O

pen

A

rchive

T

OULOUSE

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and

makes it freely available over the web where possible.

This is an author-deposited version published in :

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID : 11070

To link to this article : DOI : 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2011.03.027

URL : http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2011.03.027

To cite this version :

Herteman, Mélanie and Fromard, François and

Lambs, Luc Effects of pretreated domestic wastewater supplies on

leaf pigment content, photosynthesis rate and growth of mangrove

trees: A field study from Mayotte Island, SW Indian Ocean. (2011)

Ecological Engineering, vol. 37 (n° 9). pp. 1283-1291. ISSN

0925-8574

Any correspondance concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator: staff-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

Effects

of

pretreated

domestic

wastewater

supplies

on

leaf

pigment

content,

photosynthesis

rate

and

growth

of

mangrove

trees:

A

field

study

from

Mayotte

Island,

SW

Indian

Ocean

Mélanie

Herteman

a,b,

Franc¸

ois

Fromard

a,b,∗,

Luc

Lambs

a,baUniversitédeToulouse,INP,UPS,EcoLab(LaboratoireEcologieFonctionnelleetEnvironnement),118RoutedeNarbonne,31062Toulouse,France bCNRS,EcoLab,31062Toulouse,France

Keywords: Wastewater Mangroves Photosynthesisrate Chlorophyll Growth Bioremediation

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

After12and18monthsofdailywastewaterdischargeintomangroveplotsinMayotteIsland,SWIndian Ocean,leafpigmentcontent,photosynthesisrateandgrowthofRhizophoramucronataandCeriopstagal mangrovetreeswereevaluatedandcomparedwithsimilarindividualsfromcontrolplots.Chlorophylland carotenoidcontents,measuredusinganHPLCanalyser,weresignificantlyhigherinleavesofmangrove treesreceivingwastewaterdischarges.Photosynthesisandtranspirationrates,analysedusinganLCi portablesystem,increasedsignificantlyformangrovetreesinimpactedplots.Measurementsofleafareas, youngbranchlengthandpropagulelengthshowedsignificantincreasesinplotsreceivingwastewater. TheseresultssuggestabeneficialeffectofdomesticwastewateronR.mucronataandC.tagalmangrovetree functioning.Analysesandobservationsonmangroveecosystemsasawhole–takingintoaccountwater andsedimentcompartments,crabpopulationsandnitrogenandphosphoruscycles–arenevertheless necessaryforevaluationofbioremediationcapacitiesofmangroveecosystems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Mangrovesandbioremediation

The utilisation of mangrove swamps as natural systems for wastewatertreatmenthasbeenproposedasanefficientand low-cost solutionfor tropicalcoastalareas. Characterised bya high primaryproductionandbiomassandestablishedasoftenasnot onnutrient-poorsediments,mangroveecosystemsareconsidered abletoabsorbnutrientsinexcesscontainedinsewage,withoutany majorstructuralorfunctionaldisturbance(Saenger,2002).

Nedwell (1975) showed that the discharge of pretreated wastewaterintoamangroveswampinFijicouldbeameansof reducingeutrophicationincoastalwaters,andthereforesuggested thatmangrovesmightbeusedasthefinalstageinsewage treat-ment.Cloughetal.(1983)publishedoneofthefirstreviewarticles dealingwiththeimpactofsewageonmangroveecosystems.These authors established that the capacity of mangroves to remove nutrientsfromsewagewaslargelydeterminedbyhydrodynamic

∗ Correspondingauthorat:EcoLab-LaboratoireEcologieFonctionnelleet Envi-ronnement,Bâtiment4R1,118routedeNarbonne,31062Toulousecedex9,France. Tel.:+33561558920;fax:+33561558901.

E-mailaddress:francois.fromard@cict.fr(F.Fromard).

factorsintheshorttermandthattheefficiencyoftheprocesses waslargelydependentonthesediment propertiesand biologi-calcharacteristicsoftheecosysteminthelongerterm.Corredor andMorell(1994)demonstratedthattheexcessnitrogencoming fromasewagetreatmentplantinPuertoRicocouldbeabsorbedby themangroveecosystemthroughnaturaldenitrificationprocesses, withoutanydamage.

Inanexplorationofthedifferentaspectsoftheroleof man-groveswampsassinksforwastewater-bornepollutantsthrough numerous experimentsconductedin theHongKong and Shen-zenarea(SouthChina),TamandWong(1995,1996)successively showedthatmangrovesoilsaregoodtrapstofixphosphorusand certainheavymetalsfromwastewater;thatnosignificantchange wasobservedintheplantcommunitystructureorinleaf nutri-entcontentofamangrovesitereceivingwastewaterdischarges for 1year(Wongetal.,1995,1997);and thatlitterproduction and decomposition werenot perturbed (Tamet al., 1998).The additionofwastewatertomangrovesoilsalsoseemstostimulate thegrowthofmicrobialpopulations,probablythroughnutrients andcarboncomponentspresentinwastewater(Tam,1998).More recently,theseauthorsshowedthat amangroveplant commu-nitygrowinginconstructedmicrocosmsreceivingwastewaterwas effective in removingorganicmatter, nitrogenand phosphorus (Wuetal.,2008;Tametal.,2009),Analysinganaturalmangrove areainThailand,Wickramasingheetal.(2009)arrivedtosimilar

conclusions,demonstratingtheefficiencyofmangroveecosystem inwastetreatment,withanenhancementofmangrovegrowthand abundanceofinvertebratepopulations

1.2. Mangrovetreegrowthandnutrientenrichment

Whiletheuseofmangroveecosystemsforremovingpollutants fromsewagedischargesisbecomingratherwelldocumented,the responseofmangroveplantsthemselvesintermsofgrowthshould beanalysedandcontrolled,andresultsinthisdomainarestill con-tradictory.Henley(1978)reportedthatmangrovetreegrowthin theDarwinarea,Australia,wasnotaffectedwhentheyreceived sewagedischarges,andCloughetal.(1983)concludedthatnutrient enrichmentofamangroveecosystemthroughwastewatersupply didnotappearharmfulandinsomecasesmighthaveabeneficial effectongrowthandproductivity.Kelly(1995),investigatingthe impactofsewageeffluentsonmangrovesdominatedbyAvicennia marinainAustralia,foundthattheNandPleafconcentrationswere higher atimpactedsites,but nocleargrowth-enhancingeffects werenoted atthesesamesites.Fromsimilarexperiments con-cerningthetwomangrovespeciesKandeliacandelandAegiceras corniculatum,Wongetal.(1995)didnotfindanysignificant differ-encesinplantgrowthafter1yearofsewagedischarges,butnoted thateffects–positiveoradverse–onvegetationfunctioningcould becomeapparentonlyoveralongerterm.Morerecently,Lovelock etal.(2009)establishedthatnutrientenrichment(NandP)could increasethemortalityofmangrovesinsitescharacterisedbylow annualrainfallandhighsedimentsalinity.Theseauthorsadded thatmortalityratesweresignificantinlandwardscrubforestsand notreedeathsoccurredinfringeforests.Lovelocketal.(2004)and

Martinetal.(2010)specifiedthatNandPenrichmentsignificantly increasedmangrovetreegrowth,butincertainsalinityconditions mightalterthestructureofmangroveforests.

