HAL Id: hal-01228438

https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01228438

Submitted on 13 Nov 2015

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Differentiation in the Developing Spinal Cord

Valérie Mils, Stéphanie Bosch, Julie Roy, Sophie Bel-Vialar, Pascale

Belenguer, Fabienne Pituello, Marie-Christine Miquel

To cite this version:

Valérie Mils, Stéphanie Bosch, Julie Roy, Sophie Bel-Vialar, Pascale Belenguer, et al.. Mitochondrial Reshaping Accompanies Neural Differentiation in the Developing Spinal Cord. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2015, 10 (5), pp. e0128130. �10.1371/journal.pone.0128130�. �hal-01228438�

Mitochondrial Reshaping Accompanies

Neural Differentiation in the Developing

Spinal Cord

Valérie Mils1‡, Stéphanie Bosch1‡, Julie Roy1, Sophie Bel-Vialar1, Pascale Belenguer1‡,

Fabienne Pituello1‡, Marie-Christine Miquel1,2‡*

1 Universités de Toulouse, Centre de Biologie du Développement, CNRS UMR5547, Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France, 2 UPMC Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Sorbonne Universités, Paris, France ‡ VM, SB and FP are joint first authors on this work.

‡ PB and MCM are joint senior authors on this work. *marie-christine.miquel@univ-tlse3.fr

Abstract

Mitochondria, long known as the cell powerhouses, also regulate redox signaling and arbi-trate cell survival. The organelles are now appreciated to exert additional critical roles in cell state transition from a pluripotent to a differentiated state through balancing glycolytic and respiratory metabolism. These metabolic adaptations were recently shown to be concomi-tant with mitochondrial morphology changes and are thus possibly regulated by contingen-cies of mitochondrial dynamics. In this context, we examined, for the first time,

mitochondrial network plasticity during the transition from proliferating neural progenitors to post-mitotic differentiating neurons. We found that mitochondria underwent morphological reshaping in the developing neural tube of chick and mouse embryos. In the proliferating population, mitochondria in the mitotic cells lying at the apical side were very small and round, while they appeared thick and short in interphase cells. In differentiating neurons, mi-tochondria were reorganized into a thin, dense network. This reshaping of the mimi-tochondrial network was not specific of a subtype of progenitors or neurons, suggesting that this is a general event accompanying neurogenesis in the spinal cord. Our data shed new light on the various changes occurring in the mitochondrial network during neurogenesis and sug-gest that mitochondrial dynamics could play a role in the neurogenic process.

Introduction

Mitochondria are not only key energy-generating organelles that participate in numerous bio-synthetic and metabolic pathways, but also crucial regulators of apoptosis [1]. Recent studies in stem cells demonstrated that mitochondria also play critical roles in cell state transition. Using in vitro models, it was indeed reported that the transition from a pluripotent to a differentiated state is reversible and partly controlled by the balance between glycolytic and respiratory me-tabolism [2,3]. Embryonic and adult pluripotent stem cells are characterized by a high activity

OPEN ACCESS

Citation: Mils V, Bosch S, Roy J, Bel-Vialar S, Belenguer P, Pituello F, et al. (2015) Mitochondrial Reshaping Accompanies Neural Differentiation in the Developing Spinal Cord. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0128130. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128130 Academic Editor: Francisco J. Tejedor, Instituto de Neurociencias, CSIC and UMH, SPAIN

Received: October 20, 2014 Accepted: April 22, 2015 Published: May 28, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Mils et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of theCreative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement: All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding: This work was funded by French CNRS, perennial grants (http://www.cnrs.fr/), French Université Toulouse 3, perennial grants (http://www. univ-tlse3.fr/), and French AMMI, grant 5841174 (http://www.association-ammi.org/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

of glycolytic enzymes accompanied by a low mitochondrial mass and mtDNA content [4,5]. This maintenance of a glycolytic state in progenitors preserves them from oxidative damage and contributes to committed differentiation [2,6]. The later switch to oxidative phosphoryla-tion better fits the high energy demand of differentiating cells [2]. Accordingly, repression of oxidative metabolism and activation of glycolysis are an obligatory steps for adult cells repro-graming into iPS [3,7,8]. Of recent interest, mitochondrial morphology changes come with these reversible metabolic adaptations and are thus possibly regulated by contingencies of mi-tochondrial dynamics [4,9].

The plasticity of the mitochondrial network relies on fission and fusion processes of outer and inner membranes that control mitochondrial morphology. When fission prevails, mito-chondria appear as dots, whereas when fusion predominates, mitomito-chondria form a filamentous and interconnected network. Furthermore, this mitochondrial dynamics allows immediate ad-aptation of the organelles to energetic needs, keeping mitochondria in good health by restoring or removing damaged organelles or precipitating apoptosis in cases of severe defects [10,11].

Mitochondrial dynamics results from the balance between the opposing forces of two dis-tinct machineries: one involving Mitofusins 1 and 2 (MFN1/2) and OPA1 for fusion and the other involving DRP1 for fission. Knocking out DRP1 or MFN1/2 genes, as well as homozygous OPA1 mutations, in mouse models induces midgestation embryonic lethality [12–16], demon-strating the major contribution of mitochondrial dynamics to development. However, while this regulatory process is common to many cell types, the association of OPA1 and MFN2 mu-tations with severe human neuropathies underlines the singular importance of mitochondrial dynamics in neurons [17,18]. Accordingly, conditional brain-specific DRP1 or MFN2 ablation in mice led to numerous defects in central nervous system development [15,16,19]. Neural cell-specific DRP1-/-mice display a smaller forebrain [15] and a smaller cerebellum, with completely smooth surfaces [16]. Furthermore, targeted deletion of DRP1 induced neurodegeneration in post-mitotic Purkinje cells [20]. Conditional specific MFN2 knockout led to massive post-natal Purkinje cell degeneration [19] and a severe loss of dopaminergic axonal projections in the stri-atum [21]. Finally, in both primary neurons from these mice models, neuritogenesis and synap-togenesis were impaired as they were in wild-type neurons in which effectors of mitochondrial dynamics were inactivated [15,20,22–25]. Altogether, these data suggest that mitochondrial dy-namics plays an essential role in neuronal differentiation and maturation.

