HAL Id: hal-00358909

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00358909

Submitted on 5 Feb 2009HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Essential characteristics of Lizu, a Qiangic language of

Western Sichuan

Ekaterina Chirkova

To cite this version:

Ekaterina Chirkova. Essential characteristics of Lizu, a Qiangic language of Western Sichuan. Essential characteristics of Lizu, a Qiangic language of Western Sichuan, Nov 2008, Taipei, Taiwan. pp.191-233. �hal-00358909�

Workshop on Tibeto-Burman Languages of Sichuan November 21-24, 2008 Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica

Essential characteristics of Lizu, a Qiangic language of Western Sichuan

1Katia Chirkova (CRLAO, CNRS)

1. Introduction

1.1. The Lizu-Tosu-Ěrsū relationship and the Ěrsū language: Previous research and outstanding challenges

This paper reports on the Lizu language (Lìsū 栗苏), as spoken by approximately 4,000 people who reside in Mùlǐ Tibetan Autonomous County 木里藏族自治县 (WT smi li rang

skyong rdzong), which is part of Liángshān Yí Autonomous Prefecture 凉山彝族自治州 in

Sìchuān Province 四川省 in the People’s Republic of China.

In current scholarship on Sino-Tibetan linguistics, Lizu is held to be one of the three dialects of the Ěrsū 尔苏 language, as researched and described by Sūn Hóngkāi 孙宏开 in the early 1980s (Sūn 1982, 1983: 125-139). The remaining two dialects of Ěrsū are Tosu (Duōxù 多续) and Ěrsū proper. In this conception (Sūn 2001: 159), Ěrsū (in the totality of its dialects) is a language spoken by over 20,000 people in (i) the counties of Shímián 石棉 and Hànyuán 汉源 of Yǎ’ān 雅安 municipality (1 on the Map); (ii) the counties of Gānluò 甘洛, Yuèxī 越西, Miǎnníng 冕宁 and Mùlǐ 木里 of the Liángshān Yí Autonomous Prefecture (2 to 5, respectively, on the Map), and (iii) in the county of Jiǔlóng 九龙 of the Gānzī Tibetan Autonomous Region 甘孜藏族自治县 (6 on the Map), all in the province of Sìchuān.

1The work reported in this study has been supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (France) as part of

the research project “What defines Qiang-ness? Towards a phylogenetic assessment of the Southern Qiangic languages of Muli” (ANR-07-JCJC-0063). I am thankful to my principal Lizu language consultant, Mr. Wáng Xuécái 王学才, for his work with me, for his enthusiasm for this project as well as for the warm welcome he gave me into the Lizu community. I am grateful to Sūn Hóngkai 孙宏开and Huáng Xíng 黄行 of the Chinese Academy for Social Sciences, and to Mr. Lǔróng Duōdīng 鲁绒多丁 [Ldʑi-Hʂɛ̃ Hlu-Hzũ Hto-Hdɪ̃] and the local

authorities of Mùlǐ Tibetan Autonomous County, for support in the organization of my fieldwork in March-April 2008. I also thank Alexis Michaud for his assistance during recording sessions, useful post-recording exchanges as well as for his companionship during this stay in Mùlǐ.

Map 1. Location of the Ěrsū language (Map adapted from http://sedac.ciesin.org/china/admin/bnd90/t5190.html)

Of these dialects of the Ěrsū language, Ěrsū, spoken in Gānluò, Yuèxī, Hànyuán and Shímián counties, is the eastern dialect; Tosu, spoken in the counties of Mùlǐ and Jiǔlóng, is its central dialect; whereas Lizu is the western dialect of Ěrsū. All three names, Ěrsū, Lizu and Tosu are reported to mean ‘white people’, the joint autonym of the group. (Overall, this interpretation holds for Ěrsū and Lizu; but not in the case of Tosu. The precise meaning of “Tosu”, the autonym of the Tosu people, is currently unclear. It is in any case synchronically unrelated to the word for ‘white’ in this variety (Kristin Meier, p.c.). The second morpheme (su or zu) is in all cases the marker of agentive nominalization, ‘one who V’, as in Lizu, [Hʂe-Ltsv=Hsv]

‘ironsmith’, literally, ‘one who forges iron’.

While Sūn conducted fieldwork on all three dialects of the Ěrsū language, he released only his eastern dialect data (based on the Ěrsū variety of Gānluò) in the form of a grammatical sketch (Sūn 1982, 1983) and a 1,000-item vocabulary list (Sūn et al. 1991).

The central dialect, Tosu, was studied by Nishida Tatsuo in the 1970s based on Chinese and Tibetan transcriptions of Tosu vocabularies recorded in the Xīfān yìyǔ 《西番译 语》 [Vocabularies of Western Barbarian languages] during the Qiánlóng 乾隆 reign (1736-1796) of the Qīng 清 dynasty (Nishida 1973). In his later work, Nishida (1976, quoted from Bradley 1979: 16) suggests a close link between Tosu and Lolo-Burmese languages, on the one hand, and between Tosu and Tangut, on the other hand, proposing a separate Tangut-Tosu subgrouping within Lolo-Burmese. Further research on Tosu has until recently been unfeasible due to the complete absence of data. (To my knowledge, no field data on Tosu have even been published, except for a 30-item word-list in Nishida and Sūn 1990: 17.)

Finally, Lizu, the western dialect of the Ěrsū language (the variety spoken in the county of Mùlǐ: Kǎlā 卡拉乡 and Luǒbō Townships 倮波乡), has been investigated by Huáng Bùfán 黄布凡 and Rénzēng Wāngmǔ 仁增旺姆, who published a short grammatical sketch (Huáng and Rénzēng 1991) and a 1,800-word list (Huáng et al. 1992). Huáng and Rénzēng refer to the language-object of their study as [lʉ55zʉ53] (Lǚsū, 吕苏语) by the autonym of the

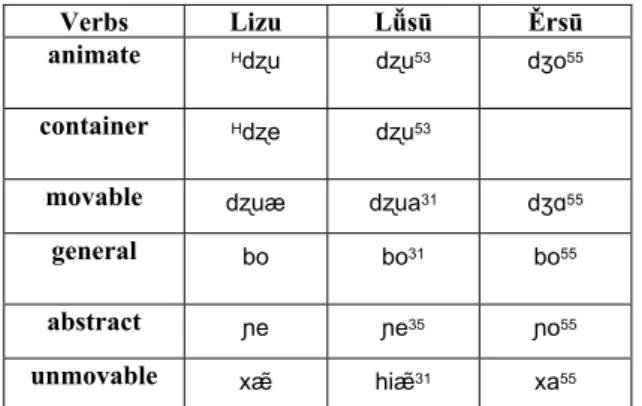

In sum, little information on the three varieties is currently available. Sūn, the proponent of this grouping, notes that Ěrsū, Tosu and Lizu are not mutually intelligible and share only 50% cognacy (among a further unspecified word sample) (Nishida and Sūn 1990: 15). At the same time, Sūn stresses that salient structural similarities between the three varieties in all linguistic sub-systems leave no doubt that the three stand in a dialectal relationship to each other (Sūn 1982: 241). A comparison of available Ěrsū and Lǚsū data and my Lizu data indeed suggests that the three are very similar in the lexicon and grammatical organization, as shown throughout the paper. Conversely, how exactly Tosu relates to Ěrsū, Lǚsū and Lizu is less evident, due, again to the absence of data.

The Ěrsū language, with Ěrsū, Lizu and Tosu as its alleged dialects, is currently held to be a member of the southern branch of the putative Qiangic subgrouping within the Sino-Tibetan language family (Bradley 1997: 36-37, Thurgood 2003: 17). Notably, the Ěrsū language appears to occupy a prominent place among other southern Qiangic languages, as it constitutes a separate node (Ěrsū yúzǔ 尔苏语组), which comprises the Ěrsū, Nàmùyì 纳木义 and Shǐxīng 史兴 languages, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Qiangic subgrouping of the Sino-Tibetan language family (adapted from Sūn 2001: 160)

Overall, this grouping implies that the Ěrsū language possesses some special characteristics that are also shared by Nàmùyì and Shǐxīng and that set these three languages apart from other subgroupings within Qiangic. Unfortunately, the precise criteria underlying this grouping of Ěrsū, Nàmùyì and Shǐxīng in one node have never been made explicit. The lack of available data on these languages currently renders the hypothesis of a particularly close relationship that obtains between them unproven.

