AVIS

Ce document a été numérisé par la Division de la gestion des documents et des archives de l’Université de Montréal.

L’auteur a autorisé l’Université de Montréal à reproduire et diffuser, en totalité ou en partie, par quelque moyen que ce soit et sur quelque support que ce soit, et exclusivement à des fins non lucratives d’enseignement et de recherche, des copies de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse.

L’auteur et les coauteurs le cas échéant conservent la propriété du droit d’auteur et des droits moraux qui protègent ce document. Ni la thèse ou le mémoire, ni des extraits substantiels de ce document, ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement reproduits sans l’autorisation de l’auteur.

Afin de se conformer à la Loi canadienne sur la protection des renseignements personnels, quelques formulaires secondaires, coordonnées ou signatures intégrées au texte ont pu être enlevés de ce document. Bien que cela ait pu affecter la pagination, il n’y a aucun contenu manquant.

NOTICE

This document was digitized by the Records Management & Archives Division of Université de Montréal.

The author of this thesis or dissertation has granted a nonexclusive license allowing Université de Montréal to reproduce and publish the document, in part or in whole, and in any format, solely for noncommercial educational and research purposes.

The author and co-authors if applicable retain copyright ownership and moral rights in this document. Neither the whole thesis or dissertation, nor substantial extracts from it, may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s permission.

In compliance with the Canadian Privacy Act some supporting forms, contact information or signatures may have been removed from the document. While this may affect the document page count, it does not represent any loss of content from the document.

Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in young males diagnosed with testicular or

. lymphatic cancer

par

Roxane Robitaille

Département de Psychologie Faculté des Arts et Sciences

Thèse présentée à la Faculté des Études Supérieures en vue de l'obtention du grade de Ph.D. en psychologie- recherche et intervention

option clinique

Novembre, 2008

î

Université de Montréal Faculté des Études Supérieures

Cette thèse intitulée :

Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in young males diagnosed with testicular or lymphatic cancer

présentée par: Roxane Robitaille

A été évaluée par un jury composé des personnes suivantes:

Francince Cyr, Ph.D. Président-rapporteur Zeev Rosberger, Ph.D. Directeur de recherche Marie Achille, Ph.D. Co-directrice Joanne-Lucine Rouleau, Ph.D. Membre du jury Josée Savard, Ph.D. Examinateur externe Louise Bouchard, Ph.D. Représentant du doyen de la FES

RÉSUMÉ

Les cancers testiculaires et lymphatiques (maladie de Hodgkin's et Non-Hodgkin's) sont parmi les cancers les plus répandus chez les jeunes hommes âgés de 18 à 45 aps. Ce n'est que récemment que le cancer fut considéré comme un événement suffisamment stressant pour répondre aux critères diagnostics du Trouble de Stress Post-traumatique (TSPT) avec des taux d'incidence variant entre 1.9 et 35.1 % (Kangas, Henry & Bryant, 2002). Ce projet en deux volets a pour but d'explorer les symptômes de TSPT et de détresse reliés au cancer, de déterminer la fréquence des symptômes de TSPT chez les jeunes hommes atteints de cancer, d'établir une trajectoire développementale des symptômes de TSPT dans la première année suivant le diagnostic de cancer, d'identifier les facteurs de risque qui prédisent les symptômes de TSPT et de décrire les moyens de coping et de croissance post-traumatique des survivants. Dans la première étude, 22 survivants de cancer testiculaire ou lymphatique ont participés à une entrevue semi-structurée de façon rétrospective. Le verbatim de ces entrevues fut analysé selon la méthode d'analyse qualitative de Miles et Huberman (1984). La période du diagnostic fut vécue comme un choc et une menace s'accompagnant souvent d'anticipation anxieuse, de déni ou

d'évitement. Les réactions les plus communes lors de la période des traitements étaient le désespoir et le découragement.

A

long-terme dans la période post-traitement, certains firent l'expérience d 'une réaction émotionnelle retardée et les symptômes de TSPT (présence accrue d'intrusions et d'évitement) devinrent plus courants. L'optimisme était la méthode de coping précoce la plus commune et plusieurs rapportèrent une croissance post-traumatique dans la période de survie à long-terme. Les résultats de cette étude sont conformes au modèle socio-cognitiftransitionnel d'ajustement (social-cognitivenouvellement diagnostiqués avec le cancer (n=92) et des volontaires de la communauté (n=88) ont été recrutés et suivis prospectivement pour une période de 12 mois. Des niveaux symptomatiques sévères de TSPT furent observés chez jusqu'à un maximum de 14.3% des patients atteints de cancer et chez jusqu'à un maximum de 5.7% des .

volontaires lors de la première année suivant le diagnostic. Des analyses de variance (ANOV As) à mesures répétées ont révélés des taux plus élevés de symptômes de TSPT sur le lES au temps 1 et 2, sur le PCL-C au temps 2, 3 et 4, de dépression au temps 2 et d'anxiété aux temps 1 et 2 chez les hommes atteints de cancer comparativement aux volontaires. Cependant, les deux groupes n'étaient pas différents quant à leur niveau de stress perçu et dans la qualité de vie rapportée. De plus, une augmentation significative des symptômes de TSPT fut observée pour les patients atteints de cancer mais pas pour les volontaires. Les résultats de ces études suggèrent que la détresse, sous la forme de dépression et d'anxiété, était élevée mais tend à diminuer avec le passage du temps. Par ailleurs, les manifestations précoces de TSPT prédisent fortement les symptômes de TSPT à un moment ultérieur et il y a une augmentation des symptômes de TSPT avec le passage du temps. L'évitement et le déni sont communs au moment du diagnostic, mais les intrusions gagnent graduellement de l'importance. Ceci pourrait indiquer qu'une forme de traitement cognitif de l'expérience stressante a lieu qui permettrait aux survivants de revisiter leurs croyances existantes et de faire l'expérience de divers niveaux de croissance post-traumatique.

Mot clés: Trouble de stress post-traumatique, croissance post-traumatique, cancer, détresse, jeunes hommes, traitement cognitif.

ABSTRACT

Testicular and lymphatic cancers (Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's disease) are among the

most common cancers in young males aged 18 to 45. It has recently been acknowledged

that symptoms ofposttr~umatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be present following a cancer

diagnosis, with incidence varying between 1.9% to 35.1 % (Kangas, Henry & Bryant,

2002). This project aimed to explore the cancer related symptoms ofPTSD and distress, to determine the frequency of PTSD symptoms in young male cancer patients, to

establish a timeline for PTSD symptoms in the first year following a cancer diagnosis, to identify risk factors that were predictive ofPTSD symptoms, and to report on the coping and posttraumatic growth experienced by survivors. In study 1, verbatim accounts of 22 survivors of either testicular or lymphatic cancer were collected retrospectively.

Qualitative data was analyzed according to the Miles and Huberman (1984) approach. Survivors' appraisal oftheir diagnosis as a being a shock and a threat were common, as were and anxious anticipation, avoidance, and denial. In the treatment phase, despair and discouragement were most common. In the long-term, PTSD symptoms (increased presence of intrusions and avoidance) and delayed emotional reactions were reported. Optimism was common in early coping and many reported posttraumatic growth in the long-term survival phase. These findings were consistent with the social-cognitive transition model of adjustment (Brennan, 2001). In study 2, newly diagnosed cancer patients (n=92) and community controls (n=88) were recruited and followed

prospectively over a period of 12 months. Severe PTSD symptoms were observed in up to 14.3 % of cancer patients in the first year following diagnosis, compared to 5.7% of controls. Repeated measure analyses of variance (ANOVAs) revealed that cancer patients had higher levels ofPTSD symptoms, at time 2 and 4 on the lES, at times 2, 3 and 4 on

the PCL-C, at time 2 for depression, and at times 1 and 2 for anxiety than control s, but were not different in perceived stress, nor in quality of life. Furthermore, there was a significant increase in PTSD symptoms over time. Initial scores ofPTSD were the only significant predictor of PTSD at time 4. Furthermore, there was a significant increase in PTSD symptoms over time for the cancer group, but not for controls. Taken together these results suggest that di stress in the form of depression and anxiety was elevated but tended to diminish over time. Moreover, early manifestations ofPTSD strongly predict later PTSD symptoms and there was an increase in PTSD symptoms over time.