Although evidence has begun to accumulate indicating that mitochondrial dynamics play a crucial role in the metabolic adaptations observed during the transition from a multipotent neural progenitor state to a differentiated state [4,9], a clear picture of the mitochondrial mor-phology changes accompanying the transition from proliferating progenitors to post-mitotic differentiating neurons is still missing. To fill this gap, we analyzed mitochondrial morphology using the paradigm of the developing neural tube of chick and mouse embryos at the prospec-tive spinal cord level. The spinal cord develops from a caudal stem zone containing uncommit-ted progenitors. Progenitors leaving the stem zone form the neural plate folding into the neural tube. The neural tube presents the advantage of a simple anatomical organization, with prolif-erating progenitors confined to the ventricular zone and differentiating neurons located at the periphery in the mantle zone. The ventricular zone is a pseudoepithelium where neural progen-itors display an elongated shape, with cytoplasmic connections both to the apical and basal sur-faces and nuclei performing oscillatory movements in phase with the cell cycle; i.e., interkinetic nuclear migration [26]. Upon the action of intrinsic and environmental signals, successive waves of neural progenitors are committed to a neuronal fate and exit the cell cycle. After their last mitosis at the apical side, these committed cells migrate out of the ventricular zone toward the mantle zone, where they differentiate into neurons. The molecular networks orchestrating these neurogenesis steps in the developing neural tube are well known [27,28] and numerous

markers allow identifying specific populations of neural progenitor cells and their correspond-ing neuronal subtypes.

Material and Methods

Embryos

All animal procedures were approved by the CNRS/Fédération de Recherche de Biologie de Toulouse Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (C2EA-01) under the protocol number 01024–01.7. The study was carried out in compliance with the European Policy on Ethics. Fer-tile hen eggs (from Gallus gallus), obtained from a local supplier (SCAL l’Isle Jourdain, France), were incubated at 38°C in a humidified chamber for the appropriate duration to yield embryos of Hamburger and Hamilton stages HH10 and HH20 (days E1.5 and E3.5 of development, re-spectively). C57Bl6 mouse embryos were isolated at E10 after detection of vaginal plugs.

Cell culture and mitotracker labeling

The HeLa cell line was purchased from the ATCC and cultured in DMEM (GIBCO) supple-mented with 10% FCS (Gibco). The DF1 cell line (UMNSAH/DF-1, ATCC CRL-12203, kind gift of Gaël Orieux, UPMC, Institut de la Vision, Paris, France) was cultured in DMEM supple-mented with 5% FCS and 5% chick serum (Gibco).

Mitochondria were labeled by incubation of the cells for 40 min with the Mitotracker Red probe (Invitrogen) at 0.1μM in culture medium. Cell nuclei were detected by Hoechst (Sigma) post-fixation labeling.

Electroporation

We used the Mito-DsRed expression vector that encodes DsRed2 protein (Discosomosa sp.) in fusion with the Mitochondrial targeting sequence of the human COX-subunit VIII, placed under the control of the pCMV promoter. In ovo electroporations were performed as previous-ly described [29] in E1.5 day-old chicken embryos. Electroporated eggs were incubated at 38°C for 2 days, and E3.5 embryos were processed for immunodetection.

Antibodies

Mitochondria were labeled by immunofluorescence using a mouse antibody specific for the human ATP-synthase (Molecular Probes) or a mouse antibody cocktail specific for the rodent OXPHOS complexes (MitoProfile Total OXPHOS, Mitosciences), or rabbit antibody specific for the human TOM20 mitochondrial protein (Santa-Cruz). Neural progenitor domains were labeled by immunofluorescence with either anti-Pax6 (Covance) or anti-Olig2 (Upstate Milli-pore) polyclonal antibodies, and mitotic progenitors with anti-P-H3 epitope antibodies (Up-state Millipore) or MPM2 (Mitotic Protein Monoclonal#2, Up(Up-state Biotechnology), which recognizes phosphorylated epitopes at the onset of mitosis. Antibodies directed against the neuronal beta3-tubulin (Sigma) or JC7 (a gift from J. Covault), were used to identify differenti-ating neurons. SR101-Phalloidin that labels cortical actin in the whole tissue was used to visual-ize overall cell morphology and DAPI (Sigma) to label nuclear DNA. For Western blot

experiments, antibodies against Actin (Chemicon), HSP60 (LK2, Sigma), OXPHOS (Mitos-ciences), DRP1 and OPA1 (BD-Bios(Mitos-ciences), and MFN2 (Abnova) proteins were used.

Primary antibodies were detected using either fluorochrome-tagged secondary antibodies coupled to Alexa 488, 596 or 647 for immunochemistry or HRP-conjugated secondary anti-bodies for Western blot experiments (Abcam).

