an author's

https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/26737

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2020.100029

Vieille, Benoit and Pujols Gonzalez, Juan-Daniel and Bouvet, Christophe and Breteau, thomas and Gautrelet,

Christophe Influence of impact velocity on impact behaviour of hybrid woven-fibers reinforced PEEK thermoplastic

laminates. (2020) Composites Part C: Open Access, 2. ISSN 2666-6820

Influence

of

impact

velocity

on

impact

behaviour

of

hybrid

woven-fibers

reinforced

PEEK

thermoplastic

laminates

B.

Vieille

a,∗,

J.-D.

Pujols-Gonzalez

a,

C.

Bouvet

b,

T.

Breteau

c,

C.

Gautrelet

da INSA Rouen, Groupe de Physique des Matériaux (UMR CNRS 6634), 76801 St Etienne du Rouvray, France

b Institut Clément Ader, Université de Toulouse, ISAE-SUPAERO – UPS – IMT Mines Albi – INSA - 10 av. E. Belin, 31055 Toulouse cedex 4, France c INSA Rouen, 76801 St Etienne du Rouvray, France

d INSA Rouen, Laboratoire de Mécanique de Normandie, 76801 St Etienne du Rouvray, France

Keywords: Impact velocity Thermoplastic composite Permanent indentation Charpy Drop tower Quasi-static indentation

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

This studyaimsat examiningtheimpactbehaviorof hybridcarbonandglassfiberswoven-plyreinforced PolyEtherEtherKetone(PEEK)thermoplasticquasi-isotropiclaminates.AninstrumentedCharpypendulumis specificallydesignedtoestimateitscapabilitytoperformlowvelocityimpacttests.Throughthecomparisonof differentimpactmethods(Quasi-staticindentationtests,Charpyanddroptowerimpacts),theinfluenceofimpact velocityontheimpactbehaviorofthishybridcompositematerialisinvestigated.Fromtheobtainedresults,it appearsthatthemacroscopicimpactresponseissimilarintermsofforce-displacementresponse.Indeed,the im-pactvelocityissignificantlyhigher(2.5timeshigher)withfallingweightimpacttesting.InPEEK-basedlaminates whosemechanicalbehaviouristime-dependent,slowloadingrates(e.g.Charpyimpacttesting)areinstrumental inrulingthedissipatedenergy(+20%at35and40J)aswellasinincreasingthepermanentindentation(1.6 timeshigher)thatisalwayshigherthantheBarelyVisibleImpactDamage.

1. Introduction

Theeffectsof impactonfiber-reinforcedcomposites iswidely ad-dressedintheliteratureandyetanalysingthephenomenonand relat-ingeffectstotheforcesactingandthematerials’properties,inorder topredicttheoutcomeofaparticularevent,canbeverydifficult[1]. Dependingontheimpactconditions,itusuallyresultsindeformation, permanentdamage,completepenetrationofthebodystruckor fragmen-tationoftheimpactingorimpactedbody,orboth.Forfibre-reinforced compositematerials,itispermanentdamage,possiblysubsurfaceand barelyvisible,penetrationandfragmentation,thatareofinterest.There arevariouswaysofanalysingtheimpactprocess;intermsoftheenergy depositedandgrossdamageproduced,microenergydissipationorby consideringthestressesactingonflawsinthematerialandtheeffects thataregenerated.Thelattermethod,whichisknownasfracture me-chanics,isextensivelyemployedwithmetalsbutwillonlybealludedto here.Inpractice,theimpactbehaviourofcompositesmergesintothe generalareaofdamagemechanics.

Therearemanyfactorsinfluencingtheimpactresistanceand dam-age tolerance of fiber-reinforced composites [2]: fibers architecture, resintoughness,hygrothermalandtemperatureconditions,stacking se-quence,fiberhybridization,matrixhybridization,impactor geometry

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:benoit.vieille@insa-rouen.fr(B.Vieille).

(size,shape,andmass),impact-loadingtype(monotonicorrepeated),or impactvelocity.Allthesefactorsmayruletheimpactbehaviourof com-positematerialsintermsofmacroscopicforce-displacementresponse, dissipatedenergy,impact-induceddamagemechanismsandpermanent indentation.

When itcomes tothe impact behaviour of composite laminates, theroleofthematrixisinstrumental;protectingthefibre,transferring stressesand,insomecases,alleviatingbrittlefailurebyproviding alter-nativepathsforcrackgrowth[1].Itisthereforerequiredtoevaluate theinfluenceofimpactvelocityonimpactresponseintermsof dissi-patedenergyaswellasimpact-induceddamages.Inapreviousstudy, impacttestswereperformedonhybridcarbonandglassfibers woven-plyreinforcedPolyEtherEtherKetone(PEEK)thermoplastic(TP) lami-natesusingadroptowersystemwitha16mmdiameter,2kgimpactor, complyingwiththerequirementsoftheAirbusIndustriesTestMethod (AITM1-0010)[3].Theeffectoftemperatureontheimpactbehaviour anddamagetoleranceofthiscompositematerial(samematerialasthe oneinvestigatedinthisstudy)wasexamined.Fromtheresults,it ap-pearsthatthesecompositematerialshaveaverygoodimpactbehaviour (highpermanentindentation,goodimpactdetectabilityandreduction delamination),andahighdegreeofdamagetolerance,evenat temper-aturesclosetotheirglasstransitiontemperatureTg.

