© Julie Babin, 2021

Stretching the icecap : Japan's Engagement and Policy

in the Arctic

Thèse

Julie Babin

Doctorat en sciences géographiques

Philosophiæ doctor (Ph. D.)

Résumé

L'augmentation des températures dans les régions polaires et les conséquences écologiques, sociales et économique qu’elles entrainent, pousse les gouvernements, le milieu académique et la presse à se questionner quant aux cadres de gouvernance polaires. A cela s’ajoute l’émergence d’acteurs non-limitrophes soulignant la légitimité de leurs préoccupations pour cette région en développant des stratégies dédiées à l’Arctique. Bien que l'attention générale se soit principalement concentrée sur la Chine et ses ambitions, le Japon, avec sa longue tradition de recherche polaire, développe une stratégie basée sur la coopération internationale pour soutenir ses intérêts dans et au-delà de l'Arctique.

Au travers sa politique arctique, le gouvernement japonais souhaite légitimer son ambition de contribuer aux grands débats de gouvernance présents et futurs, tout en assurant de son soutien constant à la souveraineté des États arctiques. La stratégie arctique japonaise s’aligne sur sa politique océanique nationale. Elle vise à renforcer les normes juridiques internationales, garantissant la stabilité et la prospérité politique et économique, dans l’Arctique et au-delà. Cette politique s’appuie sur l’expertise japonaise en matière de recherche et d’innovation permettant de renforcer la coopération économique et diplomatique avec les États de l’Arctique et en particulier le long de la Route du Nord. Cela renforce ses relations diplomatiques et commerciales et ainsi, peut permettre un rapprochement autour de dossiers sensibles, tels que le différend territorial avec la Russie sur les Territoires du Nord.

Basée sur des théories constructivistes issues du domaine de la géopolitique et des relations internationales, cette thèse vise à souligner qu'une fois de plus, ce qui se passe dans l'Arctique ne reste pas dans l'Arctique. La politique arctique du Japon ne fait pas exception à cet adage, et répond à des objectifs plus larges que la seule région arctique. Cette thèse interroge les fondements et les intérêts des acteurs impliqués dans l'élaboration et la promotion de la politique arctique du Japon. En mettant en évidence les éléments arctiques de cette politique, cette thèse met en lumière les différentes stratégies du Japon pour soutenir ces intérêts à l'intérieur et à l'extérieur de l'Arctique.

Abstract

With the increase in global temperature and climate change in the polar regions, governments, academics, and the press, question the polar governance frameworks. Can it cope with environmental, social-economical rapid changes in these vulnerable regions? Moreover, as the Arctic ice melts, non-bordering states underline their interest and concerns for this region, rising interrogation on the role of emerging actors who have or are perceived to have an interest in the polar regions. Beyond the icecap, non-bordering states are developing strategies to support their interests for this region. Although general attention has focused on China and its Arctic agenda, Japan, with its long tradition of polar research, is developing its strategy based on international cooperation to support its interests in and beyond the Arctic.

In its Arctic policy, the Japanese government wishes to legitimize its ambition to contribute to the present and future governance debates while always ensuring its support to the Arctic States' sovereignty and to the international legal framework. Japan’s arctic strategy builds on its research and innovation expertise to strengthen economic and diplomatic cooperation with the Arctic states and especially with Russia. This allows it to strengthen its diplomatic and commercial relations and thus advance specific sensitive issues such as the dispute over the Northern Territories with Russia. Japan’s Arctic policy aligns with the National Ocean Policy and the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy. It is based on the promotion and support of the international legal framework, freedom of navigation, and the peaceful resolution of conflicts that ensure political and economic prosperity.

Based on Geopolitics and International Relations' constructivist theoretical assumptions, this thesis aims to highlight that once again, as the saying goes, what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the arctic. Japan's arctic policy makes no exception and responds to broader goals than just the arctic. This dissertation questions the foundations and interests of the actors involved in developing and promoting Japan's Arctic policy. By highlighting the Arctic elements of this policy, this thesis highlights Japan's different strategies to support these interests inside and outside the Arctic.

Table des matières

Résumé... ii

Abstract ... iii

Table des matières ... iv

Lists of figures and tables ... viii

List of Figures ... viii

List of Tables ... ix

Notes on names, language and considerations ... x

List of abbreviations and acronyms ... xi

Acknowledgments ... xiv

Introduction ... 1

Plan ... 6

Theoretical and operational perspectives of the research ... 8

Literature Review... 8

Research question and hypotheses ... 12

Methodology ... 15

Chapter 1: A Japanese Arctic policy? ... 23

Conceptual framework ... 25

Constructivism in International Relations ... 25

Policy... 28

Part 1: Actors involved in Japan’s policy-making process... 30

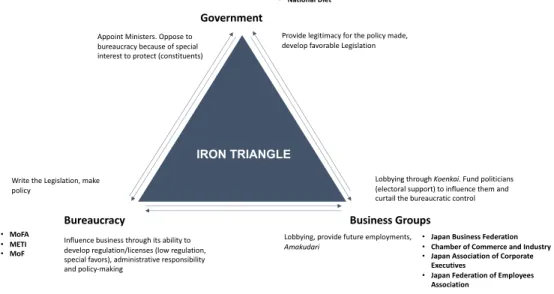

The Japanese Iron Triangle ... 30

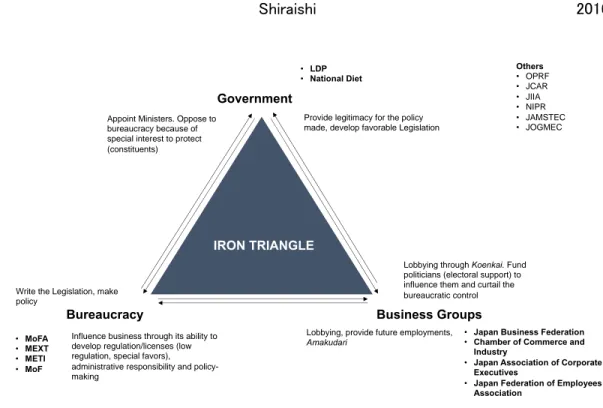

The Iron Triangle or Three Pillars theory and Japan’s Arctic Policy ... 38

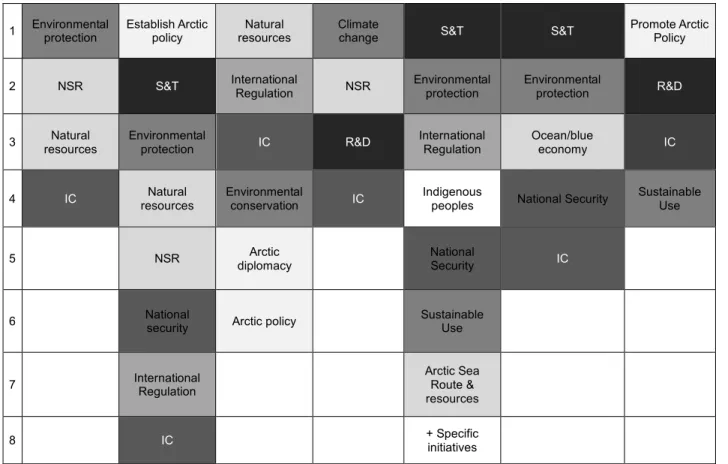

Part 2: Structure of Japan’s Arctic Policy... 46

Early initiatives and recommendations from the Japanese bureaucracy and interest groups to the government for further involvement in arctic affairs... 46

Structuration of Japan’s Arctic policy, the inscription of the Arctic in Japan’s Maritime Policy . 53 Japan’s Official Arctic Policy of 2015, a comprehensive policy ... 61

The development of the Third Basic Plan on Ocean Policy (2018) ... 69

Discussion ... 76

Chapter 2: Japan’s international cooperation in and for the Arctic, a balance between science diplomacy and geoeconomics ... 81

Part 1: The tradition of polar research and scientific cooperation to promote Japanese Arctic policy ... 85

