DEWEV

HB31

.M415Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

The

Causes

and

Consequences

of

Attending

Historically

Black

Colleges

and

Universities

Roland

G.

Fryer,

Jr.Michael

Greenstone

Working

Paper

07-1

2

April

9,2007

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can be

downloaded

withoutcharge

from

the SocialScience Research

Network

Paper

CollectionatThe

Causes

and Consequences

ofAttending

HistoricallyBlack

Collegesand

Universities*Roland

G.Fryer,Jr.Harvard University and

NBER

Michael GreenstoneMIT

and

NBER

April

2007

We

aregratefultoDavid Card,David Cutler,Bryan Graham, Chang-TaiHsieh, LawrenceKatz,HenryLouis Gates,Jr.,EdwardGlaeser,Lani Gunier, CarolineHoxby, GlennLoury, Enrico Moretti,AndreiShleifer,LawrenceSummers,colleaguesattheMellonFoundation,andparticipants innumerousseminars.Fryerisespeciallythankful

totheMichorfamilyinKritzendorf,Austriafortheirsupportandgeneroushospitalitywhileworking onthe paper.

This papermakesuseoftheCollegeandBeyond(C&B)database.The

C&B

databaseisarestricted-usedatabase. Researcherswhoareinterested inusingthedatabasemay

applytotheAndrewW.

Mellonfoundationforaccess.Sam

Schulhofer-Wohl, Sheldon Bond,JorgSpenkuch,ElizabethGreenwood, andPaulTorelliprovided exceptionalresearch assistance. All errors are ourown. Correspondence can be addressed to Fryerat the Department of

Economics, HarvardUniversity, 1805CambridgeStreet,Cambridge

MA,

02138,(e-mail:rfryer@fas.harvard.edu);orGreenstoneatDepartment of Economics,MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology, 50MemorialDrive,E52-359,

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

The

Causes and Consequences

ofAttending

HistoricallyBlack

Collegesand

UniversitiesABSTRACT

Until the 1960s, HistoricallyBlack Colleges

and

Universities(HBCUs)

were

practicallytheonlyinstitutions of higherlearning

open

to Blacks intheUS.

Using

nationally representativedatafiles

irom

1970sand

1990scollege attendees,we

findthat inthe 1970sHBCU

matriculationwas

associatedwith higher

wages

and anincreased probabilityofgraduation,relative to attending aTraditionally

White

Institution(TWI).By

the 1990s,however,thereisawage

penalty, resultingina

20%

declinein therelativewages

ofHBCU

graduatesbetween

thetwo

decades.We

alsoanalyze the College

and

Beyond's 1976and

1989 samples ofmatriculateswhich

allowsus tofocus

on two

ofthemost

eliteHBCUs.

Between

the 1970sand

1990s,HBCU

students reportstatistically significant declines in the proportion that

would

choose thesame

college again,preparation for getting along with other racial groups, and

development

ofleadership skills,relativetoblackstudentsin

TWIs.

On

the positiveside,HBCU

attendeesbecame

relativelymore

likely to be

engaged

insocial, political, andphilanthropic activities.The

data providemodest

support for the possibility thatHBCUs'

relative decline inwages

is partially due toimprovements

inTWIs'

effectivenessateducatingblacks.The

data contradictanumber

ofotherintuitive explanations,includingrelativedeclineinpre-coUegecredentials(e.g.,

SAT

scores) ofstudentsattending

HBCUs

and

expenditures perstudentatHBCUs.

Roland

G.Fryer,Jr. . Michael GreenstoneHaiward

University ' 'MIT

Department

ofEconomics

Department

ofEconomics

1805

Cambridge

Street 50Memorial

Drive,E52-359

Cambridge,

MA

02138

Cambridge,MA

02142

andNBER

^^ -andNBER

Introduction

Historically Black Colleges and Universities

(HBCUs)

have a proud and storied role in theeducation and progress ofBlacks in America. For nearly a century, Historically Black Collegesand

Universities

(HBCUs)

werepractically theonlyinstitutionsof higherlearningopentoBlacksintheUS.Today, roughly

20%

ofallcollege goingBlackschooses toattend one ofthe 103HBCUs

and theseinstitutions are responsible for

22%

ofcuirentbachelor's degrees granted to Blacks. W.E.B. Dubois(Wilberforce), Ralph Ellison (Tuskegee), Martin Luther King, Jr. (Morehouse), Thurgood Marshall

(Lincoln),Ruth

Simmons

(Dillard),andOprah Winfrey(Tennessee State)headlinealonglistoffamousHBCU

alumni.Among

Blacks, 40%) ofallcongressmen, 12.5%) ofCEOs, 50%) of professorsatnon-HBCUs,

50%

of lawyers,and80%

of judgesareHBCU

graduates.'HBCUs'

successes arein nosmallpartdue to theirsubstantial financialsupportfrom federal,state,andtoa lesserdegree, localgovernments. Between 1977and2001,61%)to73%o of public

HBCUs

revenues

came

frompublic fiinds. Whilenumbers aresmallerforprivateHBCUs,

public supportstillaccounts for nearlya third oftotal revenues. In theyears 1999-2001, annualtotal public support of

HBCUs

averaged roughly $2.65billion(2005$) (Provasniketal.2004).Despitetheirpastsuccessesandhistoricalimportance,

HBCUs

areatacrossroadstoday. In U.S.V. Fordice("505U.S. 717 (1992)), the SupremeCourtinstructed state legislatures to find"educational

justification" for the existence of

HBCUs

or integrate them; the latterwould completely alter theirmission. Inresponse,

some

HBCUs

experienced declinesin enrollment,others havepursued dramaticincreasesinthe fractionofnon-Blackstudents,anda

number

ofHBCUs

haveseenimportantdeclinesintheirfinancial positions.^

The

Supreme Court'scall foran "educationaljustification"issurely related to theabsence ofconvincing evidence on the causes and consequences of attending an

HBCU

for Blacks.HBCU

proponents claim that they provide an idyllic learningenvironment that is free from thepressures of

discriminationandracism. It isalsoarguedthat

HBCUs

helptobuildimportantsocial capital forBlacksby engendering a strong sense of

communal

responsibility and civic consciousness and providingnetworkingopportunities forhigh achievingBlacks(Drewry and

Doennarm

2001). Iftheseargumentsare correct, then

HBCUs

offerunique opportunities foreducafional and social development ofBlackstudentsandtheargumentforremaining segregatedseemsjustified.

Thedata sourcesareCongressionalBlackCaucus(congressmen), BlackEnterprise(CEOs),

US

Departmentof Education, OfficeofCivilRights(professors),and Ehrenberg(1996)(Lawyers andJudges).Therulinghadan adverseeffectonmanyHBCUs.AlcornStateexperienced a9.9%decreaseinenrollmentand

Mississippi ValleyState a20.1% decrease.OtherHBCUs,especiallyinNorthCarolina,haveshown substantial

increasesinintegration.ElizabethCityStateincreasedfrom1

1%

whitein1980to23.7%

in1998,Fayetteville Statefrom 11.9to22.2,NorthCarolina Centralfrom4.1to 13.4,andWinstonSalem from 11.3to18.0. Inotherstates,

On

the other hand, it is possible thatHBCUs

are inferior to Traditionally White Institutions(TWIs)inpreparing Blacksforpost-collegelife. Ifstudents aretakinglesschallenging coursesfi-omless

distinguishedfaculty,haveaccesstopoorresources,or arenotinvestinginthe socialskillsnecessaryto

interactwith diverse sets of people, then graduates willperform poorly inthe labormarket and have

inferior non-labor market outcomes. In this scenario, the case for supporting

HBCUs

with publicresourcesappears weak.

This paper empiricallyassesses the causes and consequences of

HBCU

attendance so that thefuture decisionsby governments, students,and parents arebased on evidence, ratherthantheoriesand

historicalanecdotes.

We

analyzethi^eelargedatasetswith adequatepreandpostcollegeinfonnationforBlacksthat identify thestudents'choice ofcollege and whetheritisan

HBCU.

Thedata setsare: theNational Longitudinal Sui^veyofthe HighSchool Class of1972 (NLS-72), Baccalaureate and

Beyond

(B&B), and theCollege and

Beyond

database (C&B).The first two datasetsprovide a snapshot ofa nationally representative sample ofHBCU

studentsat two points in time: 1972 and 1992. The third datasetcontainsfourHBCUs,

Howard, Morehouse, Spelman, andXavier,allowing ustotake afocused lookintothemosteliteHBCUs

in 1976and 1989.Althoughthere areimportantlimitationswith each ofthese datasets,togethertheyprovidea rich portraitofthecausesandlabormarketandnon-labormarket

consequencesof

HBCU

attendance. Importantly,thesedata setssamplecollegematriculatesinthe 1970sand 1990s so it is possible to assess

how

these causes and consequences changed during these twodecadesof dramaticsocialchange.

