HAL Id: dumas-02420858

https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02420858

Submitted on 20 Dec 2019HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Evaluation of the reasons for not discontinuing

potentially inappropriate medications after a medication

multidisciplinary review in an acute geriatric care unit

Cindy Riffard

To cite this version:

Cindy Riffard. Evaluation of the reasons for not discontinuing potentially inappropriate medications after a medication multidisciplinary review in an acute geriatric care unit. Pharmaceutical sciences. 2019. �dumas-02420858�

AVERTISSEMENT

Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le

jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la

communauté universitaire élargie.

Il n’a pas été réévalué depuis la date de soutenance.

Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci

implique une obligation de citation et de référencement

lors de l’utilisation de ce document.

D’autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite

encourt une poursuite pénale.

Contact au SID de Grenoble :

bump-theses@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

LIENS

LIENS

UNIVERSITÉ GRENOBLE ALPES UFR DE PHARMACIE DE GRENOBLE

Année : 2019

EVALUATION DES SITUATIONS MOTIVANT LE MAINTIEN DES MEDICAMENTS POTENTIELLEMENT INAPPROPRIES SUITE A UNE

REEVALUATION PLURIDISCIPLINAIRE EN HOSPITALISATION EN MEDECINE AIGUE GERIATRIQUE

MÉMOIRE DU DIPLÔME D’ÉTUDES SPÉCIALISÉES DE PHARMACIE HOSPITALIERE - PRATIQUE ET RECHERCHE

Conformément aux dispositions du décret N° 90-810 du 10 septembre 1990, tient lieu de

THÈSE

PRÉSENTÉE POUR L’OBTENTION DU TITRE DE DOCTEUR EN PHARMACIE DIPLÔME D’ÉTAT

Cindy RIFFARD

THÈSE SOUTENUE PUBLIQUEMENT À LA FACULTÉ DE PHARMACIE DE GRENOBLE

Le : 03/05/2019

DEVANT LE JURY COMPOSÉ DE Président du jury :

M. le Professeur Pierrick BEDOUCH

Membres :

Mme. le Docteur Prudence GIBERT (directrice de thèse) Mme. le Docteur Armance GREVY (directrice de thèse) M. le Professeur Gaëtan GAVAZZI

Mme. le Docteur Christelle MOUCHOUX

L’UFR de Pharmacie de Grenoble n’entend donner aucune approbation ni improbation aux opinions émises dans les thèses ; ces opinions sont considérées comme propres à leurs auteurs.

Remerciements

Aux membres du jury : A Pierrick : merci de nous donner le goût de la pharmacie clinique durant ces années d’étude et de me faire l’honneur de présider ce jury. A Prudence et Armance (rebaptisées « Prumance » pour l’occasion !): pour m’avoir proposé ce sujet. Merci pour vos idées, votre patience et pour le temps consacré à ce projet. A Gaëtan : merci pour tous vos conseils et vos idées pendant ces 6 mois de stage. Merci d’avoir accepté de donner votre avis sur ce manuscrit. A Christelle Mouchoux : merci d’avoir accepté de lire ce travail et de participer à ce jury. A l’équipe du service de gériatrie et à mes collègues Merci à toute l’équipe de la gériatrie pour ces 6 mois passé avec vous. Travaillez avec vous est facile et enrichissant. Merci en particulier à Clara qui a consacré du temps à la relecture de mes travaux en anglais. A Gag’house, Violetta et Florentin, que j’ai harcelé avec les IPP ! Sans vous cette étude n’aurait pas pu voir le jour. Merci à vous pour ces 6 mois !A tous les externes qui sont passés en gériatrie et qui ont participé au recueil de données notamment à Julie et Raph qui m’ont particulièrement aidé.

A la team de la pharmacovigilance, merci à vous pour ces 6 mois de stage au top, tant sur le plan professionnel, que sur le plan humain. Merci pour tous ces moments hors stage, notamment

les nombreuses activités « brillamment » organisées par Claire, reine du Doodle et FFR à ces heures perdues ! J’espère avoir une revanche à un escape game ! A ma famille A mes grands-parents, qui je pense, auraient été très fiers de mon parcours. En ce jour spécial, votre absence est d’autant plus difficile. A ma maman, merci pour ton soutien sans faille, et pour toujours tout donner pour Louis et moi, je n’en saurais pas ici sans toi. Merci de m’avoir remonté le moral pendant les petits coups de moins bien de ces derniers temps. A mon frère : pas besoin de grandes phrases pour savoir qu’on peut toujours compter l’un sur l’autre, c’est bien la l’essentiel. Merci également à Camille qui a pleinement intégrée la famille, merci notamment pour ton écoute et tous ces moments passés ensemble. A ma tante, Emmy et Flo, merci pour votre soutien de toujours et pour votre présence. A toute la famille Gambier/Guichard, qui m’a si bien accueilli dans leur famille. Merci à vous pour votre soutien et votre patience pendant mes longues heures de révision. A mes amis

A Madison, Guigui, Erwan, copains depuis la maternelle ! Une amitié qui dure même si on n’a pas réussi à s’évader de la cour de récré en passant sous le toboggan !

A mes copains de lycée : Laety, Gael, Benji, Laury, Chris, Nico. Merci à vous d’être la depuis toutes ces années et pour toutes ces soirées passées et à venir (le 31 août approche !).

A la Team C.A.C.A. la plus belle rencontre de ces études sans doute. Merci à vous pour tous ces anniversaires, soirées, vacances passés avec vous. Merci Aniss pour les trousses de cheveux, les sétrons dans les pâtes (j’en ris encore sans pouvoir expliquer le sens de cette phrase) sans toi les amphis aurait été bien triste, Caro ma partenaires de TD, merci pour toutes tes pépites (l’allergie à l’oxygène restera sans doute la meilleure), Ariane, merci pour ton naturel, Alicia merci pour tant de chose, notamment pour ta présence pendant les coups de déprime sans qu’on soit obligé de parler ; à nos nouvelles aventures en coloc ;)

A toutes mes « collègues » rencontrées pendant ces 4 ans et devenues amies: Maelle, Elisa, Laura, Dodo, Monia. Merci à vous pour ces pauses café et pour avoir égayé les repas de l’internat ! Ces soirées en toute « discrétion » au Brugs m’ont bien aidé à déstresser ! A Lolo, le coloc merci d’avoir accepté de relire les parties en anglais jusque tard le soir ! A Driou, qui me supporte et me soutient depuis maintenant 10 ans, merci pour ta présence, ta patience, ton amour (et tes repas sans lesquels je serais nourrie au jambon et aux yaourts !). A nous et nos projets, je sais qu’ensemble nous surmonterons les obstacles présents sur notre route.