A voidance and deniai were common at the time of diagnosis, but intrusions gradually became more important. This may indicate a that a form of cognitive processing of the stressful experience is taking place and allows sorne survivors to revisit their existing life assumptions and experience differing Ieveis of posttraumatic grciwth.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth, cancer, distress, young males, cognitive processing

TABLE OF CONTENTS RÉSUMÉ ... 3 ABSTRACT ... 5 LIST OF TABLES ... 9 LIST OF FIGURES ... 10 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... : ... Il STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP ... 12 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 13

SECTION 1: GENERAL lNTRODUCTION ... 15

Testicu1ar Cancer ... 15

Lytnphatic cancers ... : ... 18

Cancer-related distress ... 19

Cancer-related PTSD ... 20

Risk factors for PTSD ... 25

Cognitive Processing and Posttraumatic Growth ... 27

Rationale and Purpose ... 30

SECTION 2: FROM PTSD TO POSTTRAUMA TIC GROWTH: TRANSITIONAL PROCESSES ASSOCIA TED WITH THE CANCER EXPERIENCE ... 33

Abstract ... 34

Introduction ... : ... 35

1 Methods ... ' ... 39

Study Design and procedures ... 39

Data analysis ... 41

Findings ... 43

Sample characteristics ... 43

Psychological reactions at diagnosis ... 44

Psychological reactions during treatment ... 48

Post-treatment and long-term psychological impact. ... 49

Coping ... 52 Posttraumatic growth ... 54 Discussion ... 55 Limitations ... 61 Conclusions ... 62 References ... 63 Table ... 67

SECTION 3: SYMPTOMS OF PTSD lN YOUNG MALES RECENTLY DIAGNOSED WITH CANCER ... 69 Introduction ... 71 Rationale ... 74 Hypotheses ... 1 . . . 74 Methods ... 75 Participants ... 75

Study design and procedures ... : ... 75

Measures ... 76

Findings ... 81

PTSD symptoms: descriptive data ... 84

Repeated measure ANOV As (General Iinear model) ... 86

Correlations between independent variables and PTSD ... 90

Regressions ... 92 Discussion ... 94 Conclusion ... 101 J References ... 102 Tables ... · ... 111 Figures ... 114

APPENDIX 1: Events reported as history of exposure to traumatic events ... 117

APPENDIX 2: Characteristics of drop-outs vs. completed sample ... 118

APPENDIX 3: Events reported by controls on the lES and PCL-C at time 1.. ... 121

APPENDIX 4: Figures for the cross-sectional data ... ~ ... 123

SECTION 4: GENERAL CONCLUSION ... 126

General Summary ... 126

Limitations ... 130

Directions for future research ... 132

Conclusion ... 133

General References... 136

LIST OF TABLES

SECTION 2: FROM PTSD TO POSTTRAUMATIC GROWTH: TRANSITIONAL

PROCESSES ASSOCIATED WITH THE CANCER EXPERIENCE ... 33

Table 1: ... 68

SECTION 3: SYMPTOMS OF PTSD IN YOUNG MALES RECENTLY DIAGNOSED WITH CANCER ... 69

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of sample ... ... 111

Table 2: Previous exposure to traumatic events ... 112

Table 3: PTSD symptom severity frequencies per group ... ... 112

Table

4:

Summary of intercorrelations between scales for the cancer and control groups ... 113Table 5: Characteristics of drop-outs vs. completed sample ... ... 118

LIST OF FIGURES

SECTION 3: SYMPTOMS OF PTSD IN YOUNG MALES RECENTLY DIAGNOSED

WITH CANCER ... 69

Figure 1: lES scores for the final sample per group through time ... 114

Figure 2: Percentage of elevated PTSD symptoms on the lES for the final sample per group through time ... 114

Figure 3: PCL-C scores for the final sample per group through time ... 114

Figure 4: Percentage of e1evated PTSD symptoms on the PCL-C for the final sample per group through time ... 115

Figure 5: Depression scores for the final sample per group through time ... 115

Figure 6: Anxiety scores for the final sample per group through time ... 115

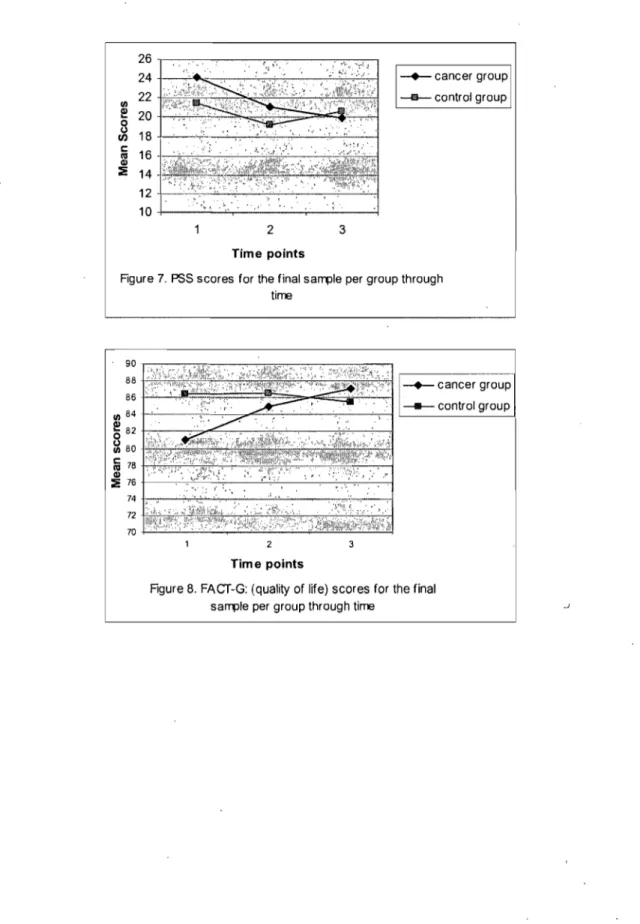

Figure 7: PSS scores for the final sample per group through time ... 116

Figure 8: FACT-G (quality oflife) scores for the final sample per group through· time ... 116

Figure 1-A: lES scores for the cross-sectional samp1e per group through time ... 123

Figure 2-A: Percentage of elevated PTSD symptoms on the lES for the cross-' sectional sample per group through time ... 123

Figure 3-A: scores for the cross-sectional sample per group through time ... 123

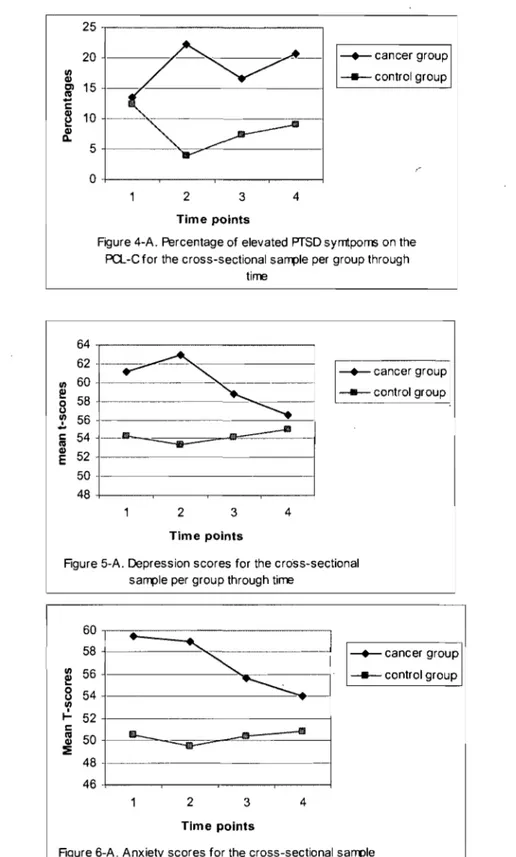

Figure 4-A: Percentage of elevated PTSD symptoms on the lES for the cross-sectional sample per group through time ... 124