The analysis uses four separate statistical approaches to adjust for pre-college differences

between

HBCU

andTWI

attendees.We

beginbyusingthe richsetofcovariatesonfamilybackgroimdandhigh schoolacademic achievement(including

SAT

scores) tofitleastsquares models.We

then usethe same pre-college covariates to implement a propensity-score matching estimator to assess the

robustnessofthe results to functional formassumptions aboutthe observables. These approaches are

supplemented by methods that are designed to account for selection bias due to missing outcome

observations

(Heckman

1979) and bias which emergeswhen

colleges admit students based partly oncharacteristics unobsei"ved in our data that are positively correlated with future outcomes (Dale and

Ki-ueger 2002).

Theresults arerobust acrossthesefourmethods. However,lackingarandomizedexperimentor

credible quasi-experiment, thorny issues ofselection

may

remain. Consequently,we

urge caution ininterpreting the results as causal.

Togetherthenationallyrepresentative

NLS

andB&B

revealan importantchangeinthe returnstoHBCU

attendance. In the 1970s,HBCU

matriculationwasassociatedwith higherwagesand an increasedpenalty. Overall, thereis a

20%

declineinthe relativewagesofHBCU

graduatesinjusttwodecades.Interestingly, relativepre-collegemeasures ofstudent quality

(SAT

scores,e.g.)improvedamong

HBCU

attendeesduringthisperiod,so higher achievingstudentswereincreasinglychoosingtheseschoolsatthesametimethatthe returns forattendingtheseschoolswerefallingbehind.

Theunderlying sourceofthedeclinein

HBCU

perfoiTnanceisunlikely tobeimportantforpolicyreasons,giventhehighcourt's stance. Nevertheless,understandingitwouldbe of considerableinterestto

researchersand educationalpractitioners. Thedata fail tocontradict, and in atleast one specification

support, the possibility that

HBCUs'

relative decline is partially due to improvements in TWIs'effectivenessateducatingblacks. In contrast,thedatacontradict a

number

ofintuitiveexplanationsfor the decline in outcomesamong

HBCU

attendees—

for example, educational expenditures per studentincreasedmoreat

HBCUs

thanatTWIs

betweenthe 1970sand 1990s.The

C&B

provides a rare opportunity to assess the most elite colleges. Here too, there isevidence of a

wage

decline between the 1976 and 1989 cohorts but it should only be consideredsuggestive because these estimates are imprecise. There is stronger evidence that the later

HBCU

matriculateswerelesssatisfiedwiththeirchoice ofcollegeandself-reporteddevelopingfewerleadership

andsocialskillsthatarevaluableinpost-collegelife,relativeto

TWI

students.On

theotherhand,thelatercohortwassignificantlymoreHkelytobeinvolvedin political,social,andphilanthropicactivities.

Thepaper proceedsasfollows. SectionIIprovides abrief historyof

HBCUS

andtheirimportantrole intheeducation of blacksinAmerica. Section IIIreviews sometheoretical explanationsfor

why

blacksmightbenefit (orbe haniied)byattending ahistoricallyblackcollege or university. SectionIV

presentsthedataand

summary

statistics.SectionsV

andVI

report resultsonthecausesandconsequencesof

HBCU

attendance. Section VIIsummarizesthe differencesbetweenthe resultsfromthe 1970sand1990sandassesses alternativeexplanationsforthese differences. Lastly,Section VIII concludes.

A

dataappendix describesthe detailsof oursampleconstmction.

:

.•II.

A

BriefHistory of HistoricallyBlackCollegesandUniversitiesA.Ante-BellumPeriod

The1860Censuscounted4.4millionBlackpeopleintheUnitedStates,mostof

whom

lived intheSouthernstatesand wereheldas slaves.Prior to theend ofthe CivilWar,teachingslavestoread or

writewasprohibitedby law(or socialcustom)in

many

areasofthe South.Still, therewerethreeBlackcolleges founded before the Civil War: the Institute for Colored Youth (now

known

as CheneyUniversity) was founded in Pennsylvania in 1837; Lincoln College in Pennsylvania, 1854, and

Wilberforce College in Ohio, 1856. All of these universities served secondary and post-secondai'y

the Freedmen'sBureau, black communities and their churches, and private philanthropists organized

schoolsforBlacks(Donohue,Heckman, and

Todd

2002).B.Post-Civil

War and

theSecondMorrillLand

GrantDuring theperiod immediately following the CivilWar, there was adramatic increase in the

number of educational institutions geared toward blacks, funded primarily through groups like the

AmericanMissionary Association, theFreedmen's Bureaus,and southernstate governments,especially

duringthe Reconstructionperiod. Between 1865 and 1890, overtwo hundredprivateblackinstitutions

were founded in the south. Very few ofthese early institutions awarded bachelor's degrees. The AmericanMissionary Association,theFreedmen'sBureaus,andothergroupsthatwereactiveintheearly

educationoffreedblacksplayed alarge roleinestablishingsome standardof education

—

mostnotablyliteracy

—

thatwouldbe importantwhen

degree grantinginstitutionsforBlacksopenedenmasseinthe1890s.

Mostpublic

HBCUs

trace theirhistorytothesecondMoixill Act,passedinAugust 1890.Inthenext decade,16

HBCUs

openedtheirdoors.TheMorrillActallowedfor the creationofa two-tiersystemof landgrant universities, with southernandborderstatescreating

HBCUs

principally togain accesstofederal"funds to develop white land grant colleges. These

HBCUs

were largely limited to vocationaltraining;well-knownagricultural,mechanical,andtechnical institutionssuchasNorthCarolina

A&T

andFlorida

A&M

were foundedduringthisperiod.By

1895, publicHBCUs

hadawarded 1,100 college diplomastoblackstudents.Yet, liberalartseducation, as was offered at

many

public white institutions, remainedunavailable toblack students.DuringtheJim

Crow

erainthesouththatfollowedReconstmction, educationalopportunities forwhitestudentsexpanded andblackswerealmost completelyexcludedfromwhiteinstitutions.

Inthe 1896 decision,Plessy v. Ferguson (163 U.S. 537(1896)), the two-tier system of higher

education, basedon the incentive structure in the Second MorrillAct,

became

more finnly set.As

aresult,

HBCUs

begantobecome

institutions thatprimarily trainedteacherstoteachinsegregated publicschools. The rapid expansion of black high schools in southern urban areas set in motion a

supply-demand

chaininwhichavailabilityof teachingpositions,supportedbystatetreasuries,drewmoreblackstudents into

HBCUs

to qualify themselves for teaching positions (Roebuck andMurty 1993). Therebecamean interdependencebetweenthepublicschoolsystemand

HBCUs.

C. World

War

IIand

theHigherEducation Actof 1965HBCUs,

aswellasother institutionsof higherlearning,facedafundingcrisisinthe1940sduetowasestablished, raising$765,000 for

HBCUs

inits firstfixndingcampaign;threetimesasmuch

ashad beenraisedbythe individualcollegesinthepreviousthree years.The landmarkdecisionin

Brown

v.Board

ofEducation (349 U.S.294(1955))andthe legislationdevelopedtoimplementitimprovedthe plightof

many

HBCUs.

TitleIIIoftheHigherEducationActof1965, which was devoted to "Strengthening Developing Institutions" was interpreted as primarily

refen-ingto

HBCUs. As

aresultmany

HBCUs

benefitedgreatlyfromthefederalfundsprovidedunderTitleIII, funds that couldbe used for faculty and studentexchanges, faculty improvement programs,

cumculum

improvements, studentservices, visiting scholarsprograms, and administrative improvements.Despitethematerialgains to the

HBCUs

arisingundertheHigherEducation Act,theNAACP

continueda legal strategy ofattacking the two-tiereducationalsystem, asking the U.S. Department of

Health,Education,andWelfaretoenforcethe CivilRightsActof1964 andprohibitsouthernstatesfrom

operatingasegregatedhighereducation system.In the1973 case of

Adams

v.Richardson (356F.Supp.92(D.D.C.),modifiedandaffd,480F.2d1159 (D.C.Cir.1973)), the

NAACP

won,requiring that statesdevelop desegregationstrategies thatwouldallowforabetter racialmixofstudents, faculty,andstaffin

publiccolleges,andincrease theaccessandretentionofminoritiesat alllevelsof highereducation.The

ruling

was

primarilyaimedatnon-HBCUs,

however,andthecourtmade

itclear thatfulfillingthe ruling'smandateshould notbeaccomplishedattheexpense ofordetrimenttotraditionallyblackcolleges

The

Adams

decisionincreasedfunding forHBCUs

becausethedecisionstated that statescould notmeettheirmandates byclosingHBCUs

andthattheymustinsteadinclude "yardsticks"tomeasuretheimprovementof blackcolleges' facilitiesaswellas theiracademicprograms.

