SANDRA HOPPS ¿¿A

///9/

THE EFFICACY OF COGNITIVE-BEHAVIOURAL GROUP THERAPY

FOR LONELINESS VIA INTER-RELAY-CHAT AMONG PEOPLE

WITH PHYSICAL DISABILITIES

Thesis Presented to the

Faculté des Études Supérieures de !’Université Laval

for obtention of a Philosophiae Doctor (Ph D.)

École de Psychologie

FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES SOCIALES UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL

QUEBEC

Dépôt final December 2002

ABSTRACT (Short)

This study examines the efficacy of psychotherapeutic services via computer-mediated communication (CMC). Its main purpose is to determine if goal-oriented cognitive- behavioural group teletherapy via IRC can reduce feelings of loneliness among

chronically lonely people with physical disabilities. Using a comparison design with pre- test, post-test, follow-up and waiting-list control, 19 participants formed seven groups of 2-3 people. Participants completed an in-person individual assessment during which individualized therapeutic goals were enumerated. They also attended twelve 2-hour group intervention sessions via inter-relay-chat (IRC). Results indicate that participants felt less lonely after intervention. Moreover, participants who completed intervention felt less lonely at post-test than a similar group that had been placed in a waiting-list control. Furthermore, results indicate that gains were maintained at a 4-month follow-up. The results of this study are discussed, along with participants’ comments about the

intervention, its practical implications and some special considerations for teletherapy, as well as future directions for research.

Sandra Lynn Hopps Student

Michel Pépin, Ph.D. Research Director

Loneliness and Teltherapy iii ABSTRACT (Long)

Tele-health is becoming an integral aspect of health service delivery. Although most psychologists have already used the telephone to provide clinical services, they have only just recently begun to explore the possibilities of computer-mediated therapy. Those who offer this type of service often emphasise the possibility of providing specialized services to populations that might not be able to or that are unwilling to obtain them due to geographical, economic or physical restrictions. However, empirical investigation of its efficacy is, at the time of this writing, absent from the literature, which has only provided anecdotal and case study evidence of its effectiveness. Despite this lack of empirical data, the number of people offering counselling or psychotherapy via inter-relay-chat (IRC) is ever increasing.

This thesis is divided into two parts. The first concerns a review of the literature and theoretical background concerning loneliness, loneliness interventions, the social participation of people with physical disabilities, and computer-mediated communication (CMC).

The second part presents a study examining the efficacy of providing cognitive- behavioural group goal-oriented teletherapy via IRC to lonely people with physical disabilities. Its main purpose is to determine whether this form of psychotherapy can reduce participants’ feelings of loneliness, as assessed by the UCLA Loneliness Scale and Likert-type ratings. Using a comparison experimental design with pre-test, post-test, three-month follow-up and waiting-list control group, 19 chronically lonely people with physical disabilities formed seven groups of 2-3 persons. Each participant completed an in-person individualized assessment during which individualized therapeutic goals were enumerated. They also attended twelve 2-hour group intervention sessions via IRC. Results of this study indicate that participants felt less lonely after having received intervention. At the 4-month follow-up, these gains had been maintained. Moreover, participants who completed intervention felt less lonely at post-test than a similar group that had been placed in a waiting-list control group. Furthermore, one group was selected

for case-study purposes in order to illustrate the intervention and examine its clinical impact. The results of this study are discussed. As well, participants’ comments about the intervention are presented along with special considerations for providing teletherapy based on these comments and the investigator’s experience. Finally, some interesting directions for future research are identified.

Sandra Lynn Hopps Student

Michel Pépin, Ph.D. Research Director

Loneliness and Teltherapy v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Completing this research project and writing this thesis was greatly facilitated through the assistance of several people. It was because these people provided me with emotional support, tolerance of my moods and energy levels, advice, favours and distraction that I was able to maintain my sanity throughout this process and bring this thesis to term.

My parents, John and Pat Hopps, for their continual support and faith in me throughout my life and my studies. As well, it should be pointed out that it was they who offered me a certain vacation gift during which I had the "flash" for my project. More specifically, I would like to thank my father for transmitting his interest in computers and new technologies. He also forewarned me of the place that computers would take within society when Commodore 64s were the only affordable home computers. I did not turn out to be a computer programmer like he once suggested, but I was listening to his constant insistence that computers “are the future”. I'd also like to thank him for

declaring his faith in me out loud. My mother, on the other hand, I owe my quick typing skills, assiduity, and understanding of the importance of friends and community. These skills and qualities are those that brought this project to term within a reasonable delay and that also largely inspired the core content of this thesis. I also would like to thank her for discretely showing her pride in me lest I neglect to continue working hard to make her proud. I'd also like to thank other members of my family, including Cari, Shannon, Donnie, David, Dean, Stacey, Alyssa and all others (not in order of importance) for continuing to be there when I was so far away.

Another special thanks to David Middleton who graciously read my thesis and offered corrections and suggestions. I have been told that he consulted his dictionary frequently in attempts to understand my Frenglish. I know he was busy, but he still found the time.

I'd also like to thank the certain professors. For Dr. Michel Pépin, my thesis supervisor, I would like to thank him for giving me the lee-way needed to carry out such a novel experiment, as well as his confidence, encouragement and availability. To Dr. Jean-Marie Boisvert, I thank him for initiating me to Laval University and for his moral support when I was fatigued. I'd also like to thank him for his valuable clinical

suggestions. Dr Michel Loranger, who kept on reminding me that my work is good and that there is an end to this seemingly endless track.

The people who participated in this project should not be forgotten. It was they who truly made it possible. They also were responsible for encouraging me to continue by ensuring me that my efforts (and theirs) were rewarding for them as well.

Although there were several people that inhabited the thirteenth floor of Pavilion Savard that I would like to thank, there are some that I would like to thank more

particularly. Marie-Claude Blais, thank you for the cheer you brought to the lab. The days went by quicker when she was there. Besides being a great friend to me through her kindness, emotional support, and willingness to accompany me in my sources of

distraction, she also provided me with insight, observations, criticism and advice

concerning my project and thesis. She also managed to motivate me to develop a regular working schedule. Other people in the lab did these same things as well. Geneviève Kirouac, Katia Sirois, and Dominique Lemay were friends, mentors, and colleagues to me. Thank you Marquis Falardeau for you computer knowledge and assistance.

Another special thank you is for Nicole on the 11th floor. Her smile and cheery disposition could brighten the gloomiest of moods.

I'd like to thank other friends, such as my roommates who tolerated my bad moods. Shannon Hill, for introducing me to inter-relay-chat. Esther Fleury, for introducing me to the lonely reducing (or increasing?) qualities of inter-relay-chat. Sandra Ella Pedersen who, when thought about, inspired me. There are others who

Loneliness and Teltherapy vii provided me with long-distance support, such as Cassie Andrews who came to visit me when the writing was getting burdensome.

Another special thank you goes to Alain Bematchez, the man I love. He had to endure my fatigue, my stress, my late nights, my bad moods, my temper, and my rumblings about things that only I could understand. It was he who made me dinner when I was tired, reassured me that I had a life outside of room 1112, and who convinced me that two months away from work would be good thing (and it was).