Table des matières

Index des figures et tableaux ... 9

Liste des abréviations ... 10

Introduction ... 11

Présentation de l’article ... 20

Introduction ... 20

Patients and methods ... 23

Study design and study population ... 23

Objectives and endpoints ... 23

Unit description and pharmaceutical presence ... 23

Potentially inappropriate medication identification and multidisciplinary medication review ... 24

Continuity of care ... 25

Three months follow-up ... 25

Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) and collected data ... 26

Statistical analysis ... 26

Results ... 27

Population’s characteristics ... 27

Potentially inappropriate medication at admission and at discharge ... 29

Potentially inappropriate medication prescription three months after the hospital discharge ... 32 Discussion ... 37 Conclusion ... 44 Discussion ... 45 Conclusion ... 55 Bibliographie ... 58 Annex ... 65

Annex 1: Example of drug reconciliation table ... 65

Annex 2: Typology of potentially inappropriate medication identified at admission, discontinued after multidisciplinary medication review, introduced and at discharge ... 66

Annex 3: Comparison of potentially inappropriate medication typology between the discharge prescription and three months after the hospital discharge prescription (n=56 patients) ... 71

Annex 4: Comparison of potentially inappropriate medication typology between the admission prescription and three months after the hospital discharge prescription (n=56 patients) ... 73

Annex 5: Les critères STOPP/START.v2: Adaptation en langue française ... 75

Index des figures et tableaux

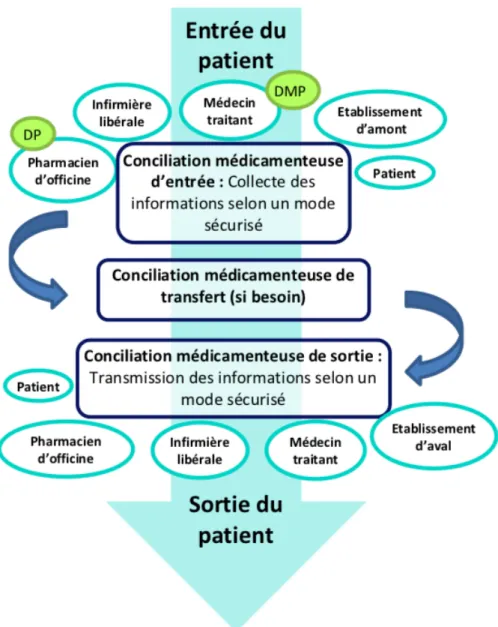

Figure 1: Le parcours hospitalier du patient et les acteurs qui gravitent autour, figure issue

de l'OMéDIT Centre Val de Loire - Accompagnement régional de la conciliation

médicamenteuse ... 18

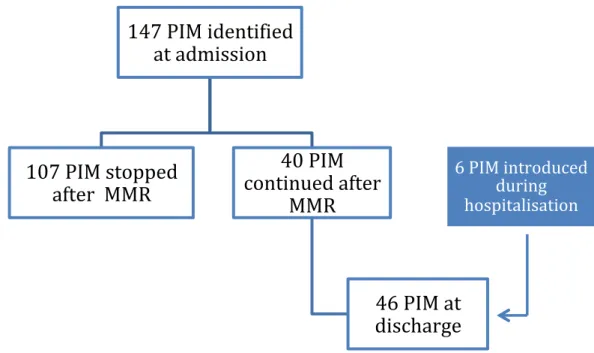

Figure 2: Study's inclusion flow chart ... 27 Figure 3: Flow chart of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) number during

hospitalisation ... 29

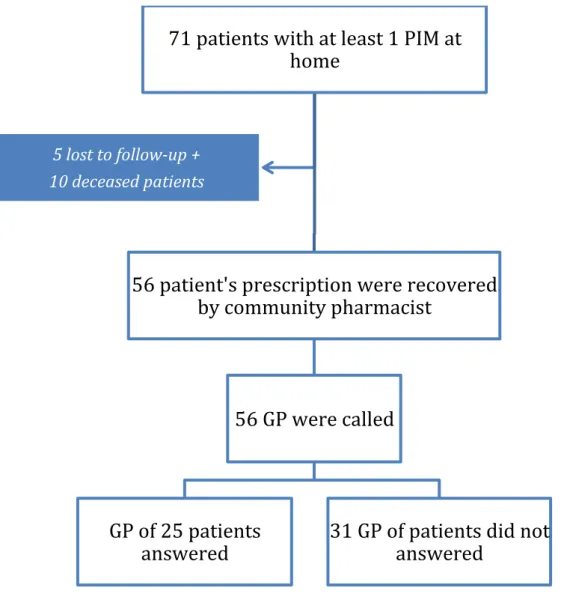

Figure 4: Three months follow-up flow chart ... 33 Figure 5: Flow chart of the potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) number during the

care pathway for the 56 followed patients ... 34

Table I: Distribution of the number of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) per patient ... 28 Table II: Patient's characteristics ... 28 Table III: Clinician's reasons for continuing the potentially inappropriate medication (PIM)

prescription ... 31

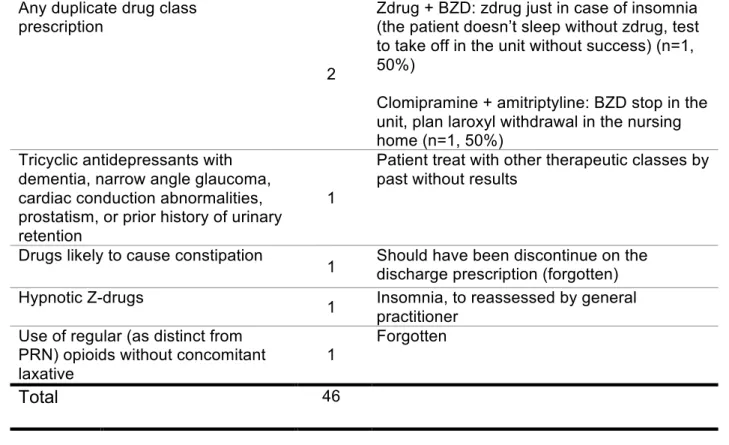

Table IV: Details of clinician's reasons for continuing the potentially inappropriate medication

(PIM) prescription ... 32

Table V: General practitioners' reasons for potentially inappropriate medication (PIM)

Liste des abréviations

• Abréviations françaises

ALD : Affection Longue Durée

AMM : Autorisation de Mise sur le Marché

ANSM : Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des produits de santé CHUGA : Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Grenoble Alpes

CNAMTS : Caisse Nationale de l'Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés HAS : Haute Autorité de Santé

INSEE : Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques IPP : Inhibiteurs de la Pompe à Proton

MPI : Médicament Potentiellement Inapproprié OMS : Organisation Mondiale de la Santé QLS : Qualité de la Lettre de Liaison

REPHVIM : Relations Hôpital-Ville et Iatrogénie Médicamenteuse SFPC : Société Française de Pharmacie Clinique

• Abréviations anglaises

BZD: Benzodiazepines CAF: Chronic Atrial Fibrillation

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease CPOE: Computerized Physician Order Entry GP: General Practitioner

HyperCa: HyperCalcemia HypoK: hypoKalaemia HypoNa: HypoNatremia

MMR: Multidisciplinary Medication Review NAG: Narrow Angle Glaucoma

NSAID: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs OH: Orthostatic Hypotensive

PIM: Potentially Inappropriate Medications PPI: Proton Pump Inhibitors

PRN: Pro Re Nata (as needed)

Introduction

D’ici 2050, la population mondiale des plus de 60 ans va atteindre 2 milliards de personnes contre 900 millions en 2015 d’après l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS) (1). Or, les personnes âgées ont sept fois plus de risque d’être hospitalisées suite à un événement indésirable médicamenteux qu’un jeune adulte (2). Il est donc primordial de prévenir l’iatrogénie médicamenteuse et par conséquent de promouvoir une prescription médicamenteuse adaptée à la personne âgée.

Il existe différentes définitions du vieillissement et de la personne âgée. Pour l’OMS, la personne âgée est une personne de plus de 65 ans alors que pour la Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS), la personne âgée correspond à une personne de plus de 75 ans ou une personne de plus de 65 ans polypathologique. L’institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE) comptabilise de son côté les plus de 60 ans comme des personnes âgées. Cependant, l’âge n’est pas un état pathologique en soi. Les personnes âgées sont une population très hétérogène du fait de l’existence d’un vieillissement variable suivant les individus.

