Empty Photographic Frames

Punctuating the Narrative

Nancy Pedri

Abstract

In multimodal narratives, the frame is an important, powerful punctuation mark: a mark that not only announces a strong pause and a change in storytelling modes and reading practices, but also renders conscious the imaginative workings of readers. It is this last point – the frame as punctuation mark that paves a passage from reading as directed subconscious to reading as open conscious seeing - that my paper explores. Introducing a stark contrast to the verbal prose in which it is embedded, the frame is a graphic mark that demands attention. It disrupts the narrative flow, intersecting and breaking the seamlessness of the verbal telling and renders less operative the directive or guiding function of its linguistic pointers. It does so to instigate parallel tellings characterized by significantly fewer narrative constraints than those imposed on readers by verbal storytelling. The frame, then, is not simply a matter of style. On the contrary, it is that graphic mark that bridges a structured, guided, directed telling and reading and a surprisingly unpredictable telling and a highly self-reflexive reading.

Résumé

Dans les narrations multimodales, le cadre photographique est un signe de ponctuation capital: il marque non seulement une pause importante et un changement de mode de narration et de lecture, mais il permet aux lecteurs d’être plus conscients de leur travail d’imagination. C’est ce dernier point que j’explore ici: le cadre photographique en tant que signe de ponctuation qui fait passer d’une lecture non encore consciente à une lecture comme vision consciente. Dans la mesure où il établit une rupture dans la prose qui l’enchâsse, le cadre photographique nécessite une attention soutenue. Il perturbe le flux narratif, dont il casse la nature unie tout en embarrassant le rôle directeur des unités linguistiques. Le cadre photographique introduit des narrations parallèles, moins contraignantes que les signes qu’on trouve dans les narrations verbales. C’est dire que le cadre photographique n’est pas seulement une question de style. Il est au contraire un élément qui sert de trait d’union entre une manière de raconter qui guide et dirige le lecteur et une manière de raconter plus imprévisible, doublée d’une manière de lire plus réfléchie.

Keywords

John Berger; Frame; Jean Mohr; Michael Ondaatje; Photograph; Punctuation; Reader; Reading practices; Janet Williamson.

There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer. Ansel Adams

All images are in an important way held within the boundaries of frames. A canvas serves to delimit the borders of a painting, a billboard’s steel enclosure encircles a particular advertisement as do the contours of a magazine’s glossy pages, and the parameters of a sheet of parchment contains and delimits the map’s universe. And, of course, no photograph is free of the frame. Like paintings, advertisements or maps, the photograph as object has borders, borders that supposedly delineate where art begins and reality ends. In its most basic understanding, the frame is first and foremost the edge of the photograph as object, its material, tangible boundary that separates the inside from the outside, the recorded from the not recorded, the visible from the invisible.

Early semiotic theorists of the frame emphasized its function as one that shapes the image, defining it as “a finding and focusing device” (Schapiro 227) that “interacts with the image as a structuring (organizing) agency” (Marin 778).1 Frames not only make the image visible, but also render

it more visible in certain ways (Maynard 31-32). The parergon effects of the frame – “how it isolates the painting from its background, and both separates and unifies it, highlighting the autonomy of a work and designating it as such” (Louvel, Poetics 82) – has not fallen out of currency. It has, however, been expanded upon to consider not only the frame’s focalizing properties, but also its traits of punctuation. In her examination of textual pictoriality, Liliane Louvel specifies:

framing effects must indeed be combined and not left to only one impressionistic feeling: focalization and point of view but also paragraph indentation, typographical marks, declared deixis such as “picture the scene”, or references to opening sentences in concluding codas. (Poetics 83)

The effects of visual frames extend beyond the mere demarcation of the visual image to partake of punctuation, which is used by writers to “convey meaning and nuance […] in addition to the visual signals communicated by the look or appearance of the text itself” (Woudhuysen 227-228). Punctuation “determines meaning” (Mortimer 925). The frame, I wish to propose, works in such a way: it not merely announces the presence of the visual, but influences meaning and reading practices through the varying degrees of containment and freedom it offers.

To fully elucidate the narrative function of this particular form of graphic punctuation and to draw out its implications for reading, I concentrate on a most radical way in which the photographic frame has been repeatedly, but nonetheless surprisingly used in literature. I will focus on the inclusion of empty photographic frames in three multimodal narratives where words and photography join together 1. See also Porto (119-120).

to narrate a story about real, not imagined, people: Janice Williamson’s Crybaby! (1998), Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid (1991), and John Berger and Jean Mohr’s A Seventh Man (1975). It is not by chance that all three are forms of life-writing – autobiography, creative biography, and collective biography – for photography has often been used in life-writing because it shares with it the status of being a referential art (Adams xv). However, the photographs in these works are not mere illustrations of that which is being recounted; instead, as the empty photographic frames highlight, they communicate a consciousness of the problem of reference in language, photographic image, or both. In this sense, the use of empty frames in these narrative universes can be compared to extreme literary uses of punctuation, such as those found in the writings of Virginia Woolf, where punctuation is used “to resist meaning and interpretation, while at the same time expressing them obliquely” (Woudhuysen 236).

