MIT LIBRARIES

3

9080

01 tf§. ..." :..-. : . :iimlkimlmmwMM

Bi;.'

• -'. -: <:l; ffiM/lMS/'W!') ft'/iMi/'W/liff!

HB31

.M415

X)0

.00-

IDEWEY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

CREDIT

MARKET

IMPERFECTIONS

AND

PERSISTENT

UNEMPLOYMENT*

Daron Acemoglu,

MIT

Working

Paper

00-20

SEPTEMBER

2000

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper can

be downloaded

without charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection at

MASS/ INSTITUTE

OFTECHNOLOGY

OCT

3

2000

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

CREDIT

MARKET

IMPERFECTIONS

AND

PERSISTENT

UNEMPLOYMENT*

Daron Acemoglu,

MIT

Working Paper

00-20

SEPTEMBER

2000

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection at

http:

//papers,

ssrn.

com/paper.

taf?abstract_id=242228

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

Credit

Market

Imperfections

and

Persistent

Unemployment

*Daron Acemoglu

Department

ofEconomics

Massachusetts

Institute ofTechnology

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

September

11,2000

Abstract: This

paper

develops the thesis that creditmarket

frictionsmay

be an

important contributor to highunemployment

inEurope.

When

achange

in the technological regime ne-cessitates the creation ofnew

firms, thiscan

happen

relatively rapidly in the U.S.where

creditmarkets

function efficiently. In contrast, inEurope,

job creation is constrainedby

creditmarket

imperfections, so

unemployment

risesand remains

high foran extended

period.The

datashow

that there has not

been

slowergrowth

in the'most

creditdependent

industries inEurope

relativeto the U.S., but the share of

employment

in these industries is lowerthan

in the U.S.. Thissuggests that although credit

market

imperfections are unlikely tohave

been

themajor

cause ofthe increase in

European

unemployment,

theymay

have

playedsome

role in limitingEuropean

employment

growth.'Paper prepared for the European Economic Association 2000, Bolzano, Italy- I thank Pol Antras for

excel-lent research assistance, and Abhijit Banerjee, Olivier Blanchard, Jaurae Ventura and seminarparticipants in the

l

Introduction

The

problems

facingEuropean

labormarkets

arenow

well-known,and

a large literature triesto explain

how

unemployment

couldbe

so high for such a long time in anumber

ofEuropean

economies

(see, for example, Layard, Nickell,and Jackman,

1991;Bean,

1994 or Nickell, 1997 forreviews).

Most

economists believethat the rigidlabormarket

institutions ofEuropean

economies

are, at least in part, responsible for thehighrates of

European

unemployment.

In a recent reviewSiebert put this in a stark form: "Labor

Market

Rigidities:At

theRoot

ofUnemployment

inEurope".

It

would

notbe an

unfair statement, however, to say that theeconomics

profession is still ata lossin understanding the

European

unemployment

phenomenon.

Although

the idea that labormarket

rigidities causeunemployment

is plausible, there havebeen

only a fewmajor

changes inthe institutions of

European

economies

over the 1970's to lead to the high rates ofunemployment

ofthe 1980's

and

1990's (see, for example, Nickell, 1997). For this reason,many

economistshave

emphasized

not onlyinstitutions,but

also othermacroeconomic

changes.The

famous

Krugman

hypothesis, for example, explains the increase inEuropean

unemploy-ment

as a result of the interactionbetween

skill-biased technicalchange

and

labormarket

in-stitutions

(Krugman,

1994,OEC'D,

1994).Adrian

Wood

(1994) similarly argues that increasedinternational tradeput

downward

pressureon

thewages

oflessskilled workers,and

unemployment

resulted because the rigid

European

labormarkets

prevented unskilledwages from

falling.More

recently, Ball (1997)

and Blanchard

and

Wolfers (1999)have

emphasized

the interaction between,macroeconomic

shocks, such as disinflation, theslowdown

inTFP

growth

and

the increase inthe real interest rates,

and

the rigid labormarket

institutions as an explanation forEuropean

unemployment.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to generate large responses to

any

of these shocks. For example,the evidence is

hard

to reconcile with skill-biased technicalchange

being the driving force ofunemployment

inEurope

(e.g., Nickelland

Bell, 1996; Card,Kramartz

and Lemieux,

1998;Kruger

and

Pischke, 1998). Similarly, the effect of increased international tradeseems

relatively small(see, for example,

Krugman,

1995;Lawrence and

Slaughter, 1994).Macroeconomic

shocks,on

the other hand,do

notappear

tobe

largeenough

to lead to such a persistent effect.Although

disinflation during the early 1980's could

have

increasedunemployment,

it is onlyan

extreme

degree of hysteresis that can sustain very high levels of

unemployment

for over twenty years. Similarly, inmost

standard models, apermanent slowdown

inTFP

or apermanent

increase inthe interest rate only

have

a small effecton

theunemployment

rate.This

assessment of the state of literatureon

unemployment

suggests thatwe

neednew

ways

oflooking at the

unemployment

problem.This

papermakes

apreliminaryattempt

at developingan alternative hypothesis.1

I develop the thesis that differences in the credit

markets

may

have

'Previously, Krueger and Pischke (1998) argued that differences in product market competition could be im-portant in understanding European unemployment.

