HAL Id: dumas-01389459

https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01389459

Submitted on 28 Oct 2016

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

The skull vibration induced nystagmus test in

cochlear-implanted patients: a prospective study in 51

patients

Jennifer Petrossi

To cite this version:

Jennifer Petrossi. The skull vibration induced nystagmus test in cochlear-implanted patients: a prospective study in 51 patients. Human health and pathology. 2016. �dumas-01389459�

AVERTISSEMENT

Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le

jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la

communauté universitaire élargie.

Il n’a pas été réévalué depuis la date de soutenance.

Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci

implique une obligation de citation et de référencement

lors de l’utilisation de ce document.

D’autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite

encourt une poursuite pénale.

Contact au SID de Grenoble :

bump-theses@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

LIENS

LIENS

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 122. 4

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 335.2- L 335.10

http://www.cfcopies.com/juridique/droit-auteur

1

UNIVERSITE GRENOBLE ALPES

FACULTE DE MEDECINE DE GRENOBLE

Année : 2016

Intérêt du Test Vibratoire Osseux (TVO) chez les patients

implantés cochléaires: étude prospective chez 51 patients

THESE

PRESENTEE POUR L’OBTENTION DU DOCTORAT EN MEDECINE

DIPLÔME D’ETAT

Jennifer PETROSSI

THESE SOUTENUE PUBLIQUEMENT A LA FACULTE DE MEDECINE DE GRENOBLE*

Le 20 Octobre 2016

DEVANT LE JURY COMPOSE DE

Président du jury : Monsieur le Professeur Christian Adrien RIGHINI

Directeur de thèse : Monsieur le Professeur Sébastien SCHMERBER

Membres : Monsieur le Professeur Hung THAI VAN Monsieur le Docteur Georges DUMAS

*La Faculté de Médecine de Grenoble n’entend donner aucune approbation ni improbation aux opinions émises dans les thèses ; ces opinions sont considérées comme propres à leurs auteurs.

2

Doyen de la Faculté : M. le Pr. Jean Paul ROMANET

Année 2016-2017

ENSEIGNANTS A L’UFR DE MEDECINE

PU-PH ALBALADEJO Pierre Anesthésiologie réanimation PU-PH APTEL Florent Ophtalmologie

PU-PH ARVIEUX-BARTHELEMY Catherine Chirurgie générale PU-PH BALOSSO Jacques Radiothérapie

PU-PH BARONE-ROCHETTE Gilles Cardiologie PU-PH BARRET Luc Médecine légale et droit de la santé PU-PH BAYAT Sam Physiologie

PU-PH BENHAMOU Pierre Yves Endocrinologie, diabète et maladies métaboliques PU-PH BERGER François Biologie cellulaire

MCU-PH BIDART-COUTTON Marie Biologie cellulaire MCU-PH BOISSET Sandrine Agents infectieux

PU-PH BONAZ Bruno Gastro-entérologie, hépatologie, addictologie PU-PH BONNETERRE Vincent Médecine et santé au travail

PU-PH BOREL Anne-Laure Endocrinologie, diabète et maladies métaboliques

PU-PH BOSSON Jean-Luc Biostatistiques, informatique médicale et technologies de communication MCU-PH BOTTARI Serge Biologie cellulaire

PU-PH BOUGEROL Thierry Psychiatrie d'adultes PU-PH BOUILLET Laurence Médecine interne PU-PH BOUZAT Pierre Réanimation

PU-PH BRAMBILLA Christian Pneumologie

MCU-PH BRENIER-PINCHART Marie Pierre Parasitologie et mycologie PU-PH BRICAULT Ivan Radiologie et imagerie médicale

PU-PH BRICHON Pierre-Yves Chirurgie thoracique et cardio- vasculaire MCU-PH BRIOT Raphaël Thérapeutique, médecine d'urgence

MCU-PH BROUILLET Sophie Biologie et médecine du développement et de la reproduction PU-PH CAHN Jean-Yves Hématologie

MCU-PH CALLANAN-WILSON Mary Hématologie, transfusion PU-PH CARPENTIER Françoise Thérapeutique, médecine d'urgence PU-PH CARPENTIER Patrick Chirurgie vasculaire, médecine vasculaire PU-PH CESBRON Jean-Yves Immunologie

PU-PH CHABARDES Stephan Neurochirurgie

PU-PH CHABRE Olivier Endocrinologie, diabète et maladies métaboliques PH CHAFFANJON Philippe Anatomie

PUPU-PH CHARLES Julie Dermatologie

PU-PH CHAVANON Olivier Chirurgie thoracique et cardio- vasculaire PU-PH CHIQUET Christophe Ophtalmologie

PU-PH CINQUIN Philippe Biostatistiques, informatique médicale et technologies de communication PU-PH COHEN Olivier Biostatistiques, informatique médicale et technologies de communication

3

PU-PH COUTURIER Pascal Gériatrie et biologie du vieillissement

PU-PH CRACOWSKI Jean-Luc Pharmacologie fondamentale, pharmacologie clinique PU-PH CURE Hervé Oncologie

PU-PH DEBILLON Thierry Pédiatrie

PU-PH DECAENS Thomas Gastro-entérologie, Hépatologie PU-PH DEMATTEIS Maurice Addictologie

MCU-PH DERANSART Colin Physiologie PU-PH DESCOTES Jean-Luc Urologie MCU-PH DETANTE Olivier Neurologie

MCU-PH DIETERICH Klaus Génétique et procréation MCU-PH DOUTRELEAU Stéphane Physiologie MCU-PH DUMESTRE-PERARD Chantal Immunologie PU-PH EPAULARD Olivier Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales PU-PH ESTEVE François Biophysique et médecine nucléaire MCU-PH EYSSERIC Hélène Médecine légale et droit de la santé PU-PH FAGRET Daniel Biophysique et médecine nucléaire PU-PH FAUCHERON Jean-Luc Chirurgie générale MCU-PH FAURE Julien Biochimie et biologie moléculaire PU-PH FERRETTI Gilbert Radiologie et imagerie médicale PU-PH FEUERSTEIN Claude Physiologie

PU-PH FONTAINE Éric Nutrition

PU-PH FRANCOIS Patrice Epidémiologie, économie de la santé et prévention MCU-MG GABOREAU Yoann Médecine Générale

PU-PH GARBAN Frédéric Hématologie, transfusion PU-PH GAUDIN Philippe Rhumatologie

PU-PH GAVAZZI Gaétan Gériatrie et biologie du vieillissement PU-PH GAY Emmanuel Neurochirurgie

MCU-PH GILLOIS Pierre Biostatistiques, informatique médicale et technologies de communication MCU-PH GRAND Sylvie Radiologie et imagerie médicale

PU-PH GRIFFET Jacques Chirurgie infantile PU-PH GUEBRE-EGZIABHER Fitsum Néphrologie

MCU-PH GUZUN Rita Endocrinologie, diabétologie, nutrition, éducation thérapeutique PU-PH HAINAUT Pierre Biochimie, biologie moléculaire

PU-PH HENNEBICQ Sylviane Génétique et procréation PU-PH HOFFMANN Pascale Gynécologie obstétrique PU-PH HOMMEL Marc Neurologie

PU-MG IMBERT Patrick Médecine Générale PU-PH JOUK Pierre-Simon Génétique PU-PH JUVIN Robert Rhumatologie PU-PH KAHANE Philippe Physiologie