Regardingcertificationofaircraftusingcompositestructures,critical componentsmustbefatiguetestedwithpreviously inflictedflawsto accountforaworst-casecondition[4].Impactdamageisonetypeof flawrequiredintestcomponentstosimulaterealworldimpactsduring themanufacturing,themaintenanceandoperationalphasesofaircraft life.

1.1. Low-velocityimpactbehaviourcharacterization

Impacttestingmachinesusuallyincludeverticaldroptowersand springloadedimpactguns.Verticaldroptowersarebulky,difficultto position,andbecauseoffreefallingimpactorsprovideinexactpointand shapeofimpact.Verticaldroptowerscannotbeusedwhenahorizontal impactingdirectionisrequired.Horizontalspringloadedimpactguns havedifficultywithcontainmentofthereactionforceaswellasdouble impactissues.Inaddition,theyaredifficulttobeinstrumented. Pendu-lumtypeimpactorsaretypicallyusedforCharpyandIzodsmallcoupon fatiguetesting.Theyarenotdesignedforimpartingimpactdamageon largeaircraftcomponents,andcannotbemanipulatedtospecific loca-tionsonthelargeairframestructures.

Thesevarioustypesofimpacttestingmachinesdifferfromone an-otherprimarilyintheshapeofthespecimen,inthewayinwhichthe specimenisheldatthemomentoffracture,andintheshapeofthe ham-merstrikingspecimen[5].TheIzodandCharpytestshavebeenusedfor manyyearstoassesstheimpactperformanceofmetalsparticularlywith respecttothebrittle/ductiletransitiontemperatureandnotch sensitiv-ity[1],butthedroptowerisstillthemostcommonlyusedtoconduct impacttestsoncompositelaminates[3,6].

Quasi-staticindentationtestsconductedonuniaxialtestingmachines arebasedonspecifictooling(indentorandsupportingframe).The ob-tainedresultsareusuallytreatedasverylowvelocityimpactswhen ex-aminingtheeffectofimpactvelocityondamageatalaterstage.When dynamiceffectsinthestructuredobecomeimportant,theimpactforce andtheresultingpeakvaluesofstressesandstrainsinthestructure typi-callybecomelargerthantheywouldbeforagivenimpactenergyunder quasi-staticloading[7].Comparedtothermosetting-basedcomposites, thesedynamiceffectsareexpectedtohaveasignificantinfluenceon theimpactbehaviourof thermoplastic-basedcomposites duetotheir time-dependentmechanicalbehaviors[8,9].

Mostof thestudiesdealingwiththeimpactbehaviourof thermo-plasticlaminatesareconductedbyusinganinstrumented,tailor-made, drop-weighttestrig[8–11].Theyarerestrictedtolowimpactvelocities buthighincidentkineticenergiesareachievedthroughtheuseofhigh masses.Impactvelocitiesregulatedbyselecteddropheightsusuallyvary between2m/sand8m/s.Theforce-displacementcurvesareclassically obtainedfromaloadsensorpositionedbetweentheimpactorheadand thedrop-weightbody.Inthecurrentstateoftheart,pendulum-type im-pactdevicesaremostlyusedtocarryoutdestructivetestingofmaterials onV-notchedspecimens.Thesearethependulumsforcarryingout char-acterizationsofmaterialsusingtheCharpymethod,whichmeasuresa specimen’sresistancetobreakagewhenitisimpactedusingapendulum withahammeratitstip.Thehammerisinstrumentedandthedeviceis equippedwithadataacquisitionsystem.

InstrumentedCharpypendulumimpacttestshavebeenconductedon V-notchedcompositespecimens[12–17].Earlyintheseventies,Adams etal.haveusedaninstrumentedCharpyimpact-testingmachine.They haveobservedthatthemaximumimpactforcesandtheimpact mod-uliweredetermined,andcomparedtothecorrespondingvaluesfrom quasi-statictests[17]. Themaximumforceis independentofloading rate,whiletheimpactmodulusissignificantlylessthanthestatic flexu-ralmodulus.Thevariouscompositeswerefoundtobeseverelydegraded bythelow-levelimpacts.Morerecently,aCharpypendulumwas mod-ifiedbyMeolaetal.toconductimpacttestsonrectangularspecimens [18,19].

Table1

AfewpropertiesofwovencarbonandglassfibersreinforcedPEEK elementaryplyatRT. Carbon/PEEK Glass/PEEK Ex (GPa) 60 22 Ey (GPa) 60 20 Gxy (GPa) 4.8 6.55 𝜈xy 0.04 0.04

Tensile strength (warp) (MPa) 963 1172 Compressive strength (warp) (MPa) 725 1103 Nominal ply thickness (mm) 0.31 0.08

Table2

Mechanical propertiesintensionandcompressionof unnotchedC/G/PEEKquasi-isotropiclaminatesatroom temperature.

Ex (GPa) 𝜎𝑥𝑢 (MPa) 𝜀 𝑢𝑥 (%)

Tension 52.57 ± 0.58 784 ± 22 1.52 ± 0.04 Compression 49.25 ± 0.50 573 ± 13 1.75 ± 0.07

1.2. Objectivesofthestudy

Through the comparison of low-velocityimpacts tests conducted withadroptowerandamodifiedCharpypendulum,thisworkaims at investigatingtheinfluenceofloadingconditions(impactvelocity) ontheimpactbehaviourofhybridthermoplasticlaminates.Theimpact behaviour willbe discussedintermsofmacroscopicimpactresponse (force-displacementcurve),dissipatedenergyandpermanent indenta-tion.Thetime-dependentbehaviourofthermoplastic-basedcomposites isexpectedtoreflectontheimpactbehaviourdependingonimpact ve-locity.Thediscussionwillbesupportedbymicroscopicobservationsof impactedspecimens.