The

court'sreasoningwasthatthiswastheonly

way

possible toensurethatHBCUs

wouldbecome

desirable institutions forwhitestudents.

D.The UnintendedConsequences ofU.S.v.Fordice - . •. ,;•::;.'':;-^ , r

:.:,y.

.%'/

^^On

June 26, 1992, theSupreme Court decided U.S. v. Fordice, adecisionbroughtby ablacklitigant withthechiefaim ofremoving structural differencesbetween

HBCUs

andtraditionally whiteinstitutions.Theplaintiff, representedby the

NAACP,

brought thesuitbecause ofthe disparity inthenumber

and qualityofthe academicprograms, instmctionalstaff,andphysical plant facihties, arguingthatthisresultedfromthe "historicallyoperatedraciallysegregated dualsystemsof higher education."

Thecourt ruled thatitwouldbe wastefultomaintainthe two-tiersystemthathad beenerectedduring an

eraof de juresegregation,notingthatMississippihadeight institutions, fivewhiteandthreeblack,and

thatfour ofthem(two whiteand twoblack)werewithin 25 milesof oneanother. Thedecisionwasa

victoiy forcivilrightslawyers,ordering Mississippi and 18 othersouthernstatestodomoreto integrate

However,themling hadan adverseeffecton

HBCUs

becausethecourtorderedstate legislaturestofind"educationaljustification for thecontinued existence"ofthetwoparalleleducation systems. The

consequencesofthismlingforthe futureof

HBCUs

isunclearat thispoint,butatleastthreeoutcomesseempossible: 1)adecisionthat

HBCUs

areindispensablefor theeducation of Blacksandanincreaseinpublic funding; 2)increased recruitmentand matriculationof whitestudents,whichhasthe potentialto

underminetheunique missionandcultureoftheseinstitutions;and3) adecisionthattheynolongerare

necessary(or asnecessary)andacommensuratereductioninpublicfinancial support.

The remainder ofthe paper assesses empirically the causes and consequences of attending

HBCUs,

whichwillhelpdeterminetheir"educationaljustification."III.Conceptual

Framework

There are at least three theories for

why

blacks would benefit from racial segregation ofinstitutions of higher education. First,

Tatum

(1997) argues that racial grouping is adevelopmentalprocessinresponsetoracism. Thisargumentgoesthatsegregationbyraceisa positivecopingstrategy

thatallowsindividuals to gathersupportthrough shared experiencesandmutual understanding. Second,

Wilson's (1987) pioneering study ofthe South Side ofChicago argues thatthemigration oftalented

blacks from black neighborhoods had adverse effects on the individuals left behind.

A

similarphenomenon

may

existforsegregation acrossschools- lowabilityblacksmay

benefitfromsegregationthroughmoreintensive interactions with theirhighabilitypeers. Third, segregatedsocial connections

within schools

may

alsoreduce adverse peerinteractions resultingfrominterracial contact.FryerwithTorelli(2006)showsthat racialdifferencesinthe socialprice foracademicachievementareexacerbated

inenvironments withmoreinteixacialcontact.

Thereare also several theories for

why

racialsegregation acrosscolleges anduniversitiesmay

harm

blacks.A

well developed literature emphasizes theimportance of peer groups (Coleman 1966), social interactions (Case and Katz 1991, Cutler and Glaeser 1997), and network externalities (Borjas1995, Lazear1999), especially foryouths.

Many

arguethat these effects areimportantinthefonnation ofskilland valuesandthedevelopmentof

human

andsocialcapital.Moreover,segi-egationacrossschoolsmay

lead to the development of an "oppositional culture" and the enforcement of other negativebehavioralnonns(Ogbu 1989). Additionally,segregationacrossschoolscan preventpositive spillovers

betweenraciallydefinedpeer groups (Lazear1999).

A

final disadvantage of the separation of racial groups across universities concerns theimportance ofinterracial contactinmediatingstereotypes andpromotingunderstanding andtolerance.

Interracialinteraction generally leads to positive sentiment

(Hpmans

1950),andfostersthecreationofItisimpossibletoidentifytheseparateimpact of each ofthese chamielsonsegregated Blacks'

wellbeing with theavailabledatasets. Instead,thispaper's goalistoproducereliableestimatesofthe

netimpactof

HBCU

attendance. Theresulting"reducedforni"estimates will likelyreflectanumber

ofthechannelsspecified inthissection.

IV.Data Sourcesand

Summary

StatisticsWe

analyzethree large datasets:The

NationalLongitudinalStudy oftheHighSchool Class of1972 (NLS-72), Baccalaureate and

Beyond

Longitudinal Study (B&B), and the College andBeyond

(C&B)

database. Thesedata setshavebeenchosen because oftheenormousamountof information eachcontainsonpre-collegeacademicperformance, familybackground,college entry decisions,perfoiTnance

whilein college,andlater lifeoutcomes.^Throughoutthe analysis, the rich setof pre-collegeandfamily

backgroundvariables are used as conditioning variables to adjust for obsei^vable differences between

HBCU

andnon-HBCU

matriculatesinequationsfor theother variables.We

discusseach ofthesesourcesandpresent

summary

statisticsfromthem.Before proceedingto thismaterial.AppendixTable 1providessome

summary

statisticsonthe894-year historicallyblackcollegesand universities intheUnited States. Foity-nine ofthemareprivate

institutions. Theyarepredominantly locatedintheSouth. Togethertheirundergraduate enrollmentinthe

Fallof2005

was

238,911 andtherewereanadditional37,151 graduatestudents enrolled. Thefourteenhistoricallyblack 2-yearcolleges arenotincludedinthistable.

A.TheNational LongitudinalSurveyoftheHigh SchoolClassof 1972

TheNational Longitudinal Surveyofthe HighSchool Class of 1972(NLS-72) is anationally

representativesampleof 23,451 high schoolseniors in1972. Participants in thesamplewereselectedin

theSpring of 1972,andinasupplemental^sampledrawnin 1973. Thedataincludeabase yearsurvey,

andfollow-up surveysin 1973,1974, 1976, 1979, and 1986.Roughly 1,300 high schoolsareincludedin

thesample,with an average of18studentsperschoolinthe study.

A

widerange ofdataisgatheredonthestudentsinthe study, asdescribedindetailattheNLS-72

website (http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/nls72). There is detailed information on each student's family

environment, parent's education and occupation, socio-economic status, and the pre-college

characteristicsof eachstudent(i.e. high schoolgrades,collegeadmissionscores,andsoon). Thereare also detailed records from post-secondary transcripts, collected in 1984, and high school records.

Two

other data sets collected by the National Center for Education Statistics, the National Educational LongitudinalStudy2000(NELS)andtheBeginningPostsecondaryStudy(BPS),areequippedtoanswersomeofthequestionsposedhere.Unfortunately,however,these datasetsdonot track individualslongenoughaftercollege

Importantforour purposes,a six digit identificationnumber was assignedtoeducationalinstitutionsby

the Federal Interagency Committee on Education (FICE) to, historically, distinguish postsecondary

schoolsthat qualifiedas institutionsof higherlearningfromthose thatdidnot.Thesecodesare cracialin

defining

HBCUs

andensuringthatthisdefinitionisconsistent acrossdatasets.B.Baccalaureate

and Beyond

TheBaccalaureateand

Beyond

LongitudinalStudy(B&B)

isanationally representativesampleof 11,192 degree completersfrom 648 American colleges anduniversities in the 1992-1993 academic

year.

To

identifyarandom sampleof degree completers,B&B

usestheNationalPostsecondary StudentAidStudyas a basis.TheNationalPostsecondary StudentAidStudy isa largenationallyrepresentative

sampleofcollegesanduniversities, students,andparents.

A

considerableamountofdataisgatheredonthestudentsinthestudy, asdescribedindetail atthe

B&B

website http://nces.ed.gov/sui"veys/b&b. It contains detailed information on pre-coUegecharacteristicsof eachstudent, informationabouttheirparents and

home

environment,andfinancialaidinfonnation.Follow-up sui"veyswere administeredin 1994, 1997,and 2003. Thesefollow-up surveys

include informationonemployment andentry intograduate school.

We

focusontheresponsestothe1997sui-vey,whichtakesplaceaftermoststudents areintheworkplace.

