❒

❒

❒

❒ Résumé

Afin d'adresser le problème de la surcharge informa-tionnelle, nous introduisons le concept de la préférence intrinsèque pour un média de communication (IPMC), ceci afin de mieux expliquer le choix d'un média au niveau individuel. Nous testons un modèle où l'IPMC est un médiateur entre d'une part, l'introver-sion/extraversion et d'autre part, l'utilisation du cour-rier électronique professionnel, ainsi que l'utilisation des réunions en face à face par un manager. Le modèle explique comment l'introversion est directement néga-tivement relié à l'utilisation du courrier électronique – un extraverti va communiquer plus qu'un introverti. Cependant, notre modèle de suppression, basé sur l'ap-proche statistique de Shrout et al. montre aussi le rôle médiateur/suppresseur de l'IMPC entre l'introver-sion/extraversion et l'utilisation du courrier électroni-que, suggérant par là même, une compréhension plus large du courrier électronique et par conséquent, of-frant un nouveau moyen de réduire la surcharge infor-mationnelle, (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Mots clefs :

Surcharge informationnelle, personnalité, courrier électronique, réunions, managers

❒

❒

❒

❒ Abstract

To address the information overload issue, we intro-duce the concept of intrinsic preference for a media of

communication (IPMC), in order to better explain

me-dia choice at an individual level. We test a model where IPMC is a mediator between introver-sion/extraversion and the use of professional e-mail as well as the use of face-to-face meetings by a manager. The model explains how introversion is negatively related to the overall use of professional e-mail – an extravert will communicate more than an introvert. However, our suppression model, based on the statisti-cal approach by Shrout et al. also shows the media-tor/suppressor role of IPMC between introver-sion/extraversion and e-mail use, suggesting a broader understanding of e-mail use and therefore, offering an additional way to reduce information overload, (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Key-words:

Information overload, personality, email, meetings, managers

Surcharge

informationnelle, choix

du média de

communication et

introversion/extraversion

"Hell is other people"

*1Information Overload,

Media Choice and

Introversion /

Extraversion

Gaëtan Mourmant

Doctorant, Université Paris

Dau-phine CREPA, Centre de

Recher-che en Management &

Organisa-tion, Dauphine Recherches en

Management, CNRS UMR7088,

Georgia State University,

Robinson College of Business,

gmourmant@gmail.com

Michel Kalika,

Professeur, Directeur de l'Ecole

de Management Strasbourg,

Université de Strasbourg,

CESAG.

1

“Hell is other people”, from J.P. Sartre in No Exit, 1944

Introduction

Why people are using the "cc" function inefficiently? Why this person did send me an email instead of meeting me in my office?

Does that sound familiar? You are not alone. In a recent MIS Quarterly editorial Weber was calling for “more research on e-mail” (Weber, 2004). Indeed, following (Massey & Montoya-Weiss, 2006), (Watson-Manheim & Belanger, 2007), (Boukef & Kalika, 2006), (Kalika et al., 2007), (Kalika et al., 2008), we consider comprehension of media choice as essential to suggest ways to manage communication and information overload in general and email management in particular. For instance, we con-sider that information overload is partially caused by a misuse of communication media, especially regarding media choice, (Kalika et al., 2008). To explore such a misuse, we suggest studying personality and its link to media choice.

Indeed, McElroy insisted on the necessity of reconsider-ing personality in IS research, (McElroy et al., 2007), in order to reverse the following somewhat unproductive situation: "the predominant personal-factor variable used in subsequent models of IT adoption has been percep-tions rather than the more constant factors of personality or cognitive style". Personality has not an obvious rela-tionship with media use, for instance, an introvert may send more email than an extravert because email is his favourite media of communication, but conversely, an introvert may send less email compared to an extravert, because overall an introvert will communicate less. Therefore, our general research question is to determine to what extent personality (e.g. introversion/extraversion) influences the use of a specific media. In this study, we focus on the choice between e-mails and face-to-face (FTF) meetings. This paper is organized as follows: we first review the literature on introversion/extraversion, and then we focus on the literature related to media choice, dividing this literature between the situational influences and the researches directly related to the indi-vidual. We then present our hypothesis and we describe the methodology. Finally, we present and discuss the results and we suggest several limitations and future re-search for this study.

1.