2. Materialsandexperimentalset-up

2.1. Materialsandspecimen

Thecompositematerialsunderinvestigationconsistsof14 carbon-PEEK wovenplieswithtwoouterglass-PEEKwovenplieswhose aim istoprotectthecarboncore(electricalprotection)[3].Thelaminated platesaremadeupofcarbon(Tenax-EHTA403K)–PEEK5HS(Harness Satin)wovenplieswithaglass–PEEKplyoneachsurfaceandobtained bythermo-stampingprocess(Tables1and2).Thestackingsequenceis balancedandsymmetric(Fig.1):[(0/90)G,[(0/90),(±45)]3,(0/90)]s

(withGindexforglassfibersply).Thelaminatesaveragethicknessis about4.5mm.Testspecimensarerectangularplateswhosedimensions are150×100mm2cutbywaterjetfrom600×600mm2plates.Four

specimenswereimpactedatroomtemperaturewithfourdifferent im-pactenergiesrangingfrom25to40J.

2.2. Droptowerimpacttesting

Thereferenceresultsreferstoimpacttestsconductedonthesame compositematerialbymeansofadroptowerasdescribedindetailsin

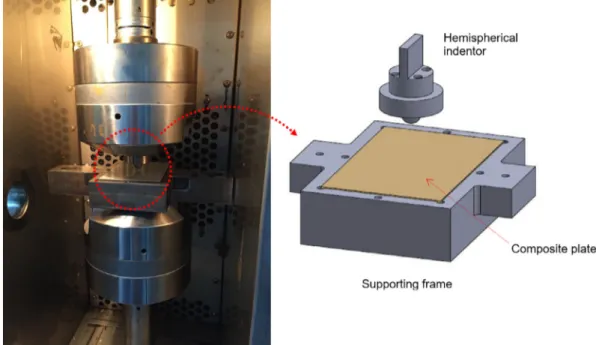

[3].Thesetestswereperformedusingadroptowersystemwitha16 mmdiameter,2kgimpactor,complyingwiththerequirementsofthe AirbusIndustriesTestMethod(AITM1-0010).Justbeforeimpactingthe specimen,anopticallasermeasurestheimpactvelocity.Apiezoelectric forcesensorisplacedinsidetheimpactortomeasurecontactforce dur-ingimpact.Therectangularspecimenwhosedimensionsare100×150 mm2issimplysupportedonaframe(Fig.2).

B. Vieille, J.-D. Pujols-Gonzalez and C. Bouvet et al.

Fig.1. Opticalmicrographofthelongitudinal sectionshowingthequasi-isotropicstacking se-quenceoftheC/G/PEEKlaminates.

Fig.2. Dimensionsofthesupporting frameusedfor drop-towerandCharpyimpacttesting[3].

Fig.3. Lowvelocityimpacttesting:(a)Charpypendulumandmeasurementdevices– (b)Partsdesign.

2.3. Charpyimpacttesting

The present testing device relates to impact testing machines, whereinthespecimenmeetstherequirementsoftheAirbusIndustries TestMethod(AITM1-0010).Specimensareimpactedbyaswinging pen-dulumhammerequippedwithahemisphericalindentor(Fig.3).This testingdeviceisanimprovementintheCharpypenduluminitialdesign. ThespecimensareusuallyV-notchedrectangularbeamsdesignedtobe strikedatthecenter.Apurposeofthedeviceistoproduceapendulum

foranimpacttestingmachineinwhichnoportionofthependulumis locatedbelowthestrikingsurface,sothattheproblemofinterferenceis greatlyreducedoreventotallyeliminated.Thisrequirementmustalso besatisfiedinordertomeetthestandardspecificationsoftheAmerican SocietyforTestingMaterialsforpendulum-typeimpacttestingmachines (ASTMSpecificationE-23).

IntypicalCharpypendulum-typeimpacttestingmachines,theabove requirementrelatingtothecenterofpercussionhasusuallybeenmet byconstructingthependulumintheshapeofalongthinstem,atthe

Fig.4. Experimentalset-upofthequasi-staticindentationtests.

lowerendofwhichaheavyheadisattached,theheadcontainingthe strikingsurface.Mostofthemassofthependulumisthusconcentrated inthehead.Onedisadvantageinsuchapendulumisthata consider-ableportionofthependulumheadmustbelocatedbelowthestriking surfaceinordertoplacethecenterofpercussionofthependulum ex-actlyatthecenterofthestrikingedge[5].Thisoftenproducesserious problemsofinterference,sincethetwopartsofthebrokenspecimen, beingprojectedoutafterthemomentofimpact,mayhitthelowerpart ofthehead,thuschangingtheenergyrelationsandproducingan erro-neoustestresult.FollowingtheideainitiallyproposedbyMeolaetal. [18,19],theimpacttestsperformedinthepresentworkaremainly in-tendedtoproduceVisibleImpactDamage(VID)orBarelyVisible Im-pactDamage(BVID)onlaminatedplatessupportedbyastandardized supportingframe(AITM1-0010),ratherthanacompletefractureofa specimen(Fig.2).Theimpactvelocityisestimatedfromthe fundamen-talprincipleofdynamics.Inordertoinvestigatetheimpactbehaviour ofC/G/PEEKlaminates,fourimpactenergies(25-30-35-40J)havebeen consideredtoeasethecomparisonwiththeresultsobtainedfrom im-pactsachievedusingthedroptower[3].

