PIERRE-MARC BROUSSEAU

IMPACT DE LA DENSITÉ DE CERFS DE VIRGINIE

SUR LES COMMUNAUTÉS D'INSECTES DE L'ÎLE

D'ANTICOSTI

Mémoire présenté

à la Faculté des études supérieures de l’Université Laval dans le cadre du programme de maîtrise en biologie pour l’obtention du grade de maître ès sciences (M. Sc.)

DÉPARTEMENT DE BIOLOGIE FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES ET GÉNIE

UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL QUÉBEC

2011

Résumé

Les surabondances de cerfs peuvent nuire à la régénération forestière et modifier les communautés végétales et ainsi avoir un impact sur plusieurs groupes d'arthropodes. Dans cette étude, nous avons utilisé un dispositif répliqué avec trois densités contrôlées de cerfs de Virginie et une densité non contrôlée élevée sur l'île d'Anticosti. Nous y avons évalué l'impact des densités de cerfs sur les communautés de quatre groupes d'insectes représentant un gradient d'association avec les plantes, ainsi que sur les communautés d'arthropodes herbivores, pollinisateurs et prédateurs associées à trois espèces de plantes dont l'abondance varient avec la densité de cerfs. Les résultats montrent que les groupes d'arthropodes les plus directement associés aux plantes sont les plus affectés par le cerf. De plus, l'impact est plus fort si la plante à laquelle ils sont étroitement associés diminue en abondance avec la densité de cerfs. Les insectes ont également démontré une forte capacité de résilience.

Abstract

Deer overabundances can be detrimental to forest regeneration and can modify vegetal communities and consequently, have an indirect impact on many arthropod groups. In this study, we used a replicated exclosure system with three controlled white-tailed deer densities and an uncontrolled high deer density on Anticosti Island. The impact of deer density on the communities of four insect groups following a gradient of association with plants was studied alongside with the communities of herbivorous arthropods, pollinators and plant dwelling predators associated with three plant species whose abundance varies with deer density. The results revealed that arthropod groups more closely associated to plants were more strongly affected by deer density. Furthermore, the impact was stronger if the abundance of the plant to which they are closely associated decreased with deer density. Overall, insects appeared to be highly resilient to deer overabundance.

Avant-Propos

Ce mémoire comprend deux articles en anglais qui seront soumis pour publication dans une revue avec révision par les pairs. La récolte des donnés, l'identification des insectes, l'analyse des résultats et la rédaction de l'ensemble des textes du mémoire ont été faits par le candidat. Le directeur, Conrad Cloutier, le co-directeur Christian Hébert et le co-auteur Steeve Côté ont contribué aux manuscrits en corrigeant, révisant et en faisant des suggestions pour améliorer les textes. Cette recherche a pu être réalisée grâce à la participation conjointe de la Chaire de recherche industrielle CRSNG-Produits forestiers Anticosti de l'Université Laval et de Ressources Naturelles Canada.

Je voudrais en premier lieu remercier mon directeur et mon co-directeur de m'avoir permis d'entreprendre cette recherche et pour leur constant support et commentaires pour améliorer le travail effectué. Ils ont également su améliorer mon sens critique et mon esprit scientifique par leurs nombreux commentaires, souvent frustrants en premier, mais toujours pertinents et constructifs. J'apprécie également le fait d'avoir bénéficié d'un cadre de recherche favorable au développement personnel et un lieu de travail motivant dans le laboratoire de Christian Hébert au Centre de Foresterie des Laurentides.

Je remercie également les étudiants du laboratoire ÉcoDif avec qui il était toujours possible de parler de science ou d'autres sujets favorisant la décontraction aux moments opportuns: Ermias Azeria, Sébastien Bélanger, Richard Berthiaume, Jonathan Boucher, Éric Domaine, Jean-Philippe Légaré et Olivier Norvez. Je tiens également à remercier mes parents pour leur soutient tout au long de mes études.

J'aimerais également exprimer ma gratitude à l'équipe de la Chaire de recherche d'Anticosti, particulièrement Steeve Côté et Jean-Pierre Tremblay qui ont apporté leurs commentaires utiles à différentes étapes de la réalisation du projet, ainsi que Sonia de Bellefeuille et Caroline Hins qui ont géré le gros de la logistique de terrain.

Je souhaite également souligner la contribution de Yves Dubuc dans la préparation des travaux de terrain et son expertise au laboratoire et de George Pelletier pour son aide dans l'identification des insectes, tous deux de Ressources Naturelles Canada. Je remercie

également les étudiants qui m'ont aidé sur le terrain ou dans le laboratoire: Jannick Gingras, Nicolas Giasson et Yan Paiement. Finalement, je remercie Gaétan Daigle du département de mathématiques et de statistiques de l'Université Laval et Ermias Azeria pour leurs conseils pour les analyses statistiques.

Table des matières

Résumé ... i

Abstract ... ii

Avant-Propos ... iii

Table des matières ... v

Liste des tableaux ... vii

Liste des figures ... ix

Liste des annexes ... x

INTRODUCTION ... 1

Les surpopulations de cervidés ... 1

L'impact des populations surabondantes sur les écosystèmes ... 2

Effets sur les invertébrés ... 3

L'île d'Anticosti ... 6

Objectif de l'étude ... 7

SHORT-TERM EFFECTS OF REDUCING WHITE-TAILED DEER DENSITY ON INSECT COMMUNITIES IN A STRONGLY DISTURBED BOREAL FOREST ECOSYSTEM ... 9

Résumé ... 9

Introduction ... 9

Materials and methods ... 12

Study area ... 12 Experimental design ... 12 Vegetation data ... 13 Insect sampling ... 14 Statistical analyses ... 15 Results ... 17

Diversity and abundance ... 17

Community assemblages ... 18

Discussion ... 20

Acknowledgments ... 23

References Cited ... 24

INSECT-PLANT RELATIONSHIPS AT REDUCED DEER DENSITY IN AN OVERBROWSED BOREAL FOREST ECOSYSTEM ... 34

Résumé ... 34

Introduction ... 34

Materials and methods ... 37

Study site ... 37

Experimental design ... 37

Pollinators ... 38

Herbivores and predators ... 39

Statistical analyses ... 40

Pollinators ... 41

Herbivores and predators ... 42

Discussion ... 44

Acknowledgments ... 49

References Cited ... 49

CONCLUSION ... 62

Extinction et colonisation ... 62

Subsistance des espèces ... 64

Conservation ... 66

Liste des tableaux

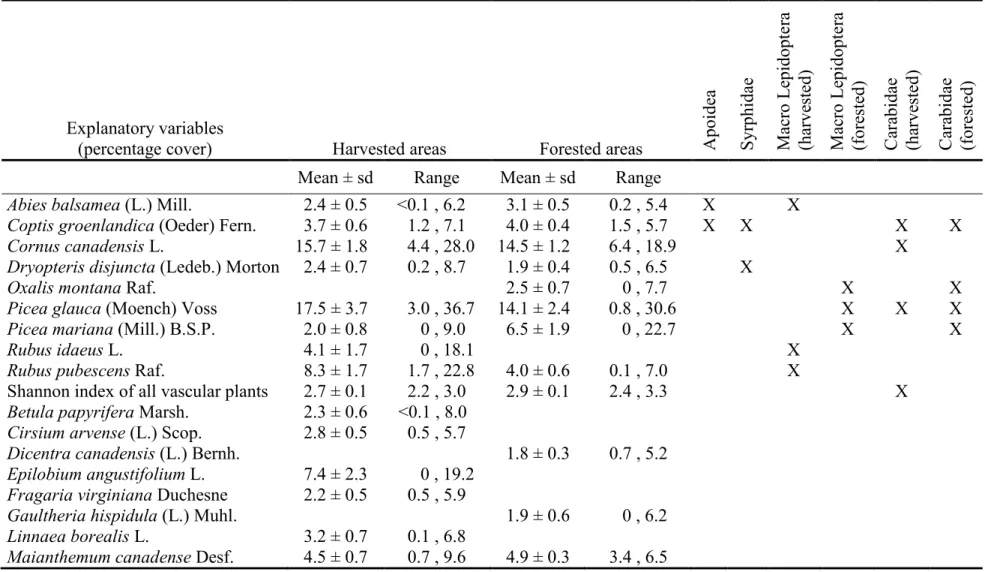

Table 1. Vegetation explanatory variables selected using the two-step forward

selection procedure and used in RDA analyses on insect communities of Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada), with their mean % cover and range for harvested and forested areas. Plant species unselected, but present in the original data pool are presented in the lower part of the table. ... 28

