Manuscripts Imitating Printed Books:

Bibliographic Codes and Peritexts in

Finnish Juvenalia from the Turn of the

20

th

Century

1

Veijo Pulkkinen

Résumé

Cet article analyse l’imitation des codes bibliographiques et des péritextes des livres imprimés dans la production de livres faits main par des auteurs débutants en Finlande de la fin du 19e siècle aux années 1920. Dans le cas d’auteurs tels que Helka Hiisku (1912–1962), Elina Vaara (1903–1980), Katri Vala (1901–1944) et Yrjö Koskelainen (1885–1951), ces livres n’étaient probablement pas faits en vue d’être publiés ou édités au sens traditionnel du terme, mais étaient destinés à une circulation plus étroite, dans un cercle limité à la famille et aux amis. L’examen attentif de la manière dont ces livres manuscrits copiaient le livre imprimé (contenu, pseudonymes, illustrations, couvertures, pages de titre, typographie), montre à quel point le concept du « livre » influait sur l’écriture en général dans la première moitié du 20e siècle. Les livres faits main avaient beau être une manière de passe-temps, ils n’en révèlent pas moins combien les jeunes auteurs étaient familiers des codes bibliographiques et péritextuels du livre imprimé.

Abstract

The present article examines the imitation of the bibliographic codes and peritexts of printed books in numerous Finnish juvenilia manuscript books from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s. These meticulously crafted books by Helka Hiisku (1912–1962), Elina Vaara (1903–1980), Katri Vala (1901–1944) and Yrjö Koskelainen (1885–1951) were probably not intended to be printed or published in the traditional sense but have most likely circulated among an extremely limited readership of friends and family. An investigation of the imitation of printed books in relation to content, pseudonyms and the publisher’s peritext, such as illustration, book covers, title pages and typography, shows how thoroughly the concept of the book determined writing in the first half of the 20th century. Handmade books might have been a hobby activity but they also demonstrate how aware budding writers were of the bibliographical code and peritexts of the printed book.

Keywords

juvenilia; manuscripts; bibliographic code; peritext; imitation

1 This work was supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation (project number 00160791) and the Alfred Kordelin Foundation (project

The present article examines the imitation of the bibliographic codes and peritexts of printed books in numerous Finnish juvenilia manuscripts from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s. The research materials consist of handmade books by Finnish authors Helka Hiisku (1912–1962), Elina Vaara (1903–1980), Katri Vala (1901–1944), and Yrjö Koskelainen (1885–1951). The material is deposited in the Literature and Cultural History Collection of the Archive of the Finnish Literature Society in Helsinki (= SKS KIA). These meticulously crafted books or booklets were made in their authors’ adolescence and they were probably not intended to be printed or published in the traditional sense but have most likely circulated within an extremely limited readership of friends and family.

The handmade books are connected to a wider manuscript culture that was still vigorous in Finland in the late 19th and early 20th century. Handmade magazines were an especially popular medium in schools,

students’, youth and workers’ associations. They were often produced in collaboration among several people writing, editing and fair copying the texts. Usually, only one copy of each number of a magazine was produced, which was published by reading it out in a convention. Handmade magazines offered a vehicle for juvenile writers to develop their writing skills and analyse and express their experiences and feelings. The oral literary manuscript culture was also a part of family traditions where handmade magazines, letters, greeting poems and collectively held diaries were read aloud in festivities (Kemppainen, Salmi-Niklander & Tuomaala 2011, 10–11; Salmi-Niklander 2004, 42, 131–132, 447; 2011, 21, 34; Tikka 2011, 73–74). From my examples, at least Hiisku, Vala and Koskelainen are also known to have made handmade family magazines (Majamaa 1987, 134; Yrjö Koskelainen Archive, Box 1, SKS KIA). Handmade magazines often imitated printed magazines with their layout, decoration and lettered titles. However, within the limits of this article, it is not possible to do justice to this rich research material, which is why I focus on handmade books.

Until recently, juvenilia have been an underrated research object, often referred to only if directly related to the author’s mature work or somehow elucidated his or her biography. However, as Christine Alexander and Juliet McMaster have stated in their co-edited volume, The Child Writer from Austen to Woolf (2005), juvenilia can also be studied in its own right, almost as if it were a literary genre. They define juvenilia as works by writers up to twenty years of age, no matter what genre they belong to: letters, poetry, novels or family magazines (Alexander and McMasters 2005, 1–3). A similar definition was suggested in the anthology of juvenile manuscripts of the Archive of the Finnish Literature Society Enteitä ja uhmaa: kirjailijan nuoruus (1987, Omens and Defiance: The Youth of an Author) where the age range was set at ten to twenty years (Majamaa 1987, 5).

Following Alexander and McMaster, I will approach juvenilia more as a genre, comparing manuscripts by different authors, rather than studying them against their authors’ later careers. Some articles in The Child Writer from Austen to Woolf touch upon the apparent imitation of the visual and formal features of printed magazines and books in juvenilia (e.g., Alexander 2005b, 18–19, 21; 2005c, 34–35). In the following, I will focus on this phenomenon and analyse it within the conceptual framework of bibliographic codes and peritexts.

The concept of the bibliographical code, coined by Jerome J. McGann, refers to the socio-historical context and “material” means of production of a work, such as the binding of a book, its size, quality of ink and paper, typography and illustration (McGann 1991, 12–15, 56–62). A related term is Gerard Genette’s peritext that is a part of the paratext of a literary work, which is a set of threshold texts that frame the proper text of

the work. Genette divides the paratext into two types of text. The first is the epitext, which is composed of materials that are related to the text but not attached to the publication, like interviews or book reviews. The other is the peritext, which is directly attached to the publication. It includes features, such as, typography, the name of the author, titles, prefaces and notes (Genette 1997a, 5–6). The basic difference between the bibliographic code and the peritext is that the former is concerned with almost everything about the work except its textual content or what McGann calls the linguistic code, whereas the peritext include linguistic elements, such as the content of the preface.

In what follows, I will begin with a brief theoretical inspection of the concepts of ubique and unique in the context of bibliographical codes. A fair amount of the charm of these handmade books derives from the play between the unique and ubique. By imitating the bibliographic code and peritexts of printed books, juvenilia books bring many features associated with the ubique printed book into the realm of the unique manuscripts, challenging conceptual distinctions between manuscript and print and producing an intriguing combination of both. Next, I examine a related phenomenon of imitation of printed books in fair copies that in many cases are also used as printer’s copies. In principle, imitation in these manuscripts has a different function than in the juvenilia handmade books since they are supposed to be prototypes of future printed books. In the rest of the article, I focus on the juvenile handmade books by investigating the imitation of printed books in relation to content, pseudonyms and the publisher’s peritext, such as, illustration, book covers, title pages and typography.

