MIT LIBRARIES DUPL

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

MIT

Libraries

DEWEY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Econonnics

Working

Paper

Series

Bidding

for Industrial Plants:

Does

Winning a

"Million

Dollar Plant"

Increase Welfare?

Michael Greenstone

Enrico

Moretti

Working

Paper 04-39

November, 2004

RoomE52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without charge

from

the SocialScience

Research

Network

Paper

CollectionatMASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTEIOF

TECHNOLOGY

Bidding

forIndustrial Plants:Does

Winning

a

'MillionDollar

Plant'Increase

Welfare?

Michael Greenstone

MIT, American

Bar Foundation and

NBER

Enrico

MorettiUniversity

of

California,Berkeley

and

NBER

November

2004

We

thank AlbertoAbadie, Michael Ash, HalCole,David

Card,Gordon

Dahl,Thomas

Davidoff, Michael Davidson,Rajeev Dehejia, Stefano Delia Vigna.Mark Duggan,

Jinyong Hahn, RobertHaveman, Vernon

Henderson, Ali Hortacsu,

Matthew

Kahn,Tom

Kane, Brian Knight, Alan Krueger, SteveLevitt,Boyan

Jovanovic,

David

Lee,ThereseMcGuire,

Derek

Neal,Matthew

Neidell.Aviv

Nevo,

John Quigley,KarlScholz,

Chad

Syverson,Duncan

Thomas

and seminar participants at Berkeley,Brown,

Chicago,Columbia, Illinois, Michigan,

NYU,

NBER

Summer

Institute. Rice. Stanford,UCLA,

Wharton, and Wisconsinforveryhelpful discussions.Adina

Allen,Ben

Bolitzer.JustinGallagher,Genevieve

Pham-Kanter,

Yan

Lee,Sam

Schulhofer-Wohl, AntoineSt-Pierre, and WilliamYoung

provided outstandingresearch assistance. Greenstone

acknowledges

generous funding fromtheAmerican Bar

Foundation.Bidding

forIndustrialPlants:Does Winning

a'MillionDollarPlant*IncreaseWelfare?

Abstract

Increasingly,localgovernments

compete by

offering substantial subsidiesto industrial plants tolocate within their jurisdictions. This paper uses a novel research design to estimate the local

consequences ofsuccessfully bidding for an industrial plant, relativeto biddingand losing, on labor

earnings, public finances, and property values.

Each

issue of Ihe corporate real estatejournal SiteSelection includesanarticle titled

"The

Million DollarPlant" that reports thecountywhere

a large plantchosetolocate(i.e.,the 'winner'), as well asthe

one

ortwo

runner-upcounties(i.e.,the'losers').We

usethese revealed rankings of profit-maximizing firms to form a counterfactual for

what would

havehappened

in thewinningcountiesintheabsenceofthe plant opening.We

find that the plantopeningannouncement

is associated witha1.5%

trend break in laborearnings inthenew

plant's industry in winningcounties, as well as increasedearningsinthesame

industryincountiesthatneighborthewinner.Further, thereis

modest

evidenceof increased expendituresforlocalservices,suchas public education.Property values

may

provide asummary

measure

ofthe netchangeinwelfare,becausethecostsandbenefitsofattracting aplantshould becapitalized into the priceofland. Ifthewinners andlosersare

homogeneous,

asimplemodel

suggeststhatanyrentsshould bebid away.We

findapositive,relativetrend break of approximately 1.1-1.7%in propertyvalues. Sincethe winners andlosers have similar

observables inadvance oftheopening

announcement,

thepropertyvalueresultsmay

be explained by heterogeneityinsubsidiesfrom higherlevelsofgovernment

(e.g.,states)and/or systematic underbidding.Overall, the results

undermine

the popularview

thatthe provision oflocal subsidies to attractlargeindustrialplantsreduceslocalresidents' welfare.

Michael Greenstone

MIT

Department

ofEconomics

50

Memorial

Drive,E52-359

Cambridge.

MA

02142-1347and

NBER

mgreenst@,m

it.eduEnricoMoretti

UniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley

Department

ofEconomics

Berkeley,

CA

94720-3880

and

NBER

• Introduction

Over

the past 30 years, stateandlocalgovernments

haveassumed

a greater responsibility foreconomic

development. For example,they frequently offer substantial subsidies tobusinessesto locatewithin their jurisdictions. Theseincentivescan includetax breaks,low-costor free land, theissuanceof

tax-exempt bonds,trainingfunds, theconstructionofroads, andother infrastructureinvestments.

These

policiesare controversial: local politicians andthe subsidized

companies

usually extol the benefits ofthese deals,whilecriticscomplainthatthey areawasteofpublicmonies.' Itisdifficult toevaluate these

competing

claims,becausethereis littlesystematicevidenceontheconsequences ofthesepolicies.^I'hetraditionalapproachtoevaluating policiesdesignedatattracting

new

plantsistocalculate thenumber

of jobs gained andthe costofthe taxbreaksawarded

to firms. For example, itiswidelycited thatMercedes

received a$250

million ($165,000 per job) incentive package for locating in Vance,Alabama,

theToyota

plant inGeorgetown, Kentucky was awarded $200

million($80,000 perjob)andBoeing

was

given$50million($100,000perjob)intaxabatementstolocates itscorporateheadquartersin

Chicago

(Mitol2001;Trogen

2002). This"accounting"approach produces eye-catchingstatistics,butithas

two

importantlimitations. First,these calculations aredone

ex-anteandare rarely verified ex-post.Second,and

more

fundamentally,thisapproachdoesnot offer aframework

fordetermining whetherthepoliciesincreaseordecrease welfare oflocal residents. Forexample,is

$165,000

perjobagood

dealforthe residentsof Vance,

Alabama?

Economic

theoryprovidesmixed

resultsonthisquestion, asemphasized

by Glaeser (2001) inarecent survey.'

On

theone hand,some models

suggestthatthe attraction ofnew

businesses generatespositive spillovers and/or increases producer surplus. In these cases, local subsidies

may

be welfareenhancingor, at least,neutral forlocalresidents.

On

the otherhand,there aremodels thatindicatethatlocal subsidies

may

reflectgovernment

officials' private interestsby providing for theirown

financialgainor satisfyingLeviathan goals. Inthese settings, local

government

officialsgrant subsidieswhose

coststolocalresidents are largerthanthe benefits

and

thereforereduceresidents" welfare.-Thispaperempirically assesses theconsequences forcounties ofsuccessfullybidding forlarge

industrial plants on county-level earnings, property values, and

government

finances.The

empirical'For example,arecent

front-pagearticleinthe

New

York Timesdescribes theexperienceofseveral localities thatprovidedgeneroussubsidies to attract largemanufacturing firmsinthe 1980sand 1990s and apparently obtained

limited benefits to the localeconomy.("PayingforJobsDoesn'tAlways PayOff,

New

York Times,November

10,2003).

"In arecentsurvey ofthe literature,Glaeser (2001) concludesthat,althoughlocationbased-incentives"seemtobea permanent partofthe urbaneconomic landscape, economists donotyet

know

why

these incentivesoccur andwhethertheyareinfactdesirable". FurtheraStandard

&

Poor's publicationstates,"Economic development warsofrecentyearshave not developeda sufficienttrackrecordtoassesstheirtruecost-benefit ratio"(Standard

&

Poor'schallengeisthat plantschooseto locate

where

theirexpectedprofits are highest,which

area functionoftheir location-specificexpectedfuture costsof production

and

anysubsidies.A

plant'sexpectedfuturecostsof productionina county

depend

onmany

unobservablefactors,includingthepresenceofa suitabletransportation infrastructure, the availability of workers withparticular skills, andthe local regulatory

environment.

These

factors are typicallydifficult tomeasure and

their relativeimportancevariesacrossplants based on plants' unobserved production functions. Similarly, the subsidies are likely to bea

functionofa

number

ofunmeasured

factors, includinganypotential spillovers andthedegreeoflocalpoliticians'malfeasance.

Heterogeneity in the factors thatdeterminevariationincostsof production andsubsidies across

countiesislikelytobiasstandardestimators.Validestimatesoftheimpact ofa plantopeningrequire the

identificationof a countythatisidentical to thecounty

where

the plantdecidedtolocateinboth expectedfuture production costs andthe factors thatdeterminesubsidies.

