Université de Montréal

Written Consent and Reproductive Autonomy in the Context of Prenatal Screening

Par Stanislav Birko

Département de médecine sociale et préventive, École de Santé Publique de l’Université de Montréal

Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.A. en Bioéthique

Décembre 2018

2

Université de Montréal

Département de médecine sociale et préventive, École de Santé Publique de l’Université de Montréal

Ce mémoire intitulé

Written Consent and Reproductive Autonomy in the Context of Prenatal Screening

Présenté par Stanislav Birko

A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes

Marianne Dion-Labrie Présidente-rapporteuse Vardit Ravitsky Directrice de recherche Isabelle ganache Membre du jury

3

Résumé

Le test prénatal non invasif (TPNI) est une technique de dépistage prénatal qui ne présente pas de risque accru de fausse couche, peut être effectué plus tôt dans la grossesse et est plus précis que les technologies existantes. Cependant, ces avantages peuvent contribuer à l’érosion de l’autonomie reproductive. Entre 2013 et 2017, une étude intitulée PEGASE a été menée, validant les performances et l'utilité du TPNI, ainsi qu’analysant les implications économiques, éthiques, juridiques et sociales de la technologie. Le présent mémoire est basé sur les données d’une enquête auprès des professionnels de santé (N = 184).

Ce mémoire aborde la relation entre les attitudes des professionnels de santé concernant a) le "consentement éclairé" et b) le "consentement écrit" dans le contexte du TPNI. Il remet en question le récit établi dans la littérature, que les professionnels qui croient que le consentement écrit pour le TPNI n'est pas important croient également que les procédures de consentement pour le TPNI «devraient devenir moins rigoureuses» (1).

Les données montrent que ce sont les professionnels qui se soucient de l'autonomie qui doutent de l'importance du consentement écrit. Cela contredit le récit cité ci-dessus. Les opinions des professionnels sur le «consentement écrit» ne peuvent donc pas être utilisées pour inférer leurs opinions sur l’importance du «consentement éclairé». Il est recommandé d’enquêter les professionnels de la santé sur des considérations particulières liées à la pratique, telles que celles enquêtées dans cette étude, plutôt que d’interroger les répondants sur des concepts académiques tels le «consentement» ou l’«autonomie».

4

Abstract

Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) is a new generation of prenatal screening that poses no increased risk of miscarriage, can be performed earlier in the pregnancy, and is more accurate than previously existing technologies. These advantages, however, potentially contribute to eroding reproductive autonomy, already under threat from other screening methods. Between 2013 and 2017, a study titled PEGASUS was conducted, validating the performance and utility of NIPT, as well as studying the economic, ethical, legal and social implications of the technology. One of these activities was a series of surveys conducted throughout Canada in 2015-16. The present thesis is based on the data from the healthcare professionals’ survey (N=184).

This thesis addresses the relationship between healthcare professionals’ beliefs regarding a) “informed consent” and b) “written consent” in the context of NIPT. It questions the established narrative in the bioethics literature, that professionals who believe written consent for NIPT is not important also believe consent procedures for NIPT “should become less rigorous” than those used for invasive prenatal testing (1).

Data from the survey shows that it is precisely those professionals who care about reproductive autonomy considerations who doubt the importance of written consent for NIPT. This directly contradicts the narrative cited above. Professionals’ stated views on “written consent” thus cannot be used to infer their unstated views on the importance of “informed consent”. It is recommended to investigate particular practice-based considerations such as the ones in this study rather than querying survey respondents on scholarly concepts such as “consent” or “autonomy”.

5

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 5

Roadmap 7

Acknowledgements 9

List of Tables & Figures 10

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 11

Chapter One: Background

Prenatal Screening 13

Longstanding Issues Raised by Prenatal Screening 13

NIPT 14

Challenges NIPT Poses to Autonomy 15

Guidelines 20

Chapter Two: Research Question

The Problem 21

Hypotheses 23

Chapter Three: Theoretical Frame

Consent: Informed et al. 31

(Informed) Consent 31

Written Consent 32

Why is written consent mistaken for informed consent? 33

Autonomy 35

Why use the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) definition of autonomy? 38 Chapter Four: The Study

Methodology 41

Data Collection and Ethics Approval 41

Data Analysis 42 Limitations 43 Respondent Characteristics 44 Results Descriptive Statistics 46 Hypothesis Testing 47

6

Summarized Interpretation of Salient Findings 53

Chapter Five: Discussion & Conclusions 55

Justifications given for valuing “written consent” 55 Justifications given for not valuing “written consent” 57 Concerns correlating negatively with perceived importance of written consent 60 Concerns almost correlating positively with perceived importance of written consent 61 Concerns uncorrelated with perceived importance of written consent 63

Conclusions 64

References 67

Appendix 1 72

7

Roadmap

Chapter One sets the background for posing the research question by going over the basics of prenatal screening, in general, and non-invasive prenatal testing, in particular, and the challenges these present to patient autonomy.

Chapter Two explains the bioethics literature that lead to the formulation of the research question of this thesis:

Is it possible to justify, given the Canadian data I have access to, the view that healthcare professionals’ stated disregard for written consent in the context of NIPT can be taken as indication of their belief that “consent procedures […] should become less rigorous” (Deans and Newson 2011)?

Chapter Three discusses the study’s theoretical frame, laying out the concepts of consent and autonomy as they are used herein, including the possible interpretations of why, given the inadequacy of written consent to indicate informed consent, and the body of literature criticizing written consent, it is that we sometimes fall into the trap of conflating the two. This brief section makes use of anthropological and historical analyses of what written consent symbolizes and how it has come to be reformulated “from a matter of liability to a means of patient protection by way of guaranteeing ‘autonomy’ to individual patients” (2).

Chapter Four presents the study methodology and results.

Chapter Five, the discussion, opens by going over research participants’ stated reasons for believing written consent to be important or not in the context of NIPT. These remind us that there is no monolithic “Canadian healthcare provider viewpoint”, and that although many respondents confuse written and informed consent in their responses, many others differentiate between the two. We likewise see evidence that 1) some healthcare professionals’ requirements for informed consent are eroding, as well as 2) other healthcare professionals are calling for more rigorous measures for respecting informed consent. The discussion then turns to interpreting the results of the quantitative portion of the study, which suggest that healthcare professionals who claim that “written consent is not important for NIPT” are more likely to be those who demonstrate respect

8

for certain aspects of patients’ autonomy, clearly contradicting the narratives that conflate written and informed consent.