There remain a few more thankyous. My previous French professors for teaching me the language. Webspirs, who enormously facilitated the literature review process. And finally, the Conseil Québécois de la Recherche Sociale for their financial support.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SHORT ABSTRACT ii

LONG ABSTRACT iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V

TABLE OF CONTENTS viii

LIST OF TABLES xiii

LIST OF FIGURES XV

LIST OF ANNEXES xvi

INTRODUCTION xix

PART ONE: THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

INTRODUCTION TO THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL BACKGROUND 1

CHAPTER 1

1. LONELINESS: EMPIRICAL AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 3

1.1. WHO IS LONELY. DRAWING THE PORTRAIT OF THE LONELY

PERSON 3

1.2. LONELINESS: THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 5

1.2.1. The cognitive approach to loneliness 7

1.3. CAUSES, MAINTAINING FACTORS, AND EFFECTS OF LONELINESS.

A VICIOUS CIRCLE 10

1.3.1. Cultural and environmental context, and current social network 13

1.3.2. Cognitions and attitudes 16

1.3.3. Interpersonal behaviour 18

1.3.4. Affect, mood, and suicide 21

1.3.5. Self-esteem 24

1.3.6. Personality and characteristics of the person 24

1.3.7. Social and loneliness coping strategies 25

1.3.8. Developmental experiences and social learning history 27

Loneliness and Teltherapy ix 30 49 31 33 36 38 42 43 CHAPTER 2

2. COGNITIVE-BEHAVIOURAL ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF LONELINESS

2.1. COGNITIVE-BEHAVIOURAL ASSESSMENT OF LONELINESS 2.1.1. Rook and Peplau (1982)

2.1.2. Gambrill (1995) 2.2. TREATING LONELINESS

2.2.1. Young’s cognitive-behavioural treatment for loneliness (1982) 2.2.2. Rodway's group therapy for loneliness (1992)

2.2.3. Strategies to help a person establish emotional ties

CHAPTER 3

3. DISABILITY AND SOCIAL PARTICIPATION 51

3.1. BARRIERS TO SOCIAL PARTICIPATION 52

3.2. OVERCOMING ATT1TUDINAL BARRIERS TO SOCIAL

PARTICIPATION 57

3.3. ARE PEOPLE WITH PHYSICAL DISABILITIES LONELIER? 58 3.4. TREATING LONELINESS AMONG PEOPLE WITH PHYSICAL

DISABILITIES 59

3.5. COUNSELLING PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES 64

CHAPTER 4

4. COMPUTER-MEDIATED COMMUNICATION AND TELETHERAPY 67

4.1. COMPUTER-MEDIATED COMMUNICATION, LONELINESS AND

RELATIONSHIPS 68

4.2. COMPUTERS AND NETWORKS IN MENTAL HEALTH 73

4.3. TELEHEALTH 74

4.3.1. Computer-mediated mental health services 76

4.4. DILEMMAS IN DELIVERING ONLINE MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES 81 4.4.1. Sampson et al.'s (1997) areas of ethical concern 81

4.4.2. Other dilemmas in computer-mediated mental health delivery

services 83

4.4.3. National Board for Certified Counselor's Code of Ethics for the

Practice Of WebCounseling (Bloom, 1998) 85

4.4.4. Research on text-based computer-mediated therapy 87

PART TWO: RESEARCH PROJECT: THE EFFICACY OF GOAL-ORIENTED COGNITIVE-BEHAVIOURAL TELE-THERAPY FOR LONELINESS VIA IRC

AMONG PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

91 INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCH PROJECT

98 98 98 99 99 99 101 101 104 105 106 107 109 109 109 110 CHAPTER 5 5. METHOD 5.1. PROTOCOL 5.2. RECRUITMENT

5.2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria 5.3. PARTICIPANTS

5.4. VARIABLES ASSESSED 5.5. INSTRUMENTS

5.5.1. University of California in Las Angeles Loneliness Scale 5.5.2. Emotional versus Social Loneliness

5.5.3. Personal definition of loneliness 5.5.4. Acceptance of Disability Scale

5.5.5. Questionnaire sur les difficultés reliées à la limitation physique 5.6. EQUIPMENT, MATERIAL AND OTHER RESOURCES

5.6.1. Inter-relay-chat 5.6.2. Technical assistance

5.6.3. Le développement d’habiletés sociales chez les personnes ayant une incapacité physique: Manuel du participant

Loneliness and Teltherapy xi

5.6.4. Social skills training manual test 110

5.6.5. Description of interactions self-observation form 111

5.6.6. Personal definition booklet 111

5.6.7. Personal inventory 112

THERAPY 113

5.7.1. Therapy and assessment 113

5.7.2. Group intervention procedure 114

5.7.3. Therapist 115 PROCEDURE 115 5.8.1. First phone-call 116 5.8.2. Information session 116 5.8.3. Group assignment 117 5.8.4. Pre-test 117 5.8.5. IRC training 118 5.8.6. Therapy 119

5.8.7. Post-test and comments 121

5.8.8. Follow-up 122 124 124 124 125 126 127 128 128 129 131 131 CHAPTER 6 6. RESULTS 6.1. PRELIMINARY INFORMATION 6.1.1. Special data about recruitment

6.1.2. Information about absences and the drop-out 6.1.3. Data screening and treatment

6.1.4. Terminology concerning the times of measurement 6.2. PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

6.2.1. Group differences on demographic variables 6.2.2. Descriptive statistics

6.3. BETWEEN AND WITHIN GROUP COMPARISONS 6.3.1. Pre-test scores between treatment and control groups

6.3.2. Post-treatment improvement 132

6.3.3. Total sample 132

6.4. CLINICALLY SIGNIFICANT CHANGE 134

138 138 145 145 146 147 147 152 CHAPTER 7 7. DISCUSSION 7.1. FINDINGS

7.2. CLIENT COMMENTS ABOUT THE INTERVENTION

7.2.1. Positive comments about IRC as a medium for intervention 7.2.2. Negative comments about IRC as a medium for intervention 7.2.3. Therapy

7.4. PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THIS STUDY 7.5. FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

155 REFERENCES

Loneliness and Teltherapy xiii LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

1. Causal attributions for loneliness. 17

2. Behaviours associated with a friendly attitude. 45

3. What is beautiful is good. 53

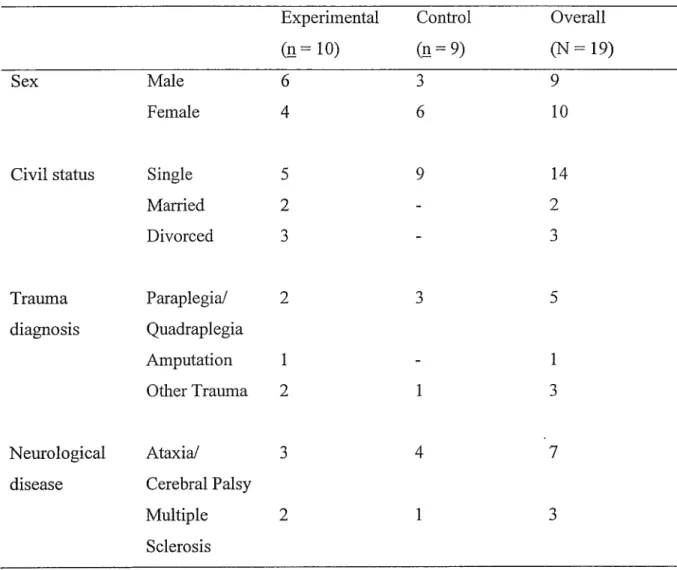

4. Sources of attitudes towards people with disabilities. 54 5. Frequency distribution of gender, civil status and diagnoses for experimental

group, control group, and overall (N - 19). 100

6. Overall and group means and standard deviations for age, educational level

and income (N- 19). 101

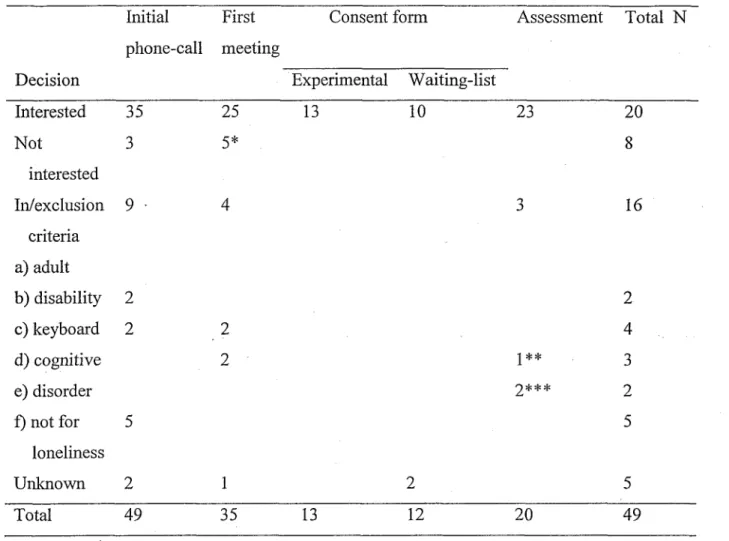

7. Frequency distributions of decisions to participate or not after initial phone-call, first meeting, consent form signing, and assessment,