Immunochemistry

Embryos were dissected and fixed for 3 h (chick) or 12 h (mouse) in a 3.7% v/v formaldehyde/ PBS solution. Briefly, floating 50-μm vibratome sections were immunostained by successive in-cubations with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, the secondary antibodies for 4 h at room temperature, and rinsing steps. Images were acquired on confocal SP2 or SP8 micro-scopes (Leica) using X20, X40, and X63 oil objectives.

For immunofluorescence analysis, HeLa and DF1 cells were seeded on glass coverslips and cultured until reaching approximately 80% confluence. After fixation in a 3.7% v/v formalde-hyde-PBS solution for 20 min and permeabilization in a 0.5% v/v Triton-X100-PBS solution for 10 min, cells were processed for OXPHOS labeling as described [24].

Western blot

Protein extracts were prepared from E1.5 and E3.5 chick neural tubes and from HeLa and DF1 cultured cells. Tissue and cell lysis was performed in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 300 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 1 mM PMSF lysis buffer, and 100-μg samples of clarified pro-tein lysates were submitted to SDS-PAGE. Immunodetection of Actin, HSP60, OXPHOS, DRP1, OPA1 and MFN2 proteins was performed as previously described [24].

Results

Antibodies directed against mitochondrial respiratory complexes allow

detecting mitochondria in the chick embryo

In order to visualize mitochondria in the chick neural tube, we used the OXPHOS antibody cocktail directed against one subunit of each of the 5 mitochondrial mammalian respiratory complexes. We first verified the cross-reactivity of this antibody by Western blot using chick-en-derived fibroblasts (DF1 cells) as well as neural tubes dissected from E3.5 embryos. The ex-pected proteins from the 5 complexes were detected in human epithelial HeLa cell extracts, but only those from complexes V, III, and II were clearly visualized in both DF1 cells and neural tubes extracts (Fig 1A). We next compared the signal obtained by immunocytochemistry in HeLa and in DF1 cells (Fig 1B). As expected, the OXPHOS antibody cocktail labeled a filamen-tous mitochondrial network in HeLa cells [30]. In DF1 cells, the OXPHOS signal was clearly similar to the MitoTracker staining, which specifically labeled filamentous mitochondria (Fig 1B). Finally, we electroporated the mitochondria-targeted fluorescent protein-encoding vector Mito-DsRed in E1.5 embryos and performed immunodetection with the OXPHOS antibody cocktail at E3.5.Fig 1Cshows that OXPHOS staining extensively co-localized with the red “mosaic” signal indicative of mitochondria in electroporated cells. Altogether, these results in-dicated that the OXPHOS antibody cocktail was suitable for analyzing mitochondrial morphol-ogy in the chicken neural tube.

Mitochondrial morphology changes during embryonic neurogenesis in

the chicken neural tube

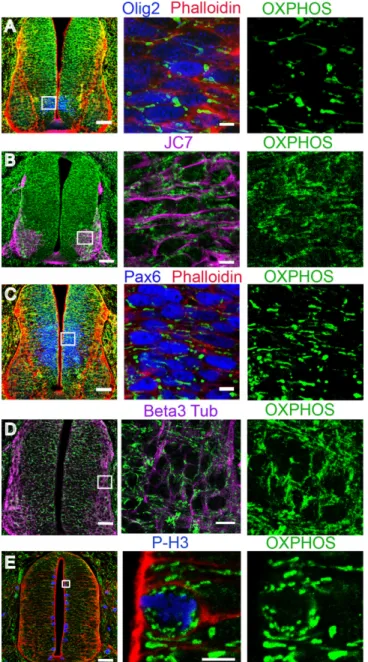

To compare the mitochondrial morphology in neural progenitors versus differentiating neu-rons, we used E3.5 embryos because numerous proliferating neural progenitors are still present in the ventricular zone, while differentiating neurons accumulate in the mantle zone. To pre-cisely analyze the changes occurring in the mitochondrial network related to cell differentia-tion, we focused on progenitors of motor neurons (pMNs) and their corresponding

differentiating motor neurons (MNs), easily traceable with specific markers and confined to the ventral part of the spinal cord. The pMNs were identified using an antibody directed

against the transcription factor Olig2. Differentiating MNs were labeled using the BEN/SC1/ DM-GRASP antibody (named JC7), which recognizes a glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin superfamily on motor neurons and on sensory neurons located outside the spinal cord. We also used phalloidin to detect F-actin and to visualize the morphology of the cell.