1.3. Mangrovetreefunctioningandenvironmentalstresses

Relationshipsbetweennutrientenrichmentandmetabolic pro-cessesinmangrovesarestilllittledocumented.Peculiarly,dataon photosynthesisrateinmangrovetreesasafunctionalmarkerof theirhealthstatearerare;suchdataaregenerallylinkedto hydro-logical andsalinityparametersandtakeintoaccountpropagule populationsin greenhouseconditions (Ball andFarquhar,1984; YoussefandSaenger,1998;KaoandTsai,1999;Kaoetal.,2001; KraussandAllen,2003).Somestudiesconsideredthelinksbetween mangrovestructure (scrubvs.fringemangrove),mangrovetree heightandphotosynthesischaracteristics(LinandSternberg,1992; Lovelocketal.,2004),andNaidooandChirkoot(2004)established inaspecificcontextthatphotosyntheticperformanceofA.marina wasreducedwhencoaldustwasdepositedontheleafsurfaceof themangrovetrees.

Inotherstudies,pigmentcontentofmangroveleaveshasbeen analysedinrelationtothelightenvironmentofthemangrove for-estcanopy(LovelockandClough,1992;MoorthyandKathiresan, 1997).Rajeshetal.(1998)establishedcorrelationsbetweengrowth rate,photosyntheticandpigmentcharacteristics,andsalinitylevels forCeriopspopulations.MacFarlaneandBurchett(2001)showed thatphotosyntheticpigmentconcentrationdecreasedinA.marina populations impactedby heavy metals, and MacFarlane (2002)

suggested thatphotosyntheticpigmentscouldbeconsideredas biologicalindicatorsofstressformangrovetrees.

1.4. MayotteIslandcontextandbioremediationproject

TheMayotteArchipelago,WestIndianOcean,iscurrently expe-riencing environmentaldegradationlinked toa very important

Fig.1. (a)Thestudysite,aerialphotographyfromultralight.Thetwoimpacted plotsarecharacterisedbyastronggreencolour(whitecirclesmarktheupperlimit ofplots).(b)ColourchangesinCeriopstagalleavesbetweencontrolandimpacted plots.(c)GrowthdifferencesinCeriopstagalbranchesbetweencontrolandimpacted plots.Allpictures:March2009,i.e.after12monthsofdailywastewaterdischarge.

increaseofpopulationandrapideconomicdevelopment.Sewage treatmentislargelydeficientinMayotteandconstitutesamajor problemfor thelocal authorities.Only one sewage plant,built in 2001 and recently renovated (2010), treats wastewater in Mamoudzou,themaintownofMayotte;however,themajorityof effluentflows–directlyorafterhavingcrossedmangroveswamps attheendsofbays–intothevastcoralreeflagoonsurroundingthe island.

In this context, experiments have been launched at Mala-mani,SWMayotte,toevaluatethebioremediationcapacitiesofa mangroveswampreceiving,incontrolledconditions,pretreated domestic wastewater. Water bodies, sediment, vegetation and fauna(crabpopulations)ofmangroveecosystemshavebeentaken into account and analysed (Herteman, 2010; Herteman et al., submittedforpublication)andexperimentsarestillinprogress attheMalamanistudysite.

Wenowreportinvestigationsconcerningmangrovevegetation functioningafter12and18monthsofdailywastewaterdischarge. Anaerialsurveyofthestudysiteclearlyshowedachangeinthe colourofthemangrovecanopy,turningfromlightgreentostrong green, corresponding to mangrove plots receiving wastewater (Fig.1a).Thischangeappeared6 monthsafterthefirstsewage dischargesinthemangrovesandpersisted12monthslater;the changeinleafcolourclearlycorrespondstothedischarge. Obser-vationsinthefieldconfirmedthecolourchangeofthemangrove leaves and also showed obvious differences in branch length betweencontrol andimpactedplots (Fig.1b andc). Toanalyse suchchangesinvegetationandevaluatetheimpactofwastewater, photosyntheticpigmentconcentrations,photosynthesisrateand growthofmangrovetreeswerefollowed inimpactedand non-impactedmangrove plots, in two differentfacies, respectively, dominatedbyCeriopstagal(Perr.)C.B.Robinson andRhizophora mucronataLam.

Fig.2.Thestudyareaandtheexperimentalsite.(a)MayotteIsland,SWIndianOcean.(b)Thestudysite,SWMayotteIsland,betweenMalamanivillageandthelagoon. (c)Experimentalsetting:decantercollectingdomesticwastewaterfromMalamani;pipenetwork;impactedandcontrolplotsinCeriopstagalandRhizophoramucronata mangrovefacies;piezometernetworkforwateranalyses.

2. Materialsandmethods 2.1. Studyarea

MayotteIslandisadependentFrenchoverseasterritoryinthe Comoro Archipelago, located in the Mozambique Channel, SW IndianOcean(Fig.2).Thelittlevolcanicisland(376km2)is

sur-roundedbyanalmostcontinuousbarrierreefsystemenclosingone ofthelargestlagoonsintheworld(1500km2).Mangroveswamps

aredevelopedattheendsofbaysonaround650ha.Thetiderange ishighforanoceanicisland,reachingupto4minspringtides. Mayotte’sclimateismaritimetropical,withawarmwetseason fromNovembertoApril(meanseasonalrainfallandtemperature: 1200mmand27.2◦C,respectively)andacoolerdryseasonfrom

MaytoOctober(210mmand25.1◦C).

ThestudyareaislocatedinChironguiBay,southwestofMayotte (12◦55′S,45◦09′E).Aprimarytreatmentunitsizedfor400-equiv.

inhabitantsdailyreceivesdomesticwastewaterfromMalamani vil-lage.Wastewaterisdecantedandstored,andthencarriedthrough apipenetworktothemangrovearea.Timedeliveryanddischarge volumesareautomaticallycontrolledbyaSOFRELprocessing sys-tem.Wastewater is then deliveredevery secondlow tide onto two mangrove plots respectively dominated by C. tagal and R. mucronataattherateof10m3per24honeach45m×15mplot.

Athird45m×15mplotconnectedtothepipenetwork automati-callyreceiveswastewaterinexcess,particularlyintherainyseason whendischargevolumesexceed20m3perday(Fig.2c).

Photosyntheticpigmentconcentration,photosynthesisrateand growthofmangrovetreeswereanalysed12and18monthsafter commencementof wastewater discharges in thetwo impacted

plots,andintwoequivalentcontrolplots.Theaveragecomposition ofthewastewaterisgiveninTable1,andthevegetationstructure ofthefourplotsispresentedinTable2.