Weaving in and out of the observations made throughout this article is the suggestion that the demands empty frames make on readers force the point that the photograph’s storytelling capacity – a capacity that is entangled in notions of truthful representation – is located not in what is imaged on the photograph’s surface, but rather in the imaginative workings of the reader. That what is imaged on the photograph can take attention away from the necessary workings of the reader’s imagination is explored by Emanuale Martino who in his collection of short stories, Cara fotografia (Dear Photograph), encourages readers to experience the photographic image on its own terms, that is, as an image that holds meaning apart from any link to reality it may or may not have. In “Il sonno meritato” (“Deserved Sleep”), a framed blank photograph tells its viewer that unlike the other photographs that capture a precise reality and are thus bound by the constraints of the referent, it is obviously “il luogo aperto della Possibilità e della Libertà” (“the open place of Possibility and Freedom”) (84), a space that solicits and collects the imaginings of its viewer (84). Frames that frame absent photographs, photographs that may or may not have been taken, highlight the border between art and life as the site where photography works, makes sense, and gains in meaning.

In multimodal texts, the introduction of a frame around an image or around a blank space marks an abrupt shift from a verbal to a visual mode of representation. When this deceptively simple graphic mark – a closed line that delimits a visual representational space – is introduced into a mixed narrative universe, it determinately, even aggressively, punctuates the story. It does so by boldly infringing on the reading process, bringing readers to pause and break away from the familiar storyworld, that is, the world that has been coming to life in their minds, full of details and particulars strongly regulated by the telling. The introduction of a frame in the narrative universe jolts, stops, blocks readers and, when that frame is empty, it also asks them to supply information and details that may very well be suggested either verbally or visually, but that ultimately reside within their subjective imagination. As a device that interrupts reading practices and accentuates the processes of reading, the empty frame makes important and difficult demands on readers. As Mary Ann Caws suggests, interruption “is something positive: it works towards openness and struggles against the system as closure, undoing categories” (1989: 6).

John Szarkowski, past director of photography at MOMA, defines the photographic frame as “the central act of photography” (100). Stopping on its impact on viewers, he argues that it “forces a

concentration on the picture edge – the line that separates in from out – and on the shapes that are created by it” (100). The concentration on what the photographic frame makes known and what it hides, on what is seen and not seen through framing, is at the heart of Janet Williamson’s use of photography in Crybaby!. This short multimodal text is Williamson’s autobiographical account of her struggle to come to terms with her experience of childhood incest at the hands of her father. Scattered throughout the book are seven photographic images of Williamson at the age of 3, the year her father began molesting her. All of the photographs are frontal shots of a happy, carefree three-year-old girl outdoors. Surprisingly, Williamson also reproduces eight images of the back of photographs that have notes written by her father scrolled across them. All dated May 23 / 54, the autodiegetic narrator explains with a strong hint of irony that “His words of paternal love inscribe themselves on the other side of black and white images” (27). What is suggested from the very beginning is that the real narrative, the truthful account of Williamson’s personal history, lies in what is not said and, most importantly, in what the photograph does not show.

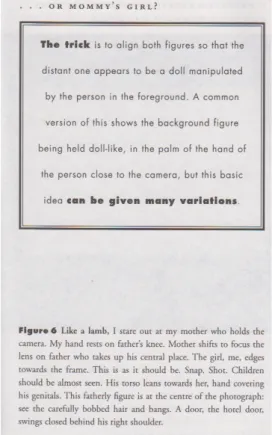

Williamson asserts so much in Crybaby!’s first full chapter, “Snapshots,” which opens with the only picture of Williamson accompanied by her father, but then presents seven unusual, radically unique photographs: all but two are announced by a dark frame framing verbal descriptions that draw note to common framing practices of photography, such as, posing, archiving, angle of vision, and editing

(Figure 1).2 Each frame is paired by a somewhat lengthy caption that imbues the missing photograph it

accompanies with contextual information by either narrating a story related to Williamson’s childhood self or accentuating common misconceptions about photographic reference. The writing within the dark frame of one such photograph reads,

The trick is to align both figures so that the distant one appears to be a doll manipulated by the

person in the foreground. A common version of this shows the background figure being held doll-like, in the palm of the hand of the person close to the camera, but this basic idea can be given

many variations. (31, emphasis original)

Here, framing is exposed as a punctuated act, one that knowingly manipulates the subject of vision and thus directs meaning.