Le vieillissement physiologique est défini comme l’ensemble des modifications se produisant au cours de l’avancée en âge en dehors de toute maladie. Il existe durant ce vieillissement physiologique des altérations responsables de modifications pharmacocinétiques et pharmacodynamiques chez les personnes âgées. Ces altérations peuvent accroitre le risque d’effet indésirable médicamenteux. En effet, toutes les étapes du devenir du médicament dans l’organisme peuvent être perturbées par le vieillissement.

légèrement altérée chez les personnes âgées du fait d’une diminution de la sécrétion gastrique, ce qui conduit à une augmentation du pH gastrique. Ces phénomènes peuvent perturber la dissolution et la solubilité de certains médicaments, notamment pour les molécules basiques. Les conséquences de cette altération sont minimes, la biodisponibilité étant peu modifiée. La vitesse de résorption peut être cependant diminuée et le pic plasmatique plus tardif que chez le jeune adulte (3). La pharmacocinétique des autres voies d’administration a été moins étudiée dans cette catégorie de population, la voie per os étant majoritairement utilisée (4).

La seconde étape est la distribution du principe actif à son site d’action. Du fait d’une diminution de la masse musculaire, d’une augmentation de la masse graisseuse et d’une diminution de l’eau intracellulaire, les compartiments de l’organisme sont modifiés chez la personne âgée. Ces modifications entrainent une augmentation du volume de distribution des molécules lipophiles et une diminution du volume de distribution des molécules hydrophiles. Ces altérations induisent une distribution accrue de certains médicaments au niveau cérébral (en particulier les molécules lipophiles comme de nombreux psychotropes (5)), et peuvent expliquer en partie la plus grande sensibilité des personnes âgées aux effets des psychotropes. La perméabilité plus importante de la barrière hémato-encéphalique est un élément de réponse également. De plus, il existe une diminution de la perfusion sanguine qui peut contribuer à un délai d’action du principe actif retardé chez la personne âgée, du fait d’un temps de transport plus important jusqu’au site d’action.

Les médicaments sont ensuite principalement métabolisés au niveau hépatique. Il existe au cours du vieillissement une diminution du volume du foie ainsi qu’une diminution du débit sanguin hépatique. De plus, le pouvoir métabolique hépatique

la biodisponibilité ainsi qu’une augmentation de la demi-vie d’élimination sont attendues.

L’élimination est la phase la plus impactée par le vieillissement. L’élimination de certains médicaments est essentiellement rénale. Durant l’avancée en âge, il existe des modifications anatomiques rénales : diminution du poids des reins, diminution du nombre de glomérules ; ainsi que des modifications fonctionnelles : diminution du flux sanguin rénal, diminution de la filtration glomérulaire, de la sécrétion et de la réabsorption tubulaires (6). Ces modifications peuvent expliquer une diminution de l’élimination des médicaments principalement excrétés par voie rénale, et donc un allongement de leur demi-vie d’élimination, avec pour conséquence un risque de surdosage, et donc de survenue d’effet indésirable plus important.

D’autre part, des modifications sur le plan pharmacodynamique ont été rapportées chez la personne âgée. Les modifications pharmacodynamiques sont le résultat principalement d’une diminution du nombre de récepteurs, d’une altération de leur affinité, ou de leur système de régulation. Pour exemple, des diminutions du nombre des récepteurs dopaminergiques ont été décrites, et augmentent le risque de développer un syndrome parkinsonien en cas de prise de neuroleptique. De même, une diminution de la sensibilité de barorécepteurs a été montrée dans cette population, ce qui accroit le risque d’hypotension orthostatique en cas de prise de traitement antihypertenseur. La personne âgée est également connue pour avoir une sensibilité plus importante du système nerveux central aux benzodiazépines (7)(8). De par ses modifications pharmacocinétiques et pharmacodynamiques, la personne âgée est plus susceptible de présenter des effets indésirables médicamenteux. Néanmoins toutes ces altérations dans les étapes du devenir du médicament dans l’organisme sont marquées par une forte variabilité interindividuelle, il est donc difficile d’en évaluer l’impact précisément.

D’autres facteurs majorent le risque d’effet indésirable dans cette population, notamment la polymédication bien souvent associée à la polypathologie. En effet, d’après une cartographie de la CNAMTS (Caisse Nationale de l'Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés), 40 à 70% des plus de 75 ans sont traités pour plusieurs pathologies (9). En conséquence de cette polypathologie, 50% des plus de 75 ans consomment au moins 7 principes actifs différents régulièrement (au moins trois dates de délivrance dans l’année) (9). Cette polymédication entraine évidemment un risque supplémentaire d’iatrogénie, d’une part, par de possibles interactions médicamenteuses, d’autre part, via un cumul d’effets indésirables.

L’iatrogénie médicamenteuse est donc un problème de santé publique. Elle serait responsable de 10 à 20 % des hospitalisations des plus de 75 ans (10). Dans le but de limiter l’iatrogénie chez les personnes âgées, la notion de médicament potentiellement inapproprié (MPI) est née. La définition historique des MPI correspond à des médicaments dont le risque d’effet indésirable chez la personne âgée est supérieur au bénéfice attendu, ou à des médicaments dont l’efficacité est discutable par rapport à d’autres alternatives. Cette définition a ensuite été élargie et trois types de MPI ont été définis : l’underuse (la sous-prescription), le misuse (la prescription inadaptée : posologie, classe thérapeutique, durée de la prescription non adaptées) et l’overuse (la sur-prescription). La prévalence des MPI est estimée entre 21.4% et 79% d’après une revue de la littérature de 2013 (11).

La première liste pour aider les professionnels de santé à détecter les MPI a été proposée par la société américaine de gériatrie: il s’agit des critères de Beers (12). Ces critères sont peu utilisés en Europe car cette liste n’est pas adaptée aux

détection de MPI : la liste STOPP/START (Screening Tool of Older Person's Prescriptions / Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Cette liste est basée sur un consensus de gériatres et pharmacologues anglais et irlandais. Elle est régulièrement mise à jour (Version 1 en 2008 (13) puis version 2 datant de 2015 (14)), et une adaptation en Français a également été réalisée par Lang et al, ce qui facilite son utilisation pour notre pratique (15). Ces listes permettent de détecter plus facilement les MPI. Cependant, il est important de rappeler que les MPI ne sont pas des médicaments contre-indiqués. En effet, ils sont considérés seulement comme potentiellement inappropriés. Cela signifie qu’une réévaluation au cas par cas est indispensable. La prévalence des MPI est conséquente dans la population gériatrique : en sélectionnant seulement les études qui ont appliqué la version 2 de la liste STOPP/START, la prévalence est comprise entre 42,1% et 88,5% chez les personnes âgées hospitalisées (16). Il a été démontré que la prescription de ces MPI est associée à des effets indésirables, et à des hospitalisations chez les personnes âgées (17–19). D’après plusieurs études, la liste STOPP/START permettrait de détecter plus de MPI que la liste de Beers, et les MPI détectés seraient plus souvent associés à des effets indésirables conduisant à une hospitalisation (17–19). De nombreuses études ont mis en évidence que les réévaluations de prescription, à l’aide de ces listes, permettaient de considérablement réduire le nombre de MPI lors d’une hospitalisation, ou durant les consultations médicales des médecins généralistes (20–22). L’étude de M. Cabaret et P. Gibert a permis par exemple de réduire de 37,6% les MPI grâce à une réévaluation des prescriptions à l’aide des critères STOPP suite à une unique consultation chez le médecin traitant (22). Malgré la mise en place de ces réévaluations de prescription, certains MPI subsistent sur les prescriptions de sortie d’hospitalisation. Par exemple, dans l’étude de Bahat et al (20) 14,7% des MPI n’étaient pas arrêtés après une réévaluation de la prescription

par des gériatres chez des patients âgés en hospitalisation de jour. Nous pouvons donc nous demander la raison du maintien de ces MPI. Ces médicaments sont-ils toujours considérés inappropriés au vu de la situation médicale du patient ? Sont-ils laissés suite à un oubli, ou l’arrêt du médicament n’a pas pu être initié pendant l’hospitalisation ? A notre connaissance, peu de travaux ont étudié les MPI non arrêtés suite à une réévaluation et les raisons de leur maintien.