according to reason. 126

8. Identification of measurement terms within time. 128

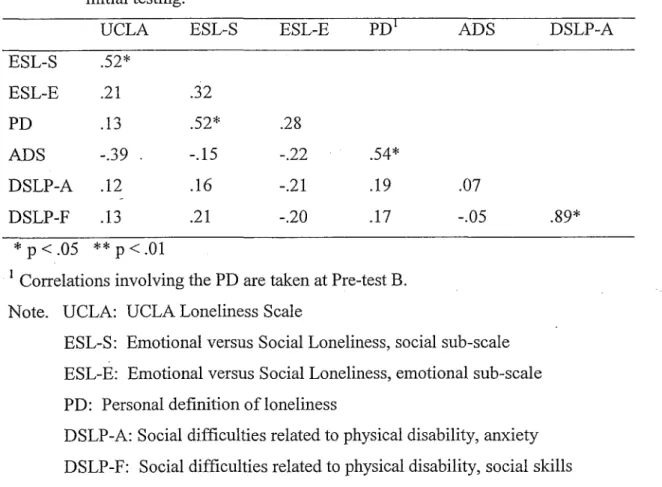

9. Correlations between the measures of loneliness, acceptance of disability, as well as anxiety and social skills in social situations involving disability

at initial testing (N = 19). 129

10. Group and overall means and standard deviations for measures of

loneliness at pre-test A, pre-test B, post-test and follow-up. 130 11. Group and overall means and standard deviations for the

Acceptance of Disability Scale, and Questionnaire on social difficulties

related too physical disability. 131

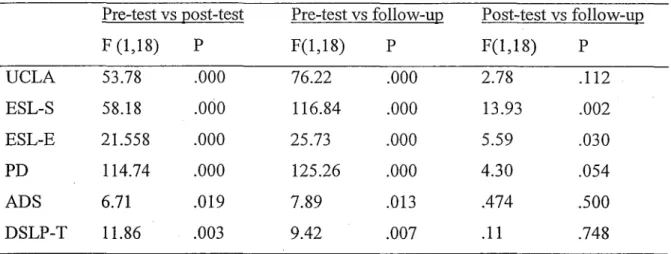

12. Repeated measures ANOVAs between pre-test, post-test, and follow-up. 133 13. Frequency distributions of treatment responses for both groups at Time

2 and for the overall sample at post-test. 135

14. Number of participants who meet high end state functioning criteria

at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up (N - 19). 136

15. Jack's scores on questionnaires at pre-test, as well as means and standard

LIST OF TABLES (cont.)

16. Jack's scores on questionnaires at pre-test, post-test and follow-up, as well as means and standard deviations of questionnaires based

on normalization data. 187

17. Tom's scores on questionnaires at pre-test, as well as means and

standard deviations of questionnaires based on normalization data. 194 18. Tom's scores on questionnaires at pre-test, post-test and follow-up, as

well as means and standard deviations of questionnaires based

on normalization data. 200

19. Mary's scores on questionnaires at pre-test, as well as means and

standard deviations of questionnaires based on normalization data. 205 20. Mary's scores on questionnaires at pre-test, post-test and follow-up, as

well as means and standard deviations of questionnaires based

Loneliness and Teltherapy xv LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Pase

1. Loneliness: A vicious circle 27

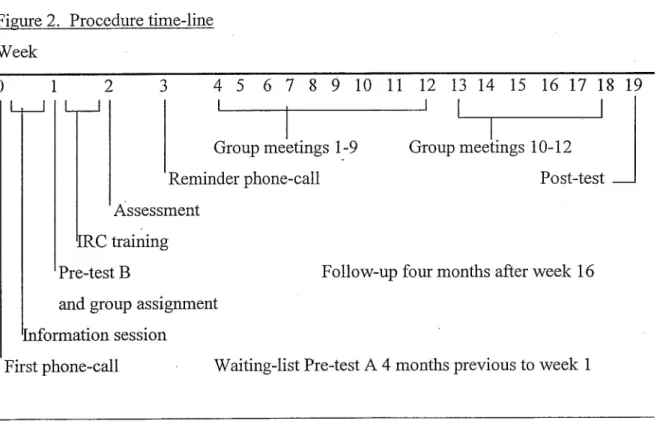

2. Procedure time-line 134

3. Jack’s daily ratings of his personal definition of loneliness 188 4. Jack’s personal inventory ratings and therapeutic events 190 5. Tom’s daily ratings of his personal definition of loneliness 201 6. Tom’s personal inventory ratings and therapeutic events 202 7. Mary’s daily ratings of her personal definition of loneliness 211 8. Mary’s personal inventory ratings and therapeutic events 212

176 176 178 178 181 181 183 186 187 191 191 194 195 196 199 199 203 203 205 206 206 209 209 213 213 214 214 215 215 LIST OF ANNEXES

A. THREE CASE ILLUSTRATIONS A.l. INTRODUCTION

A.2. JACK

A.2.1. Assessment A.2.2. Pre-test scores

A.2.3. Intervention objectives A.2.4. Intervention

A.2.5. Client comments (at meeting 12 and post-test) A.2.6. Outcome

A3. TOM

A.3.1. Assessment A3.2. Pre-test scores

A3.3. Intervention objectives A.3.4. Intervention

A3.5. Client comments (at meeting 12 and post-test) A3.6. Outcome

A4. MARY

A.4.1. Assessment A4.2. Pre-test scores

A.4.3. Intervention objectives A.4.4. Intervention

A.4.5. Client comments (at meeting 12 and post-test) A4.6. Outcome

A.5. GROUP DYNAMICS AND EVENTS A. 5.1. Computer-mediated communication A.5.2. Group dynamics

A.5.3. Treatment adherence A.5.4. Therapist behaviour A. 6. CONCLUSION

Loneliness and Teltherapy xvii LIST OF ANNEXES (cont.)

216 219 221 225 268 270 275 278 281 287 296 B. Recruitment posters

C. List of recruitment sources D. Consent form

E. Questionnaires

F. Personal definitions of loneliness

G. Index of the social skills training manual H. Test on social skills training manual

I. Description of interactions self-observation form J. Personal inventory examples

K. Checklists for each step of the intervention L. Example of completed checklist

INTRODUCTION

The present thesis concerns several areas of research that, combined, have not yet been investigated: intervention for loneliness via computer-mediated communication (CMC) among people with physical disabilities.

Computers have been used in the domain of psychology since the 1960s with the appearance of large mainframe computers that were able to bulk process pencil and paper tests and questionnaires. Over time, they were used to complete data analysis and create databases. With the widespread availability and low cost of personal computers and access to computer networks such as the Internet, psychology is taking on new directions. Databases and data-analysis are now accessible from our own homes and offices, and computers are now involved in psychology testing and evaluation, training of neuro- psychological skills, data-collection, research, etc. A new and exciting domain of psychology is that of computer-mediated therapy. Several computer-mediated health delivery systems have already been developed. These client-provider systems range from making textual health information available through Web sites, question-answer services through e-mail and bulletin boards, and interactive health information either provided by specialists or through discussion groups of people with similar concerns via inter-relay- chat (IRC). Psychologists are already taking advantage of these systems to provide computer-mediated therapy, yet few investigators have examined the effectiveness, advantages, disadvantages, cost-efficiency and efficacy of such services.