Recent years have witnessed an upsurge of interest in Qiangic languages and linguistics. Fieldwork research is presently carried on all three alleged dialects of the Ěrsū language (Sūn Hóngkāi on Ěrsū; Kristin Meier of Leiden University on Tosu; Dominic Yu of the University of California at Berkeley on the Miǎnníng variety of Lizu; and myself on the Mùlǐ variety of Lizu) as well as on the Nàmùyì and Shǐxīng languages. Needless to say, more

data are bound to improve our understanding of the relationship between the said languages and to contribute to the evaluation of the tenability of the existing hypotheses: (i) Ěrsū-Tosu-Lizu as three dialects of a single language, and (ii) Ěrsū-Nàmùyì-Shǐxīng as one genetic node. The present outline of the essential characteristics of the Lizu variety spoken in Kǎlā Township of Mùlǐ county aims to contribute to these objectives.

1.2. Data sources and goals

This paper is based on a total of one and a half month of linguistic fieldwork on Lizu in the town of Qiáowǎ 乔瓦, the administrative seat of the Mùlǐ Tibetan Autonomous County, in March-April 2008. The language data and most of the background information have been provided by my principal language consultant Mr. Wáng Xuécái 王学才, Tibetan name [H si-Hnɑ̃ Lrẽ-HLtɕʰĩ] (WT bsod nams rin chen), a native of the Kǎlā Township in Mùlǐ County. The

Lizu variety of Kǎlā is closely related to that described in Huáng and Rénzēng (1991), Lǚsū. These two varieties essentially vary in their respective tonal make-up. For example: (in my transcriptions, [H] roughly corresponds to the tone value “55”, and [L] to “33” in Chao Yuen Ren tone letters) ‘horse’: Lizu [HLnbɚ], Lǚsū [nboɹ35]; ‘colt’: Lizu [Hnbɚ-Lje], Lǚsū [nboɹ33jʉ 53]; ‘onion’: Lizu [Hfv̩-Lbv̩], Lǚsū [fu33bu53].

This paper is a fieldwork report; that is to say that the provided analysis is constrained by and restricted to the recorded data (a 2,000-item word-list, five annotated and translated traditional stories, sentences elicited from Chinese) and the phenomena therein. In view of these limitations, this paper certainly does not aspire to provide an exhaustive account of the linguistic organization of Lizu. Neither is it conceived as an all-encompassing description of the collected data — in an effort not to double the information that equally applies to Lizu, Lǚsū and Ěrsū, but is already provided in Sūn (1982, 1983) and Huáng and Rénzēng (1991), e.g. the organization of the pronominal system, the expression of negation or the formation of questions. Instead, I concentrate on the analysis of Lizu nominal and verbal marking (postpositions and enclitics), i.e. tangible manifestation of its grammatical make-up. In this paper, I am primarily concerned with two questions: (i) what grammatical relations and grammatical features are encoded in Lizu; and (ii) by what means. In connection to the latter issue, I divide all discussed markers in sets based on the grammatical features that they encode and pay close attention to the internal organization of these sets: types of relationships that obtain between various markers: grammatical paradigms, if any, or any other kind of patterning (semantic, syntagmatic). These grammaticalized features together with their associated markers are set out for comparative purposes: (i) Ěrsū-Tosu and (ii) Lizu-Nàmùyì-Shǐxīng, as outlined in §1.1.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides general information on Lizu: location, origins, dialect variation and endangerment. Sections 3 details Lizu phonetic, phonological and tonal make-up and presents the transcription system adopted in this study. Sections 4 and 5 focus on Lizu nominal and verbal marking, respectively. The paper is concluded by a preliminary comparison between Lizu, Lǚsū and Ěrsū, on the one hand, and Lizu and Shǐxīng, on the other, in section 6.

3. Lizu: General information

The geographical distribution of Lizu, as suggested by my language consultants, partially overlaps with that proposed for the Ěrsū language by Sūn, thus confirming Sūn’s claim of a continuum of closely related varieties, located between Yǎ’ān, Gānzī and Liángshān. According to my language consultants, the Lizu language is spoken in Jiǔlóng, Miǎnníng, Yuèxī and Mùlǐ (Kǎlā and Luǒbō Townships) by approximately 7,000 speakers.

According to the oral history of the group, the Lizu originate in the area near Chamdo 昌都 in Tibet. The tradition holds that they migrated to the areas of their current settlement roughly 15 generations ago. The migration route allegedly passed through Qīnghǎi 青海, Yuèxī, Miǎnníng and Luǒbō (a township at the border of the present-day Miǎnníng and Mùlǐ counties) and Mùlǐ, the latter being the most recent place of settlement.

The Lizu language is reportedly a dialect continuum, consisting of no less than 7 distinct varieties. Interestingly, the variety of the Nàmùyì language, spoken in Luǒbō Township of Mùlǐ, is considered by my language consultants as one of Lizu dialects. The seven dialects of Lizu (including Nàmùyì) are:

1. [Hʂæ-Ltɕʰo HLpæ] ‘western dialect’, spoken in Kǎlā and Luǒbō Townships of Mùlǐ County.

This is the native language of my principal language consultant, and the subject of the present description.

2. [Hnbo-Llu HLpæ], Kǎlā Township, Mùlǐ County

3. [Lngo-Hræ HLpæ], Luǒbō Township, Mùlǐ County (Nàmùyì)

4. [Hmi-Ltɕʰu HLpæ], Miǎnníng County

5. [Hsõ-Ldʑi HLpæ], Yuèxī County

6. [Hndʑu-Hji HLpæ], Jiǔlóng County

7. [Hndʑi-Lsu HLpæ], Jiǔlóng County.

The autonym of the Lizu means ‘white people’. In fact, my principal language consultant vacillated between two forms of this name: [Hli-Hzu] and [Hly-Hzu]. In my analysis,

this variation is likely to be due to the sound change of the word for ‘white’ from /li/ to /lju/ in his dialect (‘white’ in the Lizu of Mùlǐ is [LHlju]).2 Consequently, the word for ‘white’ in [H ʂæ-Ltɕʰo HLpæ] no longer matches the morpheme ‘white’ in the autonym, viz. /li/ in [Hli-Hzu], with

the result that it is at times hypercorrected to /lju/, i.e. [Hlju-Hzu].

Among the seven Lizu dialects, [Hndʑu-Hji HLpæ] deserves a special note. Jiǔlóng

County, where this dialect is spoken, is the scene of action of many a traditional Lizu stories. The protagonists of these stories are consequently locals of Jiǔlóng and speak [Hndʑu-Hji HLpæ]

as their native dialect. Therefore, whenever a character in a traditional story is quoted literally, my language consultants use [Hndʑu-Hji HLpæ], despite the fact that the story is narrated in

[Hʂæ-Ltɕho HLpæ]. Such quotations give a glimpse of the diversity of Lizu, as salient

phonological, lexical and grammatical differences obtain between [Hndʑu-Hji HLpæ] (at least in

the rendering of my language consultants) and [Hʂæ-Ltɕʰo HLpæ], the Lizu variety-object of

this study. Consider the following sentence quoted from the story “The Pata-tree, a witch and

2 That Lizu [y] in some cases developed through the diphthongization of /i/ is supported by Huáng and

Rénzēng’s (1991: 137) observation of a free variation between [i] and [iu] before the initial l- in Lǚsū, e.g. [ku33liu53] vs. [ku33li53] ‘donkey’. Interestingly, Lǚsū [li]~[liu] in some occasions interplays with Lizu [ɚ], e.g.

‘donkey’: Lǚsū [ku33li53] ~ [ku33liu53] vs. Lizu [Lku-HLɚ]; whereas Lizu combinations of the intial l- with the high

front vowel /i/ or the glide -j- interplay with Ěrsū [əɹ], e.g. ‘white’: Lizu [LHlju], Ěrsū [əɹ55]; the autonym of the

group: Lizu [Hli-Hzu], Ěrsū [əɹ55su55]; ‘rob, loot’: Lizu [LHlju], Ěrsū [əɹ55]; ‘wind’: Lizu [Lme-HLlje], Ěrsū [mɛ55əɹ55];

a clever little girl”; the upper transcription line represents [Hʂæ-Ltɕʰo HLpæ], the second

transcription line — [Hndʑu-Hji HLpæ]:

(1) Hme Lne-Lnde, LHngwæ Lʑe Lge.

Hmi Ltɕʰa Hrua Ltɕu

sky downward-clear rain fall N-CTRL

‘The sky is clear, but it’s raining.’

The Lizu people of Mùlǐ reside among the Chinese, and have essentially adopted their lifestyle and customs. Most Lizu’s are bilingual in Chinese and their language has numerous Chinese loanwords, especially in the cultural lexicon, e.g. [HLtv] ‘beans’ (dòu 豆), [Htɕa-HLtã]

‘yoke’ (jiādàn 枷档/枷担), [Hɕiã-Lɕiã] ‘box’ (xiāng 箱).3 The Lizu’s of Mùlǐ are also in close

contact with the Prinmi, the local ethnic majority, and many Lizu’s are also fluent in this language. The Lizu practice Tibetan Buddhism along with local shamanist religions, and their language also has some Tibetan loanwords, either adopted through Prinmi or borrowed directly from the local varieties of the Tibetan language, e.g. [HLnbɑ] ‘mask’ (WT bag, [mbɑ 55] in the local Tibetan dialect, Kami Tibetan), [Hsi-HLnge] ‘lion’ (WT seng ge, Kami Tibetan

[si55ngi55]).