Par ailleurs, une fois la réévaluation médicamenteuse réalisée, il est indispensable de communiquer les modifications de traitements, et les raisons motivant ces modifications, aux autres professionnels de santé en charge du patient pour permettre la continuité des soins. Il a été montré que la represcription de médicaments arrêtés pendant une hospitalisation résultait fréquemment d’un manque de communication entre professionnels de santé (23,24). Les résultats de la thèse du Dr Singlard montrent que 60% des modifications de traitements justifiées dans le courrier de sortie, après une hospitalisation dans un service de gériatrie, sont poursuivis par le médecin traitant, contre seulement 23,5 % des modifications respectées lorsqu’il n’y a pas d’explication associée (25). Les explications des changements de traitement durant une hospitalisation sont des informations utiles et souhaitées par les médecins traitants, mais également par les pharmaciens d’officine (26)(27).

Le pharmacien d’officine est encore trop peu intégré lors de la sortie d’hospitalisation des patients. Son rôle à l’admission du patient n’est plus à démontrer : en effet, il est de plus en plus sollicité dans le cadre de la conciliation des traitements médicamenteux à l’entrée. Il constitue une source d’information primordiale puisqu’il

différents médecins du patient. La pharmacie peut également fournir des informations concernant la consommation en automédication, en phytothérapie… Concernant la conciliation médicamenteuse, la Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) a émis un document visant à sensibiliser et accompagner les différents professionnels de santé et les patients à cette démarche (28). La figure 1 représente les différentes conciliations médicamenteuses réalisées durant le parcours hospitalier du patient avec les différents acteurs qui gravitent autour de celles-ci. Intégrer l’ensemble de ces acteurs sur l’intégralité du parcours de soins semble nécessaire pour améliorer la continuité des soins. Les pharmaciens d’officine sont en effet demandeurs d’informations concernant les changements thérapeutiques issus de l’hospitalisation, d’une part, pour ne pas être surpris des divergences avec les précédentes prescriptions, et d’autre part, pour fournir les mêmes informations et conseils aux patients que celles transmises pendant l’hospitalisation concernant les arrêts ou introductions de traitement (27). L’étude multicentrique REPHVIM (Relations Hôpital-Ville et Iatrogénie Médicamenteuse) a mis en évidence que la conciliation de sortie couplée à la transmission des informations au pharmacien d’officine permettait de diminuer de 22 % le nombre d'erreurs à la sortie, ainsi que de 32% le nombre de ruptures thérapeutiques (29).

Figure 1: Le parcours hospitalier du patient et les acteurs qui gravitent autour, figure issue de l'OMéDIT Centre Val de Loire - Accompagnement régional de la conciliation médicamenteuse

La pharmacie clinique est une discipline particulièrement développée au sein du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Grenoble Alpes (CHUGA). Selon la société française de pharmacie clinique, « la pharmacie clinique est une discipline de santé centrée sur le patient, dont l’exercice a pour objectif d’optimiser la prise en charge thérapeutique, à chaque étape du parcours de soins. Pour cela, les actes de

recours aux produits de santé. Le pharmacien exerce en collaboration avec les autres professionnels impliqués, le patient et ses aidants » (30). Dans le service de médecine aiguë gériatrique du CHUGA, un interne en pharmacie clinique et deux externes en pharmacie sont intégrés à l’équipe médicale et réalisent une conciliation médicamenteuse d’entrée pour tous les patients. Cette conciliation médicamenteuse d’entrée a pour objectif de s’assurer de la continuité entre la prescription habituelle du patient et la prescription hospitalière. Depuis plusieurs années, la conciliation médicamenteuse de sortie est également en déploiement. En 2014, Mélanie Moulis a mis en place dans ce service des bilans de médication de sortie pour les patients qui ont bénéficié de changements importants dans leur traitement habituel (31). L’envoi de ce bilan de médication de sortie aux médecins traitants a montré un effet bénéfique sur le maintien des optimisations thérapeutiques à la sortie. De même, la réévaluation des médicaments potentiellement inappropriés est un sujet au cœur de différents travaux dans notre établissement. En 2016, la thèse de Marie Richard a confirmé une forte prévalence des MPI à l’admission de patients âgés, et a montré une diminution de ces MPI à la sortie. Cependant, 37% des MPI restaient maintenus en sortie d’hospitalisation. A la suite de cette étude, nous avons donc cherché à connaître les raisons pour lesquelles ces MPI sont maintenus.

L’objectif principal de cette étude est donc d’évaluer le caractère approprié ou non des MPI détectés par la liste STOPP/START V2 et maintenus après réévaluation pluridisciplinaire en hospitalisation dans un service de gériatrie aiguë. L’objectif secondaire est de décrire l’évolution du nombre de prescriptions de MPI du sujet âgé au cours de son parcours de soins, intégrant cette réévaluation pluridisciplinaire de la prescription en cours d’hospitalisation.

Présentation de l’article

Introduction

Drug Adverse reactions represent a public health issue since they lead to 10-30% of seniors’ hospitalisations (32–36). As a result of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes, but also as a result of comorbidities and polypharmacy, an elderly population is more likely to present adverse effects. Furthermore, inappropriate drug prescription in older people is also an iatrogenic illness source (16,17,19). Potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) are defined as drugs with an unfavorable benefit-risk balance in elderly population or drugs of a questionable effectiveness. The estimate prevalence of PIM prescription varies from 21.4% to 79% according to a litterature review in 2013 (11). Therefore, drug prescription in older people needs to be regularly reassessed in order to re-evaluate the drug benefit/risk ratio.

Tools can help health professionals to detect these inappropriate prescriptions. The American Geriatrics Society was the first to suggest a list of criteria to detect PIM: the Beer’s criteria (12). However this list is difficult to apply in France because drugs in Europe are different from the ones in the USA. In 2008, an Irish research team published the STOPP/START list (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment) based on a consensus of Irish and English geriatricians and pharmacologists (13). This tool is more adapted to European practice. The STOPP/START list has been updated in 2015 (14). Studies using version 2 of the STOPP criteria reported a PIM prevalence between 42.1% to

associated with adverse effects (17–19). It should be noted that these lists record drugs that are potentially inappropriate but are not definitely contra-indicated. These PIM must be revaluated in conjunction with the patient’s medical situation.

To decrease the risk of adverse effect, health professionals have implemented different interventions to decrease PIM prescription. Amongst these interventions, implementation of prescriptions review with STOPP/START list has shown PIM decrease (20, 21). For example, the study of M. Cabaret and P. Gibert led to a 37.6% PIM reduction through a prescription re-evaluation using STOPP criteria with a single consultation by the general pratictioner (22). Besides, studies on drugs deprescription show that deprescription appears to be feasible and generally safe and may improve longevity (37). In the literature, we find a 37.6 to 87% reduction in the number of PIM after a prescriptions review (20,22,38). However, not all PIM prescriptions are stopped following prescriptions review. In G. Bahat’s study 14.7% of PIM are not discontinued after review (20). One can ask whether PIM detected but not discontinued are really inappropriate. To our knowledge, few studies have studied PIM not discontinued after a prescription review and examined the reasons why.

