are summarized in a table in Appendix A:

1. Syntactic Frame:

Table 4.1 demonstrates the possible syntactic frames and an example utterance in each frame. Because we think that nouns that are directly modified by the adjective (prenominal) are stronger indications to the comparison class, it was important to see which utterances contained a direct modification syntactic frame and which did not. When the syntactic frame is observed in conjunction with other factors, such as other syntactic properties or the physical copresence of the referent (described below), we can determine if there is evidence that directly modified utterances have fewer other indicators to the comparison class than other utterances.

Initially, the annotation for Syntactic Frame was simpler — either the frame had direct modification of the noun or the adjective was not directly before the noun (or neither). However, after collecting annotations, it was decided that more distinctions in the syntactic frame would be useful, so I used spaCy, a natural language processing library, to reannotate the syntactic frame. In a random sample of 100 utterances annotated by hand (I re–annotated these 100 utterances from the simpler annotation scheme to this more fine grained one) and annotated by spaCy, there was 90% agreement with a Cohen’s kappa coeffi-cient of .8382. Some of the mismatches came from utterances where the speaker

changed their line of thought mid–sentence. For example, if the utterance was “I got you a my big sister got you a bunch of coffee,” spaCy did not recognize that the sentence actually begins with “my big sister” and the “I got you” in

1Utterances could be coded as Declarative, Imperative, Question, or Other. The sentence

function is a pragmatic indicator. We did not use the sentence function annotation in our analysis, however.

2A csv file with these 100 utterances and annotations can be found in the data folder of this

Syntactic Frame Categorization Example

Subject Noun Prenominal The big dog is here.

The noun is in the subject of the sentence and the

adjective is directly before the noun.

Subject Noun Predicate The dog is big.

The noun is in the subject of the sentence while the adjective is in the predicate.

Predicate Noun Prenominal This is a big dog.

The noun is in the predicate of the sentence and the

adjective is directly before the noun.

Predicate Noun Predicate This is a dog,

The noun is in the predicate whose genetic condition

of the sentence as is the makes him big

adjective, but the adjective is not directly before the noun.

Stand Alone Prenominal big dog

The adjective is directly before the noun, but does not appear in a full sentence

Adjective Alone big

the beginning is a discarded thought. I annotated this utterance as a Subject Noun Prenominal frame because the subject “sister” appeared in the subject of the sentence and the adjective “big” was directly before the noun. spaCy, on the other hand classified this utterance as Predicate Noun Prenominal.

2. Syntactic Properties

Besides the syntactic frame, there can be other properties of the utterances that help provide grounding for the comparison class. These properties may apply to the adjective or the referent noun. Properties applying to the adjective are the presence of an intensifier/weakener, or the presence of additional ad-jectives. The referent noun can be annotated as a pronoun, demonstrative, basic noun, subclass noun, superclass noun, or no noun.

(a) Applying to the adjective, there may be an intensifier (such as “very”, “too”, etc.) or a weakener (such as “a little”). Intensifiers or weakeners help convey the degree to which the comparison is being made. For exam-ple, if the utterance is “that’s a very big dog,” listeners will be looking for a dog that is much larger than the one they will look for if the utterance was “that’s a big dog.” Weakeners would have the opposite effect – listeners will be looking for an object that is only slightly larger than the typical object. In addition to the adjective big, the modified noun may have other mod-ifiers attached to it, such as color or texture adjective. These additional adjectives would further facilitate identifying the intended referent. (b) The referent noun type is another important syntactic property. In some

utterances, the referent noun may not be spoken aloud at all but rather assumed via the other contextual cues. It may be a pronoun or a demon-strative (e.g. “that”, “this”), which would again require either prior knowl-edge of the referent or a strong physical context to specify the referent. If the noun is a named noun, then we look to Rosch et al. for inspiration on how to categorize it.

cate-gories is motivated by Rosch et al. (1976) who argue that we can impose a taxonomy on the world around us and relate concrete objects to one an-other via class inclusion. Objects at the basic level of abstraction (what we call basic nouns) are those that have attributes that are common to most (if not all) members of that category. “Dog” is therefore considered a basic level noun because the noun “dog” conjures up a mental representation of that object which has fur, four legs, among other attributes and most dogs share these attributes. “Animal”, on the other hand, does not conjure up a single mental image of that category and the members of the animal cate-gory only share a few attributes among them. Thus, “animal” is considered a superclass noun. In the other direction, “Great Dane” is a subclass noun because while Great Danes share many attributes from one instance to an-other, they also share many attributes with other categories, such as any other breed of dog.