4

PU-PH KRACK Paul Neurologie

PU-PH KRAINIK Alexandre Radiologie et imagerie médicale PU-PH LABARERE José Epidémiologie ; Eco. de la Santé MCU-PH LANDELLE Caroline Bactériologie - virologie MCU-PH LAPORTE François Biochimie et biologie moléculaire MCU-PH LARDY Bernard Biochimie et biologie moléculaire MCU-PH LARRAT Sylvie Bactériologie, virologie

MCU - PH LE GOUËLLEC Audrey Biochimie et biologie moléculaire PU-PH LECCIA Marie-Thérèse Dermato-vénéréologie

PU-PH LEROUX Dominique Génétique

PU-PH LEROY Vincent Gastro-entérologie, hépatologie, addictologie PU-PH LEVY Patrick Physiologie

MCU-PH LONG Jean-Alexandre Urologie PU-PH MAGNE Jean-Luc Chirurgie vasculaire

MCU-PH MAIGNAN Maxime Thérapeutique, médecine d'urgence PU-PH MAITRE Anne Médecine et santé au travail

MCU-PH MALLARET Marie-Reine Epidémiologie, économie de la santé et prévention MCU-PH MARLU Raphaël Hématologie, transfusion

MCU-PH MAUBON Danièle Parasitologie et mycologie PU-PH MAURIN Max Bactériologie - virologie MCU-PH MC LEER Anne Cytologie et histologie

PU-PH MERLOZ Philippe Chirurgie orthopédique et traumatologie PU-PH MORAND Patrice Bactériologie - virologie

PU-PH MOREAU-GAUDRY Alexandre Biostatistiques, informatique médicale et technologies de communication PU-PH MORO Elena Neurologie

PU-PH MORO-SIBILOT Denis Pneumologie PU-PH MOUSSEAU Mireille Cancérologie

PU-PH MOUTET François Chirurgie plastique, reconstructrice et esthétique ; brûlologie MCU-PH PACLET Marie-Hélène Biochimie et biologie moléculaire

PU-PH PALOMBI Olivier Anatomie PU-PH PARK Sophie Hémato - transfusion PU-PH PASSAGGIA Jean-Guy Anatomie

PU-PH PAYEN DE LA GARANDERIE Jean-François Anesthésiologie réanimation MCU-PH PAYSANT François Médecine légale et droit de la santé

MCU-PH PELLETIER Laurent Biologie cellulaire PU-PH PELLOUX Hervé Parasitologie et mycologie PU-PH PEPIN Jean-Louis Physiologie

PU-PH PERENNOU Dominique Médecine physique et de réadaptation PU-PH PERNOD Gilles Médecine vasculaire

PU-PH PIOLAT Christian Chirurgie infantile PU-PH PISON Christophe Pneumologie PU-PH PLANTAZ Dominique Pédiatrie PU-PH POIGNARD Pascal Virologie

5

PU-PH POLACK Benoît Hématologie

PU-PH POLOSAN Mircea Psychiatrie d'adultes PU-PH PONS Jean-Claude Gynécologie obstétrique PU-PH RAMBEAUD Jacques Urologie

PU-PH RAY Pierre Biologie et médecine du développement et de la reproduction PU-PH REYT Émile Oto-rhino-laryngologie

PU-PH RIGHINI Christian Oto-rhino-laryngologie PU-PH ROMANET Jean Paul Ophtalmologie PU-PH ROSTAING Lionel Néphrologie

MCU-PH ROUSTIT Matthieu Pharmacologie fondamentale, pharmaco clinique, addictologie MCU-PH ROUX-BUISSON Nathalie Biochimie, toxicologie et pharmacologie

MCU-PH RUBIO Amandine Pédiatrie

PU-PH SARAGAGLIA Dominique Chirurgie orthopédique et traumatologie MCU-PH SATRE Véronique Génétique

PU-PH SAUDOU Frédéric Biologie Cellulaire

PU-PH SCHMERBER Sébastien Oto-rhino-laryngologie PU-PH SCHWEBEL-CANALI Carole Réanimation médicale PU-PH SCOLAN Virginie Médecine légale et droit de la santé

MCU-PH SEIGNEURIN Arnaud Epidémiologie, économie de la santé et prévention PU-PH STAHL Jean-Paul Maladies infectieuses, maladies tropicales

PU-PH STANKE Françoise Pharmacologie fondamentale MCU-PH STASIA Marie-José Biochimie et biologie moléculaire PU-PH STURM Nathalie Anatomie et cytologie pathologiques PU-PH TAMISIER Renaud Physiologie

PU-PH TERZI Nicolas Réanimation

MCU-PH TOFFART Anne-Claire Pneumologie

PU-PH TONETTI Jérôme Chirurgie orthopédique et traumatologie PU-PH TOUSSAINT Bertrand Biochimie et biologie moléculaire PU-PH VANZETTO Gérald Cardiologie

PU-PH VUILLEZ Jean-Philippe Biophysique et médecine nucléaire PU-PH WEIL Georges Epidémiologie, économie de la santé et prévention PU-PH ZAOUI Philippe Néphrologie

PU-PH ZARSKI Jean-Pierre Gastro-entérologie, hépatologie, addictologie

PU-PH : Professeur des Universités et Praticiens Hospitaliers

MCU-PH : Maître de Conférences des Universités et Praticiens Hospitaliers PU-MG : Professeur des Universités de Médecine Générale

6

Chers Maîtres :

Monsieur le Professeur Christian Adrien RIGHINI, président du jury :

Tout d’abord merci d’avoir accepté d’être le président du jury de ma thèse. Je vous remercie également de l’enseignement que vous m’avez apporté pendant ces cinq années d’internat mais aussi lorsque je suis passée externe dans le service. Je l’avoue cela m’a poussé à choisir cette spécialité. Vos compétences chirurgicales et vos connaissances théoriques ont été importantes pendant ma formation même si je n’ai pas choisi la voie chirurgicale….

Monsieur le Professeur Sébastien SCHMERBER, directeur de thèse :

Je vous remercie de m’avoir confié ce sujet de travail pour ma thèse. Je vous remercie également de l’apport de vos connaissances dans votre domaine et de me les avoir transmises avec vigueur. Votre sens de la perfection et votre finesse dans l’otologie ont été un exemple pendant ma formation.

Monsieur le Professeur Hung THAI VAN, membre du jury :

Je vous remercie d’avoir accepté d’être membre du jury pour ma thèse. Vous me faîtes également l’honneur de m’accepter bientôt comme assistante dans votre service afin que je puisse poursuivre ma formation dans le domaine des explorations fonctionnelles. Cela est essentiel pour moi de pouvoir apprendre dans un service comme le vôtre, dédié uniquement à ce domaine de notre spécialité. Pour cela je vous en suis infiniment reconnaissante.

Monsieur le Docteur Georges DUMAS, membre du jury :

Je vous remercie d’accepter de juger mon travail d’autant plus que je sais qu’il s’agit d’un sujet qui vous est cher. Pendant mon internat, j’ai été « contaminée » par votre engagement dans la vestibulométrie. Je vous remercie de m’avoir communiqué cette passion et d’avoir pu

7

bénéficier de vos si grandes compétences dans ce domaine. J’espère que ce travail de thèse ne sera pas trop décevant sur le Test Vibratoire Osseux que vous ne cessez de défendre.

Monsieur le Professeur Emile REYT :

Je tiens à vous remercier particulièrement pour vos connaissances aussi bien sur le plan théorique que dans le domaine chirurgical. Votre calme mais aussi votre bonne humeur et votre contact avec les patients ont été essentiels pendant mon internat et cela continuera à me suivre tout au long de mon exercice médical.