Moreover, it is also important after a medication review to communicate modifications of drugs prescription to patient’s health professionals. This transmission allows a better continuity of care and avoids the PIM re-prescription remote from hospitalisation. General practitioners (GP) and community pharmacists need data explaining drug therapy changes during hospitalisation to improve continuity of care and to better inform and advise patients (26). Indeed, several studies show that drugs re-prescription remote from hospital discharge are the result of a lack of communication (23). Drug modifications are more often continued in case of explanation of them in the discharge letter (25).

The main objective of the study is the evaluation of the appropriateness of detected PIM with STOPP criteria v2 and continued after a medication multidisciplinary review in an acute geriatric unit. The secondary objective is to describe the evolution of PIM prescription during the care pathway of older patients, integrating a medication multidisciplinary review during hospitalisation in a geriatric unit.

Patients and methods

Study design and study population

This was a prospective, non-controlled study performed in an acute geriatrics unit at the Grenoble-Alpes University Hospital, including patients over 75 years old hospitalised from January to April 2018. Patients deceased or transferred into another unit during hospitalisation were excluded. Readmissions during the study period were also excluded.

Objectives and endpoints

The main study’s objective is the evaluation of the appropriateness of detected PIM with STOPP criteria v2 and continued after a multidisciplinary medication review in an acute geriatrics unit. The secondary objective is to describe the evolution of PIM prescription during the care pathway of older patients integrating a medication multidisciplinary review during hospitalisation in a geriatric unit.

The primary endpoint is the proportion of continued justified PIM on the discharge prescription compared to all continued PIM. The secondary endpoint is the number of PIM per patient at admission, at discharge and three months after the hospital discharge.

Unit description and pharmaceutical presence

This acute geriatric unit is a 24-bed unit managed by 4 physicians and 4 medical residents. A clinical pharmacy resident, under the responsibility of clinical

pharmacists, and two pharmacy students are integrated into the health care team. All drug prescriptions in the unit are analysed and validated by the pharmacy resident.

Potentially inappropriate medication identification and multidisciplinary medication review

On admission of each patient, pharmacy students and the pharmacy resident realize a medication reconciliation. The medication reconciliation consists of recording a complete medical history and a list of all drugs taken by the patient (prescribed or not). The objective is to compare this list with the admission prescription, identify discrepancies, and discuss with prescribers if those discrepancies are justified or not. During medication reconciliation and at each pharmaceutical validation of drug prescription, pharmacists identify PIM according to the French adapted version 2 STOPP criteria (15). START criteria are not considered for this study. Thereafter, those drugs are reassessed with a multidisciplinary team composed of pharmacy students, pharmacy resident, medical residents and geriatricians. The aim of this multidisciplinary medication review (MMR) is to evaluate for each patient if PIM prescriptions detected are really inappropriate or not, and to decide to continue them or to plan their discontinuation. Clinician’s reasons for not discontinuing PIM have been recorded and classified in 4 classes: need for treatment after medical analysis and without safe alternatives, need for treatment for the hospitalisation time but to reassess remote from hospitalisation by the GP, drugs with a questionable indication to be reassessed by the specialist doctor (lack of information) and/or by the GP, and drugs discontinuation forgotten. We considered the reasons for PIM continuation as justified for the first two types of reasons (need for treatment after medical analysis

and without safe alternatives, need for treatment for the hospitalisation time but to reassess remote from hospitalisation by the GP).

Continuity of care

At discharge, a medication reconciliation is done. This step involves comparing drugs prescribed in hospital with the discharge prescription. Before the patient discharge, physicians then pharmacists explain to patients or caregivers’ treatment modifications (introduction, discontinued drugs, and dosage modifications), and give advice on drug intake and adverse effect.

The discharge letter sent to GPs includes a drug reconciliation table and all drugs changes are explained. Indeed, a drug reconciliation table is inserted with a column “drugs at admission”, a column “drugs at discharge” and a column “comments” to justify medication changes (dosage or drug), to justify reasons to continue or discontinue identified PIM, and also to give guidelines to plan medication discontinue, reduction or reevaluation (cf annex 1). Moreover, this reconciliation table is also sent to the patient’s community pharmacist (if the patient agrees) via the secure messaging if possible. The secure messaging used for this study was MonSISRA deployed by the Auvergne Rhône-Alpes Regional Healthcare Agency that allows health professionals to communicate, share and send documents through an encrypted protocol (39).

Three months follow-up

Three months after the patient’s discharge from hospital, the current prescription was recovered nearby patient’s community pharmacist. Besides, patients’ GPs with a PIM

identified at hospitalisation admission were called to know if PIM prescriptions were changed (PIM discontinued or re-prescribed), and the reasons why. We chose a three-month period because it corresponds to the first prescription renewal, and gives the doctor time to see the patient remote from the hospitalisation and to reassess drugs.

Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) and collected data

All drugs prescriptions are computerized in the unit. Grenoble University Hospital developed its own CPOE system (Cristalnet©, CRIH des Alpes, Grenoble, France). Sociodemographic data (age, gender), hospital stay and living environment at hospital discharge (home or nursing home) were collected. Drugs, drug therapeutic classes, number of prescribed drugs prior to admission and at hospital discharge, number of PIM prescribed prior to admission, at discharge and three-months after the hospital discharge were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

The comparison of normally distributed parametric data was analysed with Student t-test and Wilcoxon signed rank t-test was used for comparison of matched not-normally distributed data. Categorical data were studied by chi-square test. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population’s characteristics

During the study period, 127 patients were hospitalised and 101 patients were included (figure 2). Amongst them, 30 patients had no PIM at admission and 71 (70.3%) had at least one PIM at admission. Amongst the 71 patients with at least one PIM prescription, 27 (38%) had one, 24 (33.8%) had two, 10 (14.1%) had three and 10 (14.1%) had four or more PIM (table I). The patients’ characteristics are summarised in the table II. Average age was 87.4 (+/- 5.6) years old. In the sample of patients with PIM, the average number of drugs at admission was higher than in the sample of patients with no PIM (p<0.01). There is no more difference in the number of drugs at the hospital discharge.

Figure 2: Study's inclusion flow chart (PIM: potentially inappropriate medications)

127 patients

101 patients

included

30 patients without PIM at admision 1 patients with 1 PIM introduced during hospitalisation 29 patients without PIM at discharge71 patients with at least 1 PIM at admission 38 patients whitout PIM at discharge 33 patients with at least 1 PIM at discharge 26 patients excluded: -20 transferred -6 deaths during hospitalisation

Table I: Distribution of the number of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) per patient

Table II: Patient's characteristics (PIM: potentially inappropriate medications)

Variables At

admission

% At

discharge

%

Number of patient with 1 PIM

27 38.0 22 66.7

Number of patient with 2 PIM

24 33.8 10 30.3

Number of patient with 3

PIM 10 14.1 1 3.0

Number of patient with >3 PIM 10 14.1 0 0 Variables Global sample (n=101) Patient without PIM at admission (n=30) Patient with PIM at admission (n=71) P-value

Age (average years) 87.4 87.0 87.6 0.68 Gender (females, n (%)) 56 (55.4) 16 (53.3) 40 (56.3) 0.78 Average number of drugs at

admission

7.5 4.8 8.6 <0,01 PIM number per patient at

admission 1.46 / 2.07

Average number of drugs at discharge

7.5 6.8 7.8 0.12

PIM number per patient at discharge

0.46 / 0.65

Hospital stay (days) 12.8 12.8 12.8 0.99 Patient in nursing home

(n, %)

Potentially inappropriate medication at admission and at discharge

In total, 147 PIM were identified at admission, 107 (72.8%) were discontinued after the MMR, 40 (27.2%) were continued after MMR and 6 were introduced during hospitalisation (figure 3). In total, 46 PIM are continued on the discharge prescription, and in the end, 34 patients came out with at least one PIM. In our study, the PIM prevalence was 70.3% at admission compared to 33.7% at hospital discharge. There is a statistically significant difference between the average number of PIM per patient at admission and at the hospital discharge (1.46 PIM/patient at patient at admission against 0.46 at hospital discharge, p<0.01).

