ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Behavioural

Brain

Research

j o ur na l h o me p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / b b r

Research

report

Dawn

simulation

light

impacts

on

different

cognitive

domains

under

sleep

restriction

Virginie

Gabel

a,∗,

Micheline

Maire

a,

Carolin

F.

Reichert

a,

Sarah

L.

Chellappa

a,b,

Christina

Schmidt

a,

Vanja

Hommes

c,

Christian

Cajochen

a,

Antoine

U.

Viola

aaCentreforChronobiology,PsychiatricHospitaloftheUniversityofBasel,4012Basel,Switzerland bCyclotronResearchCenter,UniversityofLiège,Liège,Belgium

cITVitaLightI&DPCDrachten,PhilipsConsumerLifestyle,theNetherlands

h

i

g

h

l

i

g

h

t

s

•Weinvestigatedmorninglighteffectsoncognitionafteranightofsleeprestriction.

•Morninglighteffectsdependoncognitivedomain.

•Morninglighteffectsdependonindividualperformancelevels.

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received21October2014 Receivedinrevisedform 15December2014 Accepted19December2014 Availableonline27December2014

Keywords:

Dawnsimulationlight Sleeprestriction Cognitiveperformance

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Chronicsleeprestriction(SR)hasdeleteriouseffectsoncognitiveperformancethatcanbecounteracted

bylightexposure.However,itisstillunknownifnaturalisticlightsettings(dawnsimulatinglight)can

enhancedaytimecognitiveperformanceinasustainablematter.

Seventeenparticipantswereenrolledina24-hbalancedcross-overstudy,subsequenttoSR(6-hof

sleep).Twodifferentlightsettingswereadministeredeachmorning:a)dawnsimulatinglight(DsL;

polychromaticlightgraduallyincreasingfrom0to250lxduring30minbeforewake-uptime,withlight

around250lxfor20minafterwake-uptime)andb)controldimlight(DL;<8lx).Cognitivetestswere

performedevery2hduringscheduledwakefulnessandquestionnaireswerecompletedhourlytoassess

subjectivemood.

Theanalysesyieldedamaineffectof“lightcondition”forthemotortrackingtask,sustainedattention

toresponsetaskandaworkingmemorytask(visual1and3-backtask),aswellasfortheSimpleReaction

TimeTask,suchthatparticipantsshowedbettertaskperformancethroughoutthedayaftermorningDsL

exposurecomparedtoDL.Furthermore,lowperformersbenefitedmorefromthelighteffectscompared

tohighperformers.Conversely,nosignificantinfluencesfromtheDsLwerefoundforthePsychomotor

VigilanceTaskandacontraryeffectwasobservedforthedigitsymbolsubstitutiontest.Nolighteffects

wereobservedforsubjectiveperceptionofsleepiness,mentaleffort,concentrationandmotivation.

Ourdataindicatethatshortexposuretoartificialmorninglightmaysignificantlyenhancecognitive

performanceinadomain-specificmannerunderconditionsofmildSR.

©2014ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

Abbreviations: NIF,Non-ImageForming;fMRI,functionalMagneticResonance Imaging;SR,sleeprestriction;DsL,Dawnsimulationlight;DL,dimlight;MTT, MotorTrackingTask;DSST,DigitSymbolSubstitutionTest;PVSAT,PacedVisual SerialAdditionTask;simRT,SimpleReactionTimeTask;SART,SustainedAttention toResponseTask;PVT,PsychomotorVigilanceTask;V1-V2-V3,1,2,3-back:Visual N-backTask;SC,superiorcolliculus.

∗ Correspondingauthorat:PsychiatricHospitalofUniversityofBasel,Centrefor Chronobiology,WilhelmKlein-Strasse27,CH-4018Basel,Switzerland.

Tel.:+41613255908;fax:+33676211028. E-mailaddress:Virginie.gabel@upkbs.ch(V.Gabel).

1. Introduction

Numerousfactorscaninfluencecognitiveperformance,chief

amongthemaretheimpactoftimeofday[1,2]andhomeostatic

sleep pressure [3]. Chronic sleep restriction (SR) has

deleteri-ouseffects not onlyondaytimealertnessbut alsooncognitive

performance[4,5].

Indeed, sleepdisruptionresultsin specific cognitive

impair-ments including deficits in attention, executive function,

non-declarative and declarative memory, as well as emotional

reactivityandsensoryperception[6–8].Somestudiesshowthat

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.043

light exposure can act as countermeasure for these cognitive

impairmentsinhumans[9,10].

Theseacute impacts of light areusually referred toas

non-visual (or Non-Image Forming – NIF) effects, since they drift

apartfromclassicalinvolvementofrodandconephotopigments

in visual responses to light. NIF light effects at shorter

wave-length via novel photoreceptors containing the photopigment

melanopsinappeartostronglyimpactthehumancircadiantiming

system[11,12].Behaviouralresponsestriggeredbylight

encom-passimprovedalertnessandperformance,asindexedbyspecific

corticalresponsestocognitivetasksinPhotonEmission

Tomogra-phyandfunctionalMagneticResonanceImaging(fMRI)techniques

[13].However,dosage(intensityandduration),timingand

wave-lengthoflightfordomesticuseandintheworkplaceenvironments

aredifficulttodefineandmaycriticallydependonenvironmental

andtheindividualfactors.

Inapreviousstudy,wehaveshownthatexposuretogradually

increasinglightpriortoawakeningcancounteractsleep

restric-tioneffectsonwell-beingandcognitiveperformanceacrossthe

day,leadingtoanoptimizedlevelofalertness,whichimpingeson

enhancedperformanceonspecificcognitivetaskstightlyrelatedto

sustainedlevelsofattention[14].

Mostoftheeffectswerevisibleonthefirstdayafterthesleep

restrictionnightbutnotontheseconddayaftertwonightsofsleep

restriction,mostlikelyduetotheincreaseinsleeppressure.

Theoverallaimofthepresentstudywastoinvestigatewhether

dawnsimulationlightfollowingsleeprestriction,enhances

perfor-manceaccordingtocognitivedomainandwhethertheseeffectsare

sustainedduringtheentireday.