8

Table des matières

I-PREAMBULE………p 9

II- ARTICLE

1- Introduction……… p 13 2- Materials and Methods……… ..p 15 - Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test………...p 16 - Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential Test………..p 16 - Caloric Testing………...p 17 - Questionnaires………....p 17 - Statistical analysis………..p 18 3- Results……….p19

- Overall results………p 19 - Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test………..p 22 - Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential Test……….p 22 - Caloric Testing………...p 23 - SVINT versus a strategy combining VEMP and Caloric Testing………….p 24 - Questionnaires………...p 25 - Hearing preservation……….p 26 - Rate of dislocation……….p 27 4- Discussion………p28 5- Conclusion……… ..p 31 6- References ………..p 33 III-SERMENT D’HIPPOCRATE……….p 36 IV-REMERCIEMENTS……….p 37 V- ABSTRACT………p 41

9

Préambule

La plupart des surdités totales, profondes ou sévères, quelles qu'en soient l'origine et

l'ancienneté, peuvent être maintenant réhabilitées par l'implantation cochléaire. La mise en

place chirurgicale de l'implant électronique nécessite une intervention simple.

Depuis les années quatre-vingt, l'efficacité et l'innocuité de l'implant cochléaire sont devenues

évidentes et ses indications ont été largement prônées chez les jeunes enfants, d’autant que

peu à peu l'ensemble du corps médical s’est accordé pour reconnaitre la notion d'urgence quand il s'agit d'implanter un enfant sourd congénital.

Deux règles sont importantes dans l’implantation cochléaire : la préservation cochléaire et la

préservation vestibulaire.

Sur le plan vestibulaire, des modifications suite à la pose de l’implant cochléaire sont

maintenant reconnues. Cela peut être lié à plusieurs mécanismes : une cause traumatique,

l’aspiration de périlymphe, la formation d’un hydrops endolymphatique, la survenue d’une labyrinthite par réaction à un « corps étranger », l’effet de la stimulation électrique.

Dans la vie quotidienne, notre système vestibulaire est soumis à des stimulations

physiologiques de l’ordre de 0,05 à 10 Hz. Von Bekesy rapportait dès 1935 que des vibrations appliquées au crâne étaient susceptibles de déclencher des réflexes vestibulaires et des

illusions de mouvement chez l’homme. Lücke en 1973 avait constaté accidentellement que des vibrations de l’ordre de 100 Hz appliquées au visage entraînaient chez un patient vestibulo-lésé unilatéralement un nystagmus. Ces données reprises par Hamann en 1999 (dans

une série de schwannomes du VIII explorés en pré opératoire) ont amené initialement cet

10

du test calorique qui interroge séparément le canal semi-circulaire latéral de chaque oreille à

basses fréquences.

Le Test Vibratoire Osseux (TVO) a montré que le vestibule est excitable à de hautes

fréquences. Celles-ci étaient jusque-là négligées et non exploitées par des tests classiques qui

ne faisaient appel qu’aux basses fréquences en clinique ; le TVO a permis d’explorer de façon simple ces fréquences jusque-là ignorées. Ce test complète le calorique et le Head Shaking

Test (HST) dans l’analyse multi fréquentielle du vestibule (Figure 1).

Figure 1 : Spectre fréquentiel utilisé en clinique pour stimuler les structures vestibulaires.

Les stimulations vestibulaires qui étaient pendant de très nombreuses années utilisées en

clinique n’étudiaient que l’épreuve rotatoire sinusoïdale amortie (qui utilise des fréquences de

l’ordre de 0,01 à 0,05 Hz) et le calorique qui correspond à une stimulation de l’ordre de 0,003 Hz. Par ailleurs des patients présentant d’apparentes et fausses aréflexies vestibulaires

11

bilatérales diagnostiquées sur l’étude des seules basses fréquences (réponses abolies aux

épreuves sinusoïdale et calorique) ont montré un nystagmus induit par le TVO à 100 Hz

témoignant d’une asymétrie vestibulaire aux hautes fréquences et donc d’une conservation partielle de la fonction vestibulaire. De tels patients se comportent comme des filtres

passe-haut et autorisent un meilleur pronostic sur le plan de la rééducation dans ces cas de pseudo

aréflexie bilatérale.

Le TVO est un test robuste, simple, non invasif, qui se comporte comme un test de Weber

vestibulaire haute fréquence et permet au fauteuil de consultation de révéler instantanément

une asymétrie vestibulaire sous la forme d’un nystagmus induit par les vibrations (Figures 2 à 4).

Figure 2 : Absence de lésion : pas de nystagmus induit par les vibrations.

Symétrie vestibulaire

30 Hz

60 Hz

12

Figure 3 : Déficit vestibulaire partiel : nystagmus induit par les vibrations.

Figure 4 : Déficit vestibulaire total : nystagmus induit par les vibrations qui bat du côté sain.

Asymétrie vestibulaire :

déficit partiel

30 Hz

60 Hz

100 Hz

Asymétrie vestibulaire :

déficit total

30 Hz

60 Hz

100 Hz

13

“The skull vibration induced nystagmus test in

cochlear-implanted patients: a prospective study in 51 patients”

INTRODUCTIONCochlear implant is a major advance for patients with profound deafness but vestibular

disorders are possible postoperatively. The vestibular system is sensitive to movements at

frequencies ranging from 0.05 to 10 Hz in daily life. The interest of the vibratory stimuli of

the forehead and mastoids has proved to detect vestibular disorders [1-3]but few studies have

concerned the interest of this test in cochlear implantation. These vibratory stimuli constitute

a non-invasive intervention, which is easy to implement as a bed side test and detect a

vestibular asymmetry in physiological extra frequencies.

The investigations of vestibular disorders should be completed with a multifrequency analysis

since the previous tests are not always positive at the same time [4]. With skull

vibration-induced nystagmus test (SVINT), no contraindication is reported, such as tympanic

perforation or external meatus malformation for caloric testing (CT), and cervical or vascular

disease for head shaking testing (HST).

Dumas et al. reported that SVINT and CT correlated in 78 % of patients with partial unilateral

vestibular lesion [4]. For Xie et al., the sensitivity and the specificity of SVINT were 81% and

100% in the diagnosis of the unilateral vestibular disorder respectively while the sensitivity

and the specificity of CT were 91% and 100% respectively [5].

The more severe the injury, the more the tests (SVINT and CT) are concordant [6]. In total

unilateral vestibular injuries, the nystagmus still beats towards the healthy side but, in partial

14

By comparison with the HST, SVINT has a better sensitivity in partial vestibular lesions

especially if the canal paresis value on CT is greater than 50% [7]. Vibration induced

nystagmus (VIN) is more likely to be revealed with an increasing canal paresis value on CT

[7].

According to Hamann et al., this test shows the participation of the horizontal canal [1]. Other

studies found a correlation between SVINT and vestibular evoked myogenic potential

(VEMP) testing, in other words SVINT studies the dysfunction in the saccule [2].

In cochlear implantation, divergent data were reported on the occurrence of dizziness

following this surgery: Krause et al. found a significant risk factor for horizontal canal

impairment and for saccular function in the implanted ear [8]. Saccular impairment was found

in several studies [9, 10]. This could be explained by the anatomical proximity of the saccule

to the cochlea. Dizziness may be also due to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo [11] or to

hydrops conditions [12]. Histopathological studies [13] on temporal bones highlighted

degenerative modifications in the proximity of the active electrode.

Surgical technique is also essential. Todt et al. suggested that a round window approach for

electrode insertion should be preferred to decrease vestibular lesion [14]. Coordes et al found

the same result [15].