9

Acknowledgements

Although I ought to thank everyone I have ever known and read (how can one ever be sure where one’s ideas come from?), I will attempt to highlight those who have directly contributed to my understanding of the issues treated in this thesis.

I thank those at the CGP at McGill for having trusted me enough to initiate me into the world of academic work, especially Edward Dove for his guidance and Nadine Thorsen for having recommended me for the job. Similarly, I thank Charles Dupras and Vardit Ravitsky (who has since then become my research director) for having originally initiated our collaboration, as well as everyone on the NIPT research team at the University of Montreal, namely Dre. Anne-Marie Laberge, Marie-Eve Lemoine, Aliya Affdal, Hazar Haidar, Jessica Le Clerc-Blain, Cynthia Henriksen, Marie-Christine Roy, and everyone who has joined the team more recently as well. Discussions with all of you have been extremely instrumental in the development of the ideas herein. I thank the CRÉ for financial support and the vote of confidence, the PIs of PEGASUS, François Rousseau and Sylvie Langlois for their leadership; Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Camilla Power, Chris Knight for their work on kinship, human evolution, and collective child-rearing, Roy Bhaskar for a much needed injection of realism. Huge thanks to my jury members, Marianne Dion-Mabrie and Isabelle Ganache, for the time and effort they have put in to help me make this work more meaningful, and Maria Teresa Hincapie who has spent countless hours helping me express my thoughts in a manner that is at least somewhat comprehensible to others.

10

List of Tables

Table 1. Participant Characteristics

Table 2. Healthcare Professionals’ Attitudes towards Written Consent for NIPT Table 3. Reasons to Offer NIPT to a Patient

Table 4. Reasons not to Offer NIPT to a Patient

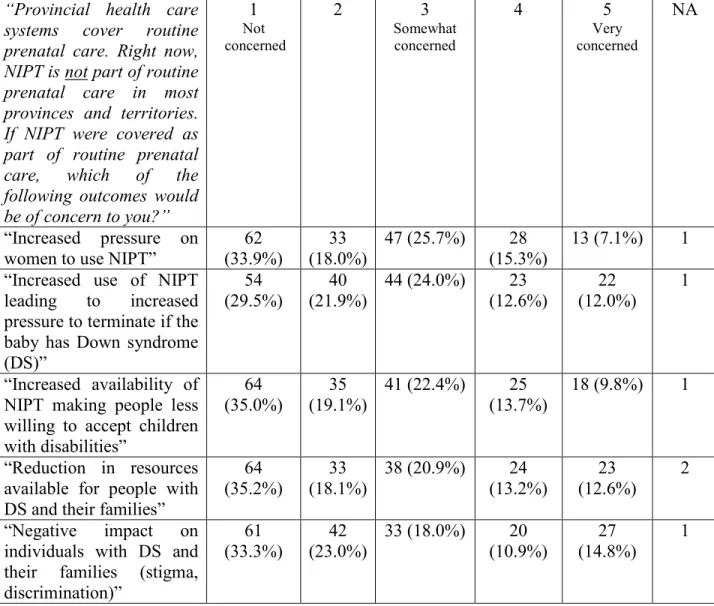

Table 5. Healthcare Professionals’ Level of Concern Regarding Societal Concerns Related to NIPT

Table 6. Results of Hypothesis Testing comparing “No” to “Yes” (disregarding the “not sure”s) Table 7. Results of Hypothesis Testing comparing (“No” OR “not sure”) to “Yes”

List of Figures

Figure 1. Autonomy Is Not Independence

11

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

AB: Alberta

ACMG: American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics BC: British Columbia

CCMG: Canadian College of Medical Geneticists cfDNA: circulating free deoxyribonucleic acid

CHU: Centre hospitalier de l’université … (french for University Health Centre) CRCHU: Centre de Recherche du CHU … (french for CHU Research Centre) DS: Down syndrome

FTS: First Trimester Combined Screening HCP: Healthcare professional/practitioner HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus IPS: Integrated prenatal screening IRB: Institutional Review Board

ISPD: International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis MB: Manitoba

MSS: Maternal serum screening NIH: National Institutes of Health NIPD: Non-invasive prenatal diagnosis NIPS: Non-invasive prenatal screening NIPT: Non-invasive prenatal testing ON: Ontario

PEGASUS: PErsonalized Genomics for prenatal Aneuploidy Screening USing maternal blood Pt: Patient

QC: Québec

SD: Standard deviation

SOGC: Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada SDT: Self-Determination Theory

TCPS2: Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 U: University

13

CHAPTER ONE:BACKGROUND

PRENATAL SCREENING

Prenatal screening refers to any technology that identifies pregnancies with a high probability of being affected with conditions such as chromosomal abnormalities (e.g. Down Syndrome (DS)) and neural tube defects. Prenatal screening differs from prenatal diagnosis (e.g. amniocentesis) in that screening only yields probabilistic results such as 1:100 or 1:10 000, and thus never completely rules out the possibility of the disease or condition being present. Diagnostic tests do provide a definitive positive or negative result. A diagnostic procedure is thus needed to confirm screening results before deciding on a further course of action (e.g., preparation for a child with possible special needs, prenatal intervention, or pregnancy termination) (3). Prenatal diagnostic techniques such as amniocentesis are not without risk, resulting in miscarriage in 0.5% of cases on average.

Of the approximate 450 000 pregnancies annually in Canada, approximately 10 000 undergo amniocentesis, of which 315 are found to have a baby with DS and with 70 unaffected pregnancies lost from complications of the procedure (4).

Longstanding Issues Raised by Prenatal Screening

At its inception in the 60’s and 70’s, prenatal testing was presented as a means of preventing disease and “mental retardation” (5). It is only in the 90’s that the concept of reproductive autonomy became dominant in the discourse concerning prenatal screening. Following criticism from feminist and disability rights activists, the various professional bodies involved in providing prenatal screening services distanced themselves from accusations of eugenic practices by framing prenatal screening as a matter of personal choice regarding one’s life as opposed to a matter of public health (3, 5).

Since then, autonomy and choice have been heralded as the main goals of prenatal screening (6), fitting into ‘free-market’ narratives that medical innovations are adopted as a result of sufficient demand by free and rational homo oeconomicus (7). This would mean that women of child-bearing age must have demonstrated sufficient interest for market forces to drive the development of relevant tests. However, in the case of prenatal screening, this scenario has been

14

questioned: “programs were initiated by government organizations, interested sectors of the medical profession, and the medical supply industry for their own purposes” (6, 8). This strengthens the argument that autonomy might be used as a fig leaf hiding different interests (3, 9).