Science diplomacy ... 85

Science Diplomacy in Japan and its role in the Arctic Policy ... 89

The development of science diplomacy in Japan ... 89

From Polar Sciences to Science Diplomacy in Japan’s Arctic Policy ... 96

International cooperation in research activities in the Arctic ... 103

Japan and the Arctic Council ... 115

Achievements of Japan’s science diplomacy in the Arctic ... 125

Part 2. The Japanese Arctic economic policy, an extension of its Indo-Pacific strategy or a policy specifically dedicated to the Arctic? ... 130

The rise of geoeconomics ... 130

The Role of Economic diplomacy ... 134

Japan’s Arctic Economic Strategy ... 137

traditional diplomatic relations? ... 153

Cooperation with Nordic States ... 157

Japan and Russia relation in the North, from territorial dispute, interregional cooperation, to economic cooperation ... 162

Economic ties between Tokyo and Moscow in the Arctic ... 170

Conclusion... 181

Chapter 3: Hokkaidō: from the ‘Road to the Northern Sea’ to ‘Japan’s gateway to the Arctic’ ... 185

Conceptual framework ... 188

Regionalism and Open Regionalism in international relations ... 188

Paradiplomacy and subnational governance ... 191

Conceptualizing North/ Northern/ Nordicity/ Northerness and Arcticness/Arcticity ... 204

Hokkaidō’s role in Japan’s northern history: the ‘Road to the Northern Sea’ ... 213

The development of the Northern Region Plan/Hoppōken kōso ... 219

The conceptualization of Hokkaidō as a northern region, Hoppōken kōso ... 220

The North in Hokkaidō Development Plans:... 225

The shared Northerness, Hoppoken Kōso in Hokkaidō paradiplomatic activities in the North ... 232

Hokkaidō in the Northern Forum, from founding member to business partner ... 232

« Winter is a Resource and an Asset », the International Association of Winter Cities for Mayors, Sapporo city’ diplomacy... 236

World Winter Cities Association for Mayors (WWCAM) ... 237

Hokkaidō: Japan’s gateway to the north and to the Arctic... 243

Hokkaidō University and the Arctic Research Center ... 243

northern regions? ... 247

The development of port infrastructures oriented towards the Northern Sea Route... 250

Conclusion... 253

Concluding remarks ... 256

References ... 263

Annex A: Dispatch of Experts to Arctic-related Meetings (Data provided by NIPR 2020/08/18). ... 293

For the 2015 Fiscal Year (FY) ... 293

FY2016... 293

FY2017... 294

FY2018... 295

FY2019... 296

Lists of figures and tables

List of Figures

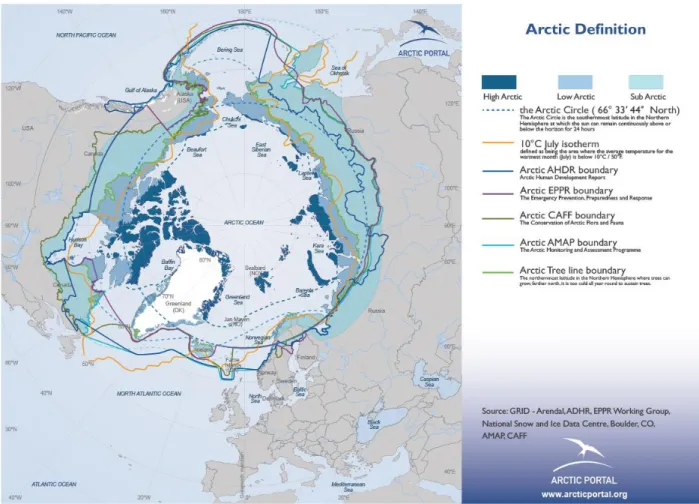

Figure 1: Arctic Definition ... 2

Figure 2: Word cloud of occurrence in Japan Official Arctic Policy (2015). Personal compilation. ... 21

Figure 3: Composition and relation among the Iron-Triangle in. Compiled by author. ... 35

Figure 4: Composition and relation among the Iron-Triangle in Japan’s Arctic Policy. Compiled by author... 39

Figure 5: Effects of Science diplomacy in the Arctic. Compiled by author. ... 87

Figure 6: Trends for Japan’s Science and Technology Budget Between FY2001 & 2019 [科学技術関 係予算の推移]. Source: Cabinet Office Policy Director (2019). In Yellow Initial Budge [当初予算], In Red Science and Technology Promotion Costs [うち科学技術振興費], In Grey the Supplementary Budget [補正予算], In Green the Reserve Fund [予備費], And in Yellow Dots for Local Governments [地方公共団体分]. ... 93

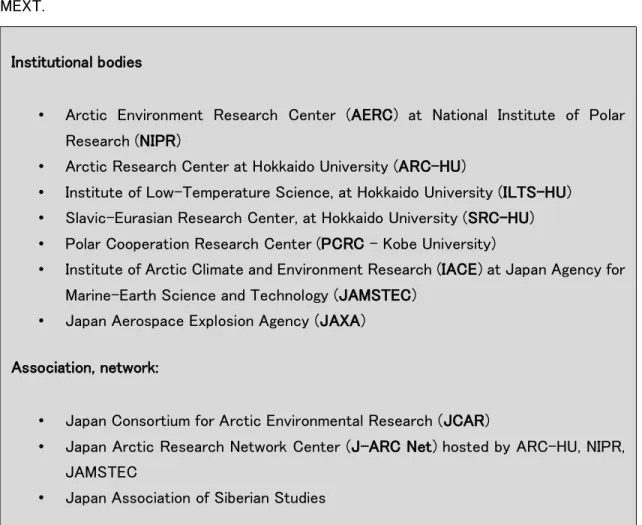

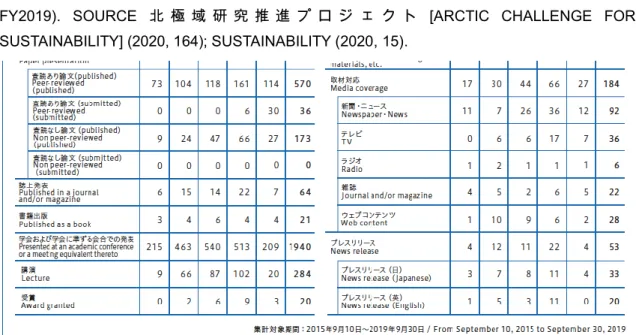

Figure 7: Number of research achievement during the ArCS project (2015-FY2019). Source 北極域 研究推進プロジェクト [Arctic Challenge for Sustainability] (2020, 164); Sustainability (2020, 15). ... 113

Figure 8: Strands of economic diplomacy: Japan. In Okano-Heijmans (2012, 65), slightly modified from Okano-Heijmans (2011). ... 136

Figure 9: Map on the Northern Territory Disputes from the Japanese Perspective (Nadeau 2016). ... 166

Figure 10: Winter and Summer Routes from Yamal LNG plans to Asian and European markets. Source: Eco R. Geo (2017). ... 172

Figure 11 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (Source: Ministry of Land 2008a). ... 203

Figure 12: 1802 map of Hokkaidō, Sakhalin and Kuril Islands assembled by Kondo Morishige (courtesy Hokkaidō University Library). In Irish (2009, 70). ... 216

Figure 13: 1802 map of Hokkaidō, Sakhalin and Kuril Islands assembled by Kondo Morishige (courtesy Hokkaidō University Library). In Irish (2009, 70). ... 216

Figure 14 : Source: Hoppōken-Sentā, 1982, p. 61 ... 222

Figure 15 Source : WWCAM Membership Procedure (World Winter Cities Association for Mayors (WWCAM) 2019). ... 240

Figure 16: source: https://www.arc.hokudai.ac.jp/en/international-collaboration/... 244