The handmade juvenilia books show how thoroughly the concept of the book determined writing in the late 19th and the early 20th century. To be precise, this concept or conception of the book was based on the

contemporary, mostly mechanically produced codex form of the book that the readers and writers were accustomed to.2 The sort of “Do-It-Yourself” books may have been a hobby activity but they nevertheless demonstrate how aware budding writers were of the bibliographical codes and the peritexts of the printed publications. Moreover, these juvenilia manuscripts recognise text as a visual entity that also brings forth the “material” side of the literary work.

The ubique and the unique bibliographic code

Materiality is a tricky concept when applied to the literary work. Bibliographic codes such as typography are often referred to as the material dimension of a literary work (e. g., Bornstein and Tinkle 1998, 1; Gutjahr and Benton 2001, 4; McGann 1991,12, 56–57; Moylan and Stiles 1996, 2). This is usually done in contrast with the text or the content of the work, understood as a more abstract or transcendent entity that can be reproduced in quantities; thus, it is not identical with any particular physical manifestation. In McGann’s terminology, this is the linguistic code of the work (McGann 1991, 57). The nature of the bibliographical code is, however, somewhat more complex than a simple juxtaposition between an abstract linguistic code and a material bibliographic code. To more fully appreciate what is taking place in the imitation of printed books in the juvenile manuscripts we must examine the ubiquity of the bibliographical code.

2 That concept is considerably different than, for instance the notion of the book in the eve of print when skilfully written a nd

luxuriously decorated and illuminated manuscript books defined the ideal book. They served as the model for the early printed books known as incunabula. The printed book thus begun by imitating manuscripts. From a typographical perspective, the imitation of manuscripts has never seized in the sense that typographers have taken cue from handwriting throughout history, which is not to say that they have also designed typefaces that deliberately avoid it.

A common definition of ubiquity is presence everywhere or in many places especially simultaneously (Oxford English Dictionary 2018). Here, I am leaning on the latter meaning. In philosophy of art, artworks are often distinguished into two main categories according to their ontological nature. Works like paintings and sculptures are considered identical with their physical manifestation in the sense that they cease to exist when the material object perishes. In other words, these works are unique objects. Another kind of artwork is one that is not identical with any particular material object but may exist simultaneously in many manifestations, like the text of a literary work that exists in multiple copies of an edition (e.g., Genette 1997b, 24–25; Goodman 1985, 112–117, 120–122; Wollheim 2000, 5–7, 79–80). In this sense, a literary work is ubique.

Usually the ubiquity of a literary work is restricted to its text, i.e., its linguistic code but in the case of printed books, many bibliographical codes, such as size, illustration, decoration, typography and quality of ink and paper are reproducible as well. They are printed essentially the same in every copy of an edition. Thus, some of the bibliographic codes of printed books can be considered ubiquitous in the sense that they can exist simultaneously in several places.

The case is quite the opposite with a manuscript, which as a physical object is a unique autographic object. Although its text can be copied and a facsimile may reproduce many of its visual and formal properties, its production history can never be repeated. Like a painting, a manuscript cannot be reproduced without losing its authenticity. In other words, a manuscript is identical with its physical manifestation. This holds true for its bibliographical codes as well.

In the context of the turn of the 20th century book culture, manuscripts can be divided into at least three categories according to the functions of their bibliographic codes. These functions can overlap. Firstly, the bibliographic codes may only be related to the document in question, which is a function that all bibliographic codes have by default. Secondly, a manuscript may be a sort of prototype or model for a printed book; for example, the layout of a poem on the manuscript page shows the typesetter how to set the lines. In a sense, the typesetter imitates the manuscript in producing the printed book. Thirdly, the bibliographic codes may directly imitate printed books, as in copying an existing book or imitating the common features of printed books.

Imitation in fair copies

A phenomenon related to the imitation of printed books in juvenilia manuscripts is the modelling of a coming printed book. Basically, authors only need to provide the text of the book and the print house will take care of its design but in many cases their manuscripts contain features that are related to the bibliographic codes of the coming book. Some of these features are intended as directions for the typesetter but some are there often just for the author. The main difference between handmade juvenilia books and the manuscripts that model printed books is that the former is the end-product and the latter is not.

A quite common feature of manuscripts modelling the coming printed book is the cutting of the manuscript paper into the size of a book page. This habit occurs especially among Finnish authors of the first half of the

20th century who used typewriters, such as Jalmari Finne (1874–1938); Arvi Järventaus (1883–1939); Irja Salla (1912–1966) and Unto Seppänen (1904–1955). A probable reason for this was to help estimate how many pages the manuscript would be in print. Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934), for instance, once used oversized paper while he had his novel Punainen mies (1928, The Red Man) typed up and he sent a page of the manuscript to his publisher asking how many pages it would make in print (Lehtonen 1983, 324).3 The point

in cutting the paper to book size is not exactly to provide a model of the book for the typesetter, maker-up, or the binder of the book but rather for the author. By imitating the book page size, the author receives the direct feedback of how much printed text he or she produces while writing. In this way, the form of the book quite tangibly guides the production of literature. Another reason for cutting the sheets to book page size could be the simulation of the future reader’s reading experience. This is especially important in the case of poetry, where the layout (line breaks, empty lines, indentation and white space) often contributes to the poem’s production of meaning.

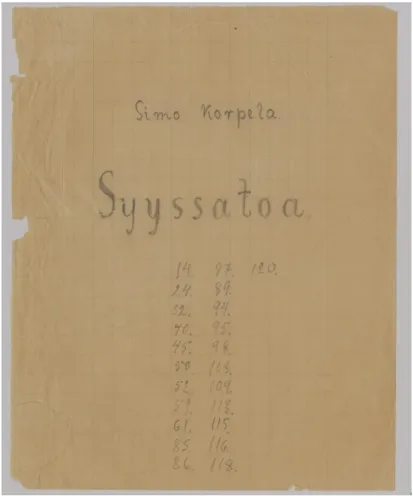

Fig 1: The cover page of the manuscript of Syyssatoa by Simo Korpela. SKS KIA.

Other features of imitating the coming book include the decoration or illustration of title pages and careful layout of the text. The next two examples are actually manuscripts of unpublished works. However, there are signs that suggest that they were aimed to be published. The first one is a collection of hymnodies titled Syyssatoa (Autumn Harvest) by the dean and hymnist Simo Korpela (1863–1936) (Simo Korpela Archive.