2.2. Photosyntheticpigmentanalyses

Matureandhealthyleavesof12randompatchesineachofthe fourplotswerecollectedinJanuary(wetseason)andApril (begin-ningofdryseason)2009andrapidlystoredinacoldplace(cooler boxduringtransport,then−80◦Cfreezerinlaboratory).Threedisks

18mmindiameterwerecutfromeachleafpatchsample,crushed with50mgFontainebleausand,rinsedwith20mlmethanol,and thenplacedunderultrasoundfor3min.Mixtureswerestoredfor 15minat−20◦C,andthenspin-dried(5minin−1◦Ccentrifugeat

3500rpm).Samplesofthesupernatentweretaken(1ml),filtered through0.2mmsyringefilters,andthenanalysedusingHPLC. 2.3. Photosynthesisandtranspirationrates

Thenetphotosyntheticratewasmeasuredonintact,mature C.tagaland R.mucronataleaveswitha portablephotosynthesis system(ADCBioscientificLtdportable),equippedwitha6.25cm2

leafchamber.Wemeasured150and120leaves,respectively,in eachC.tagalandR.mucronata45m×15mplot.Threesuccessive measurementsweremadefor eachsampledleafatintervalsof 25s.Allmeasurementsweremadebetween10:00and13:00h, onsunnydaysandunderthefollowingconditions: photosyntheti-callyactiveradiance:1000–2000mmolm−2s−1,relativehumidity:

Table1

Nutrientcomposition(mgl−1)ofdomesticwastewaterafterpre-treatmentindecanter.AnalysesrealisedonJuly02,2009,SIEAMLaboratory(Mayotte);April01andOctober

10,2009,ARVAMLaboratory(LaRéunionIsland).

NO3 NO2 NO3+NO2 NH4 PO4

July02,2009 1.40 0.17 1.57 – 8.40

April01,2009 1.09 0.01 1.10 1.18 5.61

October10,2009 0.01 0.02 0.03 1.95 12.55

2.4. Growthratemeasurements

Leafmeasurements:Ineachcontrolandimpactedplot(C.tagal andR.mucronatastands),90matureandhealthyleaveswere ran-domlycollected,andtheirlengthsandwidthsmeasured.Freshand dryweightsweremeasured,andleafareaswerecalculatedusing ImageJsoftwareandleafdigitisation.Leafarea–weight relation-shipsweredetermined.Measurementsweremade inApriland October2009.

Branchmeasurements:IneachC.tagalplot,60brancheswere measuredon15trees,i.e.fourbranchespertree,distributedinthe upper,middleandlowerpartsofthecontrolandimpactedplots. IntheR.mucronataplots,39branchesweremeasuredon13trees, i.e.threebranchespertree,distributedthroughoutthecontroland impactedplots.MeasurementsweremadeinAprilandOctober 2009.

Propagulemeasurements:Ineachcontrolandimpactedplot(C. tagalandR.mucronata),90propaguleswererandomlycollected from9trees,i.e.10propagulespertree,distributedintheupper, middleandlowerpartsofplots.Propagulelengthwasmeasuredin October2009.

2.5. Statisticalanalyses

TheShapirotestwasconductedoneachdataset(pigment con-centration, photosynthesis and transpirationrates, growth rate measurements)andshowedthatdatawerenormallydistributed. Meanvaluesandstandarddeviationwerecalculated.

One-wayANOVA(forp≤0.05andp≤0.01)wasemployedto testthesignificanceofdifferencesbetweencontrolandimpacted plots,betweendatesandbetweenspecies,foreachdatasetexcept propagule lengths, which were analysed using Student’s t-test (p≤0.05).

AllanalyseswereperformedusingthePASTsoftware,version 1.94b(Hammeretal.,2001).

3. Results

3.1. Vegetationstructure

Mangroves onthestudysiteare developedover a lengthof about600mwithaclassicalzonationaccordingtoinundationand salinitygradients,i.e.fromlandwardtoseaward:adegraded Her-itieralittoralisDryand.standattheupperlimitoftidalinfluence, followedbyabarrensaltflator“tanne”surroundedbyoldA.marina

(Forssk.)Vierh.trees, adenseanda lowC.tagal stand progres-sivelymixedwithR.mucronataindividuals,ahighandimportant R.mucronatastandincludingscatteredpatchesofBruguiera gym-norhiza(L.)Lam.,andfinallyonthelagoonsideawell-developed SonneratiaalbaJ.Smithzone.

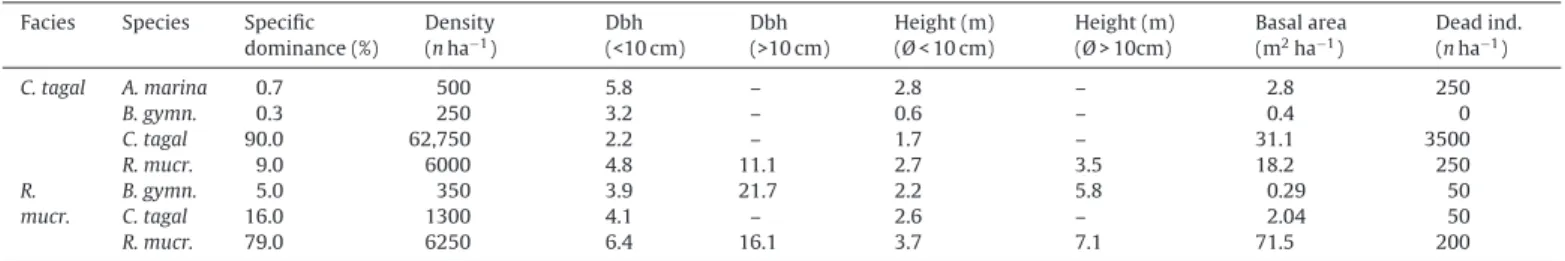

Experimentswereconductedintwomangrovefacies,chosen fortheirrepresentativenessandtheirimportantdevelopmentin mostmangrovestandsinMayotte,namelyC.tagalandR.mucronata facies.StructuresaredescribedinTable2.TheC.tagalfacieswere largelydominatedbytheeponymousspecies,whichrepresented 90%ofthespecificcomposition,with9%forR.mucronataand a fewindividualsofA.marinaintheupperpartofthestandandrare B.gymnorhizainthelowerpart.Totaldensityisveryhighwith 69,500indha−1and62,750indha−1forC.tagal.C.tagal

individu-alsaresmalltreeswith2.2±1.1cmtrunkdiameterand1.7±0.9m inheight.ThesecondfaciesisdominatedbyR.mucronata(79%) withC.tagalindividualsin theupperpart(16%) andpatchesof B.gymnorhiza(5%).Totaldensityislower,with7900indha−1and

6250indha−1forR.mucronata.Themeantrunkdiameterfor

dom-inantindividualsofR.mucronatais16.1±5.2cmwithaheightof 7.1±2.1m.