Figure 17: source Arctic Research Center (2019). ... 245

List of Tables

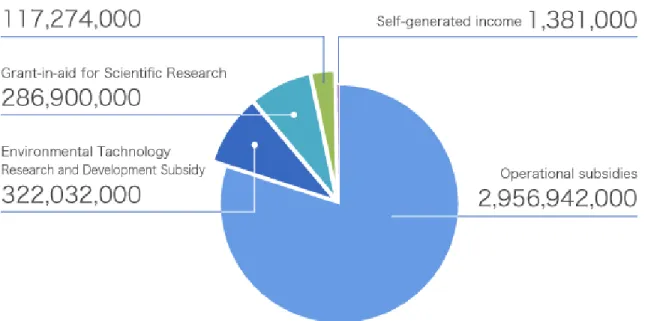

Table 1 : Differences between the Iron Triangle and Three Pillars approach. Compiled by author... 40 Table 2: This table summarizes various measures initially recommended for the establishment of an Arctic policy on the part of Think Tank (OPRF, JIIA), and in official documents (Blue Book, Basic Plans, and official policy). Compiled by author. ... 78 Table 3: Institutes and associations involved in arctic research activities in Japan (Compiled by author). ... 99 Table 4: Total Budget (FY2018) 3,684,529,000yen (34Million USD). Source: National Institute of Polar Research (2020). ... 100 Table 5: GRENE Arctic Climate Change Research Project (former project of the ArCS) budget per year in yens. Data provided by NIPR (2020/08/18). ... 107 Table 6: ArCS Budget per year in yens. Data provided by NIPR (2020/08/18). ... 109 Table 7: Dispatch of Experts to Arctic Council-related Meetings between FY 2015 and FY2019 (Data provided by NIPR 2020/08/18). ... 120 Table 8: NUMBER OF MEETINGS ATTENDED BY JAPANESE EXPERTS BETWEEN FY2015 AND FY2019 WITHIN THE ARCTIC COUNCIL (COMPILED BY AUTHOR). ... 121 Table 9: Evolution of the Budget dedicated to the GRENE and ArCS projects between Fiscal Year 2011 and 2019 in yens (data provided by NIPR 2020/08/18). ... 126 Table 10: Paper presentations: The following are the papers published in academic journals, conference proceedings, books, etc. Information extracted from: 北極域研究推進プロジェクト [Arctic Challenge for Sustainability] (2020, p. 164). ... 127 Table 11: Presentations at academic conferences, public lectures and media coverage. Information extracted from: 北極域研究推進プロジェクト [Arctic Challenge for Sustainability] (2020, p. 164). 127 Table 12: Japanese EPA and FTA agreements. Source: Japan's 2019 Economic Bluebook, p. 260. ... 140 Table 13: Source: HIECC, 2015: 3. ... 204 Table 14: successive plans in Babin & Saunavaara 2021. ... 229

Notes on names, language and considerations

For Japanese names, this thesis follows the Japanese convention that family names precede personal names like Abe Shinzo. However, the names of Japanese authors of English-language work follows the English practice of the personal name preceding the family name like Abe Shinzo. Moreover, macrons are put on long Japanese vowels like Hokkaidō or Dōgakinai Naohiro.

The utmost effort was made to collect and analyze the Japanese stakeholders' voices and views through written documents, participant observation, and semi-structured interviews conducted in Japanese. However, due to the author's limited Japanese skills, the analysis of policy documents is mainly based on English translation translations when available. When these documents were not available in English, a translating tool (google translate) was used to translate Japanese to English. In order to respect the accuracy of terms in Japanese, they will be written in this dissertation in English as well as in Japanese (when possible).

Since the official Japanese documents (Basic Plan and Arctic Policy)1 prefers in its English

translations the expression of “Arctic Sea Route” (hokkyoku kai kōro) to the term “Northern Sea Route” (also hokkyoku kai kōro), the two expressions will be used in this dissertation to analyze Japan’s interests and strategies in this region (Rafnsdóttir 2019). We can observe a parallelism with China, which in its most recent documents, prefers Arctic Silk Road, to the expression Northern Sea Route.Finally, although the Northern character of the Ainu people, Hokkaidō indigenous people, alone deserves a study, this dissertation will focus on a Wajin

perspective, Japan's main ethnic group, representing Japan’s national level.

1 The expression “Arctic Sea Route” is used 7 times in the 2013 Basic Plan on Ocean Policy, 10 times in the 2015 Arctic Policy,

List of abbreviations and acronyms

AC: Arctic Council

ADS: Arctic Data Archive System

AEPS: Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy AERC: Arctic Environment Research Center AMAP: Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program AMBI: Arctic Migratory Bird Initiative

AMSA: Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian Nations ASM: Arctic Science Ministerial

ArCS: Arctic Challenge for Sustainability ARC: Arctic Research Center

ASSW: Arctic Science Summit Week

CAFF: Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna

CLAIR: Council of Local Authorities for International Relations CSTI: Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation

CSTP: Council for Science Technology Policy EEZ: Exclusive Economic zones

EGBCM: Expert Group on Black Carbon and Methane FOIPS: Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy

FTA: Free Trade Agreement FY: Fiscal Year

GRENE: Green Network of Excellence GRIPS: Graduate Institute for Policy Studies HCDP: Hokkaidō Comprehensive Development Plan

HIECC: Hokkaidō International Exchange and Cooperation Center IASC: International Arctic Science Committee

IC: International Cooperation

ICT: Information and Communication Technologies IMO: International Maritime Organization

INSROP: The International Northern Sea Route Program IPY: International Polar Year

ISAR: International Symposium on Arctic Research

JAMSTEC: Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology JANSROP: Japan Northern Sea Route Program

J-ARC NET: Japan Arctic Research Network Center JARE: Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition JAXA: Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency

JBIC: Japanese Bank for International Cooperation

JCAR: Japan Consortium for Arctic Environmental Research JETRO: Japan External Trade Organization

JGC: Japan Gaz Company

JIIA: Japan Institute of International Affair

JOGMEC: Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation LDP: Liberal Democrat Party

LNG: Liquefied Natural Gas

MAFF: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

MARPOL: International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships METI: Ministry of Trade and Industry

MEXT: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology MIC: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

MLIT: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport MoD: Ministry of Defense

MoE: Ministry of the Environment MoF: Ministry of Finance

MoFA: Ministry of Foreign Affairs MOHA: Ministry of Home Affairs MOL: Mitsui Osk Line

NAL: National Aerospace Laboratory of Japan

NASDA: National Space Development Agency of Japan NF: Northern Forum

NGO: Non-governmental organization NIDS: National Institute for Defense Studies NIPR: National Institute of Polar Research

NPARC: North Pacific Arctic Research Community NSR: Northern Sea Route

NSS: National Security Strategy NSR: Northern Sea Route NWP: Northwest Passage

OSA: Official Development Assistance

OPRF: Ocean Policy Research Foundation, within the Sasakawa Peace Foundation (now OPRI) OPRI – Ocean Policy Research Institute, within the Sasakawa Peace Foundation

PAME: Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment PCRC: Polar Cooperation Research Center

PM: Prime Minister

R&D – Research and Development

SCTF – Scientific Cooperation Task Force SDWG: Sustainable Development Working Group SLCP: Short-lived Climate Pollutants

SNG: Subnational government

SOF – Ship and Ocean Foundation (in the Sasakawa Peace Foundation) SOLAS: International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea

S&T: Science and Technology

STI: Science, Technology and Innovation

SWIPA: Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic

UNCLOS – United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea USSR: Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

Acknowledgments

The completion of this doctoral thesis would not have been possible without the support and help of many people. As such, I would like to express here my sincere thanks to all the people who, in one way or another, have supported me in this long adventure.

First of all, I would like to thank my thesis director, Mr. Frederic Lasserre, for supporting this doctoral thesis from its conception and having accompanied me through all these years of research. He has been a constant support. His listening skills and invaluable advice enabled me to refine this research. I would like to thank Mr. Ohnishi Fujio and the entire ARC laboratory at Hokkaido University for welcoming me on several occasions on my field trips and internships, and for making many and crucial resources available to me.