The implications of framing for truth are evinced by the caption that reads: Like a lamb, I stare out at my mother who holds the camera. [...] Mother shifts to focus the lens on father who takes up his central place. The girl, me, edges towards the frame. [...] This fatherly figure is at the centre of the photograph: see the carefully bobbed hair and bangs. (31)

The caption draws attention to how the presentation of father and daughter in the traditional photographic portrait reproduced at the beginning of “Snapshots” (Figure 2) (assuming that reference is being made to that image or to another very similar one that is not reproduced in Crybaby!) references the power dynamics not only between the two photographed figures, but also a third figure who frames the subjects by taking the photograph. The young photographed Williamson is like the figure referred to but not seen in the empty photographic frame: with her “carefully bobbed hair and bangs” she is manipulated in a doll-like fashion into the photographic frame by the figure in the foreground, her father, and the person framing the photograph, her mother.

2. In his creative biography George and Rue (2005), Canadian author George Elliott Clarke also introduces a photographic frame to verbally describe an unshown image’s subjects (191). He does not, however, draw attention to photography, but rather to the photographed subjects.

In terms of the photographic frame-caption interaction, it is the narrator’s reading, her framing of the picture, that reveals the family’s secrets and Williamson’s trauma, while the image that could have been shown is said to deceive or, at best, conceal the secrets and traumatic experiences from the spectator. The narrator’s concentration on the frame exposes it as announcing a break in the narrative, as disrupting the narrative’s flow so to encourage readers to engage actively in its reading. Even without the verbal map offered by Williamson’s narrator, the empty frame forces readers to stop and consider what they are seeing and to consider that they are seeing it in the mind’s eye and not on the surface of the image.

That the photographic frame collects meanings that are not pictured within its confines is emphasized on the following page where the back of a photograph marked with her father’s familiar handwriting reads: “Isn’t she a doll. Look at the expression on her face. Looking right at me” (32, emphasis in original). The father that was said to figure in the photographic image is now the reader who, engaged in his own act of framing, names and claims that which is pictured. Unlike the original photographer’s, his focus falls on the imaged child who, as the underlined “me” unambiguously suggests, exists in relation to himself. His reading also differs drastically from that of the narrator who sees in what was framed the power dynamics between those involved in the photographic act, especially her own lack of power.

On the following page, the punctuating capacity of the photographic frame is further evinced as Williamson’s narrator partakes in a similar, but far more physically concrete framing exercise. She explains how she scans the photographic image of her with her father (12) and then subjects the scanned image to a series of different manipulations that alter what is pictured on its surface (33). Readers, who never see the visual results of the narrator’s framing exercise, are informed that with each revision either she or her father is cut out of the picture so that what is left of the original photograph tells a different story. Since only the narrator is privy to the new photograph, she is its only reader, ensuring that meaning is not altered by other readers. Framing what is pictured anew with each revision, the narrator thus fully lays claims to what is imaged, consciously altering the photograph’s meaning for her own viewing. What becomes apparent is that while experimenting with the photographic frame, she knowingly approaches it as an expressive narrative device whose “form can be varied to produce quite opposite effects” (Schapiro 228).

Williamson’s extended meditation on the photographic frame, which is characterised by a compelling and instigating diversity of framing techniques that come into play at various stages of the photographic act, highlights a fortiori what has been described as the “decisive and normative” function of the frame (Lebensztejn 119). Framing, according to this reading, delimits, controls, and encases meaning.3 As narratologist Katherine Young has recently argued, frames do two things: one,

they communicate the presence of a story, codifying its kind and two, they reveal an attitude toward the story, establishing a relationship between the story’s tellers and hearers (76). The layers of framing that govern the understanding of all the photographs included in Crybaby! (visually reproduced or not) insistently announce the existence of a story and also signal that such a story is constructed, that it is filtered through a subjective attitude, consciously or not.

It is thus important to note that although Williamson’s narrator exposes the normative potential of the frame, her framing and reframing exercises also confirm that photographic meaning exists at the intersection between the known and the unknown that is so forcefully announced by that very frame. Certainly, the frame works hard to control meaning, its dark contours announcing a stop in the narrative so to draw attention to a particular aspect of the many possible thoughts the story can evoke. And, yes, the frame tries relentlessly to control meaning. But, as the multiple layers of framing indicate, it ultimately always fails in its quest. It is for this reason that Williamson’s narrator posits the photographic image as incontrovertible and not incontrovertible on the same page (29) and repeatedly suggests that photographs enact the “tension between truth and not knowing” (70) that runs throughout Crybaby!’s entire narrative.

By bringing to the fore the need for and the inevitability of storytelling, Crybaby!’s empty frames unsettle the correlation between photographic image and historical truth. They also make evident the way in which the frame restricts attention and encourages the imaginative meanderings of readers. As bridge linking the visible and the invisible, the frame invites readers to contribute to the story, to imagine what is being narrated, and to become active participants in the telling. So, instead of firmly securing meaning or taming it within its borders, the frame is that mark which welcomes a continual re-reading, 3. Naficy lists this definition of framing as one among three. The other two are a “bracketing, structuring, constructing, or laying out the terrain of a topic” (1) and a “prearranging or concocting with a sinister intent” (2).

re-formulating, re-writing of that which falls within its borders.