Regarding vestibular function, few data are available regarding tests with high frequencies

such as SVINT. Jutila et al. studied horizontal high frequency vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR)

with the motorized head impulse rotator in a cochlear implantation surgery but there was no

significant change in horizontal VOR gain [16].

The aim was to evaluate the benefit of the SVINT to diagnose vestibular disorders in cochlear

15

questionnaires (Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit, Glasgow Benefit Inventory,

Dizziness Handicap Inventory).

The link between the occurrence of dizziness with the rate of hearing preservation and of

dislocation was also explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All consecutive patients, over 10 years old, which would benefit from a cochlear implantation

surgery, were prospectively enrolled in the study, in the French Alps cochlear implant center

between January 2014 and January 2016, regardless of sex and pathology.

Patients with inner ear malformations or vertigo when performing tests were excluded.

The cause of deafness could either be congenital or acquired (Table 1). The indication of a

cochlear implantation surgery was a severe to profound bilateral sensorineural deafness, with

a discrimination rate less than or equal of 50 % to 60 decibels in free field with adapted

hearing aids.

Nine patients were implanted on both sides sequentially.

A petrous bone computed tomography-scan and magnetic resonance imaging of the inner ear

were performed, and a psychological assessment was conducted before surgery.

The majority of patients were ambulatory. Where that was not possible (health problems,

home a long distance from the hospital, no next of kin, under-age patients), they were

hospitalized overnight.

The surgery consisted of the insertion of electrodes through a round window niche.

Vestibular function was studied with SVINT, VEMP and CT three to six months prior to

surgery, and between one and three months following the procedure. All testing was done by

16

performed all three tests for the same patient. The functional outcome of cochlear implant was

studied with speech audiogram (score between 0 and 30% of success rate was a poor result;

score between 31 and 50% was an average result; score between 51 and 100% was a good

result). The speech audiogram was performed in free field, without lip reading, with a

monosyllabic list, at 60 dB using only cochlear implant.

Following surgery, patients answered three questionnaires to evaluate cochlear

implant-related dizziness.

For SVINT, the vibration was applied to the two mastoids and to the forehead with a

cylindrical contact surface of 2 cm diameter, during 10 seconds. The equipment was a V-VIB

3F-stimulator (Synapsis, Marseille, France) which can be used at three frequencies

(30-60-100 Hz). Patients were placed in seated position and nystagmus was observed with a

videonystagmoscope. The SVINT was considered positive when stimulation produced a

reproducible and sustained nystagmus which did not change direction. This nystagmus

stopped with cessation of stimulation and her slow-phase velocity was more than 2 degrees

per second.

VEMP studied the sacculus function with an active electrode placed in the lower two thirds of

the sternocleidomastoid muscle, on each side. It was cervical VEMP. The ground electrode

was placed on the middle part of the forehead and the reference electrode was located over the

upper sternum. The measurements were performed using Neuro-Audio.NET software, of

Neurosoft Society (Ivanovo, Russia). The stimulus, via headphone, was 500 Hz with tone

bursts and intensity between 90 and 110 dB with 100 stimuli in all. During the stimulation,

patients raised and turned their head sideways by 45 degrees, so contralateral to stimulation.

17

two waves at 13 and 23 milliseconds. If the amplitude of these waves was less than 50% of

the amplitude of the other side, this corresponded to a unilateral weakness.

Caloric testing studied horizontal canal function. In our study, it was considered as a

reference for the diagnosis of vestibular disorder. This test was conducted with Synapsis

3.4.0.30 equipment (Synapsis, Marseille, France). Patients were lying down, with head raised

at 30 degrees to be parallel to the horizontal canal, with both eyes open, in the dark. We

irrigated each ear canal with water at 30° and 44°, for 20 seconds, and spontaneous nystagmus

was recorded for 60 to 80 seconds after irrigation with a videonystagmoscope. Each side was

compared according to the intensity of nystagmus at its highest speed. There were three levels

of vestibular lesion: if canal paresis (CP) value was between 20 % and 40 %, it was

considered a small lesion; if CP value was between 40% and 80 %, it was considered a

moderate lesion; and if CP value was 80% and more, it was considered a profound lesion [5].

Patients filled out three questionnaires. First, the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit

(APHAB) questionnaire accurately looks at inconveniences encountered by patients in

differents situations of daily life, with 24 items. Secondly, after surgery, patients filled out the

Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI) developed by Robinson et al[17]. GBI measures changes in

general and social life, and in health status, as a result of otorhinolaryngological surgery, with

18 items. The score can range from -100 (maximum inconvenience) to 0 (no benefit) to + 100

(maximum benefit). The last questionnaire submitted was the Dizziness Handicap Inventory

(DHI) which helps to reach a first diagnosis for patients experiencing dizziness balance

disorders, with 25 items. There were three levels according to the score: 0 to 30, little or no

discomfort, 31 to 70, regular discomfort, and 71 to 100, significant discomfort. All

18

with cover letter. If there was no reply, a reminder was sent by mail with the same covering

letter.

To explore the link between occurrence of vestibular disorders and the rate of hearing

preservation, we used hearing preservation classification system of Skarzynski et al [18]. We

calculated the score of hearing preservation by comparing audiograms before and after

surgery without hearing aid or cochlear implant. This helped to identify residual hearing.

Hearing preservation (HP) was defined by a hearing score greater than 75%, and a partial HP

by a hearing score between 25 % and 75 %. If this score was less than 25%, minimal HP was

acknowledged.

We explored the link between occurring dizziness and dislocation of electrodes in the

vestibular ramp. After surgery, patients underwent a CT-scan with volumetric acquisition

(Cone Beam). This tracked the electrodes of the first basal turn of the cochlea to the apex and

enabled to observe if the electrodes passed in the vestibular ramp door (dislocation). We used

classification of cochlear trauma described by Eshraghi et al [19].

For statistical analysis, the general characteristics of the patients and clinical care conditions

were described. Then, the diagnostic performance of the SVINT was assessed at pre- and

post-operatively. Sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive and negative predictive values

(PPV, NPV) and the likelihood ratios of the SVINT were calculated, with their 95 %

confidence intervals. The link between rates of vestibular disorders and hearing preservation

on the one hand, and between vestibular disorders and the rate of dislocation on the other

hand, were studied using the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. All analyses were performed

with STATA 12 software (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College

19

RESULTS

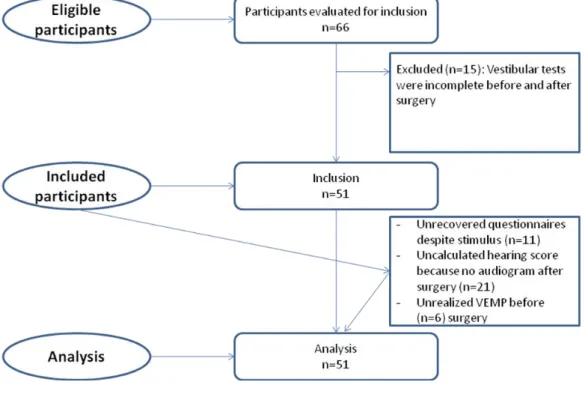

Fifty one patients were included (Fig 1). The average age of implantation was 55 years. There

were 26 (51%) male and 25 (49%) female, and 3 minor patients.

Figure 1: Flowchart.

Nine (17%) patients had already had a cochlear implant on one side for several years. The left

side was implanted in 34 cases (58%) and the right side in 25 cases (42%).

