Politique et préjugés :

l'influence des stéréotypes liés à

l'ethnicité, au genre et à l'âge sur le comportement

politique / Politics and Prejudice : The influence of

ethnicity-based, gender-based, and age-based

stereotypes on political behaviour

Thèse

Joanie Bouchard

Doctorat en science politique

Philosophiæ doctor (Ph. D.)

Résumé

Cette thèse s’intéresse à l’impact du genre, de l’âge et de l’ethnicité des chef·fes de partis au Canada sur la réception de leur candidature par les électeur·rices. La perception sociale est intrinsèquement relationnelle et met autant en scène l’identité du/de la candidat·e que de l’électeur·rice. Par conséquent, cette thèse s’attarde à la fois au profil sociodémographique des chef·fes de partis et des électeur·ices qui sont appelé·es à les évaluer. Ce faisant, elle contribue aux champs des études électorales et de la psychologie politique.

Trois méthodes complémentaires sont employées. La première partie de la thèse s’appuie sur une analyse quantitative de données électorales fédérales (1988-2015) ainsi que dans trois provinces canadiennes (Québec (2012-2014), Alberta (2012) et Colombie Britannique (2013)). Elle s’intéresse à l’évaluation des chef·fes de partis ainsi qu’aux intentions de vote en fonction du profil sociodémographique des leaders politiques et des électeur·rices en ancrant fermement l’analyse dans le contexte social et politique canadien. Pour finir, un dernier chapitre présen-tant une analyse quantitative de démocraties occidentales (l’Allemagne (2017), la Nouvelle-Zélande (2017), la France (2017) et les États-Unis (2016)) permet de mettre les conclusions tirées au sujet du Canada en perspective. La seconde partie de cette thèse présente deux expériences, l’une réalisée en laboratoire à l’Université Laval et l’autre en ligne. Basées sur des élections fictives mettant en scène des candidat·es varié·es en termes de genre, d’âge et d’ethnicité, ces expériences s’attardent à la teneur de la relation causale entre l’apparence de candidats et le comportement politique des électeur·rices. La dernière partie de la thèse consiste, quant à elle, en l’analyse de données qualitatives recueillies lors de six groupes de discussion ayant eu lieu entre 2018 et 2019 à l’Université Laval. Trois d’entre eux ont été réalisés avec des personnes ayant participé à l’expérience en laboratoire, et trois autres suites à un appel de volontaires. L’étude de ces discussions met en lumière le mécanisme causal à l’étude en identifiant la teneur des stéréotypes politiques basés sur le genre, l’âge et l’ethnicité au Québec ainsi que la façon dont des stéréotypes sont employés, réprimés, pensés et remis en question par l’électorat. En particulier, cette section de la thèse s’attarde à la possibi-lité d’inférence de valeurs et d’idées politiques en fonction du profil et de l’apparence d’un·e candidat·e.

com-portements politiques pouvant être qualifiés d’affinitaires (liés a l’appui politique de candi-dat·es partageant des caractéristiques sociodémographiques avec des électeur·ices) au Canada et basés sur l’apparence des candidat·es politique. En d’autres mots, les électeurs sont bel et bien au courant des narratifs sociaux entourant la présence de personnes issues de groupes historiquement marginalisés dans l’arène politique, et ils emploient et questionnent les notions préconçues liées à certains groupes sociaux à différents degrés. Bien que les stéréotypes as-sociés à l’"outsider" politique s’avère parfois nettement divergents du profil du politicien dit typique, cette déviation face à la norme politique n’est pas systématiquement sanctionnée. Dépendant du profil de l’électeur, des idéologies qu’il porte et de l’offre politique en place à un moment donné, cette marginalité peut être activement recherchée, car associée à la per-formance de "la politique autrement" ou encore à une meilleure représentation politique d’un groupe social auquel l’électeur peut s’identifier. Un survol de l’état de la question dans d’autres démocraties occidentales soulève cependant la question des règles du jeu politique. Il révèle que ces comportements politiques au Canada en contexte électoral ressemblent davantage aux phénomènes observés lors d’élections présidentielles que lorsqu’il est question d’autres régimes parlementaires s’appuyant quant à eu sur un mode de scrutin proportionnel mixte.

Abstract

This thesis examines the impact of the gender, age, and ethnicity of party leaders in Canada on the way these candidates are received by electors. Social perception is intrinsically relational and puts as much emphasis on the identity of the candidate as the voter. Consequently, this thesis focuses on both the socio-demographic profile of party leaders and the electors who are called upon to evaluate them. In doing so, she contributes to the fields of electoral studies and political psychology.

To do this, three complementary research methods are employed. The first part of the thesis is based on a quantitative analysis of federal electoral data (1988-2015) as well as three Canadian provinces (Quebec (2012-2014), Alberta (2012) and British Columbia (2013)). It looks at the evaluation of party leaders and votes intentions according to the socio-demographic profile of political leaders and voters. The analysis is firmly anchored in the Canadian social and political context. However, a last chapter presenting a quantitative analysis of Western democracies (Germany (2017), New Zealand (2017), France (2017) and the United States (2016)) provides a different perspective on the conclusions drawn in about Canada. The second part of this thesis presents two experiments, one done in a laboratory at Université Laval and the other online. Based on fictitious elections featuring diverse candidates in terms of gender, age and ethnicity, these experiments focus on the content of the causal relationship between the appearance of candidates and voters’ political behaviour. The last part of the thesis consists in the analysis of qualitative data collected during six discussion groups held between 2018 and 2019 at Université Laval. Three of them were done with people who had participated in the lab experiment, and three others after a call for volunteers. The analysis of these discussions highlights the causal mechanism under study by identifying the content of political stereotypes based on gender, age, and ethnicity in Quebec as well as the way stereotypes are used, repressed, thought out, and questioned by the electorate. In particular, this section of the thesis focuses on the possibility of inferring values and political ideas based on the appearance of a candidate.

The main conclusion of this work is the conditional, but very real, occurrence of political be-haviours that can be described as affinity-based (linked to the political support of candidates sharing socio-demographic characteristics with electors) in Canada. In other words, voters

are well aware of the social narratives surrounding the presence of people from historically marginalized groups in the political arena, and they use and question preconceived notions related to these groups to different degrees. Although a particular set of characteristics may be associated with the political "outsider", this deviation from the political norm is not sys-tematically sanctioned. Depending on the profile of voters, the ideologies they carry and the political offer in place at a given moment, this marginality can be actively sought, because associated with the performance of "politics differently" or the better political representation of a social group to which the elector can identify. An overview of the state of affairs in other Western democracies, however, raises the question of the rules of the political game. It reveals that these political behaviours in Canada are more similar to the phenomena observed in pres-idential elections than when we look at other parliamentary systems using mixed proportional voting.

Contents

Résumé ii

Abstract iv

Contents vi

List of Tables x

List of Figures xiii

Acknowledgments xvi

Introduction 1

0.1 Important Promises . . . 3

0.2 Mixed Results . . . 5

1 A Tale of Two Traditions: The Theoretical and Methodological Foun-dations of the Study of Prejudices in Politics 8 1.1 Seeing and Understanding Differences . . . 10