Thus, named nouns may fall under one of the following categorizations: basic – meaning the most natural, preferred label for the noun (i.e. dog as opposed to Great Dane or animal)(Lamberts, 1997), a subclass noun – a more specific description for the noun (i.e. Great Dane), or a superclass noun – a higher level categorization (i.e. animal).

The categorization of the named noun is important because it is an indicator for the strength of the comparison class. Subclass nouns are the strongest indicators of the comparison class whereas superclass nouns are the weakest. Intuitively, this is evident when comparing the following utterances:

(i) That’s a big animal. (ii) That’s a big dog.

(iii) That’s a big Great Dane.

Example (i) uses the superclass noun, and it is natural to ask if the referent is big compared to animals in general (and the size distribution for all animals is so large, how do we decide which threshold to use?) or if the

referent is big compared to other animals of the same kind as the referent. Example (ii) uses the basic noun, and now we know that the comparison is to other animals of the same kind as the referent, specifically dogs. But is the comparison to dogs in general or the specific breed of dog that the referent is? Example (iii) provides the most clarity by using a subclass noun.

3. Physical Copresence of the Referent

The referent is the object that is being described as big. It is important to un-derstand how the referent manifests. Is it present in the physical environment? Is it a shared (or unshared) mental representation that the participants converse about? Referents that are in the physical environment, be it a tangible object that the participants can see or drawn in a picture book, may be more salient than referents that are only present in a mental representation, and these more salient referents may help to constrain the comparison class by providing a con-crete point of reference for both speaker and listener. The possible annotations for the physical copresence of the referent, which are described in more detail below, are physically copresent, picture book, known to both speaker and listener, known to just the speaker, known to just the listener, known to neither, or nonspecific referent.

Referents that are present in the surrounding environment may be physically copresent which means the referent is a tangible object that both speaker and listener can see. Alternatively, the referent may be an action (like a kick) that one of the participants physically performs. Another referent present in the physical environment may be a picture book. While both physically copresent and picture book referents are ones that participants can see, it is important to make the distinction because picture book referents exist in a more constrained context and often require the readers to construct a mental representation of the picture book world that is grounded in the illustrations. In other words, picture books create their own contexts independent of the rest of the environment.

Referents that are not present in the physical environment may instead be something that the participants know about. The referent may be known to both speaker and listener which means the both speaker and listener have a mental representation of the referent; it may be known to just the speaker which means the speaker has a mental representation of the referent but the listener might be confused or it may be known to just the listener, which would likely arise if the speaker is repeating something back to the listener that the speaker is confused about. Coding for each of these scenarios is important because it helps us understand if the participants are likely to agree on the comparison class. (If the referent is known to both, then we assume that they also agree on the comparison class, but if it’s known to only one party, then it would be very difficult for the other party to establish the comparison class.) Finally, referents may be known to neither speaker nor listener or nonspe-cific. Referents that are known to neither are very rare, but may occur in some edge cases where the participants are discussing some unknown item (i.e. “what’s a big gloop?” “I don’t even know what a gloop is”). Nonspecific refer-ents may arise when the utterance uses big in an expression rather than in a size use. For example, “eating cheese is her big thing these days.”

Guidelines for annotation of physical copresence of referent

When annotating for the physical copresence of the referent, it was clear when the referent was physically co–present or in a picture book because of the videos. However, deciding to whom a referent was known if it wasn’t physically present is a more subjective judgement. I used my best judgement to decide if partic-ipants were actively engaging in the conversation about the referent and thus demonstrating knowledge of it (known to both). If the listener was ignoring statements about the referent and thus demonstrating that they may not know about it, I annotated this as known to just speaker. If the speaker is actively asking questions about the referent, thus demonstrating that they do not have a mental representation of it, but are interested in constructing one, I annotated

this as known to just listener. See the above example about “gloop” for a concrete example of how to decide when the referent is known to neither.