We

hadhopedtousethe2003datamore extensively,but

we

foundittobe of generallypoorqualityonthedimensionswe

caredmostabout. For example,

25%

ofthe originalblack respondentsattritedfromthe2003sample,comparedtojust

6%

inthe1997 sample.And,thisattritionwaslargelyfromblack studentsinTWIs.Thereisoneimportantdifferencebetweenthe

B&B

andtheotherdata setswe

employ.TheNLS

and

C&B

begin withsamples ofstudents thatenrolled theirfreshmanyear. TheB&B

samples degreecompleters, which can introduce bias if graduation rates between

HBCUs

andnon-HBCUs

differsubstantially.

Whenever

the results fromthissurvey differwithour other data,we

willbeclearaboutwhetherthisdifferencecanbe accountedforbydifferences insamples.

A

convenientway

tohandlethisisto restrictthesampleinourother datasetstobe of degree completers,which

we

do throughout.C.TheCollege

and Beyond

DatabaseTheCollege and

Beyond

Database contains studentlevel administrative dataonon93,660full-timestudents

who

entered(butdid not necessarilygraduatefrom)thirty-fourcollegesanduniversitiesinthefallof 1951, 1976,and1989.Theseinstitutionalrecordswerelinkedtoan extensive survey conducted

by the

Andrew W.

Mellon Foundation between 1995 and 1997 and to files providedby the CollegeEntranceExaminationBoard andtheHigherEducation ResearchInstitute.Therearefour

HBCUs

inthedataonallfourblackcolleges; the 1989cohortonly includesMorehouseandXavier.''Thefinaldata set consistsof blackstudentsfrom 34collegesanduniversitiesincludingthefourelite

HBCUs;

thesampleconsistsof 2,125studentsin 1976and1,785in1989.

The

C&B

data areremarkablyrich,containinginfoiTnationdrawn fromstudents'applicationsandtranscripts, Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and American College Test

(ACT)

scores, as well asinfonnationonfamilydemographic andsocioeconomicstatus.This informationwasattainedbylinking

the institutional files ofthe thii1y-four colleges and universities with data provided by the College

EntranceExamination Board andtheHigher Education ResearchInstitute. Importantly,the

C&B

surveyincludestheresponsestoa questionnaireadministeredtoallthreecohortsin 1996thatprovidesdetailed

informationonpost-collegelabormarket,lifesatisfaction,andotheroutcomes. Theresponseratetothe

1996 questionnairewas approximately 80%. The College and

Beyond

Survey is described in greaterdetailin

Bowen

andBok

(1998).D.

Summaiy

StatisticsSummary

statisticsforthe variables inour corespecification aredisplayedinTable 1 forblackstudentsinthe three datasetsdescribed above,accordingtowhetheror nottheyattend a

HBCU

orTWI.

Students

who

aremissing dataonrace orwhichcollegethey attendedaredroppedfromthesample.Table1consistsoffive setsof columns.Thefirstcolumnprovides

summary

statisticsforstudentsinthe

NLS-72

whosefirstcollegewasanHBCU

versusTWI,

wherefirstcollegeisdefinedasthefirst4-year college a studentattends.

An

individualwho

attends ajuniorcollege,technical school, or thelikeandthen attends an

HBCU

willbe counted ashaving his firstcollege as anHBCU.

The second columnrestrictsthesampletothose

who

completedabachelor'sdegree,allowingonetomake

directcomparisons withB&B

whosedescriptivestatisticsaredisplayedincolumn3.Columns

4 and5providemeansofthe variables forstudentsintheC&B

databaseforthe1976and1989cohorts, respectively.^Across all our datasets, blacks attending

TWIs

tend to have substantially higher academiccredentials. In theNLS-72,

SAT

andACT

scores of BlacksinTWIs

are roughly 1 standard deviationhigher. Yet,Blacks attending

HBCUs

haveslightlyhigherGPAs

thantheirpeerswho

attendTWIs

(2.86compared to 2.83), suggesting that these students attend less academically challenging high schools.

Students in

HBCUs

are morelikely to attend private high schools. Similartrends are apparent intheB&B,

thoughthedifferencesinacademiccredentials betweenHBCU

studentsandnon-HBCU

students are lesspronounced.A

portionofthedifferencebetweentheNLS-72

andB&B

can be explainedbytheAllforthcomingresultshavebeenrunbyrestrictingthe1976cohorttoMorehouse and Xaviertoensurethatany

differenceswhich emergecannot be explainedbydifferentsamplesinthetwocohorts.

differentsamplerestrictions.

Inthe 1976 and 1989 cohorts of

C&B,

theGPAs

ofBlackstudents inHBCUs

are .73 and.5standarddeviationsless,respectively.

SAT

andACT

scoresofHBCU

students aremorethan1 standarddeviationbehind Blackstudentsin

non-HBCUs.

In these data, studentswho

attendHBCUs

are less likelytohaveattendedaprivatehighschool.

The"Pre-College Personal and Family Background" variablesprovide measures forthe

home

environmentsthat students werereared in. These variables include family income (measuredin 1972

dollars), parental education, orwhether or nota student attendedhigh school in a rural area or the

southern portion ofthe US. The definitionofincome differs slightly between data sets. In NLS-72,

studentswereasked,

"What

istheapproximateincomebeforetaxesofyour parents(orguardian)? Includetaxableand non-taxableincome fromallsources."For

B&B,

we

used familyincomein1991 forstudentsthatweredependents oftheirparentsandthestudent's

own

taxedanduntaxed incomeforstudents thatwerenotdependents.^For

C&B,

familyincomeisderivedfromtheHERI

studentsui"vey.TheCPI-U

wasusedtoconvertallincome measuresto1982-84dollars.

Itisapparentthatthere areimportant observabledifferencesbetweenblacks

who

attendHBCUs

and TWIs.Thesubsequentanalysisusesa varietyofstatisticalapproachesto adjust forthese differences.

Thethirdpanelreportson

many

ofthe outcomevariables.These includewages,majorchoice,whether or not a student received their bachelor's degree, attended graduate school, orobtained a

graduatedegree, andvariablesdesignedtomeasurecollegeexperiencesandjobandlifesatisfaction.In

therawdata,blacks

who

attendHBCUs

tendtomake

lessmoney

than blackswho

attendTWIs,withoneexception;NLS-72.^Theyare also less likely tobeemployedfull-timeandmorelikely tobedissatisfied

withlife.

HBCU

students aremorelikelytomajorinphysicalsciences.Inthetwonationallyrepresentativesamples,blackstudentsat

HBCUs

aremorelikelytoreceiveabachelor'sdegreeandattendgraduate school (though theyarelesslikely tograduate).Blackstudentsin

theelite

HBCUs

aremorelikely tomajorinbiologicalsciences(thisisdriveninlarge partbyXavierwho

hasa storied reputation forpre-medical studies),business, lesslikely toreceiveabachelor'sdegree or

attendgraduateschool,and,inthe1989cohort,less likelytoreport that theircollegeexperience helped

Forstudents

who

weretheirparents'dependentsin 1991,totalfamilytaxedand untaxedincomewasobtained,inorderofpriority,fromthestudent'sfinancial aidapplication, atelephone interviewofparents, atelephone interview ofthe student, thestudent's Pellgrant file,or the student loanfile. Forstudents thatwere nottheir parents' dependent,theinformationwasobtained,inorderofpriority,fromthe financial aid application, the student'sphone

interview,thestudent'sPellgrantfile,orthestudentloanfile.

'IntheNLS-72,theaverage hourlywage

is$12.82 ($14.46)for

HBCU

attendees (graduates)and$10.55 ($11. 38)for

TWI

attendees(graduates). Themeanofthe naturallogarithmof hourlywagesisabout5%

(12%)higherforTWI

attendees(graduates). Thedifferenceintherankof wagesacrossHBCUs

andTWIsisdueto a singleHBCU

respondent with an average hourlywageof$494. Theinfluenceofthisobsei'vadonontheTable1 entriesisalso evidentinthelargerstandard deviation ofwagesamong

HBCU

attendeesandgraduates. SeetheDataAppendixfor detailsonthesampleselectionndes.develop anabilitytogetalong withindividualsofother races.

Thefinalpanel in Table 1 provides thetotal

number

ofHBCU

andTWl

observationsin eachsample. Italsoprovides

some

detailsontheincompleteobservations.As

asolutiontothe largenumberof observations withatleastone missingvariable,

we

turnalloftheexplanatoryvariables intoaseriesofindicator variablesbased onranges ofthe values ofthese variablesand includeseparate indicators for

missing responses toeachvariable. The bottompanel alsoreportsonthe

number

of observations withmissing

wage

information. Thesubsequentanalysisimplementsa standardselectioncorrectionapproachtoaccountforthesecases

(Heckman

1979).V.