Paradoxically, while being touted as enhancing choice, prenatal screening has, from its infancy, been criticized for undermining parents’ autonomy (10). Press and Browner claimed that when screening programs were first introduced by the government (in their case, in California), stakeholders had no interest in promoting reproductive autonomy via processes of informed consent. Stakeholders included the attending healthcare professionals who feared that if women reject screening they may face malpractice liability for “later claims of inadequate test explanation,” policy-makers whose interests were in increasing screening for economic and public health reasons, and expecting women who wanted access to available services but preferred to not engage in complicated deliberations that would involve the possibility of pregnancy termination. It is therefore important to contextualize the concept of “choice” that allegedly underlies prenatal screening within the broader social context, in order to effectively frame these choices (or lack thereof). Prenatal screening has thus been criticized for raising a slew of issues that ultimately inhibit reproductive autonomy, precisely the opposite of what it was lauded for (3).

NIPT

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) is a technology first introduced into clinical practice in 2011 (11). The technology is based on the discovery that cell-free fetal DNA originating from the placenta and circulating in maternal blood can be tested to detect genetic conditions in the fetus as early as the 9th week of pregnancy. NIPT holds no risk of miscarriage and offers clinical benefits over existing prenatal screening tests such as maternal serum screening (MSS) by detecting the presence of trisomy 21 with high sensitivity and specificity (99.9% and 98% respectively) (12-14).

By offering relatively easy and early detection of abnormalities, without risk to the fetus, NIPT provides important benefits for pregnant women and their families when compared to conventional screening and amniocentesis. The fact that results can be available earlier provides parents with more time to make decisions about the course of action and outcome of the pregnancy. Likewise,

15

NIPT’s improved accuracy reduces the number of false-positive and false-negative results thereby diminishing the drawbacks associated with traditional modes of screening. False-negative results can generate a false sense of reassurance, while false-positive results can provoke unnecessary anxiety and stress. NIPT also reduces the need for invasive procedures since it has higher detection rates and lower false-positive rates compared to any previous prenatal screening tests. NIPT thus has the benefit of reducing the number of fetal losses associated with invasive tests. When it comes to a positive NIPT result, all professional societies currently recommend confirming the result with invasive diagnostic testing prior to making any decision regarding termination (15).

The benefits NIPT may offer pregnant women are significant, and therefore, not offering or covering it may constitute an infringement on reproductive autonomy, just as limiting access to any reproductive technology may constitute an affront to reproductive autonomy. However, it is precisely these purported benefits of NIPT that ethicists warn may lead to an exacerbation of the ethical issues intrinsic to prenatal testing, particularly those related to reproductive autonomy.

CHALLENGES NIPT POSES TO AUTONOMY

The timing, reliability and safe nature of NIPT exacerbate concerns regarding the pressure placed on parents to screen and possibly terminate due to positive diagnostic results.

First, NIPT can provide results earlier in the pregnancy than previous screening tests. This provides a crucial benefit to pregnant women and their families, as it allows earlier diagnostic testing and – in case of a positive diagnostic result – either more time to prepare for possible early therapeutic interventions or just to prepare for the birth of a child with special needs, or an earlier pregnancy termination. At the same time, the timing, reliability and safe nature of NIPT exacerbate concerns regarding the pressure placed on parents to screen and possibly terminate due to positive diagnostic results (3). Prior to the introduction of NIPT, parents could decline screening under the ‘pretext’ of poor performance of conventional screens, the risk of miscarriage associated with invasive diagnostic testing and the fact that results are only available at an advanced stage of the pregnancy (approaching 20 weeks) even if they actually had other reasons for not screening (16). Such reasons could include a preference for a less medicalized pregnancy or an acceptance of the

16

possibility of having a disabled child, reasons which they might fear care providers, family members or society would not approve of (17).

Second, the non-invasive (i.e. safe for the fetus) nature of NIPT, may lead to further undermining of informed consent and reproductive autonomy. Empirical studies have shown that some healthcare professionals believe NIPT warrants less formal informed consent procedures because it presents no increased risk of miscarriage (3, 18, 19). In addition, the common practice of same day pre-test counselling, directly followed by NIPT, further erodes informed consent because it eliminates the reflection period during which patients can discuss and decide whether to undergo screening (20).

Third, the increased accuracy of NIPT results, as compared with previous screening techniques, changes the nature of the information the test yields. Whereas previous technologies provided a probability that the pregnancy is at high risk, NIPT now yields results (at least for trisomy 21) that may be perceived by parents as quasi-diagnostic. If consent is lacking or not fully informed, parents may receive results that they are unprepared for, or even do not wish to know(3). It may be argued that disclosure of an unwanted result from NIPT that is more reliable violates parents’ reproductive autonomy more extensively than the disclosure of more uncertain risk information (9).

Prenatal screening is seen by many women as part of routine prenatal care (21, 22). Although NIPT has been rapidly implemented into publicly-funded screening pathways in some countries (e.g. the Netherlands, Belgium) (23-25), in most countries it is still offered only privately (11, 26) and is not yet considered standard of care, despite strong commercial interests that strive to make it a routine part of prenatal care (27, 28). NIPT offers great benefits and is thus a laudable, as well as ethically acceptable, step forward when it comes to enhancing women’s access to information they desire. At the same time, issues inherent in prenatal screening concerning reproductive autonomy have not yet been resolved and can now be exacerbated by NIPT(3).

On the other hand, some may view the disclosure of more reliable results, even without appropriate consent, as less damaging than the disclosure of risk information. This is because risk information can create much anxiety for no reason (since with previous screening technologies most cases ended up being false positives), whereas NIPT results provide more certainty and significantly reduce the number of individuals unnecessarily exposed to anxiety and stress. This is

17

the rationale behind the recently proposed mechanism of ‘reflex testing’ (29), in which two blood samples are taken when women go through conventional serum screening. If a woman’s first-tier screen comes back as high-risk, her second blood sample is automatically sent for NIPT, and the woman is only informed of the NIPT result, without ever having been exposed to the less reliable result of the first-tier screen. The researchers who proposed this model argue that this eliminates the unnecessary anxiety suffered by all those for whom first-tier serum screening produces false-positive high-risk results. However, there is no assurance of women being properly counseled and understanding the testing pathway they have unknowingly embarked upon. Thus, the advantage of reduced anxiety is achieved at the expense of informed consent and the woman’s right to choose (3, 30-32).