Literature review

1.1.Introversion/Extraversion

Jung developed a theory of personality type, (Jung, 1993) which was later operationalized by Isabel Myers-Briggs and repeatedly validated in the management literature, (Gardner, 1996). The resulting Myers-Briggs Type Indi-cator (MBTI) measures four dimensions of personality. Each dimension is defined by one dichotomy. For this study, we only focus on the extraversion/introversion dimensions. The other dimensions are not reported here2. The introversion/extraversion dimension indicates the

2

Two reasons motivate our choice. First, the hypothesis are vague and not strongly supported by theory, sec-ond, although we did measure the other dimensions, none of them gave us significant results. For informa-tion, the other three dimensions are Sensing/iNtuition; Thinking/Feeling, Judging/Perceiving.

differences in people that result from “where they prefer to focus their attention and get energy (inner world ver-sus outer world)”, (Briggs-Myers, 1998). Unlike other models of personality (e.g., “the Big Five”), the dimen-sions are bipolar and not continuous. A common com-parison is to say that one has a preference for his right (or left) hand. That does not mean that one is not able to use his other hand, but simply that his comfort zone is his preferred hand. In addition, there is a strong correlation between the preference for introversion/extraversion and the measure of introversion/extraversion on a continuous scale (Big Five), (Furnham, 1996).

1.2. Situational influences on media use

Media choice has been examined in several different fields of study, including psychology, management, and IS. Here are the key concepts related to media choice which are not directly related to the individual3: the fit between task and media ((Daft & Lengel, 1984), (Short et al., 1976) ; the task closure (Straub & Karahanna, 1998), media richness (Daft & Lengel, 1984), (Daft & Lengel, 1986) and its critiques (Markus, 1994), (Daft et al., 1987) ; the social presence (Short et al., 1976) ; (Kraut et al., 1998), the emergent properties of media (Orlikowski, 1992), (Desanctis & Poole, 1994) and channel expansion theory (Carlson & Zmud, 1999). Media choice has also been included as an extension to the well-known Tech-nology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989). As the focus of our study is related to the choice at the individual level, we now introduce in details this specific literature.1.3. Literature directly related to the

in-dividual

In this section, we review the literature where the indi-vidual variables are directly studied.

Massey et al. suggested a broader model introducing monophasic4 and polyphasic5 temporal structure, (Massey & Montoya-Weiss, 2006). They also suggested studying differences in media use between polychronic individuals and monochronic individuals. Interestingly enough, Conte and his co-authors (Conte & Jacobs, 2003) (Conte & Gintoft, 2005) found a positive relationship between extraversion (using the “Big 5” instrument from psychology) and polychronicity, which they attributed to the “conceptual descriptions of the polychronicity con-struct.” Indeed, the literature suggests that polychronic people will focus on their relationship, whereas mono-chronics will be more task-oriented. Although Massey et al. have not tested polychronicity and media use, the likely link between extraversion and polychronicity rein-forces the relevance of studying extraversion/introversion in relation with media use.

3

As our focus is on the individual, we don't detail them. 4

Monophasic is defined as “a temporal structure […] wherein knowledge conversion participants use a single medium at a time.”

5

Polyphasic is defined as "a temporal structure […] wherein knowledge conversion participants deploy multiple media simultaneously.”

Joinson developed a conceptual model linking self-esteem, interpersonal risk (for example, asking for a pay raise) and media choice according to four scenarios (Joinson, 2004). He concluded that “low self-esteem us-ers showed a significant preference toward e-mail com-munications compared to high self-esteem users”. Brown and colleagues introduced computer anxiety and communication apprehension as an explanation of usage behaviour (Brown et al., 2004). Moreover, Opt et al. stated a strong link between introversion (using the MBTI scale) and communication apprehension (Opt & Loffredo, 2000).

Goby found that personality type is significantly corre-lated with individuals’ media choice (Goby, 2006). The study was conducted with students in Singapore and the context of media choice was linked to having a wider social circle, looking for casual work, and interactions with friends (positive or negative). The Intro-vert/Extravert dimension exerted the most significant effect on media choice. Goby introduced “personal pref-erence for online/offline media” that she measured through the choice (online/offline) of media for different tasks: “respondents were asked to choose which commu-nication media they are most comfortable with in handle [sic] each of the given situations”. Those results are in-teresting for us, although, in our opinion, they propose a partial model, where actual media use is not addressed. In addition, the population studied are students and there-fore, the managerial contributions are very limited, (e.g. (Robinson & Huefner, 1991)).