2. Materialandmethods

2.1. Studyparticipants

Studyvolunteerswererecruitedthroughadvertisementsat

dif-ferentlocaluniversitiesandwebsitesinSwitzerland,Germanyand

France.Screening procedurebegan witha telephoneinterview,

involvingadetailedstudyexplanation.Allparticipantsgavewritten

informedconsentbeforethestartofthelaboratorypart.Study

pro-tocol,screeningquestionnairesandconsentformswereapproved

bythelocalethicscommittee(EKBB/EthikkommissionbeiderBasel,

Switzerland)andconformedtotheDeclarationofHelsinki.

Allapplicantscompletedquestionnairesabouttheirsleep

qual-ity,lifehabitsandhealthstate.Thesequestionnairescompriseda

consentform,a generalmedicalquestionnaire,BeckDepression

InventoryII[15], EpworthSleepinessScale [16], Horne Ostberg

MorningnessEveningnessQuestionnaire[17],MunichChronotype

Questionnaire[18]and PittsburghSleepQualityIndex.Potential

candidateswitha PittsburghSleepQualityIndexscore>5were

excludedfromparticipation[19].Furtherexclusioncriteriawere

smoking,medicationordrugconsumption,bodymassindex<19

and>28,shiftworkandtransmeridianflightswithinthelastthree

months,aswellasmedicalandsleepdisorders.Sinceourstudy

pro-tocolincludedtwonightsofpartialsleeprestriction(restrictionto

6-h),wealsoexcludedparticipantswithhabitualsleepdurations

<7-hand>9-h[20],tominimizeapossibleconfoundingeffectsof

sleepduration.

Eighteenyoungmen(20–33yearsold;mean+StandardErrorof

Mean:23.1+.8)fulfillingallthecriteriawereenrolledinthestudy.

Acomprehensivetoxicologicalanalysisofurinefordrugabusewas

carriedoutbeforethestudy,alongwithanophthalmologic

exam-inationtoexcludevolunteerswithvisualimpairments.

Oneweekbeforethestudy,participantswerenotallowedto

drinkexcessivealcohol, and toconsumecaffeine orcacao

con-tainingdrinksormeals(atmost5alcoholicbeveragesperweek,

and 1cupof coffee or1caffeine-containing beverageperday).

Theywerealsoinstructedtokeeparegularsleep-wakeschedule

(bedandwaketimeswithin±30minofself-selectedtargettime).

Compliancetothisoutpatientsegmentofthestudywasverified

by wristactigraphy(actiwatchL, Cambridge Neurotechnologies,

Cambridge,UK)andself-reportedsleeplogs.

Thestudywascarriedoutduringthewinterseason(January

to March) in Basel, Switzerland, and comprised two segments,

distributedinabalancedcross-overdesign,separatedbyatleast

1-weekinterveningperiod.Thevolunteersreportedtothe

Cen-treforChronobiologyatthePsychiatricHospitaloftheUniversity

ofBaselontwooccasions(controlconditionandoneexperimental

conditions),wheretheystayedinindividualwindowlessbedrooms

withnoinformationabouttimeofday.Sincewedidnotfind

signif-icanteffectsoncognitiveperformanceneitherafterthebluelight

exposurenoraftertheDsLexposureafterthesecondnightofsleep

restriction,wedecidedtofocushereonthefirst24-hofthecontrol

conditionandtheDsLcondition.Themostlikelyexplanationwas

thatsleeppressurewastoohighafterthesecondnightofsleep

restriction, and thusthemorning lightcouldnot counteractits

Fig.1. (A)Protocoldesign.Twoarmsofa6-hsleeprestrictedprotocolwith dif-ferentmorninglightexposures.Elapsedtimeindicationisrelativetoanarrivalin thelabat8p.m.Time-of-dayindicationvariedacrossallsubjectsbutwasgiven inthefigureasanexample(takenfromthemeanofthesleep/waketimefromall participants).(B)Morninglightdevice.Spectralcomposition(lightwavelengthby irradiance(W/m2nm))oftheDawnSimulationLightat5min(greysolid),15min (greydash),24min(blacksolid)and30min(blackdash).

detrimentaleffect.Formoredetails,referredtoGabeletal.[14].

These24-hincludethefirstsleeprestrictionnight(6-h)at0lx

start-ingatthesubject’shabitualsleeptimeandfollowedby18-hof

datarecordingduringwakefulness.Duringtheday,inboth

condi-tions,participantswereexposedtodimlight(<8lx)during2-hafter

wake-upandto40lxfortheremainderofthedayuntiltheywent

tobed(Fig.1A).Inbothconditions,theinvestigatorenterstheroom

inthemorning,6-hafterlightoff,towake-uptheparticipants.

Thelight treatmentwasadministeredafterthesleep

restric-tionnighteitherwithnoadditionallightforthecontrolcondition

orwithaDawnSimulationLight(DsL:LEDprototypeofPhilips

Wake-upLightHF3520,PhilipsDrachten,TheNetherlands)

(poly-chromaticlightgraduallyincreasingfrom0to250lxduring30min

beforewake-uptime;thelightremainsaround250lxfor20min

afterwake-uptime),placed nearthebedateyes level(Fig.1B).

One participant could not be included in the analysis because

ofpoorqualityoftheelectroencephalogramrecordingsand

non-complianceduringcognitivetesting.Theremaining17volunteers

underwentbothlightconditionsinabalancedcross-overdesignas

follows:DL–DsLforninevolunteersandDsL–DLforeight.

2.2. Assessmentofsubjectiveratings

Subjectivesleepinesswasassessed everyhourwitha Visual

AnalogueScale(100mmscale).Likewise,aftereverytestsession

participanthadtoindicatetheeffort,concentrationandmotivation

theyneededtoperformthetests.A100mmeffortvisualanalogue

scalewasused,rangingfrom“0:little”to“100:much”[21,22].

2.3. Cognitiveperformance

Alltestswereadministeredevery2hduringwakefulness,

start-ing30minafterwakeup.ThetestbatterycomprisedtheMotor

TrackingTask(MTT),DigitSymbolSubstitutionTest(DSST)[23],

PacedVisualSerialAdditionTask(PVSAT)[24,25],Sustained

Atten-tionto ResponseTask(SART) [26],Psychomotor VigilanceTask

(PVT)[27],SimpleReactionTimeTask(simRT)andVisualN-back

Task(1,2,3-back)[28].For detailedinformation abouteach test,

pleaseseeTable1.

Alltheresultsaregivenrelativetoelapsedtimeafterwake-up

fromrestrictedsleeptakenat6a.m.Time-of-dayindicationwas

alsoaddedtobemoreinformativeandunderstandableforgeneral

public;itisanexamplecalculatedwiththemeanoftheparticipants

sleep/wakecycle,astheydidnothavethesamescheduledtime.