Figure 5-A: Depression scores for the cross-sectional sample per group through time ... 124

Figure 6-A: Anxiety scores for the cross-sectional sample per group through time ... ;.124

Figure 7-A: PSS scores for the cross-sectional sample per group through time ... 125

Figure 8-A: FACT-G (quality oflife) scores for the cross-sectional sample per group through time ... 125

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ANCOVA: Analysis of covariance ANOVA: Analysis ofvariance

CCS/NCIC: Canadian Cancer Society/National Cancer Institute of Canada

DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual- 4th edition

FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-G lES: Impact of Event Scale

HD: Hodgkin's Disease LC: Lymphatic Cancer

NHD: Non Hodgkin's Disease

PCL-C: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian PSS: Perceived Stress Scale

PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder SCL-90: Symptoms Checklist-90

SCT: Social-~ognitive transition model of adjustment

SRRS: Social Readjustment Rating Scale TC: Testicular Cancer

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

1 share authorship of the manuscript entitled "From PTSD to posttraumatic growth: Transitional processes associated with the cancer experience" with my thesis supervisor Dr. Zeev Rosberger and with my co-supervisor Dr. Marie Achille. The original idea of for the study was mine and the study was conceptualized by me and Ors. Rosberger and Achille. The data collection was performed by Dr. Rosberger, Dr. Achille, myself and research assistants. The literature review, the choice oftheoretical framework, the choice of the specific qualitative analyses and content analyses of qualitative verbatim were performed by me. The manuscript was written by me with contributions from Ors. Rosberger and Achille.

1 sharè authorship of the manuscript entitled "Symptoms of PTSD in young males recently diagnosed with cancer" with my thesis supervisor Dr. Zeev Rosberger and with my co-supervisor Dr. Marie Achille. The original idea for the study was mine and the study was conceptualized by me and Ors. Rosberger and Achille. The data collection was performed by a research coordinator and myself. The literature review and choice of theoretical,framework was performed by me. The statistical data analysis was completed by me with guidance provided by Dr. Brett Thombs. The manuscript was written by me with contributions from Ors. Rosberger and Achille.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, 1 would like to thank my research supervisor and « patron» Dr. Zeev Rosberger for his ongoing guidance and support, financially, emotionally and academically. Dr. Rosberger presented me with many opportunities for which 1 am most grateful. His availability to discuss work and other topics with his student is exemplary and 1 found myselfvery fortunate to be under his wing. Special thanks to Dr. Marie Achille, my co-supervisor who read my work and helped improve its overall quality. Dr. Achille has also aided me by providing publishing opportunities and much scientific collaboration.

1 cannot graduate from my Ph.D. without giving my heartfelt gratitude to my friends and family, but especially to my father Yves Labrecque. Dad you have played a decisive role in my capability to persevere through my studies. 1 thank you for your listening ear, 1 thank you for being there, and most of aIl 1 thank you for letting me know that no

diploma or title would ever change your love for me.

Thank you to Andrea Feldstain and Vanessa Delisle for their help in proof-reading the final draft. Thank you to Dr. Brett Thombs for his help in answering statistical questions.

1 would like to give thanks to the funding agencies that have provided the financial support without which the completion of my doctoral degree would have been

impossible. This study was funded by a Research Studentship Award to the first author from the National Cancer Institute of Canada with funds from the Canadian Cancer Society CCS Research Studentship Award #016655 and by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research: Grant # HGG-62294 -Male Mediated Developmental Toxicity:

Chemotherapy, Sperm Chromatin, Psychosocial and Progeny Outcomes held by Bernard Robaire, (PI), Z. Rosberger and P.Chan co-PI's, and by M. Achille, co-Investigator. 1 would also like to acknowledge the FRSQ- Réseau de Rercherche Bucco-Dentaire for

funding in the form of a salary subvention accorded to thesis director for Roxane

Robitaille. Special thanks are also given to the psychology department of the University of Montreal for providing monetary awards for the year 2003-2004 and 2004-2005. Thanks to the Jean-Paul Daunais Fund for an award granted in the year 2004-2005. Thanks to the Faculté des Études Supérieures of the University of Montreal for an end of doctoral studies grant awarded in 2008.

SECTION 1: GENERAL INTRODUCTION

The objectives of this project are to explore the cancer-related syrnptoms of PTSD and distress (depression and anxiety) both retrospectively and prospectively; determine the frequency, evolution and risk factors for PTSD syrnptoms in young male cancer patients in the first year following a cancer diagnosis; and in addition to examine their experience of coping and posttraumatic growth.

Approximately 40% of Canadian women and 45% of Canadian men will be diagnosed with cancer at sorne point in their lifetime and 1 out of every 4 Canadians will die from cancer (Canadian Cancer Society /National Cancer Institute of Canada [CCS/NCIC], 2008). In 2008, nearly 30% ofnew cancer diagnoses (50 000 cases) and 18% of cancer-related deaths (13 000 cases) will occur between the ages of20 and 59 (CCS/NCIC, 2008). Hence, there is a growing concem to understand the psychological adjustment of younger cancer patients. Cancers such as testicular (TC), Hodgkin's (HD) and non-Hodgkin's (NHD) lyrnphoma largely occur in young men in the most productive developmental stage of their life (i.e. raising children, building conjugal relationships, employrnent etc.). In Canada, there will be an estimated 3800 new cases ofNHD, 480 new cases of HD and 890 new cases of TC in 2008 in males of aIl ages (CCS/NCIC, 2008). The low incidence rates ofNHD, HD and TC add to the difficulties of studying psychosocial adjustment in this population.

Testicular Cancer

Testicular cancers are almost always germ cell (reproductive ceIl) tumors. There are two types of TC, seminoma and nonseminoma (CCS/NCIC, 2008; Gilligan, 2007). TC is the most common malignancy in men ages 15 to 45 and accounts for almost 25% of aIl

al., 2002). The highest rate of five-year relative survival in Canada is for TC (96%), however incidence rates of this malignancy have been increasing (CCSINCIC, 2008). The risk factors of TC are poorly understood (CCSINCIC, 2008). Cryptorcliidism (delay in the descent oftesticles), abnormal development of the testicle, pers on al or family history of TC, age (particularly between 15 and 49) and infertility (CCSINCIC, 2008;

Gilligan 2007) are sorne of the possible causes of TC.

TC is most often discovered by the patients themselves as such tumors grow rapidly and are easily palpated. Early detection by regular testicular self-examination may curb disease severity (Gilligan, 2007; Moul, 2007; Simon, 2005). The most common early symptoms for TC are: a lump on the testicle that is almost always painless, feeling of heaviness or dragging in the lower abdomen or scrotum, a dull ache in the lower abdomen and groin (CCSINCIC, 2008). Unfortunately, TC symptoms may be

confounded as resulting from an infection and treated ineffectively with antibiotics which may allow the tumor to growfor an added period oftime.