In sum, the research on the personal attributes of individ-ual and their media choice reinforces our motivation in researching individual variables explaining the use of email. Goby's study is also very encouraging regarding additional researches on personality, particularly intro-version/extraversion and media use.

2.

Theoretical development

2.1.Intrinsic Preference for a Media of

Communication (IPMC)

Based on the results of the literature reviews, we propose a new concept, IPMC, defined as the intrinsic preference of the individual towards a specific media, regardless of the context. This concept does not measure how well a person handles a medium, but simply on an intrinsic point of view, which medium he/she prefers, very much like the Jungian idea of preference.

2.2.Hypothesis

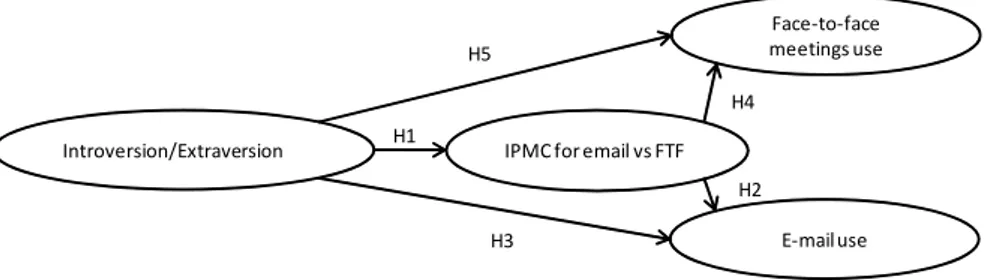

In short, we test a model (Figure 1) where extraver-sion/introversion explains media use (first, email use and second, face-to-face meeting use), moderated by the suppressor IMPC. Therefore, we test the fol-lowing hypothesises. Introversion/extraversion is a preference that appears very early in the individual’s personality (Jung, 1993) and therefore could be considered as an antecedent to media use and IPMC. Introvert people tends to be less in contact with people, therefore, as there is less interaction in e-mail exchanges than in face-to-face, we postulate: H1: Introversion has a positive influence on the intrinsic preference for email as a media of communication (IPMC for email vs. FTF)

Quite logically, we also postulate that the IPMC will have a significant impact on the overall media use. H2: the intrinsic preference for email as a media of com-munication (IPMC for email vs. FTF) has a positive in-fluence on e-mail use.

According to H1 and H2, an introvert should send more professional e-mails than an extravert.

Because for an introvert, the orientation of his energy is towards his inner world, whereas the orientation of an extravert's energy is towards the outer world, we postu-late that an extravert will overall communicate more than an introvert. Therefore,

H3: Introversion has a direct negative influence on email use.

As we identify two opposite effects in the overall model, this corresponds to a suppression model, where the effect of one relationship will suppress the effect of the other. As we measure e-mail versus face-to-face preference, we also need to look at face-to-face meeting involvement, with the following hypothesis:

H4: The intrinsic preference for email as a media of communication (IPMC for email vs. FTF) will negatively influence face-to-face meeting involvement.

As overall an introvert will tend to communicate less than an extravert, we postulate:

H5: Introversion will negatively influence face-to-face meeting involvement.

3.

Methodology

3.1.Modeling approach

Our primary goal is to test whether the new concept IPMC acts as a mediator in the relation between introver-sion/extraversion and the use of a medium. Through six different measures of media use, we will test the robust-ness of IPMC.

3.2.Data collection and sampling

Introversion/ExtraversionE-mail use IPMC for email vs FTF

Face-to-face meetings use H5 H4 H2 H3 H1

Variable Items Reference Email 1. How many professional e-mails do you send everyday? (count variable)

2. How many professional e-mails do you receive everyday? (count variable) 3. What proportion of your time do you spend reading and writing e-mails?

(ratio)

Based on (Van den Hooff, 2005) Face-to-Face 1. How many face-to-face meetings do you organize during a typical week?