Indeed, onto photographic images depicting unidentified children, Williamson’s narrator says to write impressions of her own past (77), reading incest everywhere (68). And, unable to recognize herself in her childhood photographs, she admits that “[g]aps and fissures, arguments and echoes make up what [she] know[s] about this child who stands before [her]” (26). Separating art from life, the frame embraces subjective viewpoints, ensuring that the photographic image partakes in a metonymic expansion, a structuring process by which the photographic image also means that which it does not show. What the frame contains ultimately recedes in importance, as it is the reader who actually makes present and meaningful that which is absent from the photographic frame itself. It follows that the semantic strength of the photographic frame, then, lies not in what it renders visible, but rather in what it withholds from the eye, but nonetheless announces as a possibility through each individual act of reading. As suggested above, these individual acts of reading announced by the frame inform each stage and aspect of the photographic act.4

The frame, then, ensures that the photographic image holds more meaning than can be predicted or known, much less controlled. Within one empty frame, the narrator specifies that the captioned photograph is a poem, thus alluding to how the photograph calls forth an elaborate set of substitutions and omissions, and revealing a scepticism toward traditional understandings of photography. Through her defiance of the referential qualities associated with photography – they are not aide-mémoires, they do not signal death or the passage of time – the narrator indisputably positions them (and her memories of that time) in the “zone of possible plots, likely scenarios, blurred images” (26). That zone of possible plots is the one that is announced by and belongs to the photographic frame. What becomes apparent through Williamson’s critique and use of the photographic frame in Crybaby! is that “the history, the facts” (180) with which she grapples throughout her writing are caught up in the fictive, always. Her empty frames thus visualize the rejection of the conventions and promises of photography – denotation, truthful likenesses, windows onto the real, aide memoires, and so forth. They are an interpretative signal, a grammatical resource that cues readers to imaginatively transfer to the storyworld and to know that they are doing so.

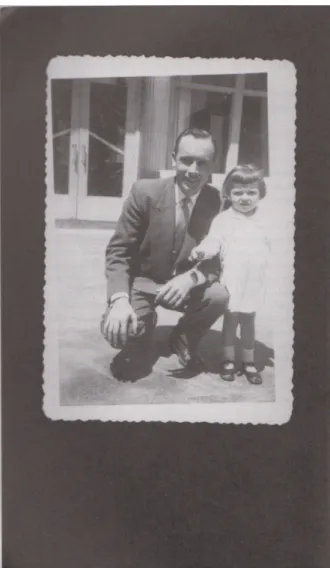

Williamson is not alone in using the photographic frame as a graphic punctuation that urges readers to step into the visual and partake actively in the meaning-making process. In The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, Michael Ondaatje begins his account of the infamous outlaw with an empty frame accompanied by a long caption that specifies, “I send you a picture of Billy made with the Perry shutter as quickly as it can be worked – Pyro and soda developer” (n.p.) (Figure 3). The photographer, whose words the caption relates, continues by explaining to the recipient the photographic techniques that s/he will experiment with and promises to send the photographic proof of “what can be done from the saddle without ground glass or tripod” and “the lens wide open” (n. pag.). Drawing attention to the technical aspects of photography, the narrator outlines his/her artistic aspirations and hints at the types of effects s/he wishes to create. The caption does not mention anything about what the photograph within

4. Baer sums up the photographic act by specifying that photographs “result from the conflict and cooperation between the photographer's intentions, the photographed person's lived experience, the viewer’s perspective, and the technical effects of the camera” (13).

the empty frame should look like or what it is meant to communicate apart from representing Billy the Kid. The caption does not, in other words, restrict the reader’s imaginative processes.

In the afterward to The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, Ondaatje specifies that during the editing process, he realized that the book needed “white spaces for the ‘pauses in the story’” (n.pag.). Admitting to having taken his cue from Canadian poet BpNichol, Ondaatje reveals that he decided to pace the book with silences and the unsaid. Of the empty frame, he specifies

‘I send you a picture of Billy...,’ which begins the book, in fact had an image of The Kid within the rectangle above the text until Barrie [his editor] suggested I simply (or perversely) remove the image within it, and suddenly the footholds of the story became mysterious. It was the reader who would now need to provide the picture of Billy. (118)

Figure 4. Ondaatje, Michael. The Collected Works of Billy the Kid. n.pag.

As Ondaatje’s declaration specifies, the empty frame does not simply indicate a missing photograph, provocative as that may be. Rather, it is a graphic mark that punctuates the story and offers up to readers a space full of possibility, one where each reader is invited – if not forced – to contribute a personal, subjective image of Billy the Kid to the narrative. The pause of the empty frame encourages or, indeed, demands each reader to step into the image, fill in the frame by exacting vision, making the invisible visible, drawing forth meaning from his or her own personal experience.5 Consequently, it opens up the

possibility for variance in meaning, inviting an indeterminate number of different, uncertain, unknown stories that flow from each reader to inform who Billy the Kid was. And, just to make sure that the full implication of filling in the dots is clear, Ondaatje reproduces the same empty frame at the end of his book, as big as a full page this time , with a tiny photographic image of himself at the age of nine wearing a cowboy suit studded with “cheap coloured glass” (118) (Figure 4).