The condition causing hearing loss was mostly progressive deafness (26 (51%) patients).

There were also congenital disease (9 (17%) patients) and sudden deafness (6 (12%) patients)

20

Group : disease of hearing loss

Number (%) Male (%) Female (%) Implanted Side Left (L)=N Right(R)=N Progressive deafness 26 (51) 13 (50) 13 (50) L=19 R=11 Congenital 9 (17) 2 (22) 7 (78) L=7 R=5 Sudden deafness 6 (12) 5 (83) 1 (17) L=4 R=2 Otitis 1 (2) 1 (100) 0 L=0 R=1 Meningitis 2 (4) 1 (50) 1 (50) L=1 R=1 Trauma 1 (2) 1 (100) 0 L=0 R=1 Otosclerosis 4 (8) 1 (25) 3 (75) L=3 R=2 Drug-induced 1 (2) 1 (100) 0 L=0 R=1 Hydrops 1 (2) 1 (100) 0 L=0 R=1 Total 51 (100%) 26 (51%) 25 (49%) 34 (58%) 25 (42%) Table 1: Cause of deafness; Nine patients were implanted bilaterally (17%).

Regarding cochlear implant, there were 23 (45%) Cochlear Nucleus (Toulouse, France), 21

(41%) MED-EL (Sophia Antipolis, France) and 7 (14%) Advanced Bionics (Bron, France)

(Table 2).

Eighteen (35%) patients stayed overnight at the hospital because the criteria for ambulatory

21

Specifications %

Brand of cochlear implant MEDEL 41

COCHLEAR 45

Number of patients implanted

on both sides

AB 14

17

Type of admission Outpatient 65

Inpatient 35 DHI score Hearing preservation Rate of dislocation 0 to 30 31 to 70 71 to 100 0 to 25 % 26 to 75% >75% Yes 74 24 2 6 25 25 2

Table 2: Patient characteristics and results of DHI questionnaire, Hearing preservation, rate

22

SVINT

Before surgery, SVINT was negative in 40 (78%) patients, i.e. 11 (22%) patients had

vestibular asymmetry. Among these patients, 10 had acquired deafness (progressive deafness,

petrous bone fracture, sudden deafness) and two patients had an implant on one side, and

vestibular deficit was on the side of the implant.

After surgery, SVINT was positive in 14 (27%) cases. Three new patients had VIN on the

opposite side to the implant. This corresponded to a vestibular deficit ipsilateral to the

cochlear implant which was consistent with the CT which showed a deficit of the same side of

the implant (Fig 2).

VEMP

Six (12%) patients were excluded in the post-operative test analysis, because they had not

done the test before surgery. In pre-operative assessment, 21 (41%) had VEMP bilaterally, 12

(23%) had no VEMP in either side, 9 (18%) had no VEMP on the side of the implant and 3

(6%) had no VEMP contralaterally. Among patients with no VEMP on the operated side, 6

patients had an acquired deafness, 2 had congenital deafness and 1 patient already had a

cochlear implant on the other side. Five of them had CT that did not match and which were

normal.

On post-operative assessment, of the 45 patients, 11 (24%) had VEMP bilaterally, 17 (38%)

had no VEMP on either side, 15 (33%) had no VEMP on the side of the implant and 2 (5%)

had no VEMP contralaterally. Six patients in addition with no VEMP ipsilateral to the implant

23

Caloric testing

Before surgery, 36 (71%) cases had normal test, so no vestibular asymmetry. Ten (20%)

patients had disturbed CT on the side of the cochlear implant and 5 (10%) patients had

reduced CT in the opposite side.

After the surgery, 24 (47%) patients still had normal CT on both sides, but 22 (43%) patients

had disturbed CT ipsilateral to the implant, i.e. 12 additional patients. Among these 12

patients, 10 patients had hyporeflexia and 2 patients had areflexia. Five other patients, who

had reduced CT in the opposite side, had no vestibular dysfunction on the operated side (Fig

24

0

10

20

30

40

50

SVINT

VEMP

Caloric testing

Pre-operative

assessment

Post-operative

assessment

Figure 2: Positive results for SVINT, VEMP and CT before and after cochlear implantation

(51 patients).

SVINT versus a strategy combining VEMP and Caloric Testing

Combining the results of VEMP and CT, we could determine the affected side. These results

were compared with SVINT results. Before surgery, there was one false positive in SVINT,

i.e. one patient had a nystagmus in SVINT but CT and VEMP were normal. The same applies

to 5 false negative with normal SVINT but CT and VEMP diminished or absent (Table 3).

In pre-operative assessment, for SVINT, the sensitivity was 67%, the specificity was 98% and

positive predictive value was 91%. After surgery, sensitivity was 52%, specificity and

positive predictive value were 100% (Table 3).

25 Pre-operative N=51 Post-operative N=51 Prevalence % 29.0 [17.0; 43.8] 53.0 [38.0; 67.1] True positives 10 14 True negatives 35 24 False positives 1 0 False negatives 5 13 Sensitivity % [CI95%] 66.7 [38.4; 88.2] 51.9 [31.9; 71.3] Specificity % [CI95%] 97.2 [85.5; 99.9] 100 [85.8; 100] Positive Predictive Value % [CI95%] 90.9 [58.7; 99.8] 100 [76.8; 100] Negative Predictive Value % [CI95%] 87.5 [73.2; 95.8] 64.9 [47.5; 79.8] Positive Likelihood ratio

Negative Likelihood ratio

24.0 [3.36; 171] 0.343 [0.167; 0.703]

-

0.481 [0.326; 0.712]

Table 3: Results of SVINT versus a diagnostic strategy combining results of VEMP and CT

in patients with cochlear implants.

Questionnaires

Eleven (21%) patients did not return their questionnaires despite two reminders.

Regarding the APHAB questionnaire, because only the part with hearing aids (cochlear

implant) was completely filled out, we were only able to calculate the benefit of the implant

for 9 (18%) patients therefore we did not analyze this questionnaire due to lack of data.

For the GBI questionnaire, 34 (84%) patients reported a benefit from cochlear implants, 6

26

**

For the DHI questionnaire, 29 (74%) patients scored between 0 to 30, 9 (24%) patients

between 31 to 70, and one (2%) patient between 71 to 100. This patient had hyporeflexia in

CT after cochlear implantation (Table 2).

Hearing Preservation

Hearing preservation rates were successfully calculated for 29 (57%) patients. The occurrence

rates of dizziness and lack of dizziness after surgery were similar in each category of hearing

preservation. No link was found between the appearance of vertigo after surgery and the

preservation rate (Fischer Test: p=1.000) (Table 4).

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Complete

preservation

Partial

preservation

Minimal

preservation

No

post-operative

dizziness

Post-operative

dizziness

** = p>0,05, no significantTable 4: The link between the occurrence of dizziness and hearing preservation rate in 29

(57%) patients.

NS

NS

NS

NS

27

Rate of dislocation

One patient had a dislocation of electrodes in the scala vestibuli. This patient had dizziness

after surgery and the DHI score was 32. Caloric testing showed an areflexia on the operated

side. VEMP was preserved and SVINT showed a contralateral VIN. No statistical analysis

could be performed because there was just one dislocation.

Functional outcome of cochlear implant

No link was found between the functional outcome of cochlear implant and the appearance of

vertigo after surgery (Fischer Test: p=0.665) (Fig 3).

Figure 3: Link between functional outcome of cochlear implant and DHI score in 31 patients.