We

have little faith in ourabilitytoascertainand

measure

allthesefactors.As

a solution,we

rely onthe revealed rankings of profit-maximizing firmsto identify a validcounterfactual for

what would

havehappened

intheabsence ofthe plantopening.These

rankingscome

from thecorporaterealestate journal Site Selection,

which

includes a regular featuretitledthe"Million Dollar Plants" that describeshow

a large plantdecidedwhere

to locate.When

firms areconsideringwhere

toopen

a large plant, they typically beginby

considering dozens ofpossible locations.They

subsequently narrowthelisttoroughly 10sites,

among

which

2 or 3 finalistsare selected.The

"Million DollarPlants"articlesreport thecountythat the plant ultimatelychose(i.e.,the 'winner'), as well as theone or

two

runner-up counties (i.e.. the 'losers').The

losers are counties that have survived a longselection process, butnarrowlylostthecompetition.

Our

identifyingassumptionisthat the losersform

avalid counterfactual for thewinners,afteradjustmentfor differencesinpre-existing trends.

Even

ifthisassumption is invalid,

we

suspect that this pairwise sampling approach is preferable to the leadingalternativeof

comparing

winnerstothe other3,000U.S. counties.Consistent with our assumption,

we

find that beforetheannouncement

ofthe winner county, winning and losing counties have similar trends inwage

bill,employment,

per capitaincome

and employment-population ratio. Several other observablecharacteristics arealso similar.By

contrast,trendsinthewinningcounties tendtobedifferentfromtrendsinallother

US

counties. Notably inthe 8yearsbeforethe

announcement

ofthewinner,the trends inproperty valuesinwinning andlosingcountiesare virtually identical.

Under

the plausibleassumptionthatproperty marketsare forward-looking,thisfinding suggests that not only are winning and losing counties similar in the years before the

'

Seealsotheclassic Gates (1Q72) and Zodrovv and Mieszkowski (1986) papers ontax competitions andthe

annouiiceincnt. but theexpected Futurechanges in

economic

activitytliat arc capitalized intoproperty valuesare alsoex-antesimilar. Overall, these findings lend credibilitytotheidentifyingassumptionthatthe losersforma valid counterfactual for the winners.

The

primai7employment

resultisthat inthenew

plants' I-digitindustry thewage

billincreasedbya statisticallysignificant$16.8 millionper yearinwinningcounties (relativetolosingones)afterthe

opening

announcement

(relativetotheperiod before). Thisis1.5%

oftheaveragewage

billinthe plant's1-digitindustry inwinningcounties intheyear beforetheannouncement.

Taken

literally,thisimpliesthat sixyearslaterthe

wage

bill inthenew

plant's I-digitindustryisroughly$100

millionhigherduetothe plantopening thanpredictedbypre-existing trends.

We

also findevidence ofpositive trendbreaksinthetotal

wage

billinthenew

plant'sindustryincounties thatneighborthe winner.'These

resultsprovidesome

ofthe first ex-post estimates ofthe increase in localeconomic

activity due to the successfulattraction ofa large,

new

plantand indicate that thenew

activitydoesn'tcrowd

out existing activitylocally.

However, by

themselves,these findings are notinformativeaboutwhetherthesubsidiesincreaselocalresidents'welfarebecause theydonotaccountfor theircost. Directinformationonthe costofthe

subsidies is unavailable.

We

follow the stylizedRoback

(1982)model

and arguethatthe netwelfareeffectofattractinga plantwillbereflectedinproperty values. Thisisbecause propertyvalues capitalize

theincreased

economic

activityinthecounty(i.e.the benefitofthesubsidy)andtheincreaseinproperty taxes—or reductioninpublicservices— necessarytopayforthesubsidy(i.e.thecostofthe subsidy).'We

derive a simplemodel

that demonstrates that in the presence of bidding for plants bycounties,asuccessful bid

may

causeproperty values to increase,decreaseorremain unchanged.When

countiesare

homogeneous

andpoliticianssolelymaximize

residents' welfare,the successful attractionofaplantwill leaveproperty values unchanged. This is because countiesraise their bidsuntilthe costs

equalthe benefits

and

theyare indifferentaboutwinningor losing.When

countiesarenothomogenous

orifstatespayforpartofthesubsidy, the successful attractionofa plant

may

resultinincreasedpropertyvalues.This isbecausethecountythathas the mostattractivecharacteristicsor the largest contribution

fromstate

government

canbidlessthanthesecondbestcounty,andstillwin

theplant.Finallywhen

localpoliticians deriveprivate benefits fromgranting subsidies, they will overbid, and property values

may

decrease.

',',,,

.,, • , , .SeeHanson(1998)forevidencethat localshocksaffectneighboringjurisdictionsandthat this effect dissipates

withdistance.SeeChapter 2ofBartik(1991)forareviewofthe effectsofstateandlocaleconomic development programs on employmentandeconomic growth in localareas.

On

a related topic,Evans andTopoleski (2002)examinethe socialandeconomics consequencesoftheopeningofan Indiancasino.

'Gyourko andTracy

(1991)demonstratethatthe efficientprovisionof publicservicesiscapitalized into land.

They

Ultimately, the questionofthe effect ofsuccessfully attracting a planton property values isan

empirical one. Using a unique self-collecteddatafile,

we

find thatthesuccessful attraction ofa plantresultsinincreasedpropertyvalues. Specifically,

we

findthat inwinningcounties thereisa relativetrendbreakofapproximately 1.1-1.7%inannual property valuesaftertheplantopening announcement.Ifour model'sassumptionsare valid,thisfindingcan beinterpretedasanincreaseinwelfarefor localresidents.

Even

iftheassumptionsare notvalid,theproperty valueresults appeartoundermine

the popularviewthattheprovisionoflocalsubsidiesto attractlarge industrialplantsdecreaseswelfare.

The

finalpartof

thepaperestimates the effectofwinningaplantonlocalgovernment

finances.A

widespread concern abouttheprovision ofsubsidies isthat localgovernments pay for

them

bycuttingimportant services, such aseducation and police protection.'' Usingdata

from

theAnnual

Survey ofGovernments,

we

find that localgovernmentsinwinningcountiesexperiencedpositiveand roughlyequaltrendbreaksinrevenuesandexpenditures. Notably,thereisa substantial increaseineducationspending

and

no

changeinpoliceexpenditures. Overall, thereislittleevidenceofdeteriorationintheprovisionofvitalpublic servicesincountiesthat

win

'"MillionDollar"plants.We

want

toemphasize

thatthefocusofthispaperisthe credibleestimation oftheconsequencesfor acountyofsuccessfullybiddingfora

new

plant,relativetobiddingandlosing. Thereareanumber

ofrelated policyand/or welfarequestions,only

some

ofwhich

this papercanaddress. Forexample,theanalysis does not provide evidence on whether states or the nation as a

whole

benefit from taxcompetitions

between

local governments to attractnew

business. Further, it is not informativeabout whether individual counties should pursue industrialdevelopment

policies at all.However,

sincevirtuallyalllargeplantopenings inducetaxcompetitionsbetweenjurisdictions,the salientquestionfora

local

government

interestedinattractingone ofthese plants isnotwhethertobidatailbutwhat

aretheconsequencesofsuccessfully bidding.

The

analysisisstructuredtoinformthisveryquestion.The

paper proceedsas follows. Section1reviewsthe theoreticalexplanationsfortheprovisionoflocalsubsidiesby local

governments

to attractplantsandthedeterminantsofplants' location decisions.Italsoprovides a casestudyof

BMW's

decision tolocate anew

plantinSouth Carolinaandintuitivelydescribes our research design. Section II reviews the

Roback

(1982)model

inthecontext ofa plantopeningandpresentsastylized

model

ofcounties' decisionsto bidforaplantandthe effectof winningonproperty values. SectionIIIdescribes thedatasourcesandpresents

some

summary

statistics. SectionGlaeser (2001)emphasizestheimportanceofansweringthisquestionempirically,"Economistsneedtoestimate

whathappens

when

localitiesare deprivedofthemarginaldollar. Doesthislosslead toeliminatingvery valuableservicesor are fairlymarginalservices cutoff?" (pp.il-12).

Ifoutcomesincountiesthatbidandlosearesimilartocountieswithoutindustrialdevelopmentpolicies,thenthe analysissheds lighton the broader question of the consequencesof whetherindustrial development policies are

IVexplains theeconometriciikhIcI andSection

V

describes theresults. SectionVI interpretsthe resultsand VI1concludes.

