“Poor Books”: Going Back to

Adrienne Mounnier’s “livre pauvre”

Jan Baetens

Résumé

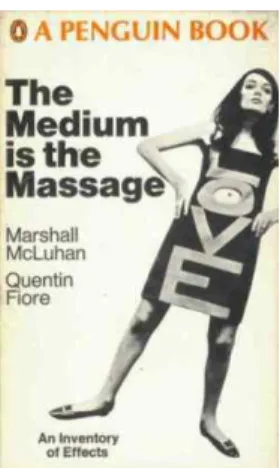

Tout le monde accepte l’idée que le livre du futur doit être différent du livre tel que nous le connaissons aujourd’hui, et dont l’existence est mise en question par la révolution numérique. La survie du livre dépend en d’autres termes de sa remédiatisation, dont un bel exemple était donné par McLuhan et Fiore dans The

Medium is the Massage de 1967, un livre qui a révolutionné les codes de la typographie. Les exemples de

remédiatisation plus récents tendent surtout à mettre en valeur ce qui distingue le livre de l’écran, sur le plan visuel comme sur le plan tactile. Cette démarche est fort louable, à condition de ne pas détourner l’attention des qualités d’autres types de livres, apparemment plus conventionnels, comme les « livres pauvres » dont la libraire Adrienne Monnier faisait déjà l’éloge dans les années 30. Le présent article donne d’abord une contextualisation de la définition comme du plaidoyer de Monnier pour une telle « pauvreté ». Il s’attache ensuite à réfléchir sur le statut et les possibilités de ce type de livres au 21 siècle, à l’ère du livre post-numérique.

Abstract

It is commonly accepted to the book of the future will have to be different from the book as we know it today, and whose future in endangered by the digital revolution. The book, in other words, will have to be remediated (as did already Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore in The Medium is the Massage, 1967), a publication that revolutionized book design). Most recent and current remediation proposals tend to highlight what makes books different from screens, such as for instance its multiple visual and sculptural aspects. There is of course nothing wrong with this plea for this type of remediation, but it should be possible to stress as well the virtues of other types of books, for instance the type that Adrienne Monnier (the famous Parisian bookseller and co-publisher of the first Ulysses) called in 1931 the “livre pauvre” (“poor book”, all connotations welcome). In this article, first contextualize Monnier’s definition of and plea for such a “poor book” and then try to suggest that this kind of book, which seems to be the opposite of what the remediated book of the post-digital era should look like, can still inspire all book lovers of the 21st Century.

Keywords

“The book,” Umberto Eco famously stated in This Is Not the End of the Book, “is like the spoon, scissors, the hammer, the wheel. Once invented, it cannot be improved.” (Eco and Carrière 2012, 19). However, we all know that in spite of its exceptional solidity as a cultural form, the book –which I will consider here in its traditional meaning as the book in print– is changing all the time. Its material aspects are always evolving and similarly the uses of the book are equally shifting at almost any moment. The material and aesthetic changes may seem easy to understand. Tastes vary, as can be seen in the eternal debate on ideal typography, which hovers between the two extremes of transparency and opacity (for some good typography is “invisible” typography, for others real books bring their typographical features to the fore). And to think about books inevitably also means to think about the technology and the economy of the book, which dramatically influences the ways books are made (issues as cost reduction on the one hand or enlarging the possibilities of print technology on the other hand are no details in book history).

The digital revolution we are experiencing since various decades is different, for it changes the very “essence” of the book, which is based on the combination of a host medium (the material form of the book) and a sign (the text or more precisely the content, for there is more than just words in a book). Host medium and content are no longer necessarily linked. On the one hand, this dissociation is seen as a liberation: the content can be more easily moved from one host medium to another (certain cyber-utopians have claimed that content is now “free” to move, but we all know the limitations of this freedom). On the other hand, this liberation has modified our perception of the book, which is no longer seen as something that helps materialize and communicate a content but also as an instrument that obstructs the content: digital content is easier and cheaper to move than print, while the content of the book itself is limited, it is argued, by the necessity to obey the linearity and fixed character of print. The useful attempts to deconstruct or nuance the dichotomy between printed content and digital content (see Hayles 2008) have not succeeded in superseding the widespread belief that print is a somewhat outdated and limited host medium.1 As a result, it does no longer suffice to adapt the book to new media environments, as done by Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore in

The Medium is the Massage (1967), a publication that revolutionized book design (Fig. 1). On top of the

agenda today is a completely different objective: saving the book at a moment when some like to believe that the book is a medium that belongs to the past.