Lizu is an endangered language due to the decreasing number of fluent speakers and the ongoing shift towards Chinese. The younger generation speaks Lizu increasingly less, preferring Chinese instead for interpersonal communication. Intermarriages of the Lizu with other ethnic groups are on the increase, and mixed couples often adopt a third language for family communication, mostly Prinmi or Chinese, so that Lizu is not passed on to children as a result. Finally, the pressure from Chinese intensifies progressively, good profiency in Chinese being valued as a necessary precondition for success in seeking employment and education opportunities.

Fortunately, Lizu seniors, with whom I came in contact, are highly aware of the value of their language and culture and are convinced of the necessity to keep them alive, despite the aforementioned negative trends. The Lizu as spoken in Mùlǐ is relatively robust, and even coins neologisms, such as [Hʐæ-Ltɑ-Lpi-Lme] ‘mobile phone’ (< [ʐæ] ‘chat (bound root)’, [tɑ]

‘transmit (bound)’, [pi] ‘?utensil’, [me], nominal suffix) or [Hʁo-Lnbɚ] ‘bicycle’ (< [HLʁo]

‘kick, step on’, [HLnbɚ] ‘horse’).

3. Phonology, phonetics and tone system

Lizu has a simple syllabic structure, conforming to the areal syllable type. It can be summarized as (C)(G)V, with an associated tone; where C stands for the initial consonant or consonant cluster; G stands for either of the two Lizu glides, -j- or -w-, both with a restricted distribution; and V stands for vowel; brackets indicate optional constituents. For example, [LHlje] ‘good’, [LHrwæ] ‘chicken’, [HLne] ‘thou, second person singular pronoun’, [HLæ] ‘I, first

person singular pronoun’.

3 The Chinese dialect of Mùlǐ tentatively belongs to the Chéngyú 成渝 subgroup of the Southwestern Mandarin

Lizu initial consonant clusters include (i) 14 nasal-stop and nasal-affricate clusters, e.g. [LHnde] ‘good, clear (of the sky)’, [HLndzɑ] ‘Chinese’; (ii) three bilabial-fricative and one

bilabial-retroflex cluster, viz. bʑ, pʑ, pɕ~pʰʑ and pʂ, e.g. [LHbʑæ] ‘develop’, [HLpɕæ~HLpʰʑæ]

‘sweep’, [LHpʑæ] ‘hang’, [Hpʂe-HLzæ] ‘young’; and (iii) five clusters of the bilabial stop or

nasal or of the voiced glottal fricative /ɦ/ with the alveolar approximant /r/ (the latter combination, viz. /ɦr/, always co-occurs with a nasal vowel), e.g. [Hde-Lbræ] ‘ignite’, [H de-Hpræ] ‘arrive’, [Hse-Lpʰræ] ‘timber’, [LHmræ] ‘tasty’, [LHɦræ̃] ‘obtain’.

I describe Lizu syllable structure in the traditional terms of initials and rhymes, where rhymes include a medial and a nucleus (nuclear vowel). Based on the areal syllable type, which is typically analyzed as commonly including the medials, -j-, -w-, and -r- (e.g. Written Tibetan; Old Chinese, Baxter 1992: 178-180; Lolo-Burmese, Bradley 1979: 117-119), I regard the Lizu glides -j- and -w- and the alveolar approximant /r/ in consonant clusters as medials. This unconventional approach—modern analyses of syllable structure disallow a separate medial node in a syllable—is adopted, as it allows to account for many patterns of phoneme distribution in modern Lizu as well as for many correspondences between Lizu, Lǚsū and Ěrsū, as discussed below.

This section consists of three parts. Part 1 (§3.1) sums up initial and rhyme inventories of Lizu (phonemes with their most common allophones) for the ease of comparison with those in Lǚsū (Huáng and Rénzēng 1991: 133-138) and Ěrsū (Sūn 1982: 242-247, 1983: 125-127). On the basis of these inventories, a new phonological analysis is proposed in Part 2 (§3.2). Part 3 (§3.3) describes Lizu tone system.

3.1. Initial and rhyme inventories of Lizu 3.1.1. Initials

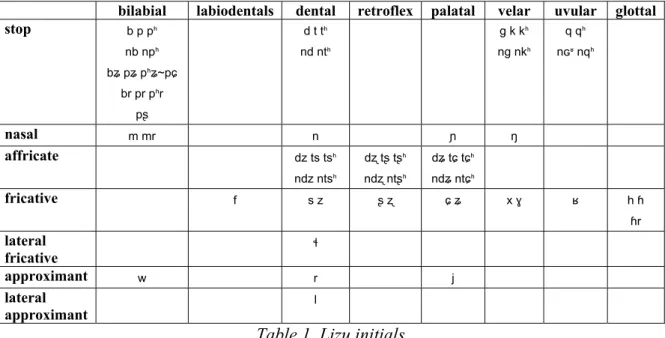

Table 1 presents Lizu initials (phonemes with their most common allophones). “n” in nasal-stop and nasal-affricate clusters stands for a homorganic nasal, i.e. m, n, ɳ, ɲ, ŋ and ɴ.

bilabial labiodentals dental retroflex palatal velar uvular glottal stop b p pʰ nb npʰ bʑ pʑ pʰʑ~pɕ br pr pʰr pʂ d t tʰ nd ntʰ g k kʰ ng nkʰ q qʰ nɢʶ nqʰ nasal m mr n ɲ ŋ affricate dz ts tsʰ ndz ntsʰ dʐ tʂ tʂʰ ndʐ ntʂʰ dʑ tɕ tɕʰ ndʑ ntɕʰ fricative f s z ʂ ʐ ɕ ʑ x ɣ ʁ h ɦ ɦr lateral fricative ɬ approximant w r j lateral approximant l

Table 1. Lizu initials

(i) the initial w- is sometimes realized close to the velar voiced fricative [ɣ], e.g. [HLwo]~[HLɣo]

‘pig’, [HLwo-Lke]~[HLɣo-Lke] ‘that’. Moreover, some of w-initial words in Lizu correspond to

ɣ-initial words in Ěrsū, e.g. [ɣu35] ‘pig’. The interplay between w- and ɣ- initials has also been

noted in Tosu (Meier, p.c.).

(ii) in addition to its variation with w-, ɣ- is also in interplay with the initial g-, when the latter is followed by [ɯ], e.g. [Hɣɯ-Lɲi]~[Hgɯ-Lɲi] ‘intestines’.

In sum, [ɣ] synchronically functions only as allophone of /w/ and /g/.

(iii) the combination of the initial ŋ- with an oral vowel is in free variation with that of the initial ɦ-, followed by a nasal vowel, e.g. [LHŋo] ~ [LHɦõ] for ‘bear’, [HLŋu] ~ [HLɦũ] for ‘cry’

(note also the Lizu word for ‘five’, [LHɦɑ̃], for a widely shared Tibeto-Burman cognate with

the velar nasal root-initial, cf. WT lnga).

(iv) [f] occurs only with the syllabic /v̩/, e.g. [Lfv̩-HLme] ‘tooth’, [Hfv̩-Lʙ̩] ‘onion’.

(v) uvulars:

Lizu has two uvular stops, [q] and [qʰ], one uvular fricative, [ʁ], and two uvular nasal-stop clusters, [nɢʶ] and [nqʰ], of which the former is strongly affricated.

Uvulars are generally held to be secondary development of the Sino-Tibetan velar series (Matisoff 2003: 20). From a comparative prospective, no uvulars are posited either for Ěrsū in Sūn (1982, 1983) or for Lǚsū in Huáng and Rénzēng (1991). Sūn (1982: 243), however, notes that a number of Ěrsū velars are realized as uvulars, especially in the speech of older speakers, but he reports having found no contrastive pairs.

In Lizu, the uvular stops [q] and [qʰ] contrast with the velar stops [k] and [kʰ] before /o/, e.g. [Hqo-Lqo] ‘hole’ (root /Hqo/) vs. [Lne-HLko] ‘put, place’ (root /ko/), and [Lqʰo-HLzɿ]

‘tadpole’ vs. [Hkʰo-Lje] ‘key’.