I.Local

Subsidy

and

PlantLocation DecisionsThissectionisdivided into

two

parts.The

firstreviewstheexisting theoretical literatureonwhy

local

governments

use incentives to atti'actsome

plants to tiicirjurisdictions.The

second subsection providesa casestudyofBMW's

decision tolocate acarassemblyplant in theGreenville-Spartanburgareaof northwestern South Carolinaand,

more

generally,describes the intuitionof ourresearch design.A.

Why

do

LocalGovernments

Offer SubsidiestoSome

New

Plants?In standard models, the provision ofincentives to firms reduces the welfare ofa locality's

residents.^ Thisisbecausethe incentives lead to inefficientlyhighlevelsoflocalproduction. Yet,inthe

real world, large businesses frequently receive subsidies inexchange for their location decision.

The

implicationisthat thestandardmodels

may

be unabletocaptureanimportant featureof

these locationdecisions. Here,

we

reviewa recentlineofresearch thatprovidesanumber

ofpossibleexplanations forwhy

localities provide incentivestonewly

locating firms. This reviewaimstohighlightsome

ofthe"structural"forces that are likelytounderlieour "reduced-form"estimatesofthewelfareconsequences of

successfully attracting aplant.

The

firstsetoftheoriesemphasizesthe idea that localgovernments aim

tomaximize

only thewelfare oftheir residents.

One

example

isthe casewhere

agglomerationeconomies

areassociatedwiththelocationofthe firm. For example,finnsinthe

same

industrymay

experienceproductivity increasesasthe

number

or sizeof geographically concentrated firms increase(Henderson 2003; Garcia-Milaand

McGuire

2001).These

spilloversmay

beduetothe sharingofinformation, thenumber

of highskilledworkers (Ranch 1993; Glaeseretal. 1995; Moretti

2004a

and 2004b),or that thenew

firms willattractother firmsinthe future. Regardlessoftheirsource,inthepresenceofthese spillovers,localities willbid

to attractthefirms thatproduce

them

andthe resulting subsidiesallowthefirmtocapturethe spilloversthatthey produce.

Glaeser (2001) suggeststhatlocal incentives

may

represent bids bycommunitiesto attract firmsthat will generate producersurplus for the current residents ofthe

community.

Conventional welfareanalysissuggeststhatthere

may

be welfaretriangles tobegainedby localworkers. In particular,ifthe'

SeeWilson(1999)for areview ofthe theoretical literaturesontax incentives.

'

laborsupply curve is

upward

sloping,inframarginal workersaremade

betteroffbythe presence ofthenew

firm.The

sizeofthe bids willreflectthewelfaregains generated.'"Another

explanationfortaxincentivesisthattheseupfrontpayments

arecompensationforfuturetax

payments

(Wilson 1996). In particular,oncea plant beginsto operateata siteitcan be costly tochangeitslocation,becauseofthe"sunk" nature of

many

industrialinvestments(seee.g.,Goolsbee

and Gross2000

andRamey

and Shapiro 2001).The

resultingimmobilitymakes

firmseasytargets for localtax collectors. Sinceitisdifficult for

governments

tocrediblycommit

inadvancetofuture taxrates,theupfront tax incentives

compensate

firms for future expropriation.Allofthe previoustheories areconsistentwith local politicianssolelyacting inthe interestsof

theircitizens,but an alternative

view

isthatlocal incentivesare dueto corruption and influence or adesire on the politician's part to

maximize

the size ofgovernment. In the case ofcorruption andinfluence, theside-payments

may

occur throughdirectpayoffs,contributionstore-election campaigns,orfuture

employment

for politiciansortheir friends or family (Glaeser2001).The

magnitude ofthesebribes will

depend

on

theprobability ofdetection and the punishment.An

alternative possibility isderived fromthe Leviathan

view

ofgovernment

(Brennan andBuchanan

1980).As

applied tothiscase,politicianswillseekto

maximize

thewelfareoftheircitizensandthe sizeofgovernment

or the tax base.Forthepurposesof ourpaper,itisworth notingthatthefirstsetof

models— where

localsubsidies aremotivated by agglomerationeconomies

or increasesinproducersurplus orcompensationforex-postexpropriation--suggest that subsidies

may

be welfareenhancing or,atleast, neutral forlocal residents.(We

willshow

laterunderwhat

conditionssubsidiescan be welfareenhancingorwelfareneutral.)The

secondsetof

models— where

localsubsidiesreflectgovernment

officials' private interests—suggestthatsubsidies

may

be welfaredecreasing.We

returnto thispointinSection II,where

we

incorporatethesetwo

alternativeviewsinasimpletheoreticalframework.B.

A

Case Study

oftheBMW

PlantLocation

Decisionand

aNew

Research

DesignInthissubsection,

we

use a concreteexample

to illustratehow

aparticularfirmselected asiteforits

new

plant. Inparticular,we

useinformation fromthe"Million DollarPlant""seriesinthecorporaterealestateJournal Site Selection to describe

BMW's

1992 decision to site a manufacturing plant in theGreenville-Spartanburgareaof SouthCarolina. Notably,thisis

one

oftheplantsinour sample.A

secondgoal ofthiscasestudyis tohighlight theempirical difficulties that arise

when

estimating the effectofplant openings on local economies. Further,

we

use this case study to informally explainwhy

ouritisalsopossiblethat the

new

firmgeneratesconsumersurplusforthe residents. The consumergainsarepossibleifthere are local marketsforoutputs(e.g.,sportsteams).Because

we

focusmainlyon manufacturingplants, thisresearchdesign

may

circumventthese identitlcation problems.A

more

formalanalysisisconducted in SectionII.Afteroverseeinga

worldwide

competitionand considering250

potentialsites foritsnew

plant,BMW

announced

in 1991 that they hadnarrowed

the listofpotential candidatesto 20 counties. Sixmonths

later.BMW

announced

thatthetwo

finalists inthecompetitionwere

Greenville-Spartanburg, SouthCarolina,andOmaha,

Nebraska.Finally,in1992BMW

announced

thattheywould

sitetheplantin Greenville-Spartanburgand thattheywould

receivea package ofincentives worth appioxiniately $1 15millionfunded bythestateandlocalgovernments.

Why

didBMW

choose Greenville-Spartanburg? Itseems

reasonable toassume

thatfirms areprofitmaximizers and chooseto locate

where

their expectationofthepresent discounted valueofthestream offutureprofitsisgreatest.

Two

factorsdeterminetheirexpectedfutureprofits.The

firstistheplant'sexpected future costsof production inalocation,

which

isa function ofthe location'sexpectedsupplyofinputsandthefirm'sproduction technology.

The

secondfactoristhepresentdiscounted value ofthesubsidyitreceivesatthesite.The

BMW

case provides arare opportunitytoobservethedeterminants ofthesetwo

keysite-selection factors. Consider first the county's expected supply of inputs. According to

BMW,

thecharacteristics that

made

Greenville-Spartanburgmore

attractive than the other250

sites initiallyconsidered were: lowuniondensity,asupplyofqualifiedworkers;the

numerous

global firms,including 58German

companies, in the area; the high quality transportation infrastructure, including air, rail,highway,andportaccess;and accesstokeylocal services.

For our purposes,theimportantpointto note hereis thatthese countycharacteristics are afirst

potential sourceofunobservedheterogeneity.

While

these characteristics are welldocumented

intheBMW

case,they aregenerallyunknown.

Ifthese characteristics also affect theoutcomes

ofinterest(i.e.,labor earnings, property values and countyfinances), astandard regression that

compares

Greenville-Spartanburgwith the other

3000

US

countieswillyieldbiasedestimatesoftheeffectofthe plantopening.A

standard regression will overestimate the effect ofplant openings on outcomes, if for example,countiesthathave

more

attractivecharacteristics (e.g.,better transportation infrastructure)tend tohavebetter

outcomes

(e.g.,higherearnings).Now,

considerthesecond determinant ofBMW's

decision, the subsidy.The

BMW

"Million Dollar Plant" article explainswhy

the Greenville-Spartanburg and South Carolina governmentswere

willingto provide

BMW

with$115

million insubsidies." According to local officials, the facility'saccountforopportunitycost).

As

apartofthis$2billion,the plantwas

expectedtocreate2,000directjobsandleadtoanother 2.000 jobsinrelated industriesbythelate 1990s.''

