Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent

to the repository administrator:

tech-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

This is an author’s version published in:

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/19162

To cite this version:

Dubois, Didier and Fusco, Giovanni and Prade,

Henri and Tettamanzi, Andrea Uncertain logical gates in possibilistic

networks: Theory and application to human geography. (2017) International

Journal of Approximate Reasoning, 82. 101-118. ISSN 0888-613X

Official URL

DOI :

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijar.2016.11.009

Open Archive Toulouse Archive Ouverte

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse

researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible

Uncertain

logical

gates

in

possibilistic

networks:

Theory

and

application

to

human

geography

✩

,

✩✩

Didier Dubois

a,

Giovanni Fusco

b,

Henri Prade

a,∗,

Andrea

G.B. Tettamanzi

caIRIT–CNRS,UniversitédeToulouse,118,routedeNarbonne,Toulouse,France bUniversitéCôted’Azur,CNRS,ESPACE,98,bdEdouardHerriot,Nice,France

cUniversitéCôted’Azur,CNRS,Inria,I3S,2000,routedesLucioles,SophiaAntipolis,France

a b s t r a c t Keywords: Possibilitytheory Beliefnetworks Noisygates Expertknowledge Humangeography

Possibilisticnetworksofferaqualitativeapproachformodelingepistemicuncertainty.Their practicalimplementation requiresthe specification ofconditional possibilitytables, asin the case of Bayesian networks for probabilities. The elicitation of probability tables by expertsismademucheasierbymeansofnoisylogicalgatesthatenablemultidimensional tablestobeconstructedfromtheknowledgeofafewparameters.Thispaperpresentsthe possibilisticcounterpartsofusualnoisyconnectives(and,or,max,min,. . . ).Theirinterest and limitations are illustrated on an example taken from a human geography modeling problem.Thedifferenceofbehavior betweenprobabilistic andpossibilisticconnectivesis discussed in detail. Results in this paper may be useful to bring possibilistic networks closertoapplications.

1. Introduction

Abeliefnetwork[24,25]isaconvenientwayofrepresenting theinteractionbetweenuncertainvariablesintheformof

a directedgraph,each nodeof which represents avariable. Thegraphical structuretakes advantage of known conditional

independence betweenthese variables.Eachvariableis directlyinfluencedonlybyitsparent variablesinthegraph.Given

such adirectedgraphbetweenvariables andlocal conditional probabilitytables,the jointprobability distributionofthese

variables canberetrieved;see[20]for anintroductionto Bayesianbeliefnetworks.In facttheycan bebuiltintwo ways:

they can be extracted from data or made up by a human expert. In the first case, a supposedly large dataset involving

a numberof variablesis available,and the Bayesiannetwork is obtainedby some machinelearningprocedure. The

prob-ability tablesthus obtained have a frequentist flavor, and thesimplest network possible issearched for. On thecontrary,

when Bayesiannetworks canbespecifiedusingexpertknowledge,thestructureofanetwork relatingthevariablesisfirst

given,oftenrelyingoncausalconnectionsbetweenvariablesandconditionalindependencerelationstheexpertisawareof.

Then,subjectiveprobabilitytablesmustbefilledbytheexpert.Theyconsist,foreachvariableinthenetwork,ofconditional

probabilitiesforthatvariable,conditionedoneachconfigurationofitsparentvariables.Notethat,evenifcausalrelationsas

✩ Thisarticleisarevisedandextendedversionof[11].

✩✩ This paperispartof thevirtualspecialissue on theNinthInternationalConference onScalable UncertaintyManagement(SUM2015), edited by

ChristophBeierle.

*

Correspondingauthor.E-mailaddresses:dubois@irit.fr(D. Dubois),fusco@unice.fr(G. Fusco),prade@irit.fr(H. Prade),andrea.tettamanzi@unice.fr(A.G.B. Tettamanzi).

URL:http://www.elsevier.com(D. Dubois).

perceived bythe expertareinstrumental inbuildinga simpleand interpretable network,the jointprobability distribution

obtainedbycombiningtheprobabilitytablesnolongeraccountsforcausality(thereareasmany beliefnetworksas

permu-tationsofvariablesrepresentingthesamejointprobabilitydistribution).Anotherdifficultyarisesforsubjectiveexpert-based

Bayes networks: if variables are notbinary and/or thenumber of parent variables ismore than two, the taskof eliciting

numerical probability tables becomes tedious, if not impossible to fulfill. Indeed, the number of probability values to be

suppliedincreases exponentiallywiththenumberofparent variables.

Toalleviatetheelicitationtask,thenotionofnoisylogicalgate (orconnective)hasbeen introducedbyPearl[24],based

on theassumptionofindependentcausalinfluencesthatcanbecombined(see also[25],Sec. 4.3.2).Asaresult,onesmall

conditional probability table iselicited per parent variable, and theprobability table of each variable given its parents is

obtained bycombining these small tables via aso-called noisy connective, which may include a so-called leakage factor

summarizing thecausaleffectofvariablesnotexplicitlypresent inthenetwork [10,19].

While thenotion ofnoisy connectivesolvesthecombinatorial problemofcollecting many probability valuesto alarge

extent, the issue remains that people cannot always provide precise probability assessments. Let alone the fact that the

probability scaleistoofine-grainedforhumanperceptionofbelieforfrequencies,some conditionalprobabilityvaluesmay

be ill-knownor plainly unknown tothe experts.The usual Bayesianrecommendation in thelatter caseis to useuniform

distributions, but it is well-known (see for instance [15,16]) that these distributions do not properly model ignorance.

Alternatively,one mayuseimpreciseprobabilitynetworks (calledcredalnetworks) [21],qualitativeBayesiannetworks[27]

or possibilistic networks [5]. While the two first options extend probabilistic networks to ill-known parameters (with an

interval-based approachfor thefirstextension and an ordinalapproachfor thesecond), possibilisticnetworks represent a

more drastic departure from probabilistic networks. In their qualitative version, possibilistic networks can be defined on

a finitechain of possibility values and do not refer to numerical values. This feature may make the collection of expert

information onconditional tableseasierthan requiring precisenumbersobeyingthelawsofprobability.However, whenit

comes to fillingconditionaluncertaintytables,thedimensionalityissue present inBayesiannetworks remainsthesamein

thepossibilisticenvironment.

Thisiswhyinthispaper,weproposepossibilisticcounterpartsofnoisy connectivesofprobabilisticnetworks. As

possi-bilistic uncertainty ismerely epistemicand due toa lackof information,we shall speakofuncertainconnectives. Theidea

ofpossibilisticuncertaingateswas firstconsideredempiricallybyParsons andBigham[23]directlyinthesettingof

possi-bilistic logic,atatimewhenpossibilisticnetworks had notyet beenintroduced. Itseemsthatthequestion ofpossibilistic

uncertaingateshas notbeenreconsideredeversince,if weexcept arecent studyinthebroadersetting ofimprecise

prob-abilities [1].The basic ideas pervadingthis paperfirstappear in aFrench conference paperbytheauthors [8],thenmore

formallyintheSUM 2015conferenceproceedings[11].

This paper elaborateson these preliminary versions. In particular, we explain the constructionof possibilistic gates in

greater detail. Moreover, we introduce the leaky version of several such gates, as well as variants needed for describing

the reinforcementofthe possibilityof effectsdue tothepresence ofmultiple causes. Acomparisonbetween probabilistic

(noisy)gatesandpossibilisticgatesiscarriedout,emphasizingtheirdifferenceintermsofexpressivepowerandrespective

concerns.Lastly,anextensiveaccount oftheapplicationtohumangeographyisprovided.