(count variable)

2. How many face-to-face meetings do you participate in during a typical week? (count variable)

3. What proportion of your time do you spend in face-to-face meeting? (ratio Table 1: Measures of media use

The questionnaire was sent by email to the members of a French-speaking newsletter dedicated to the use of popu-lar spreadsheet software. As our study focuses on manag-ers, a screening question was asked prior to the question-naire: “Do you manage a team of people?” The group that received the newsletter was composed of 3,094 members. Among them, we estimated the number of managers to be 29.6 %6, which represents 914 managers. We received a total of 147 valid respondents (response rate of 16%). After deleting missing values7, we only considered 117 respondents.

3.3.Measures

3.3.1.

Extraversion/introversion

We used an online questionnaire, (Peslak, 2006). Beside asking for each respondent's his preference regarding the introversion/extraversion, the online questionnaire also asks a specific question regarding the clarity of prefer-ence (clarity index) (Briggs-Myers, 1998). This clarity index represents “how sure the respondent is that he or she prefers one dimension over the other” (McDonald & Edwards, 2007).

3.3.2.

Intrinsic Preference for a Media of

Communication (IPMC).

For this study we measured only the intrinsic preference towards two types of media, e-mail and face-to-face meeting. We asked the following question to measure PPMC: From a personal point of view, what is your

pre-ferred medium of communication (check only one box)?

This item was measured on a 6-point scale. The range was as follows: (1) Always e-mail, whatever the context, (2) Preference for e-mail, but it depends on the context, (3) Slight preference for e-mail, but it depends on the context, (4) Slight preference for face-to-face meeting, but it depends on the context, (5) Preference for face-to-face meeting, but it depends on the context, (6) Always face-to-face, whatever the context.

We tested our questionnaire with 2 pre-test samples. The first pre-test was composed of six Ph D students and the second sample was composed of fifteen managers.

3.3.3.

Media use.

Error! Reference source not found. describes the items we used to measure media use.

6

Based on a survey sent independently from the study 7

We also deleted the cases where the clarity of prefer-ence for extraversion/introversion was not high, see next paragraph.

4.

Analysis and results

4.1.Descriptive statistics

The sample size is 117 individuals, composed of 56% of introvert vs. 43% of extraverts. The average of IPMC for email vs FTF is 3.5 for the introvert and 3.2 for the extra-vert. Regarding email use, the average number of email sent and received is respectively 19.5 and 31.2 for the introvert, compared to 24.7 and 43.7 for the extravert. Finally, the average number of meeting (respectively participation and organization) is 4.6 and 2.7 for intro-verts and 5.5 and 2.8 for extraintro-verts.

4.2.Suppression models and

bootstrap-ping for the indirect effect

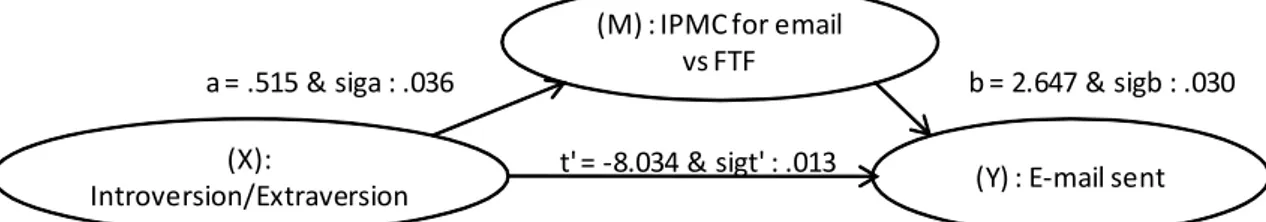

The suppression model can be represented by its direct effect (Figure 2) and its indirect effect (Figure 3). In this model, IPMC (the mediator, M) will mediate the influ-ence of introversion/extraversion (X) on media use (Y). In order to evaluate the significance of the indirect effect, we will need to use bootstrapping.

In their paper, (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) recommend boot-strapping in the presence of small to moderate samples which is our case, as well as for non-normal distribution such as the distribution of the indirect effect (MacKinnon et al., 2004). The main idea of bootstrapping is to rely on “the simulated sampling distribution to provide its own context for computing estimates of unknown population values” (Efron, 1982), (Walsh & Reznikoff, 1990). Therefore, bootstrapping follows several steps. First, using the original data, “set as a population reservoir; create a pseudo (bootstrap) sample of N persons by ran-domly sampling observations with replacement from the data set”, (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Second, for each bootstrap, estimate the coefficient (in our case, the indi-rect effect). Third, repeat the two first steps a total of J times (we choose J=1000 for our statistics). Finally, we examine the distribution of the estimates and determine the 2.5 and the 97.5 percentile of the distribution for a 95% confidence interval (2-tails).