2.4. Statisticalanalysis

Forallanalyses,thestatisticalpackageSAS (version9.1;SAS

Institute,Cary,NC,USA)wasused.Statisticalanalyseswerecarried

outforeachvariable(subjectivefatigue,motivation,concentration,

effort,PVT,MTT,DSST,SimRT,SART,PVSATandN-Back)separately

withthemixed-modelanalysisofvarianceforrepeatedmeasures

Table1

Descriptionofthetasksinthecognitivetestbattery.

Tests Cognitivedomain Explanationofthetests References

MotorTrackingTask(MTT) Peopleneedtotrackacomputer-generateddiscusingthe mouse,alonganothercomputer-generatedpointfor20s DigitSymbolSubstitution

Test(DSST)

Computer-based“cognitive throughput”task(orattention-based task)measuringclericalspeedand accuracy.Thetaskbecomesless sensitivetochangesinattentionand moresensitivetomemoryimpairment.

Participantsarerequiredtoselectapredefineddigitin responsetoeachappearanceofanabstractsymbol(thekey linkingsymbolsanddigitsareavailableonscreenthroughout testing).Theylearnthecodingrelationshipsaftersome experience.Inthispacedversionofthetask,8symbolsare presentedfor500ms,withanISIof1500ms.Eachsymbol occuranequalnumberoftimes.

Asteretal.[23]

PacedVisualSerial AdditionTask(PVSAT)

Additiontaskheavilydependenton frontalbrainregions,involving executiveaspectsofworkingmemory

Singledigits(1to9)appearonscreenandeachmustbeadded tothedigitwhichprecededit,andtheresultingansweris selectedfromanon-screennumericalkeypad(“sum”of adjacentpairs,notatotalacrossalldigitspresented).Digits wereseenfor1000ms,withinter-stimulusinterval(ISI)of 2000msinbetween.

Feinsteinetal.[24]; Nagelsetal.[25]

SustainedAttentionto ResponseTask(SART)

Sustained/dividedattentiontaskin whichinattentionandinhibitory processingcanbemeasured separately.Bothtypesofperformance dependonthefrontalcortex

It’sacomputer-basedtask,usedhereasaGo/NoGotask,which requiresparticipantstomonitorsingledigitspresentedrapidly onscreen,andrespondtoeachonethatappears(calledGo target),exceptforaparticularpre-defineddigit(calledNoGo target).Digitsarepresentedfor1000ms,withaninter-item intervalof2000ms,with15“targets”(whereresponsesare withheld)randomlyinterspersedwith25distractors.

Robertsonetal.

[26]

Psychomotorvigilancetask (PVT)

Sustainedattentiontask,sensitiveto circadianvariationandsleeplossItis anapproachofDinges(Dinges,Pack etal.,1997).

ThePVTinvolvesa5-minvisualreactiontime(RT) performancetestinwhichthesubjectisrequiredtomaintain thefastestpossibleRT’stoasimpleauditorystimulus.Data analysesfocusonRT,errors,andsignaldetectiontheory parameters.

Dingesetal.[27]

SimpleReactionTimeTask (simRT)

Indicatorofspeededmotor performance.

Varyasafunctionofalertnessand sleepdeprivation

Thistaskrequirespeopletorespond,asquicklyaspossible,toa single,predictablestimulus.Theparticipantrestshis/herindex fingeronamouse,andhavingdonesooverthenext1000msa wordsuchas“Now!”appears,atwhichpointtheparticipant movesthecursortoadesignatedtargetposition.Thetime takenfromNow!Totheonsettomovethecursorfromthe restingpositionreflectstheparticipants’abilitytodetectthata responseisrequired,and,togetherwiththesubsequenttime takentomovethemousetothetargetposition,giveustheRT. VisualN-backTask

(1,2,3-back)

Executiveaspectsofworkingmemory Stimuliarepresentedindividuallyonacomputerscreen,and theparticipantmustindicate(usingthemouse),ifthecurrent stimulusandthenstimulipriortoitmatch.Thehigherthen, thestrongerarethedemandsofexecutivefunctioning.Stimuli arepresentedfor500mswithanISIof1500ms.Theratio betweenmatchtonon-matchtrialsisof1:2with30items.

Table2

Resultsoftheanalysisofthevariancefordifferentvariablesofsubjectivefeelingforthetimecourseofthestudy. Variable Analysisofthevariance

Light Timeofday Light×Time

Effort F1,254=0.14,p=.7059 F8,254=1.21,p=.2927 F8,254=51,p=.8485

Concentration F1,254=.69,p=.4061 F8,254=1.42,p=.1877 F8,254=1.08,p=.3806

Motivation F1,254=2.87,p=.0913 F8,254=1.56,p=.1377 F8,254=.45,p=.8927

Fatigue F1,254=00,p=.9996 F8,254=4.28,p<.0001 F8,254=1.07,p=.3830

(PROCMIXED),withwithinfactors“lightcondition”(dimlight[DL]

versusdawnsimulationlight[DsL])and“time-of-day”(allassessed

timepoints).

Afurtheranalysisincludedthefactor“group”wasdone,

accord-ingtothesubject’sperformanceonthe3-backtask.Asthisworking

memoryparadigmpresentsarelativelyhighcognitiveloaditmight

besuitabletodifferbetweenhighandlowperformers.Thus,we

performedamediansplitandconsideredsubjectspresenting

per-formancesbelowthemedianoftheoverallgroupaslowperformers

(N=9)andthoseaboveashighperformers(N=8).

3. Results

3.1. Assessmentofsubjectiveratings

Nosignificantdifferenceswerefoundbetweenlightconditions

for effort,concentration andmotivation neededtoperformthe

tasks.Similarly,subjectivesleepinessinducedbythetestdidnot

differacrossthelightconditions(Table2).Fordetailedinformation

onsleepiness,well-beingandmood,pleasesee[14].