In addition to feeling undue pressure when presented with the allegedly free choice of whether to screen, diagnose, and terminate, infringements on reproductive autonomy can occur when women do not sufficiently understand the implications of the test (3). Research has revealed that a significant number of women undergo screening without being aware that they were being tested (33, 34). Even if they are made aware that they are being screened and agree to it, many women report having received inadequate information about the conditions screened for, and what these conditions imply on a day-to-day basis, or having been led to believe that screening was mandatory or medically required (35-38). Such practices reflect the lack of time allowed for counseling: “As almost all results will be reassuring, professionals may also find it less important to inform women about the choices they may be faced with down the line of a further screening trajectory” (39).

Disability rights scholars and activists claim that many people make prenatal screening decisions based on misconceptions about disability (27), therefore making uninformed choices, and that these misconceptions may be reinforced by health professionals who share them (40).

Even if all relevant information regarding screening is made available and precautions to avoid any undue pressure are taken, the question regarding whether more information necessarily translates into greater autonomy remains. Evidence shows that prospective parents may experience bewilderment at the amount of information provided by prenatal screening (41). Information overload can be a cause of anxiety and stress and prospective parents may be left feeling perplexed when faced with the subsequent decisions they must make (3). It is important to note that this “burden of choice imposed on women” (20) is difficult because of the sensitive nature of the

18

information presented. This type of information can unnecessarily increase anxiety for the prospective parents (42), negatively affect the pregnancy experience and present parents with difficult reproductive choices – choices that they might not have had to face if they had forgone prenatal screening (39, 43).

Additionally, this “bewilderment” applies not only to results provided by prenatal screening but also to information provided about prenatal screening at various stages of the process(3). Hence, while Press and Browner (10) pointed out that prospective parents prefer not to dwell on the social and ethical dimensions of prenatal screening, Kukla (44) suggested that parents often make a conscious choice to defer decisions to healthcare practitioners as a way of avoiding the burdens of information overload and decision-making regarding screening.

While respecting autonomy necessarily requires doing so throughout the process of prenatal screening, the social contexts outlined above create barriers to achieving this goal (9). Seavilleklein (6) concluded in 2009 that “there is incontrovertible evidence that women are not making free informed choices about prenatal screening”, that “whether choice is interpreted narrowly as informed consent or broadly as relational, there are reasons to worry that women’s autonomy is not being protected or promoted by the routine offer of screening” and that “incorporating the offer of prenatal screening into routine prenatal care for all pregnant women is not supported by the value of autonomy and ought to be reconsidered.” These conclusions regarding prenatal screening were reached before the advent of NIPT. Ultimately, the introduction of any new prenatal screening technology into mainstream practice would require an attentive assessment of whether its implementation would contribute to or conversely undermine reproductive autonomy (3).

Societal pressure to screen, to diagnose or to terminate a pregnancy in case of positive results negatively affect the possibility of exercising reproductive autonomy. These are three separate, but interconnected, pressures. It is argued that, given the nature of our “performance society” (45), prenatal screening for conditions perceived as disabilities is framed as the responsible choice. As such, pregnant women often feel obligated to screen for these conditions and accede to the “collective silence” that positive results should eventually lead to pregnancy termination (46). Many people, when faced with the decision of whether to pursue prenatal screening, may believe that it would be irresponsible to decline participation in a publicly funded program seemingly designed for the benefit of society as a whole. After all, the implementation of such tests by the

19

medical system “establishes screening as a legitimate use of scarce medical resources and thereby surreptitiously underlin[es] its importance” (3, 6).

Pressures from the medical community also exacerbate the onus felt by parents to screen prenatally. There is evidence that medicine and preventive care are playing an increasing role in influencing decisions related to personal and social life. Great importance is placed on early detection and prevention of diseases and conditions, which has resulted in societal beliefs that people should participate in prevention programs and can be “morally blamed” if they fail to do so (47). Pregnancy, essentially a personal life event, has been affected by this social emphasis on disease prevention and is often perceived as requiring medical intervention and preventive care (3).

Furthermore, clinicians are often criticized for being too directive when counselling patients regarding prenatal screening options (46). Logistical constraints, fears of malpractice and negligence litigation as well as clinicians’ own perceptions of the value of screening are all factors that can lead to clinicians – consciously or unconsciously – placing undue pressure on women to undergo prenatal screening. Likewise, when discussing possible future results of screening, high-risk results are often framed in ways that do not allow much space for deciding not to continue on the testing pathway. When results become available, problems in communicating them clearly, transparently, meaningfully, and in a non-directive manner have been documented, with practitioners more often recommending screening, diagnosis and pregnancy termination (3, 41, 48, 49).

Lippman noted as early as 1986 that “implicit in the model is the acceptance […] that women whose fetuses are found to be affected will abort the pregnancy, since for most of the conditions for which screening can be done there is, at present, no treatment” in utero (50). Indeed, until today, the vast majority of pregnancies found to be affected with Down syndrome are terminated (51). The lack of social support for those raising children with special needs is thought to contribute to this sense of limited choice: “without extensive social support systems, termination may be the only viable reproductive option even when women or families may be willing or may desire to raise a child with special needs” (3, 26).

Intimately related to the pressure to terminate are the so-called eugenics concerns, or what is often referred to as the “disability critique” of prenatal screening. The disability critique claims

20

that not only does the elimination of persons with certain conditions lead to further stigmatization of the condition, but that such practices may affect individuals already living with the condition. As such, if there is a decrease in the birth rate of individuals with a particular condition, the number of public resources and support services may also decrease (27). In attempting to enhance reproductive autonomy, it is important not to decrease the choices available to those who may want to pursue a pregnancy diagnosed with a disability or condition (3).

Guidelines

In 2013, the Genetics Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) recommended the test be an available option for pregnant women who have been identified as being at increased risk of fetal aneuploidies – through for example the results of MSS - of having an affected pregnancy (52). In 2014, the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis (ISPD) considered the offer of NIPT as a first-tier screening test for all pregnant women to be an “appropriate” option (53). Of particular relevance to the present research:

■ “All pregnant women in Canada, regardless of age, should be offered, through an informed counselling process, the option of a prenatal screening test for the most common fetal aneuploidies (II-A).” (15)

■ “A discussion of the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the various prenatal diagnoses and screening options, including the option of no testing, should be undertaken with all patients prior to any prenatal screening. Women should have further discussion regarding local and provincial options available to them for prenatal genetic screening. Following this, they should be offered:

(1) no aneuploidy screening,

(2) standard prenatal screening based on locally offered paradigms, (3) ultrasound guided-invasive testing, or

(4) maternal plasma cfDNA screening where available, with the understanding that it may not be provincially funded.” (15)

21

CHAPTER TWO:RESEARCH QUESTION

THE PROBLEM

A study titled Will the introduction of non-invasive prenatal testing erode informed choices?