Table 2. Proportion of variance explained by the block effect based on mixed

ANOVA of type 3 on the abundance of the four major insect taxa in (H)arvested and (F)orested areas (df=2/6) of the white-tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Significant variances are bolded... 29

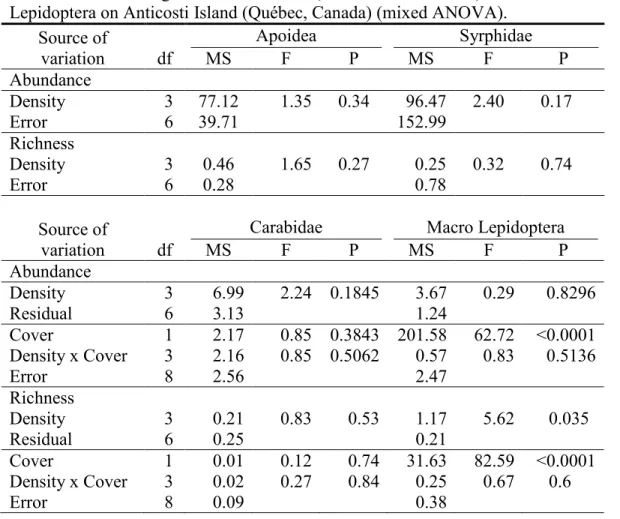

Table 3. Variation in the abundance and species richness of Apoidea, Syrphidae,

Carabidae and macro Lepidoptera in three blocks (random factor), four experimental white tailed deer densities and two vegetation cover areas (harvested or forested) for Carabidae and macro Lepidoptera on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada) (mixed ANOVA). ... 30

Table 4. Total species richness (S) and total abundance of Apoidea, Carabidae,

macro Lepidoptera and Syrphidae along an experimental deer density gradient (0, 7.5 and 15 deer/km2 and 'U'ncontrolled) in harvested and forested areas on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada), grouped based on relative abundance in uncontrolled deer density sites. Within each group and for each area, different letters indicate significant differences between deer densities based on mixed ANOVAs at α=0.05. ... 31

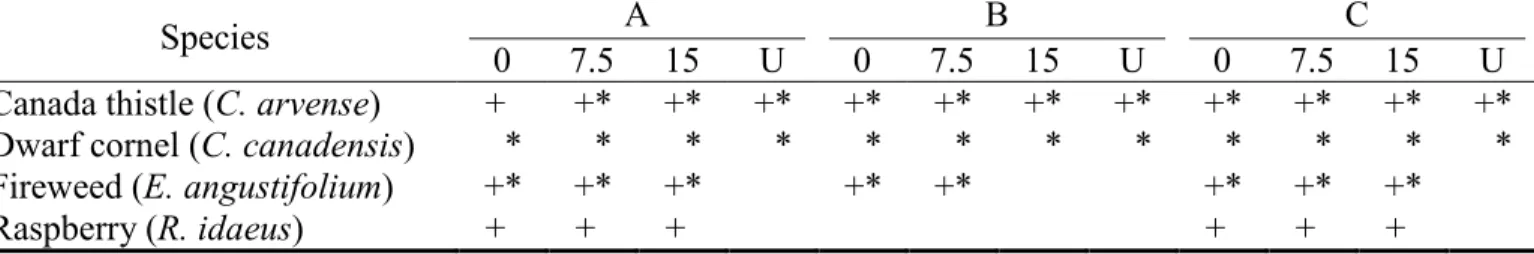

Table 5. Arthropod groups (*: pollinators; +: "herbivores and predators") studied vs.

plant species (Canada thistle, dwarf cornel, fireweed, and raspberry) in the different experimental units (0, 7.5, 15 deer/km2 and 'U'ncontrolled density) and blocks (A, B, C) of a deer-controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada)... 52

Table 6. Mixed ANOVA on abundance of the three dominant pollinators of the

flowers of three plant species on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada) as affected by deer density (four levels, fixed effect) and blocks (three blocks, random effect). ... 53

Table 7. Proportion of variance explained by the block effect based on type 3 mixed

ANOVAs on the abundance of dominant pollinators, grouped by family, on flowers of Canada thistle, dwarf cornel or fireweed in a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Significant block effect in bold. ... 54

Table 8. Mixed ANOVA on abundance of the four dominant herbivorous and

predator arthropods found on three plant species on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada), as affected by deer density (four levels, fixed effect), sampling period (n=2) and blocks (three blocks, random effect). ... 55

Table 9. Proportion of variance explained by the block effect based on type 3 mixed

ANOVAs on the abundance of dominant herbivores and predators, grouped by family, on Canada thistle, fireweed or raspberry in a white tailed deer controlled

browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Significant block effect in bold. ... 56

Liste des figures

Figure 1: Distance triplots (scaling 1) of redundancy analyses (RDA) on A) the

Apoidea species data (number of species (S)=35) and B) the Syrphidae (S=109) at all experimental sites (4 deer densities x 3 blocks) of a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Species are represented by a cross symbol (+) and a number for common species (see Annexe A). Arrows represent percent cover of each plant species retained as explanatory variables with the two-steps forward selection. ... 32

Figure 2: Distance triplots (scaling 1) of redundancy analyses (RDA) on the Macro

Lepidoptera species data in A) harvested area (number of species S=56) and B) forested area (S=90) at all experimental sites (4 deer densities x 3 blocks) of a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Species are represented by a cross symbol (+) and a number for common species (see Annexe A). Arrows represent percent cover of each plant species retained as explanatory variables with the two-steps forward selection. ... 33

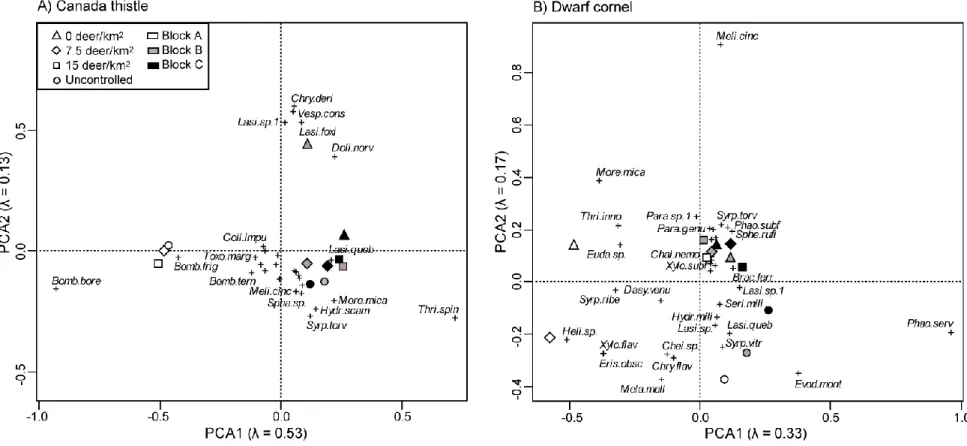

Figure 3: Distance biplots (scaling 1) of principal component analysis (PCA) on the

abundance of pollinators associated with A) Canada thistle and B) dwarf cornel in twelve experimental units (except that Canada thistle was not sampled in density 0 deer/km2 of block A) of a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Species are represented by (+) and the four first letters of the genus and species (See annexe B and C). ... 57

Figure 4: Distance biplots (scaling 1) of principal component analysis (PCA) on the

abundance of pollinators associated with fireweed in eight experimental units of a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Species are represented by (+) and the four first letters of the genus and species (see annexe D). ... 58

