HAL Id: hal-03231120

https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-03231120

Submitted on 20 May 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Metal artifact reduction for intracranial projectiles on

post mortem computed tomography

N. Douis, A.S. Formery, G. Hossu, L. Martrille, M. Kolopp, P.A. Gondim

Teixeira, A. Blum

To cite this version:

N. Douis, A.S. Formery, G. Hossu, L. Martrille, M. Kolopp, et al.. Metal artifact reduction for

intracranial projectiles on post mortem computed tomography. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging,

Elsevier, 2020, 101 (3), pp.177-185. �10.1016/j.diii.2019.10.009�. �hal-03231120�

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

/Forensic

medicine

Metal

artifact

reduction

for

intracranial

projectiles

on

post

mortem

computed

tomography

N.

Douis

a,∗,

A.S.

Formery

b,

G.

Hossu

e,

L.

Martrille

c,

M.

Kolopp

d,

P.A.

Gondim

Teixeira

a,

A.

Blum

aaGuillozImagingDepartment,HopitalCentral,CHUNancy,54000Nancy,France bClaudeBernardClinic,57070Metz,France

cForensicInstitute,HospitauxdeBrabois,CHUNancy,54500Nancy,France dForensicInstitute,HopitalLaTimone,AP-HM,13005Marseille,France eLorraineUniversity,Inserm,IADI,54000Nancy,France

KEYWORDS Autopsy; Computed tomography(CT); Cadaver; Gunshotwounds; Artifacts Abstract

Purpose:To compare theimage quality ofcranial post-mortemcomputed tomography (CT)

obtainedwithandwithoutprojection-basedsingle-energymetalartifactreduction(SEMAR)in

cadaverswithintracranialmetallicballisticprojectiles.

Materialsandmethods:FromJanuary2017toJanuary2018,cadaverswithballisticprojectile

headwoundswithmetalfragmentsandwithoutmassiveheaddestructionwereinvestigated

usingpost-mortemCT.AllsubjectsunderwentCTusingaconventionaliterativereconstruction

(IR)andSEMAR.Toevaluatetheimpactofmetallicartifacts,thetotalintracranialarea(TA),

non-interpretable zone(NIZ),disturbedinterpretation zone (DZ),andartifact totalsurface

(ATS)weredelineated.Twoindependentreadersidentifiedextra-axialhemorrhage(EAH)and

subarachnoidhemorrhage(SAH).Autopsyreportswereusedasthestandardofreference.

Results:Elevencorpses(10males,1female;meanage,62.8±17.9[SD]years)wereevaluated.

SEMARshowedasignificantdecreaseintheATSratiowithrespecttoconventionalIR(72.1±26.1

[SD]%[range:26.8-99.1]vs.86.4±17.8[SD]%[range:37.2-100];P<0.001)andNIZ/TAratios

(11.6±8.26%[range:0.95—33.4]versus42.5±30.5%[range:3.86—100];P<0.001).The

inter-observerreproducibilityindiagnosingEAHandSAHwasexcellentwithconventionalIR(0.82)

andgoodwithSEMAR(0.75).SEMARreduceduncertaindiagnosesofEAHin7subjectsforReader

1andin6forReader2,butdidnotinfluencethediagnosisofSAHforeitherreader.

Conclusion:SEMARreducestheinfluenceofmetallicartifactsandincreasestheconfidencewith

whichthediagnosisofEAHcanbemadeonpost-mortemCT.

©2019Soci´et´efranc¸aisederadiologie.PublishedbyElsevierMassonSAS.Allrightsreserved.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:douisnicolas@gmail.com(N.Douis).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2019.10.009

178 N.Douisetal. Performingunenhancedpost-mortemcomputed

tomog-raphy (PMCT) has become a common practice during the forensicevaluationofdeceasedsubjects[1—3].PMCTallows subjectevaluation with no compromise tobody integrity andisparticularlyeffectiveatdetectingbonefracturesand foreignobjects, which arecrucial aspectsof the forensic investigation.Regardingballisticheadtrauma,various stud-ieshave demonstrated thatanalysis of native CT images, multiplanar reconstructions, and three dimensional (3D) volume-renderedreconstructionscouldguideandincrease theaccuracyofautopsies[4—13].Althoughentryandexit bullet wounds are best evaluatedby direct examination, PMCT can assist in the recovery of bullets and bullet fragmentsand providesa detailed evaluation of all bony structures,someofwhicharedifficulttoaccessatautopsy

[14—20].

Althoughtheexactprevalenceisunknown,thepresence ofretainedmetalfragmentsintheheadfollowinggunshot woundsis frequent. Metallicforeignbodiesarean impor-tantsourceofartifactonCT,hamperingorevenprecluding imageinterpretation. Metallicartifactsarecaused mainly by beam hardening, photon starvation, and edge profile errors[21,22].Metallicartifactsareparticularly problem-atic,asbulletscomprisedofmetals andmetalalloys with high atomic numbers are responsible of considerable CT imagedegradation.