The

Causesand ConsequencesofAttendingHBCUs

intheNLS

andB&B

DataFiles A. The Causes ofAttendingHBCUs

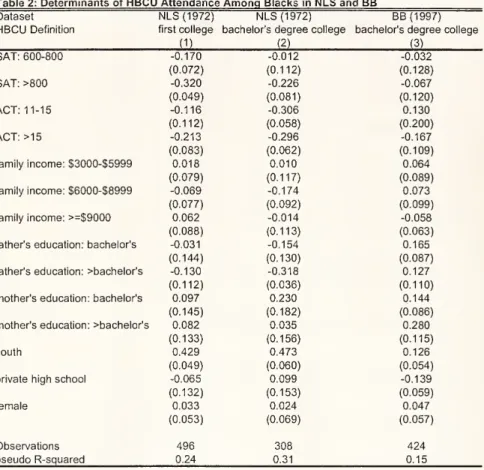

Table2presentsa seriesofestimatesofthedetenninantsof

HBCU

attendance.Thespecificationsestimatedareoftheform:

(1)

HBCU,

=

a

+

pX.''""^+

yX.''^^-^''"^^^+

e,,

where

HBCU

isadichotomousvariable thatequalsoneifthestudent attendsanHBCU

andzeroifnot,X

°' " denotes an aiTay ofvariables which proxy for a student's

home

environment, andX/™

^°''^''denotes pre-college characteristics of each student. In all instances, weighted Probit

regressionsareusedandthe coefficientsreportedaremarginaleffectsevaluatedatthesamplemean.The

weightsare thesampleweightsinthe relevant datafile.

The

interpretationofanycoefficientisthe effectofthatcoefficient relative to theomitted category

when

allother variables areheldattheirsample mean.The

home

environment variables thatwe

include are family income, mother and father'seducation,andwhetherornotastudent livesintheSouth.Familyincome,measuredin 1972dollars,is

dividedinto4categories:<$3,000,S3000

-

$6000,$6000-$9000,and$9000+basedonasurvey questiondescribedintheprevioussection.Parentaleducation(motherandfather,independently)ispartitioned into

threecategorical variables: lessthan aBachelor's degree, aBachelor's degree,and greater. Whetheror

notastudent livesintheSouthisa

dummy

variable thattakesonthevariableofoneiftheanswerisyes.Pre-collegecharacteristicsinclude

SAT

andACT

scores,high schoolGPA,

and whetherornot astudentattendeda privatehigh school.

Combined

SAT

scoresaredividedintolessthan 600,between600-800,andgreaterthan800.

ACT

scoresaredividedupsimilarly, lessthan11,between11 and15,andgreaterthan15.Highschool

GPA

ismeasured onafour pointscaleandisdividedinto lessthan2.5, 2.5 to3.5,andgreaterthan3.5.

We

alsoincludeanindicator forwhethertherespondentisfemale.In 1972,students

who

attendHBCUs

have lowerSAT

andACT

scoresand are more likelytoprobabilityofattendingan

HBCU

by 32%. Similarly,moving fromanACT

score ofless than 11 toascoreofmorethan 15 reducesthelikelihoodof attending an

HBCU

by21%. Studentswho

liveintheSouthare

43%

more likely to attendHBCUs,

holding all elseconstant. Family income and parentaleducation are not statistically related to

HBCU

attendance once our other covariates are taken intoaccount.

In the 1990s,thingschange. Standardizedtestscores arenolongersuchapowerfulpredictorof

HBCU

attendance.Parentswithmoreeducationaremorelikely tohavechildrenwho

attendHBCUs.

Allelse equal, a studentwhose motherhas morethan abachelor'sdegreeis28%)morelikely toattendan

HBCU.

This is notsurprising, as these institutions have a long histoi-y ofloyal alumni and familiallegacies(Drewiy and

Doermann

2001). ResidingintheSouth continuestobe an importantdeteraiinantofcollege choice, though the magnitude ofthe coefficient is roughly a fourth ofthe magnitude in the

seventies.Privatehighschoolisnegativelycon'elatedwith

HBCU

attendance.Therearemarked differencesbetweenthedeterminantsof

HBCU

attendancein the 1970sand1990s. The most obvious explanation ofthese differences is that conditioning on degree completion

selects forhighability studentsand

among

this set,differencesbetweenthetwoperiods willdisappear.Comparing colmnns2and3intable2

we

canmake

directcomparisonsbetweenthe70sandthe 90s;eachsampleconsistsonlyofdegi^eecompleters.

Intuition suggests that as resistance to black attendance at

TWIs

faded and the need forsegregated schoolingdeclines,thosewiththehighest opportunitycostof such schoolingwilloptoutand

choosemoretiaditionaluniversities. Inotherwords,itmightbe reasonabletoexpecta"brain drain"from

HBCUs.

Yet, the datashow

the opposite to be true.Lower

academic credentials are not as highlypredictiveof

HBCU

attendanceinthe1990sasthe1970s.Studentswith highereducated parentsaremorelikely toattend

HBCUs

inthe1990sandhigheracademiccredentials arenotasstrongapredictorofnon-HBCU

attendance.This providesevidenceofa selectionoftalentedBlackstudents intoHBCUs

inrecent years.B.EconometricApproachtoEstimatingtheConsequences ofAttending

HBCUs

In the absence of a randomized experiment or a credible instrumental variable for

HBCU

attendance,

we

implementfourstatisticalapproachesto adjustforpre-collegedifferencesbetweenHBCU

and

TWI

attendees. This subsectiondetailsthese strategies.Thefirstand simplestmodel

we

estimateisa linear specificationofthefonn:(2) outcome,

=

p^+

pX

.""'"""

+ oXr"""'"' +

5HBCU

+

f,.

Inallinstances, theestimationisdone usingweightedleastsquares, withweightscoiTcspondingtothe

sample weights providedinthe data. Equation (2)is a simple and easily inteipretable

way

to obtainestimatesofthe effectof

HBCU

attendanceonoutcomes, butitreliesona linearmodeltocontrol for the covariates Xj"""""^ and ^.'"^-"'^s^_ Thismay

be unappealing since their true functional form isunknown.

As

a solution,we

matchHBCU

andTWI

students with similar predicted probabilities orpropensity scores(p-scores)of

HBCU

attendance(Rosenbaum and Rubin1983).^ Theestimated p-scorescompress themulti-dimensional vectorofcovariates intoanindex. Theadvantages ofthe propensity

score approach aretwofold. First, itisa feasiblemethodtocontrol forobservables inamoreflexible

manner than is possible with linear regression. Second, it provides an opportunity to focus the

comparisons ofoutcomesbetweenthe

HBCU

andTWI

attendeesamong

thosewithsimilar distributionsofthe obsei'vables. Since

we

modelallofthecovariateswithindicatorvariablestheformer advantageisnotsocompellingin thissetting,butthelatterisa real asset here. Finally,itisimportantto emphasize

thatjust as with linear regression, the identifying assumptionis thatassignmentto the treatment(i.e.,

HBCU

attendance) is associated only with observable pre-period variables. This is often called theignorable treatmentassignment assumptionor selectiononobservables.

We

implement thep-score matching strategy inthree steps. First, the estimated p-scores areobtainedbyfittingprobitregressionsfor

HBCU

attendance(identical toequation1 above),using X!""^"""and Xj'^'^'^"

'^^'^

as explanatoiy variables. In other words,

we

try to replicate the average student'sselection rulewith theobsei"ved covariates.

We

then conducttwo teststo ensurethatthep-scores are suitable.For bothtests,we

dividethe sampleinto quintilesbasedontheirp-scores. In thefirsttest,we

assesswhethertheestimated p-scoresareequal acrossthe

HBCU

andTWI

studentswithinquintiles. In the secondtest,we

examine whetherthemeansofthecovariates areequalfor thetwosetsofstudentswithineachquintile. Ifthe nullhypothesisofequalityisrejected for eithertest,

we

dividethe qunitilesand/orestimatea richerprobitmodel byincludinghigher order termsandinteractions.' Oncethe nullis

acceptedforbothtests,

we

proceedtothenextstep.Second,the"treatmenteffecfforagivenoutcomeiscalculatedby comparingthe differencein

theoutcome between

HBCU

andTWI

studentswithsimilaror"matched"valuesofthep-score.We

dothis intwoways. Thefirstcalculates atreatmenteffect foreach

HBCU

student forwhichthereisatleastone

TWI

studentwith an estimated p-score within 0.10 oftheHBCU

student's p-score. Incaseswheremultiple studentshavep-scoreswithin0.10,

we

take thesimpleaverageofoutcomeacrossallofthesestudents.Further,thismatchingisdonewithreplacement sothat individual

TWI

studentscanbeusedasAn

alternativeistomatchonasingle (orpossiblyafew)crucial Govariate(s).SeeAngristandLavy(1998)orRubin(1977)for applications.