(vi) in addition to being initials, /w/, /r/ and /j/ can also function as medials, all three with a restricted distribution. The medial -r- clusters only with bilabial initials and the voiced glottal fricative ɦ- (the latter combination, viz. [ɦr], only occurs with nasal vowels), see examples above. The medial -j- clusters only with bilabial initials and the initial l-, e.g. [HLbje] ‘pile’,

[HLpje] ‘medicine’, [HLpʰje] ‘ice’, [Lmje-HLmje] ‘much, many’, [LHlje] ‘good’. The medial -w-,

on the other hand, has a broader distribution and can cluster with the initial r-, retroflexes, velars and uvulars, e.g. [LHrwæ] ‘chicken’, [HLʂwɑ] ‘mosquito’, [Hne-Lkwæ] ‘wither’, [kʰwæ]

‘big, large (bound root)’, [Hxwæ-Hmu] ‘yawn, gape’, [LHqwɑ] ‘thin, skinny’, [HLqʰwɑ] ‘lake,

see’. The co-occurrences of these three medials with vowels are discussed in the following section.

3.1.2. Rhymes

Table 2 summarizes Lizu rhymes (oral vowels with their most common allophones, as well as their combinations with the three medials, -w-, -r- and -j-).

i (ɿ/ʅ) y

e (ɯ), je

v̩ ŋ̍ u

ɚ o

æ, jæ, ræ, wæ ɑ, wɑ

Table 2. Lizu rhymes

All 8 oral vowels in Table 2 have nasal counterparts, viz. ĩ ỹ ẽ æ̃ ɚ̃ ũ õ ɑ̃. These nasal vowels co-exist in the phonemic system of Lizu with a rich inventory of nasal-stop and nasal-affricate clusters, viz. nb npʰ nd ntʰ ng nkʰ ndz ntsʰ ndʐ ntʂʰ ndʑ ntɕʰ nɢʶ nqʰ. This coexistence effectively poses a problem of consistently distinguishing between nasalization as the feature of the vowel (nasal vowels) and nasalization as the feature of the initial (stop and nasal-affricate clusters) in polysyllabic words with a nasal-stop or nasal-nasal-affricate cluster in word non-initial position, e.g. ‘foolish, stupid’: [Hdĩ-Lbæ] or [Hdi-Lnbæ]. This issue can be easily

solved in those cases, where the vowel of the root can be isolated, i.e. in words consisting of free roots, e.g. [Hhẽ-HLnbo] ‘bamboo rainhat’ (< [HLhẽ] ‘bamboo’, [LHnbo] ‘hat’); or those that

can be reduplicated, e.g. [Hdĩ-Hdĩ-Hbæ-Hbæ] ‘very stupid’, hence [Hdĩ-Lbæ] ‘foolish, stupid’.

Conversely, it is more complex in the case of words consisting of bound roots, e.g. [Htæ̃-Htsʰi]

or [Htæ-Hntsʰi] ‘pen, stick’; in which case I have chosen to treat nasalization as the feature of

the initial, e.g., I transcribe the word ‘pen, stick’ as [Htæ-Hntsʰi].

The following observations regarding Lizu rhymes are in order:

(i) [ɿ] and [ʅ] are allophones of /i/ after dental and retroflex fricatives, respectively, e.g. [HLzɿ]

‘son’, /Hzi/; [LHndʐɿ] ‘skin’, /ndʐi/

(ii) [ɯ] is an allophone of /e/ after velars, e.g. [HLkɯ] ‘eagle’, /Hke/

(iii) in native Lizu words, [y] appears only after the initial l-, as in [LHly] ‘rob, loot’; and its

nasal counterpart [ỹ] only after the initial h-, as in [Hhỹ-Hso] ‘the next morning’ or [Hde-Lhỹ]

‘fragrant, tasty’. In addition, [y] appears in a number of Chinese loanwords, e.g. [LHy] ‘fish’

(yú 鱼).

(iv) in addition to vowels, the following consonants can function as syllable nucleus in Lizu: (a) /ŋ̍/, as in [HLtŋ̍] or [HLkŋ̍] ‘seven’ and [Lkŋ̍-LHræ] ‘snot’; and (b) the voiced fricative /v/, e.g.

[LHv̩] ‘buy’, [Hkʰe-Lv̩] ‘wear’, [Hkʰv̩-Hpʰo] ‘inside’. Similar to the syllabic /v/ in Yǒngníng Nà

(Michaud forthcoming), /v/ in Lizu can only occur as a rhyme. Consequently, /v̩/ is hereafter used without the IPA under-stroke diacritic / ̩/ in my transcriptions, viz. /v/.

(v) the syllabic /v/ has a tendency towards trilling after bilabial and dental stop initials and is realized in that environment close to [ʙ̩], e.g. [Hfv-Lʙ̩], /bv/, ‘onion’; [Lse-HLpʙ̩], /pv/, ‘tree’;

[HLdʙ̩], /dv/, ‘plumage’; [HLtʙ̩], /tv/, ‘beans’. Overall, the presence of /v/ in the vowel inventory

and its tendency to trill after bilabial and dental stops are areal features, common also in Yǒngníng Nà (Michaud forthcoming), and Northern Ngwi (Bradley 1979: 70).

(vi) Lizu appears to contrast /v/, /u/ and /o/, e.g. [HLmv] ‘fur, animal hair’, [HLmu] ‘make’,

[HLmo] ‘tomb’; [LHnqʰv] ‘silk’, [LHnqʰu] ‘hook’ and [LHnqʰo] ‘lock’. Overall, it is plausible that

the presence of /v/ in the phonemic system of Lizu is due to areal convergence, whereas the /u/-/o/ contrast is inherent to the system: a hypothesis to be tested in future fieldwork.

(vii) in terms of medial-vowel sequences, -j- has the broadest distribution (see Table 2); -w- co-occurs only with low vowels and -r- only with /æ/.

(viii) the rhyme /wæ/, e.g. [LHngwæ] ‘rain’, is to be distinguished from the combination of the

vowels /u/ and /æ/, i.e. [uæ], in past forms of verbs with the root vowel /o/ or /u/. (Past forms of verbs in Lizu are formed by adding the past marker /æ/ to the verb stem, see §3.3.1 and 5.2. The addition of the past marker /æ/ causes the preceding vowel to unround.) For example, [LHngo] ‘lift’ + the past marker /æ/ > [LHnguæ] ‘lifted’. To distinguish between the

rhyme /wæ/ and the combination /u/+/æ/, I use a dot to separate the vowel of the root and the past marker in the latter case, e.g. [LHngu.æ] ‘lifted’.

3.2. Phonological analysis

The consonant and rhyme inventories of Lizu and their interrelationships as outlined in §§3.1.1-3.1.2, present a complex and somewhat irregular picture (e.g. co-existence of many nasal vowels with many nasal-stop and nasal-affricate clusters, complex distribution patterns of the medials). In this section, based on the observed patterns of phoneme distribution in Lizu as well as on some comparisons between Lizu, Lǚsū and Ěrsū, I propose a new phonological analysis leading to a more economic and better balanced system, which hopefully also throws light on some diachronic developments in Lizu phonology.

The first observation which can be made about the initial and rhyme inventories of Lizu as presented in §3.1.1 and §3.1.2, respectively, is that there is a considerable unevenness between bilabial initials and the initial l- and the rest of the system in terms of co-occurrence with the three Lizu medials -j-, -r- and -w-, more precisely:

(i) The medial -r- clusters only with bilabial initials

(ii) The medial -j- clusters only with bilabial initials and the initial l-

(iii) The medial -w- does not cluster with either bilabial initials or the initial l-, but can cluster with a wide range of other initials

(iv) In addition, only bilabials can form clusters with fricatives and retroflexes, viz. bʑ, pʑ, pɕ~pʰʑ and pʂ.

Overall, bilabial initials and the initial l- regularly contrast rhymes /e/ and /je/, i.e. with and without the medial -j-, e.g. [Hbe-Lbe] ‘climb’ vs. [HLbje] ‘pile’; [Lkʰe-HLpe] ‘stick, glue’ vs.

(In addition, the phoneme [y], which co-occurs only with the initial l-, is likely to have developed through diphthongization of /i/ (see footnote 2) and can consequently be analyzed as a diphthong, viz. /ju/. Hence, words with the initial l- also regularly contrast /u/ and /ju/, e.g. [Hlu-Hlu] ‘bark (of dogs)’ vs. [LHlju] ‘white’. [ỹ] in words with the initial h- is discussed

below.) Conversely, bilabial initials do not co-occur with the rhyme /jæ/. This gap in the distribution can be explained, if the three Lizu bilabial-palatal clusters [bʑ], [pʑ] and [pʰʑ~pɕ] are taken into account and considered as developed from bilabial-medial -j- clusters. Hence, Lizu [bʑæ] is here analyzed as /bjæ/; [pʑæ] as /pjæ/; [pʰʑæ~pɕæ] as /pʰjæ/, so that /pɕæ/ developed from /pʰjæ/ through the following stages: [pɕæ]<[pʰʑæ]</pʰjæ/.