NS NS=no significant Score of speech audiogram using only cochlear implant, in free field, with a monosyllabic list, without lip reading, at 60 dB (success rate in %):

28

DISCUSSION

To study vestibular function, CT are the most frequently used, as the standard technique [2, 5,

8, 10]. In our study, this test was used as a reference to assess vestibular function and to

compare SVINT results. Ten patients had disturbed CT before surgery because one patient

had trauma side deafness, another patient had sudden deafness on the same side and the others

had either congenital or acquired deafness. The causes of deafness were heterogeneous, like

other studies [10, 20]: progressive deafness (51%), congenital (17%), sudden deafness (12%),

otosclerosis (8%), meningitis (4%), otitis/trauma/drug-induced/hydrops (2%).

Katsiari et al. found that although cochlear implantation led to measurable changes in the

peripheral vestibular function, permanent dizziness was rare [10]. Most of patients were only

transiently affected in their everyday life. In the literature, incidence of dizziness is now

probably overestimated. This is related to several factors.

Firstly, the surgical technique type affects the occurrence of dizziness. Coordes et al. showed

the influence of cochlear implantation on the vestibular function, particularly according to the

surgical technique used [15]. Todt et al. investigated the impact of different cochleostomy

techniques on vestibular receptor integrity and dizziness after cochlear implantation [14].

They used questionnaire (DHI), CT for the function of the lateral semicircular canal, and

VEMP for saccular function. They compared two approaches for cochlear insertion: round

window insertion and anterior cochleostomy to the round window niche. In conclusion, they

proved that the round window approach for electrode insertion should be preferred to decrease

the risk of vestibular lesions and occurrence of dizziness [14]. This technique is an atraumatic

29

with this procedure, i.e. 1 patient/5) [15]. In our study, we used the round window approach

and there was one electrode dislocation in scala vestibuli.

Secondarily, common vestibular tests are currently more efficient. In older publications,

techniques used sometimes included electronystagmography. In our study, we wanted an easy

and reliable assessment of vestibular function after cochlear implantation. SVINT involves

stimulating a 100 Hz bone-conducted vibration, applied to either mastoid and to forehead.

Skull vibrations applied to the mastoid by SVINT are more efficient than vibrations applied to

the posterior cervical muscles for the measurement of energy transfer [21]. Therefore, mastoid

stimulation is recommended. This induces a predominantly horizontal nystagmus, with rapid

phases beating away from the affected side in unilateral peripheral vestibular loss. It is a

useful, simple, non-invasive, robust indicator to help the clinician identify asymmetry in

vestibular function and the affected side. The nystagmus is precisely stimulus-locked: it starts

with stimulation onset and stops at stimulation offset, with no post-stimulation reversal. It is

sustained throughout long stimulus durations and reproducible.

Todt et al. found that the saccule was most frequently damaged [14]. In their data, VEMP

results were not more recordable after surgery when caloric testing deteriorated. In our study,

when VEMP were not recordable, CT were disturbed on the same side.

Xie et al [5] showed that SVINT had higher sensitivity and sensibility to CT compared with

head shaking nystagmus (81 % and 100 % for SVINT, 63 % and 70 % for head shaking

nystagmus, 91 % and 100 % for CT) in patients with unilateral peripheral vestibular disorder.

In our study, compared with results for VEMP and CT, we showed that SVINT had a

sensitivity of 67%, specificity of 98% and positive predictive value of 91%. After surgery,

30

are consistent with the study of Xie et al [5]. Dumas et al. found 96 % sensitivity and 94 %

specificity for SVINT in partial vestibular lesions[6].

We had five false negatives SVINT in pre-operative assessment because it was proven that

the induction of VIN was significantly related to the degree of canal paresis of the CT [2]. In

the Ohki et al.’s study, among patients with canal paresis of more than 50 %, 90 % showed

VIN but only 20 % of patients with canal paresis of less than 20 % had positive SVINT [2].

Dumas et al. proved that the sensitivity of SVINT increases with the degree of vestibular

deficit [4]. Also for Xie et al., VIN was often observed in unilateral vestibular disorder

especially in patients with profound vestibular damages.

In our data, during pre-operative assessment, 11 (22%) patients had positive SVINT, and

therefore a vestibular asymmetry, because of the origin of the deafness and two patients had a

cochlear implant on the affected side.

Complaints related to dizziness are occasional and transitory following cochlear implantation

[22]. SVINT is quicker to detect profound vestibular damages and it avoids achieve caloric

testing which is more restrictive.

Regarding questionnaires, the APHAB questionnaire was filled out incompletely. Only nine

patients had correctly answered it before and after surgery. This is due to the fact that the

questionnaire was not always given before the cochlear implant, and patients who received

the questionnaire after surgery only completed the part regarding cochlear implant.

As for the DHI questionnaire, the patient with dislocation of electrodes in scala vestibuli

scored 32. This patient already suffered from canal paresis before surgery, and after cochlear

31

assess self-perceived handicap due to vertigo [14, 23]. For Todt et al, there was a statistically

significant difference between round window approach surgery and anterior cochleostomy

surgery, with an increase of vertigo in the second group [14].

For the rate of hearing preservation, the score of 29 (57 %) patients was calculated but no link

was found between occurrence of dizziness and hearing preservation. Thirteen (25%) patients

had complete hearing preservation, the same number had partial preservation and three (6 %)

had minimal preservation. In the study of Coordes et al, using the round window membrane

approach, with perimodiolar cochlear implant electrodes, the complete hearing preservation

rate was 18 % and the partial preservation rate was 56 % out of a total of 11 patients [15].

CONCLUSION:

SVINT enables us to study the vestibule at high frequencies and reveals asymmetric

vestibular function. This is a non-invasive, quick and thorough test, which functions like the

Weber vestibular test. In the cochlear implantation, there may be a vestibular disorder in the

horizontal semicircular canal, but also in sacculus function. In our study 26% of patients had

dizziness after cochlear implantation, according to the DHI questionnaire (24% had regular

discomfort and 2% had little discomfort). The SVINT results, compared to caloric testing and

vestibular evoked myogenic potential, were complementary in detecting vestibular disorders

33

1. Hamann KF, Schuster EM. Vibration-induced nystagmus: a sign of unilateral

vestibular deficit. ORL 1999; 61:74-9.

2. Ohki M, Murofushi T, Nakahara H, Sugasawa K. Vibration-induced nystagmus in

patients with vestibular disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003; 129:255-58.

3. Dumas G, De Waele C, Hamann KF et al. Skull vibration induced nystagmus test. Ann

OtolaryngolChirCervicofac 2007; 124:173-83.

4. Dumas G, Karkas A, Perrin P, Chahine K, Schmerber S. High-Frequency Skull

Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test in Partial Vestibular Lesions. Otology and

Neurotology 2011; 32:1291-1301.

5. Xie S, Guo J, Wu Z et al. Vibration-induced nystagmus in patients with unilateral

peripheral vestibular disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013; 65:333-38.

6. Dumas G, Perrin Ph, Morel N, N’Guyen DQ, Schmerber S. Skull vibratory test in

partial vestibular lesions – Influence of the stimulus frequency on nystagmus

direction. LaryngolOtolRhinol2005; 126.4:235-42.

7. Dumas G, Lavieille JP, Schmerber S. Characterization of Skull Vibration-Induced

Nystagmus Test: comparison with results of Head Shaking Test. Ann

OtolaryngolChirCervicofac 2007; 124:173-83.

8. Krause E, PR Louza J, Wechtenbruch J, Gurkov R. Influence of cochlear implantation

on peripheral vestibular receptor function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;

34

9. N. Melvin TA, Della Santina C, Carey J, Migliaccio A. The effects of cochlear

implantation on vestibular function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 30:87-94.