3.2. Cognitiveperformance

3.2.1. MTT

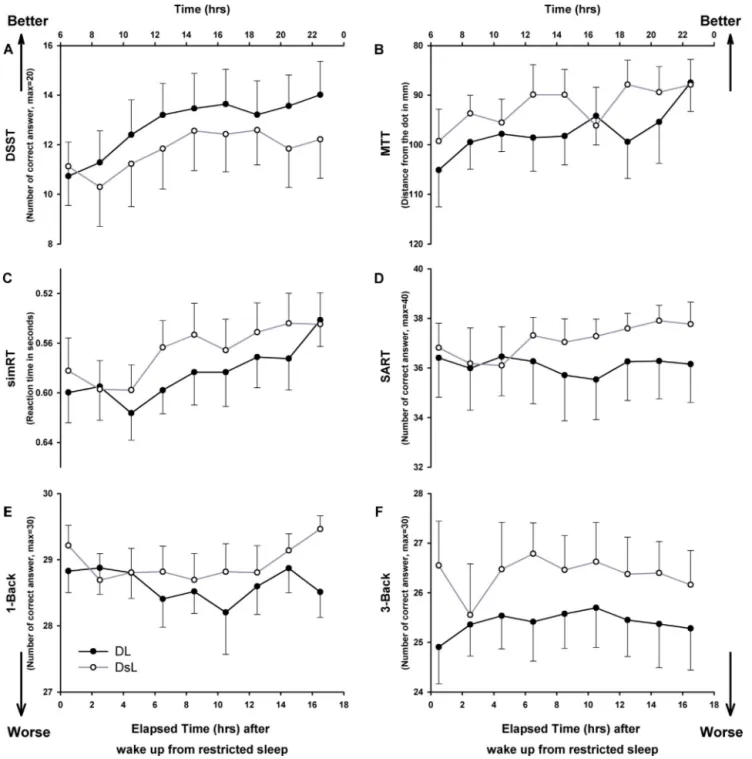

Main effects of “light condition” and “time-of-day” were

observedfortheMTT(Table3),suchthataftertheDsLexposure

par-ticipantswerebetteratfollowingthedotthanaftertheDLexposure

duringtheentireday(Fig2B).

3.2.2. DSST

Maineffectsof“lightcondition”and“time-of-day”werealso

observedforDSST(Table3)butintheoppositedirection.

Partic-ipantsperformedbetteraftertheDLexposurethanaftertheDsL

exposurethroughouttheday(Fig.2A).

3.2.3. PVSAT

PVSATperformancedidnotyieldsignificantdifferencesneither

forthemainfactors“lightcondition”,norfortheinteractionof

“lightcondition×time of day” (Table 3). Only thefactor “time

of day” was significant such that participants improved their

performanceacrossthedayindependentoflighttreatment(data

notshowninthefigure).

3.2.4. SART

Maineffectof“lightcondition”(Table3)wasobservedfor

accu-racy(correctanswersforGoandNoGotargets),suchthatuntil5-h

oftimeawake,theperformancewasnotsignificantlydifferent

irre-spectiveoflightsettings,while6-hafterwake-timeDsLimproved

performancealongthedayascomparedtoDL(Fig.2D).

Besides,NoGotrials wereanalyzed asa proxyfor inhibition

control.Itrevealedamaineffectof“lightcondition”(p=0.0013).

ParticipantshadlesscorrectNoGoanswersaftertheDsLexposure

thanaftertheDLexposureandmostlyatthebeginningoftheday.

Furthermore,themissedanswers(missedGoanswers)showeda

maineffectof“lightcondition”(p<0.0001),suchthattheDsLled

tolowerlevelsofmissedanswersthantheDL.Thereactiontime

forthistaskshowedalsoasignificanttrendofthe“light

condi-tion”effect(p=0.0876),suchthatparticipantsansweredfasterat

thebeginningofthedayaftertheDsL.

3.2.5. PVT/simRT

TheDsLexposuredidnotinfluencereactiontimeduringthePVT

(Table3,datanotshowninthefigure)andperformancewassimilar

afterbothlightexposures.However,theDsLdecreasedreaction

timeintheSimRTtestthroughouttheday,asshownbyamain

effectof“lightcondition”and“timeofday”(Table3,Fig.2C).

3.2.6. N-BACK

The1-Backshowedamaineffectof“lightcondition”(Table3)for

accuracy,drivenbyDsLexposure.After4-hofelapsedtimeawake,

DsLimprovedaccuracy,withastrongereffectintheevening,while

performanceremainedstableafterDLexposure(Fig.2E).

Nosignificantdifferenceswerefoundbetweenbothlight

con-ditionsinthe2-Backtest(datanotshowninthefigure).

Forthe3-Backtest,wefoundamaineffectof“lightcondition”,

suchthatparticipantshadahigherrateofcorrectanswersaftera

DsLthanafteraDLexposure,startingatthebeginningoftheday

andremainingalltheday(Fig.2F).

Table3

Resultsoftheanalysisofthevariancefordifferentvariablesofcognitiveperformanceforthetimecourseofthestudy. Variable Analysisofvariance

Light Timeofday Light×Time

MTT F1,260=1.76,p=.0079 F8,260=2.05,p=.0407 F8,260=.58,p=.7933 DSST F1,254=7.22,p=.0077 F8,254=2.44,p=.0148 F8,254=.25,p=.9800 SimRT F1,271=5.52,p=.0195 F8,271=3.07,p=.0025 F8,271=.33,p=.9554 PVT F1,264=3.31,p=.0700 F8,264=1.95,p=.0528 F8,264=.44,p=.8933 SART F1,255=5.07,p=.0252 F8,255=.28,p=.9731 F8,255=.31,p=.9601 PVSAT F1,272=0.96,p=.3277 F8,272=2.42,p=.0152 F8,272=.90,p=.5204 1-Back F1,255=5.86,p=.0162 F8,255=.66,p=.7269 F8,255=.88,p=.5368 2-Back F1,255=0.04,p=.8323 F8,255=.56,p=.8127 F8,255=1.12,p=.3497 3-Back F1,254=16.69,p<.0001 F8,254=.48,p=.8716 F8,254=.16,p=.9952

MTT:MotorTrackingTask;DSST:DigitSymbolSubstitutionTest;SimRT:SimpleReactionTimeTask;PVT:PsychomotorVigilanceTask;SART:SustainedAttentiontoResponse Task;PVSAT:PacedVisualSerialAdditionTask;1-2-3-Back:VisualN-backTask.

Fig.2.Accuracyofthecognitiveperformanceovertheday.