3 Another example is Mika Waltari, who in a letter to his father’s friend Jalo Sihtola, estimated the length of the novel he wa s

planning by comparing the size of his manuscript pages to book pages: “Olen harkinnut sitä ‘suurteosta’. Se voisi olla noin 180

kirjansivun paikkeilla eli minun tällaisia arkkejani noin 260” (I have thought about that ’major work’. It could be about 180 book

Box 1, SKS KIA). The manuscript is not dated but the fact that the text is typewritten suggests that it is a much later work. Korpela used to finish his manuscripts in ink at least until 1927.4 In many other respects, the manuscript of Syyssatoa is like those of his published works. The paper is cut to book size; if a hymn does not fit onto one page, it continues on the verso side of the leaf (a rare feat in manuscripts); the hymns are carefully laid out on the pages with the help of the gridded paper. In Syyssatoa, the hymns are written with a typewriter, neatly centred on the page. The titles of the hymns are typed but the titles of the sections and the title page are lettered in pencil with highly stylized characters (Figure 1).

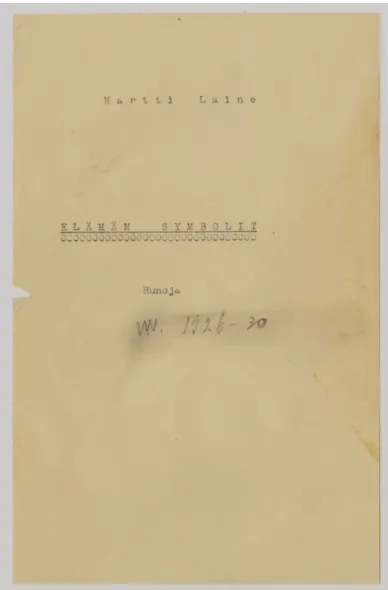

The other example comes from Martti Larni (1909–1993). It is a collection of poetry of 1926–1930 titled Elämän symbolit (The Symbols of Life) (Martti Larni Archive, Box 3, SKS KIA). The collection was probably prepared for publication in the early 1930s. The manuscript is written with a typewriter on paper cut to book size. The title page is especially interesting because Larni has used the typewriter to decorate it (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: The cover page of the manuscript of Elämän symbolit by Martti Larni. SKS KIA.

On the top of the page is the author’s birth name Martti Laine emphasized with letter-spacing.5 In the middle

of the page is the title of the collection with letter-spaced, upper-case characters. The title is underlined and directly under the line there is a row of zeros or the letter ‘O’. A little further below is the genre indication Runoja (Poems). There is a similar title page in Larni’s unpublished collection of short stories Mies, joka nauroi kuolema sydämessä from 1927 (The Man Who Laughed with Death in His Heart. Martti Larni Archive, Box 2, SKS KIA). The text pages imitate printed volumes with carefully laid out lines and centred page numbers amidst two hyphens. A remarkable detail is the upper-case titles of the poems, which are aligned to the right. At the time, titles were normally either aligned to the left or centred. A probable model for this decision is the collection of poetry Valtatiet (1928; High Ways) by Mika Waltari (1908–1979) and Olavi Lauri aka Olavi Paavolainen (1903–1964); they were central figures of the group of Finnish modernists called Tulenkantajat (Torch Bearers). The typography of Valtatiet resembles that of The New Typography movement of the 1920s with the use of lines and sans-serif typefaces (Pulkkinen 2017, 210–213). Larni’s interest in modernism is also reflected in the short story titled “Kappale elämän filmiä”, which is about a writer who becomes mad after writing a Dadaist poem. The story comes from the unpublished collection Mies, joka nauroi kuolema sydämessään.

Imitation and pseudonyms

According to Alexander, imitation in juvenilia involves “the reworking of and experimentation with an original (rather than simply copying)” (Alexander 2005b, 17). Imitation is not always negative like plagiarism but can also be seen as a creative process like following an example and trying to do something similar to what someone else has done. To develop one’s own style, all writers begin by imitating others’ styles, trying out different modes and narrative voices (Alexander 2005a, 77). The contemporary epistolary and sentimental novels, for instance, served as a model for the young Jane Austen and in her early efforts Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot) took her cues from Walter Scott and G.P.R. James (Alexander 2005b, 17).