2.4. Quasi-staticindentationtests

Allthequasi-staticindentationtestswereperformedusinga100kN capacity loadcell of a MTS 810 servo-hydraulic testing machine in displacement-controlledmode(Fig.4).Thesetestsareconductedwith thesamesupportingframe,aswellasthesamehemisphericalindentor. Theapplieddisplacementloadingrateis1mm/min(1.67.10−5m/s).

2.5. Permanentindentationmeasurement

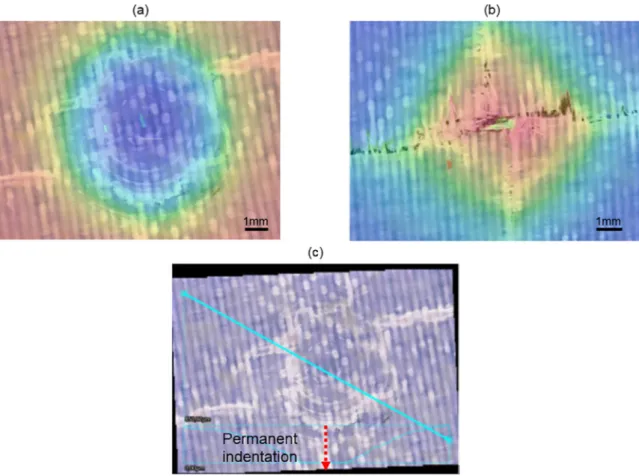

Themeasurementofthespecimen’spermanentindentationis typi-callyusedtoassesstheseverityofimpactdamage.Ingeneral,the in-dentationjustaftertheimpact(temporaryindentation),isalwayshigher thantheindentationafterrelaxationoftheimpactedcomposite.Such relaxationeffectsareneglectedafter48htogetthepermanent indenta-tion[20].AccordingtoAITM1-0010Airbusstandard,theBVID(Barely VisibleImpactDamage)isdefinedby0.6mmofindentationafter relax-ationofthestructureandwithoutbeingexposedtoanyhumidity[21]. Thepermanentindentationismeasuredusinga3DKeyenceoptical mi-croscope(Fig.5).

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. InfluenceofimpactenergyonCharpyimpactresponse

Lowvelocityimpactsareclassicallyconductedatdifferentimpact energiesinordertoevaluatethecapabilityofthecompositematerial todissipatetheimpactenergy(Fig.6a).Impactenergyisusually dissi-patedbydifferentmechanismsincludingdamageandlocalplastic defor-mationsofthepolymermatrix.Whensubjectedtolow-velocityimpacts, theelasticresponseobservedontheforce-displacementcurveappearsto beindependentfromtheimpactenergy(Fig.6b).Theresidual displace-mentincreaseswiththeimpactenergy.Itiswellcorrelatedtothe non-reversiblephenomena(damage,plasticity).Theoscillationsobservedon theforce-displacementcurvesareassociatedwiththenaturalmodesof vibrationoftheimpactingsystem(shaft,hammer,impactsensor).

Oncethelimitoftheelasticbehaviorisreached(atabout7kN), bothdamageandlocalplasticitycontributetothedissipationofimpact energy.Notsurprisingly,thedissipatedenergyincreasesalongwiththe impactenergy.Indeedhigherimpactenergyleadstohighermaximum displacementthatcomesalongwithmoresignificantdamageand plas-ticitywithinthelaminates.Thedissipatedenergyrepresents50%ofthe initial impactenergyat25J,and70%oftheinitialenergyfora40J impact.Asfarthetypicalimpactvariablesareconcerned(Table3),the maximum impactforce is virtuallythesameforall impactenergies, whereastheimpactvelocity(about2m/s)andthepermanent inden-tationincreaseby30%and60%,respectively.Itisworthnoticingthat thepermanentindentationishigherthantheBVID(0.6mm)forallthe impactenergiesapplied.

3.2. Influenceofimpactvelocityonmacroscopicimpactresponse

Quasi-static(QS)indentationtests areperformedtodevelopsome preliminaryunderstandingofimpactdamagecharacteristicsinamuch better controlledmanner [22]. Thisknowledgeof whattoexpect al-lowedtheimpactteststobe carriedoutmoreeffectively.Aspointed outpreviously,thequasi-staticresultsareusuallytreatedasverylow velocityimpacts(about10−5m/s)whenexaminingtheeffectofimpact

velocityondamageatalaterstage.Quasi-staticindentationtestsmake itpossibletoexaminetheinteractionoflocal indentationandglobal

B. Vieille, J.-D. Pujols-Gonzalez and C. Bouvet et al.

Fig.5. Microscopicobservationsofthecarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminatessubjectedtoa40Jimpact:(a)Impactedsurface– (b)Rearsurface – (c)Permanentindentationmeasurementfromtheindentationprofile.

Fig.6. Influenceofimpactenergyontheimpactresponseofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminates:(a)Impactenergyvstime– (b)Impactforce vsdisplacement.

Table3

Charpypendulumimpacttesting:influenceofimpactenergyonthemechanicalresponseofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminates.