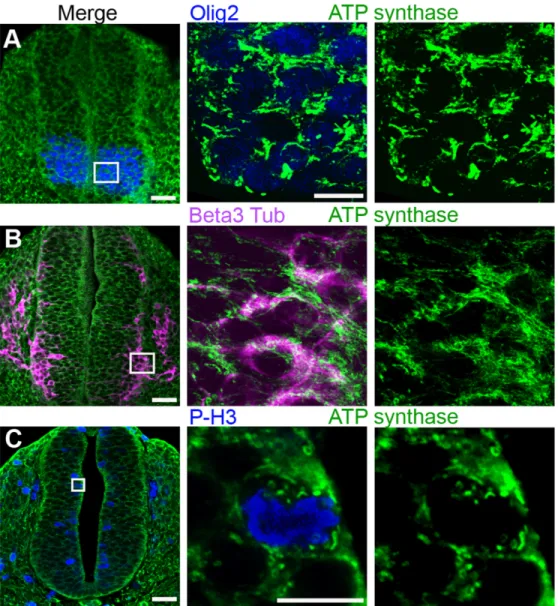

OXPHOS immunodetection in pMNs and differentiating MNs revealed a clear difference in mitochondrial morphology. In pMNs, mitochondria appeared as short and thick well-delineat-ed elements (Fig 2A), distinctly detected around the nucleus. In differentiating MNs, mito-chondria were unambiguously thinner, elongated, and organized into a more complex and denser network (Fig 2B). The same observations were made in the population of spinal progen-itors expressing the transcription factor Pax6 fated to differentiate into interneurons (Fig 2C) and in differentiating neurons visualized using the pan-neuronal marker beta3-tubulin (Fig 2D). We confirmed these observations with an antibody directed against another mitochondri-al protein, TOM20, located in the outer mitochondrimitochondri-al membrane, which gives a signmitochondri-al fully su-perimposable with OXPHOS staining (Fig3A–3C). Altogether, these data indicate that mitochondrial morphology changes at the transition from neural progenitors to differentiating neurons and that this shape modification is a generic event associated with neurogenesis rather than specific to a subtype of neurons.

Fig 1. The OXPHOS antibody labels respiratory complex proteins in Western blots and immunocytochemical experiments. (A) Representative immunoblot of OXPHOS antibody labeling, showing the expected 5 proteins in HeLa cells extracts, and proteins from the V, III, and II complexes in chicken DF1 fibroblasts. (B) Fluorescent micrographs of OXPHOS labeling showing green filamentous mitochondria in HeLa cells (upper left panel) and chick DF1 fibroblasts (lower left panel). MitoTracker staining of DF1 cells depicts a red mitochondrial network (lower right panel) superimposed on the green OXPHOS staining (upper right panel) (scale bar 10μm). (C) Confocal micrograph of a transversal section from a E3.5 chicken neural tube showing

OXPHOS-immunostained mitochondria (green) and a mosaic staining of Mito-DsRed-labeled mitochondria on the left side (red) (scale bar 50μm). Higher magnification at the level of the ventricular zone illustrates the co-localization of the Mito-DsRed (red) and OXPHOS staining (green) (scale bar, 20μm).

In the proliferating progenitor population, cells are either in interphase or in mitosis, divid-ing into two daughter cells. We did not detect any difference in interphasic cells suggestive of mitochondrial rearrangements within G1, G2 and S phases. However, in mitotic cells, located apically and identified using P-H3 or MPM2, the morphology of mitochondria was strikingly

Fig 2. Mitochondrial reshaping accompanies neuronal differentiation in the chicken neural tube. Panels A through E represent confocal micrographs of green OXPHOS-stained mitochondria in E3.5 transversal sections (scale bar 50μm), magnified in the mid- and right-side panels (scale bar 10 μm). In panels A, C, and E, SR101-Phalloidin signaling (red) was used to mark the cellular contours. Neuronal progenitors, immunolabeled either with Olig2 for future motor neurons (A, blue) or Pax6 for future interneurons (C, blue), contain short and thick mitochondria. In panel B, JC7-immunodetection (purple) delineates the surface of differentiating motor neurons endowed with a longer and denser mitochondrial network. In panel D, the mitochondrial network of beta3-tubulin-stained differentiating neurons (purple) is also long and dense. In panel E, P-H3-immunostained (blue) mitotic progenitors are shown to contain very small and round mitochondria.

different than in interphase progenitors as shown using either OXPHOS (Fig 2E) or TOM20 staining (Fig 3D). They appeared as very small and round dots distributed around the con-densed chromosomes. This indicates a drastic reshaping of the mitochondrial network occur-ring in mitosis.

Mitochondrial morphology changes during neurogenesis in the mouse

neural tube

To broaden our findings, we verified if the different mitochondrial morphological characteris-tics observed in the chicken neural tube were also observed in the developing mouse embryo.

Fig 3. Immunodetection of the outer mitochondrial membranes TOM20 reveals the same changes in mitochondrial morphology than OXPHOS. Panels A to C represent confocal micrographs of TOM20 (red) and OXPHOS (green) mitochondria staining in cross-sections of the spinal cord of E3.5 chick embryo. Panel A is a low magnification indicative of the enlargement positions shown in B (left) and C (right). In panel B neural progenitors display short and thick labeled-mitochondria (black and white). In panel C differentiating neurons show a longer and denser mitochondrial network (red or green). Note the evident overlay of the two red and green stainings (left panels). Scale bars, 20μm. Panel D illustrates the TOM20-labeled very small and round mitochondria (red) observed in mitotic cells (white arrows) stained with MPM2 antibody (green). Scale bars, 20μm.

We thus used an antibody specific for the 5thmitochondrial respiratory complex, ATP-synthase, which specifically labels mitochondria (S1 Fig) and appeared more suitable than the whole OXPHOS cocktail for this tissue in terms of signal/noise ratio. We analyzed mouse em-bryos at the E10 development stage, which corresponds to the E3.5 stage in chicken emem-bryos. As in the chick neural tube, short and thick mitochondria were observed in the mouse neuroe-pithelium along the whole ventro-dorsal axis of the neural tube, including Olig2-labeled subdo-mains (Fig 4A). Conversely, in the mantle zone, the beta3-tubulin-labelled differentiating cells contained elongated and branched mitochondria (Fig 4B), in the population of spinal MNs as well as in inter-neurons (data not shown). Very small and round mitochondria were again ob-served in the P-H3-labelled mitotic progenitors (Fig 4C). These observations indicate that this

Fig 4. Mitochondrial reshaping accompanies neural progenitor differentiation in the mouse neural tube. Panels A to C represent confocal micrographs of green ATP synthase-stained mitochondria in E9.5–10 neural tube transverse sections (scale bar 50μm), magnified in the mid- and right-side panels (scale bar 10μm). In panel A, Olig2-stained neuronal progenitors (blue), future motor neurons, contain short and thick mitochondria. In panel B, beta3-tubulin-stained (purple) differentiating neurons are endowed with a longer and denser mitochondrial network. In panel C, P-H3-stained (blue) mitotic progenitors are shown to contain very small and round mitochondria.

change of shape accompanying spinal neurogenesis is conserved between chick and mice spe-cies, suggesting that it is a common property of vertebrate neural cells.