1.1.1 The Perception of Appearance . . . 10

1.1.2 The Evaluation of Appearance . . . 13

1.2 Appearance and Political Behaviour . . . 16

1.2.1 The Influence of Gender . . . 18

1.2.2 The Influence of Age . . . 20

1.2.3 The Influence of Ethnicity . . . 21

1.2.4 The Intersectional Perspective. . . 23

1.3 Methodology . . . 25

1.3.1 The Case for Mixed Methods . . . 25

1.3.2 Research Question, Hypothesis, and Propositions . . . 26

1.3.3 Observational Analysis. . . 28

1.3.4 Experimental Analysis . . . 28

1.3.5 Qualitative Analysis . . . 31

I Observational Analysis: Considering Associations and Statistical

Correlations 33

2 The Face of a Winner: Gender, Age, and the Canadian Federal

Elec-tions (1988-2015) 36

2.1 Understanding the Canadian Context. . . 37

2.2 Expected Voting Behaviours in Canada . . . 38

2.3 Appearance and Political Behaviour in the Canadian Literature . . . 40

2.4 Data and Method. . . 41

2.5 Results. . . 45

2.5.1 Electoral Behaviour . . . 45

2.5.1.1 Logistic Multinomial Regressions . . . 45

2.5.1.2 Predicted Voting Probabilities . . . 49

2.5.2 The Evaluation of Leaders. . . 55

2.6 Discussion . . . 59

3 Digging Deeper: Gender, Age, Race, and Provincial Elections (2012-2014) 62 3.1 Data and Method. . . 63

3.1.1 Québec (2012-2014) . . . 64

3.1.2 Alberta (2012) . . . 65

3.1.3 British Columbia (2013) . . . 65

3.2 Results. . . 66

3.2.1 Electing a First Female Premier. . . 66

3.2.2 Defying Predictions . . . 71

3.2.3 Defining the Left and the Right. . . 74

3.3 Discussion . . . 76

4 Taking a Step Forward: An Exploratory Analysis of Western Democ-racies 80 4.1 Data and Method. . . 81

4.1.1 Germany (2017): Legislative Election. . . 81

4.1.2 New Zealand (2017): Legislative Election . . . 83

4.1.3 France (2017): Presidential Election . . . 85

4.1.4 The United States (2016): Presidential Election . . . 85

4.2 Results. . . 86

4.2.1 When Female Leadership is not a Novelty: The German Case . . . . 86

4.2.2 Unexpected Directions: The Case of New-Zealand . . . 89

4.2.3 Disrupting Old Patterns: The French Case . . . 92

4.2.4 A High-Profile First Female Candidate: The American Case . . . 94

4.3 Discussion . . . 95

II Experimental Analysis: Looking at Causality 97 Introduction 98 5 “It’s a Shame that my Body Probably Reacted”: Considering Diverse Candidacies in a Laboratory Setting 101 5.1 Data and Method. . . 104

5.3 Participants’ Unconscious Reaction to Candidates’ Appearance . . . 111

6 "They Look Canadian and Intelligent": First Impressions and Cana-dian Voters 115 6.1 Experimental Design . . . 116

6.2 Description of the Sample . . . 117

6.3 Electoral Results . . . 118

6.3.1 Support for Diverse Candidates According to Voters’ Profile . . . 119

6.4 Justifying One’s Choices . . . 121

6.5 The Assessment of Candidates’ Traits . . . 128

IIIQualitative Analysis: Investigating Causal Mechanisms and Dy-namics 133 Introduction 134 7 Getting the Picture: Defining Gender-Based, Race-Based, and Age-Based Stereotypes When Discussing Politics 136 7.1 Method . . . 138

7.2 The Awareness of Political Stereotypes’ Content. . . 140

7.2.1 Gender-Based Stereotypes: Their Content and Use . . . 141

7.2.1.1 The Gendered Framing of Politics . . . 141

7.2.1.2 The Portrayal of Women in Politics . . . 142

7.2.2 Race-Based Stereotypes: Their Content and Use . . . 146

7.2.2.1 The Federalism Heuristic . . . 147

7.2.3 Age-Based Stereotypes: Their Content and Use . . . 149

7.3 Intersectionality and Stereotypes’ Interactions . . . 151

7.3.1 The Young and the Pretty. . . 151

7.3.2 Middle-Aged and Older Women: Between the “Nice Aunt” and the “Iron Woman”. . . 153

8 “They’re Not More Competent Because They’re Wearing Three Ties”: Stereotypes Activation and Repression in Political Speech 156 8.1 Inferring Beyond the Observable: Associating Faces With Political Parties and Values . . . 159

8.1.1 The Image of the Liberals . . . 161

8.1.2 The Image of the Parti Québécois . . . 163

8.1.3 The Image of Québec Solidaire . . . 164

8.1.4 The Image of the Coalition Avenir Québec . . . 166

8.2 Stereotypes as a Political Tool. . . 167

8.2.1 Avoiding Appearance: The (Sometimes Unsuccessful) Repression of Stereotypes . . . 168

8.2.2 The Messenger’s Aura . . . 171

8.2.3 Actively Seeking Diversity . . . 172

8.3 Social Distance and the Influence of One’s Social Position . . . 173

A 186

A.1 Recruitment Message: Experiment . . . 186

A.2 Recruitment Message: Focus Groups . . . 186

A.3 Qualitative discussion guide . . . 187

A.4 1988 Election . . . 189 A.5 1993 Election . . . 192 A.6 1997 Election . . . 195 A.7 2000 Election . . . 198 A.8 2004 Election . . . 201 A.9 2006 Election . . . 204 A.10 2008 Election . . . 207 A.11 2011 Election . . . 210 A.12 2015 Election . . . 213

A.13 The Evaluation of Leaders . . . 216

List of Tables

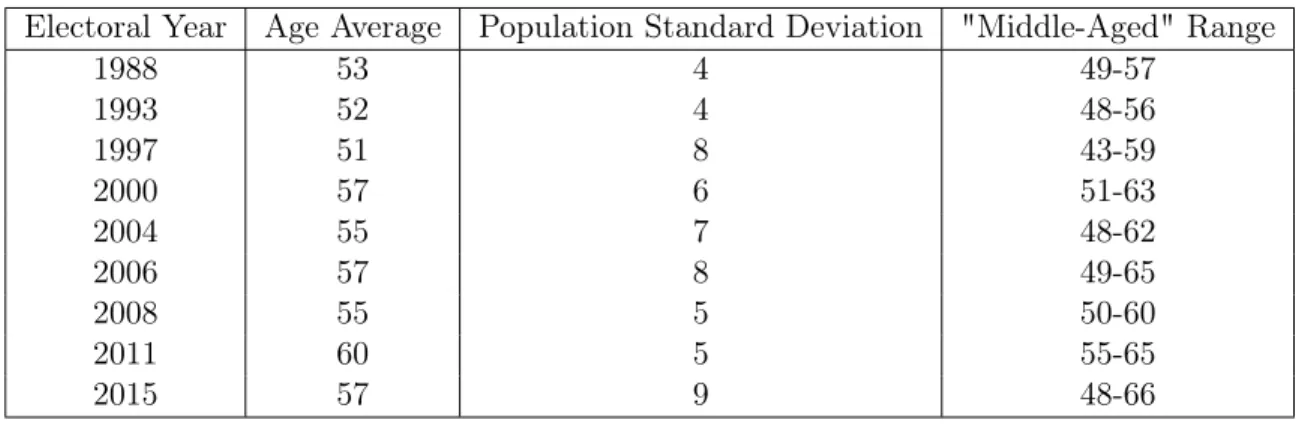

2.1 Party Leaders’ Age (1988-2015) . . . 42

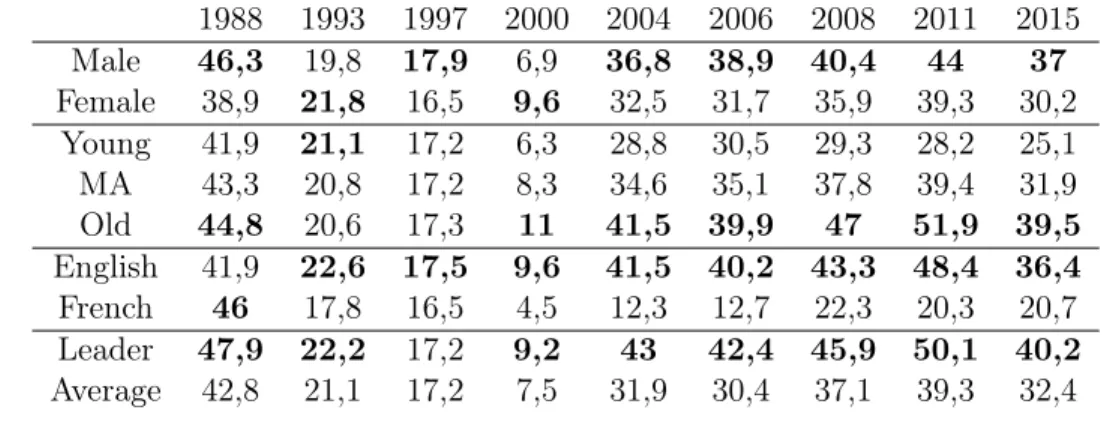

2.2 Party Leaders’ Profile (1988-2015) . . . 43

2.3 Vote Intentions Estimates According to Voters’ Characteristics (Cons & NDP) 46 2.4 Vote Intentions Estimates According to Voters’ Characteristics (Reform/Alliance & Bloc) . . . 47