An experimental study of health care professionals was published in 2010 in the journal Patient Education and Counseling (54). It reports the findings of a questionnaire administered to 231 UK

health professionals “currently involved in the provision of prenatal testing”. The participants were presented with one of three vignettes where they “imagine working in an antenatal clinic at a point in time when all pregnant women are routinely offered prenatal testing for DS”, each of three vignettes referring to either: 1) invasive (and thus risky) prenatal diagnosis, 2) non-invasive prenatal screening using a blood draw (akin to NIPT), and 3) non-invasive diagnostic blood test (what the authors call NIPD – non-invasive prenatal diagnosis). The participants are asked “Do you think it is important for women undergoing this test to sign a consent form?”, with 4 choices of responses: from 1, definitely yes to 4, definitely not. No other question regarding written consent or informed consent is reported. Depending on which of the three types of test was described in the vignette, the way respondents answered the question on the importance of signing a consent form differed, with professionals believing signing a consent form to be less important for invasive testing than for invasive testing. No attempt to link this result to what effect the non-invasiveness of prenatal testing could have on informed consent is made in the paper; however, the title surprisingly includes “informed choices” rather than “written consent” or “signing a consent form”.

This paper turned out to be highly influential in the field, being cited 110 times, according to google scholar. And, indeed, if we look at how the findings are interpreted in articles that cite this 2010 study, the conflation of these two very different concepts of “written” and “informed consent” continues. In their 2010 article Non-invasive prenatal testing: ethical issues explored (55) (cited 145 times according to google scholar), de Jong et al. cite van den Heuvel et al. (54) as finding “that health care professionals seem inclined to the view that a less stringent standard of informed consent would suffice for NIPD testing”. In the 2011 Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis:

pregnant women’s interest and expected uptake (37) (cited 127 times according to google scholar),

Tischler et al. cite van den Heuvel et al. as evidence that “[b]ecause of the noninvasive nature and the lack of miscarriage risk, obstetricians may be less likely to approach the consent process as

22

rigorously for NIPD as they currently do for invasive diagnostic testing”. Others, such as Allyse et al.’s 2015 Non-invasive prenatal testing: a review of international implementation and

challenges (11) (cited 147 times according to google scholar), do not conflate the two concepts,

citing van den Heuvel et al. (54) as evidence that physicians “feel there is less need to obtain written consent for NIPT than for invasive testing”, which van den Heuvel’s study did, indeed, find. An article by 2 of the co-authors of the original 2010 paper demonstrates that the confusion between informed consent and signing a consent form was not limited to the catchy title or other authors’ overinterpretation of the findings, as Deans’ and Newson’s 2011 Should

Non-Invasiveness Change Informed Consent Procedures for Prenatal Diagnosis (1) abstract begins

with “[e]mpirical evidence suggests that some health professionals believe consent procedures for the emerging technology of non-invasive prenatal diagnosis should become less rigorous than those currently used for invasive prenatal testing”. Believing that consent procedures “should become less rigorous” is a stretch from the original paper’s “practitioners will view the consent process for prenatal diagnostic testing differently”.

While it may sometimes be obvious that informed consent is not reducible to signing a consent form, the narrative reducing it exactly in this way has been put forward and propagated significantly in very influential literature. While it is plausible that practitioners may, indeed, care less about informed consent for procedures that are not risky, that is not the only possible explanation. Another one, which is quite opposite, could be that due to the complexity of interpreting genetic test information, practitioners may increasingly believe that signing a consent form is not a sufficiently adequate manner of ensuring informed consent.

The present research sets up a series of statistical hypothesis tests looking for evidence of practitioners who state in surveys that written consent is not important for NIPT being the same practitioners who believe informed consent should be less rigorous for NIPT. There are four possible outcomes of this survey:

1. No correlations are found whatsoever (no null hypotheses are rejected), meaning we can assert nothing regarding the relation between what practitioners believe regarding informed consent and regarding signing consent forms;

2. Evidence for the narrative suggested by van den Heuvel et al. (54) is found; 3. Evidence refuting the narrative suggested by van den Heuvel et al. (54) is found;

23

4. Evidence both for and against the narrative suggested by van den Heuvel et al. (54) is found.

HYPOTHESES Group A

Hypothesis 1 – Voluntariness

It is possible for a patient to request to undergo NIPT. All else being equal, especially ensuring that the patient has access to the relevant information regarding the test, respect for such a request would constitute respect for the importance of a patient’s consent. Therefore, the relationship between claiming to be motivated by respecting one’s patient’s wishes to undergo screening and the rejection of the importance of written consent for NIPT is to be tested.

H1.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the patient asking for the test.

H1.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the patient asking for the test.

Hypothesis 2 – Right not to know

It is also possible for a patient not to want to know whether the fetus they carry has DS. A practitioner caring about informed consent would not offer NIPT to such a patient, regardless of whether they signed a consent form or not.

H2.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

influenced to NOT offer NIPT to a specific patient by the patient not wanting to know whether the fetus has DS.

H2.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

influenced to NOT offer NIPT to a specific patient by the patient not wanting to know whether the fetus has DS.

24

Hypothesis 3 – Early results

As stated above, NIPT provides results earlier than other forms of screening. While having more time for making a decision does not obviously make the said decision more informed, it can be argued that those who would prefer to terminate a pregnancy with a fetus with DS could feel freer to do so if they found out about the DS earlier on in the pregnancy. Therefore, while having results earlier may not necessarily make the decision regarding testing more informed it does provide for more options regarding future pregnancy management.

H3.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the fact that “NIPT would allow my patient to find out early in the pregnancy whether the fetus has DS or not”.

H3.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the fact that “NIPT would allow my patient to find out early in the pregnancy whether the fetus has DS or not”.

Hypothesis 4 – Evidence-base

Whether or not a practitioner believes there is sufficient clinical data on NIPT has direct bearing on how informed the consent they can obtain from their patient can be.

H4.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

influenced to NOT offer NIPT to a specific patient by insufficient clinical data on NIPT.

H4.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

influenced to NOT offer NIPT to a specific patient by insufficient clinical data on NIPT.

Hypotheses 5,6 – Economic considerations

It is less obvious to see whether a patient being able to financially afford the test has bearing on whether they can meaningfully consent to it. Nevertheless, it was decided to include this series of hypotheses, based on 2 separate questions in the survey, among other things to test the consistency of survey responses, since this was the only issue queried twice, stated positively or negatively.