Impact energy (J)

Maximum impact force (kN)

Time to peak force (s) Maximum displacement (mm) Energy dissipated during impact (J) Normalized dissipated energy (% of impact energy) Impact velocity (m/s) Permanent indentation (mm) 25 9.42 3.96.10 −3 5.24 12.0 48 % 1.96 0.66 29.9 9.60 4.09.10 −3 5.33 17.65 59 % 2.14 0.83 35.1 9.63 4.40.10 −3 6.28 22.7 65 % 2.32 0.92 40.6 9.86 4.54.10 −3 6.56 28.8 71 % 2.50 1.07

Fig.7.Influenceofloadingconditionsontheimpactresponseofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminatessubjectedtoa25Jimpact:(a)Impact forcevsdisplacement– (b)Impactenergyvstime.

Table4

Droptowerimpacttesting:influenceofimpactenergyonthemechanicalresponseofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminates.

Impact energy (J) Maximum impact force (kN) Time to peak force (s) Maximum displacement (mm) Energy dissipated during impact (J)

Normalized dissipated energy (% of impact

energy) Impact velocity (m/s) Permanent indentation (mm) 24.7 9.26 1.59.10 −3 4.61 13.0 53 % 4.88 0.36

29.4 9.44 1.66.10 −3 5.11 17.0 58 % 5.11 0.52

32.8 9.77 1.68.10 −3 5.58 17.8 54 % 5.62 0.58

39.7 10 1.78.10 −3 6.25 24.4 61 % 6.18 0.73

platedeflectionandits effectontheonsetofdamage,whichmaybe significantinthicklaminates[23].

Theloadingrateintermsofapplieddisplacementsignificantly dif-fersdependingontheimpactmethod(QS,Charpyordroptower im-pacts).Itgoesfrom1.67.10−5 m/s(QS)toafewm/sforCharpyand

droptowerimpacts.ThelaminatesmechanicalresponsetoQS indenta-tionischaracterizedbya25Jmechanicalenergy.Regardlesstheimpact velocity,itappearsthatQS,Charpyanddroptowerimpacttestshave virtuallythesameimpactmacroscopicbehaviour(Fig.7a)andthesame dissipatedenergy(Fig.7b)fora25Jimpactenergy.Inordertofacilitate thecomparisonbetweenthethreeloadingconditionscorrespondingto thesamemechanicalenergy(25J),timewasnormalized(Fig.7b).In spiteoftimenormalization,whencomparingtheQSindentationtest andtheimpacttests,asignificantoffsetappearsonthecurves represent-ingimpactenergyvsnormalizedtime.FortheCharpyanddroptower teststheimpactvelocityvariesfromimpactspeedtozero(atmaximum impactforce),andthenitbecomesnegativeduringthereboundofthe indentor;whereasforthequasi-statictestithasonly2values+v0and -v0.ThisexplainsthesignificantdifferenceinFig.7b.

Inthisstudy,foragivenmechanicalenergy(25J),thepermanent indentationresultingfromlow-velocityimpacttestsislowerthanthe oneresultingfromquasi-staticindentationtest.Thepermanent inden-tationresultingfromQSindentationisabout12%and100%higherthan theCharpyanddroptowerimpacts,respectively(Tables3and4).This paramountdifferenceshouldbediscussedconsideringthatimpact ve-locityis2.5higherindroptowertestingwithrespecttoCharpytesting fora25Jimpactenergy.Thisdifferencewillbefurtherinvestigatedin thenextsectionfordifferentimpactenergies.

Themacroscopicimpactbehaviours(force-displacementcurves)are similarforalltheimpactenergiesinvestigated(Fig.8).Inaddition,for agivenimpactenergy,shockwavesinducedbyimpactvelocitylead tooscillationsoftheimpactforcesignal.Droptowerimpactsare char-acterizedbyhigherimpactvelocities(about2-3timesashighasthe onesresultingfromCharpypendulum).Asaresult,theoscillationsare

morenoticeableonthecurvesoftheimpacttestsconductedonthedrop tower.

As far thetypical impact variables areconcerned (Table 3), the maximum impactforce is virtuallythesameforall impactenergies, whereastheimpactvelocity(about2m/s)andthepermanent indenta-tionincreaseby30%and60%,respectively.Thisresultconfirmsthat theimpact velocityplays asignificantroleintotheformationof the permanentindentation.Thiswillbespecificallydiscussedinthenext section.

3.3. Influenceofimpactvelocityondissipatedenergy

Thedissipatedenergyisaboutthesameforlowimpactenergies(e.g. 25and30J–Fig.9c–9d)butissignificantlyhigher(about20%)in lam-inatesimpactedwiththeCharpypendulumforhigherimpactenergies (35-40J–Fig.9a-9b).Indroptowerimpacttesting,thedissipated en-ergyrepresents50%oftheinitialimpactenergyat25J,and70%ofthe initialenergyfora40Jimpact(Fig.10a).InCharpyimpacttesting,the dissipatedenergyrepresentsabout50%oftheinitialimpactenergyat 25J,and60%oftheinitialenergyfora40Jimpact.Italsoappearsthat impactvelocitybeinghigherwithdroptowertesting;theimpact dura-tionatmaximumimpactforceisshorter(Tables3and4).Withrespect todroptowerimpacts,theratioofimpacttimeatpeakforceofCharpy impactsisconstant(about2.5).Thisvalueisconsistentwiththeratio oftheimpactvelocities.Theseresultssuggestthatsuperiorimpact en-ergiescomealongwithlocaltime-dependentdamagesthatultimately contributetotheformationofthepermanentindentation.