Itisimportanttonotethatthevegetationstructurewas anal-ysed successively in November 2006, before the first sewage discharges, and in November 2008, 6 months after discharges began.Nosignificantdifferencewasobservedwithintheperiod. Wealsonotedthatthevegetationstructurehadnotchangedafter 12and18monthsofdischargeswhenfunctionalanalyseswere made,intermsofdensityormortalityrates.Regenerationseems tobeenhancedinimpactedplotsanddensityofcanopyaswell. Analysesarecurrentlyunderwaytoquantifytheseprocesses. 3.2. Photosyntheticpigmentconcentration

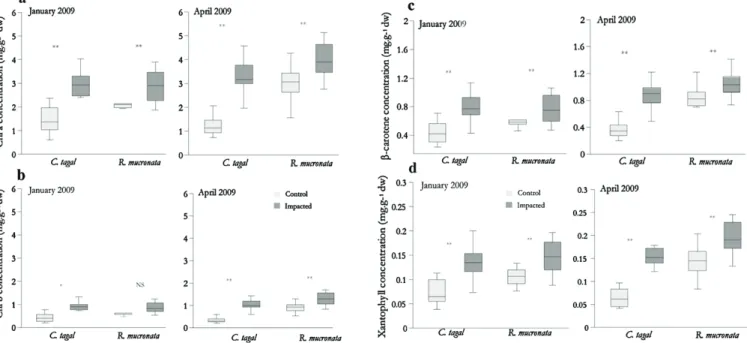

Table3andFig.3showtheresultsofanalysesofchlorophylla andb,carotene,andxanthophyllpigmentsextractedfromC.tagal andR.mucronataleavessampledincontrol andimpactedplots (January2009,April2009).

Pigmentcontentappearstobesignificantlyhigherinplots hav-ingreceivedwastewaterthanincontrolplots,forallpigmenttypes, forthetwodatesanalysedandforbothC.tagalandR.mucronata stands,exceptforchlorophyllb,forwhichresultsarenotsignificant forR.mucronatainJanuary2009.

Pigment concentration increased around twofold between C. tagal control and impacted stands and for the two dates, i.e. from 1.47 to 2.88mgg−1dw (January 2009) and 1.23 to

Table2

Structuralanalysesofmangroveplots,beforewastewaterdischarge(November2006). Facies Species Specific

dominance(%) Density (nha−1) Dbh (<10cm) Dbh (>10cm) Height(m) (Ø<10cm) Height(m) (Ø>10cm) Basalarea (m2ha−1) Deadind. (nha−1) C.tagal A.marina 0.7 500 5.8 – 2.8 – 2.8 250 B.gymn. 0.3 250 3.2 – 0.6 – 0.4 0 C.tagal 90.0 62,750 2.2 – 1.7 – 31.1 3500 R.mucr. 9.0 6000 4.8 11.1 2.7 3.5 18.2 250 R. B.gymn. 5.0 350 3.9 21.7 2.2 5.8 0.29 50 mucr. C.tagal 16.0 1300 4.1 – 2.6 – 2.04 50 R.mucr. 79.0 6250 6.4 16.1 3.7 7.1 71.5 200

Table3

Leafpigmentcontent(mgg−1dw)ofC.tagalandR.mucronata,incontrolandimpactedplotsJanuaryandApril2009.

Ceriopstagal Rhizophoramucronata

January2009 April2009 January2009 April2009

Control Impacted Control Impacted Control Impacted Control Impacted

Chlora 1.47±0.59 2.88±0.76** 1.23±0.41 3.28±0.68** 2.08±0.68 2.87±0.68** 3.01±0.67 4.01±0.75 Chlorb 0.43±0.19 0.89±0.26** 0.34±0.12 1.03±0.22* 0.60±0.1 0.88±0.23** 0.9±0.21 1.31±0.29

Chla:b 3.46±0.2 3.25±0.15 3.64±0.15 3.18±0.14 3.46±0.15 3.28±0.15 3.33±0.21 3.09±0.18

b-carotene 0.43±0.16 0.79±0.18** 0.36±0.12 0.87±0.2** 0.58±0.08 0.76±0.2** 0.82±0.20 1.04±0.18 Xanth. 0.07±0.02 0.13±0.03** 0.06±0.02 0.15±0.03** 0.1±0.01 0.14±0.03** 0.14±0.03 0.19±0.03 Significantdifferencesbetweencontrolandimpactedplotswith*p≤0.05and**p≤0.01.n=12foreachmodality.

3.28mgg−1dw(April2009)forchlorophylla.Incomparison,the

increaseinR.mucronataissignificantbutmoderate,i.e.from2.08 to2.87mgg−1dw(January2009)andfrom3.01to4.01mgg−1dw

(April2009)forchlorophylla.

InC.tagalplots,wenotethatdifferencesbetweenthetwo con-trolplotsandbetweenthetwoimpactedplotsarenotsignificant betweenJanuaryandApril,forallpigments.Forinstance,changes werefrom1.47to1.23(controlplots)and2.88to3.28mgg−1dw

(impactedplots)forchlorophylla,0.43to0.36(control)and0.79 to0.87(impacted)forb-carotene,and0.07to0.06(control)and 0.13to0.15(impacted)forxanthophylls.Similarcomparisonsfor R.mucronata,however,showsignificantincreasesbetweendates, with2.08–3.01(control)and2.87–4.01(impacted)forchlorophyll a,0.58–0.82(control)and0.76–1.04(impacted)forb-carotene,and 0.1–0.14(control)and0.14–0.19(impacted)forxanthophylls. 3.3. Photosynthesisandtranspirationrates

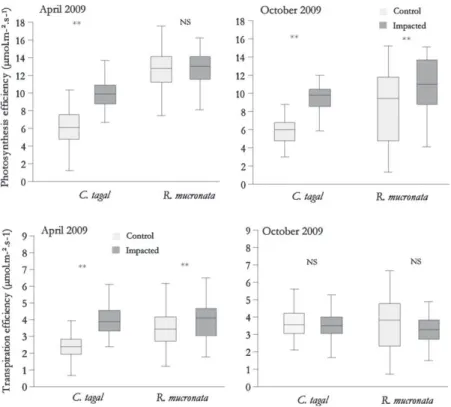

Table4andFig.4summariseresultsforbothparameters,for measurementsmadeinApril2009(endofwetseason)andOctober 2009(endofdryseason).

Photosynthesis rate appears significantly higher in plots receiving wastewater than in control plots, in April (6.14 vs. 9.86mmolm−2s−1)andOctober(5.82vs.9.53mmolm−2s−1)forC.

tagalplotsandinOctober2009only(8.68vs.10.66mmolm−2s−1)

forR.mucronataplots.

Comparisons between species show that the photosynthe-sis rateis significantly higher in R. mucronata than in C.tagal, in both control (12.52 vs. 6.14mmolm−2s−1 in April, 8.68 vs.

5.82mmolm−2s−1 in October,respectively) and impactedplots

(12.62vs.9.86and10.66vs.9.53)andforeachofthedates consid-ered.Thephotosyntheticratealsoappearsslightlybutsignificantly higherforbothspeciesattheendofthewetseason(April)thanat theendofthedryseason(October).

If we compare transpiration rates between control and impacted plots, measurements indicate significant differences for both species in April with higher values in plots receiving wastewater (3.95vs.2.47mmolm−2s−1 for C.tagal,and 4.1vs.

3.53mmolm−2s−1forR.mucronata,respectively),whilethe

dif-ferencesarenotsignificantlydifferentinOctober(3.64vs.3.65for C.tagaland3.27vs.3.64forR.mucronata).