Figure 3: Flow chart of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) number during hospitalisation

(MMR: multidisciplinary medication review)

147 PIM identified

at admission

107 PIM stopped

after MMR

40 PIM

continued after

MMR

46 PIM at

discharge

6 PIM introduced during hospitalisation

Main therapeutic classes of PIM identified at admission and discharge are benzodiazepines (n=21 at admission, n=16 at discharge), Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) (n=20 at admission, n=6 at discharge) and neuroleptic drugs (n=14 at admission, n=8 at discharge). The most common types of PIM at admission are drugs without indication (n=46) and vasodilator drugs in patients with persistent postural hypotension (n=23) (cf annex 2).

Amongst the 46 PIM continued on the discharge prescription, 40 (87.0%) had finally a justified indication after analysis of the medical file: 20 drugs with a need for treatment after medical analysis and without safe alternatives, and 20 drugs with a need for treatment for the hospitalisation time but to reassess remote from hospitalisation by the GP (table III). The other drugs correspond to drugs with a questionable indication to be reassessed by the specialist doctor and/or by the GP (n=4: 3 statins and 1 antiplatelet agent), and drugs whose discontinuation has been forgotten (n=2: 1 benzodiazepine, 1 opioid without laxative treatment).

Main PIM continued and justified are benzodiazepines (BZD) (n=16) and neuroleptic drugs (n=8). Clinician’s reasons for continuing PIM prescriptions are listed on table IV.

Types of justification Continued PIM

number

% Need for treatment after medical file

analysis and without safe alternatives

20 43.5%

Need for treatment for the hospitalisation time but to reassess remote from

hospitalisation by the GP

20 43.5%

Drugs with a questionable indication, to be reassessed by the specialist doctor or by the GP

Table III: Clinician's reasons for continuing the potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) prescription (GP: general practitioner)

Types of PIM Number Reason for PIM continuation

Benzodiazepines

16

Anxiety/insomnia/restlessness, to reassess by general practitioner (n=14, 87.5%) Depressive syndrome/psychiatric disorder (n=2, 12.5%)

Neuroleptic drugs

8

Behavioral disorder/, restlessness, to reassess by general practitioner (n=4, 50%) Hallucinations (n=2, 25%)

Psychiatric disorder (n=2, 25%)

Any drug prescribed without an evidence-based clinical indication

*PPI

6

Probalistic treatment of ulcer when

explorations are not feasible (n=4, 66.7%) Prevention in case of combination of antiplatelet agent + high doses of corticoids (n=1, 16.7%)

Fragile patient at high risk of bleeding (n=1, 16,7%)

*Statins

4

Primary prevention in a diabetic patient, to reassess by general practitioner or

cardiologist (n=1, 25%): questionable indication

Carotid atheroma, to reassess by general practitioner or cardiologist (n=1, 25%): questionable indication

Sequelae of ischemia diagnosed on medical imaging in a diabetic patient (n=1, 25%) Aneurysm and carotid atheroma, to reassess by cardiologist (n=1, 25%): questionable indication

*Antiplate-let agent

2

Sequelae of ischemia diagnosed on medical imaging in a diabetic patient (n=1, 50%) Aneurysm and carotid atheroma, to reassess by cardiologist (n=1, 50%): questionable indication

Anticholinergic in patients with delirium, dementia, chronic prostatism or with a history of

narrow angle glaucoma 4

Uncontrolled Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) without adverse effect (n=3, 75%)

Acute dyspnea without adverse effect (n=1, 25%)

Table IV: Details of clinician's reasons for continuing the potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) prescription

PPI: proton pump inhibitor, BZD: benzodiazepine, Zdrugs (benzodiazepines-like drugs: zopiclone or zolpidem PRN: Pro Re Nata (as needed)

Potentially inappropriate medication prescription three months after the hospital discharge

Three months after the hospital discharge, we called GPs of 71 patients who had a PIM prescription at hospitalisation admission. During the study follow-up, 10 patients deceased and 5 were lost to follow. We recovered prescriptions for 56 of 71 patients and 25 GPs answered our questions (figure 4).

Any duplicate drug class prescription

2

Zdrug + BZD: zdrug just in case of insomnia (the patient doesn’t sleep without zdrug, test to take off in the unit without success) (n=1, 50%)

Clomipramine + amitriptyline: BZD stop in the unit, plan laroxyl withdrawal in the nursing home (n=1, 50%)

Tricyclic antidepressants with dementia, narrow angle glaucoma, cardiac conduction abnormalities, prostatism, or prior history of urinary retention

1

Patient treat with other therapeutic classes by past without results

Drugs likely to cause constipation

1 Should have been discontinue on the discharge prescription (forgotten)

Hypnotic Z-drugs 1 Insomnia, to reassessed by general

practitioner Use of regular (as distinct from

PRN) opioids without concomitant laxative

1

Forgotten

Total 46

Figure 4: Three months follow-up flow chart

(PIM: potentially inappropriate medications, GP: general practitioner)

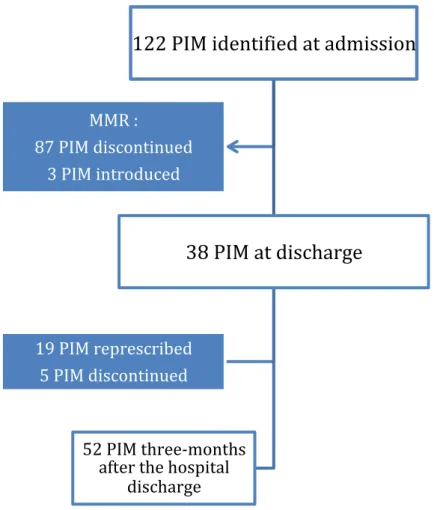

For the 56 patients finally followed-up, 122 PIM were prescribed at admission, 87 were discontinued after MMR and 3 were introduced, leaving 38 PIM at hospitalisation discharge (figure 5). The most common types of PIM at admission for these 56 patients were drugs without indication (n=37, 28 discontinued after MMR) and vasodilator drugs in patients with persistent postural hypotension (n=19, 19 discontinued after MMR). Three months after the hospital discharge we recorded 52 PIM (0.93 PIM/patient) against 122 PIM (2.18 PIM/patient) at the admission prescription (p<0.01). Between admission and three months after the hospital discharge it remains a 57.4% PIM decrease.

71 patients with at least 1 PIM at

home

56 patient's prescription were recovered

by community pharmacist

56 GP were called

GP of 25 patients

answered

31 GP of patients did not

answered

5 lost to follow-up + 10 deceased patients

Figure 5: Flow chart of the potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) number during

the care pathway for the 56 followed patients

(MMR: multidisciplinary medication review)

We noted also a statistically significant difference between the number of PIM per patient at discharge and three months after the hospital discharge (0.68 PIM/patient against 0.93; p<0.05). Some PIM are re-prescribed by GPs remote from hospitalisation. Amongst the 87 PIM discontinued after the MMR, 19 (21.8%) were re-prescribed by GPs. On 28 “without indication” PIM discontinued after MMR, only 5 were re-prescribed by GPs: 2 justified PPI (gastrointestinal bleeding from the rupture of oesophageal varices and gastrointestinal bleeding on radiation proctisis), 1 PPI

122 PIM identified at admission

38 PIM at discharge

52 PIM three-months after the hospital discharge 19 PIM represcribed 5 PIM discontinued MMR : 87 PIM discontinued 3 PIM introduced

discontinued after MMR, only 3 were re-prescribed three months after the discharge: 1 drug due to an increase of blood pressure, 1 tamsulosine cause of a patient complaint of “urinary discomfort” and 1 without justification transmitted by the GP. Benzodiazepines (n=3), Zdrugs (benzodiazepines-like drugs: zopiclone or zolpidem) (n=3), drugs without indication (3 PPI, 1 fenofibrate) and vasodilator drugs (n=3) are the main PIM re-prescribed by GP. The main GP’s reason for the PIM re-prescription is the need to treat the condition again. Nevertheless, we have not been able to collect justifications for several re-prescribed PIM (n=11, 57.9%). The list of GP’s reasons for PIM re-prescription is deferred in the table V.