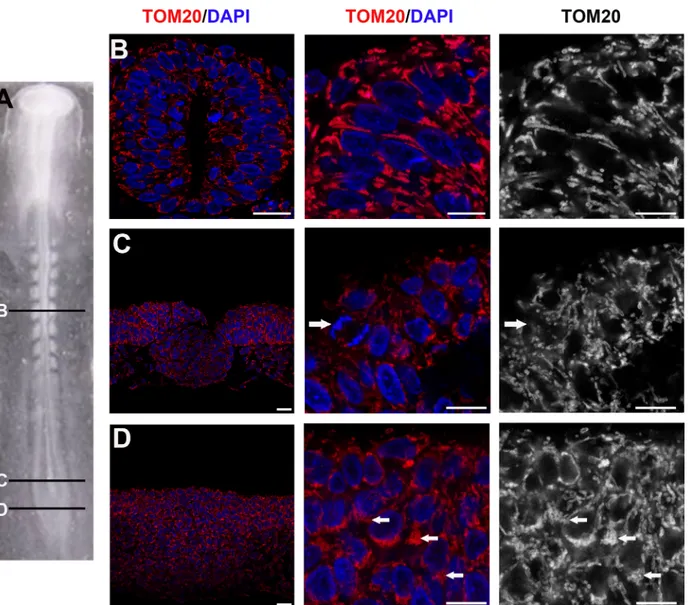

A progressive rearrangement of the mitochondrial network accompanies

neural progenitors maturation

Our observations underlined a morphological change in mitochondria morphology accompa-nying the transition from neural progenitors to differentiating neurons. To complete our data, we then asked if mitochondrial morphology was conserved during the main temporal steps of neural progenitors maturation. We thus stained E1.5 embryos with TOM20 antibodies and an-alyzed mitochondrial shape at different rostro-caudal levels: in the caudal stem zone containing uncommitted progenitors (Fig5Aand5D); in the caudal neural plate where cells are commit-ted to the neural fate (Fig5Aand5C) and in the more mature young neural tube (Fig5Aand

5B). As observed at E3.5, proliferating progenitors from all these rostro-caudal levels at E1.5 also display numerous short and thick mitochondria (5A–5D). The main difference noticed is a re-arrangement of these thick mitochondria within the cells as progenitors become more ma-ture. Indeed, in the caudal stem zone, mitochondria appeared tightly packed (Fig 5D), while displaying a more organized and delineated network in the neural tube (Fig 5B); an intermedi-ate situation was observed at the level of the caudal neural plintermedi-ate (Fig 5C). Together with the ex-periments made at E3.5, these observations indicate that thick and short mitochondrial morphology is a general feature of neural progenitors, and that mitochondria rearrange con-comitantly with the maturation of progenitors in the developing neural tube.

Changes in mitochondrial morphology are not related to major changes

in fission and fusion protein levels

Changes in mitochondrial morphology could be due to a differential expression of the proteins that mediate fission and fusion. We therefore compared the quantities of the fusogenic MFN2 and OPA1 proteins and of the fission protein DRP1 in E1.5 chick neural tubes, containing mostly cycling neural progenitors, with those in E3.5 neural tubes, which contained numerous neurons, using Western blotting (Fig 6). At both stages, MFN2 and DRP1 proteins appeared as single bands, while OPA1 staining displayed the classical isoforms (Fig 6) [30]. The only differ-ence we observed is an approximately 1.5-fold increase in the expression of the longest isoform of OPA1 (159 ± 31%); however, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.063). At both stages, labeling with two specific mitochondrial antibodies gave the same pattern (Fig 6). No difference of OXPHOS and HSP60 levels was detected, suggesting that mitochondrial biomass and respiratory complexes quantities increased to the same extent than the total pro-tein amount and actin between E1.5 and E3.5.

Discussion

Here, we investigated the morphology and distribution of mitochondria in the neural tube of E1,5, E3.5 chicken and E10 mouse embryos upon neurogenesis. We report the first in vivo evi-dence that mitochondria undergo morphological reshaping correlating with the transition from proliferating neural progenitors to differentiating neurons. In the proliferating ventricular zone, mitochondria in the mitotic cells lying at the apical side were very small and round, while they appeared short and thick in interphase cells. In contrast, in differentiating neurons, mito-chondria formed a thin and dense network. This reorganization of the mitomito-chondrial network is not specific of a subtype of progenitors or neurons, suggesting that this is a general event ac-companying neurogenesis in the spinal cord.

In agreement with previously reported in vitro studies, we observed that mitochondrial morphology in neural progenitors varied between interphase (G1/S/G2 phases) and mitosis. Mitochondrial fission has indeed been reported to be increased during mitosis through the ac-tivating phosphorylation of DRP1 by the mitotic kinase CDK1/cyclin B [31], while the recovery of longer mitochondria when exiting mitosis was regulated by the anaphase-promoting com-plex-dependent DRP1 ubiquitination and degradation [32].