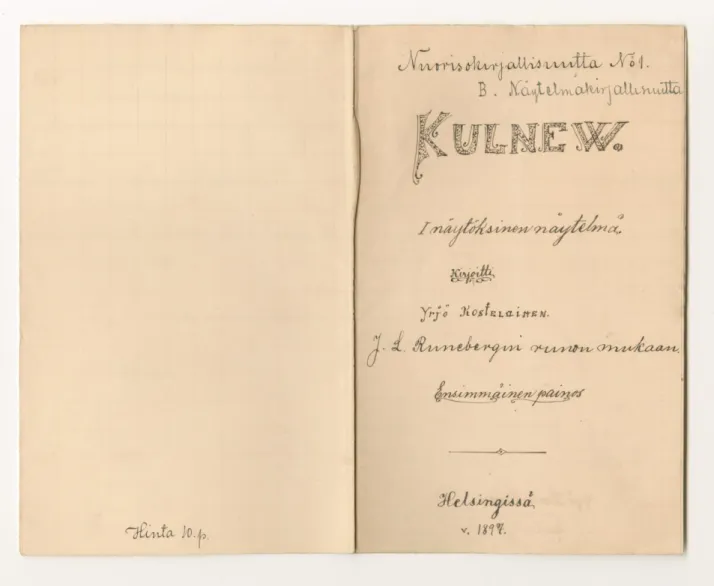

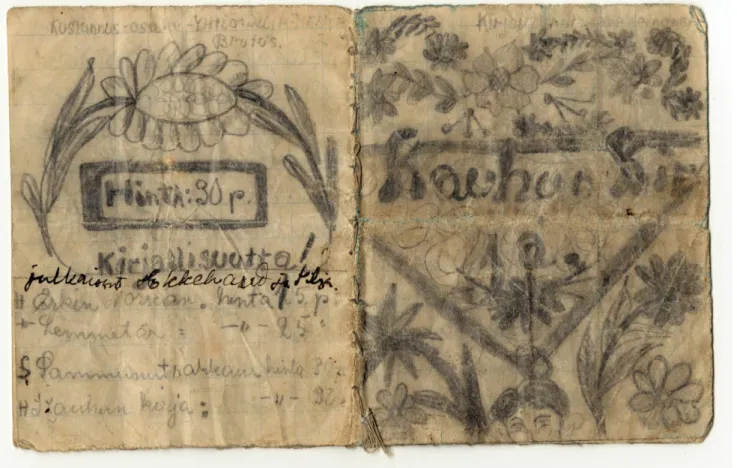

An interesting case of this kind of imitation at the content level is a homemade booklet titled Kulnew (1897) by Yrjö Koskelainen (Yrjö Koskelainen Archive, Box 1, SKS KIA) (Figure 3). Koskelainen was an author, journalist, member of the parliament, and vice president of the Finnish Industrial Union (Muiluvuori 2000). However, when he made this homemade book, he was just a schoolboy 12 years of age. In all there are 14 homemade books and magazines of this kind by Koskelainen in the Archive of the Finnish Literature Society. Kulnew is a short play based on the poem “Kulneff” by the national poet of Finland Johan Ludvig Runeberg (1804–1877). The poem is included in the first volume of Runeberg’s magnum opus Fänrik Ståls sägner (1848 and 1860, The Tales of Ensign Stål [1938]. Translated by Charles Wharton Stork), which is an epic poem written in Swedish that depicts the events of the Finnish War (1808–1809). The epic consists of separate poems bound together with a frame story of a young secondary school graduate who gets to know the old ensign Stål who tells him stories from the war. The poem “Kulneff” is about the Russian general Yakov Kulnev (1763–1812) whom Runeberg describes in a very sympathetic fashion as a war hero who loved wine and women.

5 Martti Laine changed his last name to Larni partly because the sensation caused by his novel Kuilu: kertomus eräästä

ihmiskohtalosta (The Abyss: The Story of a Man’s Fate, 1937) for its naturalist representation of brutal violence and homosexuality

Fig 3: The back and front cover pages of the handmade book Kulnew by Yrjö Koskelainen. SKS KIA.

Like Fänrik Ståls sägner, Koskelainen’s play has a frame story. It is about a group of young men who are gathered together around a campfire to drink beer and listen to the war stories of the old corporal Rajanen. Moreover, the text of the story of Kulnev that Rajanen tells is a direct citation of Paavo Cajander’s (1846– 1913) Finnish translation of Runeberg’s epic Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat (1889). The young men interrupt the story with comments all the while, comparing, for instance, the events with their own lives. Thus, Koskelainen, tangibly adopts the text of his author/idol and makes it his own. Nevertheless, he does it without falling into plagiarism. The title page of Koskelainen’s play acknowledges that the play is based on Runeberg’s poem and in the text the source text is carefully separated with indentation from Koskelainen’s own text.

In addition to using another work as a model, an author may also use pseudonyms in a way of imitation in juvenilia that concerns the content level as well as the peritext. Genette observes that the use of pseudonyms is particularly popular in literature and theatre, including popular culture and suggests that it reflects “a taste for masks and mirrors” and a “delight in invention” and “borrowing” (Genette 1997a, 53–54). It is not a surprise, then, that the name of the author can turn into a source for imitation in juvenile handmade books, especially, in early twentieth-century Finland, when several prominent figures changed their Swedish names to Finnish names and many authors used pen names instead of their legal names. In general, the use of

pseudonyms was a commonplace in Finnish literary culture at the turn of the 20th century (Grönstrand 2006; Sarjala 1994).

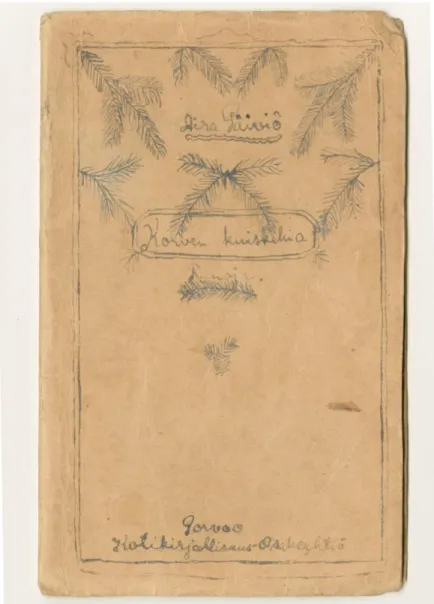

Two of my examples of homemade juvenilia manuscripts are signed with pseudonyms. The first one is a homemade book called Korven kuiskehia (1918, Woodland Whispers) by Aira Päiviö, better known as the poet and teacher Katri Vala (née Karin Alice Wadenström) (Katri Vala Archive, A 2819, SKS KIA) (Figure 4). She was a member of the modernist literary group Tulenkantajat (torch bearers) in the late 1920s and later in the leftist cultural group Kiila (Wedge). By the time Vala wrote Korven kuiskehia, she had already published some poems, which are not included in the homemade book. She has stated that she began writing poetry at the age of eleven but none of this early material has survived (Saarenheimo 1984, 24.) Vala is known as a pioneer of Finnish free verse poetry, the examples of which are also present in the homemade book. However, Vala also experiments with metrical poetry such as the Kalevala meter. There does not seem to be any apparent motive behind the chosen pseudonym. Thematically, the poems depict a withdrawal to the woods and are mostly quite gloomy; that is, they are somewhat in contrast to the name Päiviö, which is a Finnish male name that was probably derived from the word “päivä” (day).

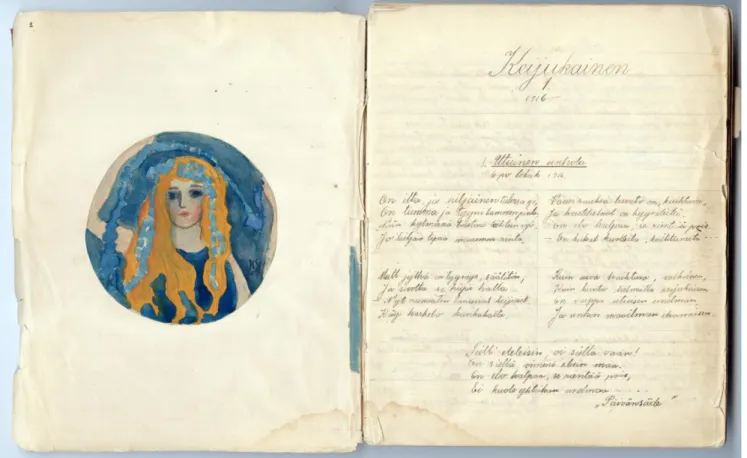

The second homemade book is Keijukainen (The Fairy) from 1916 by the poet and translator Elina Vaara (née Kerttu Elin Sirén) (Elina Vaara Archive, Box 3, SKS KIA) (Figure 5). Like Vaara, she was also a member of the Tulenkantajat group. The book contains over thirty poems, some of which are illustrated with watercolour paintings. The poems resemble Vaara’s later oeuvre in many respects, like the recurring themes of the orient and the nature, the ballad and fairy-tale forms and, as always, Vaara’s poems are rhythmically fluent and very decorative (Saarenheimo 2001b, 25–26). The poems are accompanied with a date and the name of the author (according to the dates the poems were written just within two months).