2.5 Conservative . . . 49

2.6 Liberal. . . 50

2.7 New Democrat . . . 50

2.8 Liberal Voting Probabilities Excluding Quebec . . . 54

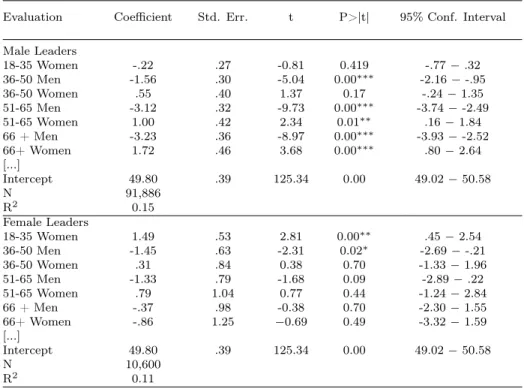

2.9 Male and Female Leaders’ Evaluation According to Voters’ Characteristics (1988-2015) . . . 56

2.10 Leaders of Varying Age’s Evaluation According to Voters’ Characteristics (1988-2015) . . . 57

2.11 Leaders Evaluation According to Shared Gender and Age with Voters . . . 59

3.1 Quebec Party Leaders’ Profile (2012-2014) . . . 64

3.2 Alberta Party Leaders’ Profile (2012). . . 65

3.3 British Columbia Party Leaders’ Profile (2013) . . . 65

3.4 Political Behaviour in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2012) . . . 68

3.5 Political Behaviour in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2014) . . . 69

3.6 Political Behaviour in Alberta According to Voters’ Characteristics (2012) . . . 73

3.7 Political Behaviour in British Columbia According to Voters’ Characteristics (2013) . . . 76

4.1 German Party Leaders’ Profile (2017) . . . 82

4.2 New Zealand Party Leaders’ Profile (2017). . . 84

4.3 French Leaders’ Profile (2017) . . . 85

4.4 American Party Leaders’ Profile (2016) . . . 86

4.5 Political Behaviour in Germany According to Voters’ Characteristics (2017) . . 87

4.6 Political Behaviour in New Zealand According to Voters’ Characteristics (2017) 91 4.7 Political Behaviour in France According to Voters’ Characteristics (2017) . . . 93

4.8 Political Behaviour in the USA According to Voters’ Characteristics (2016) . . 95

5.1 Main Characteristics of the Experimental Sample . . . 104

5.2 Electoral Results . . . 106

5.3 Influence of Voters’ Characteristics on their Support for Specific Candidates . . 109

5.4 Median Vote Time per Election in Seconds . . . 110

5.6 Median Display Time of Minority Candidates . . . 111

6.1 Main characteristics of the sample . . . 118

6.2 Electoral Results . . . 119

6.3 Gender Distribution of Supporters . . . 120

6.4 Average Age of Supporters. . . 121

6.5 Frequency of Qualitative Codes . . . 122

6.6 Traits Evaluation: Election 1 . . . 129

6.7 Traits Evaluation: Election 2 . . . 129

6.8 Traits Evaluation: Election 3 . . . 129

6.9 Average Trait Evaluation of Candidates by the In-Group . . . 130

7.1 Characteristics of the Quoted Participants . . . 140

7.2 Stereotypical Male and Female Politicians . . . 144

7.3 Stereotypical Young and Old Politicians . . . 150

8.1 Stereotypes’ Content: Political Parties in Québec . . . 160

A.1 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (1988) . . . 189

A.2 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (1988) . . . 190

A.3 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (1988) 191 A.4 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (1993) . . . 192

A.5 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (1993) . . . 193

A.6 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (1993) 194 A.7 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (1997) . . . 195

A.8 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (1997) . . . 196

A.9 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (1997) 197 A.10 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (2000) . . . 198

A.11 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2000) . . . 199

A.12 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (2000) 200 A.13 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (2004) . . . 201

A.14 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2004) . . . 202

A.15 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (2004) 203 A.16 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (2006) . . . 204

A.17 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2006) . . . 205

A.18 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (2006) 206 A.19 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (2008) . . . 207

A.20 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2008) . . . 208

A.21 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (2008) 209 A.22 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (2011) . . . 210

A.23 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2011) . . . 211

A.24 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (2011) 212 A.25 Vote Intentions According to Voters’ Characteristics (2015) . . . 213

A.26 Vote Intentions in Quebec According to Voters’ Characteristics (2015) . . . 214

A.27 Vote Intentions in the Rest of Canada According to Voters’ Characteristics (2015) 215 A.28 Male and Female Leaders’ Evaluation According to Voters’ Characteristics (1988-2015) . . . 216

A.29 Leaders of Varying Age’s Evaluation According to Voters’ Characteristics (1988-2015) . . . 217

A.30 Female Leaders of Varying Age’s Evaluation According to Voters’

Characteris-tics (1988-2015) . . . 218

A.31 Leaders Evaluation According to Shared Gender and Age with Voters . . . 219

List of Figures

1.1 Candidates: Election 1 . . . 29

1.2 Candidates: Election 2 . . . 30

1.3 Candidates: Election 3 . . . 30

2.1 Evaluation of Party leaders According to their Gender and Age . . . 44

2.2 . . . 51

2.3 . . . 52

2.4 . . . 53

5.1 Ideological Distribution of the Participants . . . 105

5.2 Results: Election 1 . . . 107

5.3 Results: Election 2 . . . 107

5.4 Results: Election 3 . . . 108

7.1 Middle Aged Sikh Male . . . 148

7.2 Young Asian Male . . . 148

7.3 Young Caucasian Female . . . 152

7.4 Middle Aged Black Female . . . 154

8.1 Middle Aged Caucasian Male . . . 161

8.2 Young Caucasian Male . . . 162

8.3 Middle Aged Black Female . . . 162

8.4 Young Asian Male . . . 163

8.5 Older Caucasian Male . . . 164

8.6 Middle Aged Caucasian Male . . . 165

À Maman (1960-2017)

For outward show is a wonderful perverter of the reason

Remerciements

Je suis extrêmement reconnaissante de toute l’aide apportée par mon directeur et ma co-directrice de recherche, Marc André Bodet et Émilie Biland-Curinier, sans qui cette thèse n’aurait certainement pas été possible. L’improbable rapprochement entre la science politique nord-américaine, les méthodes quantitatives et la sociologie française s’est non seulement avéré possible, mais particulièrement enrichissant à la fois humainement et intellectuellement. Merci à vous deux d’avoir accepté de diriger mes travaux, même lorsque j’ai développé un intérêt très marqué et plus que soudain pour la psychologie politique et que j’ai décidé d’intégrer à ma thèse non pas deux, mais trois méthodes (et que les chapitres prévus se sont multipliés, passant de trois, puis sept... à huit lorsqu’une comparaison internationale s’est greffée à l’ouvrage). Je suis aussi reconnaissante de l’appui inconditionnel dont j’ai bénéficié de la part de ma famille. Bien que personne ne savait exactement ce que je faisais et qu’une certaine confusion subsistait quant à la discipline étudiée ("les relations internationales?"), j’ai bien entendu vos encouragements et ressenti votre fierté. Un grand merci également à Véronique, ma chère amie "de l’extérieur" du monde académique, pour sa présence depuis des années.

Je ne pourrais évidemment pas écrire de remerciements sans mentionner mes ami.es et collègues du département de science politique et de la Chaire de recherche sur la démocratie et les institutions parlementaires. Vous avez été d’une aide précieuse, et ce particulièrement lors de périodes plus difficiles. Que ce soit pour faire face aux embuches de la vie ou au stress des études doctorales, je savais que je pouvais compter sur vous. Merci tout particulièrement à Sabrina, Audrey, Dominic, Marcos, Catherine et Katryne1. Un merci spécial, aussi, à Oscar

et Delonghi.