3.4. Growthratemeasurements

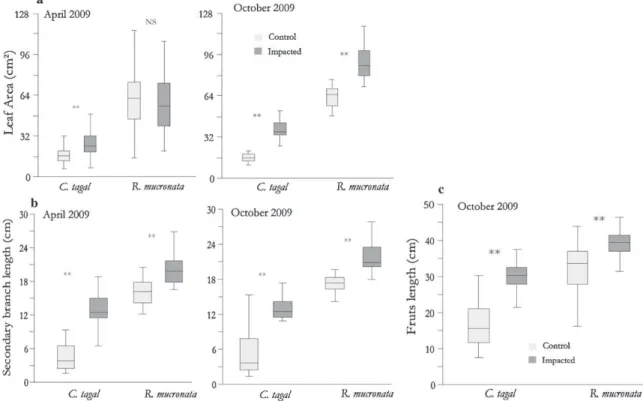

Resultsforleaf(length,width,weight,surfacearea),branchand propagule(length)measurementsafter12and18months(April 2009andOctober2009)arepresentedinTable5andFig.5.

ExceptforR.mucronatameasurementsinApril,leaflengthand widthandconsequentlyleafareaaresignificantlyhigherfor sam-plescollectedinimpactedplotsforbothspeciesanddates,i.e.for leafareas,respectively15.9(controlplots)and37.9cm2(impacted

Fig.3.PigmentconcentrationinCeriopstagalandRhizophoramucronataleaves,collectedincontrolandimpactedplots,Malamanistudysite,JanuaryandApril2009.(a) Chlorophylla.(b)Chlorophyllb.(c)b-Carotene.(d)Xantophyll.Unit:mgg−1dw.

Table4

Photosynthesisrate(mmolm−2s−1)andtranspirationrate(mmolm−2s−1)inleavesofC.tagal(n:150)andR.mucronata(n:120),incontrolandimpactedplots,Apriland

October2009(mean±Sd).

Ceriopstagal Rhizophoramucronata

April2009 October2009 April2009 October2009

Control Impacted Control Impacted Control Impacted Control Impacted

Photosynthesisrate 6.14±1.9 9.86±1.52 5.82±1.3 9.53±1.35 12.5±2.7 12.62±2.39 8.68±4.02 10.66±2.98 Transpirationrate 2.47±0.94 3.95±0.82 3.65±0.89 3.64±0.89 3.53±1.11 4.1±1.18 3.64±1.11 3.27±0.75

plots)forC.tagaland63.2(control)and89.5(impacted)inOctober forR.mucronata.

Theleavesofbothspeciesareslightlyheavier(dryweight)for bothspecies,andleafarea-to-weightratiosaresignificantlyhigher inimpactedconditionsthanincontrolledones.

Concerningbranchlength,allresultsaresignificantwith impor-tantincreases,i.e.4.68–13.38cmforC.tagaland16.04–20.06cmfor R.mucronatainOctober.Nosignificantseasonalchangeappeared inbranchlengthfromApriltoOctoberforeitherspeciesorplot conditions.

Finally, theimpact ofwastewater supply in mangroveplots significantly increased propagule length in both species, i.e. 16.4–32.1cmforC.tagaland32.1–39.1cmforR.mucronata. 4. Discussion

4.1. Leafpigmentconcentrationinmangrovetreesand wastewatereffects

InnaturalconditionsinMayotteIsland,weestablishedthat pig-mentconcentrationwassignificantlyhigherinR.mucronatathanin C.tagalleaves,particularlyforchlorophylla,thetriggerelementof photochemicalprocesses.Chlorophylla:bratios,consideredtobea significantindexofphotosyntheticfunctioning,exhibitverystable andsimilarvaluesforbothspeciesanddates,correspondingto

val-uesgivenbyDasetal.(2002)forR.apiculataandB.gymnorhiza,and byBasaketal.(1996)forR.mucronataandC.decandra.Asnotedby theseauthors,carotenoidcontentisverylowintheRhizophoraceae family,asweobservedinMayotteIslandinnaturalconditions.

Thesupplyofwastewatertomangroveplotsenhancespigment concentrationinmangroveleaves,withclearincreasesfor chloro-phylls,b-caroteneandxanthophyllsinbothspecies.Whilenodata werefoundintheliteraturedirectlyconcerningtherelationships betweenpigmentconcentrationinmangroveleavesand wastewa-tersupplies,manyauthorshaveconsideredpigmentconcentration inrelationtoenvironmentalfactors.MedinaandFrancisco(1997)

establishedthatchlorophyllcontentappearedtobehigherin man-groveleavesofriverinemangrovestandsandlowerinleavesof mangrovesfromdrysites,andaddedthat NandPleaf concen-trationsandleafareasvariedinthesamewaybetweendryand wetsites.Authorsinterpretedsuchresultsasinteractionsbetween salinityand waterstresses, inrelationtonutrient supplies and photosyntheticproductivity.MacFarlaneandBurchett(2001)and

MacFarlane(2002)showedlinksbetweenleafchlorophylls(a+b) andcarotenoidcontentofA.marinaandheavymetal concentra-tioninmangrovesediment.Yeetal.(2003)examiningtheeffects ofwaterloggingongrowthandphysiologicalcharacteristicsofB. gymnorhiza and Kandelia candel(Rhizophoraceae), showed that chlorophyllandcarotenoidconcentrationsincreasedwhen water-loggingdurationandintensityincreased.

Fig.4.PhotosynthesisrateandtranspirationratemeasuredonCeriopstagalandRhizophoramucronataleaves,incontrolandimpactedplots,Malamanistudysite,Apriland October2009.Unit:mmolm−2s−1.

Table5

Shootlength(cm),internodenumberandleafnumberpershootforC.tagalandR.mucronata,incontrolandimpactedplots,AprilandOctober2009(mean±Sd,n=60).

Ceriopstagal Rhizophoramucronata

April October April October

Control Impacted Control Impacted Control Impacted Control Impacted

Shootlength 4.68±2.5 13.38±4.26 5.01±3.44 12.82±1.5 16.04±2.11 20.06±2.63 9.16±6.19 8.88±6.02

Internodesnumber 1.3±0.5 3.3±0.9 2.1±0.7 3.3±0.9 3.7±1.4 2.8±0.5 17.3±1.2 21.2±2.0