Overall, I propose that the range of options synchronically observed on Lizu bilabials gives an indication of the range of possibilities available on all initial series of the system at an earlier stage. This entails that the medials -j- and -r- used to have a more balanced distribution within the system and could cluster with all initial series and possibly co-occur with all oral vowels. Conversely, the cross-linguistically common phonological changes that these two medials triggered (palatalization in the case of the medial -j- and retroflexion in the case of the medial -r-) led to the phonemicization of palatals and retroflexes in modern Lizu, subsequently obscuring the presence of -j- and -r- in some environments. The following set of hypotheses is built on this assumption.

Distribution of the medials -j- and -r-

Given that modern Lizu has no combinations of dentals and velars with the medial -j- or the high front oral vowel /i/, I propose that Lizu palatals developed from dentals and velars, when followed by the medial -j- and the high front vowel /i/, respectively.4 This can be seen from comparisons between Lizu and Lǚsū, where velars followed by the rhyme /i/ have escaped palatalization: ‘ladder’: Lizu [Hɬe-Ltɕi], Lǚsū [ɬi33ki53]; ‘ask’: Lizu [Hme-HLntɕʰe], Lǚsū

[te53me53nkʰi31]; ‘thunder’: Lizu [Hme-Hdʑe], Lǚsū [me53gi53]; ‘(cow) pen’: Lizu [Lzu-L ŋu-HLdʑe], Lǚsū [ŋu53gi53].

Furthermore, I propose that retroflexes in modern Lizu developed from dentals and velars, both clustered with the medial -r-, in a fashion similar to that of the development of palatals. This is again supported by comparisons with Lǚsū, where the medial -r- is re-analyzed as rhoticization of the following vowel: ‘star’: Lizu [HLtʂɿ], Lǚsū [kəɹ35]; ‘gall

bladder’: Lizu [LHtʂɿ], Lǚsū [kəɹ53]; ‘skin’: Lizu [LHndʐɿ], Lǚsū [ngəɹ35]; ‘tail’: Lizu [H me-Lntʂʰo], Lǚsū [mu33kəɹ53].

By analogy with the development of the [pɕ] cluster from an initial-medial cluster, i.e. /pʰj/; I take the cluster [pʂ] to derive from the cluster /pʰr/ through the following stages: [pʂ]>/pʰʐ/>/pʰr/. The name of the Prinmi group in Lizu, Lizu [HLpʂɿ] from Prinmi [pʰʐə̃55 mi55]

(Lù 2001: 1), supports this assumption.

Let us now turn to the distribution of -r- with bilabial initials. Notably, the medial -r- synchronically appears only with the low front vowel /æ/; whereas the rhyme inventory of

4 Synchronically attested combinations of dentals with the high front nasal vowel /ĩ/, as in [Hdĩ-Lbæ] ‘foolish,

Lizu has one rhotic vowel, viz. [ɚ], e.g. [Hpɚ] ‘grain’. Given the present assumption of the

originally even distribution of the medial -r- in the phonemic system of Lizu, I presume that the rhotic vowel has developed in connection with the medial -r-. (That this is the case is overall supported by the appearance of [ɚ] in stable Sino-Tibetan cognates with this medial, such as [HLnbɚ] ‘horse’ (*mraŋ Matisoff 2003: 654) or [HLbɚ-Lɚ] ‘snake’ (WT sbrul).)

Given the assumption of the development of the rhotic vowel [ɚ] in connection with the medial -r- as well as the synchronic distribution of -r- with the low front vowel only, [ɚ] is likely to stand for a range of possible combinations of this medial with high and mid-high vowels, viz. /-ri/, /-re/, /-ru/; all missing in modern Lizu. Provided that it is synchronically impossible to ascertain the exact provenance of [ɚ] in each particular case, whereas it is to be expected that it is a combination of the medial -r- with a high vowel, I use the unspecified vowel /ə/ to stand for this high vowel and re-write [ɚ] as [rə] in my transcriptions, e.g. [HLnbɚ

] ‘horse’ is hereafter re-written as [HLnbrə].

So far, we have established that the rhotic vowel [ɚ] developed from combinations of the medial -r- with high vowels. Synchronically, the medial -r- co-occurs with the low front vowel /æ/. In view of the present assumption of an even distribution of the medial -r-, clustering with all types of initials and combining with all oral vowels, the absence of sequences of the medial -r- with mid-low and low back vowels requires an explanation.

In this connection, I propose that the affrication in the uvular cluster [nɢʶ] is an indication of the presence of the medial -r-. In other words, the cluster [nɢʶ] is in fact an ealier /ngr/, developed through the intermediate stage of affrication. This is again supported by comparisons with Lǚsū, e.g. ‘kill (a human being)’: Lizu [HLnɢʶ ɑ], Lǚsū [ngaɹ53]. This

development further suggests that other uvular phonemes in Lizu also derive from combinations of velars with the medial -r-, again, through the intermediate stage of affrication, i.e. [q]<[qʶ]</kr/ and [qʰ]<[qʰʶ]</kʰr/; with the subsequent loss of affrication and phonemicization of uvulars. The synchronically observed uvular-velar contrast before /o/, e.g. [Hqo-Lqo] ‘hole’ vs. [Lne-HLko] ‘put, place’, and [Lqʰo-HLzɿ] ‘tadpole’ vs. [Hkʰo-Lje] ‘key’; is,

hence, that between a plain velar and a velar-medial -r- cluster, i.e. /k/ vs. /kr/. That uvular stops and uvular velars synchronically do not contrast before other vowels in Lizu points to (i) an earlier development of the rhotic vowel [ɚ], which further did not contribute to the process of retroflexion of the initials (e.g. Lizu has [kɚ], as in [Hkɚ-Hwæ] ‘spider’, but no [qɚ]) as

well as (ii) to the re-analysis of the velar vs. velar-medial -r- contrast as that of the frontness vs. backness of the vowel, hence Lizu /kra/ developed into modern [qɑ]; whereas /ka/ developed into modern [kæ].

Overall, the fate of the medial -r- after velar initials is different in Lizu, Lǚsū and Ěrsū, leading (i) to the development of a separate uvular series in Lizu; (ii) to the development of rhotic vowels with the subsequent loss of rhoticization in some cases in Lǚsū, and (iii) retroflexion in Ěrsū. Consider some examples: ‘steelyard’: Lizu [HLqɑ] (/Hkrɑ/), Lǚsū [kaɹ55]

and Ěrsū [tʂɛ55]; ‘child’: Lizu [Hjæ-HLqɑ] (/Hkrɑ/), Lǚsū [ja53ka53] and Ěrsū [jɑ55dʐɛ55];

Parallel to the development of Lizu uvular stops from velars clustered with the medial -r-, the uvular fricative [ʁ] in modern Lizu is likely to derive from a cluster of the medial -r- with a velar fricative, either /x/ or /ɣ/, so that /xr/ stands for both possibilities in my transcriptions. This is again supported by comparisons between Lizu, Lǚsū and Ěrsū, e.g. ‘needle’: Lizu [HLʁɑ] (/Hxrɑ/), Lǚsū [ɣɯ35/ɣa35], Ěrsū [xaɹ55].

Allophones of /x/ and /ɣ/

Building up on the assumption of the presence and even distribution of the medials -j- and -r- in the phonemic system of Lizu, I propose the following sets of allophones for the velar fricatives /x/ and /ɣ/.

Allophones of /x/:

(a) [f] before the syllabic /v/, e.g. [Lfv-HLme] ‘tooth’, /xv-me/; [Hfv-Lbv] ‘onion’, /HLxv-bv/ (note

a similar development in Yǒngníng Nà, Michaud forthcoming)

(b) [h] before nasal front vowels, e.g. [Ltsʰe-Hhẽ] ‘this year’, /xẽ/; [Hde-Lhỹ] ‘fragrant, tasty’,

/Hxjũ/

(c) [ɕ] before the vowel -i- and the medial -j- (d) [x] in all other cases.

Allophones of /ɣ/:

(a) [ɦ] clustered with the medial -r- before nasal vowels, [LHɦrə̃] ‘mushroom’, /ɣrə̃/; [LHɦræ̃]

‘obtain’, /ɣræ̃/

(b) [ʑ] before the high front vowel -i- and the medial -j-

Finally, modern Lizu [ʁ] is the allophone of either /x/ and /ɣ/, followed by the medial -r- and an oral vowel.