Amongst the 38 PIM continued after MMR, 50% (n=19) had a justified indication for hospitalisation time but to reassess by GPs and only 15.8% (n=3 benzodiazepines) were discontinued by GPs at three months.

PIM number re-prescribed three months after the hospital discharge /

PIM number discontinued after

MMR

Reason for PIM re-prescription

Hypnotic Zdrugs 3/6 (50%) Unknown justifications (n=3) PPI without indication

or prescribed beyond the recommended

duration 3/13 (23%)

Gastrointestinal bleeding from the rupture of esophageal varices (n=1) Gastrointestinal bleeding on radiation proctisis (n=1)

Unknown justifications (n=1) Vasodilator drugs with

persistent postural hypotension

3/16 (19%)

Hypertension (n=1)

Unknown justification (n=1)

Tamsulosine re-prescribed for an urinary discomfort (n=1)

Fenofibrate without

indication 1/1 (100%)

Benzodiazepine 3/5 (60%) Unknown justifications (n=2) Anxiety + insomnia (n=1) Vitamin D (duplicate) 3/4(75%) Unknown justification (n=2)

Re-prescribed by the rheumatologist (n=1)

Thiazide diuretic

1/5 (20%) Hypertension and old hypercalcemia omitted (n=1) Neuroleptic drugs

1/6 (16,7) Unknown justification (n=1) Antiplatelet agent 1/6 (16.7%) Cerebrovascular accident (n=1) Other therapeutic

classes 0/25

/

Total 19/87 (21.8%)

Table V: General practitioners' reasons for potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) re-prescription

Discussion

Explicit criteria are helpful to detect PIM but they can not substituate a geriatric reassessement. To our knowledge, this is one of the rare study that analised the appropriateness of not discontinued PIM and the reasons why geriatricians decide not to follow STOPP criteria. This study shows that 87% of not discontinued PIM after a prescription review have an indication that justifes their continuation. The two main reasons for not discontinuing a PIM prescription are the need for treatment after medical file analysis without safe alternatives, and the need for treatment for the hospitalisation time but to reassess remote from hospitalisation by GPs. Moreover, this study suggests a positive impact of MMR on the PIM number during the care pathway of older patients. Indeed, 70% of identified PIM were discontinued after a MMR, and there is a statistically significant decrease of number of PIM per patient between hospital admission and discharge, and between hospital admission and three months after the hospital discharge.

This study highlights that 70% of identified PIM with the STOPP/START v2 list were discontinued (n=107 out of 153) after a MMR. Amongst the non-discontinued PIM, 87.0% had an indication that justified their continuation after analysis of the medical file. The main reason for not discontinuing a PIM prescription is the necessity to treat the patient without another safe alternative (n=20, 43.5%). This is the example of neuroleptic drugs in certain pathology, like advanced dementia with disturbing behaviour and chronic psychosis. This therapeutic class is considered as potentially inappropriate because it may cause gait dyspraxia, parkinsonism, increase the risk of urinary retention (for some of them), and

increase the risk of stroke according to STOPP criteria version 2 (14). However, for now there are no safe alternatives except a non-pharmacological approach. It can be also the case for PPI with the probabilistic treatment to treat ulcer for patients for whom explorations are not possible. This indication can be justified but we have considered it as PIM because this indication is not validated in the marketing authorisation. According to marketing authorization, PPI are indicated in the well-defined clinical conditions: treatment and prevention of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Zollinger-Ellison disease, H. pylori eradication, treatment of peptic ulcer, treatment of peptic ulcer disease, treatment and prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-associated gastroduodenal ulcer in patients with risk factors. However other indications can be justified according to scientific community: stress ulcer prophylaxis (in certain cases), ulcer prophylaxis in patients taking antiplatelet agent with risk factors (patients over 65 years old, gastroduodenal ulcer antecedent, and concomitant prescription of glucocorticoids and/or anti-coagulants) (40), iron deficiency anaemia with explorations not possible (41). Guidelines about gastro-oesophageal disease and gastrointestinal ulcer recommend a short length of treatment for most of the patients, respectively 4-8 weeks and 2-12 weeks. (42–45) At the end of treatment, PPI must be reassessed. A maintenance treatment is possible in case risks factors are still present. Concerning gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, treatment on request is feasible (44). Long-term treatment is not recommended. In the literature, many articles report adverse effect with PPI at long term like digestive infections, pneumonia, fracture, hypomagnesaemia (46–49)… Nevertheless, some adverse effects are controversial in the literature notably infectious diseases (50).

In Canada, guidelines have been developed to help clinicians make decisions about when and how to safely taper or discontinue proton pump inhibitors (44). The second main reason is the need for treatment during the hospitalisation time, but to be reassessed remote from hospitalisation by the GP (n=20, 43.5%). This justification can be explained by different reasons. One reason is that the hospitalisation stay is not an appropriate time to discontinue some drugs like benzodiazepines. According to STOPP criteria, benzodiazepines are potentially inappropriate because they can increase the risk of sedation, confusion, road traffic accidents and falls. In particular, there are no indications for benzodiazepines for more than 4 weeks. However, patients and notably elderly persons can be disoriented, anxious during hospitalisation because hospital is an unfamiliar place (51). Moreover, double room, noise, light, taking of vital signs and medication administration can disturb the patient’s sleep (52). Non pharmacologic approaches exist like music therapy (53), massages (54) (55) which can improve sleep but it needs nurse time. In this way, we can’t stop all benzodiazepines but we can provide during hospitalisation a decrease of benzodiazepine dosage until a minimal effective dosage and switch to a short half-life benzodiazepine. We have also suggested to GPs in the discharge letter to reassess these drugs remote from hospitalisation. For patients who need benzodiazepines only during the hospitalisation time, we were careful to discontinue them at the hospital discharge.

Another reason to not discontinue an identified PIM is due to a lack of information about medical history, and for which the drug indication is questionable according to the literature and the authorities’ recommendations. This is the case in our study for statins (n=3) and antiplatelet agents (n=1) prescribed for primary prevention in

diabetic patient or for carotid atheroma, for which there are few bibliographic data and no clear recommendations for elderly population (56–62). For these 4 PIM geriatricians did not discontinue the drug and request the cardiologist’s opinion in the letter discharge. We may wonder whether these drugs will really be re-evaluated. It may be interesting to directly include the patient's different health professionals in the prescription review during hospitalisation.

Lastly, reasons to not discontinue PIM in our study join those found in the few others studies. Indeed, in the Bahat’s study (20) geriatricians did not follow v2 STOPP criteria for 14.7% of identified PIM (19 PIM out of 129) against 27.2% in our study (40 PIM out of 147). Reasons for not accepting the STOPP suggestion in the Bahat’s study was the need for treatment despite the likelihood of anticipated side effects in 13 PIM, and need for treatment in the absence of anticipated side effects in 6 PIM. Likewise, therapeutic classes of continued PIM are also the same as in other studies and concerned in particular benzodiazepines and neuroleptic drugs (38,63).