10. Katsiari E, Balatsouras D, Sengas J, Riga M, Korres G, Xenelis J. Influence of

cochlear implantation on the vestibular function. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol2013;

270:489-95.

11. Krause E, Louza J, Wechtenbruch J, Hempel JM, Rader T, Gurkov R. Incidence and

quality of vertigo symptoms after cochlear implantation. J LaryngolOtol 2009;

123:278-82.

12. Handzel O, Burgess BJ, Nadol JB Jr. Histopathology of peripheral vestibular system

after cochlear implantation in the human. OtolNeurotol 2006; 27:57-64.

13. Tien HC, Linthicum FH Jr. Histopathologic changes in the vestibule after cochlear

implantation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery 2002; 127:260-4.

14. Todt I, Basta D, Ernst A. Does the surgical approach in cochlear implantation

influence the occurrence of postoperative vertigo? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;

138: 8-12.

15. Coordes A, Ernst A, Brademann G, Todt I. Round window membrane insertion with

perimodiolar cochlear implant electrodes. OtolNeurotol 2013; 34:1027-32.

16. Jutila T, Aalto H, P. Hirvonen T. Cochlear implantation rarely alters horizontal

35

17. Robinson K, Gatehouse S, Brownog G G. Measuring patient benefit from

otorhinolaryngological surgery and therapy. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1996;

105:415-22.

18. Skarzynski H, Van de Heyning P, Agrawal et al. Towards a consensus on a hearing

preservation classification system. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2013; 133:3-13

19. Eshraghi AA, Yang NW, Balkany TJ. Comparative study of cochlear damage with

three perimodiolar electrode designs.Laryngoscope 2003; 113:415-9.

20. Krause E, Wechtenbruch J, Rader T, Gürkov R. Influence of Cochlear Implantation on

Sacculus Function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 140:108-13.

21. Dumas G, Lion A, Perrin P, Ouedraogo E, Schmerber S. Topographic analysis of the

skull vibration-induced nystagmus test with piezoelectric accelerometers and force

sensors. NeuroReport 2016; 27:318-22.

22. Schmerber S, Berta E, Rivron A, Dumas G, Karkas A. Exploration vestibulaire par test

vibratoire osseux chez le patient implanté cochléaire. Annales Françaises

d’Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie et de pathologie cervico-faciale 2013; 130:33.

23. Parmar A, Savage J, Wilkinson A, Hajioff D, Nunez D A, Robinson P. The Role of

Vestibular Caloric Tests in Cochlear Implantation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;

36

SERMENT D’HIPPOCRATE

En présence des Maîtres de cette Faculté, de mes chers condisciples et devant l’effigie d’HIPPOCRATE, Je promets et je jure d’être fidèle aux lois de l’honneur et de la probité dans l’exercice de la Médecine. Je donnerai mes soins gratuitement à l’indigent et n’exigerai jamais un salaire au-dessus de mon travail. Je ne participerai à aucun partage clandestin d’honoraires. Admis dans l’intimité des maisons, mes yeux n’y verront pas ce qui s’y passe ; ma langue taira les secrets qui me seront confiés et mon état ne servira pas à corrompre les mœurs, ni à favoriser le crime. Je ne permettrai pas que des considérations de religion, de nation, de race, de parti ou de classe sociale viennent s’interposer entre mon devoir et mon patient. Je garderai le respect absolu de la vie humaine. Même sous la menace, je n’admettrai pas de faire usage de mes connaissances médicales contre les lois de l’humanité. Respectueuse et reconnaissante envers mes Maîtres, je rendrai à leurs enfants l’instruction que j’ai reçue de leurs pères. Que les hommes m’accordent leur estime si je suis fidèle à mes promesses. Que je sois couverte d’opprobre et méprisée de mes confrères si j’y manque.

37

Remerciements à l’ensemble des personnes rencontrées pendant mon internat

Au Docteur Ihab ATALLAH : j’ai commencé mon internat il y a cinq avec toi lorsque tu

étais assistant. Nous avons passé de nombreuses astreintes ensemble et j’ai d’ailleurs débuté les premières avec toi, avec tout le stress qui me caractérise. Tu es passionné par ce que tu fais et c’est un vrai plaisir d’apprendre à tes côtés. Tu as également été disponible pour moi

lorsque j’en avais besoin et cela m’a beaucoup apaisée. J’espère pouvoir un jour de nouveau travailler avec toi.

Au Docteur Alexandre KARKAS : par quoi commencer…. Ce fut un réel plaisir de t’avoir

connu comme assistant mais surtout en tant que personne. Je ne vais pas énumérer tous ces « bijoux » que tu m’as appris pendant ma formation et je sais que nous étions privilégiés de t’avoir à nos côtés. Je te suis reconnaissante de m’avoir fait partager tes connaissances et d’avoir pu profiter de ton humour.

Au Docteur Joëlle TROUSSIER : quelle énergie et quelle passion pour l’audiophonologie.

Je te remercie de m’avoir fait partager cette ardeur si communicative et cette implication avec les enfants. J’espère un jour de nouveau apprendre de ton savoir. Merci encore pour ce que tu nous apportes.

Au Docteur Alice HITTER : même si tu ne liras sûrement jamais ces mots, il est important

pour moi de te remercier pour tout ce que tu m’as apporté pendant ces cinq dernières années autant sur le plan humain que professionnel. Et cet humour si ravageur ! Peut-être aurons-nous l’occasion de aurons-nous revoir….

Au Docteur Anne RIVRON : je te remercie de m’avoir transmis tes connaissances dans

notre spécialité et de me montrer l’implication qu’il faut avoir chez les patients implantés cochléaires dans les suites de leur chirurgie.

Au Docteur Alain ATTARD : j’espère pouvoir apprendre encore beaucoup de votre

expérience.

Au service d’ORL du Pr Patrick MANIPOUD et à toute son équipe : à l’ensemble des

médecins rencontrés dans ce service. A cette équipe que je ne peux pas oublier : à ma

38

Sandrine si patiente et si maternelle, à ma Faustine (c’était un plaisir d’avoir travaillé avec toi).

Au service de chirurgie viscérale du Dr Philippe GABELLE : c’était un semestre

enrichissant sur le plan professionnel mais aussi humain.

Au service de Chirurgie Maxillo Faciale ET Chirurgie Plastique !!! : le semestre fut

tellement agréable et c’était un plaisir d’avoir pu travailler avec vous. A mes chefs : à Emma (que j’apprécie beaucoup), à Marine (pleins de bisous !!), à Aurélie (tellement attachante), à Julie (ne change pas !), au Dr GIOT que j’ai pu rencontrer à la fin du semestre, à Béatrice (si passionnée et qui m’a beaucoup appris), à Odile !!!, à l’ensemble de l’équipe infirmière (service et consultations : AU TOP !!!) et aux secrétaires.

Au service d’explorations fonctionnelles du Pr Hung THAI VAN : à l’ensemble des

secrétaires et des infirmières rencontré à HEH et à l’HFME, et que je vais bientôt retrouver avec plaisir !!!

Dans le service d’ORL du CHU de Grenoble :

Merci à Mme Christelle BRICHET et à l’ensemble de son équipe de secrétaires (Caro, Christelle, Ludy, Colette, Mélanie, Annick, Anne Laure et à toutes celles que j’ai pu croiser pendant mon internat).

Merci à l’équipe des consultations : ma Ghislaine (qui me manque), à Jacqueline, à Martine (tu vas me manquer !), à Laurence, aux nouvelles venues Jennifer et Sabine.