As

we

arguedinsubsection A, Greenville-Spartanburg's subsidy forBMW

may

be rationalized by the2000

"spillover" jobsindirectly created bythe

new

plant.As

anexample.Magna

International beganconstructionon an$80

millionplant that

was

toproduceroofs,side panels,doorsandothermajorpieces for theBMW

plantin1993.'^

It is notablethat

some

countiesmay

benefitmore

from a particularplant, depending on theirindustrialstructure,labor force skills,

unemployment

rateand

alltheother factorsthat affect spillovers.Forthis reason, the factors thatdeterminethetotalsizeofthe spillover(andpresumablythe sizeofthe

subsidy) represent a second potential source of unobserved heterogeneity. If this unobserved heterogeneity is correlated with outcomes, standard regression equations will be misspecified

due

toomittedvariables, just asdescribedabove. Forexample, ifcounties thathave

more

to gain intermsofspillovers(andtherefore offer

more

generoussubsidies) alsohave

betteroutcomes,thenaregression thatcompares

thewinners withtheother3000

US

counties willoverestimatethe effectofplantopeningson

outcomes.

Inorderto

make

validinferencesinthepresenceofthesetwo

formsofheterogeneity,knowledge

oftheexact form ofthe selection rule thatdeterminesplants' locationdecisions isgenerallynecessary.

As

theBMW

example

demonstrates, thetwo

factors that determine plant location decisions—

theexpectedfuturesupplyofinputsinacountyandthe

magnitude

ofthesubsidy—aregenerallyunknown

toresearchersandinthe rarecases

where

theyareknown

theyaredifficulttomeasure. Inshort,we

havelittlefaith inourabilitytoascertainand

measure

allthisinformation. Thus,the effectofa plantopeningis very likely to be

confounded

bydifferences in factors thatdeterminethe plants" profitabilityat thechosenlocation.

As

a solution to this identification problem,we

rely on the revealed rankings ofprofit-maximizing

firmstoidentify a valid counterfactual forwhat

would

havehappenedin theabsence oftheplantopening. In particular,the"MillionDollar Plants"articlestypically report thecountythatthe plant

chose(i.e.,the 'winner'), as well asits2"''choice(i.e.,the'loser'). For example,inthe

BMW

case,theloseris

Omaha,

Nebraska. Inthesubsequentanalysiswe

assume

that thewinning andlosingcounties areBen

Haskevv,chairman ofthe SpartanburgChamber

ofCommerce,

summarizedthe localviewwhen

hesaid,"Theadditionofthe

company

will furtherelevatean already top-ratedcommunityforJobgrowth"(Venable, 1992,p.630).

'"Interestingly,

BMW

laterdecidedtoopenasecondplantintheGreenville-SpartanburgareaandrelocateditsU.S.

headquartersfrom

New

JerseytoSouth Carolina.''

Althoughthe

Magna

Plantwasslated tohire300workers,stateandlocalgovernmentsonly providedabout $1.5million in incentives. Interestingly, the incentives offered to

Magna

are substantially smaller (even on aproportional basis) than those received by

BMW,

implying that local governments appear to be judicious inidentical in expected t'utiiie proHts. controlling for dilTcrcnccs in pre-existing trends. Although this assumption is unlikely to hold exactly,

we

suspect that this pairwise approach is preferable to usingregressionadjustmentto

compare

thewinnerstothe other3,000 U.S. counties or amatching procedurebased

on

observable variables.'' In Section V,we

present empirical evidence thatsuggests that thisidentifyingassumption

may

bevalid.II.

Laud

Pricesand Wellare

When

Counties

BidsforPlantsThissection presents asimple

framework

thatguidestheempirical analysisandhelpstointerpretthe resulting estimates.

One

ofthe paper'sempirical goalsisto testwhetherthe successful attractionofanew

plant affects housing prices.The

tlrst subsection presents a stylizedmodel

thatspecifiessome

assumptions under

which

thechange

in landvaluesinduced bytheexogenous

opening ofaplantcan beinterpreted as a

change

inresidents' welfare. Inthesecondsubsection,we

allowcountiestobid for plantsandspecify

some

assumptions aboutthebidding process.The

goalofthissubsection istoshow

underwhat

conditionsasuccessful bidfora plantwill result inhigher or lowerproperty values(andtherefore welfare).A.

Land

Pricesand Welfare

Here,

we

followthe stylizedRoback

(1982) model,which

isoftenused tomodel

firm locationdecisions.

We

assume

that individualsareperfectlymobile,haveidenticaltastesandafixedlaborsupply.Further,theyrentlandfor

homes

inthecountywhere

theywork. Allfirms areassumed

tohave constantreturnstoscaletechnologiesandthere isa fixedsupply oflandineachcounty.''^ Inequilibrium, firm's

unitcostsequalthe nationally determined productprice andindividuals' utilitycannot be increasedby

moving

toadifferentcounty.Now.

supposethatacountyisexogenouslv assigned anew

plant. This casemay

beunrealistic,butitisauseful startingpoint forexpository purposes. Importantly,allotherproducersandall workers

continuetochoosetheir location to

maximize

profitsandutility,respectively.The

openingofthenew

plantcauses landvaluesandnominalwages

to increase inthecounty.The

increaseinlandvalues occursfortworeasons. First,thenew

plantwilldirectly increase thedemand

through itslandpurchase and byincreasing the

number

ofworkerswho

need housing. Second,ifthere areagglomerationeconomies,thepresenceofthenew

plant will lowerthe costs of productionforother'*

Propensity scorematchingisan alternativeapproach(Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983). Itsprincipalshortcoming

relative toourapproachisitsassumptionthatthetreatment(i.e., winnerstatus)is"ignorable" conditional onthe

observables.As itshould beclearfromtheexample, adjustmentforobservablevariablesthroughthepropensity

scoreisunlikelytobesufficient.

firmsinthecounty. IntheparlanceofRoback,thisis referredtoas aproductive amenity. And,inthe

presence ofaproductive amenity,firmswill bidupthe priceoflandtogainaccesstothe spillovers. In

order to retainworkers,firms

must

pay higherwages

tocompensate

them

forthe higherrental rate ofland,sothatreal

wages

areunchanged. Thisisnecessary becauseinequilibriumworkers'utilitymust beconstantacrosscounties.

With

thisset-up,the increase in landvalues providesaone-timegaintoproperty ownersinthecounty that receives the

new

plant. This is the only change in welfare experienced by the county'sresidents. Thisis becausethe increasein

wages

isoffsetbythehigherprices thatworkersfacetorentland(e.g., forapartments/houses), leaving theirutility isunchanged. Further,thehigherrental rateof

landcounterbalancesanyspilloversavailable totlrms. Thus, undertheseassumptions,changesin land

values translateone-to-oneinchangesinresidents'welfare.

B.

A

StylizedModel

ofBidding

forPlantsand

Land

Values

In theprevious subsection, the opening ofa

new

plant increased property values becausewe

assumed

that the county does not have to incur any costs to attract the plant. In practice, localgovernments

frequentlyprovidesubsidiesinexchange

foraplant'slocationdecision. In thissubsection,andtheremainderofthe paper,

we

considerthe possibility that the3,000 U.S. countiescompete

forthenew

plantby

offeringsubsidiesor bids.We

assume

thatacounty'sresidents electamayor

thatacts as theiragenttobidto attractplantsto itsjurisdiction.

A

successful bid involves a trade-off for thecounty.On

theone

hand, subsidies arecostly to thecounty,because they involvetheprovisionofservicesand

may

reducethe futurestreamoftaxrevenues.

The

increaseinpublic services includes the special services for thenew

plant stipulatedbythe incentive

package

(e.g.,theconstructionofroads,or other infrastructureinvestments,taxabatements,job training funds, provisionof low-cost or free land, the issuanceof tax-exempt bonds, provision of

cheap electricpower, etc.), as well as the standardpublic services (e.g., garbage removal and police

protection).

We

assume

thatthecounty'sincentivepackageisfinancedby propertytaxes,so thatitscostiscapitalizedintoland values.'"

On

theotherhand,thenew

plant directly increases thelevelofeconomic

activity inthecounty,which

raisesthevalueofland.As

theBMW

case demonstrates,thepresenceofthenew

plantmay

alsoraisethevalueof landindirectlyby generatingspillovers, if,forexample, itattractsother plantsand/or

lowersthe costsof production forother plants. Thus, property values capitalizeboththe costs(i.e.,the

IntheAnnual Survey of Governmenisdata,property taxesaccountfor

49%

oftotalrevenuesfromown

sources.increasedpropertytaxesand/or reducedservices)and beneHts(i.e., tiie increased

economic

activity)ofattractingtiicplant.