Thedissipatedenergy(about60%oftheinitialimpactenergy)does notsignificantlydependontheimpactvelocityinthecaseofdroptower impactsasitincreasesby17%fora27%increaseintheimpactvelocity (Fig.10a).InthecaseofCharpyimpacttesting,itrapidlygrowswith impactvelocitywith48%increaseofthedissipatedenergyforthesame increaseintheimpactvelocity(Fig.9a).

B. Vieille, J.-D. Pujols-Gonzalez and C. Bouvet et al.

Fig.8. Influenceofloadingconditionsontheforce-displacementresponseofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKlaminatesdependingonimpactenergy:(a)40J – (b)35J– (c)30J– (d)25J.

3.4. Influenceofimpactvelocityonpermanentindentation

Thepreviousresultssuggestthatimpactvelocityhasnosignificant influenceontheimpactmacroscopicbehaviour,butitcontributestoan increaseinboththedissipatedenergyandthepermanentindentationin proportionsdependingontestingmethod(Fig.10b).Themagnitudeof permanentindentationisoftheutmostimportanceregardingthe resid-ualmechanicalproperties ofimpactedlaminates[24]. Inthecaseof droptowertesting,a27%increaseintheimpactvelocitydoublesthe permanentindentation.InthecaseofCharpytesting,thesameincrease inimpactvelocityresultsina62%increaseinthepermanent indenta-tion.Itisalsoworthnoticingthatthepermanentindentationishigher thantheBVID(0.6mm)foralltheCharpyimpactenergies,andonlyin the40Jcasewiththedroptower.

WithrespecttoQStests,thepermanentindentationis10%and50% lowerforCharpyanddroptowerimpacts,respectively(fora25J im-pactenergy).Indeed,slowloadingconditionsarecharacterizedbymore permanentindentation.This resultis consistentwiththeconclusions drawnintheliterature[24–26].Foranimpactvelocityratioofabout2.5 (droptoweroverCharpyimpactvelocities),thepermanentindentation isabout40%lowerforagivenimpactenergy.Thus,itappearsthatthe permanentindentationisruledbytheimpactvelocityin thermoplastic-basedlaminatessubjectedtoagivenimpact energy.Itconfirmsthat thetime-dependentbehaviorofthermoplasticcompositessignificantly contributestothemodificationoftheirimpactbehaviour(fromthe per-manentindentationstandpoint)andtheirsubsequentdamagetolerance. AsalreadyobservedbyAbdallahetal.incarbonreinforced epoxy-basedlaminates(whosemechanicalbehaviorisusuallylesssensitive toloadingratesthanPEEK-basedlaminates),thedamagesinducedby impacttestsandquasi-staticindentationtestsaresimilarbutthe per-manentindentationsignificantlydiffersdependingon theimpact

ve-locity[25].Previoussectionhashighlightedtheutmostimportanceof loadingrate(orimpactvelocity)onthepermanentindentation.More specifically,aslowerimpactvelocityresultsinalargerpermanent in-dentation.Intheliterature,thisobservationisexplainedbythe differ-enceinthechronologyofdamagemechanismstakinginplacewithin thelaminatessubjectedtoslowerorfasterloadingrates.The impact-induceddamagesarethesameastheonesobservedduringdroptower impacttests[3],quasi-staticindentationtests(veryslowloadingrate) andCharpytestsarecharacterizedbydebrisresultingfromlocal dam-ageofthecompositeconstitutiveelements(brokenfibers,delaminated plies,matrixcracking,fibersbridging).Comparedtodroptower test-ing,thisdebris hasalotmoretimetomoveandtopositionitselfin thedelaminatedareasandthedifferentcracks.Asaresult,itprevents thecracksfromreclosingastheimpactdecreasesduringtheimpactor rebound[25].Ultimately,themechanismofdebrisformationandthe resultingblockingsystemareinstrumentalincreatingaBarelyVisible ImpactDamage(permanentindentation).Thisnon-reclosingofcracks isaverylocalphenomenonandultimatelyhaslittleeffectonthe macro-scopicimpactbehaviour.Astheseareinternalforcesconcentratedunder theimpactor,itreallyneedssignificantinternalforcestohavean ob-servableeffectontheexternalforce,andthusontheforce-displacement curves.

In hybrid carbon-glass reinforced PEEK laminates subjected to Charpyimpacts,themicroscopicobservationsclassicallyshowthatthe failuremechanismsaredifferentonimpactedandrearsurfaces(Fig.11). Theimpactedsurfaceischaracterizedbyacompressivefailureoffibers. Theimpactorleadstoalocalhemisphericalcrushing.Therearsurface showsacross-shapeddamageresultingfromthebreakageof0° and90° orientedfibers.Thelongitudinalandtransversecrackslengthincrease astheimpactenergyincreases.Thepresenceoffibersbridgingalongthe 0° and90° isalsotypicaloftheroleplayedbytheglassfibersreinforced

Fig.9. Influenceofloadingconditionsontheimpactenergy-timeresponseofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKlaminatesdependingonimpactenergy:(a)40J – (b)35J– (c)30J– (d)25J.

Fig.10. Influenceofloadingrate(impactvelocity)ontheimpactresponseofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminates:(a)Dissipatedenergyvs impactvelocity– (b)Permanentindentationvsimpactvelocity.