'SeeDehejiaandWahba(2002)andRosenbaum(1984)formoredetailsonhowtoimplementthepropensity score

method.

controls formultiple

HBCU

students. Thesecondmatching approach usesalloftheTWI

students tofomi acontrol for each

HBCU

student but in calculating the averageamong

themwe

use akernelweighted average,wheretheweightisinversely proportionaltothe distanceto the

HBCU

student'sp-score.

We

useaGaussian kernel withabandwidthof0.10.Third,asingletreatment effectisestimatedbyaveragingthetreatmenteffectsacrossall

HBCU

students forwhichtherewasatleastonesuitablematch. Thisapproach hasthedesirablepropertythatit

focusesthecomparisonswherethereisoverlapinthe distributionof propensityscores

among

theHBCU

and

TWI

studentssothese students are"similar.""We

also implementtwoothereconometric approachestoaccountforpotentialselection issues.First,

we

estimateprobits forwhetherthewage

variableismissingonthesample ofobsei'vationswithmissingand non-missing

wage

values.We

then includetheinverseMill's ratiofromthese probits inequation(2) toaccountforthe possibility thatwages arenotmissingatrandom

(Heckman

1979). Thisprocedure is identifiedfrom afunctionalformassumption, since

we

areunaware ofa validexclusionrestrictionin thissetting.

Second,the available data sets

may

not includemeasuresofsome

attributes (e.g., strength ofessay,motivation,and teacherrecommendations)thatpersuadeadmissions committeestoselectcertain applicants foradmissionthatarealsorewardedinthelabormarket. Further,these attributes

may

differacross

HBCU

andTWI

students.Theleastsquaresand propensityscoreapproachesrelyon"selectiononobservables"assumptionsandwillproduce biasedestimatesin thiscase.

To

confrontthissourceofmisspecification,we

implementavariantofthemethodpioneeredbyDaleandKrueger(2002)thatmatchesstudentsbasedonthecolleges wheretheywereaccepted. This

approach can onlybeimplementedwiththe

NLS

datafile,asB&B

does not contain informationonthesetsofcollegestowhichindividuals areadmitted.

We

operationalize theDaleandKruegerapproachbydetenniningthe identityofthecolleges thatacceptedeachstudent.

Among

thecollegeswheretheywereaccepted,

we

find themidpoint ofthe 25th-75thpercentileSAT

range reportedinUS

Nev.'s&

WorldReport(2006).

We

use currentSAT

scores since scoresfrom 1972 are unavailable. Forcolleges thatreportonly

ACT

scores,we

usean equivalencescaletoconverttoSAT

scores.For each student,

we

recordthe highestmidpointSAT

score ofany college that acceptedthestudent.

We

dividethestudents intofourgroupsbyquartilesoftheschoolwiththehighestmidpointSAT

among

the schoolswhere they wereadmitted.We

then include separate indicators for each ofthesegroups inequation (2). This approachmitigates the impact of any confounding due tocharacteristics

'"

SeeDehejiaand

Wahba

(2002)andHeckman,Ichimura,andTodd(1998)onpropensity score algorithms. " Ifthereare heterogeneous treatment effects, thisstrategy produces an estimate ofthe average effectofthe"treatmentonthe treated".

obsei-vable to admissions officers that are notmeasiu'ed in the dataset. Specifically, the identifying

assumptionisthat afteradjustmentfor theavailable covariates, thedecisiontoattend a

HBCU

versus anon-HBCU

withina quartileis"ignorable" ororthogonaltounobserved determinants of outcomes. See DaleandKrueger(2002)for amoredetaileddiscussionofthisapproach.Finally,

we

note thatwe

considered a number of candidate instrumental variables, such as distance to a student's nearestHBCU,

residingintheSouth,or theclosingofHBCUs,

butin allcaseswe

were unconvincedthattheexclusionrestrictionwasvalid or theinstruments werenotpowerfulenoughforthe relativelysmallsamples inthe available datafiles. Withapproximately300 observations,itis very difficult to constmct an instmment with apowerful first stage. Consequently, thorny issues of

selection

may

stillremain.C.EstimatesoftheConsequences ofAttending

HBCUs

DistributionofEstimated P-Scores. Figures1 and2 presentseparatekerneldensity plotsofthe

estimated propensityscores forblackstudents thatreceiveddegreesfrom

HBCUs

andTWIs

with theNLS

andB&B

datafiles,respecdvely.To

obtainthese figures,weightedprobitswereestimatedonthesetofstudents

who

completedtheirbachelor'sdegreeatanHBCU

orTWI.InFigure1,whichisbasedonthe

NLS

data,it is evidentthat themean

propensity scorediffers across thepopulations, but there issubstandal overlapinthe distributions,exceptatp-scoresexceeding roughly0.9. Thedistributionsof

p-scoresinthe

B&B

aremoresimilarthroughoutabroader range ofthe p-score. However,there aren'tanyTWI

students with p-scores greater than about 0.8. Thus, it will be difficult to obtain meaningfulcomparisonsforthe relativelysmall subsetof

HBCU

studentswith p-scoresinthisrange.Wage

Outcomes. Table 3 presents results ofthe effect of attending aHBCU

on the naturallogarithm ofwages from the four approachesinthe six columns. The estimated standard errors are

reportedinparenthesesbelowthepoint estimatefor the

HBCU

indicator. In theNLS

entriesinPanelsA

andB,thestandardeiTorsallowforclustering

among

observationsfromstudents thatattendedthesamehigh school (exceptin column 5). In Panel A,the treatment ismatriculationat a

HBCU,

whileitisgraduationfroma

HBCU

inPanel B. FortheB&B

entries inPanel C,we

reportstandarden-ors thatallow for unspecified heteroskedasticity in the variance-covariance matrix. Underneath the standard

eiTors,

we

report the R-squaredstatistic,aswellas thenumber

ofstudentsinHBCUs

andTWIs

inthe relevantsample. FortheNLS,

wagesaremeasuredin 1986-

fourteen yearsafterhigh school graduationand roughly 10 yearsafterobtaining a bachelor'sdegree. In the

B&B,

wagesare in 1997,fiveyearsaftercompletionofthebachelor's degree.

Column

1reports themean

differenceinlabormarketwagesfor individualswho

attendHBCUs,

without adjustment for any controls. In the

NLS,

HBCU

students earn roughly5%

lesswhen

thetreatment isthefirstcollege attendedand 11.5%

when

itisreceiptofa bachelor'sdegree. Neither ofthese estimates is statisticallydifferent from zero atconventional levels. The

B&B

estimate fromthe1990sindicates that

HBCU

graduates earn16.6%lessthanTWI

graduates. Recall,Table1 demonstratedthat on observable dimensions

HBCU

students have lesser academic credentials than theirTWI

counterparts(especiallyintheNLS),sotheserawgapsare likely

downward

biased.Column

2reports the resultsfromestimatingequation(2).Theadjustmentfortheacademicandhome

environmentcontrolschangesthe resultsintheNLS

dramatically.'"Thewage

benefitof attendingaHBCU

inthe1970sis11.1%when

HBCU

statusisbasedonthefirstcollegeattendedand6.0%when

itisdefinedasreceivingabachelor'sdegree. ThefoiTnerestimateismarginallysignificant,whilethelatter

hasan associatedt-statisticlessthan1.'^ In the

B&B,

however,thewage

effect forattendingHBCUs

is-13.8%)andthe nullof zerowouldberejectedwith conventionalcriterion.'''

The

nexttwocolumnsreportontheimplementationofthep-scoremethodtotestthe sensitivityofthese resultsto the linearmodel.

Column

3 uses kernel matching, while column4relies on radiusmatching.'^ Standard errors for both matching estimates were bootstrapped (200 iterations), with

propensity scoresrecomputedforeach bootstrap sample. Further, thep-scorematching estimatesarenot

weighted withthesampleweights.

Thep-score estimates are remarkablysimilar tothose from the linearregressionin column 2.

This finding shouldn't be teixibly sui"prising because equation (2) models the covariates flexibly,

neverthelessitisreassuringthatfunctionalfomiissuesdon'tappear importantin thissetting.

Column

5presentsestimatesthatare selectioncorrectedformissingwagesand adjustedforthefull setofcovariates. It seemsplausible that

HBCU

attendanceiscoiTelatedwithselectivewithdrawalfromthelabor force. Thispossibilityisnotsupportedbythedata asthisapproachproduces unimportant

changeintheestimatedimpact of

HBCUs

onwages.''^

A

similar resultwas foundinConstantine (1995).

'^Resultsaresimilarifone implementsa "fractionmethod,"using individualtranscripts tocalculate the fractionof

astudent'scollegeexperiencethatwasspentatan

HBCU.