Fig. 1: Front cover of McLuhan and Fiore, The Medium is the Massage (1967)

1One should analyze as well to what extent the digital revolution, that is the dissociation of host medium and content, has also

changed our perception of content itself. The idea that content is now “free”, “liberated” from the constraints of the host medium is not only an illusion, it is also an illusion that may jeopardize the status and value of content itself. But this is another debate. For a critical rereading of digital culture as pure content, see Tennen (2017).

Does the progress of digitization mean that the book will disappear? The answer is of course “no”. The production of books is still increasing, not only because the digital alternatives do not always work, but also because the public is still willing to pay for books. More generally speaking, it is important to stress that the digital revolution is just one new step, although a very radical and important one, in the historical transformations of the book, which cannot be reduced to the shift from “old” print to “new” digital forms (in that sense, it may be interesting to compare with the debate on the “end” of cinema [Gaudreault and Marion 2015]).

Yet in spite of these observations, the idea that the book is in crisis is a deeply rooted cultural belief of our times. This belief, which is also a fear, results from two basic observations. First, as always stated, the book itself has lost some of its prestige. Second, the cultural field we traditionally associate with the book, namely literature, is clearly suffering from the competition with other, often less time-consuming leisure activities. The crisis of the book, then, is less the crisis of the book itself than of one of its privileged domains (it would not be absurd to make here a comparison with the crisis of reading: if we think people read less than before, and if we think that this is a problem, the major reason of this fear is not the fact that people read less but the fact that they read less “good” books (for a discussion of this point, see Schaeffer 2014). It should be stressed that both elements, the loss of prestige as well as the competition with other leisure media, are not necessarily linked to the digital revolution, which only intensifies a crisis that was already on its way. Already the New Wave generation of the 1950s was claiming that the writer of tomorrow should write with a camera and use it as a pen –and there as well the supersession of the book by the film remained something relative (see De Baecque 2013 for a discussion of the presence of writing and the book within New Wave cinema).

If there are good reasons to nuance, if not to challenge the idea of a crisis, if not the death, of printed books, the very existence of a belief in this idea cannot be denied. The fundamental error, however, is to identify the digital revolution as the main element that explains this crisis, whose fundamental roots are, I believe, elsewhere, namely in the increased competition between cultural and leisure activities on the one hand and the decreasing prestige of the leisure activity we most spontaneously associate with the book, namely literature. It is important to take this into account when discussing some of the tactics and strategies that have been developed to solve –or at least to soften and to delay– the crisis of print.

The most generally expressed concern in this regard is that of the material properties of the book, which should be designed in such a way that they cannot be copied or emulated on screen, so that the public will be prevented from reading and buying the content in a digital format. This makes sense, obviously, but it also comes with a cost, which I think is twofold. First of all, this way of approaching print continues to suffer from the dichotomy between screen and page. Perhaps it is time to consider totally new forms of printmaking, that do not take the screen as their opposite, but that try to invent new types of books that expand on the new screen culture. In France, this is for instance the ambition of Jean Boîte publishing (Fig. 2), which try to remediate digital content as print (and not the other way round). Second, and this is the point I would like to highlight, the ambition to stress the material aspects and qualities of print may produce a kind of “demediation” (see Stewart 2010; for a critical discussion, see Baetens and Sánchez-Mesa 2019), a term coined to label the work of visual artists using books and texts in a purely visual and sculptural way or as part of a (nonliterary) performance. Well represented in modern art, this cultural practice refers more generally to a radical shift in our approach of the book, no longer as the host medium of a certain content, but as an independent object generating specific meanings regardless of their content in print.