In its capacity to open up the possibility for variance in meaning, the empty frame serves as a boundary that distinguishes a focused showing and seeing from an indeterminate, wondering seeing. Its contours highlight the fact that something must be perceived or seen, but that that something comes not 5. See Saint-Amand, who makes a similar observation with regard to absent images (235).

from within the frame, not from what is imaged on the photograph’s surface, but rather from outside of it. It is in this sense that the frame accentuates absence and incompleteness as crucial to photographic meaning.

Some theorists attribute to all photographs this invitation to readers to step into the visual. Max Kozloff, for instance, claims that the bid to “step through the [photograph’s] surface” rests on the apparent absence of an author (17). Others, like Michael North, suggest that the invitation to enter into the photograph rests upon the image’s possibility of visual maladjustment, that is, of its forcing an improper or strange seeing. With an empty frame, however, the author is not absent, nor is the seeing improper or strange. In fact, authorship is transferred to readers, willingly offered up to them so that no seeing, no visual imagining could possibly be strange or improper. In addition, the empty frame as a mark of punctuation inaugurates a unique reading experience, one where readers become aware of their own imaginative workings and fully realize that the meaning of a photographic image – its truth – has little or nothing to do with the objective. Instead, it has everything to do with the subjective. The empty frame proves that a photograph can only offer occasion for the viewer to imagine beyond it by enacting the semantic implication of the unseen.

Exposing the effects of the photographic frame on reading, Ondaatje like Williamson enacts the implications of the shift away from understandings of the photographic act that overlook the viewer. When included in multimodal texts, empty frames demonstrate that the referent does not adhere (and, by extension, that the photographic image can be independent of indexicality); indeed, it does not even need to be visualized in order to narrate a truth into existence. They force the realization that the photograph necessarily extends into the indeterminate, infinite and unpredictable realm of imaginary speculation. Neither primarily affective, nor primarily informative, the photograph’s semantic status lies predominantly with the reader and with what the reader chooses to see, imagines seeing and, ultimately, believes to see. Hence, the frame has crucial consequences for the emotional investment of readers.

But, what happens when the empty frame seems to illustrate the invisibility of its subject? Does it still punctuate the narrative and place the photograph’s meaning in the hands of the reader so that unpredictable meanings and stories can transpire?

In the second chapter of A Seventh Man, by John Berger and Jean Mohr, that examines working conditions of migrant workers, a rectangular, empty frame is reproduced (Figure 5). It is captioned “Illegal Migrant” in the same manner as the other hundred or so photographs reproduced in the text. Given this caption as well as the position of the frame in the lower half of a page describing the conditions of an illegal migrant worker it is apparent that the blank, white space within the frame is to be understood to hold a photographic image. However, it stands apart from all the other photographs in A Seventh Man since it is the only missing image and the only one that does not factor into the “List of Illustrations” at the end of the book (233-236). This omission makes one wonder what this markedly empty photographic frame contributes to Berger and Mohr’s multimodal documentary account of hardships suffered by European migrant workers during the 1970s. Does this frame announce and define a presence, and not an absence, as the author explains the photographs in A Seventh Man are meant to do (17)?

The captioned frame is introduced in the context of a discussion about the working conditions of the 80% of migrant workers who in the early 1970s lived in France illegally. What is repeatedly emphasized throughout this chapter is the unknown and the unknowable. It speaks of the possibility of a false move “with somebody quite unknown” (89-90), of a door opening to frame “an unknown person” (90) when looking for lodgings, of how “the unknown person star[es] at him with an unknowable expression” (90), of “the unknown person’s unknown reasons for shutting the door while still speaking” (90), and of the “sounds of the unknown language” (118) that surround him. In all instances, the unknown remains marked by incomprehensibility; it is so firmly positioned beyond the imagination that the migrant worker recognizes it as utterly impossible to conceive, verbally or visually.

It would be relatively straightforward at this point to argue that the blank photograph is meant to express visually the unknowable and that the empty frame is meant to make the unknown visually present. This reading would be in line with the narrator’s confirmation that unlike other photographs, the photographs in this book are intended to define a presence. Earlier, he describes a migrant worker who holds onto a photograph, specifying that “[t]he photo defines an absence” and that “[t]he photographs in this book work in the opposite way (16-17). If the blank photograph is to define a presence, then the frame signals the importance – semantic, aesthetic, social, etc. – of that which it contains, qualifying the photographed event – here, the illegal migrant worker – as visibly present. The blank space that has been deemed less-than-ordinary by being framed would thus communicate a reality and, as photographs are wont to do, even prove that such a worker is invisible, that he remains for the most part unseen.