'^Inthemost

recentwaveofthe

B&B

(B&B

2003)thereisnowagegapbetweenHBCU

studentsandnon-HBCU

students.Unfortunately,

53%

oftheHBCU

sampledoes nothavevalidwagesinthelatersurvey(someareinthe survey and unemployed while others were dropped completely).HBCU

graduates have a 9.6% higherunemployment rate, and median regression techniques provide identical results to the 1997 wave. Thus,

we

concentrateonthe earlierwavewithmore completedata.

''

Observations with estimated p-scoresthatare notstrictly between and 1 are dropped. Further, welose 7

observationsinthe

NLS

whenthetreatmentisfirstcollegeattendedand21whenthetreatmentisdegreecollege,and21observationsinthe

B&B

whenimplementingtheradiusmatchingestimatorsduetooutliersthatdidnothavematchesintherelevant range.

"

We

alsoassessedtheimpact of labormarketdropoutsonour estimates withasimple re-weightedlinearregressionandmedianregression. In thefirstapproach,weestimateaprobitofwhetherornot

we

havevalidwages onallofthecovariatesinTable2.

We

then multiplied thesamplingweightbytheinverseof the predicted probabilityintheprobit togetnewweights. Linear regressionsarethen esrimatedwith thesenewweights. Thisapproach led to

remarkably similar conclusions as the selection correction approach. Median regressions were estimated by

Column

6implementsthecolumn2specificationbut addscontrols forthe"best"schoolthatthestudentwasadmittedto inordertoaccountforthe richerdataavailable toadmissionscommittees (Dale

and Krueger2002). Specifically,

we

includeindicators for the threehighestquartilesofSAT

scoresofthebestschoolthatthestudentwasadmittedto,leavingthelowestquartile as theexcluded group. This

methodis onlypossible in the

NLS

dataand inthis sampleitdoubles estimatedimpact of attendingaHBCU

to 22.5%. Specifically, this approach suggeststhat the gains fromHBCU

attendancemay

belarger than indicated by the other methods. However, the estimate's imprecision makes definitive

conclusionsunwarranted.

Additionally,

we

conductedanumber

oftests forwhethertherewasheterogeneityinthe returnstoattendinga

HBCU,

whicharereportedinAppendixTable2.We

assessedwhetherreturns differedwith students'

home

region (i.e., South versus North), their estimated propensity score,SAT

Score, parental education,andgender. In general,thereisn'tsubstantialevidence of heterogeneity acrossthesesubsamples ofstudents. Theloneexception isthatthe returnstoattending a

HBCU

appear higherforblack

women

thanforblackmen

intheNLS

sample. It isalsoimmediately evidentthatsubdividingthesampleistoodemandingofthedataasthestandarderrors in thesubsamplesare

much

larger.Overall, these resultssuggestthatattendingan

HBCU

conferredremarkable advantageson itsstudents in the 1970s. Conventional estimates of the average return to college are

10%

per year(Heckman, Lochner and

Todd

2003). Attending aHBCU

versus aTWI

in the 1970s was roughlyequivalent to one more year ofschooling. In contrast, more recent

HBCU

attendees appear to besuffering awagepenalty. Ifthepointestimates aretakenliterally,thereisnearly a

-25%

swing inthe relativereturnofHBCU

attendanceinjusttwodecades.Non-wage

outcomes. Thus farwe

have concentrated onthe effect of attendingaHBCU

on a singleoutcome: labormarketwages.Thevalueof attendingHBCUs,

however,likelyextends wellpastlabormarketconsiderations.Theconventional

wisdom

isthatthese institutionsinstillconfidenceintheirstudents,a senseofresponsibility,andprovideenvironmentsfreeof racismanddiscriminationthatallow

for greaterpersonal development. Such environmentsare likely to have

many

benefits beyond thosecapturedinwages.

Table 4 explores the effect of attending

HBCUS

on a number ofoutcomes, including theprobability offull-timeemployment, measures oflifesatisfaction, andaseries ofacademicoutcomes.

Thesewiderangingoutcomeswerechosen because oftheireconomic andsocialrelevanceaswellas their

comparability across datasets. The academic outcomes indexis the first principal component ofthe

dummy

variables for majoring in business, majoring in physical science/mathematics/computerimputingzerostoallmissingwageobservations. Qualitativeconclusionswere thesame,thoughthecoefficients

weresmallerasexpected.

science/engineering, majoring in biological science/liealth, receiving a bachelor's degree, attending

graduateschool,andreceiving agraduatedegree. Thecoefficientsreportedinthe table are fromkernel

matchingestimatesandtheirassociated bootstrapped standardeiTors. Inallcases,weightedleastsquares

confrnntheseresults.

The moststriking finding fromtheseoutcomes isthat

HBCU

matriculationisassociatedwith anearly

10%

increaseintheprobabilityof receivingabachelor'sdegree. Itisevidentthat partofthewage

gaininthe1970sisduetotheincreasedprobabilityof graduatingfromcollege. Thereis

some

evidencethatstudents

who

attendHBCUS

aremodestlymorelikely tomajorinphysicalsciences. Interestingly,HBCU

andTWI

matriculatesreport similardegreesoflifesatisfaction.Therearenegligible effectsonallother outcomes.

VI.

A

FocusedLook

attheMost

EliteHBCUs

There issubstantial qualityvariation

among

theset of 89 4-yearHBCUs,

aswell asamong

theTWIs.

To

thispoint,we

haveanalyzedtheNLS

andB&B,

whichare nationallyrepresentative datafilesthatincludethefullspectrumof

HBCUs

andTWIs

fromthe qualitycontinuum.Inthissection,we

takeamore focused look at four of the most elite

HBCUs:

Morehouse, Xavier, Spellman, and Howard.(Importantly, the 1989datasetdoes not include infonnation on Spellman and

Howard

students.)One

limitationofthis exercise isthatduetothe

C&B's

sampling approach,thesefourHBCUs

can only becomparedtothethirtyselective

TWIs

inthesample.Table5reportsonthedetenninantsof attendanceforelite

HBCUs

forthe 1976and 1989 cohortsof

C&B

fromestimatingequationsidenticaltothoseinTable 2."Column

(1)isasampleofindividualsin all4

HBCUs,

column(2)dropsHoward

andSpelmansothatwe

canmake

directcomparisons withthe1989 cohortwhich is displayedin column (3). Thepatternsacrossthe columns are quite similar. The

parametersonthestandardizedtestscores are themostnotableresults.Evaluatedatthesamplemean,the

difference betweena

SAT

score oflessthan600and aSAT

scoreabove 800impliesa40.1%decrease(colunm2)inthelikelihoodof attending anelite

HBCU

inthe1976 cohort anda63.1%decrease(column3)in the 1989cohort.

ACT

scoreshave a similar effect onHBCU

attendance.Mother's education ispositivelyassociatedwith

HBCU

attendancein 1989. Afteradjustmentfor theacademiccharacteristics, the incomevariables are not reliable predictorsofeliteHBCU

attendance. Residing in the southernportion ofthe United States continues to be a strongpredictor of

HBCU

attendance; increasing theprobabilityof attendancebyroughly 40%.'^

'^Throughout

the

C&B

analysis,thetreatmentisdefinedasenrollmentataHBCU,

notgraduationfromone. Forconsistency withtheothertables,

we

refer tothetreatmentas"firstcollege",althoughduetotheC&B'ssamplingschemeitispossible (but unlikely)that arespondentwasinitiallyenrolledata differentcollege oruniversity.

'*The

Figures3 and4plotthe distributionsoftheestimated propensity scoresforthe

HBCU

andTWI

attendeesfromthe 1976 and 1989

C&B

classes, respectively.Howard

andSpelman were dropped fromthis analysisto

make

thesamplesconsistent. Itisapparentthatthereisn'tsubstantialoverlapacross thetwodistributionsineither year, especiallyin1989. Thisfindingconfirmstheimpressionfromtheprobit

resultsthattheacademiccredentialsofthese students differinimportantways.

The pooroverlapofthe distributionsposes challengesfortheoutcomesanalysis. Forexample,in

thepropensityscore exercisewhere

we

require theTWI

students tohave p-scores within0.1 oftheHBCU

student, itis apparentthat

we

willrelyon asmall subset ofthe data. Inthis subsetofthe data, the selectiononobservablesassumptionmay

beespeciallyunlikelytobevalid.On

theotherhand,we

can useleastsquaresfunctional forniassumptionsto infercounterfactualsinpartsofthe distributionwherethere is littlesupport. Neitherapproach isespecially appealing, which underscores thedifficulties of

infeiTingtheimpact of

HBCU

matriculationin thissample.Consequently,the forthcoming resuhs shouldbeinterpretedwiththeseimportant caveatsinmind.

We

now

turn toan exploration ofthe effectof attendingeliteHBCUs

onlabormarket outcomes,measuresoflifesatisfaction,andacademic outcomes fromthe1976 and1989

C&B.