The paperis structuredasfollows. Afterrecalling probabilisticnetworks with noisy gates inSection 2, wepresent the

corresponding approach for possibilistic networks and present various uncertaingates, especially the AND, OR, MAX, and

MINfunctions inSection3.InSection 4,wecomparetheuncertainOR-gateand thenoisyOR-gateindetail,and proposea

variant ofthe uncertainMAXthat behavesmorein agreementwiththenoisy MAX.Algorithmsneeded toimplement this

approacharediscussedinSection5.Finally,theapproach,includingalgorithmicissues,isillustratedinSection6onabelief

network dealingwithanapplication tohumangeography.

2. Probabilisticnetworkswithindependentcausalinfluences

Consideraset ofindependentvariables X1,. . . ,Xn that influencethevalueofavariable Y .In theidealcase,thereisa

deterministicfunction f suchthat Y= f(X1,X2,. . . ,Xn).Inordertoaccountforuncertainty,onemayassumetheexistence

of intermediaryvariables Z1,. . . ,Zn,such that Zi expressesthefact that Xi willhave acausal influenceon Y , and which

value of Y it enforces ( Zi has the same range as Y ). It is assumed that the relation between Xi and Zi is probabilistic

and that Zi isindependent ofother variablesgiven Xi. Besides,we consider thedeterministic functionasaffected bythe

auxiliaryvariables Zi only.Inotherwords,wegetaprobabilisticnetworksuchthat[10]

P

(

Y,

Z1, . . . ,

Zn,

X1, . . . ,

Xn)

=

P(

Y,

Z1, . . . ,

Zn)

·

nY

i=1

P

(

Zi|

Xi),

(1)where P(Y,Z1,. . . ,Zn)=1 if Y = f(Z1,. . . ,Zn) and 0otherwise. This is calleda noisyfunction.In particular, notice that

thedependencetablesbetween Y and X1,. . . ,Xn cannowbeobtainedbycombiningsimple conditionalprobability

distri-butions pertainingtosinglefactors.Foranyeffectvalue y of Y ,andevery n-tuple(x1,. . . ,xn) ofinputvalues:

P

(

y|

x1, . . . ,

xn)

=

X

z1,...,zn:y=f(z1,...,zn) nY

i=1 P(

zi|

xi).

(2)This is the assumption of independenceofcausalinfluence (ICI) [10]. In the case of Boolean variables, it is assumed that

P(Zi=0|Xi=0)=1 (if no cause, thenno effect), while P(Zi=0|Xi=1) could bepositive (theeffectmay ormay not

appear whenthecauseispresent).

CanonicalICImodelsareobtainedbymeans ofspecificchoices offunctions f . Forinstance,if allvariablesareBoolean,

f willbealogicalconnective.Inthiscase,wespeakofnoisyOR( f= ∨)[24,25],noisyAND( f = ∧);iftherangeofthe Zi’s

and Y isatotallyorderedset,usualgatesarethenoisyMAX( f=max),orMIN( f =min).ICImodelsareinthesamespirit

asearlyprobabilisticapproachestodiagnosissuchastheparsimoniouscoveringtheoryofPengandReggia[26],wherethe

likelihoodofamanifestationtobeproducedbyasetofindependentcausesiscomputedfromtheindividuallikelihoodsfor

eachcause.

Theapproachmaybefurtherrefinedbyallowing f tosummarizethepotentialeffectofexternalvariablesnottakeninto

account: thisisthe leakymodel. Then, Y also dependson a leakage variable ZL not explicitly related to identified causes,

i.e., Y = f(Z1,Z2,. . . ,Zn,ZL). The rangeof ZL is supposed to bethe range of f , i.e., the rangeof Y and thisvariable is

independentoftheotherones.Hence,theleakymodelmaybewrittenas:

P

(

Y,

Z1, . . . ,

Zn,

ZL,

x)=

P(

Y,

Z1, . . . ,

Zn)

·

P(

ZL)

·

nY

i=1

P

(

Zi|

Xi),

so thatforanyvalue y ofY andany configuration(x1,. . . ,xn)ofparentvariables:

P

(

y|

x1, . . . ,

xn)

=

X

z1,...,zn,zL:y=f(z1,...,zn,zL) P(

zL)

·

nY

i=1 P(

zi|

xi).

(3)For instance,inthecaseofBooleanvariables, P(Y =1|X1=0,. . . ,Xn=0)maybepositiveduetosuchexternalcauses.

Wewillnow turntothequestionwhetherthesamekindofICIapproachcanbeusedto elicitpossibilisticnetworksas

well.

3. Uncertainlogicalgatesincanonicalpossibilisticnetworks

Possibility theory [12,30] is based on maxitive set functions associated to possibility distributions. Formally, given a

universe ofdiscourse U , apossibility distribution

π

:U→[0,1] pertainsto avariable X rangingon U and representstheavailable(incomplete)informationaboutthemoreorlesspossiblevaluesof X ,assumedtobesingle-valued.Thus,

π

(u)=0means that X=u is impossible. Theconsistency ofinformation isexpressed bythenormalization of

π

:∃u∈U,π

(u)=1,namely, at least one value is fully possible for X . Distinct values u and u′ may be simultaneously possible at degree 1.

A state of completeignorance isrepresented by the distribution

π?

(u)=1,∀u∈U . The degreeof possibility of an eventA⊆U isdefined bythesetfunction

5(

A)

=

sup u∈Aπ

(

u)

calledapossibilitymeasure.Possibilitymeasures aremaxitive, i.e.,

∀

A,

∀

B, 5(

A∪

B)

=

max(5(

A), 5(

B)).

The underlying assumption is that the agent focuses on the most plausible values compatible with event A, neglecting

other ones.Adual measureofnecessity N(A)=1− 5(U\A) expressesthedegreeofcertainty ofevent A asthedegreeof

impossibilityofnon- A.

Apossibilisticnetwork [5] hasthe samestructure asaBayesiannetwork.Thejoint possibilityfor n variableslinkedby

anacyclicdirectedgraphisdefinedbythechainrule:

π

(

x1, . . . ,

xn)

= ∗

i=1,...,nπ

(

xi|

pa(

Xi)),

where xi isaninstantiationofthevariable Xi,and pa(Xi)aninstantiationoftheparent variablesof Xi.Theoperation∗is

generallychosenastheminimum(inthequalitativecase)[3],ortheproduct(inthenumericalcase)[6],andthisiswhatwe

shall assumeinthesequel.Notethatthebehaviorofproduct-basedpossibilisticnetsisveryclosetotheoneofBayesnets,

while min-based possibilistic networks have specificproperties. For instance, starting from possibilistic conditional tables,

andbuildingthejointpossibilitydistributionusingthechainrule,onecannotgenerallyretrievethesameconditionaltables,

due tothedrowningeffectofthemin operation[5].

3.1. Uncertaincausalfunctionsinpossibilisticnetworks

DeterministicmodelsY = f(X1,. . . ,Xn) aredefined likeintheprobabilisticcase:

π

(

y|

x1, . . . ,

xn)

=

(

1 if y

=

f(

x1, . . .

xn)

;Table 1

Elementarycausalpossibilitytable.

π(Zi|Xi) xi ¬xi

zi 1 0

¬zi κi 1

Note thatif y= f(x1,. . .xn),then

π

(y|x1,. . . ,xn)=1 indicatesthecertaintyof y becauseothervaluesofY aretreatedasimpossiblesince f isafunction.

Let us define possibilistic models with independent causal influences (ICI). We use a deterministic function Y =

f(Z1,. . . ,Zn) with n intermediary causal variables Zi, as for the probabilistic models, which indicate that the cause Xi

has produceditseffect.Now,

π

(y|x1,. . . ,xn)isoftheform:π

(

y|

z1, . . . ,

zn)

∗

π

(

z1, . . . ,

zn|

x1, . . . ,

xn),

where

π

(y|z1,. . . ,zn) obeysEquation(4).Again, eachvariable Zi only depends(inanuncertainway) onthevariable Xi.Thus,wehave

π

(z1,. . . ,zn|x1,. . . ,xn)= ∗i=1,...,nπ

(zi|xi).Thisleadstotheequalityπ

(

y|

x1, . . . ,

xn)

=

maxz1,...,zn:y=f(z1,...,zn)

∗

i=1,...,nπ

(

zi|

xi),

(5)whose similarity with Eq. (2) is striking. Notice that, when ∗=min, Eq. (5) boils down to applying the extension

prin-ciple [30] to function f , assuming fuzzy-valued inputs F1,. . . ,Fn, where the membership function of Fi is defined by

µ

Fi(zi)=π

(zi|xi).In case we suppose that y also depends in an uncertain way on other causes summarized by a leakage variable ZL,

givingbirthtoaleakyICImodel,wethengetthecounterpartofEq.(3),whichreads:

π

(

y|

x1, . . . ,

xn)

=

maxz1,...,zn,zL:y=f(z1,...,zn,zL)

∗

i=1,...,nπ

(

zi|

xi)

∗

π

(

zL).