Treatment typically includes one or more of the following: radiation, combination chemotherapy (carboplatin, blenoxane, etoposide and cisplatin) and surgery

(orchiodectomy and retroperitoneallymph node dissection). Radical orchiectomy (surgical removal of the affected testicle) is a standard procedure of the diagnosis work-up (CCSINCIC, 2008; Gilligan, 2007). With one healthy testicle, patients are still able to

have erections and ejaculations, and may still be able to father children. In about 2 to 3%

of cases, the second testicle will also develop a malignancy (Gilligan, 2007). In such

cases, both testicles are removed and patients are infertile and experience orgasms as dry

-

-ejaculations. Before undergoing any systematic or invasive procedure, patients are urged to make use of sperm banking because of the potential for temporary or permanent

infertility following cancer treatments. There are several cancer-related causes of infertility: the systemic effects of the disease itself (for both testicular and lymphatic cancers), the surgi cal procedures (non-nerve sparing retroperitoneallymph node dissection, resection ofresidual node masses, removal of testes), and gonadotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Hartmann Albrecht, Schmoll, Kuczyk,

Kollmannsberger, & Bokemeyer, 1999; Howell & Shalet, 2002; Naysmith, Blake,

Harvey, & Johnson, 1998; Schrader,Heicappell, Muller, Straub, & Miller, 2001; TaI,

Botchan, Hauser, Yogev, Paz, & Yavetz, 2000). Male cancer patients usually recover

spermatogenesis between two to four years post-completion of cytotoxic cancer therapy, but it is currently impossible to predict the likelihood, extent and timing of fertility recovery, and up to 30% of patients may never recover (Colpi, Contalbi, Nerva, Sagone,

& Piediferro, 2004; Giwercman & Petersen, 2000).

The spectrum of treatment related late-effects ranges from minor complications to permanent and occasionally lethal sequelae (i.e. cardiac complications, the occurrence of

a second malignancy, infertility) (Aziz & Rowland, 2003; Gilligan, 2007). After surgery,

pain, nausea, and lack of appetite may be experienced. Radiation side-effects are usually mi Id and include fatigue, irritation or tendemess of the skin where the treatment was given. The side-effects will usually disappear when the treatment period is over and the normal cells repair themselves. TC responds weIl to chemotherapy. The treatment is outpatient for most patients and may last from six to ten months (Gilligan, 2007). Although healthy cells can recover over time, patients may experience side-effects from treatment like nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, fatigue, hair loss and an increased risk of infection. High doses of chemotherapy may also kill normal blood-forming cells in the marrow. Blood transfusions or "blood cell growth factors" to increase red cells may be

needed: To improve white ceIl count the amount of chemotherapy drugs may be reduced, time between treatments may be increased and growth factors to increase neutrophils may be given. A neutrophil is a type of white ceIl that fights infection in the body. Bone man'ow transplantation (stem ceIl transplant) is a newer treatment option that uses a patient's own stem ceIls (autologous infusion) or donated stem ç:eIls (aIlogeneic transplant) to restore blood and immune cell formation after intense chemotherapy or radiation therapy (CCSINCIC, 2008).

Lymphatic cancers

Lymphomas are a group ofblood cancers that start in the lymphatic system.

Lymphoma starts with a change to a type of white blood ceIl caIled a lymphocyte. The change of the lymphocyte causes it to become a lymphoma cell. The two most prevalent types oflymphoma are HD and NHD. Approximately 15 percent of people with

lymphoma have HD; others have one ofmany different subtypes ofNHD (CCSINCIC, 2008). The 5-year survival rate for males with lymphoma is over 80% (Raemarkers et al., 2002) but NHD generaIly has a worse prognosis (Jemal et al. 2004). NHD is currently

the 5th most common type of cancer across aIl age groups in Canada (CCSINCIC, 2008),

and the second most prevalent type of cancer in 20. to 44 years of age (CCSINCIC, 2002). Fortunately, since 2000, mortality rates in males have shown a statisticaIly significant decline of 2.3% per year (CCSINCIC, 2008).

The risk factors and causes of HD and NHD are also poorly understood and in many cases patients do not show any identifiable risk factors. Infections with the Epstein-Barr virus, the hum an T -ceIl lymphocytotropic virus (HTL V), or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), family history, and age (particularly between 15 and 35 and after 60)

increase the probability of developing HD (Leukemia and Lyrnphoma Society, 2008). Exposure to pesticides, dioxins and herbicides may also increase the risk ofNHD

(CCSINCIC, 2008). Usually the first syrnptom ofHD or NI:ID lyrnphoma is swelling of lyrnph nodes in the neck, arrnpit, chest, groin, or near the ears or elbows. The enlarged lyrnph nodes are usually painless. Other signs and syrnptoms ofHD are weight loss, night

sweats, unexplained fever, feeling tired, lack of energy, and itchy skin (CCSINCIC, 2008;

Leukemia and Lyrnphoma Society [LLS], 2008).

Treatment options for lyrnphomas are chemotherapy, radiation therapy, biological therapy (sometimes called immunotherapy), bone marrow transplant, and peripheral stern

cell transplant (LLS, 2008; Theodossiou & Scharzenberger, 2002). Watchful waiting may

be recommended in slow growing NHD to avoid side-effects oftreatment until it is needed. Lyrnphomas make it harder for the body's immune system to fight off infections, and chemotherapy and radiation can create complications. A patient who has high-dose chemotherapy may need a stern cell transplant to strengthen the immune system. Sorne common side-effects from treatment for HD and NHD are: mouth sores, nausea,

vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, bladder irritation, b100d in the urine, extreme tiredness, fever, cough, rash, haïr loss, weakness, tingling sensation, and lung, heart or nerve problems. Fertility may also be compromised temporarily or perrnanently (CCSINCIC, 2008; LLS, 2008).

Psychological distress is a recognized side-effect of cancer. According to the c1inical Practice Guidelines in Oncology issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2005, p.1) distress is:

A multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (cognitive, )

behavioràl, emotional), social, and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms and its treatment. Distress extends along a continuum, ranging from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness and fears, to problems that can become disabling, su ch as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and existential and spiritual crisis. On average, 35% of patients suffer from elevated levels of di stress at sorne point

during their cancer expenence (Zabora, BrintzenhofeSzoc, Curbow, Hooker, &

Piantadosi, 2001). The literature generally suggests that breast cancer patients experience

significant levels of depression and anxiety (Amir & Ramati, 2002; Andrykowski,

Cordova, Studts, & Miller, 1998; Deimling, Kahana, Bowman, & Schaefer, 2002;

Epping-Jordan et al., 1999), but sorne studies suggest otherwise (see: Stiegelis, Hagedoom, Sanderman, Van der Zee, Buunk, Van der Bergh, 2003).

Cancer-related PTSD 1

In recent years, researchers became interested in a specifie type of distress following

cancer diagnosis: posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For the first time in the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatrie

Association [APA], 1994) there is recognition that life-threatening illnesses, such as cancer, could be of sufficient magnitude to meet the criteria of a traumatic stressor. One of the peculiarities ofPTSD is that it is the only DSM-IV (APA, 1994) diagnosis for which diagnostic criteria inc1udes both etiological and phenomenological aspects of the

illness (Davidson & Foa, 1991). Indeed, PTSD's criterion A qualifies the mandatory stressful event and appraisals leading to symptoms of the disorder. In DSM-IV, criterion A is formulated as follows:

The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which both of the following were present:

1) The person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others

2) The person 's response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror

The diagnosis ofPTSD as it currently stands in the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) requires: 1) the identification of a catastrophic event; 2) the individual' s appraisal of the catastrophic event; 3) and the presence of several symptoms directly associated with the initial catastrophic event (e.g., nightmares that occur as part of the disorder are nightmares about the actual event). The list of specific symptoms for PTSD diagnosis remains heterogeneous and requires the presence of symptoms in each of the three major c1usters and inc1udes a total of 17 symptoms (DSM-IV, 1994). To receive a diagnosis ofPTSD one must have at least one symptom ofreexperiencing (intrusions) (i.e.: persistent and uncontrollable thoughts about the event, recurrent dreams about the event, physiological and emotional arousal upon cues resembling the event etc.) (Criterion B), three symptoms of avoidance and numbing (i.e. efforts to avoid thoughts, feeÜngs, conversations, places, and activities associated with the event, incapacity to recall important aspects of the

event, restricted range of affect etc.) (Criterion C), anÔ two symptoms ofhyperarousal

(i.e. irritability, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response etc.) (Criterion D). As such, a person with 13 symptoms may not meet the specific criteria for PTSD and two

individuals with PTSD may have no common symptoms. While severe stressful experiences lead to high rates of diagnosable PTSD, trauma survivors without the full disorder can also experience high symptomatic levels of subdiagnostic distress

(McMillen, North, & Smith, 2000). In fact, sorne researchers in the field of PTSD have

argued that the stringency of the avoidance and numbing criterion (Criterion C) contributes to the low incidence rates of the disorder in sorne studies (McMillen et al., 2000; Norris, 1992). Criterion C requires a higher number ofreported symptoms (three) than the other criteria, and the symptoms in the cluster are sorne of the rarest (i.e. numbing, amnesia) (McMillen et al., 2000; Norris, 1992). In a sample of hurricane victims, 83% met criterion B, 42% met criterion D but only 6% met criterion C, hence only 5% met the full criteria for PTSD (Norris, 1992). In a sample of earthquake

survivors, 13% met the full criteria for PTSD, but when Criterion C was reduced from 3 to 2 symptoms, 26% met the full criteria for PTSD (McMillen et al., 2000).