A

recent paper byWasmer

and Weil (2000) provides aplayed an

important

role in the increase inEuropean

unemployment.

To

develop this idea assimply as possible, I will abstract

from

labormarket

rigidities,and

focus onlyon

differences in credit markets. In addition to illustrating theimportance

of creditmarket problems

in causingunemployment

differences, themodel

presented here is a simple starting point for analyzing thejoint behaviorof access to credit

and

labormarket

prices.Credit

markets

differ inmany

dimensionsbetween

the U.S.and Europe.

In the U.S., stockmarket

activity, venture capital finance,and

funding of small businessesappear

more

important

than

in Europe. In contrast, in Europe, lendingby

largebanks appear

to play amore

prominent

role.

Most

measures

in factshow

that creditmarkets

aremore

developed in the U.S.than

in

Europe

(e.g.Rajan

and

Zingales, 1998). I willmake

a heroic abstractionfrom

themany

complexities,

and

presume

that the U.S. creditmarket

ismore

flexible in providing loans tonew

firms.The main

argument

in thepaper

is that this difference in theway

inwhich

creditmarkets respond

tonew

opportunities isan

important

contributor to the differentemployment

performances in these economies.

Even

though, as Ishow

below, coordination failures can lead to a highunemployment

equi-librium in an

economy

with imperfect credit markets, differences in creditmarkets

will often nothave

large effectson

steady stateunemployment

rates, because entrepreneurswho

need

creditwill get it eventually.

However,

in themedium

run, the failure to channelmoney

to the correctentrepreneurs

can have

a large effecton

unemployment.

To

capture these issues, I think ofthe U.S.

and

Europe

during the 1950'sand

1960's as characterizedby

the steady state oftwo

economies, onewith

better creditmarkets than

the other.Unemployment

inboth economies

willbe low to start with. I will then consider the responseofthese

two economies

to acommon

shock: the arrival of anew

set of technologies.The

main

result is that theeconomy

with

better creditmarkets

willrespond

to the arrival ofnew

technologieswithout

an increaseinunemployment.

Incontrast, in the

economy

with worse creditmarkets

(themodel

equivalent ofEurope), thechange

in technologies can

have

a persistent adverse effecton

unemployment

because, in the absence ofefficient credit markets, the agents

who

need

tohave

the cash to startup

new

businesses cannotborrow

the necessary funds.They

have toaccumulate

this cashthrough

theirown

savings (or relyon

more

expensivealternative sources of finance, such asborrowing

from

theirfamily), so theeconomy

goesthrough an extended

period of depressedjob creation.Accumulation

by

potentialentrepreneurs

may

be

made

evenmore

difficultby

the fact that in a depressed labor market,unemployment

willbe

highand wages

low, so earningsformany

individuals willbe

low.So

a setof self-reinforcing factors slow

down

the transition of theeconomy

to lowunemployment

for anextended

period.The

ideathat therehasbeen

achange

intechnology (or thepattern ofcomparative

advantage),and

that the U.S. hasadapted

tothischange

fasterthan

Europe

is plausible.Many

commentators

think that the engines of

growth

of the U.S.economy

today

is notcompanies

likeFord

orGM.

simple model combining labor and credit market imperfections, and shows that credit market imperfectionstend

to increase unemployment. Another recent paper by Blanchard and Giavazzi (2000) emphasizes the interaction

between product markets and labor markets, while Bertrand and Kramartz (2000) investigate the impact ofthe

but

new

firms like Microsoftand

Intel,which

require different skills,and perhaps

different typesof financial arrangements. Nevertheless,

more

empirical evidence is necessary to assess theimportance

ofthese factors in explainingEuropean

unemployment.

As

a preliminaryattempt

Ilook at the evolution of sectoral

employment

acrossOECD

countries. I classifymanufacturing

industries into high,

medium

and

low credit-dependent categories followingRajan

and

Zingales(1998),

and

look atwhether

themost

credit-dependent industries, such as electronicsand

officeand computer

equipment,grew

slower inEurope

since 1970. I find no evidence for amajor

differential

growth

across thesesectors. Thisresult isnot encouragingforthecreditmarket

story.Nevertheless, I find that the fraction of

employment

in themost

credit-dependent industries ishigher in the U.S., suggesting that differences in credit,

markets

may

be

playingsome

role inconstraining

employment

creation in Europe. Furthermore, itmight

be argued thatwhat

ismore

relevant is not

growth

of specific industries, but job creationby

new

firms within all industries.The

dataIhavedo

not enablean

investigation ofwhether

therehasbeen

lessemployment

creationby

new

firms inEurope than

theU.S. over the past 25 years.This

is an interesting research areafor future work.

2

The

Model

Consider an

economy

that consists ofamass

1 ofagentswho

livefor one period,and

are replacedby

an offspring.Each

agent canbecome

an entrepreneur, a worker, orremain unemployed.