(6)Inthefollowing,weprovideadetailedanalysisofpossibilisticcounterpartsofnoisygates.

3.2. UncertainOR

The variables are assumed to be Boolean (i.e., Y =y or ¬y, etc.). The uncertain OR (counterpart of the probabilistic

“noisy OR”) assumes that Xi=xi for at least one variable Xi represents a sufficientcause for getting Y =y, and Zi=zi

indicates that Xi=xi hascaused Y=y.Thisgives f(Z1,. . . ,Zn)=Wni=1Zi.The uncertaintyindicatesthat thecausesmay

failtoproduce theireffects. Zi= ¬zi indicatesthat Xi=xi did notcause Y=y duetothepresenceofsomeinhibitorthat

preventstheeffectfromtakingplace.Weassumeitismorepossiblethat Xi=xi causesY =y thantheopposite(otherwise

one couldnotsaythat Xi=xi issufficientforcausingY =y). Thenwemustdefine

π

(zi|xi)=1 andπ

(¬zi|xi)=κ

i<1.Besides,

π

(zi| ¬xi)=0,sincewhen Xi isabsent,itdoesnot cause y.Hencetheelementarycausalpossibility table,whereeachcolumnshouldcontain1,togetnormalconditionalpossibilitydistributions (seeTable 1).

Notethat inthecaseofaprobabilisticnetwork,

π

(zi|xi)=1 is replacedby P(zi|xi)=1−κ

i inTable 1.Let x beaconfigurationof (X1,. . . ,Xn),where xi denotesaliteral (xi or ¬xi)for Xi (and thesameconvention for Zi).

Wecanthenobtainthetableoftheconditionalpossibilitydistribution

π

(Y |X1,. . . ,Xn)bymeansofEq.(5).π

(

y|

x)=

max Z1,...,Zn:Z1∨···∨Zn=y∗

ni=1π

(

Zi|

xi)

=

maxn i=1π

(

zi|

xi)

∗ (∗

j6=imax(

π

(

zj|

xj),

π

(¬

zj|

xj))

=

maxn i=1π

(

zi|

xi);

π

(¬

y|

x)=

max Z1,...,Zn:Z1∨···∨Zn=¬y∗

ni=1π

(

Zi|

xi)

=

π

(¬

z1|

x1)

∗ · · · ∗

π

(¬

zn|

xn).

Note that in the second line of the computation of

π

(y|x), one must enforce Zi= y for one variable Zi, while othervariables take arbitrary values (we have n possible choices of Zi). Of coursemax(

π

(zj|xj),π

(¬zj|xj))=1 due tonor-malization. Besides, in the computation of

π

(¬y|x), the condition Z1∨ · · · ∨Zn= ¬y can be obtained for sure only ifpa(Y)= (¬z1,. . . ,¬zn).

Let I+(x)= {i:Xi=xi} and I−(x)= {i:Xi= ¬xi}.Then, if theabovecausal elementarypossibility tableis adopted,we

get:

•

π

(¬y|x)= ∗i=1,...,nπ

(¬zi|xi)= ∗i∈I+(x)κ

i;Table 2

UncertainORfor2inputs.

π(y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 1 1 ¬x2 1 0 π(¬y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 κ1∗κ2 κ2 ¬x2 κ1 1 Table 3

TheleakyuncertainORfor2inputs.

π(y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 1 1 ¬x2 1 κL π(¬y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 κ1∗κ2 κ2 ¬x2 κ1 1

•

π

(¬y| ¬x1,. . . ,¬xn)=1,π

(y| ¬x1,. . . ,¬xn)=0: ¬y (no effect) can beobtained for sureonly if allthe causes are absent.Forn =2,thisgivestheconditionalTable 2.

Moregenerally,iftherearen causes,wehavetoprovidethevaluesofn parameters

κ

i.FortheuncertainleakyOR,wenowassumethat thefunction f takestheform f(Z1,. . . ,Zn)=Wni=1Zi∨ZL,where ZL

isanunknown externalcause.Weassign

π

(zL)=κ

L<1 (hence,π

(¬zL)=1)consideringthat zL isnotausualcause.Wethus obtain

•

π

(¬y|x)= ∗i=1,...,nπ

(¬zi|xi)∗π

(¬zL)= ∗i∈I+(x)κ

i;•

π

(y|x)=1,ifx6= (¬x1,. . . ,¬xn); •π

(¬y| ¬x1,. . . ,¬xn)=1;•

π

(y| ¬x1,. . . ,¬xn)=κ

L (even if the causes xi are absent, there isstill apossibility for having Y =y,namely if theexternalcauseispresent).

Indeed, weget(letting¬x= (¬x1,. . . ,¬xn)),

π

(

y| ¬

x1, . . . ,

¬

xn)

=

max(

π

(

y| ¬

x,

zL)

∗

π

(

zL),

π

(

y| ¬

x,

¬

zL)

∗

π

(¬

zL)))

=

max(

1∗

κ

L,

0∗

1)

=

κ

L.

Forn =2,theconditionaltablebecomesTable 3.

Theonly0entryhasbeen replacedbytheleakage coefficient.Forn causes, wehavenow toprovidethevaluesofn+1

parameters

κ

i.3.3. UncertainAND

Letusconsider Booleanvariables(Y=y or¬y,etc.).TheuncertainAND(counterpartoftheprobabilistic“noisyAND”)

uses the samelocal conditionaltables but itassumes that Xi=xi represents anecessary cause for Y =y.We again build

the conditional possibility tables

π

(Y |X1,. . . ,Xn) bymeans of Eq. (5) using f(Z1,. . . ,Zn)=Vni=1Zi instead. This istheDe MorgandualtotheuncertainOR gate:

π

(

y|

x)=

max Z1,...,Zn:Z1∧···∧Zn=y∗

n i=1π

(

Zi|

xi)

=

π

(

z1|

x1)

∗ · · · ∗

π

(

zn|

xn);

π

(¬

y|

x)=

max Z1,...,Zn:Z1∧···∧Zn=¬y∗

ni=1π

(

zi|

xi)

=

maxn i=1π

(¬

zi|

xi)

∗ (∗

j6=imax(

π

(

zj|

xj),

π

(¬

zj|

xj))

=

maxn i=1π

(¬

zi|

xi).

WenoticethatVni=1Zi=y canbeobtainedonlyif pa(Y)= (z1,. . . ,zn).Thus,wefind •

π

(¬y|x1,. . . ,xn)=maxni=1π

(¬zi|xi)=maxni=1κ

i;•

π

(y|x1,. . . ,xn)=1;Table 4

UncertainANDfor2inputs.

π(y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 1 0 ¬x2 0 0 π(¬y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 max(κ1,κ2) 1 ¬x2 1 1 Table 5

LeakyuncertainANDfor2inputs.

π(y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 1 κL ¬x2 κL κL π(¬y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 max(κ1,κ2) 1 ¬x2 1 1

Forn =2,Eq.(5)yieldstheconditionaltablesfortheuncertainAND(Table 4).