4. Size–uses of big (including Comparison Classes)

The last of the five categories is size–uses of big. When a referent is described with the adjective big (at least when the usage is a size–use), speakers will use a basis of comparison that is potentially influenced by the context in which the conversation takes place. The basis of comparison can take on several forms, some of which are comparison classes such as the normative or perceptual comparison class. Other times, the basis of comparison is a functional use of the adjective big and is not considered a comparison class. When size–uses of big employ a comparison class, the comparison class may be different, depending on the contextual inputs. The ability for these comparison classes to change based on context is called comparison class flexibility. To accurately understand the intended usage of big, one should draw on the linguistic context (where the usage of big occurs within a conversation) as well as the physical environment (objects in the speaker’s immediate surroundings) may influence the usage of big.

Here’s an example: Let’s say there are three pairs of baby shoes, with one pair slightly larger than the others and there are no other shoes around. If the speaker were to say, “hand me the big shoes,” the listener would likely reach for the pair of baby shoes that is larger than the other baby shoes. The size–usage of big in this case was steeped in the perceptual context. The speaker likely intends for the listener to use the “present shoes” as the basis of comparison. The listener would try to resolve the meaning of the word big by observing their immediate environment, which contains the three sets of baby shoes. These environmental clues may give the listener enough information to understand that the “present shoes” form the basis of comparison as opposed to shoes in general. We may be able to argue that in this example, the listener determined that the use of the word big employed a perceptual comparison class and resolved the comparison

class to be the “present shoes.” Compared to shoes in general, none of the baby shoes are big. But the physical environment of only baby shoes is what makes the comparison class the “present shoes”. The comparison class in this case is implicit because it is not overtly stated in the utterance that only the “present shoes” are the basis of comparison.

Inspiration for how to categorize the various types of uses of big was taken from Ebeling and Gelman (1994) where they study children’s sensitivity to the comparison class in a normative, perceptual, and functional setting. We use their definitions for the contexts that big might be used in and further subdivide the normative and perceptual usages as follows.

(a) Normative

Normative uses of big would invoke the listener to retrieve the basis of com-parison from a stored mental representation3. These types of comparisons

are the normative comparison class. When the speaker chooses to make an utterance that uses the normative comparison class, they are using their stored mental representation. They do so because the referent they have identified must have exceeded the threshold to be considered big for the comparison class they have in mind. The listener then must infer what the comparison class is from the information in the utterance and their surrounding context. Consider the following two scenarios:

(i) The speaker is recounting their day when they say, “I saw a big dog at the park.” (Further assume that there are no animals around the participants.)

(ii) Two people are talking when a dog walks past them and one of them says, “That’s a big dog.”

3Relying on a stored mental representation of the object is not the only way to interpret a

normative–typical comparison class. This definition is based on the Ebeling & Gelman (1994) work. Lassiter & Goodman (2013) argue that comparison classes give a probability distribution over degrees of size for the given object. Regardless of the machinery that is used to interpret the representation of the comparison class, what is important to the normative–typical comparison class is that the basis of comparison is some representation of the abstract category.

In scenario (i), the listener does not see any dogs around him, so when the speaker says they saw a big dog, the listener must use a stored mental representation of dogs and assume that the dog the speaker is thinking of must be bigger than this generic representation of dogs that the listener has. In scenario (ii), the listener can see the referent but does not see any other dogs that would serve as a reference point, so when the speaker says that they see a big dog, the listener can compare the dog he sees to the stored mental representation of generic dogs.

Guidelines for annotation of normative use–case

When deciding if an utterances contains a normative use of big, I first identified if a comparison class is needed to interpret the utterance. If yes, I inferred what the comparison class was that the speaker was probably intending to convey. Then I evaluated if the referent’s size was indeed greater than the threshold (that I arrived at intuitively) for that comparison class.