Fig. 2: Screenshot of the home page of JBE (Jean Boîte Editions)

Once again, this tendency is far from new, but one immediately sees the possible dangers of this demediation, which replaces a certain idea and use of the book by a completely different one. To a certain extent, this danger also exists within the traditional sphere of printmaking, and even within the sphere that certain defenders of the printed book present as a possible solution to its current crisis, namely bibliophilism. Here, the content is of course not abandoned, as in demediation art. Nevertheless, bibliophilism clearly underscores the importance of the host medium, which in certain cases may produce a relative fading out of the content (if the ideal bibliophile publication also has an exceptional content, quite some bibliophile publications reduce their textual content to a kind of alibi).

Yet if one sticks to the idea that the book is both host medium and content, other solutions should be possible. In this regard, it is perhaps time to make a plea for something completely else, that does not seem on top of the agenda of all those who try to save the book in the era of digital publishing: the “poor” book, following the term coined around 1930 by Adrienne Monnier (Fig. 3), the famous bookseller and literary activist best known for her role in the defense of James Joyce’s Ulysses (Monnier 1960).

Fig. 3: Front cover of Monnier, Rue de l’Odéon (2009), which contains a reprint of “Éloge du livre pauvre”

A small terminological caveat is necessary at this time of the argument. The concept of “livre pauvre” (poor book) has recently also emerged in the context of the artist book (the Wikipedia page on “livre pauvre” even reduces the use of the concept to the field of the artist book production, which is definitely a historical mistake). In the context of book art, the poor book is defined in the following way, which exemplifies very well the already mentioned logic of “demediation”, ubiquitously present in today’s debates on the uniqueness of books:

“Les « livres pauvres » constituent des collections « hors commerce » de petits ouvrages où l’écriture manuscrite d’un poète rejoint l’intervention originale d’un peintre. C’est en 2003, dans le cadre du Prieuré de Saint-Cosme, situé près de Tours et où est mort Ronsard, qu’a eu lieu la première expositions de ces collections lancées par Daniel Leuwers, qui comprenaient alors une soixantaine de livres.” (Mazo 2010, n.p.)2

For Adrienne Monnier, on the contrary, a “livre pauvre” is something completely else. The “poor” book is not the “new” neither the “hybrid” book that the combined efforts of remediating and demediating artists and publishers are building these days –often with excellent results. It is, literally speaking, a cheap book, that does not have the ambition to use all the technical and aesthetic possibilities of printmaking that are available at a certain moment in time. It is, to quote Adrienne Monnier, a book that is as simple as possible: just a book, just print, just something to read in a small and affordable format, deprived of any aesthetic pretention, but which for exactly all these reasons succeed in doing what a book should do. Please allow me to quote the final paragraph of Monnier’s text:

“Oui, à la réflexion, il me paraît certain que les grands livres ne sont jamais si bien logés que dans les

2 “Poor books” refer to series of small and private press books directly sold to the public which combine the handwritten text of a

poet and an original artwork by a painter. The first exhibition of this kind of books took place in 2003, at the Priory of Saint-Cosmas near Tours, the place of death of Ronsard. The event was organized by Daniel Leuwers and the various “poor book” series entailed at that moment some sixty volumes. (My translation).

livres pauvres, ils ne sont même vraiment grands qu’ainsi. Ce sont les livres pauvres qui leur assurent une circulation obscure, vitale, comme le cours du sang ; eux, qui par leur humilité en maintiennent la gloire ; eux, qui leur donnent la liberté dont ils ont besoin pour remplir leur mesure et pour la dépasser ; eux, qui travaillent le mieux à les rendre immortels.”3

Besides the systematic use of the word « book » to name the content as well as the host medium, it is interesting to remind a meaningful detail of this text’s editorial history. Today, we read it as a chapter of Monnier’s memoir, Rue de l’Odéon, but its first publication was in the Art et Métiers graphiques (1927-1939), a magazine published to showcase through literary articles and contributions on printmaking and print history what a certain modern high-tech print company (Fig. 4), Deberny & Peignot, was capable of offering to its customers, yet in a spirit that was decidedly anti-bibliophile. The goal of Arts et métiers graphiques was to show that it was possible to print high quality books that did not fall prey to the aesthetic and economic flaws of the French bibliophilism of that period, namely the excessive cost of the books, on the one hand, and the almost fetishistic tendency to overuse typographical gadgets at the expense of a well-thought and well-balanced relationship between text and image, between host medium and content. The models, techniques, and best practices that Deberny & Peignot was displaying in its deluxe magazine were certainly no examples of “poor books”, on the contrary. However, the general spirit was not unlike that of the series and collections defended by Monnier. In both cases, that of Arts et Métiers graphiques and that of the examples discussed by the bookseller and sometimes publisher, one finds the same idea and the same use of the book. A book is not just something to look at, but to read, and its cheapness is a key aspect of its success as a cultural form.