25

H5.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

influenced to NOT offer NIPT to a specific patient by the patient being unable to pay for the test.

H5.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

influenced to NOT offer NIPT to a specific patient by the patient being unable to pay for the test.

H6.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the cost of the test being covered.

H6.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the cost of the test being covered.

Group B: Societal Concerns

Hypothesis 7 – Pressure to test

It has been hypothesized that a routinization of offering NIPT can lead to women feeling pressure to undergo the test, whether they would otherwise want to or not. We queried practitioners as to their level of concern regarding routinization leading to such pressure to test.

H7.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with level of

concern over “increased pressure on women to use NIPT” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

H7.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with level of

concern over “increased pressure on women to use NIPT” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

Hypothesis 8 – Pressure to terminate

Similarly, it has been hypothesized that a routinization of NIPT can lead to more pressure felt by women to terminate a pregnancy with a fetus testing positively for DS.

26

H8.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with level of

concern over “increased use of NIPT leading to increased pressure to terminate if the baby has DS” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

H8.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with level of

concern over “increased use of NIPT leading to increased pressure to terminate if the baby has DS” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

Hypothesis 9 – Societal inclusivity

If a person believes that most other people use NIPT and terminate pregnancies of fetuses with DS, it is logical for this person to believe that the society into which they plan to bring a child is not accepting of children with disabilities. Such a belief could influence a person not to carry a pregnancy with a fetus with DS to term, even if they would have liked to do so had society been more inclusive.

H9.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with level of

concern over “increased availability of NIPT making people less willing to accept children with disabilities” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

H9.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with level of

concern over “increased availability of NIPT making people less willing to accept children with disabilities” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

Hypothesis 10 – Societal support

Similarly to 9, if a person believes that most other people use NIPT and terminate pregnancies of fetuses with DS, it is logical for this person to believe that any resources currently earmarked for people with DS or their families could be dismantled. Such a belief could influence a person not to have a child with DS, unless they were certain that they had the resources to raise such a child without support from social institutions.

27

H10.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with level of

concern over “reduction in resources available for people with DS and their families” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

H10.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with level of

concern over “reduction in resources available for people with DS and their families” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

Hypothesis 11 – Discrimination

Believing that society is increasingly discriminative of people with DS would inhibit a truly free choice regarding having a child with DS.

H11.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with level of

concern over “negative impact on individuals with DS and their families (stigma, discrimination)” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

H11.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with level of

concern over “negative impact on individuals with DS and their families (stigma, discrimination)” “if NIPT were covered as part of routine prenatal care”.

Note on group B of hypotheses:

Practitioners’ concern over the above five societal issues related to the routinization of NIPT is relevant to how they perceive the importance of informed consent, because being concerned with any of these societal issues (that affect the conditions under which patients are making their reproductive decisions) is indicative of practitioners’ awareness of the multifaceted nature of informed consent, beyond the mere signing of consent forms.

Group C – Seeking alternative interpretations

While it is possible that survey respondents who care about informed consent are less likely to perceive written consent as important, it is also possible that those who do perceive written consent

28

as important would be more likely to seek written consent for legal protection. As there were no questions in the survey directly related to legal liability, two other questions were chosen as proxies. The first had to do with professional recommendations and the second with the practitioner’s lack of comfort explaining the test.

The reasoning was that if a practitioner claimed to be influenced by professional recommendations as to whether to offer the test, they may not be sufficiently informed on the technology and could be unreflexively following guidelines. If they were, themselves, not sufficiently informed, they could hardly provide the information necessary for the patient’s consent to be informed. Before such an interpretation is criticized for its naivety, I admit it myself. I am simply documenting my own (past and mistaken) reasoning for setting up the tests as they were. Nevertheless, I am glad to have had such mistaken and naïve reasoning, because it led me to set up this hypothesis (13), which adds important nuance to the research findings.

Similarly, I believed that a practitioner who claimed not to be comfortable explaining the test would not (and could not) ensure informed consent, but would rather be interested in having a signed consent form in order to avoid legal liability.

Hypothesis 12 – Deference to professional recommendations

H12.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the test being recommended by professional organizations (SOGC, CCMG, ACMG).

H12.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

influenced to offer NIPT to a specific patient by the test being recommended by professional organizations (SOGC, CCMG, ACMG).

Hypothesis 13 – Practitioner’s discomfort

H13.0: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” does NOT correlate with being

29

H13.A: Believing “it is important to get written consent for NIPT” DOES correlate with being

31

CHAPTER THREE:THEORETICAL FRAME

CONSENT:INFORMED ET AL.

There are two non-identical concepts used in the present research: consent (or informed consent) and written consent.

(Informed) Consent

According to Canadian legal guidelines (56, 57), “valid consent” requires: 1) that it is voluntary, i.e., “free of any suggestion of duress or coercion”; 2) that the patient has the capacity to consent, i.e.:

a) be over the age of 14 years;

b) demonstrate sufficient mental capacity to consent to medical interventions (the threshold of mental capacity is lower than for many other types of decisions); 3) that the patient be “properly informed”.

Satisfying the third condition is what confers the “informed” status on an act of consent. For it to be satisfied, the patient must be provided with “an adequate explanation about the nature of the proposed investigation or treatment and its anticipated outcome as well as the significant risks involved and alternatives available”. The information provided must be of such nature so as to allow for the decision taken by the patient to be considered “informed”. Furthermore, the guidelines state that the ultimate responsibility to ensure that consent is informed lies with the physician “who is to carry out the treatment or investigative procedure” (57).

Whereas the Canadian Supreme Court has concluded that the scope of the duty of disclosure “must be decided in relation to the circumstances of each particular case” (57, 58), the notion of “reasonable person” can sometimes be invoked such as in the definition of what makes risk “material” and thus to be disclosed: "A risk is thus material when a reasonable person in what the physician knows or should know to be the patient's position would be likely to attach significance to the risk or cluster of risks in determining whether or not to undergo the proposed therapy." (59)

32

Providing necessary information is not sufficient for consent to be considered informed. The physician also has the duty to “take reasonable steps so as to be relatively satisfied that the patient does understand the information being provided” (57).

Finally, valid consent must allow for its withdrawal at any time, by simple verbal notice (or otherwise in case of speech difficulties), thus introducing another condition for valid consent – that it be ongoing. It is especially important to ensure continuity of consent if there are any changes in the patient’s condition or the treatment/diagnostic offered that may make a difference to the patient’s decision.

Guidelines also make it clear that consent can be implied or explicitly expressed by the patient. Expressed consent may be expressed orally or in writing. Obtaining expressed consent is suggested when in doubt over the patient’s decision.