Psychotherapy provided via synchronous CMC is one such under-researched area of tele-health. Yet, psychologists, counsellors, therapists, and even unqualified people are offering these services. Surprisingly, psychologists are flocking towards this new form of service provision and attempting to develop policies based on positive anecdotal or case-study information. These services are assumed to be efficient and effective.

Regardless of this lack of experimental evidence supporting the effectiveness and efficiency of computer-mediated tele-psychotherapy, there is ample information and data

Loneliness and Teltherapy xx in the literature concerning certain features of CMC, such as anonymity, possibility for social contacts, decreased status clues, and ability to join people who are similar despite physical distance and barriers. These "social" features of CMC have an appeal to the lonely person who, generally, is dissatisfied with their social relationships. Additionally, the nature of this form of communication allows people with physical disabilities, who share a common awareness of barriers to their social participation and common

experiences, to meet and find solutions to their problems together, despite geographical distance and physical barriers.

As for the literature on loneliness, it is quite extensive, but generally based on the experience of white, middle class adolescents, college students and elderly

“representative” samples. Loneliness among people with physical disabilities is an area of research that has largely been ignored by social scientists. This is surprising given that the social realities of this population differ from that of the general population.

Accordingly, considering that intervention for loneliness typically addresses the social cognitions, behaviours, affects, experiences and networks of the lonely person,

intervention among people with physical disabilities should be adapted to their social realities. Again, intervention addressing long-term or chronic loneliness that is adapted to this population and their special needs is limited.

This study experimentally investigates the efficacy of cognitive behavioural goal- oriented group computer-mediated therapy for loneliness among lonely people with physical disabilities. That is, it explores whether an empirically validated therapy for loneliness, adapted to the special needs of people with physical disabilities, can be applied via IRC and result in significant improvement in the client that cannot be attributed to the passing of time. If so, research can then take on the challenge of determining whether it is more or less effective or efficient than other forms of therapy.

Chapters 1 and 2 are concerned with loneliness. Chapter 1 presents empirical findings in the field of loneliness as well as the cognitive approach to defining and

conceptualising loneliness, the approach used within the research project presented in Part two. With regards to empirical findings, the reader will find information regarding who is lonely, as well as what factors are affected by, cause and maintain loneliness such as social skills, social anxiety, erroneous cognitions, causal attributions, self-esteem, and coping strategies. As you will see, many of these factors create a vicious circle, whereby these factors influence loneliness and loneliness, in turn, influences these factors.

Finally, a brief criticism of the state of loneliness research will be provided since much of this information must not be taken at face value.

On the other hand, chapter 2 describes cognitive-behavioural models and suggestions for assessing and treating loneliness. In addition to presenting a sample of these models, it also provides descriptions of strategies designed to help people develop emotional ties. Many of these models, suggestions, and strategies will be integrated into the intervention used in this study.

Chapter 3 concerns the social participation of people with disabilities. In addition to identifying barriers to their social participation, this chapter explores how factors influencing interpersonal attraction are affected by negative attitudes towards this population. This chapter also discusses how the use of certain social skills can help eliminate these barriers, including negative attitudes. Furthermore, the question of whether people with disabilities are lonelier than the general population is addressed. Finally, this chapter describes interventions that have been successful in reducing loneliness among people with disabilities.

The last chapter of Part 1 concerns computer-mediated communication (CMC) and its applications within mental health service delivery. More specifically, it examines why people who are lonely may be attracted to CMC. It also reviews past and present applications of computers and computer networks in the delivery of mental health service and discusses their increasing involvement in the provision of therapy despite a lack of empirical evidence concerning its viability. Furthermore, this chapter addresses ethical

Loneliness and Teltherapy xxii issues and dilemmas in the provision and research of computer-mediated mental health related services.

Part two concerns the research project regarding the efficacy of intervention for loneliness conducted via IRC versus a wait-list control. The first chapter in this section of the thesis (chapter 5) presents the method used, including the recruitment procedure, a description of the instruments and tools used, and details concerning the general

procedure. This detailed description of the method will facilitate comprehension of the results, guide the discussion of the results, and make it possible to replicate and address the limitations of the study. At this point, readers who are interested in a more detailed description of the intervention are referred to Annex A. It presents three case illustrations in order to describe the intervention and demonstrate how the intervention was tailored to the client. One group was selected for this chapter because it, as well as the participants that composed it, was representative of the other groups and clients that partook in this study. For each client, there are descriptions of their assessment, pre-test data,

intervention objectives, intervention and outcomes. These descriptions are followed by a brief overview of CMC related events throughout intervention, group dynamics, and therapist behaviour.

The following chapter (7) presents the results of this study based on statistical analysis of the total sample. The results of these analyses are discussed in chapter 8. This chapter also covers some of the limitations and attributes of this study, as well as positive and negative participant comments about the therapy and using IRC as a medium for intervention. Practical implications and special concerns regarding the provision of online services are discussed, along with some ideas for future research.

Loneliness and Teletherapy 1 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

In order to orient and properly justify choices in conducting empirical research, the themes and elements included in the project should be carefully examined. Indeed, it was based on an extensive review of the literature that the research idea and its

hypotheses were developed. During Part One, the author provides a theoretical review of the key elements of her research project: loneliness theory, empirical research on

loneliness, treatment of loneliness, the social participation of people with disabilities, as well as computer-mediated-communication (CMC) among people who are lonely and as a medium for delivering mental health care.

The idea for this project stemmed from an observation that lonely English speaking and foreign acquaintances in a French speaking university relied on CMC to provide them contact with their own culture and maintain their links with family and friends. At the same time, telehealth came to the forefront of debates in the field of medicine, as computer networks became a standard element within hospitals. Data and information from a review of CMC revealed its attractiveness to people who are lonely and its potential use in providing mental health care. These findings prompted the choice of loneliness as the subject of intervention, as well as the selection of participants (people who may have difficulty accessing specialized mental health services).

Since computer-mediated therapy for loneliness among people with disabilities is virtually unexplored area of research and clinical practice, it was with caution and

through careful examination of previous research reviewed in Part 1 that a relevant, well- designed and viable study on the topic could be developed and conducted.

LONELINESS: EMPRICAL AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Loneliness and Teletherapy 3

1.1. Who is lonely? Drawing the portrait of the lonely person

The wealth of available loneliness literature is not surprising, given that loneliness is a universal human experience. “(It) is something that we all have to deal with at one time in our lives. The person who says “I am never lonely” either does not understand the word or is fooling himself (p.3)” (Tanner, 1973). About 11 % to 26 % of individuals complain of loneliness at a given time (Peplau, Russell, & Heim, 1979). The prevalence of those who experienced pervasive feelings of loneliness during much of their life varies between 10 to 30 % (Sermat, 1980). These findings concur with Bradburn’s (1969) early survey findings that at least 25 % of the American population felt “very lonely or remote from other people” during the past two weeks. Furthermore, in a survey of first year undergraduate students, loneliness prevalence figures are even higher. Seventy-five percent had experienced loneliness at least occasionally since arriving at college, while over 40 % said that their feelings of loneliness had been moderate to severe (Cutrona,

1982). Many researchers have endeavoured to identify who these lonely people are, attempting to identify demographic characteristics associated with loneliness such as age, gender, marital status, and socio-economic status. By identifying the lonely person’s profile, preventative measures, targeting potential lonely populations, could be put into place.