Fig. 4: Cover of the Arts et métiers graphiques issue (1931) in which was published Adrienne Monnier’s “Éloge du livre pauvre”.

3 Yes, the more I think of it, the more I am convinced that there is no better way to publish great books than to publish them as poor

books. I even think that great books are only really great when published that way. It is thanks to their appearance as poor books that great books can circulate in obscure yet vital ways, exactly the way blood circulates in the body; it is the humility of poor books that maintain the glory of great books; it is poor books that offer great books the liberty they need to do what they have to do and even more; it is poor books that work best to make great books immortal. (My translation).

I have quoted the last words of Monnier’s text, but the opening words are no less significant. Monnier starts with words of praise for the “beautiful” book, the “rich” book if you want. It is important to underline that the poor book she is about to defend is not a book that wants to do away with ideas of beauty, comfort, and fitness. Yet it is good to remind that poor books are also suitable to do what other, typographically more sophisticated and culturally more prestigious books can do, namely bring together a form and a content, a medium and a creation, which always deeply shape and invent each other. Books in print do not have the monopoly of this creation. Digital publications can do it as well and both forms will not only coexist and interact in many different forms. But it would be a mistake to think that books will only survive if they abandon their own poverty.

The publication policy of most avant-garde groups is highly symptomatic in this regard. If there exists a strange companionship between avant-garde and elite publishing – it suffices to think of the Surrealist movement, sometimes both violently committed to the dismantling of capitalist society and eager to be involved in the most exclusive and art trade and restricted market for bibliophile editions – many other groups actively promoted cheap publications forms and formats. The Belgian Surrealist group, more precisely its Brussels connection, has generally adopted a DIY policy as far as publication was concerned, the great example being of course Correspondance, their first periodical organ, produced over seven months in 1924

and 1925 by Paul Nougé, Camille Goemans, and Marcel Lecomte. It was made up of twenty-two A4 single-sheet tracts, printed on left-over paper found at a local print shop. Its short, dense texts critiqued contemporary literary personalities, tendencies, and events. The issues were printed in a modernist typeface, on different color papers (depending on what could be found at the shop around the corner), and they were distributed by mail, to selected recipients. Unlike their Parisian associates, the Belgians made here an explicit choice against the book as a host medium for literary and other experiments (Baetens and Kasper 2015) and their approach was at the same time DIY and much ahead of their times, for instance by the choice of mail art as a distribution system.

Similar observations can be made in comparable domains and other periods. Underground comics are unthinkable without the use of fanzines and DIY micro comics –all quite different from the current situation of the graphic novel, which has dramatically moved from the cheap comic book format to often very expensive deluxe hardback publications (for a critical discussion of this turn, see Hatfield 2006 and Pizzino 2017). Even a strongly institutionalized group as OULIPO (“workshop for potential literature”), the avant-garde group that has given a new life to the age-old tradition of constrained writing, continues to publish in small copy runs very simple issues of its “bulletin”, before their –initially totally unplanned– anthological trade publication (for the editorial policy of the group, see Bloomfield 2017).