Additionally, the initial w- (as in [HLwo]~[HLɣo] ‘pig’), followed by an oral vowel, is

also tentatively an allophone of /ɣ/. Given the marginal status of the phoneme /ɣ/ in modern Lizu as described in §3.1.1 and the unclear conditioning factors responsible for its allophonic variation with /w/, I keep /w/ unchanged in my transcriptions.

Nasal vowels and nasal-stop and nasal-affricate clusters

/x/ and /ɣ/ taken each as one phoneme (in the totality of its allophones as above), co-occur with both oral and nasal vowels, e.g. /xi/ ([ɕi]) vs. /xĩ/ ([hĩ]); /xe/ ([xe]) vs. /xẽ/ ([hẽ]); /xæ/ ([xæ]) vs. /xæ̃/ ([xæ̃]); /xu/ ([xu]) vs. /xũ/ ([xũ]) and /xju/ ([ɕu]) vs. /xjũ/ ([hỹ]). This suggests that the oral-nasal contrast in vowels is inherent to the system and was probably observed on most initials at an earlier stage. Notably, in connection to the pairs /xi/ ([ɕi]) vs. /xĩ/ ([hĩ]) and /xju/ ([ɕu]) vs. /xjũ/ ([hỹ]), it appears that after the phonetic difference between the initials ɕ-and h- was phonemicized, (i) the nasal vs. non-nasal contrast on the vowel was lost in the new environment (i.e. Lizu has [ɕi], but no [ɕĩ], and [hĩ], but no [hi]), and (ii) the nasal vs.

non-nasal contrast on the vowel was transphonologized as a contrast of initials instead (cf. similar developments in the Nàxī of Lìjiāng, Michaud 2006: 35-38). The same processes, viz. the loss of the nasal vs. non-nasal contrast on vowels and its transphonologization into the nasal vs. non-nasal contrast of initials, are likely to have affected a broad range of initials, contributing to the proliferation of nasal-stop and nasal-affricate clusters in Lizu, e.g. [Hntɕʰe] ‘glue’ from

WT spyin, tentatively through the intermediate stage /tɕʰẽ/ in the Tibetan donor dialect. Conversely, the nasality of the vowel blocked palatalization of the initial in some cases, e.g. when followed by the high front vowel /i/, with the result that while modern Lizu has no combinations of dentals with the oral high front vowel /i/, it has combinations of dentals followed by the nasal high front vowel /ĩ/, e.g. [Hdĩ-Lbæ] ‘foolish, stupid’.

Distribution of the medial -w-

Finally, let us turn to the distribution of the medial -w-, which is synchronically attested with a wide range of initials, viz. /r/, retroflexes, velars and uvulars. Provided that Lizu uvulars are allophones of velars, the medial -w- appears to cluster predominantly with velars. This suggests its origin in labialized velars, i.e. kʷ, kʰʷ, gʷ, xʷ, ɣʷ. The instances of the appearance of the medial -w- with the retroflex series in modern Lizu, e.g. [LHʂwɑ] ‘wasp’ and [LHtʂwɑ]

‘mosquito’, can be explained as derived from labialized velar initials clustered with the medial -r-, i.e. /kʷr/, /kʰʷr/, /gʷr/ etc. The co-occurrence of the initial /r/ with the medial -w-, viz. [rw]; on the other hand, is here analyzed as the labialized initial /ɣʷ/, based on Lǚsū [ɣ ua35], e.g. [LHrwæ] ‘chicken’ is hereafter re-written as [LHɣʷæ]. Combinations of labialized

velars with high initials, missing in the system, are currently left unexplained.

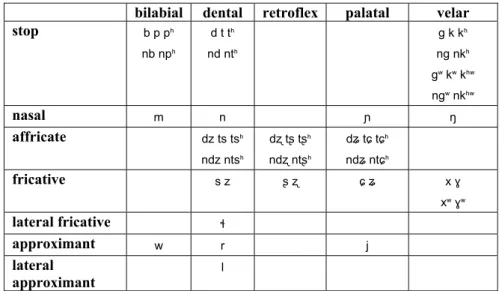

The phonemic inventory of Lizu as used in my transcriptions is summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

bilabial dental retroflex palatal velar stop b p pʰ nb npʰ d t tʰ nd ntʰ g k kʰ ng nkʰ gʷ kʷ kʰʷ ngʷ nkʰʷ nasal m n ɲ ŋ affricate dz ts tsʰ ndz ntsʰ dʐ tʂ tʂʰ ndʐ ntʂʰ dʑ tɕ tɕʰ ndʑ ntɕʰ fricative s z ʂ ʐ ɕ ʑ x ɣ xʷ ɣʷ lateral fricative ɬ approximant w r j lateral approximant l

i e, je æ, jæ, ræ v̩ ŋ̍ u ə rə o, jo, ro ɑ, rɑ

Table 4. Lizu rhymes: New analysis

Lizu has 7 nasal vowels, viz. ĩ, ẽ, æ̃, ə̃, ũ, õ, ɑ̃. The syllabic /v/ is likely to be a recent addition to the system, initially introduced as an allophone of /u/; /v/, therefore, does not have a nasal counterpart. Overall, /æ/ and /ɑ/ are likely to derive from an earlier /a/, but the exact conditioning factors of this development require further investigation; the distinction between the two, viz. /æ/ vs. /ɑ/, is therefore kept in my transcriptions.

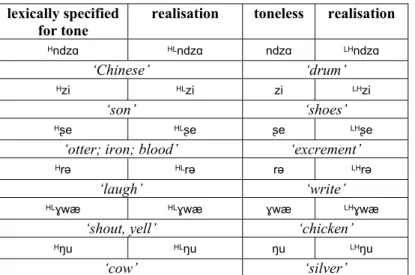

3.3. Tone system

Lizu has a restricted tone system, which can be described in terms of just one tone value, viz. /H/. The tonal system of Lizu is subject to constraints of obligatoriness (at least one tone per tone domain), privativity (the presence of tone versus its absence) as well as metrical constraints (tone is subject to reduction in compounding or when out of focus) (cf. Voorhoeve 1973, quoted from Hyman 2007: 661; Hyman 2006, 2007; Evans 2008).

The one tone value described here for Lizu, /H/, has two realizations: (i) [H] in connected speech and (ii) [HL] in careful speech or in isolation. Furthermore, the single Lizu tone value /H/ distinguishes between three different tones:

(i) a lexical tone; assigned to words in the lexicon. Hence, Lizu monosyllables can be divided into (a) those lexically specified for tone and (b) toneless (including both roots and affixes); (ii) a post-lexical tone, assigned to the right edge of underlyingly toneless words, to satisfy the obligatoriness constraint; and

(iii) dynamic accent or stress, realized as [H] tone and assigned to the prominent constituent within a phrase, consisting of three or more words.

In underlyingly toneless monosyllabic words, the post-lexical tone is attached to the right edge of the syllable, creating a rising contour, viz. [LH]. Hence, the contrast between the presence or absence of tone on monosyllables is realized as [H]~[HL] versus [LH], as in the following examples in Table 5:

lexically specified

for tone realisation toneless realisation Hndzɑ HLndzɑ ndzɑ LHndzɑ

‘Chinese’ ‘drum’

Hzi HLzi zi LHzi

‘son’ ‘shoes’

Hʂe HLʂe ʂe LHʂe

‘otter; iron; blood’ ‘excrement’

Hrə HLrə rə LHrə

‘laugh’ ‘write’

HLɣwæ HLɣwæ ɣwæ LHɣwæ

‘shout, yell’ ‘chicken’

Hŋu HLŋu ŋu LHŋu

‘cow’ ‘silver’

Table 5. Minimal pairs of monosyllabic words, lexically specified for tone and toneless

In underlyingly toneless words of two syllables or more, the post-lexical tone is assigned to the final syllable of the unit, e.g. [Lmu-Ltsi Ljæ-HLkrɑ] ‘kitten’ (< [Lmu-HLtsi] ‘cat’, [Ljæ-HLkrɑ]

‘child’).

Overall, Lizu is phonologically monosyllabic, so that all units of two syllables or more (words and phrases) are formed from combinations of monosyllabic morphemes, which are of two types: (i) free and bound roots (the majority), e.g. /zo/ ‘third person singular animate pronoun’, /Htʂʰv/ ‘earth’, /lje/ ‘good’; and (ii) affixes. Lizu has few affixes, of which most are

synchronically unproductive. Some important derivational suffixes are:

(i) animal gender suffixes: (a) the feminine nominal suffix /-mæ/ and (b) the male nominal suffixes /-npʰe/ and /-bv/, e.g. /Htɕʰe/ ‘dog’: [Htɕʰe-Lnpʰe] ‘(male) dog’ vs. [Htɕʰe-Lmæ] ‘bitch’;

/mu-tsi/ ‘cat’: [Lmu-Ltsi-HLmæ] ‘female cat, pussycat’ vs. [Lmu-Ltsi-HLbv] ‘male cat, tom’;

(ii) the diminutive suffix /-je/, e.g. [Lɣʷæ-Hje] ‘chicken’, possibly also in [Hʑe-Hje] ‘daughter’;

(iii) the nominal suffix /-me/, e.g. [Hse-Ldzu-Lme] ‘log’; [Lnæ-Hnkʰæ-Lme] ‘sky’; [Hʐæ-Ltɑ-L pi-Lme] ‘mobile phone’.