Leafnumberpershoot 8.6±5.5 9.6±7.3 – 5.2±1.3 5.9±1.5 5.3±1.0 4.7±1.7 4.2±1.1

WastewatersupplytoimpactedmangroveplotsinMalamani contributesbothtolowersalinitylevel–freshwaterisaddedto theecosystem–andtoincreasedNandPlevels.Theaverage com-positionofsewage(Table1)indicatestheamountandthenatureof nitrogenandphosphoruscompoundsdelivereddailytomangrove plots.Moreover,weestablishedthatwastewaterdeliveredto man-grovesatlowtiderapidlyseepsintosedimentandisprogressively absorbedbyvegetation,andthatNandPcompoundsareatleast partiallyusedbymangrovetrees(Herteman,2010;Hertemanetal., submittedforpublication).Thechangeinthecolourofthe vege-tationofimpactedplots(Fig.1)alsoreflectstheseprocessesand correspondstotheincreaseinleafpigmentconcentration.As pro-posedbytheauthorscitedabove,pigmentconcentrationmaythus beconsideredamarkerofstressconditionsformangrovetrees,or amarkerofchangeinmangrovefunctioning,revealingpollution withheavymetals(MacFarlaneandBurchett,2001;MacFarlane, 2002)oranexcessofnutrient,aswedemonstratedinour Mala-maniexperiments.Fromamoregeneralpointofview,studiesof pigmentcontentinhigherplantsasbiomarkersarerare,and essen-tiallyconcernedmicro-algae,wherepigmentcontentis directly linkedtobiomass(Wilhelmetal.,1995).Brainand Cedergreen (2009),inarecentreviewonbiomarkersinaquaticplants, indi-catedadvantagesforconsideringpigmentcontentasabiomarker: itisaneasy-to-measureandrobustparameterand,furthermore, visualobservation,asinourMalamaniexperiments,maypreclude

thenecessityofmeasuringpigmentcontent.Theseauthorsadded thatchlorophyllsandcarotenoidsweretheprimarylight-capturing pigmentsinhigherplants,absorbinglightenergyfor photosynthe-sis.Nutrientstatus,withlightintensityortemperature,isoneof thefactorsaffectingthecontentofphotosyntheticpigments.At highnutrientavailability,andparticularlywithexcessN,pigment contentincreasesandenhancescarbonfixation.

4.2. Photosyntheticprocesses

Pigment concentration is directly linked to photosynthetic activity,andphotosyntheticratesandpigmentcontent,i.e. chloro-phylla:bratio,havebeenfoundtobecorrelated(Andersonetal., 1988;Dasetal.,2002).

Measurementsofphotosynthesisrateincontrolplotsin Mala-maniclearlyindicatedifferencesbetweenspecies,withthehighest valuesobtainedinR.mucronata,wherethehighestpigment con-centrationswerealsofound.Theurietal.(1999)obtainedsimilar resultswithhighervaluesforR.mucronatathanforC.tagalin man-grovestandsinKenya.Nevertheless,theseauthorsgloballyfound lowervaluesinKenyanmangrovesthaninMayotte(around1.5 and1.2mmolm−2s−1 forR.mucronataandC.tagal,respectively)

andimportantseasonalvariation,withtwofoldvaluesinthewet season(around4.0and3.0mmolm−2s−1,respectively)while

sea-sonalchangesinMalamaniwerenotsignificant.Transpirationrate

Fig.5.Changesinleafarea(a),branchlength(b)andpropagulelength(c)ofCeriopstagalandRhizophoramucronataincontrolandimpactedplots,Malamanistudysite, AprilandOctober2009.Units:cm2andcm.

levelsarealsogreaterinMayotte(2.45–3.65mmm−2s−1)thanin

Kenyanmangrove(0.78–0.94mmm−2s−1).

Clough et al. (1997) and Clough (1998) found high values of photosynthetic rates for R. apiculata (average rate for the whole canopy:9.0mmolm−2s−1)and different Rhizophoraceae

(6.13–12.9mmolm−2s−1),withhighervaluesforRhizophoraspp.

andlowervaluesforC.australis.Theseauthorsaddedthatrates ofphotosynthesismaybesubstantiallylowerinmangrovestands characterisedbyhigheraridityandsalinityconditionswithvalues around4–5mmolm−2s−1.

In the mangrove stands of Malamani, wastewater supplies clearlycontributetoincreasedphotosyntheticratesinimpacted mangroveplots astheyleadtoanincrease inpigment concen-trations.Aswenoticedabove,wastewatercontributes tolower salinityrates,enrichesthemangroveecosysteminNandP nutri-ents, and consequently enhances photosynthesis rate. Sobrado (2000)andLietal.(2008)indicatedsimilarrelationshipsbetween salinityconditionsandphotosynthesisprocessesfordifferent man-grovetreesincludingRhizophoraceae,andKaoetal.(2001)showed thatanincreaseinNavailabilityincreasedphotosyntheticratesfor theRhizophoraceaeK.candel.Lietal.(2008)addedthathighlevels ofNaconcentrationinmangrovetreesinhibitedelectrontransport inphotosyntheticprocessesandconsequentlyledtoadecreasein photosyntheticefficiency.

4.3. Mangrovegrowthratesandwastewatersupplies

Increasedmangrovegrowthrates(leafdimensionsandsurface areas,branchlength)observedinimpactedplotsatthestudysite areadirecteffectofenhancementinphotosynthesisrateandof theincreaseinleafpigmentconcentration.Thesupplyof fresh-water andnutrients(Nand P),particularlythroughwastewater discharges,isknowntoinduceanincreaseinmangrovetreegrowth (Cloughetal.,1983)byactingasafertilisersupplyinthe ecosys-tem(BotoandWellington,1983).Onufetal.(1977)alsoobserved thataRhizophoramangrovestandnaturallyenrichedwithguano fromabirdcolonyexhibitedsignificantenhancementofgrowth.

Clough etal. (1983),analysing alltheseresults, concludedthat “nutrient enrichmentfromfertilization orfromsewageeffluent isnotlikelytobedeleterioustomangroves,andmaybe benefi-cialwherethenutrientstatusofthemangrovesislow”.Linand Sternberg(1992),andmore recentlyLovelock andFeller(2003)

andLovelocketal.(2004),whileanalysingfunctionaldifferences betweenscrubandfringemangroves,establishedthatCO2

assimi-lationrateandphotosyntheticefficiencyseemtobelowerinscrub facies,alsocharacterisedbyhighsalinitylevels.Conversely, fertil-isationbyNandPsuppliesmayinducesignificantshootgrowthin dwarfmangrovestands.

Recentpapers,however,haveemphasisedpotentialnegative consequencesofexcessivenutrientenrichmentinmangroves.They established, forinstance, thatexcessive N supplymight induce changes in root-to-shoot ratio (development of shoots at the expenseofroots)andincreasethevulnerabilityofmangrovestands in high-saline environments (Martin et al.,2010), or even lead to the deathof mangrovetrees in high salinity and low rain-fallconditions(Lovelocketal.,2009).Inthislaststudy,nutrient enrichmentseemstohavebeenthrougha single,massive sup-ply annuallyor biannually, i.e.300gof ureaorphosphate into holes cored oneither side ofthe treestems.Notice that these amounts correspond tothetotal amountof N provided toour impacted plots in a wholeyear, but delivereddaily every sec-ondlowtidetoourexperimentalmangrovestands.Thekinetics ofabsorptionandassimilationofnutrientsisthencertainly dif-ferentinthetwocases,andthustheconsequencesonmangrove

treemetabolismwillbedifferentaswell.Whilenonegativeeffect onmangrovevegetationappearedafter18monthsofwastewater suppliesinthemangrovesofMalamani,wewillstillrequire con-tinuingcontrolexperimentstoassessthelong-termefficiencyof bioremediationthroughmangroveecosystem.Inanotherdomain,

Penha-Lopesetal.(2010)indicated,frommesocosmexperiments, thatsewagecontaminationcauseddisturbancestogastropod pop-ulations(Terebraliapalustris)associatedwithmangrovetrees.In theMalamani studysite, preliminaryresultsdidnot showany changeincrabpopulationsimpactedbywastewater(Herteman, 2010),butfurtherexperimentsareplannedtoevaluatepotential effectsoveralongerterm.