Production takes place in worker-entrepreneur pairs.Agents

differ in theirskills. Letan

be thetype ofagent i ofgeneration t.

Then,

if agent ibecomes

an

entrepreneurand

hires worker j withtype «j.(, they

produce

3a

ht+

a

jit. (1)This

form

of the production function implies that skills ofboth

the entrepreneurand

the worker matter for productivity, but that of the entrepreneur ismore

important." Iassume

that thedistribution of

a

in the population is givenby

G

t (a) with lower supporta

mm

and upper

supportftmax

All agents have preferences given

by

(l-sf-s'Clj'BZt-eit,

where

C

is consumption,B

is bequest left to their offspring,and

e is cost of effort. This utilityfunction is convenient as it implies a constant saving rate, s. It also implies that the indirect

utility function is linear, in particular

U

(y)=

y—

e,where

y is income, so that all agents are riskneutral.

Thefact that the productivity ofthe entrepreneur isthreetimes more important than that ofthe worker isto simplify someofthe expressions below.

I also

assume

that the cost ofeffort is given as follows{j

w

if

worker

and

exert effortif

worker

and

exertno

effort7

E

ifentrepreneurwhere j

w

<

*yE

. For future use, I defineA

7

=

7

s~

7w/.

The

effort choice ofan

individual is hisprivate information. In contrast, the skill level of a

worker

iscommon

knowledge.For theanalysis, it is

important

thatthe abilitytoperform

entrepreneurial tasks are correlatedacross generations. I

adopt

a particularly simpleform

ofthis here,and assume

that the type ofagents

do

notchange

across generations, i.e., a^t=

Oij-i for all i.The

fact that workersneed

to exert costly effort that is not observedby

others introducesa

moral

hazard problem.Workers need

tobe induced

to exert effortthrough

monetary

incentives.I

assume

that if the worker does not exert effort,output

willbe

high with probability q,and

with probability 1

—

q. In contrast, if he exerts effort, output willbe

high with probability 1.The wage

contract of aworker

oftypea

has toencourage

him

to exert effort as in the standardefficiency

wage

model. Iassume

that negativewages

are not possible, sow

(a)>

0. Since allagents are risk neutral, a

worker

who

produces no output

will get a zero wage. Therefore, theutility to shirking (not exerting effort) is

qw

(a)whereas

the utility to exerting effort isw

(a)—

e.This implies that to encourage effort, the wage,

w(a),

needs tobe

greaterthan

v

=

(l-q)~

1 -t

'

W

.I

assume

that it is always in the interest ofthe entrepreneurs toencourage

high effort. Hence,there is

an

incentive compatibility constraint (the equivalent of the no-shirking condition in theShapiro

and

Stiglitz, 1984,model) which

requires thatwages

for all possible types of workerssatisfy

w

(a)>

v. (IC)Finally, to

become

an entrepreneur,an

individual needsan

investment of 2A'.The

exact timing ofevents is as follows.At

the beginning ofthe period, each agent decidesto

become

an entrepreneur or a worker. If there is a credit market, entrepreneursborrow

the necessary funds, otherwise theyhave

to use theirown

wealth. Entrepreneurs hire workers,production takes place,

and

theypay back

the loans. Finally,consumption and

bequest decisions aremade.

The

labormarket

is Walrasian except for the presence of themoral hazard

constraint(see, e.g.,

Acemoglu

and

Newman,

1997).Since there is

no

discounting within a period,an

entrepreneurwho

borrows an

amount

IK

at the beginning of the period has to

pay back

2A".So

the utility ofan

entrepreneur oftypea

employing

a worker of type a' as a function ofthe wage,w

(a), iswhere

3a

+

a

1is the revenue that this

employment

relationship generates,IK

is the cost ofcapital,

and j

E

is the effort cost. Since the labormarket

is competitive, in equilibriuman

entrepreneur hasto obtain thesame

level ofprofitsfrom

hiringtwo

different workers. Therefore,Ue{oc,q')

=

Ue

(a,a"), for all a'and a"

that are workers. This implies that the equilibriumwage

contract has to take the simple linearform

w

(a/)=

w*

+

a', (3)where

the constant term,w*

will adjust to clear the market.The

incentive compatibilitycon-straint, (IC),

imposes

awage

floorand

implies that workers withw*

+

a'<

v, i.e., witha'

<

a

=

v—

w*, (4)will

be unemployed.