(b) Perceptual4

The distinction that will be made between perceptual–same and perceptual– different uses of big lies in the fact that in the perceptual–same classifica-tion, the comparison class is the kind of objects present at the basic level (e.g. dogs) whereas in the perceptual–different classification, the compari-son class is the higher level categorization of objects (e.g. animals). This difference is important because the threshold value for an object to be con-sidered big would be different if the comparison class is the superclass versus the basic level. Knowing which comparison class to use is dependent on the physical context, and we want to annotate for these two situations in order to see if there is any difference in any of the other cues present.

4A common set of objects that were annotated with the perceptual use–case (when appropriate)

are toys. As detailed in the Collecting Annotations and Discussion sections, toys present a unique difficulty in finding the correct annotation for them because they are described with nouns that are the same nouns used for the real objects (i.e. “toy trucks” are still referred to as “trucks”). We did not have a separate size–use category for utterances relating to toys, but this may be a reasonable extension to make to this work.

(i) Perceptual–Same uses of big are a subdivision of the perceptual use case Ebeling and Gelman define. In their study, the perceptual usage is employed when there are several objects, which may or may not be of the same kind, that are physically present and a comparative adjective is used to select one object from the rest. In our annotation scheme, we chose to be more specific about the kinds of objects that are present. In the perceptual–same category, the objects that are present are all of the same kind (e.g. all dogs), where the kind is determined by the noun used in the utterance If a named noun is not used, then the kind is determined by the kind of object the speaker is referring to, which would be made clear by the preceding context (what the participants were just discussing or what objects the participants are currently interacting with). For example, if the intended referent is a teddy bear, then the set of objects would be other teddy bears present in the context. In perceptual–same uses, the comparison class is the set of objects that are physically present.

(ii) Perceptual–Different uses are the second subdivision of the percep-tual comparison class. As the name implies, this usage is employed when there are several objects physically present, but they are of dif-ferent kinds (e.g. cats, dogs, and horses), where the kind is determined by the noun used in the utterance. If no named noun is used, then the kind is determined by what the pronoun or demonstrative refers to. If no noun is used and reference is established solely with percep-tual cues, then the kind is determined by the class of objects that the referent belongs to. For example, if the intended referent is a teddy bear, then the class of objects would be stuffed animals.

Guidelines for annotation of perceptual use–case

The definitions above specify that if the objects in the present context are all of the same kind, then it is a perceptual–same usage. However, there are often many objects of all different kinds in the home environment and

knowing which objects are part of the present conversational context and which are not can be tricky. In deciding which annotation to choose, I relied on the referent noun used, if it was available: If the referent noun was a superclass noun, then it was likely that the intended usage was perceptual– different. If it was a basic or subclass noun, then it was likely that the intended usage was perceptual–same. If a named noun was not available, but a pronoun was, then I relied on prior conversational context to deduce what named noun the pronoun is replacing and followed the previously stated rules. In the case of no noun explicitly stated in the utterance, I implicitly applied a label to the referents the speaker was referring to and followed the previously stated rules with that label in mind.

(c) Functional

Functional uses of big are another categorization of big usages that we borrowed from the Ebeling and Gelman study. Functional uses arise when there is an implicit goal and the referent object is not suitable for the goal. For example, in the utterance, “The hat is big for the doll,” the implicit goal is fitting the hat onto the doll’s head, the ideal object is a well–fitting hat, and the referent is bigger than the ideal object for the task. This usage is distinct from the normative one because the hat does not need to be big for hats in general in order to not fit the doll. It is distinct from the perceptual–different usage because the hat may or may not be bigger than the doll itself, and this is not the comparison being made. Instead, the usage is specific to the function that hats placed on dolls’ heads should fit appropriately. It is possible that functional uses of big yield a comparison class that is the set of objects that may satisfy the goal. It is also possible that functional uses of big do not employ a comparison class at all. It is not the goal of this work to understand if functional uses rely on a comparison class, but rather to annotate for different usages of big.

Guidelines for annotation of functional use–case

utterances that fell under this use–case were stating that some referent was “too big” for something or someone else. In other words, the referent was intended to be used to fulfill some goal, but the referent was not the correct size for that goal. To do the annotation, I identified if a goal was implicitly (or explicitly) stated and if the referent was intended to fulfill the function of satisfying that goal. If yes, the utterance was annotated as a functional use of big.