However, throughout the chapter, the unknown is also marked by a sustained attempt, a conscious attempt, to understand. Faced with the empty frame, forced to stop and contemplate what it shows, the reader is asked to participate in a struggle towards understanding that is similar to that of the migrant worker. In this process, the reader is also made to conceive of him- or herself as actively, consciously working through uncertainties, impressions and imaginings so to reach a possible image or, put differently, a plausible visual story. Just as the illegal migrant worker is made conscious of his struggle to understand

and determine meaning when faced with the unknown, so too is the reader made conscious of his or her own attempt to bring to light, to make visible, that which the empty frame announces but withholds. In this way, the empty frame does not merely support, illustrate or prove the illegal worker’s invisibility. It is not, in other words, a redundant punctuation mark (if such a thing were possible) that confirms or further illustrates what has been related verbally. Instead of illustrating the invisible, the photographic frame actually frames the reading of photographs as a conscious activity, making readers acutely aware of their decisive role as readers. Photography critic Serge Tisseron emphasizes that the photographic image is always for someone insofar as it demands commentary (29). What is imaged, in other words, asks to be verbalized, to be expanded upon by the viewer through the very act of reading. Hence, there is no stasis, spatial or temporal, in the photograph. On the contrary, “any photograph carries a virtual spatiality and temporality which constantly dislocate its spectator from the spatiality and temporality that belonged to the referent, when the picture was taken. This is why,” as Liliane Louvel emphasizes, “photography is both a space to be explored and a time in progress” (Tisseron qtd. in Louvel, “Photography” 33). The frame that frames an invisible photograph makes the space open to readers, encouraging new stories and alternative, highly subjective ways of seeing. So, apart from awakening the imaginary processes of readers, the empty frame also forces them to take account of their own role in the storytelling process, disrupting habits of seeing and instating new, but equally provisional ways of seeing.

By introducing a new direction in the reading process, a new intonation of sorts, the empty frames found in these and other multimodal narratives force the realization that in an important way all photographs are blank spaces, spaces where what is shown needs to be imagined and not necessarily perceived. What these extreme uses of the photographic frame suggest is that the frame validates not that which is inside of it, but rather the reader who inevitably falls outside of its parameters.

The use of empty frames in multimodal narratives can thus be said to enact a poetics of photographic reading. To enact such a poetics is to distance oneself from Roland Barthes’s “ça-a-été” and to concentrate instead on the photograph’s present realization, its actual visualization, its assessment, and all that has to do with the experience reading gives rise to (Louvel, “Photography” 33; Ortel 254). To enact a poetics of photographic reading is to expose the photograph’s claim to a past moment and past event as illusory so to indicate and privilege the photograph’s inherent entanglement in the present moment of viewing. Framing and re-framing, which problematize promises of photographic reference, highlight that the uniqueness, unity and absolute truth commonly associated with the real are inevitably counteracted by what some have called “multiple and divisive cultural imprints” (Cousineau 83). Surprisingly, it is the very frame that invites these unpredictable implications and interpretations to seep into every photographic image.

What I have proposed are some notes towards establishing the effect on reading of the photographic frame, an essential, indeed, inevitable feature of the photographic image, but a feature that has received relatively little critical attention. As photographic critic John Tagg has recently observed, the photographic frame is one of “those great, open public secrets of which it is better to say nothing, from which it is better to overt one’s eyes” (5). But, to say nothing of the photographic frame is to

overlook how it stands out from the frames that belong to other sorts of images. Photography has long been theorized as a special kind of image. Alan Trachtenberg, for instance, has argued that the photograph “gives immediate access to a past” (xxviii) and that it is thus a “unique historical record, one that allows us to read, to count, even to measure what once existed” (xv). Even if we know “that the ‘objectivity’ of technical images is an illusion” (Flusser 15), the “myth of photographic truth” (Sturken and Cartwright 17), the relatively unquestioned assumption that the photograph shows what has been, continues to govern the perception of photographs. The photographic frame is thus endowed with a special power: it is believed to hold truths, historical truths.6

A second factor particular to photographic frames is that they bestow with interest and importance that which they delimit. By framing the everyday world, the photographic frame works to highlight particulars of that world and asks readers to stop, focus and reflect on what is shown on the photograph’s surface (and, by extension, in the real world). Even the most marginal of details can capture the eye once framed within the boundaries of a photographic image. And what is more, such details would most likely go by unnoticed if not for the fact that they were photographed and thus framed and accentuated, intentionally or not. The photographic frame thus works to change our perception of the world. As I have argued elsewhere with Silke Horstkotte, “the automatic inclusion of daily, ordinary, even banal details within the photograph’s frame affects the way the world is seen” (Introduction 15). The frame is thus not innocent in its gesture toward delimiting inside from outside, seen from unseen. Instead, it is like any other punctuation mark, a graphic design used to direct reading and inform understanding, and one that determines what deserves to be seen.