Timecourseofthe(A)DigitSymbolSubstitutionTest(DSST),the(B)MotorTrackingTask(MTT),the(C)SimpleReactionTimeTask(simRT),the(D)SustainedAttentionto ResponseTask(SART),the(E)Visual1-backTask(1-Back)andthe(F)Visual3-backTask(3-Back)in17participantsunderDimlight(blacklines)orDawnSimulationLight (greylineswithblackcircle).Dataareplottedasameanforeach2-hbinrelativetoelapsedtime(h)afterwake-upfromrestrictedsleep,andtheerrorbarsrepresentthe standarderrorofthemean.Elapsedtimeindicationisrelativeto6a.m.wake-uptime.

3.2.7. Reactiontimes

Furthermore,thecomposite score ofthe reactiontime from

those cognitive tests presenting higher cognitive load (n-Back,

SART,PVSAT)wassignificantlyloweraftertheDsLthanafterthe

DL(supplementarydata).

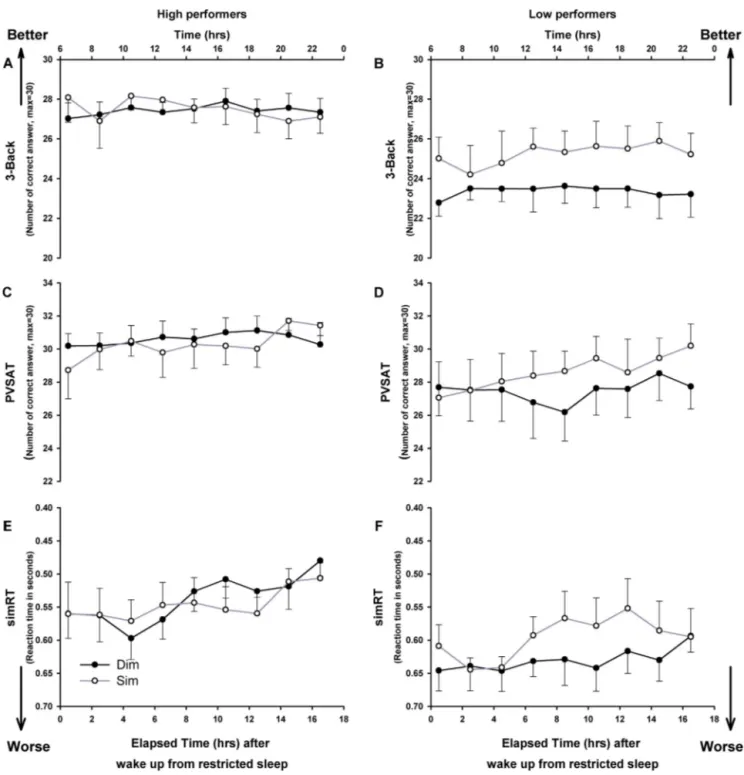

3.3. Highvs.lowperformers

Splittingthegroupaccordingtohighandlowperformance,a

maineffectof“lightcondition”waspresentinthelowbutnotin

thehighperformers,suchthattheDsLlightimprovedperformance

inthePVSAT(p=0.0096),the3-Backtest(p<0.0001)andthesimRT

test(p=0.0064)comparedtotheDLcondition(Fig.3).

4. Discussion

Ourdatashowthatartificialmorninglightexposure,asindexed

byDsL,hasatask-dependenteffectoncognitiveperformanceunder

sleeprestrictionconditions,suchthatmorningDsLsignificantly

enhancedperformanceonattention-basedtasks(SART,1-verbal

Back,and simRT).Furthermore,DsLsignificantlyimproved

per-formanceontheMTT that involvesmotor-basedskills, andthe

Fig.3. Accuracyofthecognitiveperformanceoverthedayinthehighandlowperformers.

Timecourseofthehighperformers(leftpanel)andthelowperformers(rightpanel)ofthe(A)Visual3-Back(3-Back),the(B)thePacedVisualSerialAdditionTask(PVSAT) andthe(3)SimpleReactionTimeTask(simRT)in17participantsunderDimlight(blacklines)orDawnSimulationLight(greylineswithblackcircle).Dataareplottedasa meanforeach2-hbinrelativetoelapsedtime(h)afterwake-upfromrestrictedsleep,andtheerrorbarsrepresentthestandarderrorofthemean.Elapsedtimeindication isrelativeto6a.m.wake-uptime.

wealsofoundbetterperformanceaftertheDLcomparedtotheDsL

fortheDSST.

Our results corroborate our previous analysis that artificial

morning dawn simulation light improvessubjective perception

ofwell-beingandmood,aswellascognitiveperformanceacross

thedayunderconditionsofmildsleeprestriction[14].However,

hereweshowedthatthelighteffectonperformancedependson

theinvestigatedcognitivedomain,suggestingthatdifferent

path-waysmaybeimplicatedinthiseffect.Previousstudiesindicatethat

eveninglightexposureimpactsonnumerousdomainsofcognitive

performancesuchassustainedattention[10],workingmemory

andattention,aswellasdeclarativememory[9].

Hereweshowthatlightexposureduringthemorninghours

cansignificantlyboostcognitiveperformanceandmaintainits

sta-bilitythroughouttheday.Moststudiesontheeffectsoflightin

humans have been carried out during the night, when light is

abletocounteracttheincreasingsleeppressure,andthus

signif-icantlyenhanceorstabilizecognitiveperformance(forareview,

see[29]).Inthiscontext,themodulatorymechanismsaccounting

forthelighteffectsoncognitionhavebeenascribedtoitsimpacton

sleephomeostasisand/oritsindirectsynchronizing/phase-shifting

effectsonthecircadiantimingsystem[10].However,alternative

mechanismsmaybypassthesesystems,thuselicitingdirect

Evidenceforthelatterarisesfromstudiesinwhichdaytime

per-formanceincreasedafter30minfromlightonset[30,31],froman

fMRIstudyinwhichdaytimelightenhancedcognitivebrainactivity

duringanoddballtask[32]andfromourpreviousanalysisinwhich

morninglightexposure(dawnsimulationlight)increased

well-beingandenhancedperformancesacrosstheday[14].Recently,

anotherstudyshowedthecriticalroleoflightforcognitivebrain

responses in emphasizing the evidence of a cognitive role for

melanopsin, which may confer a form of “photic memory” to

humancognitivebrainfunction[33].Collectively,thesedata

sug-gestthatlightmaymodulateongoingcorticalactivityinvolvedin

alertness,thusstimulatingcognitivebrainfunction.

Onecrucialbrainregioninvolvedintheimpactoflighton

cog-nitionistheanteriorhypothalamus,inlocationscompatiblewith

thesuprachiasmaticnucleusandtheventrolateralpreopticnucleus

[34].Thisregionispostulatedtobetheprimarylinkoftheretina

tothebrain,thusmediatingtheeffectoflightoncognition[13].