Furthermore, the ethical implications of medical consent depend on its context, whether it is sought in the context of care for a patient (including diagnostic interventions such as prenatal tests) or in the context of medical research, for example. The present study is only interested in the concept of informed consent to treatment (including diagnostics) and will thus ignore other instances of consent, such as that given to interventions performed in the context of research, where the person giving consent may not directly benefit from the intervention.

Written consent

Written consent is unambiguously not considered to constitute informed consent: “The explanation given by the physician, the dialogue between physician and patient about the proposed treatment, is the all important element of the consent process.” (57) While some Canadian jurisdictions legally require the completion of a written consent form before particular medical interventions may take place (e.g., all surgical procedures), “a signed consent form will be of relatively little value [in court] if […] the explanations were inadequate or, worse, were not given at all” (57).

Of note is the empirical evidence demonstrating that having signed a written consent form is no guarantee that the patient has understood what they allegedly consented to (60, 61). In some

33

circumstances, in follow-up interviews, patients think that they selected the opposite of what their signed consent form indicates (62).

Why is written consent mistaken for informed consent?

It is worthwhile to turn to the history of the use of signatures in formal contexts when trying to answer the above question. Scholars of art history have claimed that signatures in European visual art have served three principal functions: “to claim presence and ‘presentness’ on behalf of the artist; secondly, to assert claims to ‘property’ and inheritance; and finally, to guarantee originality” (63). Arguably, the second function – of property and inheritance – applies less to medical consent forms (or other contexts where signatures are taken for granted, such as on identification cards or some forms of sales receipts, for example), as it is not obvious that something of value is claimed as a result of signing the consent form. Signing to claim “presentness” – “Yes, I was here and paying attention when this document was signed” – and originality – “It was, indeed, me who agreed to the procedure, and not someone else” – do apply.

While classical painting provides a very visible example (pun not intended) of the use of signatures to represent value of some kind, it is obviously not the only example of the ritualization of signatures in modern European culture. Legal contracts and witnesses signing to attest to their witnessing are other obvious examples. Historians suggest that the use of the signature to attest to ‘presentness’ and authenticity in the legal context emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in colonial North America, where people found themselves forming relationships with people from outside of their communities and were looking for ways of fixing identities and relationships where these were unusually (to their participants) unfixed (64). Similarly, when the relationship with the people who traditionally knew us best – our physicians – is unfixed, as it often is in modernity, medical consent forms provide this appearance of fixing “identities and certainty amid the fear of untethered relationships and the dubious morality of relationships produced through research” (65).

There has also been work on the history of informed consent in the medical context, particularly that of Laura Stark (66). She argues that the dominance of the signed consent form in the US

34

beginning from the 1950s was due not to ethicists’ demands or arguments that signing consent forms would make the decision taken more informed and autonomous. She concludes that the rising dominance of signed consent was rather the result of NIH lawyers advising its use to protect the NIH in lawsuits brought by research participants. Hoeyer and Hogle claim that it was not until the late 1970s and the Belmont Report that signed consent procedures were “powerfully reformulated […] from a matter of liability to a means of patient protection by way of guaranteeing ‘anonymity’ to individual patients” (2). Nevertheless, although the purpose of signing consent forms may have been “reformulated”, one may entertain the notion that if the reformulated purpose is subscribed to by the signatories, then maybe the ritual of signing consent forms has come to make actual informed consent “come into being” (65). Nevertheless, Ross reminds us that consent forms “do not inevitably produce and ensure ethical interactions. At best, they produce interactions that accord with a formalist understanding of relationship, as something that can be mediated and moderated by law” (67). A formalist legal understanding of signatures ascribes it three main functions:

(1) “Finality function. The signature should make it clear that the signed document represents a completed declaration of will, and not just a draft which the signatory did not intend to be bound by.”

(2) “Cautionary function. A signatory should be made aware that by his signature he is entering into a binding transaction.”

(3) “Evidentiary function. A party should in case of dispute be able to use a signature for evidentiary purposes.” (68)

The first two functions are incompatible with the principle of ongoing informed consent. The implications of agreeing to undergo prenatal screening are very different from those of, say, buying a house, or entering into a marriage. That a patient signs a consent form in no way suggests that the patient cannot change their mind and opt out of the procedure in question. We are thus left with only the third function, for potential use in case of dispute.

One way in which signing a consent forms can attest to a form of willfully uninformed consent is when patients make a point of visibly not reading the consent form before signing it, as a way of showing how much trust they place in the researcher, on the one hand asserting their agency

35

while demonstrating that this agency is purposefully uninformed (69). This paradoxical way of seemingly asserting one’s autonomy does not, in fact, satisfy the SDT requirements of full autonomy.

Wynn and Israel write that written consent forms “are types of rhetoric that use symbols of powerful institutions and cultural forms that evoke rationality and modernity in order to persuade that consent and ethical research practice have coalesced into a material format” thus elevating the consent form to “fetish1-like” status “symbolizing transparency and ethicality” even though they “neither document nor materialize ethical research relationships” (65). The reason that some ethics boards confuse written consent for informed consent is made more clear by Hoeyer and Hogle’s distinction between ‘politics of intent’ and ‘politics of practice’, where failure in practice to achieve informed consent by means of written consent only “seems to strengthen the political force of the intentions. The politics of intent operates in a moral domain: The stated intentions signal what ‘ought’ to be” (2).

AUTONOMY

The definition of autonomy used in the present research is that of Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Reproductive autonomy simply refers to autonomy in the context of decisions regarding one’s options of reproducing (or not).

SDT defines a person as being autonomous when “his or her behavior is experienced as willingly enacted and when he or she fully endorses the actions in which he or she is engaged and/or the values expressed by them” (70). This definition of autonomy is thus constituted of two elements: 1) voluntariness of enacting the behavior, and 2) either endorsement of the actions or alignment of the values expressed by the actions with one’s personal values. Both of these elements are required in order for the behavior to be said to be autonomous.

Ryan & Deci claim that for an act to be fully autonomous, it must be “endorsed by the whole self”, “fully identified with” and “owned” (71). Conversely, for an act to be considered less than fully autonomous, it would lack “full endorsement” by the person. Such less than full endorsement

36

could, for example, consist of an inner conflict over whether the act is wholly in line with our values, or in an active avoidance of reflection regarding the extent of alignment of values (71). Such a definition of autonomy goes further than the authors of the Belmont Report were willing to go when they claimed that “an autonomous person is an individual capable of deliberation about personal goals and of acting under the direction of such deliberation” (72). The SDT definition requires more than simple ability to deliberate about goals in such a manner; it actually requires for the values expressed by the act to align with one’s “core” values. However, it is interesting to note that the SDT definition does not contradict the Belmont definition, but rather refines it.