Figure 5: Distance biplots (scaling 1) of principal component analysis (PCA) on the

abundance A) of herbivorous and B) of predatory arthropods associated with Canada thistle in twelve experimental units of a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Species are represented by (+) and the four first letters of the genus and species (see annexe B). ... 59

Figure 6: Distance biplots (scaling 1) of principal component analysis (PCA) on the

abundance A) of herbivorous and B) of predatory arthropods associated with fireweed in eight experimental units of a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Species are represented by (+) and the four first letters of the genus and species (see annexe D). ... 60

Figure 7: Distance biplots (scaling 1) of principal component analysis (PCA) on the

abundance A) of herbivorous and B) of predatory arthropods associated with raspberry in six experimental units of a white tailed deer controlled browsing experiment on Anticosti Island (Québec, Canada). Species are represented by (+) and the four first letters of the genus and species (see annexe E). ... 61

Liste des annexes

Annexe A. Liste des espèces échantillonnés à l'aide de piège Luminoc® (Carabidae

et macro Lepidoptera) et Malaise (Apoidea et Syrphidae) et leur abondance cumulée dans un dispositif à broutement contrôlé du cerf de Virginie sur l'île d'Anticosti comprenant quatre densités de cerfs (0, 7.5, 15 cerfs/km2 et 'N'on contrôlée) et répété dans trois localités. ... 71

Annexe B. Liste des arthropodes (N>1) échantillonnés sur les plants ou les fleurs de

chardon (Cisium arvense) avec leur stade de développement à la capture, leur rôle trophique et leur abondance cumulée dans un dispositif de broutement contrôlé du cerf de Virginie sur l'île d'Anticosti comprenant quatre densités de cerfs (0, 7.5, 15 cerfs/km2 et 'N'on contrôlée) répété dans trois localités. ... 79

Annexe C. Liste des insectes pollinisateurs (N>1) échantillonnés sur les fleurs de

cornouiller du Canada (Cornus canadensis) avec leur abondance cumulée dans un dispositif de broutement contrôlé du cerf de Virginie sur l'île d'Anticosti comprenant quatre densités de cerfs (0, 7.5, 15 cerfs/km2 et 'N'on contrôlée) répété dans trois localités. ... 84

Annexe D. Liste des arthropodes (N>1) échantillonnés sur les plants ou les fleurs

d'épilobe (Epilobium angustifolium) avec leur stade de développement à la capture, leur rôle trophique et leur abondance cumulée dans un dispositif de broutement contrôlé du cerf de Virginie sur l'île d'Anticosti comprenant trois densités de cerfs (0, 7.5, et 15 cerfs/km2) répété dans trois localités. ... 86

Annexe E. Liste des arthropodes (N>1) échantillonnés sur les plants de framboisier

(Rubus idaeus) avec leur stade de développement à la capture, leur rôle trophique et leur abondance cumulée dans un dispositif de broutement contrôlé du cerf de Virginie sur l'île d'Anticosti comprenant trois densités de cerfs (0, 7.5, et 15 cerfs/km2) répété dans trois localités. ... 90

Introduction

Dans plusieurs écosystèmes de l'hémisphère nord, les cervidés ont un grand impact sur l'environnement et les communautés qui les entourent (Danell et al. 2006, Waller et Alverson 1997). En Amérique du Nord, l'augmentation de leurs populations et de leur aire de répartition au cours du dernier siècle a entraîné des changements écologiques importants dans différents écosystèmes suite à leur broutement excessif sur plusieurs plantes (McShea et al. 1997). Plusieurs études récentes ont d'ailleurs montré que les hautes densités de cervidés pouvaient nuire à la régénération forestière (Tremblay et al. 2007) et modifier les communautés de plantes (Rooney et Waller 2003), d'oiseaux (McShea et Rappole 2000), de petits mammifères (McShea 2000) et d'invertébrés (Stewart 2001).

Les surpopulations de cervidés

Selon Caughley (1981), une population animale atteint le niveau de surpopulation lorsqu'elle : 1) menace les populations humaines ou ses ressources, 2) cause une diminution de la densité d'un autre animal apprécié, 3) atteint une densité trop élevée pour son bien-être, 4) ou cause des perturbations dans l'écosystème où elle vit. Par contre, d'un point de vue strictement écologique, seule la quatrième définition correspond à de la surabondance selon Caughley. Les circonstances caractérisant les augmentations de population et pouvant mener à une irruption, i.e. une augmentation de population qui mène à la surpopulation, sont diverses et peuvent provenir d'une ou plusieurs causes agissant simultanément: l'augmentation de la capacité de support du milieu (K), la génération de nouveaux habitats par cause anthropique ou naturelle, et une diminution de la prédation ou de la chasse sont des facteurs souvent évoqués (Côté et al. 2004, McCullough 1997). L'isolement de certaines populations dans des secteurs précédemment exempts de cerfs, soit suite au franchissement d'une frontière naturelle ou suite à l'introduction par l'homme peut également entraîner des surpopulations (McCullough 1997).

Traditionnellement, on considère qu'une population connaissant une irruption voit sa densité augmenter jusqu'à un pic d'abondance pour ensuite subir un déclin rapide et se

stabiliser ultérieurement un peu en deçà de la capacité de support (K) du milieu (Caughley 1970); ce dernier aspect n'a par contre pas été démontré. Les populations de caribous (Rangifer tarandus L.) introduites sur les îles Saint-Paul (Scheffer 1951) et Saint-Mathieu (Klein 1968) en Alaska représentent des cas d'irruption suivi d'un déclin rapide. Dans le premier cas, 25 caribous ont été introduits en 1911 et le troupeau a atteint son pic de population en 1938 à 2046 individus. La population a ensuite chuté drastiquement à seulement 8 individus en 1950. Scheffer (1951) considère qu'à son pic d'abondance, la population de caribous était au moins trois fois plus élevée que la capacité de support du milieu, entraînant une réduction considérable de la quantité de lichens, nourriture hivernale de base du caribou, ce qui a causé sa chute. La situation sur l'île Saint-Mathieu est similaire, avec une diminution beaucoup plus rapide; le troupeau est passé de 6000 individus à 42 entre 1963 et 1966. Les causes de l'écroulement de la population seraient un hiver particulièrement rigoureux pendant lequel les individus affaiblis par la diminution de la quantité de nourriture disponible n'ont pu survivre (Klein 1968). L'évolution des populations suite à leur déclin n'est pas claire dû à un manque de suivi à long terme (>50 ans). À très long terme (~100 ans), il semble y avoir une oscillation stabilisatrice menant à l'équilibre de la densité des populations (Forsyth et Caley 2006). D'autres modèles prévoient plutôt une atteinte rapide de l'équilibre suite au déclin, ou un cycle de surabondance-déclin à amplitudes variables (McCullough 1997).

L'impact des populations surabondantes sur les écosystèmes

L'influence des cervidés sur leur habitat s'explique principalement par leur broutement sélectif de certaines plantes (Augustine et McNaughton 1998) permettant à celles évitées d'augmenter fortement en densité relative (Horsley et al. 2003). La sélectivité peut également opérer à fine échelle en évitant une plante acceptable se trouvant dans le voisinage d'une plante favorisée (Bee et al. 2009). Lorsque les jeunes arbres sont fortement broutés, cela peut nuire à la régénération forestière (Watson 1983) ou modifier à long terme la succession forestière. Par exemple, les surabondances de cerfs de Virginie ont transformé des érablières (Acer saccharum Marshall) en prucheraies (Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrière) au Michigan (Frelich et Lorimer 1985), et des forêts mixtes de feuillus en cerisaies (Prunus

également modifier les communautés de plantes de sous-bois en favorisant l'augmentation de l'abondance des fougères (Tilghman 1989) ou l'établissement d'une ou quelques espèces dominantes (Virtanen et al. 2002).