Je souhaite finalement exprimer toute ma gratitude aux enseignant.es ainsi qu’au personnel administratif exceptionnel du département, sans qui ma vie d’étudiante graduée aurait été franchement moins enrichissante.

La vie est trop courte pour faire de la science ennuyeuse. -A. Brennan

1

Great Expectations: an Introduction

Question:Why did you vote for those candidates?

Answer: To f*** with your dimestore psychological assessment. Who the hell would pick a candidate based on appearances alone. I sure hope you’re not taking this data and trying to make social commentary around it. This is a waste of life. You should be ashamed.

-A participant to the online experiment

Studying appearance in politics is an empirical roller coaster, as no amount of training prepares a researcher for receiving such feedback or spending over an hour discussing with participants who shun the very topic of enquiry. I soon realized that the suggestion that appearance may have an impact in politics can be met with denial, unease or even sometimes with hostility. The fact that a person could perceive candidates differently depending on their sociodemographic characteristics, and that appearance is a relevant variable - although it is definitely not the only one - is commonly deemed either false, morally reprehensible, or both. As a result, most people who participated in discussion groups cautiously avoided that topic at first, although they did open up, in time, and shared their thoughts and impressions. As for the design of the lab experiment, which relied on pictures of politicians without any supporting text, it was sometimes met with disbelief:

Participant 217: I was terrified by the exercise [the lab experiment]. [...] The first four photos, I was like, ”Oh my God, it’s an exercise on the influence of ethnicity.” Participant 46 : Yeah!

Participant 217: It hit me: “oh my God, I’m like that!” [...] It was really impres-sive!

Participant 46: Appearance ends up being important, I won’t deny it.

As Fiske and Taylor (2017) explain, discussing stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination implies an emotional charge, as members of majority groups can quickly become self-concerned regarding their words and actions. After all, social desirability proscribes the expression of stereotypes. They are commonly perceived as systematically erroneous and negative in nature.

We are told that stereotypes are all but the expression of a narrow mind. Why then would anyone resort to stereotypes and consider appearance when evaluating a political candidacy? “We may poke fun at physiognomists, but we are all naïve physiognomists: we form instan-taneous impressions and act on these impressions”(Todorov,2017). These are the words used by a person who co-authored several high-profile studies regarding the predictive nature of first impressions in elections (Todorov et al., 2005; Ballew and Todorov, 2007; Olivola and Todorov, 2010), to describe human’s tendency to infer a vast array of information from a mere look at another individual. Physiognomy, described as the "art of reading personality traits from faces", dates back to ancient Greece but reached the peak of its popularity during the 18th and 19th centuries (Hassin and Trope, 2000). It was then believed, for example, that the incline for criminality was inherited and that criminals could, therefore, be identified through certain physical characteristics. In other words, a criminal necessarily looked like one because they were born as such. While physiognomy is today considered a pseudo-science, its fundamental concepts are still present deep inside us. In truth, as Todorov(2017) insists, first impressions teach us not about the character of the person being observed, but about the mind of the one making the observation.

After all, social interactions among humans rely on perceptions. Being able to quickly guess a person’s intention in a dark alley at night can even turn into a matter of survival. As we have no way of precisely knowing what another person is thinking, the observation of physical cues provides us with an imperfect, but easily accessible proxy (Ward,2016). Faces convey a surprising amount of social information we can use. For example, Todorov et al. (2005) showed that voters favour candidates whom they perceive to be more competent on a picture. Bodies, although far less studied (Ward, 2016), also provide an observer with the possibility to not only acquire information but also to infer traits about another person. Overweight individuals are, for example, perceived as lazy and lonely. In the end, just like in the case of faces, different observers "tend to agree" about which specific traits should be associated with a particular person (Ward,2016).

In politics, stereotypes can have a particular impact. In the Canadian province of Quebec in 2015, for example, the nomination of Gaétan Barrette as head of the Ministry of Health caused a controversy because of his weight. Two years earlier, then Prime Minister Pauline Marois had raised doubts about his capacity to occupy such a position given the fact that he was overweight, even though he is a radiologist and had been the president of Quebec’s federation of medical specialists since 2006. Around the same time, an online petition, raising thousands of signatures, had urged Barrette to adopt “healthy living habits.” 2 Thorough the course of

this research, I met some participants who shared the same impression: I was told that,“as

2

Boisvert Yves. (April 25, 2014) Le poids santé du Dr Barrette. La Presse. http://www.lapresse.ca/debats/chroniques/yves-boisvert/201404/25/01-4760737-le-poids-sante-du-dr-barrette.php (consulted on May 16, 2017).

the Minister of Health, his weight makes him lose a bit of credibility" or that “people focus on comparing his physical appearance to his position" in the government. His appearance, according to an interviewee, made him a “caricature.” Another respondent highlighted the fact that Gaétan Barrette had lost a lot of weight since then, yet “the Fat Barette” image would still stick in voters’ minds. It is intriguing that while individuals may vehemently deny the influence candidates’ appearance could have on them, they may also willingly sign public petitions criticizing a man’s body as unfit to be a minister. It should also be added that Barette’s answer to the criticism was to specifically encourage, on Twitter, overweight voters to support his political party, therefore bringing attention to his body himself.

This tale is not an exception. Years before, the weight and physical fitness of then Prime Minister Paul Martin had also been a topic of discussion - or criticism - in Canadian media (Trimble et al., 2015). It shows that appearance alone can influence one’s perception of politicians, but that taking appearance into account is taboo in itself. Appearance should not matter in a democracy if one’s vote is the product of a rational evaluation of their political interests. According to spatial voting (Downs, 1957), voters are expected to simply evaluate their ideological proximity to a political candidate. However, research on candidate valence has shown that, in reality, other factors come into consideration (Nyhuis,2016). We find that the expectation of rationality leads to the notion of appearance as an illegitimate criterion (Gaxie,

1978). Several focus groups participants have claimed, for example, that those who cared about appearance were not politically sophisticated enough to consider "proper" political issues. This reluctance to discuss appearance, however, does not make this issue simply disappear from the equation. Even though only a small part of the population adopts "extreme blatant stereotypes" (Fiske and Taylor,2017), citizens remain aware of culturally transmitted political stereotypes. Indeed, a great deal of attention is now devoted to political leaders and their image (McAllister et al.,2007;Sampert et al.,2014), and talks about appearance in politics are not only a way to feed the tabloids. Just like any other information provided to the public, appearance-related cues can be used to form judgments about the ones who aspire to or already represent the people in the political arena. The evaluation of politicians is, in the end, part of ordinary citizens’ everyday contact with politics.

0.1

Important Promises

Interest in the impact leaders’ appearance could have on voters is prompted in part by an important scholarly tradition in social psychology. All human interactions are based on a triad of concepts: cognition (thoughts), affect (feelings), and behaviour. First comes cognition, the “mental activity of processing information and using that information in judgment” (Stangor,

social categories that allow instantaneous classification (Allport,1954). A person is then given the opportunity to quickly guess –more or less accurately– others’ interests or personality through the use of stereotypes – the mental images used to define social groups (Bodenhausen et al., 2012). It is for that reason that appearance matters in politics for many researchers. Some, such as Carpinella et al. (2016), claim that “facial cues are consequential for voters’ behaviour at the polls.” It is even argued that a candidate’s electoral success can be predicted by their appearance (Olivola and Todorov,2010). While these claims are bold, work in both political science and social psychology provide theoretical foundations for the study of physical cues.

In order to compensate for a lack of knowledge, citizens can take into account the appearance of politicians. Accurate or not, the importance of stereotypes pertaining to the evaluative judgment of others is great: they influence impressions, knowledge, and memories associated with a person (Freeman and Ambady,2009). However, all stereotypes do not carry the same weight or any weight at all. As Bauer (2015) explains, there is no direct link between the existence of stereotypes in a person’s mind and the perception of others. Therefore, in poli-tics, voters do not always rely on stereotypes to form a final opinion about candidates. The reliance on stereotypes depends on the extent of their activation (how accessible stereotypes are in one’s mind) and how applicable they are to a situation (Kunda and Spencer, 2003;

Bauer,2015).