When included in literature, photographic frames may be said to fulfil a presentational and pictorial function. Although this is certainly part of the frame’s function, such a reading risks reducing the photographic frame to an illustrative role and, in so doing, subordinating the visual to the verbal. It also risks underestimating the interruptive nature of the frame, a characteristic that is necessary if it is to articulate and accentuate, to determine importance and indicate emphasis, to pull the reader into the narrative universe, in short, to fulfil the semantic function of punctuation.

That the photographic frame separates and excludes an event from its originating context has large ramifications for the photograph’s narrative potential. The frame, which ultimately denies the whole by intending a mere fraction of that whole, not only makes visible that which is within it, but also announces by its very parameters the possibility and the existence of an entire world beyond it. Empty frames are thus not meaningless without their photographs. As the examples analysed above show, incompleteness marks both what is inside and outside the frame and in this very incompleteness lies the multiple possibilities of storytelling. The empty frame thus at once announces the photograph’s incompleteness and signals its excess, its being vulnerable to chance at every stage of the photographic act.

6. There is no need to provide a summary of the ways in which the photographic image has been theorized as evidentially sound. The list would be quite lengthy and the summary has already been made by various critics at various points throughout the history of photography. For overviews of photography theory, see Dubois, Kemp, Squires, and Price and Wells.

Critics of photography have attributed to the photographic frame the capacity to delineate the storyworld’s particulars and endow them with meaning. What needs to be emphasized, however, is that it is not so much a question of a “static arrest and a set frame” as theorized by Philippe Hamon in his classic study Introduction à l’analyse du descriptif (18), but rather a question of imaginative openings, of possible genesis and structures, possible origins and reinterpretations. Hence, not a diegetic or narrative arrest, a final thought of sorts, but rather the full stop as an invitation for further speculation. Understood thusly, the frame is a space where the real and the interpretative work done on the real coexist.

The introduction of empty frames in multimodal texts, much more so than the reproduction of actual photographs, provokes a shift in understanding the way in which readers read photographs and appreciate their narrative potential. Empty frames accentuate how the photographic image is made not when the photographer depresses the camera shutter, but rather when the viewer looks at, experiences, reads into the photographic image. Forcing into realization that what is seen is not what is, empty frames punctuate habits of seeing and reading that necessarily incorporate what can be imagined, what may be imagined and what changes across time with experience and with every reading opportunity. It follows that the photograph actually has meaning – it works, in other words – even if the viewer has no means of visually identifying the photograph’s subject. This is so because the photographic act is tied up with private and individual practices of looking that may intersect with but are ultimately removed from the moment of the image’s making.

Derrida, in his socio-political approach to the frame, theorizes it as standing out against the two grounds it constitutes – the work and the context – and at the same time dissolving into each of them. He emphasizes its function as a bridge, where the meaning of that which is inside the frame endlessly slips into that which is outside of its borders, just as the meaning of that which is outside the frame is always marked by that which is inside of it. Marking a limit between intrinsic and extrinsic, the frame retains some degree of its disciplinary function, policing meaning while giving it life. Tagg has extended Derrida’s understanding of the frame to the photographic frame, which he defines as that which masks the “impossible juncture” of two worlds, the world of the photographic image and that of its context, between which meaning often prevaricates (5). For Tagg, the frame should be understood as “a machinery of capture and expulsion that covers the join between the image and the economy of meaning in which it comes to resonate and in which interpretation takes place” (5). Although most of his attention is devoted to discursive frames and not actual, material ones, his definition of the frame as an endless failure, as characterized by a “self-defeating overobtrusiveness” (xxxvi), points without doubt to the frame’s storytelling properties. The frame that so ruthlessly determines inclusion and exclusion, visibility and invisibility, demands the acknowledgement that meaning must be arrived at. The photographic frame thus at once holds together and apart viewer, image and context.

The use of empty photographic frames in the multimodal texts studied here show that frames do not discipline. Instead, they are open, bold invitations for readers to gather up the multiple possibilities that exist within their imaginations. The world empty frames show repeatedly and easily slips away into new and unpredictable worlds so that the story they contain and elucidate resists being fixed into a single meaning. These frames thus wreak havoc on photographic meaning, unhinging links made between photography and reality, between meaning and what is visually represented on the photograph’s surface.

Empty frames are powerful graphic punctuation marks that interrupt the narrative so that readers come to realize that they need to fill in the dots and get the job of storytelling done.

Works Cited

Adams, Timothy Dow. Light Writing and Life Writing: Photography in Autobiography. Chapel Hill and London: The U of North Carolina P. 2000.

Baer, Ulrich. Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma. 2002. Cambridge, MA: The MIT P, 2005.