One

majorbenefitofthe

C&B

database is the availability of detailed questions about life outcomes, beliefs, collegeexperiences, labormarket outcomes and experiences, politicaland civicengagement, and more.These

rich questions can helptoshedlightonthe overall experience ofstudentsattending

HBCUs

andnon-HBCUs.

For both cohorts, data on the majority ofoutcomes was obtained in 1995, 15 years aftergraduationforthe earlycohortand2yearsaftergraduationforthelatercohort,thoughsomedatasuchas

wages in the 1989 cohort were collected in 1996. Individuals without valid

wage

obsei"vations aredropped fromthesample.

Becausethenumberofpotentialdependentvariablesin

C&B

issonumerous,we

construct five indicestobetterunderstandtheexperiencesofHBCU

studentsalongthefollowingdimensions:objectiveacademic, subjectiveacademic, labormarket, leadershipandlifestyle, andsocial interactions. Thedata

appendix describesthe specificquestionsusedto

make

upthese indices.Eachindexisobtainedbytakingthefirstprincipalcomponentofthe setofvariablesdescribed.Thisapproach hastwo main advantages.

First,principalcomponentsanalysisreducesthedimensionality of problemsbyextracting theportionofa setofvariables thatexplain themost variance withinthe set.Second, itensuresthatallvariables are

measured onthesamescale. Thecostisthatthe result'smeaningisn'ttransparentand cannoteasilybe

appliedtodifferent settings.

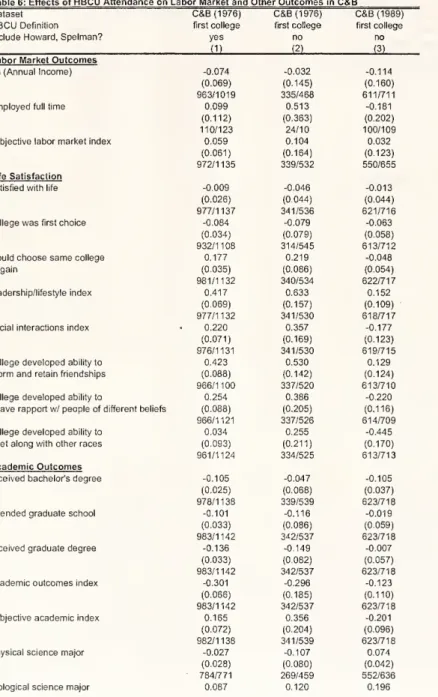

Table 6reportsthe resultsof estimatingthe effectof

HBCU

attendanceon oursetofwage andnon-wage outcomes fromkernelmatching,whichcanbecomparedto theresults incolumn3 of Tables3

the1989sample.

and4.

Column

1 includesallfourHBCUs

inthe 1976 sample.Column

2also reports resultsfromthe1976 samplebut only includes students

who

attendedMorehouse and Xaviertofacilitatecomparisons withthe1989cohort,whoseresultsarereportedincolumn3.Inthe 1976cohort,

HBCUs

graduateswere9%

morelikely tomajorinthe biologicalsciencesand 11.1% morelikely tomajorinbusiness,but

10%

less likely to attendgraduate schooland,conditionalonattending, 13.6%less likely to receiveadegree.

On

objectiveacademicoutcomes,HBCU

students are significantly negative, though their subjective view ofthe academic experience is quite positive.Leadershipand lifestylecomponentsofthe

HBCU

experienceare large, whichisconsistentwithmuch

thathas been written on these institutions (Drewey and

Doennan

2001). Social interactions are alsostatisticallysignificantandsubstantively large.Thelabormarket experiencesare positive,butnegligible.

Studentsdonotseemtopossessa particular taste forsegregation, as

HBCU

graduatesarenomorelikelyto live inmoreracially

homogenous

zipcodes.And,HBCU

graduatesarenomorelikelytobeengagedinpolitical, religious, civil rights, social service, or philanthropicactivities. Theclearestevidence ofthe

importance of

HBCUs

isthat,controlling forallother factors,HBCU

students are 18%

more likelytoreporttheywouldchoosethesamecollege again.

The

1989 cohortreports differentexperiences.Studentsaremorelikely tomajorinphysicalandbiologicalsciencesandbusiness.Studentscontinuetobenefitfromleadershipandlifestylecomponentsof

HBCUs,

butthemagnitudesofthese effects are lessthan one-fourthoftheirpreviouslevels.Many

oftheotherpositiveelements turnnegativeinthemorerecent cohort.Theobjectiveandsubjectiveacademic

outcomesarenegativeand

HBCU

matriculates are10%

lesslikely toreceive a bachelor'sdegree.Thesocial interactions index, which was positive in the 1976 cohort, tiuTis sharply negative in the 1989

cohort.Thetabledemonstratesthatthisdeclineisalso substantialinthreeofthevariables that areusedto

constmcttheindexin 1976and 1989.Thelabormarketexperiences ofthelatercohortareevenmore

negative,andtheyseemto havea taste forsegregation.

HBCU

attendanceisassociatedwithliving inazipcodethathas a

16%

higherfractionofblacks.Most

telling,HBCU

students arelesslikelythannon-HBCU

students to report they would choose the same college again, although the difference isn't statisticallysignificant.Interestingly,

HBCU

studentsin the latercohortare significantly more likelytobe engaged inactivities which are associatedwith civic consciousness. This

may

partly explain the divergence in19 wages.

VII.Reconciling the Differencesbetweenthe1970sand1990s

A.AssessingtheDifferencebetweenthe1970s

and

1990sResults"

We

are grateful toLaniGunierforpointing outthispossibility.Panel

A

of Table 7summarizesthe difference inthe results betweenthe 1970s and 1990s. Itreportsregressionresultsfor fiveofthekeydependentvariablesexaminedabove.

The

differenceisthatwe

usethestacked1970 and 1990datasets toestimate thefollowingequation:(3) outcome!,= Po+y,X/"^=""

+

a, x,r-'°"'<''+

X l(HBCUi,)+

51(1990,,)+ei(HBCUi,)-l(1990i,)+Si,,

wheretheisubscriptindexesanindividualandthetsubscriptrevealswhethertheobservationisfroma

1970sor1990scollege student. Theparametervectorsy and a havetsubscripts indicating thattheyare

allowedtodifferfor 1970s and 1990scollege attendees. Theequationalsoincludesseparate intercepts

forattendinga

HBCU

and whethertheobservationisfroma1990s collegeattendee. Theparameter ofinterestis 9,whichisassociated withthe interactionbetweenthe

HBCU

indicatorandtheindicator foranobservation from the 1990s. This parameter is a difference in differences (DD) estimate of

HBCU

attendanceandisequaltothe differenceofthecross-sectional

HBCU

estimates(e.g.,column2inTable3).^"

Incolumn(1),thedependentvariableisthenaturallogarithmof wages. Forthisregression, the nationally representative

NLS

andB&B

data files areused.The

otherseven dependentvariables aretaken from the 1976and 1989

C&B

samples, which focused on asubsetofeliteHBCUs

andTWIs.Howard

and Spellmanattendeesaredroppedfi-omthesample,just as incolumn(2)ofTable6.The

results summarize the change in the relative returns toHBCU

attendance over the twodecades. Thefirstfour"objective"outcomes(i.e.,thosewherea higher value ofthedependentvariable

wouldbe considereda positive)suggestthatthereturnsto

HBCU

attendance havedeclined. Specifically,thepoint estimatessuggest a

20%

declineinwages,a13%

deplineinthe fractionofstudentswho

wouldattend thesamecollegeagain, andsubstantialdeclinesintheleadershipandsocialinteractions indices.

The

other three"objective" outcomes, which measure political participation, social/civic sei-vice, anddonationsto national charities, all

show

anincrease betweenthetwoC&B

classes. Thenon-objectivemeasure indicates that

HBCU

attendeesbecame

less likely to live inintegratedneighborhoods. It isnoteworthythatallofthese estimates areeconomicallyandstatisticallysignificant.

B.RobustnessoftheResultthat

HBCUs

'Performance Worsened betweenthe1970sand

1990sThis subsectionreportsonsomechecksthataimtoexploretherobustnessofthebasic result that

the economic returns to attending a

HBCU

declined.Many

obvious explanationsfail to explainthe differences.We

have ensured,throughthe useof Federal Interagency Committee on Educationcodes, thatthe definitionofHBCUs

isconsistent across datasetsand overtime.Moreover,theaddifionofmore^^The

C&B

results arenotidentical tothedifferencebetweenthe 1989 and 1976resultsinTable 6 becausethat tablereportsonthekernelmatchingresults,while Table7 reliesonleastsquaresadjustmentforthecovariates.