Voters’ lack of information has often been blamed for the intrusion of appearance in politics. Empirical research shows that voters rarely possess enough knowledge about candidates and parties to make a decision compatible with the standards of normative democratic theory (Banducci et al.,2008). Since The American Voter (Campbell et al.,1960), the literature on day-to-day politics has underlined the gap between what voters should know to “properly” evaluate candidates and reality (Déloye,2007). Campbell et al.(1960) and the Michigan Vot-ing Behaviour School showed that voters have little interest in their political role. Citizens’ “formal” political competence, which can be more or less limited, rests on information accumu-lated through socialization (Joignant,2007). Analyzing a candidacy is a complicated process involving multiple dimensions of political and social life. Overall, according toDéloye (2007), only a minority of voters possess the cognitive and political tools to do so. In other words, as Bourdieu (1973) argues, political competence is not always within citizens’ reach. When the information voters possess is unfit or insufficient to make sense of political situations - or to save time and energy -, they can rely on other general or practical knowledge completely unrelated to politics (Joignant, 2007). These shortcuts, known as cognitive heuristics, are used “as a bridge between the realities of a grossly uninformed electorate and the demands of normative democratic theory” (Banducci et al.,2008).

that empirical research points toward a particularly heightened relevance of physical cues in low-information contexts (Banducci et al.,2008;Lenz and Chappell,2011;Matson and Fine,

2006; McDermott, 1997, 1998). Nevertheless, social categorization is an automatic mental process (Allport,1954;Bodenhausen et al.,2012;Dovidio et al.,2005;Freeman and Johnson,

2016), which means that even though the use of such heuristics is encouraged by ignorance, voters with little political knowledge are not necessarily the only ones who might take physical cues into account. Studies have shown, for example, that individuals with “negative racial affects and attitudes” (Murakami, 2014) are less likely to vote for a candidate associated with a minority (see also Street (2014)), regardless of their mastery of political information. Moreover, according to Bauer(2015), citizens are more likely to rely on stereotypes if specific issues related to them become salient during the campaign. As a result, citizens’ contact with the political world is guided in part by emotions (Erikson et al., 2002) or by aesthetic cues that are used to classify individuals and to locate oneself in comparison to them (Joignant,

2007). In other words, the evaluation of candidates is a relational process as voters situate the candidate in relation to themselves (Sigelman and Sigelman,1982).

0.2

Mixed Results

In spite of these strong theoretical expectations, empirical evidence remains mitigated. Ac-cording to McGraw (2011), the link between the perception of candidates, their evaluation and the final act of voting has been the topic of a “long and distinguished history of scholarly studies.” A rapidly growing body of literature analyzes the specific effect of candidates’ ap-pearance on voters’ behaviour. However, the results emanating from these studies are highly mixed. As Bird et al.(2016) state, findings are, in fact, contingent upon the methodology at use. Observational studies suggest little or no influence of the candidate’s identity on voters’ choice. Back in 2010, Bartels (2010) noticed what he called a “failure” of causal modelling when observational data is used. For example, little evidence of voting affinity was found, in Canada, at the federal level (Goodyear-Grant and Croskill,2011;Landa et al.,1995). However, still in the Canadian context, experimental studies involving the manipulation of fictional can-didates’ characteristics revealed a mixed effect of race and gender on voting behaviour (Besco,

2015; Tolley and Goodyear-Grant, 2014).3 Moreover, the Quebec population has frequently

been omitted from the samples studied (Murakami,2014;Tolley and Goodyear-Grant,2014). Even when an effect is perceived, its direction remains a topic of debate. For example, au-thors like Adams (1975) and Brouard and Tiberj (2011) report that minority candidates can receive a boost in electoral support while others, like Petrow(2010), find the opposite. As for the influence of age, it is rarely considered. One notable exception is Sigelman and Sigelman

(1982) who investigated the influence of sexism, racism, and ageism on electoral behaviour in

3

an experimental setting (fictional mayoral elections) with surprising results. In fact, according to them, age was the strongest influencer of all. Given the reported influence of age, its relative absence from the literature remains puzzling.

Several hypotheses could explain these mixed results. First, as McGraw(2011) notices, there is a tendency in the literature to assume that judging and voting for a candidate rely on the same underlying processes. According to behavioural decision theory, this is wrong. The eval-uation of a candidate indicates whether they are personally liked or disliked and is commonly measured using a scale. Meanwhile, when citizens vote, they are asked to choose a person out of a pool of candidates. Evaluation and vote are not equivalent. One may very well influence the other, or may not. As portrayed by the Michigan School of Voting Behaviour’s funnel of causality, candidate evaluations are one out of many factors influencing voters’ final choice, along with partisan affiliation and issue positions for example (Campbell et al.,1960). Other factors could have greater impacts than candidates’ sociodemographic characteristics, mitigat-ing or cancellmitigat-ing its effect. As a result, in certain circumstances, candidates’ sociodemographic characteristics could not matter much to voters. For example, in Canada, according to Blais et al. (2003), partisan affiliation and party leaders carry greater weight than the identity of local candidates. In fact, several others claim that partisanship has the greatest influence on vote choice (Alvarez and Nagler,1995;Campbell et al.,1960;Miller and Shanks,1996; Weis-berg, 2008). This hypothesis was tested in Germany by Kam (2007) who found that party cue is a “limiting condition on the effect of group attitudes.” According to Street (2014) and

Murakami (2014), sociodemographic cues could nonetheless affect a limited group of voters, but aggregation would then lead to its dissipation. Lastly, for Bird et al. (2016), the influ-ence of ethnic or gender affinity voting during an actual campaign could also depend on the occurrence of incidents or events adding salience to these identities. Gender and race would then carry greater weight and influence voting behaviour (Plutzer and Zipp,1996). Similarly,

Bauer (2015) encourages the study of the events surrounding the campaign by highlighting the importance of stereotype activation.

In brief, a general overview of the existing literature highlights several issues. First, for

Campbell and Cowley(2014), “the literature on candidate effects is large, but it is also partial and geographically skewed,” with a majority of work focused on the “biological sex and race” of candidates and restricted to the United States. As for the studies that specifically focus on the Canadian case, some exclude Quebec voters. Additionally, as Cutler (2002) claims, most studies focus on the influence of a single or a few perceived cues on voters’ opinions without much comparison. Few studies have adopted an intersectional posture to understand the influence of candidates’ identity (see Bird et al. (2016)), which is problematic, given the fact that the interaction of different sources of stereotypes is a complex phenomenon. Intersectional authors like Philpot and Walton (2007) argue for the necessity to examine

multiple cues simultaneously to take their “mutually reinforcing relationship” into account. It could be hypothesized that the effects of appearance may be stronger when a single individual is associated with multiple marginalized groups at once and that certain characteristics could "cancel" the impact of another.

This dissertation departs from a focus on voting behaviour to consider the overall evaluation of political candidates or, in other words, voters’ reaction to politicians, since even if appearance had little or no impact on the vote, politicians may still be routinely judged based in part on their physical characteristics. The question asked looks at the influence of gender-based, age-based, and ethnicity-based stereotypes on the political behaviour of voters toward party leaders in Canada. To answer it fully, as social cognition is inherently a relational process between an observer and a person who is observed, the sociodemographic profile of voters must also be taken under consideration. In other words, voters do not share a single, unified, point of view on candidacies. Just like politicians, voters are socially situated and this position could affect the way they make sense of the political game, as shown by the research tradition centred on the effects of voters’ sociodemographic characteristics in political science, starting with the Columbia (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944) and Michigan (Campbell et al., 1960) models of vote choice.

Chapter 1

A Tale of Two Traditions: The

Theoretical and Methodological

Foundations of the Study of

Prejudices in Politics

"Candidates for political office are more than just walking and talking policy profiles." -Nyhuis (2016)

"First impressions really do count. People judge each other within a fraction of a second, for better or worse. Luckily, under some circumstances people are capable of going beyond those split-second impressions. The relatively automatic first impression nevertheless anchor subsequent thinking, so they are difficult to undo."