I extend my thanks to Ms. Tonami Aki, professor at Tsukuba University for her comments and help on this dissertation. Her work and scientific support have contributed significantly to my understanding of Japanese polar policy. I also wanted to thank Mr. Etienne Berthold, professor at Laval University, and Bernard Bernier from University of Montreal, for their participation in my thesis jury.

My thanks also go to my friends, Guillaume, Jaewon, Yoni, Elodie, Leslie, and Isabelle. I would like to thank you for your visits in Quebec, skype sessions, Korean food, and supporting me during all those years. I also thank my neighbors, Manon, Annabelle, and Gabby, for all the study, crafting and cooking sessions during this long confinement. I also think of my family in Japan: Sou-san, Aiko, Shu, Sō, and Kaori, who welcomed me so many years ago into their home and family. Your unwavering support has undoubtedly contributed to my great interest in the geopolitics and international relations of Japan.

I address my deepest thanks to my family, particularly to my mother, Béatrix Caruel for her numerous advices and proofreading, and my father and my sister, for their continuous support. Without your moral and financial support, I doubt that this thesis could have been completed.

Introduction

It seems impossible to open a dissertation in geography without starting with a map presenting the subject of study, and in this case, the Arctic. The Arctic, derived from the name arctos (bear) in ancient Greece, stands in opposition to Antarctica. It blends ocean, ice, and land and connects all the northern hemisphere with the European, American, and Asian continent. Already in the 1970s, the renowned geographer Louis Edmond Hamelin underlined the question of the many definitions of the North that are still found today in the definitions of the Arctic. These definitions can be geographic2, climatic3, biological4, political5, demographic, etc. He further noted that a

"simply climatic or botanical definition of a country is not sufficient for a scientist interested in ensembles" and "that a single physical factor, taken in isolation, cannot provide the boundaries of the North and, consequently, bear witness of all this region" (Hamelin 1980, 75-77).

The following map illustrates some of these definitions and their more or less inclusive character, depending on the criteria selected or the objectives sought. This dissertation retains the Arctic Council's limits, including the eight-member states: Canada, the United States of America (US), Denmark (Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. This map further recalls that, although being the subject of this dissertation, Japan is not a border state of the Arctic. If we can observe proximity between the northern islands of Japan (Hokkaido, Kunashiri, Etofuru) with the Russian territory of the Sakhalin, the fact remains that the Japanese archipelago is not part of the Arctic region.

2 Line of the Arctic Circle, including the Aleutian Range, Hudson Bay, and parts of the northern Atlantic Ocean. 3 With the limit of 10 ° C July isotherm.

4 Limit of tree line, extent of permafrost, or sea areas covered by ice.

5 With the five Arctic coastal States: Canada, the United States, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, and Russia (also called the

In the Arctic, the natural environment’s rapid changes, such as the decrease in sea ice and the collapse of permafrost, are closely associated with significant changes in new socio-economic activities in the circumpolar region. With the increase in global temperature, climate change, and the various socio-economic issues in the Arctic, the Arctic states are questioning the role and the influence of non-Arctic actors interested in this polar region or perceived as such (Steinveg 2020; Youngs 2012; O.R. Young 2005). As several climate models show a link between climate change in the Arctic Ocean and prevailing conditions in Eastern Asia, major Asian powers argue argument that they have a legitimate place to contribute to debates on governance and protection of the Arctic (Bertelsen and Gallucci 2016; Gadihoke 2013; Holroyd 2020). This interest in the Arctic is linked to the development of natural resources extraction and Arctic sea routes utilization. To justify their interest in the Arctic region, non-bordering states like China have

articulated the concept of “near-Arctic State” (Bertelsen and Xing 2016; Lanteigne 2017)6.

However, despite those claims, these States do not possess any Arctic territory and must play along with Arctic States to participate in Arctic debates and institutions such as the Arctic Council7.

The admission of Asian States as Observers at the Arctic Council in 2013, especially China, has raised negative reactions and triggered speculations about their agenda in the Arctic (Babin and Lasserre 2019; Manicom and Lackenbauer 2013; Wright 2011)8. The control and management of

Arctic resources (mineral, living), as well as maritime routes (Bering Strait), might therefore provoke power rivalries in order to take advantage of their control (Gonon and Lasserre 2001). Therefore, the Arctic territory is more than ever at the heart of the concerns of political actors in and outside this region, generating power rivalries that are the central subject in geopolitics studies.

Despite Mike Pompeo’s speech at the Rovianiemi (Finland) during the Arctic Council meeting in 2019, questioning the place of non-arctic States, and in particular China, in this region, the emergence of the concept of GlobalArctic9, and of an Arcticization process, can be seen as a

symbol pointing toward the loosening of the stakeholdership in Arctic affairs where non-state actors that are very much connected and somehow stretch the boundaries of the Arctic region (Väätänen and Zimmerbauer 2019; Finger and Heininen 2019; Pompeo 2019) (Babin & Saunavaara 2021).

Papers seem to have focused on China's interest in the Arctic region, assimilating Asian states' interest in this region. Although we can observe certain similarities in China's policies, Japan and

6 For China and Korea: "near-Arctic state", for the United Kingdom: "sub-Arctic nation".

7 The Arctic Council, which was formalized in 1996 by the Ottawa Declaration, is the leading regional forum for cooperation

and collaboration in the Arctic. It is composed of Canada, Denmark, Finland, Russia, Sweden, Norway, United-States, Iceland (member States), and Permanent Participants representing the Arctic indigenous people.

8 “Two views emerge from western academic articles on Polar Orientalism that Dodds define as ‘a way of representing,

imagining, seeing, exaggerating, distorting and fearing 'the East' and its involvement in Arctic Affairs’, which is only amplified by the application and admission of Asian States to the Arctic Council (Dodds and Nuttall 2016). On one side there is a vision of a threatening Asia led by China willing to invade the AC and reshape it. The second view would be the idea of Asian States wishing to participate in an inter-State forum for collaboration while respecting the rule of indigenous peoples and Arctic States”. In Babin and Lasserre (2019, 6).

9 A comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach conceptualizing the Arctic as “a multifaceted region within a changing global

Korea, these three states have developed three distinct Arctic strategies. While climate change and the development of resources (mineral and sea routes) pose many political, economic, and technological opportunities, Japan proposes to use its expertise in research and development to respond to the challenges in the Arctic.

Changes in the Arctic environment have political, economic, and social effects, not only in the Arctic but also globally. Resulting opportunities and issues are attracting the attention of the global community, both of Arctic and non-Arctic states.

Japan is called upon to recognize both the Arctic's latent possibilities and its vulnerability to environmental changes, and to play a leading role for sustainable development in the Arctic in the international community, with foresight and policy based on science and technology that Japan has advantage in order to achieve sustainable development (Headquarters for Ocean Policy 2015).

While the interest on the Arctic from non-bordering states seems to be growing, Japan is emphasizing its role as a pioneer, especially in Asia, in polar research to justify its attachment to this region. The first Japanese polar expeditions date back to 1911-1912 with the expedition of Lieutenant Shirase Nobu, which left for Antarctica in the context of conquering the poles, the last unexplored territories on earth. Although this expedition was not conclusive for Japan, it remains the starting point of a century of expeditions and research programs dedicated to the polar regions. Beyond ecological considerations (global warming, pollution, consequences, consequences on the precipitation regime, etc.), Japan underlines the potential economic opportunities for its companies, and in particular, of hydrocarbon resources. Consequently to the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, which caused the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power station, Japan had to make a drastic shift from nuclear energy to other energy resources, including Liquefied Natural Gaz (LNG)10 (Shibasaki et al. 2018). Following this incident, and in a context of

heightened tensions in the Middle East, Tokyo realized that it must diversify its energy import sources to ensure its energy security. In this perspective, the Arctic hydrocarbon resources appear to catch the interest of the Japanese government. Furthermore, while supporting the Arctic states' sovereignty and primacy in the region, Tokyo wishes to be included and participate

10 Natural gas cooled down to liquid form (-162°c), allowing to reduce the storage capacity and making its transport easier and

in present and future debates regarding governance and the development of the normative framework for the Arctic.