Furthermore,numerous retinalprojections extendtothelateral

geniculatenucleusandalso(albeitless)tothesuperiorcolliculus

(SC).Fromthelateralgeniculatenucleus,projectionsaresentto

theprimaryvisualcortex,whichisthefirstprocessingsiteofthe

corticalvisualpathway.Functionally,thispathwayisclassifiedin

dorsalandventralstreams[35].Theformerisassociatedtomotion

processing(medialtemporalandsuperiortemporal,andalso

pari-etalcortices),while thelatterinvolvessalientvisualprocessing

[36].Interestingly,attention-relatedmodulatoryeffectsimpacton

bothstreams.Withinthedorsalstream,attentionis“encoded”by

neuronsinvolvedinspatialattention/feature-basedattention,such

astheorientationofanobjectoramovingdot[36].Concomitantly,

motion-sensitivemedialtemporalandsuperiortemporalareasare

alsoinvolvedintheseprocesses,aswellashighercorticalareas

suchastheintraparietalcortex[37].Wetentativelyspeculatethat

thisparticularnetworkmaybeunderlyingtheresponsesinthe

MTTtask,andthatlightmightplayamodulatoryroleonthistype

ofspatialattention/feature-basedattention.

Withrespecttotheventralattention-basedstream,akey

struc-tureinvolvedinthisattentionalnetworkistheSC,whichreceives

directinputfromtheretina.Thisattentionnetworkispresumably

sharedwiththeintraparietalregion[38],frontaleyefields[39],and

visualcortices,throughdirectconnectionsfromthecortextothe

SC,andindirectlyfromtheSCtothecortexviathepulvinar[40].The

pulvinar(dorsalthalamicnuclei)ispivotalinattentionmodulation,

presumablythroughtheflowofinformationinthebrain.Itreceives

adirectretinalprojection,andprovidesanindirectlinkbetween

thesuprachiasmaticnucleusandtheprefrontalcortex[41].Thus,

itmediatesarousalregulation,andaneffectoflightonthe

thala-muswillprobablyresultinawidespreadcorticalimpact,suchason

attention-basedcognitiveperformance.Takentogether,we

postu-latethatthesebrainnetworksmayunderliethemodulatorylight

effectsonnumerousdimensionsofattentiontasks,suchasonMTT,

1-Back,simRTandSART.Itcouldalsoexplainthelackofcorrect

NoGoanswersandthedecreaseofthemissedGoanswersinthe

SARTtestaftertheDsLexposure.Effectively,arousallevelsaremore

prominentatthebeginningofthedayandmightevenbemore

pro-nouncedafteralightexposure,whichexplainsresponseaccuracyat

thebeginningoftheday.However,differenttasksrequiredifferent

levelsofarousalforoptimalperformance[42].Forexample,

dif-ficultorintellectuallydemandingtasksmayrequirealowerlevel

ofarousal(tofacilitateconcentration),whereastasksdemanding

staminaorpersistencemaybeperformedbetterwithhigherlevels

ofarousal(toincreasemotivation)[43].Accordingtothisconcept,

itcouldbearguedthatthearousallevelaftertheDsLexposure

wastoohightoinhibittheparticipant’sanswersintheSARTtask,

whichisinaccordancewiththeincreaseofthereactiontimein

thistaskduringthefirsthoursafterwaketime.Thisleadstoa

speed-accuracytrade-offintheinhibitoryprocess,meaningthat

lightexposureinduceshigherexcitabilityresultinginfaster

reac-tiontimeandthusinlackofinhibitioncontrol.

OurPVTdatadidnotparallelearlierfindingsofabeneficiallight

effect[10,30].Onepossibilityisthat,contrarytoourdesign,these

studieschallengedsustainedattentionperformanceeitherduring

lightexposureanddidnotspecificallyexplorecarry-overeffectsor

afteraprolongeddaytimelightexposure.Howevertheyare

com-parabletothefindingsfromVandeWerken[44],showingthatthe

reactiontimesunderDsLweresimilartotheoneundercontrol

condition.OnecouldarguethatthePVTneedsahigherand,more

probably,asustainedlevelofarousalthantheSARTtest–which

isnotreachedhere–togettooptimalperformancelevels,since

thistaskismuchmoremonotonouswithmuchfewerstimuli(e.g.,

[45]).Theabsenceofasignificanteffectcouldbetracedbackto

thefactthatwecomparedreactiontimesafteronenightofsleep

restrictionbetweentwolightconditions.Thisisdifferenttoother

studies,comparingrestedwakefulnesstosleepdeprivedorsleep

restrictedconditions.Similarly,theDSSTshowedthecontraryof

theexpectedeffect,suchthatparticipantswereslowerinreacting

andlessaccurate.Wehavenostraightforwardexplanationforthe

opposingeffectoftheDSST.Itcannotbeduetoasimple

learn-ingeffectacrossconditionsaswecounterbalancedtheorderand

wedidnotdetectasignificantinteractionbetweentimeofdayand

condition.Neithertheobservedpatterncanbeattributedtogeneral

impairmentsinworkingmemoryfunctionsacrossthedayunder

DsLaswefoundbetterperformanceunderDsLforthen-Backtest.

Thesetwotaskswerethefirsttwotasksadministeredwithineach

testingsessions,thus,acertaintime-on-taskeffectcanberuledout,

andaflooreffectoflightimpactbecauseofhighdemandisequally

implausible.

Interestingly,ourdataalsoshowasignificantDsLeffectonthe

3-verbalbacktask.Thistaskchallengesworkingmemory,which

referstotheindividualcapacitytotemporarilymaintainactive

rel-evantinformationtoperformanongoingtask[46,47].Thistask

involvestheneedtocontinuouslyupdateandinhibitinformation,

andalsohasanattentionalcomponenttoit.Thus,onepossible

explanationtotheDsLeffects isthatlightmayenhance

perfor-manceonthe3-backtaskviaitsimpactonthebasicattention

componentinthiscomplexworking-memorytask.However,atthe

behaviourallevel,itisnotpossibletodissectoutthecomponents

existingwithinthistask.Thus,lightmightalsoimpactonthe

exec-utivecomponent ofthis task.The3-backtaskprobesexecutive

control,anditscerebralcorrelatesinvolvethebilateralposterior

parietalcortex,premotorcortex,dorsalcingulate/medialpremotor

cortex,dorsolateralprefrontalcortexandventrolateralprefrontal

cortex[48].Lightmayhaveamodulatoryeffectontheseanatomical

structures,thusimpactingonexecutivebrainresponses[49].