Intuitively, their contribution to the revenues of the firm falls short of thewage

that theyhave

tobe

paid to solve themoral

hazard problem.Along

the equilibrium path, allemployed

workers exert effort, so the utility tobecoming

a worker for an agent with a'>

v—

w*

isU

W

(a')=

w*

+

a'-

lw

(5)Combining

eqs. (2)and

(5),we

obtain that all individuals with skill level greaterthan

a*

=

w*

+

K

+

Ao

(6)would

liketobecome

entrepreneurs.Whether

they cando

so ornot willdepend on

theavailabilityofcredit.3

3

Equilibrium

Without

Credit

Market

Frictions

The

equilibrium with creditmarket

frictions is relatively easy to characterize since all agentswho

want

tobecome

an entrepreneur can obtain finance. Letme

define thewage

function that isconsistent with full

employment,

w

m

(a)=

wm +

a, in the absenceof creditmarket

frictions. Leta

m

be themedian

of the distribution of a- (i.e.,G

(am

)=

1/2). For fullemployment,

half ofthe agents

need

tobecome

entrepreneurs.Without

creditmarket

frictions, this implies that allagents with

a

greaterthan

a

m

shouldbecome

entrepreneurs. Hence, themedian

agent shouldbe

indifferent

between

entrepreneurshipand working

for the equilibrium wage,w

(am

)=

w

m +

a

m

.

Therefore, the full

employment

equilibriumwage

functionmust

satisfyiu

m

=

a

m

-

K

-

A-),Since

my

focus ison

the interactionbetween

creditmarket

frictionsand unemployment,

Iimpose

that the lower support of the ability distribution,Q

m

in, is lessthan

w

m

:

'It is also possible that workers with ability less than a, who cannot become workers because of the wage

constraint, might want tobecomeentrepreneurs. I assumethat 3a -u>* -

IK

--yE

<

0, which rules thispossibilityAssumption

1:a m

\n<

w

m

,which

implies that fullemployment

will notbe

an equilibrium.Equilibrium is

now

characterizedby

a cutofflevelofabilitya

satisfyingequation (4) tobecome

a worker, a cutoff level of ability a* for entrepreneurship that satisfies equation (6), the

wage

function (3),

and

amarket

clearing condition. Thismarket

clearing condition requires that thenumber

ofentrepreneurs is equal to thenumber

of workers, or1-G(q*)

=

G(a*)-G(a),

(7)where

1—

G

(a*) is thenumber

of agents with ability greaterthan

the cutoff level, a*,who

become

entrepreneurs,and

G

(a*)—

G

(a) is thenumber

ofagentswho

are not skilledenough

tobe

entrepreneurs, but have a sufficient skill level tobe

employed.Equation

(7) is a simple supplyequals

demand

condition.The

left-hand side, is thedemand

for labor,and

since a* is increasingin

w*

,demand

falls as the price of labor increases.The

right-hand side is the supply of labor,which

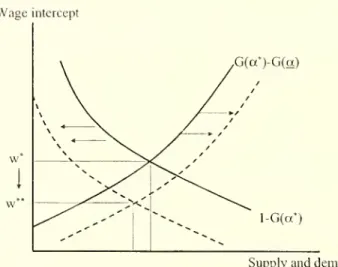

is a strictly increasing function of to*. Figure 1shows

the determination of the unique equilibriumwage

function, i.e.,w*

.Once w*

is determined, theunemployment

level is givenby

G(v-w*).

Wageintercept .G(a*)-G(a) / //

//

//

/f—

*-//

/ \ -X

\ \ V X N *%^

,'' "--^ l-G(a')Supply anddemand

Figure 1:

The

determination of equilibriumwage

level w*,and comparative

statics in responseto

an

increase inA7

orK.

Proposition

1There

exists a unique steady state equilibrium characterizedby [a,a*,w*)

givenby

equations (4), (6),and

(7). In this equilibrium, all agents with skill level greaterthan

o*become

entrepreneurs, all agents with skill level a'€

[a,a*}become

workersand

receive awage

w

(a1)

=

w*

+

a'and

all agents with skill levela

<

a

areunemployed.

The

comparative

statics of this equilibrium are straightforward,and can be

obtained using Figure 1. Increases inK

orA7

make

entrepreneurship less attractive, shiftboth

the supplyand

demand

curvesdown

to thebroken

curves,and

lead to a lower equilibriumwage

intercept w**.As

aresult,both

a*and

a

increase, so there arefewer entrepreneurs,and

more

unemployed

workers.

It is useful to characterize the steadystate wealth distribution,

even though

thewealthdistri-bution does not affect theequilibrium allocation in this

economy

without creditmarket

frictions. First, notice that all agentswho

want

tobecome

an

entrepreneur hire a worker. Therefore,entrepreneur

a

will leave bequest ofBf

+l (a)=

s(Bf

(a)+

3a

—

xv*—

2A") since he received abequestof

Bf

(a)from

his parent, invested 2A", paid awage

ofw*

+

a' for aworker of ability a',and produced

3a

+

a'.He

consumes

a fraction 1—

s of this,and

leaves a fraction s as bequest. In steady state,Bf

(a)=

Bf

+1 (a), soan

entrepreneur oftypea

willhave

wealthv ;

1

-s

The

steady-state wealth distribution for workers, i.e. those with abilitya

€

[a,a*], is givensimilarly. In particular,

Bf

+l (a)=

s(Bf

(a)+

a

+

w*).So

s(a

+

w*)

1-s

Finally, those workers with ability

a

<

a

will beunemployed,

therefore their steady state wealthlevel will

be

B

u=

0.4

Equilibrium

with

Credit

Market

Frictions

Note

that intheeconomy

without creditmarket

frictions, equilibrium prices determine the distri-butionof wealth, but are themselves not influencedby

the distribution ofwealth (i.e., thesystem

is block-recursive). In contrast, in an

economy

with creditmarket

frictions, the equilibriumdepends on

the wealth level of individuals with high skill,who

need

to undertake the up-frontinvestment

IK.