La nitrification du sol est également sujette à être modifiée par les cerfs. Dans les milieux riches en nutriments comme les prairies, l'impact peut être positif en favorisant la dégradation microbienne (Frank et al. 2000). Par contre, lorsque les plantes évitées par le cerf ont un taux peu élevé d'azote dans leur feuillage, comme l'épinette (Picea spp.), l'impact du surbroutement est négatif, nuisant ainsi au développement de certaines autres plantes (Pastor et al. 1993).

Ces modifications des communautés végétales entraînent des changements qui peuvent affecter les communautés animales de l'écosystème. La majorité des études sur l'impact des cervidés sur les oiseaux concluent que ce sont principalement ceux nichant dans les arbustes (ou la canopée intermédiaire) qui sont les plus affectés (deCalesta 1994, Martin et Daufresne 1996, Perrins et Overall 2001), soit ceux associés aux plantes ligneuses les plus accessibles aux cerfs. Également, Moser et Witmer (2000) ont observé une diminution de la richesse spécifique et de l'abondance de petits mammifères en présence de fortes densités de cerfs rouges (Cervus elaphe L.) et de vaches (Bos primigenius L.), expliquant la différence par une diminution de la quantité d'arbustes et de litière au sol.

Effets sur les invertébrés

Les cervidés peuvent également modifier les communautés d'invertébrés indirectement en éliminant la ou les plantes hôtes des herbivores; en modifiant la structure végétale; ou en diminuant la biomasse et la qualité de certaines plantes (résumés dans Stewart 2001). Les invertébrés les plus étudiés dans le contexte des surabondances de cervidés peuvent être séparés en trois groupes principaux: les arthropodes épigés, les prédateurs phytophiles et les herbivores. Ces groupes représentent un gradient de relation écologique avec les plantes. Le premier groupe, qui est relativement indépendant des plantes, est généralement composé des Carabidae et/ou des araignées du sol

(principalement les Linyphiidae). Les principaux travaux sur les Carabidae en milieu forestier (Melis et al. 2006, Melis et al. 2007, Suominen et al. 2003) et les Linyphiidae (tous milieux confondus) (Dennis et al. 2001, Gibson et al. 1992, Takada et al. 2008) révèlent que ces groupes sont généralement plus abondants et diversifiés dans les environnements subissant une pression de broutement élevée. La diminution du taux d'humidité et l'augmentation de la luminosité causées par une simplification de la structure végétale seraient les principaux facteurs responsables de cette augmentation (Melis et al. 2007). Par contre, sur les îles Haida Gwaii en Colombie-Britannique, Allombert et al. (2005) n'ont pas observé de différence dans l'abondance et la richesse des Carabidae sur les différentes îles en fonction de l'année d'introduction du cerf. Une alternative aux hypothèses des auteurs serait qu'un historique de colonisation différent par les Carabidae sur les îles entraînerait une forte variation entre celles-ci.

Les prédateurs phytophiles, représentés par les araignées à toiles, dépendent de la structure végétale et sont généralement négativement affectés par le surbroutement (Baines et al. 1994, Miyashita et al. 2004, Suominen et al. 2008, Takada et al. 2008). Le broutement des cervidés diminue le nombre de points d'attache disponibles pour les toiles, diminuant ainsi l'espace disponible pour les araignées. La seule exception notoire est le cas des Theridiidae, une famille d'araignées qui tissent leur toile à la base des plantes, mais qui se nourrissent principalement d'arthropodes épigés. Ces araignées utilisent principalement de grosses branches non affectées par le broutement pour construire leur toile, contrairement aux autres araignées à toiles qui utilisent souvent plusieurs sous-étages de végétation, ce qui explique probablement la différence de réaction.

L'impact des cervidés et autres ongulés est généralement négatif sur les invertébrés herbivores. Différentes études ont démontré une diminution de l'abondance des gastéropodes (Suominen 1999), des lépidoptères (Baines et al. 1994, Kruess et Tscharntke 2002), des hétéroptères (Morris et Lakhani 1979) et des coléoptères, hyménoptères et diptères herbivores (Baines et al. 1994). Pour les gastéropodes, la diminution du taux d'humidité est le principal facteur responsable de la diminution de leur abondance

(Suominen 1999), alors que pour les autres groupes et particulièrement les spécialistes, c'est probablement la diminution de la biomasse de leurs plantes hôtes.

Quelques rares études se sont également penchées sur l'influence des cervidés sur les relations insectes-plantes. Vázquez et Simberloff (2004) ont étudié la pollinisation de plantes des Andes dans des milieux broutés par des cervidés et du bétail. Pour les quatre espèces de plantes répondant au broutement, aucune différence significative du nombre de visites de pollinisateurs n'a été observée entre les sites broutés et non broutés. Par contre, dans une étude précédente, les mêmes auteurs avaient trouvé des différences dans les communautés de pollinisateurs de sites broutés vs. non broutés (Vázquez et Simberloff 2003). Les principales différences s'expliquaient par un changement dans la fréquence de quelques relations dominantes; i.e. que les espèces pollinisatrices fortement associées à une plante lorsque celle-ci est abondante seraient moins associées à celle-ci lorsqu'elle devient rare. Den Herder et al. (2004) ont étudié l'impact du broutement du caribou sur le saule (Salix phylicifolia L.) et les insectes herbivores qui y sont associés. Les résultats montrent une diminution de 50% de la longueur des branches de saule dans les sites broutés et une diminution dans l'abondance des principaux herbivores: les chrysomèles du genre

Gonioctena et les mouches-à-scie galligènes des genres Eupontania, Euura et Phyllocolpa.

Finalement, dans une étude sur le broutement hivernal de l'orignal (Alces alces (L.)) sur le bouleau argenté (Betula pendula Roth), l'abondance des pucerons (Aphididae) était plus élevée sur les arbres broutés que sur les non broutés, alors qu'aucune différence significative n'a été observée pour les Curculionidae, lépidoptères et Eriophyidae (acariens) (Den Herder et al. 2009). Les résultats de ces deux études peuvent sembler contradictoires, mais ils démontrent que différents groupes d'insectes réagissent différemment aux stress subi par les plantes. Ainsi, les pucerons profitent d'une diminution de production des composés secondaires de défense de la plante en situation de stress, alors que les chrysomèles et les mouches-à-scie sont défavorisées par une diminution de la productivité de la plante causée par une diminution du taux de photosynthèse (Larsson 1989).

L'île d'Anticosti

L'île d'Anticosti a une superficie de 7943 km2 et est située dans le Golfe du Saint-Laurent à ~35 km de la côte continentale nord et à ~72 km de la côte sud. Sa forêt fait partie de la zone boréale et est principalement composée de sapin baumier (Abies balsamea (L.) Mill.), et d'épinette blanche (Picea glauca (Moench) Voss) et noire (Picea mariana (Mill.) BSP). Le climat est de type maritime avec des étés frais et des hivers plutôt doux. Port-Menier, avec une population de 275 habitants, est le seul village de l'île. En 1896, 220 cerfs de Virginie ont été introduits sur l'île d'Anticosti dans le but d'en faire la chasse. Aucun prédateur naturel n'étant présent sur l'île, la population a rapidement augmenté pour atteindre aujourd'hui un total estimé de 125 000 individus sur l'ensemble du territoire; soit >20 cerfs/km2 (Potvin et Breton 2005).

Plusieurs espèces décidues telles que l'érable à épis (Acer spicatum Lam.), le noisetier à long bec (Corylus cornuta Marsh.) et le cornouiller stolonifère (Cornus

stolonifera L.) ont pratiquement disparu de l'île. En hiver, le sapin représente 72% du

régime alimentaire du cerf (Lefort 2002), nuisant ainsi à la régénération des sapinières. Les peuplements forestiers établis avant 1930 sont composés à 77-84% de sapin baumier, alors que les peuplements plus récents sont composés à 92-99% d'épinette blanche (Potvin et al. 2003). De plus, la proportion des peuplements dominés par le sapin est passée de 40% à 20% en 100 ans (Potvin et al. 2003). D'autres espèces de plantes autrefois abondantes sont également devenues rares, telles que l'épilobe (Epilobium angustifolium L.), le framboisier (Rubus idaeus L.) et la clintonie boréale (Clintonia borealis (Aiton) Raf.) (Potvin et al. 2003) au profit de plantes telle que le chardon (Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.) (Viera 2004). Finalement, les sapinières matures de l'île d'Anticosti diffèrent de celles des îles de Mingan, un archipel sans cerf au nord d'Anticosti dont le climat et l'écologie sont semblables, par une faible représentation des semis de sapin (10-30 cm de hauteur) et l'absence d'arbustes (Viera 2004).