(d) Comparisons to the Child

We hypothesize that the language adults use when communicating with young children may have some unique uses of the adjective big. Specifically, we believe that adults may choose to call items created by the child as big not because the items are big compared to the objects around them or that they are big compared to the general representation of that object, but rather because they are big given the child’s size or abilities. For example, if a young child builds a snowman, it is likely that this snowman is not con-sidered big under the normative comparison class. However, an adult may still tell the child that it is a big snowman. They may say this because when the child’s physical size and capabilities are considered, then the snowman may indeed be big. An example when a comparison–to–the–child use of big arises but the comparison is not to the actual child in the room would be in a picture book scenario. Perhaps, the character in the book is a child who is doing something or interacting with an object that would not be considered normatively big but is big in relation to the character’s size or abilities. This isn’t to say that utterances that are a comparison to the child cannot also be normative. Rather, these utterances are made with the listener’s (child’s) size or abilities as part of the basis of comparison. These utterances may also employ a comparison class – continuing the snowman example, perhaps the comparison class is the set of all snowmen the child could build – but we do not assert that a comparison class is needed. Guidelines for annotation of comparison–to–child use–case

As was explained above, to decide if an utterance was an example of a comparison to the child, I identified if the speaker was likely to be taking into consideration the child’s size or abilities when making the utterance. Often, complimentary types of utterances would imply that the speaker was considering the child’s abilities (i.e. “wow, you built a big snowman!”). Similarly, if the dialogue in a picture book that was being read made it clear that the character was a child (or child–like) and the speaker made statements about a referent in relation to the character’s size or abilities, this was also considered a comparison–to–child annotation.

(e) None

Sometimes, speakers use the adjective big, but they are not referring to the size of an object. For example, phrases like “it’s not a big deal” is not a size use of big and thus, does not fit into any of the above categories. In the annotation scheme, these utterances were denoted by none to indicate there was no size–use of big.

The size–use categorizations are not mutually exclusive. One scenario could be eval-uated through multiple perspectives and be valid in several of them. For example, if there is an array of shoes, and the speaker asks for the big pair of shoes, the listener may use the perceptual–same comparison class to pick out the bigger pair of shoes. But if one of the pairs is an oversized pair of clown shoes, then the listener may also employ the normative comparison class to reason that the clown shoes are big for shoes in general.

4.2 Collecting Annotations

In order to solicit annotations for each of the target utterances, a custom software solution was built to support the annotation framework5. The implementation details

5The dataset containing the collected annotations can be found in the repo:

https://github.com/sinelki/providence_data_pipeline.git in a csv called annotations.csv. The annotator “AS” refers to myself, “TG” refers to the RA, and the other annotators are anonymized Mechanical Turk workers.

of the software system is described in Appendix C. I used this system to annotate all utterances of interest on my own. Then to determine how reliable my annotations were, another RA annotated 267 of the utterances (without conferring with me about the utterances or annotations). Table 4.2 displays the inter–rater reliability scores for each of the 5 annotation categories, and Appendix B has the full confusion matrices. Accuracy scores were calculated by taking the number of utterances for which the annotations matched exactly divided by the total number of utterances annotated by both annotators (267). All categories had moderate to substantial agreement except the size–uses of big. This is not surprising because the this classification is the most subjective measurement, the one that requires the most domain knowledge to complete, and because there is no gold–standard classification scheme for size– uses. Additionally, because more than one size–use could be employed in the same utterance, achieving high agreement in this annotation category was difficult as one annotator could have marked an utterance as normative and perceptual while the other only marked it as perceptual. In my analysis, if the annotation did not match perfectly, then it was counted as a mismatch. In fact, if we collapse the categories to be just normative, perceptual, and functional, then there is 72% agreement (𝜅 = .47). The disagreement in the physical copresence of the referent can be explained by the fact that the “known to _” categories are very subjective and can be difficult to annotate. If we only consider the physically present and picture book categories, there was 96% accuracy (𝜅 = .80) in the annotation. Most of the disagreement came from the one annotator marking an utterance as “known to just speaker” and the other deciding it was “known to both” or other similar situations. The syntactic properties annotation had a similar annotation difficulty as the size–usage because annotators could choose more than one syntactic property for the utterance and they needed to match perfectly to count as an agreement.