Y : Media Use X : Introversion/Extraversion

t

Figure 2 : direct effect of introversion/extraversion on media use

Y : Media Use M : IPMC for email vs FTF

X : Introversion/Extraversion

t'

b

a

Figure 3 : mediated effect of introversion/extraversion on media use We used bootstrapping (using the software smartpls) with

a number of bootstrap resample equal to 1 000 (Stine, 1989) and the size of the sample equal to N (117). We follow the different steps proposed in the literature to test a mediation effect, (Baron & Kenny, 1986), (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) and a suppression model (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

O Specifically, we first estimate and test the ef-fect of Introversion/Extraversion (X) on e-mail sent (Y) - in case of mediation this is manda-tory, but not necessary when a suppression model is tested (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

O Second, the effect of Introversion/Extraversion (X) on IPMC (M).

O Third, the effect of IPMC (M) on e-mail sent (Y) with Introversion/Extraversion (X) on e-mail sent (Y) held constant.

O Fourth, the indirect effect: Introver-sion/Extraversion (X) => IPMC (M) => e-mail sent (Y).

O Finally, Introversion/Extraversion (X) => e-mail sent (Y) with IPMC (M) held constant.

4.3.Results

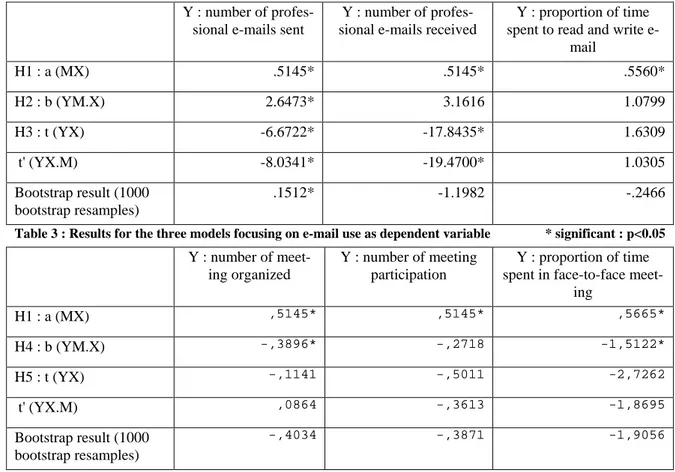

Table 3 summarizes the results of the different tests fo-cusing on e-mail use (H1 to H3), the first column of this table is represented in Figure 4 and Figure 5. More pre-cisely, Figure 4 represents the direct effect of introver-sion/extraversion on the number of professional emails sent. Introversion significantly decreases the number of professional e-mails sent (t=-6.7, p<0.05).

Figure 5 represents the general model and the results with e-mail sent as the dependent variable (Y). Introversion significantly increases the IPMC for e-mail (a=.515, p<0.05). The IPMC for email significantly increases the number of professional e-mails sent (b=2.647, p<0.05). Therefore the overall indirect effect between Introversion and number of professional e-mails sent is positive (a*b = t-t’=1.36, the result of the confidence interval for one-tail is above 0 : 0,1512 and therefore is significant). Finally, Introversion directly and significantly decreases the number of e-mails sent (t’=-8.034, p<0.05) in the model, when taking into consideration the media-tor/suppressor IPMC.

(X):

Introversion/Extraversion

(Y) : E-mail sent

t = -6.672 & sigt : .038

Figure 4 : direct effect of Extraversion/Introversion on the number of professional e-mails sent

(X):

Introversion/Extraversion

(Y) : E-mail sent

(M) : IPMC for email

vs FTF

a = .515 & siga : .036

t' = -8.034 & sigt' : .013

b = 2.647 & sigb : .030

Y : number of

profes-sional e-mails sent

Y : number of

profes-sional e-mails received

Y : proportion of time

spent to read and write

H1 : a (MX)

.5145*

.5145*

.5560*

H2 : b (YM.X)

2.6473*

3.1616

1.0799

H3 : t (YX)

-6.6722*

-17.8435*

1.6309

t' (YX.M)

-8.0341*

-19.4700*

1.0305

Bootstrap result (1000

bootstrap resamples)

.1512*

-1.1982

-.2466

Table 3 : Results for the three models focusing on e-mail use as dependent variable * significant : p<0.05