Furthermore,lighthasgreaterbeneficialeffectsonthelow

per-formers(stratifiedaccordingtothe3-Backresults)comparedto

thehighperformersinthe3-back,PVSATandsimRT.However,itis

importanttoconsiderapotentialceilingeffectforthehigh

perform-ers;asthesleeprestrictionwasnotthatsevere,theseparticipants

couldeasilycopewiththisandthus,keeptheirhighlevelof

per-formance.Thereby,theimpactoflightmighthavebeendifficultto

detect.

Interestingly,thelowperformersonthe3-backwhoprofitmost

fromthelightintervention arealsotheoneswho experiencea

detrimentaleffectoflightontheirreactiontimesinthePVT.This

issomewhatcontra-intuitive,aswepreviouslyshowedthatlight

leadstofasterreactiontime[10].However,itcouldindicatethatthe

lowperformersaremorecautiousintheirtaskperformanceunder

theeffectoflight,andthereforeprofitinacomplextask,where

accuracyisimportant,butdeclineinamorebasictaskwherefast

reactionsarerequired.Clearly,itindicatesthatthelighteffectis

dependentonthecognitivedomainandobviouslyalsoacts

5. Conclusion

Ourresultscollectivelyindicatethatshortexposuretogradually

increasingmorninglight(DsL)justbeforetheendofthepartially

restrictednightepisode,maysignificantlyenhanceperformance,

particularlyincognitivetasksassociatedtoattention.Inabroader

context,thesefindingspointtostrategiesthatmaydirectly

opti-mizeattention-relatedcognitioninreal-lifesettings,particularly

whenindividualsaresleeprestricted.

Supplementarydata

Reactiontimefromthecognitivetestsovertheday.Timecourse

ofthecompositeofreactiontimeofthePacedVisualSerial

Addi-tionTask(PVSAT),SustainedAttentiontoResponseTask(SART)

andVisual1-2-3-backTask(1-2-3-Back)in17participantsunder

Dimlight(blacklines)orDawnSimulationLight(greylineswith

blackcircle).Dataareplottedasameanforeach2-hbinrelative

toelapsedtime(h)afterwake-upfromrestrictedsleep,andthe

errorbarsrepresentthestandarderrorofthemean.Elapsedtime

indicationisrelativeto6a.m.wake-uptime.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsreportnoconflictsofinterest.Theauthorsaloneare

responsibleforthecontentandwritingofthepaper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Götz for medical screenings, Claudia Renz,

Marie-France Dattler and Giovanni Balestrierifor their help in

data acquisition, AmandineValomon for her help in recruiting

volunteers and, of course,the volunteers to participating. This

researchwassupportedbyPhilipsConsumerLifestyle,Drachten,

TheNetherlands.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in

theonlineversion,athttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.043.

References

[1]DijkDJ,DuffyJF,CzeislerCA.Circadianandsleep/wakedependentaspectsof subjectivealertnessandcognitiveperformance.JSleepRes1992;1:112–7.

[2]SilvaEJ,WangW,RondaJM,WyattJK,DuffyJF.Circadianandwake-dependent influencesonsubjectivesleepiness,cognitivethroughput,andreactiontime performanceinolderandyoungadults.Sleep2010;33:481–90.

[3]BonnetMH.Performanceandsleepinessasafunctionoffrequencyand place-mentofsleepdisruption.Psychophysiology1986;23:263–71.

[4]VanDongenHP,MaislinG,MullingtonJM,DingesDF.Thecumulativecostof additionalwakefulness:dose-responseeffectsonneurobehavioralfunctions andsleepphysiologyfromchronicsleeprestrictionandtotalsleepdeprivation. Sleep2003;26:117–26.

[5]BelenkyG,WesenstenNJ,ThorneDR,ThomasML,SingHC,RedmondDP, etal.Patternsofperformancedegradationandrestorationduringsleep restric-tion and subsequent recovery: asleep dose-response study.J SleepRes 2003;12:1–12.

[6]DurmerJS,DingesDF.Neurocognitiveconsequencesofsleepdeprivation. SeminNeurol2005;25:117–29.

[7]JonesK,HarrisonY.Frontallobefunction,sleeplossandfragmentedsleep. SleepMedRev2001;5:463–75.

[8]Walker MP.Sleep-dependentmemoryprocessing. HarvardRevPsychiatry 2008;16:287–98.

[9]CajochenC,FreyS,AndersD,SpatiJ,BuesM,ProssA,etal.Evening expo-suretoalight-emittingdiodes(LED)-backlitcomputerscreenaffectscircadian physiologyandcognitiveperformance.JApplPhysiol2011;110:1432–8.

[10]ChellappaSL,SteinerR,BlattnerP,OelhafenP,GotzT,CajochenC.Non-visual effectsoflightonmelatonin,alertnessandcognitiveperformance:can blue-enrichedlightkeepusalert?PLoSOne2011;6:e16429.

[11]BersonDM,DunnFA,TakaoM.Phototransductionbyretinalganglioncellsthat setthecircadianclock.Science2002;295:1070–3.

[12]SmithMR,RevellVL,EastmanCI.Phaseadvancingthehumancircadianclock withblue-enrichedpolychromaticlight.SleepMed2009;10:287–94.

[13]VandewalleG,MaquetP,DijkDJ.Lightasamodulatorofcognitivebrain func-tion.TrendsCognSci2009;13:429–38.

[14]GabelV,MaireM,ReichertCF,ChellappaSL,SchmidtC,HommesV,etal.Effects ofartificialdawnandmorningbluelightondaytimecognitiveperformance, well-being,cortisolandmelatoninlevels.ChronobiolInt2013;30:988–97.

[15]BeckAT,WardCH,MendelsonM,MockJ,ErbaughJ.Aninventoryformeasuring depression.ArchGenPsychiatry1961;4:561–71.

[16]JohnsMW.Anewmethodformeasuringdaytimesleepiness:theEpworth sleepinessscale.Sleep1991;14:540–5.

[17]Horne JA, Ostberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol 1976;4:97–110.

[18]RoennebergT,Wirz-JusticeA,MerrowM.Lifebetweenclocks:dailytemporal patternsofhumanchronotypes.JBiolRhythms2003;18:80–90.