Neural progenitors contain short and thick mitochondria, which progressively display a more delineated morphology with neuroepithelium maturation. The low complexity of the mi-tochondrial network in the neuroepithelium is reminiscent of what was described for many pluripotent cell types in vitro [33]. These cells contain rare, short and small perinuclear mito-chondria and are characterized by a glycolytic metabolism that limits ROS production and

Fig 5. Rearrangement of mitochondria in maturating neural progenitors. (A) Dorsal view of E1.5 (stage-10HH) chick embryo; (B-D) cross-sections of panel A. Images in the center and right-hand lanes are enlargements from images in the left lane. (B) TOM20 (red or white) and DAPI (blue) show the well delineated and organized mitochondrial network around the nuclei in the neural tube (Scale bars, 20μm left and mid panels; 10μm right panel). Panels C and D are confocal micrographs of TOM20-stained mitochondria (red and white) and DNA (DAPI, blue) in younger progenitors located respectively in the caudal neural plate (C) and in the caudal stem zone (D). Arrows in B and C point to a mitosis and arrows in D point highly packed mitochondria (Scale bars, 20μm left panel; 10μm, mid and right panels).

oxidative damage [3,4]. Accordingly, reactivation of glycolysis, which is an obligatory step for adult cells reprograming into iPSCs, occurs with mitochondrial shortening and degradation [3]. Thus, the low complexity of the mitochondrial network that we observed in vivo in the neuroepithelium could be related to a glycolytic state.

Upon neurogenesis, progenitors exit the cell cycle, delaminate basally and then migrate into the mantle zone, where they start to develop neuritic processes. We showed that this transition from proliferating progenitors to differentiated neurons is accompanied by an increase in mito-chondrial length and network density. This morphological transition could be related to an in-creased expression of the long OPA1 fusogenic isoform [34] in differentiating cells of E3.5 chicken neural tubes, as well as to post-translational modifications known to regulate the func-tion of mitochondrial dynamics actors but undetectable in our experiment [35] So, as previous-ly demonstrated in vitro, neuronal differentiation in vivo seems to occur with mitochondrial biogenesis and fusion, altogether evocative of a metabolic shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation [4,5,11,36]. As previously described [37,38] this mitochondrial filamentation could allow mitochondria to reprogram into more efficient ATP providers able to fulfill the high energy demands of differentiating cells. Newborn neurons could thus be energized to en-gage in axonogenesis and competition for neurotrophic factors during neuronal growth [39,40].

To conclude, our data shed new light on the various changes occurring in the mitochondrial network along with spinal neurogenesis. These findings suggest that mitochondrial dynamics could play a role in the neurogenic process. Interestingly, a possible causal link between this process and molecular pathways controlling embryonic stem cell differentiation was recently reported. Experimental ablation of OPA1/MFN2 fusogenic proteins was indeed shown to im-pair differentiation of ESC into cardiomyocytes via calcineurin and Notch signaling [11]. Fur-thermore, Notch signaling was recently shown to control both glycolysis and mitochondrial

Fig 6. Differential expression of effectors of mitochondrial dynamics in E1.5 and E3.5 chicken neural tube extracts. Representative immunoblot showing the expression of the mitochondrial dynamics proteins, DRP1, MFN2 and OPA1, as well as mitochondrial respiratory complexes V, III and II and HSP60 protein in E1.5 and E3.5 chicken neural tubes extracts, with actin used as control. While DRP1 and MFN2 are represented as single bands of similar intensities at both ages, staining of the OPA1 isoforms reveals an increase in the longest isoform in the E3.5 extract compared with the E1.5 extract. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128130.g006

activity [41,42]. Thus, during neural tube development, mitochondrial dynamics could contrib-ute to, and act with, the Notch pathway [43], well-known to control the balance between pro-genitor maintenance and differentiation in the developing nervous system [44]. Beyond the nucleus-driven decisions, mitochondrial differentiation could thus pave the way for growth/ differentiation factor-dependent processes.

Supporting Information

S1 Fig. ATP synthase immunodetection in mouse neurons extracts and in fixed neurons. (TIFF)

Acknowledgments

This work was achieved thanks to the Toulouse TRI IBISA imaging platform and the CBD ani-mal core facilities. We thank Brice Ronsin and Philippe Cochard for invaluable help with con-focal imaging and Jérôme Bohère for his participation to exploratory electroporation

experiments. We thank Vincent Setola for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MCM FP PB. Performed the experiments: VM SB JR. Analyzed the data: VM PB FP MCM. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: SBV. Wrote the paper: VM MCM. Supervised experiments: SVB FP MCM. Gave critical feedback on the manuscript: PB SVB FP.

References

1. Nunnari J, Suomalainen A (2012) Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell 148: 1145–1159. Avail-able:http://www.cell.com/article/S0092867412002358/fulltext. Accessed 9 July 2014. doi:10.1016/j. cell.2012.02.035PMID:22424226

2. Chen C-T, Hsu S-H, Wei Y-H (2010) Upregulation of mitochondrial function and antioxidant defense in the differentiation of stem cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800: 257–263. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pubmed/19747960. Accessed 15 August 2014. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.09.001PMID:

19747960

3. Folmes CDL, Nelson TJ, Dzeja PP, Terzic A (2012) Energy metabolism plasticity enables stemness programs. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1254: 82–89. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender. fcgi?artid=3495059&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 12 August 2014. doi:10.1111/ j.1749-6632.2012.06487.xPMID:22548573