Finally, once the system was tested and improved for usability, it was released on Amazon Mechanical Turk to solicit annotations from workers. A small pilot exper-iment was run where all turkers annotated the same 10 utterances so that we can understand how much agreement there is from the general population on the size–

Size–use Physical Sentence Syntactic Syntactic of Big Copresence Function Properties Frame

of Referent

Cohen’s kappa (𝜅) .169 .444 .681 .591 .511

Accuracy (%) 29 72 91 71 93

Table 4.2: Inter–rater reliability and accuracy scores for each of the 5 annotation categories on the 267 tasks annotated by me and another RA.

use distinctions. Before turkers could annotate the 10 utterances, they were walked through the definitions of the annotation categories and asked to complete 7 practice trials. They had to get all annotation categories for all 7 practice trials correct be-fore they could move on to the 10 real trials. Preliminary analysis of 16 participants indicates that there is some agreement amongst annotators, but a larger experiment would need to be run to get reliable data.

Table 4.3 displays the number of trials where the modal response from the turkers matched my annotation in each category. The only category where there was some substantial disagreement is the size–use of big – again, this is the most subjective annotation category. Taking a closer look at one of the discrepancies in the comparison class annotation, we see that the utterance under consideration was “big truck”. The mother and child were playing with toys when the mother pulled out a toy truck and said, “big truck.” My intuition was to call this size–use perceptual–different because the toy truck was not abnormally large for toy trucks and the other objects around the child were other kinds of toys. The truck was indeed big compared to the toys around it. The modal response from the turkers, thought was that this was a comparison–to– the–child. This example illustrates that toys are a difficult situation to think about: the toy truck was made to look like a real truck, but the mother did not call it a “big toy truck”, she called it a “big truck.” Absent the video, the utterance “big truck” might imply the comparison class is “trucks,” but in fact, it is “toy trucks.” Did the turkers reason that the truck was intended for the child and being bigger than the other toys the child had was therefore “big for the child”? This example shows one of the ways annotating for the comparison class is open to interpretation of what

Size–use Physical Sentence Syntactic Syntactic of Big Copresence Function Properties Frame

of Referent #utterances

with same

annotation 5/10 9/10 10/10 10/10 10/10

Table 4.3: Number of trials where the modal selection from the pilot experiment on Mechanical Turk is the same as the annotation I made on the same set of 10 utterances.

Chapter 5

Results

When speakers want to communicate something with a size–use of the adjective big, the syntactic frames of their communication may change according to their current situations (physical contexts). We think the distinction between size–uses of big is important because different ones may manifest via different cues, and some uses may employ a comparison class while others might not. There are perceptual cues such as the physical copresence of the referent and linguistic cues such as the syntactic frame and referent noun type that work together to help the listener establish reference and the basis of comparison. While the noun may act to both establish the referent and the basis of comparison, the basis of comparison itself may be more flexible when the noun is used to establish reference. In this section, I analyze the distribution of size– uses of big found in the Providence corpus and the relations between the comparison class types and other cues.

Before performing the analysis, I removed certain utterances that do not constitute uses of the adjective big that are explicitly and only about the size of the referent. For example, common phrases such as big deal use the adjective in a more metaphorical sense. In addition, phrases such as big girl/big boy are an idiosyncratic use of big because the speaker is (usually) not implying that the child is big compared to other boys or girls their age, but rather that the child’s actions are praiseworthy or mature for their age.

in order to be informative to their listener. Thus, we perform the analysis on child– directed utterances (utterances produced by adults) because those are more likely to be produced by informative speakers. In addition, we are interested in characterizing the input children receive in order to inform potential theories of adjective learning.

5.1 Distributions of Individual Annotation Categories

We first look at the distributions of each annotation category to understand the overall linguistic and perceptual patterns found in child–directed language.