VariousCTimagereconstructionalgorithmsdesignedto reducemetalartifactsareavailableandhelpimproveimage qualityin thepresenceof metallicprosthesesindifferent body areas [23—29]. As firearm projectiles have a differ-entcompositionthanprostheticimplants,theperformance of thesealgorithms toevaluate gunshot woundsis uncer-tain.Ananimalstudyshowedthepotentialofmetalartifact reductiontechniques(iMAR)fortheassessmentofretained bullets in the head with CT [30]. Among the techniques availablefor metalartifact reductiononCT,single-energy metalartifact reduction (SEMAR, Canon Medical Systems) withrawdatainterpolationhasbeenstudiedinpatientswith considerable improvements in image quality [31,32]. We hypothesizedthatSEMARcouldincrease theimage quality ofPMCTimagesinheadgunshotwoundvictims,improving theanalysisofcranialhemorrhagiclesions.

Thepurposeofthisstudywastocomparetheimage qual-ityofPMCTobtainedwithandwithout SEMARincadavers withintracranialmetallicballisticprojectiles.

Material

and

methods

Subjects

FromJanuary2017toJanuary2018,126subjectsunderwent PMCTinourinstitution,requestedbyamagistrateaspart of the conventional judicial procedure. Subject age, sex, andcauseofdeathwereevaluated.Amongthesesubjects, therewere29gunshotwounds,21ofwhichwerelocatedin thehead.The exclusioncriteriawere:unanalyzable cere-bralparenchyma(putrefaction,headdestruction),absence of metallic projectile fragments in the head or impossi-bilitytoselectthe CTimagescontainingasinglemetallic body,andabsenceofiterativereconstructionwithSEMAR. Five subjects with no retained metallic fragments in the

Figure1. Flowchartdiagramofincludedandexcludedcadavers.

head and five subjects with available SEMAR reconstruc-tion were excluded. Thus, the final study population was composed of 11 cadavers (10 males and 1 female), with a meanage of62.8±17.9 (standard deviation[SD]years) (range:40—93 years).Fig.1shows subjects inclusioninto thestudy.Thecauseofdeathinallincludedsubjectswas suicide by gunshotwound to thehead. In our institution, ethicscommitteeapprovalisnotrequiredforretrospective, anonymizedstudiesbasedondeceasedsubjectsrequested aspartofajudicialprocedure.

Acquisition

protocol

CTimageswereacquiredwitha320detector-rowCT scan-ner(Aquilion® One,CanonMedicalSystems).Awhole-body

acquisition wasperformed in allsubjects.The acquisition parametersforheadimagingwere:0.75stuberotationtime, 135 kVp, 450mA, 0.5mm slice thickness, FOV 24cm, and matrix512×512;foronesubject,slicethicknesswas1mm. Astandardheadreconstructionkernel(FC26)wasusedfor all reconstructions. For each study, two volumes of the head were reconstructed, one using an adaptive IR algo-rithm (AIDR3D, Canon Medical Systems)herein named as conventionalIRandanotherwithSEMAR.

Image

analysis

CTimage qualitywasassessedby aradiologist (N.D)with twoyearsofmedicalimagingexperience.OriginalCTimages of the brain in the axial plane were browsed to select images containing a single metallic fragment in order to avoidthecombinedeffectofmultiplefragmentsonimage quality. For five subjects, more than one image showing a single metallic body was available. These images were evaluatedindependently. The sameimages wereusedfor analysis with conventional IRand SEMAR reconstructions.

Figure2. DescriptionofregionofinterestplacementonCTimagesina47-year-oldmalecadaver.HeadCTimagesreconstructedwith conventionaliterativereconstruction(A)andwithsingle-energymetalartifactreduction(SEMAR)(B)werebrowsedtoselectanaxialimage showingasinglemetallicforeignbody(CandD).Ametallicprojectilefragmentlocatedadjacenttotheinnersurfaceofthetemporalbone (arrow)generatingimportantmetallicartifacts.Thetotalcranialareaisdelineatedbyacontinuousblueline,theredarearepresentsthe zonethatisnon-interpretablezone,andthegreenarearepresentsthezonedisturbedbymetalartifacts.NotethatinDthenon-interpretable zoneismuchsmallerthaninC.

Themaximumdiameterofthetargetmetallicfragmentswas measured onconventionalIRusinga widewindowsetting (C1000/W9000 HU). The influence of metallic artifactsin theevaluationofcranialhemorrhagiclesionswasevaluated usinga40/80HUwindowsettingwithbothconventionalIR andSEMARCTimagesusingthefollowingprocedure(Fig.2). Afirstfreeform regionofinterest(ROI)wasusedto delin-eate the total intra-cranial area in mm2 in the selected

slices(TA).AsecondfreeformROIwasusedtodelineatethe areainmm2completelyobscuredbymetallicartifacts

(non-interpretablezone—NIZ).Athirdfreeform ROIwasusedto delineatetheareainmm2inwhichmetallicartifactswere

present,butCTimageanalysiswasstillpossible(disturbed zone—DZ).Artifacttotalsurface(ATS)wascalculatedusing thefollowingequation:ATS=(NIZ+DZ).NIZ/TA,DZ/TA,and ATS/TAratiowerecalculatedforeachmetalfragment eval-uatedandforsubjectsconsideringallfragmentsevaluated ineachsubject.