5. Conclusions

Thepresentstudyshowedthatdomesticwastewaterdischarges inducedimportantchangesinmangrovevegetation.Inparticular, thewastewater:

•increasedleafpigmentcontentinC.tagalandR.mucronatastands impactedwith12–18monthsofdailysupplies;

•enhancedsignificantlyphotosyntheticactivityandtranspiration rate;and

•inducedsignificantincreasein leafareaand branchlengthof impactedmangrovestands.

Atthesametime,noevidentmodificationappearedingeneral structureorfunctioningofmangrovevegetation.

Ifourresultsseem todemonstratethatpretreated domestic wastewatermayhavebeneficialeffectsonmangrovefunctioning, asurveyoftheliteratureneverthelessshowsthatNandPexcess, broughtthroughdomesticwastewaterorexperimentalsupplies, couldincertainconditionsandoveralongterminduce dysfunc-tioninginmangrovevegetation.

Furtherexperimentationandanalysesarenecessarybeforewe canclearly definethepossiblerole of mangroveecosystemsin bioremediationofdomesticwastewater.

SuchexperimentationiscurrentlyinprogressintheMalamani studysite,takingintoaccountthedifferentcompartmentsofthe mangroveecosystemand theirinteractions,i.e. saltyand fresh-waterbodies,sediment, crabpopulationsand thestructure and functioningof themangrovevegetation. While thepreliminary resultsinthispapershowthatwastewateriseffectivelyabsorbed bymangrovetrees andinduces enhancementofmangrovetree functioning,globalNandPbalancesmustbeestablishedfor bet-terquantification.Anotheravenueofresearch,alsoinprogress,is toimprovewastewatertreatmentintheprimarytreatmentunit beforeitsdischargeintomangrovestands.

Acknowledgements

Thisworkwaspartofaprogrammeontheroleofthemangrove ecosysteminwastewatertreatmentinMayotteIsland,co-funded bytheWaterSyndicateofMayotte(SIEAM,2006–2010)andthe FrenchNationalResearch Centre(CNRS)through theEcological EngineeringProgramme(2007).

Thefirstauthorisa doctoralresearcherfundedbythe Asso-ciationNationaledelaRechercheTechnique(ANRT)throughthe CIFREGrant250/2006.

References

Anderson,J.M.,Chow,W.S.,Goodchild,D.,1988.Thylakoidmembraneorganization insun/shadeacclimation.Aust.J.PlantPhysiol.1,11–26.

Ball,M.C.,Farquhar,G.D.,1984.Photosyntheticandstomatalresponsesoftwo man-grovespecies.AegicerascorniculatumandAvicenniamarina,tolongtermsalinity andhumiditycondition.PlantPhysiol.74,1–6.

Basak,U.C.,Das,A.B.,Das,P.,1996.Chlorophylls,carotenoids,proteinsandsecondary metabolitesinleavesof14speciesofmangrove.Bull.Mar.Sci.58,654–659. Boto,K.G.,Wellington,J.T.,1983.Nitrogenandphosphorusnutritionalstatusofa

northernAustralianmangroveforest.MarEcol.Prog.Ser.11,63–69. Brain,R.A.,Cedergreen,N.,2009.Biomarkersinaquaticplants:selectionandutility.

Rev.Environ.Contam.Toxicol.198,49–109.

Clough,B.,1998.Mangroveforestproductivityandbiomassaccumulationin Hinch-inbrookChannel,Australia.MangroveSaltMarshes2,191–198.

Clough,B.F.,Boto,K.G.,Attiwill,P.M.,1983.Mangrovesandsewage—are-evaluation. In:Teas,G.H.(Ed.),Proceedingsofthe2ndInternationalSymposiumonBiology andManagementofMangroves,PapuaNewGuinea.W.JunkPublisher,The Hague,pp.151–161.

Clough,B.F.,Ong,J.E.,Gong,W.K.,1997.Estimatingleafareaindexand photosyn-theticproductionincanopiesofthemangroveRhizophoraapiculata.Mar.Ecol. Prog.Ser.159,285–292.

Corredor,J.E.,Morell,J.M.,1994.Nitratedepurationofsecondarysewageeffluents inmangrovesediments.Estuaries17,295–300.

Das,A.B.,Parida,A.,Basak,U.C.,Das,P.,2002.Studiesonpigments,proteinsand photosyntheticratesinsomemangrovesandmangroveassociatesfrom Bhi-tarkanika,Orissa.Mar.Biol.141,415–422.

Hammer,O.,Harper,D.A.T.,Ryan,P.D.,2001.PAST:palaeontologicalstatistics soft-warepackageforeducationanddataanalysis.Palaeontol.Electron.4,1–9. Henley,D.A.,1978.Aninvestigationofproposedeffluentdischargeintoatropical

mangroveestuary.In:ProceedingofInternationalConferenceonWater Pollu-tionControlinDevelopingCountries.September1978,Thailand,pp.43–64. Herteman,M.,2010.Evaluationdescapacitésbioremédiatricesd’unemangrove

impactéepardeseauxuséesdomestiques.Applicationausite-pilotede Mala-mani,Mayotte.ThèseUniversitédeToulouse.

Herteman,M.,Lambs,L.,Fromard,F.,Sanchez-Perez,J.,Muller,E.Watercirculation andstoragecapacityinamangroveswampofMayotteIsland,submittedfor publication.

Kao,W.Y.,Tsai,H.C.,1999.Thephotosynthesisandchlorophyllafluorescencein seedlingsofKandeliacandel(L.)DrucegrownunderdifferentnitrogenandNaCl controls.Photosynthetica37(3),405–412.

Kao,W.Y.,Tsai,H.C.,Tsai,T.T.,2001.EffectofNaClandnitrogenavailabilityon growthandphotosynthesisofseedlingsofamangrovespecies,Kandeliacandel (L.)Druce.J.PlantPhysiol.158,841–846.

Kelly,T.,1995.Effectsoflong-termdischargesoftreatedsewageonthenutrient statusofadjacentmangrovecommunities.UnpublishedThesis,SouthernCross University,Lismore,Australia.

Krauss,K.W.,Allen,J.A.,2003.Influencesofsalinityandshadeonseedling photosyn-thesisandgrowthoftwomangrovespecies,RhizophoramangleandBruguiera sexangula,introducedtoHawaii.Aquat.Bot.77,311–324.

Li,N.Y.,Chen,S.L.,Zhou,X.Y.,Li,C.Y.,Shao,J.,Wang,R.G.,2008.EffectofNaClon photosynthesis,saltaccumulationandioncompartmentationintwomangrove species,KandeliacandelandBruguieragymnorhiza.Aquat.Bot.88,303–310. Lin,G.,Sternberg,L.daS.L.,1992.Comparativestudyofwateruptakeand

photosyn-theticgasexchangebetweenscrubandfringeredmangrove,Rhizophoramangle L.Oecologia90,399–403.