From the 2010s, the Japanese government took up questions related to the Arctic to reorganize research and make it more efficient (GRENE network, J-ARC, ArCS, ArCS-II), define its strategic objectives, and inscribe its Arctic policy in its Ocean Policy. In 2015, and during the Arctic Circle's annual meeting11, the Japanese Ambassador for Arctic Affairs, Mrs. Shiraishi Kazuko, unveiled

Japan's official policy for this region, adopted the very same day. The Cabinet's adoption of this comprehensive document made it possible to structure arctic-policy-related issues by defining objectives and a series of initiatives to address them. This policy is a part of Japan's Ocean Policy, clarified in 2018 by adopting the Third Basic Plan on Ocean Policy. It revolves mainly around international cooperation with the Arctic-States and Institutions for research and economic development in the Arctic.

The lack of empirical studies on the Japanese government's objectives in the Arctic limits our understanding of this phenomenon. Beyond these elements, one can wonder what is arctic in the Japanese Arctic policy: Is it merely the reorganization of arctic research? The rebranding of bi and multilateral relations with the Arctic states to fit into the general trend? Beyond scientific and economic considerations, does this policy respond to political vocations such as a rapprochement with Russia to advance specific issues such as limiting China's influence in the region and securing new LNG sources important to support its energy security, or solve the dispute over the Northern Territories? Therefore, this doctoral thesis's objective is to paint a contemporary portrait of the Japanese government’s strategy in the Arctic by exploring the policies formulated, the scientific and economic agreements developed in this region.

Peer-reviewed scientific publications on Japanese Arctic policy remain limited. While it is easy to find scientific content on Chinese strategies or general comparative analysis of China, Korea, and Japan, very little is written about the Japanese Arctic strategy and its objectives. At present, the

11 The Arctic Circle is the largest Arctic-themed conference, founded by former Iceland President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson. It

is a place where various stakeholders such as politicians, government officials, indigenous peoples' groups, and industry stakeholders in the Arctic and Arctic Council observer countries gather.

main sources of information come from private organizations (OPRI), government publications (MoFA), general or more specialized media, and Japanese researchers (Tonami Aki, Ohnishi Fujio, Ikeshima Taisaku). To overcome the relative lack of empirical studies, primary data was collected through semi-structured interviews. Then, statistical data was drawn through secondary sources, and information was collected from national press articles.

On the other hand, if these sources contain relevant information, the use of interviews requires prudence and discernment, particularly because of the biases resulting from the narrator’s representations and biases, even with official declarations that often reflect policy and diplomatic objectives. This research was designed as multidisciplinary in its approach and covered International Relations, geopolitical science, economics, law, and social sciences in general. From the first moments of this thesis project's design, this consultation of the literature provided the necessary tools for establishing a theoretical, conceptual, and methodological framework to address the present problem in all its complexity.

Plan

The first chapter of this thesis focuses on the study of the structure of Japan’s Arctic policies. The way Japan understands its own arctic policy will be underlined through the different initiatives, documents and the actors (governmental, private interest, and bureaucracy) involved in this policy(ies). Is there something specific to the Arctic in this policy(ies) or are they the continuation of Japan’s current Ocean Policy.

Chapter 2 will focus on the role of International Cooperation in Japan’s Arctic strategy. A first sub-chapter will be dedicated to the role of Science Diplomacy in Japan’s strategy concerning the Arctic, and the means to implement this strategy in Japan and in international platforms such as the Arctic Council. The second sub-chapter will assess Japan’s geoeconomic strategy in the Arctic with its relationship with the Arctic States. This chapter makes it possible to put into perspective and better understand the Arctic part of the bilateral relations maintained between Japan and the Arctic States, and more particularly with Russia. Is the Japanese Arctic policy Japan's policy for the Arctic a summation of its economic relations with the Arctic states? Does this cooperation between Japan and Russia correspond only to scientific and economic

partnerships, or does it respond to political objectives such as resolving the dispute over the northern territories?

This second chapter partially includes three articles published in 2019: the first is a paper cowritten with Frederic Lasserre for the peer review journal Polar Geography “Asian states at the Arctic Council: perceptions in Western States”. The second paper, “Les gouvernements infrarégionaux le développement de la paradiplomatie”12, was published by the French journal

Relations Internationales, and the third paper “Les nouvelles routes de la soie chinoises: perspectives japonaises”13 was published in Cahiers du GÉRAC, Groupe d’études et de recherche

sur l’Asie contemporaine & Université Laval.

Chapter 3 is based on an article accepted under minor revision in the peer-reviewed journal Asian Geographer “Hokkaido: From the ‘Road to the Northern Sea’ to ‘Japan’s Gateway to the Arctic’ on March 2021. This chapter will outline how foreign relations of subnational entities are currently understood in the framework of North to Arctic relation. This chapter, which constitutes an essential section of the thesis, questions the role of the Japanese province of Hokkaido as the North of Japan: first as the Road to the Northern Sea, then as a gateway to the Arctic. More specifically, it aims to determine the initiatives put in place by sub-national governments with other regions of the North, redefined as arctic region, their role in Hokkaido's development policy, and their use in the national arctic policy of Japan.

Finally, the general conclusion aims to recall the research hypotheses while presenting the main conclusions of this study, the necessary justifications, and suggests avenues for future research and summarizes the key findings of this study.

12 Sub-regional governments the development of paradiplomacy paradiplomatie published in 2019. 13 The New Chinese Silk Roads: Japanese Perspectives, published in 2019.

Theoretical and operational perspectives of the

research

This section first presents a synthesis of the literature review carried out in the first stages of the research project, but since revised, and secondly allows to introduce the research question and the hypotheses, to finally detail the methodology applied within the framework of this project.

Literature Review

The literature compiled for this research project includes statements, assessments, research works from scholarly journals (Japanese and international) and policy think tanks, news agencies, Foreign Policy Magazines, and commentary pieces from media outlets and experts. The literature mobilized concerns general literature on Japanese foreign policy, international cooperation in the Arctic, and more specific areas such as subnational governance in Japan. It includes generalist approaches on the organization of Japanese public policies, on arctic institutions, the environment, security, arctic resources (mineral and fishery). These aspects are studied across many disciplines and involve geography, political science, international relations, history, international law, sociology, economics, anthropology, and natural sciences studies and theories.

The end of the Cold War marks a turning point for the Arctic with many studies on cooperation and geopolitics in this region (Bloomfield 1981; O.R. Young 1985, 1987, 1992b). The International Northern Sea Route Program (INSROP) organization, by Russia, Norway, and Japan in 1991 is unprecedented for this time. It is the first comprehensive study on the utilization and commercialization of the Northern Sea Route (NSR)14 with a non-bordering state like Japan (Ship

& Ocean Foundation 2001). This study is considered particularly pioneering for its time in terms of cooperation and for the results obtained. This study was conducted on the Japanese side by the precursor of the Ocean Policy Research Institute (OPRI) and with support from the Nippon Foundation (Sasakawa - Nippon Peace Foundation). The INSROP, and later of Japan Northern

14 The Northern Sea Route runs along the Russian coast in the far north following the continent extending from the Barents

Sea Route Program (JANSROP), made it possible from the 1990s to obtain very detailed data concerning navigation in the NSR. The OPRI notes that compiled data (topographical on energy, mineral, forest, and fishery resources) from Far Eastern Russia were compiled into the world's first geographic information system (JANSROP-GIS). The results were included in official publications such as the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report (Arctic Council / PAME 2009). Following INSROP and JANSROP, there was a pause in comprehensive publications and studies on the Arctic until the end of the 2000s.