-Fiske and Taylor(2017)

The literature in social psychology claims that first impressions based on one’s appearance have long-term effects. Among the many types of physical cues that may be considered, this dissertation focuses on race-based, age-based, and gender-based prejudices, as they are the first three types of cues detected upon encountering an individual. Put otherwise, a new face is first categorized based on these three categories, which are referred to as “basic” or “prim-itive” in social psychology (Jackson,2011). More importantly, these specific cues have social meaning. Among sociodemographic characteristics, race and gender are particularly visible and “politically salient” (Tolley and Goodyear-Grant,2014). It is therefore not surprising that the influence of gender-based and race-based prejudices on voting behaviour is already an important topic of research in Western literature. As for age, even though it has often been neglected in political science, it has nonetheless been shown to mainly influence the appearance of competence (Bowen and Skirbekk, 2013; Fiske et al., 2007; Kite et al., 2005; Löckenhoff

et al.,2009). Understanding the influence of politicians’ appearance on the evaluation citizens make of them might bring us one step closer to solving the complex and persistent puzzle of several social groups’ under-representation in democracies. Still, nowadays, a minority of elected officials are women in Canada (Thomas and Bodet, 2013) as well as in nearly every other parliament of the world (Goodyear-Grant,2013). The presence of immigrants and ethnic minority politicians in parliaments also remains marginal despite the increasing diversity of populations in advanced democracies (Black, 2000b, 2002; Murakami, 2014). Age is not as politically salient, but middle-aged individuals remain numerous in parliaments nonetheless (Paquin,2010). We have yet to determine if being too young or too old could be an obstacle in politics (Armstrong and Graefe, 2011). The electorate’s prejudices are suspected of play-ing a role in this stalled progress among other factors such as the electoral system and the political parties’ candidate selection process (Young, 2006). Regardless of its causes, politi-cal under-representation is not without consequences. Research shows, for example, that the presence of women and ethnic minority politicians facilitates the adoption of laws favourable to citizens sharing the same sociodemographic characteristics (Swers, 2001; Thomas, 1991;

Tremblay and Pelletier,2000). As a consequence, asBird et al.(2016) claim, it is particularly important to understand if citizens’ biases are partly to blame for under-representation. The study of appearance’s influence on voters can also help us to understand the effects of political communication strategies aimed at putting forward or dissimulate certain characteristics of a candidate. From Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s extensive use of “selfies” to Hillary Clinton publishing her health record, certain aspects of politicians’ lives are deliberately shown to the public to construct or reconstruct their image which, in itself, carries meaning (Parry-Giles,

2000). To preserve one’s image, just like cues may be exacerbated, others can be hidden. For example, French President François Mitterand had reports falsified to hide from a public an illness (cancer) which was long treated as a state secret.

This thesis is rooted in a political approach of a theoretical framework developed in social psychology relative to the place of prejudices and stereotypes in the formation of opinions and behaviors. In particular, we rely on the work ofFiske et al.(2002) regarding the heterogeneity of stereotypes associated with different marginalized social groups. This work, of course, can be used in conjunction with an intersectional approach, which highlights the differences between the social positioning of individuals at the crossroads of different sources of oppression. This was originally raised by KimberléCrenshaw(1989) when she criticized the treatment of gender and ethnicity as isolated.

This research will contribute to the literature in several ways. First, we adopt a mixed-method research design to thoroughly investigate the causal mechanism at play. Many studies have been done on the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on voting behaviour with mixed conclusions. More precisely, different methodologies tend to produce different results, with neg-ative observational findings often contradicting positive experimental ones (Bird et al.,2016).

These negative results are even more puzzling given the strength of the theoretical foundations behind the influence of appearance and stereotypes on political behaviour, as well as proofs of the widespread use of heuristics by voters (Gigerenzer and Brighton,2009;Gigerenzer and Todd,1999;Lupia,1994). Moreover, few studies pay attention to the causal mechanism under inquiry, even though the literature documents irregularities both across cases and between research methods used. To contribute to solving this puzzle and understand the disparities between experimental and observational results, this mixed-method design allows a deeper understanding of causal pathways. According to Seawright (2016): “Multi-method designs combining qualitative and experimental methods are unusually strong. . . While evidence re-garding causal pathways between the treatment and the outcome is not required to make a causal inference using an experiment, it can vastly increase the social scientific value of exper-imental results, and qualitative research can contribute substantially to this objective.” Second, even though the age of politicians is often discussed in the media, the study of age-based prejudices in politics remains extremely marginal in the literature (Piliavin,1987; Sigel-man and SigelSigel-man, 1982). Race-based and gender-based prejudices have been analyzed far more frequently. Different cues are also most often studied separately, which also raises im-portant issues given the effects of different identities’ interaction in politics (Smooth, 2006). The study of dynamics between multiple sources of prejudice in different contexts is another important contribution this dissertation seeks to make. Contradictions uncovered by the lit-erature on the influence of candidates’ appearance on political behaviour could be explained by the choice of variables or the way they were analyzed.

1.1

Seeing and Understanding Differences

1.1.1 The Perception of Appearance

Work in both political science (Banducci et al.,2008) and social psychology (see, for example,

Olivola and Todorov (2010)) provide theoretical foundations for the study of the effects of leaders’ physical cues in politics. Any person, politically sophisticated or not, rely on cate-gorization based on appearance to make sense of the social world. This cognitive process is also used in politics just like in any social activity (McGraw,2011). Perception is particularly swift: it takes the blink of an eye to associate somebody else with social labels. This cognitive process known as categorization is “automatic” and “unavoidable” (Allport,1954). However, the observer can go beyond those initial thoughts and engage in the deliberate mode of so-cial cognition. First impressions will, nevertheless, influence subsequent thinking (Fiske and Taylor,2017). Put otherwise, first impressions may not guide behaviour in the end, but they remain at the root of opinion formation (Allport, 1954; Bodenhausen et al., 2012; Dovidio et al.,2005;Freeman and Johnson,2016).

More precisely, human interactions are based on a triad or processes: cognition or thoughts; affect or feelings; and behaviour. Cognition involves the mental processing of information related to a person’s appearance (Stangor,2011) and implies the brain matching one’s physical features to different social categories or "labels" (Allport, 1954). Each one of these labels is associated with expected content, or, in other words, a stereotypical image (Bodenhausen et al., 2012). The word “stereotype” is commonly charged with a negative connotation but, in social psychology, it is not intrinsically pejorative. Stereotypes simply stand for the mental representation of a given social group. All in all, categorization leads to the activation of “beliefs” related to the social category the newcomer has been associated with (Hugenberg and Sacco,2008). In other words, one may use the knowledge they have accumulated about a given social category (“category-based knowledge” (Kawakami et al., 2017)) to formulate expectations regarding another person, how they are like and what they may do. Put simply, that social knowledge is composed of both schemas – “knowledge representation that includes information about a person or a group”–, and attitudes – “knowledge representation that includes primarily our liking or disliking for a person, thing or group” (Stangor,2011). Social cognition is interactive and relational. Schemas and attitudes are socially constructed, as they are influenced by the common narrative regarding specific social groups. As such, these narratives are expected to be specific to a time and a location. Nonetheless, schemas and attitudes are not entirely determined by one’s environment. As personal values and beliefs also come into the equation (Stangor,2011), different people do not necessarily react identically when encountering the same person. That difference in reaction is also rooted in people’s self-schemas or self-identification. A self-schema is formed by the combination of “two bodies of knowledge: information about the stimuli in some domain and knowledge of one’s self.” All in all, it is created when one person identifies with a group (Conover, 1984): “[. . . ] In the process of consciously classifying oneself as a member of a group, the individual takes the very first step toward blending together the mental representation of the self with the cognitive stereotype of some group. Subsequently, as identification with the group increases, the nascent self-schema should become more developed and its importance heightened.” Individuals are more likely to identify with a group if the attribute that defines that group is salient or distinctive (an attribute “by which people are distinguished”) (Conover,1984). In brief, a person has to perceive oneself as part of the group first before identifying to it and, eventually, feeling attachment toward it and developing “group consciousness” (Conover,1984). Self-schemas are long-lasting (Bartlett, 1932) and act as a filter through which new infor-mation related to oneself or others passes (Conover, 1984). Thus, group identification is a very important aspect of the evaluation of other people’s appearance. Individuals classified as members of the same social group as the observer are called “in-group” members. Those associated with different social categories are labelled “out-group” members. In brief, the

categorization of oneself influences one’s perception of reality. As Bodenhausen et al.(2012) explain: “when we place an individual into a social category, we are likely to consider our own status with respect to that category.” Individuals also put emphasis on the distance between different social groups while assuming proximity among out-group members (Hugenberg and Sacco, 2008; Linville and Jones,1980;Linville et al.,1986). Consequently, social categoriza-tion encourages the use of broad generalizacategoriza-tions to qualify members of the same social group (Klauer and Wegener, 1998) and the temptation is even stronger with members of an out-group as they are perceived as more similar to one another. It seems, therefore, that research that focuses on the political candidates being judged and neglects those doing the judging is missing an important piece of the equation as self-identification with specific social groups influences one’s evaluation of other people.