Fig. 5: The title double page of the handmade book Keijukainen by Elina Vaara. SKS KIA.

Vaara uses two pseudonyms with two variations: ‘Päivänsäde’ (Sunshine) or ‘P-e’ and ‘Sinisilja’ or ‘S-a’. For some reason, ‘Päivänsäde’ and its abbreviation systematically occur between quotation marks throughout the book. The name Sinisilja (translates roughly as Blue Cecilia) was taken from a poem by Larin-Kyösti (Karl Gustav Larson, 1873–1948), who was another poet with a pseudonym. Sinisilja was the pen name Vaara also used when she published her first poems in the children’s magazine Pääskynen (The Swallow) in 1917 (Saarhenheimo 2001b, 22, 24). The illustrations are also signed with the same pseudonyms as the poems, except one that has the initials KS, which probably allude to Vaara’s legal name Kerttu Sirén.

The pseudonym Elina Vaara was introduced in her debut collection of poetry Kallio ja meri (1924, The Rock and the Sea). It is a rather creative Finnish translation of her Swedish second and last name Elin Sirén. Instead of translating her last name directly as Sireeni (siren) she took the more dramatic metonym Vaara (danger), which was the pen-name she used for the rest of her life. The name Elina Vaara nicely demonstrates Genette’s conclusion that “using a pseudonym is already a poetic activity, and the pseudonym is already somewhat like a work” (Genette 1997a, 53‒4).

Imitations of the publisher’s peritext

The imitation of printed books in juvenilia manuscript is the most apparent in what Genette calls the publisher’s peritext. In a printed book, this realm is under the sole responsibility of the publishing house. Basically, the publisher’s peritext are the features of the book that distinguishes a publication from a private manuscript. It includes the cover, series, the title page and its appendages, typography and the selection of the format and paper (Genette 1997a, 16). Alexander observes that imitation in juvenile manuscripts often extends to the form and typefaces of printed publications. Branwell and Charlotte Brontë, for example, imitated not only the content of the children’s periodical Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine but also its outer appearance in their “Blackwood’s Young Men’s Magazine” (Alexander 2005b, 18–21; 2005c, 34–35). Thus, juvenile book and magazine makers not only imitate the role of literary authors but also those of publishers and printers.

All four of my examples of juvenilia manuscripts imitate several features of the publisher’s peritext like the cover, title page, format and typography. The format is perhaps the most basic feature that distinguishes these juvenile manuscripts especially from manuscripts that aim to be published. Usually a fair copy manuscript consists of loose leaves of standard size paper. Three of my juvenilia examples, however, are all folded leaves of paper that have been sewn together in a codex format. The sizes of the books correspond roughly with the trigesimo-secundo format. The fourth is Vaara’s Keijukainen, for which she used an octavo sized (22 x 14 cm) hard-cover notebook.

Similarly, Kauhun kirja (The Book of Horror) by Helka Heinonen, later known as the poet, journalist, translator and teacher Helka Hiisku, is a 20-page booklet made of folded grid paper leaflets bound together with a string (Helka Hiisku Archive, Box 3, SKS KIA).6 It has a paper cover page that imitates a book cover (Figure 6). The size of the book is about 13 x 7 cm. The book has not been dated but there is a mention in the text of “viime vuonna—1924” (last year—1924) which might indicate that the book was made in 1925. At the time, Hiisku would have been thirteen-years old. On the first double page, there is a decorated title “Rehtori” (Headmaster) on the left page, and on the top of the left page, there is a subtitle that has been added later with a pen between the text lines written in pencil: “eli kertomus jalosyntyisestä, hyvin kasvatetusta tytöstä, jonka elämän vääryydellisyys ja ihmisten ymmärtämättömyys turmeli” (or a story of the noble well-bred girl who was corrupted by the injustice of life and thoughtlessness of people). The narrator of the text recounts the wrongs that she has suffered in school, such as unjustified detentions that have filled the narrator with hate towards her headmaster.

6 In her school years, Hiisku also edited illustrated manuscript magazines titled Pippuri (The Pepper) and Pakkastiainen (The

Siberian Tit) together with her friends. Later she kept a diary during the Winter War (1939–1940) and the Continuation War (1941– 1944) working as a radio operator in the women’s voluntary paramilitary service. The diaries are also carefully designed and richly illustrated with drawings and photographs (Launis 2017, 19, 106).

Figure 6. The back and front cover pages of Kauhun kirja by Helka Hiisku. SKS KIA.

The front cover is richly decorated with plant motifs such as flowers and leaves. The title of the book is in the middle of the cover framed with a downward pointing triangle. There is also a drawing of a face peeking from the bottom of the front cover. On the top right corner of the cover is the author’s name: “Kirjoittanut Helka Heinonen”. The back cover of Kauhujen kirja is especially interesting due to its imitation of printed books. It is decorated with a plant motif but there are also peritextual features that are direct imitations of the conventions of printed books. Firstly, on the top of the back cover is the name of the publishing company: “Kustannus-osake-yhtiö Silja-Helka Brutus” (Publishing Company Silja-Helka Brutus). Secondly, framed in the middle of the page, is the price of the book: “Hinta: 20 p.” (Price: 20 p. [pennies]). Lastly, below the price, there is a mention or advertisement of other titles of the publishing house, including prices. At the time, the price of Finnish books was usually placed on the back cover and the same space was often used for advertising other titles by the same author or from the publisher.7 Interestingly, the publisher’s name “Silja-Helka Brutus” suggests that Hiisku had a business partner. This “Silja” is probably also the name behind the initial “S” which is recorded as the author of the title Sammunut rakkaus (Dead Love) in the list of books. Koskelainen’s Kulnew has a paper cover page that actually can be also interpreted as a title page (Figure 3). Kulnew as well as the 13 other homemade books and magazines by Koskelainen in the Archive of the Finnish Literature Society are remarkably well produced. Kulnew is made of grid paper leaflets bound together with a string. The size is about 14 x 7 cm. Text, decorations and illustrations are usually in ink. Koskelainen took the imitation of printed books to an altogether new level not only by producing several homemade books and