Berger, John and Jean Mohr. A Seventh Man. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

Caws, Mary Ann. The Art of Interference: Stressed Readings in Verbal and Visual Texts. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1989.

Clarke, George Elliot. George and Rue. New York: Carroll and Graf, 2005.

Cousineau, Diane. Letters and Labyrinths: Women Writing / Cultural Codes. Newark: U of Delaware P, 1977.

Dubois, Philippe. L’acte photographique et autres essais. Paris: Nathan Université, 1990. Flusser, Vilém. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaktion, 2000.

Hamon, Philippe. Introduction à l’analyse du descriptive. Paris: Hachette, 1981.

Horstkotte, Silke and Nancy Pedri. “Introduction: Photographic Interventions.” Photography in Fiction. Ed. Silke Horstkotte and Nancy Pedri. Special issue of Poetics Today 29.1 (Spring 2008): 1-29.

Kemp, Wolfgang, ed. Theorie der Fotografie I-III. Munich: Schirmer-Moser, 1980-1983. Kozloff, Max. Photography and Fascination. Danbury, New Hampshire: Addison, 1979.

Lebensztejn, Jean-Claude. “Starting Out from the Frame.” The Rhetoric of the Frame: Essays on the

Boundaries of the Artwork. Ed. Paul Duro. New York: Cambridge UP, 1996. 119-141.

Louvel, Liliane. “Photography as Critical Idiom and Intermedial Criticism.” Poetics Today 29.1 (Spring 2008): 31-48.

---. Poetics of the Iconotext. Ed. Karen Jacobs. Trans. Laurence Petit. Surrey: Ashgate, 2011.

Marin, Louis. “The Frame of the Painting or the Semiotic Functions of Boundaries in the Representative Process.” A Semiotic Landscape: Proceedings of the First Congress of the International

Association for Semiotic Studies. Milan, June, 1974. Ed. Seymour Chatman, Umberto Eco

and Jean-Marie Klinkenberg. Paris: Mouton, 1979. 777-782. Martino, Emanuele. Cara fotografia. Firenze: Meridiana, 2008.

Maynard, Patrcik. The Engine of Visualisation. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1997.

Mortimer, Armine Kotin. “The Invisible Punctuation of Sollers’s Paradis.” MLN 127.4 (September 2012): 924-941.

Naficy, Hamid. “Framing Exile: From Homeland to Homepage.” Home, Exile, Homeland: Film, Media,

North, Michael. Camera Works: Photography and the Twentieth-Century Word. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005.

Ondaatje, Michael. The Collected Works of Billy the Kid. 1970. Toronto: Anansi, 1991. Ortel, Philippe. La littérature à l’ère de la photographie. N îmes: Jacqueline Chambon, 2002.

Porto, Nuno. “‘Under the Gaze of the Ancestors’: Photographs and Performance in Colonial Angola.”

Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images. Ed. Elizabeth Edwards and

Janice Hart. London: Routledge, 2004. 113-131.

Price, Derek and Liz Wells. “Thinking about Photography: Debates, Historically and Now.” Photography:

A Critical Introduction. Ed. Liz Wells. London: Routledge, 2000. 9-64.

Saint-Amand, Pierre. “La Photographie de famille dans L’Amant.” Marguerite Duras. Ed. Alain Vircondelet. Paris: Écriture, 1994. 225-240.

Schapiro, Meyer. “On Some Problems in the Semiotics of Visual Art: Field and vehicle in Image-Signs.”

Semiotica 1 (1969): 223-242.

Squires, Carol, ed. The Critical Image: Essays on Contemporary Photography. Seattle: BayPress, 1990.

Sturken, Marita and Lisa Cartwright. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 2009.

Szarkowski, John. “Introduction to The Photographer’s Eye.” The Photography Reader. Ed. Liz Wells. London: Routledge, 2003. 97-103.

Tagg, John. The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2009.

Tisseron, Serge. Le mystère de la chambre claire. Paris: “Champs” Flammarion, 1996.

Trachtenberg, Alan. “Introduction: Photographs as Symbolic History.” The American Image: Photographs

from the National Archives, 1860-1960. New York: Pantheon Books, 1979. ix-xxxii.

Williamson, Janice. Crybaby!. Edmonton: NeWest P, 1998.

Woudhuysen, H. R. “Punctuation and its Contents: Virginia Woolf and Evelyn Waugh.” Essays in

Criticism 62.3 (July 2012): 221-247.

Young, Katherine. “Frame and Boundary in the Phenomenology of Narrative.” Narrative across Media:

The Languages of Storytelling. Ed. Marie-Laure Ryan. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2004.

76-107.

Nancy Pedri is Associate Professor of English at Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada. Her major fields of research include word and image studies in contemporary literature, photography in fiction and comics studies. She has edited four volumes on word and image studies. Her work has appeared in several journals, including Poetics Today, Narrative, International Journal for Canadian Studies, Texte, Rivista di studi italiani, Literature & Aesthetics, and ImageText.