Following the application and admission of new observers, particularly from China in 2013, publications regarding Asian strategies for the Arctic have increased significantly since 2013 (Lasserre 2010; Alexeeva and Lasserre 2012; Wright 2011; Chen 2012; Bennett 2015; Lanteigne and Ping 2015; Kossa 2016; Enge 2018). These studies and press articles have mainly focused on China's ambitions for the Arctic and on comparative studies of Chinese, Korean and Japanese strategies (Holroyd 2020; Tonami 2019; Beveridge et al. 2016; Sakhuja and Narula 2016a; Hasting 2014; Bennett 2014; Jakobson and Lee 2013; Zhuravel 2016; Babin and Lasserre 2019). The studies focusing on the Japanese Arctic strategy are more numerous than for China. They mainly focus on the development and organization of this policy between the second Basic Plan on Ocean Policy and the official policy of 2015 (Rafnsdóttir 2019; Grzela et al. 2017; Ohnishi 2016; Tonami 2014d).

While the studies on the Arctic region in geopolitics and international relations have been increasing since the end of the Cold War, it is only in the 2010s that studies on this subject began developing in Japan. The role of the Ocean Policy Research Institute (called OPRF and SOF in the past) must be highlighted in the organization of conferences and workshops to promote interest and research on the Arctic (The Arctic Conference Japan 2012). From the literature, it can be observed that the existing literature on Japanese polar research has long concentrated on Antarctica and natural sciences studies. However, with the opening of the Arctic in the 1990s, the literature has gradually opened up to this region and the humanities (Enomoto 2017).

For decades Japanese literature on polar issues was divided by sector: Antarctica on the one hand (Joyner 1989; Hamre 1933; Wouters 1999; Goodman 2010), the Arctic on the other (Jakobson and Lee 2013; Ken Coates and Holroyd 2015). Japanese literature dealing with the

Arctic (natural science and humanities) has grown in recent years, with publications in Japanese and English and mainly since the launch of the national ArCS project in 2015 (Stensdal 2013, 2016; 北極域研究推進プロジェクト [Arctic Challenge for Sustainability] 2020). Articles and books are increasingly the objects of collaboration with other researchers outside Japan, and increasingly multidisciplinary approaches. Much of the literature in social science and press release devoted to Japan and the Arctic focuses on 1: the past of polar research activities, 2: the arrival and the contribution in the Arctic Council, 3: projects related to resources extraction, transformation and transport (Liquid Natural Gaz). Humanities studies devoted to Japan and the Arctic are, for the most part, written by Japanese scholars (in English and Japanese) (Tonami 2018, 2017; Ikeshima 2016; Ohnishi 2016; Kamikawa and Hamachi 2016; Ikeshima 2015; Ohnishi 2015, 2014; Tonami 2014c, 2014d, 2014a), reports from private organizations (JIIA 2013; Carnegis Moscow 2016; Ocean Policy Research Institute 2015; Enomoto 2017; Center 2019), or the subject of student’s dissertation (Rafnsdóttir 2019; Grzela et al. 2017).

Ohnishi Fujio, Tonami Aki, and Ikeshima Taisaku, are the main researchers in Japan working on Japanese Arctic policy issues. Ikeshima's articles focus on the aspect of security in the Arctic and their impacts for Japan (Ikeshima 2015, 2014, 2017), and the Chinese strategy for this region (Ikeshima 2013). He also questioned Japan's involvement and contribution as an observer in the Arctic Council and the limitations that entail (Ikeshima 2016). Tonami and Ohnishi focus their studies on the development of Japanese Arctic policy and underline that well before the Japanese government began to be interested in Arctic affairs, researchers in Japan had long been actives in the polar regions. They note that interest from shipping companies and private emerged in the 1990s with the development of studies on the Northern Sea Route (INSROP), and again 2010s with mineral resources development have been lobbying for the Japanese government's involvement (Tonami and Watters 2012; Ohnishi 2013a, 2013b; Tonami 2013; Ohnishi 2014; Tonami 2014d; Ohnishi 2015, 2016; Tonami 2017, 2018). If Tonami uses the Iron Triangle approach theorized by Drifte in 1996, Ohnishi prefers to use an approach based on three pillars. Despite two different denominations, their respective approaches underscore the role of bureaucracy, government and business actors in shaping and sustaining Japanese Arctic policy.

In one of her papers, Tonami highlights a related conception of Japan's polar regions (Tonami 2017). Although the polar regions are linked in the collective imagination (cold, isolated places), and although Japanese polar research centers and institutes are interested in the study of the two polar regions (with a particular focus on Antarctica), Japan does not have a unified polar policy (Tonami 2017, 2016b). Indeed, if Japan published its official Arctic policy in 2015, it does not have a policy specifically dedicated to Antarctica. Tokyo recognizes the legal framework specific to these two regions: such as the Antarctic Treaty, the sovereignty of the Arctic States over their exclusive territories and zones, but also the rule of international law embodied in the United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the application of the Polar code, etc. Despite many similarities and the traditional association of polar regions, this geopolitical differentiation highlights these two regions' differences. While the proposal, emphasized by several researchers and author of an Arctic treaty based on Antarctica, seems more unlikely, it raises the question of understanding a polar policy (Tonami 2017, 489).

In her article, Exporting the developmental state: Japan's economic diplomacy in the Arctic, Tonami (2018) discusses the role of economic diplomacy in Japan’s arctic strategy to promote its foreign policy by underling the developmental state of Japan. According to her, Japan traditionally uses its involvement in science and technology to promote and achieve economic security and growth (for example, through Official development assistance agreements -ODA), and uses the same approach in the Arctic.

Although Japanese government delegates were able to make statements regarding Japan's Arctic strategy from the early 2010s (Horinouchi 2010), developing working groups and task forces, it was not until 2013 that the Arctic is emerging in Japanese ocean policy (Cabinet Office of Japan 2013). The literature further emphasizes China and South Korea's role in the Japanese government's interest in the Arctic (NIPR 2017; JOGMEC 2019; ARC 2019; Holroyd 2020; Knecht 2016; Tonami 2016a; Sakhuja and Narula 2016a; Tonami 2014a; Hasting 2014; Bennett 2014). A second overarching message put forward by popular and academic articles is that attraction of natural resources, and sea routes are the driving force behind Japan’s policy (Mroczkowski and Hsiao 2012; Rowe and Lindgren 2013). The Japanese government declared its interest in the region basing its statements on (i) climate change occurring in the region, (ii)

potential discoveries and exploitation of natural resources in the future, and (iii) emerging new routes for navigation.

Research question and hypotheses

The climatic upheavals that have been unfolding on a planetary scale since the end of the 20th century and which significantly affect the polar regions point to the possibility of a wide range of activities in the Arctic, including commercial shipping, fishing, tourism, and mineral resource extraction project in the Arctic. Since the beginning of the 2010s, and in parallel with the development of Chinese and South Korean interest in the Arctic, the Japanese government has decided to tackle issues relating to the Arctic by reorganizing the Japanese arctic research sector. Being the world's largest importer of Liquefied Natural Gaz (LNG), Japan is particularly interested in developing projects related to the extraction and transport of natural gas to Asian markets, including the Japanese market.

This doctoral dissertation in geographic sciences deals with Japanese Arctic policy, development, organization, and implementation. It aspires to highlight the types of actors and their nature, public, private, mixed, or other, the internal and external factors and issues, political, diplomatic related to the development and support of this Arctic policy. Thus, the thesis is interested in the intentions or real capacities of Japanese policy dedicated to the Arctic and the representations that accompany them. It aims to highlight a set of variables that determine these Japanese actors' interest in getting involved or investing in the Arctic region. These factors can be political, economic, diplomatic, logistical, and geophysical and are accompanied by representations of an unfolding phenomenon on the territory's scale.

Research question:

Considering these elements, this dissertation proposes addressing the following question: What are the foundations and actors involved in the development and promotion of Japan’s Arctic policy, and to what extent does this policy respond to economic and political objectives that go beyond the Arctic?

This dissertation's overall objective is to investigate and define the dynamic interactions among governmental, academic, and economic actors in Japan concerning Arctic interests, emphasizing the Russian Arctic region. This analysis makes it possible to assess the current governmental, academic, and industrial interests in the arctic region. But also, to help determine what the Arctic is in Japan's Arctic policy. To analyze Japan’s northern province Hokkaido's role and exchanges with other northern/arctic regions, together with its role in Japan's overall arctic strategy. Finally, to assess the extent to which the Japanese government's interest in the Arctic corresponds to a general trend and strengthen bilateral relations with the Arctic states, mainly Russia, to advance political issues.