Après 8,5 ans d’exclusion du broutement du cerf à l’aide d’exclos dans des milieux récemment coupés, aucune différence n’a été observée dans la richesse spécifique des plantes comparativement aux endroits non protégés (Casabon et Pothier 2008). Par contre,

sept espèces de plantes (dont le bouleau blanc (Betula papyrifera Marsh.), l'épilobe et le sapin baumier) étaient significativement plus abondantes dans les exclos et deux l'étaient dont les zones broutées à l'extérieur des exclos (le chardon et les violettes (Viola sp.)). Finalement, en étudiant le retour des plantes à différentes densités de cerfs (0, 7,5, 15 cerfs/km2 et densité non contrôlée) dans des sapinières matures et des milieux de coupe, Tremblay et al. (2006) ont trouvé une augmentation exponentielle de la productivité de plusieurs espèces de plantes en fonction de la réduction de la densité de cerf à partir de 15 cerfs/km2.

Objectif de l'étude

L'objectif général de l'étude est de déterminer l'impact de la réduction des densités de cerfs sur l'île d'Anticosti sur les communautés d'insectes en comparant trois densités de cerfs (0, 7,5 et 15 cerfs/km2) contrôlées à l'aide d'exclos avec des sites à densité non contrôlée de cerfs (>20 cerfs/km2). Ce projet entre dans le contexte d'une étude plus vaste visant à caractériser les patrons de régénération de la végétation et l'impact sur les animaux (oiseaux, petits mammifères et insectes) suite à la réduction des densités de cerfs. Un des objectifs clés est de déterminer la capacité de restauration des écosystèmes de l'île lorsque la densité de cerfs est réduite. Dans un premier temps, l'impact est étudié de façon générale sur les communautés de quatre groupes d'insectes appartenant à des guildes écologiques différentes: Carabidae (prédateurs épigés), Apoidea (pollinisateurs nicheurs), Syrphidae (pollinisateurs non-nicheurs dont les larves sont prédatrices ou saprophages) et Lepidoptera (herbivores). Dans cette section, l'hypothèse principale est que les modifications observées dans les communautés végétales suite à la réduction des densités de cerfs entraîneront des modifications dans les communautés d'insectes. Cette hypothèse permet de prédire que les taxons les plus fortement associés aux plantes (ex: phytophages) devraient réagir de façon plus prononcés que ceux qui n'y sont pas associés (ex: prédateur épigés).

En deuxième lieu, l'influence de la densité de cerfs sur les relations insectes-plantes est étudiée. Les pollinisateurs, les herbivores et les prédateurs phytophiles de quatre espèces de plantes ayant un patron de réaction différent à la réduction de la densité de cerfs sont étudiées: le chardon, le cornouiller du Canada (Cornus canadensis L.), l'épilobe et le

framboisier. Deux hypothèses (ce sont des prédictions) sont formulées pour ce chapitre. Premièrement, tout comme pour le premier chapitre, les insectes les plus spécifiques aux plantes devraient être les plus affectés par les diminutions de densité de cerfs. Deuxièmement, les arthropodes associés aux plantes affectées négativement par la diminution de la densité de cerf devraient être plus fortement affectés que ceux associés aux plantes absentes ou très rares à densité non contrôlée de cerfs. Celles-ci devraient principalement être utilisées par des espèces généralistes peu ou pas influencées par la densité de cerfs.

Short-term effects of reducing white-tailed deer density

on insect communities in a strongly disturbed boreal

forest ecosystem

Résumé

Le broutement sélectif des cerfs peut nuire à la régénération forestière et modifier les communautés végétales. Plusieurs études ont démontré qu'il en résultait des impacts indirects sur plusieurs groupes d'arthropodes, mais ces résultats sont fragmentaires et limités à des taxons particuliers. Dans cette étude, nous avons étudié l'impact des densités de cerfs de Virginie sur les communautés de quatre groupes d'insectes suivant un gradient d'association avec les plantes sur l'île d'Anticosti. Un dispositif répliqué dans trois localités avec trois densités contrôlées de cerfs et une densité non contrôlée et élevée a été utilisé. Les résultats montrent que les taxons d'insectes les plus affectés par les densités de cerfs sont ceux dont les liens sont les plus étroits avec les plantes. L'abondance des espèces rares de Lépidoptères (herbivores) augmente et leurs communautés sont fortement affectées lorsque la densité de cerfs est diminuée, alors que les Carabidae (prédateurs épigés) ne sont pas affectés.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the populations of cervids have been increasing in many parts of the world, mainly because of reductions in predators and hunting pressure, as well as increasing forage availability (reviewed in Côté et al. 2004). The overabundance of cervids has important ecological consequences as preferential and selective overbrowsing can be detrimental to forest regeneration (Watson 1983, Côté et al. 2004) and can modify plant communities (Rooney and Waller 2003, Côté et al. 2004). Also, the direct effect of high cervid density on vegetation is known to indirectly impact populations of invertebrates (Stewart 2001), birds (McShea and Rappole 2000), small

mammals (McShea 2000), and even large omnivores such as black bear (Ursus americanus Pallas) (Côté 2005).

Large herbivores can indirectly affect invertebrates by removing their host plants or by reducing plant biomass or quality, as well as by simplifying vegetation structure (reviewed in Stewart 2001). Studies involving different herbivorous insect taxa have generally shown that they were negatively affected by high ungulate density (Gibson et al. 1992b, Baines et al. 1994, Kruess and Tscharntke 2002, Martin et al. 2010), while studies on predators, which are usually less closely linked to plants, yielded variable responses. For instance, web-spiders, which highly depend on vegetation architecture (Baines et al. 1994, Miyashita et al. 2004), have been shown to be negatively affected by high ungulate density while small epigeal spiders such as Linyphiidae were favoured (Gibson et al. 1992a, Dennis et al. 2001, Takada et al. 2008). The Theridiidae, which construct webs at the base of plants, but mostly feed on ground-dwelling arthropods, seem not affected nor favoured by ungulate density (Takada et al. 2008). Most studies in forested areas have shown that Carabidae were more abundant at high grazing intensity (Suominen et al. 2003, Melis et al. 2006, Melis et al. 2007), but in at least one case, they were not affected at all (Allombert et al. 2005). However, in moorlands, a more open ecosystem, Gardner et al. (1997) reported that Carabidae were negatively affected by high cervid density. Nevertheless, Gardner et al. (1997) and Melis et al. (2007) reached the same conclusion for carabid assemblages: species associated with shady and moist habitats were more abundant at low grazing pressure, while the opposite was true for species associated with open habitats.

Some trends can be drawn from these studies based on the degree of association of organisms with plants. However, few studies have considered multiple guilds with different levels of relationship with plants in assessing the impact of high ungulate density on arthropods (but see Allombert et al. 2005). Furthermore, some groups such as pollinators which are less closely linked to plants than herbivores (flowers are available for a limited period during the life of pollinators while herbivores feed on plants during most of their life) have never been studied except in a context of observing their activity on flowers (Vázquez and Simberloff 2003, 2004).

An important difficulty arising when one wants to compare different studies is that ungulate densities are usually unknown. Therefore, because the comparison is often simply made between severely browsed and unbrowsed sites, moderate level disturbance has rarely been studied. The intermediate-disturbance hypothesis suggests that species diversity should be higher at intermediate level of disturbance (Connell 1978). Plants (Côté et al. 2004), birds (deCalesta 1994), and Carabidae and Curculionidae (Suominen et al. 2003) have been shown to be more diverse and/or abundant at intermediate deer density, which is compatible with this hypothesis. However, the results for Carabidae and Curculionidae were based on the abundance of lichen (Cladina spp.) carpets in dry forests of Lapland and are thus hardly generalizable to other systems where ungulate overbrowse saplings, shrubs and herbaceous plants.