Prefixes include: (i) the nominal vocative prefix /æ-/ (in kinship terms), e.g. [Hæ-Hmæ]

‘mother’, [Hæ-Hpæ] ‘father’; (ii) four directional and aspectual prefixes in verbs and

adjectives: /de-/ ‘upward’, /ne-/ ‘downward’, /kʰe-/ ‘inward’ and /tʰe-/ ‘outward’, e.g. [L de-HLtsʰv] ‘fat, become fat’, [Lne-HLbrə] ‘tired’, [Lkʰe-HLli] ‘enter, come inside’, [Ltʰe-Hnkʰæ] ‘sell’;

and (iii) the comparative prefix in adjectives /jæ-/, e.g. [Ljæ-HLlje] ‘better’ (< /lje/ ‘good’).

Similar to its neighboring languages (e.g. Shǐxīng, Chirkova and Michaud 2008), Lizu has a strong tendency towards disyllabicity in its lexicon through affixation, compounding and reduplication, so that the majority of Lizu words are disyllabic, e.g. [Hʑe-Hje] ‘daughter’.

‘ironsmith’, literally, ‘one who forges iron’ (< /Hʂe/ ‘iron’, /tsv/ (bound) ‘beat, knock’, /sv/

agentive nominalizer), or [Lmu-Ltsi Ljæ-HLkrɑ] ‘kitten’ (< /mu-tsi/ ‘cat’, /jæ-krɑ/ ‘child’).

Tone patterns in units of two syllables or more (both words and phrases) are assigned based on the nature of the unit and its composition:

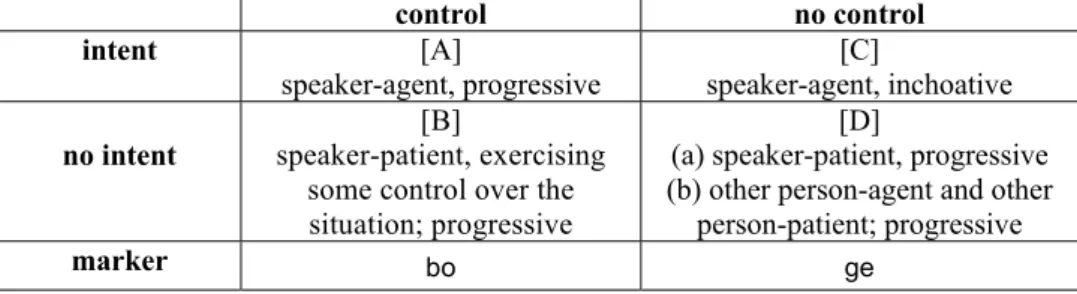

(i) a content word (lexical item, formed through affixation or reduplication) or a phrase consisting of a word followed by a clitic. Clitics or function words in Lizu are toneless, e.g. the progressive markers /bo/ and /ge/. Clitics attach to their host words, with which they form a single tone pattern, as shown below.

(ii) a compound, including (a) words formed through compounding and (b) phrases, consisting of two words (modifying noun-noun and noun-adjective compounds; object-verb phrases)

(iii) a phrase, consisting of three or more words

Derivations with the lexical tone are restricted to the first and second cases, the third case being the domain of intonation (stress).

3.3.1. Tone pattern derivation in content words and phrases consisting of a word and a clitic

The following tone rule operates in the case of content words, formed through affixation and reduplication; and combinations of a word and a clitic:

The tone of the root of the word or the tone of the word in the case of combinations of a word and a clitic determines the tone pattern of the output unit by adjusting to the number of syllables in the output unit from left to right.

For example, in verbs formed through prefixation (with one of the directional prefixes): if the verb root is lexically specified for tone, the resulting tone pattern of the word is [HL], e.g. [Hne-Lko] ‘wither’ (root /Hko/), [Hde-Lntsʰæ] ‘lead (cow)’ (root /Hntsʰæ/). If, on the other hand,

the tone of the verb root is toneless, the tone pattern of the resulting compound is [LH], e.g. [Lne-Hko] ‘put’ (root /ko/), [Lde-Hntsʰæ] ‘itch’ (root /ntsʰæ/). Consider also some examples of

nouns and verbs formed through affixation and reduplication: [Hɲi-Lme] ‘sun’, [Lxv-HLme]

‘tooth’; [Hkʰv-Lpʰo] ‘inside’, [Lɲo-HLpʰo] ‘outside’, [Hlæ-Llæ] ‘roll, tumble’, [Ltʂʰæ-HLtʂʰæ]

‘magpie’. Consider also some combinations of a word and a clitic: (2) /Hʂe/ ‘otter’ + the genitive particle /ji/ > [Hʂe=Lji] ‘of the otter’

(3) /zo/ ‘third person animate singular pronoun’ + the genitive particle /ji/ > [Lzo=Hji] ‘his, her’

Two Lizu clitics, the nominal animate object marker /æ/ and the verbal past marker /æ/ (detailed in §4.1.2 and §5.2, respectively) deserve a special note. Both fuse with their host word, extending the root of the verb stem by one vowel, e.g. [Lne-LHdzi.æ] ‘ate’ (< /dzi/ ‘eat’).

verbal past marker /æ/ merge with it in one lengthened vowel, e.g. [Lne-LHdʐæ.æ] ‘fell’ (<

[Hne-Ldʐæ] ‘fall’). Both markers thus create a contour tone on a monosyllable.

The nominal animate object marker creates a contour tone, depending on the tone of its host word, in accordance with the tone rule above. For example: [HLtʰe.æ] ‘to him’ (< /Htʰe/

distal demonstrative pronoun and third person singular pronoun), [Hʑe-Hje # Lne-LHtʰe.æ]

‘[tell] the two daughters’ (< /ne-tʰe/ ‘the two of’).

The past marker /æ/, on the other hand, always creates a rising [LH] contour on the verb stem, irrespective of its inherent tone. In [LH] verbs, the resulting contour is [L.LH], e.g. [Lne-LHdzi.æ] ‘ate’ (< /dzi/ ‘eat’), [Lde-LHŋu.æ] ‘cried’ (< /ŋu/ ‘cry, weep’). In [HL] verbs, on

the other hand, the resulting contour is [H.LH]. For example, [Hne-LHtɕʰe.æ] ‘drank’ (< /Htɕʰe/

‘drink’).

3.3.2. Tone pattern derivation in compounds (words and phrases, consisting of two content words)

The tone pattern in words formed through compounding and phrases consisting of two content words is determined by the following rule:

The tonal pattern of the unit is determined by the lexical tone of its first constituent.

If the first element is lexically specified for tone, the tone pattern of the resulting compound is [H.H]~[H.HL]. For example:

(4) /Hʂe/ ‘iron’ + /Hdʐi/ ‘pan’ > /Hʂe dʐi/ ([Hʂe Hdʐi]) ‘iron pan’

(5) /Hræ/ ‘yak’ + /ʂe/ ‘excrement’ > /Hræ ʂe/ ([Hræ Hʂe]) ‘yak excrement’

(6) /Hræ/ ‘yak’ + /HLme-ntʂʰo/ > /Hræ me-ntʂʰo/ ([Hræ Hme-HLntʂʰo]) ‘yak tail’

(7) /Hsi-nge/ ‘lion’ + /Hmv/ ‘fur’ > /Hsi-nge mv/ ([Hsi-Hnge HLmv]) ‘lion fur’

(8) /Hsi-nge/ ‘lion’ + /ndʐi/ ‘skin’ > /Hsi-nge ndʐi/ ([Hsi-Hnge HLndʐi]) ‘lion skin’

Conversely, if the first element is toneless, the tone pattern of the resulting compound is [LH], where [H] is the post-lexical tone. For example:

(9) /mu-tsi/ ‘cat’ + /Htɕo-rə/ ‘footprint’ > /mu-tsi tɕo-rə/ ([Lmu-Ltsi Ltɕo-HLrə]) ‘cat pawprints’

(10) /ku-rə/ ‘donkey’ + /ndʐi/ ‘skin’ > /ku-rə ndʐi/ ([Lku-Lrə HLndʐi]) ‘cat skin’

In the case of modifying noun-noun compounds, if this second constituent is of two or more syllables in length, Lizu dissimilates two adjacent [H] tones at the boundary between the two constituents of the unit by deleting [H] tone of the second constituent. Compare the following two compounds with the word [Hme-Lntʂʰo] ‘tail’:

(11) /Hnbrə/ ‘horse’ + /HLme-ntʂʰo/ ‘tail’ > /Hnbrə # me-ntʂʰo/, [Hnbrə Lme-HLntʂʰo] ‘horse tail’

(12) /Hsi-nge/ ‘lion’ + /HLme-ntʂʰo/ ‘tail’ > /Hsi-nge # me-ntʂʰo/, [Hsi-Hnge Lme-HLntʂʰo] ‘lion

3.3.3. Tone pattern derivation in phrases, consisting of three elements

In the case of phrases, consisting of three or more words, [H] tone is assigned based on the following rules:

(i) If a phrase contains one of the following elements: the question marker, the negation marker or the prohibitive marker, assign [H] tone to these elements, leaving the rest of the phrase unstressed.