The present study shows a relatively high prevalence of PIM prescriptions (70.3%) as compared to existing studies (22,64–69). Indeed, a literature review identified a prevalence of PIM between 21.4% to 79% (2013) (11). Authors notify that interpretation of this range should be made with caution due to the heterogeneity in both sample population and study design between the different studies. We can explain our high rate by the older age of our sample (87.4 average years of age), and the fact that we have used all criteria of the STOPP list for PIM identification,

prospective study inside of a medical unit, so we have had access to many data like biology and clinical exam. Therefore, we were able to work with the global STOPP list.

We observe that the number of PIM per patient decreases statistically significantly between admission and discharge (1.46 PIM/patient against 0.46; p<0.01). However, without group control we cannot conclude on the possible MMR impact. Some studies have tried to show that prescriptions review allows a PIM prescriptions decrease, an adverse effect decrease (11,16), nevertheless Cochrane reviews in 2018 about interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people conclude “it is unclear whether interventions to improve appropriate polypharmacy, such as reviews of patients’ prescriptions, resulted in clinically significant improvement » (70). This study reports a high risk of bias across a number of domains. PIM decrease might improve the quality of life or reduce economic cost according to some studies (11,71) (72). Studies in more detail, multicentric and controlled might be necessary to show a significantly clinical impact.

Multidisciplinarity, pharmaceutical presence in the unit and the transmission of PIM review reported to health professionals are the strenghts of the study. Communicate the PIM review report (through the drugs reconciliation table for community pharmacist and through the drugs reconciliation table present in the letter discharge for GPs) allows a better continuity of care. Indeed, according to the Charlotte Pichat’s thesis, 50% of drugs represcription remote from hospitalisation are the result of lack of communication (23). In the same idea, Singlard’s study show that 60% of drugs changes are continued if they are

explained in the letter discharge against 23.5% without explanations. However, results are not statistically significant (25). More recently, an intern study (data not yet published) have shown that drugs changes justification in the liaison letter (letter given to the patient at hospital discharge) allows a tendency to the drugs changes continuation three months after the hospital discharge, but results are not statistically significant. In our study, 21.8% of PIM discontinued during hospitalisation was re-prescribed three months after the hospital discharge. We observe that the PIM number per patient remains lower three months after discharge from hospital than at admission (2.18 PIM/patient against 0.93 PIM/patient; p<0.01,) but the PIM number per patient rises statistically significantly between the hospital discharge and three months after the hospital discharge (0.68 PIM/patient against 0.93 PIM/patient; p<0.05). The PIM re-prescription seemed justified by a need to treat again the patient, particularly for anxiety or hypertension. In this study, benzodiazepines (n=3), zdrugs (n=3), PPI (n=3) and vasodilator drugs (n=3) are the most re-prescribed therapeutic classes by GPs. Orthostatic hypotensive (OH) is frequent in the elderly all the more so in the case of polypharmacy (73–75). Reducing the number of drugs-induced OH can prevent falls but the vasodilators re-prescription in case of blood pressure increase is justified. Furthermore of 11 benzodiazepines and zdrug discontinued, 6 were re-prescribed. A re-prescription of benzodiazepines or zdrugs can be justified if the medical situation requires it. Some GPs in the study says that they hare under the families’ pressure to re-prescribe some drugs and notably benzodiazepines and zdrugs. Similarly, in literature we found that in residential care facilities pressure from the nursing staff to prescribe psychotropics seems to play an important role

By the way, only 15.8% of drugs that should have been reassessed by the GP as in the discharge letter are effectively discontinued by GPs (n=3 benzodiazepines). It is perhaps necessary to give more precise guidelines to GPs in the discharge letter about drugs deprescription. For example, some authorities recommend for benzodiazepines tapering the dose by 25% every 2 weeks; in elderly patients a longer tapering schedule over 4–5 months is generally preferred (77). The French Health Authority released a document about benzodiazepines withdrawal. This document advises a gradual stop on 4 to 10 weeks but no precise withdrawal protocol is suggested (78). Tannenbaum and al (79) show that patient’s education associated with a withdrawal protocol is efficient to discontinue benzodiazepines. This intervention consisted of an 8-page booklet about the risks of benzodiazepines use and including deprescription recommendations. The intervention asks patients to discuss the deprescribing recommendations with their physician and/or pharmacist. Educating patients is the most effective strategy to discontinue benzodiazepines according to several authors (76,79,80). Some studies on drugs deprescription also show a mortality decrease (37). In our study, we found a lower mortality post hospitalisation (14%, n=10 patients) compared to others studies (81,82).

This study has some limitations. First, it was performed in a single centre with a small sample size. A multicentric study would be useful to compare with different professionals practices. Secondly, the study was uncontrolled, so an impact of the MMR and the PIM justification cannot be demonstrated. A longer follow-up may also be necessary to show an impact of the PIM justification.

Conclusion

To conclude, 70% of identified PIM with the STOPP/START v2 list were discontinued after a MMR, and 87.0% of non-discontinued PIM had an indication that justified their continuation after analysis of the medical file. Neuroleptic drugs and benzodiazepines are the main PIM not discontinued after a MMR. The two main reasons for not discontinuing a PIM prescription is the need to treat the patient after analysis of the medical file, and the need to treat the patient during hospitalisation but indication to be reassessed remote from hospitalisation. In the end, STOPP criteria are a good tool, but explicit criteria must be necessarily associated to a geriatric assessment because some PIM can be justified according to patient’s medical situation. This study suggests that a PIM prescription decrease is possible after MMR, but studies with control group would be necessary to demonstrate a real impact. Likewise, the same is true for the potential impact of justification PIM in the letter discharge on the PIM re-prescription by GPs. To go further, it would be useful to carry out a feasibility study on a real structuring of this prescriptions re-evaluation in the care pathway, in order to define and organise communication between the different health professionals around the patient in a more standardised way.

Discussion

Cette étude est à notre connaissance l’une des rares à s’intéresser aux raisons pour lesquelles certains MPI ne sont pas arrêtés après une réévaluation pluridisciplinaire de leur prescription.

Cette étude met en lumière que 70% (n=107 sur 153) des MPI identifiés par la liste STOPP/START sont arrêtés suite à une réévaluation pluridisciplinaire, et 87% (n=40 sur 46) des MPI non arrêtés ont une indication qui justifie leur maintien après analyse du dossier médical. Les principaux MPI maintenus et justifiés sont les benzodiazépines, les neuroleptiques, et les inhibiteurs de la pompe à proton (IPP). Bien que potentiellement inappropriés, ces médicaments n’ont pas été arrêtés après une réévaluation de la prescription pour diverses raisons.

La raison principale est une nécessité de la prescription de ce médicament à la vue de la situation médicale du patient, car il n’existe pas d’alternative plus sûre, ou plus efficace. Ce cas de figure est principalement représenté par les neuroleptiques dans notre étude, mais également par les IPP. Les IPP sont une classe de médicament largement prescrite. En effet, d’après l’Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des produits de santé (ANSM) 16 millions de Français sont traités par IPP en 2015, dont 40% inutilement (83). Leur prescription est souvent banalisée et les durées de prescription sont peu respectées. Par conséquent, il est en général compliqué de trouver pour quelle indication cette classe thérapeutique est prescrite initialement, et la date d’introduction. Dans notre étude sur 46 médicaments sans indication à l’admission, 19 étaient des IPP (41.3%). Sur ces 19 IPP, 84.2% (n=16) ont été arrêtés suite à la réévaluation pluridisciplinaire. Les IPP maintenus l’étaient pour cause de traitement probabiliste