The relationship between age and loneliness is not as obvious as people believe it to be. North American society has adopted the stereotype that older people are lonely; a stereotype that is endorsed by both the young and old (Gambrill, 1996; Rubenstein & Shaver, 1982). However, research proves this age-attributed loneliness to be wrong, showing that adolescents are possibly loneliest and that loneliness may actually decline with age (Peplau, Bikson, Rook, & Goodchilds, 1982; Rubenstein & Shaver, 1982). These finding should not come as such a surprise. Rates of reported loneliness are higher

among adolescents, ranging from 20 % to 50 % (Brennan, 1982). Nonetheless, some studies have observed that loneliness may begin to increase again during later stages of old age when physical health, mental health and social networks begin to deteriorate (Peplau, Bikson, et ah, 1982; Schultz & Moore, 1988).

As for sex differences in loneliness, their existence has been a subject of great debate in loneliness research. While some investigators claim that men are lonelier than women (Mastekaaga, 1997; Schultz & Moore, 1986; 1988; Stokes & Levin, 1986), others found that women are lonelier (Berg, Mellstrom, Persson, & Svaniborg, 1981; Brennan, 1982; Medora & Woodward, 1986). Some studies have found no sex differences (Cutrona, 1982; Jackson & Cochran, 1991; Russell, 1982)! Faced with these

discrepancies, Borys and Perlman (1985) decided to tackle the question through close examination of the literature and empirical research. They found that sex differences depend on the kinds of questions asked. They combined the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980) data of 28 subject samples and found that men obtained higher scores (higher loneliness) than women. However, when they examined the self-rating data of relevant samples, the opposite relationship held true. The main difference between these two sets of samples is that the word “loneliness” is used in self- ratings, while the word loneliness is not used within the UCLA Loneliness Scale. Borys and Perlman (1985) suggested that males are more reluctant to admit they are lonely because lonely males are more socially stigmatised than lonely females.

While it is not clear which gender is lonelier, it is clear that single, divorced, separated, and widowed people are consistently found to be more lonely than married people or people involved in a romantic relationship (Bahr & Harvey, 1979; Kivett, 1979; Peplau & Perlman, 1981). In fact, in a study of 38 000 adults, loneliness was higher among those who were separated than those who were married (Mastekaaga, 1997). However, some authors noted that the difference between married and non-married people is generally accounted for by the greater loneliness of those who are separated, divorced or widowed (Peplau & Perlman, 1981). According to Peplau and Perlman’s

Loneliness and Teletherapy 5 (1981) findings, loneliness may actually be a reaction to the loss of a romantic or

marriage partner rather than to the absence of such a relationship.

Generally, research has found no relationship between loneliness and socio- economic status. While adults who are unemployed have been found to be lonelier (Mastekaaga, 1997), no association between socio-economic status and loneliness has been found among adolescent and college students (Brennan, 1982; Medora &

Woodward, 1986). Other researchers have found no relationship between income and loneliness among gay men, widows and rural elderly people (Berg et ah, 1981; Kivett,

1979; Martin & Knox, 1997). These data concur with Bahr and Harvey’s (1979) finding that low income was not related with loneliness among widows, but dissatisfaction with socio-economic status was. These results lend support to the important role of life- satisfaction and happiness in loneliness, and suggest that their relationship, like for the other demographic variables discussed here, is more complicated than a correlation between a demographic characteristic and scores on a measure of loneliness.

1.2. Loneliness: Theoretical Background

Most people intuitively know what loneliness means. When asked about loneliness in international surveys and during empirical research, including the correlational studies regarding associated demographic variables, most respondents readily answer without requiring clarification about the term (Peplau & Perlman,

1982b1). Yet, it would be foolish to assume that the meaning of the term “loneliness” is similar for everyone since it is such a vague concept.

While there are different definitions, typologies and psychological approaches to loneliness, careful consideration of loneliness theories reveals that they generally agree

1 Peplau & Perlman published, in 1982(a), what might be considered the first comprehensive review of empirical literature on loneliness.

on the ideas that loneliness is a subjective experience, that it is not synonymous with social isolation, and that it is the result of social deficiencies (Peplau & Perlman, 1982a). Peplau and Perlman (1982a), in their analysis of various loneliness theories, also

observed that differences in conceptualizations particularly concern the nature of the social deficiency. Furthermore, upon careful examination of the approaches to loneliness described in literature (e.g. Phenomenological, Existentialist, Sociological, etc.2), the author of the present work also noted that other available theories and conceptualisations of loneliness tend to adopt a limited scope with regards to the causes of loneliness, and that their foundations are rich in theory that have been rarely tested.

Despite the lack of a universally acceptable definition of loneliness, the cognitive approach to loneliness is the most widely adopted by clinicians and researchers,

particularly, but not exclusively, by those who adhere to cognitive and cognitive- behavioural approaches to psychology. The selection of this approach for the current study is due to the fact that the cognitive approach to loneliness appears to be the most comprehensive and most empirically supported. Furthermore, it offers an operationalized definition of loneliness, thus allowing for its measurement.

Its definition suggests that the intensity of loneliness - or lack of - is moderated by the thought processes of a person who is operating in a contemporaneous manner. This means that most of the causes proposed by various approaches and theories are potentially valid, since they may have an impact upon a person’s thought processes or life situation. Such an encompassing approach allows for the integration of much empirical research that validly demonstrates determining and maintaining factors of the loneliness experience.

As such, the cognitive approach to loneliness also allows for flexible cognitive- behavioural treatment strategies by offering a variety of modifiable causes and

Loneliness and Teletherapy 7 maintaining factors as treatment targets. In fact, therapies specifically targeting

loneliness and their treatment techniques, which have been empirically validated in controlled studies, fall within the scope of cognitive and cognitive-behavioural

approaches (Gambrill, 1996; Rodway, 1992; Rook- 1984b, 1988; Rook & Peplau, 1982).

Because of these qualities, it is not surprising that this approach is the most popular and most cited within loneliness literature. Unfortunately, there seems to be no literature available that specifically integrates concepts of various theoretical approaches to loneliness under an umbrella or trans-theoretical perspective. And while such an endeavour does not fall within the scope of this thesis, the remainder of this chapter describes the cognitive approach and presents empirical findings that contribute to a comprehensive understanding of loneliness and its causes, which is essential to providing efficacious interventions to a study population presenting with heterogeneous loneliness experiences.

1.2.1. The cognitive approach to loneliness

According to the cognitive approach, loneliness is considered to be a

dissatisfaction with one’s social relationships. It also emphasises cognitive processes regarding one’s perception and assessment of their social relationships. The element of cognitive appraisal of social relationships is present within the definitions of Flanders (1982), and Sadler and Johnson (1980).

“Loneliness is an adaptive feedback mechanism for bringing the individual from a current lack of stress state to a more optimal range of human contact in quantity or form. “Lack of stress” means too little of a given input, human contact in this instance (Flanders, 1982, p. 170).”

“Loneliness is an experience involving a total and often acute feeling that constitutes a distinct form of self-awareness signalling a break in the basic network of the relational reality of self-world (Sadler & Johnson, 1980, p. 39).”

However, the cognitive approach emphasises more particularly the perceived discrepancy between two factors; desired and achieved patterns of social relationships. For example, even if a person has many “friends”, he or she may feel lonely if the level of desired intimacy with one friend in particular has not been achieved. Cognitive definitions of loneliness thus suggest that cognitive processes play a role in modulating the intensity of loneliness. The definitions of Sermat (1978), Lop ata (1969), as well as Perlman and Peplau (1981) have provided operationalized definitions of loneliness by specifically referring to this perceived discrepancy and the role it plays in determining the experienced intensity of loneliness.

“Loneliness is a sentiment felt by a person... [experiencing] a wish for a form or level of interaction different from one presently experienced (Lopata, 1969, p. 249-250) ”

“Loneliness... is an experienced discrepancy between the kinds of

interpersonal relationships the individual perceives himself as having at the time, and the kinds of relationships he would like to have, either in terms of his past experience or some ideal state that he has actually never experienced (Sermat, 1978, p. 274) ”

“Loneliness is the unpleasant experience that occurs when a person’s network of social relations is deficient in some important way, either quantitatively or qualitatively (Perlman & Peplau, 1981, p. 31).”