Diagnostic performance for cerebral hemorrhage was evaluated by analyzing all CT images reconstructed with and without SEMAR.Two radiologists, with2-and 7-years ofmedicalimagingexperiencerespectively,independently evaluated PMCT images for the detection of extra-axial hemorrhage(EAH),includingepiduralhematoma(EDH)and acutesubduralhematoma(ASDH),aswellassubarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). An EDH was diagnosed when a spon-taneously hyperattenuating elliptical lesion wasobserved betweenthe cranialvault andwhen cerebralparenchyma

wasidentified. An ASDH was diagnosed when a crescent-shaped spontaneously hyperattenuating CT image was observed at the location of the subdural space. SAH was diagnosedwhenthesubarachnoidspaceandcisternswere spontaneouslyhyperattenuating[33].Thediagnostic confi-dence for hemorrhagic lesions was graded using a Likert scale(1=definitelyabsent;2=likelyabsent;3=uncertain; 4=definitelypresent;and5=notanalyzable).

The locationof the entry and exit wounds was evalu-atedonimageswithandwithoutSEMARandcorrelatedwith autopsyfindings.

Standard

of

reference

Anautopsywasperformed usinga standardizedtechnique for all included cadavers. First, the body was externally examined.Acoronalscalpincisionfromoneretro-auricular regiontotheotherwasthenperformed,followedby reced-ingof the scalpforward and backward. The cranial vault wasopened usingan electricsaw. Photographsof autopsy findingswereavailableforallsubjectsexceptone.Autopsy reportsandphotographswerereviewedretrospectivelyby aforensicphysicianwith4yearsof clinical experienceto standardize the description and nomenclature of cranial lesions.Fortheautopsywithnophotographsavailable,the initialautopsyreportwasusedbecausethedescriptionwas deemedsufficientlyclear,usingasimilarlesion nomencla-ture.

180 N.Douisetal.

Statistical

analysis

StatisticalanalysiswasperformedusingRDevelopmentCore Teamsoftware(version3.2.02015).Quantitativedatawere presentedasmean±SD(range:minimum—maximumin%). RatiosbetweenNIZ,DZ,andATS withrespect toTAwere usedtoallowinter-subjectdatacomparison.Assome sub-jects presented multiple metallic fragments, these data werepresented in aper-fragment andper -subject basis. Apaired Wilcoxon test was usedto compare the sizes of thezonesmeasured with conventionalIRand SEMAR.A P

valueless than0.05wasconsidered toindicatestatistical significance.Kappatestwasusedtoevaluateinterobserver reproducibilityforthediagnosisofintracranialhemorrhagic lesions.Kappavaluesof0.00-0.20wereconsideredto indi-catepooragreement;0.21-0.4,fair;0.41-0.60,moderate; 0.61-0.80,goodand0.81-1,excellentagreement.Autopsy reportswereusedasthestandardofreferenceforthe eval-uationofintracranialhemorrhagiclesionsandFisherexact testwasusedtoevaluatediagnosticaccuracy.

Results

Amongthe11cadavers,20CTimageswithartifactsarising fromasinglemetallicforeignbodywereidentified(meanof 1.8±1.1[SD]imagesperCTstudy[range:1-4]).Themean metallicfragmentmaximum diameterswere5.9±2.5[SD] mm(range:3.15-12.05mm).

For all subjects, no additional elements contradicting deathbysuicidewerefoundafterautopsy.Theusedweapon andammunitioncalibervaried.Theriflemodelsusedwere: three carbines 5.56×15mm R (22 long rifle), one auto-maticwithunknowncaliber,onehuntingriflewithunknown caliber,twosingleshot rifleswitha 12mm caliber.Three handgunswerealsoused:oneautomaticpistol6.35mm(.25 AutomaticColtPistol,onesingleshotpistols5.56×15mm R (22 long rifle) and one revolver 9mm (0.38 special wadcutter). There was also a modified single shot pistol 5.56×15mmR(22longrifle)caliber.Theusedammunition typewasunknown.

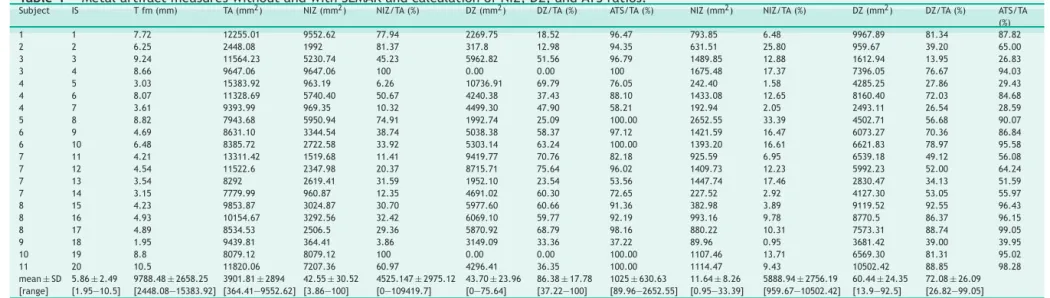

A significant decrease in mean ATS ratios per frag-ment was found with SEMAR (72.1±26.1 [SD] % [range: 26.8-99.05%]) compared to conventional IR (86.4±17.8 [SD]% [range: 37.2-100%]) (P<0.001). A similar variation was found with ATS ratios per subject with and without SEMAR (75.41±21.69 [SD] % [range: 39.95—98.28%] and 87.94±19.13 [SD] % [range: 37.22-100], respectively). A significantdecreasemeanNIZratiowasfound withSEMAR compared to conventional IR (P<0.001). The mean NIZ ratiowithandwithoutSEMARperfragmentwas11.6±8.26 [SD]%(range:0.95—33.39%)and42.5±30.5[SD]%(range: 3.86—100%),respectively,andpersubjectwas13.15±9.43 [SD] % (range: 0.95—33.39%) and 52.66±31.40% (range: 3.86-100%), respectively. No significant difference in DZ ratiosperfragmentbetweenconventionalIRandSEMARCT imageswasobserved(P=0.07).Arelativeincreaseinmean DZ ratios per fragment with SEMAR with respect to con-ventionalIRwasobserved(meanDZratiowithandwithout SEMAR60.4±24.4[SD]%[range:13.9-92.5%]and43.7±[SD] 24% [range: 0-75.64%], respectively) (Table 1). DZ ratios persubjectvariedwithandwithout SEMAR(62.29±20.88

[SD]%[range:39—89.22%]and35.01±21.0 [SD]%[range: 0—63.07%],respectively).