Tiiissubsection's goal isto theoreticallyanalyze

when

thesuccessful attractionofa plant willincrease ordecrease property values (and therefore welfare) in the presence of county bidding.

We

denotepropeityvaluesasP,and

assume

thatthechangeinproperty valueslorthewinning county can be expressedas AP,,=

Vi|-

C,j. Vi,denotesthebenefitofnew

plantjforcountyi,anditiseqiiivalenttotheincreaseinpropertyvalues(intheabsence ofa subsidy).

The

sizeofthisbenefitisexogenous

andknown

tothecounty.

We

alsoassume

thatitisknown

toallthe othercountiesbiddingon

theplant.Cy

isthe costtothecounty ofthesubsidyprovidedtotheplant.Intherealworld,itisoften thecasethatthestatebears partofthecostofthe incentivepackage. In this case thetotal subsidy received by the plant is B,,

=

Cij + Sj,,where

Sy denotesthe state'scontribution.

We

assume

thatSisexogenous

tothecountyandisprovided bythe statetoaccountforthebenefitstoother countiesinthestate.

The

plantsaretheother sideofthistwo-sided matchingproblem andwe

assume

thatthey willlocateinthecounty

where

theirfutureprofitsaremaximized.As

describedabove,two

factorsdeterminetheirexpectedfuture profitsinagiven county:thesubsidyandtheexpectedfuture costsof productionin

thatcounty. Itislikelythatthereis heterogeneityinthe

maximum

subsidythat countiesare willingtooffer,

due

to differences incounties characteristics (recall Section I-B). In orderto obtain thehighestsubsidy,

we

assume

thatthefirmsconduct an Englishauction inthepresenceof independent,or private,values.

We

furtherassume

thatthereisnotanycollusioninthebiddingamong

counties.The

firm'schoicealsodepends onthe location-specific productioncosts. Itislikelythatthereisheterogeneityinaplant's valuationof a countyduetodifferences intheexpected supply offuture inputs.

Inthe

BMW

case,recallthese factorsincludedthepresenceofqualifiedworkers,thepresenceofGerman

companies

andair, rail,highway,andport access.We

denotethevaluetothefirmofallthese factors asZ,j.

A

higherZy implies thatproduction costsoffirmj are lower incounty i.We

assume

thatZ

isexogenous

tothecountyandisknown

toallcounties.We

alsoassume

each county hasrational expectations aboutthe plant'sproductioncostsinallother counties,(i.e.,Z,jforall i)andallother counties' bids(i.e.. B,,forall i). This assumption prevents

finns from increasing the subsidy that a count)' offers b\- exaggerating the benefits oflocating in a

differentcounty. If thisassumptionis incorrect, it

would

causecountiesto"overbid." Itisnotevidentwhy

such overbiddingwould

be an equilibriumstrategy.Overall, thetotalvalueforafirmoflocatingina particularcountyisthe

sum

ofthesubsidyandthe county-specific costadvantages. It

seems

reasonabletopresumethata plant will select thecounty1.

Homogeneous

Counties. Ingenera],counties differintheirvaluationsofanew

plant,Vy,andtiie plants' valuation ofthe county, Z,j. Here,

we

begin by considering the casewhere

counties arehomogeneous

inV

andZ: Vi,= Vq

andZjj=

Zqforall i. Thiswould

be thecaseifour keyidentifyingassumptionthatwinners andlosers are identical

were

valid.The homogeneity

caseisimportantbecauseinourempirical analysis,

we

willretainthehomogeneity

assumptionwhen comparing

winnersand

losers.Later,

we

analyzethemore

generalmodel

thatallowsforheterogeneityinV

andZ

toinvestigatehow

ourconclusions differ ifthis identification assumption is not valid.

Under

homogeneity,the firmsimply choosesthecountythatoffers the highest subsidy, B.We

considerfour cases.Case

J. This caseis the simplest.We

assume

thatthecounty'smayor maximizes

residents'welfare andthe stateprovides

no

subsidy (i.e.,S=

0).The

mayor

raisesthe biduntilsheisindifferentbetween

winning andlosing. Formally,theequilibriumbid,B*,isdetermined by(!)

B* = Vo

Consequently,

AP

= Vo

-

B* =

andthesuccessful attractionofthe plantdoesnotchangeland pricesor residents' welfare.Case

2.We

now

allowstatestosubsidizethe incentivesofferedtothe plant butretaintheotherassumptions. Itispossible that different states providedifferentlevelofincentives if,forexample,the

magnitude

ofspilloversinneighboring countiesdiffersacrossstates. Here, thecountythatreceives themost

generousincentivefromthe state willwin

thenew

plant.The mayor

ofthecountylocated inthemost

generousstatedoesnotneedto raisethe biduntilsheisindifferentbetween havingtheplantand

nothavingtheplant.

She

canwin

the plantby

settingthecounty'sbidatthepointthatmakes

themayor

ofthecounty with thesecond

most

generous statesubsidy indifferentbetween

winning and losing.The

optimalbid

B*

is(2)

B* = Vo +

S™,.,where

S,„;,^.|istheincentiveprovidedbythesecondmost

generousstate.Specifically, landvalues increase bythedifference betweenthe statesubsidy provided bythe

most

and 2"''most

generousstates:

AP

= Vq -

(B*-S|„.ix)=

S^ax -Sn.ax-i>0,where

S,„axistheincentiveprovided bythe

most

generous state. Importantly, thesource ofthe increase inhousingvalues istheheterogeneityinthestatesubsidiesandthecounty'scaptureofpartofthestatesubsidy.

Case

3.We

now

allowforthe possibility that themayor ma\

haveherown

goals. Inparticular,we

assume

themayor

benefits from a higher incentive package because opportunities forgraft orenlarging

government

are increasing inB.We

definethispersonal benefit asT

=

f(B),withf

>0: thehigherthe subsidy providedbythe

mayor

tothe firm, the larger thekickback.Due

toan exogenously determined probability ofdetection and punishment, themayor

choosesB

tomaximize

herutility U,>

0. Inthecasewhere

U2=

0,thereisnoprincipal-agentproblem andthemayor's andresidents'interestsare perfectly aligned. IfU2

>

0,themayor'sobjectivefunction includes residents'welfareaswell asherown

privategainfromthesubsidy. Forsimplicity,we

assume

thatU(AP,T)

isseparableinitsfirstandsecond

argument

andT

isafixed fraction yofthebid(i.e.,T

=

y B),where

<

y<

I. Thus,U

=

AP

+

yB.We

assume

Ut;<: but reinstate theassumptionthatstatesdonot subsidi/.c the bid(i.e.S=

0). Inthiscase,the

ma)or

raisesher bidtothepointthatmakes

herindifferentbetween havingtheplantandnothavingtheplant. Ifallthe

mayors

behaveinthesame

way,themayor's optimalbidis(3)

B*-Vo/(l-y)

In this case, the

mayor

overbids, by choosingB* which

is larger than the value ofthe plant to theresidents. Such overbidding causes landvalues inthe winning countytodeclinerelative to thelosing

county.

The

magnitude ofthedeclinedepends onthemayor's weight on herown

welfare:AP=

-(y/(1-y))

Vo <

0.Cose

4.When

U2 ^

andthereisa positive statesubsidy(i.e.,S,|>0),thechangeinland pricescannotbesigned.

The

statesubsidyincreases land values, asshown

aboveincase2,but theinclusionofthemayor's personal gain in the objective function results in adecrease in land values as in

Case

3.Depending

onthe magnitude ofthesetwo

effects, landvaluesmay

increase or decreaseinthe winnerrelativetotheloser.

'^

2.

Heterogeneous

Counties.Although

the key assumptioninourempirical analysisis thatthewinning and losing counties are

homogeneous,

it is important to understand the consequences ifthis assumption isnotvalid. Here,we

allowforheterogeneityincounties' valuationsofattracting the plant,V,andplants" valuations ofcounties, Z. Insection I-B,

we

usedtheBMW

example

toarguethattheeffectofthe plantopening could be

confounded

bythesetwo

sourcesof unobservedheterogeneityacrosscounties. Specifically,

we

suspect that a naive estimator that ignores the presence ofunobservedheterogeneitywillbebiased. This subsection formalizesthispoint.

Forsimplicity,

we

retaintheassumptionsthatS.j=

andUj=

0.IfV

andZ

vary across counties,the firmchooses

where

tolocatebasednotonlyonthebidB, but alsoon Z. Specifically,the valueforfirmj of choosing countyi isBii+Z,,.