7 See, for example, the back cover of Juhani Aho’s (1861–1921) short story collection Omatunto (1914, Consciousness) which is

magazines but also by creating a book series with a subseries and magazines with several issues (Kuvalehti Suomen lapsille [Pictorial for the Children of Finland], Pikku Suometar [Little Suometar] and Toveri [Mate]). As Genette remarks, the use of series is a way for large publishers to show and control the diversity of their publications (Genette 1997a, 22). Kulnew is the first book of the series Nuorisokirjallisuutta (books for the young) and belongs to the subseries B that is dramatic literature. The cover page meticulously imitates the title pages of contemporary printed books with the lettered titles and bibliographical details: name of the series, the title of the work, genre indication, name of the author, the mentioning of the source text, year and place of publication. It even mentions the number of the edition of the book: “Ensimmäinen painos”, which translates literally as “first impression”, pretending thus to be a printed book instead of a handmade booklet. Kulnew also has a title-page verso that gives the publisher’s name at the bottom of the page: “Yrjö Koskelainen/Kustantaja” (Yrjö Koskelainen/Publisher). The back cover is simple with only the price of the book: “Hinta 10 p.” (Price 10 p.) mentioned at the bottom of the page.

Vala’s Korven kuiskehia is bound in cardboard covers. The size of the book is about 15 x 9 cm. It is written and decorated in ink. The hand-drawn front cover has a double frame and is embellished with pine sprig motifs that resonate with the poems’ theme of withdrawal to the woods (Figure 4). Like the book covers of the time, the cover of the homemade book gives the name of the author, the title of the work, genre indication and at the bottom the place and name of the publishing house: “Porvoo/Kotikirjallisuus-Osakeyhtiö” (Porvoo/Home Literature Publishing Company). The back cover is blank. The book has a separate title page with the title of the book and before the name of the author, there is a genre indicating expression “runoillut” (poetry by). The publisher’s emblem with the letters “K. oy.” within a frame is in the middle of the page. The name and location of the publisher are repeated at the bottom of the page. As in Koskelainen’s Kulnew, Korven kuiskehia also has a title-page verso. It mentions the place and date of publication: “Porvoo maalisk. 1918” (Porvoo March 1918) framed in the middle of the page.

As stated above, Vaara’s Keijukainen is made of a hard-cover notebook. There is neither text or embellishment on the cover nor is there a title page. The title of the work appears on the top of the first text page but there is no author name (Figure 5). Instead, every poem is signed with one of Vaara’s pseudonyms. There is, however, a table of contents at the end of the book and at the bottom of the page, a time span when the poems were written and the name of the publisher: “Sinisiljan ja ‘Päivänsäteen’ kirjapaino O.Y. 1916” (The Sinisilja and ‘Päivänsäde’ Press Company 1916).

The place of this publisher’s peritext resembles the colophon of medieval manuscripts and early printed books where the information about the place and date of publication and the name of the publisher was stated at the end of the book. However, a more likely model for Keijukainen is the contemporary children’s periodicals and literary magazines such as Christmas magazines: the poems are carefully laid out in two columns per page, the titles of the poems are underlined, the book is embellished with pen-drawn decorative lines that separate the poems from each other and many of the poems are illustrated with watercolour paintings glued on the pages. The appearance of the pages is much closer to a periodical such as Pääskynen than a collection of poetry. Christmas magazines were highly decorated and often included colour illustrations. According to Vaara’s biographer Kerttu Saarenheimo, her parents used to regularly order Christmas magazines. Vaara also began her career by publishing in magazines. Before her debut, Kallio ja meri, she had already published over 80 poems in magazines (Saarenheimo 2001a; 2001b, 27–29).

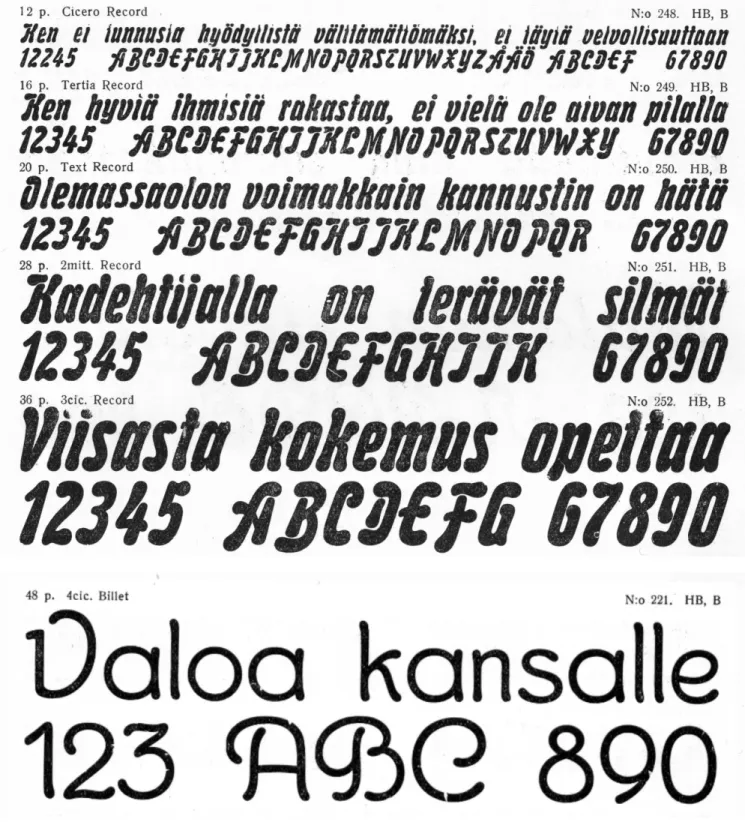

Korven kuiskehia, Kauhujen kirja and Kulnew are also interesting from a typographic perspective. Genette remarks that the choice of typefaces and the layout of the text can have an indirect effect on the interpretation of the work (Genette 1997a, 34). There are well known cases, such as Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (1897), where authors have also been involved in the design of the typography of their works. In the case of juvenilia handmade books, the young writers often also assumed the role of the graphic designer and can thus be considered directly responsible for the visual appearance of the text. Many times, the model for the visual dimension of the hand-made books seems to have been the printed book.

The cover of Koskinen’s Kulnew, for example, resembles the typographical style that was popular in the late nineteenth century title pages where the text lines were centred and almost every line was set with a different typeface. Often the lines were laid out in the shape of an urn by manipulating type size and spacing.8 Although the lines on Kulnew’s cover page are not perfectly centred, Koskelainen has used considerable effort in writing and drawing the lines in different styles.