Y : number of

meet-ing organized

Y : number of meeting

participation

Y : proportion of time

spent in face-to-face

meet-ing

H1 : a (MX)

,5145* ,5145* ,5665*H4 : b (YM.X)

-,3896* -,2718 -1,5122*H5 : t (YX)

-,1141 -,5011 -2,7262t' (YX.M)

,0864 -,3613 -1,8695Bootstrap result (1000

bootstrap resamples)

-,4034 -,3871 -1,9056Table 3: results for the three models with face-to-face meetings as dependent variable * significant : p<0.05 Based on the results of Table 3, H1, H2 and H3 are all

supported for the number of professional e-mails sent. The results from the bootstrapping also support the sig-nificance of the indirect effect.

For e-mail received and proportion of time spent to read and write e-mails, H2 is not supported and the indirect effect is not significant. H3 is not supported for the pro-portion of time spent to read and write e-mails.

Regarding the results for face-to-face (Table 3, H4 and H5), we do not suspect a suppression model, therefore, we also consider the total effect : I/E -> Organization of face-to-face meeting, (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Table 3 shows that there is no significant effect of introver-sion/extraversion on the organization/ participation of meeting or on the proportion of time spent in face-to-face meetings. Therefore, there is no mediation in this case. The results also show that there is still a significant effect of Introversion/Extraversion on IPMC and also a signifi-cant effect of IPMC on the organization of face-to-face meetings. The effects were not significant between IPMC and the face-to-face meeting participation.

5.

Discussion

Based on those results, we showed that IPMC and Intro-version/Extraversion explain the variance in the number of e-mail sent, as well as the number of face-to-face meetings organized and should be considered in further research on media choice.

The non-significance of the effect of IPMC on both e-mail received and time spent to write/read e-e-mails is also interesting. Indeed, those two tasks depend less on the individual, and more on situational and institutional

con-ditions (Watson-Manheim & Belanger, 2007), in other words, “hell is other people”. Therefore, those two ele-ments are less under the control of the individual. The same explanation can be used for face-to-face meeting participation. This lack of control could explain why managers’ feels helpless regarding information overload, (Weber, 2004).

Regarding face meeting, an IPMC for

face meeting positively influences the number of face-to-face meetings organized. Surprisingly, introver-sion/extraversion did not significantly influence

face-to-face use (hypothesis 5).

Such a model has also implications regarding communi-cations across virtual organizations where the choice of the media (between e-mail and face-to-face) is not any-more a choice due to the distance, but still, some indi-viduals will prefer specific media and may behave ac-cording to this preference. This could results in a poten-tial decrease of the quality of communication or reversely in an increase of communication leading to information overload.

The fact that the respondents are active managers in-creases the validity and the managerial contribution of this study, compared to studies based on a student panel, as demonstrated in other fields, (Robinson & Huefner, 1991).

Finally, by applying very strictly the methodology for suppressor model, we provide an example of how this method may be used in IS research to dig in complex relationship between concepts. We believe that testing models at this level will improve the robustness of future research where a mediator is involved.

6.

Managerial contributions

Knowing the mechanism of the link between extraver-sion/introversion and the volume of email send, we sug-gest adapting the training of managers regarding informa-tion overload. Indeed, when talking with extraverts' peo-ple, it is better to focus on decreasing the volume of email send, linked to their need to communicate with too many people. At the contrary, with introverts, we should emphasize the fact that other media involving more face-to-face communication may be more appropriate than using the email. Being aware of those differences be-tween individuals may decrease the amount of email due to the influence of personality, mediated by the IMPC, and therefore getting out of "Hell is other people".

7.

Limitations and Future

re-search

Several limitations can be addressed to this study. First, additional measures for IPMC could strengthen this construct. For example, we could ask managers their intrinsic preference among a media repertoire instead of just two media. Second, the polyphasic use of media could also be addressed, i.e. measuring the use of several media at the same time, instead of one media at one time. Third, the choice of the dependent variables for e-mail use gave us different results and therefore can make more difficult the replication of the findings. Those results support Straub and Burton-Jones criticisms of lean meas-ures of system usage, (A. Burton-Jones & Straub, 2006).We could then complexify the capture of the media use, for example, capturing the usage of several media among a media repertoire and in a dynamic way, (Massey & Montoya-Weiss, 2006).