4. Facucho-Oliveira JM, John JC St (2009) The relationship between pluripotency and mitochondrial DNA proliferation during early embryo development and embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cell Rev 5: 140–158. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19521804. Accessed 22 July 2014. doi:

10.1007/s12015-009-9058-0PMID:19521804

5. Wagatsuma A, Sakuma K (2013) Mitochondria as a potential regulator of myogenesis. ScientificWorld-Journal 2013: 593267. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid= 3574753&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. doi:10.1155/2013/593267PMID:23431256

6. Van Blerkom J (2011) Mitochondrial function in the human oocyte and embryo and their role in develop-mental competence. Mitochondrion 11: 797–813. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 20933103. Accessed 12 September 2014. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2010.09.012PMID:20933103

7. Prigione A, Fauler B, Lurz R, Lehrach H, Adjaye J (2010) The senescence-related mitochondrial/oxida-tive stress pathway is repressed in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 28: 721–733. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20201066. Accessed 5 September 2014. doi:10.1002/ stem.404PMID:20201066

8. Armstrong L, Tilgner K, Saretzki G, Atkinson SP, Stojkovic M, Moreno R, et al. (2010) Human induced pluripotent stem cell lines show stress defense mechanisms and mitochondrial regulation similar to those of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 28: 661–673. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmed/20073085. Accessed 11 September 2014. doi:10.1002/stem.307PMID:20073085

9. Wilkerson DC, Sankar U (2011) Mitochondria: a sulfhydryl oxidase and fission GTPase connect mito-chondrial dynamics with pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 43: 1252–1256. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21605695. Accessed 12 September 2014. doi:10. 1016/j.biocel.2011.05.005PMID:21605695

10. Galloway C a, Lee H, Yoon Y (2012) Mitochondrial morphology-emerging role in bioenergetics. Free Radic Biol Med 53: 2218–2228. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid= 3594133&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 31 July 2014. doi:10.1016/j.

freeradbiomed.2012.09.035PMID:23032099

11. Kasahara A, Cipolat S, Chen Y, Dorn GW, Scorrano L (2013) Mitochondrial fusion directs cardiomyo-cyte differentiation via calcineurin and Notch signaling. Science 342: 734–737. Available:http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24091702. Accessed 5 September 2014. doi:10.1126/science.1241359

PMID:24091702

12. Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC (2003) Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coor-dinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol 160: 189–200. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2172648&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 10 July 2014. PMID:12527753

13. Alavi M V, Bette S, Schimpf S, Schuettauf F, Schraermeyer U, Wehrl HF, et al. (2007) A splice site mu-tation in the murine Opa1 gene features pathology of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Brain 130: 1029–1042. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17314202. Accessed 5 September 2014. PMID:17314202

14. Davies VJ, Hollins AJ, Piechota MJ, Yip W, Davies JR, White KE, et al. (2007) Opa1 deficiency in a mouse model of autosomal dominant optic atrophy impairs mitochondrial morphology, optic nerve structure and visual function. Hum Mol Genet 16: 1307–1318. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/17428816. Accessed 5 September 2014. PMID:17428816

15. Ishihara N, Nomura M, Jofuku A, Kato H, Suzuki SO, Masuda K, et al. (2009) Mitochondrial fission fac-tor Drp1 is essential for embryonic development and synapse formation in mice. Nat Cell Biol 11: 958– 966. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19578372. Accessed 16 August 2014. doi:10. 1038/ncb1907PMID:19578372

16. Wakabayashi J, Zhang Z, Wakabayashi N, Tamura Y, Fukaya M, Kensler TW, et al. (2009) The dyna-min-related GTPase Drp1 is required for embryonic and brain development in mice. J Cell Biol 186: 805–816. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2753156&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 1 September 2014. doi:10.1083/jcb.200903065PMID:

19752021

17. Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin JM, Gigarel N, Lorenzo C, Belenguer P, et al. (2000) Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nat Genet 26: 207–210. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11017079. PMID:11017079

18. Züchner S, Mersiyanova I V, Muglia M, Bissar-Tadmouri N, Rochelle J, Dadall EL, et al. (2004) Muta-tions in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat Genet 36: 449–451. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15064763. Accessed 12 Septem-ber 2014. PMID:15064763

19. Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC (2007) Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell 130: 548–562. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17693261. Ac-cessed 5 September 2014. PMID:17693261

20. Kageyama Y, Zhang Z, Roda R, Fukaya M, Wakabayashi J, Wakabayashi N, et al. (2012) Mitochondri-al division ensures the survivMitochondri-al of postmitotic neurons by suppressing oxidative damage. J Cell Biol 197: 535–551. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3352955&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 12 September 2014. doi:10.1083/jcb.201110034PMID:

22564413

21. Lee S, Sterky FH, Mourier A, Terzioglu M, Cullheim S, Olson L, et al. (2012) Mitofusin 2 is necessary for striatal axonal projections of midbrain dopamine neurons. Hum Mol Genet 21: 4827–4835. Available:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22914740. Accessed 5 September 2014. doi:10.1093/hmg/ dds352PMID:22914740

22. Li H, Chen Y, Jones AF, Sanger RH, Collis LP, Flannery R, et al. (2008) Bcl-xL induces Drp1-depen-dent synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 2169–2174. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2542873&tool =

pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 17 September 2014. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711647105

PMID:18250306

23. Wang X, Su B, Lee H, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, et al. (2009) Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 29: 9090–9103. Available:http://www.jneurosci.org/ content/29/28/9090.abstract. Accessed 4 September 2014. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009