PEEKexternalplyinthetoughnessoftheC/G/PEEKhybridlaminates. Thisglassfibersbridgingisalsoinstrumentalinthereclosingofcracks astheelasticenergystoredintheouterpliesduringimpactloadingis partiallyrecoveredduringimpactunloading.Alongitudinalcutofthe specimensubjectedtoCharpyimpacts(40J)showsmeta-delamination undertheimpactedsurfaceaswellasverylocalizedmatrixcrackingand fiberbreakage(Fig.12).

Inspecimenssubjectedtodroptowerimpacts,impact-induced fail-uremechanismswerediscussedindetailsin[3].Theyaresimilar (meta-delamination,matrixcracking,fiberbreakage)totheoneobservedin Charpytesting(Fig.13).Asindicatedinthepreviousstudy, impacted-induceddamagesareverylocalizedandlimitedthrough-thethickness. WhencomparingCharpyanddroptowersimpacts,themaindifference

isthesignificantdelaminationobservedonatthevicinityoftherear surface.

4. Conclusions

Theimpactbehaviorofthickhybridcompositelaminatesconsisting ofaPEEKthermoplasticmatrixreinforcedbycarbonandglasswoven fabricswasaddressedinthiswork.Differentimpactexperimental meth-ods(quasi-staticindentation,Charpyanddroptowerimpacts)were in-vestigated.Thesemethodswerebasedonthesamehemispherical inden-torbutwerecharacterizedbydifferentloadingrates(orimpact veloci-ties).ACharpypendulumwasspecificallyadaptedwiththedesignofa

B. Vieille, J.-D. Pujols-Gonzalez and C. Bouvet et al.

Fig.11. Macroscopicobservationsof carbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcomposite lami-natessubjectedtodifferentimpactenergies:(a) Impactedsurface– (b)Rearsurface.

Fig.12. Longitudinalcutofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminatessubjectedtoaCharpypendulum40Jimpact:observationofdelamination undertheimpactedsurfaceandbreakageof0° carbonfibersinconsecutiveplies.

Fig.13. Longitudinalcutofcarbon-glassfibersreinforcedPEEKcompositelaminatessubjectedtoadroptower40Jimpact:observationofdelaminationunderthe impactedsurfaceandbreakageof0° carbonfibersinconsecutiveplies[3].

hammerequippedwithaninstrumentedhemisphericalindentoranda supportingframe.

Oneofthemainpurposesofthisstudywastocomparetheinfluence ofimpact loadingconditionsandmorespecificallytheimpact veloc-ityontheimpactbehaviorofthermoplastic-basedcompositelaminates thatisusuallyquantifiedbythefollowingcharacteristics:macroscopic mechanicalresponse(force-displacementcurve),total impactenergy, dissipatedenergyandpermanentindentation.

Whenapplyingagiven impactenergy,these impact methodsled tosimilarimpactbehaviorsintermsofforce-displacementcurvesand dissipatedenergy.However,theresultingimpactvelocitysignificantly varied:afew10−5m/sinQStests,about2m/sinCharpytestsand5-6

m/sindroptowertests.Inaddition,thepermanentindentation associ-atedwithimpact-induceddamagessignificantlydifferedasitappeared toberuledbytheimpactvelocity.Higherimpactvelocitiesresultedin lowerpermanentindentationindroptowerimpacts(about40%lower thantheCharpyimpactvalues).Atthesametime,theimpactvelocity was2.5higherfordroptowerimpactswithrespecttoCharpyimpacts fordifferentimpactenergies.

Theobtainedresultssuggestedthatsuperiorimpactenergiescame alongwithlocaltime-dependentdamagesthatultimatelycontributed totheformation ofthe permanentindentation. Quasi-static indenta-tiontests(veryslowloadingrate)werecharacterizedbydebris,which wereexplainedbythefactthatthedurationofquasi-staticindentation testswerelongerthantheimpactones(Charpyanddroptower).Asa result,thedebrisformedbyimpact-induceddamageshadmoretime tomoveandtopositionthemselvesinthedelaminatedareasandthe differentcracks.Ultimately,itpreventedthecracksfromreclosingas theimpactforce decreasedduringtheimpactorrebound.Charpy im-pacttesting thereforeled topermanentindentationvalues thatwere alwayshigherthantheBarelyVisibleImpactDamage(0.6mmof perma-nentindentation)whoseroleiscriticalinlaminatedcompositesdamage tolerance.

Finally,theinstrumentedCharpypendulumisanalternativeto hori-zontalimpactdevicestocharacterizethelow-velocityimpactbehaviour of laminatedcomposites as theseverity of permanentindentationis greater.FurtherinvestigationsarerequiredtocomparetheCAI resid-ualstrengthoflaminatessubjectedtoCharpyimpactswithrespectto droptowerimpacts.

DeclarationofCompetingInterest

None.

References

[1] Edited by N.L. Hancox , An overview of the impact behaviour of fibre-reinforced composites, in: S.R. Reid, G. Zhou (Eds.), Impact Behaviour of Fibre-Reinforced Composite Materials and Structures Woodhead Publishing Ltd and CRC Press LLC, CambridgeEngland, 2000. Edited byCB1 6AH .

[2] S.Z.H. Shah , S. Karuppanan , P.S.M. Megat-Yusoff, Z. Sajid , Impact resistance and damage tolerance of fiber-reinforced composites: a review, Compos. Struct. 217 (2019) 100–121 .

[3] N. Dubary , G. Taconet , C. Bouvet , B. Vieille , Influence of temperature on the impact behavior and damage tolerance of hybrid woven-ply thermoplastic laminates for aeronautical applications, Compos. Struct. 168 (2017) 663–674 .