Assume

for simplicitythatthere areonlytwo

levelsof V, highV

(Vh) and low

V

(Vl);andtwo

levelsofZ,highZ

(Zh)and low

Z, (Zl). Considerfirstthecasewhere

V

and

Z

are positively correlated,sothatthecounty with highV

alsohas highZ. Thus,one county willgainthe most fromattracting firmj andisalso theleastcost productionlocation forfirmj. Itsoptimal

bidissuchthatthecounty with

low

Z

and lowV

is indifferentbetween havingthe plantandnothaving(4)

B* =

Vl-(Zh-Zl).

In this case,thecountythat isthe best

match

enjoys a rent thatis capitalizedintoland values.Land

valuesincreaseby anamount

proportionaltothedifferenceinV

andthedifferenceinZ:AP

= (Vh

-Vl)

+

(Zh -Zl)>0. Importantly, the increaseinlandvaluesisduetotheunderlyingdifferencesinV

and

Z.

Consider

now

thecasewhere

V

andZ

are negatively correlated.County

1 hashighV

andlow

Z;whilecounty2hashigh

Z

and low V.IfVh+Zl >

Vl

+

Zh, county1 winsthe plantby bidding anamount

B*

thatmakes

county 2indifferentbetween havingthe plantandnothavingtheplant:(5)

B* =

V,.+ (Zh-Zl)

The

winner county enjoys arent thatiscapitalizedinland values,althoughthe rentislowerthan the rentinthecaseofpositive correlationbetween

Z

and V:AP

= (Vh

-Vl)-(Zh-Zl)>0.A

similarconclusionappliesif

Vh+Zl

<

Vl

+

Zh-In thiscasecounty 2isthewinner anditsland prices increasebyAP

=

(Zh-Zl)-(V|i-Vl)>0. Again,theheterogeneityisthesourceofthechangeinprices.'^

The

implications forourempirical analysis arediscussedfurtherintheeconometricssection.

III.

Data

Sourcesand

Summary

StatisticsA.

Data Sources

We

implement

thedesign usingdataon winning andlosing counties. EachissueofthecorporaterealestatejournalSite Selectionincludesanarticle titledthe"Million DollarPlants" thatdescribes

how

alarge plantdecided

where

tolocate."These

articlesalwaysreport thecountythatthe plantchose(i.e.,the'winner'),andusually report therunner-upcountyorcounties(i.e.,the "losers").""

As

theBMW

casestudy indicated,the

winner

andlosersareusuallychosenfrom

an initialsample of""semi-finalisf"sitesthat in

many

casesnumber more

than ahundred."'The

articles tendtofocusonlarge plants, and ourimpressionisthatthey providea representativesample ofall

new

large plantopeningsin theUS.The

articles usually indicate the plant's output,

which

we

use to assign the plant to the relevant 1-digitindustry.

In thiscase,theoptimalbidisB* =(Vo+S^m-i)/(l-y).The changeinlandpricesis

AP=

-(y/(1-y))Vo+

S^iK-(i/(i-y))S„,ax-,.

'^

Inthe unlikely casethat

Vh

+ Zl =Vl

+Zh,the twocounties areequivalent, and the winneris randomlydetermined.

In1985,thejournalIndiistiialDevelopment changedits

name

to Site Selection. Henceforth,we

refer toitas SiteSelection. Also,insomeyears thefeature ""MillionDollar Plants"wastitled"Location Reports."

"°

Insomeinstancesthe"Million DollarPlants" articlesdonotidentifytherunner-up county. For thesecases,

we

dida Lexis/Nexis searchforotherarticlesdiscussingthe plantopening and in 4caseswereabletoidentifythe

losingcounties. TheLexis/Nexis searcheswerealsousedtoidentifythe plant's industry

when

thiswasunavailableinSiteSelection.

"'

These

data havetwo

important limitations. First,the magnitude ofthe subsidy offeredby thewinning counties is in

many

cases unobserved and the bid is almost always unobserved for losingcounties. Thisisunfortunate,because aninterestingcheck ofthe validityof ourresearchdesign

would

betotestwhetherthe subsidies offered areequalinthewinning andlosing counties. Second,in

many

cases thearticlesdonot report theexpectedsizeoftheplant.In ordertoconductthe analysis,

we

collectedthemostdetailedand comprehensivecounty-leveldata available on

employment, government

finances, and property values available for theperiod from1970 through 1999.

The employment

datacomes from

theCensus

Bureau'sCounty Business Patterns(CBP)

datafile.These

annualdata report thenumber

ofemployees

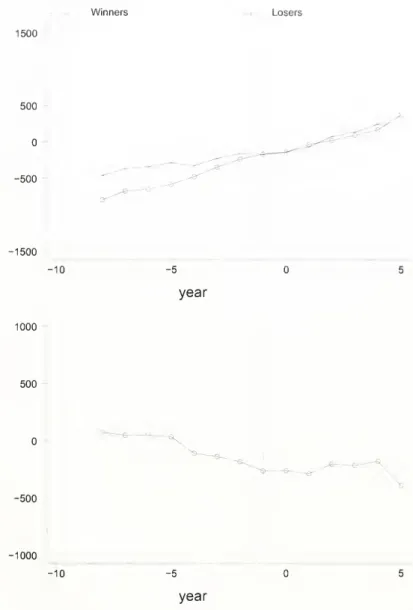

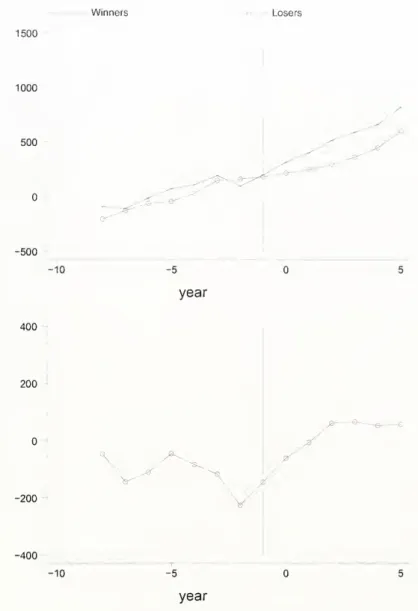

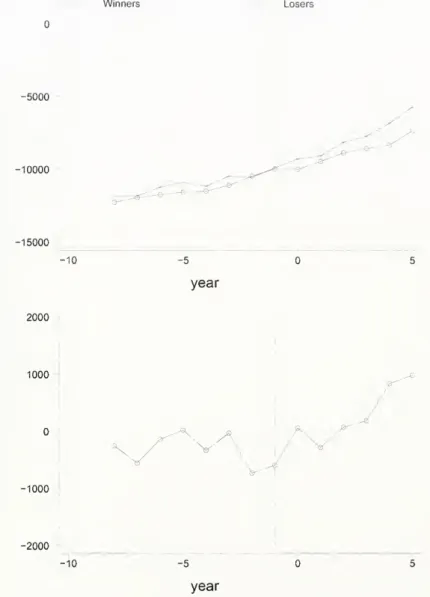

andthetotalwage

billatthecountybyindustrylevel. Inordertoprotect the confidentialityoftherespondents,thesedata are"zeroed out"for

many

industry by countycells. Consequently,we

conduct ouranalysisatthe 1-digitindustryby countylevel."

The

CBP

data are usedto test whethera plantopeningisassociatedwithchangesinwage

billtrends in its industry, as well as other industries.

We

focuson

thetotalwage

bill rather than totalemployment

since thelattercannotdetectchanges intheskillcontentoflabor. Unfortunately, theCBP

does notreporthourly wages.

We

also test whether the successful attraction of a plant affects property values.^^We

areunaware

of anyexisting electronicfilesof annual county-level property valuedata,sowe

createdourown

county

by

year datafileon

property valuesfromtwo

sources. First,we

contactedallthestateand countygovernments

inour winnerandlosersamplesdirectlyand

requestedalltheir historicaldataon propertyvalues."''