Hypotheses

Although general and specific objectives were established from the first moments of this thesis's project, they have evolved during the research in three hypotheses. The research's originality compares Japanese Arctic policy to its scientific and economic diplomatic strategies to underline its objectives. Specific objectives had been established from the first moments of this thesis's project, which evolved during the research in three hypotheses. The research's originality is to compare Japanese Arctic policy to its scientific and economic diplomatic strategies to underline its objectives.

The first hypothesis, examined through chapter 1, postulate that Japanese Arctic policy is part of the extension of its oceanic policy and in continuation of the principles promoted in its Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy: proactive contribution to peace, ensure the Rule of Law, promote international cooperation, and Panoramic diplomacy. The development of a formal Japanese Arctic policy has enabled Japan to structure and strengthen its base, providing it with strategic objectives. While recognizing the Arctic States' primacy and sovereignty, and the present legislative frameworks, it aims to support Japan's involvement in future governance debates and economic opportunities.

The second hypothesis, verified in the second and in the third chapter, postulates that the official Arctic policy's development corresponds to a general trend where non-Arctic states are taking a stand for this region. Indeed, even though Japan was the first Asian State to start polar

exploration, external factors such as the growing Chinese and South Korean interests for this region are significant factors influencing Tokyo's interest. The Japanese government's involvement in Arctic-related issues is a way for it to develop its image as a scientific and technological leader and mediator in the area of peaceful conflict resolution. This involvement also allows it to develop or strengthen its bilateral relations with the Arctic States and promote its national interests (economic or diplomatic). It relies on its long history of polar research activities, renewed scientific cooperation with the development of specific programs such as GRENE, ArCS, and ArCS-II, and its contribution to international forums such as the Arctic Council or the Arctic Circle. It is also based on economic collaboration, particularly with projects on the extraction and transport of hydrocarbons (LNG) to Asian markets, including Japan. This scientific and economic collaboration around the Arctic allows Japan to strengthen its bilateral and multilateral relations with the Arctic States, and in particular, with Russia (Yamal).

Finally, the third and final hypothesis, which will be verified through chapters 2 and 3, postulates that Japan’s strategy in the Russian Arctic relies on economic and political objectives, including an economic partnership to ensure Japan energy security (LNG) and a diplomatic rapprochement to resolve the dispute over the northern territories and finally conclude a peace treaty. It further builds on the pre-established relationships between Japanese and Russian subnational governments to establish a dialogue between Tokyo and Moscow.

Methodology

A varied methodology was implemented with an analysis of the collected documentary corpus to carry out this thesis. It is supplemented by the realization of studies of various kinds (analysis of interviews, statistical data analysis, comparative studies, etc.). This research is also based on comparative studies of the Arctic policies of Asian states prepared for the dissertation of a master’s degree in Geopolitics and International Security.

The corpus of primary sources is composed of official documentation (statements, assessment, research work) extracted from various Japanese ministries (MEXT, MoFA, MLIT, METI, Cabinet office), Research Institutes and Think Tanks (OPRI, JIIA), Arctic institutions (Arctic Council, Arctic Circle, Northern Forum, etc.), but also from other actors involved in the region (States, indigenous peoples, NGOs, regional governments, multinational companies) to understand their position with the strategies developed fully. The Analyze and the comparison of the available resources, such as discourses and interviews, led to creating a representative sample of government officials, business actors, and researchers in the Arctic.

The relationship of the researcher to the human subjects of the study: research ethics

An exemption was provided exempt from Ethics Committees for Research with Human Beings of Laval University (CERUL)15 for this the project, as it fulfills the first exemption condition present

in section A of form VRR-103 received and approved on 2015 November 28th, i.e.:

“Research involves interacting with people who are not personally targeted by the research, in order to obtain information. For example, a researcher may collect information about organizations, policies, methods, professional practices or statistical reports from employees who are authorized to share this information or data in the normal course of their work. These persons are not considered to be participants within the meaning of the Policy if, and only if, apart from information of a public nature related to their employment, no other question relates to the respondent himself (ex: his/her opinions, his/her qualifications, his/her socio-demographic information, his/her personal experience at work or in any other sphere of his/her private life, his/her memories, etc.)”.

Following the CERULs directive, and as discussed with interviewees, this dissertation will make no mention of individual names to ensure their anonymity.

Survey: method and protocol

Field trip studies were critical to complete and fill the literature gaps though interviews and participant observation. The first step (December 2016 to March 2017) consisted of attempts to contact members of the government, research institutes and think tanks, and Japanese and arrange meetings either at their headquarters in Japan or at the premises of the Arctic Research Center of the University of Hokkaido. Japanese officials within the MoFA, MEXT, MITI and MLIT, research institutes and think tanks (NIPR, OPRI), and executives in Japanese companies such as MITSUI, Japan Gaz Company (JGC), or NEDO were contacted to build a sample constituent.

The second step consisted of designing a survey, both in English and in Japanese. Three surveys of 10 questions were developed to correspond to interviewee profiles: officials, business actors, and academics respondents. The surveys were designed as semi-structured interviews to have a set of similar questions to analyze. It also allowed respondents to add details or complementary information, should they felt necessary to do so. When asked, the surveys were sent by e-mail to the selected respondents in English and Japanese to facilitate comprehension and preparation. The interviews were conducted at the head office of the companies, ministries, and institutes concerned.

The first field trip in Japan was planned during this phase to maximize the number of interviews, participation in events and conferences, and visits of research institutes' infrastructures and develop an exchange network. Since Japanese society often operates through formal introductions, the conference's attendance inviting researchers, government officials, and Japanese companies to discuss issues related to the Arctic during the first days of this 2017 field trip helped break the ice and establish contacts. On this occasion, Dr. Ohnishi introduced the various members present, allowing me to exchange business cards (essential formality in Japan) to then make an appointment for interviews in the following weeks. He also helped to establish contact with members of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the years.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted during fieldtrips in Tokyo and Hokkaidō from February to May 2017, February 2019, and from September to December 2019 (internship in the Arctic Research Center, Hokkaido University) with national, regional, and local actors (government officials, port-authorities officer, researchers) involved the arctic region policy, arctic research or business activities. Several interviews were also conducted on the sidelines of international seminars and workshops. At the request of the interviewees, most of the interviews were not recorded. Instead, a pre-established grid for the interviews was used in order to transcribe as faithfully as possible the information transmitted during the interviews. Finally, questionnaires were sent to several officials that were not able to meet for interviews.

However, it should be noted that one of the difficulties encountered was the lack of interest shown by certain types of an actor to conduct an interview or even discussions, like business companies. Certain companies, contacted on several occasions and via various communication channels, did not respond to the requests. Several difficulties are inherent in conducting the interviews, such as the ability to remember events or partiality. Although the researcher did her best to remain objective throughout the process and tried not to formulate suggestive questions, there was certainly some partiality, particularly the conviction of the value of participation in international relations, the researcher being a student in this field. The interviewee's memories of events may also be affected by their emotions and experiences throughout their involvement. One of the main difficulties of this study is the extent and distance of the terrain that has led to the targeting of key events in Japanese Arctic life. The participation in international conferences on the Arctic was one of the privileged instruments to observe a new place of cooperation and meet its multiple actors. Participation in international conferences and workshops16 made it

possible to meet researchers, officials, politicians or international institutions, leading to informal discussions in a less strict framework than the interviews. Due to the specificity of Japanese culture and language favoring ambiguity (aimai / aimaina kotoba)17, many informal discussions and

16 Arctic Change 2017, Isar-5 Tokyo 2018, Model Arctic Council 2018, 34th International Symposium on the Okhotsk Sea &

Polar Oceans 2019, Korea Arctic Academy 2019, Thorvald Stoltenberg Conference on the Arctic in Asia and Asia in the Arctic: Opportunities and Challenges 2019, Arctic Frontiers 2020.