[19]BuysseDJ,Reynolds3rdCF,MonkTH,BermanSR,KupferDJ.ThePittsburgh SleepQualityIndex:anewinstrumentforpsychiatricpracticeandresearch. PsychiatryRes1989;28:193–213.

[20]AeschbachD,CajochenC,LandoltH,BorbelyAA.Homeostaticsleepregulation inhabitualshortsleepersandlongsleepers.AmJPhysiol1996;270:R41–53.

[21]VerweyW,VeltmanH.Detectingshortperiodsofelevatedworkload: com-parison of nine assessment techniques. J Appl Psychol Applied 1996;3: 270–85.

[22]DunhamKJ,ShadiS,SofkoCA,DenneyRL,CallowayJ.Comparisonofthe repeatablebatteryfortheassessmentofneuropsychologicalstatuseffortscale andeffortindexina dementiasample.Arch ClinNeuropsychol 2014;29: 633–41.

[23]AsterMvNA,HornRWAIS-III.WechslerAdultIntelligenceScaleFrankfurt/M., Germany:Harcourt2006.

[24]FeinsteinA,BrownR,RonM.Effectsofpracticeofserialtestsofattentionin healthysubjects.JClinExpNeuropsychol1994;16:436–47.

[25]NagelsG,GeentjensL,KosD,VleugelsL,D’HoogheMB,VanAschP,etal. Pacedvisualserialadditiontestinmultiplesclerosis.ClinNeurolNeurosurg 2005;107:218–22.

[26]RobertsonIH,ManlyT,AndradeJ,BaddeleyBT,YiendJ.‘Oops!’:performance correlatesofeverydayattentionalfailuresintraumaticbraininjuredand nor-malsubjects.Neuropsychologia1997;35:747–58.

[27]DingesDF,PackF,WilliamsK,GillenKA,PowellJW,OttGE,etal. Cumula-tivesleepiness,mooddisturbance,andpsychomotorvigilanceperformance decrementsduringaweekofsleeprestrictedto4-5hourspernight.Sleep 1997;20:267–77.

[28]CohenJD,PerlsteinWM,BraverTS,NystromLE,NollDC,JonidesJ,etal. Tem-poraldynamicsofbrainactivationduringaworkingmemorytask.Nature 1997;386:604–8.

[29]ChellappaSL,GordijnMC,CajochenC.Canlightmakeusbright?Effectsoflight oncognitionandsleep.ProgBrainRes2011;190:119–33.

[30]Phipps-NelsonJ,RedmanJR,DijkDJ,RajaratnamSM.Daytimeexposureto brightlight,ascomparedtodimlight,decreasessleepinessandimproves psy-chomotorvigilanceperformance.Sleep2003;26:695–700.

[31]RugerM,GordijnMC,BeersmaDG,deVriesB,DaanS.Time-of-day-dependent effectsofbrightlightexposureonhumanpsychophysiology:comparisonof daytimeandnighttimeexposure.AmJPhysiolRegulIntegrCompPhysiol 2006;290:R1413–20.

[32]VandewalleG,BalteauE,PhillipsC,DegueldreC,MoreauV,SterpenichV, etal.Daytimelightexposuredynamicallyenhancesbrainresponses.CurrBiol 2006;16:1616–21.

[33]ChellappaSL,LyJQ,MeyerC,BalteauE,DegueldreC,LuxenA,etal.Photic memoryforexecutivebrainresponses.ProcNatlAcadSciUSA2014;111: 6087–91.

[34]PerrinF,PeigneuxP,FuchsS,VerhaegheS,LaureysS,MiddletonB,etal. Nonvi-sualresponsestolightexposureinthehumanbrainduringthecircadiannight. CurrBiol2004;14:1842–6.

[35]GoodaleMA,MilnerAD.Separatevisualpathwaysforperceptionandaction. TrendsNeurosci1992;15:20–5.

[36]Baluch F, Itti L. Mechanisms of top-down attention. Trends Neurosci 2011;34:210–24.

[37]Martinez-TrujilloJC, TreueS.Feature-basedattentionincreases the selec-tivityofpopulationresponsesinprimatevisualcortex.CurrBiol2004;14: 744–51.

[38]BisleyJW,GoldbergME.Attention,intention,andpriorityintheparietallobe. AnnuRevNeurosci2010;33:1–21.

[39]ThompsonKG,BichotNP.Avisualsaliencemapintheprimatefrontaleyefield. ProgBrainRes2005;147:251–62.

[40]ShippS.Thefunctionallogicofcortico-pulvinarconnections.PhilosTransRoy SocLondonSerB:BiolSci2003;358:1605–24.

[41]SylvesterCM,KroutKE,LoewyAD.Suprachiasmaticnucleusprojectiontothe medialprefrontalcortex:aviraltransneuronaltracingstudy.Neuroscience 2002;114:1071–80.

[42]YerkesR,DodsonJ.Therelationofstrengthofstimulustorapidityof habit-formation.JComparatNeurolPsychol1908;18:459–82.

[43]Broadhurst PL. Emotionality and the Yerkes-Dodson law. J Exp Psychol 1957;54:345–52.

[44]VanDeWerkenM,GimenezMC,DeVriesB,BeersmaDG,VanSomerenEJ, GordijnMC.Effectsofartificialdawnonsleepinertia,skintemperature,and theawakeningcortisolresponse.JSleepRes2010;19:425–35.

[45]LimJ,DingesDF.Sleepdeprivationandvigilantattention.AnnNYAcadSci 2008;1129:305–22.

[46]BaddeleyA.Theconceptofworkingmemory:aviewofitscurrentstateand probablefuturedevelopment.Cognition1981;10:17–23.

[47]SchmidtC,ColletteF,CajochenC,PeigneuxP.Atimetothink:circadianrhythms inhumancognition.CognNeuropsychol2007;24:755–89.

[48]Sala-LlonchR,Arenaza-UrquijoEM,Valls-PedretC,Vidal-PineiroD,BargalloN, JunqueC,etal.Dynamicfunctionalreorganizationsandrelationshipwith work-ingmemoryperformanceinhealthyaging.FrontHumNeurosci2012;6:152.

[49]Vandewalle G,GaisS,Schabus M,Balteau E,CarrierJ, DarsaudA,et al. Wavelength-dependentmodulationofbrainresponsestoaworkingmemory taskbydaytimelightexposure.CerebCortex2007;17:2788–95.