For example:

(13) Hæ # Ltɕʰe=Hmæ=Lndʐu. vs.Hæ # Ldzi=Hmæ=Lndʐu.

Hæ Ltɕʰe=Hmæ=Lndʐu Hæ Ldzi=Hmæ=Lndʐu.

1SG drink=NEG=be.able 1SG drink=NEG=be.able

‘I can’t drink.’ (< /Htɕʰe/ ‘drink’) vs. ‘I can’t eat.’ (< /dzi/ ‘eat’)

(14) Hæ # Lne=Hmæ=Ltɕʰe. vs.Hæ # Lne=Hmæ=Ldzi.

Hæ Lne=Hmæ=Ltɕʰe Hæ Lne=Hmæ=Ldzi

1SG downward=NEG=drink 1SG downward=NEG=drink

‘I did not drink.’ (< /Htɕʰe/ ‘drink’) vs. ‘I did not eat.’ (< /dzi/ ‘eat’)

(15) Ha-Hmæ # Htʰæ=Ltʂʰv Ldʑi=Lge=Hne # tɕiu # Ltʂʰv=Hmæ=Lɲo#.

Ha-Hmæ Htʰæ=Ltʂʰv Ldʑi=Lge=Hne tɕiu Ltʂʰv=Hmæ=Lɲo.

VOC-mother PROH=open speak=N-CTRL=RLV CH: just open=NEG=dare

‘[The two daughters said to themselves, they can’t open the door, since] their mother had told them not to do so, and so they did not dare to open’ (< /Htʂʰv/ ‘open’)

(ii) If a phonological phrase contains none of the above elements, assign [H] tone to the first syllable of the phrase.

For example:

(16) Hne # Hxæ-Lte Ltɕʰe=Lbo? vs. Hne # Hxæ-Lte Ldzi=Lbo?

Hne Hxæ-Lte Ltɕʰe=Lbo Hne Hxæ-Lte Ldzi=Lbo

2SG what-?one drink=CTRL 2SG what-?one drink=CTRL

‘What are you drinking?’ (< /Htɕʰe/ ‘drink’) vs. ‘What are you eating?’ (< /dzi/ ‘eat’)

The application of these two rules in continuous speech yields long strings of [HL…L] sequences that reveal nothing of the underlying tones, thus conforming to the native speaker’s intuition that “Lizu has no tones”.

Overall, similar to Shǐxīng (Chirkova and Michaud 2008), Lizu distinguishes between lexical tone and the associated tone pattern derivation strategies in the lexicon, on the one hand, and stress and intonation in its grammar, on the other hand. As Lizu is phonologically

monosyllabic with a tendency towards disyllabicity, its lexicon and grammar overlap at the level of polysyllabic words and phrases that consist of two elements, since polysyllabic words in Lizu are phrase-like in their structure, and phrases consisting of two elements are word-like by virtue of their consisting of two elements, thus formally conforming to the two-morpheme prototype word in the lexicon. Conversely, while words are associated with a fixed tone pattern in the lexicon; phrases of two elements can avail themselves of the totality of tone pattern derivation strategies existing in Lizu (both lexical and phrasal), as illustrated by the following phrases with the word /HLme-ntʂʰo/ ‘tail’:

(i) word-like tone derivation: spreading of the tone of the first constituent: /Hræ/ ‘yak’ + /HLme-ntʂʰo/ > /Hræ me-ntʂʰo/ ([Hræ Hme-HLntʂʰo]) ‘yak tail’

(ii) juxtaposition of the two words, [H] tone dissimilation:

/Hnbrə/ ‘horse’ + /HLme-ntʂʰo/ ‘tail’ > /Hnbrə # me-ntʂʰo/, [Hnbrə Lme-HLntʂʰo] ‘horse tail’

(iii) phrasal stress:

/Hŋu/ ‘cow’ + /HLme-ntʂʰo/ ‘tail’ > [Hŋu Lme-Lntʂʰo] ‘cow tail’. 4. Nominal marking

4.1. Grammatical relations and case marking

The grammatical relations of subject and object are not grammaticalized in Lizu. Instead, its clause structure is based on the pragmatic relations of topical vs. focal material, in a fashion very similar to that in Chinese (as presented in LaPolla 1993, forthcoming; LaPolla and Poa 2001). This entails that (i) Lizu word order primarily serves to signal semantic and pragmatic factors rather than grammatical relations, and that (ii) interpretation of the speaker’s communicative intention relies on inference. The unmarked word order in Lizu is agent-initial (topical), as in the following example:

(17) Hke # LHɣʷæ # Lde-LHpjæ. Hke LHɣʷæ Lde-LHpjæ.

eagle chicken upward-catch.PST

‘The eagle caught a chicken.’

Overall, the semantic categories of “animate” and “inanimate” tend to be cross-linguistically associated with the semantic roles of agent and patient, respectively. Given the unmarked agent-initial (topical) word order in Lizu, the agent requires no special marking, even when non-prototypical (inanimate). (Overall, the topical status of an element can be signaled by the topic marker, as discussed in §4.1.1.)

In the case of topical patients, on the other hand, those which are non-prototypical, i.e. animate (and especially human), need to be marked by means of the animate object marker /æ/, as detailed in §4.1.2.

Other types of relationships of a noun to a verb encoded in Lizu by means of postpositions (analytic case markers) are:

(a) genitive, signaling alienable possession, part-whole relationship and other related meanings, /ji/;

(b) locative, coding location in a place (with inanimate nouns); and dative, indicating the beneficiary of an action, denoted by the verb (with animate nouns), both signaled by the marker /ke/ ‘at’ and ‘for’;

(c) instrumental, signaling the instrument with which the action in question is performed, /læ=mu/; and

(d) comparative, marking the standard of comparison with comparative adjectives, /pæ/. These markers are outlined in this order presently.

4.1.1. Topic marker /le/

The topical status of an element (either agent, patient or any other, non-core, argument of the verb, i.e. phrases indicating the physical or temporal location of the event) can be signaled by the topic marker /le/. Consider the following examples:

(i) topic=agent:

(18) Hntsʰo-Llo # Lmæ-Lmo Lbi=Hle # Lrə-Lke=Hke # Lkʰe-Hlo...

Hntsʰo-Llo Lmæ-Lmo Lbi=Hle Lrə-Lke=Hke Lkʰe-Hlo

man-eating woman-old DEF=TOP road-half=at inward-wait

‘As for the witch, she was waiting for the old mother halfway between the old mother’s parents’ house and her own house.’

(ii) topic=patient:

(19) Htsʰo-Hmo=Hbi=Hle # Hntsʰo-Llo # Lmæ-HLmo # Lne-LHdzi.æ.

Htsʰo-Hmo=Hbi=Hle Hntsʰo-Llo Lmæ-HLmo Lne-LHdzi.æ.

man-old=DEF=TOP man-eating woman-old downward-eat.PST

‘As for the old man, he was eaten by the man-eating witch.’ (iii) topic=location of the event in space:

(20) Lrə-Lke=Lke=Hle # Hntsʰo-Llo Lmæ-Lmo # Lkʰe-Llo=Hsæ…

Lrə-Lke=Lke=Hle Hntsʰo-Llo Lmæ-Lmo Lkʰe-Llo=Hsæ

road-half=at=TOP man-eating woman-old inward-wait=PRF

‘As for the place halfway between the old mother’s parents’ house and her own house, the witch had been waiting for the old mother there...’

(iv) topic=location of the event in time:

(21) Hjæ=Lji # Hjæ=Lji # Hkʰæ=Lle # Hku-Ltʰe #, Hntsʰo-Llo # Lmæ-HLmo...

Hjæ=Lji Hjæ=Lji Hkʰæ=Lle Hku-Ltʰe, Hntsʰo-Llo Lmæ-HLmo