17 Also called kuuki yomenai (someone who has difficulty in reading social situations) highlighting the importance of

interviews took place outside the formal framework of offices or political corporate. It includes high arctic representatives of MoFA, representatives research international institutions, business companies’ managers.

Processing techniques and data analysis method

This article relies on the field's traditional research methods, such as the external and internal source criticism and contextualization of sources, i.e., the study of the information included about the source’s purpose and functional connections. This study also incorporates elements of the ‘entangled’ approach, emphasizing entangled processes rather than similarities and differences between separate entities, into the comparative design.

In this study, the qualitative approach was utilized to analyze the official declarations and communications to decipher better the strategies and objectives pursued in establishing and supporting Japan’s Arctic Policy. While leaning on the external and internal source criticism, contextualizing sources, and a systematic comparison, this study is based on extensive reading of English and Japanese (using translation tools) language materials. The analysis of primary sources is based on policy documents, official statements, declaration, and report such as the official Arctic policy of 2015, the Basic Plan on Ocean Policy (2008, 2013, 2018), the annual Diplomatic Bluebooks since 2011, reports from the Ocean Policy Research Institute (2015, 2017), and the ArCS project (2015; 2020). It includes publications from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' official websites or the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. It provided the necessary background for studying Japanese Foreign Policy, Arctic policy, research and economic policy, and subnational governance system. Comparative studies of national arctic policies, international activities of subnational government were used to contextualize this research. The secondary sources used show the multidisciplinary inclusion of this research.

The qualitative method also relies on the analysis of 25 interviews conducted between 2017 and 2019 using the software Nvivo. The qualitative method includes discourse analysis through a constructivist approach. Interview profile information was transcribed in a Word or Excel file, and if allowed, recorded. Following the completion of semi-directed interviews using the Grounded Theory Method (GTM), data were processed on a qualitative data approach to the synthesis of

speech (Lejeune 2019; Glaser and Strauss 2009; Guillemette 2006). It aims to empirically report on this "material" considering their feelings and understanding of the situation. The GTM can have its various phases (field phases and readings, descriptions and analyzes) tangled. This approach, focusing on the representation from the analysis of various protagonists and their arguments and views, is essential in geopolitics studies: it provides insight into the complex relationship of a group of actors with a territory (Lasserre, Gonon, and Mottet 2008).

The interviews were analyzed to understand the logic and reasoning by which an actor justifies its position, strategy, priorities, and choices. The primary and secondary data collected was coded in Nvivo to list and organize specific sentences, key-words, or paragraphs connected to the context of the analysis into meaningful units (DeCuir-Gunby, Marshall, and McCulloch 2011; Miles 1994). The set of concepts brought up in the survey were very limited and revolved around:

1. Policy initiatives (a. Ocean Policy, b. International and Arctic Regulation Framework including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the Polar Code, c. involvement of Think Tanks and lobbies),

2. International and regional cooperation (a. scientific & diplomatic, b. business cooperation through bi and multilateral cooperation agreements),

3. Security issues (a. Environmental Concerns, b. Energy security, c. Freedom of navigation, d. Territorial disputes in the arctic with the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, and outside with the Northern Territories dispute between Japan and Russia, and also the various territorial dispute in Asia).

This step, revisited several times during the analysis, allowed the development of a codebook, defined by DeCuir-Gunby, Marshall, and McCulloch (2011, 138), as a "set of codes, definitions, and examples used as a guide to help analyze interview data. Codebooks are essential to analyzing qualitative research because they provide a formalized operationalization of the codes". Later the authors underlined that data could be added, modified, and transformed during the coding process, which is constantly evolving as it is used, allowing the researcher to establish new connections between ideas and concepts.

During the analysis, it was clear that the data collected from diplomats and staff of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs should be taken with circumspection. Indeed, as argued by several researchers, information and individuals are strictly sequestered within Foreign Ministries, making it challenging to utilize standard research methods like participant observation and interviews (Kuus 2011; Tuathail 1999; Neumann and Sending 2010; Neumann 2002). According to Plouffe (2020, 79) “as objective reality does not exist in foreign policy behavior or, indeed, in international relations overall, scholars must recognize their own subjectivity in the conduct of their research”. This context leads this chapter to rely more heavily on published textual material (diplomatic statements, international agreements, official reports). To maintain consensus within the ministry and with others, diplomats must compromise in their discourses. The information thus obtained during interviews is extremely calibrated to reflect official statements. Hence, the first step to support the research hypothesis was to review and analyze government declarations found on official websites and media. Therefore, the use of statistical data has proved particularly interesting to analyze the Japanese government declarations concerning its Arctic shipping strategy, which gives a necessary background of the hypothesis verification.

Statistical data were drawn from both primary and secondary sources. From primary sources, it relies on the analysis of official documents, declarations, presentations of members of the Japanese government between 2011 and 2020. The quantitative method relies on secondary sources with data collected from academic papers, media material, memoirs, and other introspective sources. If these sources contain relevant information, their use requires prudence and discernment, mainly because of the biases which result from the partiality and sometimes militant positions of the consulted presses. Theoretical and methodological works were consulted and covered the International Relations, geopolitics, and other social sciences fields. From the first moments of this thesis project's design and all along with the project, this literature's consultation provided the necessary tools for establishing a theoretical, conceptual, and methodological framework and address the research question. The research question made it possible to elaborate four hypotheses, which are starting point of the verification-process. Through the presentation of the theoretical and conceptual framework, the dissertation will attempt to verify these research hypotheses. The conceptual framework of this essay is integrated directly into the chapters attached to it.

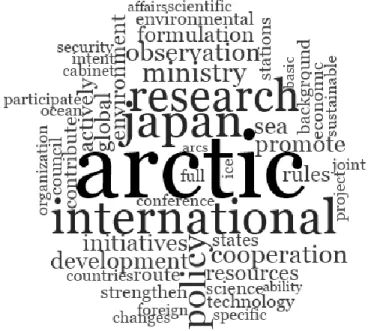

The NVivo software, designed to conduct qualitative and mixed methods analysis, was used to analyze Japanese-Arctic-related documents. This software helped organize, analyze and find insightful content among unstructured or qualitative data such as interviews, open survey responses, articles, social media, and web pages. To operationalize the corpus analysis, 50 groups of words and their related forms or lemmas were selected (e.g., sciences, scientists, scientific, scientifically, to be examined using Nvivo software. Pronouns and verbs have been redacted in order to highlight the main keywords. This analysis was used for exploratory purposes in order to bring out lexical tendencies. Through these methods (see Figure 2), we can observe that in the 2015 Arctic Policy, the most popular words revolve around International Cooperation, research activities, environmental protection and awareness issues, and development and use of the Arctic Sea Route. The use of the software consists of a quantitative dimension of the analysis. This software broadened the analysis because of the quantity of processed data where the non-software investigation could not have provided such in-depth results.

FIGURE 2: WORD CLOUD OF OCCURRENCE IN JAPAN OFFICIAL ARCTIC POLICY (2015). PERSONAL COMPILATION.

The second method used in the research is a comparative analysis to determining convergences and contradictions in the parts of the documents regarding the scientific research or economic cooperation. Textual markers were coded into broad categories and subdivided into political,

science diplomacy, and economic factors. These markers correspond to the theoretical framework's concepts and dimensions and are linked to elements drawn from the literature that we are trying to measure.

Following the presentation of the theoretical and methodological framework, research question, and hypothesis, this thesis proceeds in three chapters, followed by a discussion presenting the research results.

![FIGURE 6: TRENDS FOR JAPAN’S SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY BUDGET BETWEEN FY2001 & 2019 [科学技術関係予算の推移]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/2750583.65443/107.918.91.749.110.395/FIGURE6TRENDSFORJAPANSSCIENCEANDTECHNOLOGYBUDGETBETWEENFY21amp219科学技術関係予算の推移.webp)