Because the triggering event plays such a central role in the onset of PTSD, one may put forth the hypothesis that different triggering events may result in different profiles of PTSD. For example, the intrusions experienced by patients diagnosed with a

life-threatening illness may be more future-oriented than focused on the past (Kangas, Henry,

& Bryant, 2002; Mundy & Baum, 2004). After the initial shock of a diagnosis of cancer, for example, patients have many threats and potentiallosses to anticipate. The

apprehension of su ch events may intrude more consistently than intrusions regarding the time of the initial shock (Brennan, 2001).

To verify if the breast cancer experience qualified as a traumatic stressor, Cordova et al. (2001) asked patients if the y perceived being diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer as a threat of death or serious injury or as a serious threat to their physical

integrity, and iftheir response ever involved intense fear or helplessness. There were 61 % of participants who rated breast cancer as a traurnatic stressor. They perceived this event as a threat to life or to physical integrity in 80% of the cases and responses ' involved fear, helplessness or hOITor in 64% of survivors.

A review by Kangas et al. (2002) of studies with breast, prostate, neck, gastro-\

intestinal cancers and Hodgkin's disease patients and studies with heterogeneous sarnples have shown incidence rates of PTSD varying between 1.9% to 35.1 %. This variability in findings is due in part to the different assessrnent tools used by researchers, by the

diversity of populations sarnpled, and by the tirne elapsed between diagnosis and the tirne of data collection (Kangas et al. 2002). Even years after rernission, survivors rnay still present with PTSD symptorns. A study ofbreast cancer patients by Alter et al. (1996) found that five years post-treatrnent4% ofwornen had CUITent PTSD, and 22% had lifetirne PTSD (a clinicallevel ofPTSD symptorns at any tirne after the traurnatic event) related to cancer. Other investigations suggest that the prevalence of cancer-related PTSD symptorns rnay be ev en higher. In a sarnple ofbreast cancer survivors, 52% of the sarnple

1

scored in the high range ofPTSD symptorns on the Impact of Event Scale (lES) (Butler,

Kooprnan, Classen, & Spiegel, 1999). Unfortunately, rnost studies ofPTSD following

cancer have been cross-sectional, and rnany questions rernain conceming the applicability ofPTSD to cancer as a stressful event. Across the cancer trajectory, which includes rnany potential threats and losses, it has not been weIl established wh ether PTSD symptorns are rnost present early post-diagnosis or in the post-treatrnent phase. However, one study identified the diagnosis itself as the principal stressor of the cancer experience in a cross-sectional study with breast cancer patients (Andrykowski et al., 1998). Sorne studies have concluded that tirne since treatrnent is inversely related to PTSD symptorns (Alter et al.

1996; Fleer et al. in press; Kangas, Henry Bryant, 2005a). These studies provide important clues as to the possible course of PTSD symptoms over time.

In a series of papers drawnfrom a single prospective study (Kangas, Henry Bryant,

2005a, 2005b, 2005c, 2005d), there was significant decline in PTSD symptoms from diagnosis to 1 year post-diagnosis as measured by the Clinician administered PTSD Scale

(CAPS), and none ofthose that had low Acute stress disorder1 scores at diagnosis

developed PTSD at one year, pointing to the importance of early assessment ofPTSD symptoms following cancer diagnosis (Kangas et al., 2005a). However, this study' also showed that there were significantly more women than men who met the criteria for PTSD at six (47% vs. 13%) and twelve (42% vs. 5%) months (Kangas et al., 2005a, 2005b). Other prospective studies pointed to a decline in PTSD symptoms in general

(Manuel, Roth, Keefe, & Brantley, 1987) or in intrusive thoughts but not in avoidance as

measured by the lES after diagnosis (Epping-Jordan et al. 1999).

A number of studies and authors have noted the extensive burden that PTSD

symptoms pose on individuals (Frueh, Cousins, Hiers, Cavenaugh, Cusack, & Santos,

2002). PTSD symptoms are associated with a reduction in immune response, namely in women with breast cancer (Andersen et al., 1998), an increase in somatic complaints and

health problems (Escobar, Canino, Rubio-Stipec, & Bravo, 1992), more emotional

disturbance, more pain, and rendering pain resistant to treatments (Aghabeigi, Feinmann,

& Harris, 1992). The rate ofhealth service utilization in people with PTSD (38%) is comparable to that found in people suffering from major depression, but higher than that of people with other anxiety disorders (23%) or with substance use disorder (23%)

1 Acute Stress Disorder is a diagnosis that applies to individuals having been exposed to a traumatic event and who exhibit symptoms for a period of two da ys to four weeks following the event A PTSD diagnosis cannot be given to patients until they have exhibited symptoms of the disorder for at least one month,

(Kessler, 2000). Topical neurological research demonstrated a significant reduction in gray matter volume in the right orbitofrontal cortex (which is thought to be involved in the extinction of fear conditioning and the retrieval of emotional memory) of breast cancer survivors with PTSD compared to those without PTSD and compared to healthy subjects both at baseline and foIlow-up investigations (Hakamata et al. 2007). PTSD is

highly comorbid with depression and anxiety (Amir & Ramati, 2002; Deimling et al.,

2002; Edgar, Rosberger, Nowlis, 1992; Epping-Jordan et al. 1999) and the vast majority of those who are diagnosed with PTSD will' also experience higher risks of suicide, alcohol and/or drug abuse, as weIl as other types of distress (Haber et al., 2002; Kessler,

Borges, & Walter, 1999). Despite these facts, trauma tends to go unrecognized in most

outpatient clinics (Frueh et al. 2002).

There are important reasons for studying PTSD, anxiety and depression jointly. PTSD accompanied by depression may have a different prognosis and require different

interventions. In a commentary on the complex relationship between PTSD and

depression, Neria & Bromet (2000) offered four possible associations: 1) depression can

be a risk factor for PTSD; 2) depression can be a consequence of exposure to traumatic events; 3) it can co-occur with PTSD; and 4) it may appear following PTSD. Distress symptoms (such as depression and anxiety) following traumatic exposure often share the same risk factors as PTSD and research has shown that the incidence of PTSD increases

the risk for first time major depression (Breslau, Davis, Peterson, & Schultz, 2000).

Furthermore, the overlap in quantitative measure of depression, anxiety and PTSD produce quantitatively high collinearity. The relationship among these variables must be examined concurrently to ensure further understanding ofthese interactions.

Risk factors for PTSD

There is a paucity of research addressing the particular psychosocial needs of male cancer survivors. Most research in psychosocial oncology has been do ne in samples of breast cancer patients or in mixed-gender samples, without clear comparisons between

male and female samples (Andrykowsky, Brady, & Hunt, 1993; Kangas et al., 2005a,

2005b; Stiegelis et al. 2003). However, women are twice as likely as 'men to develop PTSD in their lifetimes (10.4% vs 5%) even though men have a broadly higher risk of

being exposed to traumatic events in their lifetime (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes &

Nelson, 1995). There are 60.7% ofmen and 51.2% ofwomen who reported at least one traumatic event in their lives (Kessler et al. 1995). Yet, the higher risk of PTSD in women is one of the most consistent finding in the epidemiology of posttraumatic stress

disorder (Olff, Langeland, Draijer, & Gersons, 2007).