Moregenerally,iftherearen causes,wehavetoassessn valuesfortheparameters

κ

i.The caseof theuncertainAND withleak correspondsto thepossibility

π

(zL)=κ

L<1 thatan external factor ZL=zLcauses Y=y independentlyofthevaluesofthe Xi.Namely f(Z1,. . . ,Zn,ZL)= (Vni=1Zi)∨ZL.Forn=2,Eq.(5)thengives

thecombined conditionalpossibilityin Table 5, similartoTable 3.Thedifference isthat theleakage coefficientappearsin

threeentriesofthematrixfor y,astheeffectisthengivenachancetoappearwhenthetwocausesarenotsimultaneously

present.

3.4. UncertainMAX

The uncertain MAX is a multiple-valued extension of the uncertain OR, where the output variable Y (hence the

variables Zi) is valued on a finite, totally ordered, severity or intensity scale L = {0<1<· · · <m}. We assume that

Y=max(Z1,. . . ,Zn).Thestatement Zi=zi∈L representsthefactthat Xi alonehas increasedthevalue ofY atlevel zi.In

thissubsection, y,zi denoteanyvaluesinL,and xi anyvalueintherangeofXi.Theelementaryconditionalpossibility

dis-tributions

π

(y|xi) aresupposed tobegiven.Wecanthencompute theconditionaltablesπ

(y|x)where x= (x1,. . . ,xn),as:

π

(

y|

x)=

max (z1,...,zn)∈Ln:y=max(z1,...,zn)∗

ni=1π

(

zi|

xi)

=

maxn i=1π

(

Zi=

y|

xi)

∗

¡∗

j6=i5(

Zj≤

y|

xj)¢ .

In a causalsetting, we assume that y=0 is anormal state (no effect), and y>0 is moreor less abnormal, y=m being

fullyabnormal(strongeffect).Suppose thattherangeof Xi is L aswell.Itisnaturaltoassumethat:

• if Xi= j then Zi= j iscompletelypossible, whichmeans5(Zi= j|Xi=j)=1;

• if Xi=0 then Zi=0,whichmeans 5(Zi6=0|Xi=0)=0 (nocause,noeffect);

• 0< 5(Zi< j|Xi=j)<1 (acause havingstrong intensitypossibly inducesaneffectwithweak severity,ormayeven

havenoeffectatall,but thisisabnormal);

• aneffectwithseverityweaker than theintensityofa causeis alltheless plausibleastheeffectisweaker. This leads

tosupposethefollowinginequalities:

π

(

Zi=

0|

Xi=

j)

≤

π

(

Zi=

1|

Xi=

j)

≤ · · · ≤

π

(

Zi=

j|

Xi=

j)

=

1;

• aneffectwithseverityhigherthan theintensity ofacause isalltheless plausibleastheeffectisstronger.This leads

tosupposethefollowinginequalities:

π

(

Zi=

m|

Xi=

j)

≤

π

(

Zi=

m−

1|

Xi=

j)

≤ · · · ≤

π

(

Zi=

j|

Xi=

j)

=

1.

This leads to state the elementary conditional table on the left-hand side of Table 6 (for 3 levels of strength 0, 1, 2),

where

κ

i02≤κ

i12.Incasewehavem levelsofstrength, wehavetoassess m(m2+1)+m(m2−1)=m2 coefficients.Therearetwointerestingspecial cases:

•

κ

21i = 5(Zi> j|Xi= j)=0: if we assume that a cause having a weakintensity cannot induceaneffect withstrong

severity;

•

κ

i21=κ

i01=1: ifweremainintotalignoranceofwhatacause havingaweakintensitycanproduce.On the right-hand side is the corresponding table when the variables Xi are Boolean (then the middle column is

Table 6

Elementaryconditionaltablesinthemany-valuedcase.

π(Zi|Xi) Xi=2 Xi=1 Xi=0 Zi=2 1 κi21 0 Zi=1 κi12 1 0 Zi=0 κi02 κi01 1 π(Zi|Xi) Xi=2 Xi=0 Zi=2 1 0 Zi=1 κi12 0 Zi=0 κi02 1

TheglobalconditionalpossibilitytablesarethenobtainedbyapplyingEq.(5),usingthevaluesof

π

(Zi|Xi),asgivenintheTable 6.

π

(

y|x)

=

maxni=1

π

(

Zi=

y|

xi)

∗ (∗

j6=i5(

Zj≤

j|

xj)).

Asabove,inthecaseoftheleakyuncertainmax,weconsidertheoutputY isoftheformmax(Z1,. . . ,Zn,ZL)where ZL

isanunknowncausethatmayaffect Y .Theexpression

π

(y|x) isnowexpressedasπ

(

y|

x)=

max (z1,...,zn,zL)∈Ln+1:y=max(z1,...,zn,zL)∗

ni=1π

(

zi|

xi)

∗

π

(

zL)

=

max(

maxni=1π

(

Zi=

y|

xi)

∗ 5(

ZL≤

y)

∗

¡∗

j6=i5(

Zj≤

y|

xj)¢ ,

π

(

ZL=

y)

∗

¡∗

ni=15(

Zi≤

y|

xi)

¢

Thepossibilitydistributionfortheleakvariableisgivenbym+1 values

π

L(i)=κ

Li,whereκ

L0=1 (itiscompletelypossiblethat theexternal causehas noeffecton Y ),and

κ

iL≥

κ

i+1L (itisallthemoreunlikelythat theexternal cause ispresentas

theobservedeffectisstrong).Undertheseassumptionstheaboveexpressions simplifysince5(ZL≤y)=1.

For n=2,m=2, the conditional Table 7 isobtained when the Xi’s are three-valued. Let us justify some expressions

appearing inthistable.1

•

π

(2|11) = max π

(Z1=2|X1=1)∗π

(Z2≤2|X2=1),π

(Z1≤2|X1=1)∗π

(Z2=2|X2=1),κ

L2∗π

(Z1≤2|X1=1)∗π

(Z2≤2|X2=1) = max(κ

21 1 ∗1,1∗κ

221,κ

L2∗1∗1)=max(κ

121,κ

221,κ

L2) •π

(1|22) = max π

(Z1=1|X1=2)∗π

(Z2≤1|X2=2),π

(Z1≤1|X1=2)∗π

(Z2=1|X2=2),κ

L1∗π

(Z1≤1|X1=2)∗π

(Z2≤1|X2=2) = max(κ

112∗κ

212,κ

212∗κ

112,κ

L1∗κ

112∗κ

212)=κ

112∗κ

212 •π

(1|21) = max π

(Z1=1|X1=2)∗π

(Z2≤1|X2=1),π

(Z1≤1|X1=2)∗π

(Z2=1|X2=1),κ

1 L∗π

(Z1≤1|X1=2)∗π

(Z2≤1|X2=1) = max(κ

112∗1,κ

112∗1,κ

L1∗κ

112∗1)=κ

112 •π

(y|00) = max π

(Z1=y|X1=0)∗π

(Z2≤y|X2=0),π

(Z1≤y|X1=0)∗π

(Z2=y|X2=0),κ

Ly∗π

(Z1≤y|X1=0)∗π

(Z2≤y|X2=0)= max(0∗1,1∗0,

κ

Ly∗1∗1)=κ

Ly if y>0 and 1 otherwise.Note that ingeneral, wecanexpectthe factthat theexternal causeis lesslikelyto producea strongeffectthan aregular

cause,sothat incolumn

π

(2|x),wemayassumeκ

L2≤min(κ

121,κ

221)so thattheleakagecoefficientshouldonly appearinthelastlineofTable 7.

Whenthe Xi’sareBoolean,wegetTable 8,whereonly4linesremain:

Moregenerally,if wehavem levelsofstrength,and n causalvariables,weneednm2coefficients fordefiningthe

uncer-tain MAX.If wetakeinto accounttheleak,wehave toadd m(m2+1) coefficients pervariable, inordertoreplacethe0bya

leak coefficientin theconditional tables

π

(Zi|Xi) (assuming that an effectofstrong severity maytake placeeven if thecauses presenthaveaweakintensity).