Interestingly, it looks like Hiisku and Vala might have had the same kind of Art Nouveau calligraphic characters in mind when they designed their handmade books. The lettered title on the cover of Kauhujen kirja and the publisher’s emblem ‒ especially the letter K ‒ on the title page of Korven kuiskehia are quite similar and resemble some typefaces and hand lettering that were used on book covers and title pages at the turn of the century (Figure 4 and 6). The hand-lettered title on the cover of Eino Leino’s (1878–1926) collection of poetry Yökehrääjä (Night Spinner, 1897), which was designed by the painter Pekka Halonen (1865–1933) is also notable.9 The same kind of round, uneven brush stroke-like organic shapes can be found

in the calligraphic display typefaces of the time, such as, Billet and Record (Figure 7).

In Korven kuiskehia, the hand-lettering of the text pages is also quite stylized, especially the upper-case letters. Likewise, the layout of the text pages resembles printed collections of poetry. There is a page number between hyphens on the top of the page although the pagination does not continue till the end. The poems have been carefully laid out on the pages. If a verse does not fit in the same line, Vala follows the typesetting conventions and indents the rest of the verse all the way to the right margin. The titles of the poems have been underlined with a broken line and there is extra blank space above the titles, which is quite usual in printed books. The poems are dated and some of them are embellished with drawn vignettes whose motifs are thematically related to the content of the poems.

8 See, for example, the cover and title page of the collection of Finnish translations of Runeberg’s poems titled Vähemmät eepilliset

runoelmat (1887, Lesser Epic Poems), available online: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fd2010-00000199.

9 The book is available on-line: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fd2010-00000593. See also, Halonen’s covers for Juhani Aho’s Kirjasia

kansalle (1900, Books for the People): http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fd2010-00000547 and Katajainen kansani: toinen sarja (1900,

Fig. 7: Record and Billet typefaces from the type specimen book Kirjasinnäyte (1926). Turku: Kirjapaino Polytypos. Pages 61 and 66.

Conclusion

Clearly, the handmade books by Vaara, Vala, Hiisku and Koskelainen are not ordinary literary manuscripts. They are neither drafts or working manuscripts that bear witness to the genetic process of a literary work nor are they fair copies to be submitted to the publisher nor printer’s copies ready for typesetting. Although the bibliographic codes and peritexts of these handmade books, such as, handwriting and illustration refer to their production process as autographic objects, they nevertheless imitate and pretend to be printed books.

Theoretically, the special thing about these juvenilia handmade books is that they invert the conventional relationship between the manuscript and the printed book. By imitating printed books, handmade books bring the ubique bibliographic codes and publisher’s peritexts into the realm of the unique manuscripts. Consequently, it becomes problematic to separate the linguistic code from the bibliographic code in handmade books, which can be a practical challenge in editing juvenilia. On the one hand, representing handwritten juvenile manuscripts in type effaces bibliographical features that might be crucial to their interpretation. On the other hand, not every reader is necessarily interested in the visual, material and genetic dimension of texts. As Alexander points out, this is a viewpoint that must be considered if the aim is to make juvenilia writings available for a wide audience (Alexander 2005a, 85–86). The situation is somewhat chiasmatic in handmade books, since in many cases they not only contain texts in longhand but also lettering. Thus, a piece of writing can be considered an autographic drawing as much as a reproducible allographic text. Representing a drawing of a typeface in type would undo the interplay between the model and the imitation, which is a fundamental feature of these documents.

Unlike Russian avant-garde handmade books from the early 1910s and late 1970s DIY punk magazines that critique mass production through their handmade quality and by appropriating features from mainstream publications, my examples of juvenile handmade books do not undermine or deconstruct the concept of the printed book or conventions and institutions related to it (Compton 1978, 69–75; Triggs 2006, 69). Quite the contrary, the form of the book has been so important to these juvenile authors that they have wanted to see their texts in the form of a book.

According to Genette (1997a, 34), typesetting is the act that shapes a text into a book but I dare say that all the publisher’s peritexts take part in what makes a book a book. Peritexts are metonymies or indices of a finished and published work that has been elevated to the status of literature, especially, if the work is published by a recognised publishing company. It is, perhaps, not a mere coincidence, that all my examples of handmade books were “published” by a fictitious company. Peritexts are thus not only the thresholds of interpretation but also the thresholds of literary works and literature in general. By imitating the bibliographic code and peritexts of printed books, Vaara, Vala, Hiisku and Koskelainen worship the printed book as the epitome of literature.

Bibliography

Aho, Juhani. 1900. Katajainen kansani ja muita uusia ja vanhoja lastuja vuosilta 1891 ja 1899. Toinen sarja. Helsinki: Otava.

___. 1900. Kirjasia kansalle: Isäntä ja mökkiläinen y. m. kertomuksia. Helsinki: Otava. ___. 1914. Omatunto: saaristokertomus. Helsinki: Otava.

Alexander, Christine. 2005a. “Defining and Representing Literary Juvenilia”. In The Child Writer from Austen to Woolf. Eds. Christine Alexander and Juliet McMaster. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge and New York, 70–97.

___. 2005b. “Nineteenth-Century Juvenilia: A Survey”. In The Child Writer from Austen to Woolf. Eds. Christine Alexander and Juliet McMaster. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge and New York, 11–30. ___. 2005c. “Play and Apprenticeship: The Culture of Family Magazines”. In The Child Writer from Austen to Woolf. Eds. Christine Alexander and Juliet McMaster. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge and New York, 31–50.

Alexander, Christine and Juliet McMaster. 2005. “Introduction”. In The Child Writer from Austen to Woolf. Eds. Christine Alexander and Juliet McMaster. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge and New York, 1– 7.

Bornstein, George and Theresa Tinkle. 1998. “Introduction”. In The Iconic Page Manuscript, Print, and Digital Culture. Eds. George Bornstein and Theresa Tinkle. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1–6.

Compton, Susan. 1978. The World Backwards: Russian Futurist Books 1912–1916. London: The British Library.

Genette, Gerard. 1997a. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

___. 1997b. The Work of Art: Immanence and Transcendence. Trans. G. M. Goshgarian. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Goodman, Nelson. 1985. Languages of Art. An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co.

Grönstrand, Heidi. 2006. “Naiskirjailija ja nimimerkki. Anonyymit tekijät romaanin kehittäjinä 1800-luvun puolivälin Suomessa”. In Tekijyyden tekstit. Eds. Kaisa Kurikka and Veli-Matti Pynttäri. Suomalaisen

Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 1072. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 129–152.

Gutjahr, Paul and Megan Benton. 2001. “Introduction: Reading the Invisible”. In Illuminating Letters: Typography and Literary Interpretation. Eds. Paul Gutjahr and Megan Benton. Boston: University of Massachusetts, 1–15.