The interobserver variability for the diagnosis of EAH andSAHwasexcellentwithconventionalIR(Kappa=0.82, IC 95%[0.99-0.64]) andgood withSEMAR (Kappa=0.75, IC 95%[0.96-0.54]) [34]. In two subjects, the evaluation of intracranial hemorrhagic lesionswas not feasible both on imagingandonautopsyduetoheaddestruction.

Atotalof13 hemorrhagiccranial lesionswere deemed presentatautopsy,includingSAHineightsubjectsandEAH infivesubjects.Ifgrade1wasconsideredasanegative diag-nosisandgrade4asapositivediagnosis,tenoftheselesions werecorrectlydiagnosedbybothreaderswithconventional IR and SEMAR. For both readers, 100% (8/8) of the SAH werecorrectly diagnosedwhile only40% (2/5)of theEAH werecorrectlydiagnosed.Regardingdiagnosticconfidence, the numberof uncertain diagnosesdecreased withSEMAR forboth readers.Infiveandfoursubjectsrespectivelyfor Readers1and2,thediagnosticconfidenceforEAHchanged fromuncertain withconventional IRtolikely absentwith SEMAR,andintwolesionsforbothreaders,thediagnostic confidenceforEAHchangedfromlikelyabsenttodefinitely absent(Fig.3).Inallthesesubjects,anautopsyconfirmed theabsenceoftheselesions.WhenSEMARwascomparedto IR,asignificantincreaseinthediagnosticaccuracyofASDH wasfoundforReader1(P=0.012).Nosignificantdiagnostic accuracydifferenceswerefoundforEDH(P=0.175)forthis reader.ForReader2,thedifferencesindiagnosticaccuracy for EAH between SEMAR andIR werenot statistically sig-nificant(P=0.0615andP=0.175,respectivelyforEDHand ASDH).

Withboth SEMAR andconventional IR,there weretwo false-positivediagnosesofEAHfor Reader1andthreefor Reader 2, as well as one false-negative diagnosis of EAH foreachreader(Fig.4).Moreover,withSEMARCTimages, there was one additional EAH false-positive diagnosis for eachreaderandoneEAHfalsenegativeforReader2.

Thelocationoftheentryandexitwoundwascorrectly identifiedinallcaseswithbothSEMARandconventionalIR images.

Discussion

AsignificantreductioninmetalartifactinfluenceonPMCT withSEMARwasobservedcomparedwithconventionalIR, witha significantdecrease inboth ATS andNIZratios per fragment. A similar variation was seen withATS and NIZ ratiosperpatient.Theseresultsareinaccordancewith pre-viousliteraturereportsonCTmetalartifactreductioninlive patients[23,24,26,31,35—37].Inaddition,SEMAR significan-tly increased the diagnostic accuracy for aSDH compared to IR for reader 1. However, there were no significant changes in accuracy for reader 2 norfor thediagnosis of EDH for reader1, which might be explainedby thesmall sample size. The diagnostic confidence in cranial hemor-rhagiclesionidentification increasedwithalowernumber of uncertain diagnosis for both readers with SEMAR. The interobservervariability, however,wasslightly worsewith SEMAR,whichislikelyrelatedtothedecreaseinthenumber of uncertain diagnoses. Although SAH was correctly iden-tified inall subjects withboth algorithms,the number of

artifact reduction for intracranial projectiles 181

Table1 MetalartifactmeasureswithoutandwithSEMARandcalculationofNIZ,DZ,andATSratios.

Subject IS Tfm(mm) TA(mm2) NIZ(mm2) NIZ/TA(%) DZ(mm2) DZ/TA(%) ATS/TA(%) NIZ(mm2) NIZ/TA(%) DZ(mm2) DZ/TA(%) ATS/TA