[4] K.T. Howie , Mobile bipendulum impact test machine, Publication n° US 2019/0003942 A1, 3, United States Patent Application Publication, 2019 , patented in Jan. .

[5] D.W. Pessen. Pendulum impact tester. United States Patent Office. Publication n°3,285,060, patented in Nov. 15, 1966.

[6] J. Liu , C.K. H.Liu , X. Kong , Y. Ding , H. Chai , B.R.K. Blackman , A.J. Kinloch , J.P. Dear , The impact performance of woven-fabric thermoplastic and thermoset composites subjected to high-velocity soft- and hard-impact loading, Appl. Compos. Mater. 26 (2019) 1389–1410 .

[7] Edited by S.R. Swanson , Elastic impact stress analysis of composite plates and cylin- ders, in: S.R. Reid, G. Zhou (Eds.), Impact Behaviour of Fibre-Reinforced Compos- ite Materials and Structures Woodhead Publishing Ltd and CRC Press LLC, Cam- bridgeEngland, 2000. Edited byCB1 6AH .

[8] B Vieille , VM Casado , C Bouvet , About the impact behavior of woven-ply carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastic- and thermosetting-composites: a comparative study, Compos. Struct. 101 (2013) 9–21 .

[9] B Vieille , VM Casado , C Bouvet , Influence of matrix toughness and ductility on the compression-after-impact behavior of woven-ply thermoplastic- and thermosetting– composites: a comparative study, Compos. Struct. 110 (2014) 207–218 .

[10] M.E. Kazemi, L. Shanmugam, Z. Li, R. Ma, L. Yang, J. Yang, Low-velocity impact behaviors of a fully thermoplastic composite laminate fabricated with an innovative acrylic resin, Compos. Struct. (2020), doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112604 . [11] A. Calzolari , M. Tommasone , M. Zanetti , M. Regis , F. D’Acierno , Impact charac-

terization of polymer composites based on PEEK and carbon fibers, in: Proceed- ings of the16th European Conference on Composite Materials, Seville, Spain, 2014, pp. 22–26 .

[12] R. Chaouadi , A. Fabry , On the utilization of the instrumented Charpy impact test for characterizing the flow and fracture behavior of reactor pressure vessel steels, in: D. François, A. Pineau (Eds.), From Charpy to Present Impact Testing, Elsevier, 2002, pp. 103–117 .

[13] M.A. Caminero , G.P. Rodriguez , V. Munoz , Effect of stacking sequence on Charpy impact and flexural damage behavior of composite laminates, Compos. Struct. 136 (2016) 345–357 .

[14] O. De Almeida , J.-F. Ferrero , L. Escalé, G. Bernhart , Charpy test investigation of the influence of fabric weave and fibre nature on impact properties of PEEK-reinforced composites, J. Thermoplastic Compos. Mater. 32 (6) (2019) 729–745 .

[15] W. Hufenbach , F. Marques Ibraim , A. Langkamp , R. Böhm , A. Hornig , Charpy im- pact tests on composite structures – An experimental and numerical investigation, Compos. Sci. Technol. 68 (2008) 2391–2400 .

[16] M. Nagai , H. Miyairi , The study on Charpy impact testing method of CFRP, Adv. Compos. Mater. 3 (3) (1994) 177–190 .

[17] D.F. Adams , J.L. Perry , Low level Charpy impact response of graphite/epoxy hybrid composites, J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 99 (3) (1977) 257–263 .

[18] C. Meola , S. Boccardi , G.M. Carlomagno , N.D. Boffa , F. Ricci , G. Simeoli , P. Russo , Impact damaging of composites through online monitoring and non-destructive eval- uation with infrared thermography, NDT & E Int. 85 (2017) 34–42 .

[19] S. Boccardi , N.D. Boffa , G.M. Carlomagno , C. Meola , F. Ricci , Visualization of impact damaging of carbon/ epoxy panels, AIP Conf. Proc. 1736 (2016) 020124 .

[20] L.A Berglund , Thermoplastic resins, in: ST Peters (Ed.), Handbook of Composites editor, Chapman & Hall, London, 1998 .

[21] A. Tropis , M. Thomas , J.L. Bounie , P Lafon , Certification of the composite outer wing of the ATR72, J. Aero Eng. 209 (1994) 327–339 .

[22] N. Jones , Quasi-static analysis of structural impact damage, J. Construct. Steel Res. 33 (3) (1995) 151–177 .

[23] M.A. Kumar , A.M.K. Prasad , D.V Ravishankar , Effect of quasi-static loading on the composite laminates, Adv. Eng. Forum 20 (2017) 10–21 .

[24] S. Abrate , Impact on Composite Structures, Cambridge Press University, 1998 .

[25] E.A. Abdallah , C. Bouvet , S. Rivallant , B. Broll , J-J. Barrau , Experimental analysis of damage creation and permanent indentation on highly oriented plates, Compos. Sci. Technol. 69 (7–8) (2009) 1238–1245 Issues .

[26] N. Hongkarnjanakul , C. Bouvet , S. Rivallant , Validation of low velocity impact mod- elling on different stacking sequences of CFRP laminates and influence of fibre fail- ure, Compos. Struct. 106 (2013) 549–559 .

![Fig. 2. Dimensions of the supporting frame used for drop- drop-tower and Charpy impact testing [3] .](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/2944830.79555/4.892.59.795.372.916/fig-dimensions-supporting-frame-tower-charpy-impact-testing.webp)