Categorization is essential, as it allows the swiftness of judgment necessary to navigate one’s social environment (Macrae et al.,1994). Individuals use these schemas to form expectations about their surroundings (Eysenck and Keane,2010). As Bodenhausen et al. (2012) explain: “Categorization is fundamental to human cognition because it serves a basic epistemic function: organizing and structuring our knowledge about the world. By identifying classes of stimuli that share important properties, categorization allows perceivers to bring order and coherence to the vast array of people, objects, and events that are encountered in daily life. . . Once a categorical structure is superimposed upon them, the immense diversity of individual entities becomes manageable.” Social categorization is particularly useful considering the large size and complexity of modern human societies (Dunbar, 1988; Petersen, 2012; Petersen and Aarøe,

2013). As a result, humans have to rely heavily on their imagination to determine what fellow citizens could be like (Petersen and Aarøe, 2013). In other words, just as Anderson (2006) puts it, human nations truly are imagined communities.

Stereotypes are defined by Lippman (1922) as mental images of social groups. They are “cognitive structures that shape thoughts, feelings, and action” (Dovidio et al., 2005) and a way for the brain to “simplify a bewildering amount of social information” (Freeman and Ambady,2009). As already mentioned, they are not always negative but they do rely on broad generalizations. All in all, they are the unavoidable result of humans’ way of thinking (Dovidio et al., 2005). Stereotypes are learned and are therefore strongly influenced by one’s social environment. They form as early as childhood and have numerous sources, including cultural norms and values (Dovidio et al.,2005), parental and peers influence, as well as media exposure (Aboud and Doyle,1996;Brown,1995). Culture influences stereotypes through a common set of beliefs and expectations that remain, for the most part, unnoticed by the society that carries them. Nonetheless, both culture and ideology can act as a justifying mechanism of prejudice and social exclusion (Dovidio et al.,2005) or privilege. While group privileges provide certain individuals with an “unearned favoured state conferred simply because of one’s race, gender, social class, or sexual orientation” (Whitley and Kite, 2010), others can be undeservedly

treated in a negative manner owing to some of their sociodemographic characteristics (Whitley and Kite,2010).

According to the classic work of Allport(1954), a founding figure in the field (Dovidio et al.,

2005), prejudices (and stereotypes) result from overgeneralized and erroneous beliefs. That definition has, however, been nuanced by modern psychology (Whitley and Kite, 2010). It is not impossible that some stereotypes may reflect genuine perceived differences between the social situations social groups normally face (Bodenhausen et al.,2012). Nevertheless, stereo-types, positive or negative, remain the result of overgeneralization (Whitley and Kite,2010). In addition, stereotypes can act as self-fulfilling prophecies (Bodenhausen et al.,2012). Those who are tempted to defy stereotypes may, for example, be subjected to a backlash and discour-aged from adopting counter-behaviours. As for the inaccuracy of stereotypes, it can also stem from insufficient exposure to a group or strong prior expectations. These expectations can be rigid to the point of turning, to the eyes of the observer, “. . . non-stereotypic information into stereotype-congruent representations” of the target group (Bodenhausen et al.,2012). Lastly, stereotypes can fully part with reality when individuals actively seek “satisfying” conclusions (such as “ego-gratifying” or “system-justifying” stereotypes). For example, “. . . the strong desire we hold for feeling that the world is fair and just may lead us to form negative stereo-types that can provide a seeming justification for a group’s low social status” (Bodenhausen et al., 2012), such as the belief in the inherent laziness of individuals perceived as having a low income or as being homeless.

Nevertheless, awareness of a given stereotype does not guarantee that a person will simply accept it. Therefore, in politics, voters do not always rely on stereotypes to form an opinion about candidates (Bauer,2015; Kunda and Spencer,2003). Voters are faced with the choice of either processing information quickly by relying on goal-driven trait inference or devoting intentional thoughts to evaluate these candidacies and overcome habitual stereotypes (Fiske and Taylor,2017;Whitley and Kite,2010).

1.1.2 The Evaluation of Appearance

Put simply, the evaluation of a candidacy ultimately refers to the notion of liking or disliking an individual. It is at this step of the process that prejudices intervene. Prejudices are attitudes, which are defined by Dovidio et al. (2013) as composed of a "cognitive component (e.g., beliefs about a target group), an affective component (e.g., dislike), and a conative component (e.g., a behavioural predisposition to behave negatively toward the target group).” Given the complex nature of prejudices and emotions, a person can very well value tolerance and equality, and yet feel uneasy around individuals associated with an out-group: for example, according to Dovidio et al. (2005), members of socially advantaged groups may entertain feelings justifying social hierarchy while openly endorsing egalitarian values. A person can

even experience certain emotions when exposed to another person and yet, remain unaware of these emotions’ existence. In that case, prejudices are said to be implicit. Nonetheless, emotions, even subtle ones, have consequences. They influence behaviour in diverse ways. Negative emotions can motivate an attempt to avoid certain people just as they can encourage someone to treat an out-group member with special care out of shame or denial (Jackson,

2011). Prejudices can also be controlled to comply with social expectations or norms (Terbeck,

2016). Hostility toward a group could be tuned down to adopt, at least on the surface, a socially desirable attitude. To do so, however, an individual must be explicitly aware of their use of stereotypes and the nature of their feelings toward an individual. Chapter 8 shows that this awareness is not guaranteed. According to Jackson (2011): “Because many people are often oblivious to their own biases, it is quite likely that implicit cognitive and affective processes, and their neurological underpinnings, are part of the problem of the perpetuation of prejudice, discrimination, and inequality.”

The classical portrayal of emotions emphasizes their automaticity. In this perspective, every emotion is expected to follow a pre-established pattern and are activated like the “flip of a switch” (Barrett, 2017a). More importantly, emotions are frequently described as universal: a person feeling happiness is expected to portray it in a pre-determined manner which can then be identified as such by everybody else, regardless of their own culture and upbringing. Important doubts have since then been cast on this perspective. Supporting the theory of constructed emotion,Barrett(2017b) explains: “. . . we find that your emotions are not built-in but made from more basic parts. They are not universal but vary from culture to culture. They are not triggered; you create them. They emerge as a combination of the physical properties of your body, a flexible brain that wires itself to whatever environment it develops in, and your culture and upbringing, which provide that environment.” The experience and performance of emotions are social constructs: both the facial expression of emotions and the physiological response that accompany them display variation “within the same individual and across different individuals” depending on the context (Barrett, 2017b). The emotions involved in prejudice are often unconscious; they can very well be conflicting or ambivalent. Additionally, individuals do not differentiate and identify their emotions in a uniform and pre-established manner. Many emotions, such as fear or anxiety, are hardly distinguishable and frequently “bundled” together (Barrett, 2017b). In fact, positive and negative emotions that contradict each other can often cohabit during an encounter (Whitley and Kite,2010). In the end, the way emotions will be interpreted by the brain depends on the context sur-rounding their emergence. Emotions can be understood as a construction rather than prepro-grammed reactions (Barrett,2017b). As emotions can be attributed to a cause retrospectively, they can actively contribute to the formation of prejudices. According toAhmed(2014), public discourse can aim at “aligning subjects with collectives by attributing ‘others’ as the ‘source’ of our feelings,” blaming, for example, immigrants for a feeling of economic insecurity or anxiety.