Table 7

UncertainleakyMAX.

x π(2|x) π(1|x) π(0|x) (2,2) 1 κ12 1 ∗κ212 κ102∗κ202 (2,1) 1 κ12 1 κ102∗κ201 (2,0) 1 κ12 1 κ102 (1,2) 1 κ12 2 κ101∗κ202 (1,1) max(κ21 1 ,κ221,κ2L) 1 κ101∗κ201 (1,0) max(κ21 1 ,κL2) 1 κ101 (0,2) 1 κ12 2 κ 02 2 (0,1) max(κ21 2 ,κL2) 1 κ201 (0,0) κ2 L κ1L 1 Table 8

UncertainMAXwithBooleaninputs.

x π(2|x) π(1|x) π(0|x) (2,2) 1 κ12 1 ∗κ212 κ102∗κ202 (2,0) 1 κ12 1 κ102 (0,2) 1 κ12 2 κ202 (0,0) κ2 L κ1L 1 Table 9

UncertainleakyMIN.

x π(2|x) π(1|x) π(0|x) (2,2) 1 max(κ112,κ212) max(κ102,κ202) (2,1) max(κ21 2 ,κL2) 1 max(κ102,κ201) (2,0) κ2 L κ112∗κ1L 1 (1,2) max(κ21 1 ,κL2) 1 max(κ101,κ202) (1,1) max(κ21 1 ∗κ221,κ2L) 1 max(κ101,κ201) (1,0) κL2 κL1 1 (0,2) κ2 L κ212∗κ1L 1 (0,1) κ2 L κL1 1 (0,0) κ2 L κL1 1 Table 10

UncertainMINwithBooleaninputs.

x π(2|x) π(1|x) π(0|x) (2,2) 1 max(κ12 1 ,κ212) max(κ102,κ202) (2,0) 0 κ12 1 1 (0,2) 0 κ12 2 1 (0,0) 0 0 1 3.5. UncertainMIN

As for the uncertain MAX wrt uncertain OR, the uncertain MIN is a multiple-valued extension of the uncertain AND,

where variables are valued on the intensity scale L= {0<1<· · · <m}. We assume that Y =max(min(Z1,. . . ,Zn),ZL),

takingintoaccountaleakvariable.Wecanthencomputetheconditionaltables,underthesameassumptionsasbefore, as

π

(

y|

x1)

=

max (z1,...,zn,zL)∈Ln+1:y=max(min(z1,...,zn),zL)(∗

ni=1π

(

zi|

xi))

∗

π

(

zL)

=

max(

maxni=1π

(

Zi=

y|

xi)

∗ 5(

ZL≤

y)

∗

¡∗

j6=i5(

Zj≥

y|

xj)¢ ,

π

(

ZL=

y)

∗

¡

maxni=15(

Zi≤

y|

xi)

¢

The conditionalpossibility tablesarethus obtained byapplyingEq. (5), usingthesamevalues of

π

(Zi|Xi),andκ

Ly asinthecaseoftheuncertainleakyMAX.Forn=2,m=2,thisgivesthefollowingconditionalTable 9forternaryinputs.

Note that theleakage coefficients are morepresent inthe leakyMIN than intheleaky MAX,even if theleakage

coef-ficients are small. This is not surprizingas it isenough to missone ofthe two causes to fail the regular effect,and the

external cause maythenemerge asthereason forsome unexpected effectinthese more numeroussituations. For binary

Table 11

Elementarycausalprobabilitytable.

P(Zi|Xi) xi ¬xi zi 1−κi 0 ¬zi κi 1 Table 12 NoisyOR. P(y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 1−κ1κ2 1−κ2 ¬x2 1−κ1 0 P(¬y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 κ1κ2 κ2 ¬x2 κ1 1

4. Comparisonwithprobabilisticgates

Itisinterestingtocomparethepossibilisticand probabilistictablesastheydonotbehaveinthesameway.The

elemen-tary probabilisticcausaltabletakesthefollowingform,where

κ

i=P(¬zi|xi) (seeTable 11).ConsidertheconditionaltableofthenoisyOR[10](Table 12),tobecomparedwiththeconditionaltableoftheuncertain

OR (Table 2).

Weshalldistinguishbetweenmin-basedand productbasedpossibilisticnetworks.

4.1. Themin-basedcase

There is an important difference between the behavior ofconditioning in the probabilistic and the possibilistic cases.

In the qualitative possibility setting, the conditional possibility 5(Y |X) isthe largest value λ such that min(λ,5(X))=

5(Y∧X),thatis

5(

Y|

X)

=

(

1 if

5(

Y∧

X)

= 5(

X);

5(

Y∧

X)

if5(

Y∧

X) < 5(

X),

and theconditional necessity is N(Y |X)=1− 5(¬Y |X). As a consequence it isimpossible to have that 5(Y)< 5(Y |

X) <1, which dually expresses the impossibility that the certainty of an event can decrease while remaining somewhat

certain (onecannot have thestrictinequality N(Y)>N(Y |X)>0)[13].The min-based conditionalpossibility framework

thus doesnotcapture theidea ofgracefuldegradation ofbelief.

Thisisastrikingdifferencewithconditionalprobabilitywherethislimitationofexpressivepowerdoesnotoccur.While

this propertyissometimes viewed asa majorimpediment to considering qualitativepossibility as areasonable

represen-tation of belief ([29] p. 265), this pessimistic view can be challenged. Note that one may simultaneously have N(y)>0

and N(y|x)=0 (and even N(¬y|x)>0), so that the qualitative framework allows for severe belief change. Moreover,

thislimitationjustindicates thatthequalitativesettingisrougherthan thequantitativeone, andthat qualitativenecessity

degreesarenotproportionaltointensityofbelief.Insomesituationsthisroughmodelissufficientforthepurposeathand,

asbeingmoreexpressivethan classicallogic(sinceitallowsfornon-monotonic reasoning[4]).

Asimilarlackofexpressiveness occurswhencomparingtheconditional possibilityand probabilitytablesincaseofthe

OR connective(Tables 2 and 12).Inthepossibilistictable,wesee(usingtheassociatednecessitymeasure N)that

N

(

y|

x1x2)

=

max(

N(

y|

x1¬x2),

N(

y| ¬

x1x2))

=

1−

min(

κ

1,

κ

2)

while

P

(

y|

x1x2)

=

1−

κ

1·

κ

2>

max(

P(

y|

x1¬x2),

P(

y| ¬

x1x2))

=

max(

1−

κ

1,

1−

κ

2),

sothatinqualitativepossibilitynetworks,theuncertainORgatedoesnotallowthereinforcementthecertaintyoftheeffect

inthepresenceoftwocauses,becauseconnectivesareidempotent.

4.2. Theproduct-basedcase

If possibility degrees are numerical and ∗= product, the conditional possibility is just defined by the usual division

(5(Y | X)= 5(5(X∧XY))), so that we can model the graceful degradation of beliefs (5(Y)< 5(Y | X)<1 may occur). The

possibilistic network thenbehaveslike aprobabilisticnetwork because N(y|x1x2)=1−

κ1

·κ2

>max(N(y|x1¬x2),N(y|¬x1x2))isalsoretrieved.

However, another major difference in behaviorbetween uncertain and noisy OR-gates will occur in casethe effects of

causes arenotfrequent (weakcauses),namelywhen P(¬zi|xi)=

κ

i>0.5,i=1,2. Thenitmayhappenthat P(y|x1x2)=Table 13

UncertainORfor2weakcauses.

π(y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 max(λ1, λ2) λ2 ¬x2 λ1 0 π(¬y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 1 1 ¬x2 1 1 Table 14

UncertainORforstrongandweakcauses.