Our goal was to evaluate the short-term effects on insect communities of reducing density of overabundant white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann)) in strongly disturbed balsam fir forests of Anticosti Island, Quebec, Canada in forested and harvested areas. We hypothesized that the short-term response of insects to reduced deer browsing pressure should follow their level of dependence on plants. Thus, we expected that insect responses should decrease from herbivores to pollinators and finally to epigeal predators. As it has been shown for vegetation (Tremblay et al. 2006), we hypothesized that insect responses should be stronger in harvested areas than in forested areas. From another viewpoint, dominant species of arthropods found in environments that are disturbed by overbrowsing are those that obviously have been the most favoured by conditions generated by high ungulate density. Thus, we may hypothesize that these dominant species should be the first to be negatively affected by reductions of deer density.

We predicted that 1) sensitivity to deer density should be stronger for herbivores and decrease along the guild gradient representing the degree of association with plants; 2) the species most rapidly affected should be those that dominate the disturbed ecosystem; 3) short-term responses should be stronger in harvested areas than in forested areas.

Materials and methods

Study area

Study sites were located on Anticosti Island (7943 km2) in the Gulf of St-Lawrence (49º30'N 63º00'W), Quebec, Canada. The North coast of the island is ~35 km from the mainland compared to ~72 km for the South coast. White-tailed deer were introduced on Anticosti Island between 1896 and 1900. In absence of predators, the deer population increased rapidly and its density is now estimated at >20 deer/km2 across the island (Potvin and Breton 2005). The forest of Anticosti Island belongs to the boreal zone and is mostly composed of balsam fir (Abies balsamea (L.) Miller), white spruce (Picea glauca (Moench) Voss) and black spruce (Picea mariana (Miller) Britton, Sterns & Poggenburg). The dynamics of Anticosti forest ecosystems is strongly disturbed by deer overabundance. Old-growth forests originating prior to deer introduction are mostly dominated by balsam fir while recent forests are almost entirely dominated by white spruce because of browsing selectivity on balsam fir and deciduous trees (Potvin et al. 2003). The proportion of balsam fir dominated stands across the landscape has decreased from 40% to 20% over the last 100 years and many plant species once abundant are now rare, such as fireweed (Epilobium

angustifolium L.), raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) and yellow clintonia (Clintonia borealis

(Aiton) Rafinesque-Schmaltz) (Potvin et al. 2003).

Experimental design

A deer exclosure system where deer density was controlled was established in 2001 (Tremblay et al. 2006). The experiment formed a factorial design, where deer density was controlled at 0, 7.5 and 15 deer/km2 in fenced exclosures in three replicated blocks (A, B and C) located in different parts of the island. Each block also included an additional experimental unit with the local uncontrolled deer density (>20 deer/km2).

To control deer density in experimental units, all deer were removed from a 10 ha exclosure (0 deer/km2), whereas three deer (>11 months old) were stocked in exclosures of 40 ha (7.5 deer/km2) and 20 ha (15 deer/km2), for the other controlled densities. Deer used

in the controlled densities were captured in early spring, released within exclosures, and euthanized in late fall. Deer were equipped with VHF radio transmitters with mortality and activity sensors (Lotek Wireless, Newmarket, ON) to ascertain a constant deer density during the summer treatment period.

In each experimental unit (four densities x three blocks), ~70% of the forest was harvested just before the onset of the experiment in 2001, leaving ~30% of the mature balsam fir forest. The deer browsing treatment has been applied each year since 2002. In the residual forested areas, most of the vegetation biomass was represented by mature trees that were almost unaffected by the reduction of deer density, thus the main changes were on herbaceous plants density, such as dwarf cornel (Cornus canadensis L.) (Tremblay et al. 2006). However, in harvested areas, pioneering species such as fireweed and Rubus spp. rapidly established. Uncontrolled deer density in each block was estimated using line transect surveys of summer fecal pellet clusters using a distance sampling protocol (Buckland et al. 2001) and computed with DISTANCE 5.0 software (Thomas et al. 2010). For details about the estimation protocol, see Tremblay et al. (2006). Through years, uncontrolled deer densities were estimated at 26 deer/km2 for block B, and 57 deer/km2 for blocks A and C.

Vegetation data

Vegetation was inventoried during summer 2007 in 20 plots of 10x10 m randomly distributed in both the harvested and forested areas of each experimental unit. The percentage cover of shrubs was visually evaluated by several observers using consensus calibration in each 10x10 m plot, while that of other vascular plant species was estimated in each of two randomly selected quadrats of 1x1 m inside the larger plot; for trees, only seedlings were considered. The technique was similar to that used by Tremblay et al. (2006). The mean percentage cover of each species across all quadrats of each experimental unit was used for the analyses.

Insect sampling

Four taxonomic groups belonging to different ecological guilds along a gradient of association with plants were sampled. Nocturnal macro Lepidoptera (i.e. Bombycoidea, Drepanoidea, Geometroidea, Noctuoidea) representing mostly herbivorous insects as caterpillars; Apoidea (excluding former Sphecoidea) (Hymenoptera) representing the most important insect pollinator specialists, and are also nesting insects; Syrphidae (Diptera) were selected because they are both pollinators (polliniphage) when adults, while presenting diverse feeding behaviours at the larval stage such as predators, saprophages, herbivores or inquilines with ants, bees or wasps (Foote 1991). The absence of nesting behaviour also makes Syrphidae less affected by landscape structure (such as forest fragmentation) than Apoidea (Jauker et al. 2009). Finally, Carabidae were selected because they represent a broad diversity of mostly epigeal predators, often considered as useful bioindicators (Rainio and Niemelä 2003). These four taxa represent a gradient relative to their degree of association with plants: Carabidae (no direct relationship) → Syrphidae → Apoidea → macro Lepidoptera (close relationship with plants, and numerous cases of mono- and oligophagy).

Luminoc® traps (BIOCOM, Quebec City, QC.) (Jobin and Coulombe 1992) equipped with a blue light tube of 1.8 watt were used as pitfall traps to sample Carabidae (Hébert et al. 2000). In each experimental unit, two pitfall traps were installed in both harvested and forested areas. Traps were placed at least 100 m away from exclosure fences and whenever possible (i.e. when the forest patch was large enough), at least 50 m from the forest edge. Traps were operated during five 9-11 day periods between June and mid-August 2007, using 40% ethyl alcohol as a preservative and for a total of 50 trapping days/trap in each experimental unit. At the end of each pitfall trapping period, the Luminoc® traps were raised and placed on a post at 3 m above the ground to sample macro Lepidoptera for 3-4 day periods. Vapona® strips were used to kill Lepidoptera in traps rather than ethyl alcohol. Traps at 3 m were operated when three consecutive non rainy days were forecasted by Environment Canada between 25 June and 19 August, for a total of 18 trapping days/trap in each experimental unit.

Flying adult Apoidea and Syrphidae were sampled using one Malaise trap (Gressitt and Gressitt 1962) in each experimental unit, installed in the harvested area, 50 m away from the forest edge and at least 100 m away from the exclosure fence. These traps were operated between 15 June and 19 August 2007, for a total of 64 trapping days/trap. A solution of 40% ethyl alcohol was used as preservative and samples were collected at intervals of ~14 days.

All specimens were identified at the species level whenever possible except for a few genera: i.e. Andrena (Apoidea: Andrenidae), Cheilosia and Microdon (Syrphidae),

Eupithecia (Lepidoptera: Geometridae), and most females of Heringia, Platycheirus and Sphaerophoria (Syrphidae). Furthermore, specimens of the subgenus Lasioglossum

(Dialictus) (Apoidea: Halictidae) were identified as morphospecies due to the lack of accurate identification keys and reference collection. Specimen identifications were cross-checked at the Canadian National Collection (CNC) of insects, arachnids and nematodes in Ottawa, Canada, and at the Insectarium René-Martineau (IRM) of the Canadian Forest Service in Québec, Canada, for families for which there was no expert at the CNC.