(%) 1 1 7.72 12255.01 9552.62 77.94 2269.75 18.52 96.47 793.85 6.48 9967.89 81.34 87.82 2 2 6.25 2448.08 1992 81.37 317.8 12.98 94.35 631.51 25.80 959.67 39.20 65.00 3 3 9.24 11564.23 5230.74 45.23 5962.82 51.56 96.79 1489.85 12.88 1612.94 13.95 26.83 3 4 8.66 9647.06 9647.06 100 0.00 0.00 100 1675.48 17.37 7396.05 76.67 94.03 4 5 3.03 15383.92 963.19 6.26 10736.91 69.79 76.05 242.40 1.58 4285.25 27.86 29.43 4 6 8.07 11328.69 5740.40 50.67 4240.38 37.43 88.10 1433.08 12.65 8160.40 72.03 84.68 4 7 3.61 9393.99 969.35 10.32 4499.30 47.90 58.21 192.94 2.05 2493.11 26.54 28.59 5 8 8.82 7943.68 5950.94 74.91 1992.74 25.09 100.00 2652.55 33.39 4502.71 56.68 90.07 6 9 4.69 8631.10 3344.54 38.74 5038.38 58.37 97.12 1421.59 16.47 6073.27 70.36 86.84 6 10 6.48 8385.72 2722.58 33.92 5303.14 63.24 100.00 1393.20 16.61 6621.83 78.97 95.58 7 11 4.21 13311.42 1519.68 11.41 9419.77 70.76 82.18 925.59 6.95 6539.18 49.12 56.08 7 12 4.54 11522.6 2347.98 20.37 8715.71 75.64 96.02 1409.73 12.23 5992.23 52.00 64.24 7 13 3.54 8292 2619.41 31.59 1952.10 23.54 53.56 1447.74 17.46 2830.47 34.13 51.59 7 14 3.15 7779.99 960.87 12.35 4691.02 60.30 72.65 227.52 2.92 4127.30 53.05 55.97 8 15 4.23 9853.87 3024.87 30.70 5977.60 60.66 91.36 382.98 3.89 9119.52 92.55 96.43 8 16 4.93 10154.67 3292.56 32.42 6069.10 59.77 92.19 993.16 9.78 8770.5 86.37 96.15 8 17 4.89 8534.53 2506.5 29.36 5870.92 68.79 98.16 880.22 10.31 7573.31 88.74 99.05 9 18 1.95 9439.81 364.41 3.86 3149.09 33.36 37.22 89.96 0.95 3681.42 39.00 39.95 10 19 8.8 8079.12 8079.12 100 0.00 0.00 100.00 1107.46 13.71 6569.30 81.31 95.02 11 20 10.5 11820.06 7207.36 60.97 4296.41 36.35 100.00 1114.47 9.43 10502.42 88.85 98.28 mean±SD [range] 5.86±2.49 [1.95—10.5] 9788.48±2658.25 [2448.08—15383.92] 3901.81±2894 [364.41—9552.62] 42.55±30.52 [3.86—100] 4525.147±2975.12 [0—109419.7] 43.70±23.96 [0—75.64] 86.38±17.78 [37.22—100] 1025±630.63 [89.96—2652.55] 11.64±8.26 [0.95—33.39] 5888.94±2756.19 [959.67—10502.42] 60.44±24.35 [13.9—92.5] 72.08±26.09 [26.82—99.05]

IS:Selectedimages;Tfm:Metalfragmentsize;TA:Totalintracranialarea;NIZ:Non-interpretablezone;DZ:Disturbedinterpretationzone;ATS:Artifacttotalsurface;IR:Conventional iterativereconstruction;SEMAR:Single-energymetalartifactreduction.

182 N.Douisetal.

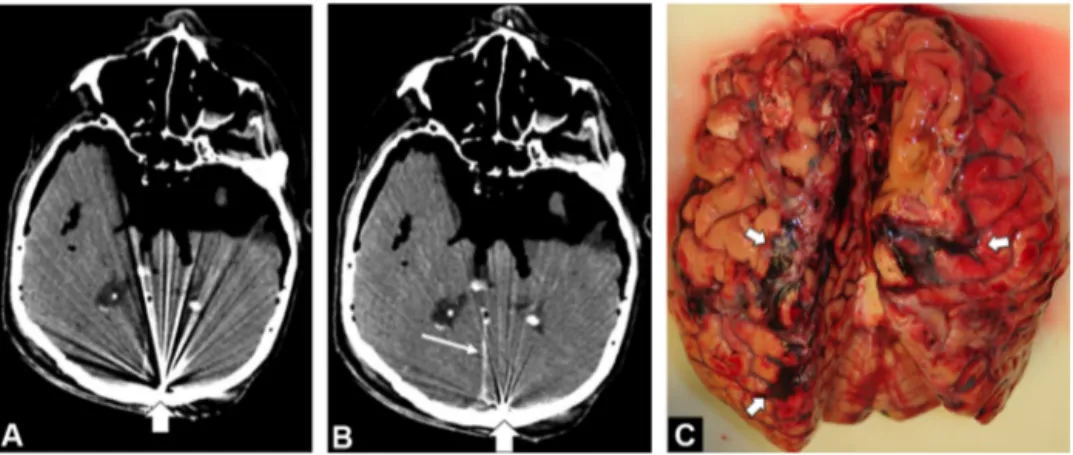

Figure3. A 67-year-old manvictim ofa headgunshotwould. A, CT imagein theaxial planeobtainedwith conventionaliterative reconstructionattheleveloftemporo-occipitallobeswithmetallicprojectileagainstinneroccipitalbone(largearrow)generatingartifacts, whichhampertheanalysisofthecerebralparenchyma.B)Axialcomputerizedtomographyimagereconstructedwithsingle-energymetal artifactreduction(SEMAR)atthesamelocationshowsmarkedreductioninmetallicartifactsenablingbetteranalysisofcerebralparenchyma andmeninges.Spontaneoushyperattenuatingareaofthefalx(thinarrow)indicativeofsubarachnoidhemorrhage(SAH)canbeseen.C) PhotographobtainedduringautopsyconfirmsvariousfociofSAH(arrows).