π(y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 1 1 ¬x2 λ1 0 π(¬y|X1X2) x1 ¬x1 x2 κ2 κ2 ¬x2 1 1

make thiseffect more frequent than not. Then a possibilistic rendering of this case mustbe such that

π

(¬zi |xi)=1>π

(zi|xi)= λi.ThentheuncertainOR-gatewithtwoweakcausesbehaves asindicatedinTable 13.However,thereisnowayofobservingareversaleffect,since

π

(y|x1x2)=max(λ1∗ λ2,λ1,λ2)=max(λ1,λ2)<1.Henceπ

(¬y|x1x2)=1 and N(y|x1x2)=0.Inother words, usingtheuncertainOR, two causesthat areindividually insufficientto make an effectplausible are still insufficient to makeit plausible if joined together, because on the one hand there is

no reinforcementeffectinthiscase,andthereisno wayofproducing 1fromoperandsthatareless than 1.Note that this

fact reminds of the property of closure under conjunction for necessitymeasures in possibility theory (N(y1)>N(¬y1)

and N(y2)>N(¬y2) implyN(y1∧y2)>N(¬(y1∧y2)))whichfailtoholdinprobabilitytheory,whereareversaleffectis

possible inthiscase.

Thecasewithoneweakcauseand onestrongoneisalsoworthstudying,saycause1isweak(

π

(¬z1|x1)=1>π

(z1|x1)= λ2)andtheotherisstrong (

π

(z2|x2)=1>π

(¬z2|xi)=κ2

).Then, one observes that the strong cause alone makesthe effect somewhatcertain to thesame degreeas in the

ele-mentary causaltable,independentlyofthepresenceornotoftheweakone.Whenthestrongcause isabsent,theeffectis

absentwithaweakcertaintyasperthepresenceornotoftheweakcause.Notethat inthepossibilisticcase,weneedthe

threeTables 2,13,14thatrepresentadistinctbehavioreachcase,whiletheprobabilityTable 12isvalidinthethreecases,

whilethebelievedeffects dependonthenumericalvaluesgiveninthetable.

4.3. Shouldpossibilisticlogicalgatesbemended?

Note that insofar as the behavior of the uncertain possibilistic gates is judged counterintuitive in a given context, it

would bepossible tochange thecombinationoftheelementaryconditionaltables.For instanceonemaydefinetheglobal

conditional possibility tables

π

(Y |X1,X2) enforcingπ

(y|x1x2)>π

(¬y|x1x2) even ifπ

(y|x1)<π

(¬y|x1) andπ

(y|x2)<

π

(¬y|x2),which isperfectly compatible with possibilitytheory. However, onemay alsoclaim that thepossibilisticOR gate behaves as expected and that thesystematic cumulative behaviorof the noisy OR is questionable, dependingon

whatweintendtomodel.

Considerthecasewhen P(zi|xi)=P(¬zi|xi)=

κ

i=0.5 fori=1,2.Notethatthen P(y|x1x2)=0.75.• Interpreting

κ

i asafrequency:Thenthisresultcanbeeasilyexplained.As whencause xi ispresentirrespectiveoftheothercause,theeffect y ispresent50%oftheresults,andcausesareindependentofeachother,thiseffectisproduced

25% ofthe timewhen x1 is present and x2 isabsent, 25% of thetime when x2 ispresent and x1 is absent,and 25%

ofthe timewhen x1 and x2 are present. So no surprizethat thereinforcement effectin favor of y can beobserved.

However, the possibilistic model, due to itsmaxitive nature,cannot account for equiprobability, hence cannot model

thissituation.

• Interpreting

κ

i as adegreeofbelief: thenκ

i=0.5 representtheagent’s ignorance whether xi causes y ornot. Underthisview, the probabilistic approach produces a counterintuitive result. Indeed, it is very hard to make sense of the

reasoninglinewherebygiven that theagentignores whetherxi causes y ornot, fori=1,2,thisagent shouldbelieve

thatthepresenceofbothcausesmakestheeffect y morelikelythanitsnegation.Itisonemoreexampleofproduction

ofknowledgeoutofsheerignorance, whichisusualwhenuniformprobabilityisinterpretedaslackofinformation.

Actually,theuncertainORgate behavesconsistently withthesituation ofignorance:if itisbelievedthat eachxi causes

¬y,rather than y,thenthereisno wayofstarting to believe y when observingtwo reasonsnotto believeit.And inthe

caseofignorance,theuncertainOR-gatejustproducesignorance.

Theseresultsextend toothergates liketheuncertainMAX,forinstance. Again,thesimultaneouspresenceofanumber

of causes,which, taken inisolation, donot normally produceaneffect, maylead toaplausible effectundera noisyMAX,

whichcanneverbethecasewithanuncertainMAX.

However,inthefollowing,weareinterestedinrepresentingthesamedatasetbyprobabilisticand possibilisticnetworks

for thesakeofcomparingbothmodelsonanapplication. Thenwetrytomodifytheconstructionoftheconditional

ofcompleting thepossibilisticconditional tablesfromtheknowledgeoflocalconditionaltables5(Zi|Xi) For instancewe

mayuseanaggregationoperation⊗[2]onthepossibilityscaleanddefine5(Y |X1X2)as5(Z1|X1)⊗ 5(Z2|X2)withthe

constraint Y =Z1=Z2.However, sinceaggregationoperationsareorder-preserving andsuchthat1⊗1=1 and0⊗0=0,

wecannotaddressthecasewhenweakcausesjointomakeastrongone inthepossibilisticsettingusingthisapproach.

4.4. UncertainMAXwiththresholds

As observed in Section 4 when comparingthe uncertainOR to the noisy OR, the simultaneous presence ofa number

of causes,which, taken inisolation, donot normally produceaneffect,may lead toaplausible effectundera noisyMAX,

which can never be the case with an uncertain MAX. Yet, situations of this kind do arise in applications and are fully

compatible withtheexpressionofaconditionaltableinpossibilitytheory.

In ordertomake theconstructionofpossibility tablesin agreementwiththemutual reinforcementof weakcauses an

appropriate uncertaingate has tobedesigned, bymeans ofasuitable uncertainfunction f whichcan producethiseffect.

Oneidea wehavetestedinordertoapproximatesuchbehavioristheproposalofuncertainMAXwiththresholds.Inaddition

totheusualparametersofanuncertainMAX,thisuncertaingaterequiresthatathresholdθj bespecifiedforeachvalue yj

oftheeffectvariableY .Suchthresholdisanintegerexpressingtheminimumnumberofcausesthathavetosimultaneously

occur inorder for effect yj to become possible. To thisend, a cause Xi may beconsidered to “occur” if thevalue ofits

correspondingintermediarycausalvariable Zi differsfromthezerolevel, i.e., Zi>0.Notethatthresholdgatesalsoexistin

theprobabilisticsetting[10].

More precisely, as in the case of the uncertain MAX, we assume that the output variable Y and the variables Zi are

valued ona finite,totally ordered, severityorintensityscale L= {0<1<· · · <m}, butthefunction f describingthisgate

isbaseduponmaybewrittenas

Y

=

max(

Z1, . . . ,

Zn,

m maxi=1

{

i·

1[k{j:Zj>0}k≥θi]}),

usingtheinversonbracketnotation,whereby

1[condition]

=

(

1

,

if condition is true;

0

,

otherwise.

For instance,supposen=4,m=3,θ1=1,θ2=2,θ3=3,θ4=4.Then f(1,1,0,0)=2, f(1,1,1,0)=3, f(1,1,1,1)=4.

Wecanthenexpress theconditionaltableoftheuncertainMAXwiththresholds byapplying theextension principle,as

inthecaseoftheuncertainMAX,althoughtheresultinganalyticalexpressionismuchlesslegible:

π

f(

y|

x1, . . . ,

xn)

=

max Z1,...,Zn:y=max(Z1,...,Zn,maxmi=1{i·1[k{j:Z j>0}k≥θi]})∗

ni=1π

(

Zi|

xi)

=

maxµ

1[k{i|xi>0}k≥θy],

n max j=1π

(

Zj=

y|

xj)

∗

¡∗

j6=i5(

Zj≤

y|

xj)

¢

¶

.