Particular risk factors of cancer-related PTSD are princip aIl y linked to two of the major symptom clusters ofPTSD: intrusions and avoidance. Most studies have used the Impact of Events Scale (lES) (Horowitz, 1979) as a proxy for PTSD. This questionnaire assesses only intrusive and avoidant symptoms. Lower age is related to increased

symptoms of intrusions and avoidance in long-term breast cancer survivors (Butler et al., 1999), as weIl as newly diagnosed breast cancer patients (Epping-Jordan et al. 1999). Other variables such as lower education (Cordova, Andrykowski, Kenady, McGrath,

Sloan, & Redd, 1995; Epping-Jordan et al. 1995) and lower income (Cordova et al. 1995)

are also associated with an increased presence ofPTSD symptoms in breast cancer patients. In a study of TC survivors (Fleer et al. in press), high scores on the lES were associated with being younger, single, unemployed, and treated more recently. There is no evidence of a relation between disease stage, or total number of treatments received

and subsequent PTSD (Cordova et al. 2001; Kangas et al, 2002; Kangas et al. 2005a, 2005b).

Cognitive Processing and Posttraumatic Growth

Highly stressful events may overwhelm survivors (Brennan, 2001). Thus, avoidance may be part of the normal adaptive process that preserve a coherent mental model of the world, while defending against threatening and painful information that cannotbe easily integrated into the assumptive world (Brennan, 2001). However, while avoidance may be an adaptive short-term mechanism it may become counter-productive ifit goes on for too long as it prevents adequate cognitive processing (Brennan, 2001; McMillen et al., 2000,

Foa, Stekee, Rothbaum, 1989; SuIs & Fletcher, 1985).

A theme that runs across cognitive theories of healthy adaptation to extremely stressful events is that adjustment stems out of the repeated confrontation with the memories of the trauma (Brennan, 2001; Creamer, Burgess, Patti son, 1990, 1992; Greenberg, 1995). Positive appraisals and reappraisals of a traumatic event may protect against developing PTSD (Olff et al., 2007). They have been linked to faster cortisol habituation to subsequent stressors, indicating a greater flexibility in the system (Epel,

McEwen, & Ickovics, 1998). Thus avoidance, more than intrusions may lead to increased

di stress by preventi~g the direct confrontation and cognitive processing of the stressful

memories (Creamer et al., 1992). The importance of avoidance and numbing symptoms in predicting the development of psychopathology is also reflected in the importance given to Criterion C in the DSM-IV.

While the thoughts and memories associated with the stressful event are cognitively processed, they may be replaced by other adaptive schemas, which produce posttraumatic growth. There is a growing body of research suggesting that 60% to 90% of cancer

survivors experience posttraumatic growth (Collins, Taylor, & Skolan, 1990). Posttraumatic growth results wh en individuals having faced life crises experience a positive outcome (Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004). Growth may manifest itself across a vàriety of domains, su ch as having an increased gratitude for life, feeling like a stronger person, valuing deeper interpersonal relationships, developing a more meaningful

spirituality, or experiencing a richer existence (Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004). In past years

posttraumatic growth following exposure to extreme events has been frequently reported

and researchers have given many formulations to this phenomenon. It can be viewed as

positive illusions (Taylor & Armor, 1996), as a coping process (Aldwin, 1994), as a form

of meaning-making (Park & Folkman, 1997), and as benefit finding (Affleck & Tennen,

1996). Posttraurriatic growth may be a form of coping, an outcome on its own or both (Cordova, 2001).

Posttraumatic growth occurs because events have forced an individual to revisit the long-held assumptions and beliefs about the self, others. and the world. lndividuals develop and rely on a general set ofbeliefs and assumptions about the world that guide their actions, and help them to understand the causes of events. This can provide them

with a general sense ofmeaning and purpose (Janoff~Bulman, 1992). This is also

consistent with Taylor's theory of cognitive adaptation to threatening events that predicts that cancer patients would attempt to cbnstrue personal benefit from their experience in an effort to protect self-esteem (Taylor, 1983). Wh en individuals are faced with

threatening events, they are motivated to derive meaning from their experience as weIl as to maintain or enhance self-esteem in the face of any negative sequelae associated with the event (Taylor, 1983). This theory predicts that cancer patients would attempt;to

1983). Psychosocial transitions and growth are also consistent with existential theory: being confronted with one's mortality may elicit a reevaluation and redefinition oflife goals and priorities, such that individuals emerge with a greater investment in and appreciation of life, interpersonal relationships, and spirituality and personal resources (Cordova et al, 2001).

Traumatic events may cause a discontinuity in identity because it is being seriously

chalIenged by the extreme experience (Little, Paul, Jordens, & Sayers, 2002). Traumatic

events shatter people's basic assuinptions about the world; they overwhelm usual coping methods that give people a sense of control, connection and meaning (Herman, 1992). This forces sufferers to reorganize their world view and to search for new meanings. PTSD distorts the normal appraisal process: people with the disorder see the world differently. There is difficulty in discriminating danger cues from safety cues as a consequence of , exposure to a significant stressor that is both unpredictable and uncontrolIable (Friedman,

1997). The narrative of trauma includes a notion of trauma as a turning point: th en the

world is expericnced as before and after the trauma (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Identity

also includes future memories of the self, which involve the imagination of events that have yet to occur, they are the expectations we create for ourselves and form continuity within our lives (Little et al. 2002). For example, a young male who is a medical student has formed a future vision ofhimself as being a successful physician, a future husband to his girlfriend and a future father. AlI ofthese narrative identities are threatened by the cancer

diagnosis. Growth, however, do es not occur as a direct result of trauma. It is the

individual's struggle with the new reality in the aftermath of trauma that is crucial in determining the posttraumatic growth. Cognitive rebuilding takes into account the changed

reality of one's life after the trauma and produces schemas that incorporate the trauma. It is

a consequence of attempts at survival (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

Rationale and Purpose

This project is part of a larger study examining the clinical, biological, psychosocial impact of disease and chemotherapy treatment effects (including those on reproductive functioning) in men treated for testicular or lymphatic cancer and provides a unique opportunity to study both retrospective and longitudinal subjective experiences of the particular risk factors, correlates and incidence of PTSD in young male cancer patients. The present study is taking place within the psychosocial arm, of this larger study, and is composed of two parts. In study l, retrospective accounts of the cancer experience are gathered from semi-structured interviews with a group oflong-term survivors. In study 2, a longitudinal quantitative investigation ofnewly diagnosed testicular or lymphatic cancer patients looks at the frequency, course ànd risk factors of PTSD symptoms.

The main purpose of study 1 is to gather qualitative descriptions oftraumatic symptoms and identify recurrent themes in a sample of cancer survivors regarding

specific aspects of their cancer experience. Particularly, the transition and transformations of cancer-related PTSD symptoms through time (diagnosis, treatment and long-term survivorship) are explored. The appraisal of the cancer experience at diagnosis, treatment and long-term survivorship phases are described with the goal of verifying if and what aspects of cancer are appraised as traumatic. AIso, the study describes carefully how shared manifestations of different disorders are more closely related to a specific disorder (i.e. anxiety) than another (i.e. PTSD) at different time points. The final goal of study 1 is to understand the seemingly contradictory reports of distress and posttraumatic growth and to bring these findings coherently within the available theoretical models of

adjustment. It is hypothesized that qualitative accounts from survivors will reveal

experiences of psychological turmoil. We also expect that patients will move dynamically from di stress to posttraumatic growth and that appraisals and reappraisals about cancer will play a key role in this transition. This part of the study will facilitate the generation ofhypotheses regarding the development ofPTSD following cancer diagnosis.