As mentioned above, differences in conceptualisations of loneliness

Loneliness and Teletherapy 9 refer to a discrepancy between desired and achieved levels of social contact, Peplau and Perlman (1982a) identified two other approaches to defining loneliness; one that emphasises social deficiencies in human intimacy needs3 and another

emphasising social reinforcement deficiencies4. Within the human intimacy needs approach to loneliness, which reflects a psychodynamic perspective, loneliness is a mechanism that drives or motivates a person to ensure that they will not be isolated and vulnerable to extinction. Thus, the human intimacy needs approach suggests that loneliness is the subjective reaction to rational deficits in relationships. On the other hand, social reinforcement theory based definitions, which fall within the behavioural perspective, assert that the relationship deficiency is insufficient social reinforcement. According to this approach, social relationships are a form of reinforcement, and the quantity and type of contact that a person considers satisfying are the result of their reinforcement history.

While the three approaches to defining loneliness appear to be distinct with regards to what they consider to be relational deficiencies, careful examination of these definitions reveal that both the human intimacy needs and social

reinforcement based definitions can be considered within the scope of the cognitive approach. First, the cognitive approach does not preclude the idea that the

perceived discrepancy between desired and achieved relational contact is indeed a rational deficit, and that a person’s desired level of relational contact corresponds to what that person considers to be sufficient to keep him or her emotionally,

physically, and psychologically safe. Secondly, the cognitive approach does not preclude the idea that desired and achieved levels of social contact are influenced by the amount of social reinforcement desired or derived from social contact. In fact, human intimacy needs, as well as past and current social reinforcers, could theoretically be viewed as one of many factors determining “desired” quantity or

3 For additional reading concerning human intimacy needs theory, consult the works of Bowlby (1973) and Parkes (1973).

quality of social contact, as well as personal gauges for determining whether it has been achieved. This analysis demonstrates how other perspectives concerning the causes of loneliness can be integrated within a more encompassing approach that recognises the role of many causal factors in the loneliness experience.

1.3. Causes, maintaining factors, and effects of loneliness: A vicious circle

As mentioned above and based on the cognitive definition, loneliness can be precipitated by a change in either achieved level of social contact, or desired level of social contact. Accordingly, Perlman and his colleagues have been able to account for many findings in the literature by proposing that thoughts are processes within the person who is operating in a contemporaneous manner. Therefore, it is possible for individual and environmental factors, as well as historical and current influences to impact upon achieved and desired social contact, as well as a person’s cognitive processes concerning the discrepancy between them; thus making the cognitive approach amenable to the integration of several other theories concerning what causes and maintains loneliness, as well as how to cope with it.

According to the theory, changes in achieved social relationships are precipitated by four types of events (Peplau & Perlman, 1982a): the ending of a close relationship (death, break-up), physical separation from friends and family (moving, going to college), changes in status (promotion, retirement, unemployment), and change in qualitative aspects of relationships (degree of conflict, trust). Cutrona (1982) surveyed college students as to the key events or situational factors that had triggered current or previous episodes of loneliness. The most reported events were leaving family and friends to begin college (40 %), break-up of a romantic relationship (15 %), family events such as parental divorce or marriage of a sibling (11 %), and difficulties with schoolwork (11 %). The remaining events included isolated living situations, rejection by a fraternity or sorority, medical problems and having one’s birthday forgotten. These finding

Loneliness and Teletherapy 11 corroborate with those of Jones, Cavert, Snider, and Bruce (1985) who asked people to write descriptions of the kinds of life situations and events that cause them to feel lonely. The most common experiences reported by their subjects were separation from or

rejection by others and interpersonal conflict.

For adherents to the cognitive approach, desired social relationships may fluctuate according to the individual’s mood or situation, which are influenced by what are often referred to as factors that predispose individuals to becoming lonely. However, cognitive theory based loneliness literature and research often do not distinguish between factors that predispose a person for feeling lonely, causal factors, maintaining factors and the

effects of loneliness. “We find it useful to distinguish among antecedents of loneliness, characteristics of the experience of being lonely, and ways in which people cope with loneliness. However, in loneliness as in many similar phenomena, causality is complex and probably circular (p. 8)” (Peplau & Perlman, 1982a). For example, a person with a tendency to not self-disclose may have difficulty increasing intimacy with acquaintances and friends. The result might be dissatisfaction with his or her social relationships. However, loneliness and the negative affect associated with it may lead the person to adopt a passive social behavioural approach in which he or she does not even make an effort to self-disclose. Again, this reduced self-disclosure affects the quality of his or her social relationships even more. In light of this complex causality, most research and literature reviews do not differentiate between the specific roles of the various environmental and personal factors associated with loneliness. Instead, they tend to suggest that these factors and the loneliness experience interact. This inter-relationship might even be a called a vicious circle (see Figure 1).

Several investigators have proposed classifications and models of the causai and maintaining factors of loneliness. Rubenstein and Shaver (1982) proposed five categories of reasons why people feel lonely based on a national survey of the general population: Being unattached, Alienation, Being alone, Forced isolation and Dislocation. Jones, Cavert et al. (1985) reviewed the literature concerning situations and events associated

with loneliness. They categorised these factors according to Temporal factors (time, day, week), Social contact, Relational status, Failure, Relational loss, Social network, New situations, Indirect barriers, Low income and Inadequate transportation. Rokach (1997) asked over 500 people from the general population to reflect on their previous

experiences of loneliness and to indicate what caused it in their own opinion. They related their responses to five factors that comprise the experience of loneliness: Personal inadequacies, Developmental deficits, Unfulfilling intimate relationships, Relocations and significant separations, and Social marginality.

Figure 1. Loneliness: A vicious circle.

Loneliness Negative Reactions by Others Negative Reactions to Others Awkward and Unresponsive Social Behavior SOURCE: Brehm, 1992 (p. 336).

While these categorisations are useful, they do not sufficiently cover the factors that the author of this thesis considers to be relevant when examining what causes, maintains and results from feelings of loneliness. Unfortunately, these categories of causal and maintaining factors concentrate mainly on environmental context and situational factors, neglecting potentially modifiable factors that could be subject to

Loneliness and Teletherapy 13 interventions. Peplau and Perlman (1982a) distinguished between personal

characteristics and cultural and situational factors as causal factors. Personal

characteristics contribute to loneliness by reducing the person’s social desirability and opportunities for social relations. These characteristics may influence one’s behaviour in social situations, contribute to unsatisfactory patterns of interaction, and affect how one reacts to changes in his or her actual social relations. These authors regard personal factors as variables that may predispose people to loneliness and make it harder for them to overcome it. On the other hand, cultural and situational factors are factors that reside within the environment such as values, attitudes and personal experiences. This broad classification system is interesting since it covers both environmental and personal variables in understanding causal and maintaining factors of loneliness. While taking into account the roles of both kinds of factors in causing/maintaining loneliness, the variable considered here have been classified into the following categories: a)

Cultural/environmental context and current social network, b) Cognitions and attitudes, c) Interpersonal behaviour, d) Affect, mood and suicide, e) Personality and personal

characteristics, f) Social and loneliness coping strategies, as well as g) Developmental experiences and social learning history.