Statistical analyses

For each major taxon (macro Lepidoptera, Apoidea, Syrphidae and Carabidae), we used mixed model ANOVAs (PROC mixed) (SAS 9.1, SAS Institute 2003) to examine variation in species richness (R) and the overall abundance of each major taxon in relation to deer density. Deer density was considered a fixed effect, and blocks a random effect. For macro Lepidoptera and Carabidae, a split-plot model with cover (forested or harvested) included as subplot was used. To meet the assumptions of ANOVA (i.e.: normality, homogeneity of variances), abundance and species richness data were square-root transformed. Furthermore, for the abundance of each major taxon, the relative contribution of blocks to the total variance among experimental units was calculated as follow:

where σ2B is the estimated variance of the block effect and σ2ε is the estimated variance of

residuals. This is also a measure of the intraclass correlation related to blocks (Fleiss et al. 2003).

To test the hypothesis that dominant species should be more affected than other groups by decreases in deer density, we classified all species of each major taxon in four groups based on their ordered total abundance in uncontrolled deer densities. For Carabidae and macro Lepidoptera, this was done for both harvested and forested areas. A dominant species was defined as a species representing at least 25% of the total abundance of the taxon; common species were those that composed the first 75% of the total abundance, but were not dominant; uncommon species were present in the interval between 75-95%; and rare species were the remaining 5%. A mixed ANOVA was used to compare the abundance of each group between deer densities using the model previously described.

Variations in community composition were examined using redundancy analysis (RDA) based on Hellinger transformed species data (Legendre and Gallagher 2001). The RDAs were performed with the software R (function rda of the library vegan, version 1.15-4) (Oksanen et al. 2009). They were conducted for each major taxon and also separately for harvested and forested areas for macro Lepidoptera and Carabidae. All RDAs included the twelve experimental units (four deer densities x three blocks), all insect species identified in the taxon and a number of explanatory variables selected using the two-steps forward selection procedure described by Blanchet et al. (2008), using the function forward.sel of library packfor in R (Dray et al. 2007), with α=0.1. Explanatory variables included deer density, % cover of each common plant species (i.e., representing ≥5% of total cover in at least one experimental unit) and the Shannon-Weiner index estimated for all vascular plants and for each of the five major plant groups (deciduous trees, coniferous trees, shrubs, herbaceous plants, and graminoids). Apoidea and Syrphidae were analysed using only vegetation data collected in harvested areas whereas data collected in forested or harvested areas were used for macro Lepidoptera and Carabidae in function of the area analysed. Shannon-Weiner indices for plants were calculated on the basis of the percentage ground cover of each species. Non-normal variables (based on the Shapiro test) were square-root or

fourth-root transformed; if it was not enough, they were removed from the analysis. Multicollinearity among explanation variables was assessed by calculating tolerance value (Quinn and Keough 2002); if tolerance was < 0.2 for one or more variables, the one with the lower score was removed from the pool, and the forward selection was run again until a result > 0.2 was obtained for all variables. The list of retained explanation variables for each RDA is available in Table 1.

RDA results were interpreted using distance triplots (scaling 1) where the eigenvectors are scaled to unit length (Legendre and Legendre 1998). In this scaling, projecting at right angle an experimental unit along an explanatory variable or a species response approximates the position of the unit along that variable (i.e. their degree of relation). In addition, the angle between an explanatory variable and a species represents their correlation. Finally, the distance between experimental units approximates their Euclidean distance in multidimensional space (Legendre and Legendre 1998).

Results

Diversity and abundance

A total of 1308 specimens of Apoidea representing 35 species belonging to five families (Andrenidae, Apidae, Colletidae, Halictidae and Megachilidae) were identified. For Syrphidae, 7481 specimens belonging to 109 species were caught while captures of macro Lepidoptera totalled 260 specimens in the harvested areas and 1343 in the forested areas. There were five macro Lepidoptera families (Arctiidae, Drepanidae, Geometridae, Lymantriidae and Noctuidae) and 105 species: 56 in the harvested areas and 90 in the forested areas. Finally, 1878 Carabidae belonging to 30 species were caught; 875 in the harvested areas and 1003 in the forested areas.

Although significant ANOVAs were obtained for most taxa, the effect of the block was high, explaining from 18.2% to 95.8% of the variance in the abundance of the four major insect taxa (Table 2). The block effect was not significant for Syrphidae while the

strongest effect was observed for Carabidae in forested areas. For both macro Lepidoptera and Carabidae, a significant block effect was found in both harvested and forested areas (Table 2).

Mixed ANOVAs did not reveal any significant effect of deer density on total abundance of any major taxa (Table 3). However, the effect of deer density was significant on the number of species of macro Lepidoptera (Table 3) for which, more species were captured at density 7.5 deer/km2 and 15 deer/km2 than in uncontrolled densities. The abundance of the dominant species of Syrphidae (Melanostoma mellinum (L.)), and Carabidae (Synuchus impunctatus (Say)), in both harvested and forested areas, decreased at reduced deer densities (Table 4). No dominant species was identified in forested areas for macro Lepidoptera, while the dominant species of harvested areas, the noctuid Leucania

multilinea Walker, did not vary significantly with deer density as for the dominant species

of Apoidea, Bombus borealis Kirby (Table 4). However, the dominant species of Apoidea declined in all reduced deer density sites by 25-79% while Bombus frigidus Smith became the dominant species in these sites. The abundance of rare species of macro Lepidoptera was significantly higher at reduced deer densities than in uncontrolled densities in both harvested and forested areas (Table 4).

Community assemblages

Community analyses realised with RDAs showed markedly different responses of the four studied insect taxa. For Apoidea (Fig. 1A), experimental units of block A have negative values on axis 1 while those of blocks B and C are on the positive side, confirming the previously mentioned substantial block effect on insect abundance (Table 2). Furthermore, on the second axis, uncontrolled deer densities have positive values along with densities 0 and 15 deer/km2 of block B. Also, for reduced deer densities, the block effect was less strong than for uncontrolled densities. Balsam fir cover highly contributed to the formation of the second axis, and was thus mostly associated with reduced deer densities, while gold-thread (Coptis groenlandica (Oeder) Fernald) strongly contributed to the formation of the first axis, and was associated with blocks B and C.

Uncontrolled deer densities of the three blocks clearly shared a similar syrphid community, which was also shared with the 15 deer/km2 density of block B. The dominant species (M. mellinum) and one uncommon species (Platycheirus angustatus (Zetterstedt)) were strongly associated with this group of experimental units. Experimental units with reduced deer densities had different trajectories; those of block A were grouped together in the 2nd quadrant of the triplot and far from those of blocks B and C that were located in the 3rd and 4th quadrants, mostly along the 2nd axis. Contrary to Apoidea, the block effect appears to be greater for reduced densities than for uncontrolled densities, as shown by a greater separation of sites at reduced densities on the second axis. Gold-thread again opposed sites of blocks B and C to those of block A. Oak fern (Dryopteris disjuncta (Ledeb.) Morton)) was associated with high deer densities on the first axis.

For macro Lepidoptera, different RDAs were conducted for each area (harvested and forested). In harvested areas, the three uncontrolled deer density sites had negative values on axis 1 along with the 15 deer/km2 density of block B, while other experimental units had positive values (Fig. 2A). Balsam fir and dwarf red blackberry (Rubus pubescens Raf.) were associated with reduced deer densities on axis 1. Furthermore, the second axis mostly separated block A from blocks B and C. Like for Syrphidae, sites with reduced deer densities tended to differ more between themselves than uncontrolled densities. Raspberry highly contributed to separate block A from blocks B and C. In forested areas, community patterns were not as clear as in harvested areas (Fig. 2B). However, sites of block A, except that with 0 deer/km2, had negative values on the second axis along with uncontrolled density of block B, which was far from other densities of this block. Also, black spruce separated blocks B and C from block A.