Qualitative research attempts to provide an understanding of the experiences, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of social actors as they live through a situation (Elliot,

Fischer, & Rennie, 1999). In data gathering and analysis, the qualitative researcher

attempts to reflect the understanding of the participants, staying close to the perspective and meaning that the interviewee has provided. While it cannot provide causal

explanations of phenomena, qualitative research can enrich understanding by providing a theory on observed data and by providing meaningful answers to questions under study (Elliot et al., 1999). Previous studies using qualitative methods have examined the experience of male cancer survivors to develop an understanding of the important

domains of the experience. In a study of sexual clysfunctions in men following testicular

cancer, qualitative analysisgenerated results not otherwise found with the use of

quantitative self-reported questionnaires (Sheppard and Wylie, 2001). This approach has allowed the uncovering of marked variability in the expression of emotional reactions and psychological effects of infertility within a small sample of young male cancer survivors (Green, Galvin, Home, 2003). While PTSD has yet to be studied in this population, a qualitative investi'gation of the experience of testicular cancer survivors ai least 3 years post-treatment revealed themes of disbelief and despair, guarded optimism, "feeling under siege" and experiences of physical and emotional challenges (Brodsky, 1999).

Qualitative studies are particularly weIl suited for the investigation of poorly understood phenomena; by generating themes and hypotheses related to study questions.

The purpose of study 2 is to examine PTSD symptoms in testicular and lymphatic cancer patients and try to establish a timeline for the emergence of PTSD symptoms in the first year following cancer diagnosis (time 1: diagnosis, time 2: 3 months post-diagnosis, time 3: 6 months post-diagnosis and time 4: 12 months post-diagnosis). Study 2 aims at identifying the frequency, risk factors, and course of PTSD symptoms.

Psychological morbidity will be assessed to gain an understanding of the relationship between PTSD, depression and anxiety in this group. It is hypothesized that: a) incidence rates ofPTSD symptoms will be higher at all time points in cancer patients than in a group ofhealthy controls from the community, b) levels ofPTSD at a previous

measuring time will highly predict CUITent levels ofPTSD, c) the highest level ofPTSD symptoms in patients will be at the time ofdiagnosis and will steadily decrease through time, d) younger age, prior history of trauma, lower education level and lower

socioeconomic status will increase the likelihood ofPTSD symptoms, and e) PTSD will be highly correlated to depression and anxiety.

SECTION 2: FROM PTSD TO POSTTRAUMATIC GROWTH: TRANSITIONAL PROCESSES ASSOCIATED WITH THE CANCER EXPERIENCE

Roxane Robitaillea,c., Zeev Rosbergera,b,c, Marie Achillea

aDepartment ofPsychology, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada b Psychosocial Oncology Program, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada .

cInstitute of Community and Family Psychiatry, 5MBD-J ewish General Hospital, . 4333 Cote-Ste Catherine, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, H3T 1 E2

Abstract

A cancer diagnosis can he a highly distressing experience, yet sorne survivors also experience positive psychosocial outcomes. This study explores the transitional processes and development of PTSD symptoms, appraisals, distress, coping and posttraumatic growth over time. Verhatim accounts of 22 survivors of either testicular or lymphatic cancer were gathered retrospectively. Qualitative data was analyzed according to the Miles and Huherman (1984) approach. Diagnosis was appraised as a shock and threat, and anxious anticipation and denial were common. In the treatment phase, despair and discouragement were most common. In the long-term, PTSD symptoms and delayed emotional reactions were reported. Optimism was common in terms of early coping and many reported posttraumatic growth in the long-term survival phase. Findings are consistent with the Social-Cognitive Transition model of Adjustment. Conclusion: While di stress is present throughout the cancer experience, sorne survivors revisit their existing life assumptions and experience differing levels ofposttraumatic growth.

Introduction

Testicular cancer (TC) and Lymphatic cancer (LC) (Hodgkin's (HD) and Non-Hodgkin's disease (NHD)) are currently the two most common types of cancer in men 45 years of age or younger (Canadian Cancer StatisticslNational Cancer Institute of Canada, 2002,

. Trask, Paterson, Fardig, & Smith, 2003). Fortunately, due to recent medical and

technological breakthroughs, the 5-year survival rate for testicular cancer is 90-95%. 1

(Fossa & Dahl, 2002; Kaasa, Aass, Mastekaasa, Lund, & Fossa, 1991) and for

1

lymphomas this rate is over 80% (Raemarkers et al., 2002) but NHD generally has a worse prognosis (Jemal et al. 2004). As both incidence rates and rates of survival increase, more men will become long-term survivors of these cancers. Both cancers are treated with similar chemotherapy regimens, with similar side-effect profiles, inc1uding potential infertility, and both show excellent prognosis. Also, psychosocial outcomes are similar in these two cancer populations (Bloom et al., 1993). The cancer experience is an ongoing event associated with several potential threats and losses. The trajectory

experience involves multiple stages as the patient passes through the possible threats of diagnosis, surgery, drug treatments, side-effects, and the survival and recovery period. Following a traumatic event it is common that an acute stress response emerges and may evolve into a chronic state of emotional dysregulation, but, for most, these symptoms will resolve. However, we lack an understanding of the developmental timeline of these symptoms and ofthe factors that lead to a timely retum to homeostasis following such potentially traumatic events.

Unlike previous editions, the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 4th Edition, 1994) recognizes that the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness, such as cancer, can be of sufficient magnitude to meet the criteria of a traumatic stressor. Presumably the

)

traumatic eventin relation to cancer is the diagnosis itself. Apart from being exposed to a seriously stressful event, the person's subjective response to this event must have included intense fear, helplessness, or horror in order to qualify for a PTSD diagnosis. It is patients' subjective appraisals of the cancer experience that reveal when and how they perceive cancer as a threat. In PTSD, appraisal implies that an event is a threat, and

a judgment of the seriousness of that threat. It includes giving a meaning to the threat and

an emotional experience. The three symptom clusters necessary for diagnosing PTSD include: a) intrusions: persistent and uncontrollable thoughts about the event, b) avoidance and numbing: efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings, conversations, places, and activities associated'with the event, restricted range of affect, feeling detached from others, diminished interest in significant activities, and c) hypervigilance: increased

arousal, exaggerated startle response, di ffi cult y concentrating.

A review of PTSD in cancer populations revealed a prevalence of PTSD varying

between 1.9% to 35.1 % (Kangas, Henry, & Bryant, 2002). In lymphatic cancer and

testicular cancer survivors these figures are respectively 17% (Black & White, 2005) and

13% (Fleer et al., in press). This variability in findings is due likely to the different assessment tools used by researchers, the diversity of populations sampled, small sample sizes and by the time elapsed between diagnosis or end oftreatment and the time of data collection. A study ofhead and neck cancer patients showed that while a small

percent age ofwomen met the full criteria for PTSD 12 months post-diagnosis (14%),

(

these were the same patients who had met criteria at 6 months post-diagnosis (Kangas,

Henry, & Bryant, 2005). There were no new cases ofPTSD at 12 months (Kangas et al.,

to investigate early PTSD manifestations in order to uncoverfactors that lead to unremitting (chronic) forms of the disorder over time.

General distress is a common side-effect of cancer. In the case ofHodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients, elevated distress was present in 37.8% and 36.6%

respectively, placing these cancers as the 3rd and 5th most distressing types of cancer after

1ung, brai n, and pancreatic cancers (Zabora, BrintzenhofeSzoc, Cm:bow, Hooker, &

Piantadosi, 2001). While Zabora et al. (2001) did not provide similar norms for testis cancer patients, Bloom et al. (1993) found no significant differences on psycho10gical outcomes and distress in a comparative study oftesticular cancer patients and Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. Given that PTSD is highly comorbid with depression, anxiety and

other types of di stress (Amir & Ramati, 2002; Deimling, Kahana, Bowman, & Schaefer,

2002; Edgar, Rosberger, & Nowlis, 1992; Epping-Jordan etaI., 1999), symptoms ofthese

disorders are likely to be elevated in young males with cancer. The overlap between these disorders is huge. When scales of depression, anxiety and PTSD are given, they always correlate highly, and thus can tell us little about the differentiation among these disorders. For example, "markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities" is a symptom frequently observed in major depression; however in PTSD this diminished

interest appears only following the stressful event. To give another illustration, "di ffi cult Y

falling or staying asleep" is a symptom of primary insomnia, generalized anxiety disorder and major depression, to list a few; again in PTSD sleep disturbances are directly

attributable to the initial stressful event. Qualitative investigations are needed to describe the co-occurrence of these disorders and perhaps to clarify when a symptom is a property of one specifie disorder versus another.