Figure4. A78-yearoldmanvictimofaheadgunshotwound.AandB,CTimagesintheaxialplaneobtainedwithconventionaliterative reconstructionandsingle-energymetalartifactreduction(SEMAR)respectivelydemonstrateametallicforeignbody(fatarrows). Sponta-neoushyperdensitycanbeseeninbothimages(thinarrows)andwasinterpretedasanacutesubduralhematoma(ASDH)bytworeaders. Withsingle-energymetalartifactreduction(B)andalinearimagedelineatingacrescent-shapedfluidcollectionisseenadjacenttothe skullfracture(arrowhead).Thisimagewasverydifficulttoidentifywithconventionaliterativereconstruction(arrowheadinA)andwas interpretedasanepiduralcollectionbyReader1.CandD,Photographsobtainedduringautopsyconfirmdiffusesubarachnoidhemorrhage (arrowsinC)andrightASDH(arrowinD).Theleft-sidedcrescentimageseeninBwasmisinterpretedbythereaderandcorrespondedto anASDH.

false positive andfalse negativeEAH diagnoses increased withSEMARcomparedtoconventionalIR.This observation couldbe relatedto therelative increase inthe DZratios per fragment and per patient, despite the overall reduc-tioninATS;thusindicatingthatdespiteimprovedCTimage quality, characterizingEAH in subjects withhead gunshot woundswithPMCTremainschallenging.SEMARdidnot influ-enceDZratiosperfragmentcomparedtoconventionalIR. TheseresultssuggestthatSEMARismoreeffectivein redu-cing the NIZ compared DZ. Thus, NIZ decreases as it is partiallysubstitutedby DZ,increasingtheDZ/TA ratio.As the ATS is significantly reduced with SEMAR compared to conventional IR, despite the paradoxical increase in DZ-TA ratio, the end result is an increase in the analyzable cerebralparenchymaarea.AlthoughSEMARcanbe recom-mendedtoevaluatesubjectswithgunshotheadwoundsas it improves global CTimage quality comparedto conven-tionalIR,residualartifactshinderingCTimageanalysisstill remain.

A hemorrhagic cranial lesion of anykind is relevantin forensicinvestigationsbecauseitindicatesthatthevictim wasaliveatthetimeofthegunshot.Althoughthe distinc-tion between intra or EAH is of negligible importance in forensic investigation,this informationcould beuseful to evaluate victims of non-lethal head gunshot wounds and patients with therapeutic cranial metallic foreign bodies (e.g., aneurysmcoils). Internal ballistics findingsare also paramount for head gunshot wound evaluation on PMCT. Althoughallentryandexitwoundswerecorrectlyidentified withPMCT,thesmallnumberofsubjectsandlackof stan-dardization inautopsyreports precluded bullet trajectory assessment in this study. Finally, dual-energy applications onPMCT could beused toassess metal fragment compo-sitionbased onatomicnumbers that coulddetermine the ammunitiontype[38,39].

Severallimitationsofthisstudymustbeacknowledged. First, as a retrospective study with a small number of cadavers,itdoesnotdefinitelydemonstratethesuperiority of SEMAR. Furthermore, a single metalartifact reduction algorithm was evaluated. Although other metal artifact reduction algorithms, particularly those using monochro-maticimaging, werenottested, previous studies indicate thattheperformanceofSEMARisslightlysuperiortothese algorithms[40].Also,themetalcompositionofthebullets evaluatedwasunknown,whichmayinfluencethe effective-nessofSEMAR.Furtherinvestigationiswarrantedtoassess theeffectofbulletcompositiononmetalartifactreduction. ThemeasurementsofNIZ,DZ,andTAwithafreehandROI couldleadtosmallreaderinducedvariations.Finally,only headgunshotwoundswereevaluatedinthisstudy,andthus furtherstudiesarenecessarytoassesstheefficacyofSEMAR onothertypesofmetallicforeignbodiesinotheranatomic locations.

In conclusion, SEMAR significantly improves CT image quality of PMCT cerebral parenchyma with a significant decrease in NIZ and ATS ratios. This technique leads to increased diagnostic confidence for EAH lesions allowing the identification of all SAH studied. SEMAR led to a slight decrease in interobserver agreement and did not improve the performance of the identification of EAH, which remained poor. Thus, SEMAR can be recommended fortheevaluationofheadgunshotwounds,buttherewasno

improvementinthediagnosticperformanceofintracranial hemorrhagiclesions.

Informed

consent

and

patient

details

Theauthors declarethatthis reportdoes notcontainany personalinformationthatcouldleadtotheidentificationof thesubjects.Funding

Thisworkdidnotreceive anygrantfromfundingagencies inthepublic,commercial,ornot-for-profitsectors.

Author

contributions

AllauthorsattestthattheymeetthecurrentInternational Committeeof Medical JournalEditors (ICMJE)criteria for Authorship.

Douis,Nicolas:Methodology,FormalAnalysis, Investiga-tion,validation,Writing—OriginalDraft,Writing—Review &Editing.

Formery,Anne-Sophie:Investigation.

Hossu,Gabriela:Methodology,FormalAnalysis. Martrille,Laurent:Resources,supervision. Kolopp,Martin:Methodology,Investigation.

Gondim Teixeira, Pedro Augusto: Methodology, Formal Analysis,ProjectAdministration,Validation,Writing— Orig-inalDraft,Writing—Review&Editing.

Blum, Alain: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project Administration,Validation.

Acknowledgments

WeareindebtedtoBrunoPuyssegur,JorisHoude,andValérie LamyfortheireffortsincaseselectionandCTimage recon-struction.We arealsogratefulfor thesupportofforensic institutepersonnel.