24. Bertholet AM, Millet AME, Guillermin O, Daloyau M, Davezac N, Miquel MC, et al. (2013) OPA1 loss of function affects in vitro neuronal maturation. Brain 136: 1518–1533. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmed/23543485. Accessed 11 September 2014. doi:10.1093/brain/awt060PMID:23543485

25. Li Z, Okamoto K-I, Hayashi Y, Sheng M (2004) The importance of dendritic mitochondria in the morpho-genesis and plasticity of spines and synapses. Cell 119: 873–887. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmed/15607982. PMID:15607982

26. Kosodo Y (2012) Interkinetic nuclear migration: beyond a hallmark of neurogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci 69: 2727–2738. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22415322. Accessed 4 September 2014. doi:10.1007/s00018-012-0952-2PMID:22415322

27. Cohen M, Briscoe J, Blassberg R (2013) Morphogen interpretation: the transcriptional logic of neural tube patterning. Curr Opin Genet Dev 23: 423–428. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 23725799. Accessed 23 August 2014. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2013.04.003PMID:23725799

28. Le Dréau G, Martí E (2013) The multiple activities of BMPs during spinal cord development. Cell Mol Life Sci 70: 4293–4305. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23673983. Accessed 26 Au-gust 2014. doi:10.1007/s00018-013-1354-9PMID:23673983

29. Lobjois V, Benazeraf B, Bertrand N, Medevielle F, Pituello F (2004) Specific regulation of cyclins D1 and D2 by FGF and Shh signaling coordinates cell cycle progression, patterning, and differentiation during early steps of spinal cord development. Dev Biol 273: 195–209. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pubmed/15328007. Accessed 9 September 2014. PMID:15328007

30. Olichon A, Emorine LJ, Descoins E, Pelloquin L, Brichese L, Gas N, et al. (2002) The human dynamin-related protein OPA1 is anchored to the mitochondrial inner membrane facing the inter-membrane space. FEBS Lett 523: 171–176. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12123827. PMID:

12123827

31. Taguchi N, Ishihara N, Jofuku A, Oka T, Mihara K (2007) Mitotic phosphorylation of dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 participates in mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem 282: 11521–11529. Available:http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17301055. Accessed 22 July 2014. PMID:17301055

32. Horn SR, Thomenius MJ, Johnson ES, Freel CD, Wu JQ, Coloff JL, et al. (2011) Regulation of mito-chondrial morphology by APC/CCdh1-mediated control of Drp1 stability. Mol Biol Cell 22: 1207–1216. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3078078&tool =

pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 20 August 2014. doi:10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0567PMID:

21325626

33. Lonergan T, Bavister B, Brenner C (2007) Mitochondria in stem cells. Mitochondrion 7: 289–296. Avail-able:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3089799&tool =

pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 26 August 2014. PMID:17588828

34. Ishihara N, Fujita Y, Oka T, Mihara K (2006) Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolyt-ic cleavage of OPA1. EMBO J 25: 2966–2977. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/ articlerender.fcgi?artid=1500981&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 29 September 2014. PMID:16778770

35. Chan DC (2011) Fusion and Fission: Interlinked Processes Critical for Mitochondrial Health. Annu Rev Genet 46: 120830114430006. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132529

36. Chen C-T, Hsu S-H, Wei Y-H (2012) Mitochondrial bioenergetic function and metabolic plasticity in stem cell differentiation and cellular reprogramming. Biochim Biophys Acta 1820: 571–576. Available:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21983491. Accessed 8 August 2014. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen. 2011.09.013PMID:21983491

37. Gomes LC, Di Benedetto G, Scorrano L (2011) During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat Cell Biol 13: 589–598. doi:10.1038/ncb2220PMID:

21478857

38. Tondera D, Grandemange S, Jourdain A, Karbowski M, Mattenberger Y, Herzig S, et al. (2009) SLP-2 is required for stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfusion. EMBO J 28: 1589–1600. doi:10.1038/emboj. 2009.89PMID:19360003

39. Erecinska M, Cherian S, Silver IA (2004) Energy metabolism in mammalian brain during development. Prog Neurobiol 73: 397–445. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15313334. Accessed 11 September 2014. PMID:15313334

40. Choi SY, Kim JY, Kim H-W, Cho B, Cho HM, Oppenheim RW, et al. (2013) Drp1-mediated mitochondri-al dynamics and survivmitochondri-al of developing chick motoneurons during the period of normmitochondri-al programmed cell death. FASEB J 27: 51–62. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid= 3528306&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 12 September 2014. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-211920PMID:22997225

41. Landor SK, Mutvei AP, Mamaeva V, Jin S, Busk M, Borra R, et al. (2011) Hypo- and hyperactivated Notch signaling induce a glycolytic switch through distinct mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:

18814–18819. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3219154&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 11 September 2014. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104943108

PMID:22065781

42. Basak NP, Roy A, Banerjee S (2014) Alteration of mitochondrial proteome due to activation of Notch1 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 289: 7320–7334. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 24474689. Accessed 25 August 2014. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.519405PMID:24474689

43. Kasahara A, Scorrano L (2014) Mitochondria: from cell death executioners to regulators of cell differen-tiation. Trends Cell Biol. Available:http://www.cell.com/article/S0962892414001421/fulltext. Accessed 3 September 2014.

44. Shimojo H, Ohtsuka T, Kageyama R (2011) Dynamic expression of notch signaling genes in neural stem/progenitor cells. Front Neurosci 5: 78. Available:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/

articlerender.fcgi?artid=3116140&tool = pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. Accessed 12 August 2014. doi:10.3389/fnins.2011.00078PMID:21716644