This feedback raises the possibilityofmultiple steady state equilibriaand

richerdynamics.

Here

Iassume

anextreme

form

of creditmarket

frictions: there isno borrowing

(e.g., anindividual could

runaway

with themoney

he

hasborrowed without any

risk ofbeingcaught). Inthis case,

we

need

to determine the equilibrium allocation jointly with the steady-state wealthdistribution. Let

me

denote the steady-state wealth distributionby

F

(b \ a), i.e. this is thefraction ofworkers with ability

a

who

have

wealth level lessthan

b.Then,

themarket

clearing condition in thiseconomy

with creditmarket

frictions is/

p(a)dG(a)=

I (1-

p (a))dG

(a)+

G

(K

+

A

7

+ w

c)

-

G

[v-

w

c

) , (8)

where

w

cis the constant in the equilibrium

wage

functionw

c(a')=

w

c+

a',and p(a)

=

1-F

(2K

| a) is the fraction ofagents with skill levela

who

can afford tobecome

an

entrepreneur,i.e.

have

wealthgreater than 2A". In the expression (8),J

K+

&

+w

cP

(«)dG

(a) is the fraction ofthese agents like

and

can afford tobecome

entrepreneurs.The

remainder

become

workers exceptthose with skill level less

than

v—

w

cwho

cannotbe

employed

profitably.Assumption

2:^±fl

>

IK.

This

assumption

ensuresthatinan

allocation correspondingtothe equilibrium oftheeconomy

with

no

creditmarket

frictions, aworker

with skill level a* canaccumulate

enough

wealth toeventually

become

an entrepreneur.So

in theneighborhood

of the equilibrium of Proposition 1(i.e. without credit

market

problems), those agentswho

need

money

tobecome

entrepreneurscan

accumulate

thismoney

by

saving.This

impliesProposition

2There

exists asteady state equilibrium identical to that described inProposition1.

In contrast to the

economy

without

creditmarket

frictions, the steady-state equilibrium isno

longer unique: there cannow

exist other steady state equilibria. I will givean example

toillustrate this point. Consider the following situation in

which

only a fractionA

ofagentswith

skill level greater

than

K

+

A7 +

w

chave

enough

wealth tobecome

an

entrepreneur.Then,

the equilibrium condition canbe

written as2A

/

dG

(a)+

G

(v-

w

b

)

=

1..lh'+A"/+wb ^ '

where

w

istheconstant inthewage

function.A

lower levelofA

impliesalower equilibrium wage,and moreover

as A—

» 0.w

b—

>v

—

a

max. Hence, as long as theupper

support ofthedistribution ofskills,

a

max, is not very high (i.e.,a

max

<

(1

—

s)2K/s),

we

can

always find a level ofA

such thatthe implied

wage

levelw

satisfies -*—

r—

—

'-

<

2K.

Then

no

additional agentcan

accumulate

enough

wealth tobecome

an

entrepreneur,and

theeconomy

is stuck with only asmall fraction ofentrepreneurs (equal to a fraction

A

J

K

A

+wbdG(a)

ofthe population). Therefore, with creditmarket

frictions, therecan

exist other steady state equilibriawith

higherunemployment

and

lowerwages than

the equilibrium characterized in Proposition 2. Intuitively, anothersteady-state equilibrium exists

because

when

only a few of the potential entrepreneurshave

enough

wealth, there is a limited

demand

for labor,and

this depresses wages.With

depressed wages, itis harder for potential entrepreneurs to

accumulate

enough

wealth to finance their investments,and

in fact, as theabove

example

demonstrates, theymay

neverbe

able todo

so, leading toanother steady state equilibrium with greater

unemployment

and

lower wages."1This

intuition isvery similar to the reasoning for multiplicityofsteady states in theBanerjee

and

Newman

(1993)model

of occupational choice. There, too, different wealth distributionscan be

self-sustainingbecause the equilibrium

wage

ratedepends on

thedistribution of wealth.In terms of Figure 1, this corresponds to the demand for labor being an upward sloping curve becausewhen

wages are low, potential entrepreneurs cannot accumulate the necessary funds to hire workers. As a result, there

5

Change

inTechnology

I

now

discusshow

economies withand

without creditmarket

frictions respond to achange

intechnology. I consider a very simple shift in the distribution ofskills, modifying the pattern of

comparative advantage

in entrepreneurship. In particular,suppose

thatG

(.) takesthe followingspecific form: a fraction 1

—

2<p—

^

of agents have a distributionF

(a) withupper

supporta

4, afraction <f>

have

ability cti,and

another fraction </>have skilllevel 03,and

the fraction k have skill«2- I

assume

thata\

>

(%2>

ct3>

C14,and

1/2>

k>

2c/>.Two

economies, one withand

the other without creditmarket

frictions, are in theminimum-unemployment

steady-state equilibrium (i.e., equivalent to that characterizedby

Propositions 1and

2). In particular, I alsoassume

that a\>

0:2>

a

*>

Q:3>

£*; so the agents with skill levela\

and

0.2 willbecome

entrepreneurs.This

implies thatan

agent with skill level Q'2 has tobe

indifferent

between

entrepreneurshipand working

for a wage.So

the equilibriumwage

function,w

(a)=

w

+

a, isw =

a.2—

K

—

A7.