More intuitively, bydefault

π

(y|x1,. . . ,xn) has thesamevalue as with theuncertain MAX,except when thenumber ofoccurringcausesexceedsthethresholdforvalue y,inwhichcase

π

(y|x1,. . . ,xn)=1.The globalconditional tablesare thenobtained byapplying Eq. (5), usingthesamevalues of

π

(Zi|Xi) asin thecaseoftheuncertainMAX.Forn=2,m=2 (i.e.,Y and the Xi’sthree-valued),θ2=2,andθ1=m+1 (i.e.,no thresholdset for

Y =1),the followingconditional Table 15is obtained.The only cellwhere possibilityis raised to1due to thethresholds

is marked by a dagger (†): the fact that two causes weakly present ((1,1)) as input cause the strongest effect with full

possibility.

Itiseasytocheckthat

π

f isless specificthanπ

MAX,whichmeansthattheimitationofthenoisyMAXisimperfect. Forinstance, one maywishtodecrease thevalue

π

(1| (1,1)) inTable 15,since thevalueπ

(2| (1,1))has been setto 1;thiswouldoccurinaprobabilisticapproachasthesumofprobabilitiesineachlineis1. However,thisisnotpossibleusingthe

definitionof f .Butweareallowed todecreasethevalue

π

(1| (1,1))manually,aslongasthemaximumofvaluesineachlineofTable 15is1.

5. Implementation

Aprototypeinvolvingtheuncertainconnectivesdefined above,allowingto executepossibilisticmodelssuchastheone

described inSection 6has been implemented in R.Here, wegive some detailsabout thepractical implementation ofthe

uncertainconnectivesdefined inthepaper.Wefocusinparticularon theuncertainMAX(and itsvariantwiththresholds),

whose implementationisnon-trivial.

ThewaytheuncertainMAXisimplementedisshowninAlgorithm 1.Theparameterprm takenasinputbythisalgorithm

maybethoughtofasrepresentingaset ofrulesoftheform

Table 15

UncertainMAXwiththresholds.

x π(2|x) π(1|x) π(0|x) (2,2) 1 max(κ12 1 ,κ212) κ102∗κ202 (2,1) 1 1 κ02 1 ∗κ201 (2,0) 1 κ12 1 κ102 (1,2) 1 1 κ01 1 ∗κ202 (1,1) 1† 1 κ01 1 ∗κ201 (1,0) κ21 1 1 κ101 (0,2) 1 κ12 2 κ202 (0,1) κ21 2 1 κ201 (0,0) 0 0 1

Algorithm1 uncertain-MAX(Y,prm). Generate a conditional possibility table for variable Y given its causes X1,. . . ,Xn

usingtheuncertainMAXwithitsgivenparametersprm.

Input: Y :theeffectvariable;

prm= {hcondi,kii}:asetofnormalizedpossibilitydistributionski= (κi1,. . . ,κikYk),maxj=1,...,kYk{κi j}=1,whichapplywhenconditioncondi holds;

condi= (hXi,xii),a(possiblyempty)pairofacausevariableXiandoneofitsvaluesxi;condi holdsifXi=xiholds;anemptyconditionalwaysholds.

Output: π(Y|X1, . . . ,Xn): a conditional possibility distribution of Y given its causes X1, . . . ,Xn.

1: π(Y|X1,. . . ,Xn)←0

2: for all x∈X1× . . . ×Xndo

3: K← {k: hcond,ki∈prm,x|=cond}{Selecttheelementarypossibilitydistributionsthatapplytox}

4: forall y= (y1,. . . ,ykKk)∈YkKk do 5: β←mini=1,...,kKk{κiyi} 6: ¯y←maxi=1,...,kKk{yi} 7: π( ¯y|x)←max{β,π( ¯y|x)} 8: end for 9: end for 10: return π(Y|X1,. . . ,Xn)

where Xi on the left-hand side is a parent variable of Y in the possibilistic graphical model, xi are one of their values,

and (

κ

i,y0,. . . ,κ

i,ym) is a normalized possibility distribution over the values of variable Y , i.e., for all y∈Y ,κ

i,y∈ [0,1],and maxy∈Y

κ

i,y=1. Note that the Xi’s in the above rules can in fact represent vectors of more elementary interactingvariables, and allow to encode multi-condition tablesnot representable bycombining simple conditional tables involving

suchvariablesinisolation.

Theleft-handsideofarulemaybeempty:inthatcase,theruleisinterpretedasifitwerestatements oftheform

Y

∼ (

κ

L,y0, . . . ,

κ

L,ym).

(8)Suchrulesmaybeusedtorepresent leakagecoefficients,whichapply toallpossiblecombinationsofcauses.

Ontheonehand,thischoiceofrepresentationoftheparametersgeneralizestheuncertaingatestothecaseof

multival-uedvariables;ontheotherhand,itallowstheexperttoexpressitsknowledgeofthephenomenoninmoreintuitiveterms,

intheformofrules,whichisentirelyinthespiritofmakingexpertknowledgeelicitationeasier.

Albeit suchrepresentation ismoreintuitive, itrequires some additionalcare: theantecedentsofthe rulesfed intothe

uncertainMAXmustcoverallpossiblecombinationsx∈X1× . . . ×Xn ofthevaluesoftheparent variablesofY inorderto

ensurethattheresultingconditionalpossibilitydistribution

π

(Y |X1,. . . ,Xn)benormalized.However,wemaynoticethat,if a leakruleof theform ofEq. (8)is given,that rulealone already covers allcombinationsofparent variable valuesand

isthus asufficientconditionforthenormalizationof

π

(Y |X1,. . . ,Xn);inthatcase,theparametersoftheuncertainMAXmaybeunderspecified.

Thealgorithmconstructsthetableofconditionalpossibilityinanincrementalway,startingwithatablefilledwithzeros

(Line 1),andthenconsideringallcombinationsofvaluesforthecause variables(Line 2).For agiven combinationx,which

corresponds toa rowofthetable,a subset K of normalizedpossibility distributionsthat apply tox is extracted fromthe

parameters (Line 3). Lines 4–8 compute one min expression ofEq. (5), byconsidering allthe combinationsof parameters

in the possibilitydistributions of K and updatethe correspondingcell (theone in the column ofthe maximum y of the

combination)if theresultofthemin exceedsitscurrentvalue, sothat, oncethisinnerloopcompleted,themax inEq. (5)

willhavebeen computedforallthecellsoftherowcorrespondingtox.

TheimplementationoftheuncertainMAXwiththresholds followsthesamepatternasthepreviousalgorithm.

6. Application

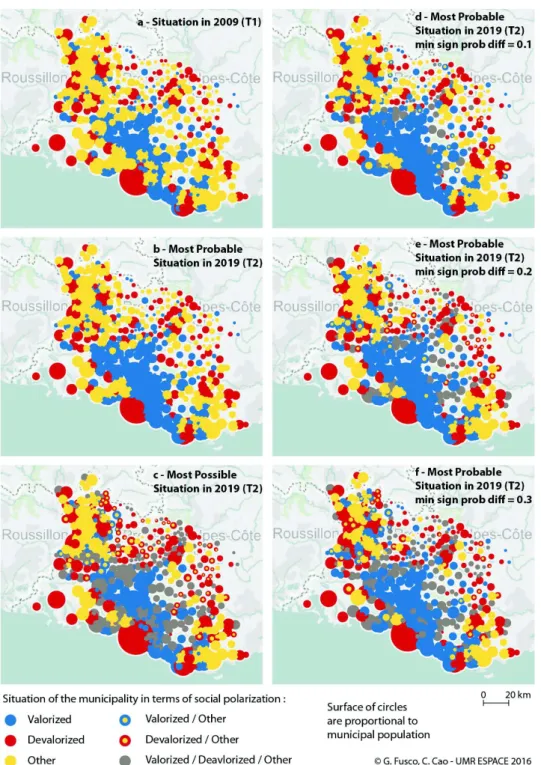

Probabilisticandpossibilisticnetworksusingnoisy/uncertainlogicalgateshavebeenusedtomodelthesocial

specializa-tionofmunicipalitiesinametropolitanarea,underahumangeographyperspective(alternativemodelshavebeenproposed

Fig. 1. The BN model for the valorization/devalorization of municipalities in the study area (adapted from[28]).

amenitiesforruralandsuburbandevelopments).Wewillfirstpresentthemodelsandtheirlogicalgates.Wewillthen

com-paretheuncertaintycontentofthetrendscenariosproducedbythetwomodelsandwewillfinallyevaluatethesensitivity

ofmodeloutcomestoprobabilisticand possibilisticelicited parameters.