1.3.1. Cultural and environmental context, and current social network

Opportunities to meet people and the quality of interactions may differ from one environment or cultural context to another. Some environments, such as college, are rich in these opportunities, while others, like a small business work environment, may provide very few. The environment may also pose contingencies on the quality of social

interactions, such as pollution, the size of public meeting places and the architecture of possible meeting places (e g. availability of benches, level of comfort, accessibility). For example, Krause (1993) found that noise, high crime rates and crowding are decreasing opportunities for positive exchanges. Along the same lines, Schiller (1989) found that that the availability of public spaces where informal exchanges can take place has been

decreasing. Additionally, the kinds and number of roles a person may have might also influence loneliness. A person balancing several roles involving a hectic schedule may have little time to develop friendships, while a person with very few social roles may find themselves deprived of situations in which they can meet new people. Furthermore, the adoption of new roles may place people in situations that they are socially unprepared for, such as roles students face during their transition to college (Cutrona, 1982). Finally,

cultural context may also have an important impact on the “pool of eligibles", or people

within the person’s environment or social network that are appropriate and socially approved of partners (Brehm, 1992). All of these factors place contingencies on the possible level of achieved social contact a person can attain.

Loneliness research regarding environmental and cultural context have mainly focussed on the related themes of social networks, social isolation and social support. Research generally agrees that size of social network is not as important as qualitative aspects of the network such as density and diversity. Among four social network variables (number of people subject is close to, density of network, frequency of

supportive behaviour reception and percentage of relatives), network density5 was most related to loneliness, while percentage of relatives within the social network was not significant (Stokes, 1985; Stokes & Levin, 1986). This corroborates with the findings of Jones (1981) who had college students maintain diaries, over a period of four days, concerning their feelings of loneliness and their social interactions. He found that lonely students had the same number of conversations as non-lonely students, but lonely students had a larger diversity of social contact. These data suggest that non-lonely students have a tighter knit social network.

Some authors have argued that quantitative aspects of the social contact may not be as critical as the quality of social contact (Evans, 1983; Williams & Solano, 1983). In

5 Network density, according to this study, is the proportion of total possible number of relationships that actually exist among members of the respondent's network. It reflects the degree that network members have relationships with one another.

Loneliness and Teletherapy 15 fact, loneliness literature brims with studies that have empirically supported cognitive definitions of loneliness, which suggest that lonely people lack meaningful and intimate social and personal relationships. In Martin and Knox’s (1997) study, intimacy and social support from others were the most salient predictors in a regression model explaining over half of the variance in gay men’s UCLA scores. In fact, having an intimate

relationship, rather than being married, is more related to loneliness among elderly people (Peters & Liefbroer, 1997). Stokes (1985; Stokes & Levin, 1986) found loneliness to be inversely related to the number of people that they feel “close to”. This concurs with the finding that loneliness is also inversely related to degree of acquaintance with

conversation partners and the emotional quality of interactions (Jones, 1981). Derlega and Margulis (1982) found that the absence of appropriate social partners for desired activities is positively linked to loneliness, as are a lack of opportunities for social comparison and feedback. Moreover, Rook (1984a) found the number of people with whom elderly widows had conflictual relationships is positively correlated with loneliness. In fact, Cutrona (1982) found that qualitative versus quantitative social support variables account for a larger proportion of variance in loneliness.

Considering that, according to a nation-wide survey in 1980, one in six Americans have no one to confide in, that 5 % do not know a person they could turn to in times of trouble, and 19 % did not have “many good friends” (Campbell, 1981), perception of social support may play an important role in the high rates of loneliness among the general population. Accordingly, loneliness is related to subjective ratings of frequency of reception of supportive behaviour (Stokes, 1985; Stokes & Levin, 1986). Among college students, loneliness is predicted by a small social support network (versus social network), and less close relationships with network members (Vaux, 1988).

Furthermore, adolescents’ sense of community in school and the neighbourhood, as well as adults’ sense of belonging are negatively correlated with loneliness and various measures of social support (Hagerty, Williams, Coyne, & Early, 1996; Pretty, Conroy, Dugay, Fowler, & Williams, 1996). These findings suggest that while it is possible for lonely people to change the environmental or cultural context within which they live in

order to increase their access to potential social contact and support, it may be even more important to ensure the quality of a person’s social relationships.

1.3.2. Cognitions and attitudes

The cognitive perspective emphasises the role of causal attributions in maintaining loneliness. For cognitive theorists, loneliness is likely to be especially intense and long-lasting when people believe that it is due to their own personal characteristics (enduring and stable, internal to the person), rather than external and unstable causes (Michel a, Pep lau, & Weeks, 1982; Peplau, Miceli, & Morasch, 1982; Ponzetti, 1990). Examples of internal causes are being unattractive, not knowing how to make friends and not making an effort. External causes include being rejected, being in a situation where it is difficult to make friends, and bad luck. Stable causes are relatively unchanging features of the situation (being in large classes, living in an isolated area) or the person (personality, social skills). Unstable causes are factors that are relatively easy to modify such as luck or effort. It is hypothesised that a belief that things are unlikely to change may discourage people from trying to change their situation by attempting to meet new people and maintaining relationships. On the other hand, external and unstable attributions (e.g. “I’m not involved in enough group activities at this moment”) provide hope that things may change or can be modified (See Table 1).

Empirical research has provided support for this hypothesis. Horowitz, French, and Anderson (1982) found that lonely college students attribute their interpersonal failures and successes to a lack of ability and personal traits. However, lonely and non- lonely students do not differ in their causal attributions of non-interpersonal successes and failures. Additionally, Cutrona (1982) found that college students were more likely to still be lonely in the spring if they had made internal and stable attributions for their loneliness in the fall.

Loneliness and Teletherapy 17 Table 1. Causal attributions of loneliness.

LOCUS OF CAUSALITY

Internal External

I’m lonely because I’m unlovable. I’ll never be worth loving.

The people here are cold and impersonal; none of them share my interests. I think I’ll move. I’m lonely now, but I won’t

be for long. I’ll stop working so much and go out and meet some new people.

The first semester in college is always the worst, I’m sure thing's will get better.

STABILITY Stable

Unstable

SOURCE: Brehm, 1992 (p.334).

Theoretically, expectations about social relationships are cognitive mediators of loneliness, considering that loneliness is defined as a discrepancy between desired and achieved levels of social contact (quantitatively or qualitatively). For example, an

unpopular college student might expect that he would make many new friends by moving away to college (desired level), yet finds himself with just as few friends as he did before he moved (achieved level). Empirical research has also demonstrated how expectations may have a causal or maintaining role in loneliness. Cutrona (1982) found that students who later overcame their loneliness differed from those who did not by their higher expectations for future relationships, despite their initial loneliness. As well, those who remained lonely reported having changed or lowered their initial goals for desired relationships. Given Peplau and Perlman’s proposition concerning the discrepancy between desired and achieved relationships, one might expect that students who lower their relationship expectations closer to the level achieved would feel less lonely. However, this study suggests that while this discrepancy exists for lonely people, changing the desire may not be as an effective loneliness coping strategy as is actively

seeking to attain the desired level.

1.3.3. Interpersonal behaviour

Interpersonal behaviour is a variable whose relationship with loneliness has been the subject of several empirical studies. More specifically, these studies examine social skills when interacting with strangers, skills for enhancing intimacy such as self-

disclosure, as well as general interpersonal behaviour such as personal approach. Social skills have been consistently shown to be associated with loneliness6. For example, Inderbitzen-Pisaruk et al. (1992) found that when teachers rated the social skills of adolescent students, the social skills of lonelier adolescents were judged as less effective. In fact, loneliness is positively correlated with adolescents’ and college students’ negative self-perception of social skills or social competence (Inderbitzen-Pisaruk et al., 1992; Spitzberg & Canary, 1985). This relationship is not surprising given that poor social skills make it difficult to establish and maintain quality relationships.