(9)Using

this, I also obtain thata

=

v—

w,

sounemployment

is equal toU = {1-2<P-k)F{v-Q).

(10)Furthermore, I

assume

thatAssumption

3:B

w

(a3)=

^T

1<

2K

<

B

™

(

n

'i)=

s~^^

1

-This

assumption

ensures that the steady state wealth level ofaworker

with skill level 03 isnot

enough

to afford the up-front investment for entrepreneurship, while that of a worker with skill level a\ is sufficient for entrepreneurship.Now

suppose

that there isan

unanticipatedshift in the distribution ofskills attime t*,and

allagents with a\

and

0:3 are switched: i.e., thosewho

had

skill «inow

have

C13and

viceversa.5The

economy

withoutany

creditmarket

frictions willimmediately

adjust tothischange,and

therewill notbe

any macroeconomic

changes—

the equilibrium is still givenby

Proposition 1. In contrast,in the

economy

with creditmarket

frictionsAssumption

3 implies thatunemployment

increases:at first, agents

who

previouslyhad

productivity 03,and

now

have

productivityoj, cannot affordto

become

entrepreneurs.The

evolution ofunemployment

in theeconomy

with creditmarket

frictions

now

depends on

the transitorydynamics

of the model. Transitorydynamics

are ingeneral quite complicated, since the equilibrium

wage

rate changes as the wealth distribution of'Perhaps this is toosimple, since I

am

assumingthat some I agents become lessproductive. It isconceptuallystraightforward,but thenotationallycumbersometoextendthemodelsothatthe productivityofallagentsincreases

over time, and the changing technology can be modeled assome productivities growing more than others over a

agents evolves. Nevertheless, the specific

assumptions

that Iimposed

simplify the analysis. Inparticular, they ensure that the

wage

rate isindependent

of the wealth distribution,and

alwaysequaltow. This isbecause agents with productivity

«2

continuetobe

themarginalentrepreneurs,and

equation (9) still determines the equilibria wage. This implies thatimmediately

after the technologychange

at t*unemployment

increases toU

v

=

{l-2(j)-

K)F(v-w)

+

(t>> U.After this point, the agents (dynasties)

who now

have

skill level aj startaccumulating

wealth.Their wealth level at time t*

+

rcan be

written as5Assumption

3 implies that limr^oo

Bf.+T [a\)>

2A,

so there will exist a threshold time r* suchthat at t*

+

r*, Bf.+T, (a\) exceeds 2A' the for the first time.At

this point, the agentswith

productivity a\

become

entrepreneurs,and

unemployment

fallsfrom

Uf

toU

givenby

(10).Therefore, while

unemployment

is always constant in theeconomy

with perfect credit markets, itincreases

upon

change

oftechnology in theeconomy

with creditmarket

frictions. It stays highpersistently

between

the date oftechnology change, t*,and

the date t*+

t*.By

changingparameters

withinthis simpleexample

we

canmake

thedecline inunemployment

arbitrarily late (e.g., if

'^'^^

~

2 A"), so thismodel

is capable of generatingan

arbitrarily longperiod of

unemployment,

oran

arbitraryamount

of persistence. It is also useful to note thata potentially

important

factor contributing tounemployed

persistence is missing in this simpleexample. In general, with adepressedlabor

demand,

thewage

ratewill alsofall duringtransition,and

this willmake

it harder for potential entrepreneurs toaccumulate

fundssufficient to financetheir

own

businesses.This

is in fact exactly thesame

force that led to the multiplicity of steadystate equilibria in the previous section.

6

Empirical Evidence:

U.S.

vs.Europe

So

far Ihave

presentedan

abstractmodel

ofunemployment

in the presence of creditmarket

imperfections. Credit

market problems

do

not necessarily lead to higherunemployment, though

they

may

introduce additional equilibria with highunemployment

levels.The

major

result is thateconomies

withand

without creditmarket

frictions respond to changes in technology quitedifferently. In response to a shock that changes

which

agentshave

acomparative advantage

in entrepreneurship,

an

economy

without a well-functioning creditmarket

may

suffer a lengthy period ofunemployment,

as productive agents lack the necessary funds to create jobs. Thissituation is reversed only slowly as these agents gradually

accumulate

enough

wealth to financetheir investments.