The fact that prejudices influence and are influenced by one’s social environment is ultimately unsurprising. According to the cultural constructionist perspective, both emotions and cog-nition are deeply embedded in culture and built on social performances. Prejudices, just like stereotypes, can vary from one person to another, from one place to another and also change through time. For example, a contemporary form of racism, known as “modern racism,” is characterized by the avoidance of an out-group as well as disregard or denial of the impor-tance of racial issues. While blatant racist demonstrations are most often considered morally condemnable, “modern racism” is rooted in race-based stereotypes and can subsist undetected (Tolley,2016).

Where do prejudices come from? Just as stereotypes, they have multiple causes. Socialization is a continuous, life-long process, through family, friends, work, and the media (Jackson,

2011). For example, Allport (1954) underlined the importance of parental attitudes in the formation of their offspring’s prejudices. The media also contributes to framing the public discourse, including the social narrative surrounding marginalized groups (Ogan et al.,2014), by portraying them negatively or positively (Paluck,2007). The construction of prejudices is also influenced by the group-based hierarchies promoted by different societies. More precisely, according to Guimond et al.(2003), wide human groups develop an age system of hierarchy as well as a gender system and an “arbitrary-set system,” “hierarchies of socially constructed groups based on any socially relevant group distinctions such as ethnicity, social class, or religion.” The reproduction of social hierarchies, notably through education, contributes to their normalization and, ultimately, to their legitimization (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1970). Bourdieu refers to the effects of socialization as the habitus. It includes ways of thinking, acting, feeling, and understanding the world that are learned through contact with one’s social environment. Put otherwise, the habitus is a socially generated structure used to make sense of and take part in society (Bourdieu,1981). All in all, the human brain expects the outside world to fit a narrative that has been forged through past experience and thus follows familiar structures (Barrett,2017b). For that reason, one’s social environment is a strong influencer of social expectations. Nevertheless, that narrative remains a personalized construction: humans build their own vision of the world and do not simply accept, time after time and without question, every piece of information that is conveyed by their surroundings. They may, as a result, avoid altogether new information that contradicts an established narrative ( Harmon-Jones and Mills, 1999). As a result, some prejudiced messages may appear more or less appealing to a person depending on contextual as well as personal factors. For example,Ogan et al. (2014) found that deeply held political ideology is correlated with the opinion towards Muslims in the United States. As a result, certain individuals may be more receptive than others to the negative portrayal of a group.

Emotions in politics have long been brushed aside, considered irrational and foreign – if not detrimental – to reason (Marcus et al., 2000). It even took a while for scholars to consider

them as a topic of inquiry (Braud,1996). However, the role of emotions in the development of political behaviour has been recognized since then: emotions motivate or impair action and are part of every human interaction, including among voters, politicians, and between those two groups. They influence citizens’ preferences, and they ultimately contribute to shaping public opinion (Marcus et al.,2000). In politics, the emotions of voters can even be voluntarily encouraged by political figures as part of a communication strategy (Jasper,2011). According to Loic and Christophe (2018), politics is often orchestrated to stimulate particular emotions (like enthusiasm toward a candidacy) and temper others, such as discontent that leads to violent means of protestation. In the end, emotions are an important part of mobilization, and a factor of commitment and cohesion (Duperré,2008;Christophe,2009)

Lastly, prejudices’ impact is not limited to the person doing the judging. Individuals subjected to negative prejudice are not oblivious to these emotional responses. They can formulate pre-cise expectations – called metastereotypes – about the way others perceive them. In fact, prejudices can have a self-fulfilling nature: a person subjected to systematic and repeated prejudice may behave in a particular way in anticipation and may even believe, in the end, that those stereotypes hold some truth. Exposure to prejudices can also encourage the oppo-site reaction: individuals may try to prove stereotypes wrong, or seek to avoid contact with out-group members out of fear of being stereotyped. Avoidance can also come from mem-bers of privileged social groups if they feel they are themselves stereotyped as prejudiced by marginalized out-group members (Jackson,2011).

1.2

Appearance and Political Behaviour

Programs and ideologies are not the only things that matter in politics. Research shows that voters also pay attention to "non-policy factors" (Nyhuis,2016), ranging from campaign issues (including incumbency status) to the personal characteristics of politicians (Stone and Simas,

2010). Even when voters claim that they know little about party leaders, they will nonetheless have feelings about them (Blais et al.,2000).

The literature on social categorization has been used to better understand the influence of appearance on the relationship between voters and candidates. Two effects of hasty judg-ment on voting behaviour or candidate support are judg-mentioned. First, choice homophily is defined as the tendency for human beings to favour and choose other individuals with similar sociodemographic characteristics (in-group members) over others (Murakami, 2014). Some researchers argue that, ceteris paribus, voters tend to favour candidates who share similar so-ciodemographic characteristics (Cutler, 2002), including gender (O’Neill,1998;Brians,2000;

Huddy and Terkildsen,1993b;Plutzer and Zipp,1996), race (Sigelman et al.,1995; Terkild-sen,1993;Greenwald et al.,2009), and age (Piliavin,1987;Webster and Pierce,2015). Others

add that in-group favoritism and other appearance-based heuristics are mostly present within low-information contexts (McDermott,1997,1998;Oliver,2010;Ahler et al.,2017).

Choice homophily is defined as the tendency for human beings to favour and choose others with similar sociodemographic characteristics (Murakami,2014). In politics, choice homophily can manifest itself as affinity-voting, which occurs when a candidate is categorized as an in-group member. Electoral choice is then based on the fact that both voters and candidates share sociodemographic characteristics (Bird et al.,2016;Tolley and Goodyear-Grant,2014). Examples of such behaviour are shown throughout this dissertation. Two types of arguments are raised to explain the occurrence of affinity-voting according toBesco(2015).

Affinity-voting relies on shared identity (Murakami,2014). As we have mentioned previously, humans tend to categorize others between what is called in-group or out-group members. That process has been recognized as a source of bias (Dovidio et al.,2005). It has even been argued that humans are, in fact, conditioned by evolution to favour the in-group over out-group members (Hogg and Abrams, 1988; Murakami, 2014; Tajfel, 1981; Tajfel et al., 1979). The positive evaluation of in-group members could be linked to one’s self-esteem: a person may feel valued when an in-group member wins an election (Besco,2015). All in all, this theory focuses on in-group favoritism instead of out-group discrimination, as individuals choose to favour a person "like them" rather than penalize someone else (Bird et al.,2016;McClain et al.,2009;

Plutzer and Zipp,1996;Tajfel,1981). Affinity-voting could result from the heuristic of “linked fate,” defined as “a perception that [one’s] own individual life chances are inexorably bound with what happens to [the in-group] as a whole” (Oliver,2010). According toDawson (1994), that feeling is shared notably by African-Americans, as they belong to a negatively ascribed social group. As mentioned before, members of ostracized groups are often perceived as a collective of similar people instead of as individuals. As a result, certain groups would tend to see their fate as intertwined with the fate of their peers (Bird et al., 2016; Oliver, 2010). Affinity-voting could also be motivated by an interest-based heuristic (Besco, 2015), if the candidate is perceived as representing their in-group’s interests. Voting for that candidate could then “improve [the group’s] status” (Bird et al.,2016).

Marginalized candidates could also suffer from a political penalty (Bird et al.,2016) if they are confronted with negative stereotypes which then “become filters through which informa-tion consonant with the stereotype is perceived and assimilated while contrary informainforma-tion is ignored or discounted” (Fisher et al., 2013). Overall, negative stereotypes could target po-litical outsiders - through the language they speak, the colour of their skin, or their cultural norms (Kinder and Sears,1981) and twist one’s perception of a candidates’ "issue positions or ideological orientations" (Koch, 2000). However, stereotypes do not have the same influence on every voter. As Murakami (2014) states, some who hold higher levels of negative preju-dice may be more likely to follow these first impressions and avoid supporting an out-group candidate.