Finally, for Carabidae, no significant RDA could be obtained either for the harvested or the forested areas.

Discussion

As predicted, our results showed that the sensitivity of different insect taxa and feeding guilds to deer density decreased along a gradient representing their degree of association with plants. Epigeal Carabidae, who do not have any direct relation with plants, did not vary with deer density. For Syrphidae and Apoidea, we found a separation of the community between uncontrolled and reduced densities, but this separation was not as clear as for the Lepidoptera, which is the group most intimately linked to vegetation. Moreover, macro Lepidoptera was the only taxon with significantly higher abundance of rare species and higher number of species overall at reduced than at uncontrolled deer densities. In addition to the degree of association with plants, trophic level was also likely important. Indeed, predators may be slower to colonize new habitats than herbivorous species (Brown and Southwood 1983) as they depend on the recovery of herbivorous insects. Syrphidae and macro Lepidoptera also showed more differences in their communities between sites at reduced deer density than between sites at uncontrolled densities. This suggests that high deer density tends to homogenize the habitat, which results in decreased diversity of ecological niches available to insects, which are obviously closely linked with plant communities. It is also known that insect communities are composed of different species according to the plant composition (Schaffers et al. 2008), so that higher insect diversity can be expected in presence of higher diversity of ecological niches.

Because our study sites were located far from the shore and Anticosti Island itself is located at least 35 km away from the continent, we assume that most of the insects found in our study were present on the island before the 2001 forest harvesting. This implies, on one hand, that the most common species must be those that were adapted to conditions generated by deer overabundance, and were already abundant locally, and thus, were available to colonize the new habitats. On the other hand, rare species are more likely to be those inhabiting restricted areas on the island, such that their colonizing potential depends on the distance between the source populations and the new habitats (Littlewood et al. 2009). The abundance of the dominant species of Carabidae and Syrphidae significantly decreased at reduced deer densities. In Apoidea, the dominant species was nearly absent from blocks B and C and so, no significant effect of deer density was obtained. However, in

block A, its abundance decreased by at least 60% at two reduced densities, and by 25% in the third one. In macro Lepidoptera, no dominant species was identified in forested areas and no effect was observable on the dominant species in harvested areas. However, the abundance of rare species in this taxon was higher at reduced deer density sites. The results for all taxa except macro Lepidoptera are thus in agreement with the prediction that dominant species should be more rapidly affected by deer density reduction than other species. However, the response of rare species of macro Lepidoptera was faster than expected originally, which suggest a higher colonization capacity of this taxon.

For macro Lepidoptera, RDAs revealed that communities were more strongly structured in the harvested than in forested areas. This agrees with our hypothesis that changes are faster in an ecosystem fully exposed to sunlight, which allows rapid establishment and growth of colonizing plants. However, the abundance of rare species was higher at reduced densities than in uncontrolled densities in both harvested and forested areas. This suggests that moth communities can rapidly benefit from new vegetation growth in both open and forested areas. In temperate deciduous forests, it has been shown that rare Lepidoptera species were mostly associated with understory vegetation (Hirao et al. 2009) which could explain why only rare species seem to be affected in forested areas. Alternatively, it could also suggest that Lepidoptera in our relatively small residual forest patches benefit from the fast regeneration of the surrounding harvested areas.

The absence of response for Carabidae is intriguing because they generally show positive interactions with large herbivore density (Suominen et al. 2003, Melis et al. 2006, Melis et al. 2007). In our study, no effect was detected at the community level (RDA analysis). Similar results were also reported by Allombert et al. (2005) who worked on introduced black-tailed deer (Odocoileus columbianus (Richardson)) in the Haida Gwaii archipelago in British Colombia (Canada). Flying incapacity of many species of this family combined to random dispersion of flying species (Brouwers and Newton 2009) and landscape heterogeneity of our study sites (Halme and Niemelä 1993) can result in stochastic colonization. This is supported by the concentration of several species in only one or two experimental units, such as Calathus advena (LeConte) which was mostly

caught (66 out of 67 specimens) in the 7.5 deer/km2 of block A; Pterostichus melanarius (Illiger) with 57 out of 62 captures in the uncontrolled density of block A; Amara aulica (Panzer) with 26 out of 32 captures in the uncontrolled density of block A and density 7.5 deer/km2 of block B; and Pterostichus pensylvanicus LeConte with 11 out of 15 captures in density 0 deer/km2 of block C. Based on this, the absence of carabid response to deer browsing in Allombert et al. (2005) could alternatively be explained by stochastic colonisation of islands, and this could suggest that using insects with limited mobility could lead to misinterpretation when studying the impact of ecological changes on islands.

We hypothesized that insect diversity should follow the intermediate-disturbance hypothesis (Connell, 1978) and thus, be richer at mid deer densities (7.5 and 15 deer/km2). Our results are not conclusive on this aspect. For all taxa except Carabidae, the number of species was indeed higher at mid densities. However, this is significant only for macro Lepidoptera compared with uncontrolled density sites, but not with those of 0 deer/km2. Thus, this hypothesis is not confirmed on a short term in the system studied, but our results permit to hypothesize that it might be true in the long term, at least for insects closely associated with plants.

Our results support the suggestion of Hébert and Jobin (2001) that regeneration of balsam fir forests and of pioneering plant species such as raspberry are important in maintaining insect communities on Anticosti Island. These plants, once very abundant on the island are now endangered by deer overabundance and only a marked decrease of deer density could permit their restoration (Tremblay et al. 2006, 2007). Insect communities of the 15 deer/km2 of block B were different than those of other sites with the same deer densities and were more similar to uncontrolled densities for unknown reasons. A possible explanation is the presence of high level of regeneration of white spruce in this site, resulting from a hemlock looper (Lambdina fiscellaria (Guenée)) outbreak in early 1970's that may have reduced sunlight penetration and adversely affected herbaceous plant regeneration. Whatever, this indicates that deer reduction to 15 deer/km2 can be sufficient to restore insect diversity, but is unlikely to be efficient in all situations. Unfortunately, unlike plants, no historical data are available for insects of Anticosti island before deer

overbrowsing became noticeable in the mid 20th century (Potvin et al. 2003), and thus it is difficult to determine how reducing deer density can actually help to restore original insect natural communities.

Some very rare insect species of northeastern North-America have previously been found on Anticosti Island including Neospondylis upiformis (Mannerheim) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) (Hébert, unpublished data) and Papilio brevicauda Saunders (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) (Handfield 1999), and others were found in this study: Harpalus

megacephalus LeConte, Pipiza macrofemoralis Curran (first mention in the Province of

Quebec), and Xylota flavitibia Bigot (first mention in eastern Canada). Considering that many insect taxa have yet to be investigated on this large island, additional rare species are expected. These are relevant arguments in favour of the long-term maintenance of the natural forests of Anticosti Island. In this context, it is important to continue studying the impact of deer on forest regeneration of Anticosti Island, but also elsewhere in North America and Europe where deer overabundance is also an issue (Côté et al. 2004). As shown here in relation to deer density, the insect fauna is directly and indirectly influenced by the surrounding vegetation, and limiting the impact of deer overabundance on plant communities is also important to maintain entomodiversity. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that the impact of deer density on insect communities can be expected based on their degree of association with plants. Also, our results show that even in highly perturbed environment, restoration of plant communities can rapidly benefit insects and particularly herbivorous insects with high dispersal ability.

Acknowledgments

Our research was financed by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Produits forestiers Anticosti Inc. (PFA), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) and Université Laval. We would like to thank M. Poulin, S. Pellerin and M. Bachand for vegetation data; N. Giasson for help in field work, and Y. Paiement for help in laboratory work. We also thank Y. Dubuc for technical assistance and G. Pelletier for his taxonomic expertise, both of NRCan, and S. de Bellefeuille from the NSERC-Produits forestiers Anticosti Industrial Research Chair for logistical assistance. We are