These

data existbecause governments determinethevalue of propertyintheir jurisdictions for thepurposeof assessing propertytaxes. ,Second,

we

supplementedthese databyhand

enteringdatafromthe1972, 1977, 1982, 1987. and 1992Census of

Governments.Volume

2 TaxableProperty Valuesand

Assessment-Sales PriceRatios.The

censusesreportsmarket valuesintheyear beforeeach censuswas

conducted. In yearswhere

datawas

unavailable from both sources,we

estimated county-level property valuesbylinearly interpolating theCensus

ofGovernment

data,which

likelycausesthe true variationtobeunderstated.Forthepurposesoftheanalysis,

we

divide outputintothe5broad"1-digit" industriesdefinedbytheCBP

forwhich uncensored

wage

billdata areavailableinmostyears. Theseindustries are: Manufacturing; TransportationandPublicUtilities;Trade(Wholesaleplus Retail);Finance, Insurance,andRealEstate; Services. Atthis levelof

aggregation,1

7%

ofthecellsare"zeroed"out.^^

Ideally,

we

would havealsoexaminedthe effecton propertyrental rates,butwe

wereunabletofindasourceforannual or otherhigh frequencyrentaldata.

^''

We

attemptedtogetthisdatafortheprimarysample of 166countiesdatingbacktothe early1970s.

We

collectedatleast1yearofpropertyvalue datafrom 153counties. Ingeneral,thesegovernmentsdidnothavedatafromthe

earlier years. Forexample,

we

have nonmissing property value datefor68countiesin 1977, 102in 1980,149in1990,and153in1998.

One

limitationofthesedataisthatourmeasure of property valuesisthesum

ofthevaluesoflandandstructuresacross residentialandindustrial land.

The drawback

ofthismeasure

of property values isthatitwillinclude thevalueofthe

new

plants' structures,which

mechanically causesmeasured

propertyvaluestoincrease. Unfortunately,aseriesforland valuesonly isunavailablefor

many

ofthecountiesinoursample. Thisissueisdiscussed

more

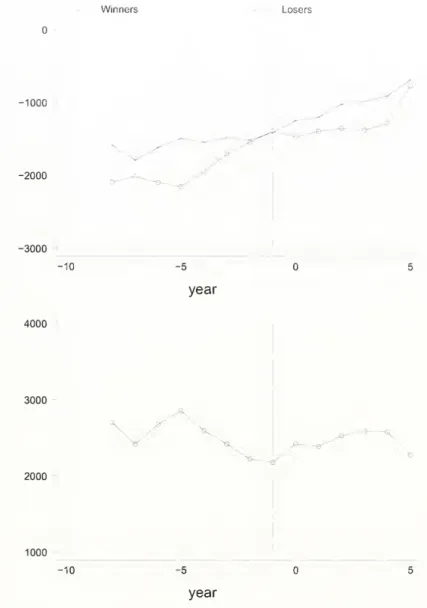

extensivelyinthesubsequentdescriptionofthepropertyvalue results,butwe

note herethattheestimatedincreaseinpropeityvaluesappearstobesubstantially larger thanany reasonable estimate ofthemean

valueofnew

plants'buildings.Despite our extensive data collection efforts, the property value data are missing for

some

counties.

Our

preferredpropertyvaluesample

iscomprised of 30 ofthe82 winnersand62 ofthe 129losers.

The

DataAppendix

providesmore

detailsonthepropertyvaluedata.The

Amntal

Surveyof Governments:

FinanceStatistics Series(ASG)

is used todetermine thefiscal consequences for local

governments

ofnew

plant openings.The

ASG

is an annual survey ofgovernments

that asks detailed questions on governments' expenditures by function (e.g., education,administration,and publicassistance) and type(i.e., intergovernmentaltransactions, current operations,

andcapital outlays).

The

data alsocontains information on revenuesby

source, indebtedness, andcashandsecurities holdings.

We

aggregatethese datatothecounty level. This aggregation isdone

onthesample

of

governmentalunitsthataresurveyed continuouslyfrom 1970 through 1999so that the units areheld fixed. Inour "Million DollarPlant"

sample

of 166winningandlosing counties,150countieshaveatleast

one

governmental unitthat reportscontinuously.The

continuousreporterscomprise only12.5%

of all governmental units in these counties but account for approximately

75%

of revenues andexpenditures. Thisisbecauselarge

government

unitsaresampled withcertainty,while smallerunitsaresampled with "varying probabilities within an area,type ofgovernment, and size ordering" (Census

Bureau, 1990,p.1-1)."

B.

Summary

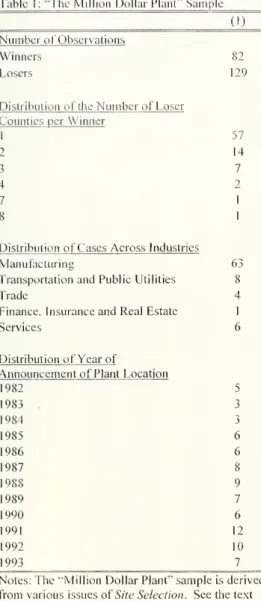

StatisticsTable1 presents

summary

statisticsonthesample ofplantlocation decisionsthatformthebasisofthe analysis.

The

firstpanel indicates thatinourprimarysamplethere are82separate plantopeningsand an average of1.6 losersperwinnerora totalof 129losers. Thereare 166countiesinthissample,so

According to the data documentation, the following governments are sampled with certainty: "all county

governments withapopulationof 50,000ormore, municipalgovernmentswithapopulation of25,000ormore;

townshipgovernmentinthe

New

England andMiddleAtlantic stateswith a populationof25,000ormore; schooldistrictswith an enrollment of 5,000ormore;andspecial districtswithlong-term debt outstanding of$10million,or

theaveragecounty appears roughly 1.3times.'"^

The

secondpanel reports the distributionofthe niuriber

oflosers per winner.

We

refer to the winner andaccompanying

loser(s) associated with each plantopening

announcement

asa "case." In 57 ofthe 82 cases thereis asingle loserand in 14there are2 losers.The

table alsoreveals that63 ofthe 82 plantswereinthe manufacturing industry. Thus, ouranalysisis

most

informativeabouttheconsequences ofattracting industrialplants.The

final panel liststhe distributionoftheyearofthe

announcement

abouttheplantopening. 22 ofthe plantopeningswere

announced

in1991 and 1992,suggestingthattheymay

be countercyclical. Appendi.x Table2 reports theidentityof eachplant,itsindustry,andthewinning andlosing counties.

Although

we

do

notknow

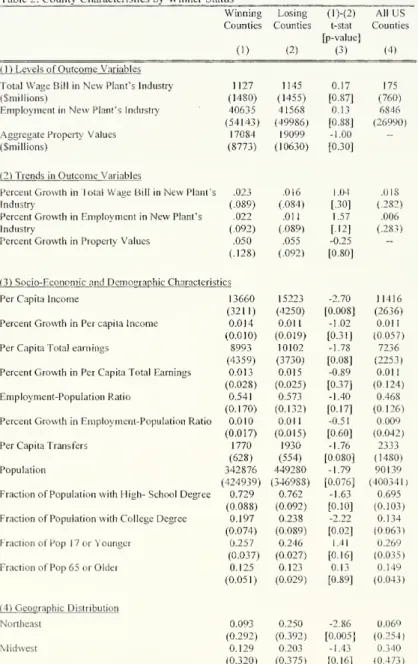

thedeterminants ofthecounties'valuationsofplants(i.e.,V,j)or theplants' valuations of counties (i.e., Z,j), Table 2 presents the

means

across counties ofsome

likelydetenninantsofthese variablesinthe threeyearsbeforethe

announcement

ofthe plantopening.These

means

arereported forwinners, losers, andthe entire U.S. incolumns

(1),(2), and (4),respectively.^'Column

(3) presents thet-statisticand p-value fromthetestthatthe entries in(1)and(2) are equal.We

e.xpectthatwinning andlosingcountiesaresimilar sothatanydifferencesin

columns

(!)and(2)willbesmall. Incontrast,

we

expectthat acomparison ofthewinners(or losers)withall U.S.countiesislikelytoproducelargerdifferences.

The

firsttwo

panelsreveal that thewinning andlosingcounties are similarinboththe levelsandpre-announcement

trendsoftheprimaryoutcome

variables. Specifically,thefirstpanelreportsthemeans

ofthree

outcome

variables inthe three yearsbeforetheannouncement

ofthe plantopening.The

mean

total

wage

billinthenew

plant'sindustryisapproximately $1,127millioninwinningcounties,compared

to$1,145 million in losing counties. Thisdifference is notstatistically meaningful andindicates that

there

were

similar levelsofactivityinthetwo

setsofcounties.The

countoffull-timeemployees

leadstothe

same

conclusion. In contrast,thecorrespondingfigures forall theUS

counties aremuch

smaller."^The

thirdrow

ofthispanel indicates thatthehypothesisofequivalentaggregate property valuesacrosswinning andlosingcountiescannot berejectedatconventionalsignificancelevels.