Disclosure

of

interest

The authors declare the following financial or personal relationships that could be viewed as influencing the work reportedin this paper: twoauthors involved in this work(P.A.G.T.andA.B.)participateonanon-remunerated researchcontractwithCanonMedicalsystemsforthe devel-opmentandclinicaltestingofpostprocessingtoolsforMSK CT.Theotherauthorshavenopotentialconflictsofinterest todisclose.

References

[1]DumoussetE,SouffronV,MacriF,BenSalemD,GorincourG, DedouitF.ImageriepostmortemenFrance:étatdeslieuxen 2017.JRadiolDiagnInter2017;98:225—35.

[2]ThaliMJ,YenK,SchweitzerW,VockP,BoeschC,OzdobaC, etal.Virtopsy,anewimaginghorizoninforensicpathology:

184 N.Douisetal.

virtualautopsybypostmortemmultislicecomputed tomogra-phy(MSCT)andmagneticresonanceimaging(MRI)–afeasibility study.JForensicSci2003;48:386—403.

[3]Baglivo M, Winklhofer S, Hatch GM,Ampanozi G, Thali MJ, Ruder TD. The rise of forensic and post-mortem radiology: analysisoftheliteraturebetweentheyear2000and2011.J ForensicRadiolImaging2013;1:3—9.

[4]ThaliMJ,SchweitzerW,YenK,VockP,OzdobaC,Spielvogel E, et al. Newhorizons inforensic radiology:the60-second digitalautopsy-full-bodyexaminationofagunshotvictim by multislice computed tomography. AmJForensicMed Pathol 2003;24:22—7.

[5]OehmichenM,MeissnerC.Routinetechniquesinforensic neu-ropathologyasdemonstratedbygunshotinjurytothehead. LegMedTokyoJpn2009;11:S50—3.

[6]TartaglioneT,FilogranaL,RoiatiS,GuglielmiG,ColosimoC, BonomoL.Importanceof3D-CTimaginginsingle-bullet cran-ioencephalicgunshotwounds.RadiolMed2012;117:461—70.

[7]Peschel O, Szeimies U, Vollmar C,Kirchhoff S. Postmortem 3-Dreconstructionofskull gunshotinjuries.ForensicSci Int 2013;233:45—50.

[8]BlumA,KoloppM,TeixeiraPG,StroudT,NoirtinP,Coudane H, et al. Synergistic role of newer techniques for foren-sic and postmortemCTexaminations. AJRAmJ Roentgenol 2018;211:3—10.

[9]KoloppM,BlumA,LeupoldM-A,MartrilleL.Atypicalsuicideby submachinegun.JForensicSci2018;64:629—33.

[10]JefferyAJ,RuttyGN,RobinsonC,MorganB.Computed tomog-raphyofprojectileinjuries.ClinRadiol2008;63:1160—6.

[11]BlumA,GervaiseA,TeixeiraP.Iterativereconstruction:why, howandwhen?DiagnIntervImaging2015;96:421—2.

[12]Tuchtan L, Gorincour G, Kolopp M, Massiani P, Léonetti G, Piercecchi-MartiMD,et al.Combineduseofpostmortem3D computed tomography reconstructions and 3D-design soft-ware forpostmortemballisticanalysis.DiagnIntervImaging 2017;98:809—12.

[13]GaretierM,DeloireL,DédouitF,DumoussetE,SaccardyC,Ben SalemD.Postmortemcomputedtomographyfindingsinsuicide victims.DiagnIntervImaging2017;98:101—12.

[14]DiMaioVJM.Anintroductiontotheclassificationofgunshot wounds.In:Gunshotwounds:practicalaspectsoffirearms, bal-listics,andforensictechniques.2ndEditionCRCPress;1998. p.64—121.

[15]ThaliMJ,Viner MD,Brogdon BG. Forensicradiology of gun-shotwound,newdevelopmentsingunshotinjury.In:Brogdon’s ForensicRadiology.SecondEditionCRCPress;2011.p.211—52.

[16]LevyAD,HarckeHT.Gunshotwounds.In:EssentialsofForensic Imaging.CRCPress;2011.p.53—95.

[17]Makhlouf F, Scolan V, Ferretti G, Stahl C, Paysant F. Gun-shotfatalities:correlationbetween post-mortem multi-slice computedtomographyandautopsyfindings:a30-months ret-rospectivestudy.LegMedTokyoJpn2013;15:145—8.

[18]OehmichenM,MeissnerC,KönigHG,GehlH-B.Gunshotinjuries to theheadandbraincausedbylow-velocityhandgunsand rifles:areview.ForensicSciInt2004;146:111—20.

[19]VerhoffMA,KargerB,RamsthalerF,ObertM.Investigationson anisolatedskullwithgunshotwoundsusingflat-panelCT.IntJ LegalMed2008;122:441—5.

[20]VielG,GehlA,SperhakeJP.Intersectingfracturesoftheskull andgunshotwounds:casereportandliteraturereview. Foren-sicSciMedPathol2009;5:22—7.

[21]BarrettJF,KeatN.ArtifactsinCT:recognitionandavoidance. Radiographics2004;24:1679—91.

[22]Boas FE, FleischmannD. CTartifacts:causes and reduction techniques.ImagingMed2012;4:229—40.