Merci à l’équipe des audioprothésistes, des orthophonistes et à Solène pour m’avoir fait partager votre métier pendant mon stage d’explorations fonctionnelles.

A l’équipe du service !!!!! Il y en a tellement à citer, certains qui sont encore là et d’autres qui sont partis (Meg Ann, Amélie, Steph, Sabrina, Julie, Margaux, Eléonore, Alice,

Tournoudland, Laurence, Marion, Ségo, Tiphaine, Nadine, Marine, Lydie, Stéphanie, Sophie, Val, Guillaume, Corinne, Chantal, Sandra ….). Je sais que j’en oublie et je m’en excuse d’avance…. Ce fut un tel plaisir d’avoir travaillé avec vous mais aussi d’avoir partagé d’autres choses que le travail. Ne changez pas !

A l’équipe du bloc : que d’aventures et d’heures passées ensemble !!! Merci pour tout (Céline, Jacqueline, Karine, Djamila, Dr PRA, Marie Pierre).

39

A mes co-internes : à Alexandra (j’ai commencé et je finis avec toi !!!), à Akilou (j’ai appris

à te connaître pendant l’internat alors qu’on était dans la même promo !!, ce fut un plaisir !), à Raph (à nos souvenirs de DU), à Cindy (je me souviens encore du premier jour où je t’ai rencontré sous la pluie à Chambé avec ta saxo !!!), à Annie (tu es parfaite !! ne change pas), à Christol (tu m’étonneras toujours vu ce que tu manges au McDo), à Ashley (c’est un réel plaisir de finir mon internat avec toi surtout quand je vois tout ce que j’ai pu oublier dans les autres spé !!!! j’apprécie ta prise en charge avec les patients et tes connaissances ; je veux un bisou avant de partir !), à Marie (tu es superbe Dr SOULA !!!), à Ludo (nous n’avons pas pu travailler ensemble mais ce fut un plaisir de t’avoir rencontré), à Claire (bonne continuation dans ton internat), à Mathieu (Dr Meunier !!!!, merci de m’avoir récupéré des astreintes quand la vieille était bloquée du dos, merci aussi pour ton humour et au fait que tu ris à mes

blagues !!! bonne continuation !).

Aux autres internes rencontrés : à Virginie (c’est agréable de travailler et de discuter avec

toi), à Rodo (merci pour m’avoir appris les bases de ta spé ! et merci pour ton humour !), à Olivier et Julie (à notre début d’internat), à Camille (génial ce semestre avec toi en chir générale, et les discussions à propos de « l’enfant » !!!), à Adrianne (c’était un plaisir de t’avoir rencontré), à Marco (euh euh euh ….. une châtaigne !!!!), à Steph (que j’ai pu croiser via la neurochir).

Aux assistants d’ORL : A Elea (merci pour ces années passées ensemble et bonne

continuation dans ton futur rôle de maman !), à Eric (quel plaisir ! j’ai ri du début à la fin ! bonne continuation avec ta petite famille), à Philippe et à Etienne !

40

A ma famille

A mes parents : vous avez toujours été présents tout au long de mes études et vous avez

supporté mes sauts d’humeur !!! Merci pour votre soutien indéniable ! Merci pour l’éducation que vous m’avez apportée et merci d’être toujours là quand j’en ai besoin. Mon Noé a de la chance de vous avoir comme grands parents !

A ma sœur, mon beau-frère et à Maeva : merci pour votre soutien ! A ma Vava, je

n’arriverai pas à t’appeler autrement !!! A ma nièce, ne grandis pas trop vite !!! A Bruno toujours aussi bosseur.

A ma belle-famille : à mes beaux-parents Sylvie et Alain, ma belle-sœur Isaline, à Léa et

Loris, aux cousins et cousines, aux oncles et tantes. Je n’aurai pas pu trouver mieux comme belle famille ! Merci pour votre soutien et pour l’accueil que vous m’avez fait au sein de votre famille. Je suis ravie à l’idée que Noé profite de grandir parmi vous.

A mon loulou : Sylvian, désolée pour tous les moments de stress que je t’impose mais

j’espère m’améliorer avec le temps, comme tu dis ! Je ne vois pas notre différence d’âge et je suis pleinement comblée d’avoir pu construire une petite famille avec toi. J’espère que nous en sommes qu’au début !!! Tu es toujours là pour m’épauler, me rassurer et pour cela je ne te remercierai jamais assez. Merci encore pour tous ces moments de bonheur si simples de la vie quotidienne.

A mon Noé : mon petit bébé d’amour ! Tu es simplement du pur bonheur. J’espère être là

dans tous les moments de ta vie, les pires comme les meilleurs, et te soutenir comme j’ai pu l’être. Toi aussi, ne grandis pas trop vite!

41

Objectives: To evaluate the benefit of the skull vibration-induced nystagmus test to diagnose

vestibular disorders in cochlear implantation.

Methods: This was a prospective monocentric study in the French cochlear implant center of

the Alps, between January 2014 and January 2016 in 51 patients who received a cochlear

implant. The vestibular function was studied with SVINT (skull vibration-induced nystagmus

test) and compared with vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP), caloric testing (CT)

and questionnaires (Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit, Glasgow Benefit Inventory,

Dizziness Handicap Inventory) results. Patients with inner ear malformations and preoperative

dizziness were excluded from the study. The surgery consisted of the insertion of the

electrodes through a round window niche.

Results: Before surgery, SVINT was positive in 11 (22%) patients and remained so after

surgery. Three additional patients had positive SVINT after surgery making a total of 14

(27%) patients. Concerning CT, preoperatively, 36 (71%) cases had normal test and after

surgery, 24 (47%) patients had normal CT on both sides. For SVINT, sensitivity was 67% and

specificity was 98% before surgery. After surgery, sensitivity was 52% and specificity was

100%.

Conclusion: The SVINT is a rapid, non-invasive test and is complementary to other tests in

42

Objectif: Evaluer le bénéfice du test vibratoire osseux (TVO) pour le diagnostic des troubles

vestibulaires dans l’implantation cochléaire.

Méthode: Etude prospective monocentrique au centre d’implantation cochléaire des Alpes, de

Janvier 2014 à Janvier 2016 sur 51 patients ayant bénéficié d’un implant cochléaire. La fonction vestibulaire a été étudiée par le TVO et les résultats ont été comparés à ceux des

potentiels évoqués otolithiques myogéniques (PEOM) et des tests caloriques. Les patients

présentant une malformation de l'oreille interne et des vertiges préopératoires étaient exclus

de l’étude. L'insertion de l'électrode était réalisée dans tous les cas via la fenêtre ronde.

Résultats: Avant la chirurgie, le TVO était positif chez 11 (22%) patients et il est resté positif

en post opératoire. Trois autres patients ont eu également un test positif en post opératoire ce

qui faisait un total de 14 (27%) patients. Les tests caloriques en pré opératoire étaient

normaux chez 36 (71%) patients. Après la chirurgie, 24 (47%) des patients conservaient des

résultats normaux bilatéralement. Pour le TVO, la sensibilité était de 67% et la spécificité de

98% avant la chirurgie. En post opératoire, la sensibilité était de 52% et la spécificité de

100%.

Conclusion: Le TVO est un test rapide, non invasif et est complémentaire des autres tests

pour le diagnostic d’altérations vestibulaires après implantation cochléaire.

Mots-clefs : Test Vibratoire Osseux, fonction vestibulaire, implantation cochléaire, potentiels