5.1.1 Syntactic Frames

We hypothesize that the syntactic frame of the utterance can provide a clue to the comparison class, if there is a comparison class. Related research has shown that when the adjective directly modifies the noun (i.e. “big dog”), then that noun is more likely to be comparison class than when the adjective is not found prenominally, but rather in the predicate of the sentence (i.e. “that dog is big”). In this case, the noun is used primarily to establish reference, leaving the comparison class to be more flexibly determined (e.g. by world knowledge) (Tessler, Tsvilodub, and Levy, under review).

Table 4.1 demonstrates the possible syntactic frames and an example utterance in each frame. If it is true that prenominal modification of the noun provides a stronger cue to the comparison class and if we assume that speakers use language that aims to unambiguously deliver the intended meaning, then we would expect to see some form of prenominal modification to be used in majority of utterances. Further, we think that the placement of the noun in the subject or predicate changes its primary utility from reference to comparison class. Thus, we expect more utterances using prenominal modification of the noun in the predicate of the utterances than in the subject, as this syntactic frame is where the comparison class is communicated most clearly.

Figure 5-1 shows the distribution of these syntactic frames in the Providence corpus.

Figure 5-1: Distribution of syntactic frames across child–directed utterances contain-ing the adjective big. The numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the referent type.

Overwhelmingly, utterances used prenominal modification of the noun (75%). The most predominant syntactic frame is the Predicate Noun Prenominal one. In this frame, most utterances are similar to it is a big NP where reference is established in the subject part of the sentence and the comparison class is being set in the predicate. By establishing reference in either the subject of the sentence or via some other cue, the noun modified by big acts mainly as the comparison class. This is a more helpful construction than one where the noun modified by big serves to establish reference and the comparison because in that case, we need to infer two things from one noun. The second most common frame is the Stand Alone Prenominal frame (e.g., big NP), where again, reference must be established via other cues, perhaps a pointed finger or the immediate physical context and so the noun acts to set the comparison class. This analysis shows that the speakers favor using prenominal modification when describing something as big, and more specifically, they favor placing the prenominally modified noun phrase in the predicate. Because the modified noun phrase occurs in the predicate, the subject of the utterance must use a different noun (or no noun) to establish reference, and so then the modified noun acts only as the comparison class.

5.1.2 Referent Noun Types

Another linguistic cue is the noun used to refer to the object of interest (referent noun type). The referent noun type can be a strong cue to the object of interest if it is the category label for the object (basic, subclass, or superclass nouns) or a weaker cue if it is a pronoun.

While we coded for basic, subclass, and superclass categorizations of the noun, we are collapsing across those three possibilities into one classification: Category Label. The Category Label noun is a noun that names the object it refers to explicitly. We further broke down the Pronoun category into definite and indefinite pronouns. “One” is considered an indefinite pronoun while “it” would be a definite pronoun. The reasoning for this distinction is syntactic: It is correct to say “big one” but not “big it”. In other words, definite pronouns cannot be prenominally modified by the adjective. As Figure 5-2 shows, using the category label of the referent is the

Figure 5-2: Distribution of noun types across child–directed utterances containing the adjective big. The numbers represent the raw counts of utterances that fall into each category. The y–axis is the normalized proportions within the noun type.

predominant noun type with over 80% of utterances using the category label. This results differ substantially from the Sandhofer & Smith work (2007). When looking at utterances that contained adjectives with a size–use, they found that the category label was used in 38% of utterances (compared to our 82%), the indefinite pronoun was used in 21% of utterances (compared to our 7%), and the demonstrative was used in 24% of utterance (compared to our 4%). Their study did not look at definite pronoun usages. Of course, our work uses the Providence corpus for analysis and restricts the adjective to only big while their work was a longitudinal lab experiment with no adjective restrictions, so the data is not the same. Further, their study ran for 24 weeks and the parents and children were always playing with the same toys while the Providence corpus follows children for several years and the parents and children discuss/play with whatever they want. Therefore, it is possible that the differences are due to the fact that in the Sandhofer & Smith study, parents chose to use less informative nouns because their prior visits to the lab play space had already introduced the objects into the parents’ and children’s context and so the parents chose not to repeatedly use the named noun to refer to the objects.