The low weight of the paths can be explained by the im-portance of the situational factors. Embedding those re-sults in a more complex meta-model, in order to increase the variance explained could be a future research avenue. Other individual factors could also explain media choice and should be considered. However, our goal is to focus on the influence of introversion/extraversion as well as IPMC (considered here as a suppressor variable). There is a bias in the selection of the managers as they have been contacted over the internet and by e-mails. However, regarding the fact that the large majority of managers are at ease using e-mails, we don’t think this bias is too important. The measures of media use are also self-reported and therefore are potentially biased, subject to a demand issue.

This study has been done only with a French-speaking population. It could be interesting to extend it to other culture where extraversion/introversion is potentially different.

Regarding future research and based on Massey et al., we suggest incorporating a measure of polychronicity in future research addressing personality and media use.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a new model explaining infor-mation overload and media use. This model is composed of the extraversion/introversion of the individual, a measure of the use of the media communication and

fi-nally a new construct called the intrinsic preference for a media communication (IPMC). Our results support a model where IPMC plays the role of a suppressor vari-able in the relation between Introversion/extraversion and the number of professional emails sent. Regarding the other measures of media use, our data showed only par-tial support, which suggests that managers have relatively low flexibility regarding the choice and control of their communication media. These results give some indica-tions on the reasons of the information overload among the managers, related to misuse of media. Indeed, know-ing the influence of personality on media choice will help managers to get out of "hell is other people". Finally, more research focusing at the individual level is needed in order to explain media choice in more complex set-tings such as media repertoire, dynamic use of media over time, and in-depth analysis of relevant situations.

Bibliography

Burton-Jones A. and Straub D. (2006), « Reconceptualiz-ing System Usage: An Approach and Empirical Test » Information Systems Research, 17(3), pp. 228-246.

Baron R. M. and Kenny D. A. (1986), « The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychologi-cal Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and StatistiPsychologi-cal Considerations », Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Boukef C. and Kalika M. (2006), « La théorie du mille-feuille, le rôle du contexte », Systèmes d'Information

et Management, 11(4),

Briggs-Myers I. (1998), Introduction to type. CPP. Brown S. A., Fuller R. M. and Vician C. (2004), « Who's

afraid of the virtual world? Anxiety and Computer-Mediated Communication », Journal of the

Associa-tion for InformaAssocia-tion Systems, 5(2), pp. 79-107.

Carlson J. R. and Zmud R. W. (1999), « Channel Expan-sion Theory and the Experiential Nature of Media Richness Perceptions », Academy of Management

Journal, 42(2), pp. 153-170.

Conte J. M. and Gintoft J. N. (2005), « Polychronicity, Big Five Personality Dimensions, and Sales Perform-ance », Human PerformPerform-ance, 18(4), pp. 427-444. Conte J. M. and Jacobs R. R. (2003), « Validity Evidence

Linking Polychronicity and Big Five Personality Di-mensions to Absence, Lateness, and Supervisory Per-formance Ratings », Human PerPer-formance, 16(2), pp. 107-129.

Daft R. L. and Lengel R. H. (1984), « Information rich-ness: A new approach to managerial information processing and organization design », In Research in

Organizational Behavior, (Cummings LL and Staw

BM, Eds), pp 191-233, JAI Press, Homewood, IL. Daft R. L. and Lengel R. H. (1986), Organizational

in-formation requirements, media richness and structural design », Management Science, 32, pp. 554-571. Daft R. L., Lengel R. H. and Trevino L. K. (1987),

« Message equivocality, media selection, and man-ager performance: Implication for information sys-tems », MIS Quarterly, 11(3), pp. 355-366.

Davis F. D. (1989), « Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology », MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 318.

Desanctis G. and Poole M. S. (1994), « Capturing the Complexity in Advanced Technology Use - Adaptive Structuration Theory », Organization Science, 5(2), pp. 121-147.

Efron B. (1982), « The jackknife, the bootstrap and othere resampling plans », Society for industrial and

Applied Mathematics CBMS National Science Foun-dation Monograph, 38.

Furnham A. (1996), « The big five versus the big four: The relationship between the Myers-Briggs Type In-dicator (MBTI) and NEO-PI five factor model of per-sonality », Perper-sonality and Individual Differences, 21(2), pp. 303-307.