Kemppainen, Ilona, Kirsti Salmi-Niklander and Saara Tuomaala. 2011. “Modernin nuoruuden kirjalliset maailmat”. In Kirjoitettu nuoruus: aikalaistulkintoja 1900-luvun alkupuolen nuoruudesta. Eds. Ilona Kemppainen, Kirsti Salmi-Niklander and Saara Tuomaala. Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/

Nuorisotutkimusseura Julkaisuja 117. Helsinki: Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/ Nuorisotutkimusseura, 6–18. Kirjasinnäyte. 1926. Turku: Kirjapaino Polytypos.

Korpela, Simo. 1927. Ristinvirsiä. Jyväskylä: Gummerus. ___. 1927. Ristin rintamalta. Jyväskylä: Gummerus.

Koskela, Lasse. 2001. “Larni, Martti”. In Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu. Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura,

https://kansallisbiografia-fi.libproxy.helsinki.fi/kansallisbiografia/henkilo/4974, Accessed 25 September 2018.

Laine, Martti. 1937. Kuilu: kertomus eräästä ihmiskohtalosta. Helsinki: Kirjailijain Kustannusliike. Launis, Kati. 2017. Kynän kantama elämä: kirjoittavat Hiiskun sisaret. Turku: Sigillum.

Lehtonen, Joel. 1925. Punainen mies. Hämeenlinna: Karisto. ___. 1983. Kirjeitä. Ed. Pekka Tarkka. Helsinki: Otava. Leino, Eino. 1897. Yökehrääjä. Helsinki: Otava.

Majamaa, Raija ed. 1987. Enteitä ja uhmaa: kirjailijan nuoruus. Näytteitä Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran kirjallisuusarkiston kokoelmista. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 461. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

McGann, Jerome. 1991. Textual Condition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Moylan, Michele and Lane Stiles. 1996. “Introduction”. In Reading Books: Essays on the Material Text and Literature in America. Eds. Michele Moylan and Lane Stiles. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1–15.

Muiluvuori, Jukka. 2000. “Koskelainen, Yrjö”. In Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu. Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura,

https://kansallisbiografia-fi.libproxy.helsinki.fi/kansallisbiografia/henkilo/1625, Accessed 25 September 2018.

Oxford English Dictionary. 2018. Oxford University Press, www.oed.com, Accessed 4 September 2018. Pulkkinen, Veijo. 2017. Runoilija latomossa: Geneettinen tutkimus Aaro Hellaakosken Jääpeilistä. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 1429. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Runeberg, Johan Ludvig. 1848. Fänrik Ståls sägner. En samling sånger 1. Borgå: P. Widerholm.

___. 1860. Fänrik Ståls sägner. En samling sånger 2. Helsingfors: Finska Litteratur-sällskapets tryckeri. ___. 1889. Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat. Trans. Paavo Cajander. Helsinki: Kansanvalistus-seura.

___. 1938. The Tales of Ensign Stål. Trans. Charles Wharton Stork. Princeton: Princeton University Press and New York: American Scandinavian Foundation.

Saarenheimo, Kerttu. 1984. Katri Vala: aikansa kapinallinen. Helsinki: WSOY.

___. 2001a. “Elina Vaara”. In Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu. Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura,

https://kansallisbiografia-fi.libproxy.helsinki.fi/kansallisbiografia/henkilo/5774, Accessed 26 September 2018.

___. 2001b. Elina Vaara: lumotusta prinsessasta itkuvirsien laulajaksi. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Salmi-Niklander, Kirsti. 2004. Itsekasvatusta ja kapinaa: Tutkimus Karkkilan työläisnuorten kirjoittavasta keskusteluyhteisöstä 1910- ja 1920-luvuilla. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 967. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

___. 2011. “Sanelman sisaret: Sosiaalisen tekijyyden strategioita nuorten työläisnaisten suullis-kirjallisessa verkostoissa 1910–20-luvulla”. In Kirjoitettu nuoruus: aikalaistulkintoja 1900-luvun alkupuolen

nuoruudesta. Eds. Ilona Kemppainen, Kirsti Salmi-Niklander and Saara Tuomaala.

Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/ Nuorisotutkimusseura Julkaisuja 117. Helsinki: Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/ Nuorisotutkimusseura, 20–46.

Sarjala, Jukka. 1994. “Oma nimi ja kirjailijanimi. Hajahuomioita salanimistä ja nimimerkeistä”. Bibliophilos 3/1994.

Tikka, Marko. 2011. “Arkea ja hulluttelua: Esselströmin ja Lehkosen poikien todellinen ja keksitty elämä”. In Kirjoitettu nuoruus: aikalaistulkintoja 1900-luvun alkupuolen nuoruudesta. Eds. Ilona Kemppainen, Kirsti Salmi-Niklander and Saara Tuomaala. Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/Nuorisotutkimusseura Julkaisuja 117. Helsinki: Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/Nuorisotutkimusseura, 73–90.

Triggs, Teal. 2006. “Scissors and Glue: Punk Fanzines and the Creation of a DIY Aesthetic Author(s)”. Journal of Design History 19 (1), 69–83.

Tuomaala, Saara. 2011. “Maalaisnuoret ja sukupuoli 1920- ja 1930-luvun modernisaatiossa”. In Kirjoitettu nuoruus: aikalaistulkintoja 1900-luvun alkupuolen nuoruudesta. Eds. Ilona Kemppainen, Kirsti Salmi-Niklander and Saara Tuomaala. Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/ Nuorisotutkimusseura Julkaisuja 117. Helsinki: Nuorisotutkimusverkosto/ Nuorisotutkimusseura, 47–72.

Vaara, Elina. 1924. Kallio ja meri. Porvoo: WSOY.

Waltari, Mika and Olavi Lauri. 1928. Valtatiet. Helsinki: Otava.

Wollheim, Richard. 2000. Art and Its Objects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Veijo Pulkkinen earned his PhD in literature at the University of Oulu in 2010. In 2018, he was awarded

the Title of Docent at the University of Helsinki. From 2011 to 2014 Pulkkinen worked as a postdoctoral researcher funded by the Academy of Finland. He has published a monograph (Runoilija latomossa: geneettinen tutkimus Aaro Hellaakosken Jääpeilistä [2017, The Poet in the Typesetting Room: a Genetic Study on Aaro Hellaakoski’s Jääpeili]) and articles on visual poetry and the application of genetic and textual criticism to literary interpretation. In his current project, Pulkkinen studies the role of the typewriter in Finnish literature from genetic and medial perspectives.