The

second panelcompares

trends in theoutcome

variables in the three years before theannouncement.

The growth

ratesinearnings,employment

andlandvaluesarenotstatisticallydifferentin"*

127 counties appearonceinthedata. 33 counties appear twiceand 6 countiesarepresent threetimes.Through

theentireempiricalanalysis,

we

exclude the 7 counties with populationsexceeding 2million. Inthesecounties,itwouldbedifficult todetecttheimpactofaplantopening.

"^Thelosing

countyentriesincolumn2 are calculatedinthefollowing manner. First,

we

calculate themean

acrossallthe losers for agivencase. Second,

we

calculate the overall loseraverageas theunweightedmean

acrossallcases sothateach caseisgiven equal weight.

"^Thefiguresin

thetoppanelofcolumn 4are aweighted averageforyears1982to1993, with weights proportional

to thenumber ofMillionDollar casesineach yearand industry.Thefigures inpanels2to5 ofcolumn4area

weightedaverageforyears1982to1993, with weights proportionaltothenumberof Million Dollar casesineach year(seebottomofTableIforthedistributionof cases acrossyears).

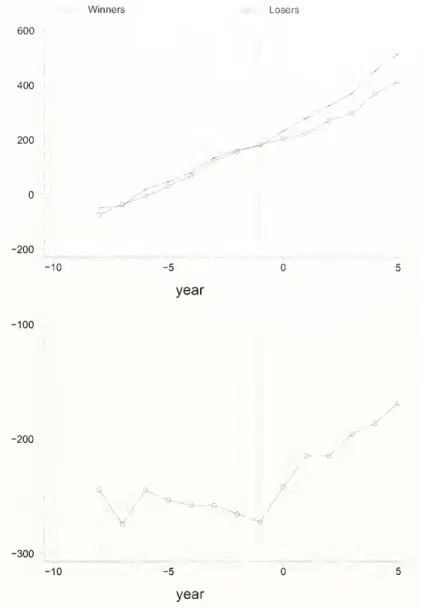

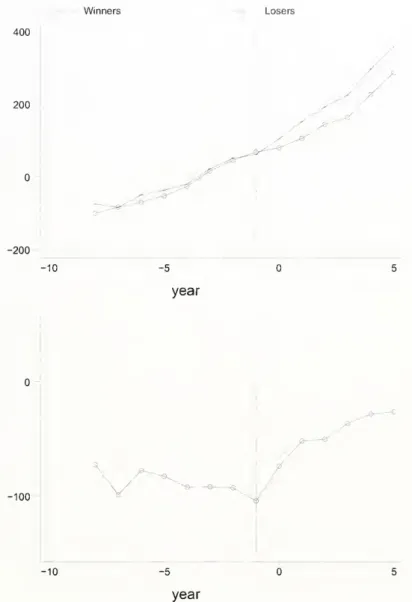

winning

andlosing counties.We

return tothis issueinSection V,wiierewe

graphicallyshow

thatthetrends in

wage

bill,employment

and land valuesinthe 8yearsbeforetheannouncement

aresimilarinwinning and losing counties.For

now,

we

notethatthe findingthatboth the levelandgrowth rateof propertyvaluesissimilarinwinning

andlosing countiesisanespecially importanttestofthe validityofour research design, ifproperty markets are forward looking.

Under

the plausible assumption thatpropertymarketsareforwardlooking,this finding indicates that theexpectedfuturechangesinthe level

of

economic

activitycapitalized intoproperty valuesare alsoex-antecomparable. Overall, thefirsttwo

findingsprovidereassuringevidenceonthe qualityofthisresearchdesign

The

thirdpanel reportsmean

levelsand changes of socioeconomic anddemographic

variables. Ingeneral, the null hypothesis of equal

means

in winning and losing counties cannot be rejected withconventionalcriteria. Thisistrue bothfor the levelsofthe variables inthe 3 yearsprecedingthe plant

opening

announcement and

the percentgrowth

in those years for selected variables. There aretwo

important exceptions

where

thep-valueis .05orless:level of percapitaincome

andfractionofcollegegraduates.

However,

forthesetwo

variables,the losers"mean

is closerto thewinners'mean

thanisthemean

acrossallU.S.countiesincolumn

(4).Furthermore,forper capitaincome,the percentgrowthisnotstatisticallydifferentinwinners

and

loserscounties. Interestingly, there areimportantdifferencesbetween

all U.S. counties

and

thewinning

counties. In particular,the winners are richer,have a substantiallylarger population,ahigheremployment-populationratio,a bettereducatedpopulation,and fewer people

overtheageof65.

The

fourthandfifthpanelsshow

thegeographicdistributionofplantsacross the fourregionsoftheU.S.andtheindustry distributionofthelaborforcewithin the categories. Here,the

means

acrossthewinning and losing counties are not wellbalanced. For example,

66%

ofthewinnersareintheSouthcompared

to39%

ofthe losers. This is potentially problematic, since it suggests thattheremay

be unobserveddifferences(e.g.,uniondensity)across thewinningandlosing counties.This findingunderscores the valueof our identification strategy's reliance

on

comparisonsofchangesin

outcomes

between

winnersandlosers,ratherthan cross sectional comparisons. In thissettingcross-sectional differences willonlybiastheresults iflevelsofthese variablesdeterminefuturechanges.

This

would

bethecaseifforexample, uniondensity predictsgrowth inemployment

andproperty values.As

thenext section discusses,we

estimatemodels

thatincluderegionby yearfixed effectstoaccountforthe uneven distribution of

winner

and losers across regions.We

also estimate models on a restrictedsamplethatis limitedtocases

where

thewinner and losercounties areboth fromtheSouth.To

previewthe results, our findings are unaffected by these specification checks, implying that the geographic imbalance doesnotexplainourresults.

IV.

Econometric

Model

In lightofthe firm's selectionrule,thegoalistoestimate the causal effectof winninga planton

county-leveloutcomes. Thissectiondiscusses the 2-stepeconometric

model

usedto estimatethis effect.Inthefirststep,

we

fitthefollowingequation:17 17

(6) Y„c,

=

aic+Yj

'^wtW.ic,+

Yj

^liLijci+

Hi,+

iiut+£,.ic.,orT=-:9 t=-i9

17 17

(6') Y,„

=

ac+

Y.

":vvtWjcx+X

J^ltLjcx+

Ht+

%

+

^.ic„where

ireferences industry,j indicates a case, cdenotes county,andt indexesyear, xalsodenotesyear, butitisnormalized sothatforeach casetheyeartheplantopeningisannounced

ist=

0."'The outcome

variableinequation(6),Y.jct,istotalwages.

The outcome

variablein(6'),Y,^,, isacounty-levelmeasure

ofproperty'values or a

government

financevariable, ^ijciand^j^,are the respective stochastic errorterms.a,c (ttc) is a full set ofindustry x county (county) fixed effects that adjust for

permanent

differencesinthe interceptofthe

outcome

variables.These

accountforall fixedcounty characteristics.|i„ ([!,) isa vectorofindicators thatnonparametricallycontrols forindustryx year(year)effects. In

some

specifications the

sample

includes the entire U.S.,while in otherswe

restrict it toour "Million DollarPlant"sample of 166counties.

The

useofthesmallersample isequivalentto imposingthe restrictionthattheindustryxyear(year) effects arethe

same

inthe 166countiesandtheremainder ofthecountry.Hut(t1it) isasetofseparate fixed effects foreachofthecasesinteractedwith anindicator forwhetheri

>=

-8andt<=

5.We

restrictattention tothesevalues ofi,becausethe sampleis balanced overthisrange.

W,,eT and Wj^^^^are indicator variables. Wjjct(Wj^O equals 1 forobservationsonthe

new

plant'sindustr>' inwinning counties (the

new

plant's county)foragiven valueofi. L,|ct and Lj^taredefined analogously forlosing counties. Inthecaseswithmultiplelosers, thisindicatorvariablewillequal 1 forobservationsfrom multiplecountieswithinacase.

The

vectorsttv, and Klaretheparametersofinterest inthese equations.They

measuretheperiod-specific

means

ofthedependentvariablesinwinningandlosing counties, respectively,where

themeans

are conditionalonalltheindicatorvariablesdescribed above.

The

periodisdeterminedbytheyears since(oruntil)the plantopeningannouncement. Thus,the effectof