The concept of reflective autonomy as defined by SDT is coherent with the philosophy of Cornelius Castoriadis, arguably the 20th century philosopher who focused most on autonomy. Castoriadis wrote that “autonomy comes from autos-nomos: (to give to) oneself one’s laws. […] it is hardly necessary to add: to make one’s own laws, knowing that one is doing so” as well as that autonomy “does not consist in acting according to a law discovered in an immutable Reason and given once and for all. It is the unlimited self-questioning about the law and its foundations as well as the capacity, in light of this interrogation, to make, to do and to institute (therefore also, to

say)” (73). The SDT working definition of autonomy is thus coherent with Castoriadis’ thought

on the subject.

If we take the SDT definition to be complete, meaning that the autonomy of an act does not depend on anything more than the elements present in the definition, we arrive at the following corollary: Autonomy does not require an absence of external influences. All autonomy does require is that these external influences: 1) not violate the voluntariness of an act, and 2) not contradict the values that one is trying to express with the act. Interestingly, Ricoeur acknowledged as early as 1966 that autonomy need not entail an absence of external influences, pressures, or mandates to act (74). We see, therefore, that autonomy is not equivalent to independence nor does autonomy require individualism or separateness in order to be applicable (75). SDT makes very clear that “the opposite of autonomy is not dependence but rather heteronomy, in which one’s actions are experienced as controlled by forces that are phenomenally alien to the self or that compel one to behave in specific ways regardless of one’s values or interests” (70).

The requirement that the values expressed by an act align as much as possible with the patient’s own deeply held personal values means that even if she acts in a manner that completely agrees

37

with how her HCP is obviously trying to compel her to act in, such behavior is still autonomous if her values align with those of the HCP. In fact, Deci & Ryan recognize that “other people” could be an “important source of autonomy”, granted they behave in an “autonomy-supportive and noncontrolling manner” (76, 77).

Figure 1. Autonomy Is Not Independence

The distinction between reflective autonomy and reactive autonomy developed by Koestner and colleagues (78-80) helps us understand that autonomous decision-making does not require independence. While reflective autonomy is the autonomy defined within SDT, reactive autonomy is the “propensity to be resistant to external influences” (70), or what we sometimes call contrarianism. Within the confines of SDT, it is easy to see that resisting external influence may easily violate one’s autonomy, if that external influence went in the direction of one’s own values and interests to begin with.

Another useful lesson from SDT regarding autonomy is that of the continuum of motivations (71, 81). The continuum ranges from full heteronomy to full autonomy, and passes through intermediate stages, thus getting rid of any possible binary dichotomy between autonomy and heteronomy and introducing a gradient. The most heteronomous forms of motivation are externally

38

namely fear of external punishment or desire of external compensation. If one acts only in order to avoid to punishment or to reap the rewards, without considering how such acts align with our own values, one is clearly not acting autonomously as defined by SDT. Less heteronomous would be introjected motivation, which reflects “the partial assimilation of external controls”. In other words, one acts either in order to feel the approval of one’s actions by others, or to avoid being Figure 2. Gradient of Heteronomous Motivations

judged for those acts, but where no external reward or punishment act as motivators. Further along the gradient are identified motivations that “reflect a personal valuing of the actions”. That is, my motivations are identified, if I act in a certain manner, because I believe, after deliberation, that this is the most morally correct course of action, even in the absence of other persons to witness my act, something Kant could probably get behind. Finally, Ryan & Deci define integrated

motivations as those that are “both personally valued and well synthesized with the totality of one’s

values and beliefs”, which is equivalent to satisfying the “full endorsement” criterion of autonomy.

Why use the SDT definition of autonomy?

In particular, using the SDT definition of autonomy allows us to see that the concept of informed

consent can theoretically satisfy both criteria of autonomy, whereas written consent can only

satisfy the voluntariness criterion and not the values (or “informed”) criterion. Furthermore, we also see that nondirective counseling does not necessarily ensure autonomous decision-making, while it does ensure reactive autonomy.

In general, using the SDT view of reflective autonomy avoids the pitfalls that more widely used definitions of autonomy (82, 83) in the bioethics tradition are vulnerable to. Fagan defines the two key criteria for determining whether someone acts in an autonomous fashion as: 1) “whether the

39

patient possesses the cognitive capacity for autonomous deliberation” and 2) “whether the patient [is] free from undue external coercion or manipulation in [their] deliberations” (84), completely ignoring evaluating whether the action in question aligns with the agent’s values (criterion 2 in the SDT view). This classical definition in bioethics “assume[s] a strong view of individuality and agency”, where the individual is seen as “wholly and even necessarily sufficient, self-determined, self-guided—in a word, atomistic—and who is entirely free to make his or her own choices independent from social inputs” (85). Such a strong foundation of autonomy in individuality can historically be traced to the Kantian atomistic concepts of “moral agent” and “good will” (86). “The ‘good’ will is purely autonomous, free from contingencies and inclinations” (87), while a moral agent is an individual capable of making rational decisions compatible with their rationally formed life plan, and who assumes responsibility for the consequences of their choices (88).

While such an individualist account of autonomy is logically circumscribed within the tradition of classical Western philosophy, it has been criticized widely, being accused of “having no connection to the empirical world” (85, 87, 89-96). The atomism inherent in such a view of personhood and autonomy has been criticized on account of people’s sense of identity “occupying a place in an historical and social order of persons, each of whom has a personal history interwoven with the history of a community” (90), whereas individualist autonomy has been labeled as “noncontextual and based on an abstract concept that the individual is isolated and disconnected from the many relationships within which he or she actually exists” (95). Even one of the godfathers of North American bioethics, James F. Childress has warned that “the principle of respect for autonomy is ambiguous because it focuses on only one aspect of personhood, namely self-determination . . . we would have to stress that persons are embodied, social, historical, etc.” (91). Indeed, even within the parameters of Kantian moral agents establishing their values and interests within what a “good life” is for them, such considerations are necessarily impacted by the “situated and relational social determinants of the individual”, determinants that individualist autonomy fails to take into account (85). Furthermore, personal values “are not the hidden and privileged property of the individual [… but] take shape publicly” (93). As the relational view of a person is a “location in a web of relatedness to others” (96), instead of an atomistic moral agent, autonomy must also be seen as “both reciprocal and collaborative […] in that it is not solely an individual enterprise” (94).