Despite the evidence for di stress following cancer, there is a growing body of research that has explored the positive benefits that may result from being confronted with a

traumatic event (Jaffe, 1985; Tedeschi &, Calhoun, 2004). In the are a of psychosocial

oncology, despite the hardship of a cancer diagnosis, sorne survivors experience . posttraumatic growth, su ch as growth in relating to others, spiritual change, and greater

appreciation oflife (Andrykowsky, Brady, & Hunt, 1993; Carver & Antoni, 2004;

Cordova, Cunningham, Carlson, & Andrykowski, 2001). Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004,

p.1) have provided the following definition of posttraumatic growth:

Posttraumatic growth is the experience of positive change that occurs as a result

of the struggle with highly challenging life crises. It is manifested in a variety of

ways, inc1uding an increased appreciation of life in general, more meaningful interpersonal relationships, an increased sense of personal strength, changed priorities, and a richer existential and spirituallife.

Posttraumatic growth is a possible out come of adapting to traumatic events. In contrast to coping mechanisms, posttraumatic growth is an ongoing process that gives sense to the experience. There is a discontinuity in time as life is perceived as before versus after the trauma. The present study retrospectively explores the transition and transformations of cancer-related PTSD symptoms through time (diagnosis, treatment and long-term survivorship) and describes the appraisal of the cancer experience at diagnosis, treatment and long-term survivorship phases with the goal of verifying if and what aspects of cancer are appraised as traumatic. AIso, the study describes how shared manifestations of different disorders are more c10sely related to a specific disorder (i.e. anxiety) than another (i.e. PTSD) at different time points. The final goal ofthis paper is to understand the seemingly contradictory reports of distress and posttraumatic growth

and to bring these findings together coherently within the available theoretical models of adjustment. We expect that patients will move dynamically from di stress to

posttraumatic growth and that appraisals and reappraisals about cancer will play a key part in this transition.

Methods Study Design and procedures

This qualitative study employed semi-structured individual interviews with male cancer survivors. Interviews were approximately 90 minutes and were conducted in English or French by trained interviewers. The team of interviewers was composed of four graduate students in psychology. Verbatim transcription of the interviews was performed by the interviewers and a paid research assistant. Ethics approval was obtained through a university institutional review board prior to the beginning of the study. Written consent was also obtained from each participant. The sample consisted of 22 males, TC (n=12) and LC (Hodgkin's Lymphoman=9; Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma n=l) survivors. Cancer survivors were recruited through referrals from hospitals and private practices in the Montreal area (Canada, Province of Quebec). Patients were identified by physicians from two university hospitals in large urban area and subsequently recruited by a research coordinator once they met eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria in this study were: having received a diagnosis of testicular cancer, Hodgkin's or Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, being at least 1-10 years post completion of treatment, having received chemotherapy as part of their treatment regimen, and being between 18 to 40 years old at time of initial cancer diagnosis. In this study internaI diversification was accompli shed by selecting survivors who were between one to ten years post-completion of cancer treatments and ages 18 to 40 at the time of diagnosis, thus allowing for assessment of di stress and coping at

different stages of survivorship and developmental maturity. InternaI homogeneity of the sample was achieved by selecting only survivors who had undergone gonadotoxic chemotherapy treatments for TC or LC. Patients were recruited until data saturation was reached, in other words until the addition of novel interviews only reiterated information th-at had already been collectedin prior interviews without adding any novel information. Data saturation was reached after 15 interviews. However, we proceeded with recruitment to inc1ude five more Hodgkin's disease survivors and one Non-Hodgkin's disease survivor to increase internaI diversification. Demographic data was gathered prior to the interview.

This project is part of a larger study that explored communication between health care professionals and patients concerning fertility issues, long-term adaptation, as well as the relationship between psychosocial adjustment, informational needs and communication processes surrounding disease and its side-effects in young men diagnosed with testicular or lymphatic cancer and at risk for infertility. These questions were elaborated from the literature, a pilot qualitative study and a consensus among two c1inical psychologists and a urologist/reproductive specialist, all of whom were experienced in psychosocial

oncology research and practice. Also as coding and analysis of interviews evolved, additional questions were inc1uded in the interview guide to validate and explore the new information emerging from the coding. As such, the participant's description oftheir psychological adjustment was incorporated as probes and questions in the interview guide as the project evolved. Interviews consisted of open-ended questions and specific probes regarding four major domains a) the general experience of cancer (i.e.: What was your reaction to the cancer diagnosis?, What was your experience in terms of treatment and side-effects?); b) the communication surrounding fertility related issues (i.e.: When

was i nferti lit y first brought up?); c) the psychological impact of cancer and

chemotherapy induced i nferti lit y and sexual dysfunctions (i.e: Did you avoid the topic of cancer at aIl or avoid reminders ofit? Did you react with intense fear at any point?); and d) patient needs regarding effective communication around fertility issues (i.e.: What would help patients feel more comfortable, better prepared and more efficient in

discussing infertility issues in the future?). The current study was particularly focused on the first and third interview domains, specifically data reflecting PTSD, di stress

(depressed mood and anxiety), posttraumatic growth and coping.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio taped, transcribed verbatim, and imported into N'Vivo 2.0 software. The data was gathered and analysed according to the Miles and Huberman (1984) mixed approach. This approach consists ofthree flows of analysis: data reduction into theme codes, data display into tables, and conclusion drawing and verification. This particular study places itselfbetween the post positivist and the constructivist paradigms (Ponterotto, 2005). The mixed approach aims at elaborating a systematic (but not

necessarily exhaustive) description and a theory about a phenomenon. This data analysis method has proven rigorous and has already been used by researchers in psychosocial

oncology (Thewes, Butow, Girgis, & Pendlebury, 2004; Thewes, Meiser, Rickard, &

Friedlander, 2003) and proves to be particularly suited for the study ofnew and poorly understood phenomena.

In the first step of analysis, similar themes that emerged from the narrative text were regrouped into categories (units of analysis). Similar themes were grouped into overarching trees (metacodes) and subcategories ofthese metacodes were placed in branches under these, themes having no apparent relation to other categories were kept

separately. The first interview was coded by a team oftwo members from the research group and codes were elaborated through discussion and agreement on themes. The second interview was coded by another team oftwo cod ers using the initial framework developed by the two other coders. Coders then met with the research team as a whole to refine the coding framework and achieve consensus. Once that was established, the coders proceeded to the coding of the remaining interviews. New codes were added as new themes emerged and the coding team met frequently together with the whole research team to achieve inter-coder consensus. Codes retlected categories set a priori from the interview package, from Othe literature reviewed and most importantly from the themes that emerged from the data. Coders also kept detailed memos, résumés and field notes during this process. Analyses continued until saturation was established and no new themes emerged from the data. Once the initial co ding was performed, the first author of this study proceeded to a more in-depth recoding of categories of interest for the present study. For example, under the category of di stress at diagnosis, the first author proceeded to refining subcategories of distress symptoms. Once the coding was fini shed the first author proceeded with the next analytical steps.

In the second step of analysis, data display, the narrative text now broken down into codes was displayed in either tables or matrices that allowed for the categorization of large sum of data .into manageable amounts of information (Miles & Huberman, 1984). In the present study, three types of matrices were used: a) checklist matrices, which is a table that may contain a scaling function (i.e. not at aIl, somewhat, quite a bit, very much) and allows to assess to presence of specific elements from the participants verbatim; b) time-ordered matrices: patient's experience is entered in a table arranged following a time sequence to see if a reported change occurs and c) conceptually