Gardner W. L. M., Mark J. (1996), « Using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to Study Managers: A Litera-ture Review and Research Agenda », Journal of

Management, 22, pp. 45-83.

Goby V. P. (2006), « Personality and Online/Offline Choices: MBTI Profiles and Favored Communication Modes in a Singapore Study », CyberPsychology &

Behavior, 9(1), pp. 5-13.

Joinson A. N. (2004), « Self-Esteem, Interpersonal Risk, and Preference for E-Mail to Face-To-Face Commu-nication », CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(4), pp. 472-478.

Jung C.-G. (1993), Psychological Type. Georg Editeur, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kalika M., Boukef C. N. and Isaac H. (2008), « An Em-pirical Investigation of E-mail Use versus Face-to-Face Meetings: Integrating the Napoleon Effect Per-spective », Communications of the Association for

In-formations Systems, 22.

Kalika M., Isaac H. and Campoy E. (2007), « Surcharge informationnelle, urgence et tic; l'effet temporel des technologies de l'information », Management &

Ave-nir, 13, pp. 149-168.

Kraut R. E., Rice R. E., Cool C. and Fish R. S. (1998), « Varieties of social influence: The role of utility and norms in the success of a new communication me-dium », Organization Science, 9(4), pp. 437-453. Mackinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M. and Williams J.

(2004), « Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect »,

Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), pp. 99-128.

Markus M. L. (1994), « Electronic Mail as the Medium of Managerial Choice », Organization Science, 5(4), pp. 502-527.

Massey A. P. and Montoya-Weiss M. M. (2006), « Un-raveling the temporal fabric of knowledge conver-sion: a model of media selection and use », MIS

Quarterly, 30(1), pp. 99-114.

Mcdonald S. and Edwards H. M. (2007), « Who Should Test Whom? », Communications of the ACM, 50(1), pp. 67-71.

Mcelroy J. C., Hendrickson A. R., Townsend A. M. and Demarie S. M. (2007), « Dispositional factors in internet use: personality versus cognitive style », MIS

Quarterly, 31(4), pp. 809-820.

Opt S. K. and Loffredo D. A. (2000), « Rethinking Com-munication Apprehension: A Myers-Briggs Perspec-tive », Journal of Psychology, 134(5), 556.

Orlikowski W. J. (1992), « The Duality of Technology - Rethinking the Concept of Technology in Organiza-tions », Organization Science, 3(3), pp. 398-427. Peslak A. R. (2006) « The impact of personality on

in-formation technology team projects », Proceedings of

the 2006 ACM SIGMIS CPR conference on computer personnel research: Forty four years of computer personnel research: achievements, challenges & the future, ACM Press, Claremont, California, USA

Preacher K., J. and Hayes A., F. (2004), « SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models », Behavior Research

Meth-ods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717.

Robinson P. B. and Huefner J. C. (1991), « Entrepreneu-rial research on student subjects does not generalize to real world entrepreneurs », Journal of Small

Busi-ness Management, 29(2), pp. 42-50.

Short S., Williams E. and Bhristie B. (1976), The Social

Psychology of Telecommunications. McGraw-Hill,

London, England.

Shrout P. E. and Bolger N. (2002), « Mediation in ex-perimental and nonexex-perimental studies: New proce-dures and recommendations », Psychological

Meth-ods 7(4), pp. 422-445.

Stine R. (1989), « An introduction to Bootstrap Meth-ods », Sociological methMeth-ods and research 18(2&3), pp. 243-291.

Straub D. W. and Karahanna E. (1998), « Knowledge Worker Communications and Recipient Availability: Toward a Task Closure Explanation of Media Choice », Organization Science, 9(2), pp. 160-175. Van Den Hooff B. (2005), « A learning process in email

use - a longitudinal case study of the interaction be-tween organization and technology », Behaviour &

Information Technology, 24(2), pp. 131-145.

Walsh J. F. and Reznikoff M. (1990), « Bootstrapping: a tool for clinical research », Journal of Clinical

Psy-chology, 46(6), pp. 928-930.

Watson-Manheim M. B. and Belanger F. (2007), « Com-munication media repertoires: dealing with the multi-plicity of media choices », MIS Quarterly, 31(2), pp. 267-293.

Weber R. (2004) « The Grim Reaper: The Curse of E-Mail », MIS Quarterly, pp. i-xiii.