Establishing interesting relationships begins with initiating contact with others. Savin-Williams and Berndt (1990) found loneliness to be associated with difficulty initiating close peer relationships. This concurs with Medora and Woodward’s (1986) finding among college students whereby loneliness is associated with self-rated ease of making friends. As for skills related to maintaining conversation, several dyadic conversation studies between strangers have been conducted. Lonely college students tend to ask fewer questions, change the topic more frequently and respond slower (Sloan & Solano, 1984). Loneliness is also associated with disruptive self-focused versus

partner-focussed attention (Jones, Hobbes, & Hockenbury, 1982). Furthermore, Jones et al. found that by increasing the frequency of partner attention statements through social skills training, loneliness significantly decreased. Indeed, lonely people are considered to 6 Readers may consult Jones, Freeman, & Goswick (1981) and Inderbitzen-Pisaruk, Clark, & Solano (1992) for critical reviews of the relationship between social skills and loneliness.

Loneliness and Teletherapy 19 be less socially competent by their interaction partners in dyadic conversation

experiments than are non-lonely people (Segrin, 1999; Spitzberg & Canary, 1985), and to be evaluated more negatively by the opposite sex (Jones, Sansone, & Helm, 1983).

Wittenberg and Reis (1986) looked at college roommate pairs and found that lonely people are also more deficient in relationship formation and maintenance skills, according to self-report measures of social skills and assertiveness. Furthermore,

loneliness has been associated with poor dating and conflict resolution skills (Wittenberg & Reis, 1986; Rook & Peplau, 1982; Young, 1986).

Many investigators have suggested that lonely people are also slow to develop intimacy due to their lower levels of self-disclosure, higher social inhibition, and low social risk taking. Lonely male college students speak less with strangers and

roommates, according to themselves and an objective rating scale during a dyadic

conversation study (Sloan & Solano, 1984). Hansson and Jones (1981) noted that lonely people express their opinions less frequently and are less confident about their opinions. Furthermore, Jones et al. (1982) used an objective scale for observing behaviour and found that lonely young adults do not disclose as much personal information as those who are not lonely in brief dyadic interactions. These findings coincide with Solano, Batten, and Parish’s (1982) findings that lonely people are judged as more difficult to get to know. Thus, it is not surprising that people who interact with lonely people perceive lower levels of intimacy (Chelune, Sultan, & Williams, 1980). Strangely, people who desire greater quality and quantity of social contact appear to be uninterested in social interaction. However, Solano et al.’s (1982) research shows that loneliness is also related to efforts to achieve intimacy too quickly, causing others to feel uncomfortable or to withdraw.

Although it seems that lonely people do not use appropriate social skills for developing and maintaining interactions and social relationships, it should not be

assumed that they do not possess these skills. In fact, Vitkus and Horowitz (1987) found that lonely people often possess skills knowledge, but are more likely than non-lonely

people to not use them, adopting passive interpersonal roles instead. When these investigators manipulated the social condition so that lonely participants adopted an active or passive role, participants who were put in an active role condition displayed more appropriate social skills related to maintaining conversations, such as addressing their partner, generating effective solutions to hypothetical problems and conversing for a time; their skills were comparable to those of non-lonely people. Keep in mind that subjects were university students, for whom loneliness is often a transitory experience (Cutrona, 1982) and whose social skills may be superior to peers who did not go or could not attend college. Moreover, in a longitudinal study by Segrin (1996), social skill ratings (objective and subjective) did not predict subsequent loneliness, but predicted subsequent social anxiety, thus suggesting that when people are lonely, they do not use their social skills. This concurs with the findings of Solano and Koester (1989) who found that participants who are more anxious are less likely to use appropriate social skills.

The relationship between loneliness and interpersonal behaviours is not surprising since lonely people’s attitudes towards others are more negative. In dyadic and group interaction settings, they are less attracted to their partners, are less interested in

continuing the interaction, and are less interested in developing relationships with their partner (Jones, 1981; Jones et al., 1983). This is not only true of interactions with

strangers or acquaintances, but for people who know each other well. Furthermore, when lonely people were read interpersonal scenarios, they were more likely to interpret the actions of others (family members, neighbours and authority figures) more negatively than non-lonely participants (Hanley-Dunn, Maxwell, & Santos, 1985). Research has also provided indications that lonely people don’t like other people very much (Rubenstein & Shaver, 1980), mistrust others (Jones et al., 1981; Rotenberg, 1994; Vaux, 1988), and are more hostile (Check, Perlman, & Malamuth, 1985; Hansson, Jones, Carpenter, &

Remondet, 1986).

On the other hand, lonely subjects also expect to be negatively rated by others (Christensen & Kashy, 1998; Jones, 1981; 1982). Not surprisingly, given these types of

Loneliness and Teletherapy 21 interpersonal behaviours and attitudes, lonely people are rated more negatively by others overall (Jones, 1981; Jones et al., 1983). Even lonely subjects, when placed in dyadic or group interaction laboratory situations, rated themselves as having been less honest, open, warm and friendly in dyadic conversations as compared to non-lonely partners (Jones,

1981). Given the social nature of loneliness, the strong relationships between social behaviour and loneliness, lonely people’s awareness of their inappropriate social

behaviour, as well as the potential for social behaviours to be trained and modified, it is not surprising that social skills training is often a core element of cognitive-behavioural interventions.

1.3.4. Affect, mood, and suicide

Social anxiety and depression are the most well documented emotions associated with loneliness. However, investigators have also examined other emotional correlates of loneliness. Lopata (1969) surveyed widowed women in order to determine the emotions and desires related to loneliness. He was able to discern three factors: Longing for the past, frustration with the present, and fears about the future. Rubenstein, Shaver, and Peplau (1979) conducted a nation-wide survey and, after completing a factor analysis, found that loneliness is often accompanied by four types of emotions: desperation, impatient-boredom, depression and self-depreciation. Many of the emotions listed by Rubenstein et al. have been confirmed as correlates of loneliness in several studies. Paloutzian and Ellison (1982) found that lonely people felt more depressed, rejected, misunderstood, unwanted, empty, worthless, frustrated, isolated, and unloved.

Loneliness is inversely related to current self-rated happiness among elderly people during the past year (Medora & Woodward, 1986; Schultz & Moore, 1984). Among adolescents, loneliness’ average duration and number of incidences in the past month are positively related to state anxiety, trait anxiety, and depression. On the other hand,

loneliness is inversely related to happiness and life-satisfaction among adults and elderly people (Moore & Schultz, 1983; Schultz & Moore, 1984).

Of particular interest to loneliness researchers is the strong relationship between measures of loneliness and social anxiety7. Social anxiety is a feeling of discomfort or distress that occurs in contexts involving other people. It results in the avoidance of related situations and distracts a person from performing in social situations, often

hampering success. For example, a person who feels extremely anxious when conversing with somebody may poorly apply conversational skills such as paying attention to clues about the receiver’s interest, interrupting, rambling and changing subjects quickly. The extreme discomfort that this person may have may lead them to end the conversation prematurely, and by doing so, reduce the anxiety, thus reinforcing avoidance of conversing with others. Thus, it is easy to see how social anxiety might create barriers for establishing meaningful social relationships.

Shyness is another concept that is closely related to social anxiety and loneliness. It is characterised by a reluctance to initiate social exchanges and the subjective

experience of anxiety in social situations. Shy people report having difficulty meeting people and making friends, and are often more depressed, lonely and self-conscious than non-shy people (Cheek & Melchoir, 1990; Mahon & Yarcheski, 1992). Being

somewhat less extreme than social anxiety, it is an experience reported by a large majority of the population. Zimbardo (1977) found that 90 % of people report feelings of shyness sometimes and 50 % report that their shyness is a significant problem at certain times. As well, more than a third of Cheek and Melchoir’s (1990) sample reported having been shy since childhood.

Depression is also often related with loneliness. Like depression, which is characterised by global (affecting many areas of life) stable, internal attributions about negative experiences (Sweeney, Anderson, & Bailey, 1986), loneliness is even more

7 For a critical review of the literature on this subject, please refer to Inderbitzen-Pisaruk et al., 1992; Jones, Rose, & Russell, 1990; Moore & Schultz, 1983.