[23]Sonoda A, Nitta N, Ushio N,Nagatani Y, OkumuraN, Otani H, et al. Evaluation of the quality of CT images acquired with the single energy metal artifact reduction (SEMAR)

algorithm in patients with hip and dental prostheses and aneurysmembolizationcoils.JpnJRadiol2015;33:710—6.

[24]YasakaK,KamiyaK,IrieR,MaedaE,SatoJ,OhtomoK.Metal artefactreduction for patients with metallic dental fillings inhelical neckcomputed tomography:comparison of adap-tiveiterativedosereduction3D(AIDR3D),forward-projected model-basediterativereconstructionsolution(FIRST)andAIDR 3Dwithsingle-energymetalartefactreduction(SEMAR).Dento MaxilloFacialRadiol2016;45:20160114.

[25]BierG,BongersMN,HempelJ-M,ÖrgelA,HauserT-K, Erne-mann U, et al. Follow-up CT and CT angiography after intracranial aneurysm clipping and coiling-improved image qualitybyiterativemetalartifactreduction.Neuroradiology 2017;59:649—54.

[26]KidohM,UtsunomiyaD,IkedaO,TamuraY,OdaS,FunamaY, etal.Reductionofmetalliccoilartefactsincomputed tomog-raphy body imaging: effects of a new single-energy metal artefactreductionalgorithm.EurRadiol2016;26:1378—86.

[27]Pjontek R, Önenköprülü B, Scholz B, Kyriakou Y, Schubert GA,NikoubashmanO,etal.Metalartifactreductionfor flat paneldetector intravenousCT angiographyin patientswith intracranialmetallicimplantsafterendovascularandsurgical treatment.JNeurointerventionalSurg2016;8:824—9.

[28]Chintalapani G, Chinnadurai P, SrinivasanV, ChenSR, Shal-toniH,MorsiH,etal.EvaluationofC-armCTmetalartifact reductionalgorithmduringintra-aneurysmalcoilembolization: assessmentofbrainparenchyma,stentsandflow-diverters.Eur JRadiol2016;85:1312—21.

[29]Blum A, Gondim-Teixeira P, GabiacheE, Roche O, Sirveaux F,OlivierP,etal.Developmentsinimagingmethodsusedin hiparthroplasty:adiagnosticalgorithm.DiagnIntervImaging 2016;97:735—47.

[30]Berger F, Niemann T, Kubik-Huch RA, Richter H, Thali MJ, GaschoD.Retainedbulletsintheheadoncomputed tomog-raphy-Getthemostoutofiterativemetalartifactreduction. EurJRadiol2018;103:124—30.

[31]Gondim Teixeira PA, Meyer J-B, Baumann C, Raymond A, SirveauxF,CoudaneH,etal.TotalhipprosthesisCTwith single-energyprojection-basedmetallicartifactreduction:impacton thevisualization ofspecific periprostheticsoft tissue struc-tures.SkeletalRadiol2014;43:1237—46.

[32]ChangYB, XuD,ZamyatinAA.Metalartifact reduction algo-rithm for singleenergy and dualenergy CTscans. 2012. p. 3426—9[2012IEEENucl.Sci.Symp.Med.ImagingConf.Rec. NSSMIC].

[33]OsbornAG,BlaserSI,SalzmanKL.DiagnosticImaging:Brain. SaltLakeCity:WBSaundersCoLtd;2004.

[34]BlumA,FeldmannL,BreslerF,JouannyP,Brianc¸onS,RégentD. Valueofcalculationofthekappacoefficientintheevaluation ofanimagingmethod.JRadiol1995;76:441—3.

[35]ShiraishiY,YamadaY,TanakaT,EriguchiT,NishimuraS,Yoshida K, et al. Single-energy metal artifact reduction in postim-plant computed tomography for I-125 prostate brachyther-apy: impact on seedidentification. Brachytherapy 2016;15: 768—73.

[36]PanY-N,ChenG,LiA-J,ChenZ-Q,GaoX,HuangY,etal. Reduc-tion ofmetallic artifactsof thepost-treatment Intracranial aneurysms:effectsofsingleenergymetalartifactreduction algorithm.ClinNeuroradiol2017.

[37]RagusiMAAD, van derMeer RW,Joemai RMS,vanSchaik J, vanRijswijkCSP.EvaluationofCTangiographyimagequality acquiredwithsingle-energymetalartifactreduction(SEMAR) algorithminpatientsaftercomplexendovascularaorticRepair. CardiovascInterventRadiol2018;41:323—9.

[38]GaschoD,ZoelchN,RichterH,BuehlmannA,WyssP,Schaerli S.Identificationofbulletsbasedontheirmetalliccomponents andX-rayattenuationcharacteristicsatdifferentenergylevels onCT.AJRAmJRoentgenol2019;213:1—9.

[39] WinklhoferS,StolzmannP,MeierA,SchweitzerW,MorsbachF, FlachP,etal.Addedvalueofdual-energy computed tomog-raphyversussingle-energycomputedtomographyinassessing ferromagneticpropertiesofballisticprojectiles:implications for magnetic resonance imaging of gunshot victims. Invest Radiol2014;49:431—7.

[40]BolstadK,FlatabøS,AadnevikD,DalehaugI,VettiN.Metal artifact reduction in CT, a phantom study: subjective and objectiveevaluationoffourcommercialmetalartifact reduc-tionalgorithmswhenusedonthreedifferentorthopedicmetal implants.ActaRadiol19872018;59:1110—8.