6.1. Modelspecification

The metropolitanareaofAix-Marseillein southernFrance has experiencedongoingsocialpolarizationsincethe1980s.

The geographyofunemployment,on theone hand, and theconcentrationofhigh-skilled professionals,on theother,both

considerably contributetothestructuring ofacontrastedmetropolitansocialmorphology[9,17]. Theknowledgeoffactors

inducing social polarization of the municipalities in the metropolitan area is nevertheless uncertain. Social polarization

is analyzed as the opposition of valorized municipalities, hosting wealthier resident populationsand namely high-skilled

professionals, and devalorized municipalities, hosting lower-income populations and, more particularly, the unemployed.

Several factors contributeto the valorizationorto the devalorizationof themunicipal residentialspace. Butthese factors

have “soft”, uncertainimpacts on the phenomena underinvestigation: the samecauses can sometimesproduce different

effects andobservedeffectscanhavemultiplepossiblecauses.

A probabilistic model of these socio-spatial mechanisms has already been proposed [28] (cf. Fig. 1) in the form of a

Bayesiannetwork (BN).The BNwas built usingexpertknowledgeelicited through noisylogical gates(OR, AND,and MAX)

with leak parameters (takinginto account the impactof factors omitted in themodel). We then developed a min-based

possibilistic network (PN) using uncertain logical gates (OR, AND and MAX-threshold) with leak parameters in order to

link the same 26 variables of the BN. The possibilistic network has exactly the same structure as the BN model shown

in Fig. 1. The numerical parameters of the PN were made compatible with the BNparameters using a least committing

probability-to-possibilitypreferencepreservingtransformation[14]inordertotransformprobabilitydegreesintonumerical

possibilitydegrees.

Thistransformationwasused bylackofexpertdataintheformofpossibilitydistributions. WestartedwithaBayesian

network withalready existingprobabilisticdata.Itwas notpossibletostartthedatacollectionagainand trainexpertsinto

forwarding possibilitydegreesinsteadofprobability degrees.And ourintention was tocompare theresults ofpossibilistic

and probabilisticnetworks on thesamedata, which means keepingthe ordinalinformation containedinthe probabilistic

data.Usingaleastcommittedprobability-to-possibilitypreferencepreservingtransformationatthelocallevelwasanatural

way of generating such possibilistic counterparts of subjective probabilistic data, even if we are aware that making local

probability-to-possibility transforms is for instance not equivalent to making probability-to-possibility transforms of the

joint probability, asstudiedin [7]. Note that the sameissues occur whentrying to learn possibilisticnetworks fromdata

[18].

InFig. 2 weshow howanUncertainOR logical gatecanbeused togenerate aconditionalprobabilitytable. Onlythree

parameters must be elicited: the possible influence of the two parent variables on the child variable (necessity of the

consequence giventhattheparentsaresufficientcauses)andtheleakparameter,whichtakesintoaccounttheactivationof

Fig. 2. Generation of a conditional probability table through an Uncertain OR logical gate.

knowledge. If, forexample, ina given municipality ofthe study area,we are relatively certain ofthe presenceof natural

areas (5=1, N=0.5) and if it is only partially possible that agricultural areas are considered attractive and valorizing

for residentialuse(5=0.5,thisisforexample thecasefor vineyardsbut notfor industrialcrops), wecaninfer that itis

relativelycertain(N=0.5)that themunicipalityinquestionhasenvironmental amenities.

Anotherdifferencebetweenthemin-basedpossibilisticmodelandtheprobabilisticoneisthecapability,fortheformer,

of keeping track of the

κ

i parameters in the reasoning process, in order to figure out the sensitivity of results to theparametersofuncertaincausation.Theissueofsensitivityanalysisforgeneralmin-basedpossibilisticnetworksisespecially

discussedbyParsons[22](Chapters7and8).

Theadvantageofuncertainlogical gatescanbebetterappreciatedinthewholemodel(Fig. 1).Evolution is,forexample,

a ternary variable (having three values:noevolution,valorization, and devalorization) depending on 5binary variables and

one 4-valuevariable.Theconditionalprobabilitytableisthusmade of3×25×4=384 parameters,whereastheuncertain

MAX-threshold gate usedin ourPNmodelrequires atmost27 parameters(indeed only10

κ

i andθj parameters differentfrom0and1areused inourmodel).

Evolution is typically amulti-valued variable with a hierarchicalorder ofvalues. Urban geographers [28]consider that valorization is the value with highest priority: when social groups of higher purchasing power decide to live in a given

municipality,realestatepricesgo upand othersocialgroups arecrowdedout.Itcorrespondsto thehighest severityeffect

in section 3.4. The second priority effectis devalorization: when agiven set of causes operates in orderto specializethe

municipality in retaining inhabitants oflower social status,this effecthas greaterpriority (severity) than no effectat all.

Finally, theabsence of change in thesocial mix ofthe municipality is the default outcome (no effect), in the absence of

particulartriggersforvalorizationand/ordevalorization.

Thediffusion ofvalorization(i.e.,thespatialdiffusionofsuburbanand ruralgentrificationwithinthemetropolitanarea

through residentialflowsofhigh-skilled professionals)andthepresenceofassetsforrural and suburbangentrification are

triggers ofvalorizationforagiven municipality.

Theattractionofresidentialflowsofunemployedpeople(diffusion_devalorization variableinthemodel)andthepresence

of obstacles to ruraland suburbangentrification are triggers ofdevalorization. The long-terminstability ofthesocial mix

inthemunicipality overthelast20yearsanditsparticulargeographiclocationwithrespecttothesocialmixof

neighbor-ing municipalities canbe triggers ofeither valorizationordevalorization. Valorization and devalorizationare nevertheless

uncommon outcomesinthepresenceofonly one ofthesetriggering factors,asthese arenormally relativelyweak: inthe

probabilistic model, several triggers have to be simultaneouslypresent in orderto cumulate probability values and make

the absence of change less probable. Several specificationsof the uncertain MAXconnective were considered in order to

replicate asmuchaspossibletheprobabilisticbehavioroftheBNmodel.AMAX-thresholdconnectivesaturatingpossibility

valuesofuncommonoutcomeswhenthreeconcurrentcausesarepresentwasfinallyselected.

Again,asdiscussedinSection4wehavetwowaysofunderstandingtheabovesituation.Viewedintermsoffrequencies,

the reinforcement effect of the probabilities of residential moves due to several triggers, using a noisy MAX, is in line

with the actual phenomenon ofpeople changing their dwelling places, while viewed in terms of subjectiveprobabilities,

this reinforcement effectis more difficult to justify, as in this case, equal probabilities of opposite events just represent

ignorance, andnotequalproportionsofmovesinonedirectionandinanother.Thentheprobabilisticapproachsurprizingly

transformsignoranceintothepredictionofatrend,whilethepossibilisticapproachusingtheuncertainMAXwiththreshold

just increases the rangeofpossibilities,and therefore morecautiouslyincreases theimprecision ofconclusions,incase of

![Fig. 1. The BN model for the valorization/devalorization of municipalities in the study area (adapted from [28]).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/3098054.87810/14.892.70.820.106.489/fig-model-valorization-devalorization-municipalities-study-area-adapted.webp)