It is possible to tell a story of

European

unemployment

based

on

this model.Europe and

the U.S.

had

similarunemployment

levels during the 19G0s because theywere both

in a "steady6

Toobtainthisexpressionnote thatattime£*,theystart with wealth

B

w(as)=

iiSjtSa^am

jthen B^i +1 (oi)=

sB

w(q3)+

s(w+

Qi), etc.state situation".

A

variety of changes during the early 1970sand

early 80s shifted thegrowth

sectors ofthe

economy,

requiring different entrepreneursand

firms toassume

amore

importantrole.

This

happened

relatively quickly the U.S. thanks to amore

fluid credit market, especiallywith institutionslike venturecapitalists channeling fundsto the rapidly

growing

high-techsectors.In contrast, in Europe, lack offunds in the

hands

of the peoplewith

the right skills sloweddown

job creation.

Isthere

any

evidence supportingthisstory? Iend

thepaper

with aquick look atsome

sectoralevidence to

answer

this question.There

aretwo

interpretations ofthe model.The

first viewsthe firms that are constrained in

Europe

tobe

those usingnew

technologies within each sector.The

second maintains that it is firms insome

particularly credit-dependent sectorsthat aremost

constraint.

Although

Ido

nothave

away

of investigating the validity ofthe first version of thestory, I can look for support for the second version using the

OECD

sectoral database.With

this purpose, I followRajan

and

Zingales (1998) in classifyingsectors according to their creditsdependents

in theU.S..Using

theresults in Table 1 ofthese authors, I classifyfood,bev-erages

and

tobacco, textile, appareland

leather,wood

and

furniture,paper

and

paper products,basic metals,

and

metal products aslow

credit-dependent industries; chemical, coal, rubberand

plastic products, metal products,

machinery

and

equipment,and

transportequipment

asmedium

credit-dependent industries,

and

electricalgoods

and

officeand data

processingmachine

industries are high credit-dependent industries.By

focusingon

manufacturing, this classification avoidsother potential differences in the U.S.

and

European

economies

in thegrowth

ofservice sectors,though

if service industries aremore

credit-dependent, itmight

understate theimportance

ofcredit problems.

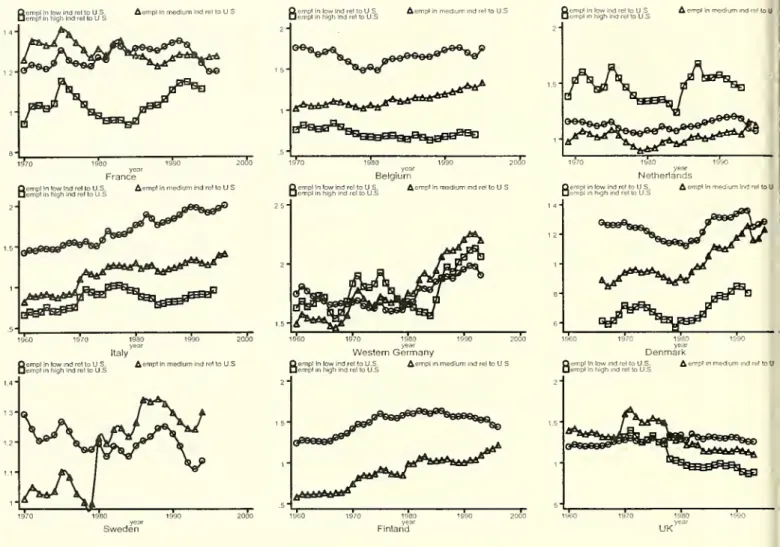

Figure 2 plots theshareof

employment

in anumber

ofEuropean

countriesinthelow,medium,

and

high categories relative to the share of thesame

categories in the U.S..7 IfEuropean

unemployment

ismainly

due

to thefailure oftheEuropean

economies

toexpand

intonew

sectorsbecause ofcredit constraints,

we

would

expect theseeconomies

tofallbehind

the U.S. in thehighcredit sectors. In other words, inthis case, the curve with the squares (the highcategory) should

fall relativeto the other curves, especiallyrelative to thecircles,

which

denote thelowindustries.8For

most

countries, allthree curvesmove

in amore

orless parallel fashion. In fact, forFranceand

Germany,

employment

in high credit-dependent sectorsseem

tobe growing

more

than

anothersectors. Therefore, there is

no

evidence thatEuropean

economies

have

been

fallingbehind

the U.S. in the credit-dependent industries over the period of risingEuropean

unemployment.

1

Thedataare from the

OECD

ISDB dataset, andrefertothetotal numberofemployees in that sector relativeto total employment. More formally, let ec< be total employment in the low group in country c at timet, and

E

ctbe total employment- I

am

plotting (ec,/Ect)/ (evst/En

st) Datafor the high category in Sweden and Finlandaremissing.

An

increase in all three curves, as in the case ofWest Germany or Denmark, would correspond to an increasein the relativeshareofmanufacturingemployment compared tothe U.S..

AemplInmediumindreltoUS

1970

BemplIntowindrel!oU.S.

emplinhighindrelloU.S.