Lovelock,C.E.,Clough,B.F.,1992.Influenceofsolar-radiationandleafangleonleaf xanthophyllconcentrationsinmangroves.Oecologia91,518–525.

Lovelock,C.E.,Feller,I.C.,2003.Photosyntheticperformanceandresourceutilization oftwomangrovespeciescoexistinginahypersalinescrubforest.Oecologia134, 455–465.

Lovelock,C.E.,Feller,I.C.,McKee,K.L.,Engelbrecht,B.M.,Ball,M.C.,2004.Theeffect ofnutrientenrichmentongrowth,photosynthesisandhydraulicconductance ofdwarfmangrovesinPanama.Funct.Ecol.18,25–33.

Lovelock, C.E., Ball, M.C., Martin, K.C., Feller, I.C., 2009. Nutrient enrich-ment increases mortality of mangroves. PLoS ONE 4 (5), e5600, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005600.

MacFarlane,G.R.,2002.LeafbiochemicalparametersinAvicenniamarina(Forsk.) Vierhaspotentialbiomarkersofheavymetalstressinestuarineecosystems. Mar.Pollut.Bull.44,244–256.

MacFarlane,G.R.,Burchett,M.D.,2001.Photosyntheticpigmentsandperoxidase activityasindicatorsofheavymetalstressinthegreymangrove,Avicennia marina(Forsk.)Vierh.Mar.Pollut.Bull.42,233–240.

Martin,K.C.,DanBruhn,Lovelock,C.E.,Feller,I.C.,Evans,J.R.,Ball,M.C.,2010. Nitro-genfertilizationenhanceswater-useefficiencyinasalineenvironment.Plant Cell.Environ.33(3),344–357.

Medina,E.,Francisco,M.,1997.OsmolalityanddeltaC-13ofleaftissuesofmangrove speciesfromenvironmentsofcontrastingrainfallandsalinity.Estuar.Coast. ShelfSci.45,337–344.

Moorthy,P.,Kathiresan,K.,1997.Influenceofultraviolet-Bradiationon photo-syntheticandbiochemicalcharacteristicsofamangroveRhizophoraapiculata. Photosynthetica34,465–471.

Naidoo,G.,Chirkoot,D.,2004.Theeffectsofcoaldustonphotosynthetic perfor-manceofthemangrove,AvicenniamarinainRichardsBay,SouthAfrica.Environ. Pollut.127,359–366.

Nedwell,D.B.,1975.Inorganicnitrogen-metabolisminaeutrophicatedtropical mangroveestuary.WaterRes.9,221–231.

Onuf,C.P.,John,M.,Teal,J.M.,Valiela,I.,1977.Interactionsofnutrients,plantgrowth andHerbivoryinamangroveecosystem.Ecology58(3),514–526.

Penha-Lopes,G.,Bartolini,F.,Limbu,S.,Cannicci,S.,Mgaya,Y.,Kristensen,E.,Paula, J.,2010.EcosystemengineeringpotentialofthegastropodTerebraliapalustris (Linnaeus1767)inmangrovewastewaterwetlands:acontrolledmesocosm experiment.Environ.Pollut.158(1),258–266.

Rajesh, A., Arumugam, R., Venkatesalu, V., 1998. Growth andphotosynthetic characteristicsofCeriopsroxburghianaunderNaClstress.Photosynthetica35, 285–287.

Saenger,P.,2002.MangroveEcologySilvicultureandConservation.Kluwer Aca-demicPublishers,Dordrecht.

Sobrado,M.A.,2000.Relationofwatertransporttoleafgasexchangepropertiesin threemangrovespecies.TreesStruct.Funct.14,258–262.

Tam, N.F.Y.,1998. Effects of wastewater discharge on microbialpopulations andenzyme activitiesinmangrove soils.Environ.Pollut.102 (2–3),233– 242.

Tam,N.F.Y.,Wong,Y.S.,1995.Mangrovesoilsassinksforwastewater-borne pollu-tants.Hydrobiologia295,231–241.

Tam,N.F.Y.,Wong,Y.S.,1996.Retentionanddistributionofheavymetalsin man-grovesoilsreceivingwastewater.Environ.Pollut.94,283–291.

Tam,N.F.Y.,Wong,Y.S.,Lan,C.Y.,Wang,L.N.,1998.Litterproductionand decompo-sitioninasubtropicalmangroveswampreceivingwastewater.J.Exp.Mar.Biol. Ecol.226,1–18.

Tam,N.F.Y.,Wong,A.H.Y.,Wong,M.H.,Wong,Y.S.,2009.Massbalanceofnitrogenin constructedmangrovewetlandsreceivingammonium-richwastewater:effects oftidalregimeandcarbonsupply.Ecol.Eng.35,453–462.

Theuri,M.M.,Kinyamario,J.I.,VanSpeybroeck,D.,1999.Photosynthesisandrelated physiologicalprocessesintwomangrovespecies,Rhizophoramucronataand Ceriopstagal,atGaziBay,Kenya.Afr.J.Ecol.37,180–193.

Wickramasinghe,S.,Borin,M.,Kotagama,S.W.,Cochard,R.,Anceno,A.J.,Shipin, O.V.,2009.Multi-functionalpollutionmitigationinarehabilitatedmangrove conservationarea.Ecol.Eng.35,898–907.

Wilhelm,C.,Volkmar,P.,Lohmann,C.,Becker,A.,Meyer,M.,1995.TheHPLC-aided pigmentanalysisofphytoplanktoncellsasapowerfultoolinwater-quality control.J.WaterSupplyRes.Technol.Aqua44,132–141.

Wong,Y.S.,Tam,N.F.Y.,Lan,C.Y.,1997.Mangrovewetlandsaswastewatertreatment facility:afieldtrial.Hydrobiologia352,49–59.

Wong,Y.S.,Lan,C.Y.,Chen,G.Z.,Li,S.H.,Chen,X.R.,Liu,Z.P.,1995.Effectofwastewater dischargeonnutrientcontaminationofmangrovesoilsandplants. Hydrobiolo-gia295,243–254.

Wu,Y.,Chung,A.,Tam,N.F.Y.,Pi,N.,Wong,M.H.,2008.Constructedmangrove wet-landassecondarytreatmentsystemformunicipalwastewater.Ecol.Eng.34, 137–146.

Ye,Y.,Tam,N.F.Y.,Wong,Y.S.,Lu,C.Y.,2003.Growthandphysiologicalresponsesof twomangrovespecies(BruguieragymnorhizaandKandeliacandel)to waterlog-ging.Environ.Exp.Bot.49(3),209–221.

Youssef,T.,Saenger,P.,1998.Photosyntheticgasexchangeandaccumulationof phytotoxinsinmangroveseedlingsinresponsetosoilphysico-chemical char-acteristicsassociatedwithwaterlogging.TreePhysiol.18,317–324.