MIT LIBRARIES 3

9080

01917

6632

'f

"'i;rmmimimmmmmi^

/(feiiifilifppli

piiiliSBii

HI'mJij/ii! I;'!!};;;;«if//;;/!'ii j,

-It

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

DEWEY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

THE

ANTEBELLUM

TARIFF

ON

COTTON

TEXTILES

REVISITED

Douglas

A.

Irwin

Peter

Temin

Working

Paper

00-19

September

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

witiioutcharge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

at,; MASSACHJSETTSINSTITUTE

OFTECHNOLOGY

OCT

3 2000L.„„„._„„,

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

THE

ANTEBELLUM

TARIFF

ON

COTTON

TEXTILES

REVISITED

Douglas

A.

Irwin

Peter

Temin

Working

Paper

00-19

September

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

atThe

Antebellum

Tariffon Cotton

Textiles RevisitedDouglas

A. IrwinDepartment

ofEconomics

6106

Rockefeller HallDartmouth

College Hanover,NH

03755

andNBER

PeterTemin

Department

ofEconomics

50Memorial

DriveMIT

Cambndge,

MA

02142

andNBER

July 20,2000

AbstractRecentresearch has suggestedthat the antebellum U.S. cotton textile industry

would

have beenwiped

outhad it not receivedtariffprotection.We

reaffirmTaussig'sjudgment

thatthe U.S. cottontextile industrywas

largelyindependentofthe tariffby

the 1830s.American

andBritishproducers specialized inquite different types oftextileproducts that

were

poorsubstitutes forone another.

The

Walker

tariffof 1846, forexample, reduced theduties on cotton textilesfrom

nearly

70

percentto 25percent and imports soared as aresult, buttherewas

little change indomestic production.

Using

datafrom 1826

to 1860,we

estimate the responsiveness ofdomesticproductionto fluctuations in import prices and concludethat the industrycould have survived

even ifthetariffhad been completelyeliminated.

Acknowledgments

:We

thankparticipants at theDAE

meeting oftheNBER

Summer

Institute for

-1-1. Introduction

America's industrializationin the earlynineteenth century

was

spearheadedby

theNew

England

cotton textile industry.The

industry received astrong initial impetusfrom

theJeffersonian

embargo

and thewar-time disruptionstocommerce

from

1807 to 1815. Afterthewar, the industrypressed forandreceivedhigh tariffs toblockimport competition and domestic

outputcontinuedto expand.

The

extenttowhich

theindustrydepended upon

thetariff, however, has been asource ofdebate. Taussig (1931, pp. 135-36)opined that"the tariffof

1816

may

beconsideredajudiciousapplication ofthe pnnciple of protection to

young

industries" inpartbecause domestic producersbecame

strongenough

to survive withouttariffs "almost certainlyby

1832."By

thistime,Taussig concluded, "the cotton manufacture

was

inthemain

independent ofprotection, andnotlikely to be

much

affected, favorably or unfavorably,by changes in duties."Bils (1984) and Harley (1992)recentlychallenged Taussig's view.

They

went beyond

Taussig's informedifinformal discussion

by

explicitlyconsideringthe costs ofproducing cottontextiles in

America

andBritain in the 1830s and 1840s. Bilsconcludedthat, even aftertwo

decades ofprotection, the domestic industry

"was

stillunable tostandon

itsown.

. . asof 1833,removing

protectionwould

have eliminatedthe vastmajority of valueadded

in the cottontextileindustry."

With

additional cost evidence, drawingprincipallyon

Montgomery

(1840), Harleyconcurred and conjectured thatremoval ofthe tariff

would

have shrunk domestic output to about10 percent ofdomestic

consumption

even as late as the 1850s.One

problem

withthe Bils andafter all dependson comparative and not absolute advantage, andprovide littleinformation on

the characteristics of

American

andBritishfabrics, akeyconsideration indetermining theimpactofthe tariff.'

This paper

examines what

previous researchershave largely ignored-

namely, thehistorical recordof

how

domestic production responded tochanges in the relative price ofimports. Rather thaninferringthe impact ofthetariff

from

cost data,we

allow time series dataon

prices, domesticproduction, andimports from 1826 to 1860 tospeak on the issueofthetariff's importance.

These

data allow us toestimate the sensitivityofdomestic outputto changesin the relative price of imports, whetherdue to changesin the prices ofgoods,the exchangerate,

or the tariff rate.

We

conclude thatthe findings ofBils and Harleyexaggerate the importance ofthe tariffafter 1830. Rather,

American

andBritish cotton textile producers specialized in quite differentvarieties of cotton goods, and domestic producers wereinsulated

from

foreigncompetitionby

thedifferent characteristics oftheirproducts.

The

relative unimportance ofthe tariffis demonstratedby

the reduction inthe cotton textileduties in1846 from

nearly70

percent to 25 percent.Imports soared

by

a factorofthree and increasedtheirshare oftheU.S. marketfrom

about 7percent to about 15 percent, but there

was no

declinein domestic output. This simpleexperimentsuggests thatU.S. cotton textile producers

were

not dependentupon

the tariffand thus supports Taussig's view that the industrywas

well establishedby

thistime.'

The

cost estimates inMontgomery

(1840) also were disputed at thetime. SeeJustitia(1841). If

we

followed the approach offocusing on productioncosts today,we

would

concludethat the United Slates

would

not import automobiles fromGermany

(such asMercedes

and

-3-2.

Background

For

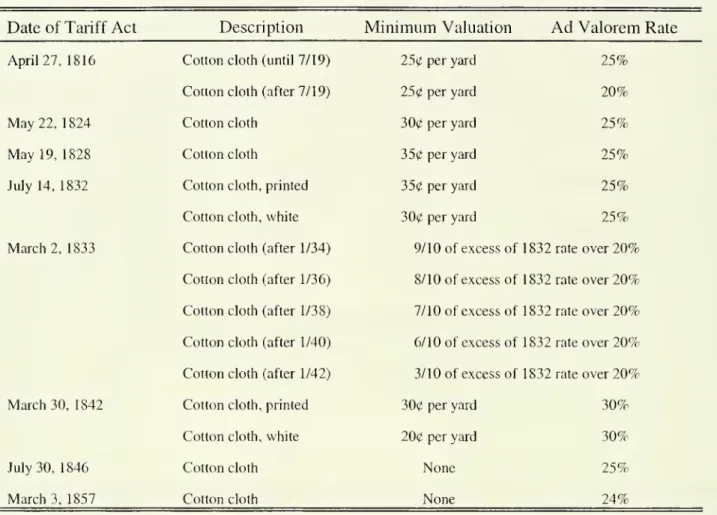

most

ofthe earlynineteenth century, theU.S. tariffon imported cotton clothwas

acombmation

of an advalorem

rate and aminimum

valuation.The

tariffof 1816, forexample,generallyregardedas thefirst"protective" U.S.tariff, consisted ofa