More generally speaking, and to conclude by opening a new but not so different debate, the defense of poor books can of course not be dissociated from issues of cultural policy and cultural activism, such as the notion of “elitism for all”, a key issue in the revival of French publishing and typography in the postwar period, as illustrated first by the creative work of Massin as well as Pierre Faucheux (both great promoters of affordable quality), and second by the violent polemic that accompanied the introduction of the “Livre de poche” in 1953 (on these anger and fears, see Damisch 1976). “Serious” readers were afraid that visual design and marketing would become more important than content and reflection, for pocket books were seen as books to buy, to have, to exhibit, to look at, but not to read, whereas their publishers were accused of recycling virtually anything, thus refusing to make distinctions between “good” and “bad” literature. Pocket books in the view of these skeptic, generally left-wing observers were not “real” books, just ersatz books, objects to

look at instead of texts to be slowly, carefully, closely read. These complaints sound very familiar in our current electronic times, where it is often said that browsing readers do no longer read complete texts and thus miss part of their complexity (Waters 2004), whereas texts tend to be considered as mere content, dematerialized and open to intermedial and cross-platform exchanges (Thompson 2010). Books, some argue, become free-floating content, deprived of everything what had made a book a book for many centuries, and the shift to e-books, quite a hype and an anxiety in the years that Thompson researched his almost anthropological study on the publishing business. Both the metamorphoses of the pocket book as that of electronic publications show however that dichotomizing ways of thinking are not always the most fruitful ones, at least not when it comes down to books. True, the book has been changed by the pocket business as it has been uprooted by e-publishing, and a return to previous states or even a status quo are actually unthinkable. Things change, even as “perfect” an object as a book, to quote once again Umberto Eco. And to make sense of these changes, it is not possible to put between brackets a historical as well as comparative dimension.

Bibliography

Baetens, Jan, and Michael Kasper. 2015. Correspondance. The Birth of Belgian Surrealism. New York,

Peter Lang.

Baetens, Jan, and Domingo. Sánchez-Mesa. 2019. “A Note on ‘Demediation’: From Book Art to

Transmedia Storytelling (With an Example of Writing with Ghosts and Dust).” Leonardo, forthcoming. (doi: http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/LEON_a_01541)

Bloomfield, Camille. 2017. Raconter l’Oulipo (1960‒2000). Paris : Honoré Champion. Damisch, Hubert. 1976. Ruptures cultures. Paris: Minuit.

de Baecque, Antoine. 2013 [2001]. La Cinéphilie. Invention d’un regard, histoire d’une culture.

1944-1968. Paris : Fayard.

Eco, Umberto, and Jean-Claude Carrière. 2012 [2009]. This Is Not the End of the Book. Translated by Polly McLean. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press.

Gaudreault, André, and Philippe Marion. 2015 [2013]. The End of Cinema? A Medium in Crisis in the

Digital Age. Translated by Timothy Barnard. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hatfield, Charles. 2006. Alternative Comics. Jackson, MS: The University Press of Mississippi. Hayles, N. Katherine. 2008. Electronic Literature. Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press.

Jean Boîte éditions/editions: https://www.jean-boite.fr/ (last accessed June 22 2018). Leuwers, Daniel. 2008. Richesses du livre pauvre. Paris : Gallimard.

Mazo, Bernard. 2010. « Daniel Leuwers. La Belle Aventure des ‘Livres pauvres’ ». Online : http://revue-texture.fr/La-belle-aventure-des-Livres.html (last accessed June 22 2018).

McLuhan, Marshall, and Quentin Fiore. 1967. The Medium is the Massage. An Inventory of Effects. London: Penguin.

Monnier, Adrienne. 1960 [1931]. « Eloge du livre pauvre. » In Rue de l’Odéon. Paris : Albin Michel, 249‒ 255. Original publication in Arts et métiers graphiques 25 (1931) : 7‒10.

Pizzino, Christopher. 2017. Arresting Development: Comics at the Boundaries of Literature. Austin: Texas

University Press.

Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. 2014. Petite écologie des études littéraires - Pourquoi et comment étudier la littérature ? Paris : Thierry Marchaisse.

Stewart, Garrett. 2010. “Bookwork as Demediation.” Critical Inquiry 36 (3): 410‒457.

Tennen, Denis. 2017. Plain Text. The Poetics of Computation. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Thompson, John B. 2010. Merchants of Culture. The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century. London: Polity.

Waters, Lyndsay. 2004. Enemies of Promise. Publishing, Perishing, and the Eclipse of Scholarship. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Jan Baetens is professor of cultural studies at the University of Leuven, Belgium. Some of his recent books are À voix haute. Poésie et lecture publique (2016) and The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel (2018), coedited with Hugo Frey and Steve Tabachnick.