2000

AemplinmediumindretloUS

Italy

Aemp!inmediumindrelloUS

AemplinmediumindreltoUS

BemplinlowindreltoU.S.

emplinhighindreltoU.S.

I --...,

980 1990 7 year

Belgium

AemplinmediumindretloUS

1970

year

WesternGermany

I

emplintowindreltoU.S. AemplinmediumindrelloUS emplinhighindreltoU.S.

1980 year Finland Aemplinmednjmmdt?loU Aem.ptmme 1980 year Denmark

Aemplinmedium<ndre<to 11i

UK

Figure 2:

The

evolution ofthe fraction oftotalemployment

in low,medium,

and

high credit-dependent industries inEuropean

countries relative to the U.S..Data

from

OECD

ISDB

data

set.Nevertheless, except for the

Netherlands

and

theUK,

European

economies appear

tohave

substantially less

employment

in themost

credit-dependent industries. For example, inBel-gium, Italy

and

Denmark,

relativeemployment

in the least credit-dependent industries ison

average

about

50 percentmore

than

in the U.S., while the relativeemployment

in themost

credit-dependent sectors isabout

30 percentlessthan

the U.S..This

suggests that creditmarket

problems

may

have

playedsome

role in constrainingemployment

inEurope.

Interestingly, theUK

iscommonly

thought tohave the best creditmarkets

among

theEuropean

economies, so it issuggestive that the

most

credit-dependent industrieshave

relatively highemployment

in theUK

as well as in the U.S. (though their share in the

UK

employment

seems

tohave

fallen over the1980s).

These

observations givesome

support

for the idea that creditmarket problems

may

havebeen

animportant

factor in the recentEuropean employment

experience,and

encourage furtherresearch in this area.

References

Acemoglu,

Daron

and

Andrew

Newman

(1997)"The Labor Market and

The

Corporate

Struc-ture "

CEPR

working

paper.Ball

Lawrence

(1997) "Disinflationand

theNAIRU"

NBER

WP

#5520.

Banerjee, A.

and

A.Newman

'OccupationalChoice

and

the ProcessofDevelopment.' JournalofPolitical

Economy,

101, 274-298 (1993).Bean

Charles (1994);"European

Unemployment

a Survey" Journal ofEconomic

LiteratureVol 32,

pp

573-619.Bertrand,

Marianne and

FrancisKramartz

(2000), paper presented intheNBER

laborstudies.Blanchard

Olivierand

Justin Wolfers (1999) "Shocks vs Institutions" forthcomingEconomic

Journal.

Blanchard

Olivierand

Francesco Giavazzi (2000)"The

Macroeconomic

Effects of Regulationand

Deregulation InGoods

and

Labor Markets"

MIT

mimeo.

Card

David, FrancisKramartz

and

Thomas

Lemieux

(1995);"Changes

in the RelativeStruc-ture of

Wages

and

Employment:

A

Comparison

oftheUnited States,Canada

and

France"Mimeo.

Krueger,

Alan

B.and

Jorn-Steffen Pischke (1997) "Observationsand

conjectureson

the U.S.employment

miracle,"NBER

Working

Paper

No. 6146,.Krugman,

Paul (1994) "Partand

ProspectiveCauses

ofHigh

Unemployment"

in Federal ReserveBank

ofKansas

CityReducing

Unemployment:

Current Issuesand

Policy Options.Krugman,

Paul,"Growing

World

Trade:Causes

and Consequences"

BrookingsPapers

on.Economic

Activity (1995).pp

327-377.Lawrence,

Robert

and

Matthew

Slaughter "Tradeand

U.S.Wages:

Giant SuckingSound

orSmall

Hiccup?"

BrookingsPapers

on

Economic

Activity, (1993) pp. 161-226.Layard, Richard, Steve Nickell

and Richard

Jackman

(1991)Unemployment:

Macroeconomic

Performance

and

theLabor

Market Oxford

University Press.Legros, Patrick

and

Andrew

F.Newman

(1996);"Wealth

Effects, Distributionand

theTheory

ofOrganization," Journal of

Economic

Theory.Nickell, Steven (1997),

"Unemployment

and

Labor Market

Rigidities:Europe

versusNorth

America," Joum,al ofEconomic

Perspectives. 11, 55-74.Nickell

Stephen

and

Brian Bell (1996)"The

Collapse inDemand

For the Unskilledand

Un-employment

Across theOECD"

OxfordReview

ofEconomic

Policy Vol 11,pp

40-62.OECD

(1994) Jobs StudyVolumes

1and

2.Rajan

Raghuram

and

Luigi Zingales (1998) "FinancialDependence

and

Growth" American

Economic

Review, 88, 559-586.Wasmer,

Etienneand

PhilippeWeil (2000)"The Macroeconomics

Of

Creditand Labor

Market

Imperfections"UBL

Working

Paper.Wood,

Adrian

(1994),North-South

Trade,Employment

and

Inequality:Changing

Fortunes in a SkillDriven

World, Oxford,Clarendon

Press.MIT LIBRARIES