20

percent ad valoremrateon importedtextiles along witha 25 centperyard

minimum

valuation. Thisscheme

severelyburdened textile importsthat

were

pricedunder25 cents per yard andthus shiftedthecomposition ofimports

toward

highergrade, higher priced products.The

minimum

valuationmay

not have been bindingon

British products, however, because goods worth less than 25 centsper yard were nottypical ofBritish products duringthistime (Stettler 1970, p. 212). Taussig

commented

onlythattheminimum

excluded coarsercloths; it also excludedAsian cloth whilenot affectingimports

from

Britain.This

was

a deliberatestrategyby

FrancisLowell.As

explainedby

hiscolleague,Nathan

Appleton, the

minimum

was

designed toprotectedthefledgling industryinNew

England

without antagonizing Southerncotton exporters toEngland. Cotton growers in the South

exported

raw

cottonto Britain,and

theywere opposed

toanytariffthatwould

restrictthe sales oftheirBritishcustomers to theUnited States.

They

worried both about lossofsales and aboutfurther losses dueto possible British retaliation. Lowell's tariffdesign

shows

thatthe sectionalconflictover thetariffthat

would loom

large atmid-centurywas

alreadypresent atthe startofNew

England

industrialization(Temin

2000).After 1816, however, the

minimum

valuationbecame

increasinglybinding asBritishexportpricesoftextiles fell steadily andasthe

minimum

valuationwas

graduallyraised in

-4-period.

The

minimum

valuation, forexample,was

raisedfrom

25 centsto30

centsin the tariffof 1824, andthe ad valorem tariff

was

increasedfrom 20

percent to25 percent. In 1828theminimum

valuationwas

raised againto 35 cents.By

the 1840s, the averageBntish export priceto the United States

was

around 13cents peryard, yet theminimum

valuation on printedclothwas

30cents peryard. Thisminimum

required that the 13 cent per yardimportwould

beassessedat

30

cents; applying the30percentdutyto that price implies a charge of9cents peryard,

amounting

to an ad valorem equivalent ofover60

percent."^The

most

important changeafter thisperiod

was

theWalker

tariffof 1846,which

completelyeliminated theminimum

valuation andcut the ad valoremtariffto 25 percent.

To

determine the effective ad valoremrateon

imports,the prices ofthe imported goodsmust

be ascertained.While

U.S. trade statistics duringthisperiodreport onlythetotal value ofcotton imports (with

some

category breakdown, by country), Britainpublished statistics on thevalue and

volume

ofits cottontextile exports to various markets, includingthe UnitedStates.These

data allow the unit value ofBritish textileexports to becalculated, a usefulsummary

statisticofthe averageexport priceto the United States

and

to othermarkets.-'Both

price series^

As

Table 1 indicates, theTariff of 1842 had aminimum

valuation of30

cents per yardofprinted cloth and

20

cents per yard ofwhite cloth. Accordingto U.S. import statistics, thevalue ofprinted, stained,or colored cottonmanufactures

from

Britain vastly exceededthat ofwhite or uncoloredcotton manufactures. See, forexample, U.S.

House

of Representatives,"Commerce

and Navigation,"House

ExecutiveDocument

No. 42, 13'^ Congress, 2"*^Session (Washington, D.C.:GPO,

1849),p. 150.^

The

sourcesforthe dataare GreatBritain,House

ofCommons

(1847-48),p. 325,

House

ofCommons

(1951), p. 261,House

ofCommons

(1856), p. 385, andHelm

(1869), p. 435.These

datawere

originally utilizedby Stettler(1970, pp. 137, 168, 216-217), butwe

foundtwo

apparent errors inhis series on theaverage prices ofBritish textileexports to the UnitedStates. First, he

seems

to havetaken the Bntish export quantityfrom

thecolumn

marked

"cottons" andshow

a steady decline duringthe 1815 to1860

period, butprices aresomewhat

higheron goodsdestinedfortheU.S. market, consistentwith the effectofthe

minimum

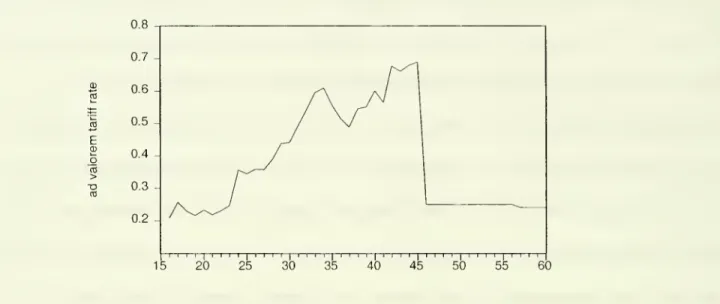

valuation in shiftingthecomposition of imports toward finer, highervalued goods. Figure 1 presentsourestimate ofthe

ad valorem equivalent importtariffon British textiles,

which

iscalculatedby

applying thetariffrates in Table 1 to the exportprice series.

As

theminimum

valuations rose and British exportpricesfell, the effectivetariffrose tonearly

70

percentby

the early 1840s.The

Walker

tariffof 1846 appearedto pull the rug outfrom

under domesticproducersby

eliminating the

minimum

valuation andapplying a simple 25 percent ad valorem tariff.As

Figure 1 strikingly demonstrates,the effectivetariff

plummeted from 69

percenttojust25 percent. Imports

from

Britain nearlytripled, soaringfrom

37 million yardsin 1846 to 105million yards in 1847, andthen falling back to 71 million yards in 1848 (Stettler 1970, p. 168).

Yet

what happened

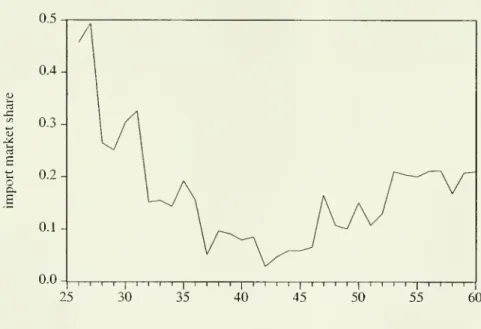

to domestic production? According to theDavis andStettler(1966, p. 221)series on

New

England

textile output, presented inFigure 2, production stalledbrieflym

1847butthen

resumed

its growth. Despite the sharp tariffreduction, therewas no

absolute decline inoutput. Figure 3

shows

that theimport market sharejumped

from roughly 5 percent in 1846 toabout 15 percent in 1847 andthen climbedto around

20

percentby

the mid-1850s.But

thisgrowth in imports occurred without a decline in domestic production.

The

uniformity ofthe growth inNew

England

textile outputinFigure 2 is striking.The

tariff

may

have affected the level ofAmerican

textileproduction to a slight extent, butit doesnotvalue ofall export categories (including cotton thread, twist, and yam).

While

the otherexportcategories are

much

less important than "cottons," it doesraise thecalculated averageprice andthusreduce the calculatedaveragetariff. Second, even usingthe

columns

that Stettlerselected,the unit value isnot

what

hereports itto bedue toan apparent arithmetic error forthe years prior

-6-seem

to have affectedits growth.As

Taussig (1931,p. 140) noted,"when

the actof 1846was

passed, the protectionistspredicted disaster; butdisaster

came

not, eitherforthe countryatlargeorforthecotton industry" asproduction steadily increased.

3. Estimatingthe

Impact

ofTariffChanges

To

explore further theimportance ofthetarifftothe domesticcotton industry,we

employ

a simplereduced-form model, based on

Grossman

(1986), to determinethe effectsofchanges inthe relative price ofimports on domesticoutput. In this model, the priceofdomestic goodsis

endogenous, as is thequantity produced,

and

this enables us toestimate the effectofthetariffon domestic production withoutassuming

that the domestic pricewas

unaffectedby

the tariff. Thisframework

enables us toexamine

thedatain amore

systematic way.On

the supply side,we

assume

that cotton textiles areproduced withraw

cotton (C),labor (L), andcapital (K).

The

production function takes thefollowingCobb-Douglas

form:(1)

Q

=

Ae'"C^'L^^K^\where

Q

is the quantityoftextileproduction,n

isthe rate ofHicksneutral technologicalprogress, and t representstime."*

Cotton is

assumed

to be atraded input andavailable to the industryat theexogenous

price Pc and laboris also

assumed

tobe supplied attheexogenous pricew.The

quantityofcotton usedand labor

employed

isfoundby

settingthe marginal value productofeach equal toits price:

"*

While

theCobb-Douglas

specification imposes certain restrictions onthe coefficients, the estimatedreducedform

ismore

general and doesnot implyany restrictions on the(2)

C

=

(a,pQ/pc),(3)

L

=

(a.pQ/w),where

p is the priceoftextileoutput, p^ is the priceofcotton, andw

is thewage. Capital is anon-traded factor

whose

supplygrows

attheexogenous

trend rate (including depreciation) of5percentperyear:

K

=

Ke^'On

thedemand

side, domestic textilessubstituteimperfectly with foreign-producedtextiles,

which

is perfectly elastic in supply and can be imported atexogenous

price p*.Domestic

textiles also substitute imperfectlywith the aggregate basket ofdomestic goods so thatdemand

ischaracterized as:(4)

Q

=

Be^"[Ep*(l-hT)/p]''[pVp]''-Y",where

\\i isthe rate of seculardemand

shift,E

is theexchange rate, p* is the (foreign)importpriceoftextiles, tisthe ad valorem tariffrate

on

importedtextiles,p^ is the price oftheaggregate basket ofdomestic goods,

and

Y

is real national income.The

domestic price and production oftextiles arebothendogenous

variables, anddomestic production isthe variable that

we

aremost

interestedin explaining. Therefore, solvingout for the reduced

form

equationand

taking logs (and suppressing time subscripts)we

have:(5) log

Q

=

tto H- a, log (Ep*(l-f-T)/pcw) -i-Ojlog (Pa/PcW)+

aj logY

+

041 -h s.Thus, domestic textile production is an increasing function ofthe tariff-inclusive importprice,

theprice of aggregate goods, and national income, and adecreasing function oftheprice of

cotton andthe

wages

paidin the textile industry.We

would

expecta^>

0, a2>

0, ttj>

0, whiletto and a^could beofeither sign. In thisequation, thedegree ofimport competitionis fully

-8-does notappearbecause import

volume

isendogenous

todevelopmentsin theUnited Statesandelsewhere.

The

domesticprice oftextiles also doesnot appearbecause it too is anendogenous

variablethat is represented

by

theexogenous

priceof cotton andwage

rate in the industry.This equationis estimatedusing annual data

from

1826 to 1860.The

quantity ofdomestictextile production (in yards)

comes

from

Davis and Stettler(1966, p. 221). This seriesis theaggregate output oftextiles in

New

England,butNew

England

accountedforover70

percent oftotalU.S. output aroundthis time

(Temin

2000, p. 122).New

England

alsocontainedvirtually all ofthe large-scalecotton production inthecountrythathas been thefocus of

historical attention.

The

U.S. import price ofBritish textiles istaken as theexportunit value, asdescribed above.

The

tariffrate is based onour calculation in Figure 1.We

ignoretransportationcosts,

which

as Harley (1992, p. 566) notedwould

add lessthan halfacent per yardto the landedcost ofBritish cloth; any changes intransportation costs are picked

up by

the time trend orarerelegatedtothe eiTortemi.

The

dollar-poundsterlingexchange

rateis thatofthe 60-daybills ofexchange

providedby

Lawrence

Officer(forpublication inthemillennial edition of HistoricalStatisticsofthe UnitedStates). U.S. laborcosts intextileproduction isthe average annual earnings perfull-time

worker from

Layer (1955, pp.46-47),which

is highlycorrelated with thelesscomplete

wage

series in Zevin (1971).The

aggregate price index istheconsumer

priceindex

from

David

andSolar (1977) andreal U.S.GNP

isfrom

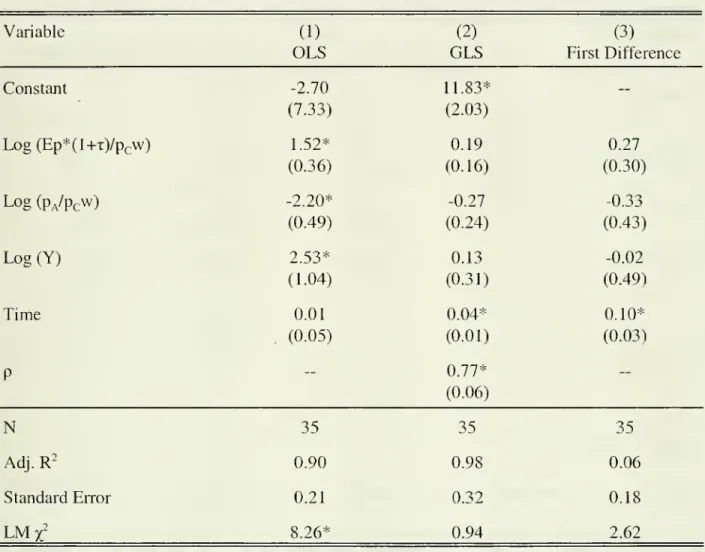

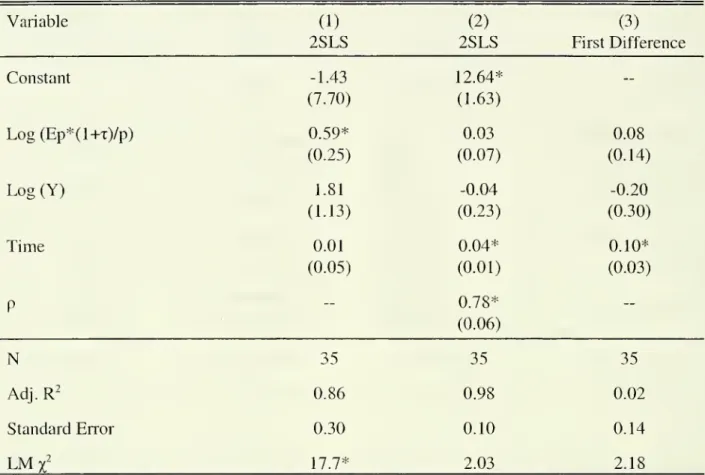

Berry (1988).Table 2 presentsthe estimationresults.

The

firstcolumn

focuses ontheOLS

results.The

coefficient a, is estimated tobe 1.52,

which

indicates that a ten percentreduction in the relativeprice ofimports

would

be expectedto reducedomestic outputby

about 15 percent. Thisis a very

-9-from 69

percentto 25 percentdue largelyto the elimination oftheminimum

valuations. Thiswould

beequivalent to a26percent decline in the priceofimported textiles, calculated as(1.25-1.69)/1.69=-0.264.

Such

a changein relative priceswould

implya40

percent declineindomestic output,

nowhere

nearwhat

was

actuallyobserved duringthisperiod. Inaddition, thecoefficient a2 carried the

wrong

sign andperversely impliesthat a decreasein the relative priceofother

consumer

goodswould

increase domestic textile output.The

coefficienton

the logofincome

plausiblyimplies thatdemand

isincome

elastic.However,

theLagrange

multipliertest statisticfor first-orderserial correlationissignificant. Serial correlation impliesthat

OLS

is notefficient, thatthe coefficientsmay

bebiased, and thetest statistics are invalid.

Column

(2)presents the generalleast squares(GLS)

estimates thatcorrect forserial correlation

by

allowing8,=

ps,.i+

e[.These

estimates are not unbiasedbut are consistent and asymptoticallymore

efficient thanOLS.

When

this is done, thecoefficient on the relative priceofimportsfalls to 0.19. It also is estimated

more

precisely,allowingus torule out thehypothesis thatthe coefficientis large. It isnotsignificantly different

from

zero (noeffect ofthetariff) andis significantlylowerthan one (proportional effect ofthetanff).

Column

(3) presents the results for afirst difference specification,which

eliminatemost

oftheserial correlation whilepreserving theOLS

standarderrors and test statistics. In this case,the coefficient

on

the relativeprice ofimportsis 0.27, similartotheGLS

estimate, andalsoinsignificandydifferent

from

zero. Ifwe

takean elasticityaround0.25 asbeing ourcentralestimate, thenthe

Walker

tariffwith its26

percentreduction in the relative price ofimports

-10-we

cannotrule outthat the effectis zero.This

modest

effectismore

consistentwith the observed growth indomestic output of 1percentin 1847.

What

accounts for thedifference between theestimatedandthe actual changeinoutput? In

column

(2), the key determinantofdomestic outputis simplythe timetrend,which

indicatesthat output

would

increase4 percenta year, on average, holding otherfactors fixed.Similarly, in

column

(3), the coefficient on time (here aconstant in thefirst differencespecification) indicates an 10 percent annual increasein domesticoutput. Regardless ofthe

relative price of imports, or even changes innational income, there

were

strongfactors pushingAmerican

outputhighereveryyear.^ Therefore, the effectofthe tariff-inducedchangeintherelative price

would

be almost completelyoffsetby

the trend increase in domestic production.What

would

bethe impact ofacompletetariffelimination? In thiscase the relative priceofimports

would

fall 41 percent.Given

an elasticity ofabout 0.25,thiswould

translate into a 10 percent decline in domestic output. This, insome

sense, is the worst case scenariofrom

thestandpoint ofdomestic producers.

While

importswould

surge as a result, and theimport marketshare

would

increase dramatically, the level ofdomestic outputwould

not fall substantially. Thisresult is alsoquite different

from

Harley,who

conjectured that free tradewould

have reduced domesticoutputby 90

percent, that itwould

have reduced the U.S. share ofthe marketto about10percent ofconsumption.

Do

we

actuallyobserve such largechanges in relativeprices?The

answer

is yes: inthe1840sthe relativeprice ofimports fell

by

nearly50

percent. Thus, such largechanges are partofthetime series datawith v^'hich theestimated response is calculated.

-11-An

alternative approach to solving outtheendogenous

variablesand estimatingareducedform

isto accountfor theendogenous

variablesby

two-stage leastsquares estimation. This approachwould

takeEp*(l+T)

asexogenous

but treatthe domestic price oftextiles (p) asendogenous

and use asinstruments such variables as the price of cotton andthedomesticwage

rate in the textileindustry.

The

domestic textile priceis that ofRussianbrown

sheeting, inNew

York, taken

from

Zevin (1971,p. 134); the results are essentiallyunchanged

ifwe

usethealternativecotton sheeting price series in theU.S.

Bureau

ofCensus

(1975, seriesE-128).Table 3 presents

some

econometric resultsfrom

this specification.The

first is a simple2SLS

regressionwhich

yields anelasticity ofdomestic output with respectto the relative price ofimports ofabout0.6. This implies thatthe

Walker

tariffof1846would

reduce domestic outputby

16 percent. Yet once again this specification is afflictedwith serial correlation.Column

(2)and

column

(3)present theinstrumentedGLS

and

first difference specifications that yieldanelasticity (againstatistically insignificantly different

from

zero) ofabout 0.05. Thiselasticityimpliesthatthe

Walker

tariffwould

reducedomestic outputby

just 1 percent,which

is verysmall, butperhaps accurate in lightofthe actual historical experience.

Due

to the smallness ofthe estimatedelasticity,we

cannot ruleout acase inwhich

changes in the relative price ofimports

would

haveno

effect on domesticproduction. In resultswe

do

notreport, however,we

find that changes in the relative priceofimports didhave a largeand statisticallysignificant effect

on

thevolume

of imports. (Theestimated elasticityis around2.5.) This impliesthatthetariff

was

quitesuccessful atreducing import volume, butthat asignificant increaseinimport

volume would

nothave detractedmuch

from

thedemand

for

-12-2 and3 (as

amounts

andas sharesofU. S. consumption).But

the growthofU. S. production,also

shown

inFigure 2, continuedunabated.As

the nextsectionpointsout,this isbecause theproduct

mix

ofdomestic andforeignproducerswas

quite different, implying thattherewere

limited opportunitiesto substitute theproducts foroneother in consumption.

4. Interpretingthe Results

The

results oftheprevioussection supportthe conclusion that atariffreductionreducedthe relative price of imports,and that this reduction, while stimulatinggreaterimports,had onlya

modest

effecton domestic production. That import competition had aminor

effecton domesticproduction is supported

by

our observation ofwhathappened

in 1846when

the cotton dutieswere

cut drastically, imports surged, and domestic outputremained high.There is

no

contradiction inthefinding that U.S. imports of cotton textiles aresensitive tothe relative price ofimports whereas domesticproduction isnot. This apparentparadox merely

suggests thatdomesticallyproducedtextiles and importedtextiles

were

different products thatwere

farfrom

perfect substitutes forone another. Britain specialized in finercotton goods whileAmerica

specialized in heavier, standardcloths.As

Zevin (1971,pp. 126-127)noted, "importsfrom

Britain and theproducts ofNew

England

mills tended to fall into quite distinctproductclassifications. . .

The

importswere

largelyginghams,woven

in intricatepatterns towhich

thepower looms had

yetbeen adopted.New

England

power looms were

supplyingplainweaves

—

sheeting, shirting, and,

somewhat

later, twills—

usuallymade

oflower countyams

than theBritish cloths." In fact,the

mean

countofyam

spun inEngland was

over50in theearly 1830s,

-13-counts spun in the

two

countries: over90

percent oftextileproduction in Lancashirewas above

20

count, whilemore

than 80 percentof outputinNew

York

was below 20

countat thistime(Temin

1988, p. 896).As

aresult, any growth inimports did not necessarilycome

atthe expenseofdomestic production.

Thisdoes not

mean

that theU.S. industrywas

completely unaffectedby

the surgeinimports

from

Britain as aresultofthe1846

tariffreduction.The

tariffaffected themix

of tradedgoods

atthemargin,forcingsome

domestic adjustments.Domestic

producers ofhigherquality,highercount goods wereforced to adapt tothe

new

competitionby

shifting theirproductmix

toward lower count, lowerquality goods. Stettler(1970, p. 224) reportedthattheratio of

low

count to high count yards producedby

his sample of firms rosefrom

2.07in 1843-44to 2.58 in1847-48.

He

notedthathigh countmillsincreasedtheiroutput rapidly in 1843-44 (afterthe tariffincrease in 1842) and

much

lessrapidlyin 1847-48 (afterthetariffreduction in 1846). But, forthe industry as a whole, theimports triggered only

minor

adjustmentsbecausemost

U.S. firmswere

notproducingfinergoods.^Fortheirpart, British producers did not shift

away

from

specializingin finerproductsandbegin producingcoarserproductsjustbecause the

American

marketopened

up. (The UnitedStates only took about 10 percent ofBritain's textileexportsduringthis period.) Britain

*" There

may

have beena slightlygreaterconcentration offiner

good

producersinPennsylvania,

which

would

have impliedsome

regional variation in theadjustmenttothelowertariff.

The

number

ofyardsperpound, an indicationofthe cloth quality,was

similarin all states in 1831, except forPennsylvania(Temin

1988, p. 895). Therewas

also a slightfall inPennsylvania's share of U.S. cotton manufactures between the

1840

and1850

censuses. ButScranton's account ofthe textileindustryin Philadelphiadoes not assign a large role to thetariff there.

One

prominent cotton mill closed attheend

ofthe 1840s, but itsowner

died, and itis hard

-14-apparently did attemptto export

some

plainer cloth,but the venture did notsucceed/The

priceof cotton textiles exportedtotherest ofthe world

was

about 5 centslowerthanthose exported tothe United Statesin the late 1830s, but

were

only about 2cents cheaperin the late 1840s. Thisindicates thatBritain

was

notexportingto othermarkets large quantities oflower count goodsthat

American

producers had specialized in. Therefore the scope for British producersto adjusttheirexport

mix

totheUnited Statesby

shiftingdown

tolower count goodswas

limited. Finally,although textile imports

from China

andIndiaroseafter the 1846 tariffreduction, theamounts

were

very small in comparison to importsfrom

Britain.Our

conclusion also isin accord with theprevioushistorical literature,which

was

skeptical ofthe tariffsimportance tothe industry.

Ware

(1931, p. 106)concluded that coarsegoods "neverreallyneeded protection, and since 1833 even high tariffadvocates had admitted

thattheycould stand alone, forordinary 'domestics' could be

made

sufficientlycheaplyin theUnitedStates to completesuccessfully with the producerof other countriesin foreign markets."

One

contemporary observed in 1850that "thebusiness of cotton manufactureswas by

thattimeso firmly established as tobe little affected by changesin legislationin regardtoduties on the

coarserfabrics requiredfordomestic consumption, to

which American

machineryhad

beenadapted" (quoted in

Copeland

1912, p. 15).This conclusion

had

been the consensus formany

decadesuntil the recentwork

ofBilsandHarley.

As

discussedin the introduction,using cost datato determine thecompetitive^

Stanwood

(1903,II, pp. 90-91)writes that "it is admitted thatthe

new

tariffcaused littleinjuryto cotton manufactures . . . large quantities ofplain cloth

were

importedin 1847, but thequality

was

sodistinctly inferiorto thatofthedomestic goods that the venture resulted in a loss.In fact,except for fine goods, laces,embroidery, and the like, the

American

manufacturerhad

the

-15-position ofthedomestic industrycan be problematic. Indeed, afterexamining the

Montgomery

costdatathat Harley relies on,Batchelder (1863,p. 91)

conceded

that costs appearedto be lowerin Britain than in

American

foreverything butmotor

power, yet still concluded that "it isquestionable whether

heavy

goods, such as drillmgand sheeting,which

make

up

averylargeproportion ofthe

consumption

ofthiscountry, can beproduced cheaperthan inthe UnitedStates."

5.

The

Tariff of1816

We

haveshown

that thetariffwas

not cntical to theAmerican

cotton industry in the1830s and 1840s. But Appleton claimedthattheTariffof 1816

was

a crucial factorin theindustry's earlierdevelopment.

What

canwe

say aboutthis earlierpenod?

We

cannot useeconometric techniques for the earlierperiod both becausethe data are very scantyand because

thevagaries of

war

and peace introduceda lot of noise into any time series.Some

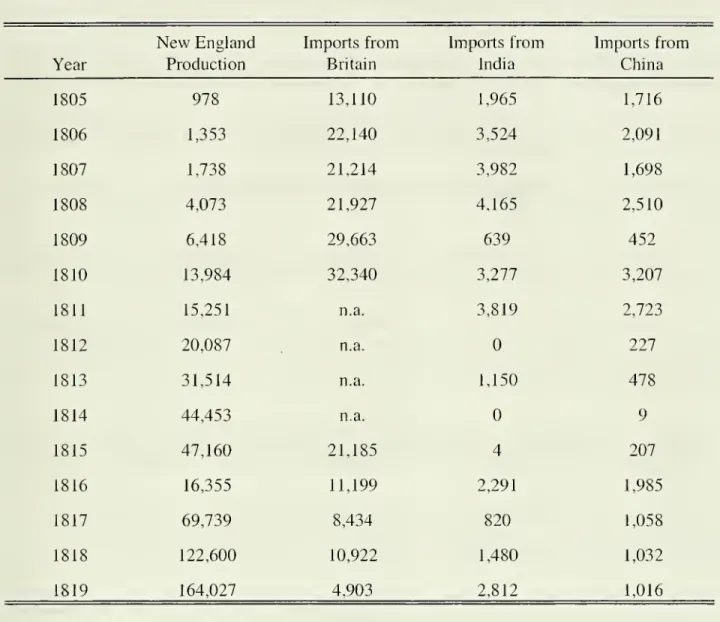

available dataareshown

inTable 4.We

obtainedthe value ofdomestic textileproduction

by

takingdomestic production inyardsfrom

Zevin (1971, p. 123) andmultiplying itby

the domestic price oftextiles inthe U.S.Bureau

oftheCensus

(1975, series E-128). Britishimports

were

recorded in variousparliamentaryreports. Imports from othercountries are harderto find.

They

were

taxed at an ad valorem rate, asshown

in Table 1, andthegovernment

lumped

all importssubject to a given tariffratetogether. In other words,there is

no

way

to distinguishcottontextile imports

from

Indiafrom

otherimportsfrom

Indiataxed atthesame

rate.American

imports from India and

Chma

were

probably notverydiverse, however, andit is likely that the

-16-cotton textiles, as Stettler(1970, p. 214) assumed.

The

data inTable4

record the totalimportsfrom

India andChina

subject to thetariffat therate paidby

cotton textileimports. Ifinaccurate,theyare overestimates ofthe cotton imports.

Itis apparent thatthe importswere verysubstantial

compared

to domestic production atthebeginning ofthecentury.

Most

ofthe cotton textilesconsumed

in theUnitedStates beforethe

Embargo

of 1808were

imported.Domestic

production outside the Waltham-style firmsinMassachusetts is omitted

from

Table4,butit cannot havebeen largeenough

to alter thisconclusion. This condition,in anycase,

was

short-hved.Domestic

productionbegan to riserapidly starting soon aftertheEmbargo

of1808was

instituted in

December

ofthat yearand continuingunderthe protection affordedby

wartimeconditions. Imports

from

India andChina

fellin 1809 andfollowing years, although they revivedbrieflyin 1810-11 as the

embargo

was

relaxed. In the yearsbefore hostilitiesbetween

BritainandtheUnitedStates, imports

from

Britain continuedunabated.They

presumably fell sharply duringtheWar

of 1812. In the protectedenvironment ofinternational hostilities, themodem

cottontextile mdustryof

New

England

grew by

an order ofmagnitudefrom

1809 to 1815.With

peace, however,came

disaster,as domestic productionfellby

two-thirdsin 1816.Although

most

historians talkofdrastic price falls as British importswere

sold atauction, thepriceof cotton cloth continuedits

downward

trendwithout anybreak.The

dramatic fallwas

inproduction.

The

New

England

cotton mills produced only about one-third asmany

yards offabric in 1816 as in 1815; production collapsedbackto the level of 1811 (Zevin 1971, p. 123).

It is nothard tosee FrancisLowell and the BostonAssociates anticipating disaster andruin.

-17-"thecombination ofthe post-war slump, the

dumping

ofBritish goods on theAmerican

marketafterthe peace,

and

thecollapse ofthe western currency sentnumbers

ofthe oldproducers tothewall. 'Halfthe spindles' in the vicinityofProvidence andFall River

were

said to be idle in1816."

The

banking andcurrency problems in the western United States cut sharplyinto thedomestic

demand

fortextiles andleftmany

manufacturerswith debtsfrom

unpaid shipments.The

import surgethat followedpeace in 1815 exacerbatedthe situation.The

value ofBritishcottonfabric exportedto theUnitedStates in 1815

was

over$20

million, almosthalf the value ofdomestic productionin thatyear.

We

have notbeen able to findrecords ofBritish cotton importsinthe yearsjust before 1815, but theimports fell

by

halffrom

1815 to1816

and stayed farbelow

the 1815 level.

The

importsshown

inTable 4from

IndiaandChina were

not largeenough

tohave causedthe dramatic contraction in domestic production, but theyclearly

show

theeffect ofpeace

by

rising sharply in 1816.The

dramatic (ifshort lived) decline in U.S. production suggeststhat domesticproducerswere

farmore

responsive toimports than theywere two

or three decades later, butthisis ahighlytentative conclusion.

Thorp

(1926, pp. 117-118) describedthe year 1815 asone

of"financialpanic" and 1816 as a "depression."

And

recordedprices did not collapsein 1815 or 1816 eventhough they

were

fallingsteadilyfrom

theirpeak on

an annual basis in 1814.Although

textileproducerscouldnotdo

anything about thegeneraleconomic

slump, theycouldtrytostop imports. Lowell appealed toCongressfortariffprotection, as recounted

by

Appleton.

He

got it, andcotton importsfrom

Asia fell, although they did not vanish asshown

inTable 4. Instead, they fellback

from

theirpeak

and did not share in the growth ofdemand

as the

-18-theirvaluein 1815.

Even

in 1847,when

the tariffwas

reduced sharply, imports were only abouthalf as large in value as theyhad been in 1815, although they didexceedthe 1815 yardagefor

onlythe thirdtime since 1815 (Great Britam 1847-48, p. 325).

As

shown

inTable 4, domesticproduction revived quicklyand

resumed

itsrapid expansion.We

draw

two

highlytentative conclusions from thesefragmentarydata. First, theAmerican

cotton industry probablywas

protectedby

theTariffof 1816.The

tariffextendedtheprotection afforded

by

embargo

andwar

toenable theindustryto grow. It ispossiblethattheindustrial growth achievedduring the years ofconflict withBritain could havebeen erased

by

free trade afterthe endofhostilities. SinceLowell

moved

with great dispatchto forestall thiseventualityand general

economic

conditionsimproved

thereafter, thiscounter-factual doesnothave afirmbase. There

was

onlyone yearinwhich

the industry facedforeign competitionwithout ahigh tariffafterits initial growth.^

Second, British imports

were

decreasedby

thetariffof 1816, despiteLowell's cunningdesign ofthe

minimum.

The

British appearto have specializedin higherqualityexportsto theUnited Statesat leastpartlyin response tothe

American

tariffstructure.The

differencein qualityofdomestically producedand imported cotton inthe 1830s and 1840s noted above

may

havebeen partly the result ofthe tariff. Ifso, therobust nature ofthe domestic industryinthe faceof

imports inthe 1830s and 1840s

may

have been partlythe result oftheTariffof 1816 in shapingthenature of

Anglo-American

trade incotton textiles.^ Indeed,

Ware

(1931, p. 72) argued that "Thereis also

no

question that domesticsheetings were actually in needof

no

protection, forbefore thepassage ofthe [1816] tarifftheWaltham company

was

enlarging its business in order to meet a rapidly growingdemand."

Zevin (1971, p. 128)concluded that "the tariffmade

no

significant contnbutionto the secular

-19-6.

Conclusions

This paperhas

produced two

strands ofevidencein support ofthefindingthatAmerican

textilemanufacturers were well established

by

the 1830s. First, there isthe actual response ofthe industrytothesharp tariffreduction of 1846. Imports surgedas aresult,butdomestic

production appears tohave been virtuallyunaffected. Second, usingtime series data,the

estimated effectofchanges inthe relative price ofimports on domestic production appearsto be

small.

Both

pieces ofevidence are consistentwith one anotherand

suggest, as historicalcontemporaries observed, that British

and

American

productswere

quite differentfrom

oneanother.

We

conclude that high tariffswere

notanessentialcomponent

ofthe survival andsuccess ofthe laterantebellum domestic cottontextile industry, although theearlycotton

-20-Figure 1:

Average

Ad

Valorem

U.S.Tariffon BritishTextileImports,1816-1860

0.8 0.7 0) 0.6 ra 0.5 E Q) O 0.4 CO > to 0.3 0.2

-21-Figure 2: Cotton Textiles:

New

England

Productionand U.K.

Imports,1825-1860

1000000 800000

V

600000 -oo

400000p

200000VS.Production U.K.Imports

Figure 3: ImportsofCottonTextiles

from

UnitedKingdom

as Share ofU.S. Market,1825-1860

-22-Table

1: U.S. Tariffon Imported Cotton Cloth

Date ofTariffAct Description

Minimum

ValuationAd

Valorem

RateApril27, 1816 Cottoncloth(until 7/19) 250 peryard

25%

Cottoncloth(after7/19) 250 peryard

20%

May

22, 1824 Cottoncloth 300 per yard25%

May

19, 1828 Cottoncloth 350 peryard25%

July 14, 1832 Cottoncloth,printed 350 per yard

25%

Cottoncloth, white 300per yard

25%

March 2, 1833 Cottoncloth (after 1/34) 9/10 of excess of1832rateover

20%

Cottoncloth (after 1/36) 8/10 of excess of1832rateover

20%

Cottoncloth (after 1/38) 7/10 of excess of1832rateover

20%

Cottoncloth (after 1/40) 6/10 of excess of1832rateover

20%

Cottoncloth (after 1/42) 3/10of excess of1832rateover

20%

March30. 1842 Cottoncloth, printed 300peryard

30%

Cottoncloth, white 200 peryard

30%

July 30. 1846 Cottoncloth None

25%

March3, 1857 Cottoncloth None

24%

-23-Table

2:Reduced-Form

Estimates ofDomestic

ClothProduction

Dependent

Variable:Log

ofDomestic

ProductionVariable (1) (2) (3)

OLS

GLS

First DifferenceConstant

Log

(Ep*(l-i-T)/pcW)Log

(Pa/Pcw)Log(Y)

Time

-2.70 11.83*—

(7.33) (2.03) 1.52* 0.19 0.27 (0.36) (0.16) (0.30) -2.20* -0.27 -0.33 (0.49) (0.24) (0.43) 2.53* 0.13 -0.02 (1.04) (0.31) (0.49) 0.01 0.04* 0.10* (0.05) (0.01) (0.03)—

0.77* (0.06)—

35 35 35 0.90 0.98 0.06 0.21 0.32 0.18 8.26* 0.94 2.62N

Adj.R2

StandardErrorNote: * indicates significance atthe 5 percentconfidence level. Standard errors have been

-24-Table

3: Instrumental-Variable Estimates ofDemand

forDomestic

ClothDependent

Variable:Log

ofDomestic

ProductionVanable

(1) (2) (3)2SLS

2SLS

FirstDifference ConstantLog(Ep*(l+x)/p)

Log

(Y)Time

-L43

12.64*—

(7.70) (1.63) 0.59* 0.03 0.08 (0.25) (0.07) (0.14)L81

-0.04 -0.20(LIB)

(0.23) (0.30) 0.01 0.04* 0.10* (0.05) (0.01) (0.03)—

0.78* (0.06)—

35 35 35 0.86 0.98 0.02 0.30 0.10 0.14 17.7* 2.03 2.18N

Adj.R^

StandardErrorLMr

Note: * indicates significance at the 5 percentconfidence level. Standarderrors have been

corrected forheteroskedasticity. Instruments include logofincome, log ofprice of

raw

cotton,

-25-Table

4: U.S. ClothProduction

and

Selected Imports, 1805 to1819

(thousands ofdollars)

New

England

Importsfrom

Importsfrom

Imports fromYear

Production Britain IndiaChina

1805

978

13,110 1,965 1,716 1806 1,353 22,140 3,524 2,091 1807 1,738 21,214 3,982 1,698 1808 4,073 21,927 4,165 2,5101809

6,418 29,663639

452

1810

13,984 32,340 3,277 3,207 1811 15,251 n.a. 3,819 2,723 1812 20,087 n.a.227

1813 31,514 n.a. 1,150478

1814

44,453 n.a. 9 1815 47,160 21,1854

2071816

16,355 11,199 2,291 1,985 1817 69,739 8,434820

1,058 1818 122,600 10,922 1,480 1,032 1819 164,027 4,903 2,812 1,016Sources:

New

England

production (in yards)from

Zevin (1971), p. 123, multiplied bythedomesticprice ofRussian

brown

sheetingfrom

U.S. Bureau oftheCensus

(1975), Series E-128.Imports

from

Britain:from

Stettler (1970), p. 108, andGreat Britain (1847-48). Other Importsfrom

U.S. Congress (1832-34), Vols. I,H.

-26-References

Batchelder, Samuel. Introduction andEarly Progress ofthe Cotton Manufacture ofthe United

States. Boston: Little

&

Brown,

1863.Berry,

Thomas

Senior. "Production andPopulation Since 1789, RevisedGNP

Seriesin ConstantDollars." BostwickPapers No. 6.

Richmond,

VA: The

Bostwick

Press, 1988.Bils, Mark. "TariffProtection and Production in theEarly U.S. Cotton Textile Industry."

Journal of

Economic

History44

(December

1984): 1033-1045.Copeland, Melvin T.

The

Cotton Manufacturing Industryofthe UnitedStates. Cambridge:Harvard UniversityPress, 1912.

David, Paul, and Peter Solar.

"A

BicentenaryContribution to theHistory ofthe CostofLivinginAmerica," in Research in

Economic

History. Greenwich,CT:

JAIPress, 1977.Davis, Lance, andH. Louis StettlerIH.

"The

New

England

CottonTextile Industry, 1825-1860: Trends and Fluctuations." Output,Employment,

andProductivity inthe United States after1800. Studies in

Income

and Wealth, Vol. 30.New

York: National Bureau ofEconomic

Research, 1966.Great Britain,

House

ofCommons.

AccountsofCottonWool

Imported, and ofCottonManufacture, and Cotton Twist,

Yam

orThread

ExportedinEach Year

1815 to 1847. SessionalPapers 1847-48, Vol 58.

GreatBritain,

House

ofCommons.

AccountsofCottonWool

Imported, and ofCotton Manufacture, and Cotton Twist,Yam

orThread

ExportedinEach

ofthe Three Years 1848, 1849. and 1850. Sessional Papers 1851,Vol

53.Great Britain,

House

ofCommons.

Retums

of Quantities and Declare Value Importedfrom

theExported tothe United States. Sessional Papers 1856,

Vol

55.Harley, C. Knick. "Intemational Competitiveness ofthe

Antebellum American

CottonTextileIndustry."

Joumal

ofEconomic

History52 (September 1992): 559-584.Helm,

Elijah."The

Cotton Trade oftheUnitedKingdom." Joumal

ofthe Royal StatisticalSociety 32

(December

1869): 428-437.Grossman,

Gene.M.

"Imports as aCause

ofInjury:The

Case

ofthe U.S. Steel Industry."Joumal

of IntemationalEconomics

29(May

1986): 201-223.

-27-Ameica

. Newburyport:Marss

and Brewster, 1841.Layer,Robert G. Earnings ofCottonMill Operatives, 1825-1914. Cambridge: Harvard

UniversityPress, 1955.

Montgomery, James

A.A

Practical Detail ofthe Cotton ManufactureoftheUnitedStates ofAmerica

.Glasgow:

J. Niven, 1840.Scranton, Philip. Proprietary Capitalism:

The

TextileManufacture at Philadelphia, 1800-1885 (Cambridge:Cambridge

UniversityPress, 1983).Stanwood,

Edward..American

Tariff Controversies in theNineteenth Century. 2 vols. Boston:Houghton,

Mifflin,&

Co., 1903.Stettler,

Henry

Louis, in.Growth

andFluctuations in theAnte-Bellum

TextileIndustry. Ph.D.Thesis,

Department

ofEconomics, Purdue

University, 1970.Taussig, Frank

W.

The

TariffHistory ofthe United States. 8*Edition.New

York: G. P.Putnam's

Sons, 1931.Temin,

Peter. "ProductQuality andVertical Integration in the EarlyCottonTextile Industry."Journal of

Economic

History48

(December

1988): 891-907.Temin,

Peter."The

Industrialization ofNew

England, 1830-80," inPeterTemin

(ed.). Engines ofEnterprise:

An

Economic

History ofNew

England

.Cambridge:

Harvard

UniversityPress, 2000.Thorp, WillardL. Business

Annals

.New

York: NationalBureau

ofEconomic

Research, 1926.U.S.

Bureau

ofthe Census. Historical Statistics ofthe UnitedStates,From

ColonialTimes

to1970. Washington, D.C.:

GPO,

1975.U.S. Congress.

American

State Papers:Commerce

and Navigation. Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832-34.Ware,

CarolineF.The

EarlyNew

England

Cotton Manufacture. Boston:Houghton

Mifflin Co.,1931.

Zevin,RobertB.

"The

Growth

ofCotton Textile Production After 1815." In Robert Fogel andStanley

Engerman

(eds.).The

Reinterpretation of America'sPast.New

York: Harper